Abstract

The aim of this article is to explore Norwegian family counselors´ professional assessments when children are at potential risk due to enduring parental disputes. These disputes present complex clinical challenges and are often considered being in a gray area of whether the situation is a family matter or if there is a need for the assessment of child welfare services. The analysis builds on a survey and focus group interviews. Findings from this study show that family counselors are concerned for children involved in interparental conflicts, but this concern does not necessarily manifest in their reporting to the child welfare services. Rather, our findings show that the family counselors prefer to utilize their own services and that of other stakeholders in such situations. Enduring conflicts present significant challenges relating to the assessments and decisions of what is the most adequate help for the unique child and family. The article points toward professional thresholds for intervention and risk of child maladjustment as a challenging aspect of practice in high-conflict cases.

It is widely accepted that ongoing serious conflict between parents has negative consequences for children (Ahrons, Citation2007; Amato, Citation2010; Anderson et al., Citation2010; Boullier & Blair, Citation2018; Mutchler, Citation2017; Shumaker & Kelsey, Citation2020; van Dijk et al., Citation2020). Intense interparental conflicts, as well as low-quality parenting, have been identified as important risk factors for child adjustment (Boullier & Blair, Citation2018; van Dijk et al., Citation2020). It is not simply the presence of the conflict itself that affects the outcome for children, but rather the characteristics of the conflicts and how parents deal with them (Reynolds et al., Citation2014). Krishnakumar and Buehler (Citation2000) review interparental conflict as a multidimensional construct including elements of frequency, expressions, duration, intensity and the degree of resolution. Polak and Saini (Citation2019) furthermore propose a comprehensive definition capturing the complexity and interactions of different risk factors and indicators on different levels in an ecological transactional framework. However, emotional harm is hard to prove and monitor, especially in situations where both parents attempt to make the other look bad (Saini et al., Citation2019).

Parents involved in parental conflicts to the extent that it causes severe maladjustment for children may result in family counselor’s duty of mandatory reporting to child welfare services (CWS). Crossover cases of families involved in both family law litigations and child protection proceedings are becoming more common (Houston et al., Citation2017). Bala et al. (Citation2010) emphasize an awareness of professional understanding when it comes to interparental conflicts being considered a family matter or when there is a necessity for litigation interventions as a professional response. Regardless of duty of mandatory reporting when applicable, this is not a straight-forward task for the family counseling service (FCS) in contact with high-conflict families, but a complex task of thorough assessing and consideration (Heggdalsvik, Citation2020). It is essential to identify the considerations which form the basis for different pathways of solutions. Fulfillment of mandatory reporting to child welfare services might be considered as an alternative, but if not, what are the other optional alternatives?

The aim of this study is to explore the considerations of professional family counselors in handling interparental conflicts when children are at risk of maltreatment. Specifically, how do family counselors outline and handle the question of appropriate interventions for children involved in high-conflict disputes?

Family counseling services and child welfare services in Norway

Public services in Norway are framed within a strong governmental system. There is a common division between “Child Protection” in the liberal western countries (e.g. US, Canada and England) and “Child Welfare” in a social democratic context like Norway and the other Nordic countries (e.g. Sweden and Denmark) (Gilbert et al., Citation2011; Khoo, Citation2004). In a child welfare context, the interference in family matters has an extended legitimacy and a broader scope than in a child protection context. This might be the reason Norway is the only country in the world with mandatory mediation when parents are separating. The FCS is a low-threshold specialist service regulated by Family Councelor Services Act (Citation1997) and the Children Act (Citation1981). FCS is the foundation for families experiencing domestic issues, issues of child-rearing and conflicts related to relationships within families. It is a free public service with geographically widespread locations. Families experiencing high conflicts usually have extended contact with the FCS.

The child welfare system (CWS) is regulated by the Child Welfare Act (Citation1992) and the mandate is to make sure that children and youths at risk of being neglected get the help they need within a proper timeframe. The scope of the Norwegian CWS is broad, with preventive as well as protective measures (Samsonsen, Citation2016).

In 2020, the Norwegian FCS worked on a total of 36 632 cases (Statistics Norway, Citation2021b). In the same year, the FCS sent 568 referrals to the CWS, of which 324 of these were registered in the category of “high degree of conflict at home” (Statistics Norway, Citation2021a). Studies show that the total amount of high-conflict cases seems to be stable between 10 and 15% of the total number of all cases (Black et al., Citation2016; Buchanan et al., Citation2001). Children and families involved in high conflicts might receive measures from both these services.

Considerations and risk assessment in “high conflict” cases

The question of which pattern or dimensions of parental conflict are associated with possible maladjustments for children are of interest to professionals. How should intervention thresholds be designed to ensure that the choices and agency of vulnerable families are respected, but at the same time make sure that children at risk of harm are protected regardless of their parents’ circumstances? Studies testify to the continual struggle to align practice and policy to assess child safety and ensure that children are protected, while at the same time families are provided with the support they require in order to provide a safe and supportive environment for children (Black et al., Citation2016; Saini et al., Citation2012). A challenge is the ability to distinguish among types of conflicts; how the conflicts affect children involved; and importantly how professionals can support and signpost appropriate help (Reynolds et al., Citation2014). This is a core element of professional assessment, and an important crux is whether these situations meet the criteria of mandatory reporting to the CWS as child neglect (Joyce, Citation2016). Authorities working with children and families are obliged to adhere to mandatory reporting in order to fulfill their duty to notify, if there is a reason to believe that a child needs child welfare assessment. However, there is significant research pointing toward the struggle of frontline practitioners to keep both the “risk” and “support” functions in mind (Dingwall et al., Citation2014; Sudland & Neumann, Citation2020).

Supporting services experience interparental conflicts as challenging and difficult (Houston et al., Citation2017; Jevne & Andenaes, Citation2015; Johnsen et al., Citation2018; Sudland, Citation2019; Sudland & Neumann, Citation2020). Black et al. (Citation2016) explored characteristics of child custody disputes within the context of child protection investigations and how these cases differ from other disputes. Several personal, professional and organizational influences are at play when professionals make determinations about child maltreatment (Horwath, Citation2007). Professionals will respond differently to different scenarios, and responses will be influenced by individual attitudes, personal experience and characteristics of the children and caregivers (Levi & Crowell, Citation2011). Individual variation among professionals compounded by unclear standards of when to report suspected maltreatment and how to interpret the term “reasonable suspicion of harm”. In addition, a variety of understandings about children’s needs and the role of professionals in ensuring children’s wellbeing and families’ rights to privacy, is at stake here. Inconsistent reporting practices might lead to inadequate help and protection of children and cause inequitable treatment of parents (Levi & Crowell, Citation2011). Mandatory reporting is a key component of risk-averse forensic systems that individualize the factors that are at play (Lonne et al., Citation2015). A challenge for professionals is the assessment of potential risk of maltreatment due to high conflict among parents. A central question to address here is whether the level of risk meets the criteria for mandatory reporting.

Method

A study conducted in 2015 by author 1 in this study indicated variations in FCS staffs assessments of level of risk in vignette families and a variation according to report to CWS in these families (Heggdalsvik, Citation2020). This study (a questionnaire survey design, hereby referred to as study 1) served as a basis for a second study conducted in 2020 to further explore and investigate these findings (focus group design, hereby referred to as study 2). The findings presented in this paper are based on data from the survey (study 1) combined with data from the focus group interviews conducted in 2020 (study 2). Quotes are presented from both open-ended questions in the survey and the focus group interviews. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Sampling and data collection

Study 1 utilized an electronic survey design comprised of a 20-question questionnaire including four vignettes. The method was chosen to allow for a distribution of a national survey in order to reach all 51 FCSs in Norway in January 2015. The respondents were recruited by an e-mail to all services with information about the project. We then asked if we could access the family counselor’s e-mail address with the intention of mailing them and asking them to respond to the survey. The survey was considered taking 20–25 minutes to answer and was sent to the 32 FCSs that responded to our request, a total of 219 family counselors. The survey was closed in April 2015, with a total of 115 respondents. There is a variation in the number of counselors at the different services and geographic variation of locations in Norway. The survey included open-ended responses, which have allowed for an in-depth analysis of the experiences of the professionals.

The respondents in the survey had between 3 months to 40 years of work experience at the FCS, with an average of 11.5 years. Of the 115 respondents, 70% were female and 30% male. The average age of the counselors was 53.5 years of age. Their educational backgrounds were social work, psychology, child welfare educator, nurse, preschool teacher and social educator. Common to all the respondents was continuing education at master’s level or specialist education within family therapy. Their work experience varied, but a common denominator was experience from mental health services, the child welfare service, substance abuse rehabilitation, social services and probation. The respondent’s background information shows extensive work experience from FCSs in addition to continuing education and former work experience from other parts of the support system before they started their work at the FCS.

In study 2, focus group interviews were chosen to address the research questions in this article with the purpose to further explore and investigate findings from study 1 (Justesen & Mik-Meyer, Citation2012). Focus group interviews take place in an artificial context compared to the daily basic work of professionals but may still give researchers privileged access to in-group conversations containing key professional terms and categories in a situation where they are usually used. Discussions occurring within focus groups provide rich data from the group opinions associated with a given issue (Halkier, Citation2010; Kitzinger, Citation1995).

The interviews were conducted in January 2020, and the sample consisted of four focus groups with six members with, a total of 24 participants. Recruitment started with information about the study to the managers of two CWSs and two FCSs. Two focus groups were conducted with professionals at two different FCSs and two focus groups were the composite of professionals at two different CWSs. A request with information about the study was sent to managers of the different services. The services were asked to participate with informants whose daily work involved interparental conflicts.

The interviews were conducted at the offices of the different services. The informants were introduced to 8 cardsFootnote1 organized into two main topics. One of the informants in each group took the responsibility to ask questions from the cards in a chronological order. The participants were instructed not to glance at the next card before the focus group agreed that they had discussed each question. Main topic 1 contained the heading “What inhibits and what promotes constructive collaboration between CWSs and FCSs in cases containing deadlocked parental conflicts?” Analysis of data connected to main topic 1 will be presented in another paper (Samsonsen et al., Citation2022). The heading of main topic 2 was: “How is collaboration practice between FCSs and CWSs in situations when the services are concerned about the care situation of children?”

The participants were presented with following questions: (1) What distinguishes your meetings with children and families in these situations? (2) Children living in families with deadlocked parental conflicts might be covered by two acts: The Children Act and the Child Welfare Act. What do you think about that? Eventual experiences. (3) What are your experiences from reporting concerns for children? What circumstances trigger the duty to report as you see it? Can you please discuss what assessments precede a report of concern? Can you please express what assessments you make in advance of such inquiries? (4) Do you have any thoughts or suggestions about what FCSs and CWSs can additionally do to help children living with deadlocked parental conflicts that are of concern?

All interviews lasted approximately 1.5 hours, including a small break between the two different topics. The interviews were recorded and transcribed by an external professional after the interviews were conducted.

Data analysis

The analysis is based on background- and open-ended questions in the survey, emphasizing what the family counselors find important when assessing children’s situations involved in high conflicts, and transcriptions from the two focus group interviews with family counselors. The article focuses on the content of the family counselors’ assessments based on the questions they were given and analyzed in terms of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Clarke & Braun, Citation2018). The analysis of the focus group data is seen toward the open-ended answers in the survey. Statements were read thoroughly several times and four themes were uncovered as possible pathways for solutions: (1) Expanded efforts in family counseling services, (2) External low-threshold services, (3) Legal proceedings and (4) Whether or not to notify child welfare services.

Results

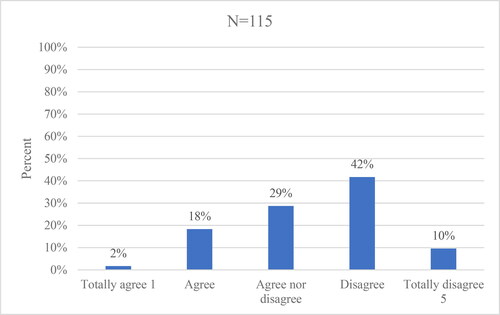

In study 1, the family counselors were asked if they find it difficult to assess whether a child’s caring situation is to be reported to CWS. The question was graduated from 1 until 5, where 1 was labeled totally agree and 5 totally disagree (N = 115) (see ).

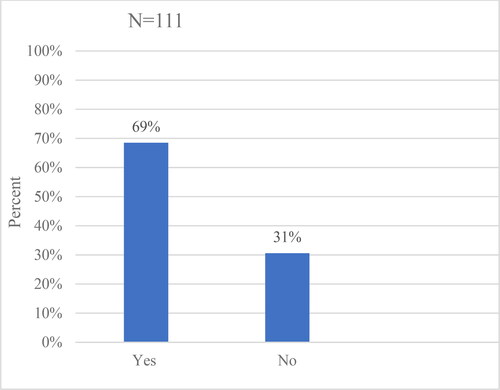

The family counselors were asked whether during the last two years they had applied for guidance and anonymously discussed concern for children involved in high conflict. Of the responses (N = 111), 69% of the family counselors answered yes and 31% answered no (see ).

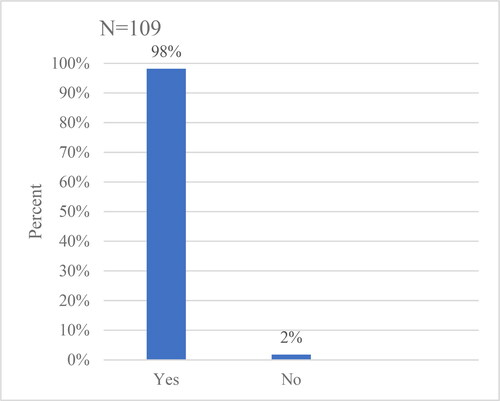

In the question of whether during the last two years they had been concerned to the extent that they had considered reporting to CWS, 98% answered yes and 2% answered no (N = 111) (see ).

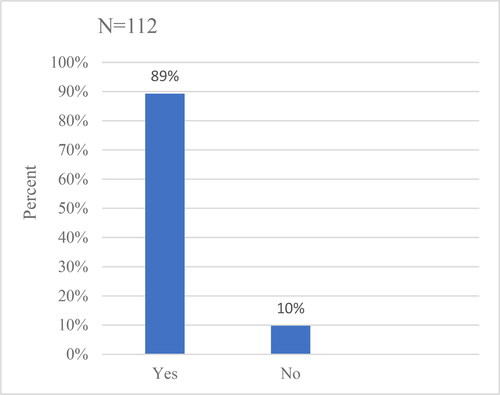

Concerning the question of whether they actually had reported to the child welfare service during the last two years, 89% answered yes, 10% answered no and 1% answered that they did not know (N = 109). With regard to the follow up question if they answered yes to having reported in the last two years: 27 out of the 115 respondents answered, and the average number was 3 reports (see ).

As we can see from the figures, a high percentage of the participants express that they have applied for guidance, considered reporting and that they have reported. Viewed against national statistics, the yearly number of reporting can be considered as low, as mentioned above: 324 in 2020. Of interest then is the question of what forms the basis of family counselors’ considerations to report, and what other options are considered as potential alternative pathways to reaching a solution?

When analyzing different possible action pathways where family counselors are concerned, we identified four main themes. In the following, analysis from approaches 1 and 2 will be presented together as the following themes: (1) Expanded efforts in family counseling services, (2) External low-threshold services, (3) Legal proceedings, and (4) Whether or not to notify child welfare service– dilemmas.

Expanded efforts in family counseling services

Family counselors are clear that enduring conflicts among parents when children are involved is challenging, and they express that these cases often are the most difficult and sometimes make them feel powerless. Nevertheless, the family counselors are also clear that they can offer help to children and parents as part of their service and mandate. One family counselor expresses the following: “We are not paralyzed or exhausted when these cases come in, and we have lots of competence in our service.” The emphasis is on conversations with both parents and the children involved in order to make sure they understand the situation correctly before they eventually propose other measures. The following statement is an example: “I would have invited all members of the family to conversations, starting with individual appointments for the parent followed by conversations with the children.” At the same time, the counselors seem aware that there are prerequisites to consider if they are to succeed. The emphasis is on both parents’ ability to speak openly about the family situation and whether the parents show willingness to work with themselves and at the same time help their children with their feelings. These factors are considered when assessments are made relating to whether the family counselors find they can work with the family situation through conversations at the FCS and the question of awaiting a referral. Positive experiences from earlier success from working together with parents in conflict for a long time, where often two counselors have been involved, indicate a motivational factor to not give up on conversations and dialogue: “Gradually discovering that parents see their child in a different way, that is quite nice.”

The family counselors mention educational programs arranged regularly by their own service, especially the two-hour mini-program “Conflict-filled collaboration” designed for parents in Norway. This is a program specially designed for parents after break-ups, with the intention to prevent further conflict escalations. In the focus group interviews the family counselors speak of red, yellow and green families as an internal degree of categorization relating to concern about children, where the highest concern is labeled red. They also speak of experiences with the group approach “No Kids in the Middle Programme” developed by Van Lawick and Visser (Citation2015).

Although the family counselors are concerned about keeping the cases at a low threshold level within their own service, they also express contradictions or dilemmas as they do not have a mandate to impose interventions by force. The family counselors discuss this as a dilemma:

It is actually a paradox, we are within voluntary services, we are concerned with the Children Act, we believe in voluntariness as a condition to solve family matters, and at the same time, we are concerned about the children and think that someone has to assess, but then we give the concern away to someone else. Then we have given the concern to them (child welfare service), but it is not always the case that they are able to do something with the concern, and then you get the situation in return.

Another dilemma emerges when the family counselors discuss their lack of a mandate in relation to their attempts to promote the educational or preventive programs they can offer. The educational programs are their modalities to promote knowledge about the consequences of prolonged conflicts to parents. Apart from one-hour mandatory mediation if there are children under the age of sixteen involved, the family counselors point to the fact that the services they can offer are optional and they cannot make attendance from parents obligatory. A lack of authority is emphasized through the discussions, but no one raised the question of whether they should have had more authority within their mandate.

External low-threshold services

The family counselors refer in their discussions to specialized programs as “Aggression Replacement Training” or they encourage parents themselves to contact services such as kindergartens and schoolteachers. Health nurses are mentioned and discussed as potential services to help children and families. These statements can be understood as an attempt to involve professionals offering low-threshold services and not to expand the conflict more than necessary. Emphasis is put on information to parents about their rights as parents and the importance of their regular contact with the school and kindergarten.

The family counselors express an experience that the extended family and network, mentioned as “tribal warfare” or “cheerleaders” (Johnston et al., Citation2009; Polak & Saini, Citation2019), often are a powerful but invisible voice behind the scenes in situations concerning parents’ conflict. Family councils as an attempt at developing creative help are discussed in order to include the extended “cheerleaders” or new partners. As for instance: “Those times when we have invited in new partners, that is when we have been successful at moving forward.” Another preventive that emerged in relation to reflections of different low-threshold services is suggestions of groups for children at school, including direct information from both the FCS and CWS to school-going children and youths.

Legal proceedings

In Norway, district courts handle interparental conflicts if mediation at the FCSs has not been successful. As a consideration of what can be understood as a way to promote the parents’ own responsibility or autonomy instead of sending a referral to the child welfare service, it might be preferable to advise parents to use court proceedings as the following statement indicates: “When parents disagree about where the children are to live, child custody and togetherness, then there is only the court that can decide. They are obliged to familiarize themselves with the children’s situation.” An alternative discussed is to advise one or both parents of a new round of mediation or alternatively advise a court proceeding. Another proposal is an attempt to find an in-between solution between FCS and the court.

On the other hand, one informant in the focus group interview expressed concern regarding the practice of advising parents to go to court:

We then forget that it is the poorest and the richest who can afford to go to court, because for most parents with a median income it is far too expensive. We speak of court as a possibility and a right that actually is not accessible for that many, and then, what about those who do not want to go to a family counselling service, and they are not qualified for services at the child welfare service? It is also reasonable to be concerned about those children. They do not get help at all because no one intervenes.

Another informant expressed concern whether it is the mandate of the court to arrive at a deal. In contrast, an important aspect in high-conflict cases is the question of the parents’ ability to provide care. The family counselors therefore raise the question of whether the children are sufficiently taken care of within a court “deal” system.

Whether or not to notify child welfare services—dilemmas

In parallel, when speaking of the mandatory duty to report to the CWS, the family counselors often spoke of attempts at collaboration in order to get a chance to speak with parents together. Whilst some family counselors use the term “attempt” when expressing collaboration with CWS, others were clear that they do report and always collaborate with either one or preferably both parents when they do so. The family counselors underline in general the importance of parents knowing what is going on and to make sure parents understand their reasons for reporting.

Another solution is to consider parents as responsible for their own children’s situation and encourage parents to report to child welfare service themselves due to the importance of not taking one party’s information in high-conflict cases as the truth: “I will try to get both parents to speak before drawing a conclusion. If the father is concerned for his children, he can report based on what he has seen, experienced and heard.” Others are not that clear, as for instance,

Sometimes I find it difficult to know whether to report to the child welfare service or whether I need to advise them to go to court, sometimes there is a kind of borderline there. Or an alternative is to do both. One of the efforts, the parents need to do themselves, and the other, we might need to assist them.

Despite concern for the children involved, the informants stated that there are several issues to consider here. The stress reporting causes to parents is the reason why they find it important to be in dialogue with parents, but also the fact that they have experienced that child welfare service has little to offer. The family counselors are, above all, concerned about dialogue, and if and when an investigation starts at the CWS, they emphasize that there is a predictable plan for the parents.

The family counselors find several issues to be dilemmas:

It is a paradox, since we are within the framework of voluntariness, and the Children Act. In addition, we consider voluntariness as a prerequisite for solving matters, and at the same time we are concerned for the children and think that someone has to assess, and then we pass on the concern to someone else, but they cannot always do something with that concern.

An expressed concern and dilemma were also the experience of getting cases in return. This dilemma is particularly underlined by those participants who thought that the threshold and attitude of reporting is affected by experiences of how earlier reports have been received. The different experiences of whether the CWS has previously been able to handle similar cases then affects the question of whether to report or not.

One of the participants in the focus group interview expressed a statement that is at the very heart of this study:

How serious is it when it is considered to be harmful but not to the extent of a care order? There is quite a huge gap from harmful to care order, and I believe, there are quite a lot of children in that sphere.

Discretional considerations such as weighting matters as to whether it is a parent’s responsibility to protect a child from the other parent, or whether the child should be protected from both parents, or an effort should be made at doing something about the conflict are often described as “war material.” An understanding and underlining of the different mandates of the FCS and CWS in relations with parents can also be interpreted when participants express that they sometimes tell the parents that if they do not stop the child’s visitation arrangement with the other parent, the CWS might assess them as not sufficiently protecting the child.

Discussion

Enduring interparental conflict poses a potential risk of emotional maltreatment of children (Birnbaum & Saini, Citation2013; Polak & Saini, Citation2019), not only from a present perspective but also from a life course perspective (Ahrons, Citation2007; Boullier & Blair, Citation2018). Findings of this study correspond with other studies demonstrating the challenging aspects of these conflicts as experienced by professionals (Jevne & Andenaes, Citation2015; Sudland, Citation2019; Sudland & Neumann, Citation2020). The question is how to handle these family matters, which manifest as complex and wicked problems (Devaney & Spratt, Citation2009; Rittel & Webber, Citation1973) without any straightforward or obvious measurements or actions.

In this study, all counselors involved agreed on the “high risk” posed by enduring parental conflict for children. Apart from risk evaluation, the professionals identified four pathways in how they assessed the issue of appropriate interventions for children involved in high-conflict disputes.

Expanded efforts in family counseling services

In order to help children involved in enduring parental conflicts, several family counselors emphasize attempts to find alternatives within their own service. They stress dialogue with parents and children, both separately and together, if possible, as a primary effort and a clear component of their service and mandate. Educational programs developed within the service are considered important contributions to conflict reduction. The Norwegian FCS has developed standardized structures that address high-conflict cases that are implemented nationally. The results of a recent study show that this structure is valued as a constructive framework for professional measures (Kåstad et al., Citation2021).

Another possible explanation and underlying perspective that influence family counselor assessments is an understanding of children and family through the lenses of resilience. Stokkebekk et al. (Citation2021) indicate that prolonged conflict between parents renders it impossible to find viable options for cooperation and argue that family therapists should aid and promote child and family resilience rather than make continued efforts to solve chronic conflicts. Given the findings of this study, the family resilience perspective may explain why the counselors believe in parents as the initial source for mobilizing strength and reducing the level of interparental conflict and consequences for the children.

External low-threshold services

The family counselors discuss the importance of daily life services for children and families. They encourage parents to cooperate closely with external low-threshold services, such as public health nurses, preschool teachers and kindergarten teachers. Keeping the conflict level as low as possible may explain this approach.

There is widespread agreement on the need for early intervention if some of the most negative outcomes for children and parents’ mental health and the well-being of family relations are to be prevented. A key question here is to ask how “early interventions” is understood. Sheehan (Citation2018) underlines the importance of professional understanding and the recognition of the skills required to help children and their families within the context of their conflict. An awareness of perspectives, an understanding and the content of prevention programs, the knowledge base on which they are founded and the implications of basic research are of significant value and importance (Camisasca et al., Citation2019; Grych, Citation2005; van Dijk et al., Citation2020). Sheehan (Citation2018) argues that containment is an important intention and skill that professionals can bring to the table in an attempt to address high conflict at whatever stage of its development.

Legal proceedings

An autonomy perspective may explain why family counselors advise parents to go to court for new hearings. Parents are responsible for the care of their children. The court is tasked with solving or making a judicial decision to end the parental conflict. By contrast, Cashmore and Parkinson (Citation2011) stress that parents are “repeat players” in the court system. Their study followed a program aimed at decreasing parental disputes in court systems due to its cost for parents, children, and the court system. The involvement of the court did not seem to reduce, but rather enhance the level of conflict. This argument is in line with Joyce (Citation2016), who argues that the win or lose framework of litigation encourages parents in a high-conflict situation to find faults with one another instead of focusing on cooperation. Such demands to increase the bargaining advantage results in an escalation of the conflict. A consequence of repeated litigation is that both parents become drained of emotional and financial resources and experience an increased level of stress that often causes anger, aggression and hatred. Garber (Citation2015) also argues that the complexity of high-conflict situations defies the court systems’ customary search for guilt and innocence, while challenging the understanding of children living in amidst the maelstrom of conflict. For the parents, the fulfillment of the court order may be challenging due to even higher level of conflict following the proceedings.

Whether or not to notify child welfare services-dilemmas

– in the findings suggest that family counselors experience a sense of confidence in reporting to CWS and requesting guidance. Statistics show that there is a limited number of cases reported by the FCS to CWS in Norway, each year; approximately 10% of all cases. One possible explanation is that family counselors do not find reporting to CWS as the most appropriate intervention.

These findings may indicate a dilemma in assessments. The reasoning underlying appropriate interventions is a central crux when children are at risk, namely whether or not to notify CWS. One reason not to report may be negative experiences from previous cases. Another explanation may be challenging communication between FCS and CWS in terms of uncertainty in understanding each other’s mandates (Samsonsen et al., Citation2022). The counselors in general agree on the potential risk for children exposed to an enduring high-conflict situation. They are concerned, but unsure what to do about it.

CWS is the final safety net for children, with a clear mandate and power, and is often considered a last alternative. Houston et al. (Citation2017) found that one of the greatest challenges reported by non-CPS family justice professionals was the lack of communication and coordination among the various professionals involved in high-conflict cases. Professionals, lawyers and assessors emphasized concerns or difficulties in collaborating with CPS workers and expressed concerns about a duplication of efforts and inconsistent strategies. Despite unfounded conclusions, cases involving child custody disputes are more likely to be reopened several times by child protection services with little resolution (Black et al., Citation2016). This finding may indicate that CWS may prematurely close these cases without adequately focusing on the needs of the children and families involved. Similar findings labeled the “revolving-door effect” in the study of Houston et al. (Citation2017) can be seen in line with the findings of this study, by which the family counselors express hesitation in reporting due to a concern that the cases may return without any changes or resolution.

Houston et al. (Citation2017) claim there is limited research on the effect of intervention by child protection services (CPS) in high-conflict separations or best practices. CPS respondents complain that they were not viewed by other professionals involved in these cases as partners or allies working to advance the interests of children but were too often considered adversaries. The other side of the dilemma is shown in the study by Sudland and Neumann (Citation2020), which asks whether one should take all the children who are at risk of neglect due to their parents’ deadlocked disputes, and points out the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in order to strengthen CWS assessments and interventions. A key question here is also whether mandatory reporting in high-conflict cases escalates the conflict dimension more than it signalizes multi-agency services and professional collaboration as appropriate assistance for the children involved.

Conclusion

This study shows that family counselors are concerned about children involved in interparental conflicts and consider different pathways to help these families. Expanded services within FCS, recommending low-threshold services or court proceedings and possible reporting to CWS are all strategies aimed at resolving parental conflicts. The conflicts challenge the assessments and decisions of what is the best way to help the unique child and family. Black et al. (Citation2016) point toward a need for devoting more attention to exploring ways to engage with families involved in child custody disputes to enable better coping with the complexities of a family breakdown. In the current study, the family counselors show a rather high level of confidence when asked in general about reporting. Nevertheless, when it comes to specific cases, the discretionary assessments regarding interventions do not appear to be as straightforward. Our findings are in line with Houston et al. (Citation2017) who found that high-conflict cases continue to be challenging for professionals in the family justice system. Although this is a study carried out in Norway, it highlights the overall challenging aspects of child maladjustment and practice in high-conflict cases.

Limitations

The difference between assessments made in a digital survey and in focus group interviews, as opposed to real world assessments, is a limitation of this study. Social interaction between the participants in the focus group in terms of body language etc., was not the subject of study in the analysis, as such interaction may affect the reflections of the different participants. The survey was conducted in 2015 and the focus group interviews were held in 2020, which may be a possible limitation. In the period 2015-2020, there has been national focus on the topic which raises the question of the participants´ responses in terms of increased knowledge on the topic.

Ethical standards and informed consent

This research was approved by Norwegian center for research data in 2014 (study 1) and 2019 (study 2). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants being included in the study.

Disclosure statement

Authors declare no conflicts to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Inger Kristin Heggdalsvik

Inger Kristin Heggdalsvik, Institute of Welfare and Participation, Faculty of Health and Social Science, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences; Vibeke Samsonsen, Institute of Welfare and Participation, Faculty of Health and Social Science, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

Vibeke Samsonsen

Inger Kristin Heggdalsvik, Institute of Welfare and Participation, Faculty of Health and Social Science, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences; Vibeke Samsonsen, Institute of Welfare and Participation, Faculty of Health and Social Science, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

Notes

1 Papercrafts were made as 6x6 cards with separate questions.

References

- Ahrons, C. R. (2007). Family ties after divorce: long-term implications for children . Family Process, 46(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00191.x

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666. http://search.proquest.com/docview/618699799/fulltextPDF?accountid=15685

- Anderson, S. R., Anderson, S. A., Palmer, K. L., Mutchler, M. S., & Baker, L. K. (2010). Defining High Conflict. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 39(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2010.530194

- Bala, N., Birnbaum, R., & Martinson, D. (2010). One judge for one family: Differentiated case management for families in continuing conflict. Can. J. Fam. L, 26, 395.

- Birnbaum, R., & Saini, M. (2013). A scoping review of qualitative studies about children experiencing parental separation. Childhood, 20(2), 260–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568212454148

- Black, T., Saini, M., Fallon, B., Deljavan, S., Theoduloz, R., & Wall, M. (2016). The intersection of child custody disputes and child protection investigations: Secondary data analysis of the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect (CIS-2008). International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience (IJCAR), 4(1), 143–157.

- Boullier, M., & Blair, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences. Paediatrics and Child Health, 28(3), 132–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2017.12.008

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buchanan, A., Hunt, J., Bretheron, H., & Bream, V. (2001). Families in conflict: perspectives of children and parents on the family court welfare service. Policy.

- Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., & Di Blasio, P. (2019). Children’s triangulation during inter-parental conflict: Which role for maternal and paternal parenting stress? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(6), 1623–1634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01380-1

- Cashmore, J. A., & Parkinson, P. N. (2011). Reasons for disputes in high conflict families. Journal of Family Studies, 17(3), 186–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2011.17.3.186

- Child Welfare Act. (1992). Child Welfare Act (Lov-1992-07-17-100). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1992-07-17-100?q=Barnevernloven

- Children Act. (1981). The Children Act (LOV-1981-04-08-7). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1981-04-08-7?q=Lov%20om%20barn%20og%20foreldre

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2018). Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(2), 107–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12165

- Devaney, J., & Spratt, T. (2009). Child abuse as a complex and wicked problem: Reflecting on policy developments in the United Kingdom in working with children and families with multiple problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(6), 635–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.12.003

- Dingwall, R., Eekelaar, J., & Murray, T. (2014). The protection of children: State intervention and family life (Vol. 16). Quid Pro Books.

- Family Councelor Services Act. (1997). Family Councelor Services Act (LOV-1997-06-19-62). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1997-06-19-62?q=Lov%20om%20familievernkontor

- Garber, B. D. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral methods in high-conflict divorce: Systematic desensitization adapted to parent–child reunification interventions. Family Court Review, 53(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12133

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (2011). Child protection systems: International trends and orientations. Oxford University Press.

- Grych, J. H. (2005). Interparental conflict as risk factor for child maladjustment. Familiy Court Review, 43, 22–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00010.x/epdf

- Halkier, B. (2010). Focus groups as social enactments: Integrating interaction and content in the analysis of focus group data. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348683

- Heggdalsvik, I. K. (2020). Fastlåste foreldrekonflikter. En analyse av familieterapeuters skjønnsutøvelse i saker med høy konflikt (Deadlocked parental conflicts. An analysis of family therapist’s discretionary practice in high conflict cases). Fokus på Familien, 48(2), 74–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.0807-7487-2020-02-02

- Horwath, J. (2007). The missing assessment domain: Personal, professional and organizational factors influencing professional judgements when identifying and referring child neglect. British Journal of Social Work, 37(8), 1285–1303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl029

- Houston, C., Bala, N., & Saini, M. (2017). Crossover cases of high‐conflict families involving child protection services: Ontario research findings and suggestions for good practices. Family Court Review, 55(3), 362–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12289

- Jevne, K. S., & Andenaes, A. (2015). Parents in high-conflict custodial cases: Negotiating shared care across households. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 296–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12240

- Johnsen, I. O., Litland, A. S., & Hallström, I. K. (2018). Living in two worlds—Children’s experiences after their parents’ divorce—A qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 43, e44–e51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.09.003

- Johnston, J. R., Roseby, V., & Kuehnle, K. (2009). In the name of the child: A developmental approach to understanding and helping children of conflicted and violent divorce. Springer Publishing Company.

- Joyce, A. N. (2016). High-conflict divorce: A form of child neglect. Family Court Review, 54(4), 642–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12249

- Justesen, L. N., & Mik-Meyer, N. (2012). Qualitative research methods in organisation studies. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Kåstad, H., Halvorsen, K., & Samsonsen, V. (2021). Standardisering og profesjonelt skjønn i høykonfliktmekling. En kvalitativ undersøkelse av mekleres erfaringer med prosessmeklling i høykonfliktsaker. (Standardization and professional discretion in high-conflict mediation. A qualitative study of mediators’ experiences with process mediation in high-conflict cases). Fokus på Familien (in Press), 48(4), 285–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.0807-7487-2021-04-04

- Khoo, E. G. (2004). Protecting our children: A comparative study of the dynamics of structure, intervention and their interplay in Swedish child welfare and Canadian child protection [Doctoral dissertation]. Umeå University.

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 311(7000), 299–302. http://search.proquest.com/docview/203996599?accountid=15685

- Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta‐analytic review. Family Relations, 49(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x

- Levi, B. H., & Crowell, K. (2011). Child abuse experts disagree about the threshold for mandated reporting. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(4), 321–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922810389170

- Lonne, B., Harries, M., Featherstone, B., & Gray, M. (2015). Working ethically in child protection. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315851020

- Mutchler, M. S. (2017). Family counseling with high-conflict separated parents: Challenges and strategies. The Family Journal, 25(4), 368–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480717731346

- Polak, S., & Saini, M. (2019). The complexity of families involved in high-conflict disputes: A postseparation ecological transactional framework. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 60(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2018.1488114

- Reynolds, J., Houlston, C., Coleman, L., & Harold, G. (2014). Parental conflict: Outcomes and interventions for children and families. Policy Press.

- Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Saini, M., Black, T., Godbout, E., & Deljavan, S. (2019). Feeling the pressure to take sides: A survey of child protection workers’ experiences about responding to allegations of child maltreatment within the context of child custody disputes. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 127–133. https://www-sciencedirect-com.galanga.hvl.no/science/article/pii/S0190740918301907

- Saini, M., Black, T., Lwin, K., Marshall, A., Fallon, B., & Goodman, D. (2012). Child protection workers’ experiences of working with high-conflict separating families. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(7), 1309–1316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.03.005

- Samsonsen, V., Heggdalsvik, I. K., & Iversen, A. C. (2022). Samarbeidsutfordringer mellom familievern og barneverntjenester i saker med høy grad av foreldrekonflikt—en kvalitativ studie (Collaborating challenges between family counseling services and child welfare services in high conflict cases-a qualitative study). In Under review.

- Samsonsen, V. (2016). Assessment in child protection: A comparative study Norway-England [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Stavanger.

- Sheehan, J. (2018). Family conflict after separation and divorce: Mental health professional interventions in changing societies. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Shumaker, D., & Kelsey, C. (2020). The existential impact of high-conflict divorce on children. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 19(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2020.1717985

- Statistics Norway. (2021a). Barnevern (Child Welfare) [Norwegian National Statistics]. Statistisk sentralbyrå. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/10674/tableViewLayout1/

- Statistics Norway. (2021b). Familievern (Family Counseling) [Norwegian National Statistics]. Statistisk sentralbyrå. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/10529/tableViewLayout1/

- Stokkebekk, J., Iversen, A., Hollekim, R., & Ness, O. (2021). "The troublesome other and I": Parallel stories of separated parents in prolonged conflicts”. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 47(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12474 s

- Sudland, C. (2019). Challenges and dilemmas working with high‐conflict families in child protection casework. Child & Family Social Work, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12680

- Sudland, C., & Neumann, C. B. (2020). Should we take their children? Caseworkers’ negotiations of “good enough” care for children living with high-conflict parents: Skal vi ta barna? Barnevernansattes forhandlinger om «god nok omsorg» i saker med fastlåste foreldrekonflikter. European Journal of Social Work, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1805588

- van Dijk, R., van der Valk, I. E., Deković, M., & Branje, S. (2020). A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: Examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clinical Psychology Review, 79, 101861 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101861

- Van Lawick, J., & Visser, M. (2015). No kids in the middle: Dialogical and creative work with parents and children in the context of high conflict divorces. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 36(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1091