Abstract

This article examines the clinical aspects of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) and psychotherapeutic approaches to the disorder. The aim of this narrative review is to define what components of an integrated group therapy approach are required when delivering treatment for CSBD. This is done by synthesizing the elements of theory, practice, and psychotherapeutic intervention required when delivering support in relation to CSBD within group settings. Although discussed in psychological literature for years, treatment literature on CSBD lacks sufficient evidence-based approaches to develop a clear framework for implementing therapy styles and continues to defy easy categorization. The literature review of the clinical aspects of CSBD demonstrates that there is substantial heterogeneity within the disorder.

Introduction

Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder is an evolving public health issue (Fuss, Briken, Stein, & Lochner, Citation2019). To date it has encompassed problematic sexual behavior, sexual compulsivity, nonparaphilic compulsive behavior, paraphilia-related disorder, impulsive sexual behavior/sexual impulsivity, sexual addiction and out of control sexual behavior (Briken, Citation2020). The various terms put forward different, albeit often overlapping, psychological mechanisms relating to sexual behavior. The most recent edition of its International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) included Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) as an impulse disorder, described therein as being “characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior” (ICD-11, 2022). CSBD is characterized by an increased frequency and intensity of sexually motivated fantasies, arousal, urges, and enacted behavior in connection with a compulsivity component—a maladaptive behavioral reaction with adverse repercussions (Reed et al., Citation2022).

In the general adult population, the prevalence of CSB is thought to be between 3% and 6%. These are only rough estimates since underreporting owing to shame or embarrassment is probably a result of the private nature of sex and the ongoing stigma associated with these behaviors (Dickenson, Gleason, Coleman, & Miner, Citation2018). However, these studies range in methodological approaches and quality. In addition, the varying and evolving conceptualization of the behavior and lack of universally accepted screening tools has meant estimating the prevalence of CSBD in adults is challenging. CSBD is linked to increased risk-taking behavior’s, such as substance abuse, having multiple partners or unprotected sex, depression and anxiety, impulsivity, loneliness, low self-worth, and insecure attachment styles (Dhuffar & Griffiths, Citation2015; Rosenberg, Carnes, & O'Connor, Citation2014; Sussman, Lisha, & Griffiths, Citation2011).

In recent years CSBD has become a prominent concept in sexual health discourse and research (Grubbs et al., Citation2020). CSBD has been linked to childhood trauma and a history of abuse (Labadie, Godbout, Vaillancourt-Morel, & Sabourin, Citation2018; Aaron, 2012; Easton, Coohey, O’leary, Zhang, & Hua, Citation2010), as well as insecure attachment styles (Labadie et al., Citation2018; Zapf, Greiner, & Carroll, Citation2008). Additionally, the increasing use of digital and online sexual stimuli has increased the opportunity for the development of CSBD in the context of compulsive porn consumption and masturbation (Caponnetto, Maglia, Prezzavento, & Pirrone, Citation2022; Hall, Citation2018).

Co-morbid psychological and substance use disorders are common with CSBD (Kuzma & Black, Citation2008; Bőthe et al., Citation2019; Williams, Citation2006; Wéry et al., Citation2016), with many people with CSBD reporting psychological distress, anxiety, shame, and other negative symptoms because of the behavior (Dickenson et al., Citation2018). The varying theoretical conceptualizations of CSBD (addiction, compulsion, hypersexuality etc.) used by researchers are significant as they potentially impact the treatment received. Due to the complex nature of CSBD, it has been widely proposed that a comprehensive treatment approach must be taken to its psychotherapeutic treatment that allows for biological, social, and psychological influences to be addressed (Levine, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2013a). Several modified biopsychosocial approaches to treatment incorporating Engel’s (1977) traditional model with principles from the addiction model, the sex positive framework and the sexual health model have been proposed (Hall, Citation2018; Braun-Harvey & Vigorito, Citation2016; Coleman, Citation2015; Grant & Potenza, Citation2011). Group therapy is a usual form of therapeutic treatment suggested by many of these approaches, as it allows clients suffering from CSBD to reduce their shame and isolation in a supportive environment while developing new relationships with peers (Borgogna, Garos, Meyer, Trussell, & Kraus, Citation2022; Hallberg et al., Citation2019). The debilitating impact that CSBD can have on a considerable proportion of the population indicates a considerable need for research and treatment in the area (Dickenson et al., Citation2018). The CSBD literature lacks examples of explicit applications of evidence-based practice models in the development and assessment of clinical interventions. The objective of this narrative review is to begin filling that gap and aims to understand what components of an integrated group therapy approach are required to deliver treatment for CSBD.

Method

Search strategy

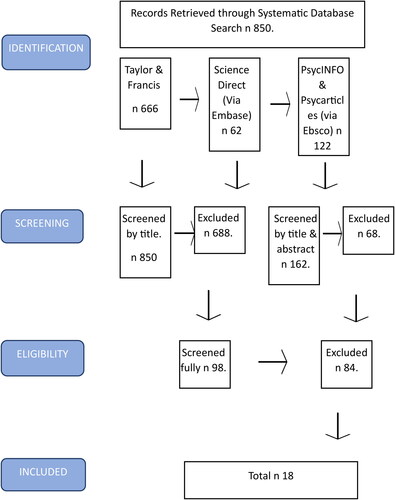

A narrative synthesis approach was applied due to the heterogeneity of methodological approaches within this research field. This methodology facilitates differing methodologies, approaches, and the synthesis of evidence effectiveness that relies primarily on a textual approach to summarize and explain the findings of multiple studies (Popay, Roberts, Snowden, Petticrew, & Duffy, Citation2006). A systematic literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PsychINFO, PsychArticle, Science Direct, and Taylor and Frances. Specifically, PsychINFO was chosen for this research because it is the world’s largest resource of peer-reviewed literature in behavioral and social science (EBSCO info services, Citation2021). The following search terms were used: “Problematic sexual behavior” OR “sexual compulsion” OR “problematic pornography consumption” OR “compulsive sexual behavior disorder” OR “sex addiction” OR “impulsive sexual behavior” OR “love addiction” AND “Adult” OR “young adult” OR “adult males” OR “adult females” AND “Therapeutic intervention” OR “psychotherapy” OR “therapy” OR “group therapy” OR “treatment” OR “integrated model” OR “addiction counselling.” Two coauthors reviewed relevant titles and abstracts published between January 1990 to July 2022. Each database was searched in a 48-h period using the predefined search terms. Due to the nature of this type of research, ethical approval and review was not required.

Review, eligibility and selection

Articles published in English between January 1990 and July 2022 were included in the review if they were (1) peer reviewed journal articles, (2) related to problematic sexual behavior in adults, (3) focused on psychotherapeutic interventions for problematic sexual behavior, (4) adopted a biopsychosocial or attachment theory-driven approach to treatment. English language content was chosen to ease assessment by a native English-speaking research team. Peer-reviewed content was employed to identify international best practice regarding therapeutic approaches to CSBD, using quantitative, qualitative, and theoretical studies were included to ensure a robust representation. Publications beginning from 1990 were chosen as research on sexual dysfunctions has increased in the last 30 years, especially around CSBD (Simons & Carey, Citation2001).

Exclusion criteria included (1) children and adolescents, (2) sex offending, (3) non-therapeutic interventions including pharmacology and support groups and (4) cognitive behavioral models. Data from the search strategy of online databases yielded 850 results, these were assessed for duplicates and 688 were excluded. A further 66 records were excluded from reviewing the abstracts because these studies did not meet inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 98 studies were examined, and 18 were considered relevant. A PRISMA flow diagram presents the results in .

Data analysis

The papers comprised of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method study designs. There was a large degree of heterogeneity between included studies. It is not appropriate to conduct meta-analysis on studies that are at risk of bias or are too diverse, as the results can be misleading (Greco et al., Citation2013). As such a narrative synthesis technique was employed using the Popay et al. (Citation2006) framework. Narrative synthesis uses words, text, and numbers to summarize and explore data from both quantitative and qualitative studies (Popay et al., Citation2006). Recommendations were followed about using specified search methods and organizing the output as a synthesis, to ‘tell a story’ (Popay et al., Citation2006). The results sections of each paper were analyzed to identify information around the process involved in the psychotherapeutic treatment of CSBD in adults. First, a preliminary synthesis was developed. The same relevant data was extracted from all papers and tabulated. A content analysis with an inductive approach was then conducted which allowed categories to emerge from the data (See ).

Table 1. Complete summary of all papers included in the present review.

Results

Review description

In total, 18 studies were included in the final narrative synthesis. They included three qualitative (Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Benfield, Citation2018; Giugliano, Citation2006), five quantitative (Reid, Bramen, Anderson, & Cohen, Citation2014; Holas, Draps, Kowalewska, Lewczuk, & Gola, Citation2020; Reid, Carpenter, & Lloyd, Citation2009; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Droubay et al., Citation2020);, one mixed-methods (Lundy, Citation1994), twosystematic reviews (Sanches & John, Citation2019; Garcia et al., Citation2016), four narrative review papers (Coleman et al., Citation2018; Woehler, Giordano, & Hagedorn, Citation2018; Hall, Citation2011; Sussman, Citation2010) and three expert-review papers (Hook, Hook, & Hines, Citation2008; Herring, Citation2017; Hall, Citation2013b). All papers were critically appraised for quality as well as their alignment with the research aim. Four main categories were derived from the content analysis.

Category 1: Defining assessment and classification

The classification of CSBD has been recognized as an important step toward addressing clinical needs of clients, to empower clinicians in their work treating clients with CSBD, and for those who study psychological and neurobiological mechanisms of CSBD to improve treatment and prevention (Gola & Potenza, Citation2018). Nonetheless, there are still some open questions with regards to specific definitions within the classification and the practical application.

Conceptualization of CSBD is different across included studies. In the 18 studies included, one defined the behavior as problematic sexual behavior (Herring, Citation2017), one classified the behavior as impulsive/compulsive sexual behavior (Coleman et al., Citation2018), one as out-of-control sexual behavior (Giugliano, Citation2006), two as love addiction (Sussman, Citation2010; Sanches & John, Citation2019), nine as sexual addiction with one including pornography addiction (Hall, Citation2013b; Lundy, Citation1994; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Benfield, Citation2018; Woehler et al., Citation2018), two as hypersexuality (Reid et al., Citation2009; Reid et al., Citation2014), one as compulsive sexual behavior disorder (Holas et al., Citation2020) and one as problematic pornography use (Droubay et al., Citation2020). These classifications include ICD-11 classified disorders, addiction, and impulsive behavior conceptualizations of CSBD.

Of the eighteen studies included, eight indicated that assessment and classification are essential components of understanding and providing adequate treatment to people experiencing CSBD (Lundy, Citation1994; Reid et al., Citation2009; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013b; Giugliano, Citation2006; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Herring, Citation2017; Hook et al., Citation2008). Most of these studies (n = 6) referred to the importance of a therapist assessing (i) why the behavior is problematic to the person, referring to the (ii) negative consequences and psychological symptoms associated with their behavior, which is often what decides (iii) if a client needs intensive therapeutic treatment (Reid et al., Citation2009; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013b; Giugliano, Citation2006; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Herring, Citation2017). It was also acknowledged in three of these eight studies that (iv) assessment is important to identify what issues will need to be addressed in therapy, both in terms of behavior and underlying causes, and to (v) assert a clients’ readiness for treatment (Coleman et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2013b; Hook et al., Citation2008). Half of the eight studies (n = 4) also classified the types of CSBD, from problematic pornography consumption to excessive fantasy, and more importantly the reasons that people may engage in them, such as desire for connection or experiential avoidance (Giugliano, Citation2006; Herring, Citation2017; Hall, Citation2013b; Lundy, Citation1994). There was some overlap with discussion of both assessment and classification, with one of the eight mentioning all three of these subcategories (Hall, Citation2013b) and two of the eight mentioning two of the subcategories (Giugliano, Citation2006; Coleman et al., Citation2018).

Category 2: Understanding the origins of problematic sexual behavior

The risk of CSB among people is influenced by a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors rather than by a single cause. Risk factors include genetics, biology, issues with mental health, trauma, social norms, and attachment style. The potential causes of CSB are investigated in psychotherapy. "Early childhood trauma, shame, guilt, avoidance, anger, and impaired self-esteem and self-efficacy" are among the fundamental themes (Walton, Citation2017). It is important there is an exploration of how the client forms and maintains intimate relationships and the meaning of their sexual and romantic behavior (Walton, Citation2017). According to Efrati, Shukron, and Epstein (Citation2019), psychodynamic therapy focuses on the intrapsychic and interpersonal dynamics that affect a person’s sexual behaviors and desires in relation to their past and present relationships, including their relationship with the therapist. Additionally, it recognizes and addresses potential "therapy-interfering" behaviors that could have a negative impact on the treatment of CSBD (Efrati et al., Citation2019).

To provide therapeutic treatment to clients with CSBD, most studies (n = 12) highlighted the importance of understanding from where the compulsion to engage in this behavior originated. Long-term, intensive group therapy can be a way of uncovering and working through these issues as well as eliminating the CSBD. Studies mentioned factors such as trauma, attachment issues, origin family dysfunction, emotional regulation, shame, experiential avoidance and coping as examples of deeply ingrained influences contributing to CSBD. Of the eighteen included studies, twelve mentioned origins of problematic behavior and the importance of understanding their role in the development of a clients CSBD (Giugliano, Citation2006; Herring, Citation2017; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013b; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Droubay et al., Citation2020; Benfield, Citation2018; Woehler et al., Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018). Trauma was highlighted as being a major underlying cause of CSBD development in seven of the studies, referring to child abuse and neglect (Giugliano, Citation2006; Hall, Citation2013b; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Droubay et al., Citation2020; Coleman et al., Citation2018). Similarly, seven studies mentioned emotional regulation issues (Giugliano, Citation2006; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Droubay et al., Citation2020; Woehler et al., Citation2018; Benfield, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018) and four studies mentioned coping or self-soothing as a driving force behind CSBD (Giugliano, Citation2006; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Hall, Citation2013b; Hall, Citation2011). Five mentioned shame as key contributing factors to engagement in CSBD (Hall, Citation2011; Droubay et al., Citation2020; Herring, Citation2017, Garcia et al., Citation2016; Hall, Citation2013b). Dysfunction in the family of origin was also highlighted by five papers as rupturing a client’s model of intimacy, often leading to the development of CSBD (Hall, Citation2013b; Hook et al., Citation2008; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Sussman, Citation2010; Benfield, Citation2018). Attachment issues (i.e. an insecure attachment) was discussed as a source of CSBD in six studies (Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013b; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Benfield, Citation2018), meanwhile one study mentioned experiential avoidance (Giugliano, Citation2006). Half of these eighteen studies (n = 9) mentioned more than one origin factor for the development of CSBD, indicating that they are integrated and complex elements of CSBD (Giugliano, Citation2006; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2013b; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Kotera & Rhodes, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2011; Droubay et al., Citation2020; Benfield, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018)

Category 3: Navigating relationship development

Compulsive sexual behavior can be both a cause and a consequence of ruptured relationships, often stemming from insecure attachment styles and leading to issues with spouses and family. Compulsive sexual behavior arises when a person is searching for intimacy or connection but lacks communication skills and healthy relationship models. When a client comes to therapy for CSBD, they are very often isolated due to damaged relationships and little understanding of how to develop healthy ones. Clinicians who treat CSB have proposed that authentic interaction with other recovering individuals within a group setting can be particularly therapeutic for individuals with CSB, as it gives them an opportunity to learn to build intimate healthy relationships with other individuals (Benfield, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018).

References to relationships and intimacy development arose in eleven of the eighteen studies (Woehler et al., Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Benfield, Citation2018; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2011; Hall, Citation2013b; Sanches & John, Citation2019; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Hook et al., Citation2008; Giugliano, Citation2006; Garcia et al., Citation2016), all of which referred to the importance of the relationship with the therapist and members of the therapy group. Furthermore, nine of the eleven studies discuss how these therapeutic relationships can act as healthy relationships to be modeled in relationships outside of therapeutic groups (Woehler et al., Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Benfield, Citation2018; Sussman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2011; Hall, Citation2013b; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016). These intimate but non-sexual reparative relationships can begin to heal attachment issues that are so common with CSBD clients so that they can learn to have more secure relationships outside of therapy. In addition to this, five out of eleven studies highlighted that the search for connection which often drives CSBD can be addressed by developing healthy relationships within therapy and consequentially outside of the groups (Woehler et al., Citation2018; Giugliano, Citation2006; Hall, Citation2011; Benfield, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018).

Therapeutic group relationship development can play a particularly significant role in the life of a client with CSBD. It was highlighted in six of the eleven studies that therapist and group relationships can develop much needed social skills with others that can help with external relationship building, such as communication skills, boundary management and the ability to be vulnerable (Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Woehler et al., Citation2018; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Hook et al., Citation2008; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Sussman, Citation2010). Moreover, these relationships provide a source of support with people who understand the client during treatment, as was mentioned in five studies (Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Hook et al., Citation2008; Benfield, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018).

Category 4: Utilizing an integrated therapeutic approach

Therapeutic treatment for CSBD requires a unique, integrated approach that addresses the multi-faceted origins and presentations of the behavior. The therapeutic approach draws on both addiction and psychotherapeutic methods to eliminate problematic behavior patterns and to work through the causal factors that lead to the person’s issues with intimacy and emotional regulation. The present review found that eleven out of eighteen papers mentioned the therapeutic approach and techniques that must be utilized to treat CSBD (Hall, Citation2013b; Benfield, Citation2018; Hall, Citation2011; Sanches & John, Citation2019; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Woehler et al., Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Holas et al., Citation2020; Reid et al., Citation2014). Theoretical psychological models such as the biopsychosocial model, OAT (Opportunity, Attachment and Trauma) model and attachment theory were referred to in five of the eleven studies to inform the approaches that should be taken by therapists (Hall, Citation2013b; Benfield, Citation2018; Hall, Citation2011; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Coleman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, four of these eleven studies explicitly recommended that treatment should be intensive and long-term, to effectively address the addictive or compulsive process and develop intimacy and relationship skills (Hall, Citation2013b; Benfield, Citation2018; Hook et al., Citation2008; Coleman et al., Citation2018). Psychoeducation is also highlighted in two of these studies as an effective way of helping individuals to understand their behavior patterns and how it relates to the negative consequences they experience (Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Coleman et al., Citation2018).

Several key therapeutic techniques were highlighted as being essential for use in group therapy for CSBD. Mindfulness or maintaining a present moment focus was mentioned in a majority of the eleven studies (n = 8), suggesting that it is a key element of the therapeutic work (Hall, Citation2013b; Benfield, Citation2018; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Woehler et al., Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Holas et al., Citation2020; Reid et al., Citation2014). On a related note, bringing awareness to both internal (emotional and psychological) and physical experiences was emphasized in six of the eleven studies, with three mentioning both internal and physical experiences (Benfield, Citation2018; Woehler et al., Citation2018 and Garcia et al., Citation2016), two mentioning only internal awareness (Hook et al., Citation2008; Coleman et al., Citation2018) and one mentioning only physical awareness (Hall, Citation2013b). Addressing the origins of CSBD in therapeutic groups (see Category 2 for origins) was highlighted as a key process in therapy by six of the eleven studies (Hall, Citation2011, Benfield, Citation2018, Hall, Citation2013b; Sanches & John, Citation2019; Garcia et al., Citation2016; Coleman et al., Citation2018), with shame reduction being specifically mentioned by three studies (Hall, Citation2011; Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Garcia et al., Citation2016). Empathy was also noted as an important therapeutic aspect necessary for successful work, particularly for attachment healing, in three of eleven studies (Benfield, Citation2018; Hall, Citation2011; Woehler et al., Citation2018;).

In terms of minimizing a person’s CSBD and its negative impact on their life, encouraging clients to take accountability for their behavior is a key first step in the therapeutic process, highlighted by three of the eleven studies (Hall & Larkin, Citation2020; Hook et al., Citation2008; Garcia et al., Citation2016). Developing a behavior management plan separate for the external world was also mentioned by two of the eleven studies (Hall, Citation2011; Hook et al., Citation2008), although much of the reparative process relates to a person’s intimacy and relationship development as aforementioned in Category 3.

A theoretical framework for treatment of CSB can be based on an understanding of the underlying addictive process and the compulsive dependence on external actions as a means of regulating one’s internal states. CSB should be addressed through behavioral management, which includes relapse prevention and other techniques such as psychoeducation. The compulsive and addictive process is addressed by enhancing self-regulatory functions through individual psychotherapy and therapeutic group experience. An integrated system for treatment of sexual addiction, which brings together these therapeutic methods in one theoretically coherent, clinically unified approach is suggested.

Discussion

The current review provides a framework of an integrated, group psychotherapeutic process for CSBD indicating the importance of defining assessment and classification; understanding the origins of problematic behavior; navigating relationship development; and utilizing an integrated therapeutic approach. The current framework can facilitate effective support service delivery, ensuring people with CSBD are supported equitably.

These findings indicate that a clear classification of CSBD in terms of its conceptualization and underlying models, as well as how CSBD is assessed in a person seeking treatment, is a core element of the therapeutic treatment of CSBD. Differences in the classification of CSBD have posed an issue in this field for some time, as conceptualizations are associated with varying underlying models and theories which have prevented a clear diagnosis and treatment approach from developing (Moser, Citation2013; Ley, Citation2014; Kaplan & Krueger, Citation2010; Coleman et al., Citation2018; Rosenberg et al., Citation2014). Schaefer and Ahlers (Citation2017) suggest that “problem-causing sexual behaviour” encapsulates the phenomenon and its impact most effectively in a way that allows for overlap of conflicting conceptualizations (e.g. addictive, compulsive, impulsive, hypersexuality, out-of-control) and focuses on the core behavior to allow for CSBD to be viewed in research comprehensively. Furthermore, while behaviors such as compulsive masturbation or excessive porn consumption are noted as common problematic sexual behaviors, the literature across conceptualizations maintains that any repeated sexual behavior that has a negative impact on a person’s life can be classified as CSBD (Rosenberg et al., Citation2014). Assessment for treatment for CSBD is also particularly important as the research suggests, with several psychometric measures assessing equivalent properties available to assist with assessment, with therapists choosing to use different assessment measures depending on which conceptualization of CSBD they operate by (Montgomery-Graham, Citation2017). A clear definition for CSBD is essential to assess a client appropriately, avoid misdiagnosis of non-problematic sexual behaviors and provide adequate therapeutic treatment for the situation of the client (Hall, Citation2012; Carnes & Wilson, Citation2002; Grubbs, Hook, Griffin, Penberthy, & Kraus, Citation2017).

The findings of this review also highlight that understanding the origins of CSBD is an essential component of treatment. Extensive research has linked childhood trauma, including adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and physical or sexual abuse, to the development of CSBD in adulthood (Schwartz & Southern, Citation2000; Slavin, Scoglio, Blycker, Potenza, & Kraus, Citation2020; Kafka, Citation2010; Kuzma & Black, Citation2008; Carries & Delmonico, Citation1996; Kowalewska, Gola, Kraus, & Lew-Starowicz, Citation2020; Meyer, Cohn, Robinson, Muse, & Hughes, Citation2017; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Citation2015). Similarly, insecure attachment styles (Bowlby, Citation1973; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978), often associated with childhood abuse and trauma, has been repeatedly highlighted as a developmental reason contributing to CSBD in adulthood, tying into theories of intimacy dysregulation and relationship avoidance (Faisandier, Taylor, & Salisbury, Citation2012; Butler & Seedall, Citation2006; Creeden, Citation2004; Zapf et al., Citation2008; Weinstein, Katz, Eberhardt, Cohen, & Lejoyeux, Citation2015; Samenow, Citation2010). The present review’s findings also suggested that emotional dysregulation is a feature commonly seen in people with CSBD which can contribute to its occurrence and maintenance, suggesting that people may engage in CSBD as a maladaptive coping strategy for negative emotions, thoughts, and impulses (Lew-Starowicz, Lewczuk, Nowakowska, Kraus, & Gola, Citation2020; Dhuffar, Pontes, & Griffiths, Citation2015; Reid, Berlin, & Kingston, Citation2015; Adams & Robinson, Citation2001). Notably, numerous studies mentioned shame as a key underlying contributor to CSBD which is a common theme in the previous literature, referring to the inherent belief of a person that they are a bad person impacting upon their perceived self-identity (Dearing, Stuewig, & Tangney, Citation2005; Sassover et al., Citation2021; Reid, Citation2010; Walton, Cantor, Bhullar, & Lykins, Citation2017).

The ability to navigate and develop healthy relationships is an aspect of daily living (Berscheid & Regan, Citation2016). The current findings signal supporting individuals with CSBD in the context of potential attachment and trauma issues is crucial in any potential therapeutic approach. People experiencing CSBD often use the behavior to satisfy their need for intimacy or connection (Schaumberg, 2019; Carnes & Wilson, Citation2002). The relationship between a therapist and client is always of critical importance in a psychotherapeutic scenario and the therapist must ensure they are listening and mediating the relationship based on the needs of the client (Norcross, Citation2010). In therapy for CSBD where much healing attachment work will occur, the relationship between client and therapist can be instrumental in one’s modeling of a healthy, empathic relationship (Levy, Citation2013; Levine, Citation2012; Katehakis, Citation2016; Hall, Citation2012; Coleman, Citation2011). Group psychotherapy is a popular treatment option for people with behavioral addictions such as CSBD (Hall, Citation2018; Miller, Citation2020). It allows for development of relationships in a safe therapeutic environment (Rosenberg et al., Citation2014; Karila et al., Citation2014; Adams & Robinson, Citation2001); reduction of shame and isolation (Schreiber, Odlaug, & Grant, Citation2012) as well as social skills (Riemersma & Sytsma, Citation2013), as was mirrored in the findings of the present review.

Finally, the findings of this review contribute to a growing field of research regarding the integrated therapeutic approach that should be taken to treatment of CSBD. There are varying suggestions as to what therapeutic approach is most effective, impacted by the different diagnostic conceptualizations for CSBD that have existed over the years, but a biopsychosocial view of CSBD has been accepted across definitions (Levine, Citation2012; Phillips, Hajela, & Hilton, Citation2015; Samenow, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2011, Citation2013a). Furthermore, initial work in attachment-informed integrated therapy for CSBD suggests that utilizing an integrated therapeutic approach that includes attachment, trauma and affect regulation work could be optimal in this area (e.g. Adams & Robinson, Citation2001; Hall, Citation2012; Katehakis, Citation2016; Chisholm & Gall, Citation2015; Blycker & Potenza, Citation2018; Coleman et al., Citation2018). However, taking an attachment-based approach to therapy is relatively new and hence there is little research conducted in this area, so there is a need for randomized control trials to truly evaluate its impact. Due to the deeply embedded impact that childhood abuse or attachment issues can have, long-term therapy is often the recommended approach to give time for the therapist to get to the deeply rooted causes of the CSBD and allow the alliance between therapist and client or group to develop (Rosenberg et al., Citation2014; Levine, Citation2012).

Strengths and limitations of this review

This review gives an overview of best practice in relation to what components of an integrated group therapy approach are required when delivering treatment for CSBD. The review was based on a thorough search of available literature which identified many potentially eligible studies, and which were synthesized by multiple sources, offering a reduction in bias in the findings. The search strategy was also conducted using four different search engines to access journals with a varying behavioral and therapeutic focus. To ensure data quality, article screening and data extraction were completed independently by two persons to avoid subjective bias, with disagreements resolved through discussion. The review also employed standard methods for systematic reviews in accordance with the preferred reporting guidelines for systematic reviews (PRISMA) (Prisma-statement.org, 2015).

This review had several limitations. Only four databases were systematically searched for eligible papers, which may have excluded potentially relevant papers not featured in these systems. The included studies were published, peer reviewed studies in English and are thus susceptible to publication bias. The inclusion of studies of varying quality could also yield misleading results. This review also excluded grey literature (reports, conference proceedings, or dissertations) and was limited to research from January 1990 to July 2022. Furthermore, a range of diverse types of article types were included (not simply quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method studies) since research around integrated group therapy for CSBD is scarce. Moreover, due to the lack of a uniform standard terminology for sex addiction some information may have been missed Finally, different critical appraisal tools were utilized due to the varying format of each paper, which may have impacted the quality appraisal process. Future research should include randomized control trials about the effectiveness of long-term, integrated, group psychotherapy for people experiencing CSBD.

Conclusion

This paper has shown that therapeutic treatment for CSBD requires a unique, integrated approach that addresses the multi-faceted origins and presentations of the behavior. The therapeutic approach draws on both addiction and psychotherapeutic methods to disengage from the problematic behavior patterns and to work through the causal factors that lead to intimacy and emotional regulation issues. This research has highlighted two core elements of the therapeutic treatment of CSBD: (i) the need for a clear classification of CSBD in terms of conceptualization, as conceptualizations are corelated with differing underlying models and theories and (ii) the use of assessments in conjunction with long-term, intensive group therapy as a way of uncovering the origins of CSBD and developing a behavior management plan for use in recovery and prevention of relapse from CSBD. When a client comes to therapy for CSBD, they are very often isolated due to broken relationships and little understanding of how to develop healthy intimate relationships. CSBD often stems from insecure attachment styles, however, through group work and peer support clients can develop communication skills and healthy relationship models.

There is an ongoing discussion about the proper categorization of CSBD. CSBD is a common disorder that has significant personal and public health ramifications. Although there are a variety of psychosocial treatments which have shown early promise in the treatment of CSBD, more evidence-based treatment options are needed (Borgogna et al., Citation2022. Education regarding sexual compulsivity may advance the understanding of this often-disabling disorder. The current work provides an evidence-based framework that can be used in training and evidence-based interventions to deliver support to this often-marginalized group in support services. Results may be informative for future research and the development of specific treatment programs for CSBD.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, L., & Robinson, D. (2001). Shame reduction, affect regulation, and sexual boundary development: Essential building blocks of sexual addiction treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 8(1), 23–44. doi:10.1080/10720160127559

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment; a psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., revised). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. (2011). Public policy statement: Definition of addiction. Available at: http://www.asam.org/for-the-public/definition-of-addiction. [Accessed 02 Aug. 2022].

- Benfield, J. (2018). Secure attachment: An antidote to sex addiction? A thematic analysis of therapists’ experiences of utilizing attachment-informed treatment strategies to address sexual compulsivity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(1), 12–27. doi:10.1080/10720162.2018.1462746

- Berscheid, E. S., & Regan, P. C. (2016). The psychology of interpersonal relationships. New York: Psychology Press. doi:10.4324/9781315663074

- Blycker, G. R., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). A mindful model of sexual health: A review and implications of the model for the treatment of individuals with compulsive sexual behavior disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 917–929. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.127

- Borgogna, N. C., Garos, S., Meyer, C. L., Trussell, M. R., & Kraus, S. W. (2022). A review of behavioral interventions for compulsive sexual behavior disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 9(3), 99–108. doi:10.1007/s40429-022-00422-x

- Bőthe, B., Koós, M., Tóth-Király, I., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2019). Investigating the associations of adult ADHD symptoms, hypersexuality, and problematic pornography use among men and women on a largescale, non-clinical sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(4), 489–499. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.312

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Braun-Harvey, D., & Vigorito, M. A. (2016). Treating out of control sexual behavior: Rethinking sex addiction (pp. xvi, 435). New York: Springer Publishing Company. doi:10.1891/9780826196767

- Briken, P. (2020). An integrated model to assess and treat compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Nature Reviews. Urology, 17(7), 391–406. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0343-7

- Butler, M. H., & Seedall, R. B. (2006). The attachment relationship in recovery from addiction. Part 1: Relationship mediation. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13(2–3), 289–315. doi:10.1080/10720160600897581

- Caponnetto, P., Maglia, M., Prezzavento, G. C., & Pirrone, C. (2022). Sexual addiction, hypersexual behavior and relative psychological dynamics during the period of social distancing and stay-at-home policies due to COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2704. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052704

- Carnes, P. J. (2001). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction (3rd ed). Minnesota: Hazelden Publishing.

- Carnes, P. J., & Wilson, M. (2002). The sexual addiction assessment process. In Clinical management of sex addiction (1st ed.), (Vol. 1, pp. 17–34). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203890158-8

- Carries, P. J., & Delmonico, D. L. (1996). Childhood abuse and multiple addictions: Research findings in a sample of self-identified sexual addicts. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 3(3), 258–268. doi:10.1080/10720169608400116

- Chisholm, M., & Gall, T. L. (2015). Shame and the X-rated addiction: The role of spirituality in treating male pornography addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 22(4), 259–272. doi:10.1080/10720162.2015.1066279

- Coleman, E. (2011). Impulsive/compulsive sexual behavior: Assessment and treatment. In The Oxford handbook of impulse control disorders (pp. 375–388). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, E. (2015). Impulsive/compulsive sexual behaviour. ABC of Sexual Health, 259, 93.

- Coleman, E., Dickenson, J. A., Girard, A., Rider, G. N., Candelario-Pérez, L. E., Becker-Warner, R., … Munns, R. (2018). An integrative biopsychosocial and sex positive model of understanding and treatment of impulsive/compulsive sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(2-3), 125–152. doi:10.1080/10720162.2018.1515050

- Creeden, K. (2004). The neurodevelopmental impact of early trauma and insecure attachment: Re-Thinking our understanding and treatment of sexual behavior problems. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(4), 223–247. doi:10.1080/10720160490900560

- Dearing, R. L., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 30(7), 1392–1404. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002

- Department of Health, & Healthy Ireland. (2015). National sexual health strategy 2015 – 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/8feae9-national-sexual-health-strategy/ [Accessed 02 Aug. 2022].

- Dhuffar, M. K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). A systematic review of online sex addiction and clinical treatments using CONSORT evaluation. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 163–174. doi:10.1007/s40429-015-0055-x

- Dhuffar, M. K., Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The role of negative mood states and consequences of hypersexual behaviours in predicting hypersexuality among university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 181–188. doi:10.1556/2006.4.2015.030

- Dickenson, J. A., Gleason, N., Coleman, E., & Miner, M. H. (2018). Prevalence of distress associated with difficulty controlling sexual urges, feelings, and behaviors in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184468. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4468

- Droubay, B. A., Shafer, K., & Butters, R. P. (2020). Sexual desire and subjective distress among pornography consumers. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(8), 773–792. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2020.1822483

- Easton, S., Coohey, C., O’leary, P., Zhang, Y., & Hua, L. (2010). The effect of childhood sexual abuse on psychosexual functioning during adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 26(1), 41–50. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9340-6

- EBSCO Information Services, Inc. (2021). | www.ebsco.com. APA PsychINFO | EBSCO. Available at: https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/apa-psycinfo. [Accessed 22 Aug. 2022].

- Efrati, Y., Shukron, O., & Epstein, R. (2019). Compulsive sexual behavior and sexual offending: Differences in cognitive schemas, sensation seeking, and impulsivity. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 432–441. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.36

- Faisandier, K. M., Taylor, J. E., & Salisbury, R. M. (2012). What does Attachment have to do with out-of-control sexual behaviour? https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/9478

- Fuss, J., Briken, P., Stein, D. J., & Lochner, C. (2019). Compulsive sexual behavior disorder in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Prevalence and associated comorbidity. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 242–248. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.23

- Garcia, F. D., Assumpção, A. A., Malloy-Diniz, L., De Freitas, A. A. C., Delavenne, H., & Thibaut, F. (2016). A comprehensive review of psychotherapeutic treatment of sexual addiction. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 11(1), 59–71. doi:10.1080/1556035X.2015.1066726

- Giugliano, J. (2006). Out of control sexual behavior: A qualitative investigation. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13(4), 361–375. doi:10.1080/10720160601011273

- Gola, M., & Potenza, M. (2018). The proof of the pudding is in the tasting: Data are needed to test models and hypotheses related to compulsive sexual behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(5), 1323–1325. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1167-x

- Grant, J. E., & Potenza, M. N. (2011). The Oxford handbook of impulse control disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Greco, T., Zangrillo, A., Biondi-Zoccai, G., & Landoni, G. (2013). Meta-analysis: Pitfalls and Hints. Heart, Lung and Vessels, 5(4), 219–225.

- Grubbs, J. B., Hoagland, K. C., Lee, B. N., Grant, J. T., Davison, P., Reid, R. C., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Sexual addiction 25 years on: A systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101925. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925

- Grubbs, J. B., Hook, J. N., Griffin, B. J., Penberthy, J. K., & Kraus, S. W. (2017). Clinical assessment and diagnosis of sexual addiction. In The Routledge international handbook of sexual addiction (pp. 167–180). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hall, P. (2011). A biopsychosocial view of sex addiction. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(3), 217–228. doi:10.1080/14681994.2011.628310

- Hall, P. (2012). Understanding and treating sex addiction: A comprehensive guide for people who struggle with sex addiction and those who want to help them. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203080900

- Hall, P. (2013a). Sex addiction – An extraordinarily contentious problem. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(1), 68–75. doi:10.1080/14681994.2013.861898

- Hall, P. (2013b). A new classification model for sex addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(4), 279–291. doi:10.1080/10720162.2013.807484

- Hall, P. (2018). Understanding and treating sex and pornography addiction: A comprehensive guide for people who struggle with sex addiction and those who want to help them. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351112635

- Hall, P., & Larkin, J. (2020). A thematic analysis of clients’ reflections on the qualities of group work for sex and pornography addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 27(1–2), 1–11. doi:10.1080/10720162.2020.1751360

- Hallberg, J., Kaldo, V., Arver, S., Dhejne, C., Jokinen, J., & Öberg, K. G. (2019). A randomized controlled study of group-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersexual disorder in men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(5), 733–745. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.005

- Herring, B. (2017). A framework for categorizing chronically problematic sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 24(4), 242–247. doi:10.1080/10720162.2017.1394947

- Holas, P., Draps, M., Kowalewska, E., Lewczuk, K., & Gola, M. (2020). A pilot study of mindfulness-based relapse prevention for compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 1088–1092. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00075

- Hook, J. N., Hook, J. P., & Hines, S. (2008). Reach out or act out: Long-term group therapy for sexual addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 15(3), 217–232. doi:10.1080/10720160802288829

- Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. doi:10.1007/510508-009-9574-7

- Kaplan, M. S., & Krueger, R. B. (2010). Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 47(2), 181–198. doi:10.1080/00224491003592863

- Karila, L., Wery, A., Weinstein, A., Cottencin, O., Petit, A., Reynaud, M., & Billieux, J. (2014). Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: Different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4012–4020. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990619

- Katehakis, A. (2016). Sex addiction as affect dysregulation: A neurobiologically informed holistic treatment (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Kotera, Y., & Rhodes, C. (2019). Pathways to sex addiction: Relationships with adverse childhood experience, attachment, narcissism, self-compassion and motivation in a gender-balanced sample. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(1-2), 54–76. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1615585

- Kowalewska, E., Gola, M., Kraus, S. W., & Lew-Starowicz, M. (2020). Spotlight on compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A systematic review of research on women. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 2025–2043. doi:10.2147/NDT.S221540

- Kuzma, J. M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Epidemiology, prevalence, and natural history of compulsive sexual behavior. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31(4), 603–611. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.005

- Labadie, C., Godbout, N., Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., & Sabourin, S. (2018). Adult profiles of child sexual abuse survivors: Attachment insecurity, sexual compulsivity, and sexual avoidance. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(4), 354–369. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405302

- Levine, S. B. (2012). Problematic sexual excesses. Neuropsychiatry, 2(1), 69–79. doi:10.2217/npy.11.70

- Levy, K. N. (2013). Introduction: Attachment theory and psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(11), 1133–1135. doi:10.1002/jclp.22040

- Lew-Starowicz, M., Lewczuk, K., Nowakowska, I., Kraus, S., & Gola, M. (2020). Compulsive sexual behavior and dysregulation of emotion. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(2), 191–205. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.10.003

- Ley, D. (2014). The myth of sex addiction. London, UK: Macmillan Publishers.

- Lundy, J. P. (1994). Behavior patterns that comprise sexual addiction as identified by mental health professionals. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 1(1), 46–56. APA doi:10.1080/10720169408400027

- Meyer, D., Cohn, A., Robinson, B., Muse, F., & Hughes, R. (2017). Persistent complications of child sexual abuse: Sexually compulsive behaviors, attachment, and emotions. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 140–157. doi:10.1080/10538712.2016.1269144

- Miller, G. (2020). Learning the language of addiction counseling. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Montgomery-Graham, S. (2017). Conceptualization and assessment of hypersexual disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(2), 146–162. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.11.001

- Moser, C. (2013). Hypersexual disorder: Searching for clarity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 48–58. doi:10.1080/10720162.2013.775631

- Norcross, J. C. (2010). The therapeutic relationship. In The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed.), (pp. 113–141). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/12075-004

- Phillips, B., Hajela, R., & Hilton, D. L. (2015). Sex addiction as a disease: Evidence for assessment, diagnosis, and response to critics. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 22(2), 167–192. doi:10.1080/10720162.2015.1036184

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Snowden, A., Petticrew, … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Swindon, UK: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme.

- Reed, G. M., First, M. B., Billieux, J., Cloitre, M., Briken, P., Achab, S., … Bryant, R. A. (2022). Emerging experience with selected new categories in the ICD-11: Complex PTSD, prolonged grief disorder, gaming disorder, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. World Psychiatry : official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 21(2), 189–213. doi:10.1002/wps.20960

- Reid, R. C. (2010). Differentiating emotions in a sample of men in treatment for hypersexual behavior. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 10(2), 197–213. doi:10.1080/15332561003769369

- Reid, R. C., Berlin, H. A., & Kingston, D. A. (2015). Sexual impulsivity in hypersexual men. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 2(1), 1–8. doi:10.1007/s40473-015-0034-5

- Reid, R. C., Bramen, J. E., Anderson, A., & Cohen, M. S. (2014). Mindfulness, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, and stress proneness among hypersexual patients: Mindfulness and hypersexuality. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 313–321. doi:10.1002/jclp.22027

- Reid, R. C., Carpenter, B. N., & Lloyd, T. Q. (2009). Assessing psychological symptom patterns of patients seeking help for hypersexual behavior. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 24(1), 47–63. doi:10.1080/14681990802702141

- Riemersma, J., & Sytsma, M. (2013). A new generation of sexual addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(4), 306–322. doi:10.1080/10720162.2013.843067

- Rosenberg, K. P., Carnes, P., & O'Connor, S. (2014). Evaluation and treatment of sex addiction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(2), 77–91. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.701268

- Samenow, C. P. (2010). A biopsychosocial model of hypersexual disorder/sexual addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(2), 69–81. doi:10.1080/10720162.2010.481300

- Sanches, M., & John, V. P. (2019). Treatment of love addiction: Current status and perspectives. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 33(1), 38–44. doi:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2018.07.002

- Sassover, E., Abrahamovitch, Z., Amsel, Y., Halle, D., Mishan, Y., Efrati, Y., & Weinstein, A. (2021). A study on the relationship between shame, guilt, self-criticism, and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8347–8355. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02188-3

- Schaefer, G. A., & Ahlers, C. (2017). Sexual addiction and paraphilias. In The Routledge international handbook of sexual addiction (pp. 83–93). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315639512-8

- Schaumburg, H. (2019). False intimacy: Understanding the struggle of sexual addiction. Colorado Springs, Colo: NavPress.

- Schreiber, L. R. N., Odlaug, B. L., & Grant, J. E. (2012). Compulsive sexual behavior: Phenomenology and epidemiology. In The Oxford handbook of impulse control disorders. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195389715.013.0063

- Schwartz, M. F., & Southern, S. (2000). Compulsive cybersex: The new tea room. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7(1–2), 127–144. doi:10.1080/10720160008400211

- Sex Addiction. (2017). Psychology today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ie/basics/sex-addiction.

- Simons, J., And., & Carey, M. (2001). Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: Results from a decade of research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30(2), 177–219. doi:10.1023/A:1002729318254.

- Slavin, M. N., Scoglio, A. A. J., Blycker, G. R., Potenza, M. N., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Child sexual abuse and compulsive sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7(1), 76–88. doi:10.1007/s40429-020-00298-9

- Sussman, S. (2010). Love addiction: Definition, etiology, treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(1), 31–45. doi:10.1080/10720161003604095

- Sussman, S., Lisha, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Prevalence of the addictions: A problem of the majority or the minority? Evaluation & the Health Professions, 34(1), 3–56. doi:10.1177/0163278710380124

- Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Godbout, N., Labadie, C., Runtz, M., Lussier, Y., & Sabourin, S. (2015). Avoidant and compulsive sexual behaviors in male and female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 40, 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.024

- Walton, M. T. (2017). Sexhavior cycle [theoretical model]. School of Psychology and Behavioural Science, University of New England, Armidale, Australia.

- Walton, M. T., Cantor, J. M., Bhullar, N., & Lykins, A. D. (2017). Hypersexuality: A critical review and introduction to the ‘sexhavior cycle. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2231–2251. doi:10.1007/s10508-017-0991-8

- Weinstein, A., Katz, L., Eberhardt, H., Cohen, K., & Lejoyeux, M. (2015). Sexual compulsion-relationship with sex, attachment, and sexual orientation. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(1), 22–26. doi:10.1556/JBA.4.2015.1.6

- Wéry, A., Vogelaere, K., Challet-Bouju, G., Poudat, F.-X., Caillon, J., Lever, D., … Grall-Bronnec, M. (2016). Characteristics of self-identified sexual addicts in a behavioral addiction outpatient clinic. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 623–630. doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.071

- Williams, D. (2006). Borderline sexuality: sexually addictive behaviour in the context of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. In J. Hiller, H. Wood, & W. Bolton (Eds.), Sex, mind, and emotion: Innovation in psychological theory and practice (pp. 229–248). New York: Karnac Books.

- Woehler, E. S., Giordano, A. L., & Hagedorn, W. B. (2018). Moments of relational depth in sex addiction treatment. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(2–3), 153–169. doi:10.1080/10720162.2018.1476943

- World Health Organization. (2006). Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health (pp. 28–31). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2007). International classification of diseases (10th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-11: International classification of diseases 11th revision: The global standard for diagnostic health information. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Zapf, J. L., Greiner, J., & Carroll, J. (2008). Attachment styles and male sex addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 15(2), 158–175. doi:10.1080/10720160802035832