ABSTRACT

Purpose: Digital storytelling (DST), broadly speaking, is a storytelling method that is interwoven with digital media. It is commonly used in educational settings or human services to support various sorts of social advocacy. While many of these DST practices have devised methods to engage marginalized groups to express their voices, they lack parallel initiatives to enable audiences to understand those voices. This study examined a story-retelling workshop model called StoryAd, which utilizes productions from DST activities to facilitate face-to-face contact. The workshop itself is also a lite version of DST activity. Method: A pilot study was conducted in Hong Kong in 2019. Participants enrolled online, met offline, and their advertisement ideas might go online and contribute back to the stories. The workshop model was evaluated using a one-group pretest-posttest design. The participants were 45 Hong Kong Chinese, aged 18-60. Results: Participants’ critical thinking disposition, self-esteem, perspective-taking, and curiosity toward new information increased, while their need for cognitive-closure decreased. Discussion and Conclusion: This study has proved the feasibility and acceptability of the workshop model. It also opens the discussion about extending DST pedagogy to engage and influence story-readers.

Digital storytelling (DST) is a storytelling method that is interwoven with selected digitized images, texts, sounds, and/or other digital elements. It is commonly used in human services to promote stories from marginalized groups (Chan & Sage, Citationin press; Chan & Yau, Citation2019). The term DST sometimes refers to a specific genre, for example, a video lasting a few minutes (Lambert, Citation2010). It is also used as a general umbrella term (Botfield, Newman, Lenette, Albury, & Zwi, Citation2017; Chan & Yau, Citation2019) covering different sorts of digital production activities. These may be referred to by various terms such as “youth media production” (Johnston-Goodstar, Richards-Schuster, & Sethi, Citation2014) or “photovoice” (Catalani & Minkler, Citation2010).

There are diverse DST models (Botfield et al., Citation2017; de Jager, Fogarty, Tewson, Lenette, & Boydell, Citation2017) serving different purposes, but a common characteristic of many DST activities is their social advocacy mission. This is partly because of the powerful distribution capability of the internet: many education practitioners and human service practitioners have become aware of the potential of using DST to enable marginalized groups such as ethnic minorities, patients, refugees, and people with HIV to have their voices heard (Chan, Citationin press; Chan & Holosko, Citation2019; Emert, Citation2013; Guse et al., Citation2013; Mnisi, Citation2015; Stacey & Hardy, Citation2011; Stenhouse, Tait, Hardy, & Sumner, Citation2013; Teti, Conserve, Zhang, & Gerkovich, Citation2016). However, most DST practices focus on helping protagonists (storytellers) gain insights and self-confidence, and it is not clear how these stories can equally impact their audiences. DST practitioners also acknowledge that little is known about how digital stories are used once they are in circulation in the public domain (Lenette, Cox, & Brough, Citation2015), let alone how these stories can facilitate anti-prejudice education among the public.

Some DST practitioners have therefore included public screening sessions in their program designs, aiming to enable protagonists from marginalized groups to meet their audiences face-to-face. In some way, these digital stories function like trailers, introducing the real persons and issues behind these productions. For example, Stacey and Hardy (Citation2011) reported a project in which student nurse storytellers joined the audience discussion about the story. Stenhouse et al. (Citation2013) worked on a project in which early-stage dementia storytellers joined the screening, discussed with audiences, and received feedback. Teti et al. (Citation2016) reported a photovoice project in which women with HIV were the storytellers, some of whom attended the final photo exhibit and chatted with the audience. A heuristic example is the case of the Human Library (https://humanlibrary.org/), which encourages people to “borrow” a storyteller (called a “Human Book”) to meet readers face-to-face. The Human Library is not usually considered an example of DST. However, it inspires the discussion here, and it is a digital story in some way – if we see the group’s website as an epic story introducing their decade-long anti-prejudice education movement.

These storytelling initiatives have a tacit assumption that it is desirable for storytellers to meet their readers face-to-face, and that direct contact can have some “magical power” in decreasing social distance and prejudices. While this is true to a certain extent (Orosz, Bánki, Bőthe, Tóth-Király, & Tropp, Citation2016), the actual situation is far more uncertain and complicated. It has long been pointed out that mere face-to-face contact between different social groups may not guarantee positive outcomes, and that such direct contact may in fact ruin the situation instead of easing tension or reducing social prejudice. Williams (Citation1964) suggested that contact between groups under prevailing superiority-inferiority arrangements do not encourage changes in attitudes and behavior. In short, thoughtless arrangements may encourage the continuation and entrenchment of dominant-subordinate relationships. In general, in intergroup communications, each side needs to see the point of view of the other side; otherwise the contact may become counterproductive. Various studies have shown that the conditions in which face-to-face contact occurs are crucially important. These include spatial designs, collaborative tasks, and communication protocols (Holmes & Butler, Citation1987; McClendon & Eitzen, Citation1975).

While many of these DST practices have devised methods to engage marginalized groups to express their stories, they lack corresponding initiatives to enable audiences to understand those stories. Even in the case of the Human Library, the process or steps of the face-to-face contact are not clearly theorized, and there is extremely scant research reporting its effectiveness (e.g., Orosz et al., Citation2016 is one the few studies).

Taken together, in DST, neither online distribution nor face-to-face contact per se can ensure social impact. It may be the pedagogical arrangements that make a difference, but this is an under-developed area in the literature. This study aimed to take a step toward opening the discussion by examining how a story-reading workshop model can be an extension of DST practice, and to what extent it can help promote open-mindedness among audiences.

Background of the story-reading workshop model

The study examined a half-day story-reading workshop model called StoryAd, which utilizes selected products from previous or existing DST activities. The workshop itself is also a lite version of DST activity. Different StoryAd workshops have their own topics, guests, and brainstorming activities, but they follow the same structure and expect the same learning outcomes. In brief, they enable participants (i.e., story-readers) to create advertisements for specific digital stories. Participants have an opportunity to meet the storyteller face-to-face, and are provided with basic textual and media materials related to the story. Participants then brainstorm advertising ideas to introduce that story. Good ideas are selected, awarded, and used to further development of that story. In other words, this workshop model posits story-readers as active participants producing their feedback to selected digital stories.

StoryAd is one of the core components of a web-based project (jchumanlibrarieshub.asia or humans.asia) launched in January 2019, which was funded by a charity trust in Hong Kong. The website is operated by a university. This web-based project aims to enable the public to deepen their understanding of various kinds of real-life stories, and to promote social connectedness and inclusiveness. Three core components are associated with this web-based project. First, it publishes stories featuring people who have faced a critical challenge in their lives, such as a disability, a gender identity issue, or a mental illness. These online stories are systematically displayed on the website, with texts, multimedia, and related references. Users (such as schools or NGOs) can invite the protagonists of these stories for face-to-face conversations. Second, it organizes digital storytelling workshops to help protagonists curate their stories. Selected stories may be published on the website. Third, it organizes story-reading workshops to enable general readers to deepen their understanding of particular stories. The StoryAd workshop model is the common framework informing the design of these story-reading workshops, and was the focus of the study reported in this article.

Theoretical framework and process steps

Narrative and media

This workshop model is based on the theoretical foundations of Narrative Practice (NP). The overall aim of NP is to help participants deconstruct dominant but “thin” storylines (incoherent, unreasonable, unhelpful), and thicken subordinate but “thick” storylines (coherent, reasonable, helpful). A key presumption is that human experiences are not simply facts, but stories, in which events are selected and organized for a particular audience (Riessman & Quinney, Citation2005, p. 394). Stubborn prejudices are caused by internalized hegemonic storylines that are unhelpful or counterproductive, and there is a range of well-established conversational techniques that serve to explore subordinate storylines (Duvall & Béres, Citation2011; White, Citation2007). It is assumed that participants will become more aware of alternative voices, potential options, as well as their own strengths.

A range of NP conversation techniques has been developed by different groups and practitioners (Duvall & Béres, Citation2011; White, Citation2007). For example, a core technique is “re-authoring conversation” (White, Citation2007), which presumes a story contains two landscapes: the landscape of action (LOA), and the landscape of identity (LOI). LOA refers to a sequence of concrete events within the plot. It is assumed that zigzagging between these two levels of landscape can reroot storylines because overlooked but significant life events can be drawn together again, enabling protagonists to construct new meanings.

Another example, also a core technique adopted by the workshop model, is Outsider Witnesses (OW) (White, Citation2007, pp. 165–218). While NP assumes there are rituals that judge and degrade people’s lives, and rituals that acknowledge and regrade people’s lives, OW provides protagonists with the option of telling their stories in front of an audience of outsider witnesses. These outsider witnesses respond to these stories with retellings that are shaped by a specific protocol. These witnesses’ retellings offer resonance, yielding an experience of their lives as joined around shared and precious themes. This ceremony has a three-part structure: the protagonist tells his/her story, the outsider witnesses (audience) retell that story, and the protagonist retells the audiences’ retellings. In these protagonist-audience conversations, the facilitator asks a set of structured questions to coach both sides. Four interrelated question categories are used (White, Citation2007, pp. 190–191): (i) identifying the expression (e.g., Which parts of the story particularly caught your attention?); (ii) describing the image, (e.g., What images of lives did this story evoke in your mind?); (iii) embodying responses (e.g., Which aspects of your own life experiences resonated with this story?); (iv) acknowledging transport (e.g. Do you have any new ideas/insights after commenting on this story? What are these ideas?).

The common logic behind these various NP conversational techniques is reflective scaffolding. NP practitioners have related these conversational skills to Vygotsky’s theory (Vygotsky, Citation1978), noting that it is possible to apply the concept of scaffolding to explain all narrative practice conversational skills, and that such a concept also serves as a guide in the further development of these conversations (White, Citation2007, p. 282). First, Vygotsky contends that meaning-making relies on symbolic mediators – the tool and sign system that mediates the social and psychological processes of thinking. Storytelling is therefore deemed to be a powerful symbolic mediator in these processes. Second, Vygotsky’s concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) refers to the difference between what a person can learn unaided, and what s/he can learn with support from another person, such as a teacher or social worker. This idea of assisting learners is known as scaffolding. In fact, Vygotskian scaffolding is also commonly used to explain the learning process in media production practice (Buckingham, Citation2003; Goodman, Citation2003). Essentially, NP can be seen as a conceptual scaffold for a facilitator to guide participants (both an individual and/or a group) to develop their interpretations from the concrete to the abstract, and vice versa. Such a scaffold elicits recurring deductive-inductive cycles that disrupt participants’ existing ideas, and allow them to reconstruct their ideas (e.g., reinforce, revise, reject).

Based on NP’s theoretical and methodological foundations, the workshop model also rationalizes the use of digital communication media to offer new practice possibilities and/or enhance practice methods (Chan, Citation2016, Citation2018; Chan & Holosko, Citation2016, Citation2018; Chan & Yau, Citation2019). For example, O2O (online-offline) interactions, asynchronous communication, information collection, media editing, and posting feedback.

The analogy of Lego bricks may help further explain the role of digital media in such a narrative process. Imagine a Lego house (i.e., an idea) consisting of 100 Lego bricks (i.e., the symbolic components constituting that idea), of different sizes, colors and shapes. It may be difficult to purely imagine dismantling this house and using the same 100 Lego bricks to construct a robot (i.e., a revised idea). However, it is easier for someone to see and touch these Lego bricks via hands-on activities, and then restructure them into another artifact. Likewise, it is easier to change our view if we can “see” our thinking, and be guided by a more competent collaborator in such a process. As such, digital media can help people visualize and rework the Lego bricks.

Overall, the process steps and key concepts of this workshop model can be summarized by four Cs: Community, Conversation, Content, and Circulation. These will be further elaborated in the following sections.

Step 1: community – a story community inviting talents to create ads

StoryAd uses a website to provide participants with a background understanding of the workshop. The major steps in the initial phase are as follows:

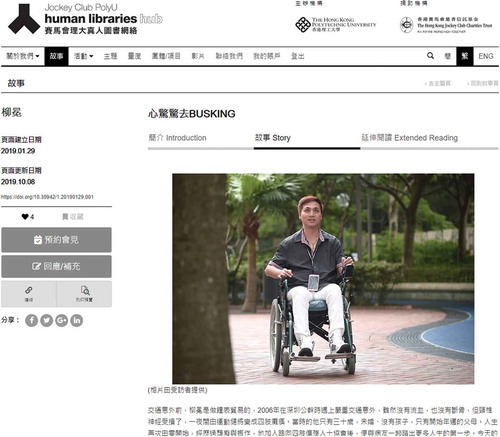

A webpage introduces the event, showing a specific story (see for a screencap of an example of story page) with a specific theme. The overall objective of the event is recruiting talented people (i.e., workshop participants) to create advertisements for selected digital stories.

Participants enroll online.

Participants can access the stories online, and access related textual and/or multimedia materials.

Participants will learn the date, time and place of a face-to-face session in which they will meet the protagonist and brainstorm advertising ideas together.

Step 2: conversation – participants identifying unique storylines

The half-day workshop is usually conducted in a room with a computer, a projection screen, and internet connection. In some way, a standard classroom perfectly fits this purpose. The OW technique (White, Citation2007, pp. 165–218) is used to inform workshop conversations. The major steps in this conversation phase are as follows:

First, the protagonist tells his/her story. The workshop facilitator interviews the protagonist and facilitates as participants ask questions to clarify any aspects of the plot and/or factual information. The protagonist can also reference his/her story online whenever appropriate. For example, the protagonist may wish to show particular photos or statements. Participants can search for additional information about the protagonist online while meeting the protagonist. On some occasions, storytellers can opt to share via video conferencing. However, all storytellers covered in this study were engaged in face-to-face conversations.

Second, workshop participants recap the story shared by the protagonist. The workshop facilitator guides this process. Four interrelated question categories are used: (1) identifying the expression (e.g., Which parts of the story particularly caught your attention?); (2) describing the image, (e.g., What images of lives did this story evoke in your mind?); (3) embodying responses (e.g., Which aspects of your own life experiences resonate with this story?); (4) acknowledging transport (e.g. Do you have any new ideas/insights after commenting on this story? What are these ideas?).

Finally, the protagonist responds to participants’ accounts of his/her story. The workshop facilitator invites the protagonist to respond to the workshop participants’ accounts. This telling and retelling cycle is also facilitated by a simple production-based activity. This will be introduced in the following section.

Step 3: content – producing the advertisement ideas

In StoryAd, participants help brainstorm advertising ideas for the story presented in the workshop. In this study, participants were asked to suggest a title for the story they had just listened to, and choose a photo they think best represented the story. The general steps of the final phase of the workshop are as follows:

The facilitator divides participants into small groups (2–3 participants per group).

Each group is provided with color pens, large size white paper, and a hyperlink to an online album showing a pool of photos related to the story/protagonists.

Group members discuss and brainstorm a title for the story, and choose a photo that they think best represents the story. They are also allowed to collage and/or edit these photos using their own devices, such as mobile phone apps (see for an example).

Participants are allowed to revisit the online story and/or search for further information related to the protagonist at any time during the workshop.

Each group writes their ideas on large size white paper using color pens.

Step 4: circulation – presenting ideas and getting feedback

Each group presents an idea using the large size paper and the computer screen to show the specific photo they have chosen (or created).

All presentation materials are posted on a wall or whiteboard.

The facilitator invites the protagonist to comment on the presented ideas, with reference to the same set of OW questions: (1) Which parts of these suggested ideas particularly caught your attention? (2) What images of lives did these ideas evoke in your mind? (3) Which aspects of your own life experiences resonated with these ideas? (4) Do you have any new ideas/insights after commenting on these ideas?

The facilitator and the protagonist discuss these ideas and choose the best one.

Winners of the best idea award may receive coffee coupons, and their ideas may inform revisions and/or development of these story pages on the website.

Method

Pretest-posttest design

The program was evaluated using a one-group pretest-posttest design. Two waves of assessment were successfully conducted: Timepoint 1 (T1) – before participants accessed the online reading materials; Timepoint 2 (T2) – after the final presentations (OT1 – X – OT2). Self-reporting questionnaires and observers’ ratings were used. Although the O-X-O design is usually seen as weak in internal validity, it can help provide some timely evaluation data. The whole notion of using such a story workshop is new, and this study was an essential formative step before any rigorous experimental design could be properly rationalized and implemented.

The workshops

This study aimed to research some core learning outcomes that were expected to be achieved across different workshops regardless of theme. The story themes were used as a heuristic and instrumental device in this study. It covered four StoryAd workshops held between May and June 2019, which included a transgender story, a story from a father with an autistic boy, and a story from a non-typical social worker. Each workshop focused on a particular story, and they were held in the venues of two NGOs, a commercial firm, and a university. All workshops followed the three-phase model noted earlier, and participants worked on the same assignment. All groups were therefore treated as a single group in the study.

In addition, the study adopted some of the intervention fidelity strategies noted by Tucker and Blythe (Citation2008) to ensure that the program was implemented as planned. These included: (a) Training: the Principal Investigator (PI) of the research received NP training, taught NT courses, and worked as the core facilitator of the workshops; (b) Supervision: the project team met pre-event and post-event to ensure all procedures and conversations were in line with protocols based on textual materials available; and (c) An operation guide: a definitive set of conversation skills were stressed.

Participants

All participants enrolled online via the firms or agencies they belong to, including two human service professional organizations, one social service organization, and one information technology company. Research consent was obtained when they submitted the enrollment form. Forty-five participants were engaged in the workshops between May and June 2019. Their ages ranged from 22 to 60 years old (M = 33.60, SD = 9.27), of whom 24 were female and 21 were male. Seventeen participants held a master’s degree or above, twenty held a bachelor’s degree, seven held an associate degree or equivalent, while the highest academic level of one was unknown.

Data collection

Selected background socio-demographic data were collected at the time of online enrollment before T1, including gender, age, and academic level. Self-reporting measures were collected via online questionnaires at T1, and T2.

Measures

Three constructs were used to assess participants’ need for closure, critical thinking, and perspective-taking ability. In addition, two questions were used to assess positive attitude toward oneself, and curiosity toward new information.

Need for Closure (NFC), also referred to as the Need for Cognitive Closure, refers to an individual’s aversion toward ambiguity, and desire for a firm and clear answer to a question (Webster & Kruglanski, Citation1994). This was measured by a shortened 15-item Need for Closure Scale (Roets & Van Hiel, Citation2011). The Chinese version of this scale demonstrated proper psychometric properties (Moneta & Yip, Citation2004). A higher NFC score indicated a stronger need for cognitive closure.

Critical Thinking Disposition (CTD) was measured by the critical openness sub-scale (including seven rating questions) in the Critical Thinking Disposition Scale (Sosu, Citation2013). The subscale was translated into Chinese and used in a previous pilot study researching DST (Chan & Holosko, Citation2019). A higher CTD score indicated a stronger critical thinking disposition.

Perspective-taking ability was measured by the perspective-taking sub-scale (including seven rating questions) in the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, Citation1983). The Chinese version of the index also exhibited acceptable psychometric properties among adolescents in Hong Kong (Siu & Shek, Citation2005). A higher score indicated more acceptance of others’ perspectives.

Positive attitude toward oneself was measured by a typical question extracted from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1979). The question was “I take a positive attitude toward myself”.

Curiosity toward seeking new information was assessed by a question from the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II (Ye, Ng, Yim, & Wang, Citation2015). The question was “I actively seek as much information as I can in new situations”.

The response sets of all the scales used in this study were configured in 10-point ranges, in which 1 = extremely disagree, and 10 = extremely agree. They were adjusted in order to fit participants’ frames of reference, and therefore to enhance instrument reliability (Coelho & Esteves, Citation2007). Targeted participants were local citizens, most of whom grew up in the local school system which uses 100 marks to represent full marks in an assignment. All participants were therefore assumed to be familiar with percentile-based assessment frameworks. As such, it was assumed that a 10-point scale would be more consistent with students’ prior experiences, rather than other numeric scale-ranges. All scales measuring psychometric properties reported good-to-excellent test-retest reliability: CTD, r = .84, N = 44; NFC, r = .90, N = 44; perspective-taking ability, r = .72, N = 20; positive attitude toward self, r = .85, N = 20; curiosity, r = .89, N = 20.

Study hypotheses

Based on the noted theoretical foundations, this study hypothesized that participants will be more aware of different opinions, information and perspectives. As such, three directional hypotheses were formulated: Hypothesis 1 – Need for Closure (NFC) scores will decrease from T1 to T2; Hypothesis 2 – Critical Thinking Disposition (CTD) scores will increase from T1 to T2; Hypothesis 3 – Perspective-taking ability will increase from T1 to T2.

The study reported in this paper applied an intervention method to benefit participants in self-perception and curiosity. Two hypotheses were formed using this method: Hypothesis 4 – Positive attitude toward oneself will increase from T1 to T2; Hypothesis 5 – Level of curiosity toward seeking new information will increase from T1 to T2.

Analysis

Results from the pretest and posttest were analyzed and compared, and significance of mean difference was measured by paired sample t-tests. Analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 25.

Results

The results were in line with our hypotheses, with small-to-medium effect sizes (see ).

Table 1. Differences of pretest-posttest results of the participants (N = 45).

Finding 1: The NFC scores decreased significantly after the intervention (−0.24, p = .03, d = −.33). This finding indicated that participants became less close-minded after the workshops.

Finding 2: The CTDS scores increased significantly after the intervention (+0.30, p = .01, d = .41). This finding indicated that participants became more aware of diverse information sources.

Finding 3: The scores on perspective-taking ability increased significantly after the intervention (+0.47, p < .001, d = .58). The perspective-taking score showed the largest effect size among all measures. This finding showed that participants were more open to other perspectives after the workshops.

Finding 4: The level of curiosity toward seeking new information increased significantly after the intervention (+0.33, p = .04, d = .31). This finding indicated that participants were more interested in searching for new information after the workshops.

Finding 5: The positive attitude toward oneself increased significantly after the intervention (+0.36, p = .01, d = .40). This finding showed that participants in the workshop had a more positive view about themselves after the workshops.

Discussion

Overall, the pretest-posttest results showed that learning outcomes were induced as planned. This is initial evidence which indicates the workshop’s acceptability and feasibility. This in turn means that the workshop model may be used to promote critical openness among workshop audiences. However, this is not yet generalizable. In this study, the sample size was small. In addition, a more rigorous research design, such as an RCT, will be required. Further, this is a working method developed in a particular sociocultural context. Last but not least, additional hypotheses and assessments will be required to examine to what extent program outcomes can or cannot be sustained. These limitations notwithstanding, it seems more important to discuss how some of the workshop arrangements, particularly the fusion of reflective conversations and digital media, might have created new opportunities, and hence contributed to these outcomes.

First, the StoyAd model turns audiences into active coauthors. In StoyAd, participants are not posited as the ignorant public who are waiting for someone to educate them. Instead, they are talented individuals with curiosity, who want to know more about other people’s stories, and want to take part. In some way, they are not passive audience members, but potential collaborators. Of course, the workshops do not really expect participants to be real experts or professional artists. In this study, participants were ordinary people. In addition, it is not possible to expect workshop participants to be bias-free. This overall positioning is a matter of packaging. However, it does not mean they have not learned from the workshops. On the contrary, results showed that the attitude of workshop participants changed and their open-mindedness increased. Also, they suggested interesting short titles/captions that helped highlight unique features of the stories that were significant in the view of the audience, but which might have been undervalued by the storytellers themselves.

The findings revealed some evidence that workshop participants did not feel that they were being talked down to. Participants’ positive attitude toward themselves increased significantly after the intervention (see Finding 5). This is encouraging, as the workshop was indeed intended to influence its participants, who did become more open-minded. As noted early in this article, contacts between groups under superiority-inferiority arrangements do not encourage changes in attitudes and behavior (Williams, Citation1964). These well-established studies are a reminder that a condescending attitude hoping to educate the public may not be welcomed by that public.

StoryAd aims to collect ideas to advocate selected social agendas. This position is subtle, and it may make a big difference. This recruiting-talented-people orientation is partly achieved by a clear indication on the event webpage, which helps contextualize the nature of the event and the role of the participants. Recent research studies have generally noted that the online communities a person has participated in can affect that person’s imagined audiences, and hence self-expression (Chan, Citation2006, Citation2010; Dahya, Citation2017; Kedzior & Allen, Citation2016). The public image of the website helps shape this prior positioning, and such positioning presets the nature of subsequent face-to-face contact. That is, a communication context can never be neutral. StoryAd practitioners proactively used digital media to set a context that is in line with specific educational goals.

Second, the guided-conversations help ensure purposive dialogs (rather than monologues). The findings indicated that participants became less close-minded, more aware of diverse information sources, more interested in searching for new information, and more open to others’ perspectives (see Finding 1 to Finding 4). This is initial evidence that participants’ critical openness increased after the workshop. These outcomes are partly contributed by the dialogic processes that facilitate openness and a non-judgmental attitude. As noted at the beginning of the article, conditions in which face-to-face contact occurs are crucially important (Holmes & Butler, Citation1987; McClendon & Eitzen, Citation1975).

In this workshop model, the facilitator mediates the protagonist and the story-readers. The conversation format follows a structured progression from the concrete to the abstract. The facilitator invites the protagonist to provide comments with reference to a definite question sequence: by first asking which parts of the story particularly caught their attention, then asking about what aspects of participants’ own life experiences resonated with those story episodes. These questions do not serve to elicit opinions, but experiences. This structured process can help avoid participants sharing groundless comments or purely personal opinions which may potentially side-track (or ruin) the conversations.

In addition, the conversations are also partly mediated by the internet. In the digital age, communication content can be visualized: they are synchronous/asynchronous, searchable and retrievable. These characteristic features enable ideas to be externalized and reviewed (Chan & Holosko, Citation2019; Chan, Ngai, & Wong, Citation2012). The prevalence of mobile phone technologies has greatly enhanced the feasibility of the O2O strategy. O2O (“Online to Offline”, also “Offline to Online”) indicates a two-way flow between the online and the physical worlds. For example, participants can respond to online questionnaires, search online for additional information about the protagonists while meeting those protagonists, and small group events can be webcasted to reach broader audiences.

In StoryAd, participants can search online for additional information about the protagonists while meeting those protagonists. Talking about the photos or information online is an essential O2O interaction which basically formulates a scaffold that cues the story-readers to construct meaning based on concrete happenings. The media texts also enable the story-readers to recall the story and elaborate on their ideas.

Third, the StoryAd model has demonstrated the feasibility of a practice that uses digital media production to enhance dialogs, addressing both personal reflections and social discourses. Such a dual-focus orientation echoes an emerging stream of DST literature which has noted this potential but has not yet proposed appropriate methods (Lenette et al., Citation2015; Markus, Citation2012; Stacey & Hardy, Citation2011; Wijnen & Wildschut, Citation2015). StoryAd illustrates how the convergence of content production, circulation and feedback has endowed digital stories with a dual-focus potential, making changes at both the micro-level (e.g., individual storytellers themselves) and the macro-level (e.g., groups of story-readers in communities) (Chan & Holosko, Citation2019; Chan & Yau, Citation2019).

Participants developed ideas to advertise/summarize specific stories. Winning ideas did inform the revisions and development of these story pages on the website. There were occasions when the comments/production ideas inspired the protagonists to change the photos and finetune some of the content. They used convenient mobile apps to illustrate initial ideas, and leave complicated editing work to a later stage (in case their ideas were adopted). Our observation was that most participants could easily download photos to their own mobile phones and do some rough editing to illustrate their ideas. This kind of low-tech requirement is particularly suitable for the general public, who do not have time or competence to independently work on sophisticated media production, yet can still take part in developing the story page. As such, this story-reading workshop model can be applied in classrooms and in many other public settings.

Digital communication media provides strong authoring and associative capabilities (Chan, Citation2016; Chan & Holosko, Citation2017). Media content can be produced and edited using user-friendly computer software and mobile apps. Moreover, it can be circulated beyond storytellers’ immediate contexts, reaching broader audiences. Furthermore, storytellers can also absorb new ideas from readers/viewers. The internet has already blurred the private-public boundary (Livingstone, Citation2005; West, Lewis, & Currie, Citation2009). For example, expressing personal voices on one’s personal account on social media also implies expressing voices in public. Individual internet service users could have a critical mass of friends online whose face-to-face communications could be enhanced by online communications. Another thought-provoking example is Wikipedia, which demonstrates how a media text can be forever fluid and scalable in such feedback loops.

Concluding remarks

It is after nightfall, there is a campfire under a starry sky. A storyteller rises, and all eyes turn to the face of that storyteller, illuminated by the flickering light. The story begins. Each of us imagines the events that are being described. Archeological findings dating back thousands of years have found community meeting sites where our ancestors gathered around a fire (Clark & Harris, Citation1985). In every culture, people learned to share their stories, aspirations, and dreams.

In the digital age, story-reading has new possibilities. Our campfire is now the whole world. The technological revolution has sparked a renaissance in storytelling, as well as story-reading. We can search for a story and provide our feedback in ways our ancestors could never have imagined. We can recap statements, reedit photos or recall a video segment. We can even make a video recording of ourselves, and mingle images and music. We can do all this within reach of a smartphone, in face-to-face or distance communication contexts.

In these StoryAd workshops, we see the actualization of these possibilities. Each of the themes in the discussion section (e.g., setting an online community, using O2O communications, producing advertisement ideas to provide feedback) has purposefully included educational pedagogical components and technical features related to digital media. Such an idea is inspired by the concept of affordance, which presumes that the utility of a tool (i.e., digital media) is dependent not merely on the intrinsic features of that tool, but also on the social actors’ intentions (Gibson, Citation1977; Norman, Citation1999). This concept has been widely applied in a range of studies examining the interaction between humans and technology (Bower, Citation2008; Chan & Ngai, Citation2019; Hammond, Citation2010; Leonardi, Citation2011). As such, these themes can help highlight the ways purposive conversations may need a human facilitator, and why digital stories or face-to-face talking per se may not automatically create these conversation experiences for story-readers.

The story-reading practice introduced in this article only requires some minimal use of digital media, while relying mostly appropriate micro-level coaching. The potential of such a workshop model can be actualized if practitioners can take an informed position using technologies. This opens an underdeveloped research area concerning the consumption aspect of digital stories in DST. In some way, the story of digital storytelling turns a new page. Yet, it is an empty stage, a blank page, waiting for your contribution.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this paper was partially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. 15604018). The media distribution platform (Jockey Club PolyU Human Libraries Hub) used in the study was funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Botfield, J. R., Newman, C. E., Lenette, C., Albury, K., & Zwi, A. B. (2017). Using digital storytelling to promote the sexual health and well-being of migrant and refugee young people: A scoping review. Health Education Journal, 77, 735–748. doi:10.1177/0017896917745568

- Bower, M. (2008). Affordance analysis – Matching learning tasks with learning technologies. Educational Media International, 45, 3–15. doi:10.1080/09523980701847115

- Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education: Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. Cambridge, England: Polity.

- Catalani, C., & Minkler, M. (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education and Behavior, 37, 424–451. doi:10.1177/1090198109342084

- Chan, C. (2006). Youth voice? Whose voice? Young people and youth media practice in Hong Kong. McGill Journal of Education, 41, 215–225.

- Chan, C. (2010). Revisiting the ‘self’ in self-directed inquiry learning: A heuristic case study of an independent media production directed by students. The International Journal of Learning, 17, 131–144. doi:10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v17i04

- Chan, C. (2016). A scoping review of social media use in social work practice. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 13, 263–276. doi:10.1080/23761407.2015.1052908

- Chan, C. (2018). ICT-supported social work interventions with youth: A critical review. Journal of Social Work, 18, 468–488. doi:10.1177/1468017316651997

- Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2018). Technology for social work interventions. In E. Mullen (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies in social work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195389678-0263

- Chan, C., & Yau, C. (2019). Digital storytelling for social work interventions. In E. Mullen (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies in social work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195389678-0273

- Chan, C. (in press). Using digital storytelling to facilitate critical thinking disposition in youth civic engagement: A randomized control trial. Children and Youth Services Review.(advance online version) doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104522

- Chan, C., & Holosko, M. (2019). Utilizing youth media practice to influence change: A pretest-posttest study. Research on Social Work Practice, 1–12. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1049731519837357

- Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2016). A review of information and communication technology enhanced social work interventions. Research on Social Work Practice, 26, 88–100. doi:10.1177/1049731515578884

- Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2017). The utilization of social media for youth outreach engagement: A case study. Qualitative Social Work, 16, 680–697. doi:10.1177/1473325016638917

- Chan, C., Ngai, K.-H., & Wong, C.-K. (2012). Using photographs in narrative therapy to externalize the problem: A substance abuse case. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 31(2), 1–20. doi:10.1521/jsyt.2012.31.2.1

- Chan, C., & Ngai, S. S. Y. (2019). Utilizing social media for social work: Insights from clients in online youth services. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33, 157–172. doi:10.1080/02650533.2018.1504286

- Chan, C., & Sage, M. (in press). A narrative review of digital storytelling for social work practice. Journal of Social Work Practice.

- Clark, J. D., & Harris, J. W. (1985). Fire and its roles in early hominid lifeways. The African Archaeological Review, 3, 3–27. doi:10.1007/BF01117453

- Coelho, P. S., & Esteves, S. P. (2007). The choice between a fivepoint and a ten-point scale in the framework of customer satisfaction measurement. International Journal of Market Research, 49, 313–339. doi:10.1177/147078530704900305

- Dahya, N. (2017). Critical perspectives on youth digital media production: ‘Voice’ and representation in educational contexts. Learning Media and Technology, 42, 100–111. doi:10.1080/17439884.2016.1141785

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal Of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113-126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

- de Jager, A., Fogarty, A., Tewson, A., Lenette, C., & Boydell, K. M. (2017). Digital storytelling in research: A systematic review. Qualitative Report, 22, 2548–2582.

- Duvall, J., & Béres, L. (2011). Innovations in narrative therapy: Connecting practice, training, and research. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- Emert, T. (2013). ‘The transpoemations project’: Digital storytelling, contemporary poetry, and refugee boys. Intercultural Education, 24, 355–365. doi:10.1080/14675986.2013.809245

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting and knowing (pp. 67–82). Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum.

- Goodman, S. (2003). Teaching youth media: A critical guide to literacy, video production and social change. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Guse, K., Spagat, A., Hill, A., Lira, A., Heathcock, S., & Gilliam, M. (2013). Digital storytelling: A novel methodology for sexual health promotion. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 8, 213–227. doi:10.1080/15546128.2013.838504

- Hammond, M. (2010). What is an affordance and can it help us understand the use of ICT in education? Education and Information Technologies, 15, 205–217. doi:10.1007/s10639-009-9106-z

- Holmes, M. D., & Butler, J. S. (1987). Status inconsistency, racial separatism, and job satisfaction: A case study of the military. Sociological Perspectives, 30, 201–224. doi:10.2307/1388999

- Johnston-Goodstar, K., Richards-Schuster, K., & Sethi, J. K. (2014). Exploring critical youth media practice: Connections and contributions for social work. Social Work, 59, 339–346. doi:10.1093/sw/swu041

- Kedzior, R., & Allen, D. E. (2016). From liberation to control: Understanding the selfie experience. European Journal of Marketing, 50, 1893–1902. doi:10.1108/EJM-07-2015-0512

- Lambert, J. (2010). Digital storytelling cookbook (4th ed. ed.). Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press.

- Lenette, C., Cox, L., & Brough, M. (2015). Digital storytelling as a social work tool: Learning from ethnographic research with women from refugee backgrounds. British Journal of Social Work, 45, 988–1005. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct184

- Leonardi, P. M. (2011). When flexible routines meet flexible technologies: Affordance, constraint, and the imbrication of human and material agencies. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 35, 147–167. doi:10.2307/23043493

- Livingstone, S. (2005). Mediating the public/private boundary at home: Children’s use of the internet for privacy and participation. Journal of Media Practice, 6, 41–51. doi:10.1386/jmpr.6.1.41/1

- Markus, S. F. (2012). Photovoice for healthy relationships: Community-based participatory HIV prevention in a rural American Indian community. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: the Journal of the National Center, 19, 102–123. doi:10.5820/aian.1901.2012.102

- McClendon, M. J., & Eitzen, D. S. (1975). Interracial contact on collegiate basketball teams: A test of Shérifs theory of superordinate goals. Social Science Quarterly, 55, 926–938.

- Mnisi, T. (2015). Digital storytelling: Creating participatory space, addressing stigma, and enabling agency. Perspectives in Education, 33, 92–106.

- Moneta, G. B., & Yip, P. P. Y. (2004). Construct validity of the scores of the Chinese version of the need for closure scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64, 531–548. doi:10.1177/0013164403258446

- Norman, D. A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions, 6, 38–43. doi:10.1145/301153.301168

- Orosz, G., Bánki, E., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Tropp, L. R. (2016). Don’t judge a living book by its cover: Effectiveness of the living library intervention in reducing prejudice toward Roma and LGBT people. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46, 510–517. doi:10.1111/jasp.12379

- Riessman, C. K., & Quinney, L. (2005). Narrative in social work: A critical review. Qualitative Social Work, 4, 391–412. doi:10.1177/1473325005058643

- Roets, A., & Van Hiel, A. (2011). Item selection and validation of a brief, 15-item version of the need for closure scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 90–94. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.004

- Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Siu, A. M. H., & Shek, D. T. L. (2005). Validation of the interpersonal reactivity index in a Chinese context. Research on Social Work Practice, 15, 118–126. doi:10.1177/1049731504270384

- Sosu, E. M. (2013). The development and psychometric validation of a critical thinking disposition scale. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 9, 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2012.09.002

- Stacey, G., & Hardy, P. (2011). Challenging the shock of reality through digital storytelling. Nurse Education in Practice, 11, 159–164. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2010.08.003

- Stenhouse, R., Tait, J., Hardy, P., & Sumner, T. (2013). Dangling conversations: Reflections on the process of creating digital stories during a workshop with people with early-stage dementia. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20, 134–141. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01900.x

- Teti, M., Conserve, D., Zhang, N., & Gerkovich, M. (2016). Another way to talk: Exploring photovoice as a strategy to support safe disclosure among men and women with HIV. Aids Education and Prevention, 28, 43–58. doi:10.1521/aeap.2016.28.1.43

- Tucker, A. R., & Blythe, B. (2008). Attention to treatment fidelity in social work outcomes: A review of the literature from the 1990s. Social Work Research, 32, 185–190. doi:10.1093/swr/32.3.185

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Webster, D. M., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1994). Individual differences in need for cognitive closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Personality Processes and Individual Differences, 67, 1049–1062. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1049

- West, A., Lewis, J., & Currie, P. (2009). Students’ Facebook ‘friends’: Public and private spheres. Journal of Youth Studies, 12, 615–627. doi:10.1080/13676260902960752

- White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Wijnen, E., & Wildschut, M. (2015). Narrating goals: A case study on the contribution of digital storytelling to cross-cultural leadership development. Sport in Society, 18, 938–951. doi:10.1080/17430437.2014.997584

- Williams, J. A. (1964). Reduction of tension through intergroup contact: A social psychological interpretation. The Pacific Sociological Review, 7, 81–88. doi:10.2307/1388531

- Ye, S., Ng, T. K., Yim, K. H., & Wang, J. (2015). Validation of the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory–II (CEI–II) among Chinese university students in Hong Kong. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97, 403–410. doi:10.1080/00223891.2015.1013546