ABSTRACT

Une fenêtre ouverte/An Open Window (2005), a documentary by the Senegalese writer and filmmaker Khady Sylla, offers an intimate, unsettling portrait of the mental health difficulties suffered by both Sylla and her friend, Aminta Ngom. This article reads Sylla’s film as embracing Black female disabled subjectivities that have been historically constructed – through intersecting patriarchal, colonialist and ableist regimes – as abject or aberrant. While scholarship on Sylla’s film has addressed ideas of female madness, it has not engaged with (Black feminist) disability studies – a critical lacuna addressed here. Drawing on ideas of opacity (Glissant), ‘mad methodology’ (Bruce) and Black feminist disabled perspectives that question emancipatory or healing coherence (Pickens, Nack Ngue), the article reads Sylla’s film in terms of a poetics of opacity that opens to a cripping of cinematic time and space. While focusing on a relationship of female friendship, solidarity and care that offers refuge from fraught familial dynamics, the film’s empathy is capacious, extending to Aminta’s mother and daughter too. As Une fenêtre ouverte traces the tensions that structure these various relationships, it reveals its feminist approach, its mode of feeling in solidarity, to be one that embraces strategies of opacity and ethical ambiguities.

Une fenêtre ouverte/An Open Window (2005), a documentary by the Senegalese writer and filmmaker Khady Sylla, offers an intimate, unsettling portrait of the mental health difficulties suffered by both Sylla and her friend, Aminta Ngom. While it evinces a feminist attentiveness to female subjectivity and marginalisation that runs through Sylla’s filmmaking, Une fenêtre ouverte is her most intensely personal and autobiographical film. Shot in Wolof and French, the film attends closely to the dynamics between Sylla and Aminta as each struggles, in different ways, with cognitive disability, or what Sylla describes in her voiceover as ‘madness’ [la folie].Footnote1 Through a mode of ‘domestic ethnography’ that is by turns, as Bronwen Pugsley describes, ‘poetic, interactive, performative and reflexive’ (Pugsley Citation2012, 206–207), the film includes various scenes in which Sylla describes her mental anguish directly to the camera, Aminta speaks of her own suffering, and the two women sit together, talking (see ).Footnote2 The film also includes uncomfortable, extended conversations with Aminta’s mother and teenage daughter. While documentary film has periodically turned to explore cognitive disability, from Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies (1967) to Nicolas Philibert’s Sur l’Adamant/On the Adamant (2023), Sylla’s documentary is distinctive in offering a Black feminist portrait of cognitive disability in a contemporary Senegalese context. In its engagement with neurodiversity, the film adopts strategies of opacity that preserve unfathomability, while devoting particular attention to a relationship of female friendship, solidarity and care that offers refuge from the fraught dynamics of family relationships.Footnote3

Une fenêtre ouverte never discloses details of a diagnosis for either Sylla or Aminta. While unsettling the ‘epistephilia’ that often shapes documentary cinema (Nichols Citation1991, 31), this refusal to categorise has particular resonance within the field of disability studies. If ‘crip theory problematises diagnosis as the sole parameter for defining disability’ (Schalk Citation2018, 17), then Sylla’s film finds allegiance with such crip theoretical moves through its refusal of clinical categorisation.Footnote4 Indeed, Sylla’s embrace of the more general term ‘madness’ resonates with a reclaiming of this term within mad studies (a field that has emerged from anti-psychiatry and critical disability studies). While Pugsley does not trace these theoretical connections, she suggests: ‘The focus of this film clearly lies beyond the purely clinical and social aspects of mental illness as Sylla prioritises subjectivity’; Une fenêtre ouverte ‘delves into the personal, addressing madness from within’ (Pugsley Citation2012, 205). Pugsley contends that this focus on madness ‘penetrates the very structure of the film and the composition of the image’ (Citation2012, 210). She cites, for example, Sylla’s ‘unsettling interactions with the subjects of her film’, the lack of ‘stylistic seamlessness’, and ‘frequent sudden camera movements as well as highly unsteady and slanted shots’. For Pugsley, ‘This unstable footage is arguably a material translation of Sylla’s inner experience of mental illness’; ‘the film both describes and performs madness’ (Citation2012, 209–210).

While Pugsley’s reading is richly generative, my approach moves away from what might be seen as an overly neat analogical model of the film performing madness, in order to explore what I refer to as Sylla’s ‘poetics of opacity’.Footnote5 The film’s refusal to disclose a diagnosis for either Sylla or Aminta resonates not only with crip theory’s problematisation of diagnostic categories but also with Édouard Glissant’s reflections on the ‘right to opacity’ – a refusal of the demands for transparency and legibility historically made by imperialist, Enlightenment thinking (Glissant Citation1997, 189). Glissant suggests: ‘The transparency of the Enlightenment is finally misleading. We must reclaim the right to opacity. It is not necessary to understand someone – in the [French] verb to understand, there is the verb to take – in order to wish to live with them’ (Glissant Citation1993, 122).Footnote6 Drawing on Glissant’s reflections in the context of their study of Black madness and creativity, La Marr Jurelle Bruce writes of a ‘mad methodology’ that seeks to ‘thwart positivist knowing’ (Citation2021, 10). Bruce suggests: ‘I want to live with the madpersons gathered in this study, but I do not need or want to take them. I strive to pursue madness, but not to capture it’ (Citation2021, 11; original emphasis). Une fenêtre ouverte similarly enacts a refusal of transparency, of taking and capture, in favour of opacity, as a response to the unfathomability of the self and of others, particularly in experiences of madness. As I suggest in my reading, strategies of opacity shape Sylla’s interactions with Aminta and others, as well as the form of the film more broadly. If the film’s title seems to invoke a common conception of documentary as offering a ‘window’ onto the world, the film itself troubles ideas of access or transparency.Footnote7 Like Glissant, Sylla affirms ‘the right to opacity’, recognising that ‘[t]o feel in solidarity’ (Glissant Citation1997, 193) does not mean to assimilate or grasp.

While feeling in solidarity, and open and generous towards its subjects, Une fenêtre ouverte is also narrowly focused, seeming almost hermetic in its approach. It spends much of the time in the courtyard where Aminta’s family now, troublingly, keep her confined, and only Aminta, her mother, and her daughter Tiané are interviewed for the film. Overall, the impression, as Pugsley notes, is one of ‘intimacy and disconnection from the outside world’ (Citation2012, 205). The film’s documenting of Aminta’s confinement implicitly raises questions about ableist conceptions – by her family and by social structures more broadly – of Aminta as abject, as carceral life (‘I’m locked in, and they’re waiting for me to die’, Aminta says to Sylla at one point), and also about the lack of support for families managing mental health issues in Senegal, especially in situations of poverty.Footnote8 Sylla’s film refuses ableist modes of marginalisation, invisibilisation and abjection – not only through Sylla’s practical interventions (as she persuades Aminta’s mother to allow her out for walks) but through a careful, sustained attentiveness to the perspectives of both Aminta and Sylla. But, in contrast to Sylla’s Le monologue de la muette/The Silent Monologue (2008), a documentary about domestic slavery in Senegal, in which the testimony of one woman, Amy, opens onto a broader political analysis, Une fenêtre ouverte’s cloistered approach maintains a narrow focus on the lived experience of the two women at its centre, on what Sylla’s voiceover describes as the experience of ‘unspeakable’ pain. (In this sense, Une fenêtre ouverte seems to anticipate, for example, Cameroonian director Rosine Mbakam’s intimate, sustained documentary portrait of a female friend in Les Prières de Delphine/Delphine’s Prayers [2021].)

Sylla’s tightly focused approach contrasts with Ousmane Sembène’s Xala (1975), which adopts a broader, more openly politicised, view of disability in Senegal. Julie C. Van Dam reads Xala, a fictional narrative of a wealthy businessman struggling with impotence, as a ‘satire of neocolonial greed and its production of disabilities’ (Citation2016, 209). Attending to scenes featuring disabled male beggars on the streets of Dakar, Van Dam suggests that Xala makes visible ‘dissonant and resistant postcolonial African bodies and subjectivities’ (Citation2016, 209). She views the film in the context of governmental policies under Léopold Sédar Senghor that enforced a segregation of the disabled: ‘in the name of nation-building and touristic development, they were forcibly removed from the streets and dumped in isolated villages, prisons, or sites that had served as labour camps in the colonial era’ (Van Dam Citation2016, 212).Footnote9 Van Dam reads Senegal’s approach during this period in relation to David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder’s term ‘ablenationalism’ (Mitchell and Snyder Citation2010), arguing that ‘Sembène’s film theorises disability as a powerful visual and visceral counter-narrative to dominant discourses of the postcolonial nation and its hygiaesthetic-able body politic’ (Van Dam Citation2016, 210). I suggest that Une fenêtre ouverte also offers ‘a powerful visual and visceral counter-narrative’ to such ‘ablenationalist’ discourses, yet its sustained engagement with female subjectivity (contrasting with Sembène’s focus on male subjects) is distinct. Sylla’s film might thus be seen as responding to Ella Shohat’s call for forms of ‘Post-Third Worldist’ feminist filmmaking that unsettle the predominantly masculinist constructions of ‘nation’ (Shohat Citation2006, 290–329) - masculinist constructions such as those found in Xala (even though satirised by Sembène), as well as many other works of Senegalese cinema.

Despite the apparently hermetic approach of Une fenêtre ouverte, my reading seeks to situate it in a broader landscape of critical thought about race, gender and disability. As Nirmala Erevelles, Therí Alyce Pickens, Julie Nack Ngue and others have observed, until recently, questions of coloniality and race have often been overlooked within disability studies, while, conversely, issues of disability have frequently figured as blindspots within critical race theory and postcolonial studies.Footnote10 Such gaps have been addressed in recent years.Footnote11 Research at the intersection of critical race theory and disability studies, however, has received relatively little attention within the field of film studies, despite the burgeoning field of scholarship on cinema and disability more broadly.Footnote12 Also relevant to a discussion of Sylla’s film is the relative marginalisation of cognitive disability within the field of disability studies (which has habitually focused on physical disability [Fraser Citation2018]), and an under-theorisation of gender – and feminist politics in particular – within scholarly work at the nexus of race and disability. While studies such as Nack Ngue’s Critical Conditions (Citation2012) are vital points of reference for thinking about representations of female madness and disability in Francophone Afro-feminist contexts, Nack Ngue’s focus is on literary texts.Footnote13 Sylla’s film offers a ground-breaking exploration of intersections of gender, race and disability within the realm of documentary cinema, particularly in the Senegalese context.

I read Une fenêtre ouverte as a documentary that embraces Black female disabled subjectivities that have been historically constructed – through intersecting patriarchal, colonialist and ableist regimes – as abject or aberrant. While scholarship on Sylla’s film has addressed ideas of female madness, it has not engaged with (Black feminist) disability studies – a critical lacuna that I address here, by drawing on work by Erevelles, Nack Ngue, Pickens and Bruce among others. As Nack Ngue suggests, any contextualisation of disabled female postcolonial subjectivities must necessarily take into account gendered and racialised histories of oppression, including ‘colonial-era notions of the diseased and aberrant black female body informed by racial biology’ (Citation2012, 6). In Sylla’s film, there is a reclaiming of Black female disabled subjectivities historically constructed as aberrant, deviant and abject. While foregrounding intimate reflections on pain and suffering, the film embraces mad, dissonant subjectivities through a cripping of cinematic time and space and a questioning of emancipatory or healing coherence. At the same time, the film is feminist in its attention not only to the lived experiences of Aminta and Sylla but to the impact of Aminta’s condition on her mother and daughter, and to dynamics of female friendship, solidarity and care that extend beyond the family unit. Yet as Une fenêtre ouverte traces the ambivalences and tensions that structure these relationships – from the fraught dynamics of mother–daughter relations to the asymmetries of power between filmmaker and subject – it reveals its feminist approach, its mode of feeling in solidarity, to be one that embraces strategies of opacity and ethical ambiguities.

From mirror to archive

Une fenêtre ouverte opens with the sound and image of the Atlantic ocean, shot from Dakar, accompanied by the voice of Sylla:

You look at yourself in a broken mirror. You see your fragmented face. Your face is shattered. And the one looking at you in the broken mirror sees the fragmented pieces of your face. Which of you will reconstruct the puzzle?Footnote14

The scene cuts to a close-up of Sylla, blinking slowly, saying: ‘Are you even on the same side of the mirror?’Footnote15 The opening scene initiates a set of reflections on fragmentary identities, on looking and mirroring, and on difficulty and opacity that will run through the film. It has a shape-shifting quality, as alternative meanings open up: while the second-person address seems ostensibly directed at Aminta or Sylla herself, it might also be read as interpellating the viewer. Watching this film, might we not also see our own fractured reflections? Could this not be read in terms of what Bruce describes, in another context, as a hailing of the audience ‘into an affiliation of instability, a community of unruly minds’ (Bruce Citation2021, 148)?

Yet this is also a film that is grounded in specificities – of disabled experience, gender, race and nationality, among other dimensions. Accompanying Sylla’s reflections in voiceover is the image of the Atlantic viewed from Dakar, implicitly indexing the history of the transatlantic slave trade and the colonisation of Senegal, and inflecting the voiceover’s initial reflections on madness and fragmented identity with histories of racialised violence. While this context is never made explicit by Sylla’s film, scholarship at the nexus of race and disability encourages us to see these connections. Implicitly, this opening recalls ideas of ‘The Eugenic Atlantic’, Mitchell and Snyder’s adaptation of Paul Gilroy’s concept of the Black Atlantic to describe the interrelated roles of ableist and racialising discourses in the dehumanising practices of eugenics and the production of supposedly ‘biologically-based inferiorities’ (Mitchell and Snyder Citation2003). We might be reminded here too of Frantz Fanon’s reflections on colonialism’s production of psychopathologies.Footnote16 Indeed, with Fanon’s model of racialised visuality in mind (Fanon Citation2008), Une fenêtre ouverte’s opening reflections on vision and fractured identity take on a particular resonance, as though indexing what Fanon diagnoses as the sense of alienation violently imposed upon Black subjects within colonialist regimes – a sense of alienation described by Fanon as a form of mental illness (Fanon Citation2018). The image of the ocean here is not politically innocuous: operating ‘in the wake’ (Sharpe Citation2016), it recalls a history of racialised violence and damage, inviting a reading of disabled experience in Sylla’s film in this context. Joris Lachaise’s documentary, Ce qu’il reste de la folie/Remnants of Madness (2014), which focuses on a psychiatric hospital in Thiaroye, in the suburbs of Dakar, and features Sylla herself, draws explicit links to the legacies of colonialism through its reflections on colonial psychiatry. While such links are not overtly explored in Une fenêtre ouverte, they haunt the film’s exploration of madness and alienation.

In the following scene, Sylla describes a period of severe mental distress. Over hazy, overexposed footage of a road in Dakar, she recounts: ‘I was in a vacuum. I was delirious, talking to myself out loud. I was oblivious of the world around me’.Footnote17 The scene cuts to Sylla facing the camera, in a medium shot. ‘I was but fragments of Khady. I lost my mind’.Footnote18 With this account of the self undone, the film cuts to bleached-out footage again – of an elderly man dressed in rags, with a walking stick, moving very slowly. After lingering over these images, the film cuts back to Sylla as she outlines the genesis of Une fenêtre ouverte. Approximately ten years before, in 1994, Sylla had started filming a documentary about the ‘mentally ill’ wandering the streets of Dakar, but the film was never finished: the footage was overexposed and, a few months later, Sylla experienced the mental health crisis described above. She recounts that it was during the filming of this abandoned project that she met Aminta. From the very opening of the film, Sylla allows various entwined histories to emerge: the history of Une fenêtre ouverte and its predecessor, the history of her struggle with mental health and the history of her friendship with Aminta (all implicitly set against the backdrop of broader histories of slavery and colonisation, as signalled above).

The archival traces of the unrealised film from 1994, briefly recycled here, are significant for thinking about Une fenêtre ouverte, for they index Sylla’s earlier desire to explore cognitive disability in a collective context. In this early sequence, Sylla includes archival footage of others filmed in 1994 as well: a man sitting in a tree, looking at the camera; and a younger man standing, looking confused. While Une fenêtre ouverte is much more narrowly focused than the earlier film envisaged by Sylla, the inclusion of the archival footage of various disabled subjects signals an opening beyond the otherwise seemingly hermetic focus of the present film. Recent scholarship on the feminist dimensions of the unfinished film prompts us to see the speculative dimensions of these archival fragments, to read them as indexing a generative form of open-endedness. Alix Beeston and Stefan Solomon write of ‘a feminist transvaluation of the unfinished film’s signs of deficiency, recasting them as signs of possibility’ (Citation2023, 10–12), thereby countering a masculinist approach to film history that values a historicist faith in totality. We might then read Sylla’s unrealised film not as a failure but as an opening to ‘alternate horizons of possibility’ (Beeston and Solomon Citation2023, 15). In Une fenêtre ouverte, these archival traces allow us to glimpse a broader reflection on disability in a collective context that subtends the present film. At the same time, the inclusion of the incomplete film emphasises gaps, opacities and acts of (self-)undoing as feminist spaces of possibility.

Une fenêtre ouverte’s early shift from the past to the present day can also be read as a shift from glimpses of isolated male suffering in the archival footage to a realm of female suffering and companionship in which the film will spend the rest of its time. In close-up, Sylla reveals that, when she became very ill, Aminta used to visit her; we quickly surmise that their friendship has often been bound up with such acts of care. The film then cuts to a few seconds of archival footage showing the two women walking together: Aminta is walking quickly and purposefully, and Sylla is looking back at her (see ). Via Sylla’s voiceover, we hear: ‘She’d been sick for 25 years and exhibited her craziness with total indifference. I admired her resistance.’Footnote19 Evoking the trope of ‘the scandalous unruliness of a madwoman’ (Bruce Citation2021, 139),Footnote20 here the film frames Aminta as powerfully disruptive, as rebellious in her refusal to be closeted. And accompanying this is a reflection on the nascent bond between Sylla and Aminta – a relation of female friendship, care and solidarity that will form the basis of the making of this film.

At the same time, any romanticisation of Aminta’s earlier public displays of madness is held in tension with the film’s unflinching gaze upon her current circumstances. From Sylla’s reminiscence about Aminta’s past, the film cuts to Aminta in the present day. She sits in a courtyard, very still, looking offscreen (see ). She then looks briefly at the camera, as though slightly wary of it. The film cuts to a black screen, over which Sylla recounts that Aminta stopped coming to see her; with a cut to a medium shot of Aminta with her head in her hand, Sylla laments: ‘You’re locked up in this courtyard’; ‘Your mouth closed, your ears empty. You look askance at the world outside, at the side of the living’.Footnote21

This impression of incommunicability, stillness and isolation (the latter being a particular trope in filmic representations of disability [Norden Citation1994]) contrasts with the image of companionship, movement and freedom glimpsed in the archival footage. Sylla’s film opens with this framing of Aminta’s history as a movement from freedom to incarceration and from sociality to isolation. On one level, the film traces Sylla’s attempts to reverse this trajectory – to reintroduce sociality and freedom into Aminta’s life, through her repeated visits and her interventions in Aminta’s circumstances. Yet such a summary of the film also risks imposing a fixed, binary reading upon the relationship between Sylla (as active) and Aminta (as passive). As the film makes clear in the first few minutes, through the brief history of their friendship that it offers up, both Aminta and Sylla have adopted the position of carer at different times. Both women are shown to be vulnerable to the ravages of mental illness. And, as we shall see, rather than suggesting any teleology of healing or liberation, the film ultimately dwells in ambivalence – in relation both to Aminta’s freedom from incarceration and to the stakes of the friendship that it documents.

Mad methodologies

Aminta’s earlier refusal of the closeting of female madness, lovingly recalled by the film, seems to be echoed by Sylla’s own intimate, confessional disclosures – acts of speaking madness publicly. But these confessional acts are not to be confused with offering up transparent access to interiority. Within the ‘mad methodology’ of Sylla’s acts of apparent disclosure, experience is conveyed in intensely evocative yet opaque forms. Framed in close-up, Sylla recounts the period of madness that followed her attempt to make a film in 1994: ‘Shortly after I finished my overexposed film, I lost my mind and found myself on the other side. I could see what others could not see. The fractured eye. The antiquity of the glass bubble. The low-riding sky, the suffocating horizon’.Footnote22 Uttering these words, Sylla looks pained and confused. Surrealist deformations of language give shape to her experience, describing aberrant visions, a collapse of scale. This seems aligned with Glissant’s suggestion that strategies of opacity might embrace non-realist forms, especially in the rendering of traumatic experience (Clark Citation2016, 52–53; Glissant Citation1989, 198–200); hence the importance of poetic forms for Glissant, as for Sylla here. As Clark suggests, opacity may take place as a form of ‘obscure and tragic witnessing’, as a way ‘to shed light on horror’ (Clark Citation2016, 60).Footnote23

The sequence cuts to overexposed footage of a man walking, extracted from the incomplete 1994 film. These archival images surge up like the summoning forth of memory, functioning almost like a flashback. Yet the haziness of the image seems to signal a struggle to be brought to representation – a struggle then echoed by Sylla’s words: ‘I was experiencing pain that was invisible and therefore unspeakable. It’s difficult to identify it. How do you explain it to someone who has never felt it?’Footnote24 This is the unspeakable pain that the film attempts to reckon with.Footnote25 Sylla’s words and images (the overexposed footage) necessarily remain opaque. Her encounters with madness cannot be conveyed in transparent, graspable forms. Later she ruminates in voiceover: ‘Suicide. It seems to be the only way out’.Footnote26 In such moments, the film registers utter desperation. But acts of artistic creativity offer another way out too; as Sylla writes on a blackboard at one point: ‘Create or be annihilated’.Footnote27

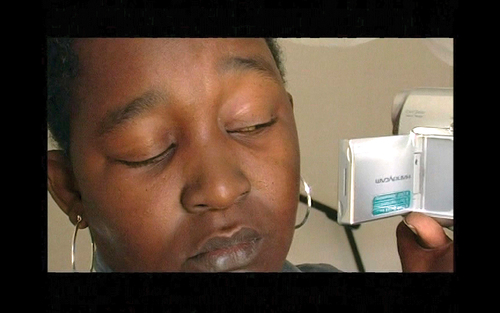

Sylla’s monologues to camera also foreground the embodied aspects of her struggles with madness, through the registering of her facial tics (Pugsley Citation2012, 218) or of the way in which she frowns with effort as she speaks. Sylla’s corporeal presence is then amplified as she reflexively turns the handheld camera, a Sony Handycam, upon her naked body. Over a close-up image of her belly, its fleshy folds stretched across the screen, pores and veins made visible, she describes her body in voiceover as ‘cumbersome’, as ‘enemy’ matter. The camera travels quickly over exposed skin – breasts, shoulder, neck – towards Sylla’s face. Her voiceover states: ‘Human intelligence is locked up in its fortress. The brain is attacked’.Footnote28 The sequence is unsettling in its close-up, corporeal engagement and in its gestures to the mind incarcerated, under siege. The references to time (‘Time has vanished. Only fleeting moments remain. Time is now inside the mind’) indicate a life lived in fragments rather than continuity.Footnote29 While there is intimacy and exposure here, indexed by the tactile framing of the body, the self is acknowledged as ungraspable, as unknowable – for the viewer and for Sylla herself. The figure of carcerality, of the mind imprisoned, gestures to broader histories of incarceration, rather like the image of the Atlantic with which the film opens, evoking a history in which, to borrow Bruce’s words, ‘imprisoned madness meets captive blackness’ (Bruce Citation2021, 1).

In this scene, disorientating close-ups and edits effect a disordering of the viewing experience. From a shot of Sylla filming her face with the handheld camera (see ), the scene cuts abruptly to a Handycam image of her belly button. Appearing so suddenly after the image of her face, the belly button looks momentarily like another eye. The disorientating edits and close-ups give expression to Sylla’s own radical sense of self-estrangement, yet they also create a dissonant mode of perception for the viewer. Drawing on Rudolf Arnheim’s reflections on the estranging qualities of close-up vision in cinema, Mary Ann Doane writes of the close-up’s ‘powers of delocalization and despatialization’: ‘The close-up hence constitutes a potential danger, the foreclosure of the spectator’s spatial orientation, the annihilation of the rationality of place’ (Citation2021, 31–32). Here and elsewhere in her text, Doane suggests that there is something maddening about the close-up: it annihilates rationality; it confuses (in ‘the apparent collapse of the oppositions between detail and totality’ [Citation2021, 48]); it provokes ‘delirious fascination’ (Citation2021, 32). Sylla harnesses these aesthetic powers of disorder here, cripping cinematic space as she reflects on her own struggles with madness.

The sequence intimately registers the self in its ‘critical condition’ (to borrow Nack Ngue’s term); it declares the Black female self as mad and dissonant, refusing to allow this self to remain unseen and unheard. Pugsley notes of this scene: ‘Reappropriating this foreign matter is posited by Sylla as a fundamental stage in the healing process, since it enables the individual to transcend otherness’ (Citation2012, 214). Yet the film seems hesitant about ideas of healing or transcendence. Perhaps we might read Sylla’s approach here as an act of Black feminist aesthetics and politics that viscerally registers the undoing of the self, rather than aiming at restitution. As Nack Ngue writes, in the context of Francophone Afro-feminist literatures of disability, ‘what of those narratives which do not proceed smoothly towards restituting normalcy, health, and, more broadly, narrative coherence?’ (Citation2012, 16).

Indeed, in Sylla’s film, any restitution of normalcy or coherence is refused, and dissonant acts of speaking out are privileged – not only through Sylla’s intimate reflections on her experiences of madness, but through the time and space devoted to Aminta’s lengthy diatribes. A striking sequence in this regard takes place towards the end of the film, when Aminta decides that they should go to Sylla’s house (so that she can talk more freely than she feels able to do in the courtyard). Sylla’s bedroom spontaneously acts as the mise-en-scène for Aminta’s loquacity, as the scene allows time and space for her expression of feelings about her mother. In an earlier discussion in the film, Aminta has claimed that her mother did not teach her how to breastfeed her first daughter. Here Aminta converts this into a stronger accusation, claiming that, in failing to teach her this, her mother effectively killed Aminta’s first daughter. She points to the fact that her mother gave birth to her youngest child at the same time, framing this matriarchal history through notions of rivalry, jealousy and conspiracy. She says (in Wolof):

You think I don’t know the reason? The truth is she never loved me. Secretly, she never loved me. I know everything that goes on. I know why she spies on me. I know what goes on. I knew it back when my daughter Mbayang Lo died. My mother gave birth to my sister Thiat. And Thiat is jealous of everything I have. Thiat is jealous.Footnote30

The film never takes an explicit view on the extent to which paranoid delusions might be shaping Aminta’s version of events. Rather, it allows time and space for an unfolding of this narrative of family trauma and tension, bearing witness to Aminta’s words and gestures, and to the neurodivergent rhythms of her subjectivity. She repeats fragments of information that we have heard earlier. The film does not intervene with an edit or a voiceover; it does not seek to ventriloquise Aminta’s concerns, or to convert this scene into what Pooja Rangan describes as ‘a timely, meaningful illustration’ (Citation2017, 118). It allows her to speak of her experience in a way that opens onto what Rangan calls, in her discussion of the autistic voice in documentary, a different ‘economy of voicing’ (Citation2017, 124). The protracted duration of the scene, its opening to repetition and errant speech, suggests a reshaping of film temporality here in terms of ‘crip time’ – what Alison Kafer describes as ‘a challenge to normative and normalising expectations of pace and scheduling’ (Citation2013, 27). Crip time ‘requires reimagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognising how expectations of “how long things take” are based on very particular minds and bodies’ (Kafer Citation2013, 27). If for Kafer, ‘rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds’ (Citation2013, 27), then this scene suggests a bending of the clock to meet Aminta’s body and mind. (In this context, the clock on the wall – somewhat conspicuous as it sits directly behind Aminta as she speaks – curiously accrues added significance.) The scene also resonates with Bruce’s conception of ‘madtime’:

a transgressive temporality that coincides with phenomenologies of madness. It includes the quick time of mania; the slow time of depression; the infinite, exigent now of schizophrenia; and the spiraling now–then–now–then–now of melancholia, among other polymorphous arrangements. As a critical supplement to colored people’s time, queer time, and crip time, madtime flouts the normative schedules of Reason, trips the lockstep of Western teleology, disobeys the dominant beat, and swerves instead into a metaphysical offbeat. (Bruce Citation2021, 32; original emphasis)

Yet the film is hesitant about framing this act of flouting ‘the normative schedules of Reason’ as a redemptive or emancipatory move. For, following this scene, we hear Sylla addressing her in voiceover: ‘Aminta Ngom, you can’t go on talking about your pain. After 25 years, talking about it gets you nowhere. People have stopped listening.’Footnote31 The scene fades to black, and then Sylla says in voiceover: ‘All you have left is silence’.Footnote32 This is followed by an image of a grave, recalling Sylla’s earlier reflections on suicide. Here the film veers away from the humanitarian impetus of documentary critiqued by Rangan (Rangan Citation2017). Une fenêtre ouverte does not frame the act of ‘giving voice to the voiceless’ as a necessarily redemptive one. It makes fraught its meeting with Aminta’s body and mind. Here Sylla’s film seems to resonate with the cautionary gesture in Pickens’s writing on Black madness: ‘This is not meant to be an emancipatory theory of agency for Black mad or mad Black subjects. Instead, this project may delineate the costs of hope and the aftermath of degradation’ (Pickens Citation2019, 16–17).

Entanglement and care

Indeed, it would be difficult to read this film in terms of ‘an emancipatory theory of agency’, not least because of its ethically fraught dimensions, especially in relation to the issues of consent and exposure raised in Pugsley’s reading. While Sylla insists on forms of mutual entanglement, emphasising parallels between Aminta and herself (for example, as Pugsley notes, ‘both women are filmed looking at themselves, Aminta in the piece of mirror and Sylla in the rotating screen of a portable camera’ (Citation2012, 216–17)), one wonders to what extent Aminta’s madness is being instrumentalised as part of Sylla’s exploration of her own suffering. Pugsley identifies some particularly unsettling aspects (Citation2012, 215–19), including the issue of informed consent and Aminta’s clear resistance to being filmed at times, as well as the money paid to the family for the film, which Aminta mentions at one point. Sylla openly includes such details, appearing to acknowledge the film’s ethically ambiguous dimensions. Certain scenes intensify a sense of unease. In one sequence, Sylla encourages Aminta to buy a wig. At the wig stall, Aminta is shown hallucinating, seemingly unsettled by the experience of being outside, away from home – an experience that has been somewhat thrust upon her by the filmmaker. Back in the courtyard, Sylla cajoles Aminta, now wearing her new wig, into looking at herself in a piece of mirror. ‘I already saw myself’, Aminta protests. We hear Sylla off-screen, presumably behind the camera: ‘Take another look, I want to film you’. Aminta looks at the camera self-consciously: ‘That’s enough’, she mutters. But the camera does not stop filming. There is a cut, but to the same place and time, as though the film is unwilling to abide by Aminta’s wishes. Such moments in Sylla’s film are fraught with ethical ambiguity, freighted as they are with asymmetries of power between filmmaker and subject.

Yet, while certain moments in the film read like overexposure, others invite a reading in terms of attentiveness and care, thereby linking to a developing field of thought in documentary and media studies more broadly.Footnote33 Indeed, Une fenêtre ouverte documents various acts of care, such as Sylla’s intervention in Aminta’s living circumstances, whereby she encourages her family to take her out for walks, allowing her to experience life outside the courtyard.Footnote34 Care takes place not only at the level of the filmmaker’s material intervention but through the film’s formal approach. For key to the film’s practice of care is its temporality, its patience and sustained engagement – what Debarati Sanyal describes in another context as ‘the solidarity of attention’ (Citation2022, 92). We have seen this above, for example, in the film’s opening to the ‘madtime’ of Aminta’s volubility.

Recalling a Glissantian generosity of relation, the film’s solidarity of attention is capacious. It extends alongside Aminta to include careful attention to Aminta’s mother and teenage daughter, Tiané, as well. The film features extended conversations with both women. In each scene, Sylla talks to the mother or daughter while Aminta is present (though she remains mostly silent). In the conversation with Aminta’s mother, Sylla encourages her to allow Aminta to go out for walks again, if she is accompanied, for example by her daughter, or by Sylla herself. Agreeing to this, Aminta’s mother then speaks of how hard things have been since the death of her husband (‘Their father bought everything. God is merciful. Sometimes my relatives help out. I always thank God when someone helps me’). The conversation is unsettling, begging the question of why Aminta has not been allowed out, accompanied, prior to Sylla’s intervention. At the same time, the scene allows for empathy with the mother’s position as carer. El Hadji Moustapha Diop writes of the scene’s ‘complex communicative ethics of “telling” silences, laconic understatements, and discreet gestures and body postures’ (Diop Citation2023, 83). He suggests that, during this conversation, ‘a parallel universe of meaning arises from deep within the cracks and gaps of surface social intercourse’, conveyed through

tight angles; swift cut-ins to frame a fleeting hunched shoulder denoting kersa (reserve, humility in Wolof culture); close-ups on seemingly anodyne gestures, like the mother clasping and unclasping her wrinkled hands or striking a dignified pose, thrusting a blank, inexpressive gaze out in the distance. (Diop Citation2023, 83)

Diop argues:

This is not so much to denote embarrassment or shame, […] much less to erect a fence around the domain of the private, as to signify a surplus of meaning that, while not conveyable in words, is eminently communicable, by dint of this very ineffability, as that ‘something more’ always fraying the edges of speech. (Diop Citation2023, 83; original emphasis)

Indeed, that ‘“something more” always fraying the edges of speech’ is the realm of opacity. And here opacity – created partly by the mother’s reticence, and partly by Sylla’s strategy of not probing further (which Diop reads as a gesture of empathy) – opens a space for untold sufferings to resound. Gestured to, yet left unelaborated, is a fuller account of the family’s difficulties in coping with Aminta’s mental health issues over the decades, especially in the context of poverty and the particular dynamics of social and economic oppression faced by (disabled) women within a ‘patriarchal and ableist’ nation-state (Erevelles Citation2011, 131). While left unspoken, we might sense here the absence of infrastructures of social care available to Aminta and her family, and the fact that, in such situations, the burden of care often falls on the family – a burden disproportionately shared by female family members. (No men are interviewed in the film, as though to register the absence of male support and the isolation of the women as they struggle with these issues.)

The scene of Sylla’s conversation with Aminta’s daughter, Tiané, is similarly both telling and opaque. Tiané seems reluctant to speak. On one level, she has the air of a bored and slightly embarrassed teenager, but the film’s patience allows us to sense again the undertow of an unspoken history of suffering, and of Tiané’s perhaps disproportionate share of the burden of caring for Aminta (which is about to be redoubled, given that she is now expected to accompany her mother on walks). Left unelaborated are the difficulties of growing up as the daughter of a mother suffering from mental health issues, and in a situation in which normative care relations are reversed, as the daughter – while still young – cares for the mother. The scene registers the profound alienation between mother and daughter: they barely look at each other or interact.Footnote35 The only time that Tiané addresses Aminta, it is to tell her that her skin looks dry and that she should cover her bare legs – a small exchange that, in its meanness, seems to index a hinterland of resentment felt by the daughter. Shortly after, Tiané yawns a little, as though to express her disengagement. Sylla looks deeply thoughtful, depressed, glancing at the camera and away again. ‘You should talk with your mother, Tiané’, she gently encourages. Tiané fiddles with her nose, looks down at her hand – gestures of boredom, displacement and ‘psychic withholding’ that signal a reluctance to interact, especially with her mother.Footnote36 Sylla suggests, in a gesture that seems playful but futile, that Tiané and Aminta might have a party together at some point. Once Sylla has prompted Tiané to leave, Aminta finally speaks up: ‘We never did anything together’, she says. The enormity of this – of the devastation involved for both mother and daughter – is left unspoken, but it resounds through this scene. In this sense, Sylla’s film intimates, in a capacious gesture of empathy, further forms of ‘unspeakable pain’. Lucy Fischer has traced the role of documentary film in registering the difficulties and ambivalences that structure mother–daughter relationships, exploring films such as Chantal Akerman’s News From Home (1976) and Su Friedrich’s The Ties that Bind (1985). While Une fenêtre ouverte is very different from these, not least in its Senegalese context, it also reflects the important role of non-fiction in offering intimate, difficult portraits of such relations. (Mbakam’s Les deux visages d’une femme Bamiléké/The Two Faces of a Bamiléké Woman [2018] is another important recent addition, by an African female filmmaker, to this corpus of mother–daughter non-fiction films.)

In relation to these scenes with both Aminta’s mother and her daughter, Diop writes of

Sylla’s empathetic camera, in coming to grips with how both women enforce a strict observance of the code of silence on a taboo subject (i.e., their own experiential roller coasters as Aminta, mother and daughter to each, struggles to cast out her demons). (Diop Citation2023, 85)

Through its patient approach and its multidirectional empathy – capacious enough to remain open to Aminta, her mother and Tiané all at once, while also sensing their conflicting stories and investments – the film allows for realms of the unsaid to be felt. This recalls Cae Joseph-Masséna’s reflections, in the context of a reading of ‘mad Afro-feminist phonographies’, on ‘Black women’s normative assignations to social audibility and inaudibility’ (Citation2021, 102). What Sylla’s film stages here is not a normative correction or redemption whereby women’s voices are heard in place of silence. It is less binary than this. Her film is also interested in zones between audibility and inaudibility (in ‘that “something more” always fraying the edges of speech’, as Diop puts it).

Beyond the family

Une fenêtre ouverte is also deeply interested in what lies beyond the family, most obviously through its foregrounding of the friendship between Sylla and Aminta – a ‘sisterly’ bond reaching beyond the blood-ties of a family revealed in Sylla’s film to be a site of not only resentment and tension but paranoia, jealousy, control and incarceration. In some senses, Une fenêtre ouverte might be viewed in the context of theories of family abolition.Footnote37 Given the pain and suffering often experienced within families, ‘[h]ow’, asks Sophie Lewis, ‘does the family still serve as the standard for all relational possibilities?’ (Citation2022, 10).Footnote38 Perhaps my invocation of a ‘sisterly’ bond between Aminta and Sylla falls into that same trap.Footnote39 But through its portrait of enduring friendship between the two women, Une fenêtre ouverte also reflects on bonds that reach far beyond the family’s blood-ties and ‘proprietary concepts’, extending towards what Lewis describes as ‘something quite … unfamilial. Namely: acceptance, solidarity, an open promise of help, welcome, and care’ (Lewis Citation2022, 9; original emphasis). While signalling the potentially queer dimensions of Une fenêtre ouverte’s reflections on care, this also intersects with a move beyond the family identified within disability studies (thereby recalling alliances between crip and queer perspectives). Reflecting on how disability can interrupt ideas of family resemblance and genealogical descent, Petra Kuppers suggests: ‘There is no necessary family resemblance for disabled people, we mostly have to make our families ourselves, choose our community’ (Kuppers Citation2009, 233; cited in Erevelles Citation2011, 55). In Une fenêtre ouverte, the friendship between Sylla and Aminta is shown to be warm and affectionate – they talk together, smile, hold hands – contrasting markedly with the scenes of Aminta’s estrangement from her mother and daughter. Sylla’s affection towards Aminta is mirrored by the tender gestures of her camera, through the sustained tactile close-ups that lovingly detail Aminta’s face and hands.

In their study of women’s filmmaking in Africa, Lizelle Bisschoff and Stefanie Van de Peer identify ‘a deliberate prioritising of female relationships’, of ‘sororities, sisterhoods, covens, assemblies, networks’ in recent films. They read such representations of female friendship – taking place within patriarchal contexts oppressing women – as ‘embedded in political solidarity between women’, and as powerful in crossing boundaries between private and public forms of alliance (Bisschoff and Van de Peer Citation2021, 88–89). One example that they cite is the work of Senegalese–French filmmaker Katy Léna N’diaye, whose two documentaries about traditions of female wall-painting and decoration – Traces, empreintes de femmes/Traces, Women’s Imprints (2003) and En attendant les hommes/Waiting for Men (2007) – privilege a focus on ‘female communities and networks of friendship and support’ (Bisschoff and Van de Peer Citation2021, 98). Une fenêtre ouverte joins this trend of foregrounding friendship, solidarity and community among women in recent African cinema. Yet it is ground-breaking in registering the place of female friendship within experiences of disability, and of mental health issues in particular. At the same time, while the friendship between Sylla and Aminta is in many ways a refuge, a place of care, the film is not idealistic about their bond. The final stages of the film introduce the possibility of abandonment, as Sylla rather abruptly takes her leave. Over an image of Sylla sleeping, she reflects in voiceover on the unspeakability of Aminta’s pain, and then says: ‘We are alike and yet so different. It’s our experience of the world that separates us.’Footnote40 While this scene is one that reflects on their commonalities – ‘This path towards you leads me to myself’ – it also seems to presage their separation.Footnote41 Over images of her writing desk, Sylla says in voiceover: ‘Just how much of myself might I recognise in you? I think it’s time that I stop.’Footnote42

The next scene cuts to the film’s final conversation between Sylla and Aminta. They are discussing Sylla’s plans to travel and Aminta’s lack of wanderlust. ‘Why would I want to travel? For what reason?’, Aminta asks. ‘For the pleasure of it!’, Sylla replies. For all the commonalities traced by the film, their experiences and world views are markedly different – not least because one is a well-travelled writer and filmmaker, and one is an unemployed woman living in poverty and mostly confined to a courtyard in Dakar. Their different positions have also been marked linguistically throughout the film, with Aminta speaking in Wolof and Sylla’s voiceovers and monologues to camera being in French. The film is careful about allowing these differences to be registered. While it is interested in the overlaps and connections between the experiences of the two women – especially in relation to madness – it has moved beyond the figure of mirroring with which the film opens. And with this, Sylla walks away towards the handheld camera, and away from Aminta.

The final shot of the film is a blurred image of the ocean, accompanied by Sylla’s voiceover: ‘The wandering mentally ill are not wise men. They’re people whose pain has shattered them. Even their walking is a form of resistance. […] One can find healing through walking.’Footnote43 This recalls of course the archival footage of the mentally ill wandering the streets of Dakar, glimpsed early in the film, and, more generally, the pain involved in experiences of madness that the film explores. At the same time, these closing moments hold out the (non-teleological) possibility of healing, of therapeutic futures of wandering, recalling Sylla’s intervention in arranging for Aminta to venture out walking again. Re-read in this context, the archival fragment of Aminta proudly walking the streets – included by Sylla early on in the film – does not simply document Aminta’s past; it can also be read as opening to a different future, to ‘alternate horizons of possibility’ (Beeston and Solomon Citation2023, 15).

In its feminist attentiveness and its mad methodologies, Une fenêtre ouverte is a film that highlights issues of cognitive disability shaped by gender and race in a contemporary Senegalese context. Offering a counter-narrative to ‘ablenationalist’ discourses, Sylla’s film embraces Black female disabled subjectivities that have been historically constructed as abject or aberrant. Through forms of ‘mad speech’ (poetically crafted by Sylla, improvised by Aminta), a Black feminist cripping of time and space, and a questioning of emancipatory or healing coherence, the film embraces dissonance as it seeks ‘to meet disabled bodies and minds’. While Une fenêtre ouverte centres on a female friendship that offers refuge from the anguish of family relationships, it also refuses any idealisation of that friendship, exploring its tensions and ambiguities. At the same time, the film’s multidirectional empathy extends to the various women at its heart – not only to Aminta and Sylla, but to Aminta’s mother and daughter too. In all of this, Sylla’s poetics of opacity seeks ‘[t]o feel in solidarity’ (to echo Glissant), and to explore forms of pain that sit upon the threshold of knowability, without ever assimilating or mastering what is encountered there.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a paper delivered at the BAFTSS conference at the University of Lincoln in April 2023, as part of the French and Francophone Screen Studies Special Interest Group (SIG) panel, co-organised by Kate Ince and Ginette Vincendeau. I am grateful for their support. Warm thanks also to Mariama Sylla Faye for generously talking with me about her sister Khady Sylla’s filmmaking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura McMahon

Laura McMahon is an Associate Professor in Film and Screen Studies at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of Cinema and Contact (Legenda, 2012) and Animal Worlds: Film, Philosophy and Time (Edinburgh University Press, 2019), and the co-editor of Animal Life and the Moving Image (BFI, 2015). She is currently working on a project on feminist historiography and archival engagements in recent moving image practice.

Notes

1. The film’s credits cite Charlie van Damme as co-director. In line with previous scholarship on the film, I refer to Sylla, as the main director of the documentary, by her surname, and to Aminta by her first name.

2. Michael Renov defines ‘domestic ethnography’ as ‘a mode of auto-biographical practice that couples self-interrogation with ethnography’s concern for the documentation of the lives of others’, where subjects function ‘less as a source of disinterested social scientific research than as a mirror or foil for the self’ (Renov Citation2004, 216; cited in Pugsley Citation2012, 217).

3. I build here on Valérie K. Orlando’s conception of Sylla’s filmmaking as embedded in an Afrocentrist womanist approach. Orlando situates Sylla’s work in relation to earlier filmmaking by Safi Faye (Senegal) and Anne-Laure Folly (Togo) and alongside more recent films by Fatou Kandé Senghor (Senegal), Fanta Régina Nacro (Burkina Faso) and Tsitsi Dangarembga (Zimbabwe) (Orlando Citation2017, 67).

4. At one point, Sylla empties out her handbag, revealing a pile of medication used for the treatment of various conditions (including acute depression, psychosis and schizophrenia), but her voiceover simply lists the names of the different drugs without specifying any symptoms.

5. Sasha Rossman refers to Sylla’s ‘conceptual embrace of opacity’ in her review of Une fenêtre ouverte (Rossman Citation2014, 258). I borrow the term ‘poetics of opacity’ from literary analyses drawing on Glissant; see Clark (Citation2016) and Joseph-Masséna (Citation2021).

6. ‘La transparence lumineuse est finalement trompeuse. Il faut réclamer le droit à l’opacité. Il n’est pas nécessaire de comprendre quelqu’un – dans le verbe comprendre il y a prendre – pour désirer vivre avec.’ The translated version (including parenthetical addition) cited here is drawn from Humphries (Citation2005, xxxii–xxxiii).

7. The film’s title is explicitly referenced when Sylla’s voiceover refers to the ‘open window’ of her childhood, during a staged reconstruction of herself as a young girl; for Sylla, it figures the separation between herself ‘inside’ and the rest of the world outside.

8. A 2020 report demonstrates the lack of mental health provision in Senegal, with chronic understaffing in this area. See ‘Member State Profile: Senegal’, Mental Health Atlas (2020).

9. Here Van Dam references Diop (Citation1997, 57, 76).

10. See Schalk (Citation2018), especially the introduction, for an acknowledgement of these gaps, accompanied by a detailed reading of early work on race within disability studies.

11. See, for example, Erevelles (Citation2011), Puar (Citation2017), Pickens (Citation2019), Schalk (Citation2018), Schalk (Citation2022) and Chen, Kafer, and Ki et al. (Citation2023).

12. See, for example, Fraser (Citation2016), McRuer (Citation2019) and Mogk (Citation2013).

13. Julie Nack Ngue has written on cinema under the name of Julie C. Van Dam; see Van Dam (Citation2016).

14. ‘Tu te regardes dans un miroir brisé. Tu vois des morceaux de ton visage. Ton visage est en miettes. Et celui qui te regarde dans le miroir brisé, il voit des morceaux d’images de ton visage. Lequel d’entre vous arrivera à reconstituer le puzzle?’

15. ‘Peut-être n’êtes-vous pas du même côté du miroir?’

16. See, for example, ‘Colonial War and Mental Disorders’, in The Wretched of the Earth (Fanon Citation2004), and ‘Psychiatric Writings’, in Alienation and Freedom (Fanon Citation2018).

17. ‘C’était le vide. Je délirais, je monologuais à haute voix. Je n’avais aucune idée du monde qui m’entourait […].’

18. ‘J’étais des fragments de Khady. Je basculais dans la folie.’

19. ‘Elle était malade depuis 25 ans et exhibait sa folie librement sans craindre la provocation. Je l’admirais pour sa résistance.’

20. Bruce uses this phrase in discussion of representations of the singer Lauryn Hill.

21. ‘Tu es enfermée dans cette cour’; ‘Bouche close, oreilles vides. Tu jettes des regards de travers, de l’autre côté, du côté des vivants.’

22. ‘Quelque temps après le film surexposé, je tombais malade et passais de l’autre côté. Je voyais ce que les autres ne voyaient pas. L’oeil disloqué. L’antiquité de la bulle de verre. Le ciel devenu trop bas, l’horizon trop près.’

23. For reflections on opacity that draw on Glissant in the context of moving image practice, see, for example, Keeling (Citation2019) and Estefan (Citation2020).

24. ‘Je faisais l’expérience de cette douleur indicible puisque invisible. C’est difficile à localiser. Comment l’expliquer à quelqu’un qui ne l’a jamais ressenti?’

25. Dan Moshenberg writes: ‘somehow, out of the impossible and the untranslatable, Khady Sylla made film, made art, and made sense’ (Moshenberg Citation2013).

26. ‘Le suicide. Il semble que ça soit la seule issue.’

27. ‘Créer ou s’anéantir.’

28. ‘L’intelligence humaine dans son château fort. Le cerveau attaqué.’

29. ‘Il n’y a plus de temps. Il n’y a rien plus que les instants. Le temps est à l’intérieur du cerveau.’

30. Here and elsewhere, I cite speech in Wolof in translation, as provided by the subtitles.

31. ‘La souffrance, Aminta Ngom, tu ne peux pas en parler. Parler du même sujet au bout de 25 ans, ça te donne quoi? Plus personne pour t’écouter.’

32. ‘Il ne reste plus que le silence.’

33. See, for example, two recent special journal issues on care in the context of film and media studies: An and Witt (Citation2022) and Banner and Zeavin (Citation2023).

34. Yet this is complicated by the fact that Aminta says at various points that she would prefer to stay at home.

35. Tabara Korka Ndiaye writes of the painful estrangement between Aminta and her daughter in the context of a broader consideration of the film’s grappling with difficult emotional terrain: ‘Sylla takes us on the paths of pain and silence, stigma, exclusion, confinement, otherness (othering), suicide and fear (of oneself and of others) – a surge of emotions that are at times difficult to name’ (Ndiaye Citation2023).

36. Fischer uses the term ‘psychic withholding’ in her discussion of Akerman’s News from Home (Fischer Citation1996, 192).

37. I posit this connection tentatively and speculatively here, bearing in mind the different stakes of such theories for Black (African) subjects, especially in the context of the destruction of Black kinship ties through slavery (Erevelles Citation2011, 54–55).

38. In African contexts, including Senegal, one could cite here practices of FGM, often organised by family members.

39. Diop also writes: ‘The film traces out the genealogy of this resumed bond of sisterhood’ (Citation2023, 77).

40. ‘Nous nous ressemblons mais nous sommes différentes. Ce qui nous sépare, c’est notre expérience de l’extérieur.’

41. ‘Ce chemin vers toi me ramène à moi.’

42. ‘Jusqu’à quel point pourrais-je m’apercevoir en toi? Je pense qu’il est temps que je m’arrête.’

43. ‘Les fous errants ne sont pas des rois-mages. Ce sont des personnages à la conscience fracassée par la douleur. Même leur marche est une forme de résistance. […] On peut guérir en marchant.’

References

- Anon. 2020. “Member State Profile: Senegal.” In: Mental Health Atlas. World Health Organisation. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mental-health/mental-health-atlas-2020-country-profiles/sen.pdf?sfvrsn=4f55077f_6.

- An, G., and C Witt, eds. 2022. “Ethics of Care in Documentary Filmmaking since 1968”. In French Screen Studies 22 (1).

- Banner, O., and H Zeavin, eds. 2023. “Media Histories of Care”. In: Feminist Media Histories Vol. 9.

- Beeston, A., and S. Solomon. 2023. Incomplete: The Feminist Possibilities of the Unfinished Film. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Bisschoff, L., and S. Van de Peer. 2021. Women in African Cinema: Beyond the Body Politic. London: Routledge.

- Bruce, L. M. J. 2021. How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Creativity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chen, M. Y., A. Kafer, E. Ki, and J.A. Minich, eds. 2023. Crip Genealogies. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Clark, C. 2016. “Resistant Literatures; Literatures of Resistance?: The Politics and Poetics of Opacity in Kateb and Dib.” Research in African Literatures 47 (3): 50–69.

- Diop, E. H. M. 2023. “Revisiting the ‘Domestic Ethnography’ Approach in Khady Sylla’s Une Fenêtre Ouverte.” In Francophone African Women Documentary Filmmakers, edited by Suzanne Crosta, Sada Niang, and Alexie Tcheuyap, 65–94. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Diop, M-C. 1997. “Quelle approche des ‘fléaux sociaux’?” In: La Folie au Sénégal, edited by Ludovic d’Almeida, 55–83. Dakar: Association des chercheurs sénégalais.

- Doane, M. A. 2021. Bigger than Life: The Close-Up and Scale in the Cinema. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Erevelles, N. 2011. Disability and Difference in Global Contexts: Enabling a Transformative Body Politic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Estefan, K. 2020. “Witnessing the Worldly within the Imperial Commons.” World Records Journal 4. https://worldrecordsjournal.org/our-violent-commons-witnessing-the-worldly-within-the-imperial-commons/.

- Fanon, F. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth. translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press.

- Fanon, F. 2008. Black Skin, White Masks. translated by Charles Lam Markmann. London: Pluto Press.

- Fanon, F. 2018. Alienation and Freedom. edited by Jean Khalfa and Robert J. C. Young, translated by Steven Corcoran. London: Bloomsbury

- Fischer, L. 1996. Cinematernity: Film, Motherhood, Genre. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fraser, B, ed. 2016. Cultures of Representation: Disability in World Cinema Contexts. London: Wallflower.

- Fraser, B. 2018. Cognitive Disability Aesthetics: Visual Culture, Disability Representations, and the (In)visibility of Cognitive Difference. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Glissant, E. 1989. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. translated by J. Michael Dash. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Glissant, E. 1993. “Sur la trace d’Édouard Glissant.” Le Nouvel Observateur 1517: 122–123.

- Glissant, E. 1997. Poetics of Relation. translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Humphries, J. 2005. “Introduction”. In: Glissant, the Collected Poems of Édouard Glissant, edited and with an introduction by Jeff Humphries, translated by Jeff Humphries with Melissa Manolas, xi–xxxiv. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Joseph-Masséna, C. 2021. “Mad Afro-feminist Phonographies as Dis/abled Worldmakings in Marie-Célie Agnant’s The Book of Emma.” L’Esprit Créateur 61 (4): 101–113.

- Kafer, A. 2013. Feminist Queer Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Keeling, K. 2019. Queer Times, Black Futures. New York: NYU Press.

- Kuppers, P. 2009. “Towards a Rhizomatic Model of Disability: Poetry, Performance, and Touch.” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies 3 (3): 221–240.

- Lewis, S. 2022. Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation. London: Verso.

- McRuer, R., ed. 2019. “Focus: Cripping Cinema and Media Studies.” Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58 (4).

- Mitchell, D., and S. Snyder. 2003. “The Eugenic Atlantic: Race, Disability, and the Making of an International Eugenic Science, 1800-1945.” Disability & Society 18 (7): 843–864.

- Mitchell, D., and S. Snyder. 2010. “Ablenationalism and the Geo-Politics of Disability.” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies 4 (2): 113–126.

- Mogk, M. E., ed. 2013. Different Bodies: Essays on Disability in Film and Television. Jefferson: McFarland & Co.

- Moshenberg, D. 2013. “The Monologue of Her Silence.” Africa is a Country, 27 December, https://africasacountry.com/2013/12/khady-sylla-made-films-out-of-the-impossible-and-the-untranslatable.

- Nack Ngue, J. 2012. Critical Conditions: Illness and Disability in Francophone African and Caribbean Women’s Writing. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Ndiaye, T. K. 2023. “To Create or to Perish.” Africa is a Country, 17 January, https://africasacountry.com/2023/01/to-create-or-to-perish.

- Nichols, B. 1991. Representing Reality. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Norden, M. 1994. The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Orlando, V. K. 2017. New African Cinema. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Pickens, T. A. 2019. Black Madness:: Mad Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Puar, J. 2017. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Pugsley, B. 2012. “Ethical Madness? Khady Sylla’s Documentary Practice in Une Fenêtre Ouverte.” Nottingham French Studies 51 (2): 204–219.

- Rangan, P. 2017. Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Renov, M. 2004. The Subject of Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rossman, S. 2014. “An Open Window by Khady Sylla.” African Studies Review 57 (1): 257–258.

- Sanyal, D. 2022. “Documenting the Undocumented: Testimony, Attention and Cinematic Asylum in La Blessure.” French Screen Studies 22 (1): 91–103.

- Schalk, S. 2018. Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Schalk, S. 2022. Black Disability Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sharpe, C. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Shohat, E. 2006. “Post-Third Worldist Culture: Gender, Nation, and the Cinema”. In: Taboo Memories, Diasporic Voices, 290–329. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Van Dam, J. C. 2016. “Re-viewing Disability in Postcolonial West Africa: Ousmane Sembène’s Early Resistant Bodies in Xala.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 10 (2): 207–221.