Abstract

This article explores the discourses parents adopt to support their transgender children in Aotearoa (New Zealand). Previous research with parents is limited by its focus on trauma rather than resistance and its lack of attention to intersectional experiences. To investigate how parents resist gender-based oppression, we use the method of reflective drawing, asking twenty parents of diverse social and cultural backgrounds to draw their experience of parenting a transgender child and discuss this in interview. We identified eight visual metaphors of storm clouds and rainbows, a maze, family portraits, blank space, standing side-by-side, hearts, arches, and question marks. These represent parent discourses of family resilience, personal transformation, shifting gender ideologies, depathologisation, child-led parenting, unconditional love, protection, and uncertainty about their child’s future. The parents’ discourses serve several interests: enabling them to focus on the hope of overcoming adversity, foreground the positive aspects of raising a transgender child, justify their gender-affirming approach, reframe their family gender ideologies, normalize their child’s experience, deflect stigma from their child and themselves, construct themselves as good parents, draw strength from solidarity, and express incertitude about what lies ahead. These provide parents with a means of enacting discursive resistance, with potential for driving broader social change.

Introduction

Tūngia te ururua kia tupu whakaritorito te tupu o te harakeke. Clear away the overgrowing bush so that the new flax shoots will spring up.

This whakataukī (proverb) in te reo Māori, the Indigenous language of Aotearoa (New Zealand), was shared with us by a Māori teacher advocating for LGBTQ + inclusion in primary schools. It references the harakeke (flax) plant, which in te ao Māori (the Māori worldview) is a metaphor of whānau (extended family). The harakeke symbolizes intergenerational whānau resilience, with the outer leaves (the older generations) represented as protectors of the inner leaves (the younger generations). The whakataukī refers to the horticultural practice of clearing away the weeds vying for space with new plants, which resonates with parents’ experiences raising transgenderFootnote1 children. Such parents are thrust into an unexpected situation and must manage their own turbulent reactions, in a hostile environment where they are forced to compete for space amidst negative social discourses stigmatizing them and their children. This places a burden on parents, who must beat back the overgrowing bushes of these discourses and supplant them with gender-affirming discourses, to prepare a space for their children to spring up in safety. When parents can nourish their children’s growth, they grow too.

This article explores the discourses that parents of transgender children in Aotearoa adopt to resist oppression and support their children to flourish. We begin by surveying previous research on the experiences of parents of transgender children, arguing for a need to focus on discursive resistance: how parents react to oppressive social discourses about transgender children by constructing affirming discourses in response. We then highlight relevant social and parental discourses described in previous research. Next, we describe our methodological approach, asking twenty parents of diverse social and cultural backgrounds to draw their experience of parenting a transgender child, to elicit the discourses they use to support their children. We present our discourse analysis via eight visual metaphors that appear in the parents’ drawings, considering the role these discourses play in the participants’ advancement of their children’s interests.

Research on parents of transgender children

Family support is protective for transgender young people, improving their wellbeing and increasing their resilience in facing challenges outside the home. Stigma, discrimination, and violence contribute to high levels of distress, but when a transgender young person feels supported by their family, their mental health can be equal to that of cisgender youth (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2020, p. 3). Accordingly, it has been claimed that ‘transgender children/youth demonstrate the best possibility for resilience and positive mental health when they are part of an affirming and supportive family and environment’ and that parents need support to support their children (Aramburu Alegria, Citation2018, pp. 132–133). This connection between family support and youth wellbeing forms the rationale for a substantial body of research on the experiences of parents of transgender children, as we discuss below.

Research on parents of transgender children has a long history, spanning health and the social sciences, and moving from a pathologising to an affirming approach (de Bres, Citation2022). The earlier pathologising approach is evident in the reporting of parent reactions of shock, guilt, shame, self-blame, regret, denial, and disbelief, researchers failing to conceive of reactions not involving negative emotions and trauma (Abreu et al., Citation2019; Field & Mattson, Citation2016; Gregor et al., Citation2015). One element of this pathologisation is a focus among researchers on the parental transition process (de Bres, Citation2022), an account of parents moving from shock to acceptance via phases akin to a grief process (Abreu et al., Citation2019; Emerson & Rosenfeld, Citation1996; Wahlig, Citation2015). This way of viewing parent experiences prioritizes negative parental reactions upon noticing a child’s gender non-conformity, such as policing their child’s behavior, before ‘eventually [realising] that acceptance [is their] only choice’ (Hill & Menvielle, Citation2009, p. 257). It fails to represent the diversity of parent experiences and reflects the long research history of problematizing transgender experiences (Hill & Menvielle, Citation2009).

Some recent research is affirming, relocating the problem from transgender children to society, and exploring a wider range of themes (de Bres, Citation2022). For example, Abreu et al. (Citation2022) explore parental figures’ reactions and coping strategies in relation to recent anti-transgender legislation in the USA, and Neary (Citation2021) and Manning (Citation2017) examine how middle-class mothers of transgender children mobilize their capital for broader social change. This more recent research allows for the possibility of children and their families driving social progress: ‘change, then, can fan out like shock waves: children change the parents, parents change the world’ (Galman, Citation2020, p. 15). When reporting negative parental reactions, researchers now often refer to a social context of stigma. For example, Schlehofer et al. (Citation2021, p. 2) attribute ‘obstructive parenting practices’ to ‘societal pressure, stigma, and judgment [that] can make it difficult for some parents to support their [transgender] child’. There is a need for further research to highlight resistance and resilience (Galman, Citation2020), exploring how parents support their children in the face of oppression, and recognizing that raising a transgender child can be a joyful experience.

Research to date in this area has two key limitations: the marked geographical bias toward North America and the lack of diversity in participants, who are overwhelmingly White middle-class mothers. This racial, class and gender profile reflects the population of people who access the gender clinics, queer organizations, and support groups from where participants are generally recruited. The relative absence of fathers is consistent with reports of lower engagement from fathers in supporting their child’s gender (Ryan, Citation2018; Ishii, Citation2018; Manning, Citation2017; Neary, Citation2021). Some research addresses issues relating to the middle-class bias of the parent movement in this area (Manning, Citation2017; Neary, Citation2021). The dominance of White participants means the experiences of minoritised ethnic groups are missing. A related important issue is that the researchers working with parents are often themselves members of majority cultural groups, which is likely to impact how they approach their research and analyze and report their results. The mix of researchers and participants described above results in an unrepresentative picture of parent experiences, which is particularly troubling given the realities of intersectional oppression (Manning, Citation2017) and variation in cultural norms regarding gender (Abreu et al., Citation2019).

There has been little research on parents of transgender children in Aotearoa. Māori academics have investigated whānau (extended family) support of takatāpui (Māori queer) youth, some of whom are transgender, using interviews with young people and their whānau (Kerekere, Citation2017; Laurence, Citation2020). They find that whānau support may be even more important for takatāpui youth, as whānau is a primary source of mana (dignity) in Māori communities. Research by and with Māori transgender people is essential in a context where Māori continue to experience the devastating effects of colonization. Prior to colonial contact, Māori were open to gender fluidity (Kerekere, Citation2017), but this was suppressed to assimilate them into Pākehā (New Zealand European) society. Western norms of heteronormativity and cisnormativity have suppressed Māori ways of being and doing, yet Māori communities continue to resist and reclaim them, including through the contemporary movement of rediscovering and celebrating takatāpui. Research on contemporary transgender experiences among Māori can aid this process and provide insights on more freeing concepts of gender (Kerekere, Citation2017).

In terms of the general Aotearoa population, the Counting Ourselves survey (Veale et al., Citation2019) was the first to ask transgender and non-binary people (aged 14 and older) about their experiences, one aim being to explore how support from family and whānau could protect transgender people against the impacts of stigma, discrimination, and violence. The results showed that if participants felt supported in their gender by over half their family and whānau, they were almost half as likely (9%) to have attempted suicide in the previous 12 months, compared to participants who said most of their family and whānau were unsupportive (17%). Counting Ourselves asked participants about ways family members could support them, including expressing support; using their preferred name; standing up for them; using their correct pronouns; doing research to support them; helping finance their transition; and assisting them with their name or gender change on IDs. The survey format of Counting Ourselves does not allow for exploring these factors in depth, and in order to understand what family support looks like in practice, qualitative research on parent experiences is needed.

Our research is one of the first to specifically explore the experiences of parents of transgender children in Aotearoa (see also Howe, Citation2022 on parent advocacy in schools). This study moves away from prior research that follows a homogenizing script of the parental transition process, using different methods to capture different stories, and accounting for a wider range of parents’ emotions. We prioritize parental resilience and resistance in facing oppression, basing our findings on interviews with participants of diverse social and cultural backgrounds, with a focus on discourse.

Discourses of parents of transgender children

As critical discourse analysts, our central concern is how discourse is used to reproduce or challenge social inequalities. We understand discourse as a point of view on the world expressed via language (and other semiotic resources, such as images). A key idea is that a point of view and the language to describe it cannot be separated: they are mutually constitutive—discourses are ways of talking about a phenomenon that come to be understood as the reality of that phenomenon (Cameron & Kulick, Citation2003, p. 16), or ‘practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak’ (Foucault, Citation1972, p. 49). Discourses gain momentum as they are spread from person to person, and those that rise to dominance exert immense power over how societies are organized. They often become so pervasive that they are taken to be ‘common sense’ and individuals may be unaware of the socially and historically situated processes underlying them. In this way, discourses ‘naturali[se] relations between language and social order’ (Philips, Citation1998, p. 217), ‘masking the social construction processes at work’ (Boudreau & Dubois, Citation2007, p. 104). Even dominant discourses are subject to contestation, with counter-discourses regularly arising to challenge them (Briggs, Citation1998). Being constructed in the interest of specific social groups, discourses can be used as strategic resources to pursue or exercise power (Woolard, Citation1998).

Parents of transgender children must construct their own discourses to counter the dominant discourses they face. A discourse analysis approach examines how parents advance this goal in interaction, investigating how they enact resistance in an oppressive discursive environment. Some previous studies have approached this topic from a discourse perspective to some degree. Meadow (Citation2018) examines how parents use discourses from medicine, psychiatry, and spirituality to explain their children’s gender; Sansfaçon et al. (Citation2015) focus on how parents use medical discourses to gain access to services while attempting to balance their pathologising effects, and Galman (Citation2018) explores parents’ use of historical discourses of pride, fear, and queer resistance to deal with an unsupportive environment. While the focus on discourse is implicit in these studies, the aim of our study was to specifically explore the range of discourses parents draw on to advance their children’s interests. We explore two main aspects: the social discourses about transgender children that parents encounter, and the discourses they adopt in response. Before presenting our results, we describe some relevant social and parent discourses in previous research.

Parents encounter dominant social discourses about transgender children in dealings with extended family, friends, schools, medical professionals, and their wider communities. These discourses frame transgender as pathology (e.g., via a diagnosis of gender dysphoria), reduce gender to biology, and binarise genders to include only female and male. They reflect a cisgenderist perspective that values cisgender experience over transgender experience (Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, Citation2018, p. 173). Within this perspective, parents are often blamed for their child’s gender diversity (Galman, Citation2020; Johnson & Benson, Citation2014; Manning, Citation2017). This is grounded in a traditional Western clinical approach that attributed a child’s transgender identity to parental flaws, such as an absent father or over-involved mother (Manning, Citation2017). These dominant discourses subject parents to secondary stigma (Johnson & Benson, Citation2014; Tsfati, Citation2021)—as Pyne (Citation2016, p. 24) puts it, ‘in supporting their children’s Otherness, some parents become Other themselves’. This stigma impacts parents’ social networks and their ability to access support (Abreu et al., Citation2019). Hidalgo and Chen (Citation2019) argue that, upon encountering sustained stigma, parents can experience gender minority stress paralleling that of their child, which has flow-on impacts for parents’ ability to support their children.

Parents sometimes reproduce the social discourses they encounter and sometimes resist them. Explicitly cisgenderist discourses among parents are rare in existing studies, likely due to parents being connected to support services and committed to affirming their children. But these discourses are present nevertheless in the omnipresent discourse of parental grief. Riggs and Bartholomaeus (Citation2018) claim that this discourse is socially supported within a context of cisgenderism, where parents are widely validated in experiencing their child’s transgender identity as a ‘loss’ and argue that ‘it is important not to accept the cisgenderist assertion that a transgender child is a loss, nor that any feelings of loss experienced by parents should be the responsibility of the child’ (p. 391). Parent discourses of grief are best understood in terms of a loss of gendered expectations of their child. As Wahlig (Citation2015) observes, ‘if sex and gender were understood to be variant and flexible, parents may not experience their child’s gender transition as a loss at all’ (p. 318). Indeed, some parents do not experience grief in discovering their child is transgender, perhaps because these parents are more open to counter-discourses that do not treat transgender in pathologising ways (Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, Citation2018).

Parents also draw on counter-discourses of gender affirmation. Pyne (Citation2016) describes how some parents shift pathology from their child to society: ‘Despite struggles, these families located the problem outside of their children. Summarizing his daughter’s difficulties, David said, ‘It’s everything around her that’s a problem, not her’’ (Pyne, Citation2016, p. 33). Some parents foreground benefits of affirming a transgender child, including improved relationships (Abreu et al., Citation2019), happier children (Pyne, Citation2016), expanded knowledge (Ryan, Citation2018), critical awareness (Abreu et al., Citation2019; Johnson & Benson, Citation2014), sense of purpose (Abreu et al., Citation2019; Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, Citation2018; Tsfati, Citation2021) and personal growth (Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, Citation2018; Johnson & Benson, Citation2014).

Method

As noted above, much research to date has prioritized the experiences of a restricted range of parents, mainly White middle-class mothers, often undertaken by researchers who are themselves members of socially privileged groups. In this context, it was very important for us to take an intersectional approach to our work that would incorporate the multilayered experiences of a wider range of parents. Intersectional approaches to research are critical in nature, seeking to explore how power is implicated in people’s life experiences at multiple levels and ‘how people are simultaneously positioned—and position themselves—in multiple categories, such as gender, class, and ethnicity’ (Christensen & Jensen, Citation2012, p. 110). All definitions of intersectionality involve recognizing that people’s experiences are structured by intersecting forms of oppression and privilege, which must be seen in connection rather than in isolation (Wyatt et al., Citation2022). While a relatively recent concept in Western social science research, the principles of intersectionality have long existed within Indigenous knowledge frameworks and research practices, including Kaupapa Māori approaches in Aotearoa, which have at their heart a holistic understanding of people as complex beings, intimately connected to each other and their environment (Clark, Citation2016; Olsen, Citation2018). Indeed, the idea of viewing a person through one facet of their identity is foreign to an Indigenous world view (Clark, Citation2016).

Although intersectionality is often applied to methodology, it is best conceptualized as a whole of project approach (Abrams et al., Citation2020). This includes undertaking research to advance social justice, formulating critical research questions, forming diverse teams, being reflexive about one’s own positionality as a researcher, engaging with relevant communities, recruiting diverse participants, using creative methods, and analyzing data from an intersectional perspective (Abrams et al., Citation2020). This article does not focus specifically on the intersectional aspects of our participants’ experiences (e.g., how the experiences of Māori parents differ from those of Pākehā parents), but our whole project was approached with an intersectional lens. We describe below the method we used for our research, including how we implemented an intersectional approach throughout.

Most research on parent experiences has used individual interviews (Aramburu Alegria, Citation2018; Emerson & Rosenfeld, Citation1996; Hill & Menvielle, Citation2009; Ishii, Citation2018). These have been in person, by phone, or via online chat and include semi-structured interviews, narrative interviews, and focus groups. Several studies use more expansive ethnographic approaches, where a single study might include interviews, journal writing, field notes, and observation. Some incorporate creative elements to enhance the interview experience and access different data. Gregor et al. (Citation2015) use photo elicitation, where parents are invited to share a favorite photograph, encouraging story-sharing with minimal guidance from the researcher. Galman (Citation2018, Citation2020) takes a more expansive arts-based approach, asking transgender children to compile ‘identity scrapbooks’ featuring self-portraits and autobiographical art, and visiting them in their homes to interview them about their creations. Feminist researchers support the use of creative and arts-based methods in intersectional research as a means of fostering methodological innovation (Mehrotra, Citation2022).

We employ reflective drawing (Castellotti & Moore, Citation2009), asking parents to draw their experience of parenting a transgender child and discuss this in an interview. Rose (Citation2016) provides a historical account of visual methodologies, observing that drawing has been a research method in the social sciences since the beginning of the twentieth century in psychology, sociology, anthropology and education. The first author has used it in previous research involving minoritised groups, due to its effectiveness in eliciting the personal, imaginative, subjective, and emotional aspects of participants’ experiences (de Bres & Lovrits, Citation2021; de Bres, Citation2017; Lovrits & de Bres, Citation2020). It is particularly valuable for this topic, as it allows participants to lead with their story, potentially bypassing the script of the parental transition process elicited in previous research.

We recruited twenty participants by posting an invitation to participate on the online support group New Zealand Parents and Guardians of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children (www.transgenderchildren.nz), of which the first author is a member. This group was selected as it is the only national group serving parents of transgender children in the country. The group had 752 members at the time of data collection. As in most previous research, the parents in this group are affirming parents, i.e., they have chosen to support their children in their self-determined gender. This represents a limitation in terms of the diversity of perspectives among the group but, although the group does not reflect the full range of parent experiences, group members hold various views and are at varying stages of accepting their child’s gender. The support group is mainly comprised of mothers, members being 85% female, 13% male, and 2% other gender at the time of data collection. While the group does not collect data on ethnicity, Pākehā (New Zealand Europeans) are numerically dominant. The group was started by Pākehā mothers and members often find the group via existing members. While the group attempts to be culturally inclusive, for example recruiting moderators to support Pacific and Māori parents, in practice it appears to primarily serve Pākehā parents. This reproduces a pattern observed throughout queer support organizations in Aotearoa, which are often viewed by queer people of color as primarily White spaces. It also echoes the dominance of White middle-class mothers in the parent advocacy movement in other Western countries (Manning, Citation2017; Neary, Citation2021). The group’s gender and ethnic profile was reflected in the participants who responded to the invitation to take part, all eighteen of whom were Pākehā mothers, apart from one Pākehā non-binary parent. We were not willing to proceed with only Pākehā participants and no fathers, so we randomly selected ten participants from our original respondents using an online random number generator. We then informed the others by email that we now had enough participants from their demographic category and could not include them. Next, we made a concerted effort to connect with participants of other cultural and gender backgrounds for the remaining ten participants. Our approach was to invite members who were active on the group (three Pākehā fathers, two Māori mothers and one Pacific mother), to ask members on the group if their partners might be interested in being interviewed (reaching two Māori mothers) and to make a post on the group specifically seeking Pacific and Asian parents (reaching one Asian mother, one Asian father, and one Pacific father). All the people we contacted enthusiastically agreed to participate. We included one further participant at this stage who was born in Europe (but who we have classified as Pākehā for the purpose of this project to preserve anonymity). The final participants comprised four Māori, two Pacific, one Māori/Pacific, two Asian, and eleven Pākehā parents. Fourteen were mothers, five fathers, and one a non-binary parent.Footnote2 The participants’ children comprised eight transgender girls, eight transgender boys, and three non-binary children. Seven of the children were Māori, two Pacific, one Māori/Pacific, one Asian, and seven Pākehā, aged from 6 to 18.Footnote3

The interviews took place at the participants’ preferred location, including their home, their workplace, a public space, the interviewer’s home, or on zoom. The interviewer asked them to ‘draw your experience of parenting a gender-diverseFootnote4 child’, which usually took about five minutes. They were then invited to talk about their picture and were asked follow-up questions to build on their description and explore visual features of interest, e.g., ‘I see you’ve drawn a rainbow here, can you tell me what that means in your drawing?’, or ‘do the colors you chose to use have any significance to you?’. When discussion of the drawing was exhausted, further topics were introduced, relating to the participant’s experiences in family, educational and medical contexts. Reference to the drawings recurred throughout. Explicit references might include a participant saying ‘it was like that’, pointing at their drawing as they told a story, or the interviewer making a link between what a participant was saying and a scenario they had pictured in their drawing, e.g., ‘she looks quite happy here’. Implicit references involved participants returning to a salient theme they had drawn, e.g., anxiety about how others might treat their child, even if not mentioning the drawing explicitly. Two participants structured their whole interview by progressing through the various elements of their drawing, their drawing thereby central to the construction of their narrative. This interconnection between the visual elements of the drawings and verbal representations of participants enabled shared interpretations of the drawings during the interviews and provided well-grounded analytical connections between visual and verbal discourses. When the interview ended, participants were shown other parents’ pictures (with prior permission), and many pointed out connections they could see between their own drawings and others’, which assisted our analysis. The interviews averaged 73 min (ranging from 56 to 102). All participants received a voucher as acknowledgment of their participation.

Despite traditional claims to objectivity within the social sciences, the subjectivity of researchers is increasingly recognized. This is particularly evident with interactive methods such as interviews, where the identities of interviewer and interviewee are negotiated across the interview. When the topic of the research is parents of transgender children, the gender of both interviewer and interviewee will pervade the interview. For example, when a female interviewer is talking to a male interviewee about how his experience of having a transgender child has influenced his own relationship to masculinity, both participants are likely to be aware of their own and the other’s gender at this point of the discussion. Other aspects of identity will also become salient at different points, such as age, parent status, ethnicity, professional role, and so on (Lønsmann, Citation2016). The first author and interviewer is a Pākehā cisgender parent of a transgender child, so her in-group identity as a fellow parent influenced the interviews in multifarious ways. One positive effect was the rapport of shared lived experience and interactions through the group. The second author and research assistant is a takatāpui transgender person and, while they did not conduct interviews, their perspectives were essential in interpreting the data. This interaction between parent/child, Pākehā/Māori, and cisgender/transgender researchers was central to the data analysis, comprising discussion, separate interview notes, and drawing pictures of our own experiences. Recent work in this area sometimes refers to methods researchers use to manage their emotional reactions, e.g., by ‘[keeping] coding journals to document their reactions, feelings, and thoughts through the coding process’ (Abreu et al., Citation2022, p. 5) and dedicating ample time and discussion ‘to process the impact of listening to participants’ stories’ (Schlehofer et al., Citation2021, p. 6). The first author had intense reactions of anger, fear, horror and disgust as the participants described what their children had experienced, sometimes feeling physically sick in interviews. Participants often expressed strong emotions, sometimes crying as they talked about their children’s discrimination experiences, self-harm, depression, and suicide attempts. The second author felt overwhelmed while transcribing and analyzing the interviews, recalling past experiences regarding their gender fluidity. Rather than exhibiting a failure of objectivity, we feel that such emotional and personal engagement by researchers and participants enhanced the analytical process and led to more meaningful results.

Analytical approach

Our analysis focuses on both the visual discourses in the drawings and the verbal discourses in the interviews, especially where they overlap. Discourse analysis is often associated with verbal data, but the same approach can be applied to visual images. We followed the steps in the interpretive process proposed by Rose (Citation2016) for Foucauldian visual discourse analysis, identifying the strategies used to ‘visually and verbally assert the truth of a particular discursive claim’ (p. 214). These steps comprise: paying detailed attention to the images (e.g., composition, color, size); identifying themes in the form of recurring visual features; noting techniques of persuasion; attending to complexity and contradictions that orient to multiple discourses; and recognizing what is and is not included. We also drew on the toolkit provided by critical multimodal analysis to help us identify visual meanings (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020). Multimodal analysis, in the tradition of social semiotics, focuses on choices by the creator of a visual image between design elements such as composition, perspective, color, materiality, typography, diagrams, etc. When used to explore underlying power relationships, it is termed critical multimodality (Machin et al., Citation2016). We view Foucauldian and critical multimodal approaches to analyzing visual discourse as complementary. The former provides an overarching critical orientation, being embedded in Foucauldian approaches to discourse that investigate how members of social groups use discourse to acquire or maintain power. The latter lends precision in analyzing the images, given its detailed attention to the micro-level of visual features and their potential meanings in different social contexts.

Our analytical focus is the visual metaphors that parents use to construct their experience. In verbal form, a metaphor is a figure of speech in which a word or phrase literally denoting an object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness between them. Visual metaphors perform a similar function: they involve an image that the viewer is meant to understand as a symbol for something else. When considering a visual metaphor, the first step is to consider what two concepts are being linked—the literal and the figurative. In the case of a visual metaphor of a rainbow, for instance, the two concepts could be the rainbow (literal meaning) and the queer community (figurative meaning). The next step is to identify the point of the analogy. Here, the metaphor transfers the rainbow’s associations of brightness and multiplicity onto the queer community, suggesting the queer community is bright and diverse too. Importantly, the figurative meaning of a metaphor is context-dependent—for instance, this rainbow could mean something else entirely in a meteorological discussion group. Part of the power of visual metaphors is that they mean different things to different people. To determine which meanings were at play in this data, we triangulated our own analyses with the verbal descriptions of our participants and the drawings of other participants, to arrive at a joint negotiation of meaning. To count as a salient visual metaphor, we decided it should occur in more than one drawing; as discourses are shared between people, this recurrence suggests the presence of a visual discourse. Further interviews might have led to the identification of further discourses, but we focus on those that were demonstrably shared among these participants, based on the recurrent visual metaphors identified.

As discourse analysts, we seek to identify how people construct their experience via language (and in this case visuals) to achieve certain social goals. In the present study, we wanted to identify how parents use discourse to support their transgender children. To do so, we approached what the participants drew and said in terms of what they were doing with discourse, rather than approaching such discourse as a direct reflection of their inner thoughts. This is a key difference between discourse analysis and thematic analysis (Talja, Citation1999; Wetherell & Potter, Citation1988). We think of discourses as strategies that people draw on to advance their interests in a given context. If a person makes a claim that ‘there are only two genders’, they are drawing on a dominant cisnormative discourse that may reflect their interests in maintaining the gendered status quo. If a person makes the competing claim that ‘transgender people have existed since the dawn of time’, they are drawing on a discourse that challenges such cisnormative ideologies of gender, thereby opening spaces of inclusion of people with minority gender identities (such as their children). People construct personal discourses by creatively selecting from social discourses they have been exposed to, in whatever combinations they perceive to serve their interests (de Bres, Citation2014; Woolard, Citation1998). We are interested in how participants frame their experience, and what discursive resources they draw on to do so. Parents will use the discourses they share in interview elsewhere too and, as these discourses spread through their networks, they have persuasive potential for promoting social change.

Results

We present eight visual metaphors participants used to construct their experience of parenting a transgender child. In discussing these metaphors as a form of visual discourse, we draw on both the visual elements of the drawings and the verbal elements of the participants’ descriptions, alongside the verbal discourses they expressed elsewhere in interview. Our primary goal is to examine how parents use these discourses to further their interests and those of their children.

Storm clouds and rainbows

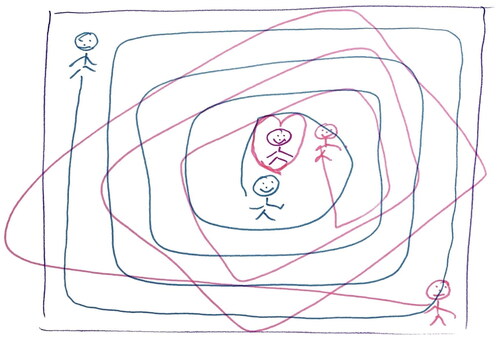

Several participants drew storm clouds and rainbows, as the first author did in her own drawing (), undertaken prior to the interviews.Footnote5 This twin metaphor depicts family resilience amidst societal oppression, alongside parents’ anxieties and hopes for social change.

Transphobic discourses

The storm clouds represent fear or uncertainty about transphobic discourses in politics, media, and society. Parents drew these clouds in the environment surrounding their child ( and ), representing an impending threat to their wellbeing. For some participants, these discourses were at some distance from the family, involving removal of laws protecting transgender people from discrimination internationally, misinformation about transgender people on social media, and attempts to reduce access to gender-affirming care. Others encountered them closer to home. Some had experienced rejection from friends or family, one commenting that her partner had ‘lost his entire family’ over supporting his transgender child. Some had encountered trauma dealing with schools, with their children experiencing bullying, a lack of appropriate reaction from the schools, and unsupportive fellow parents. Many had struggled in medical contexts—one parent described navigating the health system as ‘virtually impossible’, with unclear and slow pathways leading to feelings of stress and disempowerment, which another parent expressed as being like ‘a punch in the guts over and over again’. Others referred to medical experiences of ‘unsaid resistance’, ‘gaslighting’, and ‘gatekeeping’ in the process of accessing puberty blockers and/or hormones, amounting to emotional, mental, and physical abuse for one participant. One was investigated by child social services, who arrived unannounced at her home and misgendered her child, using his former name and pronouns, after which the child ‘went back to pretending to be a girl for two weeks’. Another was contacted by a stranger online, framing her as a child abuser. One described feeling the transphobia directed at his child viscerally—’you feel like it’s directed at you’. Even for those operating within a supportive immediate environment, these social discourses remained a foreboding presence, two parents saying they were always waiting for the ‘ball’ or ‘brick’ to drop.

Affirming discourses

The rainbows represent discourses of gender affirmation. Sometimes these rainbows were drawn external to the child, in the broader environment, as in . Parents described them in terms of the support they received from family members (e.g., giving gender-affirming gifts to their children), from the rainbow community, or from wider society (e.g., in public discussions supporting banning conversion practices at the time of the interviews). Sometimes the rainbows were pictured as inherent to the child, as in . In this case the rainbows represent the beauty and resilience of the child within an oppressive society. One participant framed her child’s resilience as responsive to oppressive social discourses, commenting ‘you can’t have a rainbow without storms’. One described her child as ‘a beacon of light drawing people toward him’, another as a charismatic ‘force of nature’ who ‘takes people with her’.

In focusing on the beauty of their child, parents constructed a counter-discourse to the discourse of grief, in which the process of affirming their child’s gender was something to celebrate. One parent said, ‘all you’re told about it is the negative’, contrasting this with her experience of her son transforming ‘into a totally different child’—much happier and more extroverted—when his parents affirmed his gender. Parents recounted joy watching their child become their ‘best self’, valuing the process of exploration, authenticity and creativity. Several described their children as brave, empathetic and good, one claiming her child’s desire to make the world better came in part from her minority experience. Another commented that her child’s gender was a lovely quality that ‘makes life so much more special, because they’re slightly different’. This discourse of transgender joy allows parents to reframe their child’s gender in a positive light and to focus on the hope of overcoming adversity, which Tsfati (Citation2021) sees as key to parental resilience. One participant made an explicit connection between hope and the rainbow metaphor, observing that rainbows are hopeful and uplifting—’to have that spectrum around me is beautiful’.

Mazes

Two participants drew a maze, representing the complexity of their experience and the associated opportunities for personal growth.

Journeys

Participant 2 described his drawing () as being about the different paths he and his wife took toward accepting their child’s gender. He initially found it easier than her, so they couldn’t travel together, which presented a major challenge to their relationship. The journey starts with the parents at opposite sides of the page, their faces frowning. Their paths criss-cross at different points as they make their way toward their son in the middle. The participant said he had always described the experience as like being at different places on a piece of paper and, as they risked falling off the edges of it, he had to ‘expand the piece of paper’ to make sure they remained ‘on the same page’. At the center of the drawing, the parents are depicted as having reached their destination with everyone smiling. He described the journey as the most ‘transformative’ experience of his life. He spoke of this process as intense, profound, and an awakening, saying ‘I was as enriched as I was challenged’.

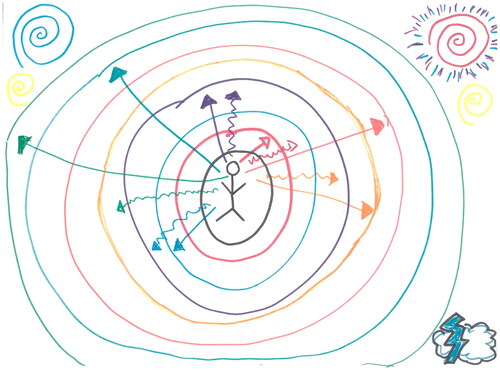

The drawing in also represents personal growth, in this case in knowledge. Participant 3 drew herself in the middle of rainbow-colored concentric circles, with arrows proceeding outward as she found her way toward understanding her child’s experience. The circles are surrounded by external forces that are positive and negative (fireworks, storm clouds and lightning). She explained that she had drawn these elements at a distance from her to reflect that they were not central to her experience but that they impacted it. She explained that the arrows of different lengths and shapes indicated that she advanced faster in some areas than others. She noted that her drawing had ‘a lot going on’, with ‘lots of different levels of information’, ‘things [going] up and down’ and ‘backwards and forwards’, the conditions always changing and her adapting to them. But ‘it is a big rainbow’ because her daughter has taught her that ‘there are a lot of rainbows in life and at times rainbows can be unpredictable and fleeting but then also very vibrant’.

Intellectualization

The participants who drew mazes utilized a discourse of intellectualization, referring to their use of reasoning to cope with stress (Cariola, Citation2020). When Participant 3’s partner told her he thought their child might be transgender, she said ‘I need to research this’. She extensively researched transgender issues as part of her university study and used her findings to talk to her wider family, saying ‘this is the research we’ve read, these are the doctors we’ve seen, this is how we’re going to parent our child, and you might want to watch this documentary’. Participant 2 treated his child coming out as ‘an intellectual problem to solve’. He decided he needed ‘intellectual horsepower’ to resolve it. He said it was an ‘issue space’ that he and his partner had to ‘come to terms with’ and he ‘was not going to accept failure to deal with this’ so just ‘went in’ to ‘solve it’. Both described their search for knowledge as empowering and acquiring it reassured them in their approach to affirm their children. Drawing on this discourse of intellectualization furthers their interests by lending them authority and emboldening them in their parenting choices.

Transformation

Like mazes, other drawings oriented to an overarching metaphor of journey, using arrows and a compass to allude to the navigation and change involved in parenting a transgender child. The discourse of parental transformation in these drawings recurs in previous research, a literature review noting that ‘findings from 29 studies suggested that parents underwent a transformation process of their own upon learning they had a [transgender] child’ (Abreu et al., Citation2019). One study observes that ‘oftentimes parents believe that their gender-nonconforming children make them better people through living the experience of being “different” (Johnson & Benson, Citation2014). This was echoed by one of our participants, who said, ‘it’s made me a better person—I definitely feel like I’m so lucky to have a trans child’. Our participants attached a variety of personal benefits to their experience, including learning about gender and sexuality, examining their assumptions, becoming aware of the LGBTQ + community, learning how to support and include transgender people, meeting ‘some very vibrant alive people’, improving their relationships, and their children giving them ‘a deeper appreciation of humanity’. An interest served by this discourse is to counter the prevailing negativity around parenting a transgender child. In foregrounding the positive aspects of their experience, parents can reframe this experience as a force for good not only in their child’s life (as in the case of the rainbows in the previous section) but also their own.

Family portraits

Several participants drew family portraits in the form of stick figures, to show how gender ideologies within their family had evolved via parenting a transgender child.

Shifting family configurations

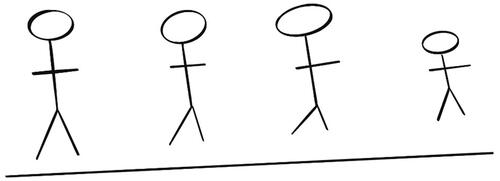

Participant 1’s drawing in is a before-and-after picture depicting a shift from a traditionally gendered family to a gender-expansive family. In the ‘before’ scenario, the participant noted that he drew a mum, dad and two kids, even though he had four, indicating this was symbolic of the normative family unit—’what I’d class as a standard family’ in a ‘little square boxed house’. The ‘after’ scenario represents a jumble of storm clouds and rainbows, alongside question marks reflecting uncertainty about what lies ahead as the family structure changes—the ‘unknown’. Participant 2’s drawing in also shows two normatively gendered parents—one pink and one blue, with their transgender child pictured in purple. Participant 2 described himself as coming from a ‘traditional’ ‘conventional’ family in terms of gender norms and having a ‘straightforward’ view of gender. He referred to a ‘seismic shift’ having occurred within the family during the process of his child’s transition, commenting that parents who had more expansive gender norms to start with might feel less of a shock. Indeed, the drawing in , made by Participant 4, who is a non-binary parent, represents a gender-neutral family they strived to create, where none are visibly gendered, and all are roughly the same height. This drawing reflects a refusal to impose gender norms on their children and a desire to create a family dynamic of ‘equal autonomy’ where the children are viewed as ‘individual human beings’ and the parents do not impinge on their subjectivity. Here no shift in family gender norms is required, the participant remarking that their drawing might appear ‘soulless’, yet ‘there is so much possibility’.

Family gender transitions

We identify a complex intertwining of gender and parenting discourses in these and other drawings, highlighting the nature of parenting as a gendered project (Field & Mattson, Citation2016). But we can see that transgender children challenge these norms, and thereby trigger different kinds of parenting. Research shows that parenting a transgender child leads parents to question long held beliefs about gender (Ryan, Citation2018). This can also lead to shifts in gendered identity as a parent, as parents seek to adjust their self-conception as, for example, a mother of a boy or a father of a girl (Field & Mattson, Citation2016). In some cases, parents reconsider their own gender identity (Ishii, Citation2018). In such ways, parenting a transgender child can be a transformative experience for the whole family. The term family transition is sometimes used to express this point: ‘In families with transgender youth, the process of youth forming a transgender identity and transitioning to their affirmed gender affects all family members. In a sense, families with transgender youth are all transitioning’ (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2017).

In presenting portraits representing family transition, the participants reframe their preexisting gender ideologies to incorporate the non-normative gender of their child. In , Participant 4 portrays their vision of the ideal family unburdened by dominant gender norms.

Blank space

The relative starkness of the drawing in is echoed in the drawings of two further participants, which we see as invoking a visual metaphor of blank space.

Parenting is parenting

Participant 5 drew a single word—’parenting’—in bright pink, the closest pen she could find, which she said was like parenting in general, using whatever resources one has at hand (). Participant 6 declined the invitation to draw. She had been given the drawing instruction in advance of the zoom interview and said she could not think of one image that would capture the experience, asking: ‘is there a difference between a transgender child and a child?’. Both these participants asserted there was nothing distinctive about parenting a transgender child as opposed to any other child. Participant 5 said ‘95% of parenting a trans kid is the same as parenting a cis[gender] kid’, referring to the everyday tasks of getting kids ready for school and into bed on time. Participant 6 said ‘they enrich your life so much, and you learn so much from them’, referring here to all her children. They each resisted the discourse that having a transgender child is hard, being averse to positioning their children as a problem. Participant 6 said it was easy for her to accept her child’s gender: ‘It was no big thing, it was just ‘oh we’ve misgendered you. I’m sorry, my bad.’ It wasn’t really an issue.’ Some parents echoed these points in interview, one commenting that being transgender ‘is just a point of difference—because it’s not the norm—statistically it is a difference’. Another observed: ‘It’s just another normal thing. It’s not some big scary thing […] your child is still your child in whatever form they present.’ One suggested that parents should treat their child ‘just as a normal kid and [not] make a big foofoo about it all the time’. Several indicated that other features of their child’s experience (e.g., disability, chronic illness or neurodivergence) presented equal or greater challenges or that parenting their cisgender child could be just as challenging.

Normalization and depathologisation

In underlining the normality of their experience, participants resisted pathologising discourses that present transgender children as abnormal, and constructed counter-discourses of depathologisation, whereby being transgender is a form of gender rather than a failure of gender (Meadow, Citation2018). By discursively shifting the problem from the child to society, the parents attempt to normalize their child’s experience and deflect stigma from their child. As one parent described: ‘It makes people more accepting when you let them know and […] they see how unaffected you are by the situation, then they’re like it’s just a normal thing.’ We noted that a discourse of normalization was especially present among parents with minority identities (transgender, queer and ethnic minority parents). These parents have experiences of being othered, which may lead them to empathize with their child’s experience differently than parents from majority groups. They may use this discourse of normalization to serve further interests, including deflecting stigma from themselves.

Standing side-by-side

Another visual metaphor was a parent standing side-by-side with their child, representing accompanying a child through life rather than leading the way.

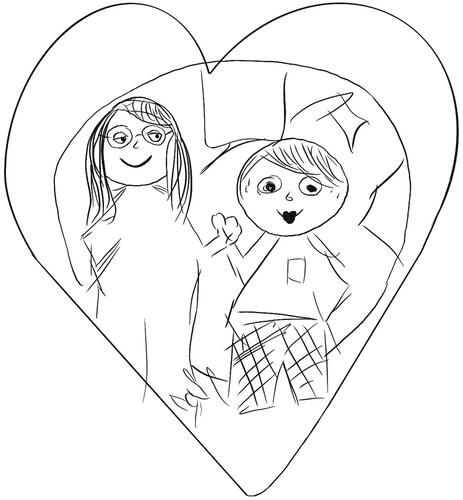

Children leading parents

The drawing in by Participant 7 shows the participant standing next to her child, holding their hand as she gazes proudly upon them, both encircled in a heart, with the world behind them. She described her drawing as showing ‘we are surrounded by love through this journey. We’re taking on the world and holding hands because we’re going through the journey together’. She emphasized that the journey is her child’s, who is taking her along for the ride. Her advice to other parents was to ‘trust your child, let them lead you’. Several parents reiterated the journey was about the child, not them: ‘It’s not me going through that journey, it’s them. So, though I can have empathy, it’s not me’. One said that he would advise other parents to ‘not try to control it because if that’s the way they express themselves and they’re happy, why would you try to control it or try to change it?’ Another noted that ‘it’s quite similar to parenting a cisgender child—you’re still there to support and guide your child, the only difference is that you might not know the way’. One participant drew guidance from the Māori concept ako which conveys the idea that the parent-child relationship is one of reciprocity, where the child has as much to teach as to learn. Others described how parenting a transgender child had led them to change to a less directive parenting style, one commenting that this had ‘completely changed the way I parent’, now involving more consultation with her child, recognizing his autonomy, and respecting his opinions, a change she celebrates. Another stated ‘you become the parents you need to be for each child’.

Child-centered parenting

These participants’ descriptions reflect a discourse of child-centered parenting, in which parents are led by their child’s needs and seek to foster their unique individuality (Neary, Citation2021; Pyne, Citation2016). Some countered potential resistance to this discourse by orienting to competing discourses of parental authority. One argued that parents have no right to prescribe the existence they want for their child: ‘When parents say ‘what about my rights as a parent?’, no one has taken away your rights as a parent. It’s just they’re not what you thought they were.’ Another clarified that, while her ‘parenting philosophy is listen to your kids’, her parenting style is a ‘benevolent dictatorship’. She explained that she imposes many rules but allows freedom of choice within them, and that her children have complete autonomy over their gender identity. Employing such discourses allows parents to justify their affirmation of their children in the face of opposition to their parenting style, thereby mobilizing parenting discourses to reach the “hearts and minds of parents who might not otherwise support” their trans children (Manning, Citation2017; see also Galman, Citation2020).

Hearts

Hearts appeared in several drawings, representing discourses of unconditional love and support.

Unconditional love

The drawing by Participant 8 in shows a collection of overlapping rainbow-colored hearts. Together these colors make a rainbow, but the participant indicated that the color of each heart also had meaning, for instance brown representing hard times and blue representing her parenting values. She explained that the hearts were dynamic and scattered, representing change, but also the constancy of unconditional love for her child: ‘the love doesn’t change, the love is constant, but the parenting and the child change all the time—the parenting responds to the changes’. She oriented to the intensity of her love for her child by saying ‘as soon as you have a child, your heart becomes something outside your body’, adding ‘our watchword is support—whatever happens, he’s loved and supported’. Another drew her chest with her child inside her heart, saying ‘he’s just my heart’ and that she sees her role as a mother to protect him, while also giving him space to grow.

Strength in support

In underlining this loving emotional connection, the parents drew strength from solidarity with their children. This is apparent in Participant 7’s drawing in , where the participant and her child are pictured inside a heart, the two of them ‘taking on the world’. Another commented ‘the world is really tough on our kids at the moment, the last thing they need to have is us being tough on them’. One said life is easier for trans kids if ‘they get support from one person at least who sticks up for them.’ Some oriented to the powerful effects of parental love, one referring to research indicating ‘the single biggest protective factor for gender diverse kids [is] feeling that unconditional love and acceptance of their family’. This seems to signal awareness among some participants that parental support is key to child wellbeing, and to that of transgender children in particular (Pullen Sansfaçon et al., Citation2020). All seemed conscious that their support of their children was likely to ease their passage through the world and help them develop a positive sense of self. One commented that he didn’t need to fully understand his child’s gender to support him, and another observed that it was ‘OK if people take a while to get where they need to be, as long as love for the child is assured throughout’.

Arches

As we proceeded with the interviews, a more subtle overarching discourse appeared—a discourse of protection.

One visual metaphor for this was an arch, shown in Participant 9’s drawing in as a heart-shaped koru (fern frond) covering the children of the whānau (family) and a rainbow covering the whole whānau. This metaphor symbolized protection of the children by the parents, as well as protection of the whānau by their iwi (tribe), hapū (subtribe) and the rainbow community around them. In two instances, the arch of an umbrella represented the parent’s attempts to shield the child from nefarious discourses and/or the child’s own worry and anxiety, as in Participant 10’s drawing in . In another parent’s drawing, the arch of a parent’s ribs was pictured to symbolize protection of her child from ‘the outside’. Elsewhere, protection surfaced visually as a mother’s hands reaching toward her child, a father standing on a hill watching as his daughter interacted with her peers in the valley below, and a fence built by a mother to ‘protect [her children], to like shoot people over the top of [it]’. The parents’ desire to protect their child was thus instantiated in various visual metaphors—and this was perhaps the most pervasive visual discourse of all. One said she had spent her child’s whole life trying to ‘protect her from bullshit’. Others talked of trying to create a protective ‘bubble’ or ‘force field’ in which their child could be themselves for as long as they could. Another suggested a parent’s job was to ‘keep kids safe and give them a soft place to fall’. This discourse was nuanced by parents of older children, two of whom drew enclosed spaces with an opening (e.g., a gate in a fence) to reflect the need to relax their protectiveness to give their children space to grow into adulthood. One commented: ‘[Early in age] you’re doing a lot of the parenting and protectiveness, especially as he is trying to find his way, where he fits. Now as he is quite comfortable in his expression, knows who he is, he’s thriving, it’s like I can pull back and so my parenting kind of lessens so he’s free to go out in the world and be himself.’

Parents as protectors

One interest served by this discourse is to allow participants to focus on their efficacy as parents in a challenging environment. One spoke of having read the negative statistics about transgender young people in terms of psychological distress, but said that he had also read about the things he could do to improve these statistics for his own child and said he was ‘doing all those right’. Focusing on their protective powers may help parents feel less helpless when faced with the oppression of their children. Another interest is to construct themselves as good parents and avert blame. Stigma and blame enshroud parents of transgender children, who are accused of, at best, irresponsible parenting and, at worst, child abuse (Barron & Capous-Desyllas, Citation2017; Manning, Citation2017). Riggs and Bartholomaeus (Citation2018) describe how parents are often initially torn between the competing imperatives of safety and affirmation in responding to their transgender child, believing that if they allow their child to express their gender, they will not be able to keep them safe in a harsh world. Portraying themselves as staunch protectors of their children enables parents to highlight a different kind of parental virtue, evoking acceptance as protection.

Question marks

Question marks appeared in two drawings, representing uncertainty about what lay ahead.

The drawing by Participant 10 in is striking in that it includes almost every visual metaphor we found, by a participant who, like the others, had seen none of the other drawings at the time of drawing.

The participant drew hearts representing unconditional love and support, an umbrella representing protection, a compass representing navigating the journey (similar to the metaphor of a maze), rain representing worry and anxiety and sunshine representing excitement and happiness (similar to the metaphor of storm clouds and rainbows), with the drawing as a whole making up the colors of a rainbow. In addition to these visual metaphors, the participant drew question marks representing uncertainty and exclamation marks representing surprise. Question marks also appeared in the drawing of Participant 1 (), where they represented him looking into the future and being unsure as to how his family might change as a result of his child’s transition. Participant 10 described uncertainty as the ‘biggest thing’ in terms of challenges, asking herself constantly ‘am I doing the right thing?’ and not knowing what else she could or should do. She expressed a past wish to look into the future or go in a time machine to see the long-term outcome of her gender-affirming parenting choices. Reflecting in interview, she described feeling vindicated after thirteen years of parenting this way, believing she had made the right decisions as her child was feeling OK for the first time. Nevertheless, she commented that ‘there was so much doubt placed on us’. Such doubts can be attributed to the ongoing influence of dominant discourses, even among gender-affirming parents of transgender children. This visual metaphor allows the participants to express their feelings of incertitude and fear for the future, even as they advocate discursively for their child.

Conclusion

This article has explored how parents of transgender children in Aotearoa discursively construct their experience of parenting a transgender child, in the context of oppressive social discourses about transgender children. The research resulted in rich visual and verbal depictions of gender-affirming parenting, which reveal a range of discourses used by parents to support their children. These are distilled in the eight visual metaphors that recur in the drawings, of storm clouds and rainbows, a maze, family portraits, blank space, standing side-by-side, hearts, arches, and question marks. They represent parent discourses of family resilience, personal transformation, shifting gender ideologies, depathologisation, child-led parenting, unconditional love and support, protection, and uncertainty about what the future holds for their children.

The visual metaphors recurred across the drawings, most combining several visual metaphors. Sometimes one metaphor could signify multiple discourses (e.g., the rainbows signifying gender-affirming discourses in broader society, the beauty of a transgender child, or a parent’s transformation over time) and sometimes several metaphors were used to convey the same discourse (e.g., an umbrella, a parent gazing upon their child, or parental hands signifying protection). This recurrence strongly indicates shared discourses circulating among the gender-affirming parents who made up our sample.

These discourses enable parents to advance several interests: to focus on the hope of overcoming adversity, foreground the positive aspects of their experience, claim authority for their gender-affirming approach, reframe their family gender ideologies, normalize their child’s experience, deflect stigma from their child and themselves, construct themselves as good parents, draw strength from solidarity, and express their incertitude about what lies ahead. Combined, they provide parents of transgender children with a means to ‘exercise their agency’ (Tsfati, Citation2021) and resist oppression.

We conclude that a central way these parents support their children is via discourse itself: organizing their thoughts and experiences into schemas of understanding that allow them to enact discursive resistance in dealing with a hostile world. Aside from improving parents’ resilience as individuals, this use of discourse has the potential for enormous wider impact, as parents spread these discourses among each other and their networks. This discursive resistance at the individual level thus has broader political implications in promoting social change. As Galman (Citation2020) describes in her study of parents of transgender children: ‘the mothers were changed by their daughters and the communities changed by the mothers as they moved from acceptance to fiery advocacy, like so many outwardly-falling dominoes of transformation.’ (p. 9).

Identifying these discourses is beneficial for both research on parental support of transgender children and for parents of transgender children themselves. In terms of research, our results contribute to a rising tide of strengths-based research that focuses on how parents and children resist oppression, overcome adversity and live positive lives, rather than presenting them and their children as helpless victims of trauma (Galman, Citation2018; Manning, Citation2017; Meadow, Citation2018; Neary, Citation2021; Tsfati, Citation2021). This affirming approach is essential in a research area that has a long history of pathologising transgender children and their parents (de Bres, Citation2022). Inviting parents to draw their experience is an especially useful method for encouraging them to tell their own story as they see it. The results are also of potential benefit to parents. Learning about the discourses circulating among gender-affirming parents, parents might repurpose some of these discursive strategies to promote their children’s interests. For instance, when faced with a pathologising discourse during an encounter with an acquaintance, they might draw on a discourse of depathologisation.

Even when parents adopt such gender-affirming discourses, however, they often experience lingering doubts in response to criticism from others (Johnson & Benson, Citation2014; Sansfaçon et al., Citation2015) and feel uncertainty about what lies ahead for their children (Galman, Citation2018). Such discursive dynamics place affirming parents in a precarious position, as they continue to respond to dominant discourses about childhood gender diversity. This struggle will become easier for parents as counter-discourses become more prevalent in society. Meanwhile, the discursive environment remains dangerous and harmful to transgender children and their families. To return to the whakataukī at the outset of this article, much work remains to be done to clear away the obstacles to ensure transgender children have an environment that allows them to thrive.

Notes

1 We use ‘transgender’ as an umbrella term to refer to anyone whose gender does not conform to dominant social expectations associated with their gender assigned at birth, including non-binary people.

2 Participants were not asked about their sexual orientation, but it became clear during the interviews that members of sexual minority groups were over-represented in the participants, with seven of the twenty not identifying as heterosexual.

3 In two cases, we interviewed both of a child’s parents. For one couple, this was in the form of two separate interviews. For the other, the couple was interviewed together, as was their preference. All other interviews in the data set were individual interviews.

4 We used the term ‘gender-diverse’ at the time of the interviews, but have since adopted the term ‘transgender’, following the advice of Gender Minorities Aotearoa, who noted that ‘gender-diverse’ is often used by parents as a euphemism for transgender. To us, both terms have the same meaning when used as umbrella terms, so we adopted the practice of the main community organisation for transgender people in Aotearoa.

5 Some drawings have been traced on a digital drawing programme to enhance their visibility.

References

- Abrams, J. A., Tabaac, A., Jung, S., & Else-Quest, N. M. (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113138

- Abreu, R. L., Rosenkrantz, D. E., Ryser-Oatman, J. T., Rostosky, S. S., & Riggle, E. D. B. (2019). Parental reactions to transgender and gender diverse children: A literature review. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 15(5), 461–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1656132

- Abreu, R. L., Sostre, J. P., Gonzalez, K. A., Lockett, G. M., & Matsuno, E. (2022). “I am afraid for those kids who might find death preferable”: Parental figures’ reactions and coping strategies to bans on gender affirming care for transgender and gender diverse youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(4), 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000495

- Aramburu Alegria, C. (2018). Supporting families of transgender children/youth: Parents speak on their experiences, identity and views. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1450798

- Barron, C., & Capous-Desyllas, M. (2017). Transgressing the gendered norms in childhood: Understanding transgender children and their families. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(5), 407–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2016.1273155

- Boudreau, A., & Dubois, L. (2007). Français, acadien, acadjonne: Competing discourses on language preservation along the shores of the Baie Sainte-Marie. In M. Heller & A. Duchêne (Eds.) Discourses of endangerment: Ideology and interest in the defense of languages (pp. 99–120). Continuum.

- Briggs, C. L. (1998). ‘You’re a liar – you’re just like a woman!’: Constructing dominant ideologies of language in Warao men’s gossip. In B. Schieffelin, K. Woolard, & P. Kroskrity (Eds.) Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory (pp. 229–255). Oxford University Press.

- Bull, B., & D’Arrigo-Patrick, J. (2018). Parent experiences of a child’s social transition: Moving beyond the loss narrative. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 30(3), 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2018.1448965

- Cameron, D., & Kulick, D. (2003). Language and sexuality. Cambridge University Press.

- Cariola, L. (2020). Intellectualization (defense mechanism). In Zeigler-Hill, V. & Shackelford, T. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1389-2

- Castellotti, V., & Moore, D. (2009). Dessins d’enfants et constructions plurilingues. Territoires imagés et parcours imaginés. In Muriel Moliné (Ed.), Le dessin réflexif: Element pour une herméneutique du sujet plurilingue (pp. 45–85). Université de Cergy-Pontoise.

- Christensen, A. D., & Jensen, S. Q. (2012). Doing intersectional analysis: Methodological implications for qualitative research. NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 20(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2012.673505

- Clark, N. (2016). Red intersectionality and violence-informed witnessing praxis with indigenous girls. Girlhood Studies, 9(2), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2016.090205

- de Bres, J. (2014). Competing language ideologies about societal multilingualism among cross-border workers in Luxembourg. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2014(227), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2013-0091

- de Bres, J. (2017). Singing is the first thing that came into my head: Emotions and language maintenance among Filipino migrants in New Zealand. In Meredith Marra & Paul Warren (Eds.), Linguist at work. Festschrift for Janet Holmes (pp. 137–158). VUW Press.

- de Bres, J. (2022). Research on parents of gender-diverse children: From pathologization to affirmation. LGBTQ + Family: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/27703371.2022.2058669

- de Bres, J., & Lovrits, V. (2021). Monolingual cringe and ideologies of English: Anglophone migrants to Luxembourg draw their experiences in a multilingual society. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1920965

- Emerson, S., & Rosenfeld, C. (1996). Stages of adjustment in family members of transgender individuals. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 7(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1300/J085V07N03_01

- Field, T. L., & Mattson, G. (2016). Parenting transgender children in PFLAG. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(5), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2015.1099492

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. Routledge.

- Galman, S. C. (2018). This is Vienna: Parents of transgender children from pride to survival in the aftermath of the 2016 election. In C. Kray, H. Mandell, & T. Carroll (Eds.), Nasty women and bad hombres: Historical reflections on the 2016 presidential election (pp. 276–290). University of Rochester Press.

- Galman, S. C. (2020). Parenting far from the tree: Supportive parents of young transgender and gender nonconforming children in the United States. In Brian Ashdown & Amanda Faherty (Eds.), Parents and caregivers across cultures: Positive development from infancy through adulthood (pp. 141–155). Springer.

- Gregor, C., Hingley-Jones, H., & Davidson, S. (2015). Understanding the experience of parents of pre-pubescent children with gender identity issues. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0359-z

- Hidalgo, M. A., & Chen, D. (2019). Experiences of gender minority stress in sisgender parents of transgender/gender-expansive prepubertal children: A qualitative study. Journal of Family Issues, 40(7), 865–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19829502

- Hill, D. B., & Menvielle, E. (2009). “You have to give them a place where they feel protected and safe and loved”: The views of parents who have gender-variant children and adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 6(2–3), 243–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361650903013527

- Howe, J. G. (2022). A rights perspective on parent advocacy for their transgender children in Aotearoa New Zealand school settings [Masters dissertation]. Auckland University of Technology.

- Ishii, Y. (2018). Rebuilding relationships in a transgender family: The stories of parents of Japanese transgender children. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14(3), 213–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2017.1326015

- Johnson, S. L., & Benson, K. E. (2014). “It’s always the mother’s fault”: Secondary stigma of mothering a transgender child. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(1–2), 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.857236

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Budge, S. L., Fugate, E., Flanagan, K., Touloumtzis, C., Rood, B., Perez-Brumer, A., & Leibowitz, S. (2017). Transactional pathways of transgender identity development in transgender and gender nonconforming youth and caregivers from the trans youth family study. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1304312

- Kerekere, E. (2017). Growing up Takatāpui: Whānau Journeys. Tīwhanawhana Trust and RainbowYOUTH.

- Laurence, R. (2020). You’re not coming out – you’ve been there all along and just no one’s looked’: Māori LGBT + youth and identity exploration [master’s thesis]. The University of Waikato.

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2020). Introduction to multimodal analysis (2nd ed). Bloomsbury.

- Lønsmann, D. (2016). Negotiating positionality in ethnographic investigations of workplace settings: Student, consultant or confidante? In G.M. Alessi & G. Jacobs (Eds.) The ins and outs of business and professional discourse research. Communicating in professions and organizations. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lovrits, V., & de Bres, J. (2020). Prestigious language, pigeonholed speakers: Stances towards the ‘native English speaker’ in a multilingual European institution. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 2020, 1–20.

- Machin, D., Caldas-Coulthard, C. R., & Milani, T. M. (2016). Doing critical multimodality in research on gender, language and discourse. Gender and Language, 10(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v10i3.32037

- Manning, K. E. (2017). Attached advocacy and the rights of the trans child. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423917000592

- Meadow, T. (2018). Trans kids. Being gendered in the twenty-first century. University of California Press.

- Mehrotra, G. R. (2022). How We Do the Work Is the Work: Building an Intersectional Queer Praxis for Critical Feminist Scholarship. Affilia: Feminist Inquiry in Social Work: 1–15

- Neary, A. (2021). Complicating constructions: Middle-class parents of transgender and gender-diverse children. Journal of Family Studies, 27(4), 506–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2019.1650799

- Olsen, T. A. (2018). This word is (not?) very exciting: Considering intersectionality in indigenous studies. NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 26(3), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2018.1493534

- Philips, S. U. (1998). Language ideologies in institutions of power: A commentary. In B. Schieffelin, K. Woolard & P. Kroskrity (Eds.), Language ideologies: Practice and theory (pp. 211–225). Oxford University Press.