Evaluating gender identity is an essential part of providing care to children seeking specialist gender services (Bloom et al., Citation2021; Coleman et al., Citation2022; Johnson et al., Citation2004). However, the number and quality of validated and culturally appropriate tools for assessing gender identity in children and adolescents are limited (Bloom et al., Citation2021). For example, in a recent systematic review, Bloom et al. (Citation2021) observed that – of six tools previously used to assess gender identity in children and adolescents – only a single instrument catered for non-binary gender identities, and only two had been validated by rigorous psychometric analysis.

The parent-reported Gender Identity Questionnaire (GIQ) for children (Johnson et al., Citation2004) was developed in 2004 to aid in the assessment of gender identity development and was based on an earlier set of questions devised by Elizabeth and Green in 1984 (Elizabeth & Green, Citation1984). The GIQ measures gender expression and gender identity in children between the ages of 3–12 years (Johnson et al., Citation2004). It is the best validated of the available tools to assess gender in this age group (Bloom et al., Citation2021), with high cross-national and cross-clinic reliability (Cohen-Kettenis et al., Citation2006) and the ability to differentiate between children who met the relevant DSM criteria for gender identity disorder (GID) compared to children who were subthreshold for GID at the time of its development in 2004 (Johnson et al., Citation2004). Although the GIQ has been criticized for the outdated nature of some of its questions (Bloom et al., Citation2021) – for instance, it asks about play with “girl-type dolls, such as Barbie” and “boy-type dolls, such as G.I. Joe” and also uses pronouns that reflect the child’s sex assigned at birth – it remains in common clinical use today.

However, given the substantial shifts in attitudes toward gender diversity that have occurred in recent years, we have found interpretation of the standard GIQ scoring system rather challenging. Reasons for this are twofold: firstly, the scoring of the GIQ is based upon stereotypic representations of gender that often do not apply today, and secondly, it is based on the notion that gender diversity is pathological. In this editorial, we therefore propose a modification to how the GIQ is scored and, by doing so, allow it to be interpreted in a manner that is gender-affirming and also caters to children with a non-binary identity.

A proposed revision for administering and scoring the GIQ

The GIQ consists of 16 items of which 14 items were recommended for calculating a mean score based on factor analysis (Johnson et al., Citation2004). These items were originally developed based on common expressions of gender role behaviors which on average differentiate the behaviors of girls and boys (Elizabeth & Green, Citation1984; Johnson et al., Citation2004). For each item, the response options are on a 5-point scale (see Appendix for more information). Pronouns within the questions are changed according to the sex assigned at birth. Subsequently, some items are reverse scored based on the child’s sex assigned at birth. A mean score between 1 and 5 is calculated for all 14 items excluding the items where there were missing responses or option “f” (which tends to indicate that the scenario was not applicable) was selected, with lower scores indicative of greater “cross-gendered behaviour” to use the language of the original authors (Johnson et al., Citation2004).

We propose a revision of the GIQ that 1) reverts to using all 16 original items since item 8, “He (she) plays sports with girls (but not boys)” and item 16, “He (she) talks about liking his (her) sexual anatomy (private parts)” which were excluded based on facto analysis, are complementary to item 7, “He (she) plays sports with boys (but not girls)” and item 15, “He (she) talks about not liking his (her) sexual anatomy (private parts)” respectively; 2) uses they/their pronouns instead of he/his or she/her across all the items, thus removing the need for two different versions of the questionnaire based on assigned gender, which is currently the case; 3) reverse scores items 10, 11, 15 (for children assigned female at birth) and 16 (for children assigned female at birth) of the original questionnaire for assigned males to calculate a mean score (see Appendix for more information). With this alternative scoring system, higher scores are indicative of more masculine gender expression/identity, lower scores are indicative of more feminine gender expression/identity, and intermediate scores are indicative of more gender-neutral expression/identity.

Association between alternative GIQ scores and gender identity data

While the original GIQ scoring system helps to indicate gender diversity, we hypothesized that our alternative scoring system would provide greater insight into a child’s actual gender identity and expression. To test this, we examined the association between alternative GIQ scores and gender identity using data from Trans20, a longitudinal study of transgender and gender diverse (henceforth, trans) young people in Victoria, Australia (Tollit et al., Citation2019). As part of Trans20, we collected GIQ data from 168 parents/caregivers as well as matched gender identity information from their children, who were aged between 3 and 12 years at the time of their initial attendance at the Royal Children’s Hospital Gender Service (Melbourne, Australia) between February 2017 and January 2020.

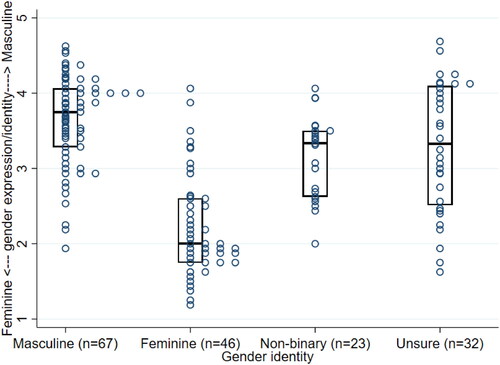

shows the distribution of alternative GIQ scores grouped by gender identity, which was determined as previously described (Blacklock et al., Citation2021). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that children with different gender identities displayed different scoring profiles. The majority of trans girls (with a feminine gender identity, n = 46) scored at the more feminine end of the scale, with a median score of 2.0 (interquartile range (IQR) 1.8–2.6). Similarly, the majority of trans boys (masculine gender identity, n = 67) scored at the more masculine end of the scale (median score 3.8, IQR 3.3–4.1). Children with a non-binary gender identity (n = 23) as well as those who were unsure of their gender identity (n = 32) showed an intermediate score profile, with the median score of 3.3 (IQR 2.6–3.5) and 3.3 (IQR 2.5–4.1) respectively lying close to halfway between the masculine and feminine poles.

Discussion

In light of the known limitations of the GIQ for children, we propose an alternative administration and scoring system for the GIQ. Our alternative approach carries several potential advantages. Firstly, the use of they/their pronouns will provide a universal, gender-neutral instrument which avoids misgendering the child (at present, the questionnaire uses birth-assigned pronouns as a default). Secondly, the alternative scoring system helps to provide a measure of gender expression/identity on a continuum, which is consistent not only with more modern concepts of gender but is also in keeping with some recently developed tools, such as the Gender Diversity Questionnaire and Perth Gender Picture, which assess gender identity on a continuous scale (Moore et al., Citation2021; Twist & de Graaf, Citation2019). Finally, our revised scoring system shifts the interpretation of the tool from focusing on a child’s behavior with respect to their sex assigned at birth and instead reflects a child’s current gender identity and expression which is more gender affirming.

Nevertheless, we are aware of the limitations of our approach. One is that the data used to test our new scoring system was solely derived from trans and gender-diverse children. While this enabled us to assess how the alternative scores for such children aligned with different gender identities, having data from cis-gender children as well would be informative. Another limitation of our revised approach is that we did not attempt to update those items whose language and concepts are outdated and/or based on gender stereotypes that are much less applicable today (such as the idea that there are distinct “boy-type” or “girl-type” games). Such a modification to the GIQ would require a much more extensive undertaking, but hopefully the relatively simple revision presented here goes some way to modernizing the tool and improving its usability.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Pang is a member of the editorial board of Transgender Health. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blacklock, C., McGlasson, C., Chew, D., Murfitt, K., & Hoq, M. (2021). Challenges in measuring gender identity among transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary young people. Public Health, 200, e4–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.09.012

- Bloom, T. M., Nguyen, T. P., Lami, F., Pace, C. C., Poulakis, Z., Telfer, M., Taylor, A., Pang, K. C., & Tollit, M. A. (2021). Measurement tools for gender identity, gender expression, and gender dysphoria in transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents: a systematic review. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 5(8), 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(21)00098-5

- Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Wallien, M., Johnson, L. L., Owen-Anderson, A. F. H., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2006). A parent-report gender identity questionnaire for children: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11(3), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104506059135

- Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Fraser, L., Goodman, M., Green, J., Hancock, A. B., Johnson, T. W., Karasic, D. H., Knudson, G. A., Leibowitz, S. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Monstrey, S. J., Motmans, J., Nahata, L., … Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(sup1), S1–S259. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- Elizabeth, P. H., & Green, R. (1984). Childhood sex-role behaviors: similarities and differences in twins. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae, 33(2), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0001566000007200

- Johnson, L. L., Bradley, S. J., Birkenfeld-Adams, A. S., Kuksis, M. A. R., Maing, D. M., Mitchell, J. N., & Zucker, K. J. (2004). A parent-report gender identity questionnaire for children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000014325.68094.f3

- Moore, J. K., Thomas, C. S., van Hall, H. W., Strauss, P., Saunders, L. A., Harry, M., Mahfouda, S., Lawrence, S. J., Zepf, F. D., & Lin, A. (2021). The Perth Gender Picture (PGP): Young people’s feedback about acceptability and usefulness of a new pictorial and narrative approach to gender identity assessment and exploration. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1795960

- Tollit, M. A., Pace, C. C., Telfer, M., Hoq, M., Bryson, J., Fulkoski, N., Cooper, C., & Pang, K. C. (2019). What are the health outcomes of trans and gender diverse young people in Australia? Study protocol for the Trans20 longitudinal cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 9(11), e032151. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032151

- Twist, J., & de Graaf, N. M. (2019). Gender diversity and non-binary presentations in young people attending the United Kingdom’s National Gender Identity Development Service. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518804311

APPENDIX

Table A1. Gender Identity Questionnaire: Original and proposed questionnaire and scoring system