Abstract

A large proportion of the Swedish housing stock was built when policymakers and housing industry rarely considered housing accessibility issues. More than 80% of Swedish citizens aged 65+ live in dwellings built before 1980. Using detailed research data from onsite observations, we explored housing accessibility issues for people with different complexities of functional limitations. Four typical dwellings were selected, two from the 1960s and two from the 1990s. Accessibility problems were considerable, also in newer dwellings. Design features that need particular attention are highlighted, serving as research-based input to policymakers, public agencies and actors involved in housing development and provision.

Introduction

An aging population

Of the Swedish 10 million population, close to 2 million (19.8%) are aged 65+ (SCB Statistics Sweden [SCB], Citation2017). Thus, Sweden is approaching the level of a “super-aged aged society,” that is, with at least 20% of the population aged 65+ (World Health Organization, Citation2003), though the aging rate has slowed down in recent years. In 2000, Sweden was ranked fifth (22.2% aged 60+) in the UN’s global demographic comparison but dropped to twelfth place (25.5% aged 60+) in 2015. The populations of Japan (33.1% aged 60+), Italy (28.6%) and Germany (27.6%) were then ranked as the oldest in the world (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [UN], Citation2015). Population aging is in many ways a positive development, with an increased life expectancy and for many people more years of active and enjoyable living. However, to realize the positive potential of longer lives, population aging requires a societal transformation toward the needs of people as they age.

One of the societal challenges posed by population aging concerns the provision of housing that is suitable for people as they age and face growing health problems and functional decline. For example, previous research in Sweden has shown that approximately 30% of people aged 65–74 and approximately 70% of people aged 75–84 have mobility limitations (Slaug, Citation2012). A gradual functional decline is part of the aging process, often manifested by various functional limitations such as emerging balance and coordination problems, limitation of stamina, reduced fine motor control, visual impairment, etc. (Bendayan et al., Citation2016; Verbrugge & Jette, Citation1994). These kinds of problems make it more demanding to move around in the environment, to activate controls and functions on home appliances, to reach objects and manage day-to-day life at home. Moreover, functional limitations tend to accumulate and many older people have combinations of different complexity, such as both limitations in movement and reduced capacity in hands and arms or both limitations in movement and vision impairment (Slaug et al., Citation2016; Verbrugge et al., Citation2017). Despite health problems and functional decline, 95% of those aged 65+ live in ordinary housing in Sweden, including 87% of those aged 80+ (National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2016). As in many other countries in the Western World, this is a result of an active aging-in-place policy, and a reflection of the wishes and desires of most people (AARP, Citation2012; Kramer & Pfaffenbach, Citation2016). Yet, to support active and healthy aging, it is crucial that the housing stock is designed to meet the needs of people with declining functional capacity. Otherwise, accessibility problems will emerge and negatively impact on people’s possibilities to perform activities of daily living independently (Iwarsson et al., Citation2007), constitute fall risks (Iwarsson et al., Citation2009), and lead to relocation to residential care facilities (Granbom et al., Citation2014; Stineman et al., Citation2012). Moreover, independence in activities of daily living is associated with several other aspects of health and well-being (Kylén et al., Citation2017; Mahler et al., Citation2014).

An aging housing stock

As the Swedish population is aging, so is the housing stock. The vast majority of community-living older adults reside in dwellings built during periods when public authorities and private actors paid little attention to the needs of people aging with functional limitations. Of adults aged 65 years or older, more than 80% live in dwellings built before 1980 and almost 30% live in dwellings built before 1950 (Granbom et al., Citation2016). In Sweden, the 1960s marked the beginning of a period of massive nationwide multi-family dwelling construction. This period, when quantity and rapid production were prioritized, is known as the “Million Home Programme” and lasted through the 1970s (see, e.g. Emanuelsson, Citation2015). Today, these dwellings constitute 40% of the total multi-family dwelling stock in Sweden (Pettersson et al., Citation2017). Since the 1990s building legislation and housing standards in Sweden have incorporated accessibility requirements, but at the same time new production has slowed down considerably (Swedish National Board of Housing, Building & Planning, Citation2011). Even if Sweden is a country with very high housing standards, these developments have led to a situation where considerable proportions of the housing stock do not accommodate the needs of the aging population (Granbom et al., Citation2016; Pettersson et al., Citation2017).

There are 290 highly self-governed municipalities in Sweden. The municipalities are obliged to ensure housing provision for their inhabitants, including physical planning at the municipality level. Despite a longstanding national population increase in Sweden, population levels are decreasing and aging more rapidly in more than half of all municipalities, especially in rural areas where the fertility rates are lower and younger people tend to move. The municipalities with decreasing population levels have been identified as having the greatest difficulties in providing accessible housing for older adults (Swedish National Audit Office, Citation2014). In rural areas, the Swedish housing stock is dominated by single-family dwellings and more than half of the population aged 65+ own and live in such dwellings (SCB, Citation2017). Where older adults are living in mostly urban multi-family dwellings, approximately half are renting their flats while the other half have a form of self-ownership. Of the entire housing stock (approximately 4.5 million dwellings), 28% are occupied by at least one individual 65 years or older.

Individual housing adaptations and home modifications

Individually-tailored housing interventions that permanently alter the home environment are termed housing adaptations in Sweden (Swedish National Board of Housing, Building & Planning, Citation2000). Such interventions are governed by specific legislation, are tax-funded and based on functional needs, regardless of age. The annual expenditure for housing adaptations in Sweden is more than SEK 1 billion and approximately 74,000 housing adaptations are granted each year (Swedish National Board of Housing, Building & Planning, Citation2016). Of those granted, about 70% are for people aged 70+ and about 30% are aged 85+. The individual is granted public funding for housing adaptation by a municipality official, who bases the needs assessment decision on a certificate issued by another health professional, in most cases a registered occupational therapist. This certificate, that is required by law, focuses on assessments of the physical environment in relation to the capacity of the individual and specific individual needs (Fänge et al., Citation2013). Housing adaptations can be seen as a specific kind of the more broad concept of home modifications. For example, in the U.S. home modifications include both advice on modifications of the physical environment, provision of assistive technologies, and related training (Gitlin et al., Citation2006). However, in Sweden, as well as worldwide, housing adaptations and home modifications provide one of the key avenues to support daily activities for people aging in ordinary housing with accessibility problems.

Since the late 1940s, housing construction in Sweden has largely been determined by government policy, conforming to common building standards (International Council for Building Research, Studies & Documentation, Citation1965). At this time, that is the late 1940s, the housing situation in Sweden was still characterized by overcrowding and shortage of appropriate housing for large parts of the population (Public Housing in Sweden, Citation2018). As a result of a government proposition from 1946, which placed the responsibility for housing provision on the municipalities, municipality-owned public housing companies were formed all over Sweden. These municipality-owned public housing companies have been instrumental in realizing government housing policies. Thus, there are many multi-family dwellings with similar construction and design features, making it possible to identify typical dwellings in the Swedish housing stock (Emanuelsson, Citation2015). Consequently, housing accessibility problems are likely to be similar across many dwellings, but research concerning such problems for people aging in these typical dwellings is limited.

This paper examines how the structure and design of typical dwellings built in different time periods influence housing accessibility and older adults’ possibilities to age in place. The aim was to analyze potential accessibility problems for people aging in ordinary Swedish housing stock.

Methods

Typical dwelling cases

Housing information on four selected dwelling cases was taken from the Swedish ENABLE-AGE Survey Study; part of a cross-national European project undertaken in 2002–2004 (Iwarsson et al., Citation2007; Oswald et al., Citation2007). For the baseline data collection of that survey, after approval by the Ethics Committee at Lund University (LU 324, 2002), participants aged 80–89 and living alone in ordinary housing in three municipalities in southern Sweden were randomly selected from the National Public Register. Data collected through home visits included basic housing characteristics such as type of dwelling, year of build, number of rooms (not including kitchen and hygiene rooms), floor level, tenure, etc. (for details, see Iwarsson et al., Citation2007). The dwellings were representative of the Swedish ordinary housing stock at the time (Granbom et al., Citation2016). The four cases were purposely selected to exemplify typical dwellings from two time periods, reflecting “older” housing and building policies (two cases from the 1960s) and “current” policies (two cases from the 1990s), especially in regards to accessibility (for details, see ).

Table 1. Overview of four typical dwelling cases in Sweden.

Multi-family dwellings from the “Million Home Programme” in the 1960s were often built as buildings with eight or three floors. We selected dwelling cases 1 and 2 as examples of such buildings (see ). Further, we selected two- or three-room dwellings as our cases, as these comprised almost 70% of our sample. This is a proportion that is higher than for the population in average; about 30% of the Swedish housing stock consists of two- or three-room dwellings (SCB, Citation2010). However, older people tend to live in smaller dwellings and downsizing is a common reason for relocation at old age (Abramsson & Andersson, Citation2012; Banks et al., Citation2012). For illustrations of all four dwelling cases selected for the current study, see .

Figure 1. Upper left and upper right: multi-family dwellings from the mid-1960s, exemplified by dwelling cases 1 and 2; lower left: multi-family dwelling from the 1990s, exemplified by dwelling case 3; lower right: single-family house from the 1990s, exemplified by dwelling case 4. Note. Photographs by Marianne Granbom. The dwellings in the photos are similar to, but are not the actual dwelling cases of the present study.

Environmental barriers and housing accessibility problems

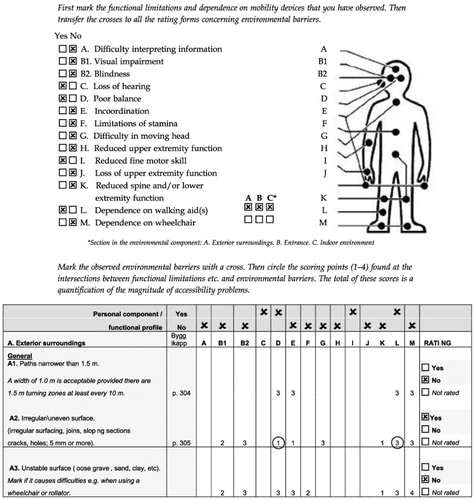

Physical barriers in the housing environment were assessed by means of the Housing Enabler instrument (HE) (Iwarsson et al., Citation2012; Iwarsson & Slaug, Citation2010a). The environmental (E) component of HE includes professional observation by trained data collectors of the presence/absence of environmental barriers, defined according to national standards and guidelines for housing design. For the present study, we used a reduced list of 60 environmental barriers (27 indoors, 13 at entrances and 20 in the close exterior surroundings) representing the core barriers to detect accessibility problems (Carlsson et al., Citation2009; Iwarsson & Slaug, Citation2010b); (see for the full item list). The HE also includes a personal (P) component concerning functional limitations and dependence on mobility devices (12 + 2 items) (see for functional profiles used in this study). To calculate the magnitude of accessibility problems, the HE uses a scoring matrix that combines the P and E components. Problematic P-E combinations have predefined severity ratings (0 = no problem, 1 = potential problem, 2 = problem, 3 = severe problem, 4 = impossibility) that are summed to give a total accessibility problem score (theoretical score range for the reduced HE is 0–904). If there are no functional limitations or dependence on mobility devices, the score is always 0; higher scores mean greater accessibility problems. For an example of the scoring procedure, see .

Figure 2. The accessibility problem score is calculated by combining a checklist of environmental barriers with a checklist of functional limitations; problematic combinations are given severity ratings, which are summed up to a total score. Reprinted with permission from Veten & Skapen HB and Slaug Enabling Development, Sweden.

Table 2. Comparison of the presence of 60 core environmental barriersTable Footnotea, in four typical dwelling cases in Sweden.

Table 3. Four functional profiles representing older adults with combinations of functional limitationsTable Footnotea of different complexity.

The validity of the HE has been successively optimized over 20 years of research (Iwarsson et al., Citation2012). Sufficient inter-rater reliability has been demonstrated in studies in Sweden and elsewhere (Helle et al., Citation2010; Iwarsson et al., Citation2005; Lien et al., Citation2016). The reduced list used in the present study was obtained through a rigorous research process, utilizing statistically defined criteria and an expert panel approach (Carlsson et al., Citation2009).

Functional profiles

In the present study, to demonstrate how accessibility problems vary in the same dwelling depending on the residents’ functional capacity, we employed four research-based functional profiles of different complexity (Slaug et al., Citation2011). That is, we did not use person-related data collected with the individuals actually living in the four dwellings. The profiling methodology made use of Configuration Frequency Analysis (CFA), which is a statistical test identifying what combinations—in our case, of functional limitations and use of mobility devices—that exist significantly more/less frequently than expected in a data set (Krauth & Lienert, Citation1982). Starting out from such analyses, the four functional profiles were identified (Slaug et al., Citation2011) (see ). The prevalence of functional limitations in our dataset is in line with national data available (Slaug, Citation2012), and the four profiles represent 44% of the participants of the Swedish ENABLE-AGE sub-study (profile I: 19%; profile II: 11%; profile III: 11%; profile IV: 3%). That is, these profiles represent large groups of older people with common combinations of functional limitations. However, though prevalent among older people, we did not include cognitive and hearing impairments in the current study. The reason was that there are relatively few environmental barriers in the HE related to these functional limitations.

Data analyses

We used descriptive statistics to present housing characteristics, environmental barriers and accessibility problem scores for the four cases of typical Swedish dwellings. For each, the presence or absence of the 60 core environmental barriers was reported. To explore and estimate accessibility for the four functional profiles in each typical dwelling case, for each profile the HE accessibility problem score was computed (see ). However, as these analyses targeted profiles with functional limitation items joined into broader categories (such as “Limitations in movement,” see ), we applied a somewhat modified scoring procedure. For a given profile, instead of just summing up the individual ratings (1–4) for all the included functional limitations, we first calculated the average rating for each relevant category of functional limitations, and then summed up these average ratings to an accessibility problem score. For example, for the profile “Limitations in movement only” this means the average of ratings for functional limitations D, E, F, G, K (see for legends to capital letters). That is, for barrier A2 (see ) the rating for this profile would be (1 + 1 + 0 + 3 + 1)/5 = 6/5. Thereafter, separately for each profile, the sums of these average scores were calculated over all the individual barriers of the HE.

Results

The two typical dwelling cases from the 1960s had more environmental barriers than the two from the 1990s (N = 36 and N = 29 compared to N = 23 and N = 23, respectively). Environmental barriers concerning access to exterior facilities, such as refuse room, laundry room (shared facilities) and storage area (individual facility) were notable in typical dwelling cases 1 and 2. For example, access to these facilities required climbing stairs or opening heavy doors. The multi-family and the one-family dwellings from the 1990s had instead several barriers related to accessing the letterbox, because it was placed too high or too low. Environmental barriers concerning door and stair features in the entrance were common in all three multi-family dwelling cases, while the one-family house had fewer barriers in the entrance. The multi-family dwelling cases all had many environmental barriers located in the kitchen and hygiene areas, mostly concerning controls and operable hardware.

Six environmental barriers were present in all four typical dwelling cases regardless of when it was built or if it was a multi- or single-family dwelling. They concerned: (1) irregular/uneven surface on pathways in the close exterior surroundings; (2) high curbs; (3) refuse room/refuse bin can only be reached via steps; (4) high thresholds in the entrance; (5) wall-mounted cupboards and shelves placed high in the kitchen; and 6/controls require use of hands in the hygiene area. For details, see .

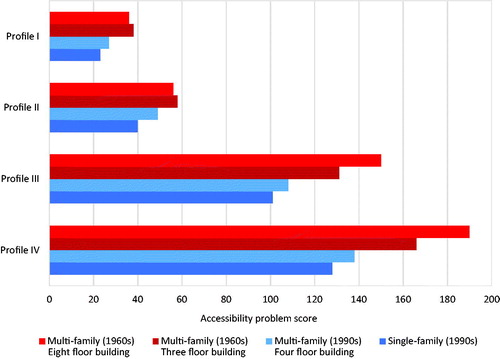

All four typical dwelling cases would cause accessibility problems for older adults with any of the four functional profiles (see ). For individuals with limitations in movement (profile I) or limitations in movement and upper extremity function (profile II) the single-family house had the least accessibility problems. For individuals with more complex functional limitations, including use of mobility devices and visual impairment (profile IV), the most favorable living environment from an accessibility perspective would also be a single-family dwelling built in the 1990s. In contrast, the dwelling that would cause the most accessibility problems would be a multi-family dwelling in a high-rise building from the 1960s, despite the fact that the dwelling had an elevator.

Discussion

Although a difference could be noted between the typical dwelling cases from the 1960s and the 1990s, the results demonstrate that dwellings continued to be built with many environmental barriers even after laws and building legislation supporting accessibility were introduced in Sweden during the 1990s. Applying scenarios with functional profiles representing large subgroups of the aging population to four dwelling cases, accessibility problems were found to be considerable not only in the older but also in the newer dwelling cases.

Although the Swedish housing stock has a high standard in terms of prevalence of necessary housing functions compared to many other countries (see, e.g. Slaug et al., Citation2011), this study clearly demonstrated that many design features that hamper the daily activities of older people are still common. With 95% of people aged 65+ living in ordinary dwellings, the standard, structure, and design of housing are critical to support older adults to age in place and avoid relocation to special housing facilities (Granbom et al., Citation2014; Stineman et al., Citation2012). Examples are steps/thresholds at the entrance and/or between rooms, narrow space that impedes the use of mobility devices, kitchen shelves/cupboards that are difficult to reach, etc. (Granbom et al., Citation2016). For older adults with no functional limitations these common environmental barriers would not generate any accessibility problems. However, as people age the complexity of their functional profiles increases, and the same dwelling with its environmental barriers would increasingly cause more accessibility problems (see ). For example, the results show that for an older adult living in a typical multi-family dwelling built in the 1990s (dwelling 3), the accessibility problem score would increase from 0 to 27 (profile I), 49 (profile II), 108 (profile III) and 188 (profile IV). This result gives incentive for reflection, as many of the design features in the housing environment that appear unproblematic as long as we are healthy and without limitations in functional capacity, may one day seriously hinder us in staying independent and active.

As health problems and functional limitations gradually emerge with age, design features causing accessibility problems in the home environment become more apparent. Many of the early and most common problems exemplified by the results of the current study can be resolved by quite simple home modifications, such as removal of thresholds, installation of grab bars in the hygiene area, improved lighting, etc. (Stark et al., Citation2017). Home modifications can thus be used to support independence and an active life (Wahl et al., Citation2009). Several studies have also shown positive effects of home modifications, both in terms of improving housing accessibility and of associated health-related outcomes such as better opportunities for active and independent living (Ahrentzen & Tural, Citation2015) and a reduction of the number of fall accidents (Chang et al., Citation2004; Pega et al., Citation2016).

At later stages of functional decline, more thorough and comprehensive interventions may be required though, such as stair lifts and replacing large parts of the equipment in kitchen and hygiene area. Moreover, for older adults with more complex functional profiles (profiles III and IV), the results showed that accessibility problems increased significantly compared to less complex profiles, particularly in the dwellings from the “Million Home Programme” of the 1960s. That means the addition of use of mobility devices (that characterizes these profiles) is a prominent trigger of more accessibility problems. Environmental barriers that were present in the older but not in the newer dwelling cases concerned, for example, insufficient maneuvering spaces in kitchen and hygiene area, controls at inaccessible height, thresholds/difference in level between rooms and narrow doors, where the new building regulations are likely to have had an impact. However, there are still many barriers in the kitchen (related to shelves, controls, etc.) and hygiene area (related to controls and equipment) of the newer dwelling cases, indicating a lack of awareness of these issues among actors in the housing industry.

The fact that almost 30% of the dwellings are occupied by at least one individual aged 65 years or older (SCB, Citation2017) puts a high demand on society to provide adequate ordinary housing for senior citizens. Though housing production in Sweden after many years of low levels has slowly started to increase again, it will take a very long time to replace older dwellings (SCB, Citation2010). For a foreseeable future, the majority of the older segment of the population will continue to live in dwellings from earlier building periods. In addition, as the results show even newer dwellings—such as cases 3 and 4—still have design features posing accessibility threats, notwithstanding new laws and building regulations supporting accessibility (Granbom et al., Citation2016). From policy levels, there have even been suggestions to lower the requirements on accessible housing in order to reduce costs and increase the production pace. The results of the present study give further strength to persist in the demands for accessible housing as a more sustainable solution for the future provision of housing.

The more enabling environment of the single-family dwelling among the four dwelling cases needs further discussion. In several respects the single-family dwelling case stands out, the constellation of barriers differed, there were relatively few barriers in the entrance, and the accessibility problem score was consistently lower for all functional profiles. The different constellation of barriers could be related to multi-family building construction more commonly conforming to government policies and large-scale plans. The lower accessibility problem score in the single-family dwelling is largely related to many problems entering the dwelling being avoided, as there is no need for automatic door construction, elevator, etc., which potentially generates many problems in multi-family dwellings. As the single-family dwelling represents a different complexity of problems we decided to use it in the present study as a contrast to multi-family dwellings. It should be noted however, that policy recommendations and potential interventions will likely differ for different types of dwellings and whether a dwelling is rented or owned, as the direct societal responsibility for housing accessibility differs.

Study strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is the use of a valid and reliable measure that quantifies accessibility problems in a way that facilitates comparisons. Accessibility is only one of several aspects of housing that is important for people aging in their homes. However, such detailed and quantifiable information on physical barriers in the housing environment and the magnitude of accessibility problems they may generate is useful, both for physical planning and housing provision purposes at the societal level and for modifications at the individual level.

A further methodological strength is the use of functional profiles, which makes it possible to apply different housing scenarios to large subgroups of the aging population. It should be noted though, that additional research is needed to further validate the methodology with functional profiles. Moreover, the HE mainly addresses environmental barriers in relation to physical functional limitations. As cognitive decline is an important facet of aging, a more qualified way to capture and analyze potential accessibility problems relating to cognitive limitations would strengthen the methodology.

The complexity of the procedure underlying the accessibility problem scores generated by the HE makes the scoring challenging to interpret, but further research efforts to optimize the analysis methodology are in progress (see, e.g. Slaug et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, with the possibility to take P-E interaction into account and make comparisons between different types of dwellings, before and after housing intervention programs, etc. the HE is still a useful tool.

The use of typical dwelling cases can be very helpful, as multi-family dwellings of similar construction and design features can be found in the Swedish housing stock, and the findings based on selected typical dwelling cases can, therefore, be applicable to many dwellings. However, the types of dwellings in the present study were not chosen from a systematic review of the different types of dwellings existing, their prevalence or architectural characteristics. In a recent study by Kaasalainen and Huuhka (Citation2016), a more thorough “typology of flats” was used to examine “mass-customizable” accessibility improvement models. Such an approach of classifying different typical dwellings in the Swedish ordinary housing stock could be instrumental for further research efforts.

Conclusions

This study highlights housing design features that warrant particular attention in relation to the aging population, and delivers research-based input to policymakers, public agencies and housing industry actors involved in housing development and provision to address the problems of the aging housing stock. The results can also be useful in home modification planning. Detailed knowledge on what accessibility problems that can be expected to emerge for people aging in typical dwellings that are common in the ordinary housing stock has the potential to inform future housing policies to better accommodate the aging population.

Acknowledgment

The study was undertaken within the context of the Center for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE), Lund University, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

Susanne Iwarsson and Björn Slaug are the copyright holders and owners of the Housing Enabler (HE) assessment tool and software, provided as commercial products. Marianne Granbom has no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AARP. (2012). 2011 Boomer housing survey. AARP research and strategic analysis. [accessed 2018 Jun]. https://www.aarp.org/home-family/livablecommunities/info-10-2012/boomers-housing-livablecommunities.html.

- Abramsson, M., & Andersson, E. K. (2012). Residential mobility patterns of elderly—leaving the house for an apartment. Housing Studies, 27(5), 582–604.

- Ahrentzen, S., & Tural, E. (2015). The role of building design and interiors in ageing actively at home. Building Research and Information, 43(5), 582–601. 10.1080/09613218.2015.1056336.

- Banks, J., Blundell, R., Oldfield, Z., & Smith, J. P. (2012). Housing mobility and downsizing at older ages in Britain and the United States. Economica, 79(313), 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.2011.00878.x

- Bendayan, R., Cooper, R., Wloch, E. G., Hofer, S. M., Piccinin, A. M., & Muniz-Terrera, G. (2016). Hierarchy and speed of loss in physical functioning: A comparison across older US and English men and women. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(8), 1117–1122.

- Carlsson, G., Schilling, O., Slaug, B., Fänge, A., Ståhl, A., Nygren, C., & Iwarsson, S. (2009). Toward a screening tool for housing accessibility problems: A reduced version of the housing enabler. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28(1), 59–80. doi:10.1177/0733464808315293

- Chang, J. T., Morton, S. C., Rubenstein, L. Z., Mojica, W. A., Maglione, M., Suttorp, M. J., Roth, E. A., & Shekelle, P. G. (2004). Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ, 328(7441), 680–686. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7441.680

- Emanuelsson, R. (2015). Supply of housing in Sweden. Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review, 2, 47–75.

- Gitlin, L. N., Winter, L., Dennis, M. P., Corcoran, M., Schinfeld, S., & Hauck, W. W. (2006). A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(5), 809–816. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x

- Granbom, M., Löfqvist, C., Horstmann, V., Haak, M., & Iwarsson, S. (2014). Relocation to ordinary or special housing in very old age: Aspects of housing and health. European Journal of Ageing, 11(1), 55–65. doi:10.1007/s10433-013-0287-3

- Granbom, M., Iwarsson, S., Kylberg, M., Pettersson, C., & Slaug, B. (2016). A public health perspective to environmental barriers and accessibility problems for senior citizens living in ordinary housing. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 772. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3369-2

- Helle, T., Nygren, C., Slaug, B., Brandt, A., Pikkarainen, A., Hansen, A.-G., Pétursdórttir, E., & Iwarsson, S. (2010). The Nordic Housing Enabler: Inter-rater reliability in cross-Nordic occupational therapy practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17(4), 258–266. doi:10.3109/11038120903265014

- International Council for Building Research, Studies and Documentation. (1965). Towards industrialised building. Proceedings of the Third CIB Congress, Copenhagen. Amsterdam: Elsevier..

- Iwarsson, S., Haak, M., & Slaug, B. (2012). Current developments of the Housing Enabler methodology. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(11), 517–521. doi:10.4276/030802212X13522194759978

- Iwarsson, S., Horstmann, V., Carlsson, G., Oswald, F., & Wahl, H.-W. (2009). Person–environment fit predicts falls in older adults better than the consideration of environmental hazards only. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(6), 558–567. doi:10.1177/0269215508101740

- Iwarsson, S., Horstmann, V., & Slaug, B. (2007). Housing matters in very old age—yet differently due to ADL dependence level differences. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14(1), 3–15. doi:10.1080/11038120601094732

- Iwarsson, S., Nygren, C., & Slaug, B. (2005). Cross-national and multi-professional inter-rater reliability of the Housing Enabler. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(1), 29–39. doi:10.1080/11038120510027144

- Iwarsson, S., & Slaug, B. (2010a). Housing Enabler — a method for rating/screening and analysing accessibility problems in housing. Veten & Skapen HB and Slaug Enabling Development.

- Iwarsson, S., & Slaug, B. (2010b). The Housing Enabler Screening Tool — brief manual. Veten & Skapen HB and Slaug Enabling Development.

- Iwarsson, S., Wahl, H.-W., Nygren, C., Oswald, F., Sixsmith, A., Sixsmith, J., Széman, Z., & Tomsone, S. (2007). Importance of the home environment for healthy aging: Conceptual and methodological background of the European ENABLE-AGE Project. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 78–84. doi:10.1093/geront/47.1.78

- Kaasalainen, T., & Huuhka, S. (2016). Accessibility improvement models for typical flats: Mass-customizable design for individual circumstances. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 30(3), 271–294. doi:10.1080/02763893.2016.1198739

- Kramer, C., & Pfaffenbach, C. (2016). Should I stay or should I go? Housing preferences upon retirement in Germany. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(2), 239–256. doi:10.1007/s10901-015-9454-5

- Krauth, J., & Lienert, G. A. (1982). Fundamentals and modifications of configural frequency analysis (CFA). Studia Psychologica, 24(3–4), 283–292.

- Kylén, M., Schmidt, S. M., Iwarsson, S., Haak, M., & Ekström, H. (2017). Perceived home is associated with psychological well-being in a cohort aged 67–70 years. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 239–247. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.04.006

- Lien, L. L., Steggell, C. D., Slaug, B., & Iwarsson, S. (2016). Assessment and analysis of housing accessibility: Adapting the environmental component of the housing enabler to United States applications. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(3), 565–580. doi:10.1007/s10901-015-9475-0

- Mahler, M., Sarvimäki, A., Clancy, A., Stenbock-Hult, B., Simonsen, N., Liveng, A., Zidén, L., Johannessen, A., & Hörder, H. (2014). Home as a health promotion setting for older adults. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42 (15_suppl), 36–40. doi:10.1177/1403494814556648

- Malmgren Fänge, A., Lindberg, K., & Iwarsson, S. (2013). Housing adaptations from the perspectives of Swedish occupational therapists. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(3), 228–240. doi:10.3109/11038128.2012.737368

- National Board of Health and Welfare (2016). Statistik om särskilt boende [Statistics on special housing]. Socialstyrelsen. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/20404/2016-12-5.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Oswald, F., Wahl, H.-W., Schilling, O., Nygren, C., Fange, A., Sixsmith, A., Sixsmith, J., Szeman, Z., Tomsone, S., & Iwarsson, S. (2007). Relationships between housing and healthy aging in very old age. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 96–107. doi:10.1093/geront/47.1.96

- Pega, F., Kvizhinadze, G., Blakely, T., Atkinson, J., & Wilson, N. (2016). Home safety assessment and modification to reduce injurious falls in community-dwelling older adults: Cost-utility and equity analysis. Injury Prevention, 22(6), 420–426. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2016-041999

- Pettersson, C., Slaug, B., Granbom, M., Kylberg, M., & Iwarsson, S. (2017). Housing accessibility for senior citizens in Sweden: Estimation of the effects of targeted elimination of environmental barriers. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, published online 24 January 2017. doi:10.1080/11038128.2017.1280078

- Public Housing in Sweden. (2018). 1946–1975 Allmännyttan byggs ut och bostadsbristen byggs bort [1946–1975 Public housing is expanded and housing shortage is resolved]. https://www.allmannyttan.se/historia/historiska-epoker/1946-1975-allmannyttan-byggs-ut-och-bostadsbristen-byggs-bort/ (accessed November 2018)

- SCB Statistics Sweden [SCB]. (2010). Bostads- och byggnadsstatistisk årsbok 2010 [Housing and Building Statistics Yearbook 2010]. Statistiska Centralbyrån. http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/bo0801_2010a01_br_bo01br1001.pdf (accessed June 2017)

- SCB Statistics Sweden [SCB]. (2017). Statistikdatabasen [Statistical database]. Statistiska Centralbyrån. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__HE__HE0111/HushallT21B/?rxid=fd6c5059-87d3-42fd-adeb-21503286413a (accessed June 2017)

- Slaug, B. (2012). Exploration and development of methodology for accessibility assessments: based on the notion of person-environment fit [Doctoral Dissertation] Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, pp. 22–24.

- Slaug, B., Iwarsson, S., & Björk, J. (2019). A new approach for investigation of person-environment interaction effects in research involving health outcomes. European Journal of Ageing, 16(2), 237–247. doi:10.1007/s10433-018-0480-5

- Slaug, B., Schilling, O., Haak, M., & Rantakokko, M. (2016). Patterns of functional decline in very old age: An application of latent transition analysis. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(2), 267–275. doi:10.1007/s40520-015-0394-4

- Slaug, B., Schilling, O., Iwarsson, S., & Carlsson, G. (2011). Defining profiles of functional limitations in groups of older persons: How and why? Journal of Aging and Health, 23(3), 578–604. doi:10.1177/0898264310390681

- Stark, S., Keglovits, M., Arbesman, M., & Lieberman, D. (2017). Effect of home modification interventions on the participation of community-dwelling adults with health conditions: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 7102290010p1–7102290010p11. doi:10.5014/ajot.2017.018887

- Stineman, M. G., Xie, D., Streim, J. E., Pan, Q., Kurichi, J. E., Henry-Sánchez, J. T., Zhang, Z., & Saliba, D. (2012). Home accessibility, living circumstances, stage of activity limitation, and nursing home use. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(9), 1609–1616. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.027

- Swedish National Audit Office. (2014). Bostäder för äldre i avfolkningsorter RIR 2014:2 [Housing for older people in depopulation areas RIR 2014:2]. Riksrevisionen. https://www.riksrevisionen.se/download/18.78ae827d1605526e94b2fe48/1518435442633/RiR_2014_2_%C3%84ldres%20boende_anpassad.pdf (accessed June 2018).

- Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. (2000). Handbook on Housing Adaptation Grants in Sweden. Boverket.

- Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. (2011). Boverkets byggregler BFS 2011: 26 BBR19 [Swedish Building Regulations BFS 2011: 26 BBR19]. Boverket. http://www.boverket.se/sv/lag–ratt/forfattningssamling/gallande/bbr—bfs-20116/ (accessed June 2017)

- Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning. (2016). Bostadsanpassningsbidragen 2015 [Housing Adaptation Grants 2015]. Boverket. http://www.boverket.se/globalassets/publikationer/dokument/2016/bostadsanpassningsbidragen-2015.pdf (accessed June 2017)

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2015). World population ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390).

- Wahl, H.-W., Fänge, A., Oswald, F., Gitlin, L. N., & Iwarsson, S. (2009). The home environment and disability-related outcomes in aging individuals: What is the empirical evidence? The Gerontologist, 49(3), 355–367.

- Verbrugge, L. M., & Jette, A. M. (1994). The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 38(1), 1–14. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1

- Verbrugge, L. M., Latham, K., & Clarke, P. J. (2017). Aging with disability for midlife and older adults. Research on Aging, 39(6), 741–777. doi:10.1177/0164027516681051

- World Health Organization. (2003). WKC International Symposium: Cities and health: Achievements with WKC Partner Cities. Proceedings of a WKC International Symposium, 29 November 2002, Kobe, Japan.