ABSTRACT

Ecologically considerate use of nature (including agriculture) has often been associated with ‘stewardship’ as a human-nature relationship which involves human care, responsibility and accountability and is thus more sustainable than the alternative human-nature relationship of manager of nature. We show that the consideration of nature in agriculture can go further than stewardship by presenting data from qualitative interviews with Swiss Alpine farmers indicating that many of them view their relationship with nature as a form of partnership. Drawing on literature of human-nature partnership, we characterize this relationship by 1) bidirectionality – a give and take between nature and humans–, 2) the understanding of nature as a subject rather than an object and 3) interaction with nature that consists of collaboration rather than giving commands. The mountain farmers expressed all of these features in their farming practices and descriptions of their role in nature. A few farmers even saw their role as subordinates to nature, for which we introduced the new human-nature relationship category of “apprenticeship”. We further suggest that the partnership relation between humans and nature in many respects shares key features with relational values, for instance in its non-centric nature and in its emphasis of the combination of benefits for people with care for nature. In that sense, we aim at combining different accounts of inclusive, non-dichotomous and context-sensitive dealings with nature and we suggest that this combination is applicable also to contexts beyond agriculture.

Key policy highlights

People relate with nature in different ways for instance as managers, stewards, partners, participants, or observers.

Here we elaborate the partnership relation between people and nature, based on the academic literature and empirical data from farmers.

Partnership involves a give-and-take relationship between people and nature, where nature is seen as an active subject and collaborator.

We also propose a new category of human-nature relationship which we call ‘apprentice’ where nature is seen as a teacher.

When developing conservation measures, policy makers should be attentive to the different ways that people understand their relationship to nature to improve uptake of conservation measures.

EDITED BY:

Introduction

Reconnecting people with nature is considered a key leverage point for sustainability (Abson et al. Citation2017; Pascual et al. Citation2023). The most recent Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity Ecosystem Services (IPBES) assessment includes two leverage points related to values as pathways to transformative change (Chan et al. Citation2020). The shift in IPBES from an ecosystem service framing of the relationship between humans and nature (which only reflects limited kinds of human-nature relationships, see Flint et al. Citation2013), to the umbrella concept of Nature’s Contributions to People seeks to create more space for diverse conceptions of this relationship (Pascual et al. Citation2023).

The transition to ‘Nature’s Contribution to People’ was accompanied by an endeavor to resolve the dichotomy in the appreciation of nature as either instrumentally valuable or intrinsically valuable. To this end, a third value category ‘relational values’ was introduced to the environmental value discourse (Chan et al. Citation2016; Pascual et al. Citation2017). Relational values refer to the personal, cultural, and social meaning and significance that natural objects have for people (Himes and Muraca Citation2018; Neuteleers Citation2020; Deplazes-Zemp Citation2023). The exploration of relational values can increase our understanding of how people understand their relationship to nature and their role in nature. We build on our previously developed definition of relational values, which describes a bidirectional relationship involving genuine respect and care for nature alongside a eudemonic contribution to wellbeing (Deplazes-Zemp and Chapman Citation2021). The analysis of relational values further helps clarify how and why people feel responsible for protecting nature in particular situations in their daily life. Along this line (Muradian and Pascual Citation2018) suggested that the categories of instrumental, intrinsic, and relational values are subordinate to different relational modes, which define a more general way of relating to nature. In the case of relational values, they propose that stewardship or ritualized exchange may be the overarching relational modes.

Several typologies of human-nature relationships have been proposed (summarized by Flint et al. Citation2013). We draw heavily from de Groot et al. (Citation2011), which combines theoretical and empirical analysis to determine four categories: mastery over nature, stewardship of nature, partnership with nature, and participation in nature. Braito et al. (Citation2017) complete this list with the three categories: user of nature (focusing on benefits offered by nature), apathy with regard to nature (describing people whom nature is not really an issue) and nature distant guardianship (for people who appreciate nature in theoretical and domestic (pets, houseplant) contexts). A study of human-nature relationships in Switzerland (where our study is also located) used the categories of: user, sympathizer, controller and lover (Bauer et al. Citation2009). We are particularly interested in the category of partnership, which Knippenberg et al. (Citation2018) suggest is a key locus of relational values.

Some studies have found a contradiction in terms of people’s ideals of their relationship to nature and their private or professional actions (Muhar and Böck Citation2018; Pungas Citation2022). Understandings of human-nature relationships (HNR) are also shaped by social position (Eversberg Citation2021; Eversberg et al. Citation2022). Other evidence points to a correlation between particular types of HNR and pro-environmental behavior (Braito et al. Citation2017). There have also been changes over time such as a shift in US wildlife values away from the relationship of domination and towards mutualism (Manfredo et al. Citation2016). The New Ecological Paradigm has also shown a shift towards environmental attitudes over the last several decades (Dunlap et al. Citation2000).

The concept of nature is not without criticism. In many Indigenous traditions, the Western separation of humans from nature is incompatible with their understanding of who they are and the ways they relate to more-than-human nature (Kikiloi and Graves Citation2010; Sundberg Citation2014; Country et al. Citation2015). And within Western literature there is a large body of critical literature on the concept of nature (Soper Citation1995; Lee Citation1999; Kaebnick Citation2014; Vogel Citation2016). We do use the term “nature” as we hypothesized that it is exactly a particular non-dualistic understanding of this concept itself, which reveals how people view the human-nature relationship (Deplazes-Zemp et al., CitationUnder Review).

In this paper we examine the ways that Swiss Alpine farmers understand their relationship to nature on hand from in-depth interviews. In a previous paper based on the same dataset we describe three key relational values of this group and elaborated the syntax of these values (Chapman and Deplazes‐Zemp Citation2023). Here we focus on farmer’s understanding of their relationship to nature. We conclude with reflections on the ways that relational values and relationships to nature co-constitute each other. We will draw from our work on relational values to discuss a general framework which is based on different human-nature relationships to understand how these values are related to worldviews and associated attitudes and virtues. Since relational values are characterized by their context-, culture- and person specific features, our discussion of human-nature relationships will also focus on one professional group within a particular cultural context, namely mountain farmers in valleys around the Swiss Natural Park. We address the following research questions:

In what ways do farmers in our study understand their relationship to nature?

How do they understand their role in nature?

In what ways are relational values (and other environmental values) connected (or related) to categories of human-nature relationships?

From stewardship of nature to partnership with nature

Stewardship

While in the beginning of the 20th century the main purpose of agriculture was seen to be to increase production of food, the environmental sensitivity starting in the 1980s lead to a growing influence of the ideal of humans as stewards as a more nature-oriented interaction with nature than the classical ideal which was described as the role of the master of nature (Dobbs and Pretty Citation2004). In a literature review on the use of the concept of ‘stewardship’ in different disciplines, Enqvist et al. (Citation2018) found that the term was used with different meanings; they identified three dimensions that connect the different uses of the term: Care, Knowledge and Agency. ‘Care’ refers to feelings of responsibility and attachment that are associated with stewardship, ‘Knowledge’ concerns the importance of information and understanding in stewardship practices and ‘Agency’ highlights that stewardship involves an ability to act and implement the desired changes. Within sustainability science and biodiversity conservation, the use of the term ‘stewardship’ has been expanded to refer to actions, movements or approaches to sustainability or conservation more generally (Mathevet et al. Citation2018; West et al. Citation2018), which in some contexts lead to the reduction of the concept to an empty label (Pungas Citation2022). In the following, we focus on a narrower definition of stewardship as describing a specific human-nature relationship. In the discussion we will relate our results to both interpretations of ‘stewardship’.

Stewards are entrusted with something; in contrast to masters, stewards do not own the objects for which they are responsible. They can be held accountable for their actions and inactions with respect to that object by the owners. In religious interpretations of stewardship of nature this owner is God, in secular representations it is usually ‘society’. Accordingly, the environmental ethicist Robin Attfield (Citation2003) defines ‘human stewardship of nature’ as “the belief (which can assume religious or secular forms) that human beings hold the planetary biosphere as a trust, and are both responsible and answerable for its care, whether to God or to the community of moral agents” (p 200). Stewardship thus does not reduce nature to a resource and its instrumental value but extends to a sense of care and responsibility and involves appreciation of what we now call ‘relational values’ (Welchman Citation2012).

The stewardship worldview has been criticized as still being too anthropocentric and dichotomous (Palmer Citation1992), a criticism which may apply to some but probably not to all uses of the term. However, there is one important inherent element that a human-nature relation of stewardship shares with that of master: this is the clearly hierarchical structure. People as stewards are responsible for the world, they are to care for the world and to decide how to deal with it, therefore they are necessarily in the leading position. The previous descriptions illustrated that stewards should not take decisions with a focus on their own interests but with a focus on the well-being of the world and its beings (in such an interpretation it is not purely anthropocentric), in that sense it is a paternalistic hierarchy focusing on the well-being of the ‘subordinate’. Moreover, (in a secular interpretation) stewards are accountable to other people (but not to nature) for fulfilling their task appropriately. It is precisely this hierarchical role of people in nature that advocates of a partnership ideal of the human-nature relationship have criticized (Ebenreck Citation1983) and seek to overcome (de Groot Citation1992, Merchant Citation2004, Merchant Citation2003).

Partnership

The idea of partnership with nature is not new, and we draw heavily on existing literature to develop it. Sara Ebenreck describes such a partnership ethic in the context of agriculture which goes beyond stewardship. The difference she describes is that partnership involves “the importance of treating the land well out of responsibility to the land itself” (Ebenreck Citation1983, p. 35 italics in original). She describes an ethic which goes beyond enlightened self-interest and suggests we move from the language of use to that of working with, “because working with seems immediately to imply a partnership” (1983, p. 42). Ebenreck’s partnership ethic is based on three principles: “(1) respect for the fundamental nature of the land, (2) use that does not destroy that nature, and (3) returning something of value in exchange for the use” (p. 42).

Carolyn Merchant proposed a partnership ethic in her 2004 book Reinventing Eden. Her partnership ethic incorporates both nonhumans as well as relationships between humans, specifically calling for gender, racial and cultural inclusion. She discusses the ways that humans have in various contexts been ‘at the mercy of Nature’ as well as ‘dominators over it’ and suggests becoming instead ‘co-workers and partners with nonhuman nature’ (2004, p 225). This is premised on an ethic of moral consideration for both humans and nonhumans, acknowledging the needs of each. Here she suggests, as do others, the need for restraint of ‘human hubris’ (p 224). Merchant proposes a mindset shift, from nature as object to nature as an active subject. She recommends that we acknowledge the autonomy of nature, and our limited abilities to control or predict it. In her ethic humans are both part of and dependent on nature.

Finally we turn to the partnership with nature ethic developed by Wouter de Groot as part of the 1992 book on Environmental Science Theory, and developed empirically along with Mirjam de Groot and Martin Drenthen (de Groot et al. Citation2011). In their empirical paper, the team use survey statements encompassing ideas such as working together with nature and the equal value of people and nature as well as considering the needs of nonhumans. In the 1992 text de Groot describes a partnership ethic as seeing Nature with a capital N, equal to humans and neither above nor below, but an active Other (p. 486). In this conception, there are values attuned to people, nature, and their relationship (p. 530). De Groot calls this the ‘three-value character of partnership’ (p. 531) and considers each to have intrinsic value. The involvement or intensity of the relationship is not something to be maximized but should be appropriate to context. The content or quality of the relationship should entail non-dominance as well as a kind of giving or reciprocity (p. 532).

From the above, we highlight several aspects of a partnership ethic which we wish to explore in the empirical study that follows. These aspects also distinguish it from the stewardship human-nature relationship. One is the idea of bi-directionality. Ebenreck highlights this aspect explicitly, explaining partnership as, “not a one-way path, but a two-way connection” (p. 41) and de Groot also mentions it. Next is the idea of nature as subject and not object. This idea is highlighted most explicitly by Merchant and de Groot. This focus on nature as a subject has been referred to as ‘autonomous nature’ by Merchant (Merchant Citation2015) or as interactions with ‘active nature’ by one of us (Deplazes-Zemp Citation2022). Finally, we will draw on the idea that partnership includes active interaction and collaboration with nature and the skills required for such. These collaborations involve care for nature in some situations but also an awareness for the care nature takes for us in others. ‘Care’ is thus differently interpreted and contextualized than in the stewardship relationship, where it is considered to be one sided support of people to nature. Likewise, the two other dimensions of stewardship identified by Enqvist et al. (Citation2018) still play a role in partnership but in different interpretations. ‘Knowledge’ not only concerns an understanding of the consequences of one’s actions but a genuine interest and responsiveness in nature. This knowledge is based on the idea that we need to know our partner to be able collaborate with it. The third dimension ‘action’ in a partnership relationship is directly associated to active collaboration. The emphasis here lies less on importance of being able to assert oneself as in stewardship, but more on the relevance of coordinating and mutually adapting natural and human processes.

Methods

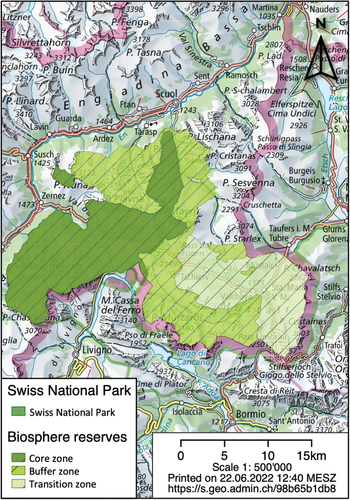

We selected as our study site two valleys surrounding the Swiss National Park: the Lower Engadine and Münster Valleys (see ). In this region, there are several different kinds of conservation designations, ranging from the strictest IUCN category in the Swiss National Park core zone, to a buffer zone region around the park, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a regional nature park where the focus is on sustainable development. This allowed us to discuss different conceptions of nature as embodied in these designations, e.g. the strict separation of people and nature in the national park versus the focus on human-nature integration in the nature park and biosphere reserve.

Figure 1. Map of study region. The valleys of Engiadina Bassa and Val Müstair boarder the Swiss National Park, which, together with the Regional Nature Park and part of the municipality of Scuol, form the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Engiadina Val Müstair. Map created from Federal Office of Topography swisstopo data and interface. Map re-used from (Chapman and Deplazes-Zemp Citation2023).

Farmers in these valleys practice traditional alpine livestock agriculture. Animals are summered in alpine pastures, managed communally by several farmers. Over the winter season, the animals are mostly fed by the hay (sometimes also silage) produced on the farm during the summer season. Farms usually consist of several fields at different elevations. Many farmers additionally have agro-tourism offerings (e.g. camping, sleeping in the hay, walks with farm animals) or in some cases part-time or seasonal jobs such as ski instructor, mountain guide or bus driver.

Chapman conducted 32 interviews during March 2019. We used a purposive sampling strategy, seeking a diversity of participants in terms of farm operations, gender, age and covering the extent of each valley, selected in collaboration with our local partners. We selected only farmers whose main source of income was from their farms. To specifically target a diversity of perspectives on human-nature relationships we applied a categorization developed with our local partners based on the farmers’ use of and our partner’s assessment of their belief in organic farming. In our context, organic certified production is the most profitable system for most farmers, reflected in around 80% of farmers having organic certification. We thus selected for farmers that we considered ‘organic with heart’, ‘organic as a business choice’ and non-organic (integrated pest management).

The interview protocol was developed in a collaborative process between the two authors and our local partners (see SI). It is based on the Syntax of Environmental Values framework (Deplazes-Zemp and Chapman Citation2021). In a previous paper based on this same dataset we focused on the specific relational values of farmers in the region (Chapman and Deplazes‐Zemp Citation2023). The interviews each began with broad questions about the farm and farmer, followed by an exploration of a specific relational value identified in the first part of the interview. We then explored the farmers ideas about their relationship to nature. We discussed the relationship to nature in the context of farm practices such as maintaining traditional structures (e.g. hedgerows), manure management, ongoing challenges with how to adapt to the increasing presence of wolves in the region, maintenance of alpine grazing areas, and practices to protect specific species or biodiversity (e.g. roe deer fawns that nest in pastures). We also discussed non-farm activities such as recreation (e.g. hiking, skiing), hunting, gathering wild species (e.g. mushrooms, berries), how to appropriately deal with hurt wildlife, and regional development efforts. After the first few interviews, it became apparent that a more direct kind of questioning was possible as indicated by farmers willingness to contradict ideas proposed by the interviewer. Chapman then additionally asked about farmer’s relationship to nature directly, e.g. how do you understand your relationship to nature, for example, as someone that steers nature, as a partner of nature, a caretaker or something else? The example relationships were drawn from the initial interviews as well as various discussions with local partners and pre-field work site visits. Here we sought to use terms that were descriptive while being as neutral as possible to allow respondents to provide their own conceptions. As hoped for, many respondents choose their own words and descriptions to characterize their relationship with nature. We used this as an open-ended question to inspire conversation, not a closed list. In the analysis phase we sought to connect these characterizations with existing constructs from the literature, to the extent there was a good fit. The discussion of the respondent’s relationship to nature was built on the previous interview parts about relational values and their farm and life, allowing context and connections between this more abstract line of questioning and the more concrete discussion of valued relationships to specific entities.

Interviews were transcribed by a local resident fluent in the local dialects. Transcripts were coded by the first author using NVivo (see codebook in SI). Interview transcripts were analyzed as a whole to understand how relationships to nature and relational values (or other environmental values) work together. Thus, while one specific question focused on this relationship, the whole transcript was coded for themes around nature and HNRs. Deductive codes were largely inspired by our conceptual framework (Deplazes-Zemp and Chapman Citation2021) and included e.g. “duty”, “attitude” or “relationships”. Inductive codes included diverse topics such as “satisfaction”, “biodiversity & ecosystem management”, “animal breeding”, “wild versus domestic”, “national park”, or “working together”.

Some important limitations to our methods are as follows. We did not investigate practices directly, so we can only infer practices to the extent discussed within the interviews. In this sense we cannot confirm if these values and HNR translate into more sustainable behavior (though many examples from respondents indicate they might). Another important limitation is that our study area is a rather unique region so the prevalence of partnership might not be as applicable in more industrial or intensive agricultural contexts.

At our institution, researchers use a self-assessment tool to determine if a study is high or low risk for the research participant, according to which our study was assessed as low risk. Only high-risk studies (usually clinical studies) are sent to a committee for ethics review. We followed standard practices of research ethics in our study. Participants were contacted initially by trusted local partners and invited to participate. If interested, they were contacted by MC and given information about the study’s purpose, funding, risks and benefits (orally and written). We chose to use oral rather than written consent as this is in fitting with local customs where agreements are normally made orally. Participants were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or opt out of any question. Many respondents commented that the interview was an enjoyable and interesting experience. After the completion of the study, respondents were informed via updates about the study’s progress and the results were presented via two presentations (one in each valley).

Results

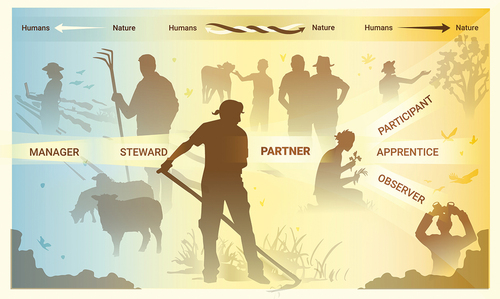

We identified four archetypical relationships between farmer and nature: manager of nature, steward of nature, partner with nature and apprentice to nature. ‘Manager’ refers to what is usually called master in the HNR literature, however, we have chosen to use a more neutral term of ‘manager’ in order to avoid problematic connotations associated with ‘master’ as well as to create a more open dialogue of ways that the HNR of manager can also underpin sustainability. ‘Manager’ captures the key elements describing mastership over nature (hierarchy, control, productivity) without the negative connotations.

While some farmers articulated an understanding of their relationship to nature that fell clearly within one of these categories, many others described their relationship as comprising diverse constellations. They considered the ways that they cared for, shaped, were responsible for, dependent on and were themselves a part of nature. Respondents had interactions with different elements of nature, e.g. maintaining alpine meadows, hiking with family, teaching ski lessons, collecting wild foods, hunting, working with farm animals, managing pastures, and using large machinery in natural areas. Given the diversity of interactions both within and beyond farming activities, it is then not surprising that many saw their relationship with nature as multifaceted. For this reason, we did not assign each farmer a specific category in our analysis.

In our interviews a variety of non-exclusive conceptions of nature arose, including:

Nature as the weather

Nature as a limit to humans or what humans can’t or don’t control

Nature as fragile or in need of care and protection

Nature as all around, including humans, farm animals, etc.

Some things are more natural than others

Nature as politics of biodiversity protection

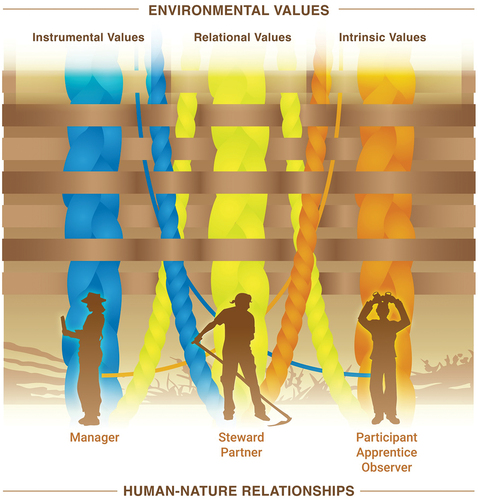

In the following, we describe each archetype, and discuss how they relate to specific kinds of values (relational, intrinsic, or instrumental) (see and ). For more information on the value categories see (Chapman and Deplazes‐Zemp Citation2023). We focus on the category of partnership, as this was the most common understanding in our sample, as well as the category that is most diverse. We also elaborate on the category of apprentice, which is a new descriptor of human-nature relationship, though this archetype was not very common in our study. We present the categories of manager and steward only briefly, as these HNR are well elaborated in extensive literatures. We also illustrate the HNRs participant and observer in , which are common in the literature, though were not important categories in our own data (and are therefore not included further in the results). For each relationship, we give example actions, focusing on the ways that farmers balance fodder production and manure distribution. Ideally, a farm in the region should achieve a balance between pastures and animals such that the amount of animal feed available on the farm in the form of grazing land or cut grass for the winter is sufficient to feed the farms’ animals. In turn, the amount of manure produced by the animals is appropriate for the land available for its distribution. This closed cycle was practically important because of the remote location, where transport of feed into or manure out of the region would be costly. If the circle is fully closed, then there is no external nutrients added to the ecosystem, and this is better for biodiversity. High nutrient (e.g. nitrogen, phosphorus) environments do not favor the unique alpine species that many conservationists wish to protect. Most farmers take this as an ideal rather than a strict limit, supplementing with small amounts of purchased feed as needed depending on how much feed was produced on the farm that year. We found that the ways farmers struck this balance nicely summarized the ways that the four different relationships were enacted.

Figure 2. The spectrum of human-nature relationships. The top row illustrates the conceptualized understanding of the hierarchical relationship between humans and nature: on the left, human-focused; in the middle there is a bi-directional relationship between humans and nature; on the right, nature-focused. On the right the spectrum branches into three categories (participant, apprentice, and observer), indicating that these all share the same position on the spectrum, where humans prioritize nature.

Table 1. Key characteristics of each of the three relationships between farmer and nature. Virtues reflect an interpretation of the empirical data via philosophical reflection.

Manager of nature

As managers the farmers control nature for their own purposes. For the respondent below, the analogy of sitting on a tree branch and not sawing on the wrong side came up. In other words, the limits of nature were respected to the extent that humans would not suffer. However, within these limits, benefits to humans can be maximized.

This influence of nature for me is always clear. I influence [nature] to some extent. So, I do not, in principle, let nature itself decide if it needs more or less, or if it’s even capable of surviving at all. If it’s not capable of surviving and I am convinced that I can make money there, then as a farmer, I create the conditions so that it is viable. [Interview #20]

While the above farmer does not presume complete control over nature, he takes it upon himself to set up the conditions so that he can make money from nature. In this understanding nature is a passive subject to be controlled. This description of nature is built on a foundation of instrumental value, here expressed by the focus on making money. Occasionally managers can also assign relational values to entities or animals they particularly like but not systematically or extensively enough to conclude that these values are characteristic for their relationship to nature.

Steward of nature

In this conception of human-nature relations, the farmer functions as a particularly benevolent and responsible boss of nature due to their planned and directed actions. This conception corresponds with common understandings of stewardship where nature is something to be cared for, but within a clear hierarchy where the human drives action.

As a farmer, one is not just a business person but also responsible. One has received a piece of this earth and one should take care of it … for all the plant species and animal species that live on it. Humans are simply the boss, they can’t do that differently. Humans have more abilities than all other [species] and then they should also employ them smartly and employ them well. [Interview #7]

Here the focus is on humans using their greater abilities and knowledge to better care for nature, not primarily for their own interests but because they have the task to decide what is good for nature. Stewardship is of course still based on the idea that farmers can and need to benefit from nature, but always in a moderate, considerate way. Here nature is still a passive subject, but one to be protected. In the above description of a stewardship relation to nature, we see especially relational values of care as the basis for this relationship—here associated with responsibility to the plant and animal species that live on the land the farmer stewards. There is also an element of instrumental value hinted at by the reference to also being a businessperson as well as an element of intrinsic value indicated by respect towards animal and plant species, without regard to their utility or relation to people.

Partner with nature

The most common conception of the relationship between the farmer and nature amongst our interviewees was that of a partnership. We present this category, focusing on the three characteristics described in the introduction.

Many farmers depict a give and take relationship with nature, such as the following:

Really, I am a partner of nature … now it’s becoming spring, the snow is going away and it’s becoming green. It makes me happy. Nature wakes up and she gives us something again. She gives me grass and she gives me hay and I give her manure. Whether that’s good or not is another question (laughing). It is actually a partnership, a give and take. I take care of nature, or at least I try to. [Interview # 27]

In the above quote, we can see all three qualities of partnership identified in the introduction. First, bidirectionality here is described as the farmer giving nature manure and nature giving back grass and hay. Second, the farmer discusses nature as an active subject who “gives” and “wakes up”. Third, the farmer collaborates with nature, by providing manure and by other kinds of care. This farmer also displays a thoughtfulness about the challenges of collaborating with nature via traditional farming, as seen in comments that he is not sure if the manure is always good for nature and that he “tries” to care for nature. Beyond this, we also see the connection to relational values, where the farmer explains that “it makes me happy”. This happiness is a eudaimonic kind, based on the joy in seeing nature wake up and become spring and the satisfaction in the partnership. Here it is the land that has relational value in this HNR of partnership. The bidirectionality of the relational value is not only expressed through the services that the farmer provides for the land but also through what we call the orientation towards the land, the thoughtfulness, consideration, and care shown to the land.

Partnership with nature is bidirectional

The importance of a bi-directional relationship with nature is also emphasized by the following farmer:

We began early with the connectivity concept where we look after the hedges and trees, so that all of nature can live there and usually more extensive production, which means that one mows later so that the ground breeders have time to reproduce and naturally also for the beautiful flowers. But that usually means to give up fertilizing. But there I am not totally of the opinion that that goes in the right direction. Because before, when the farms were much smaller, and one had alpine huts all over and they had to put their manure somewhere. And then the meadows were also beautiful with flowers. [Interview #31]

Here too we can see the connection between the responsibility in the partnership (adapting farming practices to support nature) and the eudaimonic and aesthetic benefits of tending to nature in the form of ‘beautiful flowers’, here an indicator of successfully caring for nature.

However, the above farmer, while supportive of most biodiversity protection efforts expressed a common skepticism of giving up fertilizing on alpine meadows. Many farmers gave the same argument—that generations of farmers had put some manure on the alpine meadows and their good condition meant that this could not be wrong. As discussed above, under partnership, the idea of only ‘taking’ from alpine meadows without returning anything in the form of fertilizer felt wrong to many farmers. This common refrain which also nicely expressed the idea of partnership was called the closed cycle (geschlossener Kreislauf). A closed circle embodies the give and take described above, where the farmer ‘gives’ nature just enough manure and ‘takes’ the corresponding amount of grass and hay for the animals. Here we see relational values expressing a connection to the beautiful flowering meadows but also to past generations of farmers—based on the care for and tending of meadows and place-based connections to farming traditions and knowledge.

Farmers emphasized the importance of agricultural activities for nature, as the following farmer explains how it is important to share this idea with tourists who come to the region:

I really want to show the people that agriculture is necessary and nature is necessary and both are needed and not only nature or only agriculture. That it really needs both to have an intact nature in the end. That’s actually very important for us and that’s what I also want to show people, how we do that. [Interview #2]

This farmer rejects the separation between nature and (agri)culture by explaining that for intact nature, agricultural activities are needed. A common example of this is the role of alpine grazing and farmer’s own activities in maintaining alpine meadows and pastures. Without these activities, these areas would slowly become overgrown with shrubs and eventually become forests. These alpine agricultural areas are an important context for synergies between biodiversity protection and agricultural production. The idea that nature needs agricultures helps explain the relational importance to farmers of some activities that might otherwise seem purely instrumental, for example, when some farmers were engaged in ensuring the economic solvency of farming in the region, e.g. via product labeling or an effort to save the local dairy. To protect nature, in this understanding, then farming must also be protected. Just across the border in Italy, there are many examples of abandoned Alpine farming areas where alpine meadows have been overgrown with shrubs and trees. Maintaining the economic solvency of farming then in turn maintains the farmer’s ability to care for nature. This aspect of the partnership HNR can be seen as constituted by the relational value of caring for the meadows, and continuing a place-based tradition of farming, where careful farming practices are employed as part of an understanding of the importance of both nature and farming to the character of the place.

Partnership involves an understanding of active nature as a subject

A second characteristic of partnership with nature is understanding nature as an active subject, as seen below:

For me the land is equally important as the animals. Because the land lives and I live from my land. It has to work out and you have to have this relationship to the land.

Interviewer: And what is this relationship like?

When I walk through the pastures in Spring and see what grows, the grass thick, that is beautiful, ahhh. I enjoy it when there are lots of good plants. Of course, when there’s only muck, then you have done something wrong. Important is that when you drive machines you do that with feeling … . that you carefully work with the machines and really not just drive anywhere or by any weather, that you have that under control. [Interview #32]

Here again we see the characterization of nature as an active subject, ‘the land lives’; in other words, it is not just a substrate upon which people act, but a living entity that responds to their actions. The above quote also emphasizes the element of accountability (‘you have done something wrong’), which is important in both stewardship and partnership. But while care prevailed as the attitude behind the relational values in stewardship, here the relational values involve recognition of an independent partner. We thus speak of respect-based relational values although care is evidently part of partnership too.

Here too we see the connection to relational values in the form of eudaimonia—the importance of both land and animals (two key relational values described in our other study, Chapman & Deplazes-Zemp Citation2023), the relationship to the land, the way the farmer lives from the land, the reference to beauty and enjoyment (emphasized by “ahhh”), and the imperative to respond to nature by driving machines “with feeling” all point to the relational value of the land for this farmer.

We can also see this perspective of active nature in the ways that farmers organize their farming practices around the patterns of nature. In contrast to stewardship, where people know best and create a schedule and stick to it, partners must constantly adapt according to the weather, their observations of the plants and animals. So here we see the ways that nature is understood as in an active and process-oriented way.

Partnership involves collaboration with nature

The main ways that farmers discussed collaborating with nature were about conducting their traditional farming activities under consideration of natural processes. In many cases this involved timing the application of fertilizer with the weather as well as the below example of adapting the use of machines to avoid soil compaction (also shown in the quote above from interview #32). This farmer describes how he gets very angry when construction crews drive over the land during a rainy time, explaining:

A farmer would not do that because he knows that causes soil compaction and that’s not good. You see that years later. And they do it because they have a timeline. And I get terribly angry because they simply lack the relationship. Some people have no relationship to nature. [Interview #27]

Here we also see the importance of this bidirectional relationship, emphasized in its contrast—construction crews that have ‘no relationship’. The farmer instead has a give and take relationship with nature; he or she makes sure to avoid soil compaction (giving to nature) and in return has long-term better soil quality (benefitting from nature). In this case the relational value underpinning the HNR of partnership is again between the farmer and their land and the focus on collaboration further underpins the recognition of an independent partner which is typical for respect-based relational values.

We can also understand farmers’ views of collaboration with nature by discussing a context in which this interaction is explicitly forbidden: the neighboring Swiss National Park. While some farmers appreciated the Swiss National Park and even found it beautiful others were more critical. The Swiss National Park has the highest level of protection as designated by UNESCO and employs a strict policy of non-intervention in nature. However, prior to becoming a national park over 100 years ago, the area was heavily used and today a highway and dam intersect the park. For some farmers this history makes the park an interesting negative example of what might happen if they stopped caring for their lands. It is an area that used to be cared for by people and now is strictly non-interventionist.

It is quite different, I think. The forest in the national park is a disaster; there are just many trees lying there; it is disorder. It is just not like here where one takes out the trees and maintains it. Then for me the forest does not look beautiful (laughs) or because it has simply been left to nature. Then as well, the way the pastures are used in the national park is brutal. [Interview #14]

In the above quote, the extreme language of “disaster” to describe the forest and “brutal” to describe the pastures highlights these different ideas of what it means to fulfil one’s share in the partnership with the land. Without the support and care of humans to remove dead trees and to assure that meadows are well-maintained and not overgrazed, the national park is a stark contrast to the kinds of responsibilities that farmers may feel towards their land—responsibilities associated with relational values of their pastures and meadows.

Apprentice to nature

Our interviews showed that for a few farmers the role of nature in the human-nature relationship was beyond that of an “equal” partner. We call this relationship ‘apprenticeship’ because nature was seen analogously to a knowledgeable and experienced teacher. In addition to the three qualities of partnership, the relationship of apprentice to nature also had the additional aspect of accepting hard limits. Nature was ascribed a certain power and knowledge, that the farmer placed above his or her own capabilities. The most explicit example of this is how the concept of the closed cycle was implemented. For most farmers with a partnership relationship this was taken as an ideal; however, in the following quote a farmer with an apprentice to nature relationship explains how they take this limit literally.

My motto is simply, that what grows you take … So you look if you have too little food you just have to sell some animals in the fall. Every year I look how much feed I have for how many animals and then so many animals are kept. And then you go to the butcher or not. Yes then nature decides how it really is on the farm.

Interviewer: So in your case nature is quasi the boss?

Yes, nature is the boss. She is the one who determines how much there is and I don’t have more. [Interview #19]

Rather than purchase supplemental feed during a bad harvest year, this farmer then accepts that nature decides and only keeps the number of animals over winter that they can feed with the hay produced over summer. The other animals must be sent to the butcher.

Here a key idea is accepting sometimes difficult, uncomfortable, or even dangerous consequences of nature. For example:

Everyone wants nature back and as soon as it’s there they don’t want it anymore. Because it is inconvenient and that has been the problem with the bear and wolf and with mother cow husbandry. ‘We want nature back, the calves can suck, the mothers live with the calves on the pastures’, but oh the cow now has her instinct and wants to protect the calf and then the people come there and say; ‘Yes that’s not possible, we don’t want nature’. [Interview #9]

In the above quote, the farmer works to accept the dangers and limits of nature and adapts to them by, for example, teaching people how to behave around mother cows or shepherd guard dogs. But he is frustrated that many people would rather not have things quite so natural when it becomes threatening.

In another example, a farmer had designed his farm system such that he could get by with a low level of production. He explains, ‘I take what comes and it doesn’t have to be too much’ [Interview #9]. This theme of not taking too much was an important characteristic of this relationship to nature. These farmers emphasized the importance of limits, e.g. of not maximizing production, of sufficiency, often in acknowledgement of the delicate environment in which they work. These three examples all display a more intrinsic value basis for the HNR of apprentice; the instrumental element of relational values or eudaimonic joy seen in the quotes for the other relationships are missing here, replaced by a focus on respect for and acceptance of nature and its limits.

Discussion

In the above we have highlighted four modes of how Swiss mountain farmers relate to nature: as manager, steward, partner, and apprentice. Our research aimed at connecting highly personal relational values to broad categories of human-nature relationships. Importantly, these relationships are archetypes; in other words, an individual farmer does not necessarily have one ‘pure’ relationship to nature but inhabits several of the above at once or depending on their particular activity or role (e.g. as a farmer, as a hunter, as a hiker, or as a community member). Nonetheless we see these relationships as useful orientation and comparison points. That individuals identify with a bundle of human-nature relationships is consistent with other studies (Braito et al. Citation2017; Muhar and Böck Citation2018). The human-nature relationship differs across individuals and groups, but also within one individual in different situations, such that we can speak of relationships in the plural (Flint et al. Citation2013; Braito et al. Citation2017).

A novel category of apprenticeship

While manager (mastership), stewardship and partnership are all well-established categories in the literature, the category of apprentice to nature is (to our knowledge) a new proposal. In much of the other literature on this topic, the category of ‘participant in’ nature is used as the most ‘ecological’ relationship. Why did we not use this pre-existing category? Participant usually describes a more passive relationship to nature, often characterized as spiritual or worshipful, with example ways of participating in nature, being for example hiking, forest bathing or other outdoor activities (van Den Born Citation2008; de Groot et al. Citation2011; Braito et al. Citation2017). This did not seem to fit with our most ecologically minded farmers, whose active relationship with nature was the basis of their livelihood. What these apprentices shared with participants and observers was a view of nature as hierarchically above humans. They conducted their farming activities with extreme care, remaining in the limits of what nature needed. The apprentice’s care is not benevolently donated by the farmer but requested by nature. Thus, we do not intend to replace the category of participant but rather expand the range of ways to think about very careful tending to nature (see ).

Bidirectionality of partnership as a human-nature relationship

We understand partnership as a bidirectional relationship with elements of manager/stewardship and moments of participation/apprenticeship/observation. However as with the bidirectionality of relational values (see below), in partnership the elements of stewardship and apprenticeship are not identical with the respective unidirectional relationships. This can be illustrated with the example of the involved virtues. The relationships of stewardship and partnership share the virtue of “responsibility”. For stewardship this responsibility is that of a paternalistic guardian; for partnership, responsibility is that of an equal partner responsible for their particular task (e.g. providing fertilizers). It is inherent to the partnership relationship that nature is understood as an active collaborator rather than a passive resource or environment to be shaped. In parallel, the relationships of partnership and apprenticeship share the virtue of “restraint”. As illustrated by the different implementations of the ideals of the closed circle, restraint in the case of apprenticeship goes farther towards subordinating one’s own (economic) interests to the wellbeing of nature. Whereas in partnership the farmer’s restraint is understood as a contribution of a give-and-take relationship.

Other authors have observed elements of what we describe as partnership relationships using different frameworks or theoretical approaches. For example, in a study of indigenous practices from Amazonia and Cascadia, the focus is on showing the ways that indigenous peoples give back to nature in terms of very concrete actions, described in this case as “services to ecosystems” (Comberti et al. Citation2015). Another study from Odisha, India highlights the ideas of reciprocity and the ways that care for nature can be seen as a gift to nature (Singh Citation2015). The idea of the gift as part of a reciprocal relationship can also been seen in the hunting cultures of the Kluane First Nation in northern Canada (Nadasdy Citation2007). In the field of ecological restoration, reciprocity between humans and the restored ecosystem has been proposed as model for more effective restoration projects (Geist and Galatowitsch Citation1999). These studies can be seen as drivers and antecedents of the relational values literature in which we situate our current work (Chan et al. Citation2016; Pascual et al. Citation2023).

Our contribution is to elaborate a nuanced and specific conception of partnership, describing its characteristics and connections with values and virtues, based on our approach of integrating environmental ethical analysis with empirical qualitative social science. In our understanding of ‘bidirectionality’, giving back to nature can involve either or both of specific actions as well as attitudes of respect, care, consideration, or responsibility that are oriented towards nature. In this we align with broader calls to move beyond interactionalism (such as Bennett and Reyers Citation2024) by focusing on the qualities of the relationships we describe between humans and nature (rather than the impact of humans on nature or vice versa).

A second parallel to our findings is found in the stewardship literature, where ‘stewardship’ is often used as a boundary object to describe a wide variety of pro-environmental behavior and mindsets (Enqvist et al. Citation2018; Mathevet et al. Citation2018). This use of the term is in contrast to the more specific use of the term in which we base our analysis (such as Palmer Citation1992; Attfield Citation2003; Dobbs and Pretty Citation2004; Van Den Born Citation2008; de Groot et al. Citation2011; Braito et al. Citation2017; Pungas Citation2022). The broader stewardship literature (using terms such as ecosystem stewardship, planetary stewardship, etc.) may describe a kind of stewardship that would also encompass what we describe here as partnership and apprenticeship (Seitzinger et al. Citation2012; Gordon et al. Citation2017; Buijs et al. Citation2018). For example, Opdam (Citation2017) discusses landscape stewardship based on “reciprocal feedbacks” and “human dependence on nature” (p. 334); later the transition to landscape stewardship is described as requiring local actor groups to see “nature as partner” (p. 341). In another example, West et al. (Citation2018), explicitly use stewardship in the broader sense. Their discussion of care as emergent from social-ecological relations describes a human-nature relationship where ‘ecologies “have a say” in how they are cared for’ (p. 6)—what we would call partnership or even apprenticeship (where nature decides, and the farmer follows).

The co-constitution of human-nature relationships to and values of nature

For each human-nature relationship, one type of values predominates, but all three can be relevant. This is illustrated in .

Figure 3. The co-constitution of environmental values and human-nature relationships. The top row indicates the three categories of environmental values represented by woven strands (instrumental in blue, relational in yellow, intrinsic in orange). Each value type is connected to each human-nature relationship (illustrated in the bottom row) in different strengths, indicated by the thickness and number of strands of the connections. Three thick braided strands represent the strongest connection between values and relationships; two woven strands show an important but less connected relationship and a single thin strand a lesser connection. All the categories of environmental values and human-nature relationships are woven together into a single tapestry, highlighting their interconnection.

Instrumental values primarily constitute the manager HNR, though instrumental and relational values are involved to a lesser degree. The steward HNR can be seen as constituted primarily by relational values that entail a paternalistic form of care rather than a collaborative respect (as in partnership). In some cases stewardship may be motivated by intrinsic values of nature (Opdam Citation2017) as well as care-based relational values as described by West et al. (Citation2018). In apprenticeship, intrinsic values of nature play a more important role than in the other HNR, due to its focus on nature’s own needs, without necessarily a clear benefit for people; however relational values play a central role too. Respect-based relational values (more than the care-based relational values characteristic in stewardship) constituted understandings of partnership with nature.

The concepts of relational value and partnerships co-constitute each other in the sense that partnership is only possible if natural objects are considered respectfully and are part of a beneficiary interaction and on the other hand, those relational values that involve a respectful collaboration on a par with natural objects are automatically associated with a partnership relationship. Therefore, one specific situation, narrative or action of a farmer can at the same time be an enaction of his or her relational values and his and her partnership relation with nature. While in practice, relational values and partnership with nature are thus often characterized by the same observations, conceptual separation between values and HNRs allows us to appreciate the complexity of real-world interactions and avoid stereotyping individuals as operating in only one kind of HNR or value.

Enacting a HNR in a specific role and context involves interacting with a suite of other valued natural entities (cows, meadows, etc.). Together, the constellation of each of these individual relations (valued relationally, instrumentally, or intrinsically or all three ways at once), embodied and enacted in a particular context (the role of farmer, on your grandparent’s land for example), constitutes a specific HNR. At the same time, a HNR constitutes a way of approaching each individual relation. To be a partner with nature constitutes a set of virtues, attitudes and practices that align with those of relational values. To be a manager constitutes these relations in a more instrumental way.

As an individual human moves between different roles within their life or even within their day, they too move between different relationships to nature, and engage with natural entities that they value in different ways (guiding tourists on skis to observe wildlife in the morning, focusing on participating and observing nature, assuring not to disturb it; returning home to do the work of the farm, attending to the relationship with each cow, calling her by her name, petting her and checking that she is well, knowing that these animals make up a livelihood). It is in this sense that we understand human-nature relationships and values of nature to co-constitute each other.

Partnership and relational values share conceptual foundations

In our previous work, we defined six components of relational values that characterize their bidirectionality (Chapman and Deplazes‐Zemp Citation2023). The three components of the intrinsic directionality (genuine respect and care) that relational values share with intrinsic values, consisted of 1) an attitude of respect, 2) attention to the relationship and 3) practices of care. These components have a loose correspondence to the virtues we defined in the partnership relationship: respect to restraint, attention to responsiveness and care to responsibility. Where the relational values components are focused on a specific relationship, the human-nature relationships focus on more overarching virtues. Turning now to the components of the instrumental directionality (eudaimonic contribution to wellbeing) which relational values share with instrumental values, we defined 4) emotional and experiential contributions, 5) satisfaction and joy in the relationship, and 6) practical contributions. Here the connection can be seen between these specific components and the eudaimonic elements described as part of partnership. In the case of relational values, each of these components applied to what has been valued in the interaction with a particular natural entity (e.g. farmed animals, hunted animals, or the place that farmers lived and worked). In the current paper, we have described how these specific relational values can be understood to exist within a broader umbrella concept of partnership with nature. At the same time the fact that we do speak of values explains what aspects of partnership are considered to be desirable and the reference to virtues indicates what is expected of an appropriate partnership relationship with nature.

The three elements that we highlighted to characterize partnership were 1) bidirectionality, 2) nature as a subject and 3) the collaboration with nature. All of these elements remind us of relational values. In this respect we align with Knippenberg and coauthors’ (2018) suggestion that partnership with nature is based on the same underlying idea as relational values. We agree with Muradian and Pascual (Citation2018) that certain ways of relating to nature (in their framework ‘relational modes’) are more closely associated with particular categories of values (intrinsic, instrumental or relational); however, where they propose that values are derived from relational modes, we see HNR and values as co-constituting each other.

Insights for policymaking and practice

Understanding and working with a diversity of human-nature relationships shows how there are many ways to consider and care for nature. Aligning policies with the different ways that target groups understand their relationship to nature could contribute to a better understanding of the specifics and challenges of the respective project and facilitate greater acceptance and more enthusiastic participation of local stakeholders. While in some contexts a blurry boundary concept such as stewardship is sufficient, we see that in other contexts, there is value in being specific about the kinds of pro-environmental relationships. For example, policies such as financial incentives presume a manager HNR and instrumental values as primary. In contexts such as our study where people’s lives and livelihoods are deeply intertwined with and reliant on nature, the HNR of ‘partnership’ may form a more effective orientation. Policymaking would then focus on acknowledging dependence on nature as well as learning from the ways that different people care for and respect nature. For example, payments for ecosystem services may benefit from a focus on what land managers give to nature, framing financial payments as a contribution rather than a payment (Leimona et al. Citation2015; Chapman et al. Citation2020). Taking seriously the non-material contributions of people to nature (e.g. in the form of ceremonies or attitudes, including ontologies, see Nadasdy Citation2007) is another approach in line with our suggestion to align policy with specific human-nature relationships. Collaborative approaches (e.g. participatory, transdisciplinary) create more space for understanding and incorporating the specific human-nature relationships and values of the societal actors involved (Horcea-Milcu Citation2022; Pascual et al. Citation2023). Fundamentally, a deeper understanding of specific human-nature relationships could be expressed as a shift in mindsets of advisors and practitioners, changing how they think about the individuals and groups they are working with – and as a consequence how they engage and communicate. In order to do justice to different Western and non-Western worldviews and to incorporate elements of sustainable practices into other cultures and policies, we need to be able to understand how different elements of these worldviews come together and interact. We hope that our analysis and characterization of different HNR and their association with environmental values can support such approaches.

Conclusion

The idea of partnership with nature might offer a valuable guide to a more relational approach to conservation. Here we have developed the partnership concept in the context of conservation activities specific to agriculture. Should partnership serve as a guiding idea for other contexts of conservation? When and how? And when not? We certainly see this tendency to move in the direction of a more collaborative approach to conservation. Further research could explore what partnership might look like in other contexts and its potential to guide conservation in diverse applications and cultural constellations but also potential limits of the partnership relations and situations where conservation might require other relationships. We propose invoking the idea of partnership as a potential leverage point and focus of conservation within agricultural contexts and perhaps beyond.

Supplementary Information_R1.docx

Download MS Word (163.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We first with to thank all our interview respondents who generously lent us their time, shared their thoughts and reflections, and sometimes their farm products with us! Angelika Abderhalden, Flurina Walter and Norman Backhaus provided generous input and assistance with this research. A warm thank you goes to our local collaborators the UNSECO Biosphere Reserve Engiadina Val Müstair, Pro Terra Engiadina and the local offices of Plantahof. Colleagues at the University Research Priority Program on Global Change and Biodiversity of the University of Zurich provided valuable discussions on this topic. Alana McPherson (https://www.iamsci.com/) created the beautiful figures of human-nature relationships. This research was supported by grants from the NOMIS Foundation, the University of Zurich Postdoc Grant (FK-18-101), as well as the University Research Priority Program on Global Change and Biodiversity of the University of Zurich. Thanks as well for the helpful comments from two anonymous reviewers and the editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2024.2374757.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. AMBIO. 46(1):30–16. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Attfield R. 2003. Environmental ethics an overview for the twenty-first century. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bauer N, Wallner A, Hunziker M. 2009. The change of European landscapes: human-nature relationships, public attitudes towards rewilding, and the implications for landscape management in Switzerland. J Environ Manage. 90(9):2910–2920. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.01.021.

- Bennett EM, Reyers B. 2024. Disentangling the complexity of human–nature interactions. People Nat. 6(2):402–409. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10611.

- Braito MT, Böck K, Flint C, Muhar A, Muhar S, Penker M. 2017. Human-nature relationships and linkages to environmental behaviour. Environ Values. 26(3):365–389. doi: 10.3197/096327117X14913285800706.

- Buijs A, Fischer A, Muhar A. 2018. From urban gardening to planetary stewardship: human–nature relationships and their implications for environmental management1. J Environ Plann Manage. 61(5–6):747–755. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2018.1429255.

- Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould RK, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain SC, et al. 2016. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113(6):1462–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525002113.

- Chan KMA, Boyd DR, Gould RK, Jetzkowitz J, Liu J, Muraca B, Naidoo R, Olmsted P, Satterfield T, Selomane O, et al. Bridgewater P, Bridgewater P. 2020. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2(3):693–717. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10124.

- Chapman M, Deplazes‐Zemp A. 2023. ‘I owe it to the animals’: the bidirectionality of Swiss alpine farmers’ relational values. People Nat. 5(1):147–161. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10415.

- Chapman M, Satterfield T, Wittman H, Chan KMA. 2020. A payment by any other name: is Costa Rica’s PES a payment for services or a support for stewards? World Dev. 129:104900. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104900.

- Comberti C, Thornton TF, Wyllie de Echeverria V, Patterson T. 2015. Ecosystem services or services to ecosystems? Valuing cultivation and reciprocal relationships between humans and ecosystems. Global Environ Change. 34:247–262. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.007.

- Country B, Wright S, Suchet-Pearson S, Lloyd K, Burarrwanga L, Ganambarr R, Ganambarr-Stubbs M, Ganambarr B, Maymuru D, Sweeney J. 2015. Co-becoming Bawaka. Prog Hum Geogr. 40(4):455–475. doi: 10.1177/0309132515589437.

- de Groot WT. 1992. Environmental science theory: concepts and methods in a one-world, problem-oriented paradigm. In: Studies in Environmental Science. Vol. 52, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

- de Groot M, Drenthen M, de Groot WT. 2011. Public visions of the human/nature relationship and their implications for environmental ethics. Environ Ethics. 33(1):25–44. doi: 10.5840/enviroethics20113314.

- Deplazes-Zemp A. 2022. Are people part of nature? Yes and no: a perspectival account of the concept of ‘nature. Environ Ethics. 44(2):99–119. doi: 10.5840/enviroethics202242736.

- Deplazes-Zemp A. 2023. Beyond Intrinsic and Instrumental: third-category value in environmental ethics and environmental policy. Ethics Policy & Environ. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/21550085.2023.2166341.

- Deplazes-Zemp A, Chapman M. 2021. The ABCs of relational values: environmental values that include aspects of both intrinsic and instrumental valuing. Environ Values. 30(6):669–693. doi: 10.3197/096327120X15973379803726.

- Deplazes-Zemp A, Michel A, Oliveri T, Schneiter R, Thaler L, Backhaus N. (Under Review). Natural processes and natureculture – a relational understanding of nature amongst local stakeholders in Swiss parks. Ecosyst People.

- Dobbs TL, Pretty JN. 2004. Agri-environmental stewardship schemes and “Multifunctionality. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 26(2):220–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9353.2004.00172.x.

- Dunlap RE, Van Liere KD, Mertig AG, Jones RE. 2000. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. J Social Issues. 56(3):425–442. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00176.

- Ebenreck S. 1983. A partnership farmland ethic. Environ Ethics. 5(1):33–45. doi: 10.5840/enviroethics19835139.

- Enqvist JP, West S, Masterson VA, Haider LJ, Svedin U, Tengö M. 2018. Stewardship as a boundary object for sustainability research: linking care, knowledge and agency. Landsc Urban Plan. 179:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.005.

- Eversberg D. 2021. The social specificity of societal nature relations in a flexible capitalist society. Environ Values. 30(3):319–343. doi: 10.3197/096327120X15916910310581.

- Eversberg D, Koch P, Holz J, Pungas L, Stein A. 2022. Social relationships with nature: elements of a framework for socio-ecological structure analysis. Innov: The Eur J Soc Sci Res. 35(3):389–419. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2022.2095989.

- Flint CG, Kunze I, Muhar A, Yoshida Y, Penker M. 2013. Exploring empirical typologies of human–nature relationships and linkages to the ecosystem services concept. Landscape Urban Plann. 120:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.09.002.

- Geist C, Galatowitsch SM. 1999. Reciprocal model for meeting ecological and human needs in restoration projects. Conserv Biol. 13(5):970–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98074.x.

- Gordon LJ, Bignet V, Crona B, Henriksson PJG, Van Holt T, Jonell M, Lindahl T, Troell M, Barthel S, Deutsch L, et al. 2017. Rewiring food systems to enhance human health and biosphere stewardship. Environ Res Lett. 12(10):100201. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa81dc.

- Himes A, Muraca B. 2018. Relational values: the key to pluralistic valuation of ecosystem services. Curr Opin Sust. 35:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.09.005.

- Horcea-Milcu A-I. 2022. Values as leverage points for sustainability transformation: two pathways for transformation research. Curr Opin Sust. 57:101205. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2022.101205.

- Kaebnick GE. 2014. Humans in nature: the world as we find it and the world as we create it. Oxford, New York: OUP USA.

- Kikiloi K, Graves M. 2010. Rebirth of an archipelago: sustaining a Hawaiian cultural identity for people and homeland. Hulili: Multidisplinary Res On Hawaii Well-Being. 6:73–114.

- Knippenberg L, de Groot WT, van den Born RJ, Knights P, Muraca B. 2018. Relational value, partnership, eudaimonia: a review. Curr Opin Sust. 35:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.022.

- Lee K. 1999. The natural and the artefactual: the implications of deep science and deep technology for environmental philosophy. Laham, Boulder, New York, Oxford: Lexington Books.

- Leimona B, van Noordwijk M, de Groot R, Leemans R. 2015. Fairly efficient, efficiently fair: lessons from designing and testing payment schemes for ecosystem services in Asia. Ecosystem Services. 12:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.012.

- Manfredo MJ, Teel TL, Dietsch AM. 2016. Implications of human value shift and persistence for biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol. 30(2):287–296. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12619.

- Mathevet R, Bousquet F, Raymond CM. 2018. The concept of stewardship in sustainability science and conservation biology. Biol Conserv. 217:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.015.

- Merchant C. 2004. Reinventing eden: the fate of nature in Western Culture. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203497623.

- Merchant C. 2015. Autonomous nature: problems of prediction and control from ancient times to the scientific revolution 196. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315680002.

- Muhar A, Böck K. 2018. Mastery over nature as a paradox: Societally implemented but individually rejected. J Environ Plann Manage. 61(5–6):994–1010. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2017.1334633.

- Muradian R, Pascual U. 2018. A typology of elementary forms of human-nature relations: a contribution to the valuation debate. Curr Opin Sust. 35:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.014.

- Nadasdy P. 2007. The gift in the animal: the ontology of hunting and human–animal sociality. Am Ethnol. 43(1):25–43. doi: 10.1525/ae.2007.34.1.25.

- Neuteleers S. 2020. A fresh look at ‘relational’ values in nature: distinctions derived from the debate on meaningfulness in life. Environ Values. 29(4):461–479. doi: 10.3197/096327119X15579936382699.

- Opdam P. 2017. How landscape stewardship emerges out of landscape planning. In: Bieling C Plieninger T, editors. The science and practice of landscape stewardship. Cambridge University Press; p. 331–346. 10.1017/9781316499016.033.

- Palmer C. 1992. Stewardship. In: Ball I, Goodall M, Palmer C, and Reader J, editors. The Earth Beneath. London: SPCK; p. 67–87.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Anderson CB, Chaplin-Kramer R, Christie M, González-Jiménez D, Martin A, Raymond CM, Termansen M, Vatn A, et al. 2023. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature. 620(7975), Article 7975. 813–823. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06406-9.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Christie M. 2023. Editorial overview: leveraging the multiple values of nature for transformative change to just and sustainable futures — Insights from the IPBES values assessment. Curr Opin Sust. 64:101359. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2023.101359.

- Pascual U, Balvanera P, Díaz S, Pataki G, Roth E, Stenseke M, Watson RT, Dessane EB, Islar M, Kelemen E, et al. 2017. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Curr Opin Sust. 26–27:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Pungas L. 2022. Who stewards whom? A paradox spectrum of human–nature relationships of Estonian dacha gardeners. Innov: The Eur J Soc Sci Res. 35(3):420–444. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2022.2095990.

- Seitzinger SP, Svedin U, Crumley CL, Steffen W, Abdullah SA, Alfsen C, Broadgate WJ, Biermann F, Bondre NR, Dearing JA, et al. 2012. Planetary stewardship in an Urbanizing World: Beyond City Limits. AMBIO. 41(8):787–794. doi: 10.1007/s13280-012-0353-7.

- Singh NM. 2015. Payments for ecosystem services and the gift paradigm: Sharing the burden and joy of environmental care. Ecol Econ. 117:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.06.011.

- Soper K. 1995. What is nature? Culture, politics and the non-human p. Oxford Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell. http://library.lincoln.ac.uk/items/4402.

- Sundberg J. 2014. Decolonizing posthumanist geographies. Cult Geogr. 21(1):33–47. doi: 10.1177/1474474013486067.

- van Den Born RJG. 2008. Rethinking nature: public visions in the Netherlands. Environ Values. 17(1):83–109. doi: 10.3197/096327108X271969.

- Vogel S. 2016. Thinking like a mall: environmental philosophy after the end of nature | mitpressbookstore. The MIT Press. https://mitpressbookstore.mit.edu/book/9780262529716.

- Welchman J. 2012. A defence of environmental stewardship. Environ Values. 21(3):297–316. doi: 10.3197/096327112X13400390125975.

- West S, Haider LJ, Masterson V, Enqvist JP, Svedin U, Tengö M. 2018. Stewardship, care and relational values. Curr Opin Sust. 35:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.008.