?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We aimed to explore the association of national COVID-19 data with the objective and subjective mental health proxies (i.e. location variance, self-reported sleep quality, level of recovery, perceived risk of infection) in team and staff members of five professional Austrian Football clubs. Data were conveniently collected during the implementation of a novel monitoring concept. The concept was designed to enable safe continuation of professional Football during the COVID-19 pandemic. These data were matched with Austrian COVID-19 data and smartphone collected location data. Multivariable linear regression models explored the association of COVID-19, defined as daily novel or active Austrian cases of COVID-19, with the mental health proxies. An increasing number of novel Austrian COVID-19 cases was significantly associated with deteriorating sleep quality (B 0.48, 95% CI 0.05; 1.00). An increasing number of active Austrian COVID-19 cases was significantly associated with an increase in perceived infection risk (B 0.04, 95% CI 0.00; 0.07) and location variance (B 0.28, 95% CI 0.06; 0.49). An increasing Austrian COVID-19 incidence is adversely associated with mental health in professional Footballers and staff members. During the ongoing pandemic, targeted mental care should be included in the daily routines of this population.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting not only physical health and societal structures, but also the mental health of individuals facing the burden of necessary alterations to daily life (Galea et al. Citation2020; Rajkumar Citation2020). For example, depression, anxiety and stress are linked to physical symptoms resembling a COVID-19 infection. This association is mediated by the need for adequate health information and the perceived individual impact of the pandemic (Wang et al. Citation2021). Quarantine and related isolation have influenced the mental wellbeing of individuals confronted with previous epidemics (Hawryluck et al. Citation2004; Brooks et al. Citation2020; Hossain et al. Citation2020). The duration of the current pandemic and preventive measures for disease-transmission (like social distancing, isolation, (non-compliance to) face mask use and quarantine) might result in decreased quality of life and economic prosperity and thereby contribute to an additional rise of the substantial burden of mental health disorders (Rehm and Shield Citation2019; Galea et al. Citation2020; Le et al. Citation2020; Tran et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2020). Moreover, daily news reports on infection and mortality rates may be perceived as threatening leading to anxiety and stress. Therefore, measures to enhance the early detection of mental health problems are essential. The monitoring of physical activity (PA) offers a subtle way for this purpose as reduced PA is associated with the occurrence of depressive symptoms (Mumba et al. Citation2020; Teychenne et al. Citation2020). Self-reported PA, activity trackers or interviewing by caretakers in the general population or in populations under medical supervision can aid in the subtle detection of mental health issues (van der Zee-Neuen et al.). This appears less useful for professional athletes, as levels of PA are influenced by training routines, competitions and recovery periods.

Professional athlete's (mental) health is generally well monitored by their accompanying (para-) medical staff. However, stigmatization and reluctance to discuss mental health problems might inhibit early detection of the latter (Gulliver et al. Citation2012; Souter et al. Citation2018). Yet, professional athletes might be at increased risk of developing such problems due to considerable stress in relation to both, their professional activities and the COVID-19 pandemic. This emphasizes the necessity of exploring possibilities for the monitoring of athlete's mental health, preferably unobtrusively. Emerging evidence suggests that individual mobility measured by smartphones may successfully detect adverse alterations in mental health (Canzian and Musolesi Citation2015; Saeb et al. Citation2015).

The resumption of professional sports during the COVID-19 pandemic required the close monitoring of athletes’ health to prevent disease transmission among team and staff members. In Austria, the monitoring of five professional Football clubs included smartphone-based geo-tracking, allowing for the estimation of risk exposure of footballers outside the training and competition facilities (van der Zee-Neuen et al. Citation2020). However, the geo-tracking data also yielded the opportunity of exploring potential mental health problems in participants. A previous exploratory study by Saeb et al. found that less location variance (obtained by means of smartphone mobility tracing) correlated with deteriorating mental health, specifically with depression in 40 subjects from the general population (Saeb et al. Citation2015). In another study, Saeb et al. confirmed that location variance correlated with depressive symptom severity in a sample consisting of 48 college students.

In the current study, we aimed to explore the association of novel and active Austrian COVID-19 cases with mental health proxies in a team and staff members of five professional Austrian football clubs captured by objective (i.e. location variance) or subjective (i.e. self-reported sleep quality, level of recovery and perceived risk of infection) indices. We hypothesized, that adverse alterations in mental health would be evident for the objective proxy but not for the subjective proxies (given the reluctance to reveal mental health problems) and, that increasing national COVID-19 cases would result in lower levels of location variance.

Methods

In the context of the scientific surveillance of the mandatory monitoring concept of the Austrian Football Association across four Premier League clubs and one Second League club (i.e. club A-club E), collection of geo-tracking and health diary data took place during a 12-week observation period. Players and staff members were included (van der Zee-Neuen et al. Citation2020).

Patient or public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Smartphone – app

The smartphone application (app) ‘WallpassTM’ (developed by the US-based company Electronic Caregiver) collected geo-tracking data. After installation on the primary mobile device of participants, the app collected motion-triggered Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) data points. In a second step, machine-learning algorithms assigned activities and locations to the GNSS data. The data was stored in flexible schemes of a noSQL database, in order to gather the multiple layers of information associated with each data point. Participants received unique identification-codes for the installation of the app. Club physiotherapists kept a list of codes and corresponding names. Researchers did not have access to the names corresponding with the identification-codes.

Parameters

In the current study, several parameters were included that were part of the health diaries of the original study, calculated based on the collected geo-tracking data or provided by the Austrian government.

Self-reported mental health proxies (i.e. subjective proxies)

Sleep quality

As impairments in sleep quality are linked to decreased mental health (João et al. Citation2018), this parameter was included as mental health proxy (10-point scale; 1=good sleep, quickly fell asleep slept through the night, 10=bad sleep, problems falling asleep, several night time wake-ups).

Level of recovery

An athlete's recovery level is associated with alterations in mood (Kellmann et al. Citation2018) and was therefore installed as a proxy indicator for mental health (10-point scale; 1=energetic, cheerful, rested; 10=tired, unenthusiastic, exhausted).

Subjective risk of infection

The current perceived risk of infection through COVID-19 was used as an indicator for anxiety related to the pandemic (10-point scale; 1=calm, composed, unconcerned; 10=panicked, anxious, severe risk).

Supplementary file S0 provides an overview of the questions, scales and anchors used for the collection of data on each of the self-reported mental health proxies as well as the instructions for completion of the questions.

Mental health proxy measured through smartphone mobility tracing (i.e. objective proxy)

Location variance

Location variance describes participant mobility in terms of GNSS-location variance independent of type of location (i.e. variability in GNSS location). In the current study, this parameter was included as objective mental health proxy and calculated as suggested by Saeb et al (Citation2015). The first step in the calculation involved reversing geocoding (i.e. assignment of ZIP-codes to raw GNSS data). For this purpose, the free online services Photon API and BING API were used (Komoot; BING). Next, location variance was calculated while accounting for distribution skewness in location data across subjects by means of the logarithm of the sum of the statistical variances of latitude and longitude components of the daily location data.

Austrian COVID-19 data

The Austrian National Public Health Institute (Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, GÖG) is continuously monitoring the occurrence of Austrian COVID-19 cases (Platform C-D Citation2020). For the current investigation, they provided access to the anonymized database of the electronic epidemiological reporting system (EMS). The database offered case-specific information on the date of diagnosis, (potential) date of death, (potential) date of recovery from COVID-19 and geographical region of occurrence in terms of 33 local administrative districts listed in supplementary Table S1. The daily number of Austrian COVID-19 cases was determined by means of date aggregation. Two parameters were then computed based on the aggregated data: (1) number of novel Austrian COVID-19 cases per day and (2) total number of active Austrian COVID-19 infections per day.

Additional parameters for adjustment

COVID-19 case in one Football-club

In one of the participating Football clubs, a COVID-19 case occurred during the observation period. The COVID-19 case was not part of the monitored sample, but an employee working in club administration. Due to inter-club co-operation, this individual had contact with two of the five teams in the present study.

As the occurrence of a case in proximity to participants might affect the association of mental health and COVID-19, we constructed a variable for adjustment comprising three categories:

(1) All clubs without known COVID-19 incidence in their proximity (not in proximity of case)

(2) Clubs in proximity of COVID-19 case before occurrence (clubs before COVID-19 case)

(3) Clubs in proximity of COVID-19 case after occurrence (clubs after COVID-19 case)

Study participants in category 3 experienced a change in their daily training routine due to quarantine guidelines being implemented. Hence, we consider this change in the daily life of the study participants as additional parameter.

Team status

Individuals participating in the study were either players or staff members of the participating clubs. To account for potential differences in the mental health proxies attributable to being part of any of these two groups, the binary variable team status was computed.

Game day

Existing evidence suggests that competitions in professional athletes are related to increased levels of anxiety and stress (Souza et al. Citation2019). In addition, game days inevitably participants’ movement due to travel to and from competition. Therefore, a variable differentiating between game and no-game days during the observation period was computed.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using R 4.0.3 (Team Citation2020). Analyses were restricted to complete data only. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data

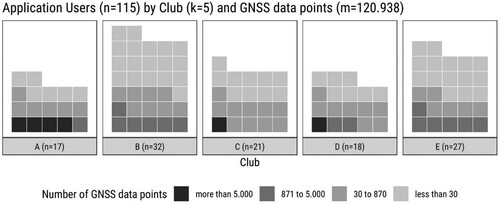

The players and staff of five clubs reported 120,938 GNSS data points via the smartphone app from 17 June to 31 July 2020. Theoretically, 225 players and staff members were supposed to participate but only 115 unique user ids were recorded by the app. The data provided by each of the 115 users differed significantly leading to a highly skewed distribution of GNSS data points per user (Figure ). Supplementary Figure S1 provides a more detailed illustration of the distribution.

Figure 1. Distribution of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) data points in participating clubs. Note: As our analysis required data aggregation, a minimum of 30 GNSS data points a day would be the bare minimum to be considered in the later analysis. And with 29 days between first data collection (17 June) and final competition in the premier leagues season (15 July) a full dataset with 30 GNSS data points a day would require 870 GNSS data points in total.

As Austrian COVID-19 data were provided only on the local administrative districts, GNSS location data were matched with these care regions based on the previously identified postcodes. Next, self-reported mental health proxy indicators were included in the same data set based on participant-specific identification codes and reported day. The 120,938 GNSS data points were aggregated by unique user id and date resulting in a user-day-dataset with 508 cases (Supplementary Figure S1). Cases aggregated with less than 30 GNSS data points were excluded leaving 297 user-day-data points left for the analysis. All results rest on these 297 user-day data points from 57 app users.

Descriptive statistics

All variables included in the current study were described for user-day cases according to their metric properties (i.e. means, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum for continuous data and frequencies (n) and percentages (%) for categorical data). A single user-day case is the unique combination of user and day during the observation period (e.g. a single user day-case for new Austrian COVID-19 cases is the mean of the official number of new cases in the region visited by the included users on a specific day weighted for the number of data points per visited region).

Association of novel and active Austrian COVID-19 cases with mental health proxies

First, bivariate correlations (Pearson's r) explored the association of novel and total Austrian COVID-19 cases with the objective and subjective mental health proxies.

Subsequently, multivariable linear regression models with ordinary least square estimation explored the association of the COVID-19 variables with the objective (location variance) and subjective mental health proxies (sleep quality, level of recovery, perceived risk of infection), while adjusting for game day, team status and the occurrence of a COVID-19 case in one participating club.

Results

The sample for further analyses consisted of 297 cases. The sample consisted of 205 cases from staff members (69%) and 92 cases from players (31%). Table provides an overview of user-day cases for the total sample and each participating club.

Table 1. Characteristics of user-day cases (n) for the total sample and each participating club.

Association of novel and active Austrian COVID-19 cases with mental health parameters

Location variance correlated with both Austrian COVID-19 case variables. Furthermore, novel Austrian COVID-19 cases per day were significantly associated with sleep quality, while the total number of active Austrian COVID-19 cases showed a relationship with the level of recovery instead. All three subjective indicators related to each other (Table ). Supplementary Figure S2 provides a more detailed illustration of correlation.

Table 2. Correlation matrix of metric parameters of user-day-cases pooled across clubs.

Multivariable linear regression models exploring the association of novel Austrian COVID-19 infections with mental health proxies showed a significant association of novel Austrian COVID-19 cases per day with deterioration of sleep quality (B 0.48, 95% CI 0.05; 1.00) but with none of the other subjective and objective mental health proxies. When compared to staff members, players had a significantly lower perceived risk of infection (B −0.26, 95% CI −0.52; −0.00) and a significantly higher variance in their location (B 5.17, 95%CI 2.04; 8.29). Moreover, the perceived risk of infection was significantly higher after a COVID-19 case occurred in one of the clubs (B 0.52, 95% CI 0.06; 0.98). The model including the perceived risk of infection as outcome variable showed the best fit (adjusted R2 = 0.079, F = 2.440, df = 5, p = 0.041) (Table ).

Table 3. Multivariable linear regression models exploring the association of novel COVID-19 cases per day with mental health proxies (unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals).

In the models exploring the association of the total number of active Austrian COVID-19 infections with the mental health proxies, an increasing number of active Austrian COVID-19 cases was significantly associated with an increased perceived risk of infection (B 0.04, 95% CI 0.00; 0.07) and surprisingly with an increase in the location variance (B 0.28, 95% CI 0.06; 0.49). As in the models including novel Austrian COVID-19 infections as the main independent variable of interest, players had a significantly lower perceived risk of infection when compared to staff members and a significantly higher variance in their location. Moreover, the model including the perceived risk of infection as an outcome variable showed the best fit (adjusted R2 = 0.112, F = 3.126, df = 5, p = 0.013) (Table ).

Table 4. Multivariable linear regression models exploring the association of total active COVID-19 cases per day with mental health proxies (unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the association of COVID-19 occurrence with subjective and objective proxies for mental health in elite Footballers and their professional surroundings. Contrary to our hypotheses, adverse alterations in mental health became particularly evident for the subjective mental health proxies. Moreover, we found that an increasing number of novel cases of Austrian COVID-19 was significantly associated with worse sleep quality and that an increasing total of active Austrian COVID-19 cases was significantly associated with a higher perceived risk of infection and with a higher variance in location. The latter is particularly surprising, as we assumed that, with increasing Austrian COVID-19 cases, the location variance would decrease due to risk avoidance behaviour (Bruns et al. Citation2020). This finding might be attributable to the low incidence of COVID-19 in Austria during the observation period (Le et al. Citation2009; AGES Citation2020) but may also suggest that location variance is not suited to capture mental health alterations due to COVID-19. In this line, the perceived risk of infection did in fact increase but no significant correlation of this variable with location variance was found, indicating the independence of these constructs.

The adverse association of COVID-19 with sleep quality is in line with previous research findings in various populations (i.e. general population, professional athletes, workers and psychiatric patients) (Fu et al. Citation2020; Gupta et al. Citation2020; Hao et al. Citation2020; Tan et al. Citation2020; Tayech et al. Citation2020). In an international study across 49 countries 40% of participants reported worse sleep quality than before the pandemic and the consumption of sleeping pills increased by 20% when compared to the pre-pandemic situation. According to the study, the deterioration in sleep was among others attributable to quarantine measures and the adverse impact of the pandemic on participant's livelihood (Mandelkorn et al. Citation2020). Approaches like cognitive behaviour therapy show promising results in the improvement of deteriorated sleep quality during the pandemic through arousal reduction strategies, restriction of time spent in bed during periods of lock-down and through support of the stability of the circadian regulatory system (Zhang and Ho Citation2017; Ho et al. Citation2020; Simpson and Manber Citation2020; Soh et al. Citation2020). In the current study, the perceived risk of infection was included as a proxy for anxiety. Sjöberg defined perceived risk as an individuals’ psychological evaluation of the probability and consequences of an adverse outcome (Sjöberg Citation2002). Our analyses suggest that an increasing total of active Austrian COVID-19 cases is associated with higher levels of anxiety confirming the assumptions of Reardon et al who stated that the COVID-19 pandemic could cause anxiety in elite athletes (Reardon et al. Citation2020). It should be considered that professional Football players might be less inclined to report potential mental health problems due to the potential impact of their reporting on the team constellation determined by trainers and team managers. The level of anxiety might in fact be even higher than in our analyses. Addressing anxiety in athletes is particularly relevant as their livelihood depends on their ability to perform in training and competition. Other factors than the COVID-19 pandemic are driving anxiety in elite athletes, for example career dissatisfaction, fear of musculoskeletal injury or increasing age (Rice et al. Citation2019).

Therefore, those responsible for the psychological care of athletes should be aware of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic as it adds to the existing anxiety burden. However, in the current study, the increasing burden of anxiety during the ongoing pandemic was even more pronounced in staff members than in Football players. In the context of the pandemic, a potential explanation for their higher perceived infection risk might be that they are assumed to be older and that an increasing age is associated with increased COVID-19 symptom severity (Hao et al. Citation2020). Although no data on the study subjects age was available, it should be noted that their need for mental wellbeing deserves specific attention as well. In our study, we employed two distinct indicators of Austrian COVID-19 cases (i.e. novel and active Austrian COVID-19 cases). Surprisingly, we found that associations of these two indicators with the different mental health proxies were not comparable. Novel cases of Austrian COVID-19 were only significantly associated with worse sleep quality, while active cases of Austrian COVID-19 were significantly associated with increasing levels of perceived infection risk and location variance. Potential explanations for this phenomenon might be found in the media coverage on both concepts during the observation period. During the latter, the number of novel cases per day was small and remained largely unaltered (AGES Citation2020). Therefore, it seems plausible that no alterations are found in the levels of anxiety and location variance. Media coverage on novel COVID-19 cases might have led to a higher level of cogitation on the implications of this information resulting in disturbances in sleep quality. The number of active cases also included cases that were diagnosed prior to the observation period and were naturally higher than the number of novel cases. Consequently, the confrontation with such numbers might have caused enhanced feelings of anxiety.

Strengths and limitations

This study offered the unique possibility to study various mental health outcomes in a population of elite Footballers providing insight into their response to an increasing number of COVID-19 cases. The combination of data from multiple sources (i.e. governmental data on active and novel cases of COVID-19 in Austria, GNSS-data from a specifically designed app and self-reported mental health data) in the statistical analyses of our paper emphasize the individuality and quality of the current study. However, several limitations should be addressed. The data collected by the smartphone app were fragmented and sampling unbalanced (i.e. largest proportion of observations was affiliated with club E) leading to potential misinterpretation of the association of COVID-19 with location variance. The lack of data density may be attributable to participants reluctance to continuous submission of location data (van der Zee-Neuen et al. Citation2020). We aimed to mitigate this issue by aggregating the data, relying on solid statistical procedures and cautiously drawn conclusions. Future research could shed light on the reasons for participation reluctance and other potential challenges in the handling of the current pandemic, for example by surveying attitudes and perceptions regarding methods of data collection and the administration of COVID-19 vaccines.

The current study collected data during a rather stable period in the COVID-19 pandemic (AGES Citation2020). It is likely, that more variance in the mental health proxies would have been observed (1) in a period with more rapidly growing COVID-19 incidence or (2) when employing instruments that are more sensitive to small changes in mental health. Yet, it should be noted that the original study (from which the data for the current analyses were derived) did not specifically address mental health changes but rather focused on the implementation of a sound monitoring concept for safe resumption of professional Football. On this line, we aimed for ideal processing of the data at hand. The current study yielded interesting findings that deserve further exploration and may aid in the monitoring and handling of mental health in professional sports during the ongoing and potential future pandemics.

Conclusion

An increasing number of COVID-19 cases is adversely associated with mental health in professional Footballers and staff members of their team. This emphasizes the need for additional, targeted mental care during the pandemic, which can be included in the daily routines of this population.

Declarations/statements

Authors contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Alexander Seymer, Antje van der Zee-Neuen and Dagmar Schaffler-Schaden. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Antje van der Zee-Neuen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study presents analyses of data collected in the context of the scientific surveillance of five selected, professional Austrian Football clubs.

The study protocol and all procedures were approved by the Austrian ethics committee of Salzburg county (statement of the ethics board of Salzburg county, ID 415-EP/73/820-2020). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. Participants were informed about the study purpose and procedures in writing and were additionally informed in person prior to providing their written consent.

Guidelines and regulations

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Austrian ethics committee of Salzburg county and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (619.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the tremendous effort of Melina Mokry who was of great assistance in the organization of the study, the collection of data and the communication with all stakeholders. Moreover, we would like to thank our external raters, Anna Schmuttermair, Anna-Maria Wörndle and Markus Huthöfer, for the on-site assistance in participating clubs, thereby enabling smooth collection of data. We also would like to express our appreciation for the great work of Michael Lyon and Isiah Fielder for their continuous efforts and patience when developing the smartphone app according to our needs and wishes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4714181.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AGES. 2020. Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety, Epidemiological Parameters of the COVID-19 Pandemic (Epidemiologische Parameter des COVID19 Ausbruchs), Updates June–July.

- BING. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/bingmaps/rest-services/.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. 2020. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 395(10227):912–920.

- Bruns DP, Kraguljac NV, Bruns TR. 2020. COVID-19: facts, cultural considerations, and risk of stigmatization. J Transcult Nurs. 31(4):326–332.

- Canzian L, Musolesi M. 2015. Trajectories of depression: unobtrusive monitoring of depressive states by means of smartphone mobility traces analysis. Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing. p. 1293–304.

- Fu W, Wang C, Zou L, Guo Y, Lu Z, Yan S, Mao J. 2020. Psychological health, sleep quality, and coping styles to stress facing the COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Transl Psychiatry. 10(1):225.

- Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. 2020. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Int Med. 180(6):817–818.

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. 2012. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 12:157.

- Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, Krishnan V, Tripathi A, Subramanyam A, Nischal A, Hussain A, Mehra A, Ambekar A, et al. 2020. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J Psychiatry. 62(4):370–378.

- Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, Jiang X, McIntyre RS, et al. 2020. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 87:100–106.

- Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. 2004. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 10(7):1206–1212.

- Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. 2020. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 49(3):155–160.

- Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. 2020. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health. 42:e2020038.

- João KADR, Jesus SN, Carmo C, Pinto P. 2018. The impact of sleep quality on the mental health of a non-clinical population. Sleep Med. 46:69–73.

- Kellmann M, Bertollo M, Bosquet L, Brink M, Coutts AJ, Duffield R, Erlacher D, Halson SL, Hecksteden A, Heidari J, et al. 2018. Recovery and performance in sport: consensus statement. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 13(2):240–245.

- Komoot P. https://photon.komoot.io.

- Le H, Schmidt FL, Putka DJ. 2009. The multifaceted nature of measurement artifacts and its implications for estimating construct-level relationships. Organ Res Methods. 12.1.1: 65–200.

- Le HT, Lai AJX, Sun J, Hoang MT, Vu LG, Pham HQ, Nguyen TH, Tran BX, Latkin CA, Le XTT, et al. 2020. Anxiety and depression among people under the nationwide partial lockdown in Vietnam. Front Public Health. 8:589359.

- Mandelkorn U, Genzer S, Choshen-Hillel S, Reiter J, Meira E, Cruz M, Hochner H, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D, Gileles-Hillel A. 2020. Escalation of sleep disturbances amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional international study. J Clin Sleep Med. 17(1):45–53.

- Mumba MN, Nacarrow AF, Cody S, Key BA, Wang H, Robb M, Jurczyk A, Ford C, Kelley MA, Allen RS. 2020. Intensity and type of physical activity predicts depression in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 25(4):664–671.

- Platform C-D. 2020. Austrian National Public Health Institute (Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, GÖG).

- Rajkumar RP. 2020. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiat. 52:102066.

- Reardon CL, Bindra A, Blauwet C, Budgett R, Campriani N, Currie A, Gouttebarge V, McDuff D, Mountjoy M, Purcell R, Putukian M, Rice S, Hainline B. 2020. Mental health management of elite athletes during COVID-19: a narrative review and recommendations. Br J Sports Med. 55:608–615.

- Rehm J, Shield KD. 2019. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 21(2):10.

- Rice SM, Gwyther K, Santesteban-Echarri O, Baron D, Gorczynski P, Gouttebarge V, Reardon CL, Hitchcock ME, Hainline B, et al. 2019. Determinants of anxiety in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 53(11):722–730.

- Saeb S, Zhang M, Karr CJ, Schueller SM, Corden ME, Kording KP, Mohr DC. 2015. Mobile phone sensor correlates of depressive symptom severity in daily-life behavior: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 17(7):e175.

- Simpson N, Manber R. 2020. Treating insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic: observations and perspectives from a behavioral sleep medicine clinic. Behav Sleep Med. 18(4):573–575.

- Sjöberg L. 2002. Factors in risk perception. Risk Anal. 20(1):1–12.

- Soh HL, Ho RC, Ho CS, Tam WW. 2020. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. 75:315–325.

- Souter G, Lewis R, Men SL. 2018. Mental health and elite sport: a narrative review. Sports Med Open. 4(1):57.

- Souza RA, Beltran OAB, Zapata DM, Silva E, Freitas WZ, Junior RV, da Silva FF, Higino WP. 2019. Heart rate variability, salivary cortisol and competitive state anxiety responses during pre-competition and pre-training moments. Biol Sport. 36(1):39–46.

- Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, et al. 2020. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 87:84–92.

- Tayech A, Mejri MA, Makhlouf I, Mathlouthi A, Behm DG, Chaouachi A. 2020. Second wave of COVID-19 Global pandemic and athletes’ confinement: recommendations to better manage and optimize the modified lifestyle. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(22):8385.

- Team RC. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Teychenne M, White RL, Richards J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Bennie JA. 2020. Do we need physical activity guidelines for mental health: what does the evidence tell us? Ment Health Phys Act. 18:100315.

- Tran BX, Nguyen HT, Le HT, Latkin CA, Pham HQ, Vu LG, Le XTT, Nguyen TT, Pham QT, Ta NTK, et al. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the Vietnamese during the national social distancing. Front Psychol. 11:565153.

- van der Zee-Neuen A, Schaffler-Schaden D, Herfert J, Brien JO, Johansson T, Kutschar P, Seymer A, Ludwig S, Stöggl T, Keeley D, Resch H, Osterbrink J, Flamm M. 2020. Team contact sports in times of the COVID-19 pandemic- a scientific concept for the Austrian football league. medRxiv.

- van der Zee-Neuen A, Wirth W, Hoesl K, Osterbrink J, Eckstein F. 2019.The association of physical activity and depression in patients with, or at risk of, osteoarthritis is captured equally well by patient reported outcomes (PROs) and accelerometer measurements- analyses of data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 49(3): 325–330.

- Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Grabowski D, Pan R, Adamus K, Wan X, Hetnał M, Tan Y, Olszewska-Guizzo A, Xu L, et al. 2020. The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Front Psychiatry. 11:569981.

- Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Tee ML, Núñez MIL, Tripp C, Fardin MA, Habib HA, Tran BX, Adamus K, Anlacan J, García ME, et al. 2021. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci Rep. 11(1):6481.

- Zhang MW, Ho RC. 2017. Moodle: The cost effective solution for internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. Technol Health Care. 25(1):163–165.