Abstract

Introduction

Transgender people face serious health disparities associated with underlying social determinants, such as unmet healthcare needs and negative experiences with healthcare providers. Healthcare accessibility dimensions include availability, approachability, acceptability, affordability, and appropriateness. This study aimed to identify the perceived barriers and facilitators that transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand experience within these dimensions, as few studies have explored multiple dimensions of healthcare access for transgender people using a large national sample.

Method

Responses to an open-text question in the Counting Ourselves survey (n = 236) were analyzed utilizing qualitative content analysis. A primarily deductive approach was used to identify categories and frame these within a comprehensive healthcare accessibility model.

Results

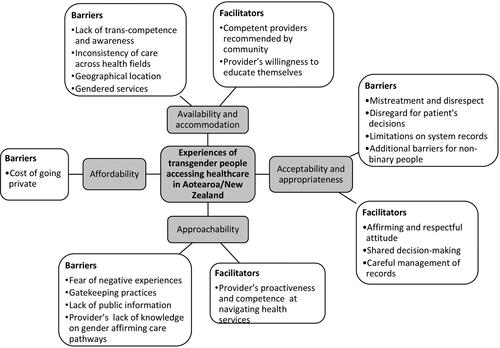

In line with international research, some prominent barriers were the lack of trans-competent providers (availability/accommodation), experiences of mistreatment (acceptability/appropriateness), and gatekeeping practices (approachability). Facilitators included, among others, providers’ willingness to educate themselves (availability/accommodation), an affirming attitude (acceptability/appropriateness), and competence in navigating services (approachability).

Conclusions

Transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand see their healthcare experiences affected by barriers across all dimensions of healthcare access. This highlights a great degree of mismatch between their needs and the healthcare system’s characteristics, thereby breaching their right to healthcare of adequate standards. We recommend that all healthcare practitioners and administrative staff receive training on transgender health, that there is increased accessibility to information on gender-affirming care services, and that collaborative referral procedures that respect patient decisions are implemented.

Introduction

Determinants of health disparities and healthcare access

Transgender peopleFootnote1 experience multiple physical and mental health disparities (e.g. Christian et al., Citation2018; Giblon & Bauer, Citation2017), with a greater body of research on mental health (e.g. Brown & Jones, Citation2016; Fenaughty et al., Citation2023; Hyde et al., Citation2014; Tan, Ellis, Schmidt, Byrne, & Veale, Citation2020). These disparities exemplify health inequities, that is, systematic differences in health outcomes not explained by biological mechanisms, but rather by social and environmental factors (Whitehead & Dahlgren, Citation2007), often referred to as social determinants of health (World Health Organization, n.d.). Among these, healthcare access plays an important role. From a human rights perspective, having access to timely, effective, and appropriate healthcare is one of the key components necessary to ensure the universal right to health, defined as the right to achieve one’s full potential in terms of physical and mental well-being (Whitehead & Dahlgren, Citation2007).

Levesque, Harris, and Russell (Citation2013) conducted an extensive literature review of healthcare access conceptualizations and integrated these. They outlined five dimensions of accessibility of healthcare services: approachability (transparency of services and outreach); acceptability (cultural and demographic characteristics; related to ensuring socially vulnerable groups’ needs are met); availability and accommodation (all service’s resources in terms of facility characteristics, provider characteristics, the urban context and modality of services), affordability (financial costs and time resources); and appropriateness (technical and interpersonal quality of service). These dimensions are separated conceptually but interconnected in practice. Levesque and colleagues added several patient-side factors that interact with each of the supply-side dimensions, such as patients’ ability to perceive and trust the healthcare system (which interacts with providers’ approachability) and their ability to engage in healthcare (which interacts with providers’ appropriateness).

Healthcare accessibility barriers and facilitators for transgender people

Gender-affirming care is healthcare that supports people to “identify and facilitate gender healthcare goals”, which may include gender identity exploration, and support for social, or medical transition (Oliphant et al., Citation2018, p. 3). When discussing healthcare accessibility for transgender people, we will use the term general healthcare to refer to all healthcare that is not primarily aimed at supporting these gender-affirming needs. In some instances, issues will be relevant to both types of care, so the broader term healthcare or care will be used.

Availability and accommodation

The dimension of availability and accommodation includes the physical existence of facilities, their geographical distribution, and the existence of qualified providers. Several United States and Australian studies have found that transgender patients perceive a generalized lack of provider knowledge about transgender people, as well as a fundamental lack of understanding of gender identity (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017; Pampati et al., Citation2021; Riggs, Coleman, & Due, Citation2014; Safer et al., Citation2016). In Sweden, patients discussed the burden of educating their providers about transgender issues (Lindroth, Citation2016). Gendered services can worsen these barriers; for instance, sexual health clinics in the United States were visually exclusive to cisgender women, alienating transgender people (Harb, Pass, De Soriano, Zwick, & Gilbert, Citation2019). Similar experiences were reported by those seeking endometriosis care in various countries (Canada, Norway, and Australia, among others), leading to feelings of exclusion (Eder & Roomaney, Citation2023).

Moreover, a perceived lack of provider training in gender-affirming care has been a reported concern in Australia, the United States, and Russia (Bartholomaeus, Riggs, & Sansfaçon, Citation2021, Eisenberg, McMorris, Rider, Gower, & Coleman, Citation2020, Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023; Lerner & Robles, Citation2017). This deficiency can result in varying care quality, a common theme reported by parent-child dyads in Australia (Bartholomaeus et al., Citation2021). Provider competence is crucial, as it significantly influences transgender individuals’ decision to utilize healthcare (Lerner, Lerner, Martin, & Silva, Citation2022).

Healthcare providers’ reports appear to be consistent with transgender patients’ concerns. Studies from Canada, Europe, India, Russia, and the United States have found that a great proportion of healthcare practitioners report lacking experience or training in working with transgender patients or providing gender-affirming care (Burgwal et al., Citation2021; Christopherson et al., Citation2021; Jain, Karthick, Keni, & Avudaiappan, Citation2022; Kawsar and Linander, Citation2022; Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023; Korpaisarn & Safer, Citation2018; Montes-Galdeano et al., Citation2021). Geographical factors compound this issue, with the scarcity of trans-competent providers making location, transportation, travel time, and costs significant barriers to accessibility (Pampati et al., Citation2021; Ross et al., Citation2023; Safer et al., Citation2016; Tami, Ferguson, Bauer, & Scheim, Citation2022).

Research from Australia has also reported on the more unusual instances where providers have sufficient knowledge of transgender health and the social issues the transgender community faces, which act as facilitators of care (Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020; Riggs et al., Citation2014). The U.S. Trans Mental Health Survey participants perceived having a competent and knowledgeable provider as uncommon and fortunate (Snow, Cerel, & Frey, Citation2022).

Acceptability and appropriateness

Experiences of discrimination and harassment in healthcare settings are also frequent barriers reported by research (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017). As noted in other studies (Cu, Meister, Lefebvre, & Ridde, Citation2021) these barriers relate to both acceptability and appropriateness, as they are linked to the cultural characteristics of the provider, and the interpersonal quality of the service (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Due to this, these dimensions have been grouped for this article.

Being denied general healthcare or being discriminated against due to transgender identity, have been some of the most recurrent barriers found across the literature (Eder & Roomaney, Citation2023; Lerner & Robles, Citation2017; Newsom, Riddle, Carter, & Hille, Citation2021). The 2015 US National Transgender Survey found that 29% of participants had been verbally harassed in healthcare settings (James et al., Citation2016). Australian and United States research has revealed that harassment and derogatory behavior can include inappropriate use of language, offensive questions (Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020; Riggs et al., Citation2014), non-verbal signs of uncomfortableness (Pampati et al., Citation2021), and misgendering (Eisenberg et al., Citation2020; Vupputuri et al., Citation2021), which are usually rooted in cisnormative assumptions. Furthermore, research participants in Sweden, Australia, and the United States have shared experiences of providers questioning the validity of their gender identity or the existence of transgender people altogether (Grant, Russell, Dane, & Dunn, Citation2023; Lindroth, Citation2016), as well as imposing medical decisions on them (Alpert et al., Citation2021; Grant et al., Citation2023).

United States-based research has revealed that mistreatment risk is higher in emergency rooms and hospitals (Allison et al., Citation2021; Grant et al., Citation2011). In gynecological services, transgender men and non-binary participants AFAB (assigned female at birth) reported mistreatment due to their gender presentation conflicting with a service targeted toward cisgender women (Harb et al., Citation2019).

Facilitators of care include a respectful, caring, understanding, and information-sharing attitude from the provider. Positive experiences reported in the United Kingdom, Australian, and the United States involve open communication, active listening, collaboration toward shared goals, and the acknowledgment that patients are experts on themselves (Grant et al., Citation2023; Hall & DeLaney, Citation2021; Pampati et al., Citation2021; Riggs et al., Citation2014; Sperber, Landers, & Lawrence, Citation2005; Wright et al., Citation2021). Additional validation facilitators include the appropriate record and consistent use of correct pronouns and names (Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020; Pampati et al., Citation2021).

Approachability

The dimension of approachability refers to the health system’s ability to make its services known and reachable, which relates to the patient’s awareness of existing healthcare services and how to access them (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Transgender people face distinct challenges in approachability, including a lack of information through official channels, referral processes demanding proof of gender identity, and the negative impact of previous experiences on healthcare-seeking behavior.

Research in the United States and the United Kingdom emphasizes the scarcity of information about transgender-competent providers and gender-affirming care services through official healthcare channels. As a result, transgender individuals often heavily rely on community networks to find these services (Sperber et al., Citation2005; Vupputuri et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2021). Compounding the issue, providers may also lack awareness of available gender-affirming care services and referral processes (Eisenberg et al., Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2021).

The referral process for gender-affirming care has been described as creating obstacles and relying excessively on provider judgment (Pampati et al., Citation2021). Participants from several studies in Australia, Europe, and the United Kingdom reported feeling they had to “convince” providers of their transgender identity, based on a binary and stable understanding of gender, which pressured them to strategically portray their gender in this way (Grant et al., Citation2023; Linander, Alm, Goicolea, & Harryson, Citation2017; Lindroth, Citation2016; Ross et al., Citation2023; Wright et al., Citation2021). This places providers as arbiters of healthcare decisions, side-lining transgender people’s knowledge and community insights on gender-affirming care (Grant et al., Citation2023). Gatekeeping by providers may also lead to self-medication (Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023).

Fear of negative experiences significantly impacts approachability through patients’ healthcare-seeking behaviors, impacting the demand side of this dimension (the patient’s ability to trust; Levesque et al., Citation2013). Negative experiences can lead to transgender people deciding to avoid them by not seeking healthcare altogether (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017). Reported reasons for transgender people avoiding or postponing seeking care in the United States, Pakistan, and Canada have been fear of mistreatment, non-acceptance, and mistrust of their provider (James et al., Citation2016; Manzoor, Zartasha, Tariq, & Shahzad, Citation2022; Tami et al., Citation2022). This fear may also lead to masking gender identity from providers (Eder & Roomaney, Citation2023; Sperber et al., Citation2005), particularly noted by non-binary research participants in Thailand (Moallef et al., Citation2022).

Facilitators for approachability found in United States literature include continuity of care (Sperber et al., Citation2005), and the concept of integrated care, which is gender-affirming care that does not rely on external referrals and is coordinated and connected (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017). More formalized channels of information-sharing between providers should reduce the burden on transgender people to navigate information gaps (Grant et al., Citation2023).

Affordability

Affordability refers to the financial and time costs of healthcare services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). In the United States, Lerner and Robles (Citation2017) identified affordability as a prominent barrier, encompassing general and gender-affirming care costs. Discriminatory policy language and practices cause difficulties in accessing insurance (Gonzales & Henning-Smith, Citation2017; Kirkland, Talesh, & Perone, Citation2021; Sperber et al., Citation2005), resulting in a higher likelihood of being uninsured (Downing, Lawley, & McDowell, Citation2022). Concerning gender-affirming care, 27.7% of transgender participants in a European survey cited costs as a barrier (Ross et al., Citation2023), while transgender people in Russia reported cost was one of the main barriers to accessing gender-affirming hormonal therapy (Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023).

Aotearoa/New Zealand

Research on the healthcare experiences of transgender individuals in Aotearoa/New Zealand is still emerging. The Counting Ourselves survey uncovered various availability and accommodation barriers, including 33% of participants reporting their gender-affirming care provider had limited knowledge about transgender people and 47% of participants having taught a provider (Veale et al., Citation2019). In 2021, only 32% of District Health Boards Footnote2 provided staff training to work with transgender people (Oliphant, Citation2021). Withey-Rila, Morgaine, and Treharne (Citation2023) identified negative experiences in primary care as the norm due to a lack of provider knowledge, sometimes resulting in refusals to provide care. Fraser (Citation2020) found that gender-affirming care availability was mainly dependent on location, consistent with Counting Ourselves participants traveling large distances to access trans-competent providers (Tan, Carroll, Treharne, Byrne, & Veale, Citation2022). Conversely, 42% of Counting Ourselves participants noted a provider was willing to educate themselves on transgender health (Veale et al., Citation2019), while Withey-Rila et al. (Citation2023) found that providers possessing basic knowledge about transgender concepts and gender-affirming care were positive experiences, but providers advocating for wider changes within the healthcare system was the optimal form of support.

Regarding acceptability and appropriateness, 36% of Counting Ourselves participants had been asked unnecessary questions by providers, 26% had been knowingly misgendered, and 17% reported insulting language (Veale et al., Citation2019). Withey-Rila et al. (Citation2023) found that transgender people attempted to reduce these experiences by carefully preparing themselves or choosing when to disclose their gender identity. Furthermore, Counting Ourselves participants were less likely to rate their GPs highly for shared decision-making compared to the general population (79% versus 89%; Veale et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, providers treating participants like any other patient (55%) and consistently using correct names and pronouns (46% and 41%, respectively) were reported facilitators (Veale et al., Citation2019). Withey-Rila et al. (Citation2023) noted that providers being supportive and professional was the most basic level of a gradient of positive healthcare experiences.

Prominent approachability barriers for gender-affirming care are a lack of information on where to go and fear of accessing it (40% and 26%, respectively; Veale et al., Citation2019). Only 16% of District Health Boards provide publicly available information on gender-affirming services (Oliphant, Citation2021). Withey-Rila et al. (Citation2023) described participants conducting extensive personal research to find adequate providers, while providers who had knowledge about service pathways and who provided advocacy were greatly appreciated. Mental health assessments to access gender-affirming care have been described as pressuring transgender people to conform to a dominant narrative, with inconsistency of procedures and referral pathways across the country (Fraser, Brady, & Wilson, Citation2021). The provision of gender-affirming hormones through the primary care system has been suggested as a way to reduce gatekeeping barriers (Ker et al., Citation2021; Ker, Fraser, Lyons, Stephenson, & Fleming, Citation2020; Veale et al., Citation2023).

Counting Ourselves participants shared that unsupportive experiences caused a feeling of distrust toward providers (Tan et al., Citation2022), with 36% of Counting Ourselves participants avoiding seeking care due to fear of mistreatment (Veale et al., Citation2019), while others decided to hide their gender identity to avoid these experiences (Tan et al., Citation2022).

Affordability barriers were also substantial, with 62% of Counting Ourselves participants citing costs and 25% transportation as reasons for not visiting their GP, which was higher than the general population (Veale et al., Citation2019). One of the most frequent reasons for not accessing gender-affirming care was not being able to afford it (e.g. 28% for hormone treatment; 69% for chest reconstruction; Veale et al., Citation2019).

Aim

It is vital to understand the healthcare access barriers and facilitators that transgender people encounter, as these play a crucial role as determinants of transgender people’s health outcomes. Very few international qualitative studies have used a large national sample to explore multiple dimensions of healthcare access for transgender people. In addition, studies utilizing Levesque et al. (Citation2013) healthcare access model to explore transgender people’s healthcare experiences are still scarce, despite this model being widely used elsewhere (Cu et al., Citation2021). The present study uses qualitative data from the Counting Ourselves survey (Veale et al., Citation2019), and explores transgender people’s experiences accessing different fields of healthcare (both general and gender-affirming care), using a large national sample. The aim is to identify the perceived facilitators and barriers experienced within the different dimensions of healthcare access, as conceptualized by Levesque et al. (Citation2013).

Method

This project involved analysis of data from the Counting Ourselves Survey (Veale et al., Citation2019). This was a community-based survey conducted from June to September of 2018, covering the health and well-being of transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. The survey was administered mainly online and used a mixed-question format, including multiple-choice, rating-scale, and open-ended questions. The topics covered included physical health, mental health, social well-being, and community support.

This study qualitatively analyzed responses to an open-text question placed at the end of the survey section that asked participants about their provider’s knowledge and competence when accessing healthcare in Aotearoa/New Zealand. The question invited participants to expand on the topic or share anything they considered relevant, being worded as follows: “Is there anything else you want to share about the level of support or respect you have received, as a trans or non-binary person accessing healthcare?”.

Procedure

The survey was approved by the Aotearoa/New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (18/NTB/66/AM01). The research team recruited 10 transgender community advisors who gave feedback and contributed to the survey design, along with other researchers, community organizations, healthcare professionals, and government agencies. The sampling strategy involved a combination of convenience and purposive sampling. Recruitment was conducted through social media sites, queer and transgender community organizations, word of mouth, and health professionals, with a special focus on recruiting typically harder-to-reach populations, such as older people and those living in rural areas (Veale et al., Citation2019). The vast majority of participants answered the online format of the survey (99%). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were: (1) identifying as transgender, (2) being 14 years or above, and (3) living in Aotearoa/New Zealand (currently). There were 1178 valid responses to the survey. The number of participants who completed the provider knowledge and competence section of the survey was 984 (84% of the total sample). Out of these, 241 participants responded to the open-text question placed at the end of it. Five of these responses were “no”, leaving 236 valid responses. This was 24% of participants who completed the section and 20% of all participants who took the survey.

To know if the participants who answered the question differed from the ones who did not (in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity), chi-square goodness of fit (χ2) tests were performed (see for results and demographic details). Participants aged between 18 and 24 were less likely to answer the question, while participants aged over 55 were more likely to answer the question. Transgender women were more likely to answer the question, whereas non-binary participants AFAB were less likely to answer the question.

Table 1. Demographic details of participants who answered the open-text question about respect and support received when accessing healthcare.

To explore response bias further, tests were conducted to analyze whether those participants who answered the question were more/less likely to have indicated their doctors had been supportive or knowledgeable. This was based on their answers to a multiple-choice question that was placed in the same section as the open-text question. The question presented participants with a list of positive experiences with doctors, from which they could select all applicable options. The question was answered by 743 participants. Participants who answered the open-text question were more likely to have reported their doctors were supportive of their gender-affirming needs and that they treated them as any other patient when attending to general needs (see ). There were no differences regarding having a doctor who was knowledgeable in gender-affirming care.

Table 2. Comparison of participants who answered and did not answer the open-text question based on whether their doctors had been supportive or knowledgeable.

Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to examine the content of participants’ responses. This strategy combines quantitative and qualitative methods, hence we systematically identified categories across responses, counted their frequency, and interpreted them (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The analysis was primarily deductive or directive (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008) as it was driven by an interest to categorize responses into barriers and facilitators within an existing healthcare accessibility model. Nevertheless, an inductive or conventional approach was utilized in the initial coding of categories, as these were derived from the responses of participants before being classified into an existing framework.

Reponses were initially read several times and then coded by the lead researcher. Initial coding sought to generate as many categories as possible, to reflect the diversity of experiences. Later, these were grouped under wider categories, to reduce their number. These were then cross-checked by the coauthor and a contributing researcher. Disagreements in categories were discussed until a consensus was reached.

The second stage of analysis was informed by Levesque and colleagues’ model (2013). The identified categories were classified as either barriers or facilitators within one of the five healthcare accessibility dimensions in Levesque and colleagues’ framework (namely, availability/accommodation, acceptability/appropriateness, approachability, and affordability). The dimensions of acceptability and appropriateness were merged due to harassment and discrimination experiences being relevant to both of these healthcare accessibility dimensions. In the final stage of compilation and writing, the identified categories were made sense of by providing summaries, descriptions, participant quotes, quantitative information, and explanations (Bengtsson, Citation2016; Mayring, Citation2014).

We chose to employ an established model for organizing categories due to its comprehensive framework, which systematically considers various dimensions of healthcare accessibility in a cohesive manner. This model, successfully utilized in previous studies (Cu et al., Citation2021), thoroughly integrates existing literature on healthcare access, and has been underutilized with transgender people. Its application allowed us to discern specific areas of accessibility where transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand experience barriers and facilitators.

Results

Content analysis of participants’ responses resulted in 19 healthcare access barrier and facilitator categories. presents the 19 categories organized into each healthcare accessibility dimension proposed by Levesque et al. (Citation2013). Some dimensions, such as acceptability/appropriateness, presented a greater variety of categories, than others, like affordability. Overall, participants reported a greater variety of barriers than facilitators.

Figure 1. Category map of barriers and facilitators of healthcare access for transgender people in aotearoa/New Zealand.

Availability and accommodation

Barriers

Participants discussed a widespread lack of competence to work with transgender people from providers and healthcare staff. This was the most recurrent category among responses (n = 130; 55%). For example, a participant stated, “There appears to be a lack of basic trans knowledge taught at base level training”. The lack of trans-competence was associated with two interconnected and overlapping areas. Firstly, a lack of general awareness and knowledge about gender diversity, which related to participants feeling that there was a lack of space for them in the system, “mostly its just a general lack of awareness, that breeds a sense that there isn’t space to talk about our needs, leading to apprehension”. The second area was a lack of competence in gender-affirming care. A participant shared, “The GP I have been seeing … knows very little about trans health care and said she did not feel comfortable writing me a script for T [testosterone]”. Some participants complained about having to educate providers, “at this stage it’s just like, expected that I need to be the expert in my own care?”. The scarce availability of suitable providers results in participants’ healthcare experiences being very inconsistent, and positive experiences being rare, “my biggest problem is that I know there is only one trans friendly GP at my practice”, “I am very very lucky to have such a wonderful Gp … I know this is unusual”.

A further category was the inconsistency or differing quality of care participants received across different healthcare settings (n = 23; 10%). Participants associated better experiences with familiar providers they saw routinely, such as GPs. On the other hand, negative experiences were associated with unfamiliar settings, such as emergency services. Participants commented, “I am very fearful about seeing unknown healthcare providers - e.g. after hours doctor, emergency services, hospital, etc. because of the bad experiences I have had”; “Doctors in ER have been the worst … ER doctors do not know enough”.

Geographical location was also mentioned as a barrier, including traveling to a different area to see a trans-friendly provider or a gender-affirming care specialist (n = 6; 3%). A participant shared, “For the first 12 months after moving to [city] I continued to visit my go [gp] in [previous city of residence] for checkups and hrt [hormone therapy] scripts”.

The lack of trans-competence, and subsequent reduced inclusivity, seemed to be intensified in gendered services (e.g. gynecology). This was a barrier reported by a small number of participants (n = 6; 3%). One non-binary participant shared:

I had to go to the hospital (maternity) … First up the receptionist made a massive loud spectacle about but your a man! … You can’t access this unless you’re a woman. I had to say ‘Yes I am a woman’ or she wouldn’t let me got [sic] to my appt.

Facilitators

Participants also shared facilitators within the dimension of availability and accommodation. Firstly, the existence of some providers who were reasonably knowledgeable about transgender people, which ranged from “fairly knowledgeable” to knowing “almost everything about trans care” (n = 40; 17%). This was perceived to be a result of either specialization, self-education, or previous experience with transgender patients. Participants usually reached these providers through the recommendations of transgender networks, “current GP treats many trans ppl which is why I decided to see her; most knowledgeable, friendly, respectful and trans-competent doctor I’ve seen”; “I … moved to a better one [GP] based on recommendations from other trans people - that is why she is so well educated and respectful”.

The second facilitator, which took place when providers were not sufficiently knowledgeable, was their willingness to educate themselves (n = 32; 14%). Participants appreciated providers who were honest about their insufficient knowledge and who sought further education. Some participants accepted the provider learning from them, while others preferred the provider seeking knowledge on their own, “my GP admits she isn’t an expert on trans healthcare … but she reaches out for help when necessary and has been willing to trust me”, “[my GP] goes to every possible workshop to get more educated of gender diversity”.

Acceptability and appropriateness

Barriers

Participants shared experiences of mistreatment and disrespect due to transgender identity, including a wide range of offensive behaviors. This was a frequently reported barrier among participants (n = 77; 33%). For example, a participant shared how a counselor verbally offended them, “[the counselor] told me … ‘you just need to find your balls”. Another participant shared their experience of a provider asking them invasive questions, “I needed a repeat on my prescription for anti-depressants and wound up being stuck in the GP’s office for over an hour explaining how transgender people can have sex”. Mistreating attitudes were also manifested in non-verbal language, with a participant sharing an experience of being examined by an obstetrician, “She looked me up and down literally with her mouth open looking so disgusted by me”. Another participant shared, “I often find that health professionals are quite anxious & jumpy”.

An additional form in which disrespect manifested was misgendering. Participants noted, “mostly people just shrug off when I say I am not female, continue to use my birth name and assigned gender”, “my referring end [endocrinologist] from the sexual health clinic continues to misgender me in letters to my GP even though my gender marker has been changed”.

A second major barrier within this dimension was providers’ disregard for the patient’s opinions and decisions, as well as disaffirming attitudes (n = 27; 11%). Some participants discussed how their provider did not consider their preferences and imposed medical decisions on them. For example, a participant shared, “I was unhappy with one of my meds because I did not like the side effects … He [psychiatrist] went and upped the dose about 3 times”. Many of these experiences related to the provider imposing their beliefs about gender and questioning the participants’ gender identity, “[provider] literally said to my face ‘you’re still a woman, even if you are trans’”, “the staff (GP, dietician) trivialized my trans identity”.

An additional barrier related to appropriateness was the systems’ limitations in recording participants’ gender or name (n = 21; 9%). Participants reported several inconsistencies across providers, or across time, which were due records systems’ limitations and/or staff’s decisions. One participant commented, “The records system has some issues that bring up old names on forms from time to time”. Another participant shared:

At one time I … had not yet legally changed my name but had a preferred name … Some administrators attempted to record this by changing my first name … then the next administrator would comment that “this can’t be right” and change it back again.

Facilitators

A facilitator that was highly valued, especially when providers were not trained in transgender issues, was an affirming and respectful attitude. This was reported by many participants (n = 98; 42%). Facilitators included navigating conversations in a safe, supportive, and accepting manner, avoiding unnecessary questions, and treating patients with dignity. For example, participants noted, “My GP is not thoroughly educated in trans people but she has a lot of respect and knows how to talk safely and cares”; “my … councillor has made me feel comfortable and affirmed in my gender”. A participant also valued their provider’s effort to make them feel comfortable during certain procedures, “[my GP] is sympathetic when telling me to do something that might make me uncomfortable (i.e. a pelvic ultrasound)”.

Using the patient’s correct pronouns and name was also perceived as a display of respect. “I have never been disrespected by any staff member … they use my preferred name when referring to me”. The provider spontaneously asking for pronouns was also greatly appreciated, “I was impressed when the doctor didn’t assume my gender, and even asked for my pronouns”.

A second facilitator was the providers’ collaborative attitude and shared decision-making skills (n = 7; 3%). This involved trusting and encouraging the patient’s input into healthcare decisions, especially concerning gender-affirming care. Participants reported, “he does listen to what I say and when it’s time for blood tests he trust me enough to let me have input”; “GP and I research together if there are medical problems”.

Lastly, some participants discussed the provider managing the records of the patient accurately as a positive experience, which was especially important considering existing system limitations (n = 5; 2%). For example, a participant reported: “[the provider] talked to the lawyers about changing my medical file to ‘reflect my truth’, and she changed my entire digital medical file … without me having to get my birth certificate changed”.

Approachability

Barriers

Some participants discussed the effect of fear and negative experiences on their healthcare-seeking behaviors, including a loss of trust and avoiding seeking care (n = 28; 12%). A participant shared “I received the worst treatment there [public health services] …This puts me off persuing publically [sic] funded surgeries as I don’t wish to go through mistreatment and shaming”. Another participant reported, “I ended up exiting the service due to the poor behavior… and was so put off by it I haven’t really tried to access healthcare for this since”. When accessing healthcare, some participants decided not to disclose their gender due to fear of mistreatment, “I often don’t reveal that i am non binary… as I don’t trust they would be respectful”.

Additional barriers included gatekeeping practices related to gender-affirming care (n = 16; 7%). Participants shared experiences where they were denied gender-affirming care based on providers’ opinions, or specific criteria required by the health system. For example, participants said, “I never should’ve had to wait 2 years for it [gender-affirming care] and lost them due to the terrible gatekeeping”; “I have been refused all requests for the care I asked for”. Some participants perceived that the system does not respect the patient’s decisions or their perspective, for example: “It would be a freak to have a medical professional who respects lived experience, and 25 years of self research rather than just requiring another referral”. Gatekeeping barriers have led some participants to lie to access care, “I’ve learned to lie about my hormone problems … to get help with them instead of getting shut off from all options”.

A further barrier that resulted in lower approachability was the lack of public information on gender-affirming care providers, and on general care trans-friendly providers (n = 7; 3%). Regarding their hormone therapy provider, a participant stated, “I had to go on word of mouth to find her because I could not find any official information on who has experience”. Due to the lack of publicly available information, personal research became key to accessing competent care, “I came to both of these GPs after exhaustive research looking for a GP that would suit, rather than just try a GP near me”.

Providers’ lack of knowledge regarding referral processes to access gender-affirming was an additional barrier shared by participants (n = 5; 2%). These included providers who were not informed about the availability of services and the pathways to access them. For example, a participant reported, “I paid for an appointment to discuss bottom surgery. He said he knew nothing about it”. In some cases, the provider also gave them inaccurate information, “The second one [GP] actually told me that my care wouldn’t be covered under the public system, even though it is”.

Facilitators

The single approachability facilitator was related to the instances where the provider was competent and proactive at navigating health services (n = 11; 5%). This involved being knowledgeable about available services and skillful at navigating their referral processes. For example, one participant shared, “I was able to access hormones via informed consent with a supporting letter from a counsellor through university.” A participant emphasized their doctor’s help in overcoming referral barriers, “doctors slipped me through past their burocrats [sic] for a mastectomy”. The provider advocating for the patient with other providers was also mentioned as a positive experience, “[the nurse] is an excellent … advocate when she needs to refer me to other organizations that do not know as much”.

Affordability

Affordability barriers reported by participants related to the cost of accessing private providers due to public options being too scarce or inadequate (n = 3; 1%). A participant commented, “I don’t particularly want to pay an extra $20 just to make sure I’m treated with respect, but apparently that’s what it takes”. This illustrates how existing barriers resulted in some participants incurring additional financial costs to avoid them.

Discussion

This research is among the few qualitative studies that have used a large sample to explore different aspects of healthcare access for transgender people. Our study is also contributing to the emerging research using Levesque and colleagues’ healthcare access model (2013) to analyze healthcare access experiences for transgender people. Transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand see their healthcare experiences affected by barriers within all dimensions of healthcare access (see for a summary), which resemble the ones reported in international research (e.g. Lerner & Robles, Citation2017). This breaches transgender people’s right to healthcare of adequate standards, which is reflected in transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand being less likely to access general healthcare when needed than cisgender people (Fenaughty et al., Citation2023), acting as a contributor to existing health inequities (Whitehead & Dahlgren, Citation2007).

Table 3. Summary of barriers and facilitators experienced by transgender people accessing healthcare in aotearoa/New Zealand.

Concerning availability and accommodation, a predominant issue identified in this study was the lack of provider competence in caring for transgender patients in both general and gender-affirming care settings, resulting in positive experiences being rare and in some participants traveling long distances to access competent care, as highlighted by previous local and international research (Bartholomaeus et al., Citation2021; Fraser, Citation2020; Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023; Lerner & Robles, Citation2017; Lindroth, Citation2016; Pampati et al. Citation2021; Safer et al., Citation2016; Snow et al., Citation2022; Tan et al., Citation2022; Veale et al., Citation2019; Withey-Rila et al., Citation2023). International research has shown that providers acknowledge this training gap and its adverse effects on their practice (Burgwal et al., Citation2021; Christopherson et al., Citation2021; Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023; Korpaisarn & Safer, Citation2018). This gap reflects a healthcare system attitude that erases the existence of transgender individuals and their unique healthcare needs—a manifestation of cisgenderism (Bartholomaeus & Riggs, Citation2018). Regarding competent gender-affirming care, it is important to note that in Aotearoa/New Zealand access to gender-affirming hormones has been predominantly provided by public secondary care services, but is now increasingly provided by primary care services (Carroll et al., Citation2023; Ker et al., Citation2021; Ker et al., Citation2020; Veale et al., Citation2023). This means that the competence of GPs is an important component of its provision. The availability of gender-affirming services outside hormone treatment has increased throughout the last years, but there is still limited capacity and long waitlists for some, as well as great variation across regions (Oliphant, Citation2021). This is reflected in the high rates of unmet need for some gender-affirming treatments (e.g. 67% for chest reconstruction, and 42% for hysterectomy surgery; Veale et al., Citation2019)

Participants noted additional availability and accommodation barriers in emergency settings, hospitals, and gendered services, suggesting that encountering unfamiliar providers induces anticipatory stress and anxiety. Barriers within gendered services speak of these healthcare settings’ unpreparedness and marginalizing practices which are a cisgenderist mechanism that gives a lower social status and right to care to transgender people (Bartholomaeus & Riggs, Citation2018). This issue has also been raised in international research conducted with participants living in several countries (Eder & Roomaney, Citation2023; Harb et al., Citation2019).

Availability/accommodation findings underscore a significant mismatch between transgender healthcare needs and the characteristics of the Aotearoa/New Zealand healthcare system. Competent care appears scarce and reliant on individual providers’ willingness to self-educate rather than on established health policy. Training regarding gender diversity and basic transgender health needs to be included within the educational curriculum for all healthcare practitioners, with a special focus on emergency rooms and after-hour service workers. This may be achieved by including transgender patients in clinical case studies used in training, rather than in stand-alone sessions (Carroll & Gray, Citation2021). Previous researchers have noted an interest among teaching staff in Aotearoa/New Zealand to enhance healthcare professionals’ education in this area, emphasizing collaboration with the transgender community (Treharne, Blakey, et al., Citation2022). International research has shown that training raises providers’ self-perceived competence to work with transgender people (Burgwal et al., Citation2021; McInnis, Gauvin, & Pukall, Citation2021). Administrative healthcare staff should also receive training in this area, as they participated in many of the negative experiences shared by participants in this and previous studies (Tan et al., Citation2022). This training may be provided by healthcare organizations to employees, but only the minority of regional public health services in Aotearoa/New Zealand currently offer this (Oliphant, Citation2021).

Conversely, providers possessing basic knowledge about transgender people or gender-affirming care were valued facilitators. In line with local findings (Withey-Rila et al., Citation2023), the extent of this knowledge was very varied across providers. On the other hand, acknowledging expertise limits and being open to self-education was also appreciated. Availability and accommodation facilitators have not received much emphasis in previous international research, with only a few studies based in Australia focusing on them, to the authors’ knowledge (Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020; Riggs et al., Citation2014). We found facilitators in this dimension to be largely related to the provider’s individual characteristics or interests, which counteracted some of the healthcare system’s barriers. Nevertheless, as participants emphasized, systemic change is necessary to address existing barriers appropriately.

Concerning acceptability and appropriateness, experiences of mistreatment and disrespect in healthcare, including verbal violence, non-verbal gestures, invasive questions, and misgendering, were common among participants, aligning with other local (Veale et al., Citation2019), United States, and Australia studies (Eder & Roomaney, Citation2023; Eisenberg et al., Citation2020; Grant et al., Citation2011; Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020; Pampati et al., Citation2021; Vupputuri et al., Citation2021). Such practices are examples of gender-related victimization that can contribute to chronic gender minority stress, that is, socially based stress experienced by gender minorities (Testa, Habarth, Peta, Balsam, & Bockting, Citation2015). On the other hand, facilitators included a safe, respectful, understanding, and caring approach, which partially compensated for the lack of training on transgender issues (as also reported in Hall & DeLaney, Citation2021; Halliday & Caltabiano, Citation2020, Riggs et al., Citation2014, and others). A supportive attitude involves respecting the lived experience of transgender patients and the expertise they hold about themselves and their bodies (Wright et al., Citation2021). In the same manner as acceptability/appropriateness facilitators, these facilitators relied mostly on the individual provider’s characteristics.

A significant barrier highlighted by participants was providers imposing their opinions about gender-affirming care decisions and invalidating participants’ gender identity. This is reflected in Counting Ourselves participants being less likely to describe their GP as good at shared decision-making than the general population (Veale et al., Citation2019). These attitudes can act as gender non-affirmation (Testa et al., Citation2015) and are usually based on cisnormative expectations of gender (e.g. Lindroth, Citation2016), with concerning recent research highlighting some providers questioning the existence of transgender people altogether (Grant et al., Citation2023). This lack of involvement in healthcare decisions can compromise patients’ confidence in managing their healthcare, while providers who actively encouraged patient perspectives and worked in partnership with them were important facilitators, building on existing evidence (Hall & DeLaney, Citation2021; Pampati et al., Citation2021).

Additional acceptability and appropriateness barriers included healthcare system inconsistencies with recording name or gender, which was sometimes counteracted by providers who managed records carefully and accurately. Few other studies have heard participants’ voices sharing their frustrations with this, which might be due to researchers not reporting this as a separate category from verbal misgendering. Furthermore, in countries where healthcare is predominantly managed by one large public health agency, such as the case of Aotearoa/New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora, n.d.), there may be more frequent communication and information-sharing between providers, leading to more opportunities for records’ inconsistencies or errors.

Some non-binary participants reported additional acceptability/appropriateness barriers. These perceived there was an especially reduced space for them in the healthcare system, which often understands transgender identities through binarizing (accepting the existence of only two separate genders; Bartholomaeus & Riggs, Citation2018) pressuring them to conform to this (Moallef et al., Citation2022).

Barriers to acceptability and appropriateness reveal interpersonal attitudes from providers rooted in cisgenderist beliefs (Bartholomaeus & Riggs, Citation2018), reflecting a basic failing in creating positive experiences for transgender people in healthcare settings (Withey-Rila et al., Citation2023). Imposing attitudes can be manifestations of paternalism and misuse of power by healthcare providers (Goodyear-Smith & Buetow, Citation2001), infringing on transgender people’s patient rights, which in Aotearoa/New Zealand include being treated with respect, dignity, and freedom of discrimination (Health and Disability Commissioner Act Citation1994). Unsupportive experiences in healthcare settings are associated with higher psychological distress (Treharne, Carroll, Tan, & Veale, Citation2022), contributing to existing health inequities. Participants rarely mentioned complaining about the issues they faced, which might reflect a lack of information on how to do this, or a belief that this would not have any effect. This underscores a need for more accessible complaints processes and regular monitoring, along with accountability from providers. Training for healthcare providers and administrative staff should incorporate cultural safety to address harmful biases or attitudes toward transgender people that contribute to mistreatment and discriminatory behaviors (Curtis et al., Citation2019).

In the dimension of approachability, participants often cited fear of negative experiences as a reason for avoiding seeking care or concealing their gender identity. This aligns with existing research demonstrating the impact of negative experiences on care postponement and gender identity concealment in North America and Pakistan (James et al., Citation2016; Manzoor et al., Citation2022, Sperber et al., Citation2005; Tami et al., Citation2022), with anticipation and concealment being central components of gender minority stress (Testa et al., Citation2015). Fear of future events negatively affects a patient’s ability to trust healthcare providers (Tan et al., Citation2022; Levesque et al., Citation2013). Healthcare providers must acknowledge these impacts and work toward creating a safe and welcoming environment to build trust and improve access.

Perceived gatekeeping in accessing gender-affirming care was a significant concern for participants, leading some to misrepresent themselves to avoid barriers. Gatekeeping practices have been criticized for limiting access and adhering to cisnormative constructions of gender, in Australia and several European countries (Grant et al., Citation2023; Linander et al., Citation2017; Lindroth, Citation2016; Ross et al., Citation2023; Wright et al., Citation2021). Gatekeeping is also problematic as it may lead to transgender people accessing gender-affirming care through unsupervised methods (Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023). In Aotearoa/New Zealand, requirements to access gender-affirming hormones can differ greatly by location (Fraser, Citation2020) meaning that gatekeeping issues vary across the country. Referral procedures should integrate the patient’s decisions following the informed consent model of care as recommended by the Professional Association of Transgender Health in Aotearoa (PATHA, Carroll et al., Citation2023). This model upholds patients’ autonomy, designating them as the primary decision-makers of medical choices, while the provider’s role is to provide comprehensive information regarding the risks/benefits of medical treatments, and ensuring their safe and proper administration.

Some participants encountered providers with insufficient knowledge about gender-affirming care services, highlighting the importance of provider awareness and their referral processes, even if they are not the direct providers of these services (Eisenberg et al., Citation2020). Some of our participants also reported a lack of public information on the matter, meaning they relied on unofficial methods and personal research to find services. This is consistent with the minority of regional health services providing this information publicly across the country (Oliphant, Citation2021), revealing a concerning issue that has also been raised in the United States and the United Kingdom (Sperber et al., Citation2005; Vupputuri et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2021). Oliphant (Citation2021) noted that public health agencies in Aotearoa/New Zealand have increased the availability of this information, but it is still insufficient. Information regarding this type of care should be more readily available and consistent for patients. The PATHA has also suggested the development of a peer support network to aid transgender people in navigating healthcare services (Veale et al., Citation2023).

Within approachability, providers who were aware of available services and adept at navigating referral processes were considered facilitators, contributing to better continuity and consistency across healthcare settings. Continuity of care has been a previously reported facilitator in United States research (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017; Sperber et al., Citation2005), and may be particularly important in the Aotearoa/New Zealand context due to the reported barriers. Furthermore, providers who advocate for transgender patients with other providers contribute to the improvement of the general healthcare system (Withey-Rila et al., Citation2023).

Affordability barriers were mentioned by a few participants in the present study, who discussed the cost of accessing private providers due to publicly funded options being insufficient or inadequate. The low prevalence of this category may have been influenced by the wording of the question and its placement in the survey questionnaire. This contrasts with the high prevalence of cost as a barrier revealed by Counting Ourselves quantitative findings regarding both general and gender-affirming care (Veale et al., Citation2019), as well as international findings (Kirey-Sitnikova, Citation2023; Lerner & Robles, Citation2017; Ross et al., Citation2023). This study’s findings suggest that the high percentage of financial barriers reported by Counting Ourselves participants may be due to private providers being a means to avoid the multiple barriers and the inconsistency experienced in the public health sector.

On the other hand, the low prevalence of affordability as a category aligns with findings from studies using qualitative methodologies based in countries with predominantly public healthcare systems, such as Aotearoa/New Zealand (e.g. Bartholomaeus et al., Citation2021; Lindroth, Citation2016; Riggs et al., Citation2014). Affordability may be a more prominent category in countries where care is funded largely by private health insurance, with discriminatory insurance practices resulting in further barriers (Lerner & Robles, Citation2017).

Strengths, caveats, and areas for future research

This study conducted a comprehensive analysis of the healthcare experiences of transgender individuals in Aotearoa/New Zealand, identifying a broad spectrum of barriers and facilitators. To comprehend healthcare access fully, it is crucial to recognize and explore all dimensions of this concept. This was accomplished by examining participants’ experiences through the lens of a comprehensive healthcare model (Levesque et al., Citation2013), which integrates multiple previous conceptualizations and has gained increasing acceptance among researchers (Cu et al., Citation2021). This approach yielded a panoramic understanding of the subject matter, enabling future research to delve deeper into each identified category.

An additional strength of the study lies in the inclusion of positive aspects of healthcare experiences (facilitators) alongside the negative ones. Existing literature on transgender healthcare access has predominantly focused on barriers, making this study a valuable contribution. Examining facilitators of healthcare access is crucial, as it equips healthcare systems and providers with positive examples to replicate and promote.

Qualitative surveys have been used infrequently within qualitative research, with a perceived limitation being the lack of depth in responses and the lack of opportunity to ask further questions (Braun, Clarke, Boulton, Davey, & McEvoy, Citation2020). As Braun and colleagues noted, this criticism might not be warranted, as responses in qualitative surveys have frequently shown great detail, which is consistent with many of our responses showing reflection and analysis. Furthermore, qualitative surveys offer the advantage of being able to access a larger sample size and, as a consequence, include a wider range of perspectives within a group (Braun et al., Citation2020), which aligns with the diversity of barriers and facilitators found in this research. In line with this, surveys may be more accessible (except for literacy barriers noted below), more unobtrusive, and offer a higher sense of anonymity than other qualitative methods (Braun et al., Citation2020).

A limitation of qualitative survey data is that it might exclude participants with limited literacy skills (Braun et al., Citation2020). To address this limitation, the categories raised by this research could be further explored through qualitative interviews. An additional limitation was the experiences of participants aged 18-24 years old, and non-binary participants AFAB were possibly under-represented due to the demographic characteristics of participants who answered the open-text question. A higher likelihood of older participants answering open-text survey questions has been observed in previous studies (Cunningham & Wells, Citation2017). Research that specifically targets these under-represented demographic groups should be considered for future research.

Furthermore, positive healthcare experiences might be over-represented due to participants leaving an open-text response being more likely to describe their doctors positively than those who did not. This stands in contrast to prior evidence of negativity bias in open-ended survey questions (Poncheri, Lindberg, Thompson, & Surface, Citation2008; Reynolds, McKernan, & Sukalski, Citation2020), suggesting that, in the context of transgender people, dissatisfaction with the subject matter could result in a decreased likelihood of expending the effort to provide an open-text response. This is concerning in light of the multiple barriers already identified in the findings.

In regard to future research utilizing Levesque et al. (Citation2013) model, this study’s findings may be complemented by exploring the healthcare providers’ perspectives and experiences regarding the issues raised in the study, within each of Levesque et al. (Citation2013) model dimensions. The majority of literature using this model has focused on patients’ perspectives (Cu et al., Citation2021), leaving a gap to be addressed. Additionally, there is a need to investigate how the provider-based barriers and facilitators identified in this research interact with patient characteristics, as access is influenced by the interaction of supply-side and demand-side factors (Levesque et al., Citation2013). While this study highlighted participants’ fear of negative experiences as a demand-side factor, other aspects such as patients’ ability to engage, remain to be explored within the model.

Some of the categories we identified fit within more than one dimension of Levesque et al. (Citation2013) healthcare accessibility model, which is consistent with similar challenges that Levesque and other authors had in applying this framework to analyze responses (Cu et al., Citation2021; Richard et al., Citation2016). This confirms Levesque et al. (Citation2013) original observation on accessibility dimensions being interconnected and acting as a whole. Future studies using this model should consider this interconnectedness, as any single barrier encounter by transgender people has an impact on multiple aspects of accessibility.

A final consideration is that the wording of the question used in the current study was open and exploratory, allowing for a wide variety of themes to be addressed by participant responses. Future international qualitative surveys studying healthcare access for transgender people may also benefit from including more focused questions that address issues relevant to the local healthcare context. For example, in Aotearoa/New Zealand this may involve specific questions about gender-affirming experiences in primary versus secondary services, or more questions regarding the financial cost of accessing private healthcare providers and the reasons for doing so.

Conclusion

Our study analyzed the healthcare access experiences of transgender people in Aotearoa/New Zealand using qualitative data from an online survey. Participants reported several barriers, and a few facilitators, within all healthcare accessibility dimensions (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Some important barriers were the lack of trans-competent providers and inconsistency of care, disrespectful behaviors, and disregard for the patient’s decisions; while some facilitators included competent providers recommended by the trans community and supportive attitudes. These findings evidence multiple gaps in adequate healthcare for transgender people and the existence of cisgenderist attitudes within the healthcare system. Transgender health should be included in all healthcare providers’ and healthcare staff’s training. Monitoring and feedback processes are needed to ensure transgender patients are treated with respect in these settings. Regarding gender-affirming care, a collaborative approach between patient and healthcare provider should be encouraged. Further research may explore how the patient factors in Levesque et al. (Citation2013) model interact with the categories found in this research, as well as research on providers’ perspectices.

Ethical approval

The survey was approved by the Aotearoa/New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (18/NTB/66/AM01). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all the members of the transgender community who were part of the Counting Ourselves project and especially those who decided to share the experiences that are included in this study. We thank Kyle K.H. Tan (Ph.D.), a member of the Transgender Health Research Lab (University of Waikato), for his valuable input across the different stages of this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This article uses transgender as an umbrella term to refer to all people whose gender identity does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth, including non-binary identities.

2 District Health Boards have been disbanded as of 2022. These have been replaced by Te Whatu Ora, an agency that has taken over the planning and commissioning of services of the 20 former DHBs (Te Whatu Ora, n.Citationd.).

References

- Allison, M. K., Marshall, S. A., Stewart, G., Joiner, M., Nash, C., & Stewart, M. K. (2021). Experiences of transgender and gender nonbinary patients in the emergency department and recommendations for health care policy, education, and practice. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 61(4), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.04.013

- Alpert, A. B., Gampa, V., Lytle, M. C., Manzano, C., Ruddick, R., Poteat, T., Quinn, G. P., & Kamen, C. (2021). I’m not putting on that floral gown: Enforcement and resistance of gender expectations for transgender people with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(10), 2552–2558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.03.007

- Bartholomaeus, C., & Riggs, D. W. (2018). Transgender people and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bartholomaeus, C., Riggs, D. W., & Sansfaçon, A. P. (2021). Expanding and improving trans affirming care in Australia: Experiences with healthcare professionals among transgender young people and their parents. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1845223

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2020). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

- Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2016). Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the veterans health administration: A case–control study. LGBT Health, 3(2), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058

- Burgwal, A., Gvianishvili, N., Hård, V., Kata, J., Nieto, I. G., Orre, C., Smiley, A., Vidić, J., & Motmans, J. (2021). The impact of training in transgender care on healthcare providers competence and confidence: A cross-sectional survey. Healthcare, 9(8), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080967

- Carroll, R., & Gray, L. (2021). Diversifying clinical education case studies. The Clinical Teacher, 18(5), 494–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13369

- Carroll, R., Nicholls, R., Carroll, R. W., Bullock, J., Reid, D., Shields, J., Johnson, R., Oliphant, J., McElrea, E., Whitfield, P., Veale, J. (2023). Primary care gender affirming hormone therapy initiation guidelines. Professional Association for Transgender Health Aotearoa. https://patha.nz/resources/Documents/Primary-Care-GAHT-Guidelines_Web_29-Mar.pdf

- Christian, R., Mellies, A. A., Bui, A. G., Lee, R., Kattari, L., & Gray, C. (2018). Measuring the health of an invisible population: Lessons from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(10), 1654–1660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4450-6

- Christopherson, L., McLaren, K., Schramm, L., Holinaty, C., Ruddy, G., Ruddy, G., Boughner, E., Clay, A. T., McCarron, M., & Clark, M. (2021). Assessment of knowledge, comfort, and skills working with transgender clients of Saskatchewan family physicians, family medicine residents, and nurse practitioners. Transgender Health, 7(5), 468–472. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0181

- Cu, A., Meister, S., Lefebvre, B., & Ridde, V. (2021). Assessing healthcare access using the Levesque’s conceptual framework– a scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01416-3

- Cunningham, M., & Wells, M. (2017). Qualitative analysis of 6961 free-text comments from the first national cancer patient experience survey in Scotland. BMJ Open, 7(6), e015726. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015726

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

- Downing, J., Lawley, K. A., & McDowell, A. (2022). Prevalence of private and public health insurance among transgender and gender diverse adults. Medical Care, 60(4), 311–315. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001693

- Eder, C., & Roomaney, R. (2023). Transgender and non-binary people’s perception of their healthcare in relation to endometriosis. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2023.2286268

- Eisenberg, M. E., McMorris, B. J., Rider, G. N., Gower, A. L., & Coleman, E. (2020). “It’s kind of hard to go to the doctor’s office if you’re hated there.” a call for gender-affirming care from transgender and gender diverse adolescents in the United States. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(3), 1082–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12941

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fenaughty, J., Fleming, T., Bavin, L., Choo, W. L., Ker, A., Lucassen, M., Ball, J., Greaves, L., Drayton, B., King-Finau, T., Clark, T. (2023). Te āniwaniwa takatāpui whānui: Te irawhiti me te ira huhua mō ngā rangatahi | Gender Identity and young people’s wellbeing in Youth19. Youth19 Research Group, The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. https://www.youth19.ac.nz/publications/gender-identity-wellbeing

- Fraser, G. (2020). Rainbow experiences of accessing mental health support in Aotearoa Aotearoa/New Zealand (Doctoral thesis). Victoria University of Wellington]. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/9042

- Fraser, G., Brady, A., & Wilson, M. S. (2021). “What if I’m not trans enough? What if I’m not man enough?”: Transgender young adults’ experiences of gender-affirming healthcare readiness assessments in Aotearoa Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22(4), 454–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1933669

- Giblon, R., & Bauer, G. R. (2017). Health care availability, quality, and unmet need: A comparison of transgender and cisgender residents of Ontario, Canada. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2226-z

- Gonzales, G., & Henning-Smith, C. (2017). Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. The Milbank Quarterly, 95(4), 726–748. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12297

- Goodyear-Smith, F., & Buetow, S. (2001). Power issues in the doctor-patient relationship. Health Care Analysis: HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy, 9(4), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013812802937

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

- Grant, R., Russell, A., Dane, S., & Dunn, I. (2023). Navigating access to medical gender affirmation in Tasmania, Australia: An exploratory study. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2023.2276179

- Hall, S. F., & DeLaney, M. J. (2021). A trauma-informed exploration of the mental health and community support experiences of transgender and gender-expansive adults. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(8), 1278–1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1696104

- Halliday, L. M., & Caltabiano, N. J. (2020). Transgender experience of mental healthcare in Australia. Psychology, 11(01), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2020.111011

- Harb, C. Y. W., Pass, L. E., De Soriano, I. C., Zwick, A., & Gilbert, P. A. (2019). Motivators and barriers to accessing sexual health care services for transgender/genderqueer individuals assigned female sex at birth. Transgender Health, 4(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0022

- Health and Disability Commissioner Act. (1994). https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1994/0088/latest/DLM333584.html

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hyde, Z., Doherty, M., Tilley, P. J. M., Kieran, M., Rooney, R., Jancey, J. (2014). The first Australian national trans mental health study: Summary of results. School of Public Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/beyond-blue-s-strategic-plan-2020-2023/research-project-files/bw0288_the-first-australian-national-trans-mental-health-study–-summary-of-results.pdf?sfvrsn=f970ea_4University, Perth, Australia.

- Jain, H., Karthick, S., Keni, G., & Avudaiappan, S. (2022). Attitudes toward transgender persons among medical students of a tertiary health-care center: A cross-sectional exploratory study. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 4(3), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/26318318221107350

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

- Kawsar, M., & Linander, I. (2022). “It’s a patient safety issue” A qualitative study with care professionals on their experiences of meeting trans people in obstetric and gynaecological care. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 34, 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2022.100786

- Ker, A., Fraser, G., Fleming, T., Stephenson, C., da Silva Freitas, A., Carroll, R., Hamilton, T. K., & Lyons, A. C. (2021). ‘A little bubble of utopia’: Constructions of a primary care-based pilot clinic providing gender affirming hormone therapy. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1855999

- Ker, A., Fraser, G., Lyons, A., Stephenson, C., & Fleming, T. (2020). Providing gender-affirming hormone therapy through primary care: Service users. Journal of Primary Health Care, 12(1), 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC19040

- Kirey-Sitnikova, Y. (2023). Access to gender-affirming hormonal therapy in Russia: Perspectives of trans people and endocrinologists. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2023.2272145

- Kirkland, A., Talesh, S., & Perone, A. K. (2021). Health insurance rights and access to health care for trans people: The social construction of medical necessity. Law & Society Review, 55(4), 539–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12575

- Korpaisarn, S., & Safer, J. D. (2018). Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: A major barrier to care for transgender persons. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 19(3), 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-018-9452-5

- Lerner, J. E., & Robles, G. (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators to health care utilization in the United States for transgender people: A review of recent literature. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(1), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0014

- Lerner, J. E., Lerner, J. E., Martin, J. I., & Silva, G. (2022). To go or not to go: Factors that influence health care use among trans adults in a non-representative U.S. sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 1913–1925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02302-x

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Linander, I., Alm, E., Goicolea, I., & Harryson, L. (2017). “It was like I had to fit into a category”: Care-seekers’ experiences of gender regulation in the Swedish trans-specific healthcare. Health, 23(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459317708824

- Lindroth, M. (2016). ‘Competent persons who can treat you with competence, as simple as that’ - an interview study with transgender people on their experiences of meeting health care professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(23-24), 3511–3521. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13384

- Manzoor, I., Zartasha, H. K., Tariq, R., & Shahzad, R. (2022). Health problems & barriers to healthcare services for the transgender community in Lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 38(1), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.38.1.4375

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- McInnis, M. K., Gauvin, S., & Pukall, C. F. (2021). Transgender-specific factors related to healthcare professional students’ engagement in affirmative practice with LGBTQ + clients. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(3), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1905702