Abstract

Antibiotic resistance emergence has contributed to global public health threat rendering the choices of antibiotics limited. Antibiotics are universally packaged by manufacturers without taking into consideration scientific basis of therapy duration. The aim of this study is to evaluate the accordance of marketed antibiotics pack size in Lebanon with national and international guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and urinary tract infections (UTI) treatment. Moreover, it is to assess the possibility of self-medication with the leftover units among Lebanese population. The marketed antibiotics were cross-referenced with the Lebanese Society for Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (LSIDCM) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines to calculate the excess units and assessing the use of leftover units. The final list contained 34 antibiotics with 84 different pack sizes. Concerning CAP treatment, 11 packs matched LSIDCM and IDSA guidelines out of 26 and 30 combinations. Regarding LSIDCM and IDSA guidelines for UTI treatment, 45 and 18 packs result in extra units out of 63 and 26 combinations. Behaviors towards antibiotic use were significantly associated with occupation and economical status. Leftover users were more compliant with short-duration therapy with a significant ability to stop medication when symptoms improvement.

Introduction

The substantial rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is enhanced by the misuse of antibiotics as well as poor infection prevention and control (World Health Organization Citation2019). Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and urinary tract infection (UTI) are a common healthcare problem worldwide representing a notable impact on the country's economy with significant morbidity and mortality rates (Heidar et al. Citation2019). CAP is commonly described as an acute bacterial infection of the lung parenchyma acquired in the community and outside the healthcare facilities. The most common cause of CAP is bacterial in origin, mainly Streptococcus pneumonia, accompanied with or without clinical radiological evidence of lungs consolidation (Steel et al. Citation2013). Uncomplicated cystitis, the most common type of UTI, is a bladder infection while the uncomplicated pyelonephritis is an inflammation of the renal parenchyma. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), pyelonephritis is less common to occur; however, it is more serious than bladder infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2017). Recent studies indicate that UTIs are 14 times more frequent in women than in men (Wawrysiuk et al. Citation2019). In addition, up to 70% of females will suffer from a UTI during their lifetime, where 30% will have recurrent UTIs (Heidar et al. Citation2019).

The prevalence of bacterial infections results in a notable consumption of broad-spectrum antibiotics (Wawrysiuk et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the misuse and overuse of antibiotics are a serious problem leading to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. Thus, the resistance to antibiotics has developed antimicrobial stewardship program (AMS) (Rusic et al. Citation2019) where enhancement and rationalization use of antibiotics; reduction in the spread of antibiotic resistance (AMR); lifespan extension of existing antibiotics are some momentous set goals by AMS (Wang et al. Citation2019).

Furthermore, patient compliance to the treatment regimen is a confounding factor where non-compliance results in an inappropriate therapy without any leftover medicines since the patient does not consume multiple packs of drugs to complete the recommended antibiotic course. In contrast, a 100% patient compliance towards the treatment regimen may lead to leftover pills when several drug packs are consumed to complete the regime. In both cases, the inadequate therapy or expansion of leftover units in the community will enhance the chances of development of AMR (Mukherjee and Saha Citation2018).

Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the accordance of marketed antibiotics pack size in Lebanon with the treatment regimens and durations recommended in the national and international guidelines for prescribing antibiotics to treat CAP and UTI. Moreover, it is to assess the possibility of self-medication with the leftover units among Lebanese community.

Materials and methods

This is an observational study involving the prescribed and marketed antibiotics in the pharmacies in Lebanon that is specified for the Lebanese healthcare providers and Lebanese society, cross-referenced with the Lebanese Society for Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (LSIDCM) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for the treatment of CAP and UTI. The list of available antibiotics was limited to only oral dosage forms. On the other hand, one hundred eighty-four adults from Lebanese population were chosen randomly to participate in a self-administered questionnaire survey during the study period between September and December 2019 to assess Lebanese population practices toward antibiotic use to treat these infections.

Drugs eligibility

The Lebanese National Drug Index (LNDI) was searched for antibacterial for systemic use (https://www.moph.gov.lb/userfiles/files/HealthCareSystem/Pharmaceuticals/LNDI/LNDI-2015.pdf). The list of drugs, dosage forms, pack sizes, and drug strengths are registered at the Ministry of Public Health based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. The study was limited to oral usage forms while pediatric formulations that had not been pre-specified by the manufacturer (powder, granules for suspension, oral solutions) were excluded; and packs with 30 or more units were not considered in this study since such packs are usually used in health care centers and are not readily available in Lebanese pharmacy to be consumed by Lebanese population. The list was further limited to available drugs in Lebanon. Therefore, the availability of drugs included in this study was identified based on The National Social Security Fund (NSSF) updated data base (Drouby et al. Citation2015), since this study required evaluation of antibiotics regularly prescribed in the primary care setting or antibiotics that are self-administered by the Lebanese patients. Selected drugs were then merged based on their active substance, dosage and pack size, meaning that drugs with the same active substance, same strength, and same pack size were considered as a single result regardless of their trade-name. The final list was then cross-referenced with selected antimicrobial prescribing guidelines. The national guidelines were provided by the LSIDCM (Moghnieh et al. Citation2014; Husni et al. Citation2017), while the international guidelines were provided by the IDSA (Gupta et al. Citation2011; Metlay et al. Citation2019).

Cross-referencing with guidelines

Cross-referencing the list of marketed drugs with the guidelines was based mainly on the name of the drug, dosage strength, dosing regimen, and duration of treatment. It should be noted that some of the guidelines cover several indications and different treatment durations. Thus, all of which were taken into consideration. Additionally, if a guideline indicated a flexible interval of time as recommended for a specific drug, the treatment duration which results in the least extra units of the drug was considered. Recommendations for prophylaxis were excluded. If a specific drug dosage is recommended according to body weight, a maximum dose was considered.

Leftover calculation

Selected drugs were used based on the recommendations for each antibiotic such as doses (milligram or single/double strength), frequency and duration to calculate the minimal number of drug packs needed to complete the course of antibiotic indicated in the guidelines to treat CAP and UTI, and to calculate the excess units of antibiotics in case of 100% compliance to the treatment guidelines, thus the drugs that result in 0 leftover units were considered matched with guidelines.

Leftover consumption pattern

Lebanese population practices toward antibiotic use to treat CAP and UTI, including saving and sharing of leftover units, were assessed using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire has two sections:

Socio-demographic characteristics: participants’ gender, age, marital status, level of education, occupation, and monthly income

Behaviors toward the use of antibiotics to treat CAP and UTI among Lebanese population

The rest of the questions were used to assess the population awareness using ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ options.

Data analysis

Analysis of data was done using Statistical Package and Social Solutions (SPSS) version 24. Descriptive analysis and Chi-square test were carried out to determinate the association between the characteristics of the study participants and their behaviors toward the use of antimicrobials, by providing the number and percentage of each of the demographic variables as well as the statements about the knowledge and practices toward the antibiotics usage. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The participants were informed about the aim of the study and the objectives to be achieved. Moreover, they were informed that their participation would be anonymous and voluntary where their responses were held in a confidential manner. The study survey and ethics were accepted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) code: ECO-R-55 of Rayak University Hospital. The informed consent included general information on the conducted study, the aim of this study, participants’ selection, benefits and risks of taking part in the study, confidentiality of the provided information, and the right to withdraw from the study. Hence, it is not required to provide their reasons.

Results

Eligibility of drugs for inclusion in the study

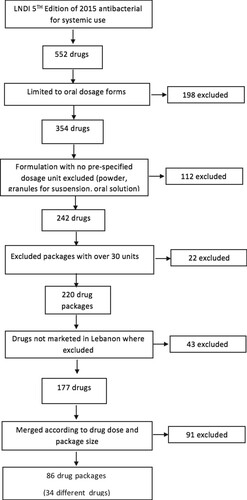

The LNDI was searched for antibacterial for systemic use, and the final result was a total of 552 drugs. One hundred and ninety-eight drugs were omitted from the total number since the oral dosage form was only included in this study (Figure ). Additionally, pediatric formulations that had not been pre-specified by the manufacturer (powder, granules for suspension, oral solutions) were excluded; and packs with 30 or more units were not considered, resulting in a total of 220 drugs out of 552. The list was further limited to marketed drugs in Lebanon, where only 177 were available in the pharmacies in Lebanon. Selected drugs were then merged based on their active substance, dosage and pack size where same active substance, same strength and same pack size were considered as a single result regardless to their trade-name which resulted in a list of 34 antibiotics with 86 antibiotics pack sizes.

Drugs cross-referencing with the national and international guidelines

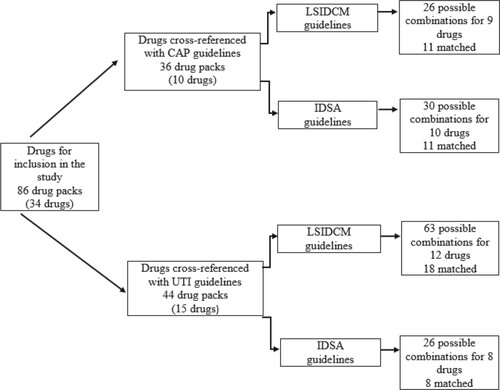

The final list of the included drug was cross-referenced with selected antimicrobial prescribing guidelines denoted for CAP and UTI; the national and international guidelines were provided by the LSIDCM and IDSA respectively. Out of 10 considered CAP treatment regimens, 9 were identified in the included LSIDCM guidelines where only amoxicillin with clavulanic did not match with the recommended guidelines. Moreover, LSIDCM guidelines for CAP matched 11 packs and mismatched 15 packs out of 26 possible combinations. Correspondingly, out of 10 considered CAP treatment regimens, all of which were identified in the included IDSA guidelines. There were 11 packs that matched similar to LSIDCM guidelines and 19 mismatching packs out of 30 possible combinations. Concerning the UTI and when considering LSIDCM, out of 15 suggested treatment regimens of both acute uncomplicated cystitis and acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, 12 were identified in the included LSIDCM guidelines. Out of 63 different combinations, there were 45 mismatched packs, and 18 packs were fully aligned with the national guidelines. On the other hand, out of 15 recommended treatment regimens of both acute uncomplicated cystitis and acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, 8 were identified in the included IDSA guidelines. Additionally, out of 26 different combinations, 8 packs matched IDSA guidelines on UTI treatment while 18 would inevitably result in extra units of antibiotics (Figure ).

Figure 2. Drugs cross-referencing with the Lebanese society for infectious diseases and clinical microbiology and infectious diseases society of America guidelines. CAP: community-acquired pneumonia, UTI: urinary tract infection, LSIDCM: Lebanese Society for Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, IDSA: Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines.

Compliance between marketed drugs pack sizes and treatment guidelines for CAP and UTI

When considering 100% compliance with the LSIDCM and IDSA guidelines for CAP, matched drugs were 15 × 625 mg amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, 6 × 250 mg and 3 × 500 mg azithromycin, 10 × 250 mg and 10 × 500 mg cefuroxime, 10 × 100 mg and 10 × 200 mg cefpodoxime, 14 × 50 mg and 28 × 50 mg doxycycline, 5 × 320 mg gemifloxacin, 5 × 750 mg levofloxacin and 5 × 400 mg moxifloxacin; all of the stated pack sizes resulted in 0 leftover. Significantly, two of each amoxicillin and doxycycline pack sizes left a highest number of leftover antibiotics; 10 and 14 units of 20 × 500 mg and 28 × 100 mg, respectively (Table ). In the LSIDCM treatment regimens of acute uncomplicated cystitis, out of 30 different combinations, 21 packs were mismatched, and 9 packs were fully aligned with cystitis guidelines. 14 × 1000 mg amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, 14 × 200 mg cefixime, 14 × 250 mg and 14 × 500 mg cefuroxime, 10 × 250 mg and 10 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin, 5 × 500 mg levofloxacin, 10 × 200 mg ofloxacin, and 5 × 600 mg prulifloxacin are the respective pack sizes with its corresponding antibiotics which resulted in 0 leftover units. Remarkably, cephalexin and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole are the only 2 drugs out of 12 that were not identified in the included cystitis guidelines, knowingly 12 × 1000 mg amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, 20 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin, 20 × 200 mg ofloxacin, 20 × 100 mg nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macrocrystal pack sizes with its corresponding antibiotic left 10 units of each consumed pack and considered to be the highest number of leftover among other listed pack sizes. Moreover, when considering the included drugs in IDSA guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis; out of 14 different combinations, 3 packs matched IDSA guidelines. Thus, 15 × 625 mg amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, 10 × 100 mg cefpodoxime proxetil and 10 × 300 mg cefdinir pack sizes with its corresponding antibiotic resulted in 0 leftover units while 11 would inevitably result in extra units of antibiotics. Markedly, out of 12 drugs, cefixime, cefuroxime, ofloxacin, and prulifloxacin were not identified in the included IDSA cystitis guidelines. Two of each consumed pack of 20 × 500 mg cephalexin and 20 × 100mg nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macrocrystal left 10 extra units are considered to be the highest amount of leftover among other listed pack sizes (Table ).

Table 1. Accordance of the selected drugs pack sizes with guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia.

Table 2. Accordance of the selected drugs pack sizes with guidelines for acute uncomplicated cystitis.

In acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis, out of 33 various combinations, 9 packages totally matched with recommended LSIDCM guidelines, same as cystitis; resulting in a total of 18 matched drugs out of 63 different combinations.

Cefpodoxime proxetil was the only antibiotic drug that was not included in LSIDCM acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis guidelines. Significantly, two of each 12 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin and 20 × 200 mg ofloxacin pack sizes with its corresponding antibiotic left 10 and 12 units of each consumed pack are to be the highest number of leftover among other listed pack sizes. However, matched pack sizes which with its corresponding antibiotic according to LSIDCM guideline are 14 × 1000 mg amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, 14 × 200 mg cefixime, 14 × 250 mg and 14 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin, 7 × 250 mg, 7 × 500 mg and 7 × 750 mg Levofloxacin, and 20 x (400 + 80 mg) trimerhoprim/sulfamethoxazole respectively. Unlikely, from 12 different combinations, 5 matched IDSA guidelines on acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis whereas 7 antibiotics drugs resulted in extra leftover units. 10 × 100 mg and 10 × 200 mg cefpodoxime proxetil, 14 × 250 mg and 14 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin, 5 × 750 mg levofloxacin are pack sizes that matched IDSA guidelines with the recommended treatment duration and resulted with 0 leftover units. Unlikely, 12 × 500 mg ciprofloxacin is one of the choice treatments in pyelonephritis which left 10 extra units, the highest number of leftover among the recommended drugs. Notably, drugs that were not included in the pyelonephritis IDSA guidelines are as follows: amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefdinir, cefixime, ofloxacin, and prulifloxacin (Table ).

Table 3. Accordance of the selected drugs pack sizes with guidelines for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis.

Characteristics of the study participants

A self-administered questionnaire was conducted over 184 adults supporting the assessment of the Lebanese population for their attitudes and practices toward antibiotic usage, mainly the possibility of self-medication with the leftover units. The majority of the participants were females (76%), and 35% were within the age group of 24–34 years. Almost half of the responders were married (55%), and 58% were employed. Among the responders, 76% were highly educated (university level); however, 49% had a monthly income of less than 500$ (Table ).

Table 4. Socio-demographic and working characteristics of the study participants.

Lebanese populations’ behaviors toward the use of antibiotics

The results showed that when having a CAP or UTI infection, 80% of this category consult a physician, whereas 62% may consult a pharmacist. A result of 61% responded neither antibiotic pack size affects their compliance with the treatment nor the price of antibiotic treatment (70%), with a majority of 77% that do not substitute the prescribed antibiotic with different available ones. Knowingly, 55% of participants responded that the duration of antibiotic course does not rely on how compliant they are to treatment. Furthermore, the majority (94%) of participants do not take a double dose in case they missed a pill on its time; likely, 55% of responders do not stop treatment once they felt better; thus 45% of responders end up with incomplete antibiotic course as recommended. Fortunately, 41% of participants neither share nor save leftover units for possible future use (Table ).

Table 5. Behaviors toward antibiotic use to treat community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infection among Lebanese population.

Association of antibiotics and leftover use with participants’ characteristics

The assessment of the association between the socio-demographic characteristics and behaviors toward antibiotic use to treat CAP and UTI among Lebanese population showed a significant correlation between occupation and economic status of study participants and behaviors regarding antibiotics use. Thus, a statistically significant difference was found concerning the consultation of a pharmacist in the case of CAP and UTI where employed responder (51.8%) tend to consult a pharmacist for an antibiotic prescription than unemployed participants (p-value = 0.04).

Regarding the practice of substitution of prescribed antibiotic by available ones, results showed no association with the education level since university-level participants (69.8%) agreed about the antibiotic substitution with no significant difference when comparing with the illiterates and school-level participants (p-value = 0.08). Concerning the economic status, results showed that a significant association between responders receiving an income < 500$ with treatment duration where they showed tendency in compliance when a shorter duration treatment was recommended (55.4%). Remarkably, participants between 25 and 34 years old are more likely to stop medication in case of symptoms improvement. On the other hand, no significant association was found between gender, marital status, and any of the use of antibiotic behaviors. Furthermore, the price of the prescribed antibiotic, the antibiotic pack size, and receiving a double dose when a dose is missed, were not significantly associated with any of the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants (Table ). Notably, an assessment of the association between leftover users in Lebanese community and the attitude of using antibiotics to treat CAP and UTI was performed. Results showed a statistically significant difference among study participants since 51.3% of leftover users were more compliant when a shorter duration treatment is recommended. Moreover, 58.7% tend to stop medication in case of symptoms improvement with p-value = 0.03 and 0.00, respectively. However, no correlation was found with any of other practices toward antibiotic use to treat CAP and UTI (Table ).

Table 6. Association between socio-demographic characteristics and behaviors toward antibiotic use to treat community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infection among Lebanese population.

Table 7. Association between leftover users and behaviors toward antibiotic use to treat community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infection among Lebanese population.

Discussion

The present study cross-referenced the antibiotic pack sizes available in Lebanon with the treatment guidelines of CAP and UTI; ended in a total of 29 matched cases out of 89 combinations with the LSIDCM guidelines. On the other hand, among 56 combinations packs matched with IDSA guidelines in 19 cases. Notably, this study assessed the accordance of antibiotic pack sizes with international and national guidelines; however, conformity with national guidelines is considered to be of considerable importance. This study involved antibiotics prescribed in primary healthcare sites which are similar to a study recently conducted in England where patients without comorbidity, usually consulted a physician for sore throat, acute cough and urinary tract infections, in addition to a study showing that respiratory and urinary tract infections are a common cause for antibiotics prescription (Rusic et al. Citation2019). Unfortunately, results showed that only 33% of marketed antibiotics pack sizes in Lebanon showed compliance with treatment guidelines. The finding of this study of low accordance of prescribed antibiotics for CAP and UTI infections with guidelines, was consistent with previous Australian studies that showed that only 4 combinations out of 32 most commonly prescribed antibiotics matched with treatment duration recommended by the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines (McGuire et al. Citation2015). In addition, the Croatian study supported the outcome result in this study since prescribed antibiotic pack sizes for sore throat and urinary tract infections matched with national guidelines in 30 cases out of total 104 combinations (Rusic et al. Citation2019). Moreover, this study showed that amoxicillin was not matched with national guidelines for 14-day treatments and leading from 2 to 4 extra units per regimen treatment. These findings are in agreement with previous studies, showing that in Croatia and Slovenia, amoxicillin was not matched with neither national nor European guidelines. Thus, broad-spectrum penicillin and beta-lactams should have a more safe profile (Seipel et al. Citation2019).

Hereafter, improper length of treatment and leftover extra units of antibiotics may influence antibiotic resistance and promote the increase in antimicrobial consumption (Rusic et al. Citation2019). Particularly, the world health organization (WHO) stated that the use of leftover units could increase the resistance to antibiotics (World Health Organization Citation2012). Thus, capsules distributed in the original prepacked form may result in excess or lack of antibiotic tablets resulting in either leftover units or short period of treatment than recommended (Mukherjee and Saha Citation2018). Since mismatch is commonly found, a high number of dismissed extra units might be shared in the community. Therefore, self-medication with the excess units of antibiotics may occur and leading to a shorter period of treatment than recommended. The results of the present study support the opinion that distributing the exact number of antibiotic tablets according to the recommended treatment regimen may have positive impact over distributing prepacked antibiotics by the manufacturer through pharmacies (Rusic et al. Citation2019). Moreover, researches recommended that medical references and other opinion contributors in the domain of AMR should integrate social media into their strategies of communication to increase the population awareness toward the use of antimicrobial drug and to spread antimicrobial stewardship concept (Seipel et al. Citation2019). Consequently, measures that endorse pharmacological pack of antibiotics should be controlled cooperatively by infectious disease physicians, health legislators, with representatives of the pharmaceutical industry to formulate strategies to reduce self-medication using leftover units (Rusic et al. Citation2019). On the other hand, self-administered questionnaire was conducted over 184 adults supporting the assessment of the possibility of self-medication with the leftover units among Lebanese population. Remarkably, a significant percentage of 62% of responders may consult a pharmacist for antibiotic prescribing, where this percentage was higher than a Lebanese study that showed 39.2% of responders consult a pharmacist relative to a percentage of 65.1% who consult physicians (Mouhieddine et al. Citation2015). On the other hand, Rusic et al. showed that a few pharmacists received specialist training, and there was only one specialist. Moreover, Rusic et al. stated that some of pharmacists are likely to dispense antimicrobial drug without a prescription which highlights the importance of physician in demonstrating patient needs of antibiotic treatment along with proper use and disposal (Bozic et al. Citation2021). This calls attention to a greater collaboration between physician and pharmacist by creating a digital networking of health care system to allow patients receiving antimicrobial and not pressuring pharmacists to dispense drugs without prescription.

Besides, studies showed the importance of physicians in the explanation of the prescribing decision according to bacterial or viral infections. As an effective doctor-patient, communication is needed to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use (Awad and Aboud Citation2015) since the unsure infection diagnosis is one of the main causes for prescribing an antimicrobial when not indicated. Therefore, for professionals and patients, the knowledge and awareness should be raised to change behaviors toward the prescription and the use of antimicrobials. On the other hand, the enforcement of laws and regulations is necessary to ensure the sustainability of behavioral change (Bozic et al. Citation2021). In this study, 45% of the study participants did not complete their antibiotic course as prescribed as most of them stopped treatment in case of symptoms improvement. This misconception in the antibiotic use might place the patient at risk of relapse with resistant pathogenic bacteria (Awad and Aboud Citation2015). Moreover, this result was close to a study showing that a large number of study participants (51.5%) may stop their course of antibiotics once they felt better (World Health Organization Citation2012). It is acknowledged that misuse of antibiotic has contributed to the emergence of antibiotics resistance which is an existing concern regarding CAP and UTI infections in Lebanon (Awad and Aboud Citation2015; Heidar et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, 59% of study participants tend to keep leftover antibiotics or share it with the surrounding and are unaware of its imports on healthcare. This result is close to a previous study where the antibiotic leftovers are not being controlled neither on individual nor on governmental level (Awad and Aboud Citation2015). In the present study, a significant association between misuse of antibiotics with occupation and economical status was detected. These findings were in correlation with a study in Jordan showing that a significant association between self-medication and the monthly income (Shehadeh et al. Citation2012). Concerning the age group, a high percentage of the young age group (18–24) stop medication in case of symptoms improvement. The effect of age is maybe related to their poor knowledge about antibiotic use. This was similar to a recent study showing that responders less than 21 years of age were more likely to stop taking the antibiotic before completing the course (Aljayyousi et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, there were a significant association between the leftover users and the attitude toward antibiotic use such as the stop of medication once symptoms improve. This finding was similar to a study in China showing that students keeping antibiotics at home were five times more likely to be involved in self-medication with antibiotics when ill (Wang et al. Citation2018). Thus, discussing compliance to antimicrobial treatment and waste management with the community should be introduced as a standard of patient care and education. Besides, the significant association between leftover users and the compliance to treatment when shorter duration is recommended among Lebanese population coincides with previous studies showing that distributing the exact number of tablets of antibiotics reduces the number of leftovers to use or share and has an encouraging influence on the environment and on compliance to therapy (Wang et al. Citation2018). Our findings are coincident with previous researches showing that the antibiotic extra units stored at home may be used in the future without prescription for shorter durations than recommended (Jukic et al. Citation2020). That contributes to antibiotic resistance emergence and endorses the conclusion that the management of AMR needs more attention.

Limitations

In this study, 100% patient compliance to the treatment recommended was assumed, but in practice patient adherence is often inconstant and poor. Hence, patient compliance is a confounding variable where a number of leftover antibiotics may be increased in real-life conditions. Another limitation is the limited number of responders for the self-administered questionnaire. Moreover, the percentage of females was higher than males and the effect of gender on misuse of antibiotics was not taken into consideration. Thus, based on the results of this study, it was only assumed that non-accordance of pack size to the guidelines may contribute to the emergence of AMR. Further researches are needed to indorse such assumptions.

Conclusion

The present study cross-referenced the antibiotic pack sizes available in Lebanon with the treatment guidelines of CAP and UTI ended in a total of 29 matched cases out of 89 combinations with the LSIDCM. On the other hand, among 56 combinations packs matched with IDSA guidelines in 19 cases. Leftover antibiotic units are a subsequent result of poor accordance of marketed antibiotic pack size with treatment guidelines which may lead to the emergence of resistant bacterial strains when used for self-medication by Lebanese population.

Acknowledgment

We would like to sincerely thank Dr Salim Moussa, Mrs Nadwa Hammouri, and all study participants for making this study possible.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in: https://figshare.com/s/6ff5fe083ac742a0b678

Disclosure statement

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aljayyousi GF, Abdel-Rahman ME, El-Heneidy A, Kurdi R, Faisal E. 2019. Public practices on antibiotic use: a cross-sectional study among Qatar University students and their family members. PloS one. 14(11).

- Awad AI, Aboud EA. 2015. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotic use among the public in Kuwait. PloS one. 10(2).

- Bozic J, Bukic J, Vilovic M, Tomicic M, Perisin AS, Leskur D, Modun D, Cohadzic T, Tomic S 2021. "AntImicrobial Resistance: Physicians' and Pharmacists' Perspective." . Microbial Drug Resistance. 5(27):670–677..

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic prescribing and use in Doctor’s Offices. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/for-hcp/outpatient-hcp/adult-treatment-rec.html.2019.

- Drouby F, Salameh P, Cherfan M, Saleh N. 2015. Evaluation of aspirin use for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases among Lebanese population. J Pharma Pharmacol. 3:569–590.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, Moran GJ, Nicolle LE, Raz R, Schaeffer AJ, Soper DE. 2011 Mar 1. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 52(5):e103–e120.

- Heidar NF, Degheili JA, Yacoubian AA, Khauli RB. 2019 Oct. Management of urinary tract infection in women: a practical approach for everyday practice. Urol Ann. 11(4):339.

- Husni R, Atoui R, Choucair J, Moghnieh R, Mokhbat J, Tabbarah Z, Bizri AE, Tayyar R, Jradeh M, Yared N, Al-Awar G. 2017 Dec. The Lebanese society of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology: guidelines for the treatment of urinary tract infections. LMJ. 103(5521):1–2.

- Jukic I, Rusic D, Vukovic J, Zivkovic PM, Bukic J, Leskur D, ., Perisin AS, Luksic M, Modun D 2020. Correlation of registered drug packs with Maastricht V/Florence consensus report and national treatment guidelines for management of helicobacter pylori infection. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 126(3):212–225.

- McGuire TM, Smith J, Del Mar C. 2015 Dec. The match between common antibiotics packaging and guidelines for their use in Australia. Aust Nz J Publ Heal. 39(6):569–572.

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, Cooley LA, Dean NC, Fine MJ, Flanders SA, Griffin MR. 2019 Oct 1. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American thoracic society and infectious diseases society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 200(7):e45–e67.

- Moghnieh R, Sakr NY, Kanj SS, Musharrafieh U, Husni R. 2014 Jan. The Lebanese society for infectious diseases and clinical microbiology (LSIDCM) guidelines for adult community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in Lebanon. LMJ. 103(1006):1–8.

- Mouhieddine TH, Olleik Z, Itani MM, Kawtharani S, Nassar H, Hassoun R, Houmani Z, El Zein Z, Fakih R, Mortada IK, Mohsen Y. 2015 Jan 1. Assessing the Lebanese population for their knowledge, attitudes and practices of antibiotic usage. J Infect Public Heal. 8(1):20–31.

- Mukherjee S, Saha N. 2018 Mar. Correlation of recommendations of treatment guidelines and frequently prescribed antibiotics: evaluation of their pharmaceutical pack size. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 122(3):317–321.

- Rusic D, Bozic J, Bukic J, Perisin AS, Leskur D, Modun D, Tomic S. 2019 Dec 1. Evaluation of accordance of antibiotics package size with recommended treatment duration of guidelines for sore throat and urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 8(1):30.

- Seipel MBA, Prohaska ES, Ruisinger JF, Melton BL. 2019. Patient knowledge and experiences with antibiotic use and delayed antibiotic prescribing in the outpatient setting. J Pharm Pract. 0897190019889427.

- Shehadeh M, Suaifan G, Darwish RM, Wazaify M, Zaru L, Alja’fari S. 2012 Apr 1. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding antibiotics use and misuse among adults in the community of Jordan. A Pilot Study. SPJ. 20(2):125–133.

- Steel HC, Cockeran R, Anderson R, Feldman C. 2013. Overview of community-acquired pneumonia and the role of inflammatory mechanisms in the immunopathogenesis of severe pneumococcal disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013:1–18.

- Wang H, Wang H, Yu X, Zhou H, Li B, Chen G, Ye Z, Wang Y, Cui X, Zheng Y, Zhao R. 2019 Aug 1. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship managed by clinical pharmacists on antibiotic use and drug resistance in a Chinese hospital, 2010–2016: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open. 9(8):e026072.

- Wang X, Lin L, Xuan Z, Li L, Zhou X. 2018 Apr. Keeping antibiotics at home promotes self-medication with antibiotics among Chinese University students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 15(4):687.

- Wawrysiuk S, Naber K, Rechberger T, Miotla P. 2019 Jul. Prevention and treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance—non-antibiotic approaches: a systemic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 26:1–8.

- World Health Organization. 2012. The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: options for action. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in health-care facilities in low-and middle-income countries: a WHO practical toolkit. 2019.