Abstract

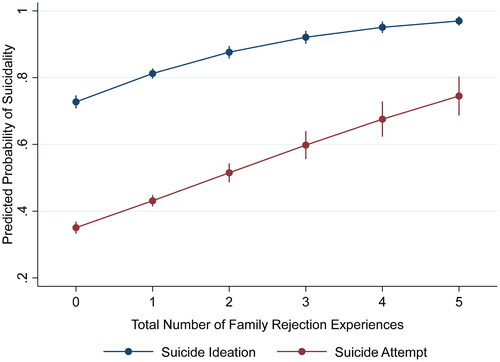

We evaluate the association of familial factors and suicidality among transgender adults in the U.S. by estimating the odds of lifetime suicide ideation and attempt using the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Predictors include family support, family rejection, and specific experiences related to both. About 79% of sample respondents have experienced suicidal ideation and nearly 43% have made a suicide attempt. The predicted probability of suicide attempt is 0.35 for those with no family rejection experiences, 0.75 for those who have had all five experiences in our models. Rejection predicts both outcomes and experiences of rejection have a cumulative impact.

Keywords:

Introduction

Transgender and non-binary (TNB) individuals are at higher risk of adverse mental health outcomes than the cisgender population, including suicidal ideation and attempt (Cramer et al., Citation2022; Haas et al., 2011, Haas et al., Citation2014; Herman et al., Citation2019), even when compared to cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals (Carmel & Erickson-Schroth, Citation2016; Connolly et al., Citation2016; Reisner et al., Citation2015). According to the estimates presented in the Executive Summary of the United States Transgender Survey (USTS), 82% of their TNB sample have considered suicide and 40% have attempted suicide (James et al., Citation2016) compared to 4.3% of Americans who had suicidal thoughts and 0.6% that attempted suicide in the last year (Ivey-Stephenson et al., Citation2022). The extreme disparities in suicidality among TNB people are associated with adverse social experiences both at the interpersonal and structural level (Bradford et al., Citation2013; Grant et al., Citation2011), and can be understood under minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003). According to this framework, stressors associated with a minority social identity, including discrimination, prejudice, and various forms of violence (Meyer et al., Citation2021) are associated with negative health outcomes, including poor mental health (Meyer, Citation2003).

There is an association between TNB-based stressors and suicidality in teens, young adults (Hendricks & Testa, Citation2012; Toomey et al., Citation2018; Veale et al., Citation2017), and adults in general (Testa et al., Citation2017). Unlike other minoritized identities such as being a person of color or having a lower socioeconomic status, TNB individuals seldom have a family member that shares their TNB status, which denies them immediate support from individuals who have navigated similar circumstances (Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Thoits, Citation2011). TNB individuals are also less likely to have supportive and affirming family relationships (Eisenberg et al., Citation2017; Lefevor et al., Citation2019; Pflum et al., Citation2015), and a large segment of TNB individuals experience outright family rejection (Factor & Rothblum, Citation2007; Graham et al., Citation2014; Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Koken et al., Citation2009; Pflum et al., Citation2015), potentially compounding the risk of poor mental health leading up to suicidal ideation and attempt. However, recent research on transgender youth shows that supportive environments (e.g., family support, gender-affirming medical care, pronoun use) can significantly reduce the likelihood of suicide-related outcomes (Olson et al., Citation2016; Olson-Kennedy et al., Citation2019; Pollitt et al., Citation2021; Russell et al., Citation2018).

Considering this, we explore the association of family support and rejection with suicidality among TNB adults in the United States using the largest dataset of TNB individuals available thus far, the 2015 United States Transgender Survey (USTS) (James et al., Citation2019). We make three significant contributions to the literature on TNB mental health and its association with interpersonal family relationships. According to our findings, 1) experiencing rejection in the family unit has a cumulative effect; as negative experiences of rejection increase, so does the probability of suicidality; 2) however, even when respondents had zero experiences of rejection, the probability of suicidal ideation and attempt is extremely high; and, 3) although our predictive models show a statistically significant reduction in the likelihood of suicidality when respondents claimed to have a supportive family, particular instances of support were not statistically significant. This speaks of complex patterns in family relationships when a family member is TNB and their association with mental health, rather than a clear-cut, straightforward link between family support and lower suicidality. It is likely that family support alone is insufficient to safeguard TNB individuals from adverse mental health outcomes because marginalization in the broader social structure might outweigh that support.

Challenges to TNB Mental Health

TNB individuals experience significant structural and interpersonal challenges which are potential risk factors for poor mental health. To illustrate structural matters, TNB individuals face significant socioeconomic inequality. TNB individuals are less likely to have attended and graduated from college, and are less likely to have a higher socioeconomic status than cisgender respondents (Meyer et al., Citation2017). They are less likely to have work opportunities and more likely to live in poverty (Crissman et al., Citation2017; Meyer et al., Citation2017). An examination of the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data also found significantly lower employment rates and lower wages among transgender people compared to cisgender respondents (Ciprikis et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, TNB individuals are more likely to experience workplace discrimination (Suárez et al., Citation2022), hostile workplace environments (Rudin et al., Citation2014), exclusionary gendered spaces, lack of protective policies (Brewster et al., Citation2014), and unequal workers’ rights (Dietert & Dentice, Citation2009, Citation2015).

Besides the countless structural challenges TNB individuals encounter, it is important to consider interpersonal family dynamics vis-à-vis diverse forms of gender expression and their effects on mental health. Much of this literature focuses on transgender youth and young adults, the group at highest risk (Bauer et al., Citation2015; Clements-Nolle et al., Citation2006; Grossman et al., Citation2016; James et al., Citation2016; Tebbe et al., Citation2016), and it suggests that family support and acceptance play a protective role in suicide-related outcomes (Bouris & Hill, Citation2017; Katz-Wise et al., Citation2018; Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Moody & Smith, Citation2013; Olson et al., Citation2016; Russell et al., Citation2018). Additionally, parental support has been associated with lower perceived burden of trans identity, fewer symptoms of depression, greater quality of life (Simons et al., Citation2013), lower odds of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (Wilson et al., Citation2016), and has a strong negative association with psychological distress (Lefevor et al., Citation2019). Family support is also associated with higher levels of self-esteem, sexual self-efficacy (Stotzer, Citation2011), safe sex practices (Wilson et al., Citation2012, Citation2016), a general sense of wellbeing (Budge et al., Citation2018), life satisfaction (Schimmel-Bristow et al., Citation2018), and better mental health overall (Simons et al., Citation2013).

On the contrary, family rejection increases the risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression (Yadegarfard et al., Citation2014), substance use (Klein & Golub, Citation2016), self-harm (Grossman & D’Augelli, Citation2007; Veale et al., Citation2017), and suicidality (Bariola et al., Citation2015; Grossman & D’Augelli, Citation2007; James et al., Citation2016; Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Olson et al., Citation2016; Simons et al., Citation2013). Family rejection has broad detrimental effects for a myriad of reasons. First, rejection becomes a material stressor in itself, which can result in economic insecurity (Klein & Golub, Citation2016), housing insecurity (Glick et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), homelessness (Shelton & Bond, Citation2017), food insecurity (Russomanno et al., Citation2019; Russomanno & Jabson Tree, Citation2020), and a lack of access to transition-related healthcare services (Koch et al., Citation2020; White Hughto et al., Citation2017). The latter are in themselves pivotal to good physical and mental health outcomes (Dickey & Budge, Citation2020). Family rejection also has important psychosocial consequences. Rejection might affect resilience and coping as TNB individuals lose the protective buffering effects associated with social support (Thoits, Citation2011; Uchino et al., Citation1996). Rejection leads to emotional and physical distance between TNB individuals and their families. This disconnect fosters feelings of not belonging in their family, being a burden, and hopelessness (Grossman et al., Citation2016). Rejection by family members can also lead to thinking they would be better off dead, as postulated in the interpersonal theory of suicide (Grossman et al., Citation2016; Van Orden et al., Citation2010).

Previous research highlights a greater need to further examine family relations and mental health outcomes among TNB adults as this literature is scarce in relation to studies among TNB youth (Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Meyer et al., Citation2021). To that end, the purpose of this study is to explore how family support and rejection impact suicidality in transgender adults. In the following section, we discuss our analytic approach.

Materials and Methods

Data

We use the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, a restricted dataset with a sample of 27,715 respondents in the U.S. The USTS was administered online by the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE); the dataset has been archived at the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan since 2019. In order to assess inequalities between transgender and cisgender people, the questionnaire included many items used in large, federal surveys. The USTS has thirty-two sections and documents the experiences of transgender individuals in a broad range of subjects and settings (James et al., Citation2019). Despite its non-probability sample, the USTS is the largest survey of transgender individuals in the United States to date (James et al., Citation2016).

Variables of Interest & Analysis

The outcome variables of this study are lifetime suicide ideation and attempt. Respondents were asked, “At any time in your life, have you seriously thought about trying to kill yourself?” and “At any time in your life, did you try to kill yourself?” The responses are coded as dichotomous variables (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Thus, analysis consisted of logistic regression models estimated using Stata 17 (StataCorp, Citation2021).

The review of literature provided guidance in the choice of independent variables to include in the analysis. In the first set of models, our main independent variable is perceived family support, a categorical variable coded (1) supportive, (2) neutral, and (3) unsupportive. In the second set of models, we estimated the effects of family rejection experiences (dichotomous; no/yes) in both outcomes. The original question was “Did any of your family members you grew up with (mother, father, sisters, brothers, etc.) do any of these things to you because you are trans?” Answers included, (1) stopped speaking to you for a long time or ended your relationship; (2) were violent toward you; (3) kicked you out of the house; (4) did not allow you to wear the clothes that matched your gender; and (5) family sent you to a therapist, counselor, or religious advisor to stop you from being trans. In preliminary analysis, we estimated the effects of supportive experiences (i.e., told you that they respect and/or support you, used your preferred name, used your correct pronouns, etc.) but they did not reach statistical significance and were omitted from the final analysis. This is consistent with previous studies that did not find family support to have a significant buffering effect in relation to mental health outcomes (Craig & Smith, Citation2014; Meyer et al., Citation2021).

Demographic covariates in the models include gender identity (transgender woman, transgender man, and nonbinary/gender queer); race/ethnicity (white, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian American, Black or African American, Latinx, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Biracial or Multiracial), age (18-24, 25-44, 45-64, and 65+) and marital status (married or cohabiting, never married, divorced, and widowed). We also controlled for two socioeconomic measures, education (less than high school, high school, some college, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, and graduate or professional degree) and unemployment (no/yes). We omitted income from final models due to multicollinearity issues. Lastly, we excluded respondents with missing data for the variables of interest.

Results

displays the weighted percentage distributions for dependent and independent variables. Seventy nine percent of USTS respondents in our subsample have thought seriously about suicide, and nearly 43% have made a suicide attempt. The majority of respondents (60%) reported having supportive families, and the prevalence of family rejection experiences range from 9.50% for being kicked out of the house to 33.25% for family members not speaking or ending relationships.

Table 1. Weighted descriptive statistics of sample respondents (N = 19,829).

displays the results of logistic regression models for suicide ideation and suicide attempt and perceived family support, expressed as odds ratios. In baseline models, respondents with supportive families are less likely to have reported suicide ideation or attempt than those with neutral families (OR = 0.688, p<.01; OR=.837, p<.05), and respondents with unsupportive families are more likely to have reported suicide ideation or attempt than those with neutral families (OR = 1.447, p<.05; OR = 1.374, p<.01). After controlling for sociodemographic covariates (gender identity, race/ethnicity, age, and marital status), the same associations hold. In final models, after adding socioeconomic status covariates, respondents with perceived unsupportive families are more likely to have experienced suicide ideation and attempt compared to those with neutral families (OR = 1.478; p<.01; OR = 1.369, p<.01). Respondents with perceived supportive families remain significantly less likely to report suicide ideation than those with neutral families (OR=.717, p<.01); however, having a supportive family does not significantly differ from having a neutral family for suicide attempt.

Table 2. Logistic regression models of suicide ideation and suicide attempt and family support expressed in odds ratios.

Among covariates, transgender men are more likely to report suicide ideation and attempt, compared to nonbinary/gender queer individuals (OR = 1.364, p<.01; OR = 1.464, p<.001). American Indian/Alaskan Natives, and Biracial or Multiracial individuals were more likely to report ideation and attempt, compared to white individuals. Middle Eastern or North African individuals were more likely to report suicide ideation and Black or African American individuals were less likely to report ideation than white individuals. Compared to 18-24 year olds, all age groups reported less suicide ideation; however, 25-44 year olds were more likely to report suicide attempt than 18-24 year olds. Finally, all education groups were less likely to report suicide attempt than those with less than a high school diploma, and unemployed individuals were more likely to report suicide ideation and attempt.

displays the results of logistic regression models for suicide ideation and suicide attempt and perceived family rejection, expressed as odds ratios. In baseline models, respondents who reported that family members 1) stopped speaking to them or ended relationships, 2) were violent toward them, 3) kicked them out of the house, and 4) didn’t allow clothing that matched their gender identity were significantly more likely to have experienced suicide ideation (OR = 1.507, p<.001; OR = 3.087, p<.001; OR = 2.054, p<.001; OR = 1.490, p<.001) and attempt (OR = 1.622, p<.001; OR = 1.605, p<.001; OR = 1.648, p<.001; OR = 1.397, p<.001). The same associations held after introducing sociodemographic and socioeconomic covariates. In final models, having a family member stop speaking or end a relationship was associated with nearly two times the odds of reporting suicide ideation (OR = 1.810, p<.001). TNB individuals who had been kicked out of their house had over two times the odds of reporting suicide ideation (OR = 2.155, p<.001), and having family act violently was associated with over three times the odds of reporting suicide ideation (OR = 3.127, p<.001). These family rejection experiences were significantly associated with suicide attempt as well. For example, TNB individuals who reported that family members stopped speaking to them or kicked them out of their house had nearly two times the odds of reporting suicide attempt (OR = 1.742, p<.001; OR = 1.607, p<.01). Covariates in this model had similar associations as reported in .

Table 3. Logistic regression models of suicide ideation and suicide attempt and family rejection expressed in odds ratios.

Together, family rejection experiences significantly predict higher likelihood of suicide ideation and attempt. As seen in , the cumulative impact of family rejection experiences results in a higher likelihood of suicide ideation and attempt. For suicide ideation, the predicted probability of ideation for a TNB person reporting zero family rejection experiences is 0.72; however, the predicted probability of ideation when reporting all five types of family rejection is 0.97. The cumulative association for suicide attempt is even more concerning. A TNB person reporting zero family rejection experiences has a predicted probability of 0.35, compared to 0.75 when experiencing all five family rejection experiences, for suicide attempt.

Discussion

According to demographic estimates, there are 1.4 million transgender adults (18+) in the U.S, making up approximately 0.5-0.7% of the total population (Flores et al., Citation2016; Gates, Citation2015; Meerwijk & Sevelius, Citation2017; Meyer et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the number of Americans identifying as LGBTQ+ has increased in recent years, particularly among younger cohorts (Gates, Citation2015; Jones, Citation2021; Meerwijk & Sevelius, Citation2017), and the number of people who identify as transgender grows in magnitude every year (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2017; Meerwijk & Sevelius, Citation2017). The growth in this population and their enormous disparities in mental health merit in-depth research of the factors contributing to adverse mental health outcomes at both structural and interpersonal levels.

We contribute to the literature by examining how stigmatization experiences from close interpersonal relationships (i.e., family), influence suicide ideation and attempt. In doing so, we are responding to other researchers’ call to expand on this subject among TNB adults (Klein & Golub, Citation2016; Meyer et al., Citation2021). We have effectively quantified the extent in which familial experiences are pivotal for TNB individuals’ mental health notwithstanding significant structural discrimination. Suicidal ideation and attempt are high even when they had zero family rejection experiences (predicted probabilities = 0.72 and 0.35, respectively). The unexplained dimension in our models most likely stems from structural discrimination and other forms of interpersonal stigmatization. By testing family rejection measures, we observe that suicide ideation and attempt increase substantially when experienced in multiple forms (i.e., doubling the probability of suicide attempts), showing that families have an integral role in fostering mental health for TNB individuals even when specific forms of support were not significant. Furthermore, we argue family support although important it is also likely not enough to safeguard TNB family members’ mental health in the face of major systemic barriers they encounter in society. Multi-pronged support structures for TNB individuals and their families would likely yield improved outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the USTS prevents us from establishing causality. We can only ascertain an association. Second, we did not include measures on the timing of suicidal behaviors. Instead, we take a life-course approach and argue that regardless of timing, cumulative experiences of family rejection in addition to broader social marginalization, can have lifelong reverberations in TNB mental health (O’Rand, Citation1996; Willson et al., Citation2007). In expanding this line of inquiry, researchers can explore the association of TNB mental health and relationships with specific family members (e.g., mother), how mixed family reactions influence mental health, and a deeper exploration of family life among TNB adults is also warranted.

Our hope is that increased recognition of the familial factors that influence TNB mental health leads to creating interventions and structures of support for TNB individuals and their families. Having a TNB family member affects the entire family unit (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2017), and ideally, interventions would consider families as well. This is particularly relevant to the current national conversation about transgender children/youth, as state legislatures across the nation either have considered or passed laws criminalizing parents or guardians who affirm their transgender children or seek to ban transgender individuals from certain social spaces (Dey, Citation2022; Ghorayshi, Citation2022). We cannot rely solely on improvements in public opinion to turn the tide in terms of TNB mental health. In a recent national sample, 42% of respondents claimed to know a transgender person, a five percent increase since 2017 (Minkin & Brown, Citation2021). Despite this increase in recognition, attitudes toward TNB individuals have remained stagnant. For instance, 56% of U.S. adults believe sex assigned at birth determines if someone is a man or a woman while only 41% believe gender can differ from sex assigned at birth. These figures remained virtually unchanged since 2017 (Minkin & Brown, Citation2021). Thus, increased awareness is not necessarily a reflection of more societal acceptance, and this shapes the response toward TNB individuals and family members, in turn influencing their mental health. In order to curtail the massive mental health disparities observed among the TNB population, we need to create the conditions, both institutionally and interpersonally, to save countless TNB lives.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) for their support during the acquisition of the USTS dataset. We thank the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) for their data collection efforts.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article is restricted and archived at ICPSR. James, SE, Herman, J, Keisling, M, Mottet, L, and Anafi, M. (2019). U.S. Transgender

Survey. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37229.v1.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bariola, E., Lyons, A., Leonard, W., Pitts, M., Badcock, P., & Couch, M. (2015). Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with psychological distress and resilience among transgender individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2108–2116. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302763

- Bauer, G. R., Scheim, A. I., Pyne, J., Travers, R., & Hammond, R. (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2

- Bouris, A., & Hill, B. J. (2017). Exploring the mother–adolescent relationship as a promotive resource for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 618–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12234

- Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. A., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796

- Brewster, M. E., Velez, B. L., Mennicke, A., & Tebbe, E. (2014). Voices from beyond: A thematic content analysis of transgender employees’ workplace experiences. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000030

- Budge, S. L., Belcourt, S., Conniff, J., Parks, R. W., Pantalone, D., & Katz-Wise, S. L. (2018). A grounded theory study of the development of trans youths’ awareness of coping with gender identity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(9), 3048–3061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1136-y

- Carmel, T. C., & Erickson-Schroth, L. (2016). Mental health and the transgender population. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 54(12), 44–48. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20161208-09

- Ciprikis, K., Cassells, D., & Berrill, J. (2020). Transgender labour market outcomes: Evidence from the United States. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6), 1378–1401. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12501

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n03_04

- Connolly, M. D., Zervos, M. J., Barone, C. J., II, Johnson, C. C., & Joseph, C. L. (2016). The mental health of transgender youth: Advances in understanding. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012

- Craig, S. L., & Smith, M. S. (2014). The impact of perceived discrimination and social support on the school performance of multiethnic sexual minority youth. Youth & Society, 46(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X11424915

- Cramer, R. J., Kaniuka, A. R., Yada, F. N., Diaz-Garelli, F., Hill, R. M., Bowling, J., Macchia, J. M., & Tucker, R. P. (2022). An analysis of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender and gender diverse adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(1), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02115-8

- Crissman, H. P., Berger, M. B., Graham, L. F., & Dalton, V. K. (2017). Transgender demographics: A household probability sample of US adults, 2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 213–215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303571

- Dey, S. (2022, March 1). Texas investigates parents of transgender teen, prompting the ACLU to sue. The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/2022/03/01/transgender-child-lawsuit-abbott/

- Dickey, L. M., & Budge, S. L. (2020). Suicide and the transgender experience: A public health crisis. American Psychologist, 75(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000619

- Dietert, M., & Dentice, D. (2009). Gender identity issues and workplace discrimination: The transgender experience. Journal of Workplace Rights, 14(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.2190/WR.14.1.g

- Dietert, M., & Dentice, D. (2015). The transgender military experience: Their battle for workplace rights. SAGE Open, 5(2), 215824401558423–215824401558412. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015584231

- Eisenberg, M. E., Gower, A. L., McMorris, B. J., Rider, G. N., Shea, G., & Coleman, E. (2017). Risk and protective factors in the lives of transgender/gender nonconforming adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.04.014

- Factor, R. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (2007). A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3(3), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15574090802092879

- Flores, A. R., Herman, J. L., Gates, G. J., & Brown, T. N. T. (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

- Gates, G. (2015). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender demographics. In W. Swan (Ed.), Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender civil rights: A public policy agenda for uniting a divided America, pp. 1–20). Routledge.

- Ghorayshi, A. (2022, February 23). Texas governor pushes to investigate medical treatments for trans youth as ‘child abuse’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/23/science/texas-abbott-transgender-child-abuse.html

- Glick, J. L., Lopez, A., Pollock, M., & Theall, K. P. (2019). “Housing insecurity seems to almost go hand in hand with being trans”: Housing stress among transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in New Orleans. Journal of Urban Health, 96(5), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00384-y

- Glick, J. L., Lopez, A., Pollock, M., & Theall, K. P. (2020). Housing insecurity and intersecting social determinants of health among transgender people in the USA: A targeted ethnography. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(3), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1780661

- Graham, L. F., Crissman, H. P., Tocco, J., Hughes, L. A., Snow, R. C., & Padilla, M. B. (2014). Interpersonal relationships and social support in transitioning narratives of Black transgender women in Detroit. International Journal of Transgenderism, 15(2), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2014.937042

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. The National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf

- Grossman, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(5), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527

- Grossman, A. H., Park, J. Y., & Russell, S. T. (2016). Transgender youth and suicidal behaviors: Applying the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527

- Haas, A. P., Eliason, M., Mays, V. M., Mathy, R. M., Cochran, S. D., D’Augelli, A. R., Silverman, M. M., Fisher, P. W., Hughes, T., Rosario, M., Russell, S. T., Malley, E., Reed, J., Litts, D. A., Haller, E., Sell, R. L., Remafedi, G., Bradford, J., Beautrais, A. L., … Clayton, P. J. (2011). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 10–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038

- Haas, A. P., Rodgers, P. L., & Herman, J. L. (2014). Suicide attempts among transgender and gender non-conforming adults: Finding of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-GNC-Suicide-Attempts-Jan-2014.pdf.

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597

- Herman, J. L., Brown, T. N., & Haas, A. P. (2019). Suicide thoughts and attempts among transgender adults: Findings from the 2015 US Transgender Survey. Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Suicidality-Transgender-Sep-2019.pdf.

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Crosby, A. E., Hoenig, J. M., Gyawali, S., Park-Lee, E., & Hedden, S. L. (2022). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2015–2019. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 71(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7101a1

- James, S. E., Herman, J., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2019). U.S. Transgender Survey. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37229.v1

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). Executive summary of the report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Executive-Summary-Dec17.pdf

- Jones, J. M. (2021, February 24). LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest US estimate. Gallup News. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Budge, S. L., Fugate, E., Flanagan, K., Touloumtzis, C., Rood, B., Perez-Brumer, A., & Leibowitz, S. (2017). Transactional pathways of transgender identity development in transgender and gender-nonconforming youth and caregiver perspectives from the Trans Youth Family Study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1304312

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Ehrensaft, D., Vetters, R., Forcier, M., & Austin, S. B. (2018). Family functioning and mental health of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth in the trans teen and family narratives project. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1415291

- Klein, A., & Golub, S. A. (2016). Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT Health, 3(3), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2015.0111

- Koch, J. M., McLachlan, C. T., Victor, C. J., Westcott, J., & Yager, C. (2020). The cost of being transgender: Where socio-economic status, global health care systems, and gender identity intersect. Psychology & Sexuality, 11(1–2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1660705

- Koken, J. A., Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2009). Experiences of familial acceptance–rejection among transwomen of color. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(6), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017198

- Lefevor, G. T., Sprague, B. M., Boyd-Rogers, C. C., & Smack, A. C. (2019). How well do various types of support buffer psychological distress among transgender and gender nonconforming students? International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1452172

- Meerwijk, E. L., & Sevelius, J. M. (2017). Transgender population size in the United States: A meta-regression of population-based probability samples. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Meyer, I. H., Brown, T. N., Herman, J. L., Reisner, S. L., & Bockting, W. O. (2017). Demographic characteristics and health status of transgender adults in select US regions: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(4), 582–589. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303648

- Meyer, I. H., Russell, S. T., Hammack, P. L., Frost, D. M., & Wilson, B. D. (2021). Minority stress, distress, and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: A US probability sample. Plos One, 16(3), e0246827. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246827

- Minkin, R., & Brown, A. (2021). Rising shares of U.S. adults know someone who is transgender or goes by gender-neutral pronouns. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/07/27/rising-shares-of-u-s-adults-know-someone-who-is-transgender-or-goes-by-gender-neutral-pronouns/

- Moody, C., & Smith, N. G. (2013). Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(5), 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0099-8

- Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223

- Olson-Kennedy, J., Chan, Y.-M., Garofalo, R., Spack, N., Chen, D., Clark, L., Ehrensaft, D., Hidalgo, M., Tishelman, A., & Rosenthal, S. (2019). Impact of early medical treatment for transgender youth: protocol for the longitudinal, observational trans youth care study. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(7), e14434. https://doi.org/10.2196/14434

- O’Rand, A. M. (1996). The precious and the precocious: Understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. The Gerontologist, 36(2), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/36.2.230

- Pflum, S. R., Testa, R. J., Balsam, K. F., Goldblum, P. B., & Bongar, B. (2015). Social support, trans community connectedness, and mental health symptoms among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000122

- Pollitt, A. M., Ioverno, S., Russell, S. T., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2021). Predictors and mental health benefits of chosen name use among transgender youth. Youth & Society, 53(2), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X19855898

- Reisner, S. L., Vetters, R., Leclerc, M., Zaslow, S., Wolfrum, S., Shumer, D., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2015). Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: A matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264

- Rudin, J., Ruane, S., Ross, L., Farro, A., & Billing, T. (2014). Hostile territory: Employers’ unwillingness to accommodate transgender employees. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 33(8), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-12-2013-0116

- Russell, S. T., Pollitt, A. M., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2018). Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(4), 503–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003

- Russomanno, J., Patterson, J. G., & Jabson, J. M. (2019). Food insecurity among transgender and gender nonconforming individuals in the Southeast United States: A qualitative study. Transgender Health, 4(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0024

- Russomanno, J., & Jabson Tree, J. M. (2020). Food insecurity and food pantry use among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the Southeast United States. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08684-8

- Schimmel-Bristow, A., Haley, S. G., Crouch, J. M., Evans, Y. N., Ahrens, K. R., McCarty, C. A., & Inwards-Breland, D. J. (2018). Youth and caregiver experiences of gender identity transition: A qualitative study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000269

- Shelton, J., & Bond, L. (2017). “It just never worked out”: How transgender and gender expansive youth understand their pathways into homelessness. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 98(4), 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2017.98.33

- Simons, L., Schrager, S. M., Clark, L. F., Belzer, M., & Olson, J. (2013). Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 791–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.019

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata Statistical Software: Release 17.

- Stotzer, R. L. (2011). Family cohesion among Hawai’i’s Māhūwahine. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7(5), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2011.623935

- Suárez, M. I., Marquez-Velarde, G., Glass, C., & Miller, G. H. (2022). Cis-normativity at work: Exploring discrimination against US trans workers. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 37(6), 716–731. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-06-2020-0201

- Tebbe, E. A., Moradi, B., Tebbe, E. A., & Moradi, B. (2016). Suicide risk in trans populations: An application of minority stress theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000152

- Testa, R. J., Michaels, M. S., Bliss, W., Rogers, M. L., Balsam, K. F., & Joiner, T. (2017). Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000234

- Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

- Toomey, R. B., Syvertsen, A. K., & Shramko, M. (2018). Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218

- Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 488–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E.Jr, (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

- Veale, J. F., Peter, T., Travers, R., & Saewyc, E. M. (2017). Enacted stigma, mental health, and protective factors among transgender youth in Canada. Transgender Health, 2(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0031

- White Hughto, J. M., Rose, A. J., Pachankis, J. E., & Reisner, S. L. (2017). Barriers to gender transition-related healthcare: Identifying underserved transgender adults in Massachusetts. Transgender Health, 2(1), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0014

- Willson, A. E., Shuey, K. M., & Elder, G. H.Jr, (2007). Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1886–1924. https://doi.org/10.1086/512712

- Wilson, E. C., Chen, Y. H., Arayasirikul, S., Raymond, H. F., & McFarland, W. (2016). The impact of discrimination on the mental health of trans* female youth and the protective effect of parental support. AIDS and Behavior, 20(10), 2203–2211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1409-7

- Wilson, E. C., Iverson, E., Garofalo, R., & Belzer, M. (2012). Parental support and condom among transgender female youth. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 23(4), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2011.09.001

- Yadegarfard, M., Meinhold-Bergmann, M. E., & Ho, R. (2014). Family rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behavior) among Thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11(4), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2014.910483