ABSTRACT

To restore the degraded watersheds, the government of Ethiopia has recently introduced and adopted participatory natural resources management (PNRM) in different regions of the country. This study aimed at investigating the effects of the various independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors on the perceptions and the attitudes of local people towards the PNRM introduced in the Jemma Watershed, North Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia. Semi-structured questionnaire comprised of closed- and open-ended questions was developed and administered to a total of n = 420 random households in five purposely selected Kebeles of the Jemma Watershed. Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression techniques were used to analyze and interpret the household survey data. The descriptive results revealed that majority of the respondents (92.19%) agreed that they had the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. Consequently, about 83% of the respondents had already accepted the PNRM program introduced in the study watershed. The results of the multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors had significant effects on the perceptions of the local people towards ‘the concept of PNRM’ (68% variance explained), ‘the presence of PNRM practice’ (61% variance explained), and ‘the problems with the existing PNRM system’ (72% variance explained). The study further uncovered that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors significantly affected the attitudes of the local people towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’ (63% variance explained), ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’ (75% variance explained), and ‘accepting the concept and the practice of the PNRM’ (65% variance explained). As there are still some respondents who are yet unsure to fully accept PNRM, creating public awareness on the PNRM and integrated watershed management program and practice is crucial to alleviate the problems of deforestation and land degradation, thereby enhancing the sustainable use of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed.

Public interest statement

The study examined the effects of the various independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors on the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards participatory natural resources management (PNRM) in the Jemma Watershed, Central Ethiopia. Semi-structured questionnaire was developed and administered to a total of n = 420 random households. Descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression techniques were used to analyze and interpret the household survey data. The results revealed that majority of the respondents (92.19%) agreed that they had the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources. The multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors had significant effects on the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM. As there are still some respondents who are yet unsure to fully accept PNRM, creating public awareness on the PNRM and integrated watershed management program and practice is crucial to alleviate the problems of deforestation and land degradation, thereby enhancing the sustainable use of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed.

Introduction

In the past, natural resources were exclusively managed by the Ethiopia’s government, but it was done without the full participation of the local people (Ameha et al., Citation2014; Tesfaye, Citation2011; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). Tadesse and Kotler (Citation2016) noted that local communities are often rich in indigenous knowledge and appreciation of their natural and cultural heritages. However, pressure for rapid economic development can alienate local people from their heritage and degrade the natural resources existing in their locality. For example, lack of public awareness, negative attitudes, and absence of benefit-sharing scheme from the natural resources to the local people have contributed much to the loss of natural vegetation, which ultimately led to soil erosion and subsequent land degradation in different parts of Ethiopia (Gashaw et al., Citation2018; Kelboro & Stellmacher, Citation2015; Woldie & Tadesse, Citation2020).

To reverse the negative impacts of the deriving forces, and also, to restore the degraded sites, the development actors, mainly, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) introduced the concept of participatory natural resources management (PNRM) in Ethiopia (Irwin, Citation2000; Pankhurst, Citation2001; Winberg, Citation2010). Most importantly, the Ethiopian government has recently declared to mobilize the general public to actively participate in the rehabilitation of degraded sites in various parts of the country. For example, the local people have been initiated to actively participate in natural resources conservation and integrated watershed management practices, including planting seedlings of multipurpose tree species, constructing soil and water conservation physical structures, delineating and establishing area closures in degraded sites, are a few of the engagements by the local communities in Ethiopia. Of course, the participation of the local people in natural resources management can vary from outreach that acknowledges community concerns to full delegation of natural resources protection and management to the local communities (Admassie, Citation1995; Ameha et al., Citation2014; Nelson & Wright, Citation1995).

PNRM is a strategy to achieve sustainable natural resources management by encouraging the integrated management of vegetation and land cover by the local people residing in an area (e.g. a watershed). For example, the proper implementation of PNRM is thought to contributing to improve food security and poverty reduction in Ethiopia (Kelley & Scoones, Citation2000). For example, depending on their level of income, a case study conducted by Tesfaye et al. (Citation2010) in the southeastern parts of Ethiopia revealed that the contribution of participatory forest management to the average total annual household income was estimated to be 23–53%. Thus, social interactions that are important for effective PNRM implementation include empowerment, involvement, negotiation, and collective decision-making (Kelbessa & Destoop, Citation2007). However, the successful management of natural resources through PNRM approach is reliant on the attitudes of the local people who are inherently connected with the natural resources existing in their localities and through their active involvement in natural resources management (Siraj et al., Citation2016; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017). Previous studies also noted that past benefits and values can affect the management attitudes of local people towards natural resources in a watershed (e.g. Gadd, Citation2005; Kideghesho et al., Citation2007; Walpole & Goodwin, Citation2001). According to Oskamp (Citation1977), values refer to things or phenomena or events that people consider being precious so that they are the most important and central elements in a person’s system of attitudes and beliefs.

Attitudes are positive or negative responses of people towards a certain event or phenomenon (Elias, Citation2004; Tesfaye, Citation2011). In the context of natural resources conservation and integrated watershed management, attitudes of local people are either positive or negative views to a specific conservation and management approach (e.g. PNRM program or practice) (Jotte, Citation1997; Oskamp, Citation1977). Thus, the negative or the positive attitudes of local people towards PNRM will likely affect their contribution and direct involvement in natural resources management, including forests, water, soils, and wild animals (Siraj et al., Citation2016; Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016). Behavior of people can also be influenced by their perceptions (i.e. knowledge and experience) about events or phenomena (e.g. PNRM) (Jotte, Citation1997; Oskamp, Citation1977; Woltamo, Citation1997). In return, attitudes of local communities can be affected by their behaviors (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017). So, understanding how behavior affects the attitudes of the local people is of paramount importance for the successful protection, conservation, management, and sustainable utilization of the natural resources through introducing PNRM in Ethiopia where the local people are directly dependent on those resources to meet their living essentials (Ameha et al., Citation2014; Siraj et al., Citation2016; Tesfaye et al., Citation2010; Woldie & Tadesse, Citation2019).

Previous studies showed that the perceptions and the attitudes of local people towards PNRM were significantly affected by independent variables derived from demographic (e.g. sex, age, and family size) (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019), socio-economic (e.g. level of education, occupation type, length of local residence, livestock ownership, and income level) (Ameha et al., Citation2014; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012), biophysical (e.g. distance between the boundary of the watershed and the residential area of the respondent) (Ayele, Citation2008), institutional [e.g. tree ownership, the presence of land allocated for plantation forests, the presence of traditional bylaws that local farmers used to restrict people and/or livestock from illegally destroying the tree seedlings planted and grown in their private landholdings or communal lands, land size, land tenure system and/or land ownership, availability of incentives (e.g. seeds, tree seedlings, credits, trainings, and technical supports)] (Tadesse & Tafere, Citation2017; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020), and cognitive (e.g. knowledge, beliefs, and experience) factors (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017). A conceptual framework showing the interrelationships among demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors with the perceptions and attitudes of local people towards PNRM was presented in Figure .

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the study. The figure depicts the interrelationships among demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors with the perceptions and attitudes of local people towards PNRM. Most importantly, the figure illustrates how the resulting interactions among the aforementioned factors help improve the livelihoods of the local people and thereby enhance their active participations in conservation, management, and sustainable utilization of the natural resources.

Furthermore, the perceptions and the attitudes of local communities towards PNRM are influenced by previous benefits (e.g. access to and control over resources) due to the PNRM practice (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017), knowledge of the respondents on the past PNRM system, knowledge and experience of the respondents on the PNRM implementation (Ayele, Citation2008; Roskaft et al., Citation2007), the knowledge of the respondents on the problem with the existing PNRM system (Gashu & Aminu, Citation2019), tradition of tree planting, growing, and building physical soil and water conservation structures (Ameha et al., Citation2014), and interests of the respondents towards protecting and managing the natural resources through participatory approach (Siraj et al., Citation2016; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012).

The Jemma Watershed is lying in the Upper Blue Nile Basin of North Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia, where PNRM has been instated as a mitigating measure through reducing the magnitude and direction of severe land use land cover changes and its subsequent negative impacts on the biophysical and socioeconomic resources in the watershed. This is due to the fact that the local communities are interested in seeing the introduction and implementation of PNRM in Jemma Watershed. Although some studies have been conducted by focusing on PNRM in various parts of Ethiopia (e.g. Kelbessa & Destoop, Citation2007; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tesfaye, Citation2011; Winberg, Citation2010), with especial emphasis on evaluating the perceptions and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM, no such studies have been conducted in the Jemma Watershed yet.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the effects of the various independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors on the perceptions and attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM introduced and adopted in the Jemma Watershed, North Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia. To achieve the objective of the study, the following two hypotheses were formulated and tested: (i) independent variables derived from demographic (e.g. sex, age, and family size), socio-economic (e.g. level of education, length of local residence, livestock ownership, income level, and plan to stay in the area in the future), biophysical (e.g. distance between the boundary of the watershed and the residential area of the respondents), institutional [e.g. land tenure system and/or land ownership, the presence of traditional bylaws that the local farmers used to restrict people and/or livestock from illegally destroying natural resources, availability of incentives (e.g. seeds, tree seedlings, credits, trainings, and technical supports)], and cognitive (e.g. knowledge, experience, and beliefs) factors predict the perceptions and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM; and (ii) there are differences in the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM depending on previous benefit sharing (i.e. access to and control over the natural resources), knowledge of the respondents about past natural resources management system, knowledge and experience of the respondents on the implementation of the PNRM, knowledge of the respondents on the problem with the existing PNRM system, knowledge on area closure management, tradition of local people on tree planting, growing, and constructing soil and water conservation physical structures.

Hence, the resulting insights and knowledge reported on the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM are relevant and helpful to watershed managers, land use planners, natural resources conservation managers, soil and water conservation experts, foresters, hydrologists, biodiversity conservation experts, private and public sectors while addressing the opportunities (e.g. the willingness to participate in PNRM) and the challenges (e.g. negative attitudes towards accepting the PNRM program and practice) to restore, protect, manage, and sustainably utilize the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed and beyond.

Methods

Study area

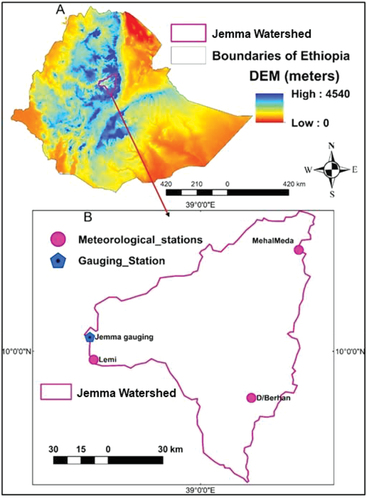

The study was conducted in the Jemma Watershed that lies between 10.6°-9.1°N and 38.7°-39.5°E in the Upper Blue Nile Basin, North Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia (Figure ). The watershed is located northeast of Addis Ababa and has a drainage area of 15,160 km2. The major landforms of the Jemma Watershed include plain areas, steep slopes, mountains, and undulated and hilly terrains which are thought to be highly vulnerable to the impacts of soil erosion. The upper and middle parts of the watershed are characterized by mountainous, highly rugged and dissected topographies with steep slopes, but the lower part is characterized by valley floors with flat to gentle slopes. Elevation in the study watershed ranges from 1,271 to 3,694 m above sea level (a.s.l.). The main land cover types in the watershed include shrubland, bare land, grazing land, woodland, and forestland (Worku et al., Citation2021; Zewde et al., Citation2024). Based on the FAO’s classification system, the nine soil types in the Jemma Watershed include Lithic Leptosols (37.44%), Eutric Vertisols (28.07%), Chromic Lixisols (8.07%), Haplic Luvisols (5.79%), Haplic Acrisols (6.827%), but Pellic Vertisols, Eutric Fluvisols, Umbric Nitisols, and Alic Nitisols shared a very small portion of the watershed (Ali et al., Citation2014; Worku et al., Citation2021; Zewde et al., Citation2024), suggesting that Leptosols and Vertisols are the main soil types that cover more than 65% of the Jemma Watershed.

According to the climatic classification by the EMA (Ethiopian Mapping Authority) (Citation1981), the Jemma Watershed is found in ‘Kur’ (Alpine) ranging from 3,000 m and above, ‘Dega’ (Temperate) ranging from 2,300 m to 3,000 m, ‘Woina Dega’ (Subtropical) ranging from 1,500 to 2,300 m, and ‘Kolla’ (Tropical) below 1500 m a.s.l (Dejene, Citation2003; Negash & Ermias, Citation1995). However, the dominant climate in the Jemma Watershed is ‘Dega’ type (Zewde et al., Citation2024). Moreover, the climate in the watershed is of a tropical highland monsoon where the seasonal rainfall distribution is controlled by northward and southward movements of the inter-tropical convergence zone (ITCZ) and moist air from the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in the summer season (i.e. June-September) (Dejene, Citation2003; Negash & Ermias, Citation1995; Zewde et al., Citation2024). The annual rainfall of the Jemma Watershed ranges from 718–1,567 mm, whereas the mean annual rainfall is about 994 mm. Rainfall in the study watershed is mono-modal and most of the rainfall occurs in the months of June to September, but from November through April is virtual dry (Ali et al., Citation2014; Kebede et al., Citation2006; Worku et al., Citation2021; Zewde et al., Citation2024).

Development of the survey instrument

The survey questionnaire was developed by considering the conceptual framework of the study illustrated in Figure . Accordingly, we prepared a semi-structured questionnaire by entertaining the various independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors (Gashu & Aminu, Citation2019; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020) that likely affect the perceptions and the attitudes of local communities towards the concept of PNRM and its practice in the Jemma Watershed.

Most socio-economic, institutional, knowledge, and experience measuring questions were measured in nominal scale and rated using 3 = yes, 2 = unsure and 1 = no. Distance between the residential area of the respondents and the boundary of the Jemma Watershed, age, family size, annual income, level of education, and length of residence in the area were measured in continuous quantitative values. Information on previous benefit sharing (i.e. access to and control over natural resources), allocation of land for woodlot plantations, knowledge on area closure management, watershed management, tree planting and growing tradition, and building physical soil and water conservation structures was measured in nominal scale and rated using 3 = yes, 2 = unsure and 1 = no. Questions dealing with the perceptions of the respondents towards ‘the concept of PNRM’, ‘implementation of PNRM’ and ‘problems with the existing PNRM system’ were also measured in nominal scale and rated using 3 = yes, 2 = unsure, and 1 = no. Larger values suggested greater perceptions towards PNRM. For the supplementary open-ended questions, the respondents narrated their experiences and knowledge on PNRM. However, questions addressing the attitudes of the local communities towards ‘managing natural resources through participatory approach’, ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage watershed’ and ‘accepting the concept and practice of PNRM’ were measured by employing Likert scale and rated using 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = unsure, 2 = disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree through the semi-structured questionnaire survey (Cohen et al., Citation2000; Hren et al., Citation2004; Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016). Larger values reflected positive attitudes towards PNRM.

Data collection processes

To collect the survey questionnaire data, five Kebeles existing in five different landscape zones of the Jemma Watershed, Kelade Weha, Yeselame Fera, Weshaweshegn, Rome, and Salayesh Kebeles which are found in Menz Gera Midir (i.e. landscape-1), Menz Mama Midir (i.e. landscape-2), Basona Werana (i.e. landscape-3), Siyadebrena Wayo (i.e. landscape-4), and Ensaro (i.e. landscape-5) districts were purposely selected, respectively. Kebele is the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia. Those five Kebeles were selected based on their representativeness using various selection criteria, including agroecology, climate, altitude, topography, and slope. The detailed characteristics on the biophysical and socioeconomic features and also the contribution of the PNRM to improve the livelihoods of the local people living in the five study Kebeles were shown in Table .

Table 1. Characteristics of the five purposely selected study kebeles in the Jemma Watershed. According to Dejene (Citation2003) and Negash and Ermias (Citation1995), the traditional climate classification implies that ‘wurch’ refers to a very cold temperate highlands with a mean annual temperature of 6.5–10°C, a mean annual rainfall of 600–900 mm, and elevation of > 3,200 m a.S.l.; ‘Dega’ refers to cool and humid highlands with a mean annual temperature of 11.5–16°C, mean annual rainfall of 900–1,200 mm, and elevation of 2,300–3,200 m a.S.l.; ‘woina-Dega’ refers to temperate and cool sub-humid highlands with a mean annual temperature of 16–20°C, mean annual rainfall of 800–1200 mm, and elevation of 1500–2300 m a.S.l.; and ‘Kolla’ refers to warm semi-arid lowlands with a mean annual temperature of 20–27.5°C, mean annual rainfall of 200–800 mm, and elevation of 500–1500 m a.S.l

Local research permits were acquired from the administrative offices of the five study Kebeles. A printed descriptive summary of the research was read out to all the participants of the survey questionnaire and consent was obtained orally from all participants. We trained 10 persons (i.e. two from each of the aforementioned five Kebeles) as data collectors and conducted trial interviews in Mehal Meda town (i.e. a town in the Menz Gera Midir district which is also located within the Jemma Watershed) to test the efficiency of the data collectors, and also to ensure that all questions were clear. Participation was voluntary since respondents were not paid.

To collect the required data, a total of 420 randomly selected households were interviewed. The households were randomly selected through a lottery system based on their house identification numbers. Each questionnaire required about an hour to go through. The response rate was 100 % because the data gatherers conducted the household survey through direct house-to-house visits. Moreover, we held opportunistic informal discussions with individuals or groups of people. However, there was no overlap between participants in these informal discussions and household survey subjects. These discussions occurred based on self-initiated conversations by locals about our activities in their community or by individuals approaching us with information that they thought might be of interest to us to substantiate the data collected through the household survey. During all informal discussions, we communicated to the participants that their responses might be reported anonymously and we obtained their verbal consent to proceed. All the data were collected in February 2020.

Independent variables

The 23 independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors which were entered into the multiple linear regression models were presented in Tables .

Table 2. Sample characteristics and descriptive results of the study site

Table 3. Multiple linear regression model to predict the perceptions of the local people towards ‘the concept of PNRM’ (R2 = 0.784 (adj. R2 = 0.68), df = 22; F = 5.56, overall p < 0.0001), ‘the presence of PNRM practice’ (R2 = 0.715 (adj. R2 = 0.61), df = 22; F = 4.49, overall p = 0.0001), and ‘the problems with the existing PNRM system’ (R2 = 0.783 (adj. R2 = 0.72), df = 22; F = 6.82, overall p < 0.0001) introduced in the Jemma Watershed. (+ = a positive change in perceptions and - = a negative change in perceptions). Standardized coefficients were reported

Table 4. Multiple linear regression model to predict the attitudes of the local people towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’ (R2 = 0.71 (adj. R2 = 0.63), df = 22; F = 4.83, overall p = 0.0001), ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’ (R2 = 0.82 (adj. R2 = 0.75), df = 22; F = 6.64, overall p < 0.0001), and ‘accepting the concept and practice of PNRM’ (R2 = 0.743 (adj. R2 = 0.65), df = 22; F = 5.842, overall p < 0.0001) introduced in the Jemma Watershed. (+ = a positive change in attitudes and - = a negative change in attitudes). Standardized coefficients were reported

Dependent variables

The dependent variables were derived from the following six statements: (i) perception towards ‘the concept of PNRM’ (i.e. it refers to what PNRM means to the local people, its importance, and how it is managed); (ii) perception towards ‘the presence of PNRM practice in the Jemma Watershed’ (i.e. it simply represents the response of the local people on the existence of the PNRM approach in study site); (iii) perception towards ‘the problems with the existing PNRM system implemented in the Jemma Watershed’ (i.e. it signifies the response of the local people on the drawbacks and/or costs of PNRM to them); (iv) attitude towards ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed’ (i.e. it implies the role of the local people in the protection and management of natural resources through the PNRM approach); (v) attitude towards ‘accepting the PNRM practice implemented in the Jemma Watershed’ (i.e. it refers to the willingness of the local people to accept the PNRM approach); and (vi) attitude towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’ (i.e. it represents the involvement of the local people to manage the natural resources by engaging in PNRM activities).

Data analyses

A quantitative technique was used to analyze and interpret the data. The data analyses utilized descriptive statistical tool, such as percentage, mean, and standard deviation values to compute and display the pattern and the nature of the characteristics of the surveyed households. Moreover, multiple linear regression models were used to predict the values of the dependent variables, i.e. the perceptions and the attitudes of the local communities as functions of the independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, bio-physical, institutional, and cognitive factors (Gashu & Aminu, Citation2019; Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017).

Prior to running the multiple linear regression analyses, we tested the continuous independent variables for collinearity using Spearman Rank Analysis and Pearson r Correlations, as appropriate, and the categorical variables using Pearson Chi-square to test the association between the categorical variables (Gomez & Gomez, Citation1984; Hazzah, Citation2006). The cut-off value for significance of the Spearman Rank and the Pearson was r > 0.70 and p < 0.001, respectively. We also tested the variance inflation factor (VIF) and checked the variance decomposition proportions. However, both tests confirmed that there was no collinearity among the predictors. Finally, we ran additional diagnostic tests to check for the presence of outliers, influential observations, and heteroscedasticity (Fox, Citation1997; Gomez & Gomez, Citation1984; Zar, Citation1996). All test results were at normal levels, allowing proceeding with the multiple linear regression analyses. Then, multiple linear regression model [significance level of p < 0.05] was used to analyze and interpret the values of the dependent variables, i.e. the perceptions and the attitudes of the local communities towards the PNRM introduced and adopted in the Jemma Watershed. After accounting for multiple comparisons (23 tests per dependent variable) with a Bonferroni correction, p ≤ 0.002 was considered significant (Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020). This is because Bonferroni correction is a safeguard against multiple tests of statistical significance on the same data falsely giving the appearance of significance (Gomez & Gomez, Citation1984; Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016; Zar, Citation1996). All the analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Scientist (SPSS) Version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Profiles of the respondents

About 66% of the respondents were males, and the mean age of the respondents was about 54 years. The mean family size in a household was about 3.4 persons. Regarding the level of education, about 45.5% of the respondents went to primary school. Most of the respondents (89.5%) were engaged in mixed farming. The average annual income of the respondents was estimated to be 36,935.00 Ethiopian Birr (ETB).Footnote1 The majority of the respondents (78.5%) had livestock. However, the greater proportion of the respondents (77.69%) claimed that they did not have enough grazing land. In contrast, a considerable percentage (65.45%) of the respondents felt a need to keep more livestock than they had at present. Because they noted that having more livestock serves as insurance during crop failure. However, about 86.44% of the respondents noted that they had a shortage of fodder. On average, the respondents had lived in the Jemma Watershed for about 41.72 years. Regarding their history of settlement, 51.31% of the respondents noted that they had settled by their own interest in search of land. Similarly, most of the respondents (89.75%) have planned to stay in the Jemma Watershed in the future, and 95.79 % of them noted that they had their own private lands. The largest proportion of the respondents (84.69%) noted that they had not allocated their private landholdings for woodlot plantations. Consequently, about 82.81% of the respondents noted that they had a shortage of fuelwood (Table ).

Knowledge of the local communities on the PNRM introduced in the Jemma Watershed

On top of knowing what the Jemma Watershed meant to them, the respondents knew the concepts of watershed management. According to the respondents, the past natural resources and watershed management activities were exclusively handled by the local government. So, at that time, the local communities did not get substantial benefits from the Jemma Watershed. Moreover, the respondents noted that the past natural resources and watershed management practices had several negative implications, including the degradation of the natural resources especially following the downfall of the Dergue regime when there was lawlessness in Ethiopia. Moreover, the local people did not have good concepts about watershed management practices and their control over the natural resources was also negligible at that time. Since then, the majority of the respondents (85.30%) had good information on the concepts of PNRM. Hence, 46.25% of the respondents agreed to protect and manage the existing natural resources through the participatory approach. Also, about 87.5% of the respondents knew that there was a PNRM practice in their locality, and majority of them (79.72%) noted that the local communities agreed to accept the PNRM implemented in Jemma Watershed (Table ).

Majority of the respondents (85.88%) had knowledge on watershed management. For example, about 63.81% of the respondents were able to compare the status of the natural resources before and after the implementation of the PNRM system in the Jemma Watershed. As assert, they noted that the Jemma Watershed was not well-managed before the implementation of the PNRM. For example, they mentioned that deforestation, overgrazing, habitat destruction and fragmentation, illegal hunting, and agricultural land expansion were the major threats that accelerated land degradation in the Jemma Watershed. Moreover, the high rate of land use land cover changes and its subsequent negative impacts, including severe soil erosion was prevalent. However, after the implementation of the PNRM, the local communities were well informed on the concepts of PNRM so that the Jemma Watershed was properly protected and managed (Table ).

Also, most of the respondents (96.88%) knew other land use types in the Jemma Watershed, they noted that crop cultivation was their major mainstay since it increases their economy compared to other land use types. Thus, the respondents noted that their engagement in crop production affected the implementation of the PNRM in the Jemma Watershed. This is because the local communities spent more time on crop cultivation than engaging in the PNRM activities in the Jemma Watershed. On top of that, they considered the Jemma Watershed as a concealment habitat for wild animals and insects that used to damage their food crops. They also wanted to maximize their croplands on the indiscriminate clearance of the natural vegetation in the Jemma Watershed. Majority of the respondents (90.25%) also knew the existing area closure in the Jemma Watershed. Consequently, most of the respondents (85.31%) noted that there is a local tradition to plant and grow tree seedlings, including building physical soil and water conservation structures in their private landholdings or communal lands. For example, they noted that they planted and grew trees by using their indigenous knowledge without getting technical assistance from the natural resources management experts. However, more than three-fourth (78.4%) of the respondents got incentives (e.g. seeds, tree seedlings, credits, training, and technical supports) to plant and grow trees in their private landholdings or communal lands. About 90.75% of the respondents reported that the Ethiopian Government had given due recognition to their traditional watershed management practice. Most importantly, 92.19% of the respondents agreed that they had the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. As a result, they have continued to actively participate in the management process and contribute to enhancing the conservation and sustainable utilization of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed (Table ).

Even though a majority of the respondents (63.81%) got various benefits from the PNRM practice in the Jemma Watershed, about 71.12% of the respondents reported that there were problems upon the implementation of the PNRM, such as livestock predation by wild animals, death of livestock being infested by insects and pests, crop damage by vermin wild animals, conflicts arising from inequitable benefit-sharing, prohibition of free-access to area closures, loss of time for the local communities during their engagement in watershed management activities that could otherwise be used for crop cultivation, resource competition, and paying penalties while one was arrested exploiting the natural resources in the area closures (e.g. illegally collecting fuelwood, cutting trees, and free-range livestock grazing). However, about 68.3% of the respondents noted that they had traditional bylaws used to restrict people and/or livestock from illegally destroying the tree seedlings planted and grown and/or soil and water conservation physical structures built in their private landholdings or communal lands (Table ).

The effects of the independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors on the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM

The multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors significantly affected the perceptions of the local people towards ‘the concept of PNRM’, ‘the presence of PNRM practice’, and ‘the problems with the existing PNRM’ (Table ).

As revealed from their coefficients, age, level of education, benefited due to PNRM, those who had the tradition to plant and grow trees and/or construct physical soil and water conservation structures on their private landholdings or communal lands, those who got incentives to plant and grow trees in their private landholdings or communal lands, those who had traditional bylaws used to restrict people and/or livestock from illegally destroying the tree seedlings planted and/or soil and water conservation physical structures built in their private landholdings or communal lands, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management positively affected the perceptions of the local people towards ‘the concept of PNRM’. In contrast, annual income, those who wanted to keep more livestock in the future, those who had a shortage of fodder for their livestock, and shortage of fuelwood negatively affected the perceptions of the respondents towards ‘the concept of PNRM’ in the Jemma Watershed (Table ).

Also, age, education, those who were benefited due to PNRM, those who had the tradition to plant and grow trees and/or construct physical soil and water conservation structures, those who got incentives to plant and grow tree seedlings, those who had traditional bylaws, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management had profound perceptions towards ‘the presence of PNRM practice’. However, annual income, those who wanted to keep more livestock in the future, those who had shortage of fodder, and those who had shortage of fuelwood significantly had shallow perceptions towards ‘the presence of PNRM practice’ (Table ).

Furthermore, age, livestock ownership, plan to stay in the area in the future, allocation of land for woodlot plantation, length of duration of residence in the area, tree growing tradition, those who got incentives to plant and grow trees, those who had traditional bylaws, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management positively affected the perceptions of the local communities towards ‘the problems with the existing PNRM system’. In contrast, family size and history of settlement negatively affected the perceptions of the local people towards ‘the problems with the existing PNRM system’ in the Jemma Watershed (Table ).

Overall, the multiple linear regression models revealed that the independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors had significant effects on the three groups of the dependent variables, i.e. perceptions towards ‘the concept of PNRM’ (68% variance explained), ‘the presence of PNRM practice’ (61% variance explained), and ‘the problems with the existing PNRM’ (72% variance explained) (Table ).

The effects of the independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors on the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM

The multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors significantly affected the attitudes of the local people towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’, ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’, and ‘accepting the concept and the practice of PNRM’ in the Jemma Watershed (Table ).

As revealed from their coefficients, those who were aged, those who were educated, those who had a long duration of residence in the area, those who had the plan to stay in the area in the future, benefited due to PNRM, those who had the tradition to plant and grow trees and/or construct physical soil and water conservation structures, those who got incentives to plant and grow trees, those who had traditional bylaws, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management significantly had positive attitudes towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’. In contrast, those who had high annual income and those who had enough grazing land significantly had negative attitudes towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’ (Table ).

Also, those who were aged, those who were educated, those who had livestock, those who had a shortage of fodder for their livestock, those who had a long duration of residence in the area, those who had the plan to stay in the area in the future, those who had a shortage of fuelwood, benefited due to PNRM, those who had the tradition to plant and grow trees and/or construct physical soil and water conservation structures, those who got incentives to plant and grow trees, those who had traditional bylaws, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management significantly had positive attitudes towards ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’. In contrast, those who had high annual income and those who allocated land for woodlot plantations significantly had negative attitudes towards ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’ (Table ).

Furthermore, those who were aged, those who were educated, those who had a long duration of residence in the area, those who had the plan to stay in the area in the future, those who had shortage of fuelwood, those who benefited due to PNRM, those who got incentives to plant and grow trees, those who had traditional bylaws, knowledge on area closure, and knowledge on watershed management significantly had positive attitudes towards ‘accepting the concept and the practice of PNRM’. However, those who had enough grazing land for their livestock and wanted to keep more livestock in the future significantly had negative attitudes towards ‘accepting the concept and the practice of PNRM’ (Table ).

In general, the multiple linear regression models revealed that the independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors had significant effects on the three groups of the dependent variables, i.e. attitudes towards ‘managing the natural resources through participatory approach’ (63% variance explained), ‘having the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources’ (75% variance explained), and ‘accepting the concept and the practice of PNRM’ (65% variance explained) (Table ).

Discussion

Empirical scientific studies dealing with the perceptions and the attitudes of local people towards PNRM approach are very limited in Ethiopia (Kelbessa & Destoop, Citation2007; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). To fill the gap of scientific knowledge, this study examined the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM and its developmental interventions, identifying sources of conflicts and proposing optimal solutions required for proper natural resources conservation, management, and policy- and decision-making processes in the context of the Jemma Watershed. Accordingly, the study attempted to explore the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people that possibly influence their engagements in the co-management scheme of the Jemma Watershed through PNRM approach. This is because perceptions and attitudes are important antecedents of people’s behavior with respect to natural resources conservation and watershed management (Admassie, Citation1995; Jotte, Citation1997; Pankhurst, Citation2001). Many contemporary studies also considered the perceptions and the attitudes of local people as major topics, mostly in relation to conservation projects (Badola, Citation1998; Mehta & Heinen, Citation2001; Mehta & Kellert, Citation1998) or in the context of natural resources conservation and watershed management (Gillingham & Lee, Citation1999; Kideghesho et al., Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation2009; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017).

The present study revealed that most of the respondents were eager to engage in PNRM activities in the Jemma Watershed. Previous studies also noted that rural households are often involved in planting, growing, managing, harvesting, collecting, processing, consuming, and selling of natural resources (e.g. timber and non-timber forest products) to compliment the deficient outputs from the agricultural activities (Ham, Citation2000; Shackleton et al., Citation2007; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). Generally, the present study revealed that the local people had positive perceptions and attitudes towards the PNRM introduced in the Hemma Watershed. The positive perceptions and attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM may be connected with the perceived benefits (e.g. employment opportunities, wood products, source of fodder for livestock through cut and carry system, and traditional beehive keeping to produce honey) and the other perceived values (e.g. recreational, aesthetic, cultural, and medicinal) that the local people expect upon the implementation of the PNRM. It is also widely documented that the decision by local people on whether or not to participate in PNRM activities is largely determined by the perceived benefits by the local people (Dale, Citation2000; Pongquan, Citation1992; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012).

Most of the respondents were aware of the rapid land use land cover changes resulting from the various anthropogenic factors (e.g. deforestation, illegal settlements, agricultural land expansion, urbanization, unprescribed burning of natural vegetations, and over grazing) and the subsequent negative impacts (e.g. soil erosion and land degradation) in the Jemma Watershed. So, they expressed their keen interest towards the proper implementation of the PNRM to reverse the environmental challenges and also to sustainably obtain timber and non-timber forest products and other useful watershed outputs (e.g. clean water). Moreover, most of the respondents believed that vegetation cover helps preserve the fertility of soils and also reduce their susceptibility to erosion by water and/or wind. Consequently, the findings of the present study revealed that the local people had developed positive attitudes towards the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed. Thus, a majority of the respondents expressed their readiness and willingness to actively involve in natural resources conservation and watershed management through accepting and practicing the PNRM approach. Acceptance of PNRM by the respondents was clear because many of them preferred the Jemma Watershed to be owned and managed by them. They also reported the importance of establishing links with non-government organization, for example, GIZ, which is an international NGO that engages in the conservation of natural resources by applying both biological and physical mechanisms through PNRM. Also, the GIZ was appreciated by the respondents for providing technical trainings to the local communities on the protection, conservation, management, and sustainable utilization of the natural resources, including the various benefits to the local people.

The multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors significantly affected the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed. For example, in line with our first hypothesis, the results revealed that there was significant difference in the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM. In support of our second hypothesis, the results revealed that there is significant variation in the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM, depending on their previous benefit-sharing experience (i.e. access to and control over the natural resources) from PNRM, knowledge on area closure, and watershed management. Let us briefly discuss some of the independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors which had significant effects on the perceptions and the attitudes of local people towards PNRM as followed.

Demographic factors and the perceptions of the local communities towards PNRM

The positive correlation between the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM with the increase in the age of the respondents suggested that, unlike young people, old persons may stay more frequently in their residential areas throughout the year so that they need to meet their livelihoods by increasing their incomes, e.g. job opportunity created by working on watershed management activities and/or through the sale of the products of natural resources (e.g. fuelwood, honey, construction materials, thatch, and the likes). Hence, they may show higher willingness to actively involve in PNRM activities. In contrast, young people may migrate to the nearby urban areas to look for job opportunities because they mostly expect better lives in towns. Hence, unlike old people, youngsters may show lower dependencies on PNRM to meet their livelihoods (Tafere & Nigussie, Citation2018; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020). In contrast, family size negatively affected the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM. This could be attributed to the fact that when family size increases, households want to expand their agricultural lands on the indiscriminate expense of natural fields in the Jemma Watershed, and thereby not interested to participate in PNRM, for fear that it restricts their access to expand farmlands inside the area closures in the Jemma Watershed.

Socio-economic factors and the perceptions of the local communities towards PNRM

Among the independent variables expected to affect the participation of the local people in PNRM approach, education had positive significant effect. This could be attributed to the fact that experience and knowledge play a central role to understand the nature and implication of PNRM on the livelihoods of the local people living in the surveyed five Kebeles of the Jemma Watershed. This could be also due to the interest of the local people to understand and involve in PNRM resulting from the increase in their level of education.

In contrast, income was found to have a negative significant effect on the perceptions of the local people towards the PNRM. This is because local people having a substantial amount of annual income might not be interested to actively participate in natural resources conservation and integrated watershed management through the PNRM. Similarly, the findings suggested that respondents who had a shortage of fodder for their livestock had developed negative perceptions towards PNRM. One of the possible reasons could be local people with a shortage of fodder may be eager to access forage through free-range livestock grazing inside the area closures in the Jemma Watershed. Moreover, the results revealed that respondents with shortage of fuelwood had negative perceptions towards PNRM. This might be attributed to the increase in the interest of the local people to freely collect fuelwood inside the area closure if the PNRM had not been introduced in the Jemma Watershed. Moreover, the respondents were not interested to know about the PNRM because they thought that the implementation of the PNRM would have blocked their free access to the available natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. Previous studies also noted that the negative perceptions of the local people could result from the low levels of awareness of the local people on the typical role of the PNRM approach to protect, conserve, manage, and sustainably utilize the natural resources (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2018; Tafere & Nigussie, Citation2018; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012).

Institutional factors and the perceptions of the local communities towards PNRM

The presence of incentives and traditional bylaws positively affected the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM. This is because incentives initiate local people to actively participate in development projects (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2018; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012), including the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed. Most importantly, local people will be more respectful to the laws of introduced projects, including PNRM when they have their own traditional bylaws (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020). In contrast, history of settlement by the respondents in the Jemma Watershed had negatively affected the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM. This could be due to the fact that local people who recently settled in the study watershed for the sake of expanding agricultural lands may develop the fear against the PNRM. This is because the introduction and implementation of such kind of approach may displace those local people from their illegally owned farmlands.

Cognitive factors and the perceptions of the local communities towards PNRM

Knowledge on area closure and watershed management positively affected the perceptions of the local people towards PNRM. This could be attributed to the increase in the understanding capacity of the respondents considering that area closure and integrated watershed management activities are promising approaches to restore the degraded environment in the Jemma Watershed.

Demographic factors and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM

The increase in the positive attitudes of the local people towards PNRM with the rise in the age of the respondents suggested that, unlike young people, old people may be historically linked with the natural resources of their locality because they are usually sedentary in their residential areas throughout the year. Hence, they may develop positive attitudes towards engaging in PNRM activities. In contrast, young people may move to the nearby urban areas to look for job opportunities because they mostly expect better lives in towns. Hence, unlike old people, youngsters may show lower dependencies on PNRM to meet their livelihoods, suggesting that young people may not worry to have positive attitudes towards PNRM in the Jemma Watershed.

Socio-economic factors and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM

The rise in the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM with the increase in the length of local residence in the area is attributed to the fact that local communities may be more worried and careful for their natural environment when they reside in the area for an extended period of time. Moreover, the protection, conservation, and management of natural resources through PNRM have various environmental functions, including flood and erosion control, carbon sequestration, aesthetic and recreational values, and regulating the microclimates (M. Bekele, Citation2011; Tadesse, Citation2019). As a result, local farmers may show higher dependencies on the Jemma Watershed when the length of their residence in the area increases. Previous studies also reported that local people show higher dependencies on natural resources for their various socio-economic values when their residence in an area becomes longer (Tadesse & Tafere, Citation2017; Gashu & Aminu, Citation2019; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019).

The positive correlation between the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM with the consent of the respondents who had the plan to stay in the area in the future is explained by the fact that local farmers may be more worried and careful for protecting and managing their natural environment. Hence, they may engage in watershed management activities through PNRM considering that watersheds may provide them with a lot of environmental services (Ayele, Citation2008; M. Bekele, Citation2011; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2018). Moreover, those farmers who had the plan to live in their present residential area in the future may believe that watersheds may provide them with various environmental, economic and social values, which are of crucial to support their livelihoods (Tadesse, Citation2019; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019). It is evident that PNRM has played a multiple role to improve the livelihoods of the local communities. Previous studies also noted that watershed management is essential to conserve the local biodiversity, keep the ecological integrity, enhance soil nutrients and water availability, regulate local climate, and also serve as source of income especially for the rural poor (T. Bekele, Citation2015; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tafere & Nigussie, Citation2018).

However, those individuals who had shortage of fodder may be worried to meet the fodder requirements for their livestock so that they developed negative attitudes towards the implementation of PNRM. This is because they believe that the costs that they invest in the management of the Jemma Watershed through the PNRM approach would be greater than the benefits that they would obtain from it. Similarly, respondents with shortage of fuelwood had negative attitudes towards the PNRM because the implementation of the participatory natural resources and integrated watershed management may restrict their access to freely collect fuelwood from the area closure inside the Jemma Watershed. In another instance, our findings revealed that respondents with high annual income had negative attitudes towards managing the Jemma Watershed through the participatory approach. This is because they may give less emphasis on the PNRM only by considering its economic value, suggesting that those respondents need awareness on the different values of PNRM.

Similarly, those respondents who had enough grazing land had negative attitudes towards the concept of PNRM. One possible explanation is that they may develop the fear that the introduction and implementation of PNRM would inevitably restrict free-grazing inside the Jemma Watershed in the future. Most importantly, those local people may think only for their private lives and immediate interests rather than that of the general public. Moreover, those respondents may also ignore the long-term benefits that could be generated when the Jemma Watershed is properly managed through PNRM. In addition, lack of detail critical awareness on the concept of PNRM and its positive implications on the livelihoods of the local people may be another possible reason that aggravate the negative attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed. In another instance, the decline in the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM with the rise in the number of respondents, who wanted to keep more livestock than they have at present, is attributed to the fact that livestock ownership serves as insurance to support the livelihoods of the local people during crop failure and/or when they do not have sufficient socio-economic resources to rely on. As a result, local communities may show lower interest to actively involve in PNRM when they want to keep more livestock than they have at present. Similarly, previous studies noted a decrease in the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM when they want to keep more livestock than they have at present and/or when they have a greater number of means to support their livelihoods, other than relying on the socio-economic values of watersheds (Shackleton et al., Citation2007; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2020).

Institutional factors and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM

Our findings revealed that the attitudes of the respondents were positively affected by previous experience on benefit-sharing scheme. As the benefits generated by the Jemma Watershed were not equally distributed among the local communities, those who previously benefited significantly developed positive attitudes towards the PNRM. Previous studies also noted that promoting equitable benefit-sharing mechanism among the rural people may increase the positive attitudes towards PNRM (Admassie, Citation1995; Pankhurst, Citation2001; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, when the local framers actively engage in PNRM activities, the watershed may provide them with various wood and non-wood products, which are essential to improve and diversify their incomes (Shackleton, Citation2004; Shackleton et al., Citation2007; Tadesse & Tafere, Citation2017). This, in turn, suggests that the dependencies of local communities on watershed become greater when the local farmers plant and manage trees on their private landholdings or communal areas.

The positive correlation between the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM with the privilege to get incentives (e.g. seeds, tree seedlings, credits, training, and technical supports) to plant and grow multipurpose trees in their private landholdings or communal lands is explained by the rise in the motivation and inspiration of the local people to engage in natural resources conservation and management activities through PNRM. Previous studies also noted that local people usually develop positive attitudes towards PNRM, including participatory forest management when they get incentives to engage in such activities (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). Moreover, the increase in the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM with the availability of traditional bylaws that the respondents used to restrict people and/or livestock from illegally destroying the tree seedlings planted and/or soil and water conservation physical structures built in their private landholdings or communal lands could be explained by the essence of knowledge and experience how to conserve and manage the natural resources in their localities. Previous studies also claimed that the presence of traditional bylaws initiate local people to actively engage in natural resources conservation and management activities (Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tafere & Nigussie, Citation2018; Woldie and; Tadesse, Citation2019). However, the present study revealed that those respondents who have allocated their plots of land for woodlot plantations developed negative attitudes towards PNRM. This is because those local people may show lower dependencies on PNRM to meet their wood demands, suggesting that those people may not worry to have positive attitudes towards the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed.

Cognitive factors and the attitudes of the local communities towards PNRM

The study suggested that local people who had good knowledge on area closure and watershed management had developed positive attitudes towards managing the watershed through participatory approach. Previous studies also noted that the attitudes of local people towards PNRM can be positively influenced by increasing their knowledge and experience (Pankhurst, Citation2001; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). More importantly, public awareness programs and conservation education can assist in improving the attitudes of young people towards PNRM (Tadesse & Kotler, Citation2016; Tadesse & Teketay, Citation2017, Citation2018). Moreover, promoting the direct involvement of the local residents in decision-making and implementation of the PNRM strategic and operational plans can also help mitigate the potential conflicts and ensure long-term public supports towards the PNRM approach (Admassie, Citation1995; Pankhurst, Citation2001; Tesfaye, Citation2011).

In general, the study has generated crucial insights and knowledge on PNRM. For example, before the introduction of the PNRM, the respondents noted that deforestation, overgrazing, unprescribed fire, habitat destruction and fragmentation, illegal hunting, and agricultural land expansion even on very steep slopes and rugged terrains were the major causes for the degradation of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. While focusing on the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM, the present study contributed to improving our insights and understandings on the human dimensions of natural resources conservation and watershed management. This may motivate natural resources and watershed managers to give due attentions to the local communities while formulating strategic and operational plans for the PNRM in the Jemma Watershed. In the context of community-based watershed conservation and management, participants’ understandings or perceptions of the purpose and the implication of the arrangements with respect to their interest and, thus, the attitudes they form influence their willingness and commitment for PNRM implementation (Gellich et al., Citation2005; Husain & Bhattacharya, Citation2004; Tesfaye et al., Citation2012). Other than academic purpose, the present study generated relevant scientific insights that may assist and guide watershed management planners and policy makers towards better and more informed decision-making for appropriate PNRM establishment and implementation that is geared towards communal watershed management, and thereby achieving the broad goal of poverty reduction in Ethiopia.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that majority of the respondents (92.19%) agreed that they had the responsibility to protect and manage the natural resources through PNRM approach. However, the findings suggested that there were also some respondents who were yet unsure to fully accept the concept and practice of PNRM. This may have happened due to the low level of awareness of the local people on PNRM and also their long period of dependencies on the direct exploitation of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. The acceptance of the PNRM by the local communities was very clear in which a majority of them preferred the Jemma Watershed to be owned and managed by them. This is because majority of the respondents (63.81%) confirmed that they have been benefited due to the implementation of the PNRM practice in the Jemma Watershed. As for instance, among the most prominent perceived benefits to the local people due to the presence of the PNRM program in ascending order were: source of income from visiting eco-tourists, employment opportunity, wood products (e.g. fuelwood and construction materials), getting free transport during hardship period, aesthetic and recreational values of the beautiful natural landscape, access to free-range livestock grazing, source of fodder for livestock through cut-and-carry system, traditional beehive keeping and source of honey, infrastructure development, and source of medicinal plants used to treat humans and livestock (Table ).

The multiple linear regression models revealed that several independent variables derived from demographic, socioeconomic, institutional, and cognitive factors significantly affected the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM program and practice implemented in the Jemma Watershed. The resulting insights and knowledge reported in this study may assist watershed managers, land use planners, natural resources conservation managers, soil and water conservation experts, foresters, hydrologists, biodiversity conservation experts, local communities, private and public sectors while addressing the opportunities (e.g. the willingness to participate in PNRM) and the challenges (e.g. negative attitudes towards accepting the PNRM program and practice) to restore, protect, manage, and sustainably utilize the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed. Therefore, the effective protection, conservation, management, and sustainable utilization of the natural resources in the Jemma Watershed need the full involvement of many stakeholders, including the local communities.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the present study, the following points were recommended:

Creating public awareness on PNRM and promoting community-based integrated watershed management program and practice is crucial to alleviate the problems of deforestation and land degradation, and thereby contribute to enhancing the sustainable use of the natural resources. Also, awareness creation on the relevance of PNRM is essential to enhance the positive perceptions and attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM implemented in the Jemma Watershed.

As there are still a substantial percentage (36.19%) of the local people who haven’t yet received benefits from the PNRM program in the Jemma Watershed, appropriate rules and regulations should be formulated and strictly put in practice to ensure equitable benefit-sharing scheme among the participants of the PNRM.

Programmers and the implementing watershed managers should develop a two-way communication system with local farmers to move ahead with PNRM and integrated watershed management.

Extension agents should treat local farmers as people with valuable information and knowledge on PNRM and integrated watershed management since they are vital for providing insights on how the needs of the local people can be met, which includes maintaining sound environmental conditions.

Integration of indigenous knowledge with modern management approaches in the planning and implementation process is crucial to improve and promote local participation in PNRM and integrated watershed management because local knowledge not only provides relevant information on the use of the natural resources in a watershed, but also contributes valuable information on how to maintain and conserve it.

As the independent variables derived from demographic, socio-economic, biophysical, institutional, and cognitive factors that likely affect the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards PNRM may change over time, a follow up research is crucial to consider the time dimension as another possible factor while studying the perceptions and the attitudes of the local people towards the PNRM in the Jemma Watershed and elsewhere.

Authors’ contributions

NTZ: Designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript, MAD: Wrote and edited the manuscript, and SAT: Analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

All the authors are indebted to warmly thank the two anonymous reviewers for their critical comments which helped much to improve our research manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. 1 USD = 29.21 ETB at the time of the study.

References

- Admassie, Y. (1995). Twenty Years to Nowhere – Property Rights, Land Management and Conservation in Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation. Uppsala University,

- Ali, Y. S. A., Crosato, A., Mohamed, Y. A., Abdalla, S. H., & Wright, N. G. (2014). Sediment balances in the Blue Nile River Basin. International Journal of Sediment Research, 29(3), 316–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-6279(14)60047-0

- Ameha, A., Larsen, H. O., & Lemenih, M. (2014). Participatory Forest Management in Ethiopia: Learning from pilot projects. Environmental Management, 53(4), 838–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0243-9

- Ayele, Z. E. (2008). Smallholder farmers’ Decision Making in Farm Tree Growing in the Highlands of Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation. Oregon State University, (pp 158)

- Badola, R. (1998). Attitude of local people towards conservation and alternative forest resource: A case study from the lower Himalaya. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 7(10), 1245–1259. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008845510498

- Bekele, M. (2011). Forest plantations and woodlots in Ethiopia. African Forest Forum Working Paper Series,

- Bekele, T. (2015). Integrated utilization of Eucalyptus globulus grown on the Ethiopian highlands and its contribution to rural livelihood: A case study of Oromia, Amhara and southern nations nationalities and People’s Regional State, Ethiopia. International Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(2), 80–87.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th edn ed.). Routledge Falmer.

- Dale, R. (2000). Organizations and development: Strategies, structures and processes. Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd. New Delhi, India. (pp. 180).

- Dejene, A. (2003). Integrated Natural Resources Management to enhance food security: The case for community-based approaches in Ethiopia. Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Elias, K. (2004). People’s Perception of Forest and Livelihood in Joint Forest Management Area, Chilimo, Ethiopia. Unpublished MSc Thesis. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences,

- EMA (Ethiopian Mapping Authority). (1981). National atlas of Ethiopia. Berhanena Selam Printing Press, Addis Ababa.

- Fox, J. (1997). Applied regression analysis, linear models, and related models. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Gadd, M. E. (2005). Conservation outside of parks: Attitudes of local people in Laikipia, Kenya. Environmental Conservation, 32(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892905001918

- Gashaw, T., Tulu, T., Argaw, M., Worqlul, A. W., Tolessa, T., & Kindu, M. (2018). Estimating the impacts of land use/land cover changes on ecosystem service values: The case of the andassa watershed in the Upper Blue Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Ecosystem Services, 31, 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.05.001

- Gashu, K., & Aminu, O. (2019). Participatory forest management and smallholder farmers’ livelihoods improvement nexus in Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 38(5), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2019.1569535

- Gellich, S., Edwards, J., & Kaiser, G. M. J. (2005). Importance of attitudinal differences among artisanal fishers towards co-management and conservation of marine resources. Conservation Biology, 19(3), 865–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00534.x

- Gillingham, M. S., & Lee, P. C. (1999). The impact of wildlife-related benefits on the conservation and attitude of local people around the Selouse Game Reserve, Tanzania. Environmental Conservation, 26(3), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892999000302

- Gomez, K. A., & Gomez, A. A. (1984). Statistical procedures for agricultural research (2nd edn ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Ham, C. (2000). The importance of woodlots to local communities, small scale entrepreneurs and indigenous forest conservation. International Institute for Environment and Development and CSIR-Environment.

- Hazzah, L. (2006). Living among lions (Panthera leo): Coexistence or killing? Community attitudes towards conservation initiatives and the motivations behind lion killing in Kenyan Massai land. Conservation biology and sustainable development [MSc Thesis]. (pp. 156). University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Hren, D., Lukic, I. K., Marusic, A., Vodopivec, I., Vujaklija, A., Hrabak, M., & Marusic, M. (2004). Teaching research methodology in medical schools: Students’ attitudes towards and knowledge about science. Medical Education, 38(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01735.x

- Husain, Z., & Bhattacharya, R. M. (2004). Attitudes and institutions: Contrasting experience of joint forest management in India. Journal of Environmental Development and Economics, 9(4), 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X04001548

- Irwin, B. (2000). The experiences of FARM-Africa, SOS-Sahel and GTA 4: Developing PFM. (pp.78).

- Jotte, Z. (1997). Folklore and conservation in Nigeria: Using PRA to learn from elders, ichire orating and the students. The Federal University of Agriculture.

- Kebede, S., Travi, Y., Alemayehu, T., & Marc, V. (2006). Water balance of Lake Tana and its sensitivity to fluctuations in rainfall, Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 316(1–4), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.011

- Kelbessa, E., & Destoop, C. (2007). Participatory Forest Management (PFM), biodiversity and livelihoods in Africa. Proceeding in international conference. 19-21 March 2007, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Kelboro, G., & Stellmacher, T. (2015). Protected areas as contested spaces: Nech Sar National Park, Ethiopia, between ‘local people’, the state, and NGO engagement. Environmental Development, 16, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2015.06.005

- Kelley, J., & Scoones, I. (2000). Knowledge, power and politics: The environmental policy-making process in Ethiopia. Journal of Modern African Studies, 38(1), 89–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X99003262

- Kideghesho, J., Roskaft, R. E., & Kaltenbornb, P. (2007). Factors influencing conservation attitudes of local people in Western Serengeti, Tanzania. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 16(7), 2213–2230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-006-9132-8

- Lee, T. M., Sodhi, N. S., & Prawiradilaga, D. M. (2009). Determinants of local people attitudes towards conservation and the consequential effects on illegal resource harvesting in the protected area of Sulawesi (Indonesia). Journal of Environmental Conservation, 36(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892909990178

- Mehta, J. N., & Heinen, J. T. (2001). Does community-based conservation shape favorable attitudes among locals? An empirical study from Nepal. Environmental Management, 28(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002670010215

- Mehta, J. N., & Kellert, S. R. (1998). Local people attitudes towards community-based conservation policy and programmes in Nepal: A case study in the makalu-barun conservation area. Environmental Conservation, 36(4), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689299800040X

- Negash, M., & Ermias, B. (1995). Towards a Comprehensive Agro-Ecological Zonation of Ethiopia. In LUPRD, agro-ecology section, Ministry of Agriculture, Addis Ababa (pp. 20).

- Nelson, N., & Wright, S. (1995). Power and participation. In N. Nelson & S. Wright (Eds.), Power and participatory development: Theory and practice (p. 240). ITDG Publishing.

- Oskamp, S. (1977). Attitudes, values and opinions. Englewood cliffs, N. J. Prentice Hall.

- Pankhurst, A. (2001). State and community forests in Yegof, South Wollo, Ethiopia. MARENA working paper, No. 6. Brighton: University of Sussex. Paper presented at the second workshop on participatory forestry in Africa, 18-22 February 2002,

- Pongquan, S. (1992). Participatory development activities at local level: A case study in villages of central Thailand [PhD Dissertation]. (pp. 371). Wageningen University & Research, The Netherlands.