ABSTRACT

Purpose

This study identified the nature of social work practice in primary health care and described the reported patient outcomes, benefits, challenges, and enablers of social work in general practice [GP] settings.

Method

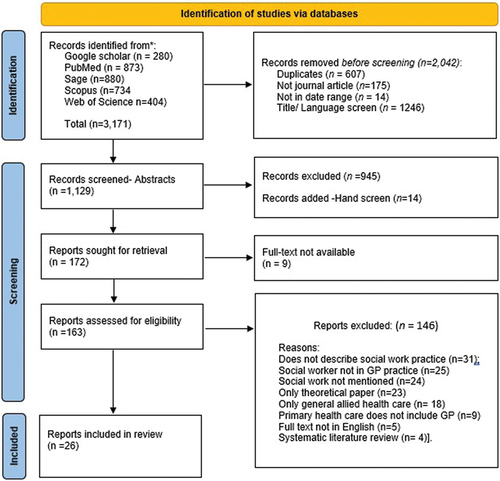

A systematic literature review applying the Prisma framework was conducted.

Results

A total of 26 studies met the inclusion criteria. Social work practice in GP assists in delivering positive health outcomes for patients, improved patient care, offers value for money, and supports interdisciplinary teams. Identified challenges include funding impediments, organizational barriers, and a lack of understanding of and undervaluing the social work role.

Discussion and Conclusions

The review outlined the benefits of social work practice in GP practices; however, these must be further evidenced. Funding for social workers in primary health care was identified as a challenge when it was lacking, and as an enabler when it was available. Further research to evidence the patient outcomes and overall benefits, the fiscal value of social work and funding pathways in primary health care is recommended.

An increasing number of people seeking medical help present with complex needs which go beyond the traditional scope of generalist medical care. Moreover, an aging population puts increasing strain on the health system with a looming crisis in community-based health services (Shah et al., Citation2017). Medical practitioners often lack the time and resources to adequately address the psychosocial aspects of a patient’s care. This presents a barrier for effective engagement with out-of-clinic services, creates health service demand, leads to multiple hospital readmissions and creates unnecessary stressful situations for health professionals and patients. Inadvertently, this may adversely impact the medical treatment and recovery of patients (Ruth & Marshall, Citation2017).

Social workers can add professional expertise to the general practice [GP] team, enhance professional practice, and reduce burnout in adjoining health disciplines (Samuel & Thompson, Citation2018). For example, general practitioner’s involvement in social needs assessment can be reduced when social workers and registered nurses are employed in GP practices (Donelan et al., Citation2019). Social work inclusion in GP can lead to positive patient outcomes. Studies indicate improvements in self-management of chronic ill-health, reduced psychosocial morbidity, client improvement on measures of distress, and addressing barriers for health maintenance and treatment (McGregor et al., Citation2018; Shah et al., Citation2017).

While social work could play a critical role in GP, further work is required to identify the contribution of social work in primary health care (McGregor et al., Citation2018). This systematic literature review explored what existing studies reported on social work interventions within General Practice [GP]. The review was undertaken to understand the nature of social work practice in GP clinics, examining the outcomes, benefits, challenges, and enablers of such practice.

Background

Social work is a diverse profession, with practitioners working in a range of fields and settings, and is well established in hospital settings within Australia and internationally (Hartung & Schneider, Citation2016). Social work has a long history in health, with hospitals being an important venue for current and early social work (Ruth & Marshall, Citation2017). Social work in public health includes “direct clinical services; case finding and consultation; program planning; and research, training, and prevention in a public health framework” Ruth and Marshall (Citation2017, p. 53) Fraser et al. (cited in de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018, p. 69) identify three roles that social workers generally take on in primary health care settings: “(1) provision of behavioral health interventions; (2) management of care, especially for older adults and patients with chronic conditions; and (3) engagement with social service agencies on behalf of patients.” Within Australia, the scope of social workers’ practice in health settings includes bereavement, grief, and loss support work; risk assessment, and therapeutic interventions; socio-legal issues, and ethical decision-making; comprehensive discharge planning; therapeutic intervention in relation to a range of chronic health conditions; family intervention and support; case management; group work; advocacy and referral; psychoeducation; crisis intervention; and policy development and research (AASW, Citation2015). In the US, public health social workers have been actively involved in preventative health care, such as substance abuse, HIV, and child abuse prevention, chronic disease management, and toxic waste activism. They have been committed to servicing vulnerable populations, bringing a focus on mental health and trauma, and applying a wide lens to public health (Ruth & Marshall, Citation2017).

The focus of this study is on the contribution of social work to GP, rather than primary health care in general. Health reforms focus on increasing preventative and community-based treatment services (de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018), to lighten the burden on the more expensive hospital system. GP or family medicine is a medical specialty; a general practitioner has undergone specialist postgraduate education following their general hospital training. General practices have become more extensive, with most GP clinics consisting of 6–10 GPs ([RACGP] Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Citation2019). Small practices and practices owned by GPs are decreasing, with general practitioners increasingly working in larger clinics ([RACGP] Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Citation2019). This decline in GP-owned practices indicates a rise in corporate-owned clinics (Scott, Citation2017).

Currently, few social workers work in GP (Hartung & Schneider, Citation2016), with some international exceptions. In the US, social workers are increasingly employed in interprofessional health teams to work in GP settings. Public Health reforms in the US focused on interprofessional teamwork, community engagement, prevention, and care coordination (Ruth & Marshall, Citation2017). Social workers screen and assess patients’ needs, provide brief interventions, care management, and provide prevention and crisis interventions to address the social determinants of health and behavioral health problems (de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018). There is potential for more social workers in GP in Australia, where accredited mental health social workers “are one of the few designated allied health professional groups eligible to provide private mental health services to people with diagnosable mental health conditions, or people ‘at risk’ of developing mental health conditions under the Commonwealth Medicare initiative” (AASW, Citation2020, p. 2).

In Australia, GP is the most regularly accessed health setting, “with almost 90% of the population visiting their GP at least once a year,” but it only receives 7.4% of the total Government health funding (RACGP, Citation2019, p. 17). GP and their patients face various challenges including the aging population, an increase in chronic health conditions, the prevalence of mental health concerns, and inadequate health billing rebates (RACGP, Citation2019). Social workers can be beneficial to support the social health care and well-being for patients in GP clinics when there are complex care and health needs (Hudson, Citation2014).

Social work interventions can help alleviate psychosocial and mental health symptoms of patients (Craig et al., Citation2016). Craig et al. (Citation2016, p. 51) highlight that as “as a profession that specializes in the assessment and treatment of ... psychosocial comorbidities, social work is well positioned to address these needs through interdisciplinary teams.” A partnership approach between social workers and GPs can enable a holistic assessment of health concerns in the context of broader issues, such as lifestyle, housing, and family stressors (Hudson, Citation2014). The integration of social work into GP settings can focus on prevention, self-care, enhancing health care for patients and facilitating care in the community and people’s homes (College of Social Work). The Royal College of General Practitioners (College of Social Work. Royal College of General Practitioners, Citation2014). It can also help respond to social health issues, such as exploring pathways for referral and to responding to domestic violence, sexual assault, or homelessness that adversely affect people’s health (Campbell et al., Citation2009; Coid et al., Citation2016; Hwang, Citation2001; Koziol McLain et al., Citation2008).

Co-location of social workers in GP settings is a strategy to address the social needs of medical patients (Bako et al., Citation2021). Co-location refers to social workers being in the same space as another provider, but potentially not being fully integrated with one another. Co-location can involve shared “equipment, and staff for health and human services; coordinated care between services; or a partnership between health providers and human services providers” (Rural Health Information Hub, Citation2020). Health care reforms in the US and Canada include a strengthening of interprofessional health care teams to enhance the quality, access to and capacity of mental health care. Co-location is a key factor in integrated behavioral health care and in the US more than 230,000 social workers were collocated in primary care practices (Lombardi et al., Citation2019). The co-location of social workers in primary care is more than having a single point of access for services, it facilitates integration and coordination of care and providers (Barsanti & Bonciani, Citation2019), a key component of social work practice. Social workers in interdisciplinary teams can address the social determinants of health, considering the environmental and social factors that impact behavioral and physical health outcomes (de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018).

However, the integration of social work in primary health care is complex. Different working practices often make it difficult for social workers and GPs to establish connections and collaborate, even though investing into integrated care can achieve improvements in population health. Foster (Citation2017) highlighted that while GPs and social workers both deliver services to community members, funding of service and operation of the professions are quite different, “GPs account for their every minute seeing individuals in the surgery or home, whereas social workers are often focused on coordinating a number of different interventions around a family or frail person” (p. 416).

To date, there is very limited research and knowledge about social workers in GP. Importantly, both GPs and social workers are interested in health care systems that achieve positive health outcomes for people that are economically sustainable (College of Social Work. Royal College of General Practitioners, Citation2014). “Social workers have a vital role in building the strong, resilient communities that are needed” (COSW.RCOGP, Citation2014, p. 1). The aim of this systematic literature review was to ascertain the contributions, challenges, and context of social work practice in GP settings.

The following research questions were posed to assess the characteristics and quality of included studies and the extent, viability, and outcomes of social work practice in GP settings:

What are the characteristics (authors, country of origin, institution, and type of study) of included studies?

What is the nature of social work practice in GP practices?

What are the challenges and enablers of social work practice in GP practices?

What are the reported outcomes of social work practice in GP practices?

Materials and method

Primary health care is inclusive of various health care activities such as community dental, community health clinics, and antenatal and postnatal support in the community, for example. For this study, we were interested specifically in primary health care as delivered by social workers in GP practices, alongside general practitioners or family doctors. This is referred to as family medicine or practice in some countries.

Protocol

A study protocol based on the Prisma-P statement by Moher et al. (Citation2015) guided the study. In order to extract and record the data, a full-text screening tool was developed. The protocol and tool were explored by the coauthors to achieve agreement and integrate feedback of each author.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible research was defined as literature that reported on social work practice within GP practices. Australian and international English language peer-reviewed literature was included. The search date range was 2011 to 2020, and the database search was undertaken in September 2021. This 10-year period was considered adequate to access the most recent information and knowledge on this topic. Excluded from this review were papers that were not peer-reviewed, in a language other than English, and outside the date range. Other exclusion criteria included: not specifically exploring social work, but allied health care in general; social workers collaborating with GP practices, but not working within the practice; only a theoretical discussion on the potential of social work in primary health care.

Database searches

The search strategy was refined in conjunction with a research librarian to adapt concepts and identify the databases most useful to be searched (Moher et al., Citation2015). After consulting with a research librarian, the following databases were identified as most appropriate for the search: Informit, Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Sage, Taylor and Francis, and Google Scholar.

The following search string was applied, with varying modifications according to database-specific requirements: (“social work” OR “social work practice” OR “social worker”) AND (“general practice” OR “primary health care”). The citation and related article functions of the databases were utilized to search for further related results. The reference lists of relevant papers were hand-searched.

Data screening, extraction, and analysis

The screening and extraction of the data for this review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Citation2015). The data was extracted by the author one with the support of a pre-determined extraction form. The screening tool asked the researcher to check each paper against the inclusion criteria and identify the reason for exclusion if a criterion was not met. Included papers were categorized by the First Author: Year; Country of origin; Institution; Type of study; nature of social work practice; reported patient outcomes; Challenges and Benefits of social work practice in GP practice; Enablers of social work practice in GP practice and Recommendations. The results were cross-checked by the authors and a social work student on their placement. There was a 94.5% interrater reliability. The discrepancies or questions that arose with the remaining 4.5% (n = 14) studies were discussed until consensus was reached on the relevance and completeness of the data. Results were described and presented in tabular form (see ). The data about social work in GP practices was analyzed thematically (Granzino & Raulin, Citation2013). The resulting themes were presented in narrative form.

Table 1. Data extraction table.

The PRISMA (Citation2020) flowchart in provides an overview of the records identified, included and excluded and the reasons for exclusions (Page et al., Citation2021).

The search returned a total of 3,171 results. A pre-defined screening tool was used to screen the titles of those papers. In the identification phase, duplicates and studies that were either in the wrong date range, not in the English language, not a journal article or not on the general topic were removed (n = 2,042). In the first screen, all abstracts were reviewed for relevance, and 945 records were excluded. Handsearching resulted in the inclusion of 14 additional studies. A total of 172 studies were sought for retrieval; however, the full text was not available for 9 of them, resulting in the retrieval of 163 retrieved for a full-text screen. In the second screen, Author one assessed those articles for eligibility, with the second author and a placement student screening 10% of the included papers independently to ensure reliability. Any disagreement was discussed until consensus was reached. After this final screen, 26 papers met the criteria to be included in the review.

Study quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included qualitative papers was assessed with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative research (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). Quantitative research studies were assessed with the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Effective Public Health Practice Project, Citation2009) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Mixed Methods studies were assessed with both tools.

The CASP checklist considers the aims of the research, the appropriateness of the chosen qualitative method, the research design and recruitment strategy to address the aims of the research, the relevance of the data method in addressing the research issue, the consideration of relationship between researcher and participants, whether ethical issues had been taken into consideration, whether the data analysis was sufficiently rigorous, whether a clear statement of findings was provided, and the value of the research was discussed (CASP, Citation2018). The Effective Public Health Practice Project (Citation2009) tool rates the effectiveness of the studies via selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis

Studies applied quantitative (n = 13), qualitative (n = 10), and mixed methods (n = 3) (see ). The quantitative study scores were evaluated according to the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Citation2009) global rating scale of “strong” (no weak ratings), “moderate” (one weak rating), and “weak” (two or more) weak ratings. The criteria in the EPPHP require the study reporting in the papers to be ranked for bias, study design, cofounders, binding, data collection methods, withdrawal and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis. Three (Chan et al., Citation2018; Enguidanos et al., Citation2011; Safren et al., Citation2013) of the 13 quantitative studies were assessed as strong, six as moderate (Berger-Jenkins et al., Citation2019; Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Cornell et al., Citation2020; Horevitz & Manoleas, Citation2013; Rabovsky et al., Citation2017; Tadic et al., Citation2020) and four as weak (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Bench et al., Citation2020; Reckrey et al., Citation2015; Rehner et al., Citation2017).

Table 2. Methodological quality appraisal of the included studies.

The qualitative studies were assessed as strong in the global rating with the CASP (Citation2018) that achieved a score or 9 or 10, 6–8 were classified as moderate and less than 5 as weak. The CASP tool requires assessment of reporting in the article of the research aims, methodology, research design, recruitment strategy, data collection, relationship, ethical issues, data analysis, findings and value of research. Of the 10 qualitative studies, seven achieved a strong score (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Bina et al., Citation2018; Brown et al., Citation2016; Döbl et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Hawk et al., Citation2015) and three a weak score (Lahey et al., Citation2019; Mann et al., Citation2016; Reckrey et al., Citation2014).

Of the three mixed studies, one achieved a strong score (Saavedra et al., Citation2019), and two a weak score (Chang et al., Citation2018; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013).

Results

The aim of this systematic literature review was to ascertain the contributions, challenges, and context of social work practice in GP settings. The study objectives were to extrapolate the characteristics, nature, challenges, enablers, and reported outcomes of social work practice in GP practices. These are summarized in . Before reporting on the overall study objectives, the author affiliations and study types are reported to project a context for the results of this systematic literature review.

Author affiliation- country and institutions

Most authors of the included articles were associated with universities in the USA (n = 18), three originated from Canada, two from New Zealand, and one each from Ireland, Israel, and Mexico. Most articles (n = 20) included authors associated with universities in a range of disciplines; 11 studies had at least one author associated with social work, 10 with medicine and family medicine, 5 with population health, and 3 with nursing. The coauthors were associated with medical research centers (n = 5), medical centers/institutes (n = 5), health services (n = 2), and social services/the national social work office (n = 3).

Type of study

The studies included the applied quantitative (n = 13), qualitative (n = 10), and mixed methods (n = 3). The study design included case studies (n = 8), interviews (n = 6), surveys (n = 5), randomized trials (n = 3) document analysis (n = 2), cohort analysis (n = 1), and evaluation (n = 1)

Characteristics and nature of social work practice

Social work practitioners delivered a versatile range of services in the primary health care setting, including therapy and counseling (n = 18), case management (n = 17), addressing psychosocial issues (n = 12), training and education (n = 12), provision of support and care (n = 8), resource development and provision (n = 7), referral (n = 7), care planning (n = 6), leveraging linkages and advocacy (n = 5), information provision (n = 5), and group work (n = 5).

Case management was a commonly listed activity (n = 17), with authors including details about casework, coordination of health care, coordination of transition, advanced care planning, tailored interventions, chronic disease management, intake, needs, and risk assessment as part of the case management activities. Chan et al. (Citation2018) study, for instance, shows the social worker involved with “ ... an initial comprehensive intake with medical and behavioral team members, patient driven health goal setting, transitional care protocols when patients experience hospitalizations, medication management assessment, weekly panel review, and case management to address social determinants of health and other unmet needs” (p. 5).

Therapy and counseling were identified in 18 studies. This included counseling in specific fields of practice, such as counseling women who experienced intimate partner violence (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Saavedra et al., Citation2019), mental health counseling/therapy (Bina et al., Citation2018; Döbl et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Reckrey et al., Citation2014), treatment of mental, mood, or substance use disorders (Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Rehner et al., Citation2017) and family therapy (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018). It also included therapeutic interventions described in more general terms such as counseling (Chan et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Tadic et al., Citation2020; Rabovsky et al., Citation2017), problem solving therapy (Enguidanos et al., Citation2011; Horevitz & Manoleas, Citation2013), motivational interviewing (Brown et al., Citation2016; Horevitz & Manoleas, Citation2013; Mann et al., Citation2016; Rowe et al., Citation2017), working with reported behavior problems (Berger-Jenkins et al., Citation2019) and psychotherapy (Lahey et al., Citation2019).

Twelve studies described education and training activities, including training and education aimed at patients and their families, such as carer education (Chang et al., Citation2018), health education and skill building (Döbl et al., Citation2017), psychoeducation (Horevitz & Monoleas, Citation2013; Lahey et al., Citation2019; Rowe et al., Citation2017) (for example, depression and disease management link, HIV transmission), relaxation training (Horevitz & Monoleas, Citation2013; Mann et al., Citation2016; Safren et al., Citation2013) and education to improve health literary (Rehner et al., Citation2017) as well as education of staff and students and health promotion (Reckrey et al., Citation2014; Saavedra et al., Citation2019; Tadic et al., Citation2020).

Twelve studies highlighted that the social workers addressed psychosocial issues related to health and barriers to overall well-being (n = 12). Reckrey et al. (Citation2014, p. 340), for example, found that “ ... social workers’ extensive training and broad scope of practice gives them a unique ability to both assess patients’ psychosocial needs and develop collaborative treatment plans.” Some of the specific interventions highlighted included assisting with financial issues (n= 9), for example, obtaining benefits, access to medication, health insurance, food, and addressing unemployment. Additionally, legal issues, transport, lack of social support, relationship issues, addictions, abuse, and neglect concerns and housing were addressed. Assessing biopsychosocial needs influencing depressive symptoms and stress, including social exclusion, isolation, and addiction were also highlighted (n = 9). The provision of support and care (n = 8), resource development, and provision (n = 7), referral (n = 7), care planning (n = 6), leveraging linkages and advocacy (n = 5), and information provision (n = 5) were identified separately, but appear to relate to addressing psychosocial issues. Rabovsky et al. (Citation2017, p. 40) summarize the important role of the social worker as a resource broker, “helping patients obtain medications or insurance (social gradient) and assessing the need for and connecting patients to home health care services (social support).”

Challenges

Seventeen of the 26 included studies outlined the challenges of social work practice in primary health care, including lack of funding/resources (n = 11), organizational barriers (n = 9), lack of understanding of (n = 3), and undervaluing the social work role (n = 4), difficult to meet patients’ needs (n = 4), lack of attendance (n = 2), inadequate training (n = 1), and interdisciplinary work (n = 1).

Eleven studies listed lack of funding and/or resources as a challenge for social work practice in primary health care. Nine studies, with either qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method design listed workload issues, and time constraints as a concern, resulting in waiting lists, insufficient time with patients and the ability to provide counseling. For example, respondents in Ashcroft et al. (Citation2018, p. 100)’s quantitative research highlighted that “time restrictions resulting from long waiting lists, high demand for services, lack of resources, organizational policies, inadequate training, compassion fatigue, other health colleagues’ limited understanding of the social work role, and poor leadership” limited their ability to work within their full scope as a social worker. Ní Raghallaigh et al. (Citation2013) mixed-method research identified workload issues in a survey, which was then further highlighted in focus groups where participants shared concerns about waiting lists and the impact on patients.

Nine studies mentioned organizational barriers, including the difficulty of capturing social work in the administrative data bases (Rehner et al., Citation2017; Saavedra et al., Citation2019; Tadic et al., Citation2020), access to treatment rooms and allocation processes (Döbl et al., Citation2017; Mann et al., Citation2016; Rehner et al., Citation2017), management structures and policies (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013) and lack of access to information (Brown et al., Citation2016; Lahey et al., Citation2019).

Three studies (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013) listed the lack of understanding of the social work role as a challenge. This could lead to inappropriate referrals and/or complex referrals, with the comment “we have had enough of her” (Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013, p. 941) or when others were stuck (Mann et al., Citation2016). Parallel to this, social workers felt undervalued (Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Bina et al., Citation2018; Döbl et al., Citation2017; Saavedra et al., Citation2019).

Enablers of social work practice in GP clinics

The single most common factor in enabling social work practice in GP practices was when government funding was available and policy changes facilitated the integration of social work. Eighteen of the 26 studies stated that social work practice in primary health care was made possible because of changes to funding and legislation. The Affordable Care Act 2010 (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Chan et al., Citation2018; Horevitz & Manoleas, Citation2013; Mann et al., Citation2016; Rowe et al., Citation2017), the Gulf Regional Outreach Program (Rehner et al., 217), and the Veteran Health Administration (Chang et al., Citation2018; Cornell et al., Citation2020) were drivers in the US. as well as state government health care initiates (Bench et al., Citation2020; Tadic et al., Citation2020) in the US and Canada. Systematic pan-Canadian Primary Health Care reform in Canada (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018) also enabled funding. Other funding initiatives include programs established by the Secretary of Health in Mexico (Saavedra et al., Citation2019), primary care reform in Italy (Barsanti & Bonciani, Citation2019), the Health Strategy, and policies in Ireland (Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013), health care reforms in Israel (Bina et al., Citation2018); and the New Zealand Ministry of Health vision for Primary Health (Döbl et al., Citation2015). Other funding initiatives included reallocation of existing staff resources and clinical budget (Chan et al., Citation2018) and payer driven Care (Hawk et al., Citation2015).

Other enablers of social work practice include social work competencies (n = 7) including the articulation of the role of the social work profession, knowledge about health conditions, and adjusting to the health setting. Döbl et al. (Citation2017), for example, stress the importance of being able to communicate the social work role and articulation of the social work aims and skills and Rehner et al. (Citation2017) point out that social work staff acquire extensive knowledge about chronic health conditions in adjusting to the health setting. Horevitz and Manoleas (Citation2013) suggest that social work training will include learning on the job.

Organizational enablers include collaboration and relationship building with patients, the team, and the wider social service and health networks (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Döbl et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Mann et al., Citation2016; Reckrey et al., Citation2014), social work-specific referrals (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Mann et al., Citation2016; Rehner et al., Citation2017); adoption of a patient-centered medical model of care (Mann et al., Citation2016; Rowe et al., Citation2017); supervision and access to resources (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Döbl et al., Citation2017), more than one social worker in the setting (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018), strong support from the practices (Döbl et al., Citation2015), shared workspaces (Mann et al., Citation2016), universal patient records (Cornell et al., Citation2020); regular meetings (Reckrey et al., Citation2015) and the social worker as the primary clinician (Bench et al., Citation2020).

Reported outcomes of social work practice in GP

Benefits

The identified benefits of social work practice in primary health care relate to improved patient care, improved team effectiveness, and the value of money. Further studies pointed to the value of the knowledge that social workers contributed, and the possibilities for advocacy and referral.

The studies highlighted findings related to the improved patient outcomes, such as patient-centered care (n = 9) and wholistic health care (n = 6). Saavedra et al. (Citation2019, p. 1029) in their qualitative research, for example, stressed the value of the wholistic care that “ ... . social workers offer generally combines the physical, mental, emotional, and social aspects of a patient’s situation in ways that the care from other health care providers does not.” Other patient-related outcomes include addressing psychosocial needs (n = 5), addressing the barriers to patient care (n = 4), enhanced quality of care (n = 4), a decrease in unmet needs (n = 3) and advocacy. Mann et al. (Citation2016) highlight the improvements of the overall mental and social conditions that affect overall well-being and health and Cornell et al. (Citation2020) through their quantitative research point out that the social determinants of high-risk, high-need populations were addressed.

Seven studies identify the improved team effectiveness, including that the social worker is an asset to the team, mutual learning, and collaboration. Cornell et al. (Citation2020), for instance, highlight that social work provides a link between the various health teams. Additionally, noted is that social work skills meet the patients and referring provider needs (Lahey et al., Citation2019) and that social work participation led to improved inter-provider communication (Hawk et al., Citation2015).

Studies (n = 7) also point out the cost benefit of social work practice in primary health care. Some studies suggest that physicians’ time is freed from social needs assessment and care coordination (Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Cornell et al., Citation2020; Mann et al., Citation2016) and social work assists with minimizing unnecessary medical appointments (Lahey et al., Citation2019) leading to value for money in managing clients (Brown et al., Citation2016; Rowe et al., Citation2017). Other organizational fiscal benefits included addressing cost-related underuse of medication (Rabovsky et al., Citation2017) and reducing waiting lists (Lahey et al., Citation2019). Rowe et al. (Citation2017, p. 445) highlight that the “ongoing interaction with the patient and others as well as the time required to address the patient’s nonmedical needs” were significant, but subsequently often resulted in a secondary gain of time savings for the primary care practice and an overall cost saving.

Reported patient outcomes

Sixteen of the 26 studies reported on the patient outcomes of the social work intervention. The reported patient outcomes included improved disease control (n = 10), addressing the wider health challenges (n = 6), higher quality of life (n = 6), and self-determination (n = 1).

The improved disease control outlined in 10 of the studies related to positive behavior (Berger-Jenkins et al., Citation2019; Hawk et al., Citation2015; Lahey et al., Citation2019; Safren et al., Citation2013); reduced depression and anxiety scores, and expression of optimism (Bench et al., Citation2020; Lahey et al., Citation2019; Reckrey et al., Citation2014; Rehner et al., Citation2017; Rowe et al., Citation2017), stress management (Mann et al., Citation2016) decrease in hospital admissions (Cornell et al., Citation2020; Rowe et al., Citation2017), decrease in complications (Cornell et al., Citation2020), decrease in glucose levels (Mann et al., Citation2016; Rabovsky et al., Citation2017), weight loss (Enguidanos et al., Citation2011), and better medication regime and health outcomes in chronic health conditions (Lahey et al., Citation2019; Rabovsky et al., Citation2017; Reckrey et al., Citation2014; Rehner et al., Citation2017).

The findings about improved disease control are identified in both quantitative and qualitative studies. For example, positive behavior outcomes and reduced depression and anxiety scores, and expression of optimism are and better medication regime and health outcomes in chronic health conditions outcomes confirmed in four or five studies. Two of these studies have been appraised as methodologically weak, the other three or four, respectively, have been assessed as strong methodologically, strong qualitative or quantitative studies. Safren et al. (Citation2013) quantitative study, for instance, evidenced a reduction in HIV transmission behavior through pre and post intervention. Behavior change was also identified in Hawk et al. (Citation2015) methodologically strong qualitative study that involved interviews with representatives from GP practices, and in this study, while a change in behavior is indicated, it is a more general statement. The position of a medical social worker in a practice “was credited with improved interprovider communication and with improved patient outcomes related to behavioral health management” (Hawk et al., Citation2015, p. 181).

Eight studies highlighted addressing the wider health challenges as positive patient outcomes, including provision of holistic care (n = 3), self-care, and addressing patients’ social and emotional needs.

Recommendations

Recommendation included finding ways of describing the value and role of social work in GP settings through education, training, and research. Seven studies recommended that social work needed to evidence its usefulness, including recording the cost saving, role articulation, and data collection to capture social workers’ patient care. Studies stressed that it was important to articulate the social work role and establish social work in Primary Health Care clinics, for example, Ní Raghallaigh et al. (Citation2013), explained it in the following way “You have to fight to carve out a niche ... . You’re not specialist in any area. You’re an expert in everything but you specialize in nothing” (p. 940–94).

Eight studies made research recommendations, including researching the impact of social work in primary care practice in terms of reduction of overall health costs (Hawk et al., Citation2015; Lahey et al., Citation2019; Mann et al., Citation2016; Rowe et al., Citation2017), patient-centered outcomes (Reckrey et al., Citation2014; Tadic et al., Citation2020) and chronic disease control (Rabovsky et al., Citation2017). Other recommended research included addressing the non-physician satisfaction with the team approach (Reckrey et al., Citation2015) and exploring the social determinants of health and impact of health care processes (Cornell et al., Citation2020).

Subsequent recommendations centered around social work practice with patients, including social workers working with patients (Alvarez et al., Citation2018; Berrett-Abebe et al., Citation2020; Döbl et al., Citation2017; Enguidanos et al., Citation2011; Saavedra et al., Citation2019; Tadic et al., Citation2020), support, and supervision (Ashcroft et al., Citation2018; Ní Raghallaigh et al., Citation2013; Saavedra et al., Citation2019), valuing patients’ strengths (Rowe et al., Citation2017), emotional and physical health included in treatment plan (Rehner et al., Citation2017) and collaboration between Social work and Medical professional associations to help maximize scope of social work practice in primary health care (Tadic et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic literature review was to ascertain the contributions, challenges, and context of social work practice in Primary Health care, with a particular interest in GP settings. The 26 included studies were reviewed to determine the nature, patient outcomes, benefits, enablers, and challenges of social work practice in GP practices. Included in the review process were the recommendations of the studies and the methodological quality of the reporting.

The included studies highlight the positive health benefits that result for patients receiving social work interventions. Patient outcomes include outcomes that are difficult to quantify in terms of their impact on patients’ overall health, such as increased levels of supports, higher quality of life and self-determination. However, the studies have also shown improvements in disease control including tangible outcomes such as reduced depression and anxiety scores, expression of optimism (Bench et al., Citation2020; Lahey et al., Citation2019; Reckrey et al., Citation2014; Rehner et al., Citation2017; Rowe et al., Citation2017), decreased hospital admissions and decreased glucose levels (Mann et al., Citation2016; Rabovsky et al., Citation2017). Improved patient health outcomes combined with other benefits of social work practice, such as improved team function, and strengthening connections with other providers (Hawk et al., Citation2015) can provide an invaluable asset to the GP health care team. Allowing other health professionals to concentrate on delivering their core interventions, coupled with the cost-effectiveness of integrated care should make social work practice in GP settings very attractive to primary health care and policymakers. Knowing that hospital readmissions can be impacted by social workers in primary care settings (Cornell et al., Citation2020; Rowe et al., Citation2017), there is additionally an argument to be made for cost savings at the tertiary health care level by a greater social work presence in primary health care. This requires further research to evidence the long-term impact of social work interventions.

However, there are challenges, and these seem to relate to a large part to valuing and articulating social work practices. Social work practitioners need to be able to articulate what social work offers to primary health care, and the included studies have provided important sources of evidence for this. Similarly, valuing the social work profession by the wider primary care team is important, who should welcome the unique perspective, and approach that social work brings. Social work is well placed to undertake a holistic assessment of a patient’s situation, and this can be beneficial not only to the patient but the team care environment. There are implications for social work education and the profession in general, that can be drawn from this. First, social workers need to be able to articulate what social work has to offer in the health setting (Döbl et al., Citation2017). This needs to be embedded in social work training and graduate development. Additionally, the diversity of primary health care settings and the scope of social work practice within this environment presents challenges and benefits. Social work is a generalist profession, which uniquely positions it to respond to the wide range of patient psychosocial needs that may emerge within GP settings. There are however unique skills, knowledge, and experience that would benefit the practitioner in the primary health care setting due to the broad range of patients and needs that may emerge. While behavioral health care has been an important part of social work interventions in primary health care in the US, the social work role in primary health care could extend far beyond mental health interventions, and this is demonstrated in the included studies. Thus, social workers need to acquire knowledge and understanding specific to the health setting, such as knowledge about chronic health conditions (Rehner et al., Citation2017). This is part of ongoing professional development, and common to all social work practice due to generic and broad nature of social work and much training will include learning on the job (Horevitz & Manoleas, Citation2013).

The great majority of the studies were undertaken in the US and Canada, with 18 and 3 studies, respectively. Considering the research finding that government funding and policies are the single most important factor in enabling social work practice in primary health care, this is a logical correlation. More social workers operate in the US-based primary care practices than anywhere else (Lombardi et al., Citation2019), and the findings of this study highlight the importance of government funding to make this possible. This systematic literature review highlights the value of funding social work practice in primary health in terms of improved patient care and outcomes, which should be a core motivator in health care. Social work practice can enable holistic care for patients (Saavedra et al., Citation2019), ensuring that the psychosocial needs and social determinants of health are considered and addressed (Cornell et al., Citation2020; de Saxe Zerden et al., Citation2018). The implication for health policy and social work is the need to advocate for clear funding pathways to facilitate social work presence in GP practices to address patients’ wellbeing wholistically. Social work can be part of addressing the grand challenges that an aging population faces, assisting in disease control, emotional, and social well-being and building a health system that looks after all, including the most vulnerable. Social work’s mission and values augment its professional skills and knowledge and the cost of setting up a health system that includes social work in GP practices will be offset by the overall patient wellbeing and the other positive contributions made to interdisciplinary health teams.

A recommendation for future research is about being specific and targeted in exploring and evidencing the outcomes of social work practice in health. A specific finding, i.e. “reduced HIV transmission behavior” (Safren et al., Citation2013) might entice funders more to consider finance-specific social work interventions, then more general statements such as ‘improved behavioral health management (Hawk et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, both types of study outcomes are needed to paint a full picture of social work practice and its outcomes and the benefits of including social work in the specific and generic health care widely. Methodologically strong studies will provide useful data to show where social work efforts are achieving positive outcomes. Improvement in overall social well-being is harder to evidence then the healing of physical ailments, but it is important to take the time to include and record pre and post assessment in service delivery and measure outcomes that matter to public health providers and clinicians. This data and research would enable evidence for social work to be recognized and further integrated in primary health care. This research has identified studies that have evidenced improved disease control through social work intervention, however more evidence can be built as overall, in a 10-year period, only 20 studies were identified that explored social work in GP practices and reported on patient outcomes. It will be useful to explore their methodologies, both qualitative and quantitative, to look at ways forward in evidencing the value of social work. Thus, for example, case studies can be useful, but at times need to be strengthened to outline the research aim, ethical considerations, the relationships, or recruitment strategies more clearly. Quantitative study quality ratings highlighted that more details about the study design, cofounders, and blinding can improve the quality assessment of some of the studies. The sector values evidence-based practice; in the same way as social workers need to be better in articulating the work they do; researcher can be more prolific and skilled in evidencing the contributions of social work.

Limitations

This systematic literature review only explored English language, peer-reviewed articles, and did not include unpublished or gray literature. Thus, further information could have been available that has not been included in this review. The range of terminology used for GP practices could have meant that not all relevant studies were captured; however, the number of included studies provide a facilitated anduseful synthesis of knowledge that met the aims of the research in terms of getting an understanding of social work practice in GP settings, the patient outcomes, enablers, and challenges. While the quality of the studies were assessed, these tools offer only a limited insight regarding risk of bias due to limited and inconsistent sources of data in the articles; thus, whether a study’s features relating to its design, conduct, or analysis puts it at risk of bias was not assessed (Wang et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, outcomes and benefits were at times based on self-reporting; it would be important to do further research to examine the outcomes and benefits more specifically and systematically.

The study did not explore the preparation of social workers, their training, and requirements to be licensed to practice. It is acknowledged that the term social worker could just have different meanings in different countries and settings, and this limits the interpretation of the results. Moreover, health care systems and policies across countries are very different, and thus the results must be considered in that light and cannot be generalized, but just provide indications and trends.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review analyzed the 26 included studies that reported on aspects of social work practice in GP settings. The findings highlight that social work practice assists in delivering positive health outcomes for patients, improved patient care, offers value for money, and supports interdisciplinary teams. The challenges highlighted in the studies include lack of funding pathways, organizational barriers, and a lack of understanding of and an undervaluing the social work role. Enablers of social work practice include funding, social work competencies, and knowledge, articulation of the social work role and relationship building. The results of this review can inform social work education and practice, as well as health practice, policy and research to facilitate the further inclusion of social work practice in GP settings. Further research is recommended to provide more systematic evidence of the patient outcomes, the overall benefits, and the fiscal value of social work in primary health care, as this will assist the development of social work practice and funding pathways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AASW. (2015). Scope of Social Work Practice. Social Work in Health. Australian Association of Social Workers. Retrieved from https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/8306.

- AASW. (2020). Accredited mental health social workers. Qualifications, skills and experience. Australian Association of Social Workers. Retrieved from https://www.aasw.asn.au/information-for-the-community/accredited-mental-health-social-workers

- Alvarez, C., Debnam, K., Clough, A., Alexander, K., & Glass, N. E. (2018). Responding to intimate partner violence: Healthcare providers’ current practices and views on integrating a safety decision aid into primary care settings. Research in Nursing & Health, 41(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21853

- Ashcroft, R., McMillan, C., Ambrose-Miller, W., McKee, R., & Brown, J. B. (2018). The emerging role of social work in primary health care: A survey of social workers in Ontario family health teams. Health & Social Work, 43(2), 109–117.

- Bako, A. T., Walter McCabe, H., Kasthurirathne, S. N., Halverson, P. K., & Vest, J. R. (2021). Reasons for social work referrals in an urban safety-net population: A natural language processing and market basket analysis approach. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(3), 414–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1817834

- Barsanti, S., & Bonciani, M. (2019). General practitioners: Between integration and co-location. The case of primary care centers in Tuscany, Italy. Health Services Management Research, 32(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951484818757154

- Bench, V. R., Beach, M., & Ren, D. (2020). Evaluation of an adapted collaborative care model for older adult depression severity reduction and quality of life improvement. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 17(5), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2020.1768193

- Berger-Jenkins, E., Monk, C., D’Onfro, K., Sultana, M., Brandt, L., Ankam, J., Vazquez, N., Lane, M., & Meyer, D. (2019). Screening for both child behavior and social determinants of health in pediatric primary care. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40(6), 415–424. https://I0.1097/DBP.0000000000000676

- Berrett-Abebe, J., Donelan, K., Berkman, B., Auerbach, D., & Maramaldi, P. (2020). Physician and nurse practitioner perceptions of social worker and community health worker roles in primary care practices caring for frail elders: Insights for social work. Social Work in Health Care, 59(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2019.1695703

- Bina, R., Barak, A., Posmontier, B., Glasser, S., & Cinamon, T. (2018). Social workers’ perceptions of barriers to interpersonal therapy implementation for treating postpartum depression in a primary care setting in Israel. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(1), e75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12479

- Brown, J. B., Ryan, B. L., & Thorpe, C. (2016). Processes of patient-centred care in family health teams: A qualitative study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 4(2), E271–276. DOl. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20150128

- Campbell, R., Dworkin, E., & Cabral, G. (2009). An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(3), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334456

- Chan, B., Edwards, S. T., Devoe, M., Gil, R., Mitchell, M., Englander, H., Korthuis, P. T. Korthuis, P. T. (2018). The SUMMIT ambulatory-ICU primary care model for medically and socially complex patients in an urban federally qualified health center: Study design and rationale. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0128-y

- Chang, E. T., Raja, P. V., Stockdale, S. E., Katz, M. L., Zulman, D. M., Eng, J. A., Hedrick, K. H., Jackson, J. L., Pathak, N., Watts, B., Patton, C., Schectman, G., & Asch, S. M. (2018, December). What are the key elements for implementing intensive primary care? A multisite veterans health administration case study. Healthcare, 6(4), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.10.001

- Coid, J. W., Ullrich, S., Kallis, C., Freestone, M., Gonzalez, R., Bui, L., Yang, M., Yang, M. (2016). Improving risk management for violence in mental health services: A multimethods approach. Programme grants for applied research. National Institute for Health Research. https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar04160

- College of Social Work. Royal College of General Practitioners. (2014). Gps and social workers: Partners for better care delivering health and social care integration together. A report by the college of social work and the royal college of general practitioners.Oct 2014. Retrieved from www.rcgp.org.uk/news/2014/october/~/media/Files/CIRC/Carers/Partners-for-Better-Care-2014.ashx

- Cornell, P. Y., Halladay, C. W., Ader, J., Halaszynski, J., Hogue, M., McClain, C. E., Silva, J. W., Taylor, L. D., & Rudolph, J. L. (2020). Embedding social workers in veterans health administration primary care teams reduces emergency department visits: An assessment of the veterans health administration program to add social workers to rural primary care teams. Health Affairs, 39(4), 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01589

- Craig, S., Frankford, R., Allan, K., Williams, C., Schwartz, C., Yaworski, A., Janz, G., & Malek-Saniee, S. (2016). Self-reported patient psychosocial needs in integrated primary health care: A role for social work in interdisciplinary teams. Social Work in Health Care, 55(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2015.1085483

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [CASP]. (2018). CASP Qualitative Research Checklist [online]. Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- de Saxe Zerden, L., Lombardi, B., Fraser, M., Jones, A., & Rico, Y. (2018). Social work: Integral to interprofessional education and integrated practice. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 10, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2017.12.011

- Döbl, S., Beddoe, L., & Huggard, P. (2017). Primary health care social work in Aotearoa New Zealand: An exploratory investigation. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 29(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol29iss2id285

- Döbl, S., Huggard, P., & Beddoe, L. (2015). A hidden jewel: Social work in primary health care practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Primary Health Care, 7(4), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC15333

- Donelan, K., Chang, Y., Berrett-Abebe, J., Spetz, J., Auerbach, D. I., Norman, L., & Buerhaus, P. I. (2019). Care management for older adults: The roles of nurses, social workers, and physicians. Health Affairs, 38(6), 941–949. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00030

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. (2009). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html

- Enguidanos, S., Coulourides Kogan, A., Keefe, B., Geron, S. M., & Katz, L. (2011). Patient-centered approach to building problem solving skills among older primary care patients: Problems identified and resolved. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(3), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2011.552939

- Foster, J. (2017). Thoughts on GPs and social workers. British Journal of General Practice, 67(662), 416. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X692441

- Grazino, A., & Raulin, M. (2013). Research Methods. A Process of Inquiry (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

- Hartung, M., & Schneider, N. (2016). Sozialarbeit und hausärztliche Versorgung: Eine Literaturübersicht. Zeitung Allgemeine Medizin (Z Allg Med), 92(9), 363–366. https://0.3238/zfa.2016.0363–0366

- Hawk, M., Ricci, E., Huber, G., & Myers, M. (2015). Opportunities for social workers in the patient centered medical home. Social Work in Public Health, 30(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2014.969862

- Horevitz, E., & Manoleas, P. (2013). Professional competencies and training needs of professional social workers in integrated behavioral health in primary care. Social Work in Health Care, 52(8), 752–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.791362

- Hudson, A. (2014). Social workers and Gps will be at the heat of bringing integration to life. The Guardian, 24.11.2014. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/social-care-network/2014/nov/24/health-and-social-care-integration

- Hwang, S. W. (2001). Homelessness and health. Canadian Medical Association Journal (Cmaj), 164(2), 229–233.

- Koziol McLain, J., Giddings, L., Rameka, M., & Fyfe, E. (2008). Intimate partner violence screening and brief intervention: Experiences of women in two New Zealand health care settings. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 53(6), 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.06.002

- Lahey, R., Ewald, B., Vail, M., & Golden, R. (2019). Identifying and managing depression through collaborative care: Expanding social work’s impact. Social Work in Health Care, 58(1), 93–107. 556977. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2018.1556977

- Lombardi, B., de Saxe Zerden, L., & Richman, E. (2019). Where are social workers co-located with primary care physicians? Social Work in Health Care, 58(9), 885–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2019.1659907

- Mann, C. C., Golden, J. H., Cronk, N. J., Gale, J. K., Hogan, T., & Washington, K. T. (2016). Social workers as behavioral health consultants in the primary care clinic. Health & Social Work, 41(3), 196–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw027

- McGregor, J., Mercer, S., & Harris, F. (2018). Health benefits of primary care social work for adults with complex health and social needs: A systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12337

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Ní Raghallaigh, M., Allen, M., Cunniffe, R., & Quin, S. (2013). Experiences of social workers in primary care in Ireland. Social Work in Health Care, 52(10), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.834030

- Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., David Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. (2021). BMJ, 372(71), n71. n. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- PRISMA. (2020). PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. January 10, 2022. Retrieved from http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/flowdiagram.aspx

- Rabovsky, A. J., Rothberg, M. B., Rose, S. L., Brateanu, A., Kou, L., & Misra-Hebert, A. D. (2017). Content and outcomes of social work consultation for patients with diabetes in primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160177

- [RACGP] Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2019). General practice health of the nation 2019 report. Retrieved from https://www.racgp.org.au/getmedia/bacc0983-cc7d-4810-b34a-25e12043a53e/Health-of-the-Nation-2019-report.pdf.aspx

- Reckrey, J. M., Gettenberg, G., Ross, H., Kopke, V., Soriano, T., & Ornstein, K. (2014). The critical role of social workers in home-based primary care. Social Work in Health Care, 53(4), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2014.884041

- Reckrey, J. M., Soriano, T. A., Hernandez, C. R., DeCherrie, L. V., Chavez, S., Zhang, M., & Ornstein, K. (2015). The team approach to home-based primary care: Restructuring care to meet individual, program, and system needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(2), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13196

- Rehner, T., Brazeal, M., & Doty, S. T. Research full report: Embedding a social work–led behavioral health program in a primary care system: A 2012-2018 case study. (2017). Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 23(6), S40–46. S40. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000657

- Rowe, J. M., Rizzo, V. M., Vail, M. R., Kang, S. Y., & Golden, R. (2017). The role of social workers in addressing nonmedical needs in primary health care. Social Work in Health Care, 56(6), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2017.1318799

- Rural Health Information Hub. (2020). Co-location of Services Model. Retrieved from https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/services-integration/2/co-location

- Ruth, B. J., & Marshall, J. W. (2017). A history of social work in public health. American Journal of Public Health, 107(S3), S236–242. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304005

- Saavedra, N. I., Berenzon, S., & Galván, J. (2019). The role of social workers in mental health care: A study of primary care centers in Mexico. Qualitative Social Work, 18(6), 1017–1033. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325018791689

- Safren, S. A., O’Cleirigh, C. M., Skeer, M., Elsesser, S. A., & Mayer, K. H. (2013). Project enhance: A randomized controlled trial of an individualized HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men conducted in a primary care setting. Health Psychology, 32(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028581

- Samuel, S., & Thompson, H. (2018). Critical reflection: A general practice support group experience. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 24(3), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17092

- Scott, A. (2017). ANZ – Melbourne institute health sector report: General practice trends. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, the University of Melbourne. Retrieved from https://mabel.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2334551/ANZ-MI-Health-Sector-Report.pdf

- Shah, A., Wharton, T., & Scogin, F. (2017). Adapting an interprofessional training model for social work field placements: An answer for better mental health care outreach for older adults in primary care. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(5), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2017.1381215

- Tadic, V., Ashcroft, R., Brown, J. B., & Dahrouge, S. (2020). The role of social workers in interprofessional primary healthcare teams. Healthcare Policy, 16(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2020.26292

- Wang, Z., Taylor, K., Allman-Farinelli, M., Armstrong, B., Askie, L., Ghersi, D., Bero, L. A. (2019). A systematic review: Tools for assessing methodological quality of human observational studies. Retrieved from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/assessing-risk-bias/tools-assess-risk-bias