?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The poor integration of pastoral households into milk markets has been attributed to several aspects, including the mobile nature of pastoralists and seasonal fluctuations in milk volumes. Pastoralists also keep their cattle as a store of wealth, meaning they are keener to increase livestock numbers than their productivity. These aspects make it risky for traders to source milk from pastoral households because of the high transaction costs and the uncertainty of milk prices and volumes. This study evaluates the practice of sourcing milk and the innovative strategies used by several traders to ensure that pastoral households are integrated into milk markets. Methodologically, we use the practice approach, where practices are meaning-making and order-producing activities that result in an institutionalised way of doing. The results indicate that previous market engagement for pastoralists took place in a rigid, predetermined context that failed to account for pastoralists’ varying production practices. Our analysis shows how the skilful performance of traders and motorbike milk aggregators has aligned with the logic and interests of pastoralists. However, this alignment capacity can only be realised under specific conditions, which involve aligning with local production systems, coordinating with intermediaries, and having a flexible approach to marketing prices and buyers across seasons. This study highlights that economic organisation emerges from everyday action and problem-solving and is not only an outcome of an intentional system design. In doing so, this study contributes to more realistic needs-driven business intervention strategies that are beneficial in achieving inclusive rural development.

1. Introduction

Policy and intervention strategies account for the need for market access in catalysing development (Roba et al., Citation2017; Sinja et al., Citation2006). As such, many governments, especially in developing countries, appreciate the private sector’s role in contributing towards rural development (Schoneveld, Citation2020). However, producers’ market access often remains a challenge, especially for pastoral households selling milk (Mccabe et al., Citation2010). Pastoralism is an extensive livestock production system, adapted to high variability in climatic and environmental conditions. It is dependent on mobility for cattle to utilise nutrients across heterogeneous landscapes (Nori, Citation2019; Simula et al., Citation2021). To address this, government policies and interventions promote Sedentarization in rangelands (Anderson, Citation2010). However, such policies do not respect the environmental logic underpinning pastoralists’ mobility culture (Anderson, Citation2010; Mdoe & Mnenwa, Citation2007). Although this narrative is continuously being challenged (Hallo Dabasso et al., Citation2021), creating and enabling alternative strategies that link pastoralists to milk markets without radically changing their production systems is difficult.

Consequently, approaches for linking pastoralists to milk markets are not self-evident – it is difficult to sell and buy a moving product – especially from households that are often on the move. Traders engaging pastoralists in milk markets are thus faced with a variety of challenges. First, the availability of marketable (surplus) milk in pastoral households is highly variable across seasons, with lower milk volumes during the dry season due to feed shortages and cattle migration in search of feed (Mccabe et al., Citation2010; Sadler et al., Citation2010). This affects sourcing structures, making it risky for traders and processors, who need a consistent and ample milk supply at a steady price. Second, customarily, pastoralists have kept their cattle for subsistence milk production and as a store of wealth, meaning they are keener to maintain livestock breeds that are more adaptable to the ever-changing environment rather than increasing their productivity (Krätli & Provenza, Citation2021). This, coupled with pastoralists’ high mobility, decreases the stability of available milk for buyers. Third, sourcing milk from pastoral households is marked by high transaction costs (Leonard et al., Citation2016). This is because pastoralists rarely bulk milk with others, partly due to their mobility and large herd sizes. Marketing strategies for pastoralists, therefore, must overcome these challenges, along with those presented by changing seasons and agroecological conditions.

Previous studies have provided valuable information on pastoralists’ market connections, but there is still some gap, especially in understanding the agency of business actors in enhancing market linkages for pastoralists’ milk marketing. For instance, strategies for linking pastoralists to milk markets are either non-existent or based on the processor-driven organisation of milk value chains and farmer-led cooperatives and do not consider the particularities of dryland livestock production systems (Makoni et al., Citation2014; Nell et al., Citation2014). Such systems allow for easier coordination and lower transaction costs in sourcing milk. However, such strategies have often failed because they present a mismatch between local pastoralists’ production practices and the milk marketing system’s needs. Previous research into pastoralists’ practices for increasing participation in livestock marketing has focused on increasing live animal sales (Barrett et al., Citation2004; Roba et al., Citation2017), the profitability of pastoral milk marketing (Leonard et al., Citation2016), and camel milk marketing (Noor et al., Citation2013).

A comprehensive understanding of milk marketing is paramount because milk is an essential global commodity for nutrition and income (Lemma et al., Citation2018). In East Africa, in countries like Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda, increased urbanisation, economic growth, dietetic changes, and a growing middle-income group have increased the demand for milk and other dairy products (Lemma et al., Citation2018; Nyokabi et al., Citation2023). This has resulted in annual growth of between 4–9% in local dairy production across various countries in the East African region over the past 5 years (Makoni et al., Citation2014). While the marketing of processed dairy products through formal channels has experienced substantial growth in other East African countries, e.g. Rwanda, this has stagnated in Tanzania, where only 2.4% of dairy commodities are sold as processed products (Lunogelo et al., Citation2020). However, the Tanzania national government policies on livestock prioritise modernisation within the livestock sector through improved practices and commercialisation typically oriented towards formal milk marketing via farmer cooperatives models or lead firms (Michael et al., Citation2018; The United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2004, Citation2015). These policies have tended to ignore the agency of business actors and how the business practice works and leads to inclusive economic engagement. Without understanding local socio-cultural contexts, lead firms and farmer cooperatives based on rigid marketing structures risk exacerbating societal inequalities, adverse incorporation and the exclusion of marginalised producers (Hickey & Toit, Citation2013; Schaltegger et al., Citation2016). We consider it of specific importance to understand better the agency of business actors in enhancing the engagement of pastoralists in milk markets.

The objective of this study is to assess why certain business practices of milk traders and collectors have been successful in connecting pastoralists to milk markets. We make an empirical contribution to identifying conditions in everyday business realities that make this connection viable. In doing so, we analyse business practices in dryland Tanzania that achieve alignment between pastoralists’ production practices and local traders’ milk-sourcing practices. Specifically, we start by analysing a lead firm’s failure due to rigid, predetermined milk sourcing practices. We then move on to examine subsequent milk sourcing by independent traders in the same area that has succeeded in engaging pastoralists in milk marketing. Using a case study approach, we analyse the relationships between producers and commercial buyers through the lens of alignment. Analysing alignment as a suite of practices highlights how traders engage in sophisticated and flexible market development to address producers’ needs and challenges, thus enabling their inclusion in market processes (A. M. Schouten et al., Citation2016). In this case study, we specifically examine the traders’ business practices by focusing on how markets self-organise and function to ensure a consistent flow of milk. By looking at everyday practices, we offer insight into the choices of traders operating within dynamic social structures and natural environments that ensure the inclusive economic engagement of pastoralists, which may also stimulate responsiveness in shaping socio-technical changes at the level of pastoralist producers.

We use a methodological approach that analyses traders’ day-to-day business practices that constitute the alignment of pastoral livestock keepers and commercial milk traders. We use a practice-based analysis to assess the interactions between human activities within dynamic natural dimensions (e.g. seasonal changes affecting feed and, in turn, milk volumes), which in turn shapes milk production. This highlights the complex relationships between the natural environment and human activities of production, which in turn shape business practices. In this context, we focus on the commensurability of traders’ and producers’ practices, each with their distinct logic, connected to the everyday business practice of sourcing milk across time and space. This includes establishing and maintaining networked relationships, unwritten rules and norms, task distribution, and daily milk collection routines while being flexible enough to allow for improvisation (Glover et al., Citation2017; Mangnus, Citation2019; Richards, Citation1993). The practice approach helps us to understand how everyday decisions are made in response to the varying production practices by transhumant pastoralists. In addition, the practice approach helps us to unravel why the strategies employed by the independent traders worked and the properties that can be attributed to the success of the traders. By using a practice approach, our analysis aims to demonstrate how economic organisation emerges not as an outcome of intentional system design but through decentralised processes and actions of solving dynamic everyday problems. We complement the inclusive business literature (Schaltegger et al., Citation2016; Schoneveld, Citation2020) by adding the importance of flexible processes and improvisation actions for solving everyday problems.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the research methodology, which includes a review of the practice approach to understanding business practice. Next, we introduce the case study by explaining our data collection and data analysis process. The subsequent results section presents findings on the emergence of innovative business practices in milk sourcing for pastoral households. The discussion focuses on the logic that allows business practices to enhance inclusivity and implications for development. Finally, the conclusion highlights the main messages and suggestions for policy and development practitioners, as well as future research directions for milk sourcing.

2. Research design

2.1. Methodology

We draw on the practice approach by Nicolini (Citation2011), who argues that “practices are meaning-making, identify-forming and order-producing activities. They institutionalise activities and ways of doing through repetition” (Nicolini, Citation2011, p. 7). In this context, “order-producing” means that practice is where business actions are shaped and reinforced. Using practice framing provides an analytical approach that highlights how economic and social outcomes are shaped by everyday activities and actions performed by actors to create an everyday economy (Mangnus & Vellema, Citation2019). Practices have a subject (the actor); they also have an object that is transformed into an outcome by performing a practice (Nicolini, Citation2011). Therefore, in this study, we look at how a group of traders (the subject) in Dakawa, Tanzania, organises the sourcing of milk (the object) by including pastoral households in milk selling (the outcome). We propose that this represents a novel business practice from which we can learn about mechanisms of inclusion.

To study the alignment of business and pastoral producers’ practices as an evolving social relationship in a dynamic context, we review various literature on institutional diagnostics – focused on the need to identify context before acting (Rodrik, Citation2010) – and the application of contextualised diagnostics of institutions in food systems (G. Schouten et al., Citation2018). From these studies, we borrow two key concepts that shape alignment. First, we examine the establishment of institutions that enable rule-setting in business practice that facilitates engagement between traders, intermediaries, and producers. In this study, we analyse traders’ business choices, engaging intermediaries, and the role of trust in ensuring economic engagement. Accounting for local production practices and variability is crucial in developing marketing systems responsive to local needs (Aspers, Citation2007; Schoonhoven-Speijer & Vellema, Citation2020). Second, we examined processes of self-reinforcement of the viable institutions that support business practices in sourcing milk (G. Schouten et al., Citation2018). Alignment reflects the interactions between traders and pastoralists within a set of locally embedded practices, rules, and norms that are both economic and social (Beer et al., Citation2005; Vellema et al., Citation2020).

The analysis presented in this study is organised around three dimensions of the dairy business in the study site. First, we analysed how traders and milk companies strategise and make choices to source milk from pastoralists in ways that meet the interests and needs of both parties. This starts with a chronology of previous abandoned arrangements by lead firms and then details of traders’ current practices. Here, we focused specifically on how rule-setting and self-enforcement practices happen across the various intermediaries. Second, we examined how traders and transporters navigate structural factors (e.g. ecological seasonality, mobility, poor road conditions) in their milk-sourcing practices. Third, because practices are mutually constitutive and continually evolving, we analysed how pastoralists change their production practices in response to traders’ new alignment practices. Engagement in milk selling requires a restructuring of practices at the production level, as well as shifts in norms and roles. We specified what these practices are and what they mean for the pastoralist communities.

2.2. Research context

Tanzania was chosen as the study’s location due to the country’s potential for dairy production, its significant milk productivity gap, its national milk deficit, and its per capita consumption gap (Katjiuongua & Nelgen, Citation2014; Nell et al., Citation2014). In Tanzania, 70% of the total national milk production comes from pastoral and semi-intensive systems (Michael et al., Citation2018). Approximately 50% of households keep livestock, which supports 27 million people (ibid). Milk plays an important role for pastoralists. This includes local food and nutrition security, income, and the ability for communities to engage and pay for other services, e.g. education and healthcare (Sadler et al., Citation2009). The sector also makes a significant contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP); livestock contributes 5.9% of the country’s GDP and 13% of the agricultural GDP, with the dairy industry accounting for almost one-third of the livestock GDP (Makoni et al., Citation2014). Tanzania, however, has a structural milk deficit and is dependent on imported dairy products (Nell et al., Citation2014; Tdb, Citation2018). In addition, Tanzanians only drink 45 litres of milk year, which is much less than the 200 litres per year suggested by the FAO, showing a substantial room for expansion in the dairy industry (Nell et al., Citation2014; Tdb, Citation2018). Increased purchasing power, urbanisation, and population increase all contribute to the dairy industry’s potential.

The dairy industry has been recognised as a key growth area in the country’s livestock master plan (Michael et al., Citation2018). The National Livestock Policy (2006), Livestock Development Strategy (2010–2015), The Dairy Industry Act from 920,040, and the Tanzania Livestock Modernization Initiatives (Citation2015) are further significant sector-level policies. These policies provide a general technical perspective on the livestock sector development with the main objective of intensification through technological dissemination and commercialisation, often through cooperatives and lead firms in the dairy sector. There is, however, little focus on how the commercialisation aspect will unfold beyond the defined models especially focusing on how business agency evolves(Vernooij et al., Citation2023).

Besides, the mobility of pastoralists is increasingly challenged, and many policymakers, either knowingly or unintentionally, promote policies of sedentarisation (Davies & Hatfield, Citation2007). For instance, the government policy on Ujamaa in 1975 and villagisation profoundly affected pastoral land, as pastoralists were forced to move into “planned villages” (Bee et al., Citation2002). More recently, the livestock identification, recording, and traceability systems implemented in Tanzania between 2016 and 2018 have caused a sharp decline in cattle mobility between districts and, in some instances within districts, they have further contributed to a decline in pastoral mobility (United Republic of Tanzania, Citation2010). Besides the national policies, villages – dominated by farmers – have implemented by-laws restricting herders’ movements from one village to another, and these are monitored by village councils (Sule & Mkama, Citation2019).

2.3. The case study: Milk selling in dakawa ward

This research used a case study approach conducted in the Dakawa ward within the Mvomero district in the Morogoro region of Tanzania. A case study approach allows for an in-depth, intensive study of a bounded phenomenon (Gerring, Citation2004). The phenomenon of study, in this case, is the practice of alignment of traders’ and pastoralists’ practices in milk selling. The detailed description of the business setting, actors, processes, and interactions (Vellema et al., Citation2013) lead to alignment. This case study allows us to study context-specific practices that shape alignment, and it provides insight into the complex and dynamic interactions that demonstrate how economic action evolves. This case study is particularly interesting because it evolved as a response to the producer’s need to sell milk without the involvement of the government or any other development organisation.

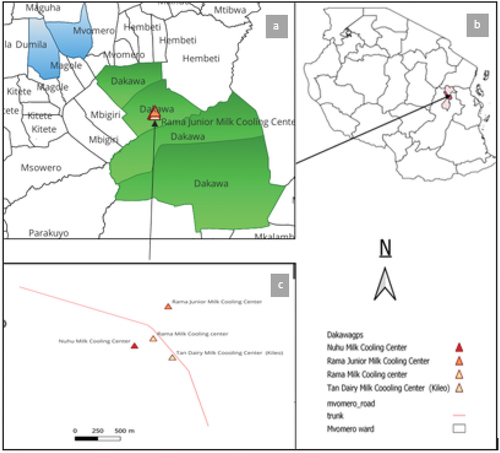

Dakawa was selected due to the high concentration of pastoral households selling milk and the availability of milk traders operating cooling centres. Dakawa is a big roadside village inhabited by both pastoralists and farmers (Mung’ong’o & Mwamfupe, Citation2003). It is located along Morogoro-Dodoma Road. Morogoro is only 47 km from Dakawa, with a good quality tarmac road linking the two towns. The urban population in Morogoro and crop farming households in Dakawa provide a good market for milk from Dakawa. Morogoro also provides a link to Dar es Salaam, the country’s business city, approximately 185 km from Dakawa. Urban consumers and large milk processors in Dar es Salaam provide an additional milk market. Dakawa has fertile soil for farming, and the Wami River is used to irrigate rice. Dakawa is home to large commercial farms, including the 2,000 ha Dakawa Rice Farm (Mdee et al., Citation2014) and commercial ranches (e.g. the Catholic-owned TEC Dakawa and the Shamba Kubwa ranch). The pastoral communities within Dakawa are transhumant Maasais.

2.4. Methods for data collection and analysis

Data were collected using qualitative and quantitative methods and direct observation. To understand the evolution and practices of the traders in milk marketing in Dakawa, we used three waves of data; collected in 2018, 2020, and 2023. The initial quantitative study was conducted in 2018; as well as the household survey, we discovered innovative business practices and were curious to understand how they worked. This led to a second step of the study, where a total of 17 qualitative interviews was conducted in 2020 across four months (May-August). First, in-depth key informant interviews were organised to understand the history and changes in pastoralists’ milk marketing in Dakawa. Key informant interviews were conducted with all the traders/cooling centres (5) in Dakawa, motorbike milk aggregators (4) who aggregated milk from households and pastoralists (7), and the local government representative. The questions for motorbike milk aggregators were based on everyday activities on milk sourcing, including milk quality tests, aggregation, and transportation. The questions for milk traders focused on how they navigated seasonal variability and variability in milk prices and volumes to ensure a steady flow of milk from production to the end market.

Second, trade practices were observed across the five milk cooling centres. All operational cooling centres were interviewed at the time of this study; the total number of cooling centres was five. In addition, employees of the two lead-firm-operated cooling centres that were in operation before this study and failed were also interviewed. Observations were also made to understand the practices concerning milk collection, cooling, and bulking, as well as interactions with other traders, motorbike milk aggregators, and pastoralists. The observations made here deepened and expanded the data collected during qualitative interviews. Key informant interviews with pastoralists, both men and women, were held independently to assess their responsiveness to the milk-sourcing strategies employed. In addition to this, a focus group discussion with men from the district was arranged to gain an understanding of the changes in the practice of milk production and milk marketing.

To assess the effectiveness of the trade practices over time, a rapid assessment of the business practices was done in April 2023 by revisiting the cooling centres interviewed in 2020. The aim of the rapid assessment was to evaluate if the traders were still in operation and whether there were any changes in their business practices. The team was also keen to understand if there were any new cooling centres in the area. Motorbike milk aggregators were also interviewed to see if their practices in milk collection and aggregation had changed.

While the qualitative analysis forms the bulk of our findings, we use the household survey data to describe the distinctions between households that sold milk and those that did not. The household survey was conducted under the IFAD-funded project entitled “Greening Livestock: Incentive-based Interventions for Reducing the Climate Impact of Livestock in East Africa”. The research was implemented in Rungwe, Mufindi, Njombe, and Mvomero districts. However, the data used in this manuscript is based on data collected in the Mvomero district only. The survey followed a representative, random sampling strategy using a two-stage sampling approach. In the first stage, biophysical clusters were developed to ensure that variability in production systems was sufficiently captured and accounted for. In the second stage, respondents from villages that represented each of the biophysical cluster were randomly selected. With the assistance of village elders in the chosen villages, a sample frame was created that included all households with an adult cow giving milk or an in-calf heifer. Using Yamane (Citation1967) formula,Footnote1 used when the population is known we estimated the sample size for each district. In Mvomero, 240 households were surveyed (See, Kihoro et al., Citation2021). Out of the 240 households 76 were pastoralists. Because the case study for this manuscript is Dakawa Ward, only pastoralists from this ward (n = 62) were retained for the subsequent analysis.

The survey instrument captured data on producers’ demographic characteristics, their practices, breeds, and if and where they sell milk. A richer analysis of the survey has been published elsewhere (See, Kihoro et al., Citation2021), but here, the household survey data is used to show the proportion of pastoralists selling milk and the main differences between pastoralists selling milk and those who are not, in terms of breed composition and income from dairy () shows the demographic characteristics of the pastoralists households interviewed.

Data from the qualitative interviews were transcribed and translated from Kiswahili to English. All the audio interviews with a length of 892 minutes were transcribed into text documents using Atlas-ti 8. A thematic analysis was used based on both inductive and deductive coding. From the coding exercise, 78 codes and 8,746 quotations emerged. The output was synthesised into the three broad themes as noted above: (i) Businesses navigating, (ii) The practice of alignment between traders and producers, and (iii) Mapping the responsiveness of pastoralists to the current milk business practices (See below).

Table 1. Analytical framework indicating the dimensions and codes used in data analysis.

The presentation of results is organised according to the analytical framework presented above. We start by providing a chronology of milk-sourcing strategies in Dakawa. This is followed by the presentation of the case of alignment between producers and traders by tracing motorbike milk aggregators’ practices for sourcing milk and traders’ practices for navigating the milk markets. Finally, the responsiveness of the Maasai towards the sourcing strategies is mapped. The discussion section synthesises these three aspects to highlight how traders’ and motorbike milk aggregators’ skilful performance of improvised business practices has developed an innovative endogenous commercial dairy system built upon the realities of pastoral milk production. The discussion ends by outlining the implications of this analysis for inclusive rural development.

3. Results

This section provides a chronological sequence of instructive milk-sourcing events and highlights aspects that caused previous milk-collection practices by “lead firms” to fail. We then provide a descriptive account of independent traders’ milk-sourcing practices that align with pastoralist production practices. Here we focus on how traders coordinate across time and space, how they navigate seasonal variability in milk volumes and prices, and how they coordinate with motorbike milk aggregators in milk collection and timely payments to producers. Finally, the results section explores the responsiveness of pastoralists to new market arrangements in terms of gender roles and changes in production practices.

3.1. The practice of milk collection by lead firms

The first processor to set up a cooling centre in Dakawa was a lead firm in 2007. The lead firm sourced milk directly from pastoralists without involving intermediaries. The establishment of the collection centre was a relief to many Maasai women who would otherwise carry the milk using traditional gourds, to sell either to their immediate neighbours or to urban consumers 45 km away in Morogoro town. During the wet season, and the lead firm would receive sufficient milk volumes. However, achieving adequate milk volumes during the dry season was difficult. This was because most pastoralists would move away in search of pasture, reducing the milk supply, which would lead to higher milk prices due to the constrained supply. In 2017, the company stopped operations in the region due to a lack of adequate milk volumes.

Our biggest challenge then was to ensure a constant milk supply to the factory. The factory does not regard whether it is wet or dry season, milk is supposed to be constantly supplied all the time. That was the most challenging task for me. Former Lead-firm employee 29/05/2020

A different lead firm also began collecting milk in Dakawa in 2011. The second lead firm applied an agent-based model where an individual was tasked to coordinate milk collection. The second lead firm catered for the operational costs of the cooling centre and paid the staff. This model worked for four years. Through their staff, the second lead firm sensitised Maasai women on the need to sell milk. Unlike the first lead firm, The second lead firm engaged milk motorbike milk aggregators in milk collection. At that time, the motorbike milk aggregators (intermediaries) only sourced milk for the second lead firm. However, from 2014 onwards, other independent traders opened cooling centres. As the number of other traders increased, two aspects affected the milk collection. First, during the dry season, the second lead firm cooling centre was not aggregating enough milk due to higher competition. Second, higher milk prices made it difficult for the second lead firm to compete with independent traders.

Milk collection centres started increasing. During that time, other cooling centres emerged. Milk traders increased drastically. This led to price fluctuations. The traders came with high prices and increased competition. Former lead firm. employee 28 June 2020

With additional traders sourcing milk from the area and the seasonal fluctuations in milk volumes and prices, the second lead firm was unable to secure a consistent flow of milk, especially during the dry season, and the cooling centre closed in 2015.

3.2. The practice of milk collection by independent traders

From all the existing cooling centre one was owned by an institution, they produced their milk, cooled it, and distributed it to its own branches. The remaining four were traders and were all in operation in 2020 and after the revisit study in 2023. Three new traders had also opened new cooling centres in 2023 demonstrating effectiveness and expansion. The subsequent sections are based on the four traders extensively studies in 2020.

The process of market navigation was done differently by a network of traders who sought to align with pastoralists’ production needs. In the following section, we highlight everyday practices through which the relation of milk producers (Maasai women), milk collectors (motorbike milk aggregators) and traders (cooling centre owners) results in a selection of processes that leads to an alignment of milk producers and traders’ goals. The results are presented according to three sub-themes: (i) traders navigating the milk markets by adapting to pastoralists’ movement strategies and navigating milk volumes and price variability across seasons; (ii) tracing motorbike milk aggregators’ practices in sourcing milk, including organising milk collection, quality control, and bulking, and (iii) coordination across time and space.

3.2.1. Traders navigating the milk markets

Traders in this study were independent investors who aggregate, chill and sell milk to external buyers (e.g. retailers). Traders own milk cooling equipment, and they aggregate between 500 and 4,000 litres of milk per day. All the traders were individual Swahili (non-Maasai) intermediaries – according to the Maasai culture, Maasai men do not engage in the milk trade. Traders require initial capital to buy cooling tanks (1,500–5,000 L cooling capacity) and enough money to pay producers and staff. The traders also navigated the seasonal variability affecting milk volumes and prices in Dakawa to deliver milk to retailers and consumers in Morogoro (47 km from Dakawa) or Dar es Salaam (185 km from Dakawa). All the traders and employees working at the cooling centres had a career history in milk collection. As such, the cooling centres were operated by people who already understood the contextual dynamics of milk production and marketing. The individual ownership of cooling centres, as opposed to the more complex ownership and management structures of processor companies, provided a relevant distinction in terms of companies’ ability to engage in new business models.

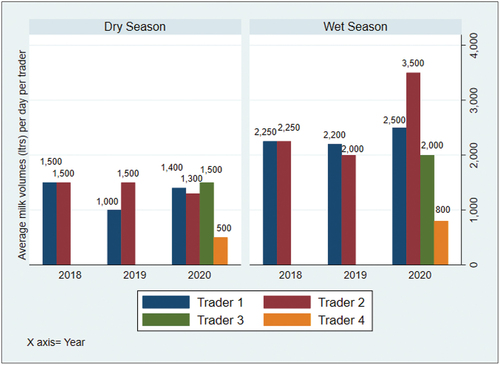

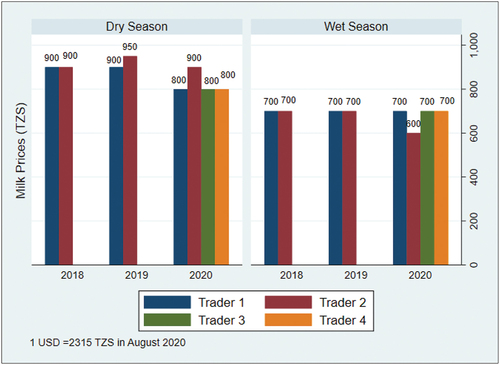

During the dry season (July, August and September), milk volumes decreased across all collection centres (see ) because of reduced feed availability. Therefore, pastoralists, motorbike milk aggregators and traders navigated variability in volumes across seasons. All traders received an average of 1,000 L less milk per day in the dry season compared to the wet season. Milk traders addressed this challenge by selling a higher proportion of milk to retailers in urban markets in Morogoro and Dar es Salaam because they purchased milk at a higher price per litre (1,000–1,200TZS). During the wet season, a higher proportion of milk was sold to private processing companies because volumes were higher, and prices were lower (700–800TZS) (see ). In Dakawa, only smaller processors specialised in value-added products, such as yoghurt and collected milk at a higher price (800–1,000TZS.

Figure 1. Average milk collections across the season and cooling centres.

Figure 2. Prices of milk across seasons and cooling centres.

In 2020, the dry season milk prices were lower than in previous years (). This was due to reduced milk consumption, attributed to COVID-19 disruption in milk transportation to urban markets like Dar es Salaam.

3.2.1.1. Coordination between traders

The level of competition and collaboration between traders varied depending on the need and season. Traders used price setting and reliability in milk payment as a strategy to attract motorbike milk aggregators. Price setting was done by word of mouth, and it changed in response to seasonal variability and milk volumes. During the dry season, traders who offered the most competitive prices received higher milk volumes. Prompt milk payment was also pivotal in getting a consistent milk supply and new referrals. Traders who paid on time gained loyalty from motorbike milk aggregators and consequently the pastoralists who supplied milk to the motorbike milk aggregators.

There are two stages involved in price setting. Motorbike milk aggregators – respond to a communication from individual pastoralists – lobby collection centres to increase milk prices. This change is based on the onset of dry and wet seasons. Suppose the price at the collection centre has increased to 800 TZS, the motorbike milk aggregator would inform the Maasai women supplying them with milk. FGD respondent 29/05/2020.

Traders also collaborated for convenience. For example, if a trader had a large order that they were not able to fulfil, they could request additional milk from their peers. Also, in case of equipment malfunction (e.g. cooling facilities), they could request other traders to chill milk on their behalf at a small cost. This collaboration was a way of navigating market-related risks.

3.2.2. Tracing motorbike milk aggregators’ practices in sourcing milk

The network of traders cannot exist without the network of motorbike milk aggregators. They aggregate milk from Maasai households and deliver it to cooling centres. Motorbikes were the preferred mode of transport due to their versatility in poor infrastructure and low fuel consumption. Young (male) motorbike milk aggregators (20–25 years old) identified several pastoralists’ households from whom they collected milk. The initial engagement was done through referrals from other pastoralists or motorbike milk aggregators. The relationship between motorbike milk aggregators and pastoralist women was based on the trust established through reliable and prompt milk payments and accurate milk volume capture. There was no formal agreement or contract between the motorbike milk aggregators and pastoralist households supplying milk. Milk collection was made between 6.00 and 9.00 am. The early morning was preferred because temperatures were lower (which reduces the risk of milk spoilage), and the women could milk the cows before they were taken out for grazing. In each household, the motorbike milk aggregators performed a milk quality test using a lactometer and an alcohol test, and they recorded the milk volumes using a measuring cup. The milk was aggregated in 100 litre aluminium cans or several 20 litre plastic cans for transportation to the cooling centre. Motorbike milk aggregators collected an average of 100–220 L per day.

Once the milk was aggregated from several households, it was either delivered to one of the cooling/trading centres or divided among two or three centres. Motorbike milk aggregators delivered milk to multiple cooling centres to maintain diverse commercial networks and guard against market risks. The motorbike milk aggregators did not have any contractual agreements with the cooling centres, and trade was done based on trust. The motorbike milk aggregators got a markup per litre of milk transported. On average, the markup was between 100 and 200 TZS per litre of milk, depending on the distance covered and season. Cooling centres paid motorbike milk aggregators, who, in turn, paid the Maasai women at their homes. This strategy was preferred by the Maasai women over the previous processor-based model, where women were required to collect their payments from the cooling centres. Some cooling centres paid the motorbike milk aggregators daily, who in turn paid farmers daily. Others paid after ten days, and others after two weeks. However, most centres had a diverse range of payment strategies depending on the pastoralists’ needs. In case a household had an emergency and needed money before the agreed period, the cooling centres advanced the motorbike aggregators the money, who would, in turn, pay the pastoral households on behalf of the cooling centres.

We are paid after ten days; however, it goes up to 15 or 16 days. In case the payments are delayed until the food is finished, one can ask for advance payment. Also, if I need money for the hospital, suppose my child is sick, they can give me money before the payment date. However, the advance can only be cash equivalent to half the milk I have delivered at the point of request. A woman pastoralist in Dakawa 5/06/2020

The practice of motorbike milk aggregators aggregating milk from individual households made it more attractive for pastoralists to sell milk. This was because the women no longer needed to travel long distances in search of milk buyers. In addition, the flexibility in terms of payment methods and the ability for the producers to get advance payments in case of emergencies marked the relationship between traders and producers more interactive. The motorbike milk aggregators’ flexibility in choosing which cooling centres to deliver milk to cushioned them against market shocks (e.g. milk spoilage from one cooling centre resulting in losses or delayed payments from traders). The revisit study in 2023 showed that during the wet season when milk volumes are high, the motorbike milk aggregators sub-contracted other independent riders to support in milk aggregation.

3.2.3. Coordination across time and space

Milk trading involved several tasks performed by different people across seasons and locations. During the dry season, pastoralists moved their cattle from Dakawa to Dumila (50 km from Dakawa) and other neighbouring areas, such as Mgudeni (30 km from Dakawa). During the wet season, most of the cattle grazed near Dakawa; hence milk was collected and transported to cooling centres in Dakawa (See ). However, in the dry season, most cattle were moved to Dumila and other areas. Two traders had established additional collection and cooling centres in Dumila to boost dry season milk collection in Dumila and its surrounding environments. Therefore, during the dry season, cooling centres in both locations were operational. The two towns were linked with a good quality tarmac road, so traders could transport milk between the two centres at minimal transport cost.

Figure 3. Panel a= shows Dakawa ward and Dumila ward where cattle migrate during dry season. b= shows the location of dakawa within Tanzania and c= shows the various milk cooling centres in Dakawa ward.

The pastoralists coordinated with motorbike milk aggregators to notify them about their movement patterns. Approximately 40% of the motorbike milk aggregators were Maasai men, so they were aware of the pastoralist movement patterns. Usually, they would move with their households (lower living costs) and collect milk from their households and other households around them. The motorbike milk aggregators who were not Maasai relied on communication with the households from whom they collected milk and could not travel far (more than 30 km) from their households to avoid incurring higher living and transport costs. When motorbike milk aggregators did not see the economic value of moving with pastoralist households, they dropped out of the milk business until the wet season, when the households returned to Dakawa Ward. Under such circumstances, motorbike milk aggregators coordinated and notified each other which households were covered to avoid overcrowding one area.

Pastoralists inform me that they will shift to other areas at a certain time. So, it is my duty now to see whether I can manage to collect from where they moved to otherwise, I must wait until the wet season. Because sometimes they move far from Dakawa, and the road network is poor. – Motorbike milk aggregator 06/07/2020

There was a high level of coordination between motorbike milk aggregators and traders to ensure that the required milk volumes were obtained. Take, for instance, Trader 1 noted, “I receive calls from buyers the previous evening notifying me of the volumes needed. I then call my motorbike milk aggregators to request specific milk volumes from each according to my order”. The advanced communication helped the motorbike milk aggregators to know where they would be delivering milk in the morning. Therefore, the day-to-day practices of sourcing milk were based on spontaneous problem-solving and improvisation embedded in the community and geography.

All the traders cited trust as the main component facilitating the milk transactions between pastoralists and motorbike milk aggregators and between aggregators and traders. Therefore, the aggregators established a milk supply network – cultivated through prompt payments, responsiveness to the pastoralist needs, and accuracy in milk payment. One trader noted that trust, effective communication, understanding people’s problems, and the ability to solve problems were the main pillars of their business. Trust was also leveraged as a basis of competition.

I started selling milk to a Swahili motorbike milk aggregator. He ran away with my money. Later I got engaged with another Swahili motorbike milk aggregator who is trustworthy and up-to-date. I have only one motorbike milk aggregator currently, and I or any of my friends can never sell to those who previously ran away. A woman pastoralist in Dakawa 5/06/2020

Traders who did not honour their word in terms of adhering to the set milk prices or milk payment timelines did not receive milk from the motorbike milk aggregators. Similarly, motorbike milk aggregators who delayed pastoralists’ payments did not get milk. Alignment was constructed in business practice constituting improvisation and flexibility as things unfolded. Central to their success was building on the motorbike milk aggregators’ network and innovative navigation of milk sourcing and selling across seasons.

3.3. Responsiveness of pastoralists

Alignment was not a simple fix and required a transformation both from the traders’ and pastoralists’ practices. We specifically analysed how pastoralist communities were changing in response to the new model of commercial dairying. The change was highlighted based on three aspects: gender roles, new livelihood opportunities and production practices. According to the Maasai culture, men own the cattle, and the milk was managed by women. Women noted that the Maasai men in Dakawa were now more appreciative of milk selling upon seeing the benefits of milk sales. Previously, men prohibited women from selling milk, and they preferred the milk to be used either for home consumption or left for calves.

Sometimes husbands restricted selling milk and insisted on reserving milk from the cows for calves. The man is the main decision-maker in the household. Only the man can allow you to access the household. But the business will be conducted by a woman. Male FGD respondent 29/05/2020

Although gender roles in the Maasai community were still clear-cut, women were tasked with milking and selling milk, while the men were responsible for the general welfare of the cattle. Women noted that the milk business enabled them to invest and help with the provision of money to cater for some basic household needs, e.g. food and paying school fees as well as animal health-related costs. Previously, men would have to sell a goat to cater for animal health and other household expenses, but now this can be catered for using the revenues from milk. “The man must sell a goat to get money. He can only earn 50,000 TZS if selling a goat, while a woman in ten days has 900,000 TZS from milk sales. This could change the culture”. Trader 28 June 2020.

Another changing gender role was the involvement of young Maasai men in the transportation of milk, which had previously been the domain of non-Maasai men. The young men aggregated and transported milk from their households and from other nearby households to traders. This represented a new opportunity for livelihood diversification. The involvement of Maasai men was a crucial element of the new business model, especially during the dry season. Because they were socially and culturally embedded, they could effectively connect producers and traders, blending the skilful management of pastoralist movement practices and markets. On the other hand, inclusion for young men depends on one’s socio-capital, both in terms of having a linkage with the traders as well as the ability to attract trust among Maasai women selling milk. They also require access to a motorbike – either hired or personally owned – was crucial. This entails access to starting capital which might be prohibitive to the average young person in the community.

3.3.1. Differences between households selling milk and those not selling

Traders created a technical, cultural fit that had implications on how herds were managed. below shows the demographic characteristics of the pastoralists in Dakawa. On average, the household heads were 43 years owning an average of 52 heads of cattle, of which an average of 19 were female cows. The average milk production per household in the dry season was 8.99 litres, while in the wet season, it was 13.66 litres. The average annual revenue from dairy per household was 2,248,500 TZS, while the average yearly household revenue was 5,330,863 TZS.

Table 2. Demographic statistics of the pastoralist households.

shows the differences in households selling milk and those not selling milk. On average, 50% of the households interviewed sold milk. There was no significant difference between households selling milk and those not selling milk in terms of herd size and amount of land owned. However, 45% of the households selling milk kept a crossbreed cow, compared to only 13 % among households that did not sell milk, with a statistical difference at p < 0.00. Their average milk production was statistically different t(60) = t −2.53, p < 0.05, with households selling milk averaging at (19.05 L/day) during the wet season compared to non-selling households (8.27 L/day). Households selling milk had an average of 2,248,500 TZS from milk annually, while the households that were not selling milk had zero income from dairy. Additionally, households selling milk had significantly higher revenues from livestock (this includes livestock sales and income from dairy) as compared to those not selling milk. This can be attributed to higher socio-network, which would translate to access to better prices from livestock sales. The overall household revenue for households selling milk was also higher compared to those not selling milk.

Table 3. Differences in demographics for pastoralists selling milk and those not selling milk.

Over time, households saw the benefit of having a few crossbred cows to enhance milk production. The households taking up crossbreds often crossed the local Zebu with Ayrshire. Ayrshire was preferred for its higher milk production and its relative adaptability to heat and disease stress. However, pastoralists kept large herds of cattle in line with their cultural customs. Respondents noted, however, that keeping many exotic dairy cattle required additional land for grazing because crossbred cattle need high feed inputs to produce high milk outputs, and they were not admirably adapted to mobility. However, expanding grazing lands was out of reach for most pastoralists because private land acquisition was capital-intensive and unaffordable to most. This denotes existing structural constraints hindering milk commercialisation within pastoral systems.

4. Discussion

This study analysed the agency of business actors in creating viable market links with pastoralists. The results highlight why marketing strategies used by lead firms failed and what enabled networks of independent traders to succeed in engaging transhumant pastoralist households in commercial milk marketing. We define this as alignment capacity, building on the work by (Beer et al., Citation2005; Vellema et al., Citation2020). Alignment capacity, as a term borrowed from business literature, is defined as the “alignment of organisational capabilities with competitive strategies in the constantly changing circumstances of the business environment” (Vellema et al., Citation2020, p. 716). To achieve alignment capacity, business practices, and performance need to align with producers’ practices within their specific socio and agroecological context. Literature on alignment specifies two types of alignment: internal within the business and external, denoting the business environment (Beer et al., Citation2005). Both types of alignment were present in the practice of milk trading, as described in the previous section.

Internal alignment denotes how economic actors modify their businesses and include new practices and decision-making structures (Beer et al., Citation2005). The case study demonstrated that traders mobilised certain skills for sourcing milk from pastoralists: this included the ability to co-create terms of inclusion that fit pastoralists’ logic; the everyday decisions made by traders to solve everyday problems; for instance, the decision taken by traders to overcome changing milk volumes and milk prices by changing milk buyers across seasons, constant communication with intermediaries; flexible payment of pastoralists and the use of unwritten norms and processes that become institutionalised to form an inclusive economic engagement for transhumant pastoralists.

External alignment is based on how the lead agent associates with the interests of less powerful actors (Vellema et al., Citation2020). Our study demonstrates how traders work with motorbike milk aggregators to solve challenges associated with milk bulking and seasonality. This was achieved by understanding the institutional process that supports rule-setting to facilitate alignment between traders, intermediaries, and pastoralists, and processes of self-reinforcement for the viable institutions that support business practices in sourcing milk.

4.1. What enabled the construction of alignment capacity?

Our results show two characteristics of internal alignment used by independent traders. These are; (i) the use of different milk buyers across seasons and (ii) competition and collaboration strategies among traders. Alignment was enabled by traders managing different milk buyers across seasons to smooth over fluctuations in volumes and prices. During the dry season, traders sold milk to retailers in urban centres, who required lower volumes and could pay higher prices. Proceeds from the sales were passed down to producers in terms of a higher milk price during the dry season. This was beneficial for pastoralists who incurred higher costs while sourcing feed and water during the dry season. This underscores the need for businesses to distribute economic costs and benefits equitably among the various actors within the chain (Schaltegger et al., Citation2016). Consequently, linking pastoralists to milk markets means traders need to align business practices with pastoralists’ needs, including their modes of production (Nori, Citation2019), seasonality, and high mobility (Simula et al., Citation2021), incurring high transaction costs in sourcing milk.

Traders employed a mix of competition and collaboration strategies. Traders used higher buying prices to attract higher milk volumes, employed as a competitive strategy. However, traders also collaborated in supporting each other in case of a technical malfunction from the cooling equipment or in case they needed to supply large milk quantities. This sort of reciprocal collaboration between competing traders helped to reduce losses and maintain the overall viability of the local dairy sector. Not only have these innovative strategies been institutionalised and professionalised over a few years, but they were also picked up by an increasing number of new traders, indicating their effectiveness. Our revisit study in 2023 found three additional traders using the same approach as the previous ones demonstrating effectiveness and expansion. The coordination among traders shows that business practices widen beyond individual practices and expand to the network of traders. The practices were flexible and adjust to changing circumstances. This aligns with previous work in Mali, which demonstrates how trading networks emerged as an outcome of the coordination of everyday practices among traders (Mangnus & Vellema, Citation2019). Such strategies are contrary to practices employed by lead firms that operate using competitive strategies with little coordination among lead firms in milk sourcing. This set of actions by traders shows how they react to challenges and opportunities as they arise (Glover, Citation2018).

The case study shows two external alignment strategies used by the traders, which include: (i) engagement of intermediaries and (ii) sequential coordination across time and space. The engagement of intermediaries – in this case, motorbike milk aggregators – in sourcing milk was beneficial in navigating seasonal variability and reduced milk volume during the dry season. Mainstream milk sourcing strategies are typically based on codified, top-down procedures, which do not always align with the local context, culture, or milk production systems (Aspers, Citation2007; Utting, Citation2015). Two lead firms tried and failed to organise milk sourcing in Dakawa, mainly because of their lack of flexibility to accommodate suppliers’ transhumance. Their sourcing strategies focused on excluding intermediaries and formalising relationships with suppliers (e.g. payments only at specified dates). This rigidity, while effective in other production contexts, precludes flexible practices that help align dairy processors’ business practices with pastoralists’ challenging everyday conditions. These results align with previous works (See Mair & Marti, Citation2009; Vellema et al., Citation2020; Zietsma & McKnight, Citation2009) that note that instead of relying on “institutional ideotypes” alone, it is also important to evaluate provisional institutions that are created and retained as a result of everyday problem-solving actions (Mangnus & Vellema, Citation2019).

Alignment requires sequential coordination between intermediaries and traders. Our analysis of subsequent innovative business practices by smaller-scale entrepreneurs shows that alignment was enabled by the skilful performance of distinct roles in a coordinated manner to facilitate milk sourcing. This includes motorbike milk aggregators navigating milk sourcing across space. The enabling factor for motorbike milk aggregators was either their experience in milk collection and understanding of the local terrain or their embeddedness in the production system. The Maasai motorbike milk aggregators move with the wider pastoralist community; hence they understand the routes followed each season and were embedded in the production systems’ practices and networks. Motorbike milk aggregators also have flexible arrangements, meaning they can supply several traders with milk. This flexibility cushions them from market fluctuations and risks. For instance, if one trader wants lower volumes on a given day, the motorbike milk aggregators can sell excess milk to another trader. Coordination is not institutionalised, and traders depend on personal arrangements with motorbike milk aggregators. In the absence of formal contracts, trust and prompt communication play a key role in facilitating trade (Roba et al., Citation2017).

While the latter is true, we acknowledge how other external factors (e.g. the availability of motorbikes as an alternative transportation method and their increased use in rural areas)were contributing factors enabling successful milk aggregation practices. This aligns with previous findings about upgrading rural footpaths to make them motorcycle-accessible promoted market integration (Jenkins et al., Citation2020).

4.2. Responsiveness of pastoralists to alignment capacity

As pastoralists become more integrated into commercial milk markets, their production practices were changing, including the integration of exotic dairy breeds to increase milk productivity. However, they prefer crossbreeds between the local Zebu and exotic Ayrshire for their combination of adaptability to harsh conditions and increased milk production. Recent research shows that pastoralists have consciously engaged in shifting breed preferences to match their livelihood and production system with a changing landscape (Krätli & Provenza, Citation2021; Scoones et al., Citation2020). Their objective is not to optimise milk production under tightly controlled conditions but to maintain resilient milk production under the complex and dynamic socio-economic landscape and environmental conditions (Krätli, Citation2019; Krätli & Provenza, Citation2021; Krätli & Schareika, Citation2010). As such, this flexible market integration allows pastoral households to maintain their livelihood strategy of (limited) transhumance while simultaneously engaging in cultural and technical changes related to emerging market opportunities and their practical knowledge in breed improvement. This provides pastoralists with options for building on their specialisation and expertise in mobility-based production systems rather than disrupting them through sedentarisation and rigid terms of market engagement.

While our results show the characteristics of households selling milk and those not selling, our focus on a specific case study – to assess the practices of an innovative business in including pastoralists to milk markets – was not geared towards assessing the long-term effects of commercialisation to pastoralists households and their community. We, therefore, recommend that future research focus on the effects of this innovative model. First, an in-depth understanding of the young people involved in milk aggregation in terms of the factors that enable their engagement, challenges faced, and the potential economic and social gains. These arrangements may attract other people looking for income opportunities and may relate to employment and small-scale business opportunity. In addition, a follow-up household survey to unpack the long-term effects of milk marketing for the pastoralists and household level dynamics in gender roles, e.g. shifts in power dynamics and women’s decision-making on milk revenues as milk becomes more commercialised is essential.

5. Conclusion

This study assessed an innovative business practice that engages transhumant pastoralist households in commercial milk marketing, which pushes against conventional wisdom in dairy development throughout Africa. Results show how the failures of rigid business approaches that do not accommodate “non-market” aspects important in the functioning of a market system have paved the way for innovative strategies. A deep dive into trader’s practices helps us understand business agency in, including pastoralists, not by a single isolated activity but as an emergent outcome resulting from a series of practices. When rural development interventions are responsive to socio-cultural structures within which economic activities are embedded, they are more responsive to local needs and stand a higher chance of success. These challenges government and practitioners to rethink the planning phase of development strategies and to adopt a more diagnostic angle to understand what works for who and in what conditions. Understanding endogenous production and business dynamics and building on existing socio-cultural conditions rather than using pre-conceived strategies lays a foundation for understanding the alignment capacity of traders and pastoralist producers. Instead of reshaping business in terms of how markets should function, this research encourages building on existing structures. In doing so, we demonstrate the importance of the private sector in contributing to sustainable rural development, providing business practice is done right. Explicitly targeting messy business practices as an entry point for development-oriented interventions, especially when they present opportunities to align with producers’ goals, would result in more inclusive rural development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) within the “Greening livestock: Incentive-Based Interventions for Reducing the Climate Impact of Livestock in East Africa” project [grant numbers 2000000994, 2016] implemented by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). This paper is part of the work conducted under the i-LED-project (“Multiple pathways and inclusive low emission development: navigating towards leverage points in the East-African dairy sector” - W 08.260.306), implemented by Wageningen University and Research (WUR) in collaboration with ILRI, CIFOR and the African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS). The authors acknowledge both financial and technical support from the 4th Global Challenges Programme (GCP 4) – a joint climate-smart agriculture scaling programme implemented in Eastern and Southern AFRICA with the support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) for East Africa, which is carried out with support from the CGIAR Trust Fund and through bilateral funding agreements. Todd Crane’s work on this article was supported by the CGIAR Initiative Livestock and Climate, which is supported by contributors to the CGIAR Trust Fund (https://www.cgiar.org/funders/). The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organisations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Where n = sample size, N = total (targeted) population, and e is the confidence level (5%).

References

- Anderson, D. (2010). Kenya’s cattle trade and the economies of empire, 1918–1948. In B. K, & G. D (Eds.), Healing the herds: Disease, livestock economies and the globalization of veterinary medicine (pp. 250–29). Ohio University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1j7x5hh.19

- Aspers, P. (2007). Theory, reality, and performativity in markets. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 66, 379–398.

- Barrett, C. B., Bellemare, M. F., Osterloh, S. M. (2004). Household-level livestock marketing behavior among northern Kenyan and southern Ethiopian pastoralists (no. WP 2005-11). Cornell University. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.716301

- Bee, F., Diyamett, M. L., & Towo, E. N. (2002). Challanges to traditional livelihoods and newly emerging employment patterns of pastoralist in Tanzania. Geneva: International Labour Organization. https://www.wiego.org/publications/challenges-traditional-livelihoods-and-newly-emerging-employment-patterns-pastoralists-

- Beer, M., Voelpel, S. C., Leibold, M., & Tekie, E. B. (2005). Strategic management as organizational learning: Developing fit and alignment through a disciplined process. Long Range Planning, 38, 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2005.04.008

- Davies, J., & Hatfield, R. (2007). The economics of mobile pastoralism: A global summary. Nomadic Peoples, 11, 91–116. https://doi.org/10.3167/np.2007.110106

- Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? The American Political Science Review, 98, 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404001182

- Glover, D. (2018). Farming as a performance: A conceptual and methodological contribution to the ecology of practices. Journal of Political Ecology, 25, 687–702. https://doi.org/10.2458/v25i1.22390

- Glover, D., Venot, J.-P., & Maat, H. (2017). On the movement of agricultural technologies: Packaging, unpacking and situated reconfiguration. In J. Sumberg (Ed.), Agronomy for development: The politics of knowledge in agricultural research (pp. 14–30). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Hallo Dabasso, B., Wasonga, O. V., Irungu, P., & Kaufmann, B. (2021). Emerging pastoralist practices for fulfilling market requirements under stratified cattle production systems in Kenya’s drylands. Animal Production Science, 61, 1224–1234. https://doi.org/10.1071/AN20042

- Hickey, S., & Toit, A. (2013). Adverse incorporation, social exclusion, and chronic poverty. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 81, 1, 134–135. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1752967

- Jenkins, J., Peters, K., & Richards, P. (2020). At the end of the feeder road: Upgrading rural footpaths to motorcycle taxi-accessible tracks in Liberia. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 92, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2020.100333

- Katjiuongua, H., & Nelgen, S. (2014). Tanzania smallholder dairy value chain development: Situation analysis and trends ILRI project report. Nairobi, Kenya: International Livestock Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/68513

- Kihoro, E. M., Schoneveld, G. C., & Crane, T. A. (2021). Pathways toward inclusive low-emission dairy development in Tanzania: Producer heterogeneity and implications for intervention design. Agricultural Systems, 190, 103073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103073

- Krätli, S. (2019). Pastoral development orientation framework: Focus on Ethiopia. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31890.40641

- Krätli, S., & Provenza, F. (2021). Crossbreeding or not crossbreeding? That is not the question. Pastres: Pastoralism Uncertainity and Resilience. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.15349.50405

- Krätli, S., & Schareika, N. (2010). Living off uncertainty: The intelligent animal production of dryland pastoralists living off uncertainty. European Journal of Development Research, 22, 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.41

- Lemma, D. H., Mengistu, A., Kuma, T., & Kuma, B. (2018). Improving milk safety at farm-level in an intensive dairy production system: Relevance to smallholder dairy producers. Food Quality and Safety, 2, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyy009

- Leonard, A., Gabagambi, D. M., Batamuzi, E. K., Karimuribo, E. D., & Wambura, R. M. (2016). A milk marketing system for pastoralists of Kilosa district in Tanzania: Market access, opportunities and prospects. International Journal of Agricultural Marketing, 3(1), 90–96. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55474097

- Lunogelo, H., Makene, F., & Gray, H. (2020). Dairy processing in Tanzania prospects for SME inclusion. Innovations Inclusion Agro-Processing, 1–8.

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2009). Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 419–435.

- Makoni, N., Mwai, R., Redda, T., Van der Zijpp, A., & Van der Lee, J. (2014). White gold : Opportunities for dairy sector development collaboration in East Africa (no. CDI-14-006). Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen University and Research.

- Mangnus, E. (2019). How inclusive businesses can contribute to local food security. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 41, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.10.009

- Mangnus, E., & Vellema, S. (2019). Persistence and practice of trading networks a case study of the cereal trade in mali. Journal of Rural Studies, 69, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.05.002

- Mccabe, J. T., Leslie, P. W., & Deluca, L. (2010). Adopting cultivation to remain pastoralists: The diversification of Maasai livelihoods in Northern Tanzania. Human Ecology, 38, 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-010-9312-8

- Mdee, A., Mdee, C., Mdee, E., & Bahati, E. (2014). The politics of small- scale irrigation in Tanzania: Making sense of failed expectations (no. 107). 59.

- Mdoe, N., & Mnenwa, R. (2007). Study on options for pastoralists to secure their livelihoods. 59.

- Michael, S., Mbwambo, H., Mruttu, H., Dotto, M., Ndomba, C., da Silva, M., Makusaro, F., Nandonde, S., Crispin, J., Shapiro, B., Desta, S., Nigussie, A., & Gebru, G. (2018). Tanzania livestock master plan. International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi.

- Mung’ong’o, C., & Mwamfupe, D. (2003). Poverty and changing livelihoods of migrant Maasai pastoralists in Morogoro and Kilosa Districts, Tanzania i (no. Research report No. 03.5). Dar es Salaam.

- Nell, A. J., Schiere, H., & Bol, S. (2014). Quick scan dairy sector (pp. 1–71). Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs. https://edepot.wur.nl/334382

- Nicolini, D. (2011). Practice as the site of knowing: Insights from the field of telemedicine. Organization Science, 22, 602–620. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0556

- Noor, I. M., Guliye, A. Y., Tariq, M., & Bebe, B. O. (2013). Assessment of camel and camel milk marketing practices in an emerging peri-urban production system in Isiolo County, Kenya. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 3, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-7136-3-28

- Nori, M. (2019). Herding through uncertainties – principles and practices. Exploring the interfaces of pastoralists and uncertainty. Results from a literature review. (no. RSCAS 2019) (Vol. 69, pp. 1–50). European University Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/1814/64228

- Nyokabi, N. S., De Boer, I. J. M., Bijman, J., Bebe, B., Aguilar-Gallegos, N., Phelan, L., Lindahl, J., Bett, B., & Oosting, S. J. (2023). NJAS: Impact in agricultural and life sciences the role of power relationships, trust and social networks in shaping milk quality in Kenya. NJAS: Impact in Agricultural and Life Sciences, 95, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/27685241.2023.2194250

- Richards, P. (1993). Cultivation: Knowledge or performance? In M. Hobart (Ed.), An anthropological critique of development: The growth of ignorance (pp. 61–78). Routledge.

- Roba, G. M., Lelea, M. A., & Kaufmann, B. (2017). Manoeuvring through difficult terrain: How local traders link pastoralists to markets. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.05.016

- Rodrik, D. (2010). Diagnostics before prescription. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.3.33

- Sadler, K., Kerven, C., Calo, M., Manske, M., & Catley, A. (2009). Milk matters: A literature review of pastoralist nutrition and programming responses. Addis Ababa: Feinstein International Center, Tufts University and Save the Children. https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Milk-Matters-review.pdf

- Sadler, K., Kerven, C., Calo, M., Manske, M., & Catley, A. (2010). The fat and the lean: Review of production and use of milk by pastoralists 1. https://doi.org/10.3362/2041-7136.2010.016

- Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G., & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: Origins, present research, and future avenues. Organization & Environment, 29, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615599806

- Schoneveld, G. C. (2020). Sustainable business models for inclusive growth: Towards a conceptual foundation of inclusive business. Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 124062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124062

- Schoonhoven-Speijer, M., & Vellema, S. (2020). How institutions governing the economic middle in food provisioning are reinforced: The case of an agri-food cluster in northern Uganda. Journal of Rural Studies, 80, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.035

- Schouten, A. M., Vellema, S. R., & van Wijk, J. (2016). The diffusion of global sustainability standards: An ex-ante assessment of the institutional fit of the ASC-shrimp standard in Indonesia. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 56, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020160405

- Schouten, G., Vink, M., & Vellema, S. (2018). Institutional diagnostics for African food security: Approaches, methods and implications. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 84, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2017.11.002

- Scoones, I., Lind, J., Maru, N., Nori, M., Pappagallo, L., Shariff, T., Simula, G., Swift, J., Taye, M., Tsering, P., Swift, J., & Swift, J. (2020). Fifty years of research on pastoralism and development. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2020.111

- Simula, G., Bum, T., Farinella, D., Maru, N., Mohamed, S., Taye, M., & Tsering, P. (2021). COVID-19 and pastoralism: Reflections from three continents. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 48, 48–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1808969

- Sinja, J., Njoroge, L., Mbaya, H., Magara, H., Mwangi, E., Baltenweck, I., Romney, D., & Omore, A. (2006). Milk market access for smallholders: A case of informal milk trader groups in Kenya. In Research Workshop on Collective Action and Market Access for Smallholders, October 2–6, 2006, Cali, Colombia (pp. 1–15). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228464496_Milk_Market_Access_for_Smallholders_A_Case_of_Informal_Milk_Trader_groups_in_Kenya

- Sule, E., & Mkama, W. (2019). A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Tanzania’s Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts, Pwani region and Mvomero and Kilosa districts, Morogoro region. International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi.

- Tdb, T. D. B. (2018). Hali Halisi ya Uingizaji wa Maziwa maziwa toka nje na Mikakti ya Kupunguza uingizaji wa Maziwa. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Tanzania Dairy Board.

- The United Republic of Tanzania. (2004). The dairy industry ACT, 2004. Dar es Salaam.

- United Republic of Tanzania. (2010). Livestock sector development strategy. Dar es Salaam.

- The United Republic of Tanzania. (2015). Tanzania livestock modernisation initiative. Dar es Salaam. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Utting, P. (2015). Revisiting sustainable development. United Nations Research Institute fo Social Development.

- Vellema, S., Schouten, G., & Van Tulder, R. (2020). Partnering capacities for inclusive development in food provisioning. Development Policy Review, 38, 710–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12466

- Vellema, S., Ton, G., de Roo, N., & van Wijk, J. (2013). Value chains, partnerships and development: Using case studies to refine programme theories. Evaluation, 19, 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013493841

- Vernooij, V., Vellema, S. R., & Crane, T. A. (2023). Beyond the formal-informal dichotomy: Towards accommodating diverse milk-collection practices in the economic middle of Kenya’s dairy sector. The Journal of Development Studies, 59, 1337–1353.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Zietsma, C., & McKnight, B. (2009). Building the iron cage: Institutional creation work in the context of competing proto-institutions. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations (pp. 143–177). Cambridge University Press