ABSTRACT

Deep Ellum in Dallas, Texas is a rich example of a community that has grown for over one hundred years thanks to the arts. This case study explores how the Deep Ellum district has endeavored to keep art, music, culture and history at the center of how the community develops. Several local organizations have organized and channeled the efforts of property and businesses owners, residents and patrons invested in the neighborhood to amplify a shared vision. What makes the joint efforts authentic and robust are the cross-sector engagement and longstanding commitment to Deep Ellum of the stakeholders involved. Strategic planning and an increasingly integrated network of local organizations could not create but merely serve to leverage the passion, artistic contribution, and resource investment already present. The district demonstrates that consistency and collaboration across a variety of stakeholder types can help keep the arts at the center of the neighborhoods’ development.

Introduction

The arts are known for many things. Consistency and stability are not among them. That said, the arts reliably foster community and economic development (Americans for the Arts, Citation2017). Deep Ellum, located in Dallas, Texas, is a rich example of a community that has grown and developed for over one hundred years thanks to the arts. As the birthplace of jazz and blues in North Texas (Govenar & Brakefield, Citation2013), Deep Ellum is said to be the Soul of Dallas. Over the decades, musicians, writers, artists, and other creative artists have been drawn to the district by the venues and coffee houses offering space to see and learn from other artists, produce, perform, and exhibit as well as the availability of ample affordable space and blank “canvases” in and upon converted warehouses and old commercial buildings. Residents have been drawn by the urban environment, walkability, and area amenities, while businesses have been attracted to the creative, independent, and entrepreneurial spirit Deep Ellum espouses. Property owners have recognized and come to the district for the investment opportunity. Each of these interests, in their own way, have been sparked by the arts and by the idea Deep Ellum engenders. An enduring creative ethos steeped in the neighborhood’s history as the birthplace of jazz and blues in North Texas (A. Govenar & Brakefield, Citation2013) and a crossroads for diverse commercial interests has taken hold in the neighborhood and become popular lore.

Examples across the country demonstrate that art sparks both direct and indirect economic benefits. These benefits include attracting individuals, firms, and development when concentrated in a particular geographic area like Deep Ellum (McCarthy et al., Citation2004). However, history also teaches us that arts may ignite interest in development, generating growth that risks displacing the very people and artistic enterprises that shaped the character and appeal of the place. For decades, the debate has simmered in Deep Ellum about neighborhood identity being lost to growth in boom times or crime in bust times. The essential question eliciting fiery passion and frequent conjecture for this neighborhood has been, “Can Deep Ellum sustain being a thriving artistic and cultural center even as it grows, changes, and welcomes new development?”

As other communities grapple with the question, “Can artistic culture coexist for any duration with robust economic development?” this case study of cross-sector collaboration in Deep Ellum illustrates one community’s lessons, highlighting successes and revealing ongoing challenges. Furthermore, the case of Deep Ellum advances Turrini’s et al.’s (Citation2010) findings how an initially informal group evolving into an increasingly structured nonprofit-led network may advance both economic and community development infused with the arts. This case study presents a brief history of Deep Ellum and the community engagement of the district. It then reports key stakeholders and organizations within the district and their roles in the strategic and cultural planning process. Finally, limitations and opportunities for additional research are reviewed before concluding.

Deep Ellum history and context

Deep Ellum was established in 1873 just east of downtown Dallas (DeepEllumTexas.com). While the neighborhood emerged as a residential freedmen’s town, an African American community built by freedmen after the Civil War, it quickly became an industrial, commercial, and entertainment district in part due to its proximity to “Central Track,” a main crossroads of the Texas Central Railroad in Dallas connecting Texas to the broader region. Deep Ellum was home to the first cotton gin factory in the region and later one of the earliest Model T Ford factories. But Deep Ellum’s main claim to fame has always been its music. By the 1920s, the neighborhood was a hotbed for early jazz and blues music, serving as a launchpad for Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, (A. Govenar & Brakefield, Citation2013), and Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, among others (DeepEllumTexas.com).

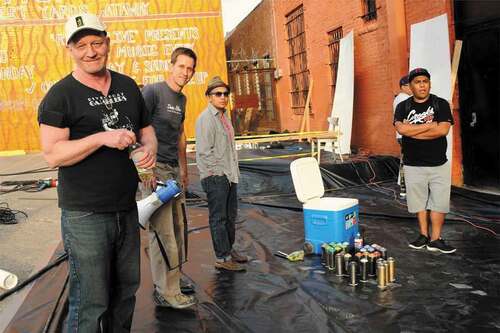

Figure 1. Teal Suns poses in front of his portraits for Deep Ellum blues alley of blind lemon Jefferson and blind Willie Johnson.

Deep Ellum declined following the removal of the streetcar lines by 1956 and nationwide movements toward suburbanization. By the 80ʹs after decades of vacancy and decay, Deep Ellum was largely neglected by City leaders. Discussions about demolishing the whole area to make way for expanded downtown development loomed. As one longtime property owner, Rich Cass, put it, “my father began his involvement in property ownership in 1979 and I was still in school back in those days. That was our introduction to a forgotten neighborhood” (R. Cass, personal communication, 19 August 2021). A recession in the 80ʹs impacting the whole region once again left the district to its own devices. Behind the scenes of this seeming disrepair were a series of Deep Ellum property owners, artists, residents, and entrepreneurs whose individual commitments and later collective efforts beginning in the 1980ʹs and gaining steam in the 1990ʹs were instrumental in bringing the district back to life.

Deep Ellum’s music scene reignited and now-legendary venues like Trees, Club Dada, and the Bomb Factory launched local bands like Old 97s, Toadies, Tripping Daisy, the New Bohemians, and countless others (P. Freedman, Citation2011). Artists and galleries flocked to Deep Ellum through the 90ʹs, taking advantage of cheap rents, large open commercial spaces and using the walls of Deep Ellum like living canvases. Creative offices also gained a foothold in Deep Ellum with firms including Radical Computing, Mark Cuban’s first major venture, and other tech firms converting old warehouses for reuse.

The Deep Ellum Association (DEA), formed in the early 1990s, instigated several artistic initiatives improving the neighborhood while building relationships and trust amongst local stakeholders. What made local stakeholders’ and burgeoning organizatons’ revitalization efforts attractive was an intentional and consistent leveraging of the arts and the creative industries from the outset. What made their efforts authentic was their collaboration across stakeholder types, owners with artists, residents with business owners and beyond. What has made their efforts robust and enduring, has been their long-term commitment.

By the great recession in 2008, the unique character of Deep Ellum combined with the groundwork of authentic engagement and continuous commitment of its stakeholders positioned it to rebound in the 2010ʹs. In 2009, the DEA was reformed as two entities with related purposes but distinct perspectives and roles, the Deep Ellum Foundation (DEF) and Deep Ellum Community Association (DECA). Despite interorganizational conflicts in the preceding two decades, a stable partnership between the DEF and DECA grew between 2010 and 2020. Building upon the collective artistic and entrepreneurial endeavors of the 1990ʹs and early 2000ʹs, Deep Ellum’s people and these local organizations used the arts, a solidifying creative ethos and hard work throughout 2005 to 2015 to continue to promote the district, create appealing places within the neighborhood and foster community. As newcomers were attracted to this spirited neighborhood when the United States was emerging from the recession, they adopted the creative ethos and reinterpreted artistic expressions in new ways bringing new life.

The DEF led strategic and cultural planning efforts from 2018 to 2020 in partnership with the DECA, engaging other important local organizations and key stakeholders in the process. The resultant plans codified uplifting local arts and culture as a neighborhood priority. This redirected organizational focus and strengthened stakeholder resolve to advance identified action items supporting that priority. In turn, the network’s organizing efforts and recent achievements increased renown and resource investment in (Deep Ellum between Citation2020; Deep Ellum Foundation Metrics, Citation2021).

Deep Ellum’s unique walkability, proximity to downtown and convenient transportation options as well as its artistic energy spurred significant real estate investment. Most recently, the district has experienced tremendous growth in new office and residential development, with the number of residential units expanding over 75% between 2018 and 2020 alone from just over 1,600 to 3,600 (Deep Ellum Foundation, Citationn.d.). The office boom promises to be even greater with an anticipated increase of more than 90% in available office square footage in the early 2020ʹs (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2019). Meanwhile, the neighborhood continued to attract entrepreneurs and new business ventures. A mere 0.5 square miles, in 2019 the district was home to over 350 businesses and hosted approximately 1.2 million unique visitors (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2019).

Mixed use development means that office workers and residents provide foot traffic in the district across more hours during the week. This presents the opportunity to foster a sustainable urban ecosystem. This momentum is bolstered by Texas’ and Dallas’ broader development trends. Texas is the ninth largest economy in the world by GDP (Texas Economic Development Corporation, Citation2021) and right up until the pandemic, the Dallas region was attracting 323 new residents per day (Dallas Regional Chamber, Citationn.d.). As Dallas is well poised to weather the pandemic and is still experiencing robust infill development, Deep Ellum is expected to continue to generate high levels of interest, investment, and change in the coming years.

Methods

This case study integrates statistics on economic development from local and national sources with material from internal documents of the DEF and DECA. Most importantly, it includes the firsthand accounts of neighborhood stakeholders involved in the district’s cultural development.

Furthermore, it is important to state the position of the author. As the current Executive Director of DEF, I wrote this article from the perspective of one of the primary leaders directly involved in advancing cultural planning in and for Deep Ellum over the last several years. As a relatively young adult, public policy professional, and transplant from the East coast with only recent experience in the district, I relied heavily upon individual interviews with DEF board members, longtime residents and business owners to understand both organizational and district history. While academic journals and the very few scholarly works upon Deep Ellum specifically are referenced in this article, I am not an academic or historian but a practitioner and, as such, the perspective presented, while rich, is narrow in scope. Though DEF proactively works to attract individuals of diverse backgrounds to serve on committees and in leadership roles as well as to inform our planning and priorities, I am a single author and individual of Caucasian decent who interviewed primarily other individuals of Caucasian decent for this article. As such, there are additional important limitations to the perspective presented in this article especially in light of Deep Ellum’s rich history as a center of African American commerce and life.

Deep Ellum’s Key Stakeholders

Deep Ellum has benefitted from the time, investment, and talent of several key categories of stakeholders that worked together to advance the neighborhood’s economic development through the arts. These include the property owners, business owners, homeowners, the DEA, the DEF, and the DECA. Specifically, Deep Ellum’s property owners provided financial resources to initiate and support artistic endeavors, took the lead navigating government bureaucracy, and making important relational connections for the district. More broadly, they have set the overarching trajectory of the district through their tenant policies and leasing practices guiding which types of businesses operate in the district. With several key property owner families and companies in the district having owned for decades, the property owners are also the most tenured of the key stakeholder groups. Business owners have been essential in providing the spaces that have continuously enabled the arts and artists to flourish. Residents, especially a few formidable homeowners, have been critical to helping local organizations build quality of life in the neighborhood with a focus on infusing the arts in every day. Specific arts events and initiatives like the community garden have been led and sustained by longtime residents. Finally, artists and creative entrepreneurs have continuously enlivened Deep Ellum through sharing their unique talents, voices, and visions. While government agencies have been engaged in Deep Ellum’s development, government has not been the impetus or a key contributor to the area’s cultural and economic advancement. The key to understanding the success of the collaborations between these stakeholders is understanding the history of the local organizations the stakeholders formed together.

The Deep Ellum association

The DEA was founded in the early nineties, several property owners with significant investments in the neighborhood banded together with the goals of addressing crime, promoting the area and presenting a united front to city hall leaders. As Rich Cass, longtime property owner and current DEF Board member put it:

What we were trying to do as a group of owners was to try and have some communication and cohesion to battle crime, to try to have united front against the City who was never our friend … We were productive and organized but not to the extent as we are today because the neighborhood wasn’t where it is at today (R. Cass, personal communication, 19 August 2021).

The group began as a loose coalition of those willing to lend their time to advocate for the district. While they met consistently, there was not a regular meeting schedule nor a well-defined set of tasks and goals. Formal incorporation and bylaws followed several years later. That said, the group successfully worked together to host some of the district’s earliest art-centric public events beginning in 1993. These included the Walk on Walls and TunnelVisions, which paved the way for the district’s collection of over 100 murals today, and the Deep Ellum Arts Festival. Each event took advantage of public right-of-way in the form of sidewalks, streets, and the walls of a tunnel between downtown and Deep Ellum to bring together artists and attract visitors.

The Deep Ellum foundation

In 1999, several of the property owners involved in the DEA petitioned the City of Dallas to form a Public Improvement District (PID) for the Deep Ellum area. In the City of Dallas and State of Texas, public improvement districts enable government-contracted entities to receive assessments on property taxes above the standard level for that jurisdiction. A certain threshold percentage of property owners must elect to participate in the public improvement district, paying the additional tax rate, and the PID must be renewed at some regular interval approved by the City Council. A public improvement district, in turn, is obligated to provide services above the standard city services for that specific neighborhood or geographic area taxed. Allowable services are state-defined and may include physical and capital improvements, marketing, and promotion of the area, providing for security services and more.

The DEF, a 501(c)(3) was thus born to oversee the Deep Ellum Public Improvement District (DEPID) and distribute the newly assessed public funds to enhance and support growth in the neighborhood. At the same time, the DEA became a 501(c)(4) organization. The DEA was intended to partner with the DEF and to be the beneficiary of PID funds to support and encourage growth within the neighborhood. As part of those improvement efforts, the bylaws of the DEF explicitly stated the organization’s purpose includes “supporting and encouraging growth” and “enhancing, protecting, preserving, and nurturing the art, music, and culture so rich in Deep Ellum’s past.” (Deep Ellum Foundation, Citation2001). The acknowledgment of the value of the arts to Deep Ellum as well as the intention to cultivate a creative community was thus established upon the outset and formalization of these organizations.

The Deep Ellum association, Deep Ellum foundation & Deep Ellum community association

While originally founded by property owners, by the early 2000s the DEA board consisted of residents, business owners, property owners, and other stakeholders in the Deep Ellum district. As the entity managing public funds in the form of property tax assessments, the majority of the DEF board was comprised of property owners. The two organizations met and operated independently to a degree but were always intertwined. For instance, DEF board members provided space free of charge to house the DEA’s office and host its meetings. The DEF Board President was also the President of the DEA for many years. Both organizations existed to improve the neighborhood and continued to emphasize arts and culture in the district. A 2007 open letter from the DEA states, “Deep Ellum is a bastion of music, art, culture and commerce and we embrace everything which promotes that end in healthy proportions” (Deep Ellum Foundation, Citation2007). A 2011 official document of the DEF similarly stated the organization existed to “serve, develop, protect, preserve, and enhance the community of Deep Ellum while nurturing the ongoing developments, art, music, culture, and commercial interests of our community” (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2011).

Despite their similar aims and overlap of members and resources, the two organizations did not always work together effectively. In 2008, the organizations fissured over the use of property tax assessment funds for the district (R.Wilonsky, Citation2007). The DEA was an all-volunteer body, whereas the DEF funded two staff members at the time. The former contended that the latter was not effectively or fairly distributing funds into the community if well over half of the funding was allocated to the two staff members’ pay. The two organizations briefly parted ways amidst the argument.

The Deep Ellum community association

The two entities ultimately reunited in 2009 after changes in leadership, an update to each organizations’ bylaws, and a rebranding of the DEA into the DECA. Citing their greater strength together than apart, the President of the DEF and board member at the time, Jon Hetzel, stated:

We just kind of made an informal pact that we were going to collectively push the two organizations forward and part of that was me making clear in the bylaws that DECA always had a position on our board and were going to be part of the team. That was contentious, I really pushed it through and went to bat for DECA and that further solidified their trust in me (J. Hetzel, personal communication, 29 July 2021).

The organizations took steps to clarify each organization’s role and responsibilities in relation to the other. They also intentionally restructured to require collaboration between the organizations. In their bylaws’ updates, the DEF and DECA explicitly reserve a seat on their boards for a representative of the other organization. This arrangement persists today as the President of the DECA has a standing seat on the DEF board and the DEF Executive Director serves on the DECA board.

According to the organization’s then president, Sean Fitzgerald, the DECA added the word “community” to its moniker for several reasons. First, the acronym DEA for an organization promoting an entertainment district seemed an odd choice as it risked DECA at the time agreed that a distinguishing feature of their organization was its focus upon people. Sean explained:

Everyone sees Deep Ellum through their own prism … And often you’d get these separations and not always a lot of empathy because you didn’t know people who were engaged in Deep Ellum in ways different than you were. So, my theory has always been do what we can to create micro-communities of people in Deep Ellum tied by their interest in something whether the urban garden or murals. Then find ways to mix them up in same bag and get connected mico-communities so we could end up stitching a more powerful Deep Ellum together. I thought it worked pretty good. People who were totally different sets of interest met very widely different people (S. Fitzgerald, personal communication, 27 July 2021).

Together with the DEF, the newly branded DECA thus reaffirmed the intentional cross-sector collaboration amongst neighborhood stakeholder groups. DECA also continued the earlier DEA’s commitment to the district’s arts and culture. The byline of the new DECA in a 2009 communication stated, “Deep Ellum Community Association operates to promote the art, business, history, music, and unique culture of Deep Ellum” (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2009).

Additional local organizations set deep roots in the arts

In addition to the DEA, DEF and DECA, several additional local organizations have shaped the Deep Ellum community, uplifted the arts as a core component of their missions, and intentionally partnered with other neighborhood organizations in Deep Ellum to advance the district as a whole. Life in Deep Ellum (LIDE), while first and foremost a place of worship, has also served as a community center and hub for creatives in Deep Ellum since 1999. After conducting a survey of the neighborhood in 2006 sponsored by nearby Baylor Scott & White Hospital, LIDE determined Deep Ellum’s four core strengths were art, music, commerce, and community (Life in Deep Ellum, Citationn.d.). It’s leaders then went about structuring LIDE and its space specifically to serve and further each of those strengths. The longtime co-pastor and DEF Board Member, Rachel Triska, stated, “In organizing around art, music, community, and commerce, we anchored ourselves in the best of Deep Ellum and believed we could help our community stay centered and grow from those roots” (R. Triska, personal communication, 29 July 2021). Deep Ellum Radio and Foundation 45 are additional local organization with ties to the DECA that daily promote Deep Ellum’s artists, culture, and community support.

The newest of the organizations created specifically to serve and support the creative community is Deep Ellum 100. Founded in 2020, it was established in response to the heightened needs of local artists, musicians, and service industry members put out of work by the COVID-19 pandemic as well as small businesses facing extreme declines in revenue and mounting debts (Deep Ellum 100, Citationn.d.). The organization’s founder is a former member of the DEF and former president of the DEA as well as a longstanding resident of the district. Deep Ellum 100 has been successful in raising tens of thousands of dollars to distribute small grants to four categories of recipients: artists, musicians, service industry workers, and small businesses.

Local businesses as centers of community engagement and perpetuation of the arts

Deep Ellum’s creative community has also been shaped incontrovertibly by the district’s local businesses. The district boasts over 400 businesses today. Some have been in operation for decades and a few for over a half century. Some longstanding business owners who previously worked in the district producing or booking shows as youths now own their own restaurants and music venues. Bars hang artwork from local partner galleries and provide stage space for smaller performances. Several music venues host more than a performance per day in a typical year while local art galleries and shops have hosted regular art walks. These are the places, stages, and gathering grounds that have impelled Deep Ellum’s arts the most as they have enabled countless unique and irreplicable experiences that live in the hearts and memories of local creatives and patrons as well as travelers.

While local organizations promote, coordinate and provide resources for artistic endeavors in the neighborhood, it is the music venues, theaters, art galleries, comedy clubs, publishing house and culinary arts that make Deep Ellum the living heartbeat of Dallas’ arts scene. The people behind these places and especially some of the longstanding entrepreneurs in the district have indelibly contributed to shaping Deep Ellum’s culture. The owner of local music venue, Three Links, and resident of Deep Ellum for over 20 years, Scott Beggs, described the current state of the neighborhood’s music scene thusly, “I think Deep Ellum still has that music community backbone. It is a little harder to find it sometimes but there’s a lot more people. That is what we are here for and hopefully we teach them when people come to our city” (S. Beggs, personal communication, 29 July 2021). Lauren O’Connor, the current Executive Director of Foundation 45 described why she got involved in the neighborhood and expressly cited Three Links, sharing, “I met so many good friends (in Deep Ellum). Family. Energy. You can go into Three Links and feel comfortable. People look out for you. I’m from Delaware and we don’t have that. It gives you a sense of belonging” (L. O’Connor, personal communication, 27 July 2021).

Art-forward collaborations, events, and public spaces in Deep Ellum

In the early 90ʹs, a nascent DEA, led by several of the major property owners, instigated and set in motion a series of arts events that would unleash a burst of artistic energy in the neighborhood and capture the imagination of artists for generations to come. These early efforts bringing together artists, producers, businesses, and property owners would lay the groundwork for the Deep Ellum Cultural District today. The idea was simple – get people down to Deep Ellum. The district was at the time experiencing significant vacancy and was rarely visited in daylight or on the weekdays. Deep Ellum’s calling card today, colorful murals, were a key feature of these early efforts.

2Likely the best-known collective effort of Deep Ellum’s local stakeholders to put art at the forefront of development and get people interested in the neighborhood was a mural project called TunnelVisions, curated by Frank Campagna, a resident and entrepreneur at the time who now owns Kettle Art Gallery. [ near here] The first TunnelVisions project took merely a weekend to execute after Frank lined up the several dozen mural artist participants and coordinated their work together. According to Frank, the DEA’s property owner members secured the necessary permissions from the City and provide the artists’ pay (F. Campagna, personal communication, 25 July 2021). It was an effective partnership with the respective parties’ each bringing their different skills and resources to bear.

The success of the project sparked several future significant mural projects not only led by the existing neighborhood organizations but also newly attracted stakeholders inspired by the early efforts (TunnelVisions, Citation2014). Building upon the success of the earlier mural projects and events, the DEF and DECA turned their efforts toward projects that would create semi-permanent public spaces to host artwork and for the community to gather including an art park, dog park, and community garden. Then President of the DEF, Barry Annino, stated, ‘Things are really picking up in Deep Ellum, and the Foundation sees art as a big part of that. Art has been and will be important to the neighborhood as it grows. ” (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2009). Cathryn Colcer, former DECA board member, summed up the contribution of such projects to the neighborhood, “To me, strong projects like the Deep Ellum Outdoor Market, the Urban Gardens, the dog parks and art projects like the Art Park, the Planter box project, and the Blues Alley are what keeps this neighborhood both unique to many other big city arts districts, but it also makes it accessible to the everyday city dweller” (C. Colcer, personal communication, 22 August 2021).

Together, these early mural projects, events, and public space-making efforts not only strengthened community bonds including across distinct stakeholder types but also solidified Deep Ellum’s brand as an artistic district and contributed to inculcating a highly unique creative ethos that endures in the community, attracts visitors and inspires new ventures and investments today.

Organizational strategic planning to advance arts & culture amidst economic growth

By the late 2010ʹs, Deep Ellum was on the precipice of tremendous and exponential growth (Deep Ellum Foundation, Citationn.d.). While some saw this as great progress and the fruits of many years of labor, others saw it as a major threat to the neighborhood’s culture and community. A few even regarded the district as lost. Recognizing this debate and turning point in Deep Ellum’s history, the DEF embarked upon a year of concerted outreach to the neighborhood’s range of stakeholders. Through the input gathered between 2018 and 2019, the DEF developed a strategic plan for the Deep Ellum Public Improvement District.

The aim of the Deep Ellum Public Improvement District Strategic Plan was to identify the greatest needs of the district at a pivotal moment of growth in order to chart a sustainable growth trajectory for Deep Ellum and guide the DEF’s work from 2019 to 2025 (Deep Ellum Foundation, 2019). A broad range of perspectives was intentionally sought out during the planning process. However, the input of those with a tangible investment in the district (i.e. property owners, business owners, and homeowners) and local organizational leaders contributed most to honing the priorities within the plan. These categories of stakeholders were provided multiple engagement opportunities from the outset to the end of the planning process. Standing meetings of the DEF board, DECA board, and Deep Ellum business community were utilized not only to gain initial insights but review overarching themes, once identified, and scrutinize a near final draft of the strategic plan.

The DEF learned that in addition to issues such as safety, preserving, leveraging, and continuously highlighting the key ingredients that made the Deep Ellum neighborhood special in the first place were of the utmost importance across stakeholder groups. Thus, one of the four pillars of the resulting strategic plan focuses upon nurturing these assets. The pillar promoting an, “authentic, unique, vibrant community and commercial destination,” was accompanied by three other pillars prioritizing safety, an inviting physical environment, and transportation accessibility.

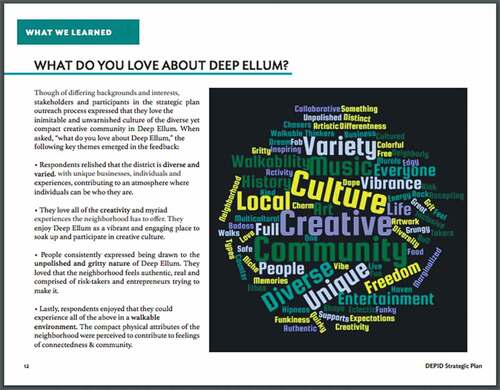

Figure 4. Deep Ellum public improvement district strategic plan outreach results indicating what stakeholders and visitors love about Deep Ellum.

Within the four pillars of the strategic plan over 30 objectives and over 100 specific action items were developed. The DEF’s Strategic Plan Task Force reflected the stakeholder composition of the community and was comprised of the DEF President and representative of a longtime property owner, a representative of a newer major property owner, a local partner organization leader, the former Executive Director of the DEF and a small business owner, resident, and representative of the DECA. The Task Force established tiers of prioritization for the over-100 action items.

While various individuals and stakeholder types preferred certain action items, objectives and pillars more than others, the plan on the whole represented the range of priorities of the community. Once a draft of the plan was crafted, the DEF intentionally returned to the business community, the DECA Board, and its own board as well as Strategic Plan Task Force to vet the draft document, essentially asking, “did we get it right?” The President of the DECA at the time, Jim Rogers, cited some concerns regarding the draft plan’s priorities. In particular, he believed there were omissions in specific action items and the degree of prioritization related to the stated need for mixed income housing and architectural preservation. In an ensuing meeting of DEF and DECA leaders, the draft plan was updated to better reflect not only the DECA’s housing goals but include several new action items and an objective. These included crafting architectural design standards and promoting the district as a lab of innovation. With property owners, residents, artists, and business owners all represented, not everyone around the table agreed precisely on the degree of importance of these items relative to others in the draft plan. In fact, some points of the discussion were sensitive as they related to and potentially impacted individuals’ vested interests in the neighborhood. That said, by coming together to discuss and debate the merits of the various priorities and related tasks within the plan in person, a compromise was achieved with the new action items and objective added to reflect priorities the DECA leaders felt the community voiced through the strategic planning process and cared strongly about.

Simply gathering organization leaders around the table once more and ensuring representation across the core stakeholder groups – property owners, business owners, residents, and artists – may have sufficed in achieving this outcome. More likely, however, the preexisting trust established between the stakeholders representing different organizations and viewpoints played a role in the successful compromise. Several individuals at the table had had prior opportunities to work out differences over the preceding years. In particular, the current President of the DEF and former President of the DECA, both present at that meeting, were the same two individuals credited with brokering the reengagement of the DEF and DECA after the earlier fissure. Through this history of collaboration, they established trust and mutual respect not only for one another but between the two bodies as well. Resultantly, the strategic plan was inclusive of the range of stakeholders’ top concerns despite pushing some boundaries of comfort for some of the stakeholders involved. The Deep Ellum case of cultural planning, in this way, provides a helpful example of how structural and functional factors can combine to encourage network success as outlined by Cristofoli et al. (Citation2017). The formalized mechanisms supporting collaboration in the strategic planning process combined with informal mechanisms including established trust between the leaders involved in the process resulted in an improved plan with greater support across the network of stakeholders in Deep Ellum (Cristofoli et al., Citation2017).

Strategic planning outcomes

After the DEF adopted the Deep Ellum Public Improvement District (DEPID) Strategic Plan in 2019, a Cultural Committee was formed to oversee the cultural sub-pillar of the plan. Each pillar of the adopted strategic plan is now supported by a designated Committee which reports to the DEF Board. Committees advise and guide DEF staff in advancing objectives and implementing identified action items. For instance, the Cultural Committee is tasked with the development of a proposed Dallas Cultural Trail connecting Deep Ellum to its sister neighborhoods, the Dallas Arts District and Fair Park. The Committee is comprised of Dallas arts institution leaders, local literary, arts, music, and community organization representatives, business owners, property owners, and residents who have robust experience in spearheading arts activations and reflect the diversity of cultural assets in the district. The DEF’s Executive Director and Marketing Manager assist this Committee and serve as liaisons to other partner entities including the Dallas Convention and Visitors Bureau, Office of Arts and Culture, Arts District, Fair Park First, State Fair of Texas, Latino Cultural Center and the DECA.

The DEPID Strategic Plan already laid out specific strategies to bolster local culture as well as market the district, and the Deep Ellum Cultural Plan drew directly from that guiding document. The cultural plan then refined and organized action items around four objectives specifically to promote Deep Ellum’s creativity, celebrate its history, enhance artists’ economic viability in the district, and build a robust cultural eco-system through rich partnerships.

The first big task of the DEF’s Cultural Committee was to apply for and achieve Cultural District status for Deep Ellum, as awarded by the State’s Texas Commission on the Arts. In that process, the committee developed a cultural plan for the district. By September of 2020, Deep Ellum was officially recognized as a Cultural District by the Texas Commission on the Arts. It was the second to be recognized in Dallas. While staff prepared the application and the DEF Board approved significant expenditures for required components such as a video submission, the content of the application was largely informed by the Cultural Committee and reflective of Deep Ellum’s cross-section of stakeholders. The Committee completed a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis, conducted limited research, and met several times to devise the Deep Ellum Cultural Plan.

The committee felt the Cultural Plan needed to be more explicit than the earlier strategic plan in devising and committing to efforts to get dollars into artists pockets. The Committee also envisioned and agreed upon a more expansive set of action items to uphold neighborhood history. Elucidating these priorities of the Committee, DEF Board member, former Life in Deep Ellum Co-Director and Cultural Committee member Rachel Triska stated:

Identity matters and in community development. Artists tell the story of a place. From Blind Lemmon Jefferson to Frank Campagna, artists have told the story of Deep Ellum for over a century and done it in ways that made sure the rest of the city listened … The narrative of Deep Ellum, in many ways, endured because the community kept telling its story and understanding itself in relationship to its past (R. Triska, personal communication, 29 July 2021).

Arguably, the most tangible outcome of the strategic and cultural planning of the last years in Deep Ellum is the new Deep Ellum Blues Alley mural project. Launched in 2021, the project has been years in the making. The initial concept for Blues Alley originated over a decade ago in 2011 when local mural artist, Dan Colcer, recognized a parallel between the current visual artists and the blues musicians of nearly a century earlier as each infused dynamism into the district and attracted visitors. Dan and his wife Cathryn, then-member of the DECA board shared these musings with then President of DECA, Sean Fitzgerald. Together, they envisioned a street completely awash in blue in Deep Ellum, painted with murals honoring the district’s blues history. The first phase of the mural project began in May of 2021 with 11 murals on the back of a brand-new office tower in Deep Ellum. The DEF was awarded over $100,000 by the Texas Commission on the Arts to expand and enhance Deep Ellum Blues Alley including through additional murals and dynamic lighting. While a worthy and inspiring idea in and of itself, Deep Ellum Blues Alley required significant coordination by the DEF between property owners, businesses and artists to come to life. It necessitated both the Colcers and Sean Fitzgerald remaining invested in the neighborhood for over more than a decade. It also required property owners’ financial commitment and continuous understanding of how the arts benefit their tenants and the district as a whole. Through several years of engagement and advocacy by the DEF, a critical mass of property owners and business owners agreed to participate in the project by hosting the artworks on their walls and funding a significant portion of the artists’ labor and materials fees. Without each of these elements, the project would not have been realized. Deep Ellum Blues Alley will serve as a cornerstone of the forthcoming the Dallas Cultural Trail, another major cultural initiative resultant of the DEPID Strategic Plan.

Discussion

The Deep Ellum case illustrates how an initially informal to increasingly structured network of local private and nonprofit organizations may successfully advance economic development infused with the arts (Turrini et al., Citation2010). The success of several early arts events of the 1990ʹs coordinated by a cross-section of stakeholders built trust (McGuire, Citation2006) and established a trust building loop (Turrini et al., Citation2010). A record of success, nascent trust, and the stability of the key stakeholders involved enabled the network to weather several significant disagreements between stakeholder groups and subsequent iterations in the structures of the partner organizations in the early 2000ʹs (McGuire, Citation2006). With more distinct and defined roles as well as new clarity upon and formalization of the relationship between key organizations, the network was then able to advance more permanent physical improvements to the neighborhood that showcased visual arts between the early 2000s and 2015. With the arts serving as a spark, Deep Ellum continued to gain momentum in its economic development even after the major economic recession of 2008. By the late 2010s, the stable partnership between local organizations and key stakeholder groups enabled significant cultural planning work to take place, further focusing joint efforts. This planning was aided by the emergence of one of the nonprofits, the DEF, as a form of central core agency coordinating across sister organizations and stakeholder groups. The benefits that this network integration rendered reinforces the findings of both McGuire and Turrini. Through the joint strategic and cultural planning efforts, the district was formally recognized by the State of Texas as one of its then-48 Cultural Districts and was awarded its first sizable grant to expand a major new mural project highlighting neighborhood Blues history.

The network continues to expand and strengthen and is now working on even more ambitious initiatives with additional organizational partners. These include to launch the first-ever Dallas Cultural Trail and to achieve recognition by the National Register of Historic Places. Once more, illustrating previous scholar’s findings, this trajectory of success was facilitated by a combination of a further integrated network structure and functional factors such as increasing trust (Cristofoli et al., Citation2017). Fundamentally, it was made possible by the longstanding commitment of Deep Ellum’s key stakeholders and enriched by their willingness to engage across sectors.

Inclusion of the diverse array of stakeholder types in the community has been a key to success, but also presents challenges. Relying upon differing types of stakeholders whose needs and wants for the neighborhood vary widely ensures there will be differences of opinion on what local organizations should do and prioritize. Similarly, the same benefits of engaging longtime stakeholders who have the institutional knowledge, relationships, and resources to advance initiatives also means local organizations contend with strong stakeholders who have the means to hinder if not cripple initiatives they do not agree with. Old grudges can sometimes stall progress even when stakeholders mostly agree on the desired ends in sight.

Contrasting views have, in several cases, caused angst, disagreement, and even impeded neighborhood progress. Control over certain initiatives, such as website content and oversight, positions on zoning code and related requirements, special use permits, and efforts to develop a diverse and inclusive community have tested the collaborative network. Disagreement is a common part of collaboration. Shared goals and trust within the network are essential to producing community benefit.

The context is essential to the process of creative placemaking. Deep Ellum has been called the soul of Dallas. Its rich history shapes the community’s creative ethos and has resulted in long-term commitments to the area. In addition, Deep Ellum benefits from its geographic location, proximity to transportation options as well as other arts and economic centers including the Dallas Arts District, Baylor Hospital Campus, downtown Dallas and Fair Park. Communities seeking to engage in creative placemaking must do so in light of their community character, stakeholders, and resources.

Several questions remain that may be explored by future research. These include:

How can the arts-driven development contribute to models of shared ownership in and economic benefit? How and can arts-based economic development efforts boost ownership by a broader diversity of stakeholders more representative of an area’s demographics and neighborhood’s historic roots? How can arts-based programming and community development initiatives help foster and solidify neighborhood identity? How can such initiatives create spaces for a wide range of people of different backgrounds, interests and means to coexist even whilst economic development continues? How can creative economic development efforts engage and include community members at every level beyond those with ownership stakes (e.g. renters, employees, and regular patrons) who may also feel bonds of commitment to a district?

Conclusion

As one of the longest standing stakeholders put it, “remember it’s the people. That is what Deep Ellum is all about.” Answering the question of why he is still involved in the DEF after so many years, Rich Cass explained,

Deep Ellum could have this awesome historic architecture and great music and food and art and all that stuff but there is one thing if it lacks it would cease to exist and that is the people. So, one of the things I learned being around someone like my father is the value of people” (R. Cass, personal communication, 19 August 2021).

While some of the significant risks associated with economic growth remain and difficulties within neighborhood collaborations persist, Deep Ellum has to this point successfully infused the arts into the area’s development thanks, in large part, to the longstanding commitment of a range of stakeholders representing critical different interests in the neighborhood.

The organizations built over the years by Deep Ellum’s stakeholders have been fortified through their trials and tribulations working with one another. With the passion, resources and insights invested in them, Deep Ellum’s local organizations have been able to advance the district’s cultural impact. With intentionality, continued commitment from that range of district stakeholders and agility as well as a bit of Deep Ellum’s characteristic ingenuity, they must now tackle the next generation of challenges brought on by economic success. The current President of the DECA, Breonny Lee, describes Deep Ellum’s predicament thusly:

It is going to take multiple groups focusing efforts to preserve the culture that we have, to recreate art spaces, to provide opportunity where it has been shut down or we are really in danger of losing what makes Deep Ellum, Deep Ellum … So, I see DECA’s role as more critical than ever (B. Lee, personal communication, 25 July 2021).

Deep Ellum is one of the few places in Dallas and nationwide where diversity of thought, race, ethnicity, gender, occupation, esthetic and age are embraced and welcomed by locals and visitors throughout the week. Retaining this special balance will be a tall order and one well worth fighting for.

Geospatial location

32.784190, −96.782147

Acknowledgments

There are many individuals whose insights and actions have contributed to this article.

Micah Bires’, then Marketing Manager for the DEF, research on the history of the neighborhood informed the Deep Ellum history section of this paper especially.

Several longtime stakeholders and contributors to Deep Ellum, including property owners, business owners, residents and artists took the time to interview with me for this article. They include: Scott Beggs, Frank Campagna, Rich Cass, Cathryn Colcer, Anthony Delbano, Sean Fitzgerald, Jon Hetzel, Denny Hunt, Breonny Lee, Stephen Millard, Lauren O’Connor, Scott Rohrman, and Rachel Triska.

Additional insights from community members including former President of the DEA, Gianna Madrini, and former President of the DECA, Jim Rogers, have been critical to my understanding of Deep Ellum, its organizational and artistic development.

The time, commitment and insights of current and recent members of the DEF Board, DECA board, Life in Deep Ellum and Foundation 45 leadership teams also shaped this article.

Finally, my husband and son spared the time and gave me the space to try to tell this story in the best way I was able to and I am grateful.

Disclosure Statement

The author of this paper has no known competing interest or personal relationship that interfered with this paper’s statements or research. The author is the Executive Director of the DEF and, therefore, paid staff of that organization. The opinions and argument presented are informed by her professional experience serving the district and are her own.

References

- (2020) AMENDED AND RESTATED BYLAWS OF THE DEEP ELLUM COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION, A TEXAS NONPROFIT CORPORATION. Deep Ellum Community Association, Dallas, Texas, US.

- Americans for the Arts. (2017). Arts & economic prosperity 5. http://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/aep5/PDF_Files/ARTS_AEPsummary_loRes.pdf

- Bylaws of the Deep Ellum Foundation. (2001). Deep Ellum foundation. Dallas.

- Chamber, D. R. (n.d.) Dallas-Fort worth region facts. Fact sheets. https://www.dallaschamber.org/why-dallas/dfw-facts/#facts-sheets

- Cristofoli, D., Meneguzzo, M., & Riccucci, N. (2017). Collaborative administration: The management of successful networks (pp. 275–283). Public Management Review.

- Deep Ellum 100 (n.d.) Together we’ve provided eight grants and raised $30,000 to support the small businesses, workers, artists and musicians that keep Deep Ellum thriving. https://www.deepellum100.com/

- Deep Ellum Association. (2007, November 7). Open Letter from the Deep Ellum Association. Deep Ellum foundation. US.

- Deep Ellum Community Association. (2018). DECA-DEF memorandum of understanding. Deep Ellum foundation. US.

- Deep Ellum Foundation. (2008, March 31). Deep Ellum creates a new mural district. Deep Ellum foundation. Dallas, Texas.

- Deep Ellum Foundation. (2020, July 1). Deep Ellum development deck. Deep Ellum foundation. US.

- (2021, January 12) Deep Ellum Foundation Metrics. Deep Ellum Foundation, Dallas, Texas, US.

- Deep Ellum Foundation (n.d.) Deep Ellum Public improvement district strategic plan. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c5c53a6b2cf79e57c2a3164/t/5e543f2bab3ef425af84ae54/1582579508771/DEF+Strategic+Plan+with+Links-compressed.pdf

- Freedman, P. (2011, October 13) An oral history of the dallas music scene. Dallas Observer. https://www.dallasobserver.com/music/an-oral-history-of-the-dallas-music-scene-6425952

- Govenar, A., & Brakefield, J. (2013). Deep Ellum: the other side of dallas. A&M University Press. https://books.google.com/books/about/Deep_Ellum.html?id=aV8jAQAAQBAJ&source=kp_book_description

- Life in Deep Ellum (n.d.) Who we are. faith fuels everything that falls under the LIDE umbrella. https://www.lifeindeepellum.com/about-lide/

- McCarthy, K., Ondaatje, E. H., Zakaras, L., & Brooks, A. C. (2004). Gifts of the muse. RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2005/RAND_MG218.pdf

- McGuire, M. (2006). Collaborative public management: assessing what we know and how we know it. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00664.x

- Texas Economic Development Corporation (2021, January 27) News. Texas enters 2021 as world’s 9th largest economy by GDP. https://businessintexas.com/texas-enters-2021-as-worlds-9th-largest-economy-by-gdp/#:~:text=Since%202015%2C%20Texas%20has%20been,from%20the%20International%20Monetary%20Fund

- TunnelVisions 2014 (2014, April 4) https://www.facebook.com/events/1476632529219339/

- Turrini, A., Cristofoli, F., Frosini, F., & Nasi, G. (2010). Networking literature about determinants of network effectiveness. Public Administration, 88(2), 528–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01791.x

- Wilonsky, R. (2007, February 20) A PID-dly little squabble in Deep Ellum. The Dallas Observer. https://www.dallasobserver.com/news/a-pid-dly-little-squabble-in-deep-ellum-7104402