Abstract

Objective

Here we investigate the relationship experiences of TNB individuals, with a particular focus on (1) relationship status and structure; (2) dating motivations and dating app use; (3) minority stress in relational contexts, including rates and experiences of fetishization, and minority stress-related difficulties in relationship formation and maintenance; (4) rates of relationship violence, victimization, and online harassment; and (5) relationship outcomes, namely sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Method

316 TNB adults (M age = 26.84 years, SD = 7.47) completed a survey to assess their relationship experiences.

Results

Just over half the sample was in a romantic relationship; 68% were monogamous and 32% were consensually non-monogamous (CNM). Almost 75% of partnered individuals were satisfied in their relationship, and neither sexual nor relationship satisfaction differed by gender or relationship structure (monogamous vs. CNM). The highest rated motivation for dating was to find a love relationship, and the lowest rated motivation was for casual sex. Almost 70% reported difficulties finding a partner because of their gender identity or expression, and 63% reported having experienced fetishization. Compared with men and non-binary individuals, rates of fetishization were highest for women. Finally, high rates of online and in-person victimization were found, including verbal abuse (52%), sexual coercion (44%) and physical violence (34%).

Conclusion

Results provide new evidence about the relationship experiences of TNB adults. Results suggest that many TNB individuals form and maintain satisfying relationships, but also face significant minority stress-related challenges in relational contexts. More research into relationship interventions to better support TNB individuals is warranted.

Most people have a desire to form a committed and mutually satisfying romantic relationship at some point in their lives (Roberts & Robins, Citation2000), and relationship quality is a well-established predictor of mental health and well-being (Diener et al., Citation1999; Robles et al., Citation2014; Whisman & Baucom, Citation2012). Relationship science has devoted significant attention to the study of adult romantic relationships (Joel et al., Citation2020), yet most research has focused on heterosexual and cisgender adults in relationships. Transgender and non-binary (TNB) individuals have received relatively little attention in relation to their experiences of romantic relationships (Marshall et al., Citation2020). The aim of the present research was, therefore, to investigate the experiences of TNB adults in dating and romantic relationships, including relationship status and structure, dating motivations, minority stress-related experiences, fetishization, victimization, and relationship outcomes.

Relationship experiences of TNB adults

Many well-established predictors of relationship outcomes in the general population, such as communication patterns or attachment orientation (e.g. Joel et al., Citation2020) are likely to also be relevant to the relationships of TNB individuals. However, there are unique issues, both positive and negative, that are relevant to the relationships of TNB individuals. For instance, romantic relationships can be an important context in which TNB individuals and their partners explore conceptions of gender and experience personal and relational growth (Budge et al., Citation2017; Gunby & Butler, Citation2023; Lewis et al., Citation2021). Romantic relationships can also be an important source of identity affirmation, particularly in response to microaffirmations from partners, referring to relatively small gestures and behaviors that positively affirm a person’s identity (Flanders, Citation2015; Pulice-Farrow et al., Citation2019). Some TNB individuals report that their relationships get stronger following disclosure of transgender identity (Riggle et al., Citation2011) and, among couples who remain together following gender affirmation, improvements in communication and affirming sexual experiences have been reported (Motter & Softas-Nall, Citation2021). Nonetheless, TNB individuals also face unique challenges associated with minority stress that are likely to impact the development, maintenance, and experience of romantic relationships.

According to minority stress theory, minority group members are often faced with unique stressors that result from societal stigma and place them at increased risk of poor mental health (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003; Testa et al., Citation2015). Distal stressors are external sources of stress, such as experiences of victimization, rejection, or discrimination, whereas proximal stressors are internal sources of stress that result from distal stressors, such as internalized transphobia—referring to the process of internalizing negative societal beliefs about TNB people (Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012). Much evidence suggests that minority stressors are associated with poorer mental health and well-being (Bockting et al., Citation2013; Cronin et al., Citation2019; Gamarel et al., Citation2014), and can undermine support-seeking (Cronin et al., Citation2023) among TNB individuals. Minority stressors also have significant implications for romantic relationship functioning (e.g. Nguyen & Pepping, Citation2022).

Relationship status

Being in a satisfying romantic relationship is an important goal for many adults (Fletcher et al., Citation2015; Roberts & Robins, Citation2000), and although rates of singlehood are increasing (Girme et al., Citation2023; Pepping et al., Citation2018), evidence from the general population suggests that most US adults are partnered (approximately 70%; Pew Research Center, Citation2020, Citation2022). There is limited research pertaining to relationship status among TNB adults, though in a large study of N = 1613 TNB adults, approximately 57% reported being currently in a romantic relationship (Holt et al., Citation2023). Similarly, in a study of N = 345 TNB adults, Fuller & Riggs, Citation2021 found that about 64% of participants were currently in a romantic relationship. The somewhat higher rates of singlehood among TNB adults relative to the general population may reflect that gender minority individuals face a range of additional challenges that undermine relationship functioning. Nonetheless, the fact that more than half of TNB adults appear to be currently in relationships (Fuller & Riggs, Citation2021; Holt et al., Citation2023) suggests that romantic love is an important goal for many TNB individuals.

Relationship structure

Among those who are partnered, it is important to investigate the ways in which TNB individuals structure their relationships. Around one in five US adults report having engaged in consensual non-monogamy (CNM)—referring to a relationship arrangement whereby partners consent to each other engaging in concurrent sexual and/or romantic relationships—at least once in their lives (Haupert et al., Citation2017). CNM relationships disrupt cis-normative and hetero-normative expectations (Barker, Citation2005) and evidence suggests sexual and gender minority individuals are more likely to engage in CNM relationships than the general population (Balzarini et al., Citation2019; Haupert et al., Citation2017). For instance, in a large study of N = 1613 TGD adults (Holt et al., Citation2023), 56.9% reported being currently in a relationship, of which 381 (41.5% of partnered individuals) were involved in some form of CNM relationship.

CNM relationships are often still viewed as being less fulfilling and of lower quality compared to monogamous relationships (Conley et al., Citation2013; Holt et al., Citation2023) despite research suggesting otherwise (Conley et al., Citation2017). In one notable exception, and to the best of our knowledge the only study to address this question among TNB individuals, Holt et al., Citation2023 found that TNB individuals in non-monogamous relationships were less satisfied than those in monogamous arrangements. However, the measurement of relationship quality was limited, and further research is needed to address this question using measures with more well-established psychometric properties.

Dating motivations and dating app use

Dating online or via smartphone applications has become a common way to meet potential romantic and sexual partners. Since Tinder added features for TNB people to select their preferred gender in 2016, more than three million TNB users have used this app (Steinmetz, Citation2016). Dating apps are primarily designed for users to meet potential romantic and sexual partners, though recent research suggests various additional motivations for using dating apps, including self-worth validation, and excitement (Clemens et al., Citation2015; Sumter et al., Citation2017). Some research has examined motivations for dating app use among sexual minority individuals (Jayawardena et al., Citation2022), though less is known about the relative importance of various motivations for dating app use among TNB individuals. Given that TNB adults are often faced with pathologizing and stigmatizing stereotypes, particularly in relation to sex and intimacy (Anzani et al., Citation2023), it seems important to clarify the relative importance of various motivations for dating.

Rejection, disclosure, and relationship instability

In addition to the mental health implications of minority stress, TNB individuals face significant challenges associated with minority stress in the context of romantic relationships (Blair & Hoskin, Citation2019; Gamarel et al., Citation2014; Riggs et al., Citation2018). First, and related to minority stress, TNB people can face difficulties forming and maintaining romantic relationships. For instance, heterosexual and cisgender individuals have been shown to exclude TNB individuals from their dating pool at high rates (Blair & Hoskin, Citation2019). Further, TNB people often describe dating as being highly challenging due to stigma, concerns about discrimination and rejection, and because of access to a more limited dating pool (Araya et al., Citation2021). In addition, managing disclosure of one’s gender history or identity to a potential partner can be particularly challenging and cause significant stress for TNB individuals (Platt & Bolland, Citation2017). On one hand, disclosure provides greater certainty and safety for a TNB person, but it can also increase the risk of rejection and subsequent distress (Fernandez & Birnholtz, Citation2019). Finally, managing gender transition/affirmation in the context of a romantic relationship can lead to partners questioning their own sexual identity which, at times, can be major reason for relationship break-up (Marshall et al., Citation2020; Meier & Labuski, Citation2013).

Sexual fetishization

Another commonly reported relationship challenge for TNB individuals is dealing with fetishization from partners or prospective partners (Fernandez & Birnholtz, Citation2019). Fetishization has been defined as “sexual investment in transness as an overvalued sexual object rather than holistic individual” (Anzani et al., Citation2021, p. 2). A recent study of 466 TNB adults (transfeminine, transmasculine, non-binary, and agender) aged 18–64 recent study found that nearly 38% reported having experienced fetishization at some point in their lifetime, and 26.2% reported “maybe” having experienced fetishization; the distribution of responses did not differ by gender (Anzani et al., Citation2021). These fetishization experiences occurred across a range of situations, including interpersonal interactions (63.5%), dating apps (53.2%), and social media (56.9%). In a qualitative study of 15 transgender and non-binary adults (Mage = 22.67 years), Griffiths and Armstrong (Citation2023) found that participants reported frequent and explicit experiences of fetishization when using online dating apps.

Qualitative research suggests that the experience of being fetishized as a TNB person can be associated with distress and worry that potential cisgender partners might only be interested in them because they are transgender (Riggs et al., Citation2018). Similarly, participants reported that disclosing their gender status was vital for their safety, but also made them vulnerable to fetishization (Riggs et al., Citation2018). The fear of being fetishized when dating appears to be a significant source of stress (Anzani et al., Citation2021; Riggs et al., Citation2018) and may interfere with efforts to form meaningful connections and relationships with others. Although evidence clearly suggests that TNB fetishization occurs relatively frequently, less research has focused on the different forms it may take, the situations in which it may occur, and the extent to which experiences of fetishization vary by gender.

Victimization, violence, and online harassment

Intimate partner violence (IPV) comprises various types and levels of abuse that occur in intimate relationships, including physical violence and abuse, as well as psychological and sexual abuse. TNB people experience intimate partner violence (IPV) at substantially higher rates relative to their cisgender counterparts (Peitzmeier et al., Citation2020; Reuter & Whitton, Citation2018). For instance, in a sample of N = 7572 individuals presenting to a community health center, Valentine et al. (Citation2017) found that transwomen (Adjusted OR = 5.0), transmen (Adjusted OR = 2.4), and non-binary individuals (Adjusted OR = 3.1) reported significantly greater odds of IPV relative to cisgender women. Similarly, meta-analytic evidence suggests that TNB people are 1.7 times more likely to have experienced IPV relative to cisgender individuals (Peitzmeier et al., Citation2020).

The higher rates of IPV among TNB populations extends to dating apps, with recent evidence highlighting that gender minority individuals experience more digital and online harassment and abuse relative to their cisgender peers (Powell et al., Citation2020). It is important to note that the findings of Powell and colleagues included harassment and abuse in the context of romantic partners, but were not solely perpetrated by partners. Nonetheless, qualitative research highlights that issues of safety and vulnerability to experiencing violence are key concerns affecting TNB individuals when using dating apps (Albury et al., Citation2021). Rates of IPV and online harassment and victimization are clearly higher among TNB individuals relative to their cisgender counterparts. Yet less is known about the various forms such harassment and victimization can take, particularly in relation to online harassment among TNB communities. Given TNB individuals often have unique concerns around disclosure and outness, particularly online (Fernandez & Birnholtz, Citation2019), IPV and victimization perpetrated against TNB people can take unique forms, including public exposure or other threats to safety. More research is needed to identify the extent to which these experiences occur in the context of TNB relationships.

Relationship outcomes: sexual and relationship satisfaction

Remarkably little research has investigated sexual and relationship quality among TNB adults, and of the studies that have investigated such outcomes, results have been mixed. For instance, Holt et al. (Citation2023) found that only 32.4% and 47.1% of those in relationships were satisfied with the sexual and romantic aspects of their relationships, respectively; as mentioned above, however, measurement of relationship quality had limitations. In a sample of N = 345 TGD adults, Fuller and Riggs (Citation2021) found that those in relationships (N = 220) were, on average, satisfied in their relationships, with mean scores falling somewhat higher than the cutoff for relationship distress. However, the proportion of individuals in satisfied vs. unsatisfied relationships was not reported.

The present research

The romantic relationship experiences of TNB individuals have not been widely researched. This is unfortunate as better understanding the romantic relationships of TNB individuals has implications for both individual and relationship-based interventions designed to improve mental health and relational functioning among TNB people. The aim of this research was to examine relationship and dating experiences of TNB individuals, with a particular focus on the following: (a) relationship status and structure; (b) dating motivations and online dating app use; (c) minority stress-related factors, including rates and experiences of fetishization, and difficulties in relationship formation and maintenance due to gender identity or expression; (d) rates of relationship violence, victimization, and online harassment in the context of romantic relationships; and (e) relationship outcomes, namely sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, specific hypotheses were not developed, though the following research questions guided the present study:

How do TNB individuals structure their relationships? And does relationship quality differ by relationship structure (monogamous vs. consensually non-monogamous)?

What are the primary dating and relationship motivations among TNB individuals? And to what extent do TNB individuals use online dating apps to meet prospective partners?

Given high rates of gender-related stigmatization broadly, to what extent would TNB individuals experience gender-related stigmatization and minority stress in the context of dating and romantic relationships, including overt relationship difficulties as well as other forms of stigmatization such as fetishization and difficulties in relationship formation?

Given the high rates of violence and victimization experienced by TNB individuals broadly, to what extent would specific forms of violence and victimization be experienced in the context of romantic relationships, both in person and online?

To what extent would TNB individuals be satisfied in their relationships (i.e., relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction)? Further, given that sexual activity is not limited to only those in relationships, we also examined sexual satisfaction in both single and partnered TNB individuals.

These questions will be investigated with TNB adults as a group, and separately by gender to assess whether relationship experiences vary by gender identity.

Method

Participants

Participants were 316 TNB adults ranging in age from 18 to 60 years (M age = 26.84 years, SD = 7.47). As displayed in , just over 75% identified as non-binary and/or gender diverse, with the remainder identifying as either a man or woman.Footnote1 Most were assigned female at birth. Almost 80% of the sample was White, with the next most frequently reported ethnicities being Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Black. Regarding sexual orientation, majority identified as either bisexual, pansexual or queer. Nearly all participants had completed Highschool education, and more than half had completed some form of tertiary education. The sample was roughly evenly split between those who were single and those in a relationship. Approximately 60% of the sample lived in a European country, almost a quarter were from North America (either the USA or Canada), and the remainder were from other regions including Oceania, Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia. For inclusion in the present research, participants were required to: (a) identify as transgender, gender diverse, non-binary and/or another non-cisgender identity; (b) be aged 18 or over; and (c) be fluent in English. An additional 46 individuals provided responses but were excluded for either not meeting the inclusion criteria or for not completing majority of the questionnaire.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample.

Measures

Relationship status and structure

Participants were asked “Are you currently in a romantic relationship or relationships?” (yes or no). Those who indicated they were partnered were then asked “How many relationships are you currently in?” and could select numbers between 1 and 5, or could select “more than five.” Participants were asked to indicate the structure of their relationship/s (1 = “monogamous”; 2 = “open relationship”; 3 = “polyamorous; 4 = “another descriptor” (please specify). Only 4 individuals selected “another descriptor” and responses reflected some form of non-monogamy. We therefore dichotomized responses (monogamous vs. non-monogamous) to allow for testing of group differences. Finally, participants were asked “How long have you been in a relationship with this person? (in years).”

Dating app use & motivations

Participants were asked if they had used any form of online dating or dating applications within the past 12 months (yes vs. no) and were asked which dating app they used the most. For those who had used online/dating apps within the past year, we used four subscales (24 items) from the 46-item Tinder Motivation Scale which assesses motivations for using dating apps (Sumter et al., Citation2017). In the present research, we used the following subscales: love (e.g. “To find a romantic relationship”); casual sex (e.g. “To talk about sex”); ease of communication (e.g. “Easier to communicate online”), and self-esteem validation (e.g. “To improve my self-esteem”). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item reflected their motivation for using dating apps and websites on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree). This scale has demonstrated sound psychometric properties (Sevi, Citation2019) and displayed acceptable internal consistency for all subscales in the present sample (α = .79–.86).

Two subscales of the Facebook Motivation Scale (Smock et al., Citation2011) were used, namely escapism (e.g. “So I can get away from what I’m doing”) and companionship (e.g. “Because it makes me feel less lonely”). In the present study, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item reflected their motivation for using dating apps and websites (as opposed to Facebook) on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree). Internal consistency was high for both escapism (α = 0.85) and companionship (α = 0.84).

Relationship difficulties

We used one item from the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience (GMSR) Measure (Testa et al., Citation2015) to assess difficulties in romantic relationships. Specifically, participants were presented with the following statement “I have had difficulty finding a partner, or have had a relationship end, because of my gender identity or expression” and were asked to indicate the extent to which it applied to them using the following options (never; yes, before age 18; yes, after age 18; and yes, in the past year). Participants could select more than one response. We then formed two dichotomous variables based on the above responses: lifetime difficulties (yes or no), and past year difficulties (yes or no).

Sexual fetishization

Following Anzani et al. (Citation2021), we asked participants “In your experience have you ever felt fetishized?” In addition, participants were informed: “In this survey, fetishization means the act of making someone an object of sexual desire based on some aspect of their identity—in this case, being trans, gender diverse, or non-binary.” They were asked to respond either yes or no. Those who indicated that they had experienced fetishization were then asked to indicate in which situations this had occurred and could select all that applied: (1) social media; (2) dating apps or online dating; (3) when on a date/with partner; (4) other (non-romantic) interpersonal situations.

To obtain continuous data on fetishization experiences, the full sample was asked to respond to the following four questions (1) “I am seen as a sexual object because I am TNB”; (2) “Dating partners are only interested in me because I am TNB”; (3) “Sexual partners are only interested in me because I am TNB”; and (4) “I have felt objectified or fetishized because I am TNB”). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1= never to 5 always).

Dating violence and victimization

To measure dating violence and victimization, we used a four-item measure (Bonomi et al., Citation2012; Van Ouytsel et al., Citation2017) that assessed the frequency with which a person had experienced specific behaviors in the context of a romantic relationship or sexual partner (e.g. “A partner has hit, slapped, scratched, pushed, bitten or hurt me in a physical way”). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert Scale (1= never to 5 = often). This scale correlates with theoretically relevant factors (Van Ouytsel et al., Citation2017) and internal consistency was high in the current sample (α = 0.85).

Online harassment

The 8-item Digital Direct Digital Aggression scale (Reed et al., Citation2017) was used to measure experiences of online harassment perpetrated by a current or former romantic or sexual partner. Participants responded to statements depicting a range of behaviors (e.g. “Using the internet or a cell/mobile phone, my dating partner posted a mean or hurtful public message”) on a 5-point Likert Scale (1= never to 4 = often). For ease of interpretation, and given a lack of variability at the higher end of the scale, we dichotomized these items to indicate whether they had experienced the particular form of online victimization (yes or no).

Relationship satisfaction

We used the four-item version of the Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-4; Funk & Rogge, Citation2007) to assess relationship satisfaction (e.g. “Please indicate the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship”). The CSI-4 was developed using Item Response Theory analysis and has greater power to detect satisfaction and distress compared to other widely used instruments (Funk & Rogge, Citation2007). Scores on the CSI-4 range from 0 to 21, with higher scores reflecting greater satisfaction. Scores less than 13.5 reflect relationship dissatisfaction or distress. Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .93).

Sexual satisfaction

We used a modified version of the single-item Sexual Satisfaction Scale (Fisher et al., Citation2015; Mark et al., Citation2014) to assess overall sexual satisfaction. Specifically, we removed reference to one specific partner so that the question could be answered by those who were unpartnered. In addition, among those in non-monogamous arrangements, restricting this question to one partner would not accurately reflect general sexual satisfaction; for instance, an individual may have a primary partner where there is limited or no sexual activity, with sexual activity occurring in secondary relationships. Participants were asked “Over the past 4 wk, how satisfied have you been with your sexual relationship/s” and responded on a five-point Likert Scale (1 = “very dissatisfied”) to 5 (“very satisfied”). The single-item measure of sexual satisfaction correlates with longer measures of sexual satisfaction (Fisher et al., Citation2015; Mark et al., Citation2014) and has been used with both single and partnered individuals (Pepping et al., Citation2018).

Procedure

The study received ethics approval from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited through multiple channels, including paid Facebook and Twitter advertising, and using the crowdsourcing platform Prolific. Upon clicking the advertisement, participants were directed to the QuestionPro platform which contained the survey. They were first asked to read the Participant Information Statement and to provide consent if they agreed to participate. Participants completed the measures listed above, and some others that were not related to the current study (e.g. individual mental health and wellbeing measures). All responses were anonymous. Participants recruited via Prolific received $1.63 (USD) for participating.

Data analytic strategy

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 29.0 (IBM Corp Citation2022). Descriptive statistics, namely frequencies and percentages, were used to report the occurrence of particular experiences and arrangements, including relationship violence, relationship status, and relationship structure. Means and standard deviations were used to rate the importance of dating goals and experiences of fetishization. Chi Squared analyses tested whether there were significant gender differences on categorical outcome variables, and ANOVAs were used to test for gender differences on continuous outcome variables (e.g. relationship satisfaction).

Results

Relationship status and structure

Just over half the sample (51.3%) reported currently being in a romantic relationship (or relationships). Of those who were in a relationship, 53.1% currently lived with their partner. Most relationships were monogamous (67.9%), though a sizeable minority were involved in consensual non-monogamy (32.1% in total), including polyamory (16.7%), an open relationship (13%), or another consensually non-monogamous relationship (2.5%). Of those who were partnered, almost all reported having one current partner (92%), with the remainder reporting between two and four current romantic partners. Among partnered individuals, relationship duration ranged from less than a year to 37 years (M = 5.55 years).

Dating motivations and dating app use

Just under half the sample (N = 148; 46.8%) reported having used an online dating app or website within the last 12 months. There were no gender effects relating to the likelihood of using an online dating app or website χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.270, p = .530. Among those who had used a dating app within the last 12 months, Tinder (71.6%) and Grindr (4.1%) were the most used dating apps. presents, in order of importance, means and standard deviations for each dating app motivation for the full sample, and split by gender. The relative importance of each motivation was identical across all genders.Footnote2 As can be seen, using dating apps to find a love relationship was the highest rated motivation for the full sample and across all genders. Ease of communication, self-worth enhancement, and companionship were also highly rated motivations for dating app use, with mean ratings for each being above the mid-point of the scale. Use of dating apps for escapism, or to find casual sexual partners, were the two lowest rated motivations across all gender groups.

Table 2. Motivations for dating app use.

Relationship difficulties

Majority of participants (69%) reported having experienced difficulties finding a romantic partner because of their gender identity or expression at some point in their life, and about a quarter (24.4%) reported having difficulties within the past year. There were no gender differences in lifetime χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.316, p = .518 or past year χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.949, p = .377 difficulties finding a romantic partner. Lifetime difficulties were not related to current relationship status χ2 (2, n = 316) = 2.705, p = .100, though past-year difficulties predicted a greater likelihood of being currently single χ2 (2, n = 316) = 41.169, p < .001.

Sexual fetishization

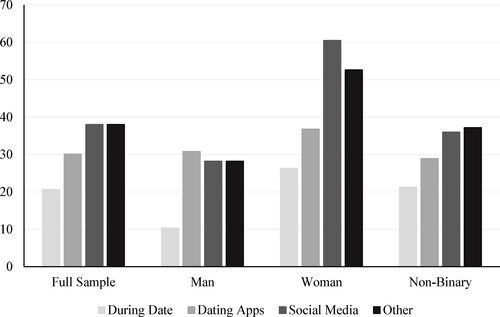

Almost two thirds of participants reported having felt fetishized at some point in their lives (N = 199; 63%). As displayed in , social media (38%) and other non-romantic interpersonal situations (38%) were the two most frequently endorsed situations in which participants had experienced fetishization, though dates (20.6%) and dating apps (30.1%) were also frequently endorsed. Women were significantly more likely to have experienced fetishization on social media relative to men and non-binary people χ2 (2, n = 316) = 10.188, p = .006, but there were otherwise no gender effects on fetishization situations.

As displayed in , relative to men and non-binary people, women were significantly more likely to report being seen as a sexual object and having experiences where they felt objectified or fetishized. Similarly, women were more likely to report experiencing dating partners (relative to men and non-binary people) and sexual partners (relative to non-binary individuals) as only being interested in them because of their gender/TNB status. There were no mean differences between men and non-binary individuals on experiences of fetishization.

Table 3. Fetishization experiences split by gender.

Dating victimization

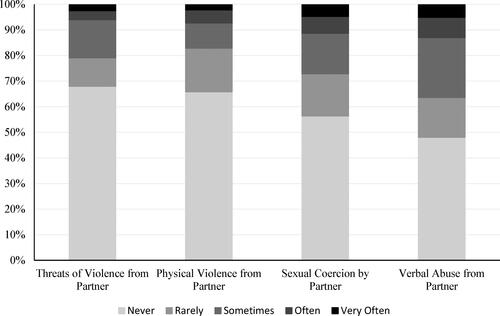

displays frequencies of relationship victimization experiences. Verbal abuse was the most frequently reported form of victimization, with more than half the sample (51.9%) reporting having experienced verbal abuse from a romantic partner. Sexual coercion was the next most common victimization experience, with 43.7% of the sample having experienced coercion from a partner to engage in sexual activity. Finally, 34.2% of the sample reported having experienced physical violence from a partner, and 32% had experienced threats of violence.

We tested for gender differences in experiences of dating victimization. Because of the significant skew in each of the four forms of dating victimization, we dichotomized these variables to indicate whether they had ever experienced the specific form of victimization (yes vs. no). Chi-square tests revealed no significant effects of gender (man vs. woman vs. non-binary) for physical violence χ2 (2, n = 316) = .415, p = .813; threats of abuse χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.126, p = .569; verbal abuse χ2 (2, n = 316) = .618, p = .734; or sexual coercion χ2 (2, n = 316) = 2.217, p = .330.

Online victimization

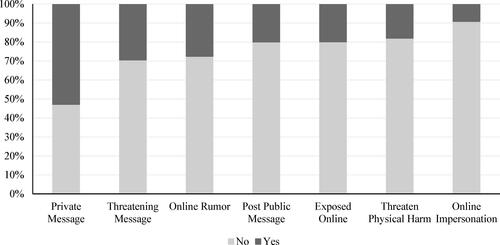

displays frequencies of online harassment and victimization experiences in the context of a romantic or sexual relationship. The most commonly reported experiences were having received a mean or hurtful private message (52.8%) or a threatening message (29.4%). In addition, 27.5% had experienced a rumor being spread online, 20% had been the victim of nasty public messages, and 20% had been exposed in some way without consent (e.g. shared an embarrassing photo or video without consent). Finally, 18% had received online threats of physical harm in the context of a romantic or sexual relationship, and 9.2% had been the victim of impersonation (pretended to be the participant or their partner).

We tested for gender differences in experiences of online victimization. Chi-square tests revealed no significant effects of gender (man vs. woman vs. non-binary) for harassing private messages χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.835, p = .400; harassing public messages χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.161, p = .560; online rumors χ2 (2, n = 316) = .518, p = .772; threatening messages χ2 (2, n = 316) = 1.185, p = .553; or threats of physical harm χ2 (2, n = 316) = 4.691, p = .096. Although the chi-square test found a significant effect for online impersonation χ2 (2, n = 316) = 8.663, p =.013, several cells had an expected count of <5 and thus results are unlikely to be reliable or interpretable.

Sexual and relationship satisfaction

Regarding relationship satisfaction, almost three-quarters of partnered individuals were satisfied in their relationships (N = 121; 74.7%). Approximately a quarter of those in relationships (N = 41; 25.3%) scored below the cutoff (scores falling below 13.5) indicating relationship dissatisfaction (Funk & Rogge, Citation2007). Relationship satisfaction did not differ between men (M = 15.22, SD = 2.51), women (M = 14.59, SD = 4.46), or non-binary individuals (M = 15.91, SD = 4.46); F (2, 159) = .981, p = .377. Satisfaction also did not differ between those in monogamous (M = 15.64, SD = 4.68) and consensually non-monogamous (M = 15.69, SD = 3.38) relationships, t (133.84) = −0.09, p = .93.

Sexual satisfactionFootnote3 differed by relationship status, such that partnered individuals (M = 3.57, SD = 1.20) reported greater sexual satisfaction than those who were single (M = 2.60, SD = 1.25), t (300) = −6.90, p < .001 (d = −0.79). Among single individuals, only 21.4% were moderately or very satisfied, 30.2% were equally satisfied/dissatisfied, and 48.3% were either moderately or very dissatisfied. In contrast, 61.4% of partnered individuals reported being either moderately or very satisfied with the quality of their sexual relationship/s, 18.3% indicated they were equally satisfied/dissatisfied, and 20.2% were either moderately or very dissatisfied. Among partnered individuals, there was no significant difference between those in monogamous (M = 3.57, SD = 1.20) and consensually non-monogamous (M = 3.57, SD = 1.22) relationships, t (83.76) = .02, p = .98. Sexual satisfaction also did not differ between men (M = 3.05, SD = 1.27), women (M = 3.16, SD = 1.30), or non-binary individuals (M = 3.08, SD = 1.33); F (2, 299) = .076, p = .929.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to examine romantic relationship experiences of TNB individuals. Specifically, we investigated (a) relationship status and structures; (b) dating motivations and online dating app use; (c) experiences of gender-related minority stress in relationship contexts, including rates and experiences of sexual fetishization, and difficulties in relationship formation and maintenance due to gender identity or expression; (d) the extent to which various forms of relationship violence and victimization, both in person and online, would be experienced by TNB individuals in the context of romantic relationships; and (e) relationship outcomes, namely sexual and relationship satisfaction.

Just over half the sample was in a romantic relationship, ranging from less than 1 year in duration to 37 years. Most relationships were monogamous (67.9%) though a sizable minority (32.1%) of partnered individuals were in CNM relationships. Almost 75% of partnered individuals were currently satisfied in their relationships, and neither sexual nor relationship satisfaction differed by gender or relationship structure (monogamous vs. CNM). Single individuals, however, were less satisfied with the quality of their sexual relationship/s than their partnered counterparts. Just under half the sample had used an online dating app or website within the past 12 months; the highest rated dating motivation was to find a love relationship, whereas the lowest rated motivation was for casual sex.

Although the above results suggest that many TNB individuals form and maintain satisfying romantic relationships, high rates of minority stress-related challenges in relational contexts were also found. Almost 70% of the sample reported having experienced difficulties at some point in their life finding a romantic partner because of their gender identity or expression; about a quarter (24.4%) reported such difficulties within the past year. Past-year minority stress-related difficulties predicted a greater likelihood of being currently single. Almost two-thirds of participants reported having experienced fetishization at some point in their lives, and women were significantly more likely to have experienced fetishization and sexual objectification compared with men and non-binary individuals. High rates of relationship victimization experiences were found; almost 52% and 44% reported having experienced verbal abuse or sexual coercion, respectively, and approximately 34% of the sample had experienced physical violence from a partner. Similarly, a sizeable number had experienced a rumor being spread online (27.5%) or had been exposed in some way without consent (20%) in the context of a romantic relationship. There were no reliable gender differences in experiences of online or in-person relationship victimization.

Relationship structure

Among those who were in a romantic relationship, almost 68% reported that their relationship was monogamous. Although about 20% of single adults in the general population are said to have engaged in consensual non-monogamy (CNM) at some point in their lives (Conley et al., Citation2017; Haupert et al., Citation2017), the present findings suggest somewhat higher rates of current engagement in CNM arrangements. This converges with recent observations that TNB individuals may be more likely to engage in CNM (Balzarini et al., Citation2019). Relatively little research has explored the relationship experiences of TNB individuals engaging in CNM, though evidence broadly indicates that monogamous and CNM relationships do not differ on indicators of relationship quality (Conley et al., Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2018). Further research is needed to explore CNM experiences in TNB populations.

Dating motivations and dating app use

Just under half the sample had used an online dating app or website in the past 12 months, and there were no gender differences in the likelihood of using a dating app. In line with research with largely cisgender samples (Timmermans & De Caluwé, Citation2017a), TNB individuals in the current study reported varied motivations and goals for use of dating apps. The most highly rated motivation for use of dating apps was to find a love relationship. The mean rating for this motivation in the present sample (M = 3.79) appears to be broadly similar to studies of largely cisgender participants (M = 4.01–4.18) (Timmermans & De Caluwé, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Ease of communication, self-worth enhancement, and companionship were also highly rated motivations for dating app use, with mean ratings for each being above the mid-point of the scale. Casual sex was the lowest rated motivation for dating app use across all genders (full sample M = 2.33), and somewhat lower than those reported in studies of largely cisgender participants (e.g. M = 2.59–3.01; Timmermans & De Caluwé, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). This, coupled with the finding that relationship-seeking was the highest rated motivation, suggests that forming a satisfying romantic relationship is a primary goal among TNB individuals as it is for cisgender individuals (Roberts & Robins, Citation2000). This is important as it challenges harmful stereotypes that TNB often face, particularly regarding sexuality and intimacy (Anzani et al., Citation2023).

Minority stress, relationship difficulties, and fetishization

Almost 70% of the sample reported having experienced difficulties finding a romantic partner because of their gender identity or expression at some point in their life, and almost a quarter within the past year. The finding of no gender differences suggests that TNB individuals of all genders experience minority stress-related challenges when trying to form or maintain a romantic relationship. This is unsurprising given evidence that many heterosexual and cisgender individuals may exclude TNB people from their dating pool (Blair & Hoskin, Citation2019). Further, a TNB person taking steps toward gender affirmation can have implications for partners and has been found to be a significant reason for relationship break-up (Marshall et al., Citation2020; Meier & Labuski, Citation2013). It is important to note, however, that although a high proportion of participants reported having lifetime difficulties finding a partner, more than 50% of participants were currently in a relationship and, of these, most (74.7%) were satisfied in these relationships.

In the present study, those who reported having difficulties finding a partner in the last 12 months due to their gender identity or expression were more likely to be currently single. At first glance, this finding differs somewhat from recent evidence that, among sexual minority individuals, experiences of discrimination tend to be higher among those who are partnered (Laming et al., Citation2023), likely because being in a same-gender relationship increases the visibility of one’s sexual orientation. However, in the case of sexual minority individuals in same-gender relationships, the source of the discrimination is from others in society, whereas among TNB individuals, the sources of discrimination and rejection may additionally include prospective romantic partners, which appears to undermine relationship formation.

Almost two thirds of participants (63%) reported having felt fetishized at some point in their lives, which converges with both qualitative evidence (Riggs et al., Citation2018) and recent quantitative evidence whereby 65% of TNB individuals reported experiences of fetishization (Anzani et al., Citation2021). Social media and other non-romantic interpersonal situations were the two most frequently endorsed situations (both 38%) where participants reported having experienced fetishization, followed by dating apps (30.1%). The latter converges with recent qualitative evidence that dating apps may be one context where fetishization is common (Griffiths & Armstrong, Citation2023). In-person dates were the least likely situation for fetishization to occur, which could reflect that people tend to initially screen prospective partners online prior to proceeding with an in-person date. This was not directly assessed in the current study, but future research may benefit from examining whether and how TNB individuals screen prospective dates or partners for fetishizing or objectifying behaviors.

Relative to men and non-binary individuals, women reported more experiences of being seen as a sexual object, feeling objectified or fetishized, and having concerns that dating partners are only interested in them due to their transgender status. Women also reported greater concern that sexual partners were only interested in them due to their transgender status (significantly higher than non-binary individuals). These findings suggest that, as with cisgender and heterosexual women (Fairchild & Rudman, Citation2008; Kozee et al., Citation2007), women are most likely to experience sexual objectification. Although TNB experiences of fetishization tend to be characterized by feelings of fear, disgust, and dehumanization, some do report positive (or a mix of negative and positive) experiences of fetishization (Anzani et al., Citation2021; Riggs et al., Citation2018; Tompkins, Citation2014). Further research is needed to investigate the conditions under which fetishization may be experienced positively or negatively, as it seems likely that these experiences would vary as a function of context, consent, and who is doing the fetishizing.

Relationship violence and victimization

More than 50% of the sample reported having experienced verbal abuse from a romantic partner, and a sizable number also reported having experienced sexual coercion (43.7%), physical violence (34.2%), and/or threats of violence (32%) from a partner. These findings converge with prior evidence of higher rates of intimate partner violence among TNB individuals relative to cisgender heterosexual people (Peitzmeier et al., Citation2020) and relative to sexual minority individuals (Brown & Herman, Citation2015). Regarding online victimization and harassment, more than half the sample reported having received harassing, mean, or abusive private messages from partners, and almost 30% had received a threatening message. Rumors (27.5%) and nasty public messages (20%) from romantic partners were also experienced by a sizeable minority of individuals. In addition, 20% reported having been exposed in some way by a partner online without consent. There has been only limited research pertaining to online victimization in romantic relationships among TNB populations, though some initial evidence of online sexual harassment also suggests that TNB individuals experience such harassment at high rates and are at greater risk than their cisgender counterparts (Wolbers et al., Citation2022). There were no reliable gender differences in experiences of in-person or online victimization in the context of romantic relationships, suggesting that TNB individuals are at higher risk of victimization in relationships across all genders.

Relationship outcomes: sexual and relationship satisfaction

Although the present sample experienced relatively high rates of minority stress-related challenges in the context of romantic relationships, about 75% of partnered individuals were satisfied in their relationship. These findings differ from those of Holt et al. (Citation2023) who found that only around 47% of TGD adults were satisfied in their romantic relationship. Of particular importance, relationship satisfaction did not significantly differ between those in monogamous and consensually non-monogamous relationships. Although this is consistent with findings from the broader literature on consensual non-monogamy (Conley et al., Citation2017), these results differ from those of Holt et al. (Citation2023) who found that TNB individuals in monogamous relationships displayed greater relationship satisfaction than those in CNM relationships. The differences between the present findings and those of Holt et al. (Citation2023) regarding relationship satisfaction may reflect limitations with the measurement of satisfaction used by Holt et al. (Citation2023); in the present research we used a short-form version of one of the most widely used and well-validated measures of relationship satisfaction, the Couple Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, Citation2007).

Sexual satisfaction was somewhat lower among those who were single relative to those in a current romantic relationship, which converges with evidence from the general population whereby sexual satisfaction is higher among those who are partnered (Pepping et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, there were no differences in sexual satisfaction between monogamous and non-monogamous relationship structures which, again, converges with the broader literature demonstrating that being in a CNM relationship structure does not negatively affect relationship outcomes (Conley et al., Citation2017).

Implications, limitations, and future directions

Results of the present research highlight a number of strengths and challenges faced by TNB individuals in relationship contexts. Findings indicate that TNB individuals are primarily seeking romantic relationships when dating, and often do so using online dating apps. More than half of the sample reported being in a romantic relationship at the time of the study, 75% of partnered individuals were satisfied in these relationships, and those in monogamous and non-monogamous relationships were equally satisfied. This suggests that many TNB individuals are successful in finding a romantic partner or partners and these relationships tend to be satisfying. Findings of high rates of fetishization, rejection, and dating violence, however, also highlight the significant risks and challenges faced by TNB individuals when seeking and/or being in romantic relationships.

Taken together, these findings have important implications for practitioners working with TNB individuals. Although it is important for practitioners to be aware of the risks and challenges faced by TNB in relationship contexts, it is equally important that practitioners are aware that many TNB individuals want, and are in, satisfying romantic relationships. It is important that practitioner training designed to enhance competency working with TNB individuals (e.g. Pachankis et al., Citation2022; Pepping et al., Citation2018) incorporates content on both strengths and challenges in the relationships of TNB people. The present findings also have important macro-level implications as they contradict common stereotypes, biases, and points of misinformation about TNB people that contribute to fetishization and other forms of minority stress (Anzani et al., Citation2023).

Reducing societal stigma and minority stress remains a critically important public health goal to reduce disparities in mental health and relationship outcomes between TNB individuals and their cisgender counterparts. However, while stigma and minority stressors exist, identifying ways to help TNB individuals cope with the effects of stigma remain important. It seems plausible that relationship interventions, such as relationship education or therapy (Halford & Bodenmann, Citation2013; Halford & Pepping, Citation2019), might help to strengthen relationships and buffer the effects of minority stressors, though such interventions would need to be tailored to be appropriate and relevant to the relationships of TNB individuals, as has been done with interventions for sexual minority couples (Pepping et al., Citation2017; Whitton & Buzzella, Citation2012).

Relationship interventions have been successfully modified for sexual minority relationships (e.g. Pepping et al., Citation2020; Whitton et al., Citation2016, Citation2017) though to the best of our knowledge there are no randomized controlled trials of tailored interventions for relationships with one or more TNB partner. Similarly, some relationship education programs—primarily developed for young adults or youth—have been trialed individually and are designed to teach relationship knowledge and skills needed to form positive relationships (Davila et al., Citation2021; Hawkins, Citation2018; Simpson et al., Citation2018). Given the high rates of fetishization, victimization, and challenges in forming relationships (due to minority stress) found in the present research, perhaps interventions that teach skills relevant to these issues could help TNB individuals to navigate dating and relationship formation in a stigmatizing environment. In addition, particular attention should be paid to ensuring interventions are accessible given TNB individuals report significant barriers to accessing psychological services (Cronin et al., Citation2023; Lim et al., Citation2021).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to assess motivations for dating via dating apps in TNB individuals, the first quantitative study to explore various dimensions of fetishization, and one of the first to examine victimization in the context of romantic relationships, both online and in-person. In addition, the size of the sample was reasonably large, particularly when compared with prior research into TNB romantic relationships. Nonetheless, there are some limitations of this study to address. First, participants were primarily white, non-binary individuals, and thus we cannot assume the results of the present study generalize to all groups of TNB individuals. Similarly, although participation was not restricted to specific geographical locations—a strength of the present study given most research has focused only on North American contexts—most participants were, nonetheless, from either a European (60.7%) or North American (23.7%) country. It is also important to note that the legal and social contexts regarding TNB rights differs markedly between countries, within countries (e.g. state-based differences in the USA), and within continents (e.g. Eastern vs. Western Europe). Given the limited research on TNB relationships to date, our aim was to provide a broad assessment of TNB relationship experiences. We therefore did not target recruitment to get a globally representative sample. Results should be interpreted with this in mind, and further research is needed to assess potential differences in relationship experiences based on geographical region and sociopolitical landscape.

Second, the inclusion criteria for the present study required that participants were fluent in English; this was necessary as it was not feasible to translate, back-translate, and validate all measures for the large number of potential languages. However, restricting participation to only those who are fluent in English does limit the generalizability of findings and thus we cannot assume that results apply to non-English speaking TNB individuals. Third, although we used validated self-report measures wherever possible, there are currently no well-established measures of TNB fetishization. Using existing research, we developed items to tap into experiences of fetishization, though further work is needed to more fully assess fetishization among TNB individuals. The measures included in the present study were largely focused on challenges faced by TNB people in relationships. Although this provides important information, it does not capture the full range of relationship experiences among TNB individuals. There is a need for further research on strengths and the positive aspects of TNB relationship experiences.

Finally, here we assessed whether participants had experienced difficulties finding or maintaining a relationship because of their gender identity or expression and found that a large proportion of the sample had experienced such difficulties at some point in their lives. It is important to note, however, that rejection and difficulties forming or maintaining relationships can result from many factors (e.g. Halford & Pepping, Citation2017; Pepping et al., Citation2018) and are painful human experiences that are not restricted to one group (e.g. Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; MacDonald & Leary, Citation2005). According to minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003; Testa et al., Citation2015), rejection on the basis of one’s transgender status represents a unique source of stress that adds to the general stressors—including rejection or relationship difficulties that are unrelated to gender—experienced by all members of society. It may be helpful for future research to include measures of both general and minority stressors, particularly when predicting psychosocial outcomes, to better tease apart the unique contribution of minority stressors.

As highlighted earlier, research into TNB relationships has received only limited attention to date. Further research is needed to explore diversity in TNB relationships, including both monogamous and CNM relationships. Similarly, future research efforts may investigate TNB online dating experiences, including whether and how TNB individuals screen prospective partners in relation to fetishization and other factors. Similarly, there is a need for research into the relationships of TNB individuals with more diverse samples, including greater cultural and gender diversity.

Ethical approval

The present research was approved by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee and all procedures were performed in accordance with 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments/comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Participants could select more than one gender option and could also self-describe. To allow for statistical comparisons across genders, we collapsed gender into three categories: those who selected only ‘man’ or only ‘woman’ were classified as ‘man’ or ‘woman’ respectively; those who selected ‘non-binary’, selected multiple gender options, or self-described a non-binary or gender diverse identity were classified as ‘non-binary and/or gender diverse.

2 Because these data pertain only to those who had used a dating app or website within the past 12 months (N = 148), there were insufficient numbers of participants within each gender category to reliably test for gender differences in mean ratings for each motivation.

3 N = 14 individuals did not provide data for the sexual satisfaction measure.

References

- Albury, K., Dietzel, C., Pym, T., Vivienne, S., & Cook, T. (2021). Not your unicorn: Trans dating app users’ negotiations of personal safety and sexual health. Health Sociology Review: The Journal of the Health Section of the Australian Sociological Association, 30(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1851610

- Anzani, A., Lindley, L., Tognasso, G., Galupo, M. P., & Prunas, A. (2021). “Being talked to like i was a sex toy, like being transgender was simply for the enjoyment of someone else”: Fetishization and sexualization of transgender and nonbinary individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(3), 897–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01935-8

- Anzani, A., Siboni, L., Lindley, L., Paz Galupo, M., & Prunas, A. (2023). From abstinence to deviance: Sexual stereotypes associated with transgender and nonbinary individuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 21(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00842-y

- Araya, A. C., Warwick, R., Shumer, D., & Selkie, E. (2021). Romantic relationships in transgender adolescents: A qualitative study. Pediatrics, 147(2). e2020007906. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-007906

- Balzarini, R. N., Dharma, C., Kohut, T., Holmes, B. M., Campbell, L., Lehmiller, J. J., & Harman, J. J. (2019). Demographic comparison of american individuals in polyamorous and monogamous relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1474333

- Barker, M. (2005). This is my partner, and this is my… partner’s partner: Constructing a polyamorous identity in a monogamous world. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 18(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530590523107

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Blair, K. L., & Hoskin, R. A. (2019). Transgender exclusion from the world of dating: Patterns of acceptance and rejection of hypothetical trans dating partners as a function of sexual and gender identity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(7), 2074–2095. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518779139

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

- Bonomi, A. E., Anderson, M. L., Nemeth, J., Bartle-Haring, S., Buettner, C., & Schipper, D. (2012). Dating violence victimization across the teen years: Abuse frequency, number of abusive partners, and age at first occurrence. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 637. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-637

- Brooks, V. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Press.

- Brown, T. N. T., & Herman, J. L. (2015). Intimate partner violence and sexual abuse among LGBT people. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

- Budge, S. L., Chin, M. Y., & Minero, L. P. (2017). Trans individuals’ facilitative coping: An analysis of internal and external processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000178

- Clemens, C., Atkin, D., & Krishnan, A. (2015). The influence of biological and personality traits on gratifications obtained through online dating websites. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.058

- Conley, T. D., Matsick, J. L., Moors, A. C., & Ziegler, A. (2017). Investigation of consensually nonmonogamous relationships: Theories, methods, and new directions. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 12(2), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616667925

- Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2013). The fewer the merrier?: Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2012.01286.x

- Cronin, T. J., Pepping, C. A., & Lyons, A. (2019). Internalized transphobia and well-being: The moderating role of attachment. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.018

- Cronin, T. J., Pepping, C. A., & Lyons, A. (2023). Mental health service use and barriers to accessing services in a cohort of transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary Adults in Australia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-023-00866-4

- Davila, J., Zhou, J., Norona, J., Bhatia, V., Mize, L., & Lashman, K. (2021). Teaching romantic competence skills to emerging adults: A relationship education workshop. Personal Relationships, 28(2), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12366

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21(3), 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0

- Fernandez, J. R., & Birnholtz, J. (2019). “I don’t want them to not know” investigating decisions to disclose transgender identity on dating platforms. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3359328

- Fisher, W. A., Donahue, K. L., Long, J. S., Heiman, J. R., Rosen, R. C., & Sand, M. S. (2015). Individual and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife couples: Dyadic analysis of the international survey of relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1609–1620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0426-8

- Flanders, C. E. (2015). Bisexual health: A daily diary analysis of stress and anxiety. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2015.1079202

- Fletcher, G. J., Simpson, J. A., Campbell, L., & Overall, N. C. (2015). Pair-bonding, romantic love, and evolution: The curious case of Homo sapiens. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(1), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614561683

- Fuller, K. A., & Riggs, D. W. (2021). Intimate relationship strengths and challenges amongst a sample of transgender people living in the United States. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 36(4), 399–412. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2019.1679765

- Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

- Gamarel, K. E., Reisner, S. L., Laurenceau, J.-P., Nemoto, T., & Operario, D. (2014). Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender Male Partners. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 28(4), 437–447. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037171

- Girme, Y. U., Park, Y., & MacDonald, G. (2023). Coping or thriving? Reviewing intrapersonal, interpersonal, and societal factors associated with well-being in singlehood from a within-group perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 18(5), 1097–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221136119

- Griffiths, D. A., & Armstrong, H. L. (2023). “They were talking to an idea they had about me”: a qualitative analysis of transgender individuals’ experiences using dating apps. The Journal of Sex Research, 61(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2176422

- Gunby, N., & Butler, C. (2023). What are the relationship experiences of in which one member identifies as transgender? A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Journal of Family Therapy, 45(2), 167–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12409

- Halford, W. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2013). Effects of relationship education on maintenance of couple relationship satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(4), 512–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.02.001

- Halford, W. K., & Pepping, C. A. (2017). An ecological model of mediators of change in Couple Relationship Education. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.007

- Halford, W. K., & Pepping, C. A. (2019). What every therapist needs to know about couple therapy. Behaviour Change, 36(3), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2019.12

- Haupert, M. L., Gesselman, A. N., Moors, A. C., Fisher, H. E., & Garcia, J. R. (2017). Prevalence of experiences with consensual nonmonogamous relationships: Findings from two national samples of single americans. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1178675

- Hawkins, A. J. (2018). Shifting the relationship education field to prioritize youth relationship education. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 17(3), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2017.1341355

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- Holt, M., Broady, T., Callander, D., Pony, M., Duck-Chong, L., Cook, T., & Rosenberg, S. (2023). Sexual experience, relationships, and factors associated with sexual and romantic satisfaction in the first Australian Trans & Gender Diverse Sexual Health Survey. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.2016540

- IBM Corp. (2022). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 29). [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

- Jayawardena, E., Pepping, C. A., Lyons, A., & Hill, A. O. (2022). Geosocial networking application use in men who have sex with men: The role of adult attachment. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00526-x

- Joel, S., Eastwick, P. W., Allison, C. J., Arriaga, X. B., Baker, Z. G., Bar-Kalifa, E., Bergeron, S., Birnbaum, G. E., Brock, R. L., Brumbaugh, C. C., Carmichael, C. L., Chen, S., Clarke, J., Cobb, R. J., Coolsen, M. K., Davis, J., de Jong, D. C., Debrot, A., DeHaas, E. C., … Wolf, S. (2020). Machine learning uncovers the most robust self-report predictors of relationship quality across 43 longitudinal couples studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(32), 19061–19071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917036117

- Kozee, H. B., Tylka, T. L., Augustus-Horvath, C. L., & Denchik, A. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00351.x

- Laming, G., Lyons, A., & Pepping, C. A. (2023). Long-term singlehood in sexual minority adults: The role of attachment and minority stress. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 20(1), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00628-0

- Lewis, T., Doyle, D. M., Barreto, M., & Jackson, D. (2021). Social relationship experiences of transgender people and their relational partners: A meta-synthesis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 282, 114143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114143

- Lim, G., Waling, A., Lyons, A., Pepping, C. A., Brooks, A., & Bourne, A. (2021). Trans and Gender-Diverse peoples’ experiences of crisis helpline services. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(3), 672–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13333

- MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202

- Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

- Marshall, E., Glazebrook, C., Robbins-Cherry, S., Nicholson, S., Thorne, N., & Arcelus, J. (2020). The quality and satisfaction of romantic relationships in transgender people: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(4), 373–390. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1765446

- Meier, S. C., & Labuski, C. M. (2013). The demographics of the transgender population. In International handbook on the demography of sexuality (pp. 289–327). Springer.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Motter, B. L., & Softas-Nall, L. (2021). Experiences of transgender couples navigating one partner’s transition: Love is gender blind. The Family Journal, 29(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720978537

- Nguyen, J., & Pepping, C. A. (2022). Prospective effects of internalized stigma on same-sex relationship satisfaction: The mediating role of depressive symptoms and couple conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000713

- Pachankis, J. E., Soulliard, Z. A., Seager Van Dyk, I., Layland, E. K., Clark, K. A., Levine, D. S., & Jackson, S. D. (2022). Training in LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized controlled trial across LGBTQ community centers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(7), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000745

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), e1–e14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305774

- Pepping, C. A., Cronin, T. J., Lyons, A., & Caldwell, J. G. (2018). The effects of mindfulness on sexual outcomes: The role of emotion regulation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1601–1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1127-x

- Pepping, C. A., Halford, W. K., Cronin, T. J., & Lyons, A. (2020). Couple relationship education for same-sex couples: A preliminary evaluation of rainbow CoupleCARE. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 19(3), 230–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2020.1746458

- Pepping, C. A., Lyons, A., Halford, W. K., Cronin, T. J., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). Couple interventions for same-sex couples: A consumer survey. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6(4), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000092

- Pepping, C. A., Lyons, A., & Morris, E. M. J. (2018). Affirmative LGBT psychotherapy: Outcomes of a therapist training protocol. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 55(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000149

- Pepping, C. A., MacDonald, G., & Davis, P. J. (2018). Toward a psychology of singlehood: An attachment-theory perspective on long-term singlehood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(5), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417752106

- Pew Research Center (2020). Nearly half of U.S. adults say dating has gotten harder for most people in the last 10 years. Pew Research Center.

- Pew Research Center (2022). Survey of U.S. adults. Pew Research Center.

- Platt, L. F., & Bolland, K. S. (2017). Trans* partner relationships: A qualitative exploration. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2016.1195713

- Powell, A., Scott, A. J., & Henry, N. (2020). Digital harassment and abuse: Experiences of sexuality and gender minority adults. European Journal of Criminology, 17(2), 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818788006

- Pulice-Farrow, L., Bravo, A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). “Your gender is valid”: Microaffirmations in the romantic relationships of transgender individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1565799

- Reed, L. A., Tolman, R. M., & Ward, L. M. (2017). Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 59(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.015

- Reuter, T. R., & Whitton, S. W. (2018). Adolescent dating violence among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. In Adolescent dating violence (pp. 215–231). Elsevier.

- Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., McCants, L. E., & Pascale-Hague, D. (2011). The positive aspects of a transgender self-identification. Psychology and Sexuality, 2(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2010.534490

- Riggs, D. W., von Doussa, H., & Power, J. (2018). Transgender people negotiating intimate relationships. In Sexuality, sexual and gender identities and intimacy research in social work and social care (pp. 86–100). Routledge.

- Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2000). Broad dispositions, broad aspirations: The intersection of personality traits and major life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(10), 1284–1296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200262009

- Robles, T. F., Slatcher, R. B., Trombello, J. M., & McGinn, M. M. (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031859

- Sevi, B. (2019). Brief report: Tinder users are risk takers and have low sexual disgust sensitivity. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(1), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-018-0170-8

- Simpson, D. M., Leonhardt, N. D., & Hawkins, A. J. (2018). Learning about love: A meta-analytic study of individually-oriented relationship education programs for adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(3), 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0725-1

- Smock, A. D., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., & Wohn, D. Y. (2011). Facebook as a toolkit: A uses and gratification approach to unbundling feature use. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(6), 2322–2329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.07.011

- Steinmetz, K. (2016). The inside story behind tinders new gender options. Time. https://time.com/4568225/tinder-gender-feature-transgendertime

- Sumter, S. R., Vandenbosch, L., & Ligtenberg, L. (2017). Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081