ABSTRACT

Previous work regarding Problematic Pornography Use (PPU) has been limited due to scales with weak statistical constructions, few female participants, reliance on an English-language-only sample, and/or the omission of potentially important co-variates. We tested the inter-relationships between adults’ PPU, scrupulosity, six subdimensions of experiential avoidance (EA), and Dark Tetrad personality traits (Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, subclinical sadism). Previous research, to our knowledge, has not yet considered subclinical sadism in this context. An online survey was completed by 672 volunteers (MAge=26.14 years, SDAge=8.33) in either the English or Spanish language. Reliable measures were used to evaluate co-variates. Analyses determined that total and sub-dimensional PPU was predicted by scrupulosity. Furthermore, PPU was predicted by certain sub-dimensions of EA (Behavioral Avoidance, Distress Aversion). Mediation analysis suggested four sub-dimensions of EA (Distress Aversion, Procrastination, Distraction/Suppression, and Repression/Denial) as mediators in the relationship between scrupulosity and PPU. Our research builds upon limited literature examining the impact of aversive personality traits on PPU. Our finding that PPU is positively predicted by vicarious sadism has implications for identification of at-risk individuals and can inform the development of interventions to mitigate PPU.

Introduction

Internet pornography use has increased exponentially over the past 20 years (Campbell & Kohut, Citation2017; Price, Patterson, Regnerus, & Walley, Citation2016). In only one year, the number of daily visits to PornHub (the largest pornography site online) rose from 81 million (Pornhub, Citation2018) to 115 million (Pornhub, Citation2019), and this ongoing growth significantly increased in countries affected by the COVID-19 lockdown (Mestre-Bach, Blycker, & Potenza, Citation2020; Zattoni et al., Citation2020). Research on pornography has proliferated in recent years, giving particular focus to the adverse effects of pornography use. For example, it is claimed that pornography usage is associated with: poorer relationships and marriage quality (Perry, Citation2016, Citation2020), mental health issues related to loneliness (Butler, Pereyra, Draper, Leonhardt, & Skinner, Citation2018), compulsivity (Egan & Parmar, Citation2013), anxiety and depression (Whitfield, Rendina, Grov, & Parsons, Citation2018), risky sexual behaviors (Wright & Randall, Citation2012), and substance misuse (Willoughby, Carroll, Nelson, & Padilla-Walker, Citation2014). Other researchers have conversely found that pornography use can have a positive impact on sexual health; for instance, it improves sexual intimacy (Hald, Smolenski, & Rosser, Citation2013; Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, Citation2010; Weinberg, Williams, Kleiner, & Irizarry, Citation2010) and sexual openness within relationships (Daneback, Traeen, & Månsson, Citation2009; Weinberg et al., Citation2010).

The increase in pornography use is largely attributed to the Internet; Cooper (Citation1998) proposed it as “The triple-A engine”, which makes pornography accessible, affordable, and anonymous. Multiple clinicians have reported that pornography use is a frequent concern amongst patients undergoing sex addiction therapy (Ayres & Haddock, Citation2009; Wood, Citation2011). A controlled study showed that men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use (PPU) have neural and behavioral mechanisms associated with anticipatory processing for cues predicting erotic rewards (Gola et al., Citation2017). Excessive pornography use was a significant factor among 81% of participants who met the criteria for hypersexual disorder in a field trial of the DSM-5 (Reid et al., Citation2012). This was highlighted by the controversy regarding whether PPU should be included as a subtype of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11, Grant et al., Citation2014). Kraus et al. (Citation2018) noted that caution is required in the evaluation of people who self-identify as having this disorder since excessive pornography consumption alone is not enough to indicate PPU (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Potenza, Orosz, & Demetrovics, Citation2020; Gola, Lewczuk, & Skorko, Citation2016). For instance, an individual can frequently consume pornography yet have the power to stop this behavior (Reid et al., Citation2012). Therefore, the present study adopted the conceptualization of PPU proposed by Kor et al. (Citation2014), according to which PPU is determined by four key factors: (1) behavioral engagement with pornography is frequent, excessive, or compulsive; (2) using pornography to reach/maintain a positive emotional state or escaping/avoiding a negative emotional state; (3) reduced self-control over pornography use; and (4) continued pornography use despite adverse consequences resulting in personal distress and functional impairment.

Scrupulosity

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates adverse outcomes of pornography usage in religious populations (Borgogna, Duncan, & McDermott, Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; Grubbs et al., Citation2019; Patterson & Price, Citation2012; Perry, Citation2018; Perry & Whitehead, Citation2019), specifically among religious men (Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; Perry, Citation2018; Perry & Snawder, Citation2017). Moral incongruence refers to the violation of one’s own sacred moral values and beliefs (Grubbs et al., Citation2019), which is a contributing factor to the relationship between PPU and religiosity (Grubbs et al., Citation2015, Citation2019). Such findings are closely related to religious individuals’ tendency to self-identify their habits of pornography use as problematic regardless of whether they follow an objectively dysregulated use pattern (Bradley, Grubbs, Uzdavines, Exline, & Pargament, Citation2016; De Jong & Cook, Citation2021; Grubbs, Grant, & Engelman, Citation2018). Nevertheless, contrasting research findings have shown religiosity to be negatively correlated or non-correlated with pornography use (Hardy, Steelman, Coyne, & Ridge, Citation2013; MacInnis & Hodson, Citation2016; Maddock, Steele, Esplin, Hatch, & Braithwaite, Citation2019).

Religiosity is a broad construct with multiple dimensions (Hackney & Sanders, Citation2003), hence, interpreting religiosity as a single factor could have contributed to the aforementioned discrepancies (Borgogna et al., Citation2018). Short, Kasper, and Wetterneck (Citation2015) proposed scrupulosity as a possible mediator of religiosity and PPU. Scrupulosity is a psychological construct characterized by pathological guilt or religious obsessions associated with breaking a religious doctrine (Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin, & Cahill, Citation2002; Abramowitz & Hellberg, Citation2020). Recent findings suggest that scrupulosity significantly predicts PPU (Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018) even when accounting for general religiosity (Borgogna, Isacco, & McDermott, Citation2020). Therefore, Borgogna, Isacco, et al. (Citation2020) argued that those who were inflexible with their own religious practice were likely to be less flexible regarding their perception of pornography use.

Multidimensional experiential avoidance

Experiential avoidance (EA) has been defined as the unwillingness of a person to experience distressing memories, thoughts, and emotions (Chawla & Ostafin, Citation2007). Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, and Strosahl (Citation1996) proposed that EA is maintained through negative reinforcement. Relief is achieved through escaping a specific experience; hence, the avoidant behavior is likely to increase. Much research supports the claim that EA can maintain or exacerbate a wide-range of psychological problems (Chawla & Ostafin, Citation2007; Larsson & Hooper, Citation2015). These avoidant behaviors often evoke more negative thoughts and emotions, consequently increasing EA and thus resulting in an ongoing cycle (Chawla & Ostafin, Citation2007). It is perhaps this cognitive dissonance that leads to the seemingly incongruous pattern of PPU in scrupulous individuals: that is, it is perhaps easier to concede to the urge to use pornography than to carry the weight of the negative thoughts and feelings associated with pornography-avoidance plus the (unrequited) urge to consume pornography.

Research has explored the connection between PPU and EA (e.g., Bradley et al., Citation2016; Levin, Lee, & Twohig, Citation2019; Levin, Lillis, & Hayes, Citation2012; Nelson, Padilla-Walker, & Carroll, Citation2010; Wetterneck, Burgess, Short, Smith, & Cervantes, Citation2012). Additionally, using pornography for experiential avoidant motivations is related to increased use and negative self-reported consequences (Levin et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the findings of Borgogna and McDermott (Citation2018) suggest that EA positively mediates the relationship between scrupulosity and PPU. Borgogna and McDermott (Citation2018) conducted a large online survey (n = 727) to identify the relationship between these two separate correlates of PPU. They used the Problematic Pornography Use Scale (Kor et al., Citation2014), which is a comprehensive measure with excellent validity (Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021). Furthermore, this scale identifies behaviors as well as perceptions (e.g., ‘I continued using pornography despite the danger of harming myself physically’, ‘I have been unsuccessful in my efforts to reduce or control the frequency I use pornography in my life’, ‘I use pornographic materials to escape my grief or to free myself from negative feelings’). Therefore, it is reasonable that studies involving this measure (including the current study) identifying PPU behaviors, and not simply subjective (and potentially biased) perceptions of own’s actions/attitudes. The findings of Borgogna and McDermott (Citation2018) showed that religious scrupulosity predicts PPU, and this relationship was mediated by EA. Furthermore, a moderation analysis revealed that this effect only held for men. However, they used the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ, Bond et al., Citation2011), which conceptualizes EA as a unidimensional construct, and thus it contradicts the multidimensional nature of EA (Gámez, Chmielewski, Kotov, Ruggero, & Watson, Citation2011).

Therefore, EA could be interpreted as a possible explanation to the paradoxical findings in the literature showing that religious areas of the USA present multiple indicators of pornography consumption (Nie, Citation2021; Perry & Whitehead, Citation2020; Whitehead & Perry, Citation2018). Further research is needed to evaluate the consistency of findings supporting EA as a positive mediator between PPU and scrupulosity (Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018). EA is a broad construct with multiple dimensions. For example, Gámez et al. (Citation2011) have proposed six sub-dimensions of EA: (1) Distress Aversion – for example, negative attitudes or evaluations regarding distress; (2) Behavioral Avoidance – for example, overt avoidant action to minimize distress; (3) Procrastination – for example, acting to delaying impending distress; (4) Distraction/Suppression – for example, attempts to ignore or suppress distress; (5) Repression/Denial – for example, dissociation from, or lack of awareness of, distress; (6) Distress Endurance – for example, effective behavior during distress. It remains unknown whether the aforementioned mediation effect is present across the six/multiple sub-dimensions of EA.

The Dark Tetrad of personality

Much research has focused on the longstanding idea that humans have a malevolent dark side (Schreiber & Marcus, Citation2020). Paulhus and Williams (Citation2002) presented the framework of the Dark Triad, which describes narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism as subclinical personality traits. Subclinical sadism was introduced as a related aversive trait, and these four constructs have been re-conceptualised as the Dark Tetrad (Buckels, Jones, & Paulhus, Citation2013; Chabrol, Van Leeuwen, Rodgers, & Séjourné, Citation2009; Johnson, Plouffe, & Saklofske, Citation2019). It is important to stress that, in the current study, we explore the Dark Tetrad using subclinical measures, and did not knowingly recruit individuals with any clinical diagnoses.

Narcissism is characterized by self-absorption and a high sense of entitlement and grandiosity (Krizan & Herlache, Citation2018). Kasper, Short, and Milam (Citation2015) identified narcissism as a significant predictor of frequent pornography use. However, increased use is not sufficient to indicate PPU (Reid, Li, Gilliland, Stein, & Fong, Citation2011). Sindermann, Sariyska, Lachmann, Brand, and Montag (Citation2018) rejected narcissism as a significant predictor for PPU. The findings of Muris, Otgaar, Meesters, Papasileka, and Pineda (Citation2020) support the relationship between narcissism and ‘deviant’ and ‘real deviant’ pornography use, but not pornography use overall. Taken together, evidence concerning the link between narcissism and PPU is inconsistent.

Subclinical psychopathy is characterized by high impulsivity, shallow affect, thrill-seeking, and physical aggression (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014; Malesza & Ostaszewski, Citation2016). Therefore, the tendency to seek stimuli combined with reduced inhibitory control over possible risky behaviors among subclinical psychopaths could increase their likelihood to develop problematic patterns of pornography use. Individuals with psychopathic traits are likely to show increased reactivity of the dopaminergic reward system in response to PPU and other types of sexual behaviors (Gola & Draps, Citation2018). Research involving correlational analyses suggests that psychopathy is associated with PPU (Muris et al., Citation2020; Sindermann et al., Citation2018; Williams, Cooper, Howell, Yuille, & Paulhus, Citation2009). However, much of this previous research was limited by sample size, use of nonspecific scales to measure PPU (for example, taking items from scales designed to measure broader internet use). Despite previous research showing a correlation between cravings for and use of pornography and subclinical psychopathy, it remains unknown whether psychopathy predicts PPU.

Machiavellianism is characterized by high levels of manipulativeness and ambition, as well as lack of sincerity and sensitivity (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014). Psychopaths do this impulsively and without concern for their reputation, whereas Machiavellians plan their actions to maintain a positive reputation (Hare & Neumann, Citation2008). During stressful situations, Machiavellians are less likely to engage in risky behaviors than psychopaths, and in contrast to narcissists, Machiavellians’ engagement in risky behaviors is generally unaffected by social support (Carre & Jones, Citation2016). Evidence suggests that Machiavellians are more likely to engage in sexual activity for reasons such as reducing stress and anxiety, experience-seeking, and boosting self-esteem (Brewer & Abell, Citation2015). Nevertheless, other studies reject that Machiavellians use sex as a form of experience-seeking (Baughman, Jonason, Veselka, & Vernon, Citation2014; Veselka, Giammarco, & Vernon, Citation2014). Such inconsistency can also be observed in the research into PPU and Machiavellianism. For instance, although according to Sindermann et al. (Citation2018) Machiavellianism and internet-pornography use disorder were significantly associated in females, this was not supported by the findings of Muris et al. (Citation2020). Therefore, the relationship between subclinical Machiavellianism and PPU remains unclear.

Subclinical sadism, also known as “everyday sadism” (Buckels et al., Citation2013), is characterized by getting pleasure or subjugation through engaging in antagonistic, cruel, and demeaning behaviors (Plouffe, Saklofske, & Smith, Citation2017). Everyday sadism and psychopathy have been found as the only two components of the Dark Tetrad that are closely related to dysfunctional impulsivity (March et al., Citation2017). Sadism is closely related to psychopathy (Williams et al., Citation2009). Researchers have found that pornography can have an impact on sadistic behaviors (Cruz, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2014). Comparably to psychopaths, it could be suggested that sadistic individuals are more likely to use pornography to satisfy sexual needs that are difficult to achieve in real life (e.g., sado-masochism). Few studies have explored the relationship between pornography and sadism (e.g., Cruz, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2014), however – to the best of our knowledge – the direct association between subclinical sadism and PPU has not yet been examined.

The current study

It is important to understand which factors are associated with (and predict) PPU to develop theory, shape research, and where necessary inform interventions. To date, it remains unknown what specific sub-dimensions of EA meditate the relationship between Scrupulosity and PPU (Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018). Previous research is inconsistent in terms of the associations between subclinical dark traits and pornography use, and much research has only considered bivariate relationships (i.e., correlations) rather than multivariate regression and/or mediation models. Certain studies’ materials are limited to a degree by the measures used. Sindermann et al. (Citation2018) used the Internet Addiction Test-Sex (Young, Citation1998), and Muris et al. (Citation2020) used the Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ; Kraus & Rosenberg, Citation2014): while the first lacks validity, the second has reduced coverage of addiction components (Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021). Moreover, 72% of the sample of Sindermann et al. (Citation2018) was composed of women, which is a potential limitation considering that women tend to report lower PPU than men (Borgogna & Aita, Citation2019; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018).

Hence, the present study explored the inter-relationships between PPU and scrupulosity, multidimensional EA (as per Gámez et al., Citation2011), and the Dark Tetrad, in a large sample of male and female adults, using reliable and valid measures. Four hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Scrupulosity would significantly predict PPU.

H2: The six dimensions of EA would significantly predict PPU; for Distress Aversion, Behavioral Avoidance, Procrastination, Distraction/Suppression, and Repression/Denial, we anticipated the those scoring higher in each dimension would demonstrate greater PPU; for Distress Endurance, we predicted that those scoring lower would demonstrate greater PPU.

H3: The relationship between Scrupulosity and PPU would be mediated by EA; the ‘direction’ of the relationship would vary across EA sub-dimensions, as per H2.

H4: The personality traits of the Dark Tetrad would significantly predict PPU.

Method

Participants

An a priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.2), based on an anticipated effects size of f2 = 0.10, with an α error probability of .05, and desired power = 0.95 (per Cohen, Citation1988) with 17 potential predictors (based on each multi-dimensional sub-scale as a predictor) suggested a target sample size of 305. We used opportunity sampling to recruit participants through social media sites (e.g., Facebook, Reddit, Twitter). To increase the global representativeness of the findings, the sample was composed of both native English and native Spanish speakers (details on English- and Spanish-language versions of the survey are provided in Design, Materials, and Procedure). The main inclusion criteria involved having used pornography and being over 18 years old. A total of 835 participants accessed the survey (English-language = 514, Spanish-language = 321). The initial data cleaning process involved removing suspicious responses (e.g., irregular, very short completion times), failed inclusion criteria (e.g., indicated no use of pornography), and unworkable data (e.g., blocks of missing data/incomplete responses). The final sample consisted of 672 participants (male = 521, female = 150, 1 non-disclosed) with an overall mean age of 26.14 years (SDAge = 8.33; min. = 18, max. = 72). Demographic characteristics are summarized in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Design, materials, and procedure

Full ethical approval for this research was granted by Glasgow Caledonian University, following the protocols of the British Psychological Society (Citation2014). The main ethical consideration of the study was participants disclosing sensitive information concerning PPU, therefore, participants were given the option to skip any questions or withdraw from the study at any given time without reason or penalty. Moreover, resources including information about PPU and support available were provided as part of the debrief, along with the lead researchers’ contact details in case participants wanted to follow up on the survey or have their data withdrawn post-hoc. Participants required an internet-enabled device to complete the survey, which was hosted by Microsoft Forms, accessed via links that they found on different social media platforms. The present study adopted a cross-sectional survey design. The variables studied are PPU, scrupulosity, multidimensional EA, and the Dark Tetrad traits.

English–Spanish translational work

The translation was completed following World Health Organization (WHO) (Citation2016) guidelines on translation and adaption of instruments. The focus of this process is on cross-cultural and conceptual equivalence, rather than on linguistic/literal equivalence. The process involved four steps: forward translation, panel back translation, pre-testing, and final version. The forward translation was by someone familiarized with the terminology of the research area. The translator was knowledgeable of English-speaking culture, but their mother tongue was Spanish. A bilingual panel (English and Spanish) reviewed the translation and identified inadequate expressions/concepts of the translation. Once the translation of the questionnaire was completed, the instrument was translated back to English by an independent translator who had no previous knowledge of the questionnaire. Discrepancies from the back-translation were discussed by the researchers and the bilingual panel, and the translation process was iterated until a satisfactory version was achieved. All the interactions described above produced the final version of the questionnaires in Spanish.

Problematic pornography use scale (PPUS)

The PPUS (Kor et al., Citation2014) is a 12-item measure of PPU and it has four factors, including: distress and functional problems (e.g., “I risked or put in jeopardy a significant relationship, place of employment, educational or career opportunity because of the use of pornographic materials”), excessive use (e.g., “I spend too much time planning to and using pornography”), control difficulties (e.g., “I keep on watching pornographic materials even though I intend to stop”), use for escape/avoid negative emotions (e.g., “I watch pornographic materials when am feeling despondent”). Participants responded on a six-point Likert scale of 1 (never true) to 6 (almost always true). The scale does not provide a cutoff score to distinguish problematic pornography use from non-problematic use. Fernandez and Griffiths (Citation2021) conducted a systematic review of 22 instruments used to measure PPU. Their findings indicated that addiction was the most influential theoretical model in the conceptualization of PPU. The PPUS was shown to have excellent coverage of addiction components, and these were closely related to those use for the diagnosis of hypersexual disorder, and compulsive sexual behavior disorder (Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021). Furthermore, Kor et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated that the scale has high construct validity and excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .93). The PPUS demonstrated good-to-excellent reliability in the present sample (full scale α = .92, Functional Problems α = .75, Excessive Use α = .85, Control Difficulties α = .87, Avoid Negative Emotions α = .90)

Multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire (MEAQ)

The MEAQ (Gámez et al., Citation2011) is a 62-item measure, with responses made on a six-point Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). This measure covers a wide scope of the EA construct with six different sub-scales: Behavioral Avoidance (e.g., “I go out of my way to avoid uncomfortable situations”), Distress Aversion (e.g., “The key to a good life is never feeling any pain”), Procrastination (e.g., “I tend to put off unpleasant things that need to get done”), Distraction/Suppression (e.g., “I work hard to keep out upsetting feelings”), Repression/Denial (e.g., “I am able to “turn off” my emotions when I don’t want to feel”), Distress Endurance (e.g., “I am willing to suffer for the things that matter to me”). The MEAQ has been found to have excellent construct validity (Rochefort, Baldwin, & Chmielewski, Citation2018) and excellent internal consistency (α = 92, Gámez et al., Citation2011). Similarly, internal consistency for the present sample was very good-to-excellent (full scale α = .90, Behavioral Avoidance α = .87, Distress Aversion α =.89, Procrastination α =.88, Distraction/Suppressionα= .88, Repression/Denial α = .84, Distress Endurance α = .88)

Penn inventory of Scrupulosity - Revised (PIOS-R)

The PIOS-R (Olatunji, Abramowitz, Williams, Connolly, & Lohr, Citation2007) was used to measure scrupulosity. We specifically used the subscale “Fear of Sin”, which consists of 10 items scored on a four-point Likert scale of 1 (never) to 4 (constantly); for example, “I must try hard to avoid having certain immoral thoughts”. The PIOS-R has shown appropriate convergent and discriminant validity (Abramowitz et al., Citation2002; Olatunji et al., Citation2007). Although the PIOS-R offers an additional subscale (“Fear of God”), we concentrated on the “Fear of Sin” subscale since it has been shown to be an appropriate measure of scrupulosity (Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; Olatunji, Citation2008). In contrast with the rest of the scales, this measure was not translated for the Spanish-language iteration of the survey; instead, we used a validated Spanish version (Gallegos et al., Citation2018). The internal consistency of the PIOS-R “Fear of Sin” for the present sample was excellent (α = .91).

The Dark Tetrad

The Dark Tetrad measures were obtained through two different scales, both scored on a five-point Likert scale of 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). First, the Comprehensive Assessment of Sadistic Tendencies (CAST; Buckels & Paulhus, Citation2014) is an 18-item self-report measure of subclinical sadistic traits. It includes three subscales of sadism: direct-verbal, vicarious, and direct-physical (e.g., “I enjoy physically hurting people”). The CAST has good internal consistency (Buckels, Citation2018; Buckels, Trapnell, Andjelovic, & Paulhus, Citation2019). Furthermore, Buckels (Citation2018) demonstrated good convergent validity between the CAST and the second constituting scale: the Short Dark Triad (SD3, Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014), which is a 27-item questionnaire consisting of three 9-items subscales, one for each of the Dark Tetrad traits: Machiavellianism (e.g., “I like to use clever manipulation to get my way”), Narcissism (e.g., “I have been compared to famous people”), and Psychopathy (e.g., “People who mess with me always regret it”). Jones and Paulhus (Citation2014) analysis of the subscales across 4 studies (N = 1063) supported the efficient validity and reliability of the SD3. In the current data set, the sub-dimensions of the Dark Tetrad demonstrated good-to-very good internal reliability (CAST Physical α =.75, CAST Verbal α = .78; CAST Vicarious α = .78; Machiavellianism α = .76, Narcissism α = .71, Psychopathy α = .70).

Procedure

After accessing the link via social media posts, participants were presented with the information sheet, which described only the broad purpose of the study to prevent response bias. Subsequently, participants gave informed consent and entered an identifier code that could be used when contacting the researchers in the case that participants wished to withdraw their data. Participants were asked to enter their age, gender, biological sex at birth, and sexual orientation before completing the standardized measures. The approximate completion time of the survey was 25 minutes.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 26. We conducted several pretests to ensure that our pooled English-Spanish-language data set was appropriate for further inferential analysis. Cronbach’s alpha reliability statistics have been reported previously and were (more than) satisfactory. Furthermore, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses to ensure that the pooled data set was aligned with the dimensions of the original scales. Full details of these analyses can be found in Supplementary Material A.

Assumption checks verified that data was linear and normally distributed and did not have blatant outliers. Pearson’s correlations (two-tailed) were conducted to determine the relationships between PPUS, EA, scrupulosity, and the Dark Tetrad traits. We took forward possible predictors into a series of multiple regression analyses using a stepwise method. Finally, we performed mediation analysis between scrupulosity, the six different dimensions of EA, and the four subscales of PPU.

Results

Correlations

A full correlation matrix can be found in .

Table 2. Pearson’s correlations between problematic pornography use, experiential avoidance, scrupulosity, and the Dark Tetrad (N = 672).

Participants’ total PPUS scores correlated significantly with all measures except one sub-scale of experiential avoidance (Distract/Supp) and Narcissism. The four sub-scales of PPUS showed slightly differing patterns of association with the other co-variates. The subscales of Distress and Functional Problems and of Control difficulties showed the same pattern of association as the total PPUS measure (relationships with all variables except Distract/Supp and Narcissism). The PPUS subscales of Excessive Use and Use for Escape/Avoid Negative emotions correlated will all covariates except Narcissism.

Regressions

We conducted a series of multiple linear regressions (Enter method) to explore the relative contributions of experiential avoidance, scrupulosity, and the Dark Tetrad to problematic pornography use (PPUS total and per subscale). Co-variates that reached p≤.10 were considered as candidate predictors for multivariate models as typical significance limits (e.g., p≤.05) have been shown to fail to establish significance in variables otherwise known to be predictive (Bursac, Gauss, Williams, & Hosmer, Citation2008). Initial exploration of the data determined that assumptions (multicollinearity, independence of error terms, non-zero variances, normality, homoscedasticity, linearity) were upheld. Model summaries per outcome variable can be found in . Supplementary Material B contains details of all co-efficients across outcome variables.

Table 3. Final model summaries across outcome variables.

PPUS total

The final model for PPUS Total explained approximately 32.6% of the variance in these scores. Four components – Fear of Sin, Vicarious Sadism, Behavioral Avoidance and Distress Aversion – all contributed significantly to the model. Standardized co-efficients show that increases in Fear of Sin, Vicarious Sadism, and Distress Aversion dimensions were associated with increases in participants’ PPUS Total scores. Participants with lower Behavioral Avoidance scores (i.e., those participants who do not avoid problematic behaviors/thoughts/feelings) reported higher PPUS Total scores.

PPUS distress and functional problems

The final model for PPUS Distress and Functional Problems explained approximately 26.3% of the variance in these scores. Three components – Fear of Sin, Vicarious Sadism, and Distress Endurance – all contributed significantly to the model. Standardized co-efficients show that increases in Fear of Sin and Vicarious Sadism were associated with increases in participants’ PPUS Distress and Functional Problems scores, whereas participants with lower Distress Endurance typically reported greater PPUS Distress and Functional Problems.

PPU excessive use

The final model for PPUS Excessive Use explained approximately 19.3% of the variance in these scores. Two components – Fear of Sin and Vicarious Sadism – contributed significantly to the model. Standardized co-efficients show that increases in both co-variates were associated with increases in participants’ PPUS Excessive Use scores.

PPUS control difficulties

The final model for PPUS Control Difficulties explained approximately 24.3% of the variance in these scores. Three components – Fear of Sin, Vicarious Sadism, and Behavioral Avoidance – contributed significantly to the model. Standardized co-efficients show that increases in Fear of Sin and Vicarious sadism were associated with increases in participants’ PPUS Control Difficulties scores. Participants with lower Behavioral Avoidance scores (i.e., those participants who do not avoid problematic behaviors/thoughts/feelings) reported higher PPUS Control Difficulties scores.

PPUS use for escape/avoid negative emotions

The final model for PPUS Use for Escape/Avoid Negative Emotions explained approximately 22.8% of the variance in these scores. Five components – Fear of Sin, Distress Aversion, Repression/Denial, Behavioral Avoidance, and Procrastination – contributed significantly to the model. Standardized co-efficients show that increases in Fear of Sin, Distress Aversion, Repression/Denial, and Procrastination were associated with increases in participants’ PPUS Use for Escape/Avoid Negative Emotions. Lower scores in Behavioral Avoidance (i.e., those who do not avoid problematic behaviors/situations/feelings) were typically associated with higher scores in PPUS Use for Escape/Avoid Negative Emotions.

Mediation

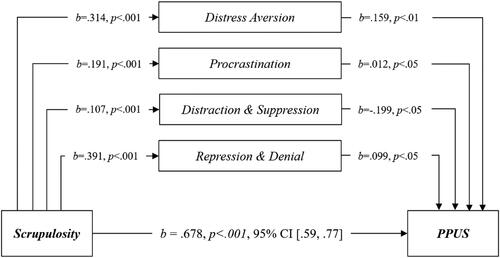

A mediation analysis was conducted to assess whether the six dimensions of EA mediated the relationship between scrupulosity and PPUS Total. illustrates significant mediating pathways.

Bootstrap analysis of the indirect effect of scrupulosity on PPU showed that four sub-dimensions of EA (Distress Aversion, Procrastination, Distraction/Suppression, and Repression/Denial) emerged as significant mediators.

Supplementary Material C contains further details of mediation analyses, considering the relationships between Fear of Sin, EA, and sub-dimensions of the PPUS scale.

Discussion

Given the global prevalence of pornography use (Pornhub, Citation2019; Price et al., Citation2016) and the adverse effects that it potentially can be associated with (e.g., Borgogna, Isacco, et al., Citation2020; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; Patterson & Price, Citation2012; Perry & Whitehead, Citation2019; Short et al., Citation2015), understanding the factors and mechanisms behind PPU is crucial for clinicians and researchers. In addition to religious factors, previous research also indicates that personality dimensions can influence PPU (Borgogna & Aita, Citation2019; Muris et al., Citation2020; Sindermann et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the present study examined the two corresponding areas concomitantly: first, the association between PPU with scrupulosity and EA, and second, the relationship between PPU and the Dark Tetrad.

Scrupulosity, experiential avoidance, and problematic pornography use

The first hypothesis (H1) stated that scrupulosity would predict PPU. In line with previous research (e.g., Borgogna, Isacco, et al., Citation2020; Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; De Jong & Cook, Citation2021), scrupulosity (i.e., Fear of Sin) significantly predicted the total PPUS score, plus the four subscales of the PPUS, including distress and functional problems, excessive use, avoiding negative emotions, and control difficulties. Therefore, H1 was supported.

The second hypothesis (H2) stated that the six dimensions of EA would significantly predict PPU. The results partially supported this. Total PPUS scores were predicted by Behavioral Avoidance and Distress Aversion. The PPUS subscale of Distress and Functional Problems was significantly associated with Distress Endurance. The PPUS subscale scores related to Excessive Use was not predicted by EA (only scrupulosity and Vicarious Sadism). Scores from the PPUS subscale of using pornography to Avoid Negative Emotions was associated with distress aversion, repression/denial, behavioral avoidance, and procrastination. The Control Difficulties subscale was only predicted by Behavioral Avoidance, in terms of EA. Although these findings indicate that certain dimensions of EA play a significant role in PPU (particularly Behavioral Avodiance), Distraction/Suppression did not associate with any aspect of the PPUS. Altogether, H2 was partially supported.

These findings give a more nuanced understanding of the specific types of EA that influence PPU. Across the different models showing the predictive effect that EA had on PPU, Behavioral Avoidance and Distress Aversion were the most recurrent EA dimensions. The PPUS subscale related to using pornography to avoid negative emotions was most-clearly influenced by EA. Meta-analytic findings show that dysregulation of sexual behaviors can be a significant source of distress (Grubbs et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it could be suggested that a person with negative cognitions in relation to the distress caused by experiencing PPU would have a stronger need to escape this emotion. Such individuals would be more likely to use pornography with purpose of getting a sense of relief, and thus, strengthening the (problematic) cycle of using pornography to avoid distress. This could be magnified by the fact that moral incongruence regarding PPU is strongly associated to cognitive dissonance, which can lead people to stop engaging in enjoyable activities or social connections (Perry, Citation2017, p. 218). On the other hand, our findings also revealed that behavioral avoidance was negatively associated with using pornography to avoid negative emotions. Therefore, based on the assumption that PPU can be a source of distress, it could be argued that those scoring higher on behavioral avoidance would avoid using pornography if this became problematic. Future research should explore this (potentially) negative relationship as it could provide insight into how behavioral avoidance is an effective method to reduce the usage of pornography to avoid negative emotions.

The third hypothesis (H3) predicted that the relationship between Scrupulosity and PPU would be mediated by EA, and the nature of this effect would vary across the different sub-dimensions of EA. The mediation analysis confirmed that, in the relationship between scrupulosity and PPU, some dimensions of EA played a more-impactful role than others. Thus, H3 was supported. Although causal effect cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional nature of the present study, these findings along with those of Borgogna and McDermott (Citation2018) suggest that avoiding negative emotions plays a central role in the development of PPU among scrupulous people. Borgogna and McDermott (Citation2018) observed such an effect only in men, whereas in the current study, we replicate this effect with a large sample including both men and women.

Three mediators: distress aversion, distraction/suppression, and repression/denial are characterized by immediate maladaptive responses to distress. Scrupulous moral incongruence is a source of distress, and it can significantly influence PPU (Grubbs, Grant, et al., Citation2018; Grubbs & Perry, Citation2019; Perry, Citation2018; Perry & Whitehead, Citation2019). Moreover, self-perceived dysregulated pornography use can also be a form of moral incongruence, which as a result of not aligning with one’s own values can trigger distress and considerably affect PPU (Droubay et al., Citation2020; Grubbs, Grant, et al., Citation2018; Grubbs & Perry, Citation2019; Grubbs et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it could be suggested scrupulous people’s psychological distress caused by sexual urges to watch pornography would be alleviated via one of the following EA mechanisms: distress aversion, distraction/suppression, and repression/denial. Consequently, the individual develops a maladaptive mechanism that feeds the compulsive cycle. This is closely related to longitudinal findings showing that moral scruples about self-perceived PPU have a greater effect on maintaining pornography use over time than self-perceived PPU on its own (Grubbs, Grant, et al., Citation2018).

The Dark Tetrad

Finally, we anticipated that the personality traits of the Dark Tetrad would significantly predict PPU (H4). In agreement with previous research (e.g., Muris et al., Citation2020; Sindermann et al., Citation2018; Williams et al., Citation2009), psychopathy and Machiavellianism were positively correlated with PPU. Our results revealed that narcissism was not significantly associated with PPU, consistent with Williams et al. (Citation2009) and Sindermann et al. (Citation2018), but in contrast to Kasper et al. (Citation2015). The present study expanded previous research by exploring the relationship between aversive personality traits and PPU by revealing that vicarious, physical, and verbal sadism were significant positive correlates of PPU. Apart from using pornography to avoid negative emotions, vicarious sadism predicted the three remaining subscales from the PPUS. Therefore, contrary to our expectations, vicarious sadism was the only trait of the Dark Tetrad that predicted PPU, and thus H4 was rejected. It is important to stress that our bivariate correlational results were largely consistent with most previous research; however, this previous research had generally failed to include multivariate regression-type analyses in their studies. Thus it is possible that those previous studies would also have observed only simple correlations between subclinical dark traits and PPU. Furthermore, it could simply be that in terms of the regression models, traits such as the classic, traditional Dark Triad do not explain enough variance in PPU to factor when considered concurrently alongside sadism and multidimensional EA.

Previous research showed significant correlations between pornography use and sadistic tendencies (Cruz, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2014). Our findings have confirmed this relationship, and also revealed that vicarious sadism predicts PPU. Although we anticipated that people scoring high on the CAST would be more likely to use pornography to satisfy sadistic sexual needs, physical and verbal sadism did not predict PPU. This might be partially explained by the fact that verbal and physical sadism involves directly inflicting pain (Buckels & Paulhus, 2014), and this cannot be achieved through using pornography itself (or could only be achieved with difficulty). On other hand, as those scoring high on vicarious sadism are likely to find enjoyment in seeing others suffer, it could be argued that this is the reason why vicarious sadism predicted PPU. Content analysis from different studies indicate that the number of scenes from mainstream pornography displaying verbal or physical aggression ranges from 30% to 45% (Fritz et al., Citation2020; Fritz & Paul, Citation2017; Shor & Gloriz, Citation2019). Therefore, the significant predictive effect of vicarious sadism on PPU could be due to high prevalence of pornography use combined with high levels of aggressive pornography content. To achieve a more nuanced understanding of this relationship, it would be necessary to examine whether aggressive pornographic content consumption has a mediating effect between vicarious sadism and PPU.

Limitations and future directions

Certain limitations should be considered regarding the methodology adopted in the present study. One possible downside of this study is that causal effect cannot be inferred because of its cross-sectional design. Prior evidence bolsters our findings on the link between PPU with EA and scrupulosity (Borgogna, Isacco, et al., Citation2020; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; Levin, Lillis, & Hayes, Citation2012; Wetterneck et al., Citation2012), however, evidence exploring the role of the Dark Tetrad on PPU is limited. Our findings were limited since extraneous factors of personality were not considered. For instance, behavioral and genetic evidence supports the association between aversive personality traits and the Big Five (Lee & Ashton, Citation2005; Vernon et al., Citation2008), and previous literature supports the link between PPU and the Big Five (Borgogna & Aita, Citation2019). Therefore, it may be beneficial for future studies to examine the role of the Big Five personality traits on the interaction between the Dark Tetrad and PPU.

Another potential limitation was reliance on participant self-report, risking effects such as response and self-selection bias. Nevertheless, this limitation was partially covered by capturing a sample with a wide range of demographic characteristics. Although adopting a multidimensional approach this study has provided a deeper insight into the broadness of EA and its relationship with PPU, further work is needed to understand the implications of such findings. Therefore, mixed-methods and qualitative designs might allow researchers get a more nuanced understanding of the role that behavioral avoidance, distress aversion, repression/denial, and distraction/suppression in the relationship between PPU and scrupulosity.

The final potential limitation to note is the composition of the sample. 78% of participants were males, which is important considering that the relationship between scrupulosity and PPU has been found to be moderated by gender (Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018). Our findings have shown that vicarious sadism is a significant predictor of PPU. In pornography, women are the target of any aggression in the vast majority of cases (Fritz & Paul, 2017, Shor & Gloriz, 2019). Sex/gender could play an important role in the relationship between PPU and vicarious sadism. It is well known that gender is a form of self-identification within a broad spectrum, and gender-related factors such as traditional masculinity have been found to be associated with PPU (Borgogna, Isacco, et al., Citation2020). The number of studies examining factors associated with PPU beyond cis-heterosexual and gender-binary populations is very limited, hence, future inclusion efforts are required to examine whether the available evidence can be generalized to LBTQ + populations.

Practical implications

The present study contributes to a growing body of research of PPU implicating scrupulosity and EA (Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Borgogna & McDermott, Citation2018; De Jong & Cook, Citation2021; Grubbs, Grant, et al., Citation2018; Levin et al., Citation2019; Wetterneck et al., Citation2012) as well as aversive personality traits (Muris et al., Citation2020; Sindermann et al., Citation2018). Research exploring the relationship between the Dark Tetrad with PPU remain at the early stages of development, and future efforts are required to identify consistency and evaluate the applied value of such findings. Previous research has provided insight into the role of EA, and this study has expanded those findings by identifying what specific dimensions of EA are more significantly associated with PPU.

The important role of distress on individuals experiencing PPU is an indicator that treatment options should be reconsidered. For instance, although naltrexone has been proposed as an effective treatment for problematic sexual behaviors (Capurso, Citation2017; Savard et al., Citation2020), this medication can have adverse effects such as trouble sleeping, anxiety, and depression, all of which are factors associated with PPU (Borgogna et al., Citation2018; Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021; Kor et al., Citation2014; Kraus & Sweeney, Citation2019). Furthermore, this type of treatment does not help people to develop psychological flexibility, which is controversial considering that EA maintains or even increments problematic thoughts and behaviors (Chawla & Ostafin, Citation2007). Therefore, approaches that target psychological flexibility such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., Citation2004) hold great potential for effectively assisting people experiencing PPU. Two trials have demonstrated that ACT is a highly effective approach for men experiencing PPU (Crosby & Twohig, Citation2016; Twohig & Crosby, Citation2010). A systematic review of trials exploring treatments for those who self-identified as experiencing PPU demonstrated that cognitive and behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective approach to PPU (Sniewski, Farvid, & Carter, Citation2018). Considering that sexual urges and associated distress could be a significant contributor to the development of PPU, clinicians might consider CBT approaches that empathize dealing with such urges. For instance, relapse prevention strategies (e.g., addressing high-risk situations for relapse, and developing lapse management techniques) are used for different problematic behaviors (Menon & Kandasamy, Citation2018), and these strategies could be an effective approach for people experiencing PPU.

Conclusion

As pornography use increases, any related problems are likely to grow in parallel. Pornography use is itself not necessarily a problematic behavior; however, it can become problematic. The present study builds upon the limited literature examining the impact of aversive personality traits on PPU. As in previous studies, our results showed that although Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are correlated with PPU, they did not predict PPU. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study introducing the sadism dimensions of the Dark Tetrad to the field of research on PPU, which revealed that vicarious sadism was the only aversive personality trait that significantly predicted PPU.

In addition to contributing to the body of research exploring the role of subclinical “dark traits” on PPU, this paper has given an account of the association between PPU with scrupulosity and the multiple dimensions of EA. The evidence from this study has supported the well-established relationship between PPU and scrupulosity and revealed that certain dimensions of EA are more strongly associated with PPU than others.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding details

The authors have no funding to declare.

usac_a_2101168_sm4574.docx

Download MS Word (118.1 KB)usac_a_2101168_sm4658.docx

Download MS Word (13.4 KB)usac_a_2101168_sm4604.docx

Download MS Word (24.1 KB)References

- Abramowitz, J. S., & Hellberg, S. N. (2020). Scrupulosity. In E. A. Storch, D. McKay, & J. S. Abramowitz (Eds.), Advanced casebook of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (pp. 71–87). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816563-8.00005-X

- Abramowitz, J. S., Huppert, J. D., Cohen, A. B., Tolin, D. F., & Cahill, S. P. (2002). Religious obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample: The Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 825–838. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00070-5

- Ayres, M. M., & Haddock, S. A. (2009). Therapists’ approaches in working with heterosexual couples struggling with male partners’ online sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 16(1), 55–78. doi:10.1080/10720160802711952

- Baughman, H. M., Jonason, P. K., Veselka, L., & Vernon, P. A. (2014). Four shades of sexual fantasies linked to the dark triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 47–51. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.034

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., … Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

- Borgogna, N. C., & Aita, S. L. (2019). Problematic pornography viewing from a big-5 personality perspective. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(3–4), 293–314. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1670302

- Borgogna, N. C., & McDermott, R. C. (2018). The role of gender, experiential avoidance, and scrupulosity in problematic pornography viewing: A moderated-mediation model. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 319–344. doi:10.1080/10720162.2018.1503123

- Borgogna, N. C., Duncan, J., & McDermott, R. C. (2018). Is scrupulosity behind the relationship between problematic pornography viewing and depression, anxiety, and stress? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 293–318. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1567410

- Borgogna, N. C., Isacco, A., & McDermott, R. C. (2020). A closer examination of the relationship between religiosity and problematic pornography viewing in heterosexual men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 27(1–2), 23–44. doi:10.1080/10720162.2020.1751361

- Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Berry, A. T., & Browning, B. R. (2020). Masculinity and problematic pornography viewing: The moderating role of self-esteem. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(1), 81–94. doi:10.1037/men0000214

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Potenza, M. N., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). High-frequency pornography use may not always be problematic. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(4), 793–811. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.007

- Bradley, D. F., Grubbs, J. B., Uzdavines, A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2016). Perceived addiction to internet pornography among religious believers and nonbelievers. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 23(2–3), 225–243. doi:10.1080/10720162.2016.1162237

- Brewer, G., & Abell, L. (2015). Machiavellianism and sexual behavior: Motivations, deception and infidelity. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 186–191. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.028

- British Psychological Society. (2014). Code of human research ethics. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- Buckels, E. E. (2018). The psychology of everyday sadism. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

- Buckels, E. E., Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2013). Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychological Science, 24(11), 2201–2209. doi:10.1177/0956797613490749.

- Buckels, E. E., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Comprehensive assessment of sadistic tendencies (CAST). Unpublished instrument, Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia.

- Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., Andjelovic, T., & Paulhus, D. L. (2019). Internet trolling and everyday sadism: Parallel effects on pain perception and moral judgment. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 328–340. doi:10.1111/jopy.12393.

- Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K., & Hosmer, D. W. (2008). Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code for Biology and Medicine, 3(17), 17. doi:10.1186/1751-0473-3-17

- Butler, M. H., Pereyra, S. A., Draper, T. W., Leonhardt, N. D., & Skinner, K. B. (2018). Pornography use and loneliness: A bidirectional recursive model and pilot investigation. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 127–137. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/ doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1321601

- Campbell, L., & Kohut, T. (2017). The use and effects of pornography in romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 6–10.

- Capurso, N. A. (2017). Naltrexone for the treatment of comorbid tobacco and pornography addiction. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(2), 115–117. doi:10.1111/ajad.12501

- Carre, J. R., & Jones, D. N. (2016). The impact of social support and coercion salience on dark triad decision making. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 92–95. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.006

- Chabrol, H., Van Leeuwen, N., Rodgers, R., & Séjourné, N. (2009). Contributions of psychopathic, narcissistic, Machiavellian, and sadistic personality traits to juvenile delinquency. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(7), 734–739. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.020

- Chawla, N., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to psychopathology: An empirical review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(9), 871–890.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Cooper, A. (1998). Sexuality and the internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(2), 187–193. doi:10.1089/cpb.1998.1.187

- Crosby, J. M., & Twohig, M. P. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for problematic internet pornography use: A randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 47(3), 355–366.

- Cruz, G. V. (2020). Men’s sexual sadism towards women in Mozambique: Influence of pornography? Current Psychology, 39(2), 694–704.

- Daneback, K., Traeen, B., & Månsson, S.-A. (2009). Use of pornography in a random sample of Norwegian heterosexual couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(5), 746–753. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9314-4

- De Jong, D. C., & Cook, C. (2021). Roles of religiosity, Obsessive-Compulsive symptoms, scrupulosity, and shame in self-perceived pornography addiction: A preregistered study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(2), 695–709. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01878-6

- Droubay, B.A., Shafer, K., & Butters, R.P. (2020) Sexual Desire and Subjective Distress among Pornography Consumers, Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(8), 773–792. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2020.1822483

- Egan, V., & Parmar, R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(5), 394–409.

- Fernandez, D. P., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: A systematic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 44(2), 111–141. doi:10.1177/0163278719861688

- Fritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041–3053. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0

- Fritz, N., & Paul, B. (2017). From orgasms to spanking: A content analysis of the agentic and objectifying sexual scripts in feminist, for women, and mainstream pornography. Sex Roles, 77(9–10), 639–652.

- Gallegos, J., Sánchez-Jauregui, G., Hidalgo, J., Davila-de Gárate, S. M., Támez-Díaz, O. G., & Fisak, B. (2018). The validation of a Spanish version of the Pennsylvania inventory of scrupulosity - revised. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 21(2), 194–203. doi:10.1080/13674676.2018.1432582

- Gámez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 692–713.

- Gola, M., & Draps, M. (2018). Ventral striatal reactivity in compulsive sexual behaviors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 546.

- Gola, M., Lewczuk, K., & Skorko, M. (2016). What matters: Quantity or quality of pornography use? psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(5), 815–824. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.169

- Gola, M., Wordecha, M., Sescousse, G., Lew-Starowicz, M., Kossowski, B., Wypych, M., … Marchewka, A. (2017). Can pornography be addictive? An fMRI study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(10), 2021–2031. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.78

- Grant, J. E., Atmaca, M., Fineberg, N. A., Fontenelle, L. F., Matsunaga, H., Janardhan Reddy, Y. C., Simpson, H. B., Thomsen, P. H., van den Heuvel, O. A., Veale, D., Woods, D. W., & Stein, D. J. (2014). Impulse control disorders and “behavioural addictions” in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(2), 125–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20115

- Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I. Hook, J. N., & Carlisle, R. D. (2015). Transgression as Addiction: Religiosity and Moral Disapproval as Predictors of Perceived Addiction to Pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior 44, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z

- Grubbs, J. B., & Perry, S. L. (2019). Moral incongruence and pornography use: A critical review and integration. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 29–37. doi:10.1080/00224499.2018.1427204

- Grubbs, J. B., Grant, J. T., & Engelman, J. (2018). Self-identification as a pornography addict: Examining the roles of pornography use, religiousness, and moral incongruence. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 269–292. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1565848

- Grubbs, J. B., Grubbs, J. B., Perry, S. L., Perry, S. L., Wilt, J. A., Wilt, J. A., & Reid, R. C. (2019). Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 397–415. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1248-x

- Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Kraus, S. W. (2018). Moral disapproval and perceived addiction to internet pornography: A longitudinal examination. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 113(3), 496–506.

- Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43–55. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160

- Hald, G. M., Smolenski, D., & Rosser, B. S. (2013). Perceived effects of sexually explicit media among men who have sex with men and psychometric properties of the pornography consumption effects scale (PCES). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(3), 757–767.

- Hardy, S. A., Steelman, M. A., Coyne, S. M., & Ridge, R. D. (2013). Adolescent religiousness as a protective factor against pornography use. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 131–139. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2012.12.002

- Hare, R., & Neumann, C. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 217–246.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., … McCurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54(4), 553–578. doi:10.1007/BF03395492

- Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(6), 1152–1168.

- Johnson, L. K., Plouffe, R. A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2019). Subclinical sadism and the dark triad: Should there be a dark tetrad? Journal of Individual Differences, 40(3), 127–133. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000284

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41. doi:10.1177/1073191113514105

- Kasper, T. E., Short, M. B., & Milam, A. C. (2015). Narcissism and internet pornography use. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(5), 481–486.

- Kor, A., Zilcha-Mano, S., Fogel, Y. A., Mikulincer, M., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Psychometric development of the problematic pornography use scale. Addictive Behaviors, 39(5), 861–868.

- Kraus, S., Rosenberg, H. (2014). The Pornography Craving Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 451–462. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3

- Kraus, S. W., & Sweeney, P. J. (2019). Hitting the target: Considerations for differential diagnosis when treating individuals for problematic use of pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 431–435.

- Kraus, S. W., Krueger, R. B., Briken, P., First, M. B., Stein, D. J., Kaplan, M. S., … Reed, G. M. (2018). Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD‐11. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(1), 109–110. doi:10.1002/wps.20499

- Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2018). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 22(1), 3–31.

- Larsson, A., & Hooper, N. (2015). The research journey of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2005). Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism in the five-factor model and the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1571–1582. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.016

- Levin, M. E., Lee, E. B., & Twohig, M. P. (2019). The role of experiential avoidance in problematic pornography viewing. The Psychological Record, 69(1), 1–12. doi:10.1007/s40732-018-0302-3

- Levin, M. E., Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2012). When is online pornography viewing problematic among college males? Examining the moderating role of experiential avoidance. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19(3), 168–180.

- Levin, M. E., Lillis, J., Seeley, J., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Biglan, A. (2012). Exploring the relationship between experiential avoidance, alcohol use disorders, and alcohol-related problems among first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(6), 443–448.

- Liu, J. (2014). The mediator effect of psychopathy between pornography and sadism [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Brandeis University, Waltham, MA.

- Löfgren-Mårtenson, L., & Månsson, S. (2010). Lust, love, and life: A qualitative study of Swedish adolescents’ perceptions and experiences with pornography. Journal of Sex Research, 47(6), 568–579. doi:10.1080/00224490903151374

- MacInnis, C. C., & Hodson, G. (2016). Surfing for sexual sin: Relations between religiousness and viewing sexual content online. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 23(2–3), 196–210. doi:10.1080/10720162.2015.1130000

- Maddock, M. E., Steele, K., Esplin, C. R., Hatch, S. G., & Braithwaite, S. R. (2019). What is the relationship among religiosity, self-perceived problematic pornography use, and depression over time? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(3–4), 211–238. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1645061

- Malesza, M., & Ostaszewski, P. (2016). Dark side of impulsivity—Associations between the dark triad, self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 197–201. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.016

- March, E., Grieve, R., Marrington, J., & Jonason, P. K. (2017). Trolling on Tinder® (and other dating apps): Examining the role of the Dark Tetrad and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 139–143. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.025

- Menon, J., & Kandasamy, A. (2018). Relapse prevention. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(Suppl 4), S473–S478. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_36_18

- Mestre-Bach, G., Blycker, G. R., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 181–183.

- Muris, P., Otgaar, H., Meesters, C., Papasileka, E., & Pineda, D. (2020). The dark triad and honesty-humility: A preliminary study on the relations to pornography use. Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence, 5(1), 3. doi:10.23860/dignity.2020.05.01.03

- Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2010). I believe it is wrong but I still do it”: A comparison of religious young men who do versus do not use pornography. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2(3), 136–147. doi:10.1037/a0019127

- Nie, F. (2021). Adolescent porn viewing and religious context: Is the eye still the light of the body? Deviant Behavior, 42(11), 1382–1314. doi:10.1080/01639625.2020.1747154

- Olatunji, B. O. (2008). Disgust, scrupulosity and conservative attitudes about sex: Evidence for a mediational model of homophobia. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1364–1369. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.001

- Olatunji, B. O., Abramowitz, J. S., Williams, N. L., Connolly, K. M., & Lohr, J. M. (2007). Scrupulosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Confirmatory factor analysis and validity of the penn inventory of scrupulosity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(6), 771–787.

- Patterson, R., & Price, J. (2012). Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: Does pornography impact the actively religious differently? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(1), 79–89.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

- Perry, S. L. (2016). From bad to worse? Pornography consumption, spousal religiosity, gender, and marital quality. Sociological Forum, 31(2), 441–464. doi:10.1111/socf.12252

- Perry, S. L. (2017). Not practicing what you preach: Religion and incongruence between pornography beliefs and usage. Journal of Sex Research. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1333569

- Perry, S. L. (2018). Not practicing what you preach: Religion and incongruence between pornography beliefs and usage. Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 369–380. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1333569

- Perry, S. L. (2020). Pornography and relationship quality: Establishing the dominant pattern by examining pornography use and 31 measures of relationship quality in 30 national surveys. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1199–1213. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01616-7

- Perry, S. L., & Snawder, K. J. (2017). Pornography, religion, and parent-child relationship quality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1747–1761.

- Perry, S. L., & Whitehead, A. L. (2019). Only bad for believers? Religion, pornography use, and sexual satisfaction among american men. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 50–61. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1423017

- Perry, S., & Whitehead, A. (2020). Do people in conservative states really watch more porn? A hierarchical analysis. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6, 237802312090847. doi:10.1177/2378023120908472

- Plouffe, R. A., Saklofske, D. H., & Smith, M. M. (2017). The assessment of sadistic personality: Preliminary psychometric evidence for a new measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 166–171. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.043

- Pornhub. (2018, December 11). 2018 year in review. Accessed from: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2018-year-inreview

- Pornhub. (2019, December 11). 2019 year in review. Accessed from: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2019-year-inreview

- Price, J., Patterson, R., Regnerus, M., & Walley, J. (2016). How much more XXX is Generation X consuming? Evidence of changing attitudes and behaviors related to pornography since 1973. Journal of Sex Research, 53(1), 12–20. doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.1003773

- Reid, R. C., Carpenter, B. N., Hook, J. N., Garos, S., Manning, J. C., Gilliland, R., … Fong, T. (2012). Report of findings in a DSM‐5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(11), 2868–2877. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02936.x

- Reid, R. C., Li, D. S., Gilliland, R., Stein, J. A., & Fong, T. (2011). Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the pornography consumption inventory in a sample of hypersexual men. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37(5), 359–385. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.607047

- Rochefort, C., Baldwin, A. S., & Chmielewski, M. (2018). Experiential avoidance: An examination of the construct validity of the AAQ-II and MEAQ. Behavior Therapy, 49(3), 435–449.

- Savard, J., Öberg, K. G., Chatzittofis, A., Dhejne, C., Arver, S., & Jokinen, J. (2020). Naltrexone in compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A feasibility study of twenty men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(8), 1544–1552.

- Schreiber, A., & Marcus, B. (2020). The place of the “Dark Triad” in general models of personality: Some meta-analytic clarification. Psychological Bulletin, 146(11), 1021–1041. doi:10.1037/bul0000299

- Shor, E., & Golriz, G. (2019). Gender, race, and aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 739–751.

- Short, M. B., Kasper, T. E., & Wetterneck, C. T. (2015). The relationship between religiosity and internet pornography use. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(2), 571–583.

- Sindermann, C., Sariyska, R., Lachmann, B., Brand, M., & Montag, C. (2018). Associations between the dark triad of personality and unspecified/specific forms of internet-use disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 985–992.

- Sniewski, L., Farvid, P., & Carter, P. (2018). The assessment and treatment of adult heterosexual men with self-perceived problematic pornography use: A review. Addictive Behaviors, 77, 217–224.

- Twohig, M. P., & Crosby, J. M. (2010). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for problematic internet pornography viewing. Behavior Therapy, 41(3), 285–295. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2009.06.002

- Vernon, P.A., Villani, V.C., Vickers, L.C., & Harris, J.A. (2008). A behavioral genetic investigation of the dark triad and the big 5. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(2), 445–452.

- Veselka, L., Giammarco, E. A., & Vernon, P. A. (2014). The Dark Triad and the seven deadly sins. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 75–80. [Database] doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.055

- Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., Kleiner, S., & Irizarry, Y. (2010). Pornography, normalization, and empowerment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(6), 1389–1401.

- Wetterneck, C. T., Burgess, A. J., Short, M. B., Smith, A. H., & Cervantes, M. E. (2012). The role of sexual compulsivity, impulsivity, and experiential avoidance in internet pornography use. The Psychological Record, 62(1), 3–18. doi:10.1007/BF03395783

- Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S. L. (2018). Unbuckling the Bible belt: A state-level analysis of religious factors and google searches for porn. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 273–283. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1278736

- Whitfield, T. H., Rendina, H. J., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). Viewing sexually explicit media and its association with mental health among gay and bisexual men across the US. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1163–1172. doi:10.1007/s10508-017-1045-y

- Williams, K. M., Cooper, B. S., Howell, T. M., Yuille, J. C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Inferring sexually deviant behavior from corresponding fantasies: The role of personality and pornography consumption. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(2), 198–222. doi:10.1177/0093854808327277

- Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., Nelson, L. J., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2014). Associations between relational sexual behaviour, pornography use, and pornography acceptance among US college students. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(9), 1052–1069. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.927075

- Wood, H. (2011). The internet and its role in the escalation of sexually compulsive behaviour. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 25(2), 127–142. doi:10.1080/02668734.2011.576492

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- Wright, P. J., & Randall, A. K. (2012). Internet pornography exposure and risky sexual behavior among adult males in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(4), 1410–1416. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.003

- Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237–244. doi:10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237

- Zattoni, F., Gül, M., Soligo, M., Morlacco, A., Motterle, G., Collavino, J., Barneschi, A. C., Moschini, M., & Moro, F. D. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pornography habits: A global analysis of google trends. International Journal of Impotence Research, 33(8), 824–831. doi:10.1038/s41443-020-00380-w.