Abstract

An overview of housing assessment tools developed or adapted for research use in East and Southeast Asia is currently lacking. A scoping review was conducted to address this knowledge gap. PubMed, Web of Science and CINAHL were searched for relevant scientific literature, and 22 articles were selected. Besides study-specific checklists, two assessment tools validated for use in Asia and three validated in other countries were identified. The tools were limited in scope and mostly concerned potential injury hazards. Issues such as indoor temperature and housing accessibility also need to be included to comprehensively assess the home environment in Asian countries.

Introduction

The populations of Japan and several other Asian countries are rapidly aging. Especially, for some East and Southeast Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, and Singapore it has been estimated that the aging rate will increase much faster compared to most other countries (Cabinet Office Government of Japan, Citationn.d.). Older adults and those who age with disabilities or chronic illnesses spend most of their time in their homes (Baker et al., Citation2007). Therefore, to maintain tenable “Aging in Place” policies, it is critical to provide appropriate home environments that support activity and independence of older adults, even as their functional capacity is reduced with age. Furthermore, scientifically validated assessment tools are needed to support an evidence-based approach when designing interventions or taking other measures that target the physical home environment.

Supported by existing scientific evidence, stemming from empirical and interventional studies regarding effects of home environments on older adults’ health, WHO launched the “Housing and health guidelines” in 2018 (WHO, Citation2018a). These guidelines focused on reducing health risk factors in five prioritized areas: 1/“inadequate living space (i.e. crowding)”, 2/“low indoor temperature”, 3/“high indoor temperature”, 4/“injury hazards in the home”, and 5/“accessibility (i.e. housing accessibility)”. Housing accessibility concerns the extent to which features in the home environment facilitates or hinders the individual to approach, enter or use it. In the scientific literature, there is compelling evidence indicating that the level of housing accessibility is related to the ability to perform Activities of Daily living (ADL) independently and to maintain a good Quality of Life (QOL) among older adults (Iwarsson & Isacsson, Citation1998; Iwarsson et al. Citation1998). Moreover, previous research has shown that targeted home adaptations may significantly lower the incidence of falls and fall related injuries (Keall et al., Citation2015). However, most of this research used guidelines or assessment tools targeting home environments for older adults that were developed and scientifically validated in the same countries as the studies were carried out. Studies of impacts of the home environment on health have thus mainly been conducted in Europe, U.S.A., and Oceania (Pettersson et al., Citation2020), and the empirical evidence from East and Southeast Asia is thus limited. The characteristics of the home environment vary worldwide, and are closely related to the local culture, climate and lifestyle (Muramatsu et al., Citation1999; Romli, Mackenzie, et al., Citation2017). For example, in contrast to traditional European homes, traditional homes in Japan often have multiple floors to compensate for limited space, narrow hallways and stairs, and bathing rooms that are separated from the toilet (Makigami & Pynoos, Citation2002). Therefore, it is essential to develop housing assessment tools and evaluation indicators that take cultural specifics into account for valid research and an evidence-based approach to policy recommendations targeting the home environment in Asian countries. That is, assessment tools developed in Europe or North America may miss important environmental aspects of the home environment in East or South East Asian countries, or overemphasize other aspects that are not relevant in these countries. To gather information on existing housing assessment tools developed and used in East and South East Asia is a way to identify knowledge gaps and the specific needs for a housing assessment tool to be validly and reliably used in these countries in future studies.

The overarching aim of the current study was to provide a comprehensive overview of housing assessment tools or study-specific checklists developed or adapted for research use in East and Southeast Asia. Specific aims were to describe the purpose and the measures taken to strengthen validity and reliability of housing assessment tools or checklists and to elucidate the concepts captured by means of the WHO housing and health guidelines.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a scoping review to achieve a comprehensive overview of existing housing assessment tools developed or adapted for use in East and Southeast Asian countries. We followed the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018) in this procedure.

We selected the target countries and areas from East Asia and Southeast Asia in accordance with the classification by the United Nations (United Nations Statistics Division, Citationn.d.). East Asia thus includes China, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, and Mongolia. Southeast Asia includes Indonesia, Philippines, Viet Nam, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, Thailand, Myanmar, and Timor-Leste.

Eligibility and exclusion criteria

We selected peer-reviewed articles (including reviews and guidelines) from the target countries concerning housing assessment tools or evaluations of the home environment for people with disabilities, as eligible for the scoping review. Exclusion criteria were: (1) children were the only subjects, (2) article was not available in English, (3) article was not reporting original research, and (4) abstract and main text were not available. Though we focused on older adults with disability, we included some studies with community-dwelling people with disability that were not limited to older adults. In this context we defined disabilities as “impairments in body function and body structures, limitations in activities, and restrictions in participation” in accordance with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF Research Branch, Citation2012).

Search terms

We used PubMed, Web of Science and CINAHL in a systematic search of peer-reviewed articles published up to 25th January in 2019. Key words were used in different combinations to capture relevant literature concerning housing, housing adaptations and geographical areas. The actual search terms used were “housing[MeSH]” or (“accommodation*” or “Built environment*” or “Environmental barriers*” or “Environmental hazard*” or “home*” or “home environment*” or “home hazards, housing” or “residential*” or “dwelling*”) and ("home adaptation*” or “home hazards*” or “home intervention*” or “home modification*” or “home repair*” or “housing adaptation*”) and “(Korea* OR Japan* OR Mongolia* OR Hong Kong* OR Taiwan* OR China OR Macau* OR Brunei* OR Cambodia* OR Indonesia* OR Lao OR Malaysia* OR Myanmar* OR Philippin* OR Singapore* OR Thai* OR Timor-Leste* OR Vietnam* or Asia*)”.

Selection procedure

The articles identified in the literature search included both psychometric studies of assessment tools and empirical studies on housing environment and health, conducted in the target countries of East and Southeast Asia. After removing duplicates, two researchers with expertise in housing assessment methodology conducted a title, abstract, and full-text review independent of each other, during which eligibility and exclusion criteria were checked. In an iterative process, the two researchers then compared their independent reviews, and made final decisions on selection based on consensus discussions.

Study selection

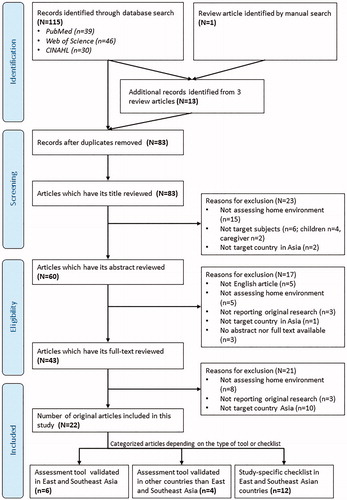

Through the systematic search, we identified 115 records, including two review articles (Hill et al., Citation2018; Puts et al., Citation2017). An additional review article was identified by a manual search (Romli, Tan, et al., Citation2017). From these three review articles, 13 additional articles examining environmental housing aspects were identified. After duplicates were removed, 83 records remained that were reviewed on the basis of title. Based on the title review, 23 articles were excluded. Of the remaining 60 articles, 17 were excluded through abstract review. Full-text reviews were conducted for 43 articles, which resulted in a further 21 articles excluded. A total of 22 articles were included in the final review. The process of study selection is illustrated with a PRISMA adapted flow-chart in .

Study analysis

We began the study analysis by extracting all information related to the housing assessment tools used in the 22 final review articles. The content of the articles was organized by name of authors, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, study design, study aim, characteristics of participants, number of participants and housing assessment tool used. This process was jointly developed by two researchers to determine which variables to extract. The two researchers independently charted the data, discussed the results and continuously updated the data charting from an interactive process. Subsequently, we sorted the housing assessment tools into three groups (A, B and C) in the following way: Group A/“Housing assessment tools scientifically validated for the East or Southeast Asian countries”, Group B/“Housing assessment tools scientifically validated or published as guidelines for countries other than East or Southeast Asian countries”, and Group C/“Housing assessment items developed by researchers in East and Southeast Asian countries”. After that, we performed a qualitative content analysis of the items in Group C in order to elucidate the concepts captured. To do so, we classified the items into categories based on their similarities. Then we checked whether each category could be considered to capture any of the concepts related to health risk factors in the housing environments focused by the WHO Housing and health guidelines (WHO, Citation2018a): 1/“inadequate living space (i.e. crowding)”, 2/“low indoor temperature”, 3/“high indoor temperature”, 4/“injury hazards in the home”, and 5/“accessibility (i.e. housing accessibility)”. These concepts cover prioritized areas where robust scientific evidence of the importance for different aspects of health is already available (WHO, Citation2018a). “Inadequate living space (crowding)” is defined as a condition where the number of occupants exceed the capacity of the dwelling space available. “Injury hazards” includes if there are risks of falls, burns, poisonings, ingestion of foreign objects, smoke inhalation, drowning, cuts or collisions with objects and crushing and fractured bones as a result of structural collapse. “Housing accessibility” does not have an exact definition in the WHO guidelines; we therefore decided to define it according to a standard dictionary (Cambridge University Press, Citation2018) as “the quality or characteristic of something that makes it possible to approach, enter, or use it”. We combined the two temperature areas (“low indoor temperature” and “high indoor temperature”) because features related to temperature (such as poor ventilation) often affect both low and high indoor temperature. Consequently, we considered four key concepts based on the WHO guidelines: 1/“Inadequate living space (crowding)”, 2/“low/high indoor temperature”, 3/“injury hazards”, and 4/“housing accessibility”. The classification and comparison with the WHO concepts was first conducted by one of the researchers and then independently verified by another.

Ethical approval

We did not obtain approval from an ethics committee for this study, as it is a review of published papers, using only secondary data.

Results

The selection procedure resulted in a final inclusion of 22 articles (Chin et al., Citation2013; de Guzman et al., Citation2013; Eshkoor et al., Citation2013; Hasegawa & Kamimura, Citation2018; Kamei et al., Citation2015; Kittipimpanon et al., Citation2012; Lai et al., Citation2019; Lee & Yoo, Citation2015; Leung, Citation2019; Lin et al., Citation2007; Matchar et al., Citation2019, 2017; Mitoku & Shimanouchi, Citation2014; Pattaramongkolrit et al., Citation2013; Rizawati & Mas Ayu, Citation2008; Romli et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Romli, Mackenzie, et al., Citation2017; Sophonratanapokin et al., Citation2012; Sukkay, Citation2016; Tan et al., Citation2018; Tongsiri et al., Citation2017). A summary of the included articles is shown in .

Table 1. Summary of the selected articles and sorting of assessment tools identified.

Housing assessment tools identified

In six of the 22 articles, two housing assessment tools scientifically validated in East or Southeast Asian countries (Group A) were identified: Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME-FAST) (Mackenzie et al., Citation2000), and Westmead Home Safety Assessment (WeHSA) (Clemson et al., Citation2010; Integrated solutions for sustainable fall prevention, Citation2018). Four articles used housing assessment tools scientifically validated in other than East and Southeast Asian countries (Group B) in studies conducted in Japan and Singapore. Three of these four articles reported randomized control studies for fall prevention, and used a CDC home checklist developed in the United States (Kamei et al., Citation2015; Matchar et al., Citation2019, Citation2017). Two other identified tools, “Safety house checklist” (Carter et al., Citation1997) and “Home-screen scale” (Johnson et al., Citation2001), were developed in Australia and used in a study in Malaysia (Rizawati & Mas Ayu, Citation2008). One other identified tool, “Environmental checklist” (Northridge et al., Citation1995), was developed in the United States. All four tools were used for the purpose of detecting environmental hazards to prevent falls. In total six different housing assessment tools were identified, but only two were validated for use in East or Southeast Asia. For further details, see .

Measures taken to develop or adapt housing assessment tools for valid and reliable use in Asia

For basic information in terms of geographical area, purpose and psychometric evaluation of the two housing assessment tools scientifically validated in East or Southeast Asian countries (Group A), see . HOME-FAST and WeHSA were originally developed in Australia and adapted for use in Asian countries. Some revisions were made regarding cultural differences, and we summarized these in . Both tools were developed to reduce fall risks by assessing environmental hazards.

Table 2. Basic information of housing assessment tools scientifically validated for the East or Southeast Asian countries.

Table 3. Revised items based on cultural differences in HOME FAST and WeHSA.

The HOME-FAST was developed to measure fall risks for older people within their home environment (Mackenzie et al., Citation2000). The reliability (Vu & Mackenzie, Citation2012), predictive validity (Mackenzie et al., Citation2009), responsiveness (Mackenzie et al., Citation2009), and clinical utility (Mackenzie, Citation2017) have been evaluated with satisfactory results. The HOME-FAST has been translated into Malaysian (Romli et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Romli, Mackenzie, et al., Citation2017; Tan et al., Citation2018) and Hong Kong versions(Lai et al., Citation2019). In the Malaysian version, the items were not changed from the original, but the reliability, cross-cultural validity (Romli, Mackenzie, et al., Citation2017) and feasibility (Romli et al., Citation2016) were still examined with satisfactory results. In the Hong Kong version, through a revision process, some original items were merged to be more easily understood by older adults when written in Chinese. Some items were also deleted because they were not relevant to the crowded living environment in Hong Kong. This study also confirmed sufficient reliability, content and factorial validity, as well as clinical utility (Lai et al., Citation2019).

The WeHSA was developed as a tool for occupational therapists to identify environmental hazards in the homes of older persons who are at risk of falling (Hasegawa & Kamimura, Citation2018). The original version has been evaluated as a reliable tool (Clemson et al., Citation2010; Clemson, Fitzgerald, Heard, et al., Citation1999) and there is evidence supporting the content validity (Clemson, Fitzgerald, & Heard, Citation1999). The original WeHSA was modified and translated to a Japanese version by Hasegawa et al. (Hasegawa & Kamimura, Citation2018), and in the revision process, original items such as “seating” and “bed” were adapted to the Japanese specific conditions of sitting on a cushion and sleeping on a futon in tatami room. Also, some of the expressions were changed to suit Japanese housing design (e.g. “Bath” was changed to “Bathing room/Dressing room”). In this Japanese version, after examining the reliability and content validity, 49 items were considered to be appropriate (Hasegawa & Kamimura, Citation2018).

Study-specific checklist items

Twelve articles used study-specific checklist items developed by researchers in East and Southeast Asia (Group C). The countries/areas and number of articles were; Singapore: 1 (Chin et al., Citation2013), Philippine: 1 (de Guzman et al., Citation2013), Malaysia: 1 (Eshkoor et al., Citation2013), Thailand: 5 (Kittipimpanon et al., Citation2012; Muangpaisan et al., Citation2015; Sophonratanapokin et al., Citation2012; Sukkay, Citation2016; Tongsiri et al., Citation2017), South Korea: 1 (Lee & Yoo, Citation2015), Hong Kong: 1 (Leung, Citation2019), Taiwan: 1 (Lin et al., Citation2007), and Japan: 1 (Mitoku & Shimanouchi, Citation2014). In , the development processes of these study-specific items are summarized. Seven articles referred to previous publications for the item development, and seven referred to expert advice. The items developed were mainly used for the purpose of evaluating home hazards related to fall issues or occurrence of accidents. In three articles the stated purpose was related to home modifications (Mitoku & Shimanouchi, Citation2014; Sukkay, Citation2016; Tongsiri et al., Citation2017). As shown in , a total of 80 items developed by researchers in East and Southeast Asia were identified. Items from five articles were not included because the items concerned housing adaptations and we could not decide the reason for implementing these housing adaptations such as installation of handrails (Mitoku & Shimanouchi, Citation2014; Sukkay, Citation2016; Tongsiri et al., Citation2017), or because we could not obtain English translations of the items (Kittipimpanon et al., Citation2012; Pattaramongkolrit et al., Citation2013).

Table 4. Purpose and developing process of the housing assessment items developed by researchers in East and Southeast Asian countries.

Item classification and key housing concepts captured

There were 14 items that did not concern the housing environment, e.g. problems of inappropriate footwear, use of walking aids or individual behaviors. As a result, 66 of the 80 items identified were considered in the comparison with the WHO concepts. The cross-tabulation of Group C items and comparison with the four key concepts in the WHO housing and health guidelines (WHO, Citation2018a) is provided in . The items were classified into nine main categories: “(1) Building layout issues”, “(2) Structural problems of facilities or furniture”, “(3) Broken facilities or furniture”, “(4) Facilities or switches difficult to use”, “(5) Slippery flooring or carpets”, “(6) Clutter”, “(7) Low visibility”, “(8) Lack of appliances or facilities for safe”, and “(9) Environmental health”. Almost all items were related to the WHO concepts “Injury hazards” (61 items) and “Housing accessibility” (61 items). The concept of “Low/high indoor temperature” was related to three categories (13 items), while the concept of “Inadequate living space” related to only one category (5 items). The categories with most items were “Structural problems of facilities or furniture”, “Slippery flooring or carpets”, “Low visibility”, “Clutter”, and “Lack of appliances or facilities for safe”.

Table 5. Classification of the housing assessment items and comparison with the risk factors as set forth in the WHO Housing and Health guidelines and previous review.

Summary of results

The findings of this scoping review revealed that there were a few housing assessment tools that were used in the 22 articles. There was not a single tool that was originally developed in East or Southeast Asia, but two (HOME-FAST and WeHSA) were adapted and scientifically validated for use in Asian countries. Four other tools were used, two American (CDC home checklist and Environmental checklist) and two Australian (Safety house checklist and Home-screen scale), despite not being validated for use in Asian countries. All of these tools were primarily focused only on one of the areas of health risks in the home environment prioritized by the WHO, that is injury hazards and fall prevention. Several articles reported the use of study-specific checklists to assess the home environment. A content analysis of these study-specific checklists showed that the items included mainly concerned injury hazards and housing accessibility, and in a few cases indoor temperature and just in one instance inadequate living space. However, it was also found that the items were developed in a manner that was not scientifically rigorous.

Discussion

Limited scope of housing assessment tools at use in East and Southeast Asia

According to our review there are only two housing assessment tools that have been tested for both reliability and validity in the Asian context in a scientific manner, the HOME-FAST and the WeHSA. The purpose of both these assessment tools is to detect environmental hazards and to prevent falls. Moreover, the additional tools we found that had been used in studies in Asia without testing the psychometric properties in the new cultural context (the CDC home checklist, the Safety house checklist and the Home-screen scale), also concerned fall prevention and detection of environmental hazards. Indeed, over 80% of fall-related fatalities occur in low- and middle-income countries, with regions of the Western Pacific and South East Asia accounting for 60% of these deaths (WHO, Citation2018b). For Asian countries, with a drastic increase in the number of older adults, fall prevention is certainly crucial if aging-in-place policies are to be tenable. Nonetheless, injury hazards are only one of the WHO prioritized areas, suggesting a need for housing assessment tools addressing the other prioritized areas, that is, inadequate living space, low/high indoor temperature and housing accessibility.

Injury hazards and housing accessibility

With few fully developed tools found, we also scrutinized articles using study-specific checklists in order to examine the extent to which each of the WHO key concepts were captured by these. Most of the items included also assessed injury hazards for fall prevention purposes. However, it should be noted that other indoor accidents such as fire and drowning to some extent are also possible to prevent by checking environmental hazards and implementing housing adaptations/home modifications; this appeared not to be considered in the items we found. A substantial number of items concerned aspects of housing accessibility. Besides reducing fall risks, an accessible housing environment is expected to maximize the ability of older adults to stay independent in activities of daily living (Iwarsson et al., Citation1998) and to contribute to higher quality of life (Iwarsson & Isacsson, Citation1998b). Yet, though encouraging to find study-specific items used, in accordance with a previous systematic review (Patry et al., Citation2019) we did not identify any fully developed assessment tool addressing housing accessibility, even though recent research shows serious accessibility issues in Asian countries (Kobayashi et al., Citation2019). There is therefore an urgent need to include measures of accessibility in housing assessment tools in order to address health risk factors in this WHO prioritized area.

Inadequate living space and indoor temperature

Among the 80 items identified, very few were related to health risk factors of inadequate living space. This is striking as Southeast Asia has been reported as an area characterized by many overcrowded countries (UN-Habitat, Citation2006). However, crowding can be objectively estimated from the national data, and some cross-national indexes have already been developed (WHO, Citation2018a) that could be useful as complement to housing assessments. Low/high indoor temperature was captured by several items. The WHO reported that a minimum indoor temperature higher than 18 °C may be necessary for vulnerable groups, including older people (WHO, Citation2018a). On the other hand, such recommendations could be inadequate for some parts of Asian countries, because these are located in tropical regions. Still, too low indoor temperature has been shown to increase the risk of falls (Hayashi et al., Citation2017) and to affect well-being by worsening of subjective health (Tsuchiya-Ito et al., Citation2019). In addition, the risk of heat stroke increases due to the effects on temperature by global warming these days (Sun et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we consider it necessary to develop items or measures that appropriately captures aspects of indoor temperature that may be harmful, to support actions and policies addressing such issues and ultimately contribute to the well-being of older adults.

The impact of cultural specifics

Notable in the classification of study-specific items was that one of the largest categories (i.e. 8 items) concerned clutter. In comparison, a recent scoping review of physical barriers and enablers in ordinary housing for older people in care, did not mention such issues at all (Pettersson et al., Citation2020). Characteristically, the review by Pettersson and colleagues did not include any studies from East or Southeast Asia, which could be seen as further supporting the need for housing assessment tools specifically developed to match the situation in Asian countries. Previous research has pointed to clutter as a risk factor for falls (Lee & Yoo, Citation2015) and low self-rated health (Tsuchiya-Ito et al., Citation2019). This suggests that clutter may be important to include, when developing assessment tools for Asian countries or adapting assessment tools developed for countries other than Asian.

The adaptation of the Australian assessment tools for use in Malaysia (HOME-FAST), Hong Kong (HOME-FAST) and Japan (WeHSA) also reveals issues of importance to consider when adapting a tool for another cultural context. Though HOME-FAST was just translated without modifications of the content for the Malaysian studies, in the Hong Kong version some items were removed or modified due to cultural specifics. It was surprising however, that most of the items developed in Australia could be validly used in Malaysia and Hong Kong, even though Romli et al. (Citation2016) asserted that HOME-FAST was developed to minimize cultural impact and allow universal application. It should be kept in mind though, that these three countries all have historic ties to the United Kingdom, which may explain some cultural similarities. In contrast, when WeHSA was adapted for use in Japan, it was considerably modified to account for common Japanese customs and housing designs, such as level differences at the entrance for placing shoes, seating on the floor (tatami), and lying on the futon mattress instead of a bed. These specifics impact the layout and characteristics of homes in Japan, and home modification techniques developed in Europe or North America can therefore not be directly applied (Makigami & Pynoos, Citation2002). It should be emphasized that such modifications of an original instrument always requires renewed psychometric testing before it can be validly and reliably used. In case of the Japanese WeHSA this was done with satisfying results. In a similar manner, when assessment tools are applied in another culture than it was originally developed for, it may cause confusion in practical assessment situations (Romli et al., Citation2016). Complementary instructions may therefore be needed to ensure reliable use. To summarize, the adaptability of assessment tools requires careful consideration of historical and cultural backgrounds, and it is important to respect the specifics of each Asian country and examine the feasibility and cross-cultural adaptability in detail.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this scoping review is that by revealing the lack of housing assessment tools in East and Southeast Asia and the limited scope of those that have been used, it points to specific knowledge gaps where further research and development is needed. The comparison of study-specific items with the WHO guidelines is particularly useful to identify areas of importance for housing assessments tools to cover in order to be comprehensive. The examination of impacts by cultural specifics can aid future processes both of adaptation of existing assessment tools and the development of new assessment tools for use in Asian countries.

There are two study limitations that need to be mentioned. First, we did not select articles where a housing environment assessment was included only as complementary, and not serving a main study objective. Part of the aim of this scoping review was to examine the purpose of housing assessment tools, which was not feasible for such articles. Second, the selection process did not include articles written in other languages than English. Especially in East Asia, there are few countries where English is the official language, so it might be possible to find more material if a search is conducted without language restriction.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review of housing assessment tools in East and Southeast Asian countries. We found that scientifically validated housing assessment tools in Asia are few and mostly developed for the limited purpose of fall prevention and environmental hazards identification. Moreover, we found that study-specific checklists used are likewise limited in scope and often developed in a way that is not scientifically rigorous. To comprehensively assess health risk factors of the home environment it is imperative to consider not only injury hazards but also other environmental aspects focused by the WHO as prioritized areas, particularly concerning issues of indoor temperature and housing accessibility. In addition, when developing or adapting housing assessments tools for valid use in Asian countries, it is necessary to carefully consider the potential impact of specifics of Asian culture and housing design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baker, M., Keall, M., Au, E. L., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2007). Home is where the heart is–most of the time. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 120(1264), U2769. https://search.proquest.com/openview/680cd8e4ca66ff9afef68d5c344a0f7f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1056335

- Cabinet Office Government of Japan. (n.d). Heisei30nen Kousei roudou hakusyo-Koureikano kokusaiteki doukou [White Paper 2018-International trends of ageing]. Cabinet Office Government of Japan. Retrieved December 16, 2019, from https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2018/html/zenbun/s1_1_2.html.

- Cambridge University Press. (2018). Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/ja/dictionary/english/accessibility

- Carter, S. E., Campbell, E. M., Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Redman, S., & Gillespie, W. J. (1997). Environmental hazards in the homes of older people. Age and Ageing, 26(3), 195–202. https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article-abstract/26/3/195/35978.

- Chin, L. F., Wang, J. Y. Y., Ong, C. H., Lee, W. K., & Kong, H. K. (2013). Factors affecting falls in community-dwelling individuals with stroke in Singapore after hospital discharge. Singapore Medical Journal, 54(10), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2013202.

- Clemson, L., Fitzgerald, M. H., & Heard, R. (1999). Content validity of an assessment tool to identify home fall hazards: The Westmead Home Safety Assessment. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(4), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269906200407.

- Clemson, L., Fitzgerald, M. H., Heard, R., & Cumming, R. G. (1999). Inter-rater reliability of a home fall hazards assessment tool. The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 19(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944929901900201.

- Clemson, L., Roland, M., & Cumming, R. (2010). Occupational therapy assessment of potential hazards in the homes of elderly people: An inter-rater reliability study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 39(3), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.1992.tb01753.x.

- de Guzman, A. B., Garcia, J. M. G., Garcia, J. P. S. P., Garcia, M. B., German, R. T., Gerong, M. S. C., & Grajo, A. J. B. (2013). A multinomial regression model of risk for falls (RFF) factors among Filipino elderly in a community setting. Educational Gerontology, 39(9), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2012.661338.

- Eshkoor, S. A., Hamid, T. A., Nudin, S. S. A. H., & Mun, C. Y. (2013). The effects of sleep quality, physical activity, and environmental quality on the risk of falls in dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr, 28(4), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513488921.

- Hasegawa, A., & Kamimura, T. (2018). Development of the Japanese version of the Westmead Home Safety Assessment for the elderly in Japan. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1569186118764065.

- Hayashi, Y., Schmidt, S., Malmgren Fänge, A., Hoshi, T., & Ikaga, T. (2017). Lower physical performance in colder seasons and colder houses: Evidence from a field study on older people living in the community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060651.

- Hill, K. D., Suttanon, P., Lin, S.-I., Tsang, W. W. N., Ashari, A., Hamid, T. A. A., Farrier, K., & Burton, E. (2018). What works in falls prevention in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0683-1.

- ICF Research Branch. (2012). ICF core sets-manual for clinical practice. In J. Bickenbach, A. Cieza, A. Rauch, & G. Stucki (Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing.

- Integrated Solutions for Sustainable Fall Prevention. (2018). Falls prevention-online workshops. Retrieved January 14, 2020, from https://fallspreventiononlineworkshops.com.au/resources/#allied

- Iwarsson, S., Isacsson, Å., & Lanke, J. (1998). ADL dependence in the elderly population living in the community: The influence of functional limitations and physical environmental demand – ProQuest. Occupational Therapy International, 5(3), 173–193. http://search.proquest.com/openview/29b6e58ffafb5e8b3c81a0abc74b3950/1?pq-origsite=gscholar.

- Iwarsson, S., & Isacsson, Å. (1998). Quality of life in the elderly population: an example exploring interrelationships among subjective well-being, ADL dependence, and housing accessibility. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 26(1), 71–83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18653127.

- Johnson, M., Cusick, A., & Chang, S. (2001). Home‐screen: A short scale to measure fall risk in the home. Public Health Nursing, 18(3), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00169.x.

- Kamei, T., Kajii, F., Yamamoto, Y., Irie, Y., Kozakai, R., Sugimoto, T., Chigira, A., & Niino, N. (2015). Effectiveness of a home hazard modification program for reducing falls in urban community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Japan Journal of Nursing Science: JJNS, 12(3), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12059.

- Keall, M. D., Pierse, N., Howden-Chapman, P., Cunningham, C., Cunningham, M., Guria, J., & Baker, M. G. (2015). Home modifications to reduce injuries from falls in the home injury prevention intervention (HIPI) study: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet), 385(9964), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61006-0.

- Kim, E. J., Arai, H., Chan, P., Chen, L. K., Hill, K. D., Kong, B., Poi, P., Tan, M. P., Yoo, H. J., & Won, C. W. (2015). Strategies on fall prevention for older people living in the community: A report from a round-table meeting in IAGG 2013. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics, 6(2), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcgg.2015.02.004.

- Kittipimpanon, K., Amnatsatsue, K., Kerdmongkol, P., Maruo, S. J., Nityasuddhi, D. (2012). Development and evaluation of a community-based fall prevention program for elderly Thais. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res, 16(3), 222–235. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/view/5878/5084

- Kobayashi, M., Sai, T., Uwano, T., Nishizawa, K., Mori, S., Asano, N. & Institute of Developing Economies. (2019). Ajiano syougaisyano akuseshibiritexi housei: baria furi-no genjouto kadai [Accessibility policy for people with disability in Asia: The current situation and challenges] (in Japanese). T. Institute of Developing Economies. Institute of Developing Economies. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB2786220X.bib.

- Lai, F. H. Y., Yan, E. W. H., Mackenzie, L., Fong, K. N. K., S. Kranz, G., Ho, E. C. W., Fan, S. H. U., & Lee, A. T. K. (2019). Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of a self-reported screening tool in the prediction of fall incidence in older adults. Disability and Rehabilitation, 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1582721

- Lee, S. Y., & Yoo, S. E. (2015). Effects of housing conditions and environmental factors on accidents and modification intention of the vision impaired. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 14(2), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.14.347.

- Leung, D. D. M. (2019). Influence of functional, psychological, and environmental factors on falls among community-dwelling older adults in Hong Kong . Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 19(3), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12386.

- Lin, M.-R., Wolf, S. L., Hwang, H.-F., Gong, S.-Y., & Chen, C.-Y. (2007). A randomized, controlled trial of fall prevention programs and quality of life in older fallers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(4), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01146.x.

- Mackenzie, L. (2017). Evaluation of the clinical utility of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST). Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(15), 1489–1501. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1204015.

- Mackenzie, L., Byles, J., & D'Este, C. (2009). Longitudinal study of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool in identifying older people at increased risk of falls. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 28(2), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00361.x/.

- Mackenzie, L., Byles, J., & Higginbotham, N. (2000). Designing the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST): Selecting the Items. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(6), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260006300604.

- Makigami, K., & Pynoos, J. (2002). The evolution of home modification programs in Japan. Ageing International, 27(3), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-003-1004-x.

- Matchar, D. B., Duncan, P. W., Lien, C. T., Ong, M. E. H., Lee, M., Gao, F., Sim, R., & Eom, K. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of screening, risk modification, and physical therapy to prevent falls among the elderly recently discharged from the emergency department to the community: The steps to avoid falls in the elderly study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(6), 1086–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.01.014.

- Matchar, D. B., Eom, K., Duncan, P. W., Lee, M., Sim, R., Sivapragasam, N. R., Lien, C. T., & Ong, M. E. H. (2019). A cost-effectiveness analysis of a randomized control trial of a tailored, multifactorial program to prevent falls among the community-dwelling elderly. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.434.

- Min Lim, L., McStea, M., Wei Chung, W., Nor Azmi, N., Azdiah Abdul Aziz, S., Alwi, S., Kamarulzaman, A., Bahyah Kamaruzzaman, S., Siang Chua, S., & Rajasuriar, R. (2017). Prevalence, risk factors and health outcomes associated with polypharmacy among urban community-dwelling older adults in multi-ethnic Malaysia. PLoS One, 12(3), e0173466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173466.

- Mitoku, K., & Shimanouchi, S. (2014). Home modification and prevention of frailty progression in older adults: A Japanese prospective cohort study. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(8), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20140311-02.

- Muangpaisan, W., Suwanpatoomlerd, S., Srinonprasert, V., Sutipornpalangkul, W., Wongprikron, A., & Assantchai, P. (2015). Causes and course of falls resulting in hip fracture among elderly Thai patients. Chotmaihet Thangphaet [Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand], 98(3), 298–305. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25920301.

- Muramatsu, S., Igarashi, T., Ota, S., Otsuki, T., Kinoshita, H., & Maki, N. (1999). Reading the Asian architecture: trans-architecture/trans-urbanism [in Japanese]. 1st Edition. INAXo.

- Northridge, M. E., Nevitt, M. C., Kelsey, J. L., & Link, B. (1995). Home hazards and falls in the elderly: the role of health and functional status. American Journal of Public Health, 85(4), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.85.4.509

- Patry, A., Vincent, C., Duval, C., & Careau, E. (2019). Psychometric properties of home accessibility assessment tools: A systematic review. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie [Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy], 86(3), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417418824731.

- Pattaramongkolrit, S., Sindhu, S., Thosigha, O., & Somboontanot, W. (2013). Fall-related Factors among older, visually-impaired Thais. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res, 17(2), 181–196.

- Pettersson, C., Malmqvist, I., Gromark, S., & Wijk, H. (2020). Enablers and barriers in the physical environment of care for older people in ordinary housing: A scoping review. Journal of Aging and Environment, 34(3), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2019.1683671.

- Puts, M. T. E., Toubasi, S., Andrew, M. K., Ashe, M. C., Ploeg, J., Atkinson, E., Ayala, A. P., Roy, A., Rodríguez Monforte, M., Bergman, H., & McGilton, K. (2017). Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age and Ageing, 46(3), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw247.

- Rizawati, M., & Mas Ayu, S. (2008). Home environment and fall at home among the elderly in Masjid Tanah Province. Journal of Health and Translational Medicine, 11(2), 72–82.

- Romli, M. H., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., & Tan, M. P. (2016). Pilot study to investigate the feasibility of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST) to identify older Malaysian people at risk of falls. BMJ Open, 6(8), e012048. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012048.

- Romli, M. H., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., Tan, M. P., & Clemson, L. (2017). The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST) in Malaysia: Using raters with a range of professional backgrounds. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 23(3), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12697.

- Romli, M. H., Tan, M. P., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., Kamaruzzaman, S. B., & Clemson, L. (2018). Factors associated with home hazards: Findings from the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research study. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 18(3), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13189.

- Romli, M. H., Tan, M. P., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., Suttanon, P., & Clemson, L. (2017). Falls amongst older people in Southeast Asia: A scoping review. Public Health, 145, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.12.035.

- Sophonratanapokin, B., Sawangdee, Y., & Soonthorndhada, K. (2012). Effect of the living environment on falls among the elderly in Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 43(6), 1537–1547.

- Sukkay, S. (2016). Multidisciplinary procedures for designing housing adaptations for people with mobility disabilities. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 229, 355–362.

- Sun, Q., Miao, C., Hanel, M., Borthwick, A. G. L., Duan, Q., Ji, D., & Li, H. (2019). Global heat stress on health, wildfires, and agricultural crops under different levels of climate warming. Environment International, 128, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.025.

- Tan, P. J., Khoo, E. M., Chinna, K., Saedon, N. I., Zakaria, M. I., Ahmad Zahedi, A. Z., Ramli, N., Khalidin, N., Mazlan, M., Chee, K. H., Zainal Abidin, I., Nalathamby, N., Mat, S., Jaafar, M. H., Khor, H. M., Khannas, N. M., Majid, L. A., Tan, K. M., Chin, A.-V., … Tan, M. P. (2018). Individually-tailored multifactorial intervention to reduce falls in the Malaysian Falls Assessment and Intervention Trial (MyFAIT): A randomized controlled trial. PLOS One, 13(8), e0199219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199219.

- Tongsiri, S., Ploylearmsang, C., Hawsutisima, K., Riewpaiboon, W., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2017). Modifying homes for persons with physical disabilities in Thailand. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(2), 140–145. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.178434.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- Tsuchiya-Ito, R., Slaug, B., & Ishibashi, T. (2019). The physical housing environment and subjective well-being among older people using long-term care services in Japan. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 33(4), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2019.1597803.

- UN-Habitat. (2006). Overcrowding in Asia. Asia-Pacific Ministerial Conference on Housing and Human Settlements. https://mirror.unhabitat.org/documents/media_centre/APMC/Overcrowding in Asia.pdf

- United Nations Statistics Division. (n.d). Methodology-Standard country or area codes for statistical use(M49). United Nations. Retrieved December 16, 2019, from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/overview/

- Vu, T.-V., & Mackenzie, L. (2012). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2012.01012.x.

- WHO. (2018a). WHO Housing and health guidelines. https://www.who.int/sustainable-development/publications/housing-health-guidelines/en/.

- WHO. (2018b). Falls. WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls.