Abstract

This ethnographic study explores an old age home in a former township in Walvis Bay, Namibia as an institution to investigate its potential to be interwoven in community care services for older adults. Interviews with older adults from the community revealed highly negative opinions about the residence that equated it to an institution. These opinions are compared with conditions in the OAH and the residents’ views. The old age home was much more heterogenous as regards the composition of residents than what was perceived by older adults who lived in the community, who considered the home an option only for people who were childless or had been abandoned. Older adults who voluntarily lived alone in the home represented a new lifestyle that challenged the traditional family care practice that is the norm in later life. There was however some truth to the interviewees’ perceptions of coercive elements, both in terms of practices and architectural design. The paper argues that it is necessary to reduce the stigma that prevents residential care from being an accepted part of community care and a housing option in the future. The study result shows a number of potentialities that can contribute to this.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the issue of institutional conditions in housing for older adults in an African urban setting. In recent decades, the ambition in the global north has been to normalize housing conditions for older adults by making them “homelike” and supportive of independent living, even for individuals with great care needs (Regnier, Citation2002; Schwarz & Brent, Citation1999). This issue has been studied less in an African context, not least because few housing alternatives there target older adults. Residential care is even considered an anomaly in an African context, based on the argument that it goes against African core values of family-based care (Aboderin et al., Citation2015; Pype, Citation2016). The main premise for social policy may be that the family is the primary caregiver, and that there is thus no need for institutionalized care facilities or residences adapted to older adults (Hoffman & Pype, Citation2016; Nzima & Maharaj, Citation2020; Oakley, Citation1998). Citizens might not even know that care facilities exist (Chepkwony, Citation2019; Sichingabula, Citation2000).

Research indicates that there is a widespread perception in an African context that old age homes are primarily for childless older adults or older adults whose families do not take care of them, leaving them with no other choice (Hungwe, Citation2011; Madungwe et al., Citation2011; Ncube, Citation2017; Oakley, Citation1998; Pype, Citation2016). Residents are perceived as “worthless people” without power and influence (Chepkwony, Citation2019; Pype, Citation2016). Despite this stigma associated with residential care, social change, in which family care is increasingly put under pressure, requires new housing alternatives for older adults (Nord & Byerley, Citation2017; Nzima & Maharaj, Citation2020). In the light of “profound inadequacies in familial care provision,” Hoffman and Pype (Citation2016, p. 2) argue that there is a growing need for formal community care services.

This paper discusses the potential integration of residential care homes in community services for older adults through a study of an “old age home” (OAH) run by the municipality in Kuisebmond, Walvis Bay in Namibia, which is a former apartheid “township”—a neighborhood for black workers. This OAH opened during the apartheid South African occupation in the 1980s. The occupation ended in 1994, when Walvis Bay was included in the rest of Namibia, which had acquired independence four years earlier. Namibia thus inherited western types of old age homes that were for whites only and for poorer people, i.e., black workers. Since its inception in 1960, Kuisebmond has been home to disadvantaged groups. Poverty and lack of housing are widespread. Very few residential care homes are offered to poorer strata, and existing homes are often too expensive for the average black older adult. As a rare exception, the OAH in Kuisebmond offers a low-cost housing option for older adults. This home belongs to the group of independent living facilities. The concept Old Age Home (OAH) is used in Kuisebmond and will be applied to denote this particular facility throughout this paper.

Interviews with older adults living in the community outside the OAH revealed a strong negative attitude to this residence. The question that arose was how these negative discourses played out in a community care setting. Furthermore, was there any truth to this criticism, and how did the residents who lived in the OAH view the residence?

The institution

The concept of the institution appears as an analytic tool in research on housing for older adults in Africa (Hungwe, Citation2011; Mupedziswa, Citation1998; Ncube, Citation2017). These studies apply theories from the well-known book by Goffman entitled Asylums from 1961 on the physical and social conditions in an institution (Goffman, Citation1991). In Goffman’s book, inmates are subjected to depersonalization and coercion. Depersonalization includes the ordering of people in institutions for special groups for correctional or care purposes. Several coercive depersonalization strategies are employed in order to make the inmates docile and enforce desirable behaviors. This links to the architecture of different institutions with similar architectural traits that were constructed for people with variations from able-bodied citizens, for example, for the old and infirm (Dovey, Citation1999; Markus, Citation1993). However, institutional traits are also found to various degrees in small-scale, everyday architectural environments (Robinson, Citation2006). The paper aims to examine whether characteristics associated with institutions can be found in the Kuisebmond OAH, and how they are manifested. Do architectural conditions contribute to institutional strategies as well?

In research as well as practice, the institution is largely identified as an anathema to good aging. Good architectural design for a dignified later life has been defined in contrast to the institution in terms of both design and conditions for daily living: homelikeness, personalization, and independence for the older individual, together with warmth and inclusion (Schwarz, Citation1999). Less institutional facilities could be supportive to changes in staff attitudes and practices (Nord, Citation2018; Shield et al., Citation2014). New housing and care options have been explicitly developed as alternatives to the institution; examples are assisted living (Greenfield, Citation2019), extra-care housing (Kneale & Smith, Citation2013), senior housing, and intergenerational housing. There is a variety of homes for older adults in sub-Saharan Africa that include facilities in a continuum from totally independent living residences to skilled nursing facilities in which older adults in need of medical and personal care reside (Madungwe et al., Citation2011). The few case studies of residences for older adults in sub-Saharan Africa show a variety of residents, care needs, service levels, and size of residences. These case studies were conducted in Zimbabwe (Hungwe, Citation2011; Madungwe et al., Citation2011; Mupedziswa, Citation1998; Ncube, Citation2017; Nyanguru, Citation1987), Democratic Republic of Congo (Pype, Citation2016), Zambia (Changala et al., Citation2015; Sichingabula, Citation2000), and South Africa (Dolo, Citation2010).

Methodology

The study is a qualitative ethnographic study in which interviews and observations were the main data collection methods (Pink, Citation2012). The researcher spent four months in the field and undertook daily visits in the area and to older adult’s homes and other places of importance to their everyday life and wellbeing, such as churches and clubs. This fieldwork started with one and half months of intensive data collection in the OAH. Semi-structured individual interviews were carried out with 19 inhabitants, of which ten were men. Three couples were interviewed together. The youngest was 62 and the oldest 95. They focused on each individual’s personal history, why they moved to the OAH, and their daily life. A total of 64 h of observations in the home were carried out and included the physical environment as well as everyday life in the OAH. Observations were documented with fieldnotes and photos. Relevant documents and drawings were also collected. Interviews with older community-living participants were also individual and semi-structured, lasted about 1–2 h, and included a walk around the premises. The aim with these interviews was also to trace the interviewees’ personal history and their daily lives in the home space. Twenty-four interviews were carried out with community-living older adults. Four were couples interviewed together, 14 interviews were with women alone, and six were with men. The interviewees’ ages ranged from 49 to 95. Participants in the OAH were recruited during observations by personal invitation to participate. Participants in the community were found through the Erongo Elderly Association, church clubs, the Shack Dwellers Federation, and through snowball techniques. An interpreter was used in most interviews and all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were also conducted with the acting matron in the OAH, a planner from the municipality urban planning office, and two social workers. Ethical considerations included the interviewee’s age and vulnerability in order not to strain the person’s capacity. Participation in the study was voluntary and the participants were guaranteed anonymity. The study adhered to the Namibian regulation of research ethics.

The analysis made use of both the intuitive aspects of qualitative analysis and more formal analyses (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The negative views of the OAH appeared first spontaneously in interviews, giving way to links to conditions in the OAH. These were expanded and explicitly explored theoretically in method and analysis. A directed content analysis was carried out in which the data were searched for institutional factors (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Most data were written texts (transcribed interviews, fieldnotes, and documents). They were read several times and examined for themes. Photographs supported the analysis of for instance the physical environment (Pink, Citation2012). The analysis was carried out in two steps. The initial analysis took a point of departure in the negative opinions about the OAH and explored the main concerns in detail. This corresponds with the strategy “identify and categorize all instances of a particular phenomenon” suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005, p. 1281). In the subsequent analytic step, these concerns were compared to an analysis of the views of residents in the OAH, the physical environment, and resident compositions. Goffman’s (Citation1991) conceptualization of institutions framed both analyses without any aim to validate or extend the concept of institution (cf. Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The presentation of the results reveals that two interrelated aspects of an institution appeared strongest in both analytic steps: depersonalization and coercion. These will be related to both the physical and the social conditions in the presentation of the results below.

Results

Nine women and 17 men aged between 62 and 95 lived in the OAH; among them were three couples. All of the residents were retired and thus had a right to the noncontributory pension that is available in Namibia. The OAH was jointly managed by the municipality department of community development and properties section and the local social work department of the Ministry of Health and Social Services. The subsidized rent was N$65 per month, including electricity.Footnote1 Two daytime staff members—an acting matron and an assistant—were employed by the municipality. Their tasks included supervision and practical housekeeping; they did not provide any personal care. The OAH could thus most accurately be categorized as an assisted living facility or extra-care housing facility since it was for independent living. The residents were expected to move if heavy care needs arose.

Institution-like building features or not

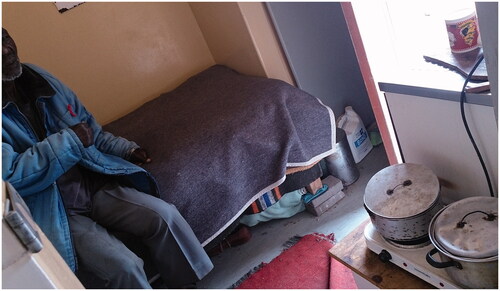

The residence was surrounded by an almost two-meter-high wall. It had a large gate and there was a watchman’s house at the entrance from which the residents’ movements during night hours were monitored (). In one interview, a drastic comparison with a notorious institution was put forward: One of the female older adults from the community compared the OAH with the apartheid compound where contract laborers had livedFootnote2 (). She said that “the okomboni [compound] is not a place for people,” and like the OAH, it lacked fellowship, family closeness, and peacefulness. She was familiar with the compound: she had sold bread at the gate when she was younger and had thus glimpsed inside what was otherwise a forbidden area for women. The high wall and the gate of the OAH may thus have impacted her opinion. These can be associated with an institutional spatial structure of incarceration. Another feature that can be associated with institutions are common rooms for social contact or for routinely enforced similar behavior (see Markus, Citation1993). The OAH had a separate dining facility where religious services and parties were occasionally held (). There was also a hall for functions. However, there was nothing enforced about the use of the common rooms. The hall was almost never used.

In the interior of the residence there were low buildings of connected apartments organized around three yards. The first of these was from 1980 and contained about 10 apartments (). These apartments were extremely small—around 8 m2—and two of them shared a single bathroom (). The second yard had been constructed just after 1994, and a third addition similar to the latter had been added recently (). The two latter yards had bigger apartments with one kitchen and a bedroom of about 20 m2 (). A few were slightly bigger and meant for couples. There was a total of 28 apartments. Four apartments were empty at the time of the fieldwork.

The small individual flats were perhaps similar to cells in an old institution (see Markus, Citation1993). However, the scale of the whole facility was small, and buildings were plastered in a light sand color which gave the yards a certain intimate ambience. This deviated from a harsh institutional environment and could represent a certain air of homelikeness. The OAH was neat and well-kempt. Observations showed that residents stayed indoors to a large extent, and the yards were often empty. Sometimes they gathered outdoors in the shade along the walls. Socialization between residents was limited, according to interviews. Aided by the residents, the staff grew many vegetables for consumption in the OAH in a net-covered garden. Some residents cultivated their own vegetables and flowers.

Depersonalization

A basic assumption that frames the OAH in Kuisebmond as an institution is the shared idea of older adults who lived in the community that the OAH was for people who had no family support or a no home of their own. This limited notion of residents in the OAH is interpreted as a depersonalization typical for an institution. The residents were defined as a restricted category of homeless and uncared-for, which deviated from cared-for citizens. This categorization excluded other motives for living in the OAH. For this reason alone, many older adults from the community who owned their own houses could not envision themselves moving to the OAH. One male interviewee was unwavering even when the low rent was brought up, asking, “why should I go there [to the old age home]? It is better here [in my own house].” This man also had two adult grandchildren living on his premises. Living together with children and grandchildren was among the arguments against a move to the OAH. When asked in an interview whether she would like to move to the OAH, one woman replied: “No, I have a lot of grandchildren. Why should I have to stay with them [the residents of the OAH] when I have a lot of kids?” However, this limited notion of the residents only partly coincided with those who actually lived in the OAH: Seven of the 19 men were either childless or had lost contact with their children. One female interviewee from the community acknowledged the potential support of the OAH for childless older adults, although she did not consider utilizing it herself. She said that “if you’re in a tough situation, then you can go to the old age home.” Her acknowledgment was reminiscent of the story told in an interview with a man from the group of loners: it was revealed that he had been desperate to find a solution to have his housing needs met in later life and that he was greatly relieved when the OAH appeared as an option. Although it was possible to apply for an apartment in the OAH, the health authorities sometimes identified certain individuals in need of help. A male interviewee in the OAH had been fired from his job as a driver because he had lost his eyesight. He had been sleeping in his car when the social workers intervened on his behalf for an apartment in the OAH. The fact that residents in the Kuisebmond OAH who lacked family support were a minority thus challenged the ideas held by older adults living in the community that defined the OAH as an institution. Depersonalization in the sense of a restricted definition of a homogenous group of older adults began to crack when the residents in the OAH were inspected more closely: They were a heterogeneous group of older adults in terms of age, gender, and family status. Most residents had children, some of whom lived in Kuisebmond or elsewhere in Walvis Bay. Others lived elsewhere in Namibia.

The idea that residents of the OAH had little choice but to move to the home was also challenged. According to the interviews, most residents had moved to the OAH voluntarily, even those who had children. The most common reason cited by interviewees for moving to Walvis Bay and the OAH was the mild climate. One of the female interviewees said that her doctor had recommended the move because of her heart condition.

The relationship between parents and children further challenged the idea of care of older adults in the family sphere. The matron said that

sometimes the older person wants to stay alone because if you stay in the children’s house you must do what the children say. They are grown-up people, so they don’t want to listen to anything like that. So they want to stay on their own.

Conflicts regarding whether or not a parent should live with a child appeared in the interviews. Some of the older adults in the home stated in interviews that they had chosen to live alone in the home against their children’s wishes. One woman stated: “I do not want to be a babysitter for my grandchildren.” In the interview, she talked about how she had been left alone with the toddlers for several days—a responsibility that she had found too great. Another said: “I don’t want to be involved in my children’s matrimonial life.”

According to observations, children occasionally came to visit. The matron noted however that in some cases the children never visited. She found that to be a problem, since the residents sometimes needed their children’s help, even if the home was for independent living. The contract for living in the facility stipulated that residents would have to leave the home if heavy care needs arose. It seemed as though the older adults living in the community thought that the residents in the OAH needed more help than what was actually the case, and that the OAH thus was a more institutional-like nursing home. Interviews confirmed that residents were aware of the part of the agreement regarding increased care needs. They indicated that in such an event, they would most probably have to move to their children. However, this rule was broken in the OAH: The deteriorating health of a South African man had resulted in care needs that exceeded what was acceptable in the home. According to the matron, they had not been able to establish contact with the relatives to whom he should have moved, who allegedly lived in South Africa. Despite his care needs, he was not forced to leave the home, but the matron and the assistant did not provide the care he needed. Instead, they had made arrangements with one of the man’s friends, who provided the necessary care while the man continued to live in his apartment in the home.

Alcoholics

Another widespread idea amongst elder interviewees from the community was that alcohol abuse was prevalent in the OAH, and that made it an unthinkable housing option. This represented another depersonalization of residents by a restricting definition of them as alcoholics. Drinking was intolerable behavior in general in the view of older adults from the community. One woman stated “No, I don’t want to go there, because old people there, they always just go to Ekutu to drink Otombo.”Footnote3

This idea was correct to some extent. According to the matron, about five of the residents were a disturbance due to their alcohol abuse. Some of these older adults who had alcohol problems belonged to the group who had neither children nor family. One man also used drugs; the matron likewise disapproved of this. In order to curb or control these problems, she considered rejecting applicants known to have alcohol problems. The matron said, “If you are a drinker then I say, no my dear, because I don’t want any more drinkers.” She noted that weekends in particular could be noisy, since the security guard was only present during weekday nights.

However, the lives of the majority of the 26 inhabitants included neither drug abuse nor asocial behavior. Even if some of the oldest residents, such as the 95-year-old man, rested a lot in their apartments, this was not only a passive life in old age; many residents, especially those that were slightly younger, below 70, supplemented their pensions with small businesses, offering e.g. construction work, transport services, or tailoring, or making fat cakes and vending them on the street. At the time of the start of the fieldwork in January, some residents were away visiting family in the countryside to take part in the farming activities when the rain started, just as the community living older adults did. Perhaps the residents’ lives were not that different from the lives of the older adults from the community; this “normalcy” did not seem to be acknowledged by the community living participants, even if that was a more prevalent categorizing feature than abusive behavior. The older adults living in the community appeared oblivious to the heterogeneity in the resident clientele present in the OAH.

Coercion

There were other restricting features in the OAH that were not mentioned in the interviews with community living participants. The spatial provision of small apartments was suitable enough for the variety of households that the OAH accommodated. The limited household sizes—single people and couples—may possibly be perceived as an institutional restriction to which space contributed. Children were not allowed, not even as over-night visitors. Most apartments allowed a maximum of one person while some allowed two per apartment. Everyday life was to some extent restricted. While the residents in the OAH enjoyed full freedom to move around and leave the residence during the daytime—and according to observations they took advantage of that freedom frequently—their movements were severely restricted at night. The gates were locked by a guardian every day at 8 pm, and they remained locked until the morning. The residents were thus confined behind the walls throughout the night. The compound metaphor that the woman interviewee had used was thus not that farfetched, and it defined a critical dissimilarity to living in the community. According to the matron and the planner, this was a security measure aimed at protecting the residents. The residents did not see it that way, however. They protested against what they regarded as excessively controlling conditions, including the closure of the gate and their restricted nighttime movements. Some challenged these restrictions in practice by leaving anyway. This had escalated to become a serious conflict with the municipality, which had chosen to take measures to curb unwanted behavior by issuing documents with rules for the residents of the OAH. The tone of these documents about what is expected from the residents reveals the tense relationship between the residents and the municipality; the documents included a threat of eviction if the rules were not respected.

The municipality documents also prohibited alcohol abuse, stealing from fellow residents and stealing municipality property, and they forbade gossip and inappropriate language use. The apartments were supposed to be kept nice and tidy. Some of these rules include self-evident, conventional, respectful manners, while others challenge the idea of independent living expected in the OAH and appear as a regulatory gray zone. The rule forbidding overnight visits from a partner to whom the resident was not married or engaged could be seen as an infringement of the adult person’s right to personal matters. Three couples who lived in the OAH had been married upon arrival. One couple had formed while they were living in the OAH, but after three years of being in a relationship, they still had their own apartments for singles. According to the female member of this couple, the matron had strongly disapproved of the relationship. Many would probably agree that the simple question of whether that was her legitimate concern was relevant here.

These regulations could be understood as institutional strategies in the sense of the forming of desired behaviors, seeking to create a healthy and obedient resident that would function according to these rules.

Discussion

The institutional features that appeared in the study seemed to exclude residential care from community care services. Community living older adults dissociated themselves from the OAH by nurturing the well-established images that imply that care for older adults is a family affair and that residential care homes are an unnecessary service or could be useful for childless and lonely older adults (Aboderin et al., Citation2015; Nzima & Maharaj, Citation2020; Oakley, Citation1998; Pype, Citation2016). There is a need to reduce the stigma associated with residential care in order to make it a proper alternative for housing for older adults as a complement to other care solutions. Scholars warn not to import western solutions in an African context, such as existing models of residential care (Nzima & Maharaj, Citation2020). Importantly, this should not downplay the importance of residential care in care for older adults that can be developed according to local needs and conditions (see Nord & Byerley, Citation2017; WHO, Citation2017). The results in this study bring to light a number of potentialities that can integrate residential care homes in community care. The existing variety of residential care homes can be explored and developed further (Madungwe et al., Citation2011).

Potential residents

Many misperceptions held against the OAH were partial misunderstandings of the conditions there and were thus erroneous. Even though some of the residents did not have children, the categorization of residents based on childlessness was far from encompassing the whole group of residents. Most residents had children and some of them had explicitly chosen not to live with them (Pype, Citation2016). Contrary to established views, the rules of the OAH implied that the residents had to have children to whom they could move should heavier care needs arise. However, the fact that childlessness was bypassed in the OAH, as in the case of the South African man, indicates the potential for integration in community care in which a heterogeneous group of residents would be included. Also, the management’s wish for healthy, sober residents would be a misconception in a community care context. Safeguarding the elder individual’s private circumstances, which were to some extent questioned by the management, might be a new attitude that could pave the way for increased acceptance of older adult residences and homes as a housing option in the future.

Many of the community living participants who contested the OAH were house owners. Many older adults approaching retirement are not house owners, however. Residential care homes could possibly be an option for this group.

Potential carers

Community care needs to pool all resources together, such as family, professional carers, and volunteers (Nzima & Maharaj, Citation2020). The care solution for the South African man in the study shows great potential in links between community and residential care. The non-provision of care was a formal practice linked to the staffing level and showed that there was no spatial obstacle to providing care in the residence—at least not of the sort the man received: supervision, help running errands, and care when he was sick. It is thus possible to envision a situation where children or others could come to the residential care home and assist with the care of their parents while they continued to live there. In such a case, it would be necessary that children and visitors be allowed to stay overnight. Family reliance is still important for housing, care, and support in later life (Nord, Citation2021), but family care is also under great pressure and in need of support (Hoffman & Pype, Citation2016). Links between these caring resources could contribute to residential care homes being seamlessly interwoven in the community care services to the benefit of limited family care resources. They could also be integrated in the built environment fabric as well with torn down walls.

Future residences and community care

Research has shown that self-determination and freedom are extremely important for residents’ appreciation of life in a facility (Mupedziswa, Citation1998; Nyanguru, Citation1987), and circumscribed living conditions nurtured a strong resistance to a move to the OAH in the community. The fact that the residents’ whereabouts and behavior were controlled was in clear opposition to the independent life that was the intention of the home. Recommended features to counteract institutional traits in homes for older adults were present, such as homelikeness, personalization, and independence (Schwarz, Citation1999), but these were side by side with opposing elements. Powers did not necessarily play out as in massive and architecturally large-scale institutions, but appeared in moderate practices and small-scale spatial conditions (Markus, Citation1993; Robinson, Citation2006). The anger with which demands of independence were made by the residents did not mirror the gratefulness, apathy, and submissiveness that other studies have shown (Hungwe, Citation2011; Nyanguru, Citation1987). It seemed that the residents took their independence more seriously than the management did. This can be interpreted as an indication that institutional traits that circumscribed everyday life in the OAH are no longer acceptable but pave the way for other less institutional housing alternative (see Coe, Citation2018).

The discourses about not moving to an old age home by those who lived in their own houses seemed non-negotiable. The openness to other solutions was thus found among those who had actually moved to the OAH. Cati Coe (Citation2018) ascribes considerable innovativeness to older adults’ imagination of possible other solutions and they could challenge dominant discourses, albeit tentatively and weakly. In this case, the voluntary move to the OAH was a challenge and innovation in itself, which might contribute to the establishment of other housing alternatives for older adults against dominating discourses, governmental policies, and practices.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This is a very low rent; compare to the present monthly pension of N$1,200, equivalent to about US$100.

2 The contract labor compound, which was closed in 1994, was a huge and notorious camp introduced by the South African apartheid regime in which single male workers lived in barracks. They had common toilet and washing facilities and took their meals in a dining facility that accommodated 3,000 people. The rooms in the compound accommodated 20 people each, and their movement outside the compound was heavily regulated by pass laws and police controls (Byerley, Citation2015).

3 Local bars and a local handmade beer.

References

- Aboderin, I., Mbaka, C., Egesa, C., & Akinyi-Owii, H. (2015). Human rights and residential care for older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: Case study of Kenya. In H. Meenan, N. Rees, & I. Doron (Eds.), Towards human rights in residential care for older persons (pp. 13–22). Routledge.

- Byerley, A. (2015). The rise of the compound–hostel–location assemblage as infrastructure of South African colonial power: The case of Walvis Bay 1915–1960. Journal of Southern African Studies, 41(3), 519–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2015.1032724

- Changala, M., Mbozi, E. H., & Kasonde-Ng’andu, S. (2015). Challenges faced by the aged in old people’s homes in Zambia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 2(7), 223–227.

- Chepkwony, S. J. (2019). Public perceptions of elderly people and elderly care institutions and uptake of institutionalised care for the aged in Nakuru County, Kenya [Ph.D. thesis]. Kabarak University.

- Coe, C. (2018). Imagining institutional care, practicing domestic care: Inscriptions around aging in southern Ghana. Anthropology & Aging, 39(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.5195/aa.2018.169

- Dolo, M. J. (2010). Residential care for the elderly in Ethewini metorpolitan municipality: A case study approach [Ph.D. thesis]. University of Kwazulu-Natal.

- Dovey, K. (1999). Framing places: Mediating power in built form. Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1991). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Penguin Books.

- Greenfield, E. A. (2019). Advancing program theory for licensed assisted living services in independent housing. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 33(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2018.1561593

- Hoffman, J., & Pype, K. (2016). Introduction: Spaces and practices of care for older people in sub-Saharan Africa. In J. Hoffman & K. Pype (Eds.), Ageing in sub-Saharan Africa: Spaces and practices of care (pp. 1–20). Policy Press.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hungwe, C. (2011). The meaning of institutionalisation to older Africans: A case study of a Zimbabwean old people’s home. Electronic Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(1), 37–42.

- Kneale, D., & Smith, L. (2013). Extra care housing in the UK: Can it be a home for life? Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 27(3), 276–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2013.813423

- Madungwe, L. S., Mupfumira, I. M., & Chindedza, W. (2011). A comparative study of the culture of skilled nursing facilities in high and low density areas: A case for Masvingo urban in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(1), 1–12.

- Markus, T. A. (1993). Buildings & power: Freedom and control in the origin of modern building types. Routledge.

- Mupedziswa, R. (1998). Community living for destitute older Zimbabweans: Institutional care with a human face. Southern African Journal of Gerontology, 7(1), 26–31. https://doi.org/10.21504/sajg.v7i1.128

- Ncube, N. (2017). Pathways to institutional care for elderly indigenous Africans: Navigating contours of alternatives. African Journal of Social Work, 7(1), 44–51.

- Nord, C. (2018). Resident-centred care and architecture of two different types of caring residences: a comparative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1472499. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1472499

- Nord, C. (2021). Family houses – building an intergenerational space in post-apartheid Namibia. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue canadienne des études africaines. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2021.1938618

- Nord, C., & Byerley, A. (2017). Housing Alternatives for Elderly Urban Residents: Case Studies from Uganda and Namibia. Paper Presented at the II International Conference African Urban Planning, Lisbon. http://bth.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1432379&dswid=3856

- Nyanguru, A. C. (1987). Residential care for the destitute elderly: A comparative study of two institutions in Zimbabwe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 2(4), 345–357.

- Nzima, D., & Maharaj, P. (2020). Long-term care for the elderly in sub-Saharan Africa: An analysis of existing models. In P. Maharaj (Ed.), Health and care in old age in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 41–59). Routledge.

- Oakley, R. L. (1998). Local effects of new social-welfare policy on ageing in South Africa. Southern African Journal of Gerontology, 7(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.21504/sajg.v7i1.126

- Pink, S. (2012). Situating everyday life: Practices and places. SAGE.

- Pype, K. (2016). Caring for people ‘without’ value: Movement, reciprocitiy and respect in Kinshasa's retirement homes. In J. Hoffman & K. Pype (Eds.), Ageing in sub-Saharan Africa. Spaces and practices of care (pp. 43–69). Policy Press.

- Regnier, V. (2002). Design for assisted living: Guidelines for housing the physically and mentally frail. John Wiley & Sons.

- Robinson, J. W. (2006). Institution and home: Architecture as a cultural medium. Techne Press.

- Schwarz, B. (1999). Assisted living: An evolving place type. In B. Schwarz & R. Brent (Eds.), Aging, autonomy and architecture. Advances in assisted living (pp. 185–206). John Hopkins University Press.

- Schwarz, B., & Brent, R. (Eds.). (1999). Aging, autonomy and architecture. Advances in assisted living. John Hopkins University Press.

- Shield, R. R., Tyler, D., Lepore, M., Looze, J., & Miller, S. C. (2014). “Would you do that in your home?” Making nursing homes home-like in culture change implementation. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 28(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2014.930369

- Sichingabula, Y. M. (2000). An environmental assessment of Divine Providence Home in Lusaka, Zambia. Southern African Journal of Gerontology, 9(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.21504/sajg.v9i1.193

- WHO (2017). Towards long-term care systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/ageing/long-term-care/WHO-LTC-series-subsaharan-africa.pdf