Abstract

Background: There is currently limited data regarding the physical activity behaviors of trans and gender diverse people (including binary and non-binary identities; henceforth trans). The aim of this review was to synthesize the existing literature in this area, with a focus on physical activity behaviors as they relate to health (e.g. health benefits, risks of adverse health outcomes).

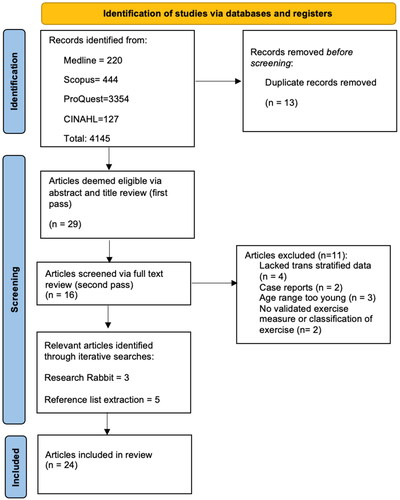

Methods: A scoping review protocol was used to search Medline, Scopus, ProQuest, and CINAHL in order to identify qualitative and quantitative articles, published as of September 2023, that reported physical activity behaviors in trans adults. Quality assessments were conducted based on standard criteria.

Results: Twenty-four articles were included in the final analysis, with methodological quality ranging from 0.45 to 0.95 on a scale ranging from 0.0 (low quality) to 1.0 (high quality). Five articles reported low levels of physical activity compared to global health recommendations and one article reported physical activity exceeding the minimum recommendation. Nine articles reported lower levels of physical activity in trans people compared to cisgender people, whereas two reported similar levels of physical activity and one reported higher levels in trans people. A total of 12 different measures were used to assess physical activity levels, of which only seven were validated measures. Seven articles reported compulsive exercise in trans people and five articles reported physical health risks in a sample of trans people with low physical activity levels. Five articles reported physical activity levels influenced by gender congruence or body satisfaction. Six articles reported physical activity influenced by minority stress, experienced discrimination, or anticipated discrimination.

Discussion: This review highlights the need for further research regarding the physical activity behaviors of trans individuals, especially with regard to the impact on health (e.g. excessive, or insufficient levels of activity) and consideration of consistency of physical activity measures and reporting. The findings suggest a need to consider the unique influences on physical activity participation in this population when providing services and/or promoting physical activity in support of health.

Introduction

The term trans refers to any individual whose gender identity and sex assigned at birth do not match. Gender diverse is a subset under the trans umbrella that more explicitly includes non-binary, gender questioning, and other diverse gender identities. Conversely, cisgender refers to a person whose gender identity is the same as their sex assigned at birth (i.e. not trans or gender diverse). Trans and gender diverse (including binary and non-binary identities; henceforth trans) individuals may also use a wealth of other terms to describe their identity, including culturally specific terms such as Brotherboy, Sistergirl, Two-spirit, and Hijra (Public Broadcasting Service, 2015).

Trans people experience higher rates of mental health issues compared to their cisgender counterparts. One Australian study reported that 74.6% of young trans people had been diagnosed with depression, 72.2% with anxiety, and 22.7% with an eating disorder (Strauss et al., Citation2020). In this same study, nearly 50% of participants had attempted suicide (Strauss et al., Citation2020). Similarly, a United States study of trans adults reported a 41% suicide attempt rate (Grant et al., Citation2011).

These high rates of mental health challenges can be attributed to experiences of discrimination rather than being inherent to being trans (Bockting et al., Citation2013; Reisner et al., Citation2016; Strauss et al., Citation2020; Testa et al., Citation2015). Trans individuals experience discrimination across various domains of life including healthcare, employment, and housing (Grant et al., Citation2011; Shires et al., Citation2018; Strauss et al., Citation2020). For example, almost 90% of trans young people in Australia have experienced peer rejection and more than one in five have experienced homelessness (Strauss et al., Citation2020). In the United States, trans people are twice as likely to be unemployed (Grant et al., Citation2011). Additionally, the many stressors experienced by trans people are reported to impact their health behaviors including tobacco use, drug use, diet, and physical activity levels, in turn contributing to worse physical health outcomes (Streed et al., Citation2021). In combination with these behaviors, medical care pursued by trans people in order to medically affirm their gender may also impact physical health risks (Streed et al., Citation2021).

Physical activity in the broadest sense encompasses any bodily movement that requires energy expenditure and incorporates structured exercise, unstructured activities, active transport, and active recreation. Participation in physical activity is widely endorsed as a positive health behavior with beneficial impacts on both physical and mental health (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). The WHO recommends a minimum of 150 min of physical activity per week (WHO, Citation2020) for the adult population to support health, with potential negative impacts on morbidity and mortality for individuals falling significantly below these levels (e.g. sedentary individuals). There are also potential health concerns related to excessive or compulsive levels of exercise (Lichtenstein et al., Citation2017), which have received limited attention in the literature to date. Recent reviews (Jones et al., Citation2017; Oliveira et al., Citation2022) and a meta-synthesis (Pérez-Samaniego et al., Citation2019) have reported individual and systemic barriers that impact trans participation in physical activity. However, these articles did not report specific physical activity levels nor explore participation levels as they relate to meeting or not-meeting health guidelines (e.g. sedentary or excessive exercise).

The aim of this review is to map the current literature on physical activity behaviors in trans and gender diverse adults with a focus on behaviors as they relate to health (e.g. meeting or not meeting physical activity recommendations for health). Specifically, this review aims to; 1) synthesize and compile the information on levels of physical activity in trans adults; 2) report on this information in regard to the impact on health (e.g. impact of sedentary or excessive/compulsive exercise); 3) note factors that authors reported to influence activity levels in trans people; and 4) conduct a quality assessment on the included articles to report on the methodological quality of the identified literature. The scoping review method was selected for this review given the relative dearth of research or existing reviews on the topic which report on physical activity levels and associated health considerations in trans people.

Inclusion criteria

This review included empirical studies published in English that examined the physical activity behaviors of trans and gender diverse people aged 16 or older. Included articles needed to have a mean participant age of 18 or older and a minimum age of 16. The inclusion of 16 and 17-year-old participants within an adult inclusion criterion was based on the legal concept of ‘mature minor’ status seen in countries including the United States, Canada, and Australia. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodological approaches were eligible for inclusion. Quantitative articles needed to include a measure of physical activity that was comparable to a normative measure (e.g. minutes of activity per day), or a classification of physical activity based on a validated assessment methodology (e.g. validated survey tool, objective assessment of activity). Qualitative articles needed to report physical activity behaviors in trans people. Articles that included cisgender or varied gender participants needed to provide stratified data of the physical activity behaviors of trans people within the sample. For qualitative studies, quotes and themes needed to indicate when these were derived from trans participants. Articles were excluded if they focused on the fairness or inclusion of trans people in sport or reported broader lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning, and asexual (LGBTIQA+) physical activity data without stratified trans datasets.

Search strategy

A database search of Medline, Scopus, ProQuest, and CINAHL was conducted using a string search created in collaboration with a university librarian. This search string consisted of three key categories of terms: physical activity behavior terms (Over-exercis* OR Exercis* OR Physical Activit* OR Sport OR Compulsive exercis* OR Exercise addiction OR Excessive exercis* OR Unhealthy exercis*), gender identity terms (Transgender* OR Transsexual* OR Gender identit* OR Gender dysphori* OR “Gender diverse” OR Gender fluid OR Non-Binary OR Sistergirl OR Brotherboy OR Two spirit), and age-related terms (Young adult* OR Adult). Search terms were truncated, exploded, and modified for use on each database due to the variations in the design and configuration of databases, without altering the principal content of the search. The original search was completed in December 2022, with an additional search completed in September 2023 (see ).

Data extraction

Data extraction and charting were completed by the first author (KS) with key characteristics of interest identified by the research team prior to data extraction. The first author recorded the following characteristics of each article: year of publication, country, study design, participant age range, gender identity of participants, number of participants, key findings, inclusion/exclusion of non-binary participants, comparison group, and physical activity measure/s utilized. Assessment of methodological quality was conducted by KS and BF independently using the tools and guidelines developed by Kmet et al. (Citation2004). This tool uses a 10-item checklist for qualitative studies and a 14-item checklist for quantitative studies to assess methodological quality. Studies were scored against each criterion with a ‘yes’ =2, ‘partial’ = 1, ‘no’ = 0, or N/A when appropriate. A score of methodological quality was calculated by subtracting the total score of each study from the total possible score. This calculation created a score from 0.0 to 1.0, with higher scores indicating higher quality. Discrepancies in quality assessment findings were resolved through discussion between the reviewers with a third reviewer (FA) resolving any disagreements between their conclusions to create final methodological quality assessment scores (see ).

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Results

Article characteristics

Of the 24 final articles, 17 (70.83%) were quantitative, four (16.67%) were qualitative, and three (12.5%) were mixed methods. Twenty-two (91.67%) of the included articles were published in the past ten years. Thirteen (54.17%) articles were conducted in the United States of America, with the remaining articles conducted in Italy, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Australia, Finland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Norway.

Only eight (33.33%) articles explicitly included non-binary participants, with the remaining 16 (66.66%) articles including only binary trans men, trans women, or not specifying. However, it is worth acknowledging that non-binary participants were likely participants in all articles but were not reported due to the gender categories offered by the articles. Within the 14 (58.33%) articles that provided a comparison group, four compared trans participants to cisgender participants of the same gender identity, four compared trans participants to cisgender participants of the same sex assigned at birth, two compared trans participants to cisgender participants without stratification by gender identity or sex, one compared trans participants to cisgender participants of both the same sex assigned at birth and gender identity, one compared trans participants to lesbian, gay, and bisexual cisgender participants, one compared trans participants to lesbian, gay, and bisexual cisgender participants and cisgender heterosexual participants, and one compared non-binary participants to binary trans men and trans women, as well as cisgender men and women.

Seven (29.17%) articles used a validated measure to determine physical activity levels. Three (12.50%) articles utilized the Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire (Baecke et al., Citation1982), and individual articles used each of the following; the Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (Topolski et al., Citation2006), the Yale Physical Activity Survey (DiPietro et al., Citation1993), International Physical Activity Questionnaire (Hagströmer et al., Citation2006), and the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (Godin & Shephard, Citation1985). A further five (20.83%) articles used non-validated measures to determine physical activity with between one and three-item questionnaires (e.g. “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises, such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?”; Cunningham et al., Citation2018) (see ).

Physical activity levels

Eight quantitative articles (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2018; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Muchicko et al., Citation2014; Smalley et al., Citation2016; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a; Citation2013b; Vilas et al. Citation2014) and one mixed methods article (Sedlak et al., Citation2017) provided direct measures of physical activity levels in trans people. Of these, only one article reported trans people were sufficiently ‘active’ (Muchicko et al., Citation2014). Five quantitative articles (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2018; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Smalley et al., Citation2016; Vilas et al., Citation2014) and one mixed methods article (Sedlak et al., Citation2017) reported physical activity levels below recommendations. However, the authors of each article utilized different recommendations for what constituted adequate physical activity (see ). Three quantitative articles provided measures that could not be interpreted for comparison to physical activity recommendations, as they used a measure applicable only for comparison between groups only (Lapauw et al., Citation2008; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a; Citation2013b).

Alzahrani et al. (Citation2019) reported 41.7% of trans men (p = 0.09) and 41.7% of trans women (p= <0.01) met WHO exercise recommendations. Sedlak et al. (Citation2017) reported an average of 16.67 min of physical activity per day, which was below the 30-minute-per-day recommendation utilized by the article. Smalley et al. (Citation2016) utilized the recommendation of a minimum of 20 min per day three days per week physical activity and found 41% of non-binary people, 36.9% of trans men, and 24.3% of trans women met this lowered recommendation (Smalley et al., Citation2016). Vilas et al. (2015) reported physical activity level assessment scores of 1.41 ± 0.46 for trans women and 1.38 ± 0.43 for trans, with a score below 1.7 considered sedentary (Vilas et al., Citation2014). Cunningham et al. (Citation2018) reported no physical activity in the past month for 43.3% of trans women, 31% of trans men, and 27.8% of gender non-conforming trans people. Similarly, Downing and Przedworski (Citation2018) reported no past month physical activity in 38.7% of trans women, 34.1% of gender non-conforming trans people, and 30.8% of trans men.

Nine quantitative articles reported lower levels of physical activity in trans participants compared to cisgender participants (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Cunningham et al., Citation2018; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2018; Lapauw et al., Citation2008; Muchicko et al., Citation2014; Smalley et al., Citation2016; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a; Wilson et al., Citation2023). However, this disparity only reached statistical significance in five articles (Cunningham et al., Citation2018; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2018; Lapauw et al., Citation2008; Smalley et al., Citation2016; Wilson et al., Citation2023). Alzahrani et al. (Citation2019) reported statistically significant differences between physical activity levels in trans women compared to cisgender men (p= <0.01), but the reduced physical activity in trans men compared to cisgender women did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09). Downing and Przedworski (Citation2018) reported statistically significant differences in physical activities between trans men and cisgender men (p < 0.01), trans men and cisgender women (p < 0.05), and gender non-conforming trans people and cisgender men (p < 0.05). Lapauw et al. (Citation2008) reported reduced sport-related physical activity (p = 0.008) in trans women compared to cisgender men. Smalley et al. (Citation2016) reported reduced physical activity levels in trans women compared to both cisgender men and cisgender women (p<.05). Wilson et al. (Citation2023) reported reduced levels of aerobic physical activity in trans women compared to cisgender men (99.99% CI, p = 0.001). Jones et al. (Citation2018) reported lower levels of physical activity in trans people compared to cisgender people (p = 0.010). However, when compared only to cisgender people of the same gender identity, a statistically significant difference was only found for trans men compared to cisgender men (p = 0.041) (Jones et al., Citation2018).

One quantitative article reported higher levels of physical activity in non-binary participants compared to both binary trans people and cisgender people (Smalley et al., Citation2016). Two quantitative articles reported no significant difference in physical activity levels between trans people and cisgender peers (Ceolin et al., Citation2023; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013b).

Of the five quantitative articles (Krueger et al., Citation2021; Nagata et al., Citation2020a; Citation2020b; Uniacke et al., Citation2021; Velez et al., Citation2016), one qualitative article (Teti et al., Citation2020), and one mixed-methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) that measured compulsive exercise, all (100%) articles reported compulsive or excessive exercise within trans populations. However, none of these articles utilized an objective measure of physical activity levels that could be compared to public health recommendations, but rather measured disordered motivations and attitudes related to exercise. Two quantitative articles utilized the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (Nagata et al., Citation2020a; Nagata et al., Citation2020b;), one quantitative article adapted multiple eating disorder questionnaires (Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, SCOFF questionnaire, and self-reported symptoms) (Uniacke et al., Citation2021), one quantitative article utilized the Compulsive Exercise Test (Velez et al., Citation2016), one quantitative article asked participants a yes/no question about using ‘over exercise’ as a coping strategy (Krueger et al., Citation2021), and one qualitative article (Teti et al., Citation2020), and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) described compulsive exercise within their participants without a specific measure. Reported rates of compulsive exercise ranged from 5.8% (Krueger et al., Citation2021) to 40% (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) of the samples.

Health risks related to physical activity levels

Five quantitative articles (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Downing & Przedworski; Vilas et al., Citation2014; Ceolin et al., Citation2023; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a) and one mixed methods article (Sedlak et al., Citation2017) reported physical health risks in a cohort of trans people with low physical activity levels. However, only one quantitative article reported a statistically significant association between low physical activity levels and health risks (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019).

Three quantitative articles reported an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease in trans people compared to cisgender people (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Vilas et al., Citation2014). Downing and Przedworski (Citation2018) reported trans women to have 2.068 times (95% CI, 1.366-3.133, p < 0.01) the odds of cardiovascular events (i.e. coronary heart disease or myocardial infarction) compared to cisgender women, but similar risk to cisgender men. In contrast, trans men were 1.895 times (95% CI, 1.240-2.894, p < 0.01) more likely to experience cardiovascular events than cisgender women but had similar risk to cisgender men (Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018). However, gender non-conforming trans people were at the greatest risk of cardiovascular events, with 2.305 times (95% CI, 1.098-4.841, p < 0.05) the risk of cisgender men and 6.415 times (95% CI, 2.325-17.702, p < 0.01) the risk of cisgender women (Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018). In this article, trans people were more likely to have not exercised in the past 30 days, but analysis for any association between lack of physical activity and cardiovascular health or events was not reported (Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018).

Alzahrani et al. (Citation2019) compared cardiovascular events risk of trans people to that of cisgender people. After multivariate analysis, trans men were 2.53 times more likely than cis men (95% CI, 1.14–5.63; p = 0.02) and 4.9 times more likely than cis women (95% CI, 2.21–10.90; p < 0.01) to experience cardiovascular events (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). Trans women were 2.6 times more likely to experience cardiovascular events than cisgender women (95% CI, 1.78–3.68; p < 0.01), but had a similar likelihood to cisgender men (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). Meeting physical activity guidelines had a protective effect on the risk of cardiovascular events in trans people, with those meeting the recommendations were reported to have a 19% reduced likelihood (95% CI, 0.76-0.87, p= <0.01) of cardiovascular events (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). Vilas et al. (Citation2014) described low levels of physical activity as a cardiovascular risk factor for their trans sample but did not measure for any association.

Two quantitative articles reported diabetes in their sample of trans people with low levels of physical activity (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019; Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018). In both articles, trans people were more likely to have diabetes than cisgender participants. However, Alzahrani et al. (Citation2019) only found a statistically significant difference when comparing trans women to cisgender women (p=.04). Similarly, Downing and Przedworski (Citation2018) only found a statistically significant difference when comparing gender non-conforming trans people to cisgender women (AOR = 1.728, 95%CI, p<.05).

Two quantitative articles (Ceolin et al., Citation2023; Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a) and one mixed-methods article (Sedlak et al., Citation2017) reported the risk of bone health issues. Sedlak et al. (Citation2017) investigated osteoporosis risk in a sample of trans people and reported daily vigorous physical activity level (16.67 min) of approximately half the recommended amount for osteoporosis prevention provided by the authors. Ceolin et al. (Citation2023) compared the bone mineral density of cisgender adults and trans adults prior to commencing hormone therapy. Trans people assigned female at birth had reduced bone mineral density in their femur and femoral neck compared to cisgender women (Ceolin et al., Citation2023). Trans people assigned male at birth had reduced lumbar, femur, and femoral neck bone mineral density compared to cisgender men (Ceolin et al., Citation2023). Despite these findings, a significant correlation between physical activity levels and bone mineral density was not found (Ceolin et al., Citation2023). Similarly, Van Caenegem et al. (Citation2013b) measured the bone mass of trans women prior to hormone therapy commencement and reported reduced bone mass compared to cisgender men and hypothesized that reduced physical activity was a contributor to this reduced bone mass (Van Caenegem et al., Citation2013a).

One quantitative article reported the risk of kidney disease in trans people with low levels of physical activity (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). This article reported kidney disease in 3.7% of trans men and 3.5% of trans women (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). This rate was higher than that of cisgender participants but did not reach statistical significance (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019). However, this article did not measure for an association between low physical activity levels and kidney disease (Alzahrani et al., Citation2019).

Three quantitative articles (Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2018; Krueger et al., Citation2021), one qualitative article (Jones et al., Citation2017), and one mixed-methods article reported mental health concerns in a cohort of trans people with low physical activity levels (Stewart et al., Citation2020). Two quantitative articles recorded sub-clinical levels of depressive symptoms in their trans sample (Jones et al., Citation2018; Krueger et al., Citation2021) and one quantitative article provided self-reported depression diagnoses (Downing & Przedworski, Citation2018). One quantitative article (Jones et al., Citation2018), one qualitative article (Jones et al., Citation2017), and one mixed methods article (Stewart et al., Citation2020) reported anxiety symptoms. However, none of these articles measured for an association between low physical activity levels and mental health concerns.

A further four quantitative articles (Krueger et al., Citation2021; Nagata et al., Citation2020a; Citation2020b; Uniacke et al., Citation2021) and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) reported mental health concerns in a sample of trans people experiencing compulsive exercise. Three quantitative articles (Nagata et al., Citation2020a; Citation2020b; Uniacke et al., Citation2021) and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) reported eating disorder symptoms (other than compulsive exercise), one qualitative reported anxiety symptoms (Uniacke et al., Citation2021), and one quantitative article reported self-injuring behaviors (Krueger et al., Citation2021). However, none of these articles measured for an association between compulsive exercise and mental health concerns.

Influences on physical activity levels

Two quantitative articles (Jones et al., Citation2018; Velez et al., Citation2016), two qualitative articles (Jones et al., Citation2017; Teti et al., Citation2020), and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) described a relationship between physical activity levels, gender congruence, and body satisfaction. Individual quantitative (Jones et al., Citation2018), qualitative (Jones et al., Citation2017), and mixed methods (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) articles reported an association between gender-affirming medical interventions and physical activity levels. Jones et al. (Citation2017) described motivation to engage in physical activity to increase gender congruence amongst a sample of trans young adults on hormone therapy. In their quantitative study, Jones et al. (Citation2018) reported that trans participants on hormone therapy engaged in significantly more physical activity than those who were not. Within those who were not on hormone therapy, self-esteem was significantly associated with physical activity levels (rs=.23, p<.001) (Jones et al., Citation2018). Within those on hormone therapy, self-esteem (rs=.29, p<.001) and body satisfaction (rs=.38, p<.001) were associated with physical activity (Jones et al., Citation2018). In their thematic analysis, Ålgars et al. (Citation2012) described reduced disordered eating and exercise behaviors after ‘gender reassignment’ in some participants. Uniacke et al (Citation2021) reported lower odds of disordered eating or exercise in trans people with higher gender congruence (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.55–0.94). Similarly, Velez et al. (Citation2016) reported a negative correlation between compulsive exercise, gender congruence (-0.16, p<.01), and body satisfaction (-0.17, p < 0.05) in a sample of trans men.

Consistent with these findings, two qualitative articles (Jones et al., Citation2017; Teti et al., Citation2020), one quantitative article (Velez et al., Citation2016), and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) reported physical activity in trans participants motivated by gender affirmation via body shape change. One qualitative (Teti et al., Citation2020), one quantitative (Velez et al., Citation2016), and one mixed methods (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) article described physical activity as a means to ‘pass’ (i.e. be accurately perceived as one’s affirmed gender). Furthermore, one qualitative (Teti et al., Citation2020) and one mixed methods article (Ålgars et al., Citation2012) described physical activity with the intention of suppressing gendered characteristics such as hips and breasts, and/or suppress menstruation. One quantitative article described physical activity avoidance in trans women due to concerns it may masculinize their bodies (Smalley et al., Citation2016). One qualitative article described the wearing of chest binders as restricting physical activity participation (Jones et al., Citation2017). This article also reported physical activity avoidance due to increased gender dysphoria during activities that made participants more aware of their breasts and/or genitals such as running or jumping (Jones et al., Citation2017).

Three quantitative articles (Muchicko et al., Citation2014; Uniacke et al., Citation2021, Velez et al., Citation2016) and three qualitative articles (Hargie et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2017; Teti et al., Citation2020) reported the impact of discrimination and/or minority stress on physical activity levels. Muchicko et al. (Citation2014) reported an association between childhood peer victimization (overt victimization, relational victimization, and pre-social receipt) and low physical activity levels in trans participants. Velez et al. (Citation2016) reported a correlation between anti-trans discrimination and compulsive exercise (.16, p<.01) (Velez et al., Citation2016). Similarly, Uniacke et al. (Citation2021) reported greater odds of disordered eating and exercise in participants with higher levels of internalized transphobia (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.04–1.91).

Three qualitative articles (Hargie et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2017; Teti et al., Citation2020) and one mixed methods article (Stewart et al., Citation2020) described their concerns about discrimination to be related to the concept of ‘passing’ (i.e. perceived by others one’s t affirmed gender), with two of the qualitative articles describing these concerns as especially salient in the context of public changing facilities (Hargie et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2017) and one qualitative article (Jones et al., Citation2017) describing reduced ability to ‘pass’ due to the increased body exposure associated with athletic clothing.

Two qualitative (Elling-Machartzki, Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2017) and two quantitative (Ceolin et al., Citation2023; Teti et al., Citation2020) articles described preferences for specific kinds of physical activity amongst trans participants. Two articles described swimming as a particularly unfavorable form of physical activity (Elling-Machartzki, Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2017). Two qualitative articles (Jones et al., Citation2017; Teti et al., Citation2020) and one quantitative (Ceolin et al., Citation2023) article reported a preference for physical activities based in trans peoples’ own homes.

Quality assessment

Nineteen articles were assessed using the Checklist for Assessing the Quality of Quantitative Studies (Kmet et al., Citation2004) with scores ranging from 0.45 to 0.95 (see ). The remaining six articles were assessed by the Checklist for Assessing the Quality of Qualitative Studies (Kmet et al., Citation2004), with scores ranging from 0.65 to 0.85 (see ).

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to examine the literature related to the physical activity behaviors of trans adults, with a focus on understanding behavior from the perspective of health. This scoping review revealed low levels of physical activity in trans people compared to both health recommendations and to cisgender people. All studies that measured compulsive exercise reported disordered attitudes and motivations toward exercise in trans people, along with disordered eating behaviors, anxiety, and self-injuring behavior in trans people with compulsive exercise. Several health risks including cardiovascular events, bone health issues, diabetes, kidney disease, and mental health concerns were reported in trans people with low physical activity levels. However, only one article measured for association, finding that cardiovascular events were directly associated with low physical activity levels.

Influences on physical activity levels and behavior appeared to be similar for trans people with low levels of physical activity and those with compulsive exercise. Both low levels of physical activity and compulsive exercise were associated with lower gender congruence and poorer body satisfaction. Furthermore, accessing gender-affirming medical interventions, such as hormone therapy and surgical interventions, was associated with increased physical activity levels in samples of low levels of physical activity and reduced compulsive exercise. Low physical activity levels and compulsive exercise were also both statistically associated with experiences of discrimination and minority stress.

Given the role of gender congruence and body satisfaction on physical activity levels in this scoping review, gender-affirming medical care (for trans people who desire it) may play a key role in promoting physical activity levels in trans people. This is consistent with a recent systematic review that reported improved gender dysphoria, body uneasiness, body satisfaction, quality of life, and self-esteem in trans people with hormone therapy (van Leerdam et al., Citation2023). Therefore, it is possible that gender-affirming medical care may indirectly reduce the health risks reported with low or compulsive exercise such as cardiovascular events, diabetes, bone health issues, eating disorders, and other mental health concerns. However, given the social, legal, and financial barriers to gender-affirming medical care, complementary strategies aimed at increasing body congruence, body satisfaction, and self-esteem need to be developed to support healthy physical activity in this population. For example, gender-affirming fitness professionals and clinicians might consider tailored training regimes with a trans person’s gender-affirming body goals in mind.

Furthermore, many trans people do not desire medical interventions as part of their gender affirmation. For these individuals, physical activity may serve as an alternative form of gender affirmation. This may partially explain the outlier finding of Smalley et al. (Citation2016), in which non-binary participants engaged in more physical activity than both binary trans people and cisgender people. This is also consistent with the findings of Jones et al. (Citation2018), who reported self-esteem as the greater predictor of physical activity participation in trans participants not on hormone therapy. Future research in this space would benefit from asking participants not only their hormone and surgical statuses, but also their desire for these interventions. In the context of non-medical affirmation, chest binding was described as a deterrent to physical activity (Jones et al., Citation2017). It is the common advice of trans community organizations that one should not engage in any physical activity in a chest binder (Medical News Today, 2022; Point of Pride, 2018; Shuttleworth, 2022; Transhub, Citation2021). However, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted on the safety of chest binding during physical activity. As such, specific research on the impact of chest binding on physiological function during physical activity is needed to determine the safety of such practices and clarify community guidance.

Experiences of minority stress and discrimination were also associated with low physical activity levels and compulsive exercise, including experiences of childhood victimization, anti-trans discrimination, and internalized transphobia. As discussed in our introduction, previous research has demonstrated high levels of anti-trans discrimination experienced by trans people in their daily lives (Grant et al., Citation2011; Shires et al., Citation2018; Strauss et al., Citation2020). However, this review extends this knowledge by reporting these concerns to be especially salient in the context of physical activity due to factors such as binary public facilities and the increased body exposure associated with activewear and changing facilities. As a result, the trans people who engaged in physical activity preferred to do so in their homes rather than in public spaces.

Exercising alone and in private spaces may help to reduce gender dysphoria and safety concerns. It also provides an opportunity for accessible and adaptable forms of physical activity participation that can be supported by a variety of digital physical activity tools (e.g. web-based applications, mobile apps, videos, telehealth). However, there are potential cautions to note given the rates of compulsive and/or disordered exercise reported in trans people (Rasmussen et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, participation in physical activity with little to no interaction with others (e.g. via videos on YouTube) is unlikely to provide the potential mental health benefits often attributed to the socialization aspect of physical activity (Lederman et al., Citation2021). Future research should look to develop mechanisms for physical activity engagement that seek to reduce the barriers associated with traditional physical activity spaces, but still facilitates social support and appropriate supervision and guidance to monitor risky behaviors.

Limitations

Scoping reviews are a useful method when limited data are available, but they also allow for the inclusion of all data irrespective of quality (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). To minimize the risk of bias, a quality assessment was conducted as part of this review. Results and conclusions were written with consideration of article quality. The inclusion criteria of this review were limited to trans people 16 years and older and articles written in English. As such, the findings do not reflect the experiences of trans children and younger adolescents, nor those from all countries and cultures. Due to ongoing policies of exclusion from competitive sports, this review focused on physical activity behaviors outside of the sporting context. However, a systematic review of trans competitive sports participation has been conducted (Jones et al., Citation2017).

Included articles utilized 12 different validated measures for physical activity levels, limiting comparison. Additionally, articles measured these physical activity levels against varied minimum recommendations. Whilst one of our aims was to determine if trans people met WHO minimum exercise recommendations, only one article directly compared to these recommendations. A further four articles could be interpreted for comparison to a different minimum recommendation provided by the authors.

There was great inconsistency as to whether trans people’s physical activity levels were compared to those of cisgender people of the same sex assigned at birth of the same gender identity. When trans women’s physical activity levels were compared to cisgender women, they were relatively similar. However, in articles where trans women were compared to cisgender men, there was a greater discrepancy. This trend was generally not observed in trans men, who had lower physical activity levels than cisgender men, but similar levels to cisgender women. This inconsistency in comparison groups raises questions about whether gender identity and gender roles are more relevant factors than one’s sex assigned at birth when comparing physical activity levels of trans people to cisgender people.

Findings regarding health risks are limited by a lack of analysis for correlations between physical activity levels and health risks, with only one article reporting a statistically significant association between low physical activity and health risks. All other health risks reported in this review are present in a sample with low physical activity or compulsive exercise but without any ability to infer a relationship. Future research should measure for potential associations and confounders between physical activity levels and health risks in trans people.

Only one-third of reviewed articles included non-binary participants, limiting the applicability of findings to this population. However, it is likely that non-binary individuals participated in these studies but were unable to authentically identify themselves due to the binary gender categories offered in these studies. Given the binary nature of many physical activity spaces reported by included articles, it is unfortunate that the potential unique experiences of non-binary people have been erased. Future research should consider providing a range of gender identity options in their data collection to fully capture the diversity of these experiences.

The term ‘passing’ is used in this paper, as this is the terminology used in the reviewed literature to describe a trans person who appears cisgender. However, the authors reject the implication that being able to ‘pass’ is to be successful and being visibly trans is to ‘fail’. Trans people should not need to appear cisgender to feel safe in physical activity spaces. We acknowledge the importance of ‘passing’ to many trans people whilst simultaneously acknowledging that not all trans people desire to ‘pass’. Given the limited inclusion of non-binary people (who are unable to ‘pass’ as non-binary in a world of binary expectations) in reviewed articles, the importance of ‘passing’ in physical activity behaviors may be overstated.

The conclusions drawn in this review reflect the literature up to September 2023. However, the global discourse surrounding trans rights, community inclusion, and physical activity participation is ongoing.

Conclusions

Trans people engage in low levels of physical activity or in compulsive exercise, which may contribute to increased health risks in this population. Both low physical activity and compulsive exercise are influenced by gender congruence, body satisfaction, minority stress, and experiences of discrimination. The findings of this review suggest physical activity should be considered in gender-affirming models of care to support both increase gender congruence and to prevent compulsive behaviors. They also demonstrate a need for safe, affirming, and supportive physical activity spaces for trans people without fear of discrimination. Targeted physical activity interventions aimed at increasing gender congruence may harness the unique motivations of trans people and increase physical activity participation. Improved identification and screening for early warning signs of compulsive exercise are also necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge that the language and terminology of gender identity are diverse and constantly evolving. In consultation with members of the trans and gender diverse community and the Telethon Kids Institute research team, this article will strive to make use of the most current and inclusive terms and abbreviations available. No exclusion, offense, or distress is intended by the use of language that may not be appropriate to all individuals, in particular those of different cultures.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no conflicts of interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ålgars, M., Alanko, K., Santtila, P., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2012). Disordered eating and gender identity disorder: A qualitative study. Eating Disorders, 20(4), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.668482

- Alzahrani, T., Nguyen, T., Ryan, A., Dwairy, A., McCaffrey, J., Yunus, R., Forgione, J., Krepp, J., Nagy, C., Mazhari, R., & Reiner, J. (2019). Cardiovascular disease risk factors and myocardial infarction in the transgender population. Circulation. Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 12(4), e005597. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.119.005597

- Baecke, J. A. H., Burema, J., & Frijters, J. E. R. (1982). A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36(5), 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301241

- Ceolin, C., Scala, A., Dall’Agnol, M., Ziliotto, C., Delbarba, A., Facondo, P., Citron, A., Vescovi, B., Pasqualini, S., Giannini, S., Camozzi, V., Cappelli, C., Bertocco, A., De Rui, M., Coin, A., Sergi, G., Ferlin, A., & Garolla, A. (2023). Bone health and body composition in transgender adults before gender-affirming hormonal therapy: data from the COMET study. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-023-02156-7 37450195

- Coelho, J. S., Suen, J., Clark, B. A., Marshall, S. K., Geller, J., & Lam, P.-Y. (2019). Eating disorder diagnoses and symptom presentation in transgender youth: A scoping review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(11), 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1097-x

- Cunningham, T. J., Xu, F., & Town, M. (2018). Prevalence of five health-related behaviors for chronic disease prevention among sexual and gender minority adults—25 U.S. states and Guam, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(32), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a4

- DiPietro, L., Caspersen, C. J., Ostfeld, A. M., & Nadel, E. R. (1993). A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 25(5), 628–642. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199305000-00016

- Downing, J. M., & Przedworski, J. M. (2018). Health of transgender adults in the U.S., 2014–2016. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(3), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.045

- Elling-Machartzki, A. (2017). Extraordinary body-self narratives: Sport and physical activity in the lives of transgender people. Leisure Studies, 36(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1128474

- Godin, G., & Shephard, R. J. (1985). Leisure time exercise questionnaire. PsycTESTS Dataset, https://doi.org/10.1037/t31334-000

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf

- Hagströmer, M., Oja, P., & Sjöström, M. (2006). The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutrition, 9(6), 755–762. https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2005898 16925881

- Hargie, O. D. W., Mitchell, D. H., & Somerville, I. J. A. (2017). ‘People have a knack of making you feel excluded if they catch on to your difference’: Transgender experiences of exclusion in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215583283

- Jones, B. A., Arcelus, J., Bouman, W. P., & Haycraft, E. (2017). Sport and transgender people: A systematic review of the literature elating to sport participation and competitive sport policies. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 47(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0621-y

- Jones, B. A., Arcelus, J., Bouman, W. P., & Haycraft, E. (2017). Barriers and facilitators of physical activity and sport participation among young transgender adults who are medically transitioning. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1293581

- Jones, B. A., Haycraft, E., Bouman, W. P., & Arcelus, J. (2018). The levels and predictors of physical activity engagement within the treatment-seeking transgender population: A matched control study. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 15(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2017-0298

- Kmet, L., Lee, R. C., Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. https://www.ihe.ca/advanced-search/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields

- Krueger, E. A., Barrington-Trimis, J. L., Unger, J. B., & Leventhal, A. M. (2021). Sexual and gender minority young adult coping disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(5), 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.021

- Lapauw, B., Taes, Y., Simoens, S., Van Caenegem, E., Weyers, S., Goemaere, S., Toye, K., Kaufman, J.-M., & T’Sjoen, G. G. (2008). Body composition, volumetric and areal bone parameters in male-to-female transsexual persons. Bone, 43(6), 1016–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2008.09.001

- Lederman, O., Furzer, B., Wright, K., McKeon, G., Rosenbaum, S., & Stanton, R. (2021). Mental health considerations for exercise practitioners delivering telehealth services. Journal of Clinical Exercise Physiology, 10(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.31189/2165-7629-10.1.20

- Lichtenstein, M. B., Hinze, C. J., Emborg, B., Thomsen, F., & Hemmingsen, S. D. (2017). Compulsive exercise: Links, risks and challenges faced. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s113093

- Medical News Today. (2022, June 29). Chest or breast binding: Tips, side effects, safety, and more. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/breast-binding

- Muchicko, M. M., Lepp, A., & Barkley, J. E. (2014). Peer victimization, social support and leisure-time physical activity in transgender and cisgender individuals. Leisure/Loisir, 38(3-4), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2015.1048088

- Nagata, J. M., Compte, E. J., Cattle, C. J., Flentje, A., Capriotti, M. R., Lubensky, M. E., Murray, S. B., Obedin-Maliver, J., & Lunn, M. R. (2020a). Community norms for the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) among gender-expansive populations. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00352-x

- Nagata, J. M., Murray, S. B., Compte, E. J., Pak, E. H., Schauer, R., Flentje, A., Capriotti, M. R., Lubensky, M. E., Lunn, M. R., & Obedin-Maliver, J. (2020b). Community norms for the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) among transgender men and women. Eating Behaviors, 37, 101381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101381

- Oliveira, J., Frontini, R., Jacinto, M., & Antunes, R. (2022). Barriers and motives for physical activity and sports practice among trans people: A systematic review. Sustainability, 14(9), 5295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095295

- Pérez-Samaniego, V., Fuentes-Miguel, J., Pereira-García, S., López-Cañada, E., & Devís-Devís, J. (2019). Experiences of trans persons in physical activity and sport: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Sport Management Review, 22(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.08.002

- Point of Pride. (2018, January 15). Binding 101: Tips to bind your chest safely. https://www.pointofpride.org/blog/binding-101-tips-to-bind-your-chest-safely

- Public Broadcasting Service. (2015, August 12). A map of gender-diverse cultures. Public Broadcasting Service. https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/content/two-spirits_map-html/

- Rasmussen, S. M., Dalgaard, M. K., Roloff, M., Pinholt, M., Skrubbeltrang, C., Clausen, L., & Kjaersdam Telléus, G. (2023). Eating disorder symptomatology among transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00806-y

- Reisner, S. L., Poteat, T., Keatley, J., Cabral, M., Mothopeng, T., Dunham, E., Holland, C. E., Max, R., & Baral, S. D. (2016). Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. Lancet (London, England), 388(10042), 412–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00684-x

- Sedlak, C. A., Roller, C. G., van Dulmen, M., Alharbi, H. A., Sanata, J. D., Leifson, M. A., Veney, A. J., Alhawatmeh, H., & Doheny, M. O. B. (2017). Transgender individuals and osteoporosis prevention. Orthopedic Nursing, 36(4), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1097/nor.0000000000000364

- Shires, D. A., Stroumsa, D., Jaffee, K. D., & Woodford, M. R. (2018). Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. Annals of Family Medicine, 16(6), 555–558. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2298

- Shuttleworth, H. (2022, October 3). Chest binding and physiotherapy. Australian Physiotherapy Association. https://australian.physio/inmotion/chest-binding-and-physiotherapy

- Smalley, K. B., Warren, J. C., & Barefoot, K. N. (2016). Differences in health risk behaviors across understudied LGBT subgroups. Health Psychology, 35(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000231

- Stewart, L., Oates, J., & O’Halloran, P. (2020). “My voice is my identity”: The role of voice for trans women’s participation in sport. Journal of Voice, 34(1), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.05.015

- Strauss, P., Cook, A., Winter, S., Watson, V., Wright Toussaint, D., & Lin, A. (2020). Associations between negative life experiences and the mental health of trans and gender diverse young people in Australia: Findings from trans pathways. Psychological Medicine, 50(5), 808–817. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719000643

- Streed, C. G., Beach, L. B., Caceres, B. A., Dowshen, N. L., Moreau, K. L., Mukherjee, M., Poteat, T., Radix, A., Reisner, S. L., & Singh, V.; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Hypertension; and Stroke Council. (2021). Assessing and addressing cardiovascular health in people who are transgender and gender diverse: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 144(6), e136–e148. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001003

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

- Teti, M., Bauerband, L. A., Rolbiecki, A., & Young, C. (2020). Physical activity and body image: Intertwined health priorities identified by transmasculine young people in a non-metropolitan area. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1719950

- Topolski, T. D., LoGerfo, J., Patrick, D. L., Williams, B., Walwick, J., & Patrick, M. B. (2006). The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(4). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16978493/

- Transhub. (2021). Binding. TransHub. https://www.transhub.org.au/binding

- Uniacke, B., Glasofer, D., Devlin, M., Bockting, W., & Attia, E. (2021). Predictors of eating-related psychopathology in transgender and gender nonbinary individuals. Eating Behaviors, 42, 101527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101527

- Van Caenegem, E., Taes, Y., Wierckx, K., Vandewalle, S., Toye, K., Kaufman, J.-M., Schreiner, T., Haraldsen, I., & T’Sjoen, G. (2013a). Low bone mass is prevalent in male-to-female transsexual persons before the start of cross-sex hormonal therapy and gonadectomy. Bone, 54(1), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.039

- Van Caenegem, E., Verhaeghe, E., Taes, Y., Wierckx, K., Toye, K., Goemaere, S., Zmierczak, H. G., Hoebeke, P., Monstrey, S., & T’Sjoen, G. (2013b). Long-term evaluation of donor-site morbidity after radial forearm flap phalloplasty for transsexual men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(6), 1644–1651. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12121

- van Leerdam, T. R., Zajac, J. D., & Cheung, A. S. (2023). The effect of gender-affirming hormones on gender dysphoria, quality of life, and psychological functioning in transgender individuals: A systematic review. Transgender Health, 8(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0094

- Velez, B. L., Breslow, A. S., Brewster, M. E., Cox, R., & Foster, A. B. (2016). Building a pantheoretical model of dehumanization with transgender men: Integrating objectification and minority stress theories. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000136

- Vilas, M., Rubalcava, G., Becerra, A., & Para, M. (2014). Nutritional status and obesity prevalence in people with gender dysphoria. AIMS Public Health, 1(3), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2014.3.137

- Wilson, O. W., Jones, B. A., & Bopp, M. (2023). College student aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity: Disparities between cis-gender and transgender students in the United States. Journal of American College Health, 71(2), 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1895808

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128