Abstract

Assisted conception practices contribute to an increasingly complex relational landscape. This article draws from a qualitative study that investigated narratives about the negotiation of relatedness in lesbian known donor reproduction in Aotearoa New Zealand. Twenty-six interviews, with 60 adults, across 21 lesbian known donor familial configurations at different stages of forming family through known donor insemination were conducted. The article demonstrates how parties using this form of insemination – lesbian couples, known donors and known donor partners – invoke divorce discourse as a kinship resource. The families these women and men were creating or had already established were the product of deliberate pre-conception planning rather than the result of separation or divorce following the breakdown of an intimate relationship. Nevertheless, divorce discourse supported them to make sense of possibilities for the kin status and place of known donors and their partners within the kinship structures put around children given they have no obvious place within these structures. The article argues the use of divorce conventions serves to both disrupt and uphold traditional parenting discourses and practices.

Introduction

In a time of unprecedented possibilities for intimate life, assisted conception can contribute to complex adult-adult and adult-child relational interconnections and care arrangements. When lesbian couples conceive children using sperm from male relatives, friends, acquaintances, or strangers met on social media platforms who they subsequently come to know, they must figure out these interconnections and care arrangements without established models specific to their circumstances to guide them. While experienced as unique to the biographies of particular lesbian couples and known donors and their partners, practices of relatedness and caregiving occur against a background of social transformations impacting trends in relational and family life in late modern society. The diversification of relational and family patterns and the normalization of divorce are examples of these trends (Stacey, Citation1996).

This article draws from a qualitative study that investigated stories about the negotiation of relatedness in lesbian known donor reproduction in Aotearoa New Zealand. The overall purpose of the study was to explore the contours of this form of reproduction through a close analysis of the place of known donors in the social networks of the children they help to conceive, while contributing to theoretical debates on the sociology of the family (Surtees, Citation2017). Sixty adults across 21 lesbian known donor familial configurations at different stages of forming family through known donor insemination participated in the study. The adults included lesbian couples, gay and heterosexual known donors and their partners, and single gay and heterosexual known donors. In the absence of an obvious model, a significant number of these women and men drew on divorce discourse, or public discourse about divorce, as a kinship resource. Divorce discourse, as a resource, helped them make sense of how the men might feature in children’s lives, as they planned for or set possibilities in motion prior to or following home-based or fertility clinic-based insemination. That is, they reflexively constructed and gave meaning to various possibilities in relation to conventions associated with separation and divorce, despite their familial configurations resulting from deliberate planning before conception rather than from unplanned changes in circumstances.

Divorce has a long history in Western countries (Fahey, Citation2014), including in Aotearoa New Zealand, where Phillips (Citation1981) volume remains the most significant published history on the topic (Blondell, Citation2023). Public discourse about divorce, in conjunction with separation and divorce conventions, and divorce reform, have evolved over time and from within particular social, political, and moral contexts (see for example, Adams & Coltrane, Citation2007; Phillips, Citation1981; Smart, Citation2004). While the timing and pace of this evolution has varied across Western countries, some shared trends have been documented, including shifts from fault-based divorces to no-fault divorces (Fahey, Citation2014), to a focus on child custody and support mechanisms based on the principle of the child’s ‘best interests’ (Adams & Coltrane, Citation2007; Fine & Fine, Citation1994), including the development of near universal child maintenance policies (Hakovirta & Skinner, Citation2021). While early post no-fault reforms focused on redressing custodial mother’s financial disadvantage, some aspects of later reform responded to non-custodial father’s agitation for joint custody following on from the worldwide phenomenon of father-right movements (Adams & Coltrane, Citation2007; Busch et al., Citation2014; Gregory & Milner, Citation2011). Subsequent changes to divorce law in the West reflect the contemporary preference for continuing contact with both parents, with joint custody or shared care now relatively common (Brown, Citation2021; DiFonzo, Citation2014; Hakovirta et al., Citation2022; MacKenzie et al., Citation2020).

In this article, the concept of divorce discourse captures the women’s and men’s references to distinct separation and divorce conventions whether directly expressed or implied. These references included an emphasis on couple conflict as a precursor to separation and divorce and as an ongoing factor in decisions about parental contact with children post separation and divorce. They also included conventions about the day-to-day care of children post separation and divorce, such as the maintenance of a main residence and cross-residential co-parenting. Reflecting the preference for continuing contact with both parents evident in law, the option of cross-residential co-parenting—akin to joint custody or shared care—appeared influential in the women and men’s decisions about the day-to-day care of their children, even though their arrangements were not the result of separation or divorce. Currently, Aotearoa New Zealand law favors shared care in some shape or form following the dissolution of a marriage (Busch et al., Citation2014; MacKenzie et al., Citation2020). The women and men’s implication in family boundary work in response to competing interests in belonging and differing residential and parenting expectations are central themes in this article; these themes illustrate how the use of separation and divorce conventions simultaneously disrupt and uphold traditional parenting discourses and modes of parenting.

Lesbian known donor reproduction

Lesbian known donor reproduction is a well-established pathway to parenthood in Aotearoa New Zealand. The country’s largest fertility service provider, Fertility Associates, strongly encourages their lesbian (and heterosexual) clientele to use known donors on the grounds that they facilitate timely initiation of clinic mediated conception procedures (Fertility Associates., n.d.). An estimated 60% of their clientele follow this advice, subsequently recruiting a known donor to work with them through the clinic, rather than wait for an identity-release donor to become available (Chisholm, Citation2016).Footnote1 Currently, the provider advises the wait for an identity-release donor is approximately 2.5 − 3 years (Fertility Associates., n.d.). As the only legislated alternative to a known donor using standard clinic mediated conception strategies, this wait would presumably be unacceptable to some women given the reality of age-related declines in fertility. As national studies have demonstrated, women who attempt to conceive after their reproductive peak may find it difficult or impossible (see for example, Righarts et al., Citation2015).

National and international research suggests that many lesbians choose a known donor in response to the discourse that all children have the right to a father and/or information about their paternal origins. Broadly speaking, the research suggests two trends. The first trend is for lesbians to recruit known donors who are willing to assume the title of father or the title and role of father. The second trend is for lesbians to recruit known donors who are open to contact with their children at some point, thus securing the right for them to access information about paternity in the future. Both trends are often evident in any one study. For example, both trends were evident in the focus study for this article. This was also the case in Nordqvist’s (Citation2012) study; the lesbian couples who chose a known donor did so because they believed either a father, or information about paternal origins, could be important for children. For these couples, kinship values, including the centrality of the couple relationship as the basis for parenthood, were balanced with couple intimacy, responsibility and knowledge about paternity. Likewise, lesbian couples in other studies chose known donors to either secure children a father and opportunities for his subsequent involvement or to secure knowledge about paternity (see for example, Dempsey, Citation2005; Hayman et al., Citation2014; Luce, Citation2010; McNair et al., Citation2002; Ripper, Citation2009; Ryan-Flood, Citation2005; Surtees, Citation2011).

Many lesbians favor organizing family life around coupledom. Preferring to control the terms of known donor involvement, they tend toward positioning these donors as fathers rather than fathers and parents or as other male figures, including uncles or friends (see for example, Côté & Lavoie, Citation2019; Hayman et al., Citation2014; Kelly, Citation2011; Nordqvist, Citation2012; Surtees, Citation2011). Studies show however, that children develop increasing agency in negotiating the role of their donors as they get older (see for example, Goldberg & Allen, Citation2013; Goldberg & Scheib, Citation2016; Haimes & Weiner, Citation2000).

While many lesbians do retain the core parenting relationship with children for themselves, a small number embark on co-parenting arrangements with known donors with the intention of distributing parenting across more than two adults and households (see for example, Côté & Lavoie, Citation2019; Herbrand, Citation2017). Characterized by the intention of each of the adults to take up a parental role of some description (Surtees & Bremner, Citation2020), the men are most often viewed as secondary parents relative to their female counterparts (Andreasson & Johansson, Citation2017). What happens when separations occur within these co-parenting groups, is the topic of Gahan’s (Citation2019) study.

Most of the studies cited to date consider lesbian known donor reproduction from the perspectives of lesbians. Riggs (Citation2008a, Citation2008b) has made an important substantive contribution to knowledge about this form of reproduction from the perspective of gay known donors. Who these men think they are in relation to children continues to warrant further attention (but see, Côté & Lavoie, Citation2019, Côté et al., Citation2020; Dempsey, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Ripper, Citation2008). Highlighting the ways in which they understand the discourse that all children have the right to a father and/or information about their paternal origins and related questions of children’s best interests, Riggs (Citation2008a, Citation2008b) shows how such understandings are brought to bear on the men’s negotiation of their status and place in children’s family lives. More recently, he has explored how their genetic matter is made salient in relation to kinship (Riggs, Citation2018).

A number of these and other studies mention disparities between the expectations of lesbians and gay known donors vis-à-vis the status and place of the donors, even where consensus was reached prior to the conception and birth of children (see for example, Côté & Lavoie, Citation2020; Dempsey, Citation2004, Citation2012a; Riggs, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Scholz & Riggs, Citation2013). Côté and Lavoie (Citation2019) stress the importance of dialogue to ensure expectations align and Surtees and Bremner (Citation2020) point out written agreements also have a part to play. Presumably, some disparities are to be expected given the absence of obvious models to guide decision-making.

Asking: “What possibilities are there for relatedness in lesbian known donor reproduction?”, this study builds on the concern with known donor status and place evident in the studies outlined above by identifying the use of divorce discourse as a kinship resource in the negotiation of involvement. This discourse has not previously been identified in research into this form of reproduction, hence it extends on existing knowledge about lesbian known donor family forms.

Conceptual framework

Theoretically, this study is located within the sociology of the family. It draws from Morgan’s (Citation1996) work on family as sets of practices and Smart’s (Citation2007, Citation2011) conceptualization of personal life.

Family practices

Morgan’s (Citation1996) assertion that the family is neither “a thing” nor “something thing-like and concrete” (p. 189) is developed through his theorizing of family as sets of practices. In his view, family practices are meaningful to the persons concerned and have the appearance of being natural and inevitable, because they occur at the level of the everyday. These insights convey a sense of action that require attention to what families do, both in terms of family relationships and family activities. In contrast with traditional, passive understandings of family as a timeless fixed unit or structure, the flux and fluidity of family living is to the fore. According to Morgan (Citation1996), family practices are orientated toward and designate family members; they “define who counts as a family member” (p. 10). In other words, the group of people involved in any one family practice can be distinguished as a family as distinct from other groups of people who are not included in that family. In this study, attention was paid to how the family practices of some of the lesbian couples served to designate family members. The couples engaged in family boundary work through processes of kin differentiation, connection and disconnection. Open or closed boundaries positioned known donors and their partners inside, or outside, the immediate family.

Personal life

Personal life draws on a toolbox of interrelated concepts, including relationality (Smart, Citation2007, Citation2011). As Smart (Citation2011) states, “relationality conjures up the image of people existing within intentional, thoughtful networks which they actively sustain, maintain or allow to atrophy” (p.17). The lesbian couples, known donors and donor partners in the study were caught up in such networks. Their familial configurations were deliberate networks, formed for the express purpose of conceiving children together, that were themselves located within wider intersecting family and kinship systems. Social relations within and across these systems were flexibly maintained.

With the boundaries between kin, ex-kin, and non-kin continuing to blur, personal life’s emphasis on relationality offers analytical possibilities for exploring the importance of connectedness with others (Smart, Citation2007). As Nordqvist (Citation2019) maintains, because questions about connectedness are to the fore in forms of assisted reproduction that utilize gamete donation, this approach can capture key features of the donating experience that are currently under-researched. In this study, personal life captured the ways in which participants—as parties to the donating experience—were embedded within and constituted by a field of ‘sticky’ (Smart, Citation2007) adult-adult and adult-child relationships. In refusing to take family as the only reference point for relationships (Smart, Citation2007), personal life opened conceptual spaces suited to exploring the participant’s divergent relational narratives; both family relationships and different forms of relatedness, including kin-like relationships and non-kin relationships needed to be accounted for, without presuming what forms particular familial configurations took or how they were distributed across households.

Moreover, personal life assumes the active nature of relating (Smart, Citation2007). It facilitates a focus on kinship as a set of practices, something people actively negotiate and do in everyday life that is specific to them and their relationships. Working out new ways of relating was a continuing exercise for the participants; kinship claims and thus identity and role possibilities were at stake.

Research overview and approaches

To reiterate, the study this article draws from investigated stories about the negotiation of relatedness in lesbian known donor reproduction. More specifically, it explored the negotiation of the status and place of known donors and their partners in the family lives of the children they expected to or had helped to conceive, with the donors’ status and place reflecting the two trends identified in the literature. In seeking to elicit stories about such negotiation, a qualitative narrative inquiry methodology was adopted, underpinned by the theoretical perspectives of family practices and personal life.

Identifying and selecting participants

As already noted, 60 adults across 21 familial configurations at various stages of forming families through lesbian known donor reproduction participated in the study.Footnote2 Initial recruitment of potential participants focused on lesbians and gay men who had already become parents through known donor insemination, were actively pursuing conception using this method, or were planning future parenthood via this method. Promotion of the study therefore targeted Aotearoa New Zealand-specific lesbian and gay media, organizations, social groups, and online mailing lists in an effort to locate lesbians and gay men who met these criteria. Those interested in learning more about the study were typically part of interconnected networks; snowball sampling, a useful strategy for accessing hard-to-reach populations (Fraenkel et al., Citation2015; Patton, Citation2015) proved fruitful. As recruitment progressed, the criteria broadened to reach heterosexual known donors and their partners, because it had become obvious that it was not the sexuality of donors that mattered per se. Rather, it was their potential to illuminate a wide range of social identity and role possibilities for men as known donors for lesbians, alongside their partners, in relation to the family lives of children, given their uncertain location within kinship structures. These men were fulfilling a number of parenting or non-parenting relationships and roles, which were operationalized by them in traditional and nontraditional ways.

Broadening the inclusion criteria provided space for exploring the fluid, contradictory and contested nature of known donor and donor partner relationships and roles and the bearing these can have on assumptions and beliefs about kin, kin-like and non-kin relatedness. In a context where many lesbians choose a known donor in order to secure children’s assumed right to a father and/or information about their paternal origins yet prefer to organize family life around coupledom, this is significant. Consistent with the study aims, this change to the criteria also served to facilitate a more nuanced understanding of possibilities for family narratives for others, besides those identifying as lesbian or gay.

Familial configuration and participant overview

The 21 familial configurations were categorized as either prospective familial configurations or existing familial configurations. The adult members of the prospective familial configurations were either actively pursuing conception using known donor insemination or were planning future parenthood using this method whereas the adult members of the existing familial configurations had already become parents in this way. The adult members of both configuration types mainly identified as PākehāFootnote3 or of European descent with only six identifying as Māori. The majority were from medium to high socioeconomic status backgrounds, in professional employment, and living in cities.

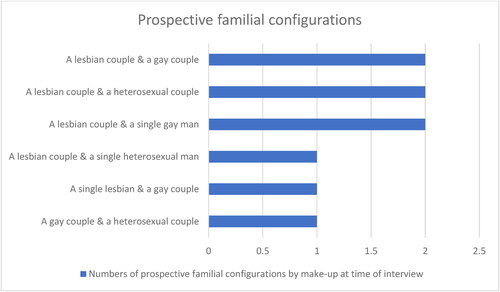

There were nine prospective familial configurations in total. These were made up of various lesbian, gay and heterosexual couples and singles combinations (see for details of make-up). Twenty-two of the 32 adult members of these familial configurations aged 25–39 years (M = 31.6, SD = 4.1), agreed to participate.

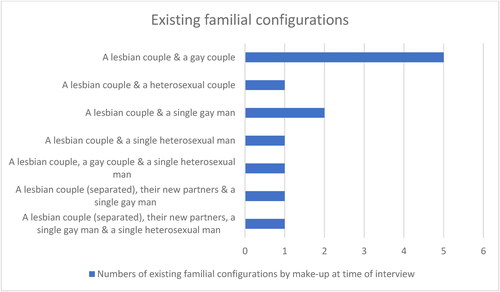

The remaining 12 familial configurations were categorized as existing familial configurations. While similarly varied in make-up, they also included a number of donor conceived children (see ). Thirty-seven of the 49 adult members of these familial configurations aged 29–66 years (M = 45.5, SD = 8.1, participated.

Figure 2. Existing familial configurations.

Note: Across these familial configurations, there was a total of 20 donor conceived children, ranging in age from new-born to 19 years old, with the majority aged five years old or under at the time of interviewing.

Twenty of the 60 participants, across two prospective familial configurations and four existing familial configurations feature in the ‘Divorce discourse: A kinship resource’ section of this article (see for their familial configuration make-up and other identifying characteristics). Interview material from 12 of the 20 is also shared in that section. These participants and the familial configurations they represent shared many similarities with those that do not feature in the article, although some that do not feature positioned known donors as uncles or friends, rather than as fathers or fathers and parents.

Table 1. Familial configuration make-up and identifying characteristics of featured participants at time of interview.

Collecting data

Accepted wisdom suggests everyone has a story to tell. The lesbians, known donors and donor partners in this study were no exception. Participants connected their experiences of lesbian known donor reproduction and practices of relatedness and boundary definition significant to them into spontaneous stories about particular happenings or actions they had taken or planned to take, and for the meanings they intended to convey. Their stories of the participants were collected through a total of 26 semi-structured narrative interviews, using a mix of group interviews, couple interviews and individual interviews.

In opening up topics and accommodating holistic, chronological and long accounts (Bold, Citation2012; Riessman, Citation2008), narrative interviewing supports storytelling. Riessman (Citation2008) states that “narrative interviewing is not a set of ‘techniques’ [and] nor is it necessarily ‘natural’” (p. 26). However, as she explains, interviewers can create a storytelling climate that fosters the telling and hearing of stories. Because relatedness must be negotiated together, participants were encouraged to tell their stories about this process in their familial configuration groupings where possible. Accordingly, 10 group interviews were conducted; these interviews included from three to five members of particular familial configurations, depending on their size. While not specifically designed as focus group interviews, in some interviews, the interactions between members of these familial configurations yielded shared views with their agenda predominating as is typical in focus groups (Cohen et al., Citation2018). Additionally, 11 couple interviews were held; in these cases, it proved impractical to bring together all members of the same configuration at the same place and time. Finally, five individual interviews were held, again for practical reasons. Most interviews were about two hours in duration, but a few were as short as one hour and others as long as three. Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed, before being returned to participants to check for accuracy. The rich interview data produced a total of 712 pages of transcript and reflected the accepted understanding in qualitative research that the well-managed interview can be a powerful tool (Gray, Citation2018).

Analyzing and re/presenting the data

As Taylor et al. (Citation2016) point out, “narrative analysis in sociology has developed from the insight that people often make sense of their lives (in interviews as well as everyday life) by telling and interpreting stories” (p. 270). While this form of analysis includes varied analytical possibilities, a concern with the ways participants story their understanding of reality is key (Taylor et al., Citation2016). In this study, a storied approach focused on a thematic analysis of what participants had to say about their experiences of lesbian known donor reproduction was adopted. That is, the content of what was told, rather than the form with which it was said or the actual structures of speech or social processes that were used to say it were to the fore. While the ‘what’ of the telling is arguably a primary concern of all narrative inquiry, in thematic analysis, content is typically the exclusive focus. As Sparkes (Citation2005) acknowledges, “The strength of this form of analysis lies in its capacity to develop general knowledge about the core themes that make up the content of the stories collected in an interview context” (pp. 206–207).

To develop knowledge about core themes, participant stories were dissected familial configuration by familial configuration. This step enabled experiences of lesbian known donor reproduction to be categorized thematically. To facilitate this process, interview transcripts were imported into Nvivo (QSR NUD*IST Vivo [nVivo], 2008), a qualitative data analysis software package. This was a useful mechanical tool that enabled differentiation between data within and across transcripts through coding. Relationships between the codes were then established before they were collated into broader themes, including divorce discourse, the specific focus of this article.

Because over-determination of themes can impact on story integrity and/or recognition of variation across stories (Sparkes, Citation2005), a number of the dissected participant stories were later reassembled as whole stories about specific familial configurations for the study report. In enabling the preservation of the rich detail found in long text sequences, this strategy helped maintain the integrity of the stories. In this article, whole stories have been replaced by story fragments that highlight the use of divorce discourse, however some long text sequences have been retained to illustrate their complexity.

While the data analysis processes outlined here might imply these were straightforward, this was not the case. Narrative data can be overwhelming and prone to unlimited analysis (Bold, Citation2012). Knowing the data could tell different stories, raised questions around which stories should be told. As Smart (Citation2010) states, “There is an inescapable sense that the data holds onto many more stories than one ever manages to bring forth into a written narrative” (p. 4).

Ethical considerations

The study was granted ethics approval from the University of Canterbury Human Ethics Committee. During recruitment, participants were supplied with information sheets that reflected standard ethical principles concerned with the protection of all parties in research involving humans. For example, the purpose of the research was outlined as were the details of what involvement would entail thus allowing participants to make informed decisions about participation or nonparticipation. The voluntary nature of participation and the right of withdrawal were specified. In addition, confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed; participants were promised their identities and the information they provided would be kept confidential and that real names or other identifying information would not be used in the study or related publications. Before data collection began, participants signed consent forms acknowledging these (and other) conditions. Finally, because the study explored a sensitive topic, information about appropriate support services was provided to participants, in the event they wanted support because of their involvement.

Divorce discourse: a kinship resource

Resonating with Stacey’s (Citation1996) notion of the divorce extended family, divorce discourse was used by the lesbian couples, known donors and donor partners in two distinct ways, as illuminated by analysis of the interview material drawn from some of the adult members of the six familial configurations introduced in this section. Firstly, divorce discourse was used in relation to maintaining open family boundaries and embracing a diverse relationship base for children. Secondly, it was used to frame understandings about cross-residential fathering and parenting arrangements, including the possibilities and demands of co-parenting.

Framing understandings about family boundaries

While all of the participants engaged in family boundary work typically associated with separation or divorce, how they framed understandings about family boundaries and where they drew boundary lines differed. Reflecting the first trend in the literature—lesbian recruitment of known donors who are willing to assume the title of father or the title and role of father—about half of the lesbian couples in the study rejected the established convention that parenthood is most appropriately located in co-residential coupledom. Choosing to support the fathering and/or parenting involvement of known donors and their partners, these couples situated the men inside, rather than outside, the immediate family. In these cases, divorce discourse featured in their stories in ways that helped explain the open, permeable nature of their familial configurations. The interview material that follows is illustrative.

Deena and Manny, members of the first familial configuration introduced here, conceived 10-week-old Hine through home-based insemination with the support of Mere and Barbara, their (respective) partners. In the extract that follows, Deena and Manny highlight the benefits of an expansive relationship base for children in ways that validate the inclusion of each of the four adults in their familial configuration, before Barbara briefly invokes divorce discourse seemingly to reinforce their messages:

Deena: I just think that she has got a much bigger family…. She’s got a really wide family automatically than if I’d just had a baby—for years I used to think: “I’m just going to have a baby and keep it to myself.” Now I think: “What am I doing?” That was about me, not the baby, you know? I just think that whole cultural enrichment…. Just that whole enrichment from different people. Having that social thing. So I think that—as I said before, that cliché: it takes a community to raise a child. That’s exactly that. It’s just expanding that. Whereas children that have a very small … you know, that nuclear family. There’s just so much less you’re exposed to. So, for me, it’s about exposing her and enriching her life. To me it is enrichment: love, enrichment and belonging.

Manny: And pretty much the same for me. She gets to enjoy a whole lot of different angles in life…. There’s just a whole number of things…. She’s going to get a taste of all sorts and that’s nice, as well as she’s got the security of having so many of us.

Barbara: Well, we’re four people straight off that really wanted her. You know? Rather than a couple that then divorce—a father and a mum. Four people straight away.

Felicity, a member of the second familial configuration introduced here also acknowledges the importance of an expansive relationship base for children. This extract includes an interjection by Felicity’s partner Tessa and references to Noah, who helped conceive five-year-old Phoebe and three-year-old Gretel. In the extract, Felicity draws on divorce discourse to weave together her professional experiences in family law with their personal experiences as the main residential parents of the girls:

Felicity: What I see a lot, are people squabbling over trying to exclude other people from a parenting role in their families. There are two things I’ve learnt as a result of this and my own experience. One is that whatever that niggle is about how that mother or that father is parenting, it will go. It won’t matter in three weeks’ time. So, the shit that you get, the phone calls on Mondays: “He’s come back from contact and … he didn’t get him to bed at seven o’clock”, it’s like, oh god, we’ve had that too you know. Where we ring him [Noah] and the kids are still awake at eight o’clock and actually you know, so what. So what.

Tessa: You want to yell at Noah: “Noah, get them to bed, cause tomorrow they’re going to be bloody tired!”

Felicity: And you know what? It’s just different. And they’re entitled to their experience of, that parent, not parenting as an agent of us and following our rules like some employee, some nanny, doing things our way. But actually just allowing that parenting role to develop with that other person. And the children to have the opportunity to enjoy that company where they’re not watching them feeling stressed about: “God, if they were home, they’d be in bed by now.” So that’s the first thing, is that there is validity in saying to people: “Look, just give the kids an opportunity to enjoy the time they have with their father doing it his way.” It’s not wrong. It’s just different. And also, reminding people that even if their relationship was intact there would still be those issues about parenting styles. So come on, put it into context. The second thing is about exclusion and somehow people have this idea that if they can limit the time that kids have with dad or with mum or with whoever the person is that they are out of favour with, the adults are out of favour with, that somehow that’s going to be better. Just encouraging people to think about the whole village concept. You know? It takes a village. That more people who love your kids is better than fewer…. Be open to there being a more expansive relationship base for your child.

Fluid family boundaries typically demanded effective communication, something the members of various familial configurations were aware of. Where this was the case, their utilization of divorce discourse extended to include an emphasis on what was advantageous about their arrangements with one another and why they worked, with divorced families used as a foil or contrast to these arrangements. Deena observed:

I say to people: “We’re really lucky because we were never an item.” So, it’s not like when you see parents—some parents, some parents manage it very well. They have a relationship, and it falls apart and it doesn’t work for them, and it affects the children. They’re fighting. We were never together but it was always about Hine, so we had that communication as well. I think that is what works.

I find it really interesting because we do almost like the divorced parent’s swap at the bay on a weekend. You know? Because it’s halfway basically, for us…. But rather than not being allowed to go into each other’s homes it just works for us that that be the changeover point. But I think the advantage for us is that we can talk and communicate. We don’t have any of that other baggage. We’ve no other baggage from relationships that we’ve had with each other. We are four grown-ups bringing up a beautiful little boy. And whatever things we’ve had going on in our own heads, or you know, stuff that’s happened for us at work, or whatever happens to be for the week, we still want to talk about what is best for Elliot at that time and how we can—what he’s been happy about or sad about and you know—it’s all about him really. And I think—I think if parents get over their own baggage and realise that the most important thing in their life, is actually bringing up that child or children.

Fern: Yeah, I mean I guess there’s lots of people who are … separated … I just think it’s a matter of basic cooperation, really … You know it just seems like it makes sense; this is what you do. We’ve known people where there’s a whole lot of rigidity about arrangements or there is no speaking between the separated parents. It’s awful. I’d hate to be in that situation.

Logan: Yes, you know like divorced couples, when it’s time to hand over they’re just waiting in the car.

Emma: I’d say what is limiting for say separated couples, is the level of conflict. I came to the conclusion when he was about two that three was the ideal number of parents.

Logan: The minimum, actually.

Emma: The minimum, we decided! … This really works but you have to like each other, and you have to cooperate and if you’ve just fallen out and divorced or separated, you’re unlikely—but in terms of say … bringing in people to help, or single women, it could work fantastically.

Framing understandings about cross-residential fathering and parenting arrangements

Not infrequently, participants who drew on divorce discourse in relation to open family boundaries also drew on it to frame understandings about cross-residential fathering and parenting arrangements in situations where known donors and their partners were not or did not expect to be the day-to-day parents of the children they directly or indirectly helped conceive. This was the case for Manny. Sharing his perspectives on this theme in an exchange with Deena, he appears to be mounting an argument about the legitimacy and practicality of their arrangements:

Manny: I knew that the way this had to work was if it was going to work, obviously it was going to be shared custody of Hine. That was all I really wanted—I wanted to be part of this little one’s life. But I also realised that—this is my view—that she really needed one solid home. I sort of realised that I would play probably more of a part time role in her life and Deena and Mere would be the primary caregivers. I’d play—I don’t want to put it like this: the weekend dad. Very much like how—I don’t want to say this either: the way separated couples work. You know? The dad has bubba on the weekends….

Deena: We decided that due to breastfeeding, especially right from the beginning, she was going to be with me. But when she’s seven and says: “I want to go to my dad on Wednesday”, then, if it works out with both of them, then that’s how it is going to be. Cause it’s about her.

Manny: So it’s not necessarily weekly—when it suits. It might be a couple of days during the week—whatever fits in with the routine. The thing is for me, I thought I’d heard of and seen how people kind of pull their kids for a week here and a week there and for me, that didn’t kind of work right. I think they need a place to call a base. I just thought it would be too much a tug of war, coming back and forth.

Like Manny, who thought Hine needed one solid home, Wilson believed the child he and Johan planned to conceive with Vivian and Moira would need a main home. And like Manny, he expected this would be with the women:

I think the child should be exposed to our home, so they know it’s their home, but I don’t believe in ‘pass the baby’…. This is a very strong opinion—I think those are very unsuccessful models of parenthood. I think they are based on a very negative situation, which is the divorce…. Maybe when the child is a bit more able to—I think it can work. But I think as a newborn it would be terrible to kind of move it around…. I get really disappointed when I see heterosexual couples who divorce—they put all the pain onto the child. “You will move to these houses, these times, with these people.” I think that’s terrible because it is your relationship that has fallen apart and you should be doing everything possible to kind of—. I’ve seen a couple of really successful examples. I don’t know how they made this work. They kept the main house. The parents moved. The child has a stable home: Their own bedroom, their own toys, their own everything…. Monday to Friday, father lives in the house. On the weekend, the mum does. They brought an apartment just down the road so that they could do this. Now I thought that was quite adventurous. I don’t know that would work long-term. I just think it’s really important that the burden is not put on to the child.

In imagining they would leave the daily, residential work of rearing children to the women they collaborate with, Manny and Wilson invoke a discourse of paternal choice. This discourse, which depicts paternal involvement as optional, positions fathers as secondary parents who ‘help’ with parenting work (Andreasson & Johansson, Citation2019), something that is only made possible when a mother (or someone else) assumes the primary responsibility for this work (Miller, Citation2010). This positioning has also been noted in relation to gay fathers (see for example, Andreasson & Johansson, Citation2017; Surtees, Citation2022). Manny’s status as a nonresident parent, and Wilson and Johan’s expected status as nonresident parents, makes it likely they will ‘help’ the women with ‘their’ work when visiting in their homes, rather than take full responsibility for the organization and management of their children’s daily care routines. As Wilson states, he and Johan expect “to visit regularly, to help out.” While over time these men might provide some care in their own homes without the women—perhaps akin to that provided by separated or divorced fathers—this had not been planned for in any detail. Presumably, such care will depend on the men’s other commitments, including paid work, as well as the age of the children and their articulation of what they want. The men’s assumption—that children need one home base and that this would be with the women—leaves intact the assumptions that mothers matter most and that paternal involvement is negotiable.

While divorce discourse framed these (and other) participants’ understandings about cross-residential fathering and parenting in the direction of paternal choice—arguably reinforcing fatherhood as a passive condition and diminishing possibilities for participation in care practices—not all of the known donors and their partners intended to leave the daily, residential work of rearing children to women. This was the case for partners Kole and Fraser, who were in the process of recruiting a lesbian couple to participate in a co-parenting dual residence arrangement with them. These kinds of arrangements between gay men and lesbians were seen by the men as a response to perceived flaws in the nuclear family form. In the following exchange, they utilize divorce discourse to reinforce their intended parenting status:

Fraser: Let’s start with the best-case [for fatherhood/parenthood]. It is really like a 50-50 [equal time split across their home and a lesbian couple’s home]. Or, we were thinking another arrangement could include—

Kole: Two kids.

Fraser: Two kids: one for each of us. One at our place, and one at their [the lesbian couple’s] place.

Kole: Because we don’t want to be just weekend dads.

Fraser: No.

Kole: That’s not really enough. I think we cannot really be a part of the kid’s life if we only see him on the weekends—that’s like uncles. It’s different…. The kid’s everyday life and important decisions, we would not always be a part of because we’d just be there at the weekend. No—and I really would like to do the nasty parts: changing nappies, burping the baby.

Just as divorcing or separating heterosexual men are forced to start planning for their parenting when they no longer occupy the same residence, the men introduced in this section along with other known donors and their partners in the study must actively plan for their fathering/parenting involvement. As they plan, they use what they know is sometimes the outcome for heterosexual men in the separation or divorce context, including models of mothers as primary caregivers and models of the weekend dad to shape what they consider acceptable. However, unlike separating or divorcing men whose parenting relationships are sustained when an intimate relationship has broken down, resolving issues about where their children will live or how they will care for them will not be complicated in the same way (Donovan, Citation2000). In sum, how the men practice parenting will be both like and unlike conventional ways of doing male parenting in a variety of circumstances, including when men are not co-resident with the mothers of their children. What separating heterosexual parents have developed and the Family Court has regulated via parenting ordersFootnote4 is a useful resource for them.

Discussion

The illustration of the wide-ranging use of divorce discourse as a kinship resource by the lesbian couples, known donors and donor partners in this study draws attention to some of the ways the normalization of divorce continues to influence contemporary families today. As explained in the introduction to this article, the familial configurations of these women and men are the result of pre-conception planning not changing circumstances. Their (planned) decision to disperse parenthood across relationships and households mirrors the (unplanned) dispersal of parenthood over new couple combinations and households in the post separation and divorce context. In starting at the juncture separated or divorced heterosexual parents find themselves at after the break down of the couple relationship, the participants must actively choose the kinds of connections and involvement they want to foster just as separating and divorcing parents must choose who to maintain connections and involvement with post separation and divorce.

Separation and divorce make explicit underlying assumptions about family and parenting. One such assumption that emerged in the stories the participants told is that mothers are more crucial to children’s upbringing than fathers—the conventions that pattern gendered heterosexual parenting scripts were generally accepted by them. The participants drew on this assumption in ways that prioritized the lesbian couples’ positions as mothers/parents over the known donors and their partners’ positions as fathers/parents consistent with many of the studies introduced earlier. For the most part, their children’s lives did or were expected to center around the lesbian couples as the primary parenting couple, thus privileging coupled parenting models even while their family boundaries remained relatively open. None of the known donors or their partners suggested they should provide the primary residential care of their planned or actual children in place of the lesbian couples, although Kole and Fraser aspired to an equitable shared parenting arrangement. In effect, this assumption, underpinned by a discourse of paternal choice and reinforced through separation and divorce patterns for nonresident fathers/parents, serve to support the kinds of fatherhood/parenthood the men imagine or have already established for themselves. In most cases, the forms of fatherhood/parenthood they chose allow them to limit traditionally feminized childrearing and domestic tasks to varying extents thereby reifying the existing gender order.

While the participants’ open family boundaries and dispersal of parenthood across relationships and households disrupts traditional parenting discourses and practices, their stories also highlight the ways in which actual or expected parenting practices are underpinned by a series of conventional solutions to the provision of care for children. As a resource, convention supports them as they move into unknown social territory. They chart this territory through their experimentation within a context with a lot of unpredictability. In this context, utilizing established heterosexual kinship conventions supports them to form and organize acceptable family lives while seeking social legitimation. Yet paradoxically, they also risk not reproducing these when negotiating the expectations of known donors and their partners with respect to their status of fathers/parents, even when these donors/partners are not the primary parents. Their familial configurations become less conventional and more innovative when known donors and their partners are actually involved in some parenting tasks and especially if parenting occurs across households.

Framed by heterosexual kinship conventions, the persistence of predominantly heterosexual understandings and practices across the participants’ stories—and the simultaneous disruption of them—speaks to Heaphy’s (Citation2018) observation of the double nature of contemporary family life. As he observes, same-sex families can be “simultaneously viewed as traditionally conventional and post-traditional and non-conventional” (p. 162, italics in original). To reiterate a point made in the introduction, in the absence of established models specific to their circumstances to guide them, the participants were left to figure out their interconnections and care arrangements themselves. Duncan and Carter (Citation2022) aptly note, “it is hard to start from scratch and make something new without using more or less trusted models from the past” (p. 53). Rather than ‘start from scratch’, the participants utilized separation and divorce politics and practices as a ‘trusted model’ as they negotiated possibilities for primary parenting responsibilities and ongoing known donor and donor partner sociality.

Limitations and future directions

While the research this article has drawn from fills a gap in knowledge about lesbian known donor reproduction, as a small qualitative study it has limitations. The study participants are unlikely to be a representative cross-section of the population of lesbians and gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand who are planning to or have already formed families together and/or with heterosexual women and men. The study cannot therefore provide information about the distribution or relative uptake of the different family relationships and forms of relatedness it documents. Nor can it compare experiences of lesbian known donor reproduction between participants of different ethnic, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds or by geographic location, given the participants were disproportionately Pākehā or of European descent. In conjunction with their relative socioeconomic privilege and urban habits, this suggests the study does not sufficiently reflect the experience of this form of reproduction among Māori, other ethnic and cultural minorities in Aotearoa New Zealand or those in lower income brackets or rural areas.

These limitations suggest more research on this topic with more people is needed and that increased attention to sampling and recruitment biases are warranted. Beyond these general suggestions, what the known donors and some of their partners in the study have to say about their status and place in the lives of future and current children indicates further studies are needed to explore ways to incorporate them, including possible frameworks or exemplars for achieving this.

Notes

1 Identity-release donors are donors whose identity is unknown to recipients at the time of donation, but who can become known to them and their children in the future under the provisions of the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (HART) Act 2004.

2 A total of 81 adults could potentially have participated, however not all adult members of the 21 familial configurations were available to participate.

3 The term used by Māori (the indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand) for a New Zealander of European descent.

4 Parenting orders specify responsibilities for day-to-day care of a child and when and how people who are not involved in daily care but are important in a child’s life can have contact (http://www.edenfamilylaw.co.nz/topics/care-of-children/.).

References

- Adams, M., & Coltrane, S. (2007). Framing divorce reform: Media, morality, and the politics of family. Family Process, 46(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00189.x

- Andreasson, J., & Johansson, T. (2017). It all starts now! Gay men and fatherhood in Sweden. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(5), 478–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2017.1308847

- Andreasson, J., & Johansson, T. (2019). Becoming a half-time parent: Fatherhood after divorce. Journal of Family Studies, 25(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1195277

- Berman, R., & Daneback, K. (2022). Children in dual-residence arrangements: A literature review. Journal of Family Studies, 28(4), 1448–1465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2020.1838317

- Blondell, D. (2023). Till death do us part: Laborers’ marriage practices in late Victorian New Zealand. Journal of Family History, 48(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/03631990221078588

- Bold, C. (2012). Using narrative in research. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288160

- Brown, M. L. (2021). The many looks of physical custody: A parenting plan for every situation. Family Advocate, 43(4), 1–4.

- Busch, R., Morgan, M., & Coombes, L. (2014). Manufacturing egalitarian injustice: A discursive analysis of the rhetorical strategies used in fathers’ rights websites in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Feminism & Psychology, 24(4), 440–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514539649

- Chisholm, D. (2016). Gene pull. New Zealand Listener, 254(3968), 15–21.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Côté, I., & Lavoie, K. (2019). A child wanted by two, conceived by several: Lesbian-parent families negotiating procreation with a known donor. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 15(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2018.1459216

- Côté, I., Lavoie, K., & de Montigny, F. (2020). Interpreting fatherhood after donation: Social representations and identity resonances among men having assisted a lesbian couple in becoming parents. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(3), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000246

- Dempsey, D. (2004). Donor, father or parent? Conceiving paternity in the Australian Family Court. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 18(1), 76–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/18.1.76

- Dempsey, D. (2005). Lesbians’ right to choose, children’s right to know. In H. G. Jones & M. Kirkman (Eds.), Sperm wars. The rights and wrongs of reproduction (pp. 185–195). ABC Books.

- Dempsey, D. (2012a). Gay male couples’ paternal involvement in lesbian-parented families. Journal of Family Studies, 18(2-3), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2012.18.2-3.155

- Dempsey, D. (2012b). More like a donor or more like a father? Gay men’s concepts of relatedness to children. Sexualities, 15(2), 156–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711433735

- DiFonzo, J. H. (2014). From the rule of one to shared parenting: Custody presumptions in law and policy. Family Court Review, 52(2), 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12086

- Donovan, C. (2000). Who needs a father? Negotiating biological fatherhood in British lesbian families using self-insemination. Sexualities, 3(2), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346000003002003

- Duncan, S., & Carter, J. (2022). Understanding personal lives: After individualisation. In S. Quaid, C. Hugman, & A. Wilcock (Eds.), Negotiating families and personal lives in the 21st Century: Exploring diversity, social change and inequalities (pp. 46–60). Routledge.

- Fahey, T. (2014). Divorce trends and patterns: An overview. In J. Eekelaar & R. George (Eds.), Routledge handbook of family law and policy (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Fannery, M. T. (2004). Is ‘bird nesting’ in the best interest of children? SMU Law Review, 57(2), 295.

- Fertility Associates. (n.d). Waitlist for donor sperm. https://www.fertilityassociates.co.nz/treatment-options/donor-options-and-surrogacy/donor-sperm-waitlist/

- Fine, M. A., & Fine, D. R. (1994). An examination and evaluation of recent changes in divorce laws in five western countries: The critical role of values. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56(2), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/353098

- Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2015). How to design and evaluate research in education (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Gahan, L. (2019). Separation and post-separation parenting within lesbian and gay co-parenting (guild parented) families. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1343

- Goldberg, A. E., & Allen, K. (2013). Donor, dad, or…? Young adults with lesbian parents’ experiences with known donors. Family Process, 52(2), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12029

- Goldberg, A. E., & Scheib, J. E. (2016). Female-partnered women conceiving kinship: Does sharing a sperm donor mean we are family? Journal of Lesbian Studies, 20(3-4), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1089382

- Graf, T. E., & Wojnicka, K. (2021). Post-separation fatherhood narratives in Germany and Sweden: Between caring and protective masculinities. Journal of Family Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2021.2020148

- Gray, D. E. (2018). Doing research in the real world (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Gregory, A., & Milner, S. (2011). What is ‘‘new’’ about fatherhood?: The social construction of fatherhood in France and the UK. Men and Masculinities, 14(5), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X11412940

- Haimes, E., & Weiner, K. (2000). ‘Everybody’s got a dad…’: Issues for lesbian families in the management of donor insemination. Sociology of Health & Illness, 22(4), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00215

- Hakovirta, M., Meyer, D. R., & Skinner, C. (2022). Child support in shared care cases: Do child support policies in thirteen countries reflect family policy models? Social Policy & Society, 21(4), 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000300

- Hakovirta, M., & Skinner, C. (2021). Shared physical custody and child maintenance arrangements: A comparative analysis of 13 countries using a model family approach. In L. Bernardi & D. Mortelmans (Eds.), Shared physical custody: Interdisciplinary insights in child custody arrangements (pp. 309–331). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68479-2

- Hayman, B., Wilkes, L., Halcomb, E., & Jackson, D. (2014). Lesbian women choosing motherhood: The journey to conception. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.921801

- Heaphy, B. (2018). Troubling traditional and conventional families? Formalised same-sex couples and ‘the ordinary. Sociological Research Online, 23(1), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418754779

- Herbrand, C. (2017). Co-parenting arrangements in lesbian and gay families: When the ‘mum and dad’ ideal generates innovative family forms. Families, Relationships and Societies, 7(3), 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674317X14888886530269

- Kelly, F. J. (2011). Transforming law’s family: The legal recognition of planned lesbian motherhood. The University of British Columbia Press.

- Kelly, J. B. (2005). Developing beneficial parenting plan models for children following separation and divorce. Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, 19(2), 237–254.

- Leclair, V., St-Amand, A., & Bussières, È. (2021). Association between child custody and postseparation coparenting: A meta-analysis. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 60(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000140

- Luce, J. (2010). Beyond expectation. Lesbian/bi/queer women and assisted conception. University of Toronto Press Incorporated.

- MacKenzie, D., Herbert, R., & Robertson, N. (2020). It’s not ok’, but ‘it’ never happened: Parental alienation accusations undermine children’s safety in the New Zealand Family Court. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 42(1), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2020.1701942

- Markham, M. S., Hartenstein, J. L., Mitchell, Y. T., & Aljayyousi-Khalil, G. (2017). Communication among parents who share physical custody after divorce or separation. Journal of Family Issues, 38(10), 1414–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15616848

- McNair, R., Dempsey, D., Wise, S., & Perlesz, A. (2002). Lesbian parenting: Issues, strengths and challenges. Family Matters, 63, 40–49.

- Miller, T. (2010). It’s a triangle that’s difficult to square": Men’s intentions and practices around caring, work and first-time fatherhood. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, & Practice about Men as Fathers, 8(3), 362–378.

- Morgan, D. H. J. (1996). Family connections: An introduction to family studies. Polity Press.

- Nordqvist, P. (2012). Origin and originators: Lesbian couples negotiating parental identities and sperm donor conception. Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care, 14(3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.639392

- Nordqvist, P. (2019). Un/familiar connections: On the relevance of a sociology of personal life for exploring egg and sperm donation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(3), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12862

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Phillips, R. (1981). Divorce in New Zealand: A social history. Oxford University Press.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Riggs, D. (2018). Making matter matter: Meanings accorded to genetic material among Australian gay men. Reproductive BioMedicine & Society Online, 7, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2018.06.002

- Riggs, D. W. (2008a). Lesbian mothers, gay sperm donors, and community: Ensuring the well-being of children and families. Health Sociology Review, 17(3), 226–234. <Go to ISI>://000261050200002

- Riggs, D. W. (2008b). Using multinomial logistic regression analysis to develop a model of Australian gay and heterosexual sperm donors’ motivations and beliefs. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 6(2), 106–123.

- Righarts, A. A., Dickson, N. P., Parkin, L., & Gillett, W. R. (2015). Infertility and outcomes for infertile women in Otago and Southland. New Zealand Medical Association, 128(1425), 43–53.

- Ripper, M. (2008). Australian sperm donors: Public image and private motives of gay, bisexual and heterosexual donors. Health Sociology Review, 17(3), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.451.17.3.313

- Ripper, M. (2009). Lesbian parenting through donor insemination: Implications for the hetero-normative family. Gay & Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review, 5(2), 81–93.

- Ryan-Flood, R. (2005). Contested heteronormativities: Discourses of fatherhood among lesbian parents in Sweden and Ireland. Sexualities, 8(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460705050854

- Scholz, B., & Riggs, D. W. (2013). Sperm donors’ accounts of lesbian recipients: Heterosexualisation as a tool for warranting claims to children’s ‘best interests. Psychology & Sexuality, 5(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.764921

- Smart, C. (2004). Changing landscapes of family life: Rethinking divorce. Social Policy and Society, 3(4), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746404002040

- Smart, C. (2007). Personal life: New directions in sociological thinking. Polity Press.

- Smart, C. (2010). Disciplined writing: On the problem of writing sociologically (Working Paper No. 13). University of Manchester. http://www.socialsciences.manchester.ac.uk/medialibrary/morgancentre/research/wps/13-2010-01-realities-disciplined-writing.pdf

- Smart, C. (2011). Relationality and socio-cultural theories of family life. In R. Jallinoja & E. D. Widmer (Eds.), Families and kinship in contemporary Europe. Rules and practices of relatedness (pp. 13–28). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

- Smart, C., & Neale, B. (1999). I hadn’t really thought about it’: New identities/new fatherhoods. In J. Seymour & P. Bagguley (Eds.), Relating intimacies: Power and resistance (pp. 118–141). Macmillan Press.

- Sparkes, A. C. (2005). Narrative analysis: Exploring the whats and hows of personal stories. In I. Holloway (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 191–209). Open University Press.

- Stacey, J. (1996). In the name of the family: Rethinking family values in the post-modern age. Beacon Press.

- Stevens, E. (2015). Understanding discursive barriers to involved fatherhood: The case of Australian stay-at-home fathers. Journal of Family Studies, 21(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1020989

- Surtees, N. (2011). Family law in New Zealand: The benefits and costs for gay men, lesbians, and their children. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7(3), 245–263.

- Surtees, N. (2017). Narrating connections and boundaries: Constructing relatedness in lesbian known donor familial configurations. University of Canterbury.

- Surtees, N. (2022). Constructing gay fatherhood in known donor-lesbian reproduction: “We get to live that life, we get to be parents. In R. M. Shaw (Ed.), Reproductive citizenship: Technologies, rights and relationships (pp. 253–277). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Surtees, N., & Bremner, P. (2020). Gay and lesbian collaborative co-parenting in New Zealand and the United Kingdom: “The law doesn’t protect the third parent. Social & Legal Studies, 29(4), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663919874861

- Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. L. (2016). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Weston, K. (1991). Families we choose: Lesbians, gays, kinship. Columbia University Press.