Abstract

Depression, anxiety and somatization are the most common mental disorders in primary health care. Previous studies have shown that depression, anxiety and somatization are highly comorbid. The study population included 939 depression patients from outpatient and inpatient departments. All patients were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic Symptom Severity Scale (PHQ-15). We estimated the network and centrality of depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms in patients with depression. Feeling tired or having little energy and feeling down, hopeless were the central symptoms of depression in each network. Low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom. Education was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation. The importance of feeling down, hopeless and fatigue as central symptoms of each network is emphasized. Fatigue symptoms are particularly common in people with depression, and their influence at the center of the depression network may be underestimated. In addition, low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom for each network and education was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation.

Highlights

Depression, anxiety and somatization are the most common mental disorders in primary health care.

This study is the first to explore the network and centrality of depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms in Chinese patients with depressive disorders.

Fatigue and feeling down, hopeless were the central symptoms of depression.

Low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom for each network and education was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation.

1. Introduction

Somatization is defined as the tendency to experience and communicate somatic distress and symptoms unaccounted for by pathological findings to attribute them to physical illness and to seek medical help for them (Lipowski Citation1988). Somatization is especially prevalent in people who have mental health problems, such as depressive and anxiety disorders (Bekhuis et al. Citation2015). There are significant cultural differences in somatic symptoms, with Asian depression patients, such as those in China and Korea, more likely to express somatic symptoms than Westerners. Studies have shown that somatic chief complaints may be an appropriate way to express psychological distress and seek help. The emphasis on somatic symptoms can be understood as a result of specific local culture influences, as they are considered a more culturally normative way to communicate or experience pain (Ryder et al. Citation2008; Zhou et al. Citation2015; Kim et al. Citation2019). In addition, somatization is a risk factor for incident depression and anxiety (Dijkstra-Kersten et al. Citation2015).

Depression, anxiety and somatization are the most common mental disorders in primary health care (Toft et al. Citation2005). There is a close relationship between these diseases. Previous studies have shown that depression, anxiety and somatization are highly comorbid (Rodriguez et al. Citation2004; Bener et al. Citation2013). The comorbidity rate between depression and generalized anxiety is as high as 40–60% (Henningsen et al. Citation2003; Hettema Citation2008). Half of the depressed patients reported multiple unexplained somatic symptoms (Simon et al. Citation1999). At least one-third of people with somatoform disorders have comorbid anxiety and depression (Henningsen et al. Citation2003). There is a strong link between anxiety, depression and somatization in both men and women (Haug et al. Citation2004), and studies of the strongly correlated symptoms are very important to deepen our understanding of the interaction between symptoms.

After many years of research, no central disease mechanism or pathogenic pathway of mental disorders has been found. Some studies have proposed such a hypothesis: there is no central disease mechanism of mental disorders, because psychiatric symptoms are caused by each other rather than by common causes (Borsboom Citation2008; Cramer et al. Citation2010).

A number of studies have used network analysis to explore causal relationships between individual symptoms (Robinaugh et al. Citation2020). In this approach, disease is caused by causal interactions between symptoms (e.g. worry → insomnia → fatigue). Causal relationships between symptoms such as bridging symptoms (symptoms of both diseases) constitute pathways that can link different diseases (Borsboom and Cramer Citation2013; McNally Citation2016). Symptoms are represented as nodes and the associations between them as edges. Symptoms of multiple diagnoses or domains can be combined into one network structure, which, consequently, offers the opportunity to study the patterns in which these symptoms co-occur (Borsboom and Cramer Citation2013). If the mental disorders are understood as symptom networks, by identifying the symptoms and structures of the networks and combining treatment intervention with network structures, the most effective combination of treatment strategies can be found to effectively guide the network to transition to a healthy state (Borsboom Citation2017).

The network approach opens up a number of new research issues, such as estimating symptoms from depression questionnaires, in which the network can objectively assess the centrality of symptoms (Opsahl et al. Citation2010; Bringmann et al. Citation2019; Park and Kim Citation2020). Central symptoms in the network may have a greater impact on the system than peripheral symptoms. These central symptoms are thought to contribute to the rapid activation of related symptoms within the network and may be targets for treatment. Studying these central symptoms may provide clues for further clinical research (Borsboom and Cramer Citation2013; Fried et al. Citation2016). There have been some studies on depression network analysis (Contreras et al. Citation2019). For example, comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression (Fried et al. Citation2016; Kendler et al. Citation2018); studying the dynamic network of depressive symptoms based on the BDI-II questionnaire (Bringmann et al. Citation2015); and studying the centrality of depressive and anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder (Park and Kim Citation2020). The network structure and central symptoms vary in different studies, which may be caused by different populations, assessment methods and analysis methods used in the studies (Robinaugh et al. Citation2020). This study is the first to explore the network and centrality of depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms in Chinese patients with depressive disorders.

In the current study, we first examined a psychopathological network consisting of depressive symptoms to determine which symptoms were most central to the psychopathological network of depression (i.e. the identification of central symptoms). Next, we examined which anxiety and somatic symptoms were most associated with depressive symptoms. The study had two main purposes: (a) to determine which symptoms of depression are central to the disease and (b) to test which anxiety and somatic symptoms are most closely related to the symptoms of depression. We hypothesized that the depressive symptoms of low mood and decreased interest are more important to the depression network than other symptoms. We additionally assessed the effect of number of depressive episodes, number of chronic diseases, gender and education on the network, which were added to the network as covariates.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study was based on data from the ‘Early Warning System and Comprehensive Intervention for Depression’ (ESCID) project, which collected data from 15 hospitals in China from April 2019 to April 2021. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (WDRY2020-K191). The target populations were outpatient and inpatient individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD). The inclusion criteria were as follows: being 18–55 years old; having a junior high school education or higher; and informed consent completed for participation and follow-up. Patients were all diagnosed by two experienced psychiatrists and met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders Citation2013). All patients were also screened with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al. Citation1998).

2.2. Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a self-assessment questionnaire for patients with depression that consists of nine depression criteria from the DSM-IV (Spitzer et al. Citation1999; Kroenke et al. Citation2001). Anxiety and somatic symptoms were assessed by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al. Citation2006) and the 15-item Patient Health Questionnaire somatic symptom severity scale (PHQ-15) (Kroenke et al. Citation2002), respectively. Both scales are self-report measures. Table shows the items of the three scales.

Table 1. The content and mean score of each item of PHQ-9, GAD-7, and PHQ-15 scales.

2.3. Network analyses

In a centrality analysis, one can determine the relative importance or influence of a symptom in the network. There are three common measures of node centrality: betweenness, closeness, and strength. A node’s betweenness is the number of times that a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes. A node’s closeness is the reciprocal of the sum of the shortest distances from all nodes to this node. A node’s strength denotes the sum of the weights (e.g. correlation coefficients) of the edges connected to a node. We introduced the expected influence (EI) to assess the nature and strength of a node’s cumulative influence within the network (Robinaugh et al. Citation2016). In each network, the EI values of all items were sorted, and the first three items of each scale were taken as the central symptoms.

The partial correlation network analysis method is used to identify the causal relationship between symptoms (Mcnally Citation2012). After adjusting for the influence of all other symptoms in the network, the edges that still exist in the network are reasonable candidates for causal calculation (McNally Citation2016). In order to better identify the highly inflial nodes in the mental disorder network, we used different colors to distinguish between positive and negative edges. Green was for positive and red was for negative edges. Network models were constructed and analyzed in R (Version 3.6.3) using the qgraph package (Version 1.6.5) (Epskamp et al. Citation2012). We used the glasso function in qgraph to reduce the small correlation to zero to create a more parsimonious network. Finally, we tested the stability of these networks using the bootnet package in R (Epskamp et al. Citation2018).

3. Result

3.1. Demographic characteristics

The study population (n = 939) included 232 males (24.7%) and 707 females (75.2%). Most of the depressed patients were unmarried (92.1%), were college students (76.9%), and had an undergraduate education (83.4%). The mean age of patients was 22.4 years (Table ). The mean (SD) scores of PHQ-9 for depression, GAD-7 for anxiety, and PHQ-15 for somatic symptom were 15.8 (6.5), 10.3 (5.6), and 12.6 (5.9), respectively. Cronbach’s α coefficients for PHQ-9, GAD-7 and PHQ-15 were 0.89, 0.91, and 0.86, respectively (Table S1). The mean score and standard deviation of each item were shown in Table .

Table 2. Characteristics of the patients.

3.2. Depression network

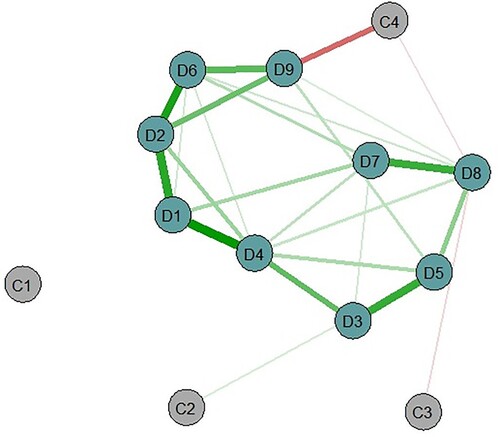

Feeling tired or having little energy (D4), feeling down, hopeless (D2) and guilt (D6) were at the center of the model, suggesting that these symptoms may be central to depression psychopathology (Figure , Figure S1 and Table S2). There were several depressive symptoms associated with each other, such as low interest or pleasure (feeling tired or having little energy; D1-D4), feeling down, hopeless (guilt; D2-D6), and low interest or pleasure (feeling down, hopeless, D1-D2), but they were located at the periphery of the network (Table S3). It was noteworthy that the education (C4) was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation (D9) (Figure ).

3.3. Depression and associated anxiety network

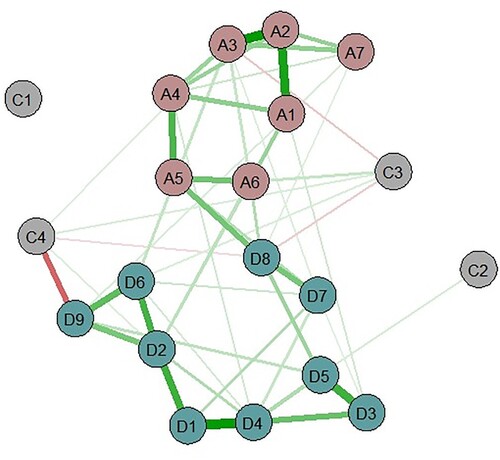

The anxiety symptoms with the highest centrality were uncontrollable worry (A2), worry about different things (A3) and trouble relaxing (A4). The depressive symptoms with the highest centrality were feeling down, hopeless (D2), feeling tired or having little energy (D4) and guilt (D6) (Figure , Figure S2 and Table S4). There were several groups of depressive and anxiety symptoms that were linked together. The anxiety symptoms closest to the depressive symptoms were as follows (depressive symptoms in parentheses): restlessness (moving slowly/restless; A5-D8); restlessness (trouble concentrating; A5-D7); irritability (moving slowly/restless; A6-D8); nervousness, anxiousness, feeling on edge (feeling down, hopeless; A1-D2); and irritability (feeling down, hopeless; A6-D2) (Table S5).

3.4. Depression and associated somatization network

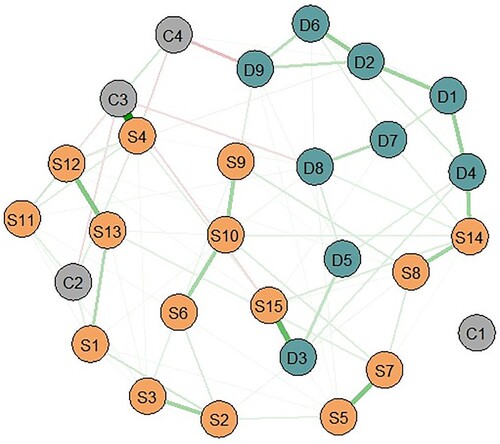

The somatic symptoms with the highest centrality were menstruation (S4), feeling tired (S14) and shortness of breath (S10). Feeling tired or having little energy (D4), feeling down, hopeless (D2) and trouble sleeping (D3) were the depressive symptoms with the highest centrality (Figure , Figure S3 and Table S6). Several groups of depressive and somatic symptoms were linked together. The somatic symptoms closest to the depressive symptoms were as follows (depressive symptoms in parentheses): trouble sleeping (feeling tired or having little energy; S15-D3), feeling tired (feeling tired or having little energy; S14-D4), shortness of breath (suicidal thoughts; S10-D9), and feeling tired (trouble concentrating; S14-D7) (Table S7). There were significant positive correlations between gender (C3) and menstruation (S4) (Figure ).

3.5. Depression and associated anxiety, somatization network

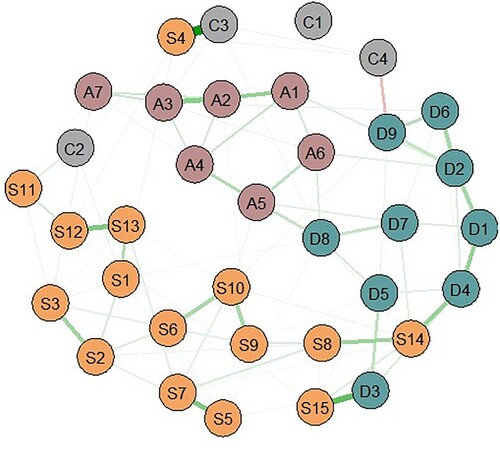

Feeling tired (S14), menstruation (S4), and shortness of breath (S10) were the somatic symptoms with the highest centrality. Uncontrollable worry (A2) was the anxiety symptom with the highest centrality, whereas feeling down, hopeless (D2), feeling tired or having little energy (D4), and trouble sleeping (D3) were the depressive symptoms with the highest centrality (Figure , Figure S4 and Table S8). Of the three groups of symptoms, the strongest associations were the following five (corresponding symptoms in parentheses): trouble sleeping (trouble sleeping; S15-D3) and feeling tired (feeling tired or having little energy; S14-D4) followed by restlessness (moving slowly/restless; A5-D8), irritability (moving slowly/restless; A6-D8), and nervous, anxious, on edge (feeling down, hopeless; A1-D2). Other associations included feeling tired (trouble concentrating; S14-D7) and irritable (feeling down, hopeless; A6-D2) (Table S9).

Figure 4. Depression and associated anxiety, somatization network. Depression symptoms (PHQ-9): D1-D9; Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7): A1-A7; Somatization symptoms (PHQ-15): S1-S15; C1: number of depressive episodes; C2: number of chronic diseases; C3: gender; C4: education. Green was for positive and red was for negative edges.

3.6. Stability analyses

The results of the node stability analysis showed that the centrality order of nodes remained stable, even after dropping up to 50% of the nodes in each network.

4. Discussion

In general, there were common central symptoms in the four networks. Feeling tired or having little energy and feeling down, hopeless were the central symptoms of depression in each network. The diagnostic criteria require that either depressed mood and / or the loss of interest or pleasure be present for a diagnosis of major depression (Aggen et al. Citation2005). Unexpectedly, low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom for each of the four networks.

Interestingly, fatigue was a central symptom of each network. Fatigue is closely related to depression (Corfield et al. Citation2016a). Individuals with medically unexplained fatigue or recurrent chronic fatigue are approximately 28 times more likely to have a lifetime diagnosis of depression than non-fatigued individuals within the community. Depression, dysphoric episodes and somatization symptoms appear to be strong predictors of both chronicity and the onset of fatigue (Addington et al. Citation2001). Does fatigue cause depression, or is it depression that causes fatigue? Alternatively, fatigue and depression are conditions that arise concurrently as a result of a common underlying pathophysiological process. In a large twin study, the co-occurrence of depression and fatigue was mainly due to shared genetic factors rather than overlapping symptomatology. A significant additive genetic correlation of 0.71 [95% CI = 0.51–0.92] and bivariate heritability of 21% [95% CI = 10–35%] was observed between depression and fatigue (Corfield et al. Citation2016b). Network theory suggests that treatment focused on maintaining central symptoms should have the greatest effect on reducing all symptoms in the psychopathology network (Borsboom and Cramer Citation2013) Depression and fatigue are associated with increased activation of the immune system, which may serve as a valid target for treatment (Lee and Giuliani Citation2019). In addition, interventions aimed directly at reducing fatigue are particularly effective in treating symptoms associated with depression, such as participation in physical activity (Saligan et al. Citation2019; Stephens et al. Citation2019). Other potentially helpful interventions would include medication reviews to reduce the use of analgesics that have fatigue as a side-effect and bright light therapy, which has shown promise as a strategy for treating fatigue (Ancoli-Israel et al. Citation2012). Further research is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Unlike in the previous study, loss of pleasure or sad mood is the most central symptom in MDD (Bringmann et al. Citation2015; Fried et al. Citation2016; Hakulinen et al. Citation2020). Previous studies mainly focused on the symptoms of MDD, without considering impact of the number of depressive episodes, number of chronic diseases, gender and education on the network. After introducing these covariates, we found that low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom for each of network. In other words, the treatment of loss of interest or pleasure cannot achieve better therapeutic effect than that the treatment of depressed mood and fatigue for our sample population. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with different comorbidities have different network centrality (Jones et al. Citation2018). And our study included three other covariates, which affected the structure of the network so that loss of interest or pleasure was no longer the central symptom.

Studies have found similar central symptoms of depression, namely depressed mood and fatigue (Cramer et al. Citation2010; Bringmann et al. Citation2015; van Borkulo et al. Citation2015). However, these results are based on different scales and populations, and the data are not collected for the purpose of network analysis (Robinaugh et al. Citation2020). Future research needs to be clearly designed. Based on the current study, the symptoms that are the core criteria for the MDD diagnosis, namely depressed mood is more important in the MDD case network (van Borkulo et al. Citation2015). Perhaps all empirically supported treatments for depression can address this symptom to some extent.

There is a strong correlation between depression and anxiety, and the symptoms overlap (Hettema Citation2008). Symptoms with a strong correlation in depression and anxiety networks, such as restlessness, slow movement / restlessness, and trouble concentrating, may be a combination of the neurovegetative system. In addition, anxiety and somatic symptoms also have some weak correlations, such as being afraid that something awful might happen (pain in the arm, legs) and restlessness (shortness breath). This supports the correlation between anxiety and somatization (Haug et al. Citation2004). In addition to fatigue, menstruation and shortness breath are also at the center of the somatization network. This high level of centrality for shortness breath may represent a unique feature that is specific to Chinese depression patients. After adding covariates, menstruation replaced fainting and became the central symptom. Studies have found that menstrual related symptoms, including premenstrual syndrome and menstrual pain are associated with mental disorders and depression in young women (Fukushima et al. Citation2020). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives and the treatment of related gynecological diseases may help to improve the mental health of young women (Lopez et al. Citation2008; Bernardi et al. Citation2017). In summary, interventions targeting these central symptoms may be effective in alleviating both depressive and somatic symptoms. This will need to be verified in different samples in the future.

Our study also found that education was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation, which was also reported in previous studies (Gan et al. Citation2012; Wang and Wu Citation2021). We speculate that the threshold for treatment seeking differs as a function of education, that is, more educated patients may seek treatment when their symptoms are not so severe.

This study has several limitations. The first limitation is that this study used cross-sectional data, so it was not possible to examine the dynamic or vertical relationship between symptoms. In the future, patients should be followed for a longitudinal dynamic study. Second, we mainly use self-rating scales to measure patients’ symptoms, and there are overlaps among the scales, so future studies should be more standardized in study design. Third, our study used a sample of inpatient or outpatient psychiatric patients whose condition was relatively severe, mainly young female college students, and the results could not be generalized to other populations.

5. Conclusion

This study is the first to use network analysis to explore anxiety and somatization symptoms in patients with depression. The importance of feeling down, hopeless and fatigue as central symptoms of each network is emphasized. Fatigue symptoms are particularly common in people with depression, and their influence at the center of the depression network may be underestimated. In addition, low interest or pleasure was not the central symptom for each network and education was negatively correlated with suicidal ideation.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (79.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Zhongchun Liu: Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Simeng Ma, Jun Yang, Zhongchun Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology. Simeng Ma, Haofan Cheng, Wei Wang, Guopeng Chen, Hanping Bai, Lihua Yao: Investigation, Resources. Simeng Ma, Jun Yang: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation. Simeng Ma: Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Dr. Liu. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addington AM, Gallo JJ, Ford DE, Eaton WW. 2001. Epidemiology of unexplained fatigue and major depression in the community: The Baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981-1994. Psychol Med. 31:1037–1044. doi:10.1017/S0033291701004214.

- Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS. 2005. DSM criteria for major depression: evaluating symptom patterns using latent-trait item response models. Psychol Med. 35:475–487. doi:10.1017/S0033291704003563.

- Ancoli-Israel S, Rissling M, Neikrug A, Trofimenko V, Natarajan L, Parker BA, et al. 2012. Light treatment prevents fatigue in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 20:1211–1219. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1203-z.

- Bekhuis E, Boschloo L, Rosmalen JGM, Schoevers RA. 2015. Differential associations of specific depressive and anxiety disorders with somatic symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 78:116–122. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.007.

- Bener A, Al-Kazaz M, Ftouni D, Al-Harthy M, Dafeeah EE. 2013. Diagnostic overlap of depressive, anxiety, stress and somatoform disorders in primary care. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 5:2006–2009. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00215.x.

- Bernardi M, Lazzeri L, Perelli F, Reis FM, Petraglia F. 2017. Dysmenorrhea and related disorders. F1000Research. 6:1645. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11682.1.

- Borsboom D. 2008. Psychometric perspectives on diagnostic systems. J Clin Psychol. 64:1089–1108. doi:10.1002/jclp.20503.

- Borsboom D. 2017. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 16:5–13. doi:10.1002/wps.20375.

- Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. 2013. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 9:91–121. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608.

- Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, Krause RW, Schoch D, Wichers M, et al. 2019. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J Abnorm Psychol. 2006–2009. doi:10.1037/abn0000446.

- Bringmann LF, Lemmens LHJM, Huibers MJH, Borsboom D, Tuerlinckx F. 2015. Revealing the dynamic network structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Med. 45:747–757. doi:10.1017/S0033291714001809.

- Contreras A, Nieto I, Valiente C, Espinosa R, Vazquez C. 2019. The study of psychopathology from the network analysis perspective: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 88:71–83. doi:10.1159/000497425.

- Corfield EC, Martin NG, Nyholt DR. 2016a. Co-occurrence and symptomatology of fatigue and depression. Compr Psychiatry. 71:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.004.

- Corfield EC, Martin NG, Nyholt DR. 2016b. Shared genetic factors in the co-occurrence of depression and fatigue. Twin Res Hum Genet Off J Int Soc Twin Stud. 19:610–618. doi:10.1017/thg.2016.79.

- Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HLJ, Borsboom D. 2010. Comorbidity: a network perspective. Behav Brain Sci. 33:137–193. doi:10.1017/S0140525X09991567.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Sitnikova K, van Marwijk HWJ, Gerrits MMJG, van der Wouden JC, Penninx BWJH, et al. 2015. Somatisation as a risk factor for incident depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 79:614–619. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.07.007.

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. 2018. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 50:195–212. doi:10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1.

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. 2012. Qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Softw. 48:2006–2009. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i04.

- Fried EI, Epskamp S, Nesse RM, Tuerlinckx F, Borsboom D. 2016. What are “good” depression symptoms? Comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression in a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 189:314–320. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.005.

- Fukushima K, Fukushima N, Sato H, Yokota J, Uchida K. 2020. Association between nutritional level, menstrual-related symptoms, and mental health in female medical students. PLoS One. 15:e0235909. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235909.

- Gan Z, Li Y, Xie D, Shao C, Yang F, Shen Y, et al. 2012. The impact of educational status on the clinical features of major depressive disorder among Chinese women. J Affect Disord. 136:988–992. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.046.

- Hakulinen C, Fried EI, Pulkki-Råback L, Virtanen M, Suvisaari J, Elovainio M. 2020. Network structure of depression symptomology in participants with and without depressive disorder: the population-based health 2000–2011 study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 55:1273–1282. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01843-7.

- Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. 2004. The association between anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms in a large population: the HUNT-II study. Psychosom Med. 66:845–851. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000145823.85658.0c.

- Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. 2003. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 65:528–533. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000075977.90337.E7.

- Hettema JM. 2008. The nosologic relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and major depression. Depress Anxiety. 25:300–316. doi:10.1002/da.20491.

- Jones PJ, Mair P, Riemann BC, Mugno BL, McNally RJ. 2018. A network perspective on comorbid depression in adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 53:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.008.

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Flint J, Borsboom D, Fried EI. 2018. The centrality of DSM and non-DSM depressive symptoms in Han Chinese women with major depression. J Affect Disord. 227:739–744. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.032.

- Kim JHJ, Tsai W, Kodish T, Trung LT, Lau AS, Weiss B. 2019. Cultural variation in temporal associations among somatic complaints, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. J Psychosom Res. 124:109763. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109763.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. 2001. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 16:606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. 2002. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 64:258–266. doi:10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008.

- Lee CH, Giuliani F. 2019. The role of inflammation in depression and fatigue. Front Immunol. 10:1696. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01696.

- Lipowski ZJ. 1988. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. 145:1358–1368. doi:10.1176/ajp.145.11.1358.

- Lopez LM, Kaptein A, Helmerhorst FM. 2008. Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD006586. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006586.pub2.

- Mcnally RJ. 2012. The ontology of posttraumatic stress disorder: natural kind, social construction, or causal system? Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 19:220–228. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12001.

- McNally RJ. 2016. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav Res Ther. 86:95–104. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.006.

- Opsahl T, Agneessens F, Skvoretz J. 2010. Node centrality in weighted networks: generalizing degree and shortest paths. Soc Networks. 32:245–251. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.006.

- Park SC, Kim D. 2020. The centrality of depression and anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder determined using a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 271:19–26. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.078.

- Robinaugh DJ, Hoekstra RHA, Toner ER, Borsboom D. 2020. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008-2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol Med. 50:353–366. doi:10.1017/S0033291719003404.

- Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, McNally RJ. 2016. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol. 125:747–757. doi:10.1037/abn0000181.

- Rodriguez BF, Weisberg RB, Pagano ME, Machan JT, Culpepper L, Keller MB. 2004. Frequency and patterns of psychiatric comorbidity in a sample of primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 45:129–137. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.09.005.

- Ryder AG, Yang J, Zhu X, Yao S, Yi J, Heine SJ, et al. 2008. The cultural shaping of depression: somatic symptoms in China, psychological symptoms in North America? J Abnorm Psychol. 117:300–313. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.300.

- Saligan LN, Farmer C, Ballard ED, Kadriu B, Zarate CAJ. 2019. Disentangling the association of depression on the anti-fatigue effects of ketamine. J Affect Disord. 244:42–45. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.089.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. 1998. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 59(Suppl. 20):22–57.

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. 1999. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 341:1329–1335. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411801.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. 1999. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Jama. 282:1737–1744. doi:10.1001/jama.282.18.1737.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. 2006. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 166:1092–1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

- Stephens S, Shams S, Lee J, Grover SA, Longoni G, Berenbaum T, et al. 2019. Benefits of physical activity for depression and fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal analysis. J Pediatr. 209:226–232. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.01.040.

- Toft T, Fink P, Oernboel E, Christensen K, Frostholm L, Olesen F. 2005. Mental disorders in primary care: prevalence and co-morbidity among disorders. Results from the functional illness in primary care (FIP) study. Psychol Med. 35:1175–1184. doi:10.1017/s0033291705004459.

- van Borkulo C, Boschloo L, Borsboom D, Penninx BWJH, Waldorp LJ, Schoevers RA. 2015. Association of symptom network structure with the course of [corrected] depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 72:1219–1226. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2079.

- Wang G, Wu L. 2021. Social determinants on suicidal thoughts among young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168788

- Zhou X, Min S, Sun J, Kim SJ, Ahn JS, Peng Y, et al. 2015. Extending a structural model of somatization to South Koreans: cultural values, somatization tendency, and the presentation of depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 176:151–154. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.040.