Abstract

Whereas a great deal is known about lesbian/gay parent families, much less is known about bi+ mother families, especially relating to the ways bi+ mothers discuss their bisexuality+ with their children. This article explores conversations about bisexuality+ and queer socialization in bi+ mother families. Semi-structured interviews were conducted online with 29 bi+ mothers, with each interview lasting one to two hours. Mothers were asked about whether they had discussed their bisexuality+ with their child(ren), their reasoning for wanting to discuss their sexuality with their child(ren), how they broached the topic, whether they used any resources, and how the child(ren) reacted. Interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis, informed by prior literature on cultural socialization and disclosure. Analysis revealed that bi+ mothers adopted various strategies and approaches to discussing their bisexuality+ with their children, which were often child-focused and based on a consideration of children’s developmental abilities. Bi+ mothers also engaged in queer socialization practices, such as cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and mainstream queer socialization. The theoretical and empirical implications of this research are discussed, as well as the practical implications, such as providing support to bi+ mother families. Directions for future research are also identified.

Introduction

Parenting is commonplace among lesbian, gay, and bisexual people but evidence suggests that bisexual people are more likely than gay/lesbian individuals to become parents (Pew Research Center, Citation2013). In fact, the majority of LGB parents are bisexual (Goldberg et al., Citation2014) and bisexual women may be more likely than heterosexual women to have children (Herbenick et al., Citation2012). Although 59% of bisexual women are estimated to have children (Pew Research Center, Citation2013), most existing research has focused on the parenting experiences of gay/lesbian parents, ignoring those of bi+Footnote1 parents. Little is known about how bi+ mothers navigate their bisexuality+ within their own families. In this article we explore bi+ mothers’ experiences of discussing their bisexuality+ with their children.

Research on bi+ parents

Even though bisexual people comprise a slight majority within the LGBTQ community (Gates, Citation2011), bi+ people have been largely ignored in the LGBTQ literature (Bostwick & Dodge, Citation2019; Hartwell et al., Citation2017; Pollitt et al., Citation2018). In particular, little research has investigated bisexual parenting despite a growing body of research into LGBTQ parent families (Ross & Dobinson, Citation2013). A systematic literature search found that only seven studies reported findings specific to bisexual participants (Ross & Dobinson, Citation2013), of which two were case studies of bisexual fathers (Anders, Citation2005; Brand, Citation2001) and one investigated five bisexual parents’ expectations of their children’s sexual identities (Yang Costello, Citation1997). This is a significant research gap, given that bisexual people are more likely than gay/lesbian people to desire children (Gates et al., Citation2007) and bisexual parents constitute the largest segment of sexual minority parents, with approximately 64% of LGB parents being bisexual (Goldberg et al., Citation2014). Hence, there have been various calls for research that focuses on bisexual parents (e.g., Manley & Ross, Citation2020; Ross & Dobinson, Citation2013).

Disclosure in bi+ parent families

Monogamous bi+ people cannot be identified as bi+ from the gender-composition of their relationship and are often assumed to be heterosexual or gay/lesbian based on their partner’s gender (Dyar et al., Citation2014). For instance, bi+ women dating women are assumed to be lesbians, and bisexual individuals in mixed-gender relationships are read as heterosexual. This is called heterosexual passing (Arden, Citation1996). In parenthood, bisexual parents are often (mis)classified depending on their partner’s gender (Hartman-Linck, Citation2014; Ross & Dobinson, Citation2013), causing feelings of invisibility for bisexual mothers (Ross et al., Citation2012).

As bi+ people are rarely assumed to be bi+ their experiences of disclosure are discrete from those of gay/lesbian parents. Gay/lesbian parents’ sexualities are evident to children through their relationship gender composition, allowing children of gay and lesbian parents to make accurate assumptions about their parents’ sexualities (Tasker, Citation2005). This means that children of gay/lesbian parents generally come to understand their parents’ sexuality gradually, rather than through a specific conversation (Breshears, Citation2011; Tasker, Citation2005). Instead, children of gay/lesbian parents generally learned about their parents’ identities through everyday conversations (Breshears, Citation2011; Tasker, Citation2005).

As many bisexual parents’ sexualities are not visible or predictable based on the gender composition of their relationship (Haus, Citation2021), their children are unlikely to accurately predict their parents’ bisexual identities from their relationship. Instead, children of bisexual parents are likely to assume them to be heterosexual or gay, due to prevailing monosexist ideas within society which privilege monosexual identities (Haus, Citation2021), and because bisexual individuals in monogamous relationships are rarely recognized as bisexual (Hartman-Linck, Citation2014). This potential erasure for parents of their bisexual identity could potentially provide increased impetus for initiating conversations with their children. Bisexual parents experience a unique disclosure situation where they must continually evaluate whether they wish to come out to their children or would rather be mistaken for heterosexual or gay (Haus, Citation2021). In particular, bisexual parents in heterosexual-passing relationships have a unique choice of whether to disclose their sexuality and have more control over their coming out experience (Haus, Citation2021). Additionally, bisexual parents in different gender relationships who come out sacrifice their heterosexual-passing privilege, risking discrimination for themselves and their children (Haus, Citation2021).

To date, only two studies have explored bi+ parents’ decisions about coming out to their children. Bowling et al. (Citation2017) examined sexuality-related communication, such as sexual behaviors, protection from sexually transmitted infections, and unintended pregnancy, through interviews with 33 bisexual parents. Over half of these parents had come out as bisexual to their children, often to encourage children to be accepting. Bisexual parents reported taking their children to pride and reading them queer-friendly books, however parents in different-gender relationships were less likely to participate in these activities.

Haus (Citation2021) explored bisexual parents’ reasons for their plans (not) to come out to their children through an online survey of 767 US bisexual parents and found that significantly more bisexual parents (99%) in same-gender relationships planned to come out to their children than those (84%) in different-gender relationships. Parents in same-gender relationships were significantly more likely to be out to their children than parents in different-gender relationships. Bisexual parents who planned to come out provided reasons such as educating their children on diversity, encouraging children to be allies, combatting bierasure, promoting honesty, and conveying solidarity to their LGBTQ children. Some parents who did not plan to come out to their children believed that their sexuality was private, shameful, or too confusing. Other parents said they would come out to their children if they asked or if they were also queer.

The present study

Although Haus’ (Citation2021) study provided insight into the reasons bisexual parents gave for coming out to their children, namely why bisexual parents choose (not) to come out to their children, no research to date has explored how bisexual parents come out to their children. The present study thus investigated bi+ mothers’ experiences of talking to their children about (their) bisexuality+, using in-depth qualitative interviews. The study explored if, and how, bi+ mothers discuss bisexuality+ with their children, and if they engage in any broader queer socialization practices. It also investigated how bi+ mothers come out to their children, when they do so, and their considerations when making these decisions. By focusing exclusively on bi+ mothers, rather than grouping them under the LGBTQ umbrella, this study aimed to amplify the voices of bi+ mothers, to reduce bierasure within academia. Thus, this study acknowledged bi+ mothers’ unique experiences, rather than assuming that bi+ parents’ experiences are substantially equivalent to those of gay/lesbian parents.

The theoretical frameworks informing this study draw on theories of cultural socialization and disclosure practices. A cultural socialization framework, adapted from the racial socialization literature (for a review see Hughes et al., Citation2006), was used to examine bi+ mothers’ socialization practices regarding their bi+ identity. Cultural socialization refers to the ways parents transmit cultural values, information, and customs to their children (Lee, Citation2003; Oakley et al., Citation2017). This framework allows a systematic analysis of bi+ mothers’ socialization practices.

Previous research has applied this framework to explore the socialization practices of queer (primarily lesbian and gay) parents, on the basis that families with same-sex parents experience stigma so may engage in cultural socialization strategies relating to their orientations. The socialization practices of sexual minority parents, referred to as queer socialization by some researchers (e.g., Mendez, Citation2020), have been found to resemble racial socialization practices in their content and structure. Just as ethnic-minority parents engage in racial cultural socialization, teaching their children about their heritage and culture (Hughes et al., Citation2006), queer parents have been found to engage in queer cultural socialization, promoting awareness of, and celebrating, diverse family structures (e.g., Gianino et al., Citation2009; Gipson, Citation2008; Goldberg et al., Citation2016; Oakley et al., Citation2017). Additionally, in the same way that ethnic minority parents engage in preparation for bias, lesbian and gay parents prepare their children for potential stigma and teach them how to respond to discrimination (e.g., Gipson, Citation2008; Litovich & Langhout, Citation2004; Oakley et al., Citation2017). In addition, lesbian and gay parents have been found to engage in mainstream queer socialization, where they teach their children that their family is the same as other families (e.g., Breshears, Citation2011), or focus on emphasizing similarities between their family and other family types, to teach children that their family is “normal” (e.g., Goldberg et al., Citation2016), in the same way that ethnic-minority parents have been found to engage in mainstream socialization (Boykin & Toms, Citation1985; Spencer, Citation1983).

The study was also informed by research on disclosure processes, drawn primarily from samples of adoptive parents and parents who conceived using assisted reproductive technologies. Research on parents’ disclosure techniques, which convey information to children about family formation, demonstrates that parents typically use one of two strategies. The first, observed in studies of donor conception parents, is the “seed-planting” strategy (Mac Dougall et al., Citation2007; MacCallum & Keeley, Citation2012), which involves disclosing small age-appropriate pieces of information to the child over time, from an early age. This approach is based on the conviction that as the child would have “always known” the information about their conception, it would thus not become a “big deal” to the child.

The second strategy, “the right time” strategy (Mac Dougall et al., Citation2007), is based on a belief that there is an optimal time during a child’s development within which they will best receive information about their conception. Parents using this strategy conceptualized disclosure as a single event, in contrast to parents using the seed-planting approach, for whom disclosure involved incrementally revealing more details through many conversations. Many parents using the right time strategy believed that the right time would coincide with sex education discussions (Mac Dougall et al., Citation2007).

Materials and methods

Recruitment and sampling

Mothers were recruited through social media and snowball sampling. Twenty-nine bi+ mothers (M = 38.69 years, SD = 6.20, range = 27–51) were interviewed between February and April 2021. Bi+ mothers used a range of identity labels, including bi, bisexual, pansexual, and queer and discussed using multiple labels interchangeably, changing their preferred terms over time, and using different labels to describe their orientation depending on who they were speaking to. Over half of the participants (55%, n = 16) lived in the UK and most (62%, n = 18) were in a monogamous relationship with a man. Over two-thirds of mothers (69%, n = 20) identified with the term “female”, “woman”, or “cis-woman”, and 31% (n = 9) identified under the non-binary umbrella,Footnote2 as genderfluid, genderqueer, agender, or non-binary. Most (90%, n = 26) mothers reported that their ethnic background was White; the other mothers’ ethnic backgrounds are not included to maintain their anonymity as their responses would be too identifying. Mothers who were working and reported their annual income after taxes (n = 20), had an average income of £31,892 (SD = 30,040). For full demographic details see .

Table 1. Participant sociodemographic characteristics.

Mothers had an average of 1.69 children (SD = 0.76, range = 1–4). The mean age of the children was 9.32 years (SD = 5.41, range = 4 months–25 years). All mothers had at least one child under the age of 18 years. In total, the 29 mothers had 49 children, most of which (98%, n = 48) were carried by the bi+ mother themselves. One child (2%) was carried by a bi+ mother’s partner. Around half (53%, n = 26) of the children were conceived through unassisted conception with the participant’s current partner and 19 (39%) were conceived through unassisted conception with an ex-partner. Of the four (8%) children conceived with donor sperm, two were conceived within a same-gender relationship, one by a solo mother by choice, and one within the context of a relationship with a transgender man, using a secondary partner’s sperm.

Having spoken to their children about being bi+ was not part of the inclusion criteria for the study, meaning that not all of the bi+ mothers who participated in the study had explicitly discussed their bi+ identity with (all) their children. It is hard to quantify how many of the participants were “out” to their children, as there is not a simple dichotomy between “outness” and “being closeted”. For instance, whereas some parents explicitly labeled themselves as bi+ to their children, others had discussed bisexuality+ as a topic without using their identity label, and others had been in/were in relationships with people of different genders, making their bi+ identity evident without an explicit discussion. Additionally, some parents had discussed their bi+ identity with their older children but had not yet explicitly discussed their bi+ identity with their younger children, again blurring the distinction between “outness” and “being closeted”. The dichotomy is also complicated further by the fact that many mothers described “coming out” to their children as a process rather than a moment, again blurring the lines between “out” and “closeted” as some parents had begun discussing the topic with their children but the children had not fully grasped the concept yet. Although it is difficult to quantify how many of the children of the bi+ mothers in the study were aware that their mothers were bi+ at the time of the interview, the majority (90%) of mothers in the study had discussed their bi+ identity with at least one of their children to some extent, or at least one of their children was aware of their identity through seeing them date multiple people of different genders. Of the 10% of mothers (n = 3) who had not discussed their bi+ identity and whose children had not seen them date people of multiple genders, two had begun conversations about different family types or sexualities but were yet to discuss their own bi+ identities. The other mother had an extremely young baby so had not begun any conversations about sexuality or their own bi+ identity yet but discussed their plans to in the future. Hence, although not all of the 29 mothers had explicitly “come out” to every one of their children, all the mothers’ perspectives and experiences are represented in this paper to some extent, with some discussing future plans or more general conversations about bisexuality+ rather than specific conversations about their bisexuality+.

Data collection

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee. After gaining written informed consent, mothers were interviewed through the videoconferencing software Zoom, using a semi-structured interview. Each interview lasted 1 to 2 hours and all interviews were audio-recorded. Interviews included a range of topics including relationship history, experiences of bi-invisibility and heterosexual-passing, route to parenthood, experiences of transitioning to parenthood, experiences of parenting spaces, mental health, and disclosure of bisexuality+ in different spheres.

The main section of the interviews of relevance to the current research question was the “disclosure to children” section of the interview. This section began with the question “have you told your child(ren) that you are bi+?”, which aimed to spark discussion of, and capture mothers’ experiences of, talking about bisexuality+ with their children. Further questions regarding parental reasons for wanting to talk to their child about their orientation, their child’s understanding, and resources used were asked if not mentioned by mothers initially.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six stages, to identify themes relating to the disclosure experiences of bi+ mothers. Interview transcripts were read several times for familiarization. Extracts were then coded. The coding process was deductive and inductive, with extracts coded for their content, as well as using the previous literatures to inform codes. Coded extracts were re-read and codes were collapsed to produce themes. Themes were assessed for internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity and were refined to produce six themes. All stages of the analysis process were discussed by both members of the research team.

To ensure the quality of the research, Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) fifteen-step checklist of criteria for good thematic analysis was used to inform decisions throughout transcription, coding, analysis, and reporting the findings. A data audit (Flick, Citation2014) with a researcher experienced in qualitative methods and external to the research team was conducted, as an exercise in transparency and procedural clarity. This is one of the main methods for establishing the “confirmability” of qualitative results and ensuring that the findings are grounded in the data (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). During the data audit, the external researcher explored the coding of one transcript as well as examining the codes and data within each theme and subtheme to ensure the themes were discrete and coherent. The external researcher suggested changing the name of one sub-theme because she felt it might be too identifying as it used a quotation from a participant with a non-English kinship term.

Results

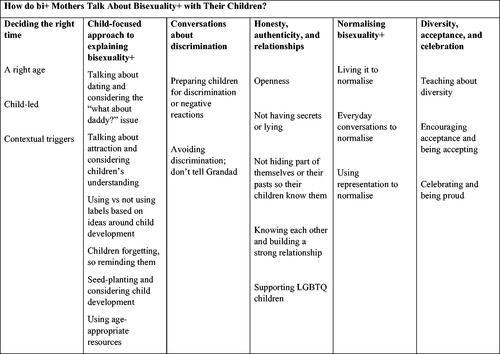

Mothers’ experiences of talking to their children about bisexuality+ can be understood in relation to six themes: “deciding the right time”, “child-focused approach to explaining bisexuality+”, “conversations about discrimination”, “honesty, authenticity, and relationships”, “normalizing bisexuality+”, and “diversity, acceptance, and celebration”. Themes and sub-themes can be seen in the thematic map (see ).

Figure 1. Thematic map depicting the 6 themes and 22 subthemes which describe how bi+ mothers discuss (their) bisexuality+ with their children.

Bi+ mothers described using a range of techniques to disclose their identities to their children. Bi+ mothers considered children’s needs, emotions, and developmental abilities when deciding when and how to talk with their children about their orientation. Mothers’ explanations of bisexuality+ were shaped by their consideration of their children’s abilities and were age-appropriate. Bi+ mothers’ core values, such as honesty and authenticity, shaped their discussions with their children regarding their own orientation, but also their broader parenting practices. Bi+ mothers engaged in various queer socialization practices, including queer cultural socialization, preparation for bias, and mainstream queer socialization.

Deciding the “right time”

Some mothers felt that there was a “right time” to discuss (their) bisexuality+ with their children. Mothers had different ideas about when the right time was, with some believing that there was a right age to discuss the topic, and others taking a more child-led approach. Sometimes the right time arrived due to contextual triggers either provoking or warranting a conversation.

A right age

Mothers who believed that there was a certain age when it was best to discuss bisexuality+ with their children, either for the first time, or in more detail, generally discussed two time-periods: early childhood and adolescence.

Some mothers believed that children should know as soon as possible and described wanting to “tackle these things early enough”. This parallels findings from the disclosure literature; research suggests that many parents who conceived with donor gametes held a conviction that early disclosure is of paramount importance so that the child “always knows” (e.g., Mac Dougall et al., Citation2007) and adoptive parents often wanted their children to know that they were adopted from an early age rather than finding out later (e.g., Alexander et al., Citation2004). In the current study, bi+ mothers felt that if children knew about their bisexuality+ from an early age it would be easier for them to accept it, with one mother saying, “if [children] get it from a young enough age, they’re like this is just part of who you are”.

Some bi+ mothers also described their children’s teenage years as a time for discussions of bisexuality+, as this is a time when broader conversations about sex, puberty, and bodies arise. This mirrors findings in lesbian mother families where adolescents’ increased awareness of sexuality invited a new wave of information sharing (Mitchell, Citation1998). For some bi+ mothers in the current study, the topic of sex education at school led to conversations about bisexuality; one parent explained that their child had come home from school and “told [them] what they learned [in sex education] and… I think it was probably around then [that the topic of bisexuality came up]”. Some parents who had already discussed their orientation mentioned adolescence as a time when the topic would come up again. Parents incorporated a discussion of bisexuality+/LGBTQ topics into naturally occurring conversations about sex and puberty. One mother explained “there’s a chapter in the [sex education] book we’re reading…about sexual orientation specifically and so we’re talking about different identities… and I was saying ‘I used to use this word and now I use this word [to describe myself]”.

Being child-led

In a similar way to how donor conception parents use children’s basic origin questions, such as “Where do babies come from?”, as a starting point for discussing donor-conception (Mac Dougall et al., Citation2007), in the current study some bi+ mothers used children’s questions as a prompt for discussing their orientation. Bi+ mothers felt that children’s questions indicated that it was the right time: “children will ask the questions when they’re ready to hear the answers”. Sometimes bi+ mothers used children’s broader questions about reproduction as an indication that it was the right time to begin conversations about bisexuality+, for example “(son) started asking about “how are babies made?” at about 5, so I think it was about the right time around that time”. Mothers taking a child-led approach wanted conversations to be at the child’s speed, saying that they wanted discussions to be “very much at their pace”. Although many mothers intended for conversations to be child-led, several believed that there was an age by which their orientation should be mentioned. One mother of a 4-year-old said, “if he didn’t [bring it up naturally], then I guess I would bring it up at some point maybe in the next few years”.

Contextual triggers

Corroborating the findings of Haus (Citation2021), who found that bi+ parents’ disclosure decisions were related to dating, in the current study some mothers’ ideas about the ‘right time’ centered around the practicalities of dating. Mothers often felt they needed to discuss their orientation with their child before bringing home someone of the same gender; one mother explained “I had to tell him because I was really attracted to this woman, and I really wanted to go on a date”. Mothers discussed wanting their children to find out in an “appropriate way” rather than for them to “come home with a girlfriend and it be a surprise”.

For other mothers in the present study, there was a more immediate trigger event. One mother explained that their child came back from school asking “Mum, is lesbian a bad word?”, which prompted the parent to discuss their sexuality with their child.

Child-focused approach

Just as adoptive parents match their explanations of adoption with the cognitive and emotional abilities of their child (e.g., Alexander et al., Citation2004), bi+ mothers in the present study took developmentally aware, child-focused approaches to explaining bisexuality+ to their children, creating age-appropriate explanations and considering children’s abilities and needs.

Talking about dating and considering the “what about daddy?” issue

Some parents’ explanations of their bisexuality+ focused on discussing dating. Single and polyamorous bi+ mothers spoke about who they might date in the future, to make evident and explain their bisexuality+, such as saying “mummy might want a girlfriend, or mummy might want a boyfriend”. Other mothers’ explanations focused on prior dating, usually because they had a current partner; for instance, telling children “I’ve gone out on dates with men and women”. Some mothers described intentionally bringing up same-gender ex-partners to make evident their bisexuality+. One mother said that they “very intentionally tr[ied] to tell stories about [their] [ex] girlfriend”, saying that they thought to themselves “what story could I tell about [ex-girlfriend] so that [child] knows that I am bisexual?”.

A subset of bi+ mothers felt worried about talking about ex-partners or future partners because they thought that it would be awkward for their current partner, or may cause their children distress if they discussed the possibility of their current relationship ending. This was most often the case for mothers in a relationship with their child(ren)’s father and is evident in the following quote:

“any discussion of me being bi, either means I have got to talk about exes, which is not comfortable for my current partner, or I have got to talk about him going somewhere because he has left or died, so I think that makes it difficult”.

Another mother explained, “I think because she has a mummy and a daddy it’s sort of difficult to explain to her… I don’t want her to get worried that I’m going to leave her daddy”. One mother who had discussed their bi+ orientation with their son said that he had asked “but do you love daddy?”. Some mothers specifically worded their explanations of bisexuality+ to avoid their children worrying about their parents’ relationship ending. One mother said “it’s ‘mummy could have married a boy or girl’, so that way they understand… it’s not something they need to worry about, I still love daddy and chose to marry him”.

Talking about attraction and considering children’s understanding

Other mothers’ explanations of their bisexuality+ centered around discussing attraction to multiple genders; some mothers explained to their children that “mummy likes men and women” or said, “I could be attracted to… people of all different genders”. These explanations were similar in structure to those used by gay and lesbian parents, with gay fathers explaining their orientation to their children by saying that they “liked men” (Bozett, Citation1980), and lesbian mothers explaining to their children that a lesbian is “a woman who loves another woman” (Mitchell, Citation1998). However, in the current study some mothers discussed how their child’s age limited their understanding of romantic love and attraction, which made explaining bisexuality+ this way difficult. One bi+ mother explained “he thinks all love is like how he loves me. He doesn’t understand about different types of [love] and therefore it’s very difficult to explain being gay or bi”.

Using vs not using labels

Some mothers’ explanations included using their identity label; one mother explained “I would just say that "people can fall in love with other people and that I and other bisexuals can fall in love with anybody, with somebody of any gender, not just a man or not just a woman”". In the same way that lesbian mothers have also been found to not always use identity labels when explaining their orientation to their children (Cohen & Kuvalanka, Citation2011; Mitchell, Citation1998), in the current study some bi+ mothers chose not to use their identity label with their children. One mother explained that “I’ve talked to her about the concept of bisexual, but I don’t think I have used those terms”. Often the decision to not use their identity label was based on a child-focused consideration of the child’s young age; “I just think it’s too big terms”.

Children forgetting, so reminding them

Bi+ mothers reflected upon the limitations of children’s memories and how this influenced conversations about their bisexuality+. Mothers mentioned that when they told children, they forgot soon after: “she forgets five minutes later”. Some parents recalled having to tell children multiple times and the children not remembering: “I remember telling him a couple of times when he was smaller, but… children’s memories sometimes are interesting. So, I’m not sure that he’d remembered specifically having that conversation”. This consideration of the limitation of children’s memories shaped some mothers’ strategies. For example, some mothers actively reminded their children; “I actually told them many years ago, and sometimes I remind [them about my bisexuality] because… they sometimes just forget”. For some mothers, a consideration of children’s memory limitations meant they had decided the child was too young to begin talking about the topic: “even if I bought it up now, he wouldn’t necessarily remember. I think I’d have to bring it up multiple times for it to be kind of something that’s imprinted in his knowledge”.

Seed-planting

Most mothers’ conversations about bisexuality+ with their children took the form of numerous small discussions over time, with several exceptions of mothers who discussed one conversation where they had come out to their children. One mother explained that “it has all been lots of little subtle things rather than one particular conversation”. Taking the approach of telling children slowly over time, through many conversations, was often linked to ideas around children’s abilities to understand, again showing how mothers considered children’s needs when formulating their approaches to discussing their orientation. Many who took this ‘seed-planting’ approach often taught their children about LGBTQ topics first, then revealed that they were bi+ themselves; “it’s me laying a foundation so they can understand… what bi means. And then [later adding] ‘by the way, mummy is bi’”. One mother explained that so far, they had only talked to their child about same-gender couples, without specifically explaining bisexuality+ because they believed their child “doesn’t have the capacity to sort of understand more than that yet”.

Using age-appropriate resources

Some mothers used age-appropriate resources when discussing their bisexuality+ with their children. One mother explained that she pointed out bisexual+ people in books when reading with her son: “we have these little feminist board books and if there’s somebody in them like there’s a page with Josephine Baker and I will say ‘oh Josephine Baker was bisexual just like mama’”. The book also included Frida Kahlo and she would point out to her son that Frida Kahlo was also bisexual like her. She clarified that the books did not state that Josephine Baker and Frida Kahlo were bisexual, but that she added this information when reading the books with her son. This creative use of books mirrors the behavior of lesbian parents, who have been found to use books creatively, such as using she/her pronouns for both parents (Ackbar, Citation2011).

Conversations about discrimination

In the same way that lesbian and gay parents discuss discrimination with their children (Bos & Gartrell, Citation2010; Gartrell et al., Citation1999; Gipson, Citation2008; Goldberg et al., Citation2016; Mendez, Citation2020; Oakley et al., Citation2017), a minority of bi+ mothers in the current study discussed having conversations about bisexuality+ with their children relating to discrimination in wider society.

Preparing children for discrimination or negative reactions

Some mothers warned their children about potential discrimination relating to their bi+ identity, which could be classified as the queer socialization practice of “preparation for bias” (Mendez, Citation2020). For example, one mother said that they had conversations with their child “preparing him for… the fact that he might meet some… negative reactions”. Mothers wanted to prepare children for when LGBTQ topics or their bisexuality+ were raised outside of the home: “[I] wanted to bring it up before it became a big deal at school… [so I] had a bit of control over the conversations”.

Avoiding discrimination; don’t tell grandad

Some mothers asked their children not to mention their orientation in front of, or to, specific family members, to prevent discrimination. For instance, one mother explained that “one of the things that we would tell [child] [was] we don’t talk about [my bisexuality+] in front of Grandad”. Despite asking children not to raise the topic in front of specific people, parents wanted to ensure that children knew this did not mean that there was anything wrong with bisexuality+. One mother told their child “that is Grandad’s problem, that’s nobody else’s problem”. The intention to protect children from people who are prejudiced mirrors that of lesbian mothers, who try to minimize children’s exposure to heterosexism, by protecting their children from exposure to anti-LGBTQ family members (Goldberg et al., Citation2016).

Although in some cases mothers told children not to mention bisexuality+ in front of certain family members, for several mothers the worry that their children would “inadvertently say something” about their bisexuality+ meant they had previously chosen not to talk about their orientation to their children: “it was just easier to not talk about it”. Others described a sense of conflict between wanting to be open with their children but also worrying about the child outing them, discussing how they felt that telling the child not to raise the topic in front of certain family members would undermine the values they were instilling around openness. One mother said,

I want to raise them how I am and how I want to live my life [openly and proudly] … but how do I [raise them in a way which aligns with my values] and then go in and say ‘oh but don’t tell your uncle’.

Honesty, authenticity, and relationships

In a similar way to adoptive parents, who often express support for open communication about adoption within the family (Jones & Hackett, Citation2007), and lesbian mothers, who value open conversation with their children (Gabb, Citation2004; West & Turner, Citation1995), bi+ mothers in this study valued honesty and openness, as they wanted to be their authentic selves with their children. They did not want to lie about their bisexuality+, keep it a secret, or hide part of themselves or their pasts from their children. Parents wanted their children to truly know them, as they considered their children some of the most important people in their lives. They discussed how they believed being open with their children would benefit the mother-child relationship and would encourage children to be open with them in return.

Openness and honesty

Many mothers believed that being open with children was important: “I’m planning to be very open with her… and I think that that’s really important”. Mothers felt positive about the open conversations they were having with their children, with some believing that being able to have open conversations with their children improved their parenting: “we can talk about things and… I think in that sense it makes me a better mum”. Bi+ mothers did not want to deceive their children: “I don’t want… to lie to her about [my orientation]”. Mothers mentioned not wanting to keep their orientation a secret, as they felt this would make bisexuality+ seem wrong: “I just don’t see the point in having secrets with her, as it makes things out to be kind of soured and dirty almost”.

Not hiding themselves or their pasts so their children know them

Mothers discussed not wanting to hide an important aspect of their identity from their children and wanting children to know the true and whole them: “I want him to know who I am and not hide any of that from him”. One bi+ mother who was parenting with a woman, expressed that they wanted to explicitly tell their child they were bi+ so their child did not assume they were lesbians: “I wouldn’t want them to have the wrong assumption about me”. Parents expressed that they did not want to hide their pasts, reflecting that if they did not come out to their children, they would “not know a huge part of [their] live[s]”. Mothers reflected on their experiences of previously hiding their bisexuality+ from their children; one mother explained that they “tried to keep it from [their child] when she was really little” and remembered “having girlfriends and just saying ‘this is my friend’”. Mothers felt that their period of hiding was unhealthy and described feeling better since being open with their children, saying “it feels good to live authentically”.

Knowing each other and building a strong relationship

Some mothers expressed that they were open with their children about their bisexuality+ for “relationship building” purposes and wanted “to really know each other”. Some parents reflected upon how being open about their bi+ identity had already aided their relationship, saying “I think it’s made us closer as well, because it’s more honesty that you have”. This is similar to how transgender parents reported positive changes to parent-child relationships after beginning to live authentically (Veldorale-Griffin, Citation2014). In the current study, bi+ mothers wanted to build relationships within which their children would feel comfortable talking to them and some parents specifically wanted their children to be able to talk to them if they were LGBTQ or questioning: “if [my daughter] was ever to find herself in the position where she is questioning… at least she knows that she has got the option to be able to come and talk to me”. This is similar to gay/lesbian/bisexual parents in Ackbar’s (Citation2011) study, who wanted their children to feel comfortable approaching them with questions regarding gender and sexuality.

Supporting LGBTQ children

Some mothers who had not explicitly told their children that they were bi+ said that their children coming out to them would be a reason for them to come out to their children, to offer support and solidarity, corroborating Haus’ (Citation2021) findings. For instance, one participant in the current study said they would come out to their child “if she is having issues with something, and it is something that I can say ‘well actually… I am bi… this is my experience’”. One mother mentioned how they had not come out until their child did, explaining that “I kept it under wraps until my younger daughter came out” and then came out “to support [my] kids”. In some cases, children of bi+ mothers were LGBTQ and had been able to come out to their already out mother; one mother reflected that it was “nice that they feel they can come to [me]”.

Normalizing bisexuality+

Some bi+ mothers wanted bisexuality+ to be normalized: “I want it to be normalized and so I want her to grow up knowing that it’s OK”. This is a form of mainstream queer socialization (Mendez, Citation2020), which is similar to that of lesbian/gay/queer parents, who teach their children that their family is ‘the same’ as any other family (e.g., Breshears, Citation2011) or emphasize similarities between their family and other families (Goldberg et al., Citation2016). In the present study, bi+ mothers who took this normalizing approach did not want to indicate to their children that bisexuality+ was uncommon or unusual: “I am not trying to point out that [bisexuality is] rare and I’m special”. Due to mothers’ normalizing approaches, LGBTQ issues and bisexuality+ were unremarkable to children: “(child) accepts it the same as like he’s having baked beans for dinner”.

Living it to normalize

Some mothers believed that by living their bisexuality+ openly in front of their children, their children would learn not only that their mother was bi+, but also that bisexuality+ was normal. For instance, one mother explained that they believed “it should be normal, so I am just going to act like it is”. Another said, “I don’t think it’s going to be an issue with the children at all, because they’re just growing up with it as the norm”. Parents said that they wanted to make their children “comfortable and surrounded by those kind of things being normal”.

Everyday conversations to normalize

Mothers also attempted to normalize bisexuality+ through talking about it naturally within everyday conversations: “[I] just naturally incorporated [talks about bisexuality+] into day-to-day stuff, and then it’s no big deal”. Mothers often steered away from having a formal sit-down conversation about their bisexuality+: “I don’t want to have any big talk… about sexuality”. Instead, parents had conversations about bisexuality+ whilst doing everyday tasks: “[we talk about the topic] while going home from school or while cooking dinner, so it’s less pressure… because if you sit them down it’s already scary”.

Using representation to normalize

It was important to parents that their child knew that they were not odd or unusual for having a bi+ mother or for having two mothers. Mothers used representation of similar families in books to show their children this; for instance, one mother explained “[we provided books with same-gender representation] so he knows it’s not like we’re really odd and we’re the only ones”. Representation in books was especially important for some due to the pandemic limiting in-person LGBTQ parent-child groups or other spaces where their child would normally get to meet other LGBTQ parent families. One mother explained, “we weren’t seeing anybody in person who has two mums or two dads… so I’m trying to at least have that [representation] in books”.

Diversity, acceptance, and celebration

Just as gay fathers teach children values of tolerance and acceptance (Bozett, Citation1980), and bi+ parents want to teach their children to be allies (Haus, Citation2021), in the current study bi+ mothers wanted to teach their children to be accepting of others of all genders and sexual orientations. Mothers also celebrated bisexuality+, and LGBTQ identities with their children, in the same way that lesbian and gay parents participate in the queer community by attending pride with their children (Bos et al., Citation2008; Mendez, Citation2020; Mitchell, Citation1998).

Teaching about diversity

Many mothers prioritized teaching their children about diversity and explained how important it was for them to teach their children about different types of relationships and attraction beyond heteronormative frameworks. One mother explained “[it] became really important to me that they understood that relationships don’t look a certain way, and attraction doesn’t look a certain way”.

Some taught about diversity through conversations that aimed to challenge heteronormativity; one mother explained how she spoke about diversity in family structures, saying “we just talk about ‘some people have two mummies, some people have two daddies, some people have a mum and dad, some people have one mum or one dad’”. Other conversations focused on teaching children about diversity of sexuality: “I am very conscious to point out men can marry men, and women can marry women”. Sometimes conversations around diversity were linked to the mother’s orientation specifically; one parent discussed coming out to their child to challenge heteronormativity, saying “it’s important for him to know that even a family that does have a mama and a papa, isn’t… necessarily a straight family”.

Other mothers used representation in books to teach children about diversity, despite it being challenging to find such books. One mother described how they had “gone out of [their] way to… get a lot of kids’ books with diverse families, including same-sex families, including disabled families… families from different ethnic backgrounds”. It seemed important to some mothers to not only teach about diversity in terms of gender and sexuality, but also in terms of (dis)ability and ethnicity, which mirrors findings from research on gay fathers (Bozett, Citation1980).

Encouraging acceptance and being accepting

Mothers wanted to ensure that their children grew up to be accepting of LGBTQ people: “[I] obviously want [my child] to grow up being able to be open and supportive of everyone”. Some mothers felt a sense of obligation to ensure that their children would grow up to be accepting: “I [would] feel really bad if they grow up as adults and then they were anti-LGBT and it would break my heart, like did I not explain it well enough to them?”.

Parents also discussed being accepting of their children, with many discussing their desire for their children to be able to be who they are in terms of gender and sexuality. One mother said, “if she… decides that she likes girls or boys or both or no one… she doesn’t have to be scared about how we react because… she can always be herself”. Some parents wanted to raise their children without expectations about their sexuality: “we don’t make assumptions about whether she will have boyfriends or girlfriends, or neither, or both”. This desire to not assume children’s sexualities affected how mothers spoke with their children, especially regarding the topic of their future lives, with parents using inclusive or neutral language when talking about their children’s future partners, to not making heteronormative assumptions. One mother explained that they had said to their child “when you’re older you might want a girlfriend or you might want a boyfriend, and that’s okay, you can marry a man, you can marry a woman, or you can not marry anyone”. Parents also challenged other people’s heteronormative assumptions regarding their children’s future partners; one mother described how they would add “or husband, or no-one” when people discussed their son having a wife in the future.

Celebrating and being proud

Bi+ mothers wanted to instill a feeling of pride into their children and celebrated their bisexuality+ with their children by taking them to community events, such as BiConFootnote3 and Pride, from infancy. Parents with older children discussed children’s active involvement in pride parades: “[my daughter] came to pride with me… when she was about 10 and helped carry the banner and was definitely interested in it all and liked being there”. Pride was a way for parents to celebrate their bisexuality+ with both their children and the broader community, and to teach their children that people “can love anybody they want”. Some mothers celebrated their bisexuality+ at home with their children; for example one mother explained that last year they had “had a virtual bi celebration day”.

Discussion

This study offered the first in-depth, qualitative exploration of bi+ mothers’ experiences of discussing their bisexuality+ with their children. The findings present a complex and varied picture of how bi+ mothers, in various family structures, discuss their bisexual + identity with their children, as well as how they engage in queer socialization practices. Mothers took child-focused approaches, showing a consideration of children’s needs when deciding when, and how, to discuss their orientation with their children.

It is salient that bi+ mothers considered the right time to discuss their bisexuality+ with their children, with many choosing to tell their children early in childhood, as the age at which mothers disclose their bisexuality+ to children may impact how they respond, and even their developmental outcomes. As research suggests that early disclosure promotes more positive outcomes for adopted children (e.g., Brodzinsky, Citation2006) and children conceived using donor gametes (Ilioi et al., Citation2017), it is possible that early disclosure promotes optimal outcomes for the children of bi+ mothers too. Additionally, later disclosure or non-disclosure could cause problems, as secrecy can jeopardize communication between family members and create distance between those who know and do not know the information (Bok, Citation1982). It is also possible that non-disclosure could negatively impact children’s psychological adjustment indirectly via parenting because non-disclosing LGBTQ women face poorer mental health outcomes (Pachankis et al., Citation2015), and poorer mental health is associated with less optimal parenting behaviors such as lower maternal sensitivity (Bernard et al., Citation2018). Future research should explore if disclosure/non-disclosure of maternal bisexuality+ is associated with family functioning or child outcomes, and whether there is in fact an optimal time for bi+ mothers to discuss their bisexuality+ with their children, in order to promote the best developmental outcomes.

Mothers used developmentally aware and age-appropriate approaches to explain their bisexuality+ to their children or raise LGBTQ topics with them. These explanations were often influenced by mothers’ parenting and dating situations at the time, with single and polyamorous mothers more often explaining bisexuality+ in relation to dating behavior, and preparing children for them dating someone of the same gender. The fact that bi+ mothers prepared their children for them dating might mean that children of bi+ mothers may respond more positively to their mother finding a new partner, as research suggests that children who receive little communication about this transition often feel confused, hurt, and betrayed (Cartwright & Seymour, Citation2002). Mothers in a relationship with the father of their child(ren) were often wary of employing a dating explanation as they feared their child would worry about the parental relationship ending, thus highlighting a unique challenge for some bi+ mothers wishing to explain their bisexuality+ to their children.

Another unique challenge facing bi+ mothers was shielding children from anti-LGBTQ rhetoric; some mothers discussed preparing children for people’s negative conceptions of bisexuality+ and others discussed asking their children not to raise the topic in front of anti-LGBTQ family members. Although mothers rarely asked children to keep their bisexuality+ a secret, and did so in order to protect their children, this may have negative implications for children’s relationships with family members or their psychological well-being, as secret-keeping is related to psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Frijns & Finkenauer, Citation2009). Additionally, it is possible that children may not be able to keep the secret of their mother’s bisexuality+, as research with adoptive families has found that children were not able to maintain a state of non-disclosure regarding their adoption to younger siblings (Jones & Hackett, Citation2007).

As well as considering children’s needs, bi+ mothers were conscious of the LGBTQ community and wider society, and these considerations shaped their socialization and parenting practices. Bi+ mothers, including those parenting in “straight-passing” relationships, engaged in a variety of queer socialization practices previously observed in gay/lesbian parent families (e.g., Gianino et al., Citation2009; Gipson, Citation2008; Goldberg et al., Citation2016; Oakley et al., Citation2017). Some bi+ mothers engaged in behaviors and conversations which could be categorized as “preparation for bias” (Hughes et al., Citation2006), either discussing discrimination with their children to “prepare” them for encountering negative conceptions of bisexuality+ or encouraging their children not to mention their orientation in certain situations to avoid discrimination. Additionally, bi+ mothers engaged in “queer cultural socialization” (Mendez, Citation2020), such as teaching their children about queer culture and diversity, through media, and celebrating queer community events with children. For some bi+ mothers, books with queer representation had become more important during the pandemic due to the lack of opportunities to participate in queer community events. This suggests that media representation may be used as a way of providing individuals with a sense of belonging or connection to the LGBTQ community, which is important given that the bisexual-specific stress that many bi+ individuals face in LGBTQ spaces (Tavarez, Citation2020) can lead to feelings of exclusion and isolation for bi+ people. Social media use has been identified as a way of seeking social support and connectedness among LGB adults (Escobar-Viera et al., Citation2018) and LGBTQ adolescents (Berger et al., Citation2021), and so could also be explored as a source of support for bi+ mothers feeling isolated.

As ethnic-racial socialization messages which promote pride are positively associated with ethnic-racial identity development in youth (Peck et al., Citation2014), it could be the case that queer cultural socialization and celebration may help bi+ mothers’ children develop a positive family identity. Future research should explore whether queer cultural socialization practices relate to children’s conceptions of their queer parent family. Finally, some bi+ mothers engaged in mainstream queer socialization (Mendez, Citation2020), taking a normalizing approach, avoiding treating bisexuality+ as something unusual.

Hence, it appears that the socialization behavior of bi+ mothers, even those in heterosexual-passing relationships, is distinct from heterosexual parents’, given bi+ mothers’ queer socialization practices. Whereas heterosexual parents often hold heteronormative assumptions and only discuss the possibility of adult heterosexual relationships with their children (Heisler, Citation2005; Martin, Citation2009), bi+ mothers often attempted to challenge heteronormativity by using inclusive language to discuss their children’s future partners. Thus, by studying bi+ mothers, the current study allowed a unique exploration of the effects of parental sexuality on parenting, by including bi+ parents in heterosexual-passing relationships. This allowed the isolation of parental sexuality, without the confound of the gender composition of parents’ relationships. The current research therefore contributes to the debate on the influence of parental sexuality on parenting, and suggests that parental sexuality was more important for determining this aspect of parenting behavior than the gender composition of parents’ relationships.

In terms of limitations, although the qualitative interviews generated a wealth of incredibly rich data, the sample was relatively homogenous in mothers’ ethnicity and education (DeVault & Gross, Citation2012). As being more educated is associated with higher scores of coming out to family (Pistella et al., Citation2016), and White LGBT people have been found to have a more positive view of their orientation in comparison to people of color (Feldman, Citation2012), which could affect the outness of bi+ mothers of color, the findings may over-state how open bi+ mothers are with their children about their bisexuality+. Additionally, the extent and experiences of LGBTQ community involvement, may be an artifact of the Whiteness of the sample, as LGBTQ people of color may have different experiences with these spaces due to racism and microaggressions in LGBTQ spaces (Balsam et al., Citation2011; Han, Citation2007; Lehavot et al., Citation2009). Future research should recruit more diverse samples, to explore the experiences of those at the intersection of multiple systems of oppression. It is also important to acknowledge that the study only included mothers’ perspectives and that mothers with more positive experiences may have been more likely to participate. Hence, the findings may overstate the positivity of bi+ mothers’ disclosure experiences and findings should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

As the use of in-depth qualitative methods lends itself to informing the design of future research, it is hoped that the themes developed from this study may inform future quantitative studies. Future studies should examine possible links between disclosure and children’s/family functioning outcomes, including parental psychological well-being, partner support, and child psychological adjustment. Future studies should also take a multi-informant approach, including the perspectives of other family members, to gain a more holistic understanding. Future research would also benefit from a longitudinal approach. The disclosure literature suggests that disclosure intentions are not always followed (Readings et al., Citation2011), so it will be important to understand whether mothers’ plans come to fruition and how conversations within the same family evolve over time.

Implications

This research begins to explore conversations about bisexuality+ and queer socialization practices in bi+ mother families. It is hoped that this study will not only amplify the voices of bi+ mothers but contribute to the broader understanding of bisexuality+ throughout the life course, as well as the fields of LGBTQ family research, disclosure, and queer socialization. The findings of this study are relevant theoretically in that they further understandings of communication and parenting within bi+ mother families, an area that has previously received little scholarly attention. Practically, the study will prove vital for developing guidance for bi+ mothers about effective ways to come out to their children, including information on potential challenges relating to children’s understanding and children’s concerns about certain explanations. Currently, no such advice exists, and participants said this lack of guidance was a challenge for them. In addition, this study allows the development of timely support for mothers, with findings suggesting that support may be most appropriate during early childhood and adolescence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the families who took part in this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Bi+ is an inclusive term that encompasses all non-monosexual identities (i.e., anyone who is attracted to more than one gender). This terminology is useful as non-monosexual people are known to use a variety of labels, including bisexual, bi, pansexual, pan, omnisexual, plurisexual, and queer. The use of the term bi+ throughout this article acknowledges the variety of language non-monosexual people use to describe their identities.

2 “Non-binary” is an umbrella term that includes those whose identity falls outside of or between the identities of man and woman. Some non-binary people experience feeling both masculine and feminine at different times, whereas others do not experience or want to have a gender identity at all (Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017). Non-binary can be a gender label in and of itself but is also an umbrella term encompassing the identities genderqueer, genderfluid, and agender, which some participants identified themselves as in the current study.

3 BiCon is a weekend-long event for bi+ people, which has been running since 1984, and is held annually in different parts of the UK. It involves discussion groups and sessions, social spaces, and entertainment.

References

- Ackbar, S. (2011). Constructions and socialization of gender and sexuality in lesbian-/gay headed. families (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved from PsycINFO.

- Alexander, L. B., Dore, M. M., Hollingsworth, L. D., & Hoopes, J. W. (2004). A family of trust: African American parents’ stories of adoption disclosure. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(4), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.448

- Anders, M. (2005). Miniature golf. Journal of Bisexuality, 5(2-3), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J159v05n02_13

- Arden, K. (1996). Dwelling in the house of tomorrow: Children, young people and their bisexual parents. In S. Rose & C. Stevens. (Eds.) Bisexual Horizons: Politics, Histories, Lives, (pp. 121–152). Lawrence & Wishart Ltd.

- Balsam, K. F., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., Simoni, J., & Walters, K. (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT people of color microaggressions scale. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023244

- Berger, M. N., Taba, M., Marino, J. L., Lim, M. S. C., Chenoa Cooper, S., Lewis, L., Albury, K., Chung, K. S. K., Bateson, D., & Skinner, R. (2021). Social media’s role in support networks among LGBTQ adolescents: A qualitative study. Sexual Health, 18(5), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH21110

- Bernard, K., Nissim, G., Vaccaro, S., Harris, J. L., & Lindhiem, O. (2018). Association between maternal depression and maternal sensitivity from birth to 12 months: A meta-analysis. Attachment & Human Development, 20(6), 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1430839

- Bok, S. (1982). Secrets. Pantheon Books.

- Bos, H. M. W., & Gartrell, N. (2010). Adolescents of the USA national longitudinal lesbian family study: Can family characteristics counteract the negative effects of stigmatization? Family Process, 49(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01340.x

- Bos, H. M. W., Gartrell, N., Peyser, H., & van Balen, F. (2008). The USA national longitudinal lesbian family study: Homophobia, psychological adjustment, and protective factors. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 12(4), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160802278630

- Bostwick, W. B., & Dodge, B. (2019). Introduction to the special section on bisexual health: Can you see us now? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1370-9

- Bowling, J., Dodge, B., & Bartelt, E. (2017). Sexuality-related communication within the family context: Experiences of bisexual parents with their children in the United States of America. Sex Education, 17(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1238821

- Boykin, A. W., & Toms, F. D. (1985). Black child socialization: A conceptual framework. In H. P. McAdoo & J. L. McAdoo (Eds.), Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. (pp. 33–51). Sage.

- Bozett, F. W. (1980). Gay fathers: How and why they disclose their homosexuality to their children. Family Relations, 29(2), 173–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/584068

- Brand, K. (2001). Coming out successfully in the Netherlands. Journal of Bisexuality, 1(4), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J159v01n04_05

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breshears, D. (2011). Understanding communication between lesbian parents and their children regarding outsider discourse about family identity. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7(3), 264–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2011.564946

- Brodzinsky, D. M. (2006). Family structural openness and communication openness as predictors in the adjustment of adopted children. Adoption Quarterly, 9(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J145v9n04-01

- Cartwright, C., & Seymour, F. (2002). Young adults’ perceptions of parents’ responses in stepfamilies. What hurts? What helps? Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 37(3-4), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v37n03_07

- Cohen, R., & Kuvalanka, K. A. (2011). Sexual socialization in lesbian-parent families: An exploratory analysis. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(2), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01098.x

- DeVault, M. L., & Gross, G. (2012). Feminist qualitative interviewing: Experience, talk, and knowledge.In S.N. Hesse-Biber (Ed.) The handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis. (pp. 206–236). Sage.

- Dyar, C., Feinstein, B. A., & London, B. (2014). Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000063

- Escobar-Viera, C. G., Whitfield, D. L., Wessel, C. B., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Brown, A. L., Chandler, C. J., Hoffman, B. L., Marshal, M. P., & Primack, B. A. (2018). For better of for worse? A systematic review of the evidence on social media use and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual minorities. JMIR Mental Health, 5(3), e10496. https://doi.org/10.2196/10496

- Feldman, S. E. (2012). The impact of outness and lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity formation on mental health (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University).

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (Edition 5). SAGE.

- Frijns, T., & Finkenauer, C. (2009). Longitudinal associations between keeping a secret and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408098020

- Gabb, J. (2004). Sexuality education: How children of lesbian mothers ‘learn’ about sex/uality. Sex Education, 4(1), 19–34.

- Gartrell, N., Banks, A., Hamilton, J., Reed, N., Bishop, H., & Rodas, C. (1999). The national lesbian family study: 2. Interviews with mothers of toddlers. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69(3), 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080410

- Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender? UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from: How Many People are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender? - Williams Institute (ucla.edu)

- Gates, G. J., Badgett, M. V., Macomber, J. E., & Chambers, K. (2007). Adoption and foster care by gay and lesbian parents in the United States. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2v4528cx

- Gianino, M., Goldberg, A., & Lewis, T. (2009). Family outings: Disclosure practices among adopted youth with gay and lesbian parents. Adoption Quarterly, 12(3-4), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926750903313344

- Gipson, C. K. (2008). Parenting practices of lesbian mothers: An examination of the socialization of children in planned lesbian-headed families. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Goldberg, A. E., Gartrell, N. K., & Gates, G. J. (2014). Research report on LGB-parent families.

- Goldberg, A. E., Sweeney, K., Black, K., & Moyer, A. (2016). Lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents’ socialization approaches to children’s minority statuses. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(2), 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015628055

- Han, C. S. (2007). They don’t want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630601163379

- Hartman-Linck, J. E. (2014). Keeping bisexuality alive: Maintaining bisexual visibility in monogamous relationships. Journal of Bisexuality, 14(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2014.903220

- Hartwell, E. E., Serovich, J. M., Reed, S. J., Boisvert, D., & Falbo, T. (2017). A systematic review of gay, lesbian, and bisexual research samples in couple and family therapy journals. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(3), 482–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12220

- Haus, A. (2021). Making visible the invisible: Bisexual parents ponder coming out to their kids. Sexualities, 24(3), 341–369.

- Heisler, J. M. (2005). Family communication about sex: Parents and college-aged offspring recall discussion topics, satisfaction, and parental involvement. Journal of Family Communication, 5(4), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327698jfc0504_4

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S., Dodge, B., Schick, V., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2012). National survey of sexual health and behavior (data file). Unpublished raw data

- Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747.

- Ilioi, E., Blake, L., Jadva, V., Roman, G., & Golombok, S. (2017). The role of age of disclosure of biological origins in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents conceived by reproductive donation: A longitudinal study from age 1 to age 14. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12667

- Jones, C., & Hackett, S. (2007). Communicative openness within adoptive families: Adoptive parents’ narrative accounts of the challenges of adoption talk and the approaches used to manage these challenges. Adoption Quarterly, 10(3-4), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926750802163238

- Lee, R. M. (2003). The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(6), 711–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000003258087

- Lehavot, K., Balsam, K. F., Ibrahim., & Wells, G. D. ‐ (2009). Redefining the American quilt: Definitions and experiences of community among ethnically diverse lesbian and bisexual women. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20305

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Litovich, M. L., & Langhout, R. D. (2004). Framing heterosexism in lesbian families: A preliminary examination of resilient coping 1. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 14(6), 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.780

- Mac Dougall, K., Becker, G., Scheib, J. E., & Nachtigall, R. D. (2007). Strategies for disclosure: How parents approach telling their children that they were conceived with donor gametes. Fertility and Sterility, 87(3), 524–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1514

- MacCallum, F., & Keeley, S. (2012). Disclosure patterns of embryo donation mothers compared with adoption and IVF. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 24(7), 745–748.

- Manley, M. H., & Ross, L. E. (2020). What Do We Now Know About Bisexual Parenting? A Continuing Call for Research. In LGBTQ-Parent Families. (pp. 65–83) Springer.

- Martin, K. A. (2009). Normalizing heterosexuality: Mothers’ assumptions, talk, and strategies with young children. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400202

- Matsuno, E., & Budge, S. L. (2017). Non-binary/genderqueer identities: A critical review of the literature. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(3), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8

- Mendez, S. N. (2020). Queer socialization: A case study of lesbian, gay, and queer (LGQ) parent families. The Social Science Journal, 57, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1727240

- Mitchell, V. (1998). The birds, the bees… and the sperm banks: How lesbian mothers talk with their children about sex and reproduction. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080349

- Oakley, M., Farr, R. H., & Scherer, D. G. (2017). Same-sex parent socialization: Understanding gay and lesbian parenting practices as cultural socialization. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2016.1158685

- Pachankis, J. E., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 890–901. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000047

- Peck, S. C., Brodish, A. B., Malanchuk, O., Banerjee, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2014). ). Racial/ethnic socialization and identity development in Black families: The role of parent and youth reports. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1897–1909. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036800

- Pew Research Center (2013). A survey of LGBT Americans. Available at: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americans/

- Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., Laghi, F., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Coming-out to family members and internalized sexual stigma in bisexual, lesbian and gay people. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3694–3701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0528-0

- Pollitt, A. M., Brimhall, A. L., Brewster, M. E., & Ross, L. E. (2018). Improving the field of LGBTQ psychology: Strategies for amplifying bisexuality research. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000273

- Readings, J., Blake, L., Casey, P., Jadva, V., & Golombok, S. (2011). Secrecy, disclosure and everything in-between: Decisions of parents of children conceived by donor insemination, egg donation and surrogacy. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 22(5), 485–495.

- Ross, L. E., & Dobinson, C. (2013). Where is the “B” in LGBT parenting? A call for research on bisexual parenting. In LGBT-parent families. (pp. 87–103) Springer.

- Ross, L. E., Siegel, A., Dobinson, C., Epstein, R., & Steele, L. S. (2012). I don’t want to turn totally invisible”: Mental health, stressors, and supports among bisexual women during the perinatal period. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 8(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2012.660791

- Spencer, M. B. (1983). Children’s cultural values and parental child rearing strategies. Developmental Review, 3(4), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(83)90020-5

- Tasker, F. (2005). Lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children: A review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 26(3), 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200506000-00012

- Tavarez, J. (2020). I can’t quite be myself”: Bisexual-specific minority stress within LGBTQ campus spaces. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(2), 167–177.

- Veldorale-Griffin, A. (2014). Transgender parents and their adult children’s experiences of disclosure and transition. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(5), 475–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.866063

- West, R., & Turner, L. H. (1995). Communication in lesbian and gay families: Building a descriptive base. In T. J. Socha & G. H. Stamp. (Eds.), Parents, children, and communication: Frontiers of Theory and Research (pp. 147–169). Routledge.

- Yang Costello, C. (1997). Conceiving identity: Bisexual, lesbian and gay parents consider their children’s sexual orientations. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 24(3), 63–90.