ABSTRACT

The article investigates the impact of COVID-19 on micro-business enterprises (MBEs), establishing the coping strategies used to mitigate the impact and build resilience. A practical framework for building resilience is recommended for use by the enterprises as part of contributing to the entrepreneurial revolution agenda. An online survey using Survey Monkey was used to collect data from MBEs from a national sample in Zimbabwe. Key findings from the study include overwhelming evidence of the negative financial impact of COVID-19 on the MBEs and its impact on supply chain disruption and customer service. Practical recommendations include the need for MBEs to utilize creative resourcefulness by identifying tangible and nontangible resources in their ecosystem and utilizing their learning curve experience in dealing with precious disruptions to develop coping strategies for new challenges. MBEs should invest in the well-being of their employees and communities to foster collaboration for resilience building.

Introduction and central thesis

COVID-19 created a disruptive and uncertain economic environment for micro-business enterprises (MBEs) across the globe (Gregurec et al., Citation2021; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD], Citation2020; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021). The prolonged lockdowns disrupted supply chains, and in some cases, labor shortages for those who could still operate caused temporary or permanent closures of small and medium-sized enterprises (Dai et al., Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2021). However, the situation for MBEs in Zimbabwe is unique in the sense that MBEs were already dealing with the challenges of operating in an uncertain and disruptive environment and COVID-19 was an extra dimension to their existing challenges (Hawkins, Citation2018; Murisa & Chikweche, Citation2016; Murisa et al., Citation2018; Scoones, Citation2018). This article aims to investigate how MBEs responded to the impact of COVID-19 to develop sustainable future resilience.

Significance of the research

Although studies on the general impact of COVID-19 on society have been growing, there are limited empirical studies on the impact on MBEs (Gianiodis et al., Citation2022). A key research gap is on studying the impact on MBEs in Africa, yet these enterprises are major employers and economic actors. Our study supports calls for research expansion by Gianiodis et al. (Citation2022) to address “unanswered questions related to small business resilience that predict and explain their high failure rate, notwithstanding significant external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic” (p.2). This is a gap covered by our study, which provides insights on the impact of COVID-19 on MBEs and recommends a practical framework for developing resilience to mitigate future disruptions. In some ways, developing resilient models can be part of the entrepreneurial revolution and should include other key elements, such as ensuring the model is responsive to issues such as minimizing income inequality and social inclusion and equality.

Literature review

The World Bank defines a micro-business as a sole trader or one employing up to nine employees (World Bank, Citation2020). COVID-19 disruptions challenged MBEs to develop innovative coping strategies to ensure survival and reinforce their resilience (Gianiodis et al., Citation2022; Gregurec et al., Citation2021). MBEs have experienced more severe challenges dealing with COVID-19-related disruptions, such as supply chain issues, labor shortages, and shutdowns (Dai et al., Citation2021; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2020). Studies on resilience are transdisciplinary and there is no agreed-on definition of the concept, especially in the context of its application to how MBEs respond to disruptions (Herbane, Citation2019; Nisula & Olander, Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2021). Gianiodis et al.’s (Citation2022) special edition on “Lessons on Small Business Resilience” in the Journal for Small Business Management examines aspects of small business resilience, highlighting some conceptual lessons from COVID-19 and the 2008 global financial crisis. Hartmann et al. (Citation2022) explored antecedents and outcomes of psychological resilience in an entrepreneurial context based on a systematic review of 86 papers. Dana et al. (Citation2020) and Iborra et al. (Citation2022) used insights from a Spanish study during the 2008 global financial crisis to propose a model that focused on a specific capability and consistency in ambidexterity used by MBEs to cope with external shocks. Britto et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated the effect of leveraging family social capital to develop dynamic resilience to COVID-19 among micro-enterprises in Brazil. Smith et al. (Citation2022) reinforced the importance of reinforcing resilience as part of a mindset shift that is shaped by an external-oriented identity. Others, like Durst and Henschel (Citation2021), have developed frameworks such as the quickly adapt and mobilize to assist Estonian MBEs to cope with COVID-19 through quick adaptation and mobilization. Although research on the resilience of MBEs has increased, the area is still underinvestigated, especially in the context of regions such as Africa, with clear recommendations for a practical, context-relevant resilience framework that can be used for coping with future disruptions.

Research questions and methodology

The research seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What has been the impact of COVID-19 on MBEs in Zimbabwe?

RQ2: What coping mechanisms have MBEs used to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and build resilience?

Consistent with the research questions, a quantitative approach using an online survey using Survey Monkey was used to collect data from MBEs with 0 to 19 employees (Sharma, Citation2017) from micro-businesses from various sectors. Descriptive statistics were conducted using the quantitative responses, while the qualitative responses were thematically analyzed using content analysis.

Findings

Findings from the study are divided into the impact of the pandemic on critical areas that determine the survival or demise of the MBEs and responses used by MBEs to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. A practical framework for resilience building is then proposed.

The impact

Financial impact of lockdown on enterprises

The negative financial impact recorded by the MBEs confirmed trends that were taking place across the globe and is outlined in .

Ninety-five percent of the respondents cited a negative financial impact of lockdown, which confirms other global trends reported in the OECD (Citation2020) report on the impact of lockdown on small enterprises (Deloitte, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2020; Ruiz et al., Citation2020). An important finding was the recognition that 5 percent of respondents experienced a positive impact on their finances because they had an increase in the demand for their products or, through their innovative coping mechanisms, they were able to tap into new emerging opportunities in areas such as the provision of personal protective equipment. The loss of revenue largely affected the business’ ability to restock on raw materials and the enterprises’ ability to pay employee salaries. An interesting finding was the relatively small percentage (8.5 percent) who indicated that they would have to close their businesses altogether because the financial losses were too severe. Compared to other markets, such as Nigeria and Senegal, this was a low number (Koloma, Citation2020).

Impact of lockdown on supply chains

Supply chain disruption has been the most common area of disruption that has impacted MBEs at a global level (Chiloane-Phetla & Mathipa, Citation2021; Fonseca & Azevedo, Citation2020; McKinsey & Company, Citation2020). outlines the changes to supply chain that were induced by the pandemic on the Zimbabwean MBEs.

The supply chains of over 57 percent of respondents were negatively affected by complete closures of suppliers. Some suppliers remained open (15.15 percent) and 27 percent were operational on a delivery basis. However, the increased costs of delivery were being passed on to the MBEs. This cost would mostly likely be passed down to consumers resulting in a corresponding increase in the cost of goods and services. For the Zimbabwean MBEs, managing supply chains was already a big aspect of their day-to-day challenges given their high dependence on imports for most of their supplies, which was compounded by the related challenges of accessing foreign currency for the imports. Thus, the pandemic simply extended and compounded an already existing challenge whose impact was somewhat mitigated by the existing strategies they were already using, such as import substitution and cross-border barter trade using informal traders. These are strategies that might not have been prominent features for other MBEs across the globe before the pandemic.

Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on customer interactions

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on businesses was also manifested in its impact on general livelihoods of consumers who are the customers for the businesses (International Monetary Fund, Citation2020; Irwin, Citation2020; Koloma, Citation2020). Thus, any constraint that was exerted on MBEs was bound to have an impact on their customer base and the subsequent interactions they had with them. Fifty-six percent of the respondents indicated that they had lost customers to competitors, which indicates some failure to deliver within agreed-on timelines on their part because of lockdown restrictions. Additionally, 25 percent indicated their customers expressed frustration at the impeded service or product delivery. Interestingly, 18 percent of MBEs that had developed coping systems and invested in more customer-centric strategies experienced no change at all and a further 18 percent said they simply shifted to receiving all their orders online to avoid causing customer frustration.

The response

Diversification of business during the COVID-19 lockdown

Diversification of business activities has been commonly cited as one of the significant ways MBEs responded to the pandemic (Deloitte, Citation2020; McKinsey & Company, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2020). However, for MBEs in Zimbabwe, this was not necessarily the immediate go-to strategy. The majority (71.4 percent) of businesses did not diversify their current product/service offerings and remained the same. The cost of diversification was not a cost that most of these MBEs could easily absorb, considering the financial impact they were already experiencing from the pandemic. This finding is significantly different from experiences in other markets where diversification was the quick default mode to which MBEs resorted (Balde et al., Citation2020; Bishi et al., Citation2020; Chiloane-Phetla & Mathipa, Citation2021; Danquah et al., Citation2020; Fonseca & Azevedo, Citation2020).

Innovations arising from the COVID-19 pandemic

A significant focus of these innovations was structured around expanding e-commerce capabilities to enhance the online accessibility of products and services. Again, this was also made possible or accelerated by the MBEs’ already existing integration of e-commerce capabilities in response to weak formal retailing or distribution systems.

Strategic survival action plans

Besides establishing strategies used to diversify businesses, the article investigates the broad strategic efforts undertaken by the MBEs to build resilience and enhance survival to recover from the negative impact of the lockdown.

Toward an integrative practical framework for building resilience for MBEs

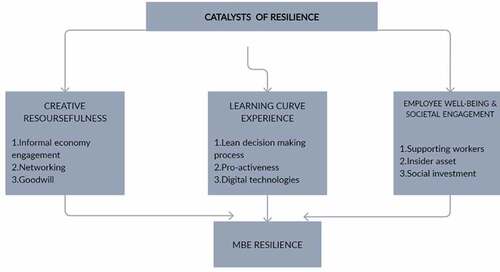

A resilience-building framework is proposed in , drawing on insights from the MBEs’ response to the pandemic and prior experience.

The fundamental premise for the framework is the need to understand the potential catalysts for resilience that utilize both internal and external capabilities that are framed by the context in which the MBEs operate. The framework’s components are relevant to the bigger question of enhancing entrepreneurial revolution using the MBEs’ footprint.

Creative resourcefulness

Extant literature recognizes the established resource constraints with which MBEs must contend in their operations, which impact their ability and capacity to build resilience to mitigate the impact of disruptions (Smith et al., Citation2022; Taneja et al., Citation2016). A response to addressing these challenges in economies that are functional, stable, and have predictable systems involves investing in minimizing the established challenges, such as lack of resource shortages and capacity limitation. The different context that MBEs operating in markets that are highly informalized (such as in Zimbabwe and most African countries) and have different nuances and complexities requires a different mindset to harnessing resources. Creative resourcefulness entails MBEs identifying both tangible and nontangible resources in their ecosystem, which can be useful in developing resilience to disruptions. This is also key in developing a proactive mindset when dealing with new challenges. For example, strategies on import substitution, sourcing of raw materials, and final products using the various informal structures and systems such as cross-border alliances can be useful. Some of the strategies used by MBEs in this study were dependent on networking and drawing on the goodwill these MBEs had developed operating in a difficult environment and became handy when there was a pandemic outbreak.

Learning curve experience

MBEs relied on their learning curve experience in dealing with disruptions when faced with a new challenge of COVID-19 (Lee et al., Citation2020). Drawing on experience from dealing with the variety of challenges that emanate from their operating environment can provide a basis for developing strategies for building resilience to disruptions. Current lessons and experiences from dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic that have been outlined in this study can be useful as a starting point for developing a proactive mindset for dealing with potential future disruptions (Smith et al., Citation2022). Identifying points for leveraging digital technologies even in a resource-constrained environment can provide a foundation for developing resilience against future disruptions. In Zimbabwe’s case, MBEs have effectively used their existing use of mobile-related technologies as coping strategies to manage a disruption such as the pandemic. Again, high mobile telephony penetration levels are a common feature in Africa, where these have become alternative platforms for facilitating transactions through mobile money payments (African Development Bank, Citation2020; Asongu et al., Citation2018). These are platforms that can be used in a flexible way to build resilience for dealing with any future potential disruptions. While networking has been identified as an intangible resource, it is important to reinforce its importance in facilitating resilience for MBEs from the perspective of curating and drawing the learning curve experience accrued from working with different networks in dealing with the various challenges both before and during the COVID-19 era. Part of the reason why the MBEs in this study were able to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic was due to the lean and mostly owner-managed structures of their operations, which allowed flexible, agile, and adaptable decision making, which is often difficult in bigger organizations (Iborra et al., Citation2022). Leveraging this competitive advantage is important in building resilience against disruptions.

Employee well-being and societal engagement

The MBEs’ response was not just limited to issues that related to revenue and business operations protection but placed a premium on making a positive contribution to minimizing the spread of COVID-19 at both the workplace and in the community. The MBEs invested in the well-being of their employees were applicable by activating flexible working arrangements and checking on the mental well-being of the workers, considering the stress levels they were going through dealing with pandemic-related issues. This is important because MBEs are traditionally not synonymous with this level of engagement. Investment in their human capital ensured continuity of operations, improved teamwork, and trust, which are key antecedents for bouncing back from disruptions. Moreover, employees had the insider knowledge of the communities in which MBEs operate in and are in fact part of the broad ecosystem of these communities and this was important in promoting adherence to measures for minimizing spread of the virus. Social investment in the communities was not just material but included simple acts, such as facilitating communication of important messages by the MBEs considering their connection with the communities.

Practical implications

The critical practical recommendation that emerges from this study is to develop an integrative framework for building resilience to manage future disruptions. The framework has identified three core catalysts that can form the foundation for building MBEs. The investment in employees’ and communities’ well-being has the potential of being part of the entrepreneurial revolution due to their contribution to social inclusion and income equality. The human-centered empathetic approach of the MBEs’ interventions creates a foundation for prospects for more collaboration between the MBEs and other stakeholders to potentially cover other issues like the MBEs’ sustainability action plans and carbon footprint.

Social implications

The MBEs undertake various initiatives to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in the workplace. This community engagement reinforces the importance of businesses collaborating with their communities on shared-interest issues, such as the case to minimize the spread of the virus.

Limitations and future research direction

The study’s focus on Zimbabwe limits generalizability, notwithstanding the fact that the context in Zimbabwe is present in other African countries to varying levels. An expansion to other markets in Africa might have varying degrees of levels of contextual challenges to establish if the phenomenon observed in this study will be replicated in these markets. Multicross-country comparative studies could also be carried out to establish whether the integrative resilience framework retains the same characterization in different markets.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- African Development Bank. (2020). African economic outlook 2020-supplement: Amid COVID-19.

- Asongu, S., J. Nwachukwu, & S. M. Orim. (2018). Mobile phones, institutional quality and entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 131(June), 83–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.08.007

- Baldé, R., M. Boly, & E. Avenyo. (2020). Labour market effects of COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: An informality lens from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Senegal (UNU-MERIT Working Paper Series No. 2020-022). UNU-MERIT.

- Bishi, H., S. Grossman, & M. Startz. (2020, June). How COVID-19 has affected Lagos traders: Findings from high frequency phone surveys. Policy brief, NGA-20075. IGC and Lagos Trader Project.

- Britto, R. P. D., A.-K. Lenz, & M. G. M. Pacheco. (2022). Resilience building among small businesses in low-income neighborhoods. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2041197

- Chiloane-Phetla, G., & R. E. Mathipa. (2021). An exploration of challenges faced by small-medium enterprises caused by COVID-19: The case of South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 27(1), 1–13.

- Dai, R., H. Feng, J. Hu, Q. Jin, H. Li, R. Wang, R. Wang, L. Xu, & X. Zhang. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from two-wave phone surveys in China. China Economic Review, 67(June), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101607

- Dana, L. P., C. Gurau, I. Light, & N. Muhammad. (2020). Family, community, and ethnic capital as entrepreneurial resources: Toward an integrated model. Journal of Small Business Management, 58(5), 1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12507

- Danquah, M., S. Schott, & K. Sen. (2020, August). COVID-19 and employment: Insights from the Sub-Saharan African experience, Wider Background Note | 7/2020.

- Deloitte. (2020). Addressing the financial impact of Covid-19 navigating volatility & distress. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-covid-19-navigating-volatility-distress.pdf

- Durst, S., & T. Henschel. (2021). COVID-19 as an accelerator for developing strong(er) businesses? Insights from Estonian small firms. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 2(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/26437015.2020.1859935

- Fonseca, L. M., & A. L. Azevedo. (2020). COVID-19: Outcomes for global supply chains. Management & Marketing (Bucharest, Romania), 15(1), 424–438.

- Gianiodis, P., S. H. Lee, H. Zhao, M. D. Foo, & D. Audretsch. (2022). Lessons on small business resilience. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2084099

- Gregurec, I., M. Tomičić Furjan, & K. Tomičić-Pupek. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on sustainable business models in SMEs. Sustainability, 13(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031098

- Hartmann, S., J. Backmann, A. Newman, K. M. Brykman, & R. J. Pidduck. (2022). Psychological resilience of entrepreneurs: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2024216

- Hawkins, T. (2018). Zimbabwe business outlook, 2018-19. Presentation to the British Council.

- Herbane, B. (2019). Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(5–6), 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1541594

- Iborra, M., V. Safón, & C. Dolz. (2022). Does ambidexterity consistency benefit small and medium-sized enterprises’ resilience? Journal of Small Business Management, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2014508

- International Monetary Fund. (2020). The IMF and Covid-19. Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19

- Irwin, N. (2020). It’s the end of the world economy as we know it. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/16/upshot/world-economy-restructuring-coronavirus.html

- Koloma, Y. (2020). COVID‐19, financing and sales decline of informal sector SBEs in Senegal. African Development Review, 33(S1). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12532

- Lee, J. Y., A. Jimenez, & T. M. Devinney. (2020). Learning in SME internationalization: A new perspective on learning from success versus failure. Management International Review, 60(4), 485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-020-00422-x

- McKinsey & Company. (2020). Jump-starting resilient and re-imagined operations. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/jump-starting-resilient-and-reimagined-operations

- Murisa, T., & T. Chikweche. (2016). Beyond the crises: Zimbabwe’s prospects for transformation. Weaver Press.

- Murisa, T., F. Nkomo, & M. Zihanzi. (2018, November). Crisis again: Is there light at the end of the tunnel for Zimbabwe? SIVIO Institute Policy Brief Number 1.

- Nisula, A. M., & H. Olander. (2020). The role of motivations and self-concepts in university graduate entrepreneurs’ creativity and resilience. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1760030

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME policy responses. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/coronavirus-covid-19-sme-policy-responses-04440101/

- Rodrigues, M., M. Franco, N. Sousa, & R. Silva. (2021). COVID 19 and the business management crisis: An empirical study in SMEs. Sustainability, 13(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115912

- Ruiz, E. M. A., E. Koutronas, & M. Lee. (2020). Stagpression: The economic and financial impact of Covid-19 pandemic. Available at SSRN 3578436.

- Scoones, I. (2018). Zimbabwe’s latest crisis—it’s the economy stupid. Wordpress. https://zimbabweland.wordpress.com/2018/10/15/zimbabwes-latest-crisis-its-the-economy-and-politics-stupid/

- Sharma, A. (2017). Quantitative methodology: Selecting an appropriate model for multiple outcomes/multinomial logit. Sage.

- Sharma, P., T. Y. Leung, R. P. J. Kingshott, N. S. Davcik, & S. Cardinali. (2020). Managing uncertainty during a global pandemic: An international business perspective. Journal of Business Research, 116(August), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.026

- Smith, J. B., C. G. Smith, J. Kietzmann, & S. T. Lord Ferguson. (2022). Understanding microlevel resilience enactment of everyday entrepreneurs under threat. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2017443

- Sun, T., W.-W. Zhang, M. S. Dinca, & M. Raza. (2021). Determining the impact of Covid-19 on the business norms and performance of SMEs in China. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 35(1), 2234–2253. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1937261

- Taneja, S. M., G. Pryor, & M. Hayek. (2016). Leaping innovation barriers to small business longevity. Journal of Business Strategy, 37(3), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-12-2014-0145

- World Bank. (2020). Global economic prospects. License Creative Commons Attribution CCBY 3.01GO. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-15539