Abstract

Background: Research about gender identity development is still in its infancy, especially among youth who experience gender dysphoria and are accessing gender-affirming medical care.

Aims: This article contributes to the literature on how gender identity and gender dysphoria is experienced, expressed and addressed by youth who have started, or are just about to start, a gender-affirming medical intervention.

Methods: The project draws from qualitative interviews with 36 trans children and youth of different ages and stages of puberty. The data were collected in three specialized Canadian clinics that offer gender-affirming care and they were analyzed through inductive thematic analysis.

Results: Two interlinked dimensions of the youth’s lives allow meaning-making of their gender identity: 1) internal or personal and 2) interactional or social processes. Careful analysis reveals three gender identity development pathways that may be taken by youth, from early questioning to the affirmation of their gender identity. A discussion of current models of gender identity development and their limitations concludes the article.

Introduction

Over the past few years, we have observed many heated debates focused on questions around the capacity of a child to know their gender identity, and whether children who experience incongruence between their assigned and felt gender should be allowed to access gender affirming medical interventions. At the same time, trans-affirming approaches that aim to promote gender exploration and affirmation without constraints or barriers by facilitating access to different forms of transition have been increasingly put into practice with children and young people in North America (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2019) and elsewhere as in Australia (Riggs et al., Citation2020)

Indeed, while some authors defend the need for certainty that a young person’s gender is stable before allowing them to transition socially or medically (Wren, Citation2019), others, who embrace the trans-affirming approach, consider that social and medical transition are crucial and essential aspects of the process of gender identity development and consolidation (Ashley, Citation2019a; Ehrensaft et al., Citation2018). They assert that it is harmful and unrealistic to require certainty before granting access to medical interventions (Ashley, Citation2019b) because gender is in itself fluid and not always experienced as binary.

This paper aims to improve knowledge about trans children and youth experiences regarding the development, consolidation and affirmation of their gender identity, particularly considering trans-affirming approaches for intervention. Several authors have highlighted the need for more research to achieve a greater understanding of the developmental trajectory of gender diverse youth in order to better meet their needs (Olson-Kennedy et al., Citation2016; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2015; Turban & Ehrensaft, Citation2018).

This article contributes to a better understanding of the complex process of gender identity formation and affirmation by examining the narratives of 36 trans children and youth who have started, or were just about to start, a gender-affirming medical intervention such as puberty suppression or hormone treatment. The data were collected in the context of a project that aimed to understand the experiences of prepubertal, pubertal and post-pubertal trans youth and their parents/caregivers who have been referred to three specialty clinics offering gender-affirming medical interventions in Canada. The objective of the project was to learn more about their well-being, their concerns, experiences with and reasons for seeking care as well as how they expressed and addressed their gender identity. This paper specifically focuses on the experiences of youth and their realization and affirmation of their gender identity.

The paper begins with a review of the literature on transgender children and youth and their gender identity development, followed by the study methodology. We then present findings on how youth experience their gender identity development from early questioning to consolidation and affirmation through two dimensions: 1) internal or personal 2) interactional or social processes, as well as the interactions between the two dimensions. We go on to present three gender identity development pathways that young people describe having taken, from early questioning of gender to affirming their gender identity, contributing to the understanding of gender identity development, and challenging literature on desistance and persistence. We conclude the article with a discussion that offers implications for practice for professionals working with these young people.

Literature review

Recent work focusing specifically on gender identity development among trans youth under 18 from their own perspective is relatively limited (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2017), so it can be helpful to consider work on this topic among emerging adults (Gray & Walters, Citation2018; Nicolazzo, Citation2016) and even older adults (Pitcher, Citation2018). Studies of gender identity development in children more generally have also identified the unique difficulties faced by the trans youth present in their samples (Perry et al., Citation2019).

Kuper et al. (Citation2018) mention two dominant approaches in the literature on the topic, namely stage models inspired by Devor’s 14-stage model (Devor, Citation2004), and narrative perspectives (Gray & Walters, Citation2018; McLean et al., Citation2017; Pitcher, Citation2018) which “identify making meaning of one’s experience as central to the identity development process” (Kuper et al., Citation2018, p. 2). Devor (Citation2004) theorized that individuals come to recognize themselves as trans through 14 stages of interpersonal and intrapersonal exploration and analysis, describing processes that reappear in subsequent work, notably those of Discovery, Delaying and Integration. Discovery describes the moment where a person first becomes aware of the existence of trans identities (Kuper et al., Citation2018), while Delaying refers to periods where a person may postpone advancing to a next stage of identity development such as accepting that they are trans or beginning their gender transition (Devor, Citation2004; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2015). Devor describes Integration as a gradual process through which a trans person “becomes more firmly embedded in their post-transition lives” (Devor, Citation2004, p. 63), whereas Kuper et al. (Citation2018) describe it as the process through which the meaning a person makes of their gender becomes an integral part of their larger sense of self.

Stage models have been criticized for implying that gender identity evolves along a linear and progressive trajectory with a beginning and an end (Kuper et al., Citation2018), whereas many authors note that gender identity is dynamic for many trans people and continues to evolve over the life course (Ashley, Citation2019b; Pitcher, Citation2018; Temple Newhook et al., Citation2018). Pitcher (Citation2018) analyses trans people’s gender histories using phenomenology’s concept of embodied sedimentation, which theorizes that a person’s experiences and actions mark and transform their body in a cumulative manner through repetition over time (Ahmed, Citation2006; Wehrle, Citation2016).

Other authors have sought to categorize and understand young people’s trajectories of gender identity development based on when and how dysphoria first appears. It is not always clear in these studies whether authors who use the term “gender dysphoria” understand it to mean “distress” as per the DSM5 diagnosis or if they use it as analogous to gender diversity, gender variance, or gender nonconformity. Gender nonconformity, for example, is used more largely to designate people whose gender identity, behavior or appearance differs from prevailing cultural and social expectations about what is appropriate to their gender (Coleman et al., Citation2012). Since the samples in these articles are usually constituted of children and youth attending gender clinics, it is reasonable to assume that the term is used to indicate that study participants have been diagnosed as suffering from gender dysphoria. In this article, however, we wish to distance ourselves from a medicalized perspective and unless explicitly stated otherwise, we use gender dysphoria to designate the marked “distress and discomfort some trans people experience because of the discrepancy between their gender assigned at birth and gendered self-image” (Ashley, Citation2019a, p. 1). We do not know if the young participants in our study received this diagnosis, but it is likely that it was required before they could begin hormonal treatment. To be clear, we make a major distinction between the terms “gender dysphoria”, which refers to a intense distress, and “gender identity diversity”, “nonconforming gender” or other related terms that refer to an identity or feeling of not being cisgender, which may or not be accompanied by intense feelings of distress related to one’s gender. We favor the use of identity terms to designate these youth even when they are receiving treatment that may have required a diagnosis.

Cohen-Kettenis and Klink (Citation2015) identified two sub-groups among youth experiencing diagnosed gender dysphoria who were seen at a gender clinic in Amsterdam: youth who experienced and disclosed gender dysphoria in early childhood (labelled “early onset”) and youth who only experienced and manifested dysphoria at a later age, often around or after puberty (“late onset”). This way of subgrouping trans youth is however not without criticism. For example, Riggs (Citation2019) explains that this framework assumes there is only one way to be trans, and a way an adult can know who is trans from who is not. In an earlier article, Steensma et al. (Citation2011) categorized young people who experience childhood gender dysphoria as either “persisters” or “desisters”, defining desisters as youth who initially experienced gender dysphoria but who the authors consider to have become comfortable with their assigned gender as time progresses. Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis (Citation2015) later suggest there may be a third pathway, “persisters-after-interruption”. Authors such as Temple Newhook al. (Citation2018) question whether it is helpful to categorize young people’s gender experiences according to the schema of “persistence” and “desistance”, contending that it rests on a binary understanding of gender in which “cisgender” and “transgender” are immutable and mutually exclusive categories (Serano, Citation2016) and in which only transgender identities that are static throughout the life course are considered to be valid or positive as an outcome. It also diverts attention from the important questions of how best to support children in the development of their gender identity (Temple Newhook et al., Citation2018). A small-scale companion study to the one discussed in this article considered 10 youth between the ages of 9 to 21 years old, as well as their parents, who were among the first trans youth to come out in French-speaking Switzerland. Most of these youth were not accessing gender affirming care because it is not available to minors in this region. The project nevertheless allowed to discern that these trans youth had a slightly different profile from the ones suggested by Cohen-Kettenis and Klink (Citation2015) and Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis (Citation2015). Even within the very small sample, the team discovered that some youth may experience gender dysphoria before puberty but not come out in childhood because of internal tension or an inability to position themselves, suggesting the emergence of three youth profiles: the affirmed child, the silent child and the neutral child (Medico et al., Citationin press).

Recurring themes in studies that examine gender development from the perspective of the trans youth themselves include the interaction of internal (personal) processes with external and social elements including family adjustment and support, sociocultural influences and societal discourse and norms (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2017; Kuper et al., Citation2018). The concept of master narratives (Bradford & Syed, Citation2019; Kuper et al., Citation2014) used by different authors appears to be helpful in understanding how youth negotiate their identity in construction in relation to social norms. Master narratives are defined as “ubiquitous, powerful cultural stories with which individuals negotiate in constructing personal identity” (McLean et al., Citation2017, p. 93), including cisnormativity, within which only cisgender identities are viewed as “normal” or “standard” (Bradford & Syed, Citation2019). Several authors discuss the pressures exerted by transnormativity, which frames some trans identities, experiences and narratives as more legitimate or desirable than others (Bradford & Syed, Citation2019; Johnson, Citation2016; Nicolazzo, Citation2016).

Recent literature has noted the growing diversity and prevalence of identities and labels espoused by youth who identify as something other than male/female or trans, including a range of non-binary and other identities (Cohen-Kettenis & Klink, Citation2015; McGuire et al., Citation2019; Twist & de Graaf, Citation2019). Though the experiences of both non-binary and gender-nonconforming youth and trans youth of color tended to be absent from earlier work, several recent papers have examined the gender identity development and affirmation of youth and young adults who concurrently navigate both these diverse sets of identities (Kuper et al., Citation2018; Kuper et al., Citation2014; McConnell, Citation2018; Nicolazzo, Citation2016).

Methods

The study was designed drawing from Grounded Theory (GT) methodology (Dey, Citation1999; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998) to ensure that data is “grounded” in participants’ experiences. However, given the complexity of managing multiple ethics board reviews, and in order to accommodate the perspectives of a multidisciplinary research team composed of qualitative and quantitative researchers from both social and medical fields, the study methodology was adapted to integrate Thematic Analysis (TA) as a method for analyzing the data (Braun & Clark, Citation2006). GT was therefore used as a methodology to organize the original design of the study (inductive approach, reliance on a sensitizing concept—that is using background ideas that inform the research development (Bowen, Citation2019)—rather than a fully developed theoretical framework, and inclusion of various data collection contexts and experiences to achieve maximum diversity), whereas TA was used starting from the beginning of data collection to better fit the time-frame and research context. Combining these methodologies is helpful to produce a multidimensional understanding of medical experiences (Floersch et al., Citation2010) and particularly efficient for centering the voices of trans youth (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2019; Riggs et al., Citation2020).

Recruitment and data collection took place in three Canadian clinics offering gender affirming care: Meraki Health Center (Montreal, Province of Quebec), the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO, Ottawa, Province of Ontario) and the Health Sciences Center Winnipeg (Winnipeg, Province of Manitoba). Gender affirming practices are based on the principle of recognizing and respecting the child’s unique experiences of gender identity and expression. While clinics differ in terms of staff, services, and protocols for accessing care, all commit to adhering to the principles of gender affirming care while providing health services to trans youth.

Participants were recruited through the clinics’ patient lists, which included a variety of youth ranging from prepubescent children to post-pubescent youth and some of whom had started medication (puberty suppression and/or hormone therapy). An invitation letter was sent to each potential participant and their parent. This letter described the research and invited the participant and parent to contact a research assistant at the site where they received care if they were interested in taking part in the study. Both parent and child had to agree to participate to be eligible. Participants were chosen according to a variety of sampling principles (age, stage of puberty, gender identity and medical interventions received).

Data were collected through semi-structured qualitative interviews with mainly open-ended questions and a socio-demographic questionnaire that was completed by the parent, since certain information such as income and insurance would not likely be known to the child. Informed consent or assent was obtained from parents and youth. An anonymous code was generated for each parent-child dyad to preserve anonymity. A list of support and mental health resources was given to all participants, and referrals to appropriate services were provided to those who expressed a need for additional support. An emergency protocol was developed for each clinic site to ensure the safety of youth who might be at risk of suicide or child maltreatment.

A total of 36 interviews were conducted with youth and an additional 36 interviews were conducted separately with their parents. Youth were 9 to 17 years old (average 15 years old). The length of youth interviews ranged from 24 to 104 minutes (average 61 minutes). Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. All material presented in this paper is based on the interviews with youth to center their experiences and perspectives, except for information from the sociodemographic form completed by the parent. Interviews with youth explored various themes from family and other social supports, how they recognize and address gender identity and gender dysphoria, their experiences of beginning medical treatments, and their experiences at clinics.

Data analysis consisted of thematic analysis (Braun & Clark, Citation2006). Initial codes were first generated at a semantic level by reading each line of the interview transcripts, after which they were analyzed and categorized into themes. Inductive thematic analysis was used to ensure coherence with the initial GT methodology. We went beyond simply describing the interview material by comparing study material between youth and reviewing the themes as analysis progressed. Analysis was conducted using MAXQDA data analysis software. All participants were given a pseudonym to protect confidentiality.

The project was approved by each of the ethics boards responsible for clinical sites (Meraki Health Centre and McGill University; CHEO; the University of Manitoba and Health Sciences Centre Winnipeg), as well as by the ethics boards responsible for the principal investigator and any co-researchers who might access raw data

Results

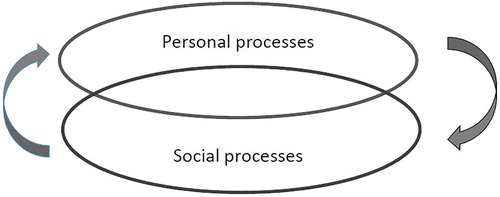

Youth shared many details about how they perceived and felt about their current gender identity and the processes through which it developed and consolidated. We first provide an overview of participants and how they described their gender identity. Then, we present the processes of gender identity development and consolidation that appeared in young people’s narratives. These processes fall roughly into the categories of 1) internal or personal and 2) interactional or social processes. However, overlaps between these two were frequent, showing the importance of interactions between the personal and social processes. Finally, we present three gender identity development pathways that young people described, from early questioning of gender to affirmation of their gender identity. The trajectory of each youth is indicated with the labels A (Early dissonance, early affirmation and transition), B (Early dissonance + delayed transition) and C (Late appearance of gender dysphoria) in the text.

At the time of the interview, all youth had reached a point where they endorsed a gender identity other than that assigned at birth with enough conviction to come out to their parents, access the gender clinic and begin evaluating or accessing gender affirming medical interventions through the clinic (See Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2019 for in-depth discussion of the medical care they received). Most youth were still actively thinking about how they define and understand their gender identity at the time of interview.

At the start of the interview, youth were asked what pronouns they preferred and how they would describe their gender. All the youth we interviewed requested that we use binary gendered pronouns (he/his or she/her) associated with a different gender from the one they were assigned at birth. The majority of youth described their identity as female/woman/girl or male/man/boy, with or without the prefix “transgender” or “trans”. Several youth said they preferred not to use the prefix “trans” or “transgender” because they saw themselves or wished to be seen simply as male/man/boy or female/woman/girl. A few transmasculine youth used terms that they regarded as slightly less explicitly binary to describe their identity, including “guy”, “trans guy”, “transmasculine”, “FTM” and “female-to-male transmasculine”. Three transmasculine youth (Scott, Jason and Oliver) implied or explicitly stated during the interview that they were more gender fluid or that their gender identity strayed from the binary, despite using and asking us to use binary pronouns (all used “he/his” pronouns at the time of interview). One described his authentic identity as probably more “in the middle” or “agender”, saying he went “by male pronouns and then I won’t get that cringe [I get from female pronouns], I will get that ‘Meh’ [instead]” (Scott, 16, traj. C), another described himself as “male with gender-fluid tendencies” (Jason, 17, traj. B), and a third identified as “FTM” while feeling “a balance of masculinity and femininity” (Oliver, 16, traj. B).

Most youth were described by their caregiver in the open-ended question of the sociodemographic questionnaire as “white”, “Anglo-Saxon”, “Caucasian”, “Irish”, “Canadian” or “Québécois”, except for five youth who were indigenous and/or members of racially marginalized groups.

Gender identity development and consolidation: personal and social processes in action

Several themes and processes appear in young people’s narratives in relation to the development and consolidation of their gender identity. We have organized these processes into two broad categories which have a considerable amount of overlap, as schematized in . Some of the processes can be described as essentially personal, internal processes, while others can be described as predominantly social in nature, in that they are centered on the youth’s interactions with other people, with society and social norms, or with narratives or sources of information that are external to themselves. Many other processes exist in the overlap between these two categories. Most youth recounted both personal and social processes that occurred concurrently, in dialog or in direct sequence throughout their trajectory.

Personal processes: gender dysphoria as a driver for exploration

What we refer to as internal processes mainly concerns the dissonance youth feel between their experienced gender identity and the gender they were assigned at birth and/or the gendered elements of their body, as well as how they understand this dissonance. Interactional processes, on the other hand, relate to the youth interacting with others, including parents, friends, families or institutions; these processes appear particularly important in consolidating and asserting identity, and they can also be a key aspect of experiencing and understanding internally felt dissonance. There are many complexities to the connection between internal and interactional processes. These categories are not mutually exclusive, and some situations may be experienced as both internal and interactional processes. Within these categories we have also identified elements that may assist or impede gender identity development, assertion and consolidation.

Given that gender has an important social element, few processes in the narratives could be categorized as exclusively personal in nature. However, gender dysphoria is the most notable exception. Even though normative expectations and social stereotypes that may lead to dysphoria are a product of social construction and inform how people feel about themselves, gender dysphoria appears as an essentially personal experience and driver for exploration or action in many narratives. Several youth describe how it led to or contributed to them questioning their assigned gender, or how it drove them to seek parental support or medical care to help them modify their body or to prevent or reverse pubertal changes.

I started to realize I really didn’t like how my body was changing when I started puberty, so around 9 years old. When I was 9, I realized “No, I really don’t want to have breasts and stuff like that”. (Jeff, 15 year-old boy, traj. C)

Personal/social processes: feelings as a driver for exploration

As they developed an internal sense of their gender, youth sought ways to express and connect with it and to make a more authentically gendered version of themselves visible to others. While the initial feeling of dissonance is individually and deeply-felt and may be accompanied by periods of private doubts and questioning, the process of identity development appears to be highly interactional. Indeed, the participants’ narratives highlight the importance of interactions between the youth (including their reflections and feelings about their identity) and the world around them (people, social media and other on-line sources, institutions), including the feedback they received as they expressed and experimented with their gender. In other words, though they relied on their own feelings and emotional responses to guide their exploration, the information and responses they received from others played an equally important role.

For example, many narratives show how discomfort or other feelings in response to social experiences or information about trans identities served as a driver or guide in their gender exploration. Sylvie recounts that she “revoked” her coming out as a girl after she saw a video about gender affirmation surgery that she says “disgusted her”, but that she then began her transition in earnest a few months later after the feelings of dissonance resurfaced:

It just came back as a feeling, and then I was like, “No. I don’t want to stay how I was born.” And then it just came back stronger than ever and then it [my transition] finally started. (Sylvie, 13 year-old girl, traj. A)

Personal/social processes: meaning-making

After they first began questioning their gender, youth explored it through various processes, including reflection, discussion, seeking information, and experimentation with differently gendered ways of presenting themselves. At the center of this process of interaction with the social world, meaning-making appeared as an important part of gender identity development and consolidation. Some describe this process of “making sense” of their gender as an almost instantaneous occurrence once they discovered trans identities, whereas others describe it as an extensive process that required reflection, research, and experimentation. Many describe first hearing about the existence of trans identities as a turning point for them, a crucial piece of the puzzle that allowed them to make sense of their experience, sometimes after years of discomfort or confusion. Some youth learned about trans identities by accident, while others found the information as a result of seeking information to help them understand their own experience of their gender. Youth most commonly found the information online, while others heard about or acquired more information through acquaintances or friends, through contact with a trans person, or from staff at the specialty clinic.

Uh, it just took some time for me to figure out the right word. I was looking through YouTube and I found some videos, and I watched it and it, I just connected with it. (Sylvie, 13 year-old girl, traj. A)

As soon as I read the article about some, like it wasn’t even a question, I knew I was trans. (Steve, 17 year-old male, traj. B)

Though for most youth it was helpful to acquire information about trans identities, a few accounts suggested that the trans narratives they accessed actually delayed or complicated their process of exploration because these narratives did not align with their own experience. Some youth recount searching further to find narratives that did validate their experience or doing personal work to overcome their doubts and accept themselves despite these invalidating narratives.

I knew that I wasn’t cis, I knew that, but I didn’t know exactly, ‘cause for some reason at that point I was still kind of confused. it made it more confusing because I’m gay now, but before, I would have been considered straight, so I was a bit more confused with that because I knew that a good amount of trans guys are straight, like they liked girls before they transitioned, and I was just kind of confused, I was like, “Is this a different thing?” (Josh, 16 year-old male, traj. C)

Another youth said the absence of an accessible youth narrative caused him to dismiss his feelings about his gender until he accidentally came across a narrative that did validate his experience.

When I was in middle school, I, this was right after Caitlyn Jenner came out, and I learned that it’s not, ‘cause I knew what being transgender was. But, I thought it was something you knew and expressed at a very young age. So, I never thought about it, and I, that was when I came to realize that something’s that you can pursue, I guess, later in life, and then, it kind of clicked from there, and I spent a while trying to experiment with my presentation, and pronouns and stuff, and it just fit, yeah. (Daren, 16 year-old male, traj. C)

Youth also discussed a range of other processes that fall in the overlap between the personal and the social. Significant among these were the various gender affirming medical interventions they received or were waiting for through the specialty clinics. For most, the physical changes or effects they sought or experienced as a result of the care had a deeply personal significance as it helped to diminish their gender dysphoria, but many also recounted their social significance in that these changes helped them to be perceived as their gender identity more consistently or they hoped that this would be the case. Most youth had a very clear and defined sense of their gender identity upon first coming to the clinic, but many recounted that their gender identity had continued to evolve or consolidate through or during the course of care at the clinic.

Social processes: exploration and experimentation with external feedback

Though the process of achieving a sense of one’s gender is experienced by youth as a very personal one, they often arrived at this knowledge through a range of social and interpersonal processes and experiences including making themselves more visible to others, naming themselves, or expressing their gender differently to others. Indeed, youth also experimented with asserting and expressing their gender through language, including with pronouns and chosen names. For example, Jim, a francophone youth, explains how he used the gendered nature of French to experiment in asserting his gender. Contrary to English where words are rarely gendered, the gender of a person is constantly emphasized in French through the gendered conjugation of verbs and adjectives. Gender-neutral pronouns are also less widely used and accepted in French than in English, where the use of “they” as a singular gender-neutral pronoun is increasingly common. Jim describes how he navigated this gendered aspect of his mother tongue and eventually used it to assert his gender:

I started to gender myself male when talking about myself [in French]. First, I stopped using the adjectives that you have to […] change to show it’s male or female. […] I always tried to avoid and if I really had to, I used the male version of the word, but it was just a word every few minutes, but people didn’t really notice, but at some point it became all the time gendered male. (Jim, 14 year-old trans guy, traj. B)

Youth explored their gender in a variety of ways, including adopting a persona with a different gender in play with friends in person or on-line, or by “dressing up” as a character of a different gender for Halloween. Many experimented with different ways of presenting themselves through clothing (including binders, tucking, bras), make-up, accessories and hair styles.

While clothing is described as a way to explore and assert their experienced gender, several youth also recount having spent a period of time intentionally dressing and presenting in alignment with social expectation for their assigned gender after initial explorations of a different gender. This took place in their mid-teens in the case of three transmasculine youth, and around the age of 10 for one girl. While for some this seems to have been an attempt to connect with their assigned gender, the discomfort it caused them appears to have had the opposite effect, of making clear to them that it did not reflect their authentic gender.

In about Grade 7, Grade 8-ish, I started to present super femininely, because I don’t know, there was a lot going on in my brain. I was like, “Why am I feeling weird. I need to fit in with the girls.” […] I bought a bunch of makeup and stuff, but it didn’t feel right. […] It didn’t last, no. (Randy, 16 year-old male, traj. C)

An additional important experience that was present in the narratives of many participants is the discovery of trans identities while or after exploring sexual minority identities. Some experimented with a range of gender and/or sexual minority labels, including non-binary or fluid identities, before settling on their current binary (trans) identity.

It’s really around the age of 16 that I started to feel unwell, because I did many coming outs. First, I came out as bisexual. Then, as homosexual, and now transgender. So that’s it. Personally, I thought at the beginning that I was homosexual. But [after coming out as homosexual] I didn’t feel better with my life. I though it would fix things but in fact, there was still something wrong and I didn’t know what it was. (Eloise, 16 year-old trans woman, traj. B)

Whether they gendered themselves differently through language, presentation or other behavior, the feedback youth received from their surroundings appeared to influence the rate and ease with which they pursued subsequent explorations. Positive feedback could lead to further gender exploration, while negative feedback could slow down their processes of exploration and affirmation. The opportunity to regularly access social spaces where they felt safe to express or explore their gender seemed to play an equally important role in facilitating gender exploration and consolidation.

Gender development trajectories

In addition to understanding how various processes facilitate gender identity realization and consolidation, this project allowed us to confirm findings that that we had previously identified in a smaller-scale Swiss companion study: three patterns that youth may go through in asserting their gender (Medico and Pullen Sansfaçon Citation2019; Medico et al., Citationin press). Indeed, we were able to discern different patterns in the age at which youth recount having started feeling discomfort in relation to their assigned gender, compared to the age where they first began to express and assert their gender to their parents and the rest of their social circle. While some participants said they knew their gender identity was different when they were very young, others said this awareness arose later in life, often at or after onset of puberty. The trajectories relate not only to the age youth started to realize their gender identity, but also to the presence or absence of constraints in their reflection and affirmation processes, and to the moment of their coming out. While these trajectory types are presented as three distinct categories, they need to be read with caution and should not be used to categorize youth or predict outcomes related to gender identity development. They should be used to help understand experiences, supports, and constraints to gender identity formation and consolidation and should be understood as non-linear, with many possibilities including advances and retreats, and further identity development.

Trajectory A: early dissonance, early affirmation and transition

Some youth in our project said they had begun questioning their assigned gender identity in early childhood and were allowed by their caregivers to explore and assert their gender identity at an early age. They generally asserted their trans identity in a sustained way to their wider social circle starting at an early age, with the support of one or both parents. Our sample includes a small number of youth (6) whose trajectories fall within this profile.

When I first realized I was still a baby. […] I used to tell my mom, “When I’m gonna be a girl, can I have that? When I’m gonna be a girl, can I have that?” [repetition from the interview] And when she asked me the questions “You think you’re gonna be a girl when you’re gonna be older?” I said “Yes.” (Elisa, 10 year-old girl, traj. A)

[And] Whenever I was in girl’s clothes, and then also like when I was able to talk, I would say that “I’m a boy”, and then I’d even ask stuff like, “Oh, hey! Where’s my penis? Why hasn’t it grown in yet?” Right? And then even when I got older and started understanding it more, I would say stuff like, “I’m a mistake. I’m a boy. It’s just, this isn’t, I’m a boy. I don’t know why you’re calling me this.” And that was always very, very young. (Joey, 13 year-old transgender male, traj. A)

Most youth who expressed their gender through this trajectory also describe having had to figure out their gender, experimenting with gender and getting feedback from others, specifically their parents. Despite being affirmed at an early age, they also described moments of questioning or pauses, as Sylvie explained earlier. However, the support they recall experiencing seems to have been conducive to early gender affirmation and consolidation, in contrast to the youth in the other two trajectories.

Trajectory B: early dissonance and delayed transition

Some youth recall questioning their assigned gender identity or feeling discomfort in relation to gender at a young age, but not asserting or exploring their gender identity until later. Our sample includes 17 youth whose trajectories fit this profile. In some cases, they describe having asserted their gender at a young age but then having stopped for a variety of reasons, including parental resistance or fear of experiencing issues in the broader social environment, such as at school. They often waited until they reached puberty or later before asserting their gender once again.

[Before I transitioned] I was like one of the few that like got bullied. […] At the time, I was like a kid. So I was like, “Oh god, god.” But I, I didn’t understand it. But whatever. And I just didn’t wanna put more attention to myself like I said, because of that. So I wanted to wait [to transition] until I got to high school. […] And um, I tried to hide my transition from like everyone. Like from like, my aunts, my uncles, my grandparents. (Anika, 15 year-old girl, traj. B)

While youth who came to understand their gender through this second trajectory described having always felt that something was “not right” regarding their gender (in relation to their gender assigned at birth or to social gender norms), it was only when puberty started that the process of meaning-making led them to better understand their gender identity. This process often occurred through discovering the existence of other trans people (in person or online) or recognizing their gender identity through the exploration of sexual minority identities.

Trajectory C: late experience of gender dysphoria

Some youth in our sample said that they only began to feel discomfort regarding their assigned gender when puberty began, or afterwards. Our sample includes 13 youth whose narrative seem to indicate that they only began experiencing discomfort through new gendered expectations and behavior in the youth’s social circle, and/or as puberty produced changes in their body that caused them distress/gender dysphoria. Several youth in this profile told us that they were mainly gender conforming or not concerned about gender norms during childhood and had previously not questioned their gender identity at all.

I didn’t really think much of [my gender identity growing up]. Uh, I, I guess I was pretty much just male, um, till like Grade 8 [roughly 13 years old] (Jessica, 16 year-old female, traj. C)

The onset of puberty was described as an important moment leading to gender dysphoria but also to experiences and reflection about the self, particularly around sexuality

[Gender] didn’t really matter because I had no concept of what was considered okay, was considered male or female. […] But it started to matter when people started to have crushes on people, and it started to matter when puberty started. And when the difference started to, when the people started to split off to the two groups, like the two gender groups. That’s when it changed. […] So that’s when I realized. (Scott, 16 year-old male/non-binary, traj. C)

As mentioned above, while young people in this research tend to largely describe experiences that follow one of the three trajectories described above, processes of exploration, assertion and consolidation of gender identity were not continuous or linear, even among those from the “early transition” Trajectory A profile. Many youth describe intermittent or circuitous trajectories including advances, pauses and retreats. For example, Joey, who asserted his gender identity and was affirmed by his parents at a young age, explains that though he sought and received gender affirming care at the specialty clinic before puberty (without medical treatment) he stopped transition after the process became overwhelming, resuming it several years later when his feelings of dissonance became too strong:

We had actually gone [to the specialty clinic] when I was really, really young [around 6], because I was feeling (inaudible) feelings, and then it got overwhelming, and I stopped for a while. And then finally, it was like a full year where I was, just didn’t even bring it up once. And then after that it was like: “I can’t take it. I’m done. I just, this has gotta happen.” […] I always knew [I was trans]. It was never a “no”. […] It just got to a point where it was, I just wanted to stop talking about it. That’s it. But I never changed my mind or anything. That’s never changed. (Joey, 13 year-old transgender male, traj. B)

Discussion

Moving forward in the development and consolidation of their gender identity required young people to become visible to others by extending their gendered self into the world (Pitcher, Citation2018), an inherently social process. Despite experiencing some dimensions of the process as being fundamentally personal, most of the dimensions that youth navigate in the process of affirming and consolidating their gender identity are social. Furthermore, our research demonstrates that despite young people’s gender being influenced both by individual and social processes, gender affirmation and consolidation is non-linear, for binary and non-binary youth alike, making theories and developmental models aimed at predicting outcomes unreliable. Our results suggest that gender identity development may be better understood not as a simple set of stages that every child must go through, but rather as a dynamic, nuanced, and fluid process that can continue throughout childhood and adolescence, significantly shaped by social dynamics and which may undergo pauses, advances and retreats. This echoes Fausto-Sterling (Citation2012, p. 404) who proposes that “gender identity development be placed in a dynamic embodied system framework”, and Riggs’s (Citation2019) invitation to move away from cisgenderist and developmentalist theories of understanding gender. Our data, combined with previous critiques of those models therefore lead us to reaffirm the importance of following the young person’s lead when supporting their gender identity development and, crucially, to challenge the idea that youth should be required to demonstrate a static gender identity before embarking on social or medical transition (Green, Citation2017; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2015; Wren, Citation2019). Recent research has clearly demonstrated the benefits of social and medical transition for youth (Olson et al., Citation2016; Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2019; Riggs et al., Citation2020), and trans-affirmative interventions should not be denied or delayed solely based on fear of regrets or uncertainty. Rather, interventions should focus on the actual needs of youth “because actual distress is very real, and future uncertainty is an inescapable reality of gender” (Ashley, Citation2019b, p. 228) and – of life. Indeed, we note that even young people who have been aware of their gender identity for many years may have moments where they question or even halt their gender transition in order to take more time to consolidate their gender identity. As these data highlight, only a small proportion of trans youth are fully aware and socially out before puberty and even this group may experience pauses and retreats.

Though it is common for trans youth to come out at puberty, for many this is not due to the “late onset” of dysphoric feelings or understanding themselves as trans or non-binary, it is the result of a long and difficult process (pathway B) toward accepting and understanding themselves in a social context where being trans is still a difficult reality. Our study therefore challenges the literature on “early onset” and “late onset” gender dysphoria and on “persisters” and “desisters” by showing that there exist more than two pathways that can be taken by youth who experience gender dysphoria and who “persist”, and many differences, including pauses and retreats, within groups of young people who might have been termed “persisters” or “desisters”.

Recognizing that gender identity development is not linear, our findings demonstrate the importance of examining youth gender identity development through longitudinal, contextualized, prospective studies. Our results show that what may for example be considered a situation of “desistance” at one point in a young person’s life may be better understood as a period of gender identity consolidation shaped by a variety of personal and social processes. Furthermore, it appears important to continue to develop scholarship around the questions of youth gender identity. Specifically, research should focus on young people’s own perspective, because while some youth may appear, from the outside, to suddenly affirm a different gender “out of the blue”, our project has shown that youth may in fact have experienced gender dysphoria for much longer before they were able to articulate it or assert it to others.

Many studies have demonstrated the importance of support for a youth’s gender identity as a predictor of well-being while also noting that more information is needed to understand what is experienced as effective or “strong” support by youth. For example, within social processes, the role of support (or lack thereof) seems to influence a youth’s capacity to explore, understand and assert their own identity, as was apparent in youth following Trajectories A and B. On the other hand, our research also shows how trans-positive and affirming spaces provide opportunity to make sense of and explore gender. The results of our studies echo those of Katz-Wise et al. (Citation2017) and Kuper et al. (Citation2018), who noted the importance of accessing information and support for trans identities within the process of self-discovery, and Kuper et al. (Citation2018) findings about meaning-making in the development of gender. The concept of metanarratives and their symbolic influence on youth gender identity, as pointed out by Bradford and Syed (Citation2019), could also help understand the process of self-discovery and affirmation in a non-linear way, especially when their gender disrupts metanarratives of transgender identity.

Limitations of the study

The sample of youth who participated in our study was limited in terms of cultural diversity, and participants were only selected through gender affirming care clinics. It is possible that youth who do not access gender affirming care have very different experiences. The sampling methods also resulted in recruitment of a group of youth who were willing to talk to researchers and who had parental support. Therefore, some young people who access clinics but do not wish to participate in a study about gender affirming care or who do not have parental support may negotiate their gender identity differently. Therefore, the study results cannot be generalized to a broader population of trans youth.

Conclusion

Whether they became conscious of their gender identity early in childhood or during adolescence, young people who participated in this study discussed how their gender identity development unfolds through non-linear processes that draw from both individual, deeply felt experience and their interaction with the social environment. The study has allowed us to shed light on some of the processes behind gender identity development and to gain a more nuanced understanding of different possible pathways. Notably, the study allowed us to realize that some youth who may initially say that their dysphoria only started with the onset of puberty may in fact have experienced challenges for much longer. The complexity of the interactions between the personal and social dimensions that were uncovered, and the variety of possible pathways taken by young people highlights the importance of centering the voices of trans youth in research that explores gender identity development. Since earlier findings of this same cohort of young people show that all participants benefited from the gender affirming medical care received (Pullen Sansfaçon et al. Citation2019), this article may also contribute to challenging the idea that treatment such as puberty suppression and hormones is only beneficial to those who “have suffered from lifelong extreme gender dysphoria” (Delemarre-van de Waal & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2006: 155), suggesting rather that it may be beneficial for a much broader group of young people.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press.

- Ashley, F. (2019a). The misuse of gender dysphoria: Toward greater conceptual clarity in transgender health. Perspectives on Psychological Science, doi:10.1177/1745691619872987

- Ashley, F. (2019b). Thinking an ethics of gender exploration: Against delaying transition for transgender and gender creative youth. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 223–236. doi:10.1177/1359104519836462

- Bradford, N. J., & Syed, M. (2019). Transnormativity and transgender identity development: A master narrative approach. Sex Roles, 81(5-6), 306–325. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0992-7

- Braun, V., & Clark, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bowen, G. A. (2019). Sensitizing concepts. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. A. Williams (Eds.), SAGE Research Methods Foundations. SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781526421036788357

- Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Klink, D. (2015). Adolescents with gender dysphoria. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 29(3), 485–495. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2015.01.004

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. doi:10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

- Devor, A. H. (2004). Witnessing and mirroring: A fourteen stage model of transsexual identity formation. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 8(1), 41–67. doi:10.1080/19359705.2004.9962366

- Delemarre-van de Waal, H. A., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2006). Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: a protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. European Journal of Endocrinology, 155(suppl_1), S131–S137. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02231

- Dey, I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Ehrensaft, E., Giammattei, S. V., Storck, K., Tishelman, A. C., & Keo-Meier, C. (2018). Prepubertal social gender transitions: What we know; what we can learn—A view from a gender affirmative lens. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 251–268. doi:10.1080/15532739.2017.1414649

- Floersch, J., Longhofer, J. L., Kranke, D., & Townsend, L. (2010). Integrating thematic, grounded theory and narrative analysis: A case study of adolescent psychotropic treatment. Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 9(3), 407–425. doi:10.1177/1473325010362330

- Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). The dynamic development of gender variability. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 398–441. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.653310

- Gray, K. E., & Walters, A. S. (2018). “And Then. Well. And Then I Became Me.”: Transgender Identities in Motion. In S. Vaughn (Ed.) Transgender youth: Perceptions, media influences and social challenges. (pp. 97–127). Nova Science Publishers.

- Green, R. (2017). To transition or not to transition? That is the question. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(2), 79–83. doi:10.1007/s11930-017-0106-5

- Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465–491. doi:10.1111/soin.12127

- Katz-Wise, S., Budge, S. L., Fugate, E., Flanagan, K., Touloumtzis, C., Rood, B., Perez-Brumer, A., & Leibowitz, S. (2017). Transactional pathways of transgender identity development in transgender and gender nonconforming youth and caregivers from the Trans Youth Family Study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 243–263. doi:10.1080/15532739.2017.1304312

- Kuper, L. E., Wright, L., & Mustanski, B. (2014). Stud identity among female-born youth of color: Joint conceptualizations of gender variance and same-sex sexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(5), 714–731. doi:10.1080/00918369.2014.870443

- Kuper, L. E., Wright, L., & Mustanski, B. (2018). Gender identity development among transgender and gender nonconforming emerging adults: An intersectional approach. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(4), 436–455. doi:10.1080/15532739.2018.1443869

- McConnell, E. A. (2018). Risking it anyway: An adolescent case study of trauma, sexual and gender identities, and relationality. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(1), 73–82. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1400134

- McGuire, J. K., Beek, T. F., Catalpa, J. M., & Steensma, T. D. (2019). The genderqueer identity (GQI) scale: Measurement and validation of four distinct subscales with trans and LGBQ clinical and community samples in two countries. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 289–304. doi:10.1080/15532739.2018.1460735

- McLean, K. C., Shucard, H., & Syed, M. (2017). Applying the master narrative framework to gender identity development in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 5(2), 93–105. doi:10.1177/2167696816656254

- Medico, D., & Pullen Sansfaçon, A. (2019). Les enfants et les jeunes trans. Canadian Association of Transgender Health Preconference training. November 1, 2019, Montreal. http://jeunestransyouth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CPATH_preconference_DMAPS-2019.pdf

- Medico, D., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Zufferey, A., Galantino, G., Et Bosom, M. The experiences of trans youth and their families in Switzerland: A journey to self-acceptance and gender affirmation. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. (in press)

- Nicolazzo, Z. (2016). ‘It's a hard line to walk’: black non-binary trans* collegians’ perspectives on passing, realness, and trans*-normativity. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(9), 1173–1188. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1201612

- Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20153223. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3223

- Olson-Kennedy, J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Kreukels, B. P. C., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Garofalo, R., Meyer, W., & Rosenthal, S. M. (2016). Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: Gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity, 23(2), 172–179. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000236

- Perry, D. G., Pauletti, R. E., & Cooper, P. J. (2019). Gender identity in childhood: A review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(4), 289–304. doi:10.1177/0165025418811129

- Pitcher, E. N. (2018). Being and becoming professionally other: Identities, voices, and experiences of U.S. trans* academics. Peter Lang Publishing. 10.3726/b12745

- Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Suerich-Gulick, F., Temple-Newhook, J., Feder, S., Lawson, M., Ducharme, J., Ghosh, S., & Holmes, C., On behalf of the Stories of Gender-Affirming Care Team. (2019). The experiences of gender diverse and trans children and youth considering and initiating medical interventions in canadian gender-affirming speciality clinics. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 371–387. doi:10.1080/15532739.2019.1652129

- Riggs, D. W., Bartholomaeus, C., & Sansfaçon, A. P. (2020). If they didn’t support me, I most likely wouldn’t be here’: Transgender young people and their parents negotiating medical treatment in Australia. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(1), 3–15. doi:10.1080/15532739.2019.1692751

- Riggs, D. W. (2019). Working with Transgender Young People and their Families A Critical Developmental Approach. Palgrave.

- Serano, J. (2016, August 2). Desistance, detransition and disinformation: A guide for understanding transgender children debates. Medium. https://medium.com/@juliaserano/detransition-desistance-anddisinformation-a-guide-for-understanding-transgenderchildren-993b7342946e

- Spivey, L. A., & Edwards-Leeper, L. (2019). Future directions in affirmative psychological interventions with transgender children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(2), 343–356. doi:10.1080/15374416.2018.1534207

- Steensma, T. D., Biemond, R., de Boer, F., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: A qualitative follow-up study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16(4), 499–516. doi:10.1177/1359104510378303

- Steensma, T. D., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2015). More than two developmental pathways in children with gender dysphoria? Letter to the editor. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(2), 147–148. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.016

- Steensma, T. D., Kreukels, B. P., de Vries, A. L., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2013). Gender identity development in adolescence. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 288–297. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.020

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications. doi:10.1080/15532739.2018.1456390

- Temple Newhook, J., Pyne, J., Winters, K., Feder, S., Holmes, C., Tosh, J., Sinnott, M.-L., Jamieson, A., & Pickett, S. (2018). A critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistance” theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 212–224. doi:10.1080/15532739.2018.1456390

- Turban, J. L., & Ehrensaft, D. (2018). Research review: Gender identity in youth: treatment paradigms and controversies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(12), 1228–1243. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12833

- Twist, J., & de Graaf, N. M. (2019). Gender diversity and non-binary presentations in young people attending the United Kingdom’s National Gender Identity Development Service. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 277–290. doi:10.1177/1359104518804311

- Wehrle, M. (2016). Normative Embodiment. The role of the body in Foucault’s genealogy. A phenomenological re-reading. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 47(1), 56–71. doi:10.1080/00071773.2015.1105645

- Wren, B. (2019). Ethical issues arising in the provision of medical interventions for gender diverse children and adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 203–222. doi:10.1177/1359104518822694