Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic exposures that can derail child health and development. This quality improvement intervention implemented and evaluated a process to adopt ACEs screening in five New Hampshire pediatric primary care clinics. Clinics received support including coaching, training, and tools to plan and pilot ACEs screening over a 15-month period. Despite the co-occurring COVID-19 pandemic, the five clinics conducted 1195 screens with 142 (12%) families indicating a level of risk. Significant increases in clinician knowledge and confidence with these screening and response processes were noted. Increases in clinic self-assessment scores were observed. Lessons learned included shortening the intervention period to 12 months and the importance of building local referral relationships. Recommendations for advancing ACEs screening are offered.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are events in childhood, including physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, that can have lasting negative effects (Harvard University Center for the Developing Child, Citation2023). In 2020, nearly 60% of US adults reported having at least one ACE (Giano et al., Citation2020). In 2017, just under half of US children (0–17 years) had at least one ACE (Bethell et al., Citation2017). Research has demonstrated that ACEs can have significant short and long-term effects on the health and well-being of children and adolescents (Oh et al., Citation2018). Additional studies have found that when children are exposed to adverse experiences (such as abuse, parental substance use, and incarceration), a child’s stress response system is activated. If this activation is prolonged and excessive, it can derail healthy development, a phenomenon referred to as toxic stress (Garner & Yogman, Citation2021).

Resilience is defined as the “capacity of a system (family) to adapt successfully to challenges that threaten the function, survival, or future development of the system” (Masten & Barnes, Citation2018, p. 1). Recent literature has examined the concept of resilience as defined by positive childhood experiences (PCEs) as a “buffer” to the effects of adverse experiences (Bethell et al., Citation2014, Citation2019). PCEs are supportive attributes such as relationships, a safe living environment, community/family engagement, and opportunities for social and emotional growth that build resilience (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences, Citation2022; Sege & Harper Browne, Citation2017). Assessing family strengths along with ACEs provides the opportunity to recognize family strengths and factor in their impact to mitigate ACEs (Burstein et al., Citation2021).

Pediatric primary care clinicians are trusted sources of information and support for many families (American Academy of Pediatrics, Citation2014; Conn et al., Citation2018; Gillespie, Citation2019). In 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released its updated statement on childhood toxic stress, which advocated for its membership to promote family relational health using primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions, including identification and resolution of family adversities. Primary prevention focuses on how to “universally promote the development and maintenance of nurturing relationships.” Secondary interventions include developing “respectful and caring therapeutic relationships with patients, families, and communities.” Tertiary prevention focuses on the use of evidence-based practices that “repair strained relationships and assist them in becoming more safe, stable, and nurturing” (Garner & Yogman, Citation2021, p. 3).

Previous research has identified numerous barriers to screening for ACEs in pediatric primary care including lack of time, family and clinician discomfort with screening, limited clinician knowledge about ACEs, and lack of referral resources (Barnes et al., Citation2020; Corvini et al., Citation2018; Kerker et al., Citation2016; Rariden et al., Citation2021; Sherfinski et al., Citation2021). A 2017 literature review found a lack of research evaluating outcomes of trauma-informed care in primary care (Mace & Smith, Citation2017). Knowledge gaps in how to execute trauma-informed care in primary care settings (for example, do paper-based screening or provider-patient discussions work better to identify trauma) were also noted (Mace & Smith, Citation2017). A study conducted in 2018 by paper authors found similar results. The study consisted of the following (Corvini et al., Citation2018):

a review of four databases of peer-reviewed literature

a search of national physician association recommendations and relevant grey literature

key informant interviews with primary care, trauma, and behavioral health clinicians as well as policy makers across NH

In addition to the gaps noted in the 2017 study, our research team identified other challenges including (but not limited to): limited psychometric testing of screening tools, lack of evidence on addressing trauma with persons from diverse cultures, and limited awareness of local referral resources (Corvini et al., Citation2018). A more recent literature review has summarized the experiences of single clinics in operationalizing childhood adversity screening (Rariden et al., Citation2021). However, the diversity of approaches, clinic settings, populations screened, and small sample sizes limited the study’s ability to make generalizable recommendations for screening (Rariden et al., Citation2021). This current study provides a novel opportunity to garner lessons learned about how to execute a single, flexible intervention model built on quality improvement principles to support childhood adversity screening in a range of pediatric primary care settings. The development and diffusion of an effective screening model could facilitate increased adoption of ACEs screening.

New Hampshire (NH) is a small state located in the northeast part of the United States (US). The state is predominantly White but is experiencing an increase in population diversity (Johnson, Citation2021). Though state-level household income is higher than the national average ($77,923 versus $64,994 in 2020) (US Census Bureau, Citationn.d.), significant intrastate variation exists. Four target communities within three counties, one urban and three rural as defined by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), were initially selected for this intervention due to their higher-risk socioeconomic profiles (Health Resources and Services Administration, Citation2022).

Current study

The goal of this intervention was to lead four NH pediatric primary care clinics in using principles of quality improvement, systems thinking, and trauma-informed care to implement a process to detect and respond to childhood toxic stress. The evaluation plan included process measures to assess how well intervention activities were implemented and valued by clinic teams. Outcomes measures focused on the extent to which clinics changed their care processes and systems to screen for and respond to ACEs, including three screening workflow performance metrics. The intervention implementation team consisted of two intervention coaches, a research associate, an intervention manager, the state pediatric quality improvement partnership director, and two co-Principal Investigators. External consultants included a social worker, a psychiatrist and a psychologist from a local trauma research center, and a national pediatrician expert on childhood adversity screening.

Method

Intervention design

Recruitment

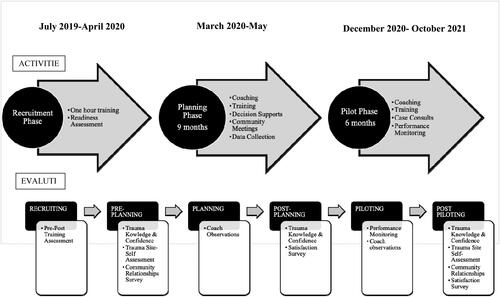

The intervention was conducted in three phases: recruitment, planning, and piloting (). The recruitment phase commenced with one-hour, on-site trainings to increase awareness of the impacts of childhood adversity and its manifestations in the pediatric primary care setting. The training was offered at three pediatric and/or family practice clinics per target community. Trainers included a behavioral health clinician from a local trauma research center and an intervention staff member. After each training, clinics were invited to participate in a quality improvement (QI) intervention to integrate childhood adversity screening into their clinical care workflows. Interested clinics submitted a short readiness assessment with a goal of recruiting one clinic per community to participate in the QI intervention.

Planning

Recruited practices were guided through a 15-month QI intervention to integrate ACEs screening into care delivery. During the planning phase, each clinic set up a team to meet with the intervention coach monthly. Using the practice guide developed to assist practices with implementation, coaches facilitated the team through a stepwise process to develop a screening and response workflow tailored to the clinic’s preferences and capacity. The coaches also arranged meetings of the clinic team with key referral resources including the local community mental health center, family resource center, domestic violence shelter/coalition, and community action program. These meetings sought to increase clinic team knowledge of, and relationship with, local referral partners. From these meetings, intervention staff created a referral contact list.

Piloting

During the piloting phase, clinic teams with the support of their coach conducted iterative Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to refine their screening workflows. Additional trainings were offered on the topics of building a staff culture that promotes resilience, engaging with families about childhood adversity, and learning from another clinic who had been doing this work for five years already. Clinician-to-clinician patient consults with psychiatric/trauma experts were also provided. Post-intervention, staff provided clinicians with documentation to support application for Maintenance of Certification Part Four credits.

Several modifications to the intervention design were made over time. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, monthly coaching sessions were delivered virtually. Clinic-community referral organization meetings were enhanced by a higher level of coach facilitation to identify collaborative opportunities to meet family needs. In total, 21 conversations were held.

Three additional intervention supports were developed to address clinic team needs. First, intervention staff created an Excel-based screening selection tool to assist teams in choosing screening instruments based on clinic preferences (completion time, cost, etc.). Second, an Excel-based registry was developed to collect performance metric data as some teams were unable to make modifications to their electronic health record (EHR) system in the needed time frame, and one clinic did not have an EHR. Third, a risk stratification tool () was developed based on ACEs score, protective factors (or PCEs), and clinician judgment to determine the appropriate family risk classification (low, medium, and high). Clinician judgment was used to categorize the screen as positive or negative. For example, a family that had a high ACE score but was already receiving services to address family concerns, based on clinician discretion, could be coded as a negative result. Based on family risk score, the clinician could identify evidence-based interventions to develop a treatment plan. The risk stratification tool facilitated consistent scoring and treatment responses within and between clinics.

Table 1. Risk categorization classification.

Evaluation and analysis

The study’s evaluation plan used a mixed-methods design incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data. Outcome measures assessed changes in clinician knowledge of and confidence in assessing ACEs and clinic screening workflow results. Process measures assessed intervention participation, satisfaction, and changes in clinician and clinic capacity to deliver trauma-informed care. A balancing measure to determine any unintended consequences of the screening intervention was also implemented. Qualitative data was collected during the planning and piloting phases to understand clinic experiences with developing the screening intervention, relationships with community referral resources, and clinic systems to support trauma-informed care delivery.

Outcome measures

Three performance metrics were used to evaluate the results of the screening intervention. They included: (1) number and percent of eligible patients assessed for ACEs, (2) number and percent of patients with a positive screening result, and (3) number and percent of patients with a positive screening result and a documented referral for services. For the last metric, referral organization was also collected. The number and percent of eligible patients who declined screening and the reason for decline was also recorded.

Coaches worked with each clinic team to identify how performance metric data would be collected (e.g., through electronic health record, manually via a registry). Teams submitted de-identified performance data monthly via an Excel registry. One coach then conducted quality assurance reviews and followed up with clinics about data issues. Each clinic received a monthly run chart displaying their clinic’s performance metrics results. Performance metric data from the five clinics was also aggregated to look at overall intervention performance.

Process measures

Participation in and satisfaction with the Trauma 101 trainings offered during the recruitment phase, as well as the advanced trauma trainings during the planning and piloting phases, were assessed via attendance records, evaluation questions required for continuing education credits, and pre-post knowledge change questions. For the Trauma 101 training, a set of five pre-post questions was developed to determine changes in trauma knowledge (Appendix A). For the intervention, a separate set of eight knowledge and seven confidence questions about addressing childhood adversity and building resilience was developed (Appendix B). For both the knowledge and confidence questions, a 0–4 Likert scale was used. Knowledge and confidence questions were sent to clinicians before, during, and after the intervention. For both sets of questions, clinicians were instructed to use a unique identifier to facilitate a matched analysis. Due to inconsistencies with unique identifier use, matched analysis was not feasible for either assessment. For the training assessments, results were analyzed in aggregate by the percent change of participants that answered the question correctly in the pre-assessment compared to the post-assessment (Appendix A for training results). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) of average total point score differences for both the knowledge and confidence questions sets was conducted. If the ANOVA test was significant at a p-value of .05 or less, then Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference Test was applied to verify statistical significance of results.

Each clinic team completed the “Organizational Self-Assessment: Adoption of Trauma-Informed Care Practice” (OSA) tool prior to starting the planning phase and then again after the piloting phase to gauge clinic capacity to deliver trauma-informed care (National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Citation2021). This tool includes the following domains: Screening and Assessment, Workforce Development, Safe Environments, and Data Collection/Performance Improvement. Each domain was scored independently using the average of reported scores over the total possible score. A two-sample independent test of pre-post differences in total self-assessment average total point score was conducted. If the two-sample independent test was significant, Welch’s test was used to account for unequal variances to confirm significance results. In addition to the self-assessment, each clinic team also completed a two-question survey assessing clinic relationship with local referral agencies. Inconsistencies in clinic team completion of this survey precluded pre-post analysis of relationship changes over the course of the intervention.

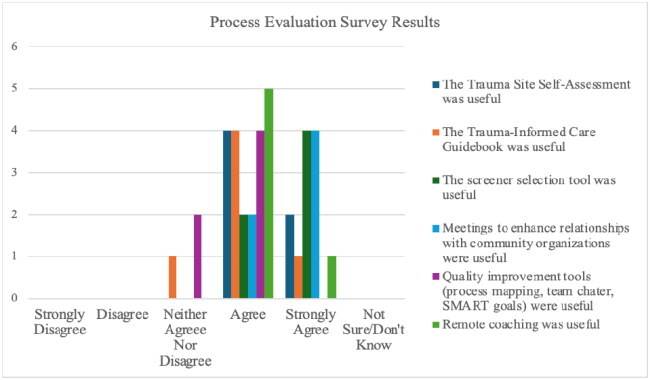

Clinic teams’ use of and satisfaction with intervention supports (e.g., the practice guide, coaching, etc.) and the overall process of implementation were collected by online surveys after the planning phase and again after the piloting phase (Appendix C) using a five-point Likert scale. The post-pilot survey also included the balancing measure the effect of screening on visit length to determine if screening was perceived to have had any adverse impact on care delivery.

Qualitative data

To complement the quantitative data, coaches also systematically collected observations about clinic team progress from monthly team meetings and meetings with community referral organizations. These data, such as team size and composition, factors impacting selection of the screening tools and visits, and challenges and benefits encountered, were used to understand clinic experiences throughout the intervention. Qualitative observations underwent a framework analysis to develop a coding scheme to identify themes. Two-person inductive coding was utilized to decrease the effect of coder bias and increase inter-rater reliability of coding. Qualitative analysis software was utilized to perform content analysis.

A visual representation of evaluation methods and their use across the intervention timeframe is included in . Institutional Review Board (IRB) documents for this intervention were submitted to and approved by the University of New Hampshire IRB.

Results

Intervention participation

Four clinics from the three initial target communities plus one clinic from another community chose to participate in the QI intervention. Of the five participating clinics (), three completed the QI intervention in 15 months while two completed it in 12 months due to their later recruitment. Clinic team size ranged from two to eleven. Team composition ranged from a nurse and medical assistant only to pediatricians, clinical coordinator, behavioral health clinician, nurse, and practice manager. Prior to the intervention, no clinics screened for ACEs.

Table 2. Clinic characteristics.

Outcomes

The most frequently selected screening tool was the Pediatric ACEs and Related Life-events Screener (PEARLS) followed by the Childhood Trauma Screen (ACEs Aware, Citation2023b; Lang & Connell, Citation2017). The PEARLS can be conducted in two ways: reporting only the number of exposures or identifying specific exposure along with the number. The clinics in this study used the former as this approach supports patient/family willingness to share information and thus more accurate reporting (ACEs Aware, Citation2023a). In addition, three clinics incorporated a two-question trauma screen for all visits or on an as-needed basis that asked if anyone hurt or frightened you or your child and if anything bad, sad, or scary happened. Incorporating a specific resilience screening tool proved challenging as current tools were either too long or not designed for application in a clinical care setting. Clinic teams, therefore, incorporated discussions about resilience alongside ACEs screening. All clinics opted to start screening at the four-month well-child visit with a parental ACEs screen. Subsequent screening of the child during the toddler, pre-school, elementary, and adolescent ages was performed ().

Table 3. Screens and well-child visits selected.

As shown in , 1195 screens were attempted across the five clinics. Of these, 46 families declined participation leading to a screening decline rate of 4% (46/1195). The most common documented reason for decline was “caregiver/patient not interested”. A few anecdotal instances of family discomfort with screening were reported; however, there were no observed instances of this leading to an escalated behavioral response. 35% of the screenings were conducted at an infant/toddler well-child visit, 23% were conducted at an elementary age visit, and 21% were conducted at both the preschool and adolescent well-child visits. Screening rates could not be computed as clinics were unable to provide accurate counts of populations eligible for screening.

Table 4. Screens conducted.

As indicated in , roughly 12% (N = 142) of screens were identified by a provider as having a positive result. Approximately 5% of screens were scored as high-risk and 8% as moderate risk. Of the 142 screens with a positive result, referral status was captured for 132. Approximately, 11% of patients/families were referred for services. 39% Were referred to an internal or external behavioral health resource, 35% declined the referral, and 22% were already receiving services from the referral agency. Of those declining services, 35% were adolescent patients and 26% were caregivers screened at infant/toddler visits. All clinics reported overall family acceptance of screening, with some reporting family appreciation of clinicians for asking these questions. No clinic teams indicated that screening lengthened the well-child visit.

Table 5. Results and referrals.

Process measures

Clinician knowledge of and confidence in delivering trauma-informed care improved over the intervention period (). From pre-planning to post-planning, the mean clinician knowledge score increased 8.7 points, a statistically significant difference at an alpha level of 0.05 (p<.004). From post-planning to post-pilot, the mean clinician knowledge score increased another 6.6 points, which was not statistically significant (p<.089). Mean clinician confidence score in delivering trauma-informed care increased 6.8 points, a statistically significant change (p<.014). From post-planning to post-pilot, the mean clinician confidence score increased another 4.2 points, which was not statistically significant (p<.283). Improvements in trauma-informed care Organizational Self-Assessment (OSA) scores were also observed for each clinic. From pre-intervention to post-pilot, clinics improved their trauma OSA scores on average 17.5 points, a statistically significant change (p<.0001).

Table 6. Clinician knowledge and confidence.

Process evaluation results yielded high clinic team satisfaction with coaching, tools, trainings, and meetings with local referral resources. Satisfaction scores, as measured by percent of respondents who indicated being very or somewhat satisfied with the various tools, ranged from 82 to 100% (Appendix C). During this study, seven clinician-to-clinician patient consults were conducted, but no completed post-consult evaluation surveys were received. Likewise, pre-post analysis of current communication and relationships with community referral resources was limited due to low response.

Qualitative findings

Qualitative data revealed important contextual insights about clinic experience during this intervention. Clinics experienced a variety of internal and external challenges over the course of this intervention, including an EHR conversion, an office move, clinician turnover, and a lengthy approval process to participate. All clinics were constantly changing office operations to respond to local pandemic conditions, leading to ever-changing care workflows and heightened staff stress. Intervention coaches proved critical to supporting and encouraging teams through challenging times.

Qualitative data identified factors impacting clinic decision-making about screening tools and visits. Cost and time to complete the screener were identified as the two most important criteria for tool selection. At the recommendation of a national pediatrician expert in childhood adversity, all clinics began by screening for parental ACEs at the four-month well-child visit due to being free of competing priorities, thus allowing time for screening and follow-up conversations with parents. Screening at this visit also provided the opportunity for clinicians and parents to proactively discuss factors that could impact the development of a “safe, stable, and nurturing relationship” between parent and child (Garner & Saul, Citation2018; Garner & Yogman, Citation2021). Criteria for selection of subsequent screening visits included spacing of screening at key developmental time points and avoiding visits with other required screening or immunizations.

Across all clinics, data collection challenges were encountered including difficulties using EHRs for performance data collection and limited time for manual data entry. The latter led to one clinic submitting only five months of performance data. In one clinic, referrals were completed by an off-site department, which precluded collection of places of referral. Determining the number of screening-eligible patients proved problematic. Near intervention completion, one clinic piloted use of billing data to obtain screening-eligible patients, which proved effective.

Clinic teams reported unanticipated benefits from participation in the study. For example, one clinic reported that the intervention helped to build clinic team resilience alongside family resilience during the pandemic. As stated by a clinician from this clinic, “We helped the families, and we helped ourselves.” Another clinic noted that staff had been wanting to implement childhood adversity screening but were too overwhelmed to initiate it on their own. This intervention provided the supportive pathway needed. Clinicians across clinics consistently indicated that screening opened opportunities for conversations with patients and their families about previously unknown life circumstances. As one clinician noted, “The tools we are using give us important information that we would not have had before and are important in catching the trauma in people you wouldn’t expect.”

While encouraged to collect patient feedback, no clinic instituted a formal process for collecting family experience. No negative family reactions to the screening tool or process were noted. Of note, one clinic provider reported anecdotally that a patient remarked on the clinic’s social media page, “I love that they are doing this screening. They are so cutting edge.”

Discussion

This project focused on building pediatric primary care clinician knowledge about childhood adversity and piloting a QI intervention to support five pediatric primary care clinics in screening for childhood adversity and/or trauma. All five clinics successfully integrated childhood adversity screening and response into selected well-child visits, screening nearly 1,200 children and teens with no negative effects on visit length or family engagement. Increases in clinician knowledge and confidence, as well as clinic capacity to deliver trauma-informed care, were observed.

Similar to previous studies, approximately 12% of screens done in this intervention yielded a risk result (Bethell et al., Citation2014; Marsicek et al., Citation2019). Two previous screening studies yielded a higher percentage of positive screens (23%); however, these clinics served more ethnically diverse, low-income populations (Crenshaw et al., Citation2021; Kia-Keating et al., Citation2019). Like one other screening study (Crenshaw et al., Citation2021), this intervention experienced a low rate of screenings declined (4%). Approximately 11% of all screens conducted led to a referral. Only one previous study collected referral data in response to ACEs screening (Crenshaw et al., Citation2021); however, the definition of “referral” was structured differently precluding comparison. The relatively low referral rate may indicate that clinicians themselves were able to address adversity concerns during the visit. Consistent with existing literature, families in this study were supportive of ACEs screening in primary care (Conn et al., Citation2018; Crenshaw et al., Citation2021; Gilgoff et al., Citation2020; Gillespie & Folger, Citation2017; Goldstein et al., Citation2017), and screening did not elongate patient visits (Crenshaw et al., Citation2021; Gillespie & Folger, Citation2017; Rariden et al., Citation2021).

Study results suggest that successful clinic adoption of adversity screening required an interconnected array of supports and a multi-disciplinary approach. Coaches provided the needed technical assistance and “nudging” to support team momentum. Brief trainings on “real-world” screening challenges, such as how to talk with families about childhood adversity, helped to support clinician knowledge and confidence in screening for and responding to trauma. Decision and data collection aids such as a practice guide, screener selection, risk stratification, and registry tools were integral as well. Connecting clinic teams with internal and external multi-disciplinary supports to address family needs was critical so clinicians did not have to shoulder the entire burden. Clinic teams were encouraged to identify and include on their team internal organizational staff from all departments/disciplines touching the clinical care process including front desk, medical assistants, case managers/patient facilitators, and behavioral health consultants. Meetings with key local referral agencies improved team (and, in particular, clinician) understanding of the array of family supports available and comfort with referring to them. As one clinician remarked,

The number one eye-opening experience about this whole thing is that we are learning about resources in the community that we have never known before. I have already started utilizing a lot of that…we have a lot more specific information that we can do on our end to help patients get connected to help.

Strategies to enhance intervention efficiency were also identified. First, shortening the intervention to 12 months (six months of planning followed by six months of piloting) proved feasible. A shorter time commitment might encourage clinic participation. Second, initial in-person contact with the clinic team followed by virtual coaching worked well. Third, a low number of clinician-to-clinician consults were requested, suggesting an opportunity to reduce resources allocated for this support. Fourth, performance metric data collection was more challenging than anticipated. Using clinic billing data to obtain denominators for computing screening rates is recommended. Fifth, opportunities to decrease evaluation burden were identified. For example, reducing the number of times that clinicians completed the knowledge and confidence questions from three to two times (pre- planning and post-pilot only) as score changes from post-planning to post-pilot were small.

Based on study results, the below key recommendations for clinics/clinicians interested in screening for ACEs are offered. First, spend sufficient time and take advantage of existing tools to develop an ACEs and resilience screening workflow customized to your clinic capacity and preferences. Unlike many other screening processes, no standardized guidelines for ACEs screening exist. Developing a screening process that fits clinic capacity is paramount to success. Of note, all resources used in this intervention are publicly available at www.nhpip.org. Second, spend time training all staff (front desk, case managers, and clinical staff) in principles of trauma-informed care. All staff need to understand what ACEs are and the principles of trauma-informed care for their role-specific responsibilities. For example, front desk staff must be comfortable answering family questions about the screening. Clinicians need to be comfortable engaging with families and patients about toxic stress and identifying next steps based on screen results. Third, thoroughly understand the internal and external family support resources available to prevent and/or address the effects of toxic stress as addressing ACEs requires a multi-disciplinary, team-based approach.

This study also identified recommendations for additional research in implementation, process, and tools. The co-occurring COVID-19 pandemic altered intervention delivery and clinic capacity; thus, replication research is warranted. Other topics for further study include use of billing data for screening denominators, screeners in additional languages, in-person and virtual interpretation, pilot strategies to systematically collect family feedback about the screening process and supports necessary for clinics to sustain screening.

Broader topics needing further research include the distribution of different types of ACEs overall and by age as well as research examining the effect of ACEs screening on family functioning and child health. Further study is needed on how to effectively assess family resilience. When this intervention began, existing resilience screeners were too long or did not provide actionable data. Resilience screens and questions adapted for use in primary care are now available (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences, Citation2021), as are examples of how clinicians have used these results to engage families in conversations to prevent and/or mitigate the effects of childhood adversity (Gillespie & Folger, Citation2017; Sege, Citation2021; Sege & Harper Browne, Citation2017). Conducting research on the effectiveness of using PCE screening to gauge family resilience is merited.

Intervention limitations must be considered. Though a variety of clinic types and sizes participated in this intervention, clinician and patient populations were predominantly White. Families of diverse racial, ethnic, and family composition may experience different types of traumatic exposures and may require customizing language and approach to accommodate these differences (Corvini et al., Citation2018). Accurate counts of eligible visits for screening proved problematic for all clinics. Considering the busy nature of primary care practices, it is also possible that not all screen results were entered into practice registries. Despite retention efforts, participation in evaluation surveys decreased over the intervention duration, which precluded analysis of some process measures.

Conclusions

This intervention demonstrates that screening for ACEs in a dynamic pediatric primary care setting is feasible. Learnings from this study and other ACEs screening efforts need to be synthesized into a best practice model that can be promulgated. The research team is currently replicating this intervention with a second cohort of clinics based on learning from this cohort, as well as interviewing team leads from the five clinics in this first cohort to understand if and how they are sustaining and/or expanding screening as well as identifying additional support needs. Given the anticipated “ripple effects” of the COVID-19 pandemic on families, identifying best practices for supporting pediatric primary care clinics in conducting childhood adversity screening is crucial.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACEs Aware. (2023a). Clinical assessment & treatment. https://www.acesaware.org/acefundamentals/clinical-assessment-and-treatment/

- ACEs Aware. (2023b). Pediatric ACEs and related life events screener. https://www.acesaware.org/learn-about-screening/screening-tools/

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2014). The medical home approach to identifying and responding to exposure to trauma. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Barnes, A. J., Anthony, B. J., Karatekin, C., Lingras, K. A., Mercado, R., & Thompson, L. A. (2020). Identifying adverse childhood experiences in pediatrics to prevent chronic health conditions. Pediatric Research, 87(2), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0613-3

- Bethell, C., Newacheck, P., Hawes, E., & Halfon, N. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106–2115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914

- Bethell, C., Davis, M., Gombojav, N., Stumbo, S., & Powers, K. (2017). A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive [Issue Brief]. https://www.cahmi.org/projects/adverse-childhood-experiences-aces.

- Bethell, C., Jones, J., Gombojav, N., Linkenbach, J., & Sege, R. (2019). Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: Associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(11), e193007. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007

- Burstein, D., Yang, C., Johnson, K., Linkenbach, J., & Sege, R. (2021). Transforming practice with HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences). Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(7), 1019–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03173-9

- Conn, A.-M., Szilagyi, M. A., Jee, S. H., Manly, J. T., Briggs, R., & Szilagyi, P. G. (2018). Parental perspectives of screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care. Families, Systems, & Health, 36(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000311

- Corvini, M., Cox, K., O’Neil, M., Ryer, J., & Tutko, H. D. (2018). Addressing childhood adversity and social determinants in pediatric primary care: Recommendations for New Hampshire. UNH Institute for Health Policy and Practice. https://www.nhpip.org/sites/default/files/media/2021-10/nh-aces-report-final-july-2018.pdf.

- Crenshaw, M. M., Owens, C. R., Dow-Smith, C., Olm-Shipman, C., & Monroe, R. T. (2021). Lessons learned from a quality improvement initiative: Adverse childhood experiences screening in a pediatric clinic. Pediatric Quality & Safety, 6(6), e482. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000482

- Garner, A., & Saul, R. (2018). Thinking developmentally: Nurturing wellness in childhood to promote lifelong health. American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Garner, A., & Yogman, M. (2021). Preventing childhood toxic stress: Partnering with families and communities to promote relational health. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052582. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052582

- Giano, Z., Wheeler, D. L., & Hubach, R. D. (2020). The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1327. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09411-z

- Gilgoff, R., Singh, L., Koita, K., Gentile, B., & Marques, S. S. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, outcomes, and interventions. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 67(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.001

- Gillespie, R. J. (2019). Screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care: Pitfalls and possibilities. Pediatric Annals, 48(7), e257–e261. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20190610-02

- Gillespie, R. J., & Folger, A. T. (2017). Feasibility of assessing parental ACEs in pediatric primary care: Implications for practice-based implementation. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0138-z

- Goldstein, E., Athale, N., Sciolla, A. F., & Catz, S. L. (2017). Patient preferences for discussing childhood trauma in primary care. The Permanente Journal, 21, 16–055. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-055

- Harvard University Center for the Developing Child. (2023). ACEs and toxic stress. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/aces-and-toxic-stress-frequently-asked-questions/#graphic-text.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2022, March). Defining rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/what-is-rural.

- Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences. (2022). Four building blocks of HOPE. https://positiveexperience.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/The-Four-Building-Blocks-of-HOPE-1.pdf.

- Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences. (2021). Four ways to assess positive childhood experiences. https://positiveexperience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Four-Ways-to-Access-Positive-Childhood-Experiences.pdf.

- Johnson, K. (2021). Modest population gains, but growing diversity in New Hampshire with children in the Vanguard. University of New Hampshire.

- Kerker, B. D., Storfer-Isser, A., Szilagyi, M., Stein, R. E. K., Garner, A. S., O’Connor, K. G., Hoagwood, K. E., & Horwitz, S. M. (2016). Do pediatricians ask about adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care? Academic Pediatrics, 16(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.002

- Kia-Keating, M., Barnett, M. L., Liu, S. R., Sims, G. M., & Ruth, A. B. (2019). Trauma-responsive care in a pediatric setting: Feasibility and acceptability of screening for adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12366

- Lang, J. M., & Connell, C. M. (2017). Development and validation of a brief trauma screening measure for children: The Child Trauma Screen. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(3), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000235

- Mace, S., & Smith, R. (2017). Trauma-informed care in primary care: A literature review. National Council for Behavioral Health. https://www.nationalcouncildocs.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Trauma-Informed-Care-for-Primary-Care-Literature-Review.pdf.

- Marsicek, S. M., Morrison, J. M., Manikonda, N., O’Halleran, M., Spoehr-Labutta, Z., & Brinn, M. (2019). Implementing standardized screening for adverse childhood experiences in a pediatric resident continuity clinic. Pediatric Quality & Safety, 4(2), e154. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000154

- Masten, A. S., & Barnes, A. J. (2018). Resilience in children: Developmental perspectives. Children, 5(7), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070098

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. (2021). Organizational self-assessment: Adoption of trauma informed care practice. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/

- Oh, D. L., Jerman, P., Silvério Marques, S., Koita, K., Purewal Boparai, S. K., Burke Harris, N., & Bucci, M. (2018). Systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with childhood adversity. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1037-7

- Rariden, C., SmithBattle, L., Yoo, J. H., Cibulka, N., & Loman, D. (2021). Screening for adverse childhood experiences: Literature review and practice implications. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.08.002

- Sege, R. D. (2021). Reasons for HOPE. Pediatrics, 147(5), e2020013987. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-013987

- Sege, R. D., & Harper Browne, C. (2017). Responding to ACEs with HOPE: Health outcomes from positive experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7S), S79–S85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.03.007

- Sherfinski, H. T., Condit, P. E., Williams Al-Kharusy, S. S., & Moreno, M. A. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences: Perceptions, practices, and possibilities. WMJ, 120(3), 209–217.

- US Census Bureau. (n.d.). Quick facts; New Hampshire, US. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US,NH/INC110220 (accessed July 13, 2022).

Appendix A:

Trauma 101 pre and post-survey and results

During the recruitment phase, twelve introductory-level trauma trainings were conducted in the four initial target communities. One additional training was conducted at another clinic outside the initial target communities. A total of 191 pediatric primary care clinicians and staff were trained. Roughly 60% of attendees were primary care clinicians and nurses while the remaining 40% were a mix of behavioral health clinicians, medical assistants, and front desk staff. Average pre-post score increased for three of the five questions assessing participant knowledge of childhood adversity.

Appendix B.

Clinician knowledge and confidence questions

Knowledge

The following set of questions are about your CURRENT knowledge levels in caring for families affected by toxic stress/trauma. Please indicate below which response best describes your current KNOWLEDGE level using the below Likert scale:

Not knowledgeable

Slightly knowledgeable

Fairly knowledgeable

Knowledgeable

Very knowledgeable

About what toxic stress is, risk factors, and effect on child physical and mental health

Trauma symptoms

Analyze and interpret results of a toxic stress/trauma screening tool

Analyze and interpret results of a resilience/strength screening tool

Evidence-based trauma interventions for children and teens

Determine next steps based on toxic stress/trauma screen results

Effectively conversing with families about sensitive or stigmatized aspects of the current or past family history

Anticipatory guidance relative to positive parenting techniques and family routines (e.g. shared meals, bedtime) that support socio-emotional development

Confidence

The following set of questions are about your CURRENT confidence level in caring for families affected by toxic stress/trauma. Please indicate below which response best describes your current CONFIDENCE level using the below Likert scale.

Completely lacking confidence

Somewhat lacking confidence

Neither lacking confidence nor confident

Somewhat confident

Completely confident

In your ability to describe toxic stress, its risk factors, and effect on child physical and mental health

In your ability to identify trauma symptoms

In your ability to analyze and interpret results of a toxic stress/trauma screening tool

In your ability to analyze and interpret results of a resilience/strength screening tool

In your ability to determine next steps based on toxic stress/trauma/resilience screen results

In your ability to effectively converse with families about sensitive or stigmatized aspects of their current or past family history

In your ability to provide anticipatory guidance relative to positive parenting techniques and family routines (e.g. shared meals, bedtime) that support socio-emotional development

Appendix C.

Trauma-informed care project post-planning and post-pilot evaluations

Post planning

Please indicate to what extent you agree or disagree with each of the following statements about the usefulness of supports provided during the planning phase of the Trauma-Informed Care in Pediatrics Project using the below Likert scale.

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Neither agree nor disagree

Agree

Strongly Agree

Not sure/Don’t know

Trauma Site Self-Assessment was useful

The Trauma-Informed Care Guidebook was useful

The screener selection tool was useful

Meetings to enhance relationships with community organizations were useful

Quality improvement tools (process mapping, team charter, SMART goals) were useful

Remote coaching was useful

Please indicate your level of satisfaction with the monthly facilitation provided during the planning phase.

Very satisfied

Somewhat satisfied

Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied

Somewhat dissatisfied

Very dissatisfied

Monthly facilitation was originally planned for in-person delivery, but due to COVID was changed to remote delivery via Zoom. Did the remote model affect your clinic’s ability to work with your coach to develop a workflow to assess and respond to ACEs?

Yes. Please explain ___________________

No. Please explain ___________________

Was the length of the planning phase.

Too long. Please explain _______________

Too short. Please explain _______________

Just right

Is there additional support that your practice would have appreciated while planning your workflow for assessing and responding to ACEs?

a. ____________________________________________________________

Please feel free to write below any comments or feedback about your clinic team’s experience with the planning phase of this project.

a. ____________________________________________________________

Post pilot

Please indicate to what extent you agree or disagree with each of the following statements about the usefulness of supports provided during the piloting phase of the Trauma-Informed Care in Pediatrics Project.

Remote coaching (monthly)

Not at all useful

Slightly useful

Moderately useful

Very useful

Extremely useful

Registry template (in Excel)

Not at all useful

Slightly useful

Moderately useful

Very useful

Extremely useful

Provider-to-provider consults with Dartmouth Trauma Interventions Research Center

Not at all useful

Slightly useful

Moderately useful

Very useful

Extremely useful

Was the length of the pilot phase…

Too long. Please explain _________________________

Too short. Please explain ________________________

Just right

Are there additional supports that your practice would have appreciated while piloting your workflow for assessing and responding to ACEs?

____________________________________________________________

Please feel free to write below any comments or feedback about your clinic team’s experience with the pilot phase of this project.

____________________________________________________________

After adding ACEs screening to a well-child visit, did the visit length

Become longer

Stay the same length

Did your clinic experience any unintended consequences due to integrating ACEs screening into well-child visits?

Yes. Please explain __________________________

No

What was the most challenging part of piloting your ACEs screening workflow?

____________________________________________________________

What was the most rewarding or beneficial aspect of adding ACEs screening?

____________________________________________________________

Does your clinic plan to continue screening for ACEs after this pilot?

Yes

No. Please explain ___________________________________________

How does your clinic plan to sustain ACEs screening? (check all that apply)

Continue to collect data to monitor screening workflow processes and results

Obtain patient feedback about the process

Integrate this QI effort into our clinic’s ongoing QI/QA efforts

Provide training on trauma-informed care, including when on-boarding new clinicians/staff

Integrating ACEs screening into current preventative screening processes (e.g. adding ACEs screening tool to list of screening tools/questions implemented during adolescent well-visits)

Develop a standard operating procedure for ACEs screening at our clinic

Do you have any plans for expanding ACEs screening at your clinic?

Yes, expanding screening to other clinic providers, pods, or sites

Yes, expanding screening to other ages of children/adolescents

Yes, other ______________________________________________

No