ABSTRACT

This study investigates entrepreneurial motivations of Japanese academic entrepreneurs. Motivations of starting new business are one of the key factors of achieving success in start-ups, and understanding academic entrepreneurs’ motivations is critical to provide effective support. One hundred and forty-four Japanese academic entrepreneurs were extracted from a university start-up database, and asked to complete a questionnaire of an entrepreneurial motivation scale with 20 questions. A hierarchal cluster analysis was conducted on the subscale scores of 71 valid respondents, and four types were identified: financial rewards, research expansion, independent research, and low motivations. Because the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations varies from type to type, we insist that different support measures should be provided for different types of academic entrepreneurs.

Introduction

Although the number of university start-ups in Japan increased rapidly from 420 to 1,807 between 2000 and 2008, and increased further from 1,846 to 3,782 between 2017 and 2022 (Japanese Government Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Citation2022), not all of them have grown steadily, and it is required to provide effective support for them.

Regarding support measures for starting up venture companies by universities, there are some studies (Shane, Citation2004), but few on academic entrepreneurs who play an essential role in start-ups (Clarysse et al., Citation2011). Without their information, especially their motivations for starting a new business, it is difficult to provide effective support measures. Therefore, this study focuses on motivations of Japanese academic entrepreneurs and explores effective support measures for them.

In this study, 144 Japanese academic entrepreneurs were extracted from a university start-up database (Japanese Government Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Citation2019), and asked to complete a questionnaire with an entrepreneurial motivation scale. From the results of the questionnaire, four types of academic entrepreneurs were identified by a hierarchal cluster analysis, for each of which we propose different support measures.

Literature review

The process of creating university spin-offs and their support measures, such as the Bayh-Dole Act and Technology Transfer Office, was studied (Wood, Citation2011). Similarly in Japan, the Japanese version of the Bayh-Dole Act and a technology licensing organization was studied (Takenaka, Citation2005). However, those measures do not take characteristics of academic entrepreneurs into consideration.

Among academic entrepreneurs’ various characteristics, motivations for starting a new business are important because they are one of the key factors of achieving success in start-ups (Matsuda, Citation1997). However, the entrepreneurial motivations are underresearched and “entrepreneurial motivation was largely ignored through the 1990s and early 2000s until recently” (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011, p. 16). Because motivation significantly predicts entrepreneurial activity (Collins et al., Citation2004) and the level of entrepreneurial motivation affects business strategy (Baum et al., Citation2001), this article focuses on the entrepreneurial motivations of academic entrepreneurs.

Academic entrepreneurs have diverse motivations. They include intellectual curiosity (Lam, Citation2011, p. 1360), research funds (Lam, Citation2011, p. 1360), commercialization of products and services (Hayter, Citation2015, p. 1008; Lam, Citation2011, p. 1361), independence (Shane, Citation2004, p. 158), social contribution (Hayter, Citation2015, p. 1004), network (Lam, Citation2011, p. 1360), new experiences (Hayter, Citation2015, p. 1010; Shane, Citation2004, p. 161), and financial rewards (Hayter, Citation2015, p. 1010; Lam, Citation2011, p. 1360). Intellectual curiosity, independence, and new experiences can be classified as intrinsic motivations, research funds and financial rewards as extrinsic motivations related to money, and commercialization of products and services, social contribution, and network as social motivations.

Lam (Citation2011) classified British scientists involved in commercial activities into four types, with three motivation scales of ribbon (reputational/career rewards), puzzle (intrinsic satisfaction), and gold (financial rewards), and insisted on the importance of customized policy design for each type. Likewise, we try to classify Japanese academic entrepreneurs by motivation and propose effective support measures for each type.

Methodology

Survey subjects

The Japanese government issued a university start-ups database (Japanese Government Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Citation2019) with a list of 476 companies. Among them, we selected 331 research outcome–based venture companies because they were related to universities deeply, and university professors working there were proactively involved with day-to-day decision making. Next, we excluded ones with unclear or closed business conditions by checking their websites. Furthermore, we excluded ones at which executives included no university faculty or ex-faculty members based on the university start-ups database and websites of corresponding universities and companies. Finally, 144 remained, and their 144 academic entrepreneurs were selected as survey subjects. Note that an academic entrepreneur is defined as a university faculty or an ex-faculty member who is also an executive of a venture company.

Survey method

Subjects were asked to complete an online questionnaire by e-mail or mail between October and December 2020. The questionnaire was an entrepreneurial motivation scale with 20 questions (see ) derived from the studies (Amabile et al., Citation1994; Nishikawa & Amemiya, Citation2015; Yamaguchi, Citation2019) or created by the authors. It consisted of eight subscales: intellectual curiosity, research funds, commercialization of products and services, independence, social contribution, network, new experiences, and financial rewards, each of which had two or three questions (five-point Likert scale).

For ethical considerations, participants were informed of the purpose of the study and that the survey responses would be anonymized for the analysis in advance. Only participants who agreed to the above condition participated in the survey. A review by the ethics committee at the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, the institution to which we belonged at that time, was exempted due to the judgment of one of the committee members.

Results

Response

Of responses, 82 of 144 were received, with a 57 percent response rate, and 71 of 144 responses were valid, with a 49 percent valid response rate.

Entrepreneurial motivation

Three subscales (intellectual curiosity, commercialization of products and services, and new experiences) were excluded from the further analysis because they had low Cronbach’s alpha values (.557, .387, and .365, respectively). Social contributions was also excluded because all of its questions showed ceiling effects. A factor analysis with maximum-likelihood method was conducted on the remaining subscales, and four factors (subscales) were identified, as expected (financial rewards, network, research funds, and independence; ). Note that question MI3 was excluded because of low factor loading (.432). All four factors had enough Cronbach’s alpha values (.848, .787, .940, and .703, respectively). For descriptive statistics and correlations, see .

Table 1. Factor analysis of entrepreneurial motivations.

Table 2. Entrepreneurial motivations descriptive statistics of factors.

Table 3. Entrepreneurial motivations correlation of factors.

Classification of academic entrepreneurs by motivation

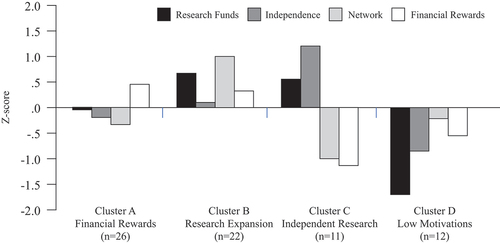

A hierarchal cluster analysis with Ward’s method and Euclidean squared distance was conducted on the subscale scores of 71 respondents, and four clusters were identified ().

Cluster A was named the financial rewards type because its financial rewards score was the highest among four scores. Cluster B was named the research expansion type because its research funds and network scores were higher than the others. Cluster C was named independent research type since its research funds and independence scores were higher. Cluster D was named the low motivations type since all of its scores were low.

Discussion

Although various support measures, such as intellectual property management, patent applications, and technology transfers, are provided for academic entrepreneurs by universities and technology licensing organizations in Japan, they might not be sufficient because they are not optimized with entrepreneurial motivations.

Our findings imply that different academic entrepreneur types should have different support measures. For the financial rewards type, it is important to provide direct involvement with entrepreneurial activities or management support for business expansion rather than supporting their research activities because their motivations are extrinsic.

On the other hand, the research expansion and the independent research types have intrinsic motivations, and it is speculated that support measures such as securing research funds and providing human resources for managing their businesses are effective.

The low motivations type may have entrepreneurial motivations different from the four we introduced, or work on entrepreneurial activities without strong motivations. In the latter case, they might enhance their motivations with entrepreneurial education or reconsider their venture activities.

Our findings also imply that the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations varies with the type of Japanese academic entrepreneurs, and correspondingly the required support measures vary by type. This is aligned with Lam (Citation2011), who also addressed the necessity of designing different policies by types of British scientists.

The limitation of this study is that companies not registered in the university start-ups database were not included in the research. A survey with a wider range of sample is required for further analysis. In addition, entrepreneurial motivations should be revised to cover motivations not identified through the literature review and ones excluded in the process of factor analysis.

Conclusions

With the finding that Japanese academic entrepreneurs can be classified into four types by motivations, we insist that support measures for them should take their motivations into consideration. For the financial rewards type, direct involvement with entrepreneurial activities or management support for business expansion could be effective for enhancing their extrinsic motivations. For the pursuing research type, accelerating research activities and providing human resources for taking care of their entrepreneurial activities could be effective for inspiring intrinsic motivations in them. For the low motivations type, it is necessary to further investigate if they have other motivations, or if they are not positive for entrepreneurial activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., & Tighe, E. M. (1994). The work preference inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(50), 950–967.

- Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292–303. https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/3069456

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x

- Clarysse, B., Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capacity, experience and organizational support on academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1084–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.010

- Collins, C. J., Hanges, P. J., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1701_5

- Hayter, C. S. (2015). Public or private entrepreneurship? Revisiting motivations and definitions of success among academic entrepreneurs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(6), 1003–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9426-7

- Japanese Government Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2019). Daigakuhatsu bencha detabesu [University start-ups database]. https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/innovation_corp/univ-startupsdb.html

- Japanese Government Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2022). Reiwa 4 nendo sangyo gijutsu chosa [2022 fiscal year industry and technology research (University start-ups actual state, etc) results summary]. https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/innovation_corp/start-ups/reiwa4_vb_cyousakekka_gaiyou.pdf

- Lam, A. (2011). What motivates academic scientists to engage in research commercialization: ‘gold,’ ‘ribbon’ or ‘puzzle’? Research Policy, 40(10), 1354–1368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.002

- Matsuda, S. (1997). Kigyoron: Antorepurena no shishitsu, chishiki, senryaku [Venture theory: Qualities, knowledge and strategy of entrepreneurs]. Nihon Keizai Shinbun Publishing.

- Nishikawa, K., & Amemiya, T. (2015). Chiteki kokishin shakudo no sakusei: Kakusanteki kokishin to tokushuteki kokishin [Development of an epistemic curiosity scale: Diverse curiosity and specific curiosity]. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 63(4), 412–425.

- Shane, S. A. (2004). Academic entrepreneurship: University spinoffs and wealth creation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Takenaka, T. (2005). Technology licensing and university research in Japan. International journal of intellectual property-law. Economy and Management, 1(1), 27–36.

- Wood, M. S. (2011). A process model of academic entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 54(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2010.11.004

- Yamaguchi, F. (2019). Kinrosha no shigoto ni taisuru shimeikan no sokutei: Zenshinteki shimeikan shakudo no kaihatsu [Developing the expanded sense of mission scale to assess the workers’ sense of responsibility regarding their jobs]. Journal of Health Psychology Research, 31(2), 195–202.

Appendix

Table A1. Entrepreneurial motivation subscales.