ABSTRACT

A growing number of information and communication technologies (ICTs) are being used worldwide to support participatory budgeting, a process that allows citizens to decide how to spend part of the public budget. Nevertheless, the effects of ICTs on political inclusion in participatory budgeting processes remain underexplored in the literature. This paper aims at contributing to the cited scholarship. The research takes the form of a qualitative case study of the participatory budgeting process in Medellín, Colombia’s second-biggest city, from its launch as a city-wide policy in 2004, until its last regulatory change in 2017. The article analyzes the influence of the use of ICTs in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process on political inclusion in the view of the process participants. The qualitative data collected suggests that ICTs can change the power dynamics in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process; nevertheless, their use has mixed results, depending on how they are designed and implemented.

Introduction

The scholarship on the political inclusion of marginalized populations in a broad range of contexts and fields is growing rapidly. A specific subject that is receiving increased attention is participatory budgeting, a process that allows citizens to decide how to spend part of the local government budget. Still, the studies that examine the influence of participatory budgeting processes assisted by online tools on political inclusion remain scarce. This paper aims at contributing to the literature by analyzing how the use of online tools influence political inclusion in the participatory budgeting process of Medellín, Colombia’s second-biggest city, in the view of the process’ participants. The answer to this question is useful to guide the design and implementation of digital tools in participatory budgeting processes aimed at nurturing political inclusion.

The methodological approach of this research takes the form of a case study of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process from 2004 to 2017. The article uses a grounded theory approach to analyze the influence of the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process on political inclusion in the view of the process participants. When the research started, Medellín’s participants were discussing how to strategically incorporate ICTs into the participatory budgeting process. Hence, the study also involved the design and pilot trial of a technological tool for Medellín’s participatory budgeting process with the citizens and public servants of Medellín, using a participatory design thinking approach. This provided original data for understanding the benefits and challenges of the existing participatory offline process to foster political inclusion, and the role that ICTs could play in it.

The qualitative data collected for this research suggests that ICTs can change the power dynamics in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process that affect the political inclusion of its participants. Nevertheless, their use has mixed results, leading to both inclusion and exclusion. Therefore, I claim that ICTs could lead to political inclusion or exclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, depending on how they are designed and implemented. If their design and implementation allow for the process to be more transparent and to encourage open competition between the different actors, ICTs may favor inclusion. On the contrary, if their design and implementation are opaque and allows for capture by specific participants to take place, they may encourage result in exclusion.

After this brief introduction, the remaining part of the chapter is set out in five sections. In Section One I summarize the literature that conceptually frames this research. Against this literature backdrop, Section Two presents the methodology used herein, describing the research design and the methods of data collection and analysis. Subsequently, Section Three briefly describes Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. In turn, Section Four presents the findings of the research. Lastly, in Section Five, I draw out the policy implications of the findings, discuss the limits of the research, and suggest new studies that may emerge from my results.

The influence of participatory budgeting on political inclusion: A tale of two cities

The participatory democracy literature commonly features a tension, in which both a promise of political inclusion and a threat of exclusion can be found in participatory mechanisms (Koch & Sanchez, Citation2017; Palacios, Citation2016; Pearce, Citation2010; Zaremberg & Welp, Citation2020). In Latin America, this inclusionary-exclusionary tension is characterized by the enactment of a broad range of institutions and policies to include citizens in policymaking since the 1990s, coupled by a gap between participatory reforms on paper and in practice (Goldfrank, Citation2020; Kapiszewski et al., Citation2021). The scholarship features diverse frameworks that analyze the conditions needed for participatory democracy to be inclusive, such as Arnstein’s (Citation1969) “ladder of citizen participation” and Fung’s (Citation2006) “democracy cube.”

As McNulty (Citation2015, 1429) notes, despite the growing literature on participatory budgeting, “we still know very little about how inclusive these processes actually are.” Both international, national, and local scholarship show mixed results regarding the influence of participatory budgeting on political inclusion in different contexts (among others, Boulding & Wampler, Citation2010; Goldfrank & Schneider, Citation2006; Gómez, Citation2007; Souza, Citation2001; Velásquez & González, Citation2003).Footnote1 While some studies find a nurturing influence, others conclude the opposite. This is the case, not only with offline participatory budgeting, but also with processes assisted with ICTs and games (Cunha et al., Citation2011; Lerner, Citation2014; Secchi, Citation2017; Spada et al., Citation2015; Touchton et al., Citation2019; Wampler et al., Citation2018).

Explanations of the successes and failures of participatory budgeting processes

The literature attributes the different outcomes of participatory budgeting processes to a diverse set of circumstances, some of them associated with political conditions, such as the will of the elected authorities to carry out the process, and others related to considerations of public management, such as the capacity to execute the projects selected (Goldfrank, Citation2007; Wampler et al., Citation2018). Overall, the scholarship concludes that the diverse possible positive and negative effects of offline, online, and gamified participatory budgeting processes may both trigger political inclusion and exclusion, depending on the local context and how the processes and their components are designed and implemented.

For instance, Goldfrank (Citation2007) warns that participatory budgeting is not a neutral technical mechanism; its success depends on factors such as the political will of executive and legislative powers, and the institutionalization of the parties in opposition to the process. More recently, while analyzing the rise of participatory institutions in Latin America, Goldfrank (Citation2021, p. 128) highlights “the importance of both leftist political projects and international actors in the creation, diffusion, and implementation of participatory institutions,” while emphasizing “that, even when participatory institutions make the leap from parchment to practice, and even when they seem ideally suited to maximize inclusion, how they are designed and implemented by those fearful of losing power can inhibit the effective practice of citizenship.”

In turn, Wampler et al. (Citation2018, p. 6) conclude that some of the factors that may explain variations in the outcomes of participatory budgeting processes are the government’s ideology, civil society mobilization, the government’s electoral incentives, State capacity, the level of local resources, and institutional rules. Overall, the cited authors identify “three general areas of consensus in terms of when PB has its greatest, most beneficial impact: when it has strong government support, available resources, and where an organized civil society exists” (Wampler et al., Citation2018, p. 22). In a further work, Wampler et al. (Citation2021, p. 11) “develop an analytical framework that shows how program design and conditions at the macro- and meso- level strongly influence the outcomes that PB programs generate.” The framework, presented as a theory of change that describes potential social and political outcomes associated with participatory budgeting, depicts how variation occurs at the individual level – for instance, among citizen participants, civil servants, and elected officials–, to then portray that change also may occur at the community-level in the areas of accountability, civil society, and well-being.

For the specific case of Medellín, Urán (Citation2009, p. 192) argues that the political will of the Town Hall, combined with a robust social movement that preceded the creation of the participatory budgeting process and a flexible institutional design discussed with the participants but grounded in legal foundations, has assured the transforming potential of the process throughout the years, despite its challenges. In short, if not well-designed and carefully implemented, participatory budgeting processes can “reinforce power dynamics instead of challenging them” (Nazneen & Cole, Citation2018, p. 41).

Innovation within democratic innovation: Using information and communication technologies and games in participatory budgeting processes

Participatory budgeting is often labeled as a “democratic innovation” (Coleman & Sampaio, Citation2017; Lüchmann, Citation2017; Roecke, Citation2009); i.e. an institution “specifically designed to increase and deepen citizen participation in the political decision-making process” (Smith, Citation2009, p. 1). According to Smith (Citation2009, p. 1), democratic innovations are “innovative” because they depart from traditional institutional architectures of competitive elections in democratic processes. In the past fifteen years, traditional deliberation and voting procedures within participatory budgeting processes worldwide have also featured innovative tools within their proceedings, such as online voting platforms and games (Matheus et al., Citation2010; Sampaio & Peixoto, Citation2014).

The practice of using ICTs in democratic processes, such as participatory budgeting, is commonly known as electronic democracy or eDemocracy (Peixoto, Citation2009, p. 2). This strand of the literature has examined the effects of digital tools in participatory budgeting processes in countries such as Argentina (Matheus et al., Citation2010), Brazil (Barros & Sampaio, Citation2016), Germany (Pieper & Pieper, Citation2015), Italy (Stortone & De Cindio, Citation2015), and the United States (Smith, Citation2015). However, this area is still at a developing phase (Matheus & Ribeiro, Citation2009). Hence, despite the increasing use of ICTs in participatory budgeting processes, “to date these technologies have not been fully utilized or understood” (Wampler et al., Citation2018, p. 31).

At its origins, the literature in this area enquired about the potential of technological tools to enhance democratic processes. However, as Sintomer and Herzberg (Citation2013, pp.12–13) stress, using digital tools in participatory budgeting processes takes a broad range of forms, such as supporting the collection of proposals, informing, engaging, and mobilizing citizens, assisting the discussion and interaction among citizens, and enabling online voting, monitoring, and overview of the participatory budget development. Therefore, Sampaio and Peixoto (Citation2014, pp. 413–414) suggest that a more relevant question is how different designs of online tools and various forms of use and ownership interact in diverse contexts toward a final result.

The digital tools used in participatory budgeting processes take various forms, ranging from social media accounts and webpages informing about the process, to web-based platforms to collect ideas and applications for online voting (Democratic Society, Citation2016; Parra et al., Citation2017). The use of this assortment of tools in participatory budgeting processes can have different results, posing both strengths and challenges (Allegretti, Citation2012; Cunha et al., Citation2011). For instance, while Sampaio et al. (Citation2011, p. 1) conclude that “the internet can effectively provide environments to enhance a qualified discursive exchange,” Lim and Oh (Citation2016, p. 676) assert that “offline participation channels are more effective than online channels because of their high levels of representativeness and deliberativeness.”

The specialized literature often notes as positive effects of technology use in participatory budgeting processes that they may increase the information and participation for citizens (Matheus et al., Citation2010), and could reduce participation costs, while providing the public sector with valuable aggregated and cost-effective information about the participants’ preferences (Wampler et al., Citation2018). In contrast, the most common challenge is the inclusion of some populations in the process at the expense of others that may not necessarily participate online due to barriers of access, in a phenomenon called the digital divide; i.e. the difference in access, information, and understanding of digital tools between the haves and the have-nots, especially in rural and poor areas (Aguirre, Citation2014; Democratic Society, Citation2016; Matheus et al., Citation2010; Wampler et al., Citation2018). Still, Touchton et al. (Citation2019, p. 156) argue that,

scholars and practitioners lack evidence surrounding these hybrid innovations’ impact. This gap undermines democratic theory and policy because we simply do not know the extent to which some democratic combinations may generate desirable outcomes, or privilege certain outcomes over others.

Nevertheless, Wampler et al. (Citation2021, p. 77) hypothesize that digital participatory budgeting processes “would generate some changes in accountability, but we do not expect to see many meaningful changes in civil society or well-being.”

There is a growing interest in Colombia on the use of online tools to support participatory budgeting processes. However, the scant national literature about this topic usually examines it from a normative perspective, discussing the potential positive and negative effects of adding technological components to offline participatory budgeting processes. For instance, Ángel (Citation2015, p. 21), Viva La Ciudadanía (Citation2016, p. 31) and Guarín et al. (Citation2017, p. 21) highlight that digital tools could incentivize citizen participation, but warn about some limits, such as the need of institutional transformation to provide an adequate response to citizens’ participation through online tools, and a high digital divide that might hinder access to part of the population. Likewise, Viva la Ciudadanía (Citation2016, p. 31) suggests using ICTs in diverse stages of local participatory budgeting processes in Colombia, to foster their transparency, interaction, and visibility.

Per the case of Medellín, in a documental review of policy documents, webpages, and local regulation of the participatory budgeting process, Cabezas (Citation2019) concludes that the Town Hall of Medellín created new digital channels for citizen oversight that allow for stricter control of resource spending. Yet, assessing the 2017 change of regulation of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, Montes (Citation2020, p. 14) finds “mixed views on the use of tech tools in the process.” Although there are participants who see technology as an ally to attract new audiences, others consider that technology is turning citizen participation into an impersonal exercise that does not allow social encounters, whilst there is mistrust regarding the legitimacy of electronic voting.

In sum, as Touchton et al. (Citation2019, p. 156) note, “there is no consensus on the value of e-participation for deepening democracy.” Cunha et al. (Citation2011, p. 155) noted that, in these cases, the “challenges posed by the introduction of new technologies directed toward expanding the formal spaces of political intervention” may be added to already complex and challenging offline processes, augmenting their tensions. Nevertheless, the potential positive effects could also help reduce some of the existing offline conflicts. This should be analyzed on a case-by-case basis, examining, amongst other factors, the context, goal, and participants (Sampaio & Peixoto, Citation2014, p. 424). I adopt this approach in this paper. However, in line with Peixoto (Citation2009, p. 6) and Sampaio and Peixoto (Citation2014, p. 420), I am aware of the artificial differentiation and false dilemma of contrasting online and offline participatory budgeting processes. Per the case of Medellín, the participatory budgeting process is not either “online” or “offline:” It is a hybrid process with both analog and digital elements.

In sum, the diverse possible positive and negative effects of offline and online participatory budgeting processes may trigger political inclusion and exclusion of marginalized populations, depending on how the processes and their components are designed and implemented. To the best of my knowledge, none of the existing literature discusses the influence of digital tools on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. This paper aims to contribute to filling this gap.

Methodology

This paper aims to contribute to the relevant scholarship by using an exploratory approach based on a qualitative case study research design, that critically examines the case of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process from 2004 until 2017. Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) grounded theory approach was used to collect and analyze the data. This section briefly explains the research design and methods and includes definitions for main concepts used in this paper.

Research design and data analysis

The methodological approach of this research takes the form of a case study of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process from 2004 to 2017. Medellín is divided into sixteen comunas, which are urban territories of municipalities in Colombia, and five corregimientos, which are the rural equivalents to the comunas. I use the word localities as the plural word to refer to both comunas and corregimientos. In the examination of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process that I carry out in this paper, I use interchangeably “national” to refer to Colombia, and “local” to refer to Medellín. Furthermore, my study focuses in Medellín’s city-wide participatory budgeting process, which includes both its sixteen comunas and five corregimientos.

Instead of testing pre-specified hypotheses, in this paper I used Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) grounded theory approach to analyze the data and identify the processes that may or may not associate participatory budgeting with political inclusion in the view of its participants. Grounded theory is especially “useful in new, applied areas where there is a lack of theory and concepts to describe and explain what is going on” (Robson & McCartan, Citation2016, p. 79). According to Denscombe (Citation2010, p. 108), in grounded theory, “concepts and theories are developed out of the data through a persistent process of comparing the ideas with existing data, and improving the emerging concepts and theories by checking them against new data collected specifically for the purpose.”

The aim of grounded theory is to produce a middle-range theory of a phenomenon, in this case participatory budgeting, derived directly from data collected in a real-world setting (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). In grounded theory, data collection, data analysis, and theory development are interspersed throughout the study (Robson & McCartan, Citation2016, p. 79). My research follows this method by using an exploratory approach that employs a qualitative case-study design based on realism as an epistemological standing. In contrast to a positivist perspective, realism “is concerned with how mechanisms produce events” (Robson & McCartan, Citation2016, p. 31).

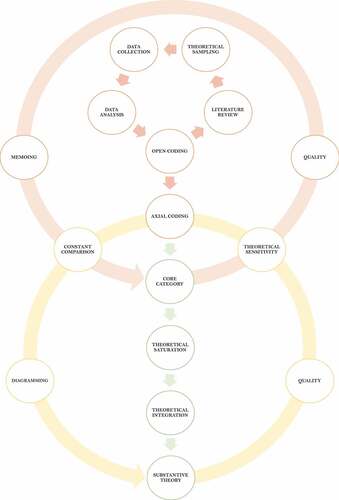

Amongst the different approaches to grounded theory (Kelle, Citation2010; Urquhart, Citation2012), I followed Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) method, because it offers systematic and clear steps for data collection and analysis, suitable for an exploratory research, while providing rigorous conditions to assess the quality of the research throughout the process. More specifically, in Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) approach, data collection and analysis follow an iterative process that integrates the following stages cyclically: theoretical sampling, coding, constant comparison, core categories, theoretical saturation, theoretical integration, and substantive theory. Likewise, this approach is enriched with the use of tools such as memoing, diagramming, and theoretical sensitivity, along with strategies to enhance the quality of the research, as depicted in .

Figure 1. Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation2015) grounded theory approach.

As Corbin and Strauss (Citation2015, pp. 35–36) put it, in grounded theory “the researcher does not begin the research with a pre-identified list of concepts. Concepts are derived from data during analysis.” This analysis begins with the collection of the first pieces of data and, subsequently, the analysis of this data guides the collection of further data using theoretical sampling, until the researcher constructs a well-integrated and dense theory up to the point of theoretical saturation.

In this research, once I started gathering data, I used open coding to start building concepts out of it, employing constant comparison as a tool to contrast the emerging blocks of analysis, which helped me to direct the research gathering more data using theoretical sampling, moving from open to axial coding until I reached the point of theoretical saturation. This was an iterative and non-linear process that lasted two years. Once I finished this stage, I carried out a thorough literature review, which I subsequently contrasted with my emerging theory. This paper captures both the process of creating my substantive theory, the literature review, and the critical analysis that I carried out after contrasting the substantive theory and the literature review.Footnote2

I employed qualitative empirical methods to gather data about the experiences of different actors involved in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, such as social leaders, national and local public servants, members of civil society organizations and citizens. These actors are the participants referred to in this paper’s research question as stated in the introductory section, i.e. what is the influence of online tools on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process in the view of its participants?

The unit of analysis of my research is focused on an understanding of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process during the period studied herein as a space of encounter and dispute. In this space, people from diverse backgrounds and with different perspectives are brought together to discuss local issues, both to build consensus or confront each other’s views. The unit of analysis focuses on places, physical and digital, that acted as spaces of encounter and dispute in the design of the local regulation and implementation of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, from 2004 until 2017, since they were the ones where political inclusion, or exclusion, was more likely to take place during the period of my case study. I analyzed mainly four spaces during the period studied herein. First, meetings of Medellín’s urban and rural planning councils and assemblies of the participatory budgeting process. Second, discussions at the City Council and Town Hall of the regulation of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. Third, the participatory budgeting voting process. Lastly, the design and employment of digital tools in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. This view of my unit of analysis as the spaces of encounter and dispute adheres to Pearce (Citation2010, p. 34), who claims that “Participation is not just about democracy. It is also about how we relate to each other in all our spaces of encounter.”

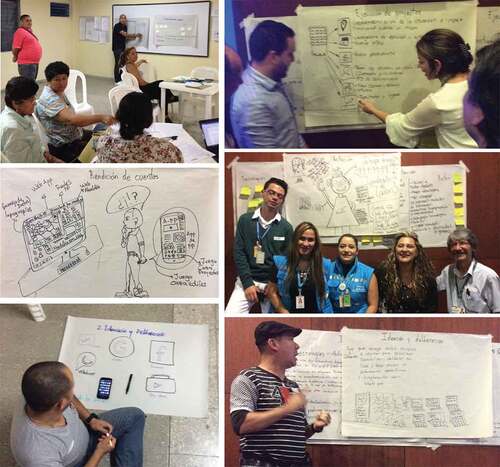

The qualitative empirical data to study the described unit of analysis at a city-wide level was collected through 70 semi-structured interviews, 7 focus groups, 80 participant observation exercises, and the examination of legal and policy documents, including laws, decrees, judgments, and official reports about the participatory budgeting process. The fieldwork was mostly conducted during July, August, and November of 2016 and February, March, May, June, July, November, and December of 2017. When my research started, participants in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process were discussing how to strategically incorporate ICTs into the process. Hence, the study also involved the design and pilot trial of a technological tool for Medellín’s participatory budgeting process with the citizens and public servants of Medellín. This provided data for understanding the benefits and challenges of the existing participatory offline process to foster political inclusion, and the role that ICTs could play in an online version of participatory budgeting.Footnote3

Main concepts used in the paper

Political inclusion emerged during my data analysis as pivotal in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. I clarify its sense in the methodological section to delimit its meaning throughout the paper. I created this definition using Corbin and Strauss’s (Citation2015) grounded theory approach. Hence, the definition of political inclusion used in this paper is grounded on the data analyzed, and pertains to an experience of participation that gives the possibility to all citizens, especially those who are marginalized, to collaborate with and have an effect on public governance decisions regarding the participatory budget. Several participants in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process shed light on the notion of political inclusion in Medellín’s context. Among these are social leaders (Daza, Citation2017; Marmolejo, Citation2017; Mejía, Citation2017), members of the City Council (Echeverri, Citation2017a; Múnera, Citation2017a), public officials of Medellín’s Town Hall (Aguirre, Citation2017b; Bedoya, Citation2017; Montoya, Citation2017b), and academics (Franco, Citation2017; Rodríguez, Citation2017b; Urán, Citation2017b). To name one example, a social leader of the Comuna One, asserted in an interview (Interviewee 4, Citation2017):

There are many types of peace and many types of violence. Medellín has an invisible violence fostered by social inequality. The best way to solve it is for people to participate. For instance, at the Comuna One people do not believe in the State and there is social segregation. Participation is one of the best tools to close social gaps.

This view of political inclusion is closely aligned with an understanding of participation as exercise of political power. This perception was often expressed by participants of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process in the data collected for this research (García, Citation2017a; Lopera, Citation2017b; Álvarez, Citation2017); in the words of Luis Fernando Lopera (Citation2017a), a social leader, “real participation is for us, as citizens, to have a real access to power.” In turn, political exclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process used in this paper juxtaposes inclusion, being defined as a withholding of an experience of participation that would have given a citizen the possibility to collaborate with and have an effect on public governance decisions regarding the participatory budget. I understand power in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process as pertaining to Weber’s (Citation1978) definition, namely, as the ability to decide and produce effects, in this case over how resources are spent, even if there is opposition.

The concept of political exclusion is aligned with a recurrent perception voiced by participants of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process during the course of my research, categorized in this study as “symbolic participation” (Arango, Citation2017; Palacio, Citation2017; Rojas, Citation2017; Saldana, Citation2017). This perception is described, for instance, in the words of City Councillor Luz María Múnera (Citation2017f) as a situation where “you participate and I participate but they decide”. shows a graffiti in a wall of a public university in Medellín, that displays the core of political inclusion as opposed to a symbolic participation. The graffiti reads: “We don’t want the administration to control our participation.”

Figure 2. Graffiti opposing a controlled participation, written at the University of Antioquia in Medellín.

Untangling the links between participatory budgeting and political inclusion in Medellín ultimately involves interdisciplinary analysis, drawing on disciplines such as legal studies, sociology, and political sciences, and long-term qualitative and quantitative research, with careful consideration of alternative explanations. Consequently, I am aware that the methodological approach of this paper and the framework proposed have several limitations. Nevertheless, I hope that the empirical findings and arguments proposed herein, serve as initial steps for charting key relationships between Medellín’s participatory budgeting and political inclusion, which can be further tested, for instance through quantitative data both in Medellín’s and other contexts.

Context, origins, and design of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process

Over the past two decades, Medellín has had an outstanding transformation, from being one of the most violent and unequal cities in the world, to being recognized for its “innovative city planning, design and development” (Corburn et al., Citation2020, p. 13), often categorized as an “urban miracle” (Humphrey & Valverde, Citation2017). Participatory budgeting was one of the main policies enacted in Medellín in the early 2000’s to transform the city (Urán, Citation2009). In fact, fostering political inclusion through participatory planning and budgeting processes has been a strategy to prevent violence triggered by political exclusion, used by governmental authorities in Medellín since the early 1990s (Foronda, Citation2009; Giraldo et al., Citation2010). However, Medellín’s participatory budgeting process has had conflicting findings in relation to political inclusion. Amongst others, these results can be explained by broader patterns of violence in the city that have not been oblivious to the participatory budgeting process, as I explain in this section.

Political exclusion as part of the invisible frontiers of Medellín’s conflict

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Medellín has been increasingly inhabited by industrial traders, merchants, and peasants migrating from rural areas of Colombia to find jobs. Likewise, it has been the recipient of several waves of internally displaced populations from neighboring municipalities affected by violence (Fierst, Citation2013; Tubb, Citation2013). These victimizations have led some such groups into a more profound exclusion, given that they arrived in Medellín in a situation of forced displacement, with many of their fundamental rights being neglected (Echeverría, Citation2004).

The conflict in Medellín has fluctuated in intensity. Violence often deepens in the presence of waves of armed groups fighting over the control of certain territories and activities. In these areas, the distinctions between peace and conflict, legality and illegality are blurred; a phenomenon known as invisible frontiers (González et al., Citation2015; Suárez-Gómez et al., Citation2018; Ruíz & Vélez, Citation2004). An area might seem peaceful and uneventful at first sight, when in reality it is highly disputed by several criminal groups recognizable by local inhabitants. Since the eighties, within these hidden borders, Medellín has been the stage of battles between many illegal groups, with disputes relating to drug dealing, guerrilla fighting, paramilitary control, criminality, and self-defense (Martin, Citation2014; Patiño et al., Citation2015).

A structural cause at the roots of Medellín’s conflict is the political exclusion of a broad range of populations – such as minority groups and communist-oriented political parties– often combined with the killing of political and social leaders (Duncan, Citation2015; Moncayo, Citation2015; Pizarro, Citation2015). This can be added to other triggers of violence, such as inequality in land distribution (Giraldo, Citation2015; Gutiérrez, Citation2015; Molano, Citation2015), clientelism and corruption (Gutiérrez, Citation2015), illegal drug dealing (Duncan, Citation2015; Molano, Citation2015; Pécaut, Citation2015), extortion and kidnapping (Duncan, Citation2015; Gutiérrez, Citation2015), and disputes over the control of legal and illegal markets such as of gold and cocaine (Rettberg et al., Citation2018). In the view of Duncan (Citation2015, p. 248), in the sixties, political exclusion was added to existing economic exclusion in Colombia to justify violence, given that it was seen by some as “the only alternative to demand social change due to the restrictions to democracy created by the National Front.”Footnote4

Political exclusion has been not only a cause of violence, but also a consequence, given that many crimes have been committed against civic leaders to gain control over the population. For instance, de Zubiría (Citation2015) contends that the conflict has created a process of collective victimization among participatory movements and political projects. According to Gutiérrez (Citation2015), this impact has, in turn, weakened the legitimacy of law and increased the transactional economic costs of participation. More recently, Gutiérrez (Citation2019) contended that the relationship of armed groups with the military forces in Colombia created negative impacts on democracy that are still present today; amongst them, a loss of capacity of social organizations and political movements, and a legitimization of violence against political and social leaders with the excuse that they belong to illegal armed groups.

Participatory budgeting as a strategy for political inclusion in a continuing conflict

Participatory mechanisms aimed at nurturing political inclusion have been implemented in Medellín since the early 1990s; this constitutes a strategy of resistance against the control exercised by illegal armed groups. Participatory budgeting is one of them. For instance, in 1996 the City Council issued the System of Municipal Planning of Medellín, which allowed citizens to create their own development plans, called zonal plans, for their comunas or corregimientos. Moreover, the citizens were allowed to seek resources to help them implement the projects in the zonal plans. These plans were part of a broader development agenda of various actors on the ground, who mobilized to participate in the decision-making processes of their comunas and corregimientos through them. Participatory budgeting was later added to the plans, so citizens could directly decide investment priorities based on the development programs they designed for each locality. In the words of Medellín’s Municipal Development Plan of 2012,

The development plans of the comunas and corregimientos have their origins in the participatory processes that mobilized in Medellín during the 90s. In 2004 the administration gave them a new force while implementing the participatory budget. These participatory planning processes were revitalised then as a political gamble of social leaders and community organizations, who have built their own local development agendas through participation (Concejo de Medellín, Citation2012, p. 442).

According to Urán, (Citation2017a), an expert in citizen participation, during a public hearing about Medellín’s participatory budgeting process,

Democracy and violence are in a confrontation in Medellín. In fact, participatory planning in this city was born to defy violence and tackle the gangs that controlled poor neighbourhoods at that time in the city. The zonal plans were at some point named ‘peacebuilding plans,’ because they allowed people to sit and dialogue about what they wanted for the city. People discussed what was happening with the gangs and that gave some space to resolve some issues.

Hence, by 2004, when the period of the case study of this research started, the Town Hall of Medellín introduced participatory budgeting as a city-wide policy, to continue the process of political inclusion using participatory mechanisms (Concejo de Medellín, Citation2004). Participatory budgeting was institutionalized as a city-level policy in Medellín’s development plan of 2004–2007. In the Town Hall’s diagnostic to back the implementation of participatory budgeting, the development plan declared that Medellín was having a crisis of governance, with high levels of poverty, increased inequality, an obsolete economic and social structure, and a deficient integration with the rest of the country and world.

One of the main approaches to tackle these challenges was to foster citizen participation. More specifically, the Town Hall created a strategic policy entitled “Medellín: Governable and participatory,” to reduce violence and augment state legitimacy. One of the pillars of this approach was to open spaces for political inclusion of citizens creating participatory mechanisms such as participatory budgeting. In the words of the Town Hall, the overall aim of this strategy was to:

Guarantee the exercise of citizen organization and participation, the reconstruction of the social fabric, citizen control of public management, and the recovery of trust in the State to achieve the full exercise of participation and the development of participatory democracy in a complementary manner to representative democracy (Concejo de Medellín, Citation2004, p. 35).

shows the theory of change explained by the Town Hall to combat violence and the low legitimacy of the State with the strategic line “Medellín: Governable and participatory,” as explained above.

Figure 3. Strategic line ‘Medellín: Governable and participatory,’ included in Medellín’s development plan of 2004–2007.

As can be noticed from the figure, participatory budgeting emerged as a policy in Medellín as part of a comprehensive strategy that aimed to nurture the legitimacy of the State’s institutions and security of the population in opposition to corruption and violence. Overall, two approaches emerged in the strategy: to boost civic culture and the control of the population by the legal authorities. One of the measures intended to produce these outcomes was participatory budgeting.

Hence, overall, the insertion of participatory budgeting as a city-wide policy in Medellín intended to foster the political inclusion of marginalized populations, while former paramilitary combatants were demobilizing in the city amid violence. However, the data collected in this research consistently shows that the influence of participatory budgeting on political inclusion has conflicting findings that are affected, amongst others, by broader patterns of violence in Medellín.Footnote5 In the words of a social leader in Medellín (Interviewee 2, Citation2017), who oversees the expenditure of participatory budgeting resources:

Participatory budgeting created a negative process where some people, instead of being empowered, took over the resources. Citizen participation was distorted. It became a struggle and even led to deaths. One person in Comuna 6 was killed for engaging in oversight activities. Some armed actors captured these resources […]. Despite the challenges, participatory budgeting has also been an important pilot for citizen participation. We have won with this process because we have learned how immature we are in participatory issues.

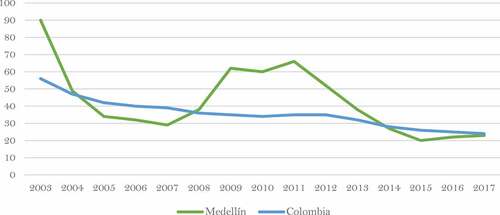

As can be noted, the introduction of participatory budgeting to Medellín in 2004 did not automatically lead to a political inclusion capable of preventing new conflicts from emerging. In fact, three years after the policy started in 2004, violence augmented in the city and was followed by a subsequent decrease in 2011. depicts the rate of violent homicides in Colombia and Medellín from 2003 to 2017 per 100,000 inhabitants, showing the increased rate of homicides from 2007 to 2011. During this period, power struggles arose between different illegal groups in the fight over the control formerly exercised by paramilitary groups (Aricapa, Citation2017; Restrepo, Citation2010).

Figure 4. Rate of violent homicides in Colombia and Medellín from 2003 until 2017 for every 100.000 inhabitants.

According to Doyle (Citation2018), two narratives explain these described patterns of violence. First, she outlines the “orthodox explanation,” which focuses on the positive impact of social urbanism policies in the city since 2004 (such as the participatory budgeting process) to raise welfare levels and increase political inclusion among the poor and marginalized populations. This is what some scholars and policy-makers label as the “Medellín Model” (Abello-Colak & Pearce, Citation2015, p. 151); i.e. “a multipurpose approach to secure the city which relied on a combination of strategies and tactics to deal with violence and insecurity,” such as urban transformation, participatory mechanisms, and security provision. Second, Doyle (Citation2018, p. 12) proposes an “alternative explanation” in which “homicide patterns in the city can be widely explained by conflicts, and agreements, between the major criminal actors.”

In turn, Abello-Colak and Guarneros (Citation2014), Abello-Colak (Citation2015) and Abello-Colak and Pearce (Citation2015) also provide a critical approach to the study of urban security in Medellín. These authors claim that some mechanisms used by the state to provide security, such as participatory budgeting, despite positive outcomes like access to fundamental rights, in turn also allowed violent actors to deepen their influence on the communities, now forced to navigate complex structures where legal and illegal actors exercise authority. Hence, de facto, participatory mechanisms intended to foster political inclusion of marginalized citizens, in some cases were actually used by criminals to benefit and exercise power on already vulnerable communities, feeding on them to gain territorial and economic control. A power battle hid in the “invisible frontiers” between the legal and illegal actors in Medellín.

In this paper, I suggest insights into the influence of participatory budgeting on political exclusion as one of the triggers and consequences of violence in Medellín, that could further add to the referred critical approaches to security in this city. In this account, I argue that a power battle lies at the heart of participatory budgeting; this clash might hinder or foster political inclusion, depending on the design and implementation of the participatory budgeting process, which is affected and affects broader patterns of violence. When the process nurtures inclusion, it accomplishes the preventative purpose at the core of its origins. Nevertheless, when it feeds exclusion, a new cycle of conflict recurrence begins. Although these insights do not show a link to homicide rates, they provide a qualitative account into the mechanisms affecting the “orthodox explanation” and involvement of criminal groups in local governance arrangements, specifically for Medellín’s participatory budgeting process.

The legal design of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process

The power exercised by citizens in the participatory budget is limited to 5% of the public resources. In other words, the political inclusion of citizens in budgetary decisions through this process is bounded to the referred amount, decided by the City Council in the Accords nº 043 of 2007 and 028 of 2017. The participatory budget is annually distributed among all the sixteen comunas and five corregimientos of Medellín, depending on the number of inhabitants and the quality of life index (de Medellín, Citation2017). The Mayor and City Council decide yearly the other 95%, using a process of public budgeting in which the Town Hall presents a bill to the City Council for discussion and approval, including the budget’s incomes and expenses.

A failure to reach an agreement about the rules applicable to Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, has been persistent since its origins. Power disputes between different actors throughout the years have influenced the regulation of the process. In some cases, the pressure of some actors has triggered the inclusion of some participants, such as non-associated citizens; however, this has also affected other power holders who, in turn, have sparked new reforms, either in the City Council, the Town Hall or the judiciary. Legal norms have also intended to prevent the exercise of undemocratic practices that may end in the capture of the participatory budget. Yet, difficulties in the implementation of these rules and a level of legal uncertainty still exist in the participatory budgeting process due to power disputes at its core.Footnote6

The influence of ICTs on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process

In this section I examine the findings of my research regarding the influence of ICTs on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process in the view of its participants. In relation to this question, I explore if digital tools have a specific influence on political inclusion on Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, that would not occur if it operates solely offline. I answer this question in this section, arguing that ICTs can change the power dynamics in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process; nevertheless, their use has mixed findings, leading to both inclusion and exclusion, depending on how they are designed and implemented. If their design and implementation allow for the process to be more transparent and to encourage open competition between the different actors that participate in the process, ICTs may lead to inclusion. If their design and implementation are opaque and allow for capture by specific participants to take place, they may encourage exclusion.

Inclusion and exclusion in the design of digital tools in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process

At its origins, Medellín’s participatory budgeting process took place solely offline. The assemblies, meetings and elections were all held in physical spaces throughout the city. Only since 2017, online tools have been added to the process. Article 53 of the Decree nº 0697 of 2017 (de Medellín, Citation2017), which regulates Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, states that “the process can include ICTs used frequently by the population – such as webpages, smartphone applications, social networks and digital games–, to enhance information, participation, decision-making, collaboration and transparency in participatory budgeting,” whereas Article 5 allows to carry out both offline and online voting processes.

Medellín’s approach to ICTs on its participatory budgeting process surpasses online voting and includes these tools in different stages and for diverse needs. During the course of my research, I found that this multifaceted approach encourages a nuanced response to the question on the influence of ICTs on the political inclusion of the participants in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. For instance, the use of digital tools for online voting sparked concerns about security, access, and deliberation in many participants (Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academia, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, Citation2016).

To name a few examples, during an observation of the voting process of Medellín’s participatory budget in November, 2017, several participants of the Comuna One denounced that some people bought sim card numbers to have several online votes, whereas others couldn’t access the digital voting tool. However, other people mentioned that online voting gave them more opportunities to vote. This is the case, for instance, of citizens interviewed during an online voting exercise fostered by Medellín’s Town Hall in 2017, in which a bus was adapted with computers and traveled throughout the city to teach people how to vote online and give them opportunities to do so. This is portrayed in .

Figure 5. Medellín’s bus to foster online voting in the participatory budgeting elections of 2017.

Likewise, during the focus groups to explore the use of ICTs in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process conducted in the course of this research, participants agreed that digital tools could be used for a broad range of purposes in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. For instance, many participants perceived that there were not enough channels of information about the process, which resulted in the exclusion of many citizens. Hence, they suggested the need of using a broad range of digital tools, such as webpages, online bots, and smartphone applications, to inform the citizens about resources’ spending, how the process works and opportunities to participate, as it is shown in .

Figure 6. Digital tools proposed by Medellín’s participants to foster inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process.

Analyzing the policy that acts as a legal backdrop for the use of ICTs in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, a rupture is found between the “law in the books” and the “law in action” in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. While the former presumes that technology use in democratic processes will bring transparency, accessibility, and security, in the latter technology does not necessarily equate to a more transparent, open, and secure participatory budgeting process. As I further discuss in the next subsection, digital tools in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process are not neutral. Their design and implementation affect its influence on political inclusion, both with the capacity of producing inclusion and exclusion.

Influence of ICTs on the openness of the participatory Budgeting process: Capture versus competition

A first distinct effect of ICTs on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, identified in the data, regards its capacity to influence the openness of the participatory budgeting decision-making process, either nurturing competition or fostering capture. One of the main possible positive features of the use of digital tools in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process identified in the observation process, focus groups, interviews, and surveys conducted for this research, was its potential capacity to make the process more open to participants, increasing participation. For instance, discussing the main opportunities of tech tools in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, one participant answered in a survey:

Technology may augment the number of citizens that participate in the participatory budgeting elections, reducing the concentration of power in the same leaders (Survey Participant 1, Citation2016).

Another participant replied: “Technology allows to reach more people, enhancing inclusion in the process” (Survey Participant 2, Citation2016). In a similar vein, Medellín’s Subsecretary of Local Planning and Participatory Budgeting, Ana Lucía Montoya (Citation2017c), mentioned during a meeting at the City Council: “Technology and social media […] need to be implemented to open the space for citizen participation.”

The level of participation in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process is very low. Hence, some participants in the research considered that creating a new digital channel for engagement in the process, accessible to all citizens, could enhance participation. Thus, the use of ICTs to make the process more open would, in this vein, nurture competition and prevent capture. In the words of a survey participant (Survey Participant 1, Citation2017),

Using a tech tool could eliminate harmful leaderships that, using political manoeuvring, form closed groups to perpetuate in power.

Nevertheless, during the course of the research, it emerged from the data analysis that not all technology design and implementation could achieve a positive impact to bring more participants to the process. In the words of a survey participant, the influence of technology in the participatory budgeting process “depends on the ethical and political aims of the tool. The tool itself would not change anything” (Survey Participant 2, Citation2017).

Per the case of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, although many participants answered in a survey conducted in four focus groups carried out in the course of this research, that digital tools could contribute to foster participation, the explanatory answers provided also draw attention to many situations that might actually deepen marginalization by facilitating capture (Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academics, Citation2017).

To mention some of them, some participants were concerned about the digital divide, and how in practice designing technological tools without bearing in mind socioeconomic issues could actually bring exclusion. Hence, they were afraid that the use of online tools could exclude populations that are not acquainted with the use of certain technologies or that do not have access to them, such as the elderly. Additionally, other participants were also worried about the lack of deliberation and the automation of the process if digitals tools were included, and they mentioned that it was difficult to trust in a technology designed and controlled by authorities that they did not trust in. These concerns were also addressed by some participants during the participant observation process carried out in this research. To give an example, during an internal discussion, City Councillor Luz María Múnera (Citation2017g) claimed,

Participation through the internet, in which we just open a computer and vote, denies our human nature. We are not automats. The political exercise of participation is mainly physical.

What is more, some participants expressed concerns about the tech tools replacing offline meetings, that the process could be limited to what the tool did, or security issues about their privacy. Precisely due to this, the data shows that ICTs within Medellín’s participatory budgeting process are seen both as tools that could help foster inclusion through a more open process, but also as instruments that could nurture capture and, thus, increase exclusion. Similar claims, both in favor and against tech tools to favor the openness of Medellín’s participatory budget, were found in the observation of the 2017 voting process.

Influence of ICTs on the control over the spending of the budget: Opacity versus transparency

A second main effect of ICTs on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, identified in the data, is its capacity to influence the control over the resources’ spending, either enhancing transparency, or augmenting opacity. More specifically, it was identified in the data that some digital tools could enable an easier access to information about the participatory budget to a broad range of participants, facilitating community oversight and, hence, social control.

For instance, one participant in the previously referred survey, conducted during the course of this research, mentioned that ICTs could help “inform citizens about the real impact of the investment of resources in the participatory budgeting process” (Survey Participant 3, Citation2017). In turn, another participant mentioned that “ICTs could enable a broader dissemination of information about the participatory budgeting process in the community, with permanent citizen feedback” (Survey Participant 4, Citation2017).

One of the main challenges affecting the influence of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process on political inclusion, identified in the research, is that the everyday citizen lacks accurate and non-technical information about the process. This affects the level of citizen participation and eases the possibility of people interested in having their personal interests being benefited through the process to be able to capture the budget, enhancing exclusion. In the words of a survey participant, part of Medellín’s Town Hall, “there is a group of citizens that we have been unable to reach because they do not know about the process. With technology we could reach them” (Survey Participant 5, Citation2017). In this vein, another participant mentioned in the survey (Survey Participant 6, Citation2017),

As long as the participatory budgeting process lacks a real strategy for communications, participation will be low and the opportunity to see more and new positive and innovative leaderships will be lost.

In four focus groups conducted during the course of this research, many participants highlighted a broad range of information about the participatory budgeting process that could be shared in a digital tool, including basic data about what the participatory budget is and how it works, what are the local development plans of each locality, the opportunities and dates to participate in the process, the impact of the projects, and news about their execution (Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academics, Citation2017; Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall, Citation2017). Furthermore, in the 2017 public hearings about the change of regulation of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, the need to use digital tools to share data about the spending of the resources was also stressed. For instance, César Augusto Hernández (Citation2017), director of Medellín’s Department of Planning, asserted in a public hearing,

All the information about the participatory budget needs to be in a platform that allows to share georeferenced information. This is a debt of the municipality […]. I have today a team documenting more than 478 investment projects to provide accurate information of their finances.

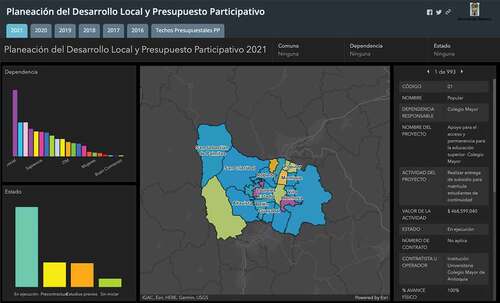

This map is now publicly available on the webpage of Medellín’s Town Hall since 2018, allowing any citizen to consult the information about resources’ spending online. A picture of this information platform is depicted in

Figure 7. Information platform that shows the spending of Medellín’s participatory budget.

However, as it happens with the influence of ICTs on the openness of the participatory budgeting process, during the course of the research the data showed that some digital tools could foster opacity instead of transparency. In this case, many participants featured the access to the tools as a gamechanger for it to really be able to enhance transparency. In the words of a participant in a survey, “the tool by itself is not enough, there is a need for participants to know how to use it and secure their access where they are” (Survey Participant 7, Citation2017). In turn, another participant mentioned in a survey that a technological tool “could reduce a knowledge gap that could help have more symmetrical power relationships, as long as there is an access to the tools, which cannot be guaranteed in many places” (Survey Participant 8, Citation2017). More often than not, participants referred to a lack of internet connection, devices to connect, and knowledge about how to use some ICTs, as main barriers of access.

Designing for exclusion and inclusion: The case of Nuestro Desarrollo

One example of how the design of a tech tool for Medellín’s participatory budgeting process may affect inclusion, emerged during the process of collaborative design with participants of Medellín of a trial technological tool during the course of this research, as I referred in the methodology section. When the research started, in 2016, a first prototype proposed for a digital tool in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, was an application that people could easily download on their smartphones. This application originally mirrored the existing offline process and was mainly focused on online voting.

Yet, after discussing the idea with participants in focus groups, three main problems of the initial design were identified, that could actually foster exclusion instead of inclusion (Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academics, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, Citation2016). First, many participants were skeptic of downloading governmental apps on their phones; they did not trust in them, and the apps took away valuable memory space in their phones that they prefer to use in other apps, videos, or pictures. This created a barrier of access to the tool. Second, many participants claimed that a majority of citizens did not really know how the participatory budgeting process worked or, if they did, they did not trust in it. Hence, before making a tool to open a new avenue of access to the process, it was needed to create one that facilitated learning, information-sharing, and trust-building. Lastly, it consistently emerged in the data that a tech tool that focused mostly on voting could intensify the rupture between planning and budgeting that existed in the process, nurturing capture. In the words of a survey participant “citizens need to understand the collective purpose of the budget; identify collective instead of individual problems” (Survey Participant 9, Citation2017).

As a result, after discussing the original idea with a broad range of participants, the design of the tool that finally emerged in the research changed completely from the initial one. The tool embraced the multifaceted approach to the adoption of ICTs in the participatory budgeting process discussed earlier, and included diverse features, trying to minimize the risks of exclusion identified by participants. The tech tool that emerged from the collective design, called Nuestro Desarrollo (Our Development, in English), consisted of a web-based application that did not need to be downloaded and could be accessed in a broad range of devices such as smartphones, tablets and computers, enabling citizens to carry out four main functions. First, the Town Hall could inform the citizens about the process. Second, the citizens could identify the main needs of their territories and make proposals of projects to solve those needs through a collective creation of local development plans. Third, citizens could prioritize projects to finance with the participatory budget with a digital voting feature. Lastly, citizens could monitor and oversight the implementation of projects financed with the participatory budget. The landing page of the platform is portrayed in .

Figure 8. Landing page of the web-based application Nuestro Desarrollo, created during the course of the research.

Likewise, the tool included a digital game, called Nuestra Comunidad (Our Community, in English) that taught citizens how the connection between local planning and participatory budgeting works, enabling them to make changes in their neighborhoods to solve collective needs with points earned in the game. depicts the landing page and some features of Nuestra Comunidad. Once participants logged into the game, they could choose amongst different categories of their interest, such as sports, infrastructure, social inclusion, culture, and environment, to play and earn points that they could later use to solve a problem at their communities within the game.

Figure 9. Landing page and features of the web-based game Nuestra Comunidad, created during the course of the research.

An educational and gamified approach to participatory budgeting emerged on several occasions during the design process of the tech tool (Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academics, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, Citation2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, Citation2016). For instance, a participant mentioned in a survey:

There is a need to foster education for citizen participation. A digital tool could create new channels for interaction, but by itself it won’t make an impact if it does not go along with learning (Survey Participant 10, Citation2017).

In turn, another participant highlighted that education for collective learning could change the existing political culture in the participatory budget:

The change of the political culture requires information, pedagogy and encouraging collective practices of planning and participation, not only in a physical, but also in a digital space (Survey Participant 11, Citation2017).

The tech tool that emerged in this study throughout a collaborative research with various participants of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, is just one of many possible digital tools that could be used in the process. It was created with the purpose of learning the possible uses of technology in the process to foster political inclusion, along with the risks and opportunities of technology use in the participatory budget, assessing diverse technology designs with a broad range of participants of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process. The project was carried out during a two-year span that mainly involved the tool design and trial of its basic features in controlled focus groups, surveys, and semi-structured interviews.

Although the tool was licensed to the Town Hall of Medellín in 2019, who later adapted it to include some of the features in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, its implementation in a real-life setting has not been evaluated, and has changed with time as the Town Hall adapted it to its internal and existing processes. Nevertheless, the process of collaborative design of a digital tool for Medellín’s participatory budgeting process during this research resulted in valuable data, such as the participants’ views shared during the surveys, interviews and focus groups, used in this paper to explore the influence of ICTs on political inclusion on Medellín’s participatory budgeting process.

More specifically, besides showing how diverse technology designs could foster either opacity or transparency and capture and competition, the process of creating the referred tool taught three main valuable lessons about the design of ICTs to foster inclusion in the participatory budgeting process. First, it emerged as a priority the need to include a broad range of participants in the technology design, to minimize risks of unintended consequences, such as preventing access. This stakeholder engagement, not only in the implementation, but first and foremost in the design of the digital tool may nurture inclusion while fostering trust in the technology and local authorities in the context of mistrust and skepticism.

The second lesson has to do with the previously referred divergence found in this research, between the “law in the books” and the “law in action.” Although the “law in the books” on technology use in participatory processes in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process presumes that digital tools could instantly augment participation and transparency in the process, the “law in action” shows that not this is not a given result. How the tech tools are designed and implemented matters to favor inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process.

A final lesson involves the divergence between the fast pace in which technology evolves, versus how slow change can be in practice when applying technological tools in democratic processes. Information and communication technologies are not an automatic game changer of power dynamics, and can in fact alter them for exclusion, even when the best intentions exist. Therefore, their design and implementation in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process needs to be carefully monitored through time, with patience about the final results.

For instance, in 2019, after two years of the implementation of online voting to prioritize Medellín’s participatory budget, and supporting digital tools such as a site to inform citizens about the process, in a focus group carried out in the course of this research, members of Medellín’s Town Hall highlighted both benefits and challenges of using online tools in the process. As positive features, participants noted that the digital tools have increased citizen participation and allowed citizens to have more information about the process. Still, the participants acknowledged that there is still a lack of pedagogy of the process and that there are some citizens who find it difficult to access or use technological tools. In this sense, they stressed that, among the challenges of implementation, problems in connectivity stand out, while there is a need to educate more older populations on how digital tools function. shows an image of Medellín’s Town Hall’s webpage of the participatory budgeting process, along with an image of the adaptation made in the Town Hall in 2019 of the tool Nuestro Desarrollo, part of this research (Members of Medellín’s Town Hall, Citation2019).

Figure 10. Medellín’s Town Hall’s webpage of the participatory budgeting process and the tool Nuestro Desarrollo.

Conclusion

Following Sampaio and Peixoto (Citation2014), instead of enquiring about the potential of technological tools to enhance democratic processes, this paper asks how different designs of online tools and various forms of use and ownership interact in diverse contexts toward a final result. Hence, exploring the influence of digital tools on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, I argued that the technology design and implementation are not neutral and can, in fact, change power dynamics for the better or worse. Therefore, I claimed that a participatory design of online tools could foster inclusion by incorporating the views of diverse participants, thus minimizing risks of unintended consequences, such as preventing access.

Likewise, in line with, among others, Bardall (Citation2013), Shapiro and Siegel (Citation2015), and Tellidis and Kappler (Citation2016), this paper shows that technology can both influence positively and negatively political inclusion in peacebuilding contexts. Therefore, as per Gaskell (Citation2019), this paper does not support standings of technological determinism. Hence, the paper adds to the literature on eDemocracy by depicting a disparity between the “law in the books” and the “law in action” regarding the use of online tools in Colombian democratic processes, and Medellin in particular. Contrary to normative assumptions, “on the ground” perceptions of online participatory budgeting do not necessarily consider it as transparent or inclusionary.

Therefore, this study of Medellín’s hybrid participatory budgeting process shows that technology is not neutral and an automatic positive game-changer in power dynamics in conflictive contexts. Close attention should be paid to its design and implementation for it to fulfil the desired effects. Hence, digital tools can take a variety of forms in Medellín participatory budgeting process that shape their effects on political inclusion. Their context-specific and participatory design is pivotal to foster inclusion, as claimed for other peacebuilding scenarios by, among others, Puig and Kahl (Citation2013), Mancini and O’Reilly (Citation2013), and Gaskell et al. (Citation2016). This evidence favors incremental technology contributions to Medellín’s participatory budgeting process (Fung et al., Citation2013), in which ICTs are not expected to be a radical game-changer in the enhancement of democracy (Fung et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Sampaio and Peixoto, Citation2014, p. 413). Furthermore, the paper adds to the literature on the use of games in participatory budgeting processes, by exploring perceptions on the ground regarding educational uses of games to counter opacity and capture in Medellín.

The findings of this research show that technological design matters to shift power dynamics. Hence, designs that favor participatory approaches may decrease unintended consequences and exclusion by design. How the implementation of diverse technological designs in hybrid participatory budgeting processes influence political inclusion through time is a promising further avenue for research that emerges from this study. Furthermore, as a reviewer of this paper noted on their valuable comments, “the implementation of participatory planning processes faces differentiated challenges” in contexts that face “violence” or “armed groups exercising territorial control.” This affects the influence of technology on political inclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting context in a way that may be different to a scenario that does not face an armed conflict.

Overall, in the paper I discussed how ICTs could lead to both political inclusion or exclusion in Medellín’s participatory budgeting process, depending on how they are designed and implemented. Due to the nature of the methodology chosen, my findings may not be generalized to other cases; nevertheless, they could act as a basis for further testing, for instance in multiple cases, that may allow them to be generalized, disproved or complemented, so as to continue charting relationships between participatory budgeting and political inclusion in peacebuilding scenarios.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this paper, I mean with “international scholarship” the works that examine cases that do not include Colombia, with “national scholarship” the research that surveys Colombia explicitly, and with “local scholarship” the literature that discusses Medellín’s case.

2. As I previously referred, this paper is part of a PhD thesis. In the broader dissertation that is paper is based on, I detail how I used grounded theory in my research. It can be consulted in this link: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:4586520e-4240-45b9-83d2-ce949381da7e?s=09.

3. The design and pilot evaluation of the tool was financed by Build Up’s Build Peace Fellows Program, which also provided technology support, training and mentoring for the project. Helena Puig, Michaela Ledesma, Jen Gaskell, Jacob Lefton, and Jerry McCann, part of the original team of Build Up, provided valuable recommendations for the development of the digital tool. A team of six developers and designers that I directed, programmed, and developed the tool based on paper prototypes. The technological development was carried out by Andrés Pardo, Gabriel Vasco, Héctor Alzate, and Fabián Castillo, and the graphic design by Juan David Peña and Santiago Sotomayor. An initial digital prototype of the tool was built by Diego Ballesteros, Lukasz Gintowt, and Alec von Barnekow, three pro-bono developers at Build Up and International Alert’s #peacehack in Zürich in September of 2016. Luis Alberto Hincapié, Jasbleydy Pirazán, and Dominique Khalil provided valuable assistance in the process of data collection, management, and analysis for this research. Thanks to the support of the Research Accelerator Grants of the University of Oxford’s Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, I licensed the tool to Medellín’s Town Hall in April 2019, along with an implementation strategy, so that its use could be scaled in this city as a digital complement to the existing participatory planning and budgeting processes.

4. The National Front (in Spanish, Frente Nacional), was a coalition created in 1958 by the Colombian Conservative and Liberal parties to alternate power every four years until 1974 (Palacios, 2003).

5. The data includes, among others, several interviews (Interviewee 2, 2017; Interviewee 4, 2017; Interviewee 5, 2017; Palacio, 2017; Rodríguez, 2017b; Interviewee 6, 2017; Urán, 2017b), interventions of a broad range of participants in the participatory budgeting process during various hearings (García, D., 2017a; Echeverri, 2017a; García, D., 2017a; Rodríguez, 2017a; Vesga, 2017), focus groups (Participants of Medellín’s Town Hall and academics, undefined; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven, 2016; Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One, 2016), and newspaper articles (Gaviria, 2017; La Silla Vacía, 2010; Sandoval, 2015).

6. A detailed analysis of the legal design of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process can be found in: Dajer (2022). Pathways to inclusion and exclusion: An analysis of Medellín’s participatory budgeting process (2004–2017) [Oxford University]. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:4586520e-4240-45b9-83d2-ce949381da7e?s=09.

References

- Consejo de Estado, Sala de lo Contencioso Administrativo, Judgement n° 05001233100020100131401 of 2019, C.P. Nubia Margoth Peña, Colombia

- Consejo de Estado, Sala de lo Contencioso Administrativo, Judgement n° 05001-23-31-000-2009-01088-01, C.P. Oswaldo Giraldo López, Colombia.

- Juzgado 12 Administrativo Oral de Medellín, Judgement n° 091 of 2014, Colombia.

- Juzgado 33 Administrativo Oral de Medellín, Judgement n° 077 of 2016, Colombia.

- Tribunal Administrativo de Antioquia, Judgement n° 029 of 2013, Colombia.

- Congreso de la República, Constitution of 1991, Colombia.

- Congreso de la República, Law n° 131 of 1994, Colombia

- Congreso de la República, Law n° 134 of 1994, Colombia.

- Congreso de la República, Law n° 136 of 1994, Colombia.

- Congreso de la República, Law n° 152 of 1994, Colombia.

- Congreso de la República, Law n° 1757 of 2015, Colombia.

- Alcaldía de Medellín, Decree n° 0697 of 2017, Colombia.

- Concejo de Medellín, Accord n° 043 of 2007, Colombia.

- Concejo de Medellín, Accord n° 028 of 2017, Colombia.

- Participants of Medellín’s Comuna One. (2016). Focus Group 3, organized in Medellín by the researcher [24/08/2016].

- Participants of Medellín’s Comuna Seven (2016) Focus Group 2, organized in Medellín by the researcher [23/08/2016].