Abstract

Background: Testicular prostheses implantation may be used for neoscrotal augmentation in transgender men. In current literature, explantation rates range from 0.6% to 30% and most are a result of infection or extrusion. Information on the surgical path of individuals after prosthesis explantation is scarce.

Aim: To assess the frequency and success rate of testicular prosthesis implantation after previous explantation due to infection or extrusion.

Methods: All transgender men who underwent testicular prosthesis explantation between January 1991 and December 2018 were retrospectively identified from a departmental database. A retrospective chart study was conducted, recording demographics, surgical and prosthesis characteristics, reoperations, and outcomes.

Results: A total of 41 transgender men were included who underwent testicular prosthesis explantation in the study time period. Of these, 28 (68%) opted for new prosthesis implantation. Most explanted prosthesis had a volume ≥30cc and were replaced with an equally sized one. The postoperative course was uneventful in 19 out of 28 (68%) individuals. Explantation of one or both prostheses occurred in 7 out of 28 (25%) individuals, because of infection (n = 3, 11%) or extrusion (n = 4, 14%). Patients that experienced complications had more often a history of smoking (p = 0.049). The explantation rate was lower if a smaller or lighter prosthesis was reimplanted (p = 0.020).

Discussion: Most patients opt for testicular prosthesis implantation after previous explantation due to extrusion or infection. Explantation rates are higher than after the primary implantation procedure. Results of current study can be used to inform individuals on postoperative outcomes.

Introduction

Genital Gender-Affirming Surgery (gGAS) is performed in transgender men who opt for this in the gender affirming treatment process after meticulous psychological screening and hormonal therapy (Coleman et al., Citation2012). Generally, transgender men report an improved quality of life and satisfactory sexual function after gGAS (van de Grift et al., Citation2018; Wierckx et al., Citation2011).

Beyond phallic reconstruction (i.e. metaidoioplasty or phalloplasty), surgical construction of a neoscrotum (scrotoplasty) is an important component of creating male genitalia. Scrotoplasty can be performed in multiple ways, including use of pedicled skin flaps, myocutaneous flaps, free flaps, perineal advancement flaps, and labia majora skin flaps (DiGeronimo, Citation1982; Gilbert et al., Citation1988; Hage, Citation1996; Hage et al., Citation1993; Selvaggi et al., Citation2009; Sengezer & Sadove, Citation1993). Testicular prostheses may be used to augment the neoscrotum. Commonly reported issues associated with testicular implants in transgender men include explantation, due to infection or extrusion, and dislocation, for which relocalization is required (Pigot et al., Citation2019). In current literature, explantation rates range from 0.6 to 30% (Djordjevic & Bizic, Citation2013; Hage & van Turnhout, Citation2006; Kuehhas et al., Citation2015; Noe et al., Citation1978; Pigot et al., Citation2019; Schaff & Papadopulos, Citation2009; Stojanovic et al., Citation2017). After explantation, individuals may choose for reimplantation of a new prosthesis to achieve their desired result. It is unknown how many opt for reimplantation and clinical outcomes after explantation are lacking in current literature.

The objective of this study was to assess the success rate of implantation of testicular prostheses after explantation of testicular prostheses due to infection or extrusion in transgender men.

Methods

Study group identification

All transgender men with explantation of one or both testicular prostheses due to infection or extrusion between January 1991 and December 2018, were retrospectively identified from a departmental database. The study protocol was approved by the institutional medical ethical committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Center (registration number 2018678).

Retrospective chart study

The following data were recorded: patient demographics (age at implantation, body mass index, history of smoking, history of drug abuse, and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification); surgical characteristics (type of gGAS, type of scrotal reconstruction, type and size of the first implanted prostheses, direct or delayed implantation); and postoperative course (reason for explantation, reimplantation(s) yes/no, date of reimplantation(s), type of reimplanted prostheses, complications after reimplantation(s)). Testicular prosthesis was categorized as “small” (<15cc), “medium” (15–30cc), “large” (30 cc), or “weighted” (60 gr/steel).

Clinical follow-up was defined as the time between the date of implantation and the last outpatient clinic visit at either the plastic surgery or urology department.

Surgical technique

Intravenous cephalosporin was administered prior to surgery as per protocol antibiotic prophylaxis. During the study period, three methods of scrotal reconstruction were performed in our center, formerly described by Pigot et al. (Citation2019). In short, scrotal reconstruction was performed using one of the following methods:

the method described by Hage et al., with direct or delayed prosthesis implantation (Hage, Citation1996; Hage et al., Citation1993),

dorsally based V-shaped labia majora flaps, with delayed testicular implantation, or

the Hoebeke method consisting of cranially based labia majora flaps and a caudally based horse shoe flap from the pubic area, with delayed testicular implantation (Selvaggi et al., Citation2009).

In case of delayed testicular prosthesis implantation, either a mid-scrotal vertical or horizontal incision is made at the scrotophallic transition to create two separate pockets for implantation of the prostheses. The size of the prosthesis depends on patient preference, neoscrotal size and size of created pockets. shows an example of scrotal emptiness after a scrotoplasty according to Hoebeke. The final result of a phalloplasty and scrotoplasty with implantation of penile and testicular prostheses is shown in .

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS software Version 26 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for all statistical analyses. Outcomes were reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were summarized as either means with corresponding standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) depending on normality of distribution. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare dichotomous and categorical demographic variables. The unpaired-test was used to compare continuous demographic data. Two-tailed p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all statistical tests.

Results

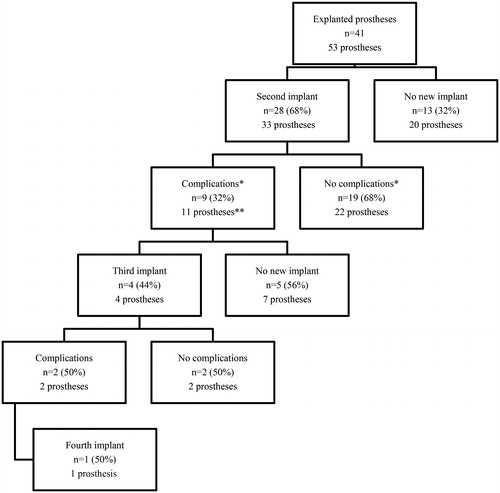

Data of 41 patients with 53 explanted testicular prostheses were included in the analyses (). Patient demographics are presented in . Median time of clinical follow-up was 15 years (IQR 17). Of the explanted prostheses, 16 (30%) were explanted due to infection and 37 (70%) due to extrusion. Median time to explantation was 2 months (IQR 7). Most primary explanted prosthesis were size “large” (49%) and 7 (13%) were “weighted.” All implanted prosthesis were silicone filled. In addition, “weighted” prosthesis is weighted with steel.

Figure 3. Flowchart of included patients, new implantations, and complications.

n = number of patients

*One patient with bilaterally implanted prostheses only had complications on one side.

**Of the newly implanted prostheses, 9 out of 11 were explanted and 2 out of 11 were relocalized.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

A total of 28 individuals (68%) opted for new prosthesis implantation (5 bilateral and 23 unilateral cases, ). Median time between the primary implantation and implantation of the new prosthesis was 11 months (IQR 15). Of the 33 newly implanted prostheses, 8 (24%) were smaller or lighter prosthesis, whilst 22 (67%) were similar sized or the same weight as the primary implanted prosthesis. The size of the other three prostheses was unknown.

The postoperative course was uneventful in 19 (68%) patients (22 prostheses, ). Complications occurred in nine patients (32%, 11 prostheses). In seven patients (25%), one or both prostheses were explanted; in three patients (11%, 4 prostheses) because of infection and in four patients (14%, 5 prostheses) because of extrusion. Two patients (7%) underwent relocalization of one prosthesis due to dislocation. All explanted prosthesis was similar sized as the primary implanted prosthesis, while none of the smaller sized or lighter prosthesis were explanted (p = 0.020). The amount of replacement with a smaller sized prostheses did not differ between patients with unilateral or bilateral replacement (p = 0.410).

Patients that experienced complications had more often a history of smoking compared to the patients without complications (9 out of 19 individuals vs. 8 out of 9 individuals, respectively; p = 0.049, ).

Four patients choose to undergo another implantation procedure where after two patients (50%) once more underwent explantation of the prosthesis due to complications. One patient choose to have a fourth implantation procedure ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report outcomes of reimplantation after complicated neoscrotal augmentation with testicular prostheses in transgender men. Most patients (68%) choose reimplantation of the lost prostheses. To some, augmentation of the neoscrotum was so important, they were willing to undergo multiple procedures and complications to achieve their goal. Complication rates were high in this population; 9 out of 28 patients (32%) experienced complications and 9 out of 33 newly placed prostheses (27%) were explanted. Generally, prostheses were replaced with an equally sized prosthesis, however, in this study, no complication occurred if a smaller or lighter prosthesis was placed.

A former study of our research group reported an explantation rate of 13% after primary prostheses implantation and also found a history of smoking as a predictor for explantation (Pigot et al., Citation2019). The explantation rate in our population (i.e. after previous explantation due to infection or extrusion) is twice as high. This is most likely the result of the selection of patients who already had complicated healing because of patient-related factors. Furthermore, a lack of enough (good quality) soft tissue to protect the prosthesis during the primary procedure or after infection may be the cause of the higher infection and extrusion rates after reimplantation. The former study also concluded that a trend can be seen toward delayed implantation (Pigot et al., Citation2019). A mid-scrotal vertical or horizontal incision is made at the scrotophallic transition to create two separate pockets for implantation of the prostheses in case of delayed implantation. Prostheses are closer to the newly created wound if a mid-scrotal incision is used, which might result in higher extrusion rates. During the past years, our scrotoplasty technique has changed requiring more tissue dissection. This could hypothetically lead to a more wound problems. Therefore, testicular prostheses are now implanted at least 6 months after gGAS. Nevertheless, groups in our data were too small to support this hypothesis.

Research on outcomes of health-related quality of life and body satisfaction after scrotoplasty and neoscrotal augmentation is scarce. Studies in patients with testicular cancer have reported that testicular integrity is equated with masculinity and that offering a testicular implant after orchiectomy results in less feelings of loss and uneasiness or shame (Gurevich et al., Citation2004; Skoogh et al., Citation2011). Levels of genital satisfaction in those who chose to receive a testicular prosthesis post orchiectomy are reported to be high (Nichols et al., Citation2019). In our study population, 28 out of 41 (68%) of the patients choose reimplantation of new prosthesis after previous explantation. Some were willing to undergo multiple surgical procedures and complication to achieve their goals, indicating that scrotal augmentation through testicular prostheses implantation is highly important for selected individuals.

Testicular prostheses are available in a variety of sizes to accommodate an individual patient.

Current practice at our center is that the surgeon decides during surgery which size prosthesis could be implanted, unless the patient has special (and feasible) desires. Also if patients opt for a second implantation procedure after explantation, the surgeon decides during counseling if it feasible to implant a new prosthesis and is this leads to the desired esthetic results. Over the past few years, we saw a trend toward the use of smaller and lighter testicular prosthesis (Pigot et al., Citation2019). In most transgender men in our study, medium or large sized prostheses were implanted. After explantation, most implants were replaced with an equally sized prosthesis whilst explantation rates were significantly lower in patients that had replacement with a smaller or lighter prosthesis in our study population.

It should be noticed that most patients underwent unilateral replacement of a prosthesis and that symmetry could have been one of the motivations for the replacement with a prosthesis of the same size. However, there was no difference in the amount of smaller reimplanted prostheses between patients with unilateral and bilateral replacement in our study population. In current literature, there is a lack of knowledge on patient motives regarding neoscrotal augmentation. With new scrotoplasty techniques, scrotal augmentation can be achieved by the use of pedicled fat flaps and if this leads to adequate patient satisfaction there might be no need for testicular prosthesis implantation. Nevertheless, the choice for an augmentation technique depends on the patient’s individual wishes, expectations, psychological, and physical state. From our experience, most transmen choose prosthesis not only for the physical appearance of the scrotum but also to improve their feeling of masculinity (Jacobsson et al., Citation2017).

More research on genital body image and health related quality of life after scrotal augmentation is necessary to accurately inform patients on the benefits of different techniques. Results of current study can be used to inform patients on neoscrotal augmentation techniques after complicated prostheses implantation. Our data show that after explantation, the implantation of smaller or lighter prosthesis should be recommended to reduce explantation rates. During counseling, patients have to be informed that they might need replacement from their other prosthesis to achieve symmetry.

Strengths of our study include the unique data on reimplantation of testicular prosthesis after explantation due to infection or extrusion in a relatively large study population and long clinical follow-up time. Also, results were collected in a specialized gender clinic. Limitations are its retrospective nature. Data on the motivation of individuals and caregivers for the implantation of new prosthesis after explantation are lacking.

In conclusion, most transgender men choose for a second testicular prostheses implantation procedure after explantation of testicular prostheses due to complications in this study. Healing was uneventful in 68% of the patients. Explantation rates due to infection or extrusion are higher than after a primary implantation procedure. The explantation rate was lower if a smaller or lighter prosthesis was reimplanted

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

- DiGeronimo, E. M. (1982). Scrotal reconstruction utilizing a unilateral adductor minimus myocutaneous flap. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 70(6), 749–751. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198212000-00018

- Djordjevic, M. L., & Bizic, M. R. (2013). Comparison of two different methods for urethral lengthening in female to male (metoidioplasty) surgery. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(5), 1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12108

- Gilbert, D. A., Winslow, B. H., Gilbert, D. M., Jordan, G. H., & Horton, C. E. (1988). Transsexual surgery in the genetic female. Clinics in Plastic Surgery, 15(3), 471–487. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3292116

- Gurevich, M., Bishop, S., Bower, J., Malka, M., & Nyhof-Young, J. (2004). (Dis)embodying gender and sexuality in testicular cancer. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 58(9), 1597–1607. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00371-X

- Hage, J. J. (1996). Metaidoioplasty: An alternative phalloplasty technique in transsexuals. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 97(1), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199601000-00026

- Hage, J. J., Bouman, F. G., & Bloem, J. J. (1993). Constructing a scrotum in female-to-male transsexuals. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 91(5), 914–921. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199304001-00029

- Hage, J. J., & van Turnhout, A. A. (2006). Long-term outcome of metaidoioplasty in 70 female-to-male transsexuals. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 57(3), 312–316. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000221625.38212.2e

- Jacobsson, J., Andreasson, M., Kolby, L., Elander, A., & Selvaggi, G. (2017). Patients' priorities regarding female-to-male gender affirmation surgery of the genitalia - A pilot study of 47 patients in Sweden. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(6), 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.005

- Kuehhas, F., De Luca, F., Spilotros, M., Richardson, S., Garaffa, G., Ralph, D., & Christopher, N. (2015). Patient reported outcomes after metoidioplasty. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 37–37.

- Nichols, P. E., Harris, K. T., Brant, A., Manka, M. G., Haney, N., Johnson, M. H., Herati, A., Allaf, M. E., & Pierorazio, P. M. (2019). Patient decision-making and predictors of genital satisfaction associated with testicular prostheses after radical orchiectomy: A questionnaire-based study of men with germ cell tumors of the testicle. Urology, 124, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.09.021

- Noe, J. M., Sato, R., Coleman, C., & Laub, D. R. (1978). Construction of male genitalia: The Stanford experience. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 7(4), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542038

- Pigot, G. L. S., Al-Tamimi, M., Ronkes, B., van der Sluis, T. M., Özer, M., Smit, J. M., Buncamper, M. E., Mullender, M. G., Bouman, M.-B., & van der Sluis, W. B. (2019). Surgical outcomes of neoscrotal augmentation with testicular prostheses in transgender men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(10), 1664–1671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.020

- Schaff, J., & Papadopulos, N. A. (2009). A new protocol for complete phalloplasty with free sensate and prelaminated osteofasciocutaneous flaps: Experience in 37 patients. Microsurgery, 29(5), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.20647

- Selvaggi, G., Hoebeke, P., Ceulemans, P., Hamdi, M., Van Landuyt, K., Blondeel, P., De Cuypere, G., & Monstrey, S. (2009). Scrotal reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals: A novel scrotoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 123(6), 1710–1718. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a659fe

- Sengezer, M., & Sadove, R. C. (1993). Scrotal construction by expansion of labia majora in biological female transsexuals. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 31(4), 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-199310000-00016

- Skoogh, J., Steineck, G., Cavallin-Stahl, E., Wilderang, U., Hakansson, U. K., Johansson, B., & Stierner, U, & Swenoteca. (2011). Feelings of loss and uneasiness or shame after removal of a testicle by orchidectomy: A population-based long-term follow-up of testicular cancer survivors. International Journal of Andrology, 34(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01073.x

- Stojanovic, B., Bizic, M., Bencic, M., Kojovic, V., Majstorovic, M., Jeftovic, M., Stanojevic, D., & Djordjevic, M. L. (2017). One-stage gender-confirmation surgery as a viable surgical procedure for female-to-male transsexuals. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(5), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.03.256

- van de Grift, T. C., Elaut, E., Cerwenka, S. C., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Kreukels, B. P. C. (2018). Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: A follow-up study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190

- Wierckx, K., Van Caenegem, E., Elaut, E., Dedecker, D., Van de Peer, F., Toye, K., Weyers, S., Hoebeke, P., Monstrey, S., De Cuypere, G., & T'Sjoen, G. (2011). Quality of life and sexual health after sex reassignment surgery in transsexual men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(12), 3379–3388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02348.x