Abstract

Students in statistics, data science, analytics, and related fields study the theory and methodology of data-related topics. Some, but not all, are exposed to experiential learning courses that cover essential parts of the life cycle of practical problem-solving. Experiential learning enables students to convert real-world issues into solvable technical questions and effectively communicate their findings to clients.

We describe several experiential learning course designs in statistics, data science, and analytics curricula. We present findings from interviews with faculty from the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East and surveys of former students. We observe that courses featuring live projects and coaching by experienced faculty have a high career impact, as reported by former participants. However, such courses are labor-intensive for both instructors and students.

We give estimates of the required effort to deliver courses with live projects and the perceived benefits and trade-offs of such courses. Overall, we conclude that courses offering live-project experiences, despite being more time-consuming than traditional courses, offer significant benefits for students regarding career impact and skill development, making them worthwhile investments.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.1. Introduction

Courses featuring work with real data offer students the opportunity to gain hands-on experience under the guidance of experienced professors. Unlike method-oriented classroom instruction, problem-oriented courses allow students to explore different approaches to solving a specific problem. The questions posed in these courses are designed to give students a deeper understanding of the practical application of the theories and methods they have learned. Completing these courses can be valuable in preparing students for careers or graduate study (Martonosi & Williams, 2016).

Courses in which the real data exposure is via live projects (real-time and with live client interaction) expose the students to subjects not typically covered in their disciplines. These include project management, the project life cycle, effective communication and presentation skills, and the ability to identify, create and communicate value for the client organization (Hunter, 1981; Song and Zhu, 2016; Smucker and Bailer, 2015; Kolaczyk et al., 2021). Addressing questions beyond their own discipline's boundaries allows students to broaden their perspectives and gain a more holistic understanding of applications.

Martonosi and Williams (2016) discussed the advantages of statistical capstone experiences that include analysis of real data. They classified several student outcomes in three pedagogical areas: students in practicum courses see improved (1) performance as measured by test scores, retention rates, and proficiency in problem-solving; (2) job and graduate school preparation such as oral and written communication skills, collaborative skills and ability to work with nontechnical clients; and (3) student experiences such as gaining appreciation for the entire statistical analysis process, and understanding of the connections between courses.

Paloian et al. (2022) also reported on senior statistics practicum courses and reviewed the literature on practicum courses. Specifically, their work discussed student feedback from end-of-course surveys and reflections, as well as feedback from clients of the practicum projects. They also discussed the benefits of practicum courses, including improved student skill development, such as enhanced computational skills and comprehensive problem solving; soft skill development, such as teamwork, critical thinking, and communication; improved employability; and fostering engagement with external stakeholders.

Smucker and Bailer (2015) chronicled the development of a statistical consulting capstone course and provided summary examples of client projects. They noted that if properly designed, such courses can provide relevance and work-related skills to statistics students. Directed at a more general audience, Mehrotra (2013) discussed a specific course titled “Analytics Consulting Projects” targeted at Master of Business Administration (MBA) students.

Project-based courses inherently embody the principles outlined in the GAISE (Guidelines for Assessment and Instruction in Statistics Education) revised College Report by the American Statistical Association (Carver et al., 2016). The GAISE revised College Report guidelines highlight the importance of developing students' ability to analyze real data, fostering active learning, and nurturing the development of statistical thinking. Project-based courses align with these recommendations by integrating real-world projects and live client interactions. They offer students invaluable hands-on experience in data analysis, engaging them in the complete statistical investigation process — from problem formulation to data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Additionally, these courses enhance critical thinking and communication skills, essential elements of the GAISE revised College Report guidelines. This alignment reinforces the educational value of project-based courses in the data sciences and bridges the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application.

While offering valuable experience and exposure to a wide range of practical skills, experiential courses also require significant time and resources from the teaching team, clients, and students (Boomer et al., 2007). Given the complexity of delivering these courses, the question arises: is this effort worth it? Our research aims to answer this question by (1) developing a taxonomy of project-based experiential instruction, (2) exploring the benefits and challenges of live-project courses, and (3) discussing the costs and benefits of live-project courses. Our principal focus is live-project courses.

We present findings from structured interviews of faculty and surveys of former students involved with live-project courses in statistics, data science, and analytics curricula at the undergraduate and graduate levels. By analyzing the required effort and perceived benefits, we provide insight into the trade-offs and considerations involved in implementing live-project courses.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses our methodology and pedagogical context for conducting structured faculty interviews and student surveys. Section 3 summarizes the faculty interviews to establish a taxonomy of experiential learning courses, detailing the course designs, project portfolios, and integration within their curricula. Section 4 provides further insights from the faculty interviews and alumni surveys, giving stakeholder perspectives on live-project classes in the data sciences. Section 5 gives a faculty perspective on the effort required from the teaching team to run the courses. Section 6 focuses on the benefits of live-project courses based on the results of surveys of former students of courses at two universities (University of Miami and UC Louvain) and faculty interviews. Section 7 summarizes our observations and provides our recommendations.

2. Methodology and Pedagogical Context

We conducted structured interviews with faculty involved in teaching and supervising experiential learning courses in statistics, data science, and analytics. Subsequently, we conducted surveys of live-project course alumni from two institutions to obtain feedback about the learning experience and the career impact of these courses. Because we used a convenience sampling approach, our results may only generalize to public and private universities in various nations in North America, Western Europe, and the Middle East.

2.1 Faculty Interviews

The interview portion of our investigation was structured to cover course design, project type and elicitation, faculty profile, and skill requirements. A convenience sample was identified through the authors' network of colleagues, referrals from other faculty members, or direct outreach to programs advertising experiential learning courses. The selection was broad with respect to the type of institution, course, and location. Although the original emphasis was on live projects, versions featuring non-live case studies were also included.

Of the 32 faculty we contacted, 21 participated. Of those who did not, five referred us to other colleagues, three indicated they do not teach experiential courses, and three did not answer. Of the 21 interviewed participants, 18 were faculty members at public and three at private institutions. Nineteen held the title of Associate Professor or Professor. One had the title of Executive Director and one Senior Lecturer. The affiliations of the participating faculty include universities in the U.S. (12), Germany (4), Belgium (2), Great Britain (1), and Israel (2). Of those interviewed, six taught courses at the undergraduate and the remainder at the graduate level. Class sizes ranged from 12 to over 150, with the majority having an enrollment below 40.

Each potential participant was invited via a solicitation email to participate in a video interview with one of the authors. During the video call, the participant was acquainted with the topic and purpose of the study and asked a consistent series of scripted questions. The solicitation email and scripted questions are available in Jones-Farmer et al. (2024). The questions addressed what kind(s) of experiential learning, if any, their institution offered and in what data science-related departments and curricula. Additional questions addressed methods for obtaining projects or data, the type of faculty teaching the courses, and additional staff (e.g., Teaching Assistants) required. Finally, we asked about perceived benefits to the students, faculty, clients, and institution and the time and resources needed.

The interviewers transcribed the responses to the questions in a structured spreadsheet. To provide consistent formatting for the responses, each interviewer coded the responses for all participants. The author team discussed the codings to reach a consensus on categorizing the responses. Consensus results were tabulated into a spreadsheet and summarized.

The interviews concerned classes labeled as capstone courses, analytics practica, statistics consulting classes, and case study courses. Most but not all experiential courses were required as part of the students’ curriculum or degree. In one case, project-based learning was extracurricular. Nearly all faculty members indicated that the goal of the course was to better prepare students for the workforce, including soft skills such as problem framing, project management, teamwork, and communication. One respondent indicated that the course was built to help students pass their comprehensive exams.

2.2 Alumni Surveys

The sampling frame for the alumni survey included all participants of the statistical consulting graduate course at Université Catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), a public university in Belgium, and all participants of the business analytics practicum courses at Miami University, a public university in Ohio, U.S.A.

Former students of each course were emailed a link to an online survey, and reminders were sent every two days for one week. The alumni contacted from UCLouvain participated in the course between 1996 and 2021. Of the roughly 200 alumni, recent email addresses were available for 143. The alumni contacted from Miami University participated in the course between 2015 and 2021. Here, recent email addresses for 102 alumni were available. The surveys were conducted in September and October 2022. The response rates were 66% (94/143) for UCLouvain and 46% (47/102) for Miami University. Forty percent of the respondents took the class within three years of the survey date, and twenty-two percent took the course more than ten years earlier. The complete set of survey questions is given in Jones-Farmer et al. (2024). The summarized and anonymized survey results and data are provided as supplementary material to this article.

The two-semester statistical consulting course at UCLouvain has been offered at the graduate level since 1996. The course is recommended but not required for statistics, biostatistics, and data science graduate students. The course is also accessible to students from other disciplines with sufficient statistical backgrounds and attracts between five and twenty students annually. The course includes four parts: an introduction to statistical consulting, two live projects, and a section on professional practices like project planning and ethical considerations. Each live project lasts eight weeks and is divided into four stages: introduction, initial exploration, main analysis, and presentation/reporting. Clients, external or university researchers, are recruited by the instructor. Projects are large, divided into sub-projects, and allocated to individual students or small teams. Clients are present at the kick-off and the presentation stages and are available for questions during the project cycle. Clients are not required to pay but sometimes invite the class to lunch after completing the project.

The business analytics practicum course at Miami University has been offered at the undergraduate level since 2015. A graduate-level course was added to support Miami University's Master of Science in Business Analytics (MSBA) in 2020. Undergraduate and graduate students are not co-mingled in the business analytics practicum at Miami University.

Students in the semester-long undergraduate business analytics practicum courses are business analytics majors in the final semester of their program. The class size is typically 20 students, and it is an elective in the program. Before taking the course, students complete semester-long methods courses, including introductory statistics (2 courses), python programming, regression analysis, database, data mining, big data management, and electives such as forecasting and design of experiments. Students work in teams of 3-5 to complete a live project with a client. Two client formats have been used in this class. In some semesters, multiple teams have worked on a single project, each providing a solution to the clients. In other semesters, each team received a unique project with a unique client. The format was determined based on the availability of clients to support the projects. External clients participate voluntarily and do not compensate the university for the work.

Students in Miami University's MSBA are required to take the two-semester-long graduate business analytics practicum. The class size is typically 20 students. Before the business analytics practicum, students complete semester-long graduate-level courses in data mining, big data management, data warehousing and business intelligence. Before taking the business analytics practicum, students also complete a semester-long course, “Communicating with Data,” in which they learn to deliver business value through end-to-end analytics solutions, from problem framing to solution deployment. “Communicating with Data” was designed to prepare students for the graduate-level business analytics practicum and emphasizes understanding client needs, developing scientifically reproducible solutions, and clearly articulating the results to the client audience. In the graduate-level business analytics practicum, students work in teams of 4-5 and complete one project that spans two semesters. Each team works with a different external client. External clients voluntarily participate, and some provide a financial gift to Miami University to support the MSBA program.

3. Three Categories of Experiential Courses and Activities

Martonosi and Williams (2016) identified four main types of statistical capstone courses, including courses with a single stand-alone project, statistical consultancy courses, methods courses that include a project, and an instructional capstone course in which the primary instructional elements of the course center on statistical practice and small projects with no client. Paloian et al. (2022) noted that culminating experiences for students in statistics can be fulfilled in capstone courses, internships, or research projects. Our original analysis of faculty interviews revealed five categories of experiential learning opportunities, three of which are the same as Martinosi and Williams’ (2016) classification: live-project classes, case study-based courses, and projects within methodology courses.

“Live” project classes, where students work in real-time on open questions with live client interaction under the guidance of experienced instructors.

Case study-based courses, where students analyze real or realistic problems as their primary course of study, but the projects do not actively involve clients.

Projects within methodology courses, where students work on real or realistic datasets integrating multiple concepts from a specific methodology.

In our taxonomy, we combined courses with a single live project and consultancy-based courses where students solve a series of smaller projects since both include significant client interaction. Like Paloian et al. (2022), our faculty respondents also mentioned internships. Some also taught narrowly targeted short courses that considered only one aspect of the analytics life cycle, such as communicating results or project framing. Since internships and narrowly targeted courses were outside of the scope of a regular academic term class, we eliminated them from the scope of this article.

In the following subsections, we discuss the main aspects of each course type. Our discussion draws from our interviews with faculty and our experiences teaching such courses. It is important to note that the three categories of experiential learning discussed below are not mutually exclusive. Some or all these approaches often appear within different classes in a student’s course of study.

3.1 Classes with Live Projects

Courses with live projects involve a close link to a client organization and its challenges. Focus is on a problem, its importance to the client, and devising an appropriate methodology to solve it. Experienced faculty provide guidance and support to ensure students achieve the course objectives and clients gain value from the projects.

The institutions at which live-project classes are taught range from small to large, private to public, and across all data-related disciplines. In some live-project classes, each student works individually or as part of a team on live projects that span one or multiple semesters. In others, there are multiple smaller projects undertaken in sequence.

For example, the business analytics practicum at Miami University is a live-project course taught at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Students engage in a single semester-long (undergraduate) or two-semester-long (graduate) project with an external client. Students interact regularly (weekly or bi-weekly) with the clients. Similarly, Virginia Tech offers a senior capstone course for undergraduate majors in Computational Modeling and Data Analytics. Students engage with external clients, with each team working on its own distinct semester-long project. At UCLouvain (Belgium), the course stretches over two semesters, and two successive live projects with mostly external clients allow the students to grow in maturity. At the LMU University of Munich, teams of two students work independently over two semesters on one external project. The two courses (Laboratory in Statistical Consulting and Statistical Laboratory) at Hebrew and Tel Aviv Universities in Israel are similar in design to the one in Munich.

Multiple successive live projects within one term are difficult to organize with external clients. An example is the STAT998 course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in which three live projects are treated in succession during one term. The clients are usually internal and related to the university consulting services. However, the complexity of multiple successive live projects in a single term is considerable. Therefore, this design is more common with non-live but still realistic projects. This is discussed in the following section.

Regardless of their design, live-project courses offer a consultant-like perspective and provide a systematic approach to managing the project life cycle. This structured learning environment offers opportunities to develop a wide array of practical skills, including peer-to-peer collaboration, written and oral reporting, and presentation of results.

3.2 Case Study Courses

In case study courses, projects are not live and often originate from past consulting situations, publications in the literature, or publicly available datasets. The entire course is often dedicated to solving a series of case studies. The focus is on finding an appropriate methodology as though it were a live project but without the added pressure of a real client and a need for a real solution. This can provide opportunities for students to develop essential data pre-processing, analytics, interpretation, presentation, and reporting skills.

Some of the faculty we interviewed taught case study courses instead of a capstone course and noted that they used past projects and data as case studies, often reusing the same case for multiple semesters. Some indicated using data and scenarios on competition sites like Kaggle (www.kaggle.com) or data repositories like the UCI Repository (www.archive.ics.uci.edu). Several instructors indicated that live-project courses would provide students with a more realistic educational opportunity, but they did not have the time or resources to locate projects.

Examples include the case studies courses offered at the undergraduate and graduate levels at the University of Dortmund in Germany. At the undergraduate level, the students work in teams on five small topic-oriented case studies. Each case study centers on one statistical methodology and adds conceptualization and communication stages at the beginning and the end. At the graduate level, the students work in small teams on two successive case studies. These case studies are not topic-oriented and larger in scope than the ones at the undergraduate level. A similar format is also used at Hasselt University and KULeuven in Belgium. The case studies often come from university research.

Although they do not provide direct interaction with clients, case studies can serve as good preparation for jobs or graduate studies. Since reference methodologies and solutions usually exist, instructors can focus on evaluating the correctness of students’ work or directing them toward rectifying important methodological deficiencies in the original.

3.3 Projects within Methodology Courses

Some of the faculty we interviewed indicated that their methodology courses also include a project component. Projects within methodology courses are common across traditional statistics curricula and in data science and analytics programs. They occur both at undergraduate and graduate levels. From our experience and talking with our interview participants, we found that projects within methodology courses typically involve completing a substantive project as part of a course focused on another topic, such as time series, regression, or data mining. For example, a time series course could include an end-of-semester project where students analyze a collection of economic or financial indicators. The data may be provided as a case study or gathered by the students from specified sources. This approach allows students to apply what they have learned in a realistic but not live setting.

Well-organized projects embedded in topic-based courses can be very beneficial for students. For example, incorporating publicly available data sets such as Kaggle examples into a data mining course can help students develop their data modeling skills. Class projects can also help students develop presentation and writing skills. While beneficial for synthesizing the topics covered in the course, class projects are less realistic than live projects or case studies and often do not involve the entire project life cycle. Moreover, when the same project is re-used for multiple student teams or over more than one semester, it can be difficult to maintain originality and freshness of results.

4. Stakeholder Perspectives

Experiential learning in statistics, data science, and analytics has four principal stakeholder groups: instructors, students, clients, and administrators. From the instructor’s perspective, designing, delivering, and evaluating live-project classes involves practical considerations such as project/problem/dataset selection, curriculum integration, and assessment methods. Learning approaches and motivation are crucial from the student's perspective, as they must balance this experience with other competing interests and activities. Clients are primarily interested in the potential for talent discovery and the value that can be realized from the students’ solutions. Administrators, meanwhile, are focused on the overall course or activity portfolio, staffing requirements, budgets, and the impact on the institution's reputation. This section combines our experience with our faculty interviews and student surveys to give insights into these perspectives.

4.1 The Instructor’s Perspective

This perspective is derived from the authors' insights and our structured faculty interviews. Faculty involved in experiential learning activities have varying levels of autonomy in designing them. They may be free to create the activity from scratch with a set budget or be given a pre-existing course to deliver. When allowed to design the course, they must consider four main factors: whether to make it a live or non-live experience, whether to focus on one project or many, whether to have students participate as individuals or in teams and how evaluations are to be conducted.

4.1.a Live versus Non-live Projects

Live projects provide a significant advantage in experiential value: they involve real-world demands on both technical and non-technical fronts and pique students' attention and engagement. However, for a project to be considered “live,” the outcome must be a priori unknown, requiring instructors to guide students while allowing them to develop their own solutions.

Leading live projects requires the instructor to have a broad knowledge and experience base and the ability to learn quickly and to improvise. This often requires experience or seniority that may be lacking in some departments. If this expertise is lacking, one solution is to undertake instruction as a teaching team. In general, faculty who have previously participated in similar activities and are passionate about them, have consulted extensively, or had work experience before returning for graduate study are most likely to possess the necessary skills. In addition, in research-focused institutions, participation may challenge the research and publication requirements for young, tenure-track faculty.

Acquiring and preparing for live projects can also be time-consuming. The projects may require high-level approvals from the sponsoring organization or involve intellectual property or data privacy constraints. On the other hand, live projects with real-world clients sometimes lead to collaborations on a research or consultancy level for faculty, often to student employment opportunities, and nearly always to the reputational enhancement of the academic institution.

Non-live projects have the advantage of being pre-prepared and having an existing solution. They present students with the challenge of working with real data and questions, allowing them to experience the flow of solving a real problem. Non-live projects also have vast time-saving advantages in acquisition, preparation, coaching, and evaluation. When a master solution already exists, evaluation is greatly simplified, and solution proposals can be benchmarked against it. However, non-live projects lack the feeling of contributing something new to the client and may not offer employment, research, consultancy, or reputational opportunities.

4.1.b One versus Multiple Projects

In our experience, there are three main approaches to using one versus multiple projects in an experiential learning class. These include:

running multiple distinct projects in parallel;

using a single project replicated among multiple teams; and,

implementing a large and complex project broken into distinct and complementary non-overlapping parts assigned to multiple teams.

Each approach has its own set of benefits and limitations, and it is essential to consider the goals of the course and the level of expertise of the students and instructors when deciding which approach to use.

Managing distinct projects for many teams in parallel can be a demanding task for the teacher or teaching team, especially in live client situations. Among other things, this requires:

recruiting suitable projects;

aligning project scope with the skillset of students and duration of the class;

managing non-disclosure and intellectual property agreements;

ensuring availability and transfer of data;

coordinating initial and ongoing meetings between clients and student teams; and,

delivering the project work to the clients.

Courses at Virginia Tech, Miami University (graduate-level), Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Munich are examples where each student team is assigned a unique client project. The graduate course at Miami University is small (up to 20 students, which can be divided into teams of four or five). The capstone course at Virginia Tech has about 165 students per year, taught during the fall and spring semesters. About 40-50 live projects must be acquired and managed per year. Considerable effort is needed to establish and maintain relationships with external clients. For large classes, the logistical and administrative effort can be overwhelming and requires dedicated support from the institution. Here, one encounters a diseconomy of scale: the fortieth project is much harder to sign on than the tenth, which in turn was much harder than the first.

An alternative is to have students identify their own projects. This approach is successful with currently employed “working professionals” but may be practical only in such instances. In the authors' experience, traditional students tend to make poor project identification choices. Moreover, instructors must establish a project approval process, which can be time-consuming and face the prospect of rejecting some projects, with the subsequent necessity of finding a replacement. When individual evaluation is unimportant and the objective is to allow students to gain experience, a framework for voluntary team-based work on external projects may be interesting. This is attempted by the Data Mine initiative at Purdue University, where experienced students mentor teams who find projects either by their initiative or through the university network.

Running multiple distinct projects has advantages for students when they can exchange experiences. Students witness their peers solving very different challenges, building awareness, and developing the skills and confidence to approach new problems.

An alternative approach to managing multiple projects in parallel is to have multiple student teams work on a single project. This approach is simpler for the instructor in live-project courses, as it often involves common challenges across teams regarding client management, data, and solution methodology. One of the authors finds this approach particularly beneficial when working with undergraduate students who may lack experience. The instructor can provide more in-depth coaching when dealing with only one project per class, and the upfront work of project acquisition is greatly reduced. This approach is taken for undergraduate students at Miami University and the first two projects at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

However, there are downsides for both the client and the student. The client will receive many presentations of multiple, sometimes conflicting, solutions. Different conclusions drawn from the same data can call into question the integrity of the teams’ results. For students, the overlap and sharing of information among teams can lead to a lack of variety in learning experiences and may sacrifice the experiential aspect of the class.

A third approach to managing experiential learning projects is to assign a single, large, and complex project that can be broken into smaller, manageable parts. Each team can then work on a specific aspect of the project, combining the results to form a final solution. Students can see an overall theme and how their work contributes to the project, and how a large project is decomposed into smaller, manageable parts. This approach has been used successfully for the statistical consulting course at UCLouvain (Belgium).

4.1.c Individuals versus Teams

Based on our experience in classes with fewer than 15 students, one alternative is for students to work individually on separate projects or a single project either separately or collaboratively. In the last of these, each participant receives a different mission within the project. Having students work individually assures that all will experience the full gamut of project management tasks and simplifies the instructors’ tasks of evaluating their performance.

However, the individual approach quickly becomes intractable when there are many participants. Faculty can become overwhelmed in individually mentoring a large number of students and grading their work. Another shortcoming of the individual approach is that it does not foster the development of collaborative skills the students will need once they begin their careers. In our work and our observation from the faculty interviews, nearly all courses in experiential learning have participants working in teams.

Fair assessment and grading are difficult in a team setting where the performance of individuals may be strongly affected by other team members. In an experimental study by Hoffman and Rogelberg (2001), students showed higher intention to enroll in a course with group work and more positive perceptions of the grading when both individual and group work were evaluated. Labeouf et al. (2016) encouraged faculty to monitor group projects and mentor students closely throughout the process. Ideally, the students’ work would be closely followed to allow individual assessments and grades. To achieve this, the team’s output, such as a presentation and a report, must be accompanied by an individual assessment. This may be a written or oral presentation by each participant during a project defense or a requirement to submit individual assignments. One or a series of structured 360-degree evaluations among the team participants can also help. Such a mutual review avoids misbehavior of some team members (by dropping out, relying on the work of others, etc.).

4.2 The Student’s Perspective

The students’ perspective we provide is based on a summary of the open responses to the survey question “Looking back when you took the course, what did you find special or unique about it?” as well as a summary of end-of-course feedback and reflections provided by past students. The survey participants were all students of live-project classes.

In their open response to our survey question, the most common uniqueness of their experiential course mentioned by students was real-world experience, including working with real clients and actual companies. Many respondents noted the value of client interaction, including direct client contact and presenting to clients. One respondent summarized this well: “This course was in a client-focused approach. As a student, we had to use the learned skills (from other courses) to try to create some added value for the client. We were also encouraged to present our work and to prioritize the client's goals, and we also learned how to write an efficient report.” Another respondent wrote that the class gave them “exposure to real-world problems and the opportunity to engage creativity and critical thinking skills.” One noted, “It was beneficial working with real data and problem-solving a solution a business was actually dealing with. One of the only experiences in college that felt applicable in my later career. Was also an experience I drew back in when interviewing for jobs right out of college.”

Concerning the career impact of the course, one former student noted it provided examples of “real-life projects that I could use as examples of professional experience in job interviews.” Another noted, “I use many of the techniques I learned in the practicum in my current job.” Still another said this: “It is the only course in the master's course that really prepares for a career outside the academic world.”

The skills mentioned in the open responses as unique aspects of the course also underscored the important lessons learned through direct client communication and presenting to clients. One former student summarizes this well: “It was neat to directly work with business partners to understand the context of the problem and analyze it from beginning to end. I think the most valuable skill I developed was how to communicate and present my data-related findings back to the company.”

In end-of-course feedback, students often report that live-project courses are challenging and time-consuming. However, they often express satisfaction with the confidence they gained, the diverse approaches they learned to take when exploring the context of a project, the experience of working with clients, and the practical skills taught by the instructor. One of the key takeaways from such courses is learning to set realistic goals and manage time effectively, which can be an essential part of personal and professional development. Students participating in live-project courses also emphasize the freedom they are given in pursuing their own approach while being coached and guided when they get lost.

Although our survey focused on former students who participated in live-project courses, the authors also have significant experience leading case study and methodology courses with embedded real problems. In these courses, the realism of working with a client is removed, as is (in most cases) engagement with employers and the opportunity to provide value in one’s solution. These are serious drawbacks; however, the value of working with real data remains. Several faculty we interviewed noted that students may lack the “feet-to-the-fire” motivation to perform their best without the client. Motivation can be increased with game-style competition, such as a performance leaderboard or a promise of enhanced visibility for the best performers. For example, in one data mining course at Miami University, students complete their non-live final project while competing in the so-called “Data Mining World Championships” for notoriety on social media.

It is important to note that experiential learning courses can be either a mandatory or an elective part of a student’s program of study. When participation is mandatory, students may not embrace the class unless they see the merit. Motivation may come naturally when the course involves live projects, engagement with potential employers, and interesting problems where the students feel they can contribute positively.

4.3 Faculty Insight into Clients and Administrators

We did not directly interview Clients or Administrators. However, many of the faculty we interviewed gave us their insights into the perspective of clients who work with students in experiential classes and administrators who manage the resources for these classes. The discussion below combines the authors’ experience gained through work with clients and administrators in managing live-project courses for over two decades, along with the perspectives shared by our faculty interview participants.

4.3.a Clients

Clients participate in experiential learning projects for two main reasons: to obtain solutions to their problems or to identify talented students for future employment. Success in the first of these is directly tied to the client's level of support and involvement. Clients who offer significant resources and mentorship tend to see the greatest benefits as they guide solutions to ensure relevance to their organizational needs.

Such projects also offer a cost-effective way for clients to identify candidates for future employment. Clients can get to know the students, assess their skills and fit for the organization, and engage in a mentorship relationship. The deep involvement with the students helps employers become more familiar with the quality of the university’s curriculum and students. This helps them make informed hiring decisions based on the students' abilities, strengths, and areas for improvement. It also helps draw students to them, as their presence and visibility in student presentations put their brand before the entire class and sometimes beyond. Furthermore, these relationships can help promote the educational institution's reputation, resulting in better student placement, support of faculty research, and philanthropic initiatives.

4.3.b Administrators

Faculty, students, and administrators generally agree that live-project courses create unique student opportunities; however, many administrators overlook the resources and faculty training required. The main issues that administrators should consider include:

positioning the course appropriately within the curriculum;

recruiting qualified teachers;

recruiting project sponsors;

scaling the course offering for larger audiences;

providing a sustainable process for maintaining all aspects of the course over time.

Live-project courses are commonly offered at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. In high-enrollment programs, finding and managing enough projects for a large student body can be very difficult; at the very least, it requires adequate staffing resources. In some cases, therefore, the course is placed as an elective in the curriculum, with students being filtered by GPA and/or permission of the instructor. Unfortunately, these gates on enrollment mean that not all students have equal access to this important growth opportunity.

The modality of an experiential course (live project, case study, projects within classes) will dictate the required faculty skillset and accompanying staffing level. For live-project courses, faculty should have good communication skills, a wide range of methodological interests, up-to-date technical skills, and a strong dedication to mentoring students. Most faculty we interviewed indicated that recruiting teachers for experiential courses is challenging. One interviewee noted that to teach an experiential learning class with a live client, you must be comfortable walking into class daily without knowing what technical or personnel challenges you will face. Few faculty members who have spent their careers in academia have broad industry knowledge and comfort with uncertainty in the classroom. One way to staff live-project courses is to hire late-career industry professionals with a breadth of technical expertise, the ability to manage uncertainty and client relationships, and experience in mentoring. Notably, one of our authors falls into this profile. Additionally, another of our universities recently staffed their course with a well-known late-career professional.

In most cases, the faculty assigned to the class are either fully or partially responsible for recruiting clients to sponsor projects. Therefore, the faculty member should have a personal network of contacts or access to institutional partners and alumni. In our experience, recruiting project sponsors and defining and scoping projects that fit the students’ abilities is difficult and time-consuming. For smaller programs, finding a few (say, up to five) projects per semester is reasonable for one person to manage but still requires substantial client interaction in the 1-2 semesters before the course. This time must be recognized and planned for in establishing workloads for faculty. Live-client project-based courses are unlikely to scale without substantial administrative and organizational support.

Live-project courses require sufficient funding, which they may generate internally. Many programs request or even require payment by sponsors as a condition of participation. Requests that we are aware of range from $5,000-$12,000 per semester per project. Some of this support may be allocated to faculty who work between semesters to recruit and scope projects. Administrators must consider this additional workload and compensate faculty fairly for their time. In our experience, the required time and effort are, at best, linear in the number of participants. In fact, due to the difficulty of identifying sponsors and projects, we believe that live courses experience a diseconomy of scale.

Observed configurations for experiential courses or activities include a dedicated single teacher or a static or rotating teaching team. The single-teacher design can pose a challenge upon retirement or sabbatical if the same faculty member has been teaching the course for many semesters. The rotating team model, often seen in institutions with internal consulting groups, ensures instructional sustainability. However, a stable faculty teaching team is necessary for large student cohort sizes. This also fosters collaboration in the recruitment of projects and in client relationship management.

Other factors for administrators to consider in offering a live experiential learning course include nondisclosure and intellectual property (IP) management. Companies and universities often require nondisclosure agreements for joint work. IP management protects novel results, and value extraction involves reviewing projects to determine elements worthy of publication, licensing, or development.

4 Effort and Cost of Live Projects in Courses

Engaging students with live client projects requires effort and resources from the faculty and participants. To ensure the program’s quality, it is essential to strike a balance between the contributions of each party. This section outlines the key factors affecting the cost and effort for live-project courses discussed above. This discussion is based on our experience and the perspectives we gained from our structured faculty interviews. We also briefly compare the efforts required to deliver live-project courses versus case studies or projects within methods courses.

5.1 General Considerations

Courses with live projects typically consist of lectures prepared by instructors and group work by teams of students. The acquisition of projects is made through the teachers’ network of contacts, collaboration with colleagues who have external or internal consulting contacts, or through a call for proposals. The projects must fit the scope of the course and be suitable in terms of size, data availability, and deadlines relevant to the client.

Project preparation includes tasks such as rationalizing the project scope and timeline, ensuring the suitability of data, crafting a project statement, resolving intellectual property and data privacy issues, and assuring the availability of a mentor from the client organization. Acquisition and preparation of a single project requires many hours persistently spread across several months before the start of the semester in which the class runs.

Once the front-end work on the project is complete, faculty must ensure students apply their best effort to deliver something valuable to the client. This involves plenary meetings with all course participants, meetings between the teacher(s), assistant(s), and students, and additional contact with the client. When the students begin the actual project work, faculty often meet with student teams both in and outside the classroom. This keeps the teams working towards a solution, helps solve conflicts, and ensures satisfactory client interactions.

Throughout the course, evaluation of student projects typically consists of three parts: assessing final deliverables, evaluating the quality of work, and grading written and oral project reports. The effort required varies greatly depending on the number and depth of assignments, the organization of the class, and the nature of individual projects. We estimate that grading student projects requires four to eight hours per student team.

5.2 Examples from Our Own Experience

Small class with team-based projects: The graduate-level business analytics practicum course at Miami University in Ohio is an example of a course that involves projects done in teams of 4-5 with both team and individual deliverables at the evaluation stage. A single class section usually has four projects. The projects' elicitation, management, and follow-up take approximately 60 hours per project outside of regular class time and preparation. Much of this work is unpaid overload during the two semesters before the practicum course. In a class with four projects, this is 240 hours, equivalent to six weeks of additional work at 40 hours per week. During the semester, faculty members may meet with each student team outside of class between one-half to one hour per week. In a class with four projects and a 15-week semester, this adds 30-60 hours outside of the classroom.

Statistical consulting class: UCLouvain offers a graduate-level statistical consulting course. In this course, two master projects are run in succession, with the twelve participants split into three sub-projects. The total time budget is 2 x 120 hours for the elicitation, management, and follow-up stage plus 2 x 24 hours for evaluating reports, equaling 288 hours.

Large capstone course. A large capstone class is not feasible without additional staff to manage project elicitation and management. Because of this, the effort to run the class is usually divided among faculty and teaching assistants who work in a team to deliver the class. For example, in an undergraduate capstone course in the senior year at Virginia Tech, 40 to 50 projects are completed by around 165 students per academic year. This class requires the efforts of approximately 1.5 full-time equivalent calendar year faculty plus four half-time academic-year graduate teaching assistants.

5.3 Cost Reductions of Case Studies and Non-live Projects

Based on our own experiences and the perspectives we gained from our faculty interviews, case study courses, and projects within a methods course require considerably less effort and time than live-project courses. Time-consuming costs and efforts specific to live projects are acquiring projects, project preparation, and moderating student/client meetings. These aspects may be absent entirely for case study courses and projects within a methods course.

When using a published case study, competition data set, or even data from one’s past consulting projects, the project acquisition, preparation, and scoping may have already been completed so that it can be reused in multiple semesters. Initial preparation of a case study, including formulating the appropriate research questions and compiling relevant data, might require 1 or 2 days per project. There are generally no client meetings in either case-study or projects-within-methods courses.

Mentoring students can also be simplified since the instructor is familiar with a pre-determined solution and is not solving the case or project live along with the students. Delivering a course containing a large but not live project requires a similar effort to case study courses; however, the project is generally focused on a methodology already presented to students. Faculty must coach students in case studies and projects within methodology courses but without interaction with clients. This can still require a significant amount of time, but the instructor can better control the direction of the students’ work. Finally, evaluating student solutions and presentations requires substantial effort, regardless of the class modality. This effort is proportional to the number of students. However, the evaluation process is often simplified in courses without live projects since the students generally provide solutions to the same case or project.

6 Benefits of Live Projects

This section discusses the observed and perceived benefits of live-project courses to stakeholders. The benefits to students we discuss are based on the student surveys. Since our sampling frame is limited to former students who participated in live-project classes, our discussion of benefits to students is limited to live-project classes. In keeping with this focus, we also frame our discussion of the benefits to the other stakeholders concerning courses with live projects.

6.1 Benefits to Students

We focus on responses to four items obtained from the survey of former students of live-project classes at UCLouvain and Miami University: (1) to what extent the respondents would recommend the course to peers; (2) how much impact the course had on their career; (3) how much they learned about ten subject areas; and (4) what they found special or unique about the course.

Overall, students who participated in the survey shared a very positive view of their experiential learning course. Ninety-seven percent of the students surveyed reported they were either likely or very likely to recommend the experiential course they took to a friend. This positive response is expected because students felt the course delivered value. Moreover, more than 90% of the respondents stated that the course had helped them in their careers. Half of the respondents at Miami University indicated that the course had helped them greatly in their careers.

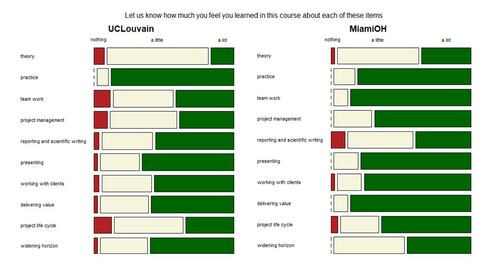

Former students were also asked how much they learned about ten subject areas. Figure 1 shows the results for the UCLouvain and Miami University.

Among all respondents, many noted “a lot” of learning about practice (85%), presenting (70%), project management (48%), delivering value (68%), and working with clients (63%). Unsurprisingly, only 22% of the combined respondents indicated they learned “a lot” about theory, but almost all stated that they learned at least a little. This corresponds to an observation made during post-project discussions at UCLouvain. Participants often state that the project helped them to get a much better feeling for theoretical concepts and their practical importance. Teamwork has been stressed in the course at Miami University but not at UCLouvain, where the work was primarily individual; thus, the learning about teamwork and project management is higher at Miami University.

Benefits to students vary with course design. The excitement and motivation of working with a real, unsolved problem and a real client can only be achieved in a fully live format. The case study format still preserves the opportunity to combine tools and to follow a project from an early stage to a statistical solution. In both live and non-live formats, students may be able to develop their teamwork, presentation, and writing skills. Moreover, the topics may expose them to subjects they are not yet familiar with, thereby widening their horizon. Projects embedded in methodology courses are usually smaller and necessarily limited in the choice of methodology but may preserve aspects of teamwork, presentation, and writing.

6.2 Benefits to Instructors

The large variety of topics of the projects and associated methodologies require continuous learning and lead to a broader horizon and understanding of many key questions in the data professions and society in general. As faculty members teaching this course, the breadth of understanding and knowledge of real-world data problems faced in industry has helped us grow and strengthen our skills. This breadth of knowledge carries over into our more focused methodological courses, allowing us to bring real-life examples and experience into these classrooms.

Occasionally, research ideas and partnerships emerge from live-project courses. In our faculty interviews, a few faculty members noted that consulting engagement or research opportunities had emerged from relationships built with live-project clients. One of the authors of this paper has collaborated with a project sponsor on research and had another client support a federal research grant application. At the university of another author, several course projects turned into long-term collaborations between the clients and the university consulting service.

6.3 Benefits to Clients

No formal survey has yet been conducted among former clients, and we can only report on informal feedback at this time. Benefits to the clients vary greatly depending on their reason for supporting the project, their need for a solution, the quality of the students, and the quality of the data associated with the project. Each of the authors of this paper knows of several impactful solutions that have been implemented based on students’ work. For example, the current method for evaluating wines and tasters at the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles, a major wine competition, was inspired by student work in 2005. A recent project on the effect of e-mobility and heat pumps on residential electrical grids helped the client increase their expertise. It led to a succession of follow-up projects with the university consulting service. A major global shipping company has a new way to predict absenteeism in their warehouse operations, and a global financial institution has implemented a model to understand how to best contact customers.

In addition to gaining insights from the students’ work, many clients are interested in using live-project sponsorship to test-drive future employees. Client project sponsors have hired many of our former students. The course-client collaboration develops relationships between the client sponsor and student, similar to student internships. Having worked with the client and their data can ensure smooth student employment transitions and cost savings in recruiting.

6.4 Benefits to Administrators

Live-project courses can deepen and strengthen the relationships between the academic institution and client organizations. This can lead to financial support for the university, deepening research partnerships, and student placements within companies. For example, at one of our author’s institutions, several recent client sponsors wrote strong letters of endorsement for a state funding proposal to add a new graduate degree. At another institution, two recent client sponsors wrote letters of support for nationally funded research initiatives.

Another important benefit is that live-project courses make academics more attractive for prospective students. Programs that include experiential learning courses appear more up-to-date and professional. In our work, we have also found that students of live-project courses often become future clients. This strengthens the alumni network as former students “give back” to the university. A strong alumni network provides contacts to companies, research groups, and public institutions, generates opportunities for collaboration and research, and provides funding and sponsorship.

7 Conclusions and Recommendations

We have identified three types of courses in statistics, data science, and analytics curricula based on the level of interaction with real-life projects. These include courses with live projects, case studies, and courses that offer exposure to real data within a topical context. Our colleagues interviewed for this article agree that live courses provide students the greatest value among courses based on real projects and do so across the dimensions that we have articulated in the preceding sections. Moreover, some of our colleagues interviewed for this article feel that the reputation of their university has been favorably impacted by offering practicum programs. In some cases, class projects have led to research collaborations and funding. In addition, universities were able to attract corporate mentors who had participated as sponsors to take on late-career clinical positions in academia as directors of practicum classes. However, live-project courses are also the costliest to run regarding the effort to solicit and identify the projects and the required level of faculty expertise. Live-project courses are difficult to scale, with costs increasing dramatically as enrollment grows.

Live-project courses provide universities with staffing challenges that go beyond mere numbers. There is a temptation for administrators to assign what is perceived as a non-technical course to junior or adjunct faculty who have little or no experience outside academia. These inexperienced faculty may be ill-equipped to identify projects, guide relationships, or coach teams on realistic solution approaches. Most of the successful offerings we have encountered are headed by senior faculty or experienced business professionals with a depth of experience interacting on real applications in corporations or government. However, the fraction of even senior faculty who are thus qualified is limited. Attracting experienced senior professionals to academia is a challenge, even for departments that see value in the attempt. Two of our three programs posted positions of this type within the last 18 months of this writing and found it difficult even to generate qualified applicants.

Our investigation shows that many departments teaching in data science disciplines have chosen not to offer live-project courses. Our colleagues manage their resources to provide the best educational opportunities possible via courses elsewhere on the experiential learning spectrum—from case study and classes teaching consulting methodologies to simulations of real applications projects. Although less realistic than live-project courses, they may still achieve excellent outcomes. The choice to offer a live-project course must be made considering the unique faculty qualifications, networking relationships, and funding commitment required. The return on that investment is realized in an enhanced educational experience, higher/better student placement, and potentially increased visibility and funding for the institution. However, significant and continuing operational demands must be met. We admire—and are honored to be working for—educational institutions that make this commitment, and we hope this practice will become more widespread.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor, associate editor, and three anonymous referees for their careful review and helpful suggestions that significantly improved the exposition of this work. We also thank all colleagues and former students who contributed their ideas and experiences.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available as supplemental material to this paper.

Statement of Ethics in Research and Informed Consent

The research plan was reviewed and approved by the Miami Research Ethics and Integrity Program (no. 04597e).

ujse_a_2374565_sm0745.zip

Download Zip (385.2 KB)References

- Boomer, K. B., Rogness, N. and Jersky, B. (2007). “Statistical Consulting Courses for Undergraduates: Fortune or Folly?.” Journal of Statistics Education 15(3). DOI: 10.1080/10691898.2007.11889542.

- Carver, R. H., Everson, M., Gabrosek, J., Horton, N., Lock, R., Mocko, M., Rossman, A., Rowell, G. H., Velleman, P., Witmer, J., and Wood, B. (2016), Guidelines for Assessment and Instruction in Statistics Education (GAISE) College Report, Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association. https://commons.erau.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2173&context=publication

- Hoffman, J. R., & Rogelberg, S. G. (2001). All together now? College Students' Preferred Project Group Grading Procedures. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5(1), 33. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2001-16668-003.pdf

- Hunter, William G., (1981). “The Practice of Statistics: The Real World is an Idea Whose Time Has Come.” The American Statistician 35(2): 72–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2683144.pdf

- Jones-Farmer, L. A, Christian Ritter, and Frederick W Faltin. (2024). “Survey Data From ‘Expensive but Worth It: Live Projects in Statistics, Data Science, and Analytics Courses.’” OSF. May 3, 2024. https://osf.io/3y9hb/?view_only=516f2bc229a247e1bc8e52cd98a7a60a

- Kolaczyk, E., Wright, H., and Yajima, M. (2021). “Statistics Practicum: Placing Practice at the Center of Data Science Education.” Harvard Data Science Review. Issue 3.1, Winter 2021. DOI: 10.1162/99608f92.2d65fc70.

- LaBeouf, J. P., Griffith, J. C., & Roberts, D. L. (2016). Faculty and Student Issues with Group Work: What is Problematic with College Group Assignments and Why? Journal of Education and Human Development, 5(1), 13. https://commons.erau.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1432&context=publication

- Martonosi, S. E., & Williams, T. D., (2016). A Survey of Statistical Capstone Projects. Journal of Statistics Education, 24(3): 127-135. DOI: 10.1080/10691898.2016.1257927.

- Mehrotra, V., (2013). Course Puts Students in the Analytics Game. OR/MS Today, 40(4): 18-20. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA341938712&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=10851038&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7Ebb7a1df3&aty=open-web-entry

- Paloian, S., Doehler, K., & Lahetta, A. (2022). Implementing a Senior Statistics Practicum: Lessons and Feedback from Multiple Offerings. Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 30(2): 114-126. DOI: 10.1080/26939169.2022.2044943.

- Smucker, B. J., and Bailer, J.A. (2015). “Beyond Normal: Preparing Undergraduates for the Work Force in a Statistical Consulting Capstone.” The American Statistician 69(4): 300–306. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24592131.pdf

- Song, I-Y, and Zhu, Y. (2016). “Big Data and Data Science: What Should We Teach?.” Expert Systems 33(4): 364-373. DOI: 10.1111/exsy.12130.