Abstract

Adolescence is defined as the age range of 10–19 years and it is a transition period from childhood to adulthood. Adolescent girls are vulnerable especially to iron deficiency due to accelerated increase in requirements for iron, poor dietary intake of iron, menstrual losses, infection, norm of early marriage, and adolescent pregnancy. The aim of this study is to assess anemia status and its determinants among adolescent girls in Southern Ethiopia. This research was done in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 30/2019 to May 30/2019. A multistage sampling method was used to select a sample of 843 adolescent girls. Pre-testing of the questionnaire was done on 5% adolescent girls to ensure the reliability of the questionnaire. Finger prick blood sample was collected from all adolescent girls. Hemoglobin level was measured in finger-prick blood samples using a Hemocue photometer which was processed in the field (Hemocue R, Hb 301+ system. Data were entered in the computer using EPI-data version 4.4.2 and exported to SPSS version 21.0 for further analysis. Variables which showed association (p-value ≤ 0.25) in the bivariate logistic analysis were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratios for logistic regression along with 95% confidence interval were estimated. P-values less than 0.05 were declared as level of statistical significance. 820 adolescent girls were participated with a response rate of 97.3. The mean (± SD) blood hemoglobin level of the study participants was 12.23 ± 1.16 g/dL and 37% of the study participants are moderately anemic (Hg 7–12 gm/dl) and 0.2% of the study participants are severely anemic (Hg < 7 g/dL). Overall prevalence of anemia was 37.2% among adolescent girls in the study area. Family monthly income, illness with cough, and malaria in the past two weeks, skipping regular meals, and BMI-for-age are the main predictors of low blood hemoglobin level among adolescent girls in southern Ethiopia. Thus, community-based Iron folic acid supplementation and deworming tablet intervention program should be implemented to help adolescent girls who are at risk of anemia. In addition to these, malaria prevention mechanism and improving family monthly income program should be implemented.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Adolescent girls are vulnerable especially to iron deficiency due to accelerated increase in requirements for iron, poor dietary intake of iron, menstrual losses, infection, norm of early marriage, and adolescent pregnancy. The aim of this study is to assess anemia status and its determinants among adolescent girls in Southern Ethiopia. Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 30/2019 to May 30/2019. Overall prevalence of anemia was 37.2% among adolescent girls in the study area. Family monthly income, illness with cough and malaria in the past two weeks, skipping regular meals, and BMI-for-age are the main predictors of low blood hemoglobin level among adolescent girls in southern Ethiopia. Thus, community-based iron folic acid supplementation and deworming tablet intervention program should be implemented to help adolescent girls who are at risk of anemia.

1. Background

Adolescence is defined as the age range of 10–19 years and it is a period of transition from childhood to adulthood. Adolescence is the most important period of life where growth and development are accompanied by various physical, physiological, behavioral, and social changes. This leads to increased demand for nutrients that in turn could pose high risk of malnutrition (Vashist & Goel, Citation2009). Adolescent age group comprises 20% of the global population (Zhuang et al., Citation2014).

Anemia is a worldwide public health problem, with global prevalence estimated at 24.8%. The majority of the burden of anemia is in developing world, with highest prevalence in Africa and Southeast Asia (Central Statistical Agency ca. Citation2011; WHO, Citation2008). Anemia can be of multiple causes of including iron deficiency, folate deficiency, cancer, hypothyroidism, lead poisoning, toxic chemical exposure, kidney disease, bone marrow not functioning, vitamin deficiency or nutrient absorption issues, HIV, malaria, parasitic infection, enzyme deficiencies, etc. Parasites that are causing anemia are hookworm, whipworm, and schistosomiasis infection (Farid et al., Citation1969). Iron and folate deficiencies are also the most common causes of anemia. Approximately, 50% of cases of anemia are considered to be due to iron deficiency but this can vary depending on context of living environment (Balarajan et al., Citation2011).

Adolescent girls are vulnerable especially to iron deficiency due to accelerated increase in requirements for iron, poor dietary intake of iron, menstrual losses, infection, norm of early marriage, and adolescent pregnancy (Balarajan et al., Citation2011). Study conducted in 2009 in Nepal indicated that the overall prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among adolescent population was 65.6% with the distribution of rural 62.4% and urban 70.0% (Baral & Onta, Citation2009). Similarly, another study conducted in 2012 at Nepal among adolescent girls indicated that the overall prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among adolescent population was 56.3% and among anemic subject the incidence of anemia in male 47.7% and female 52.3 % (Sinha et al., Citation2012). Study conducted in India among adolescent girls indicated that in overall 60% adolescent girls were found to be anemic. The severity of anemia was found to be 18.4% as mild, 41.3% as moderate and 0.4% as severe (Deshpande et al., Citation2013). Another study conducted among adolescent school girls in western Kenya indicated that overall prevalence of anemia was 30.5% (Leenstra et al., Citation2009). Study conducted in Babile district, Eastern Ethiopia among adolescent girls indicated that prevalence of anemia was 32% (Teji et al., Citation2016). In general, the prevalence of anemia in Ethiopia among the age group of 15–19-year-old females ranged from 9.3% to 34.8% (Central Statistical Agency ca. Citation2011). Intervention to prevent iron deficiency anemia should include measures to increase iron intake through food-based approaches (WHO, Citation2006). The government of Ethiopia officially launched the National Nutrition Program (NNP) in 2009, which aimed to reduce malnutrition in Ethiopia by integrating adolescents’ nutrition into community-based health and development programs but faced a number of challenges. The Ethiopian national nutrition program II (2016–2020) incorporated initiatives to improve nutritional status of adolescent girls, but which interventions under which circumstances are effective remains unknown (Bekele et al., Citation2008). Thus, understanding blood hemoglobin level and associated factors is critical to timely address malnutrition in this age group. The objective of the study is to assess anemia status and its determinants among adolescent girls in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia.

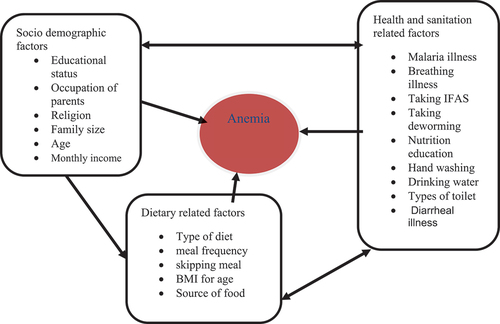

A good understanding of nutritional status of adolescent girls will have many important public health and policy implications. So that, this study will give information to community health workers, ministry of health, ministry of agriculture, and non-governmental organizations that are interested on the safe and effective implementation to improve the hemoglobin level of adolescent girls. Because the findings from this study will has the potential to guide critical health systems planning and strengthen nutrition service policy and program gap at routine health care contacts. The relationship of variables is indicated in below.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area and period

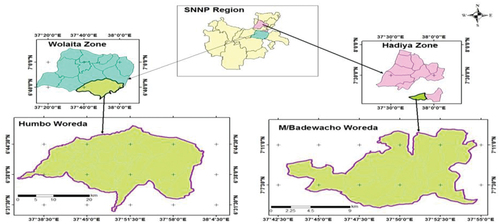

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, southern Ethiopia. These zones are predominantly dependent on agriculture, practicing mixed crop-livestock production, and living in permanent settlements. Within their landholdings, community members cultivate fruits, vegetables, roots, and tuber crops. The study period was from April 30/2019 to May 30/2019.

Map of the study area, 2019

Map of the study area that was developed ARC GIS software, 2019.

2.2. Source population for the study

All adolescent girls (in school and out of school), age within 10–19 years in two zones of Southern Ethiopia were source population for the study.

2.3. Study population for the study

Randomly selected adolescent girls, age within 10–19 years in two zones of Southern Ethiopia who can fulfill the inclusion criteria were the study population.

2.4. Inclusion criteria

All adolescent girls, age within 10–19 years in two zones from southern Ethiopia, who have a willingness to give assent/consent as appropriate and whose guardians/parents have a willingness to provide consent to participate in the study (for participants <18 years) and those adolescents of 19 ages provided informed consent were included.

2.5. Exclusion criteria

All adolescent girls age within 10–19 years in southern Ethiopia who are with mental disability and who have declined to give assent/consent or whose guardians/parents have declined consent were excluded from the study. In addition to these pregnant adolescent girls were excluded.

2.5.1. Outcome variables

Anemia status.

2.6. Independent/predictor variables

Age, educational status of the adolescents girls, family size, maternal and paternal educational and occupational status, distance from health facilities, access to nutritional counseling services in health facilities, deworming tablet, iron-folic acid supplementation, household monthly income, source of food, shortage of food, number of meals per day, alcohol drinking, smoking, chat chewing, presence or absence of latrine, and source of drinking water.

2.7. Sampling procedures

This study used multistage sampling techniques. From 13 zones in Southern Ethiopia, two zones were selected by purposive sampling. These are Wolaita and Hadiya zones. Then, from these selected two zones, two districts were selected using simple random sampling procedure. One district was selected from each zone. These are Humbo district from Wolaita zone and Misrak Badawacho district from Hadiya zone. Three kebeles were selected from each district by simple random method. Census of adolescent girls was conducted at these selected Kebeles. Listing (census) of adolescent girls age ranges within 10–19 years was established with the help of the local government administration and health extension workers. During the listing of adolescent girls, if more than one adolescent girl are available in one household, one adolescent girl was selected by lottery method. Then, 843 participants were allocated to these selected six kebeles depending on the number of adolescent girls in each kebeles. Participants were drawn from each kebeles based on probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling techniques depends on number of adolescent girls in each kebeles. From these lists, 843 adolescent girls were selected by simple random sampling method. The adolescent girls who are not eligible for the study were excluded.

2.8. Hemoglobin screening using finger prick

Adolescent girls were assessed for hemoglobin level. For hemoglobin analysis, finger-prick blood sample was collected by using clean puncture. The experienced laboratory technician trained on the field blood sample collections procedures conducted blood sample collection and hemoglobin analysis at the field level. The prevalence of anemia was calculated based on the hemoglobin levels/standard cut-off points for hemoglobin level measured in finger-prick blood samples using a Hemocue photometer which was processed in the field (Hemocue R, Hb 301+ system). Biological hazards were discarded in hazard box and burned in incinerator at health center.

Adjustment for hemoglobin (Hb) level for altitude was done before defining anemia. The adjustment was done to account for a reduction in oxygen saturation of blood. The following formula was used for adjustment of hemoglobin for high altitude. Hb adjustment = ‐0.032 *(altitude + 03280) + 0.02 *(altitude + 03280)2. Hemoglobin is the amount subtracted from each individual’s observed hemoglobin level.

2.9. Data collection

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was interviewer-administered and developed based on a thorough reviewing different literature.

A total of eight data collectors comprising BSc holder nurses, with previous experience of data collection and who have knowledge of culture, language, and norms of the community were employed to collect data by using pretested structured questionnaire. In addition to this two MSc in public health holder supervisors were employed to supervise data collection process. The collection of data was at weekends for adolescent girls who are at school during weekdays. The principal investigator has controlled the overall study activities in a daily basis.

2.10. Statistical analysis

First, the data were checked for completeness and consistency for data entry and cleaning. Then, data was entered in the computer using EP-data version 4.4.2 and exported to SPSS version 21.0 for further analysis. Frequencies, proportions, and cross-tabulation were used to present the descriptive data. Before analysis, missing value and out liars were checked by drawing histograms. In addition to this, multicollinearity was checked if there was a linear association among explanatory or predictor variables by using variance inflation factor (VIF) assumptions. Multicollinearity refers to the association or relation between two or more independent variables in a multiple regression model. When a variance inflation factor was less than 10, it was taken as tolerable in this analysis. In addition, analyses of bivariate logistic regression were done to assess the association between independent and dependent variables. Variables which showed association (p-value ≤ 0.25) in the bivariate analysis were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratio for logistic regression along with 95% confidence interval was estimated. P-value less than 0.05 was declared as level of statistical significance.

2.11. Data quality assurance

The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated to Amharic and rendered back to English to keep the consistency of the questions. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for 4 days about the proper filling of questionnaire and how to collect blood sample. Data collectors were selected from each zone that can communicate by local language fluently and can understand socio-cultural practice of the community. Pre-testing of the questionnaire was done on 5% adolescent girls in similar area to the study sites to ensure the reliability of the questionnaire. Feedbacks from the pre-test were incorporated into the final questionnaire design. Principal investigator and supervisors have checked on the spot and review all the completed questionnaires to ensure completeness and consistency of the information collected.

2.12. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by Addis Ababa University (AAU), College of Natural Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee. Official letter of cooperation was written to Wolaita and Hadiya zones, and districts of health offices. The nature of the study was fully explained to the study participants and parents/guardians. Informed verbal and written consent was obtained from parents/guardian for adolescent girls ages less than 18 years old and assent was obtained from participant before interview. Participants aged 18 years or older were asked to provide verbal and written consent. Persons with a low hemoglobin level (Hb <12 g/dL) and severe malnutrition were linked to the nearest health facility. The collected data were kept confidential. Code number was given for each participant and the data was stored in secured and password-protected database.

3. Results of the study

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of adolescent girls in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia

Eight hundred and twenty adolescent girls were participated with a response rate of 97.3%. The study participants included in this study were adolescent girls with age ranging from 10–19 years.

As shown in the , the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants include age, occupation and education status, family size, religion, and so on. The average age of the study participants was (mean ± SD) 14.6 ± 1.9 years and their average family size was (mean ± SD) 6.56 ± 1.83 persons, while 69.3 % of the households had more than 5 family members and the rest 30.7% had less than 5 family members. About three-fourth (70%) of the adolescent girls were in 5–8 grade and 23.3% were in 1–4 grade while only 0.5% had no formal education. Most of the adolescent girls are protestant (77.2%), 22.1% are orthodox Christian and only 0.7% are Muslim religion followers. About 33.4% of the adolescent girls are from the households who have less than 1000 ETBirr monthly income and 30.3% are from the households who have greater than 2000 ETBirr monthly income.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia, 2019

3.2. Blood Hemoglobin level of study participants in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia

Mean hemoglobin concentration was 12.23 g/dl, median hemoglobin is 12.30 g/dl, and standard division is 1.16 among study participants. The average blood hemoglobin level of the adolescent girls was (mean ± SD) 12.23 ± 1.16 g/dL.

below indicated that 62.8% of the adolescent girls are normal, i.e. blood hemoglobin level is greater than 12 gm/dl (Hg>12 gm/dl), 37% of the adolescent girls are moderately anemic (Hg is 7–12 gm/dl), and 0.2% of the adolescent girls are severely anemic (Hg<7 g/dL) according to the world health organization, hemoglobin cut-off points for the detection of anemia among study participants (Organization WH, Citation2011).

Table 2. Hemoglobin concentration/level of study participants in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia, 2019

3.3. Association between some variables with hemoglobin level of study participants in Southern Ethiopia

below shows that association between some variables with blood hemoglobin level of the adolescent girls. Blood hemoglobin level was statistically associated with families’ monthly income, taking deworming tablet, educational status of participant’s fathers, ill with cough and malaria illness, skipping regular meals, and BMI for age.

Table 3. Association between some variables with hemoglobin level of adolescent girls in Southern Ethiopia, 2019

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls in southern Ethiopia

The present study conducted in Wolaita and Hadiya zones identified the prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls aged 10–19 years old. The blood hemoglobin level of the adolescent girls revealed that 37.0% of the study participants are moderately anemic and 0.2% of study participants are severely anemic. According to the definition of world health organization, the prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls in the study area is moderately high, because according to world health organization, within 20–39.9 % cut-off point is moderately public health problem (WHO, Citation2004). Our study was supported by the study conducted in three districts of Ethiopia which indicated that anemia prevalence was ranged from 24 to 38% (Gebreyesus et al., Citation2019) and study conducted in Eastern Ethiopia indicated that 32% of adolescent girls were anemic (Teji et al., Citation2016). But low prevalence of anemia (11.1%) was reported from the study conducted in Bahir Dar city administration (Mengistu et al., Citation2019) and southwest Ethiopia indicated that the prevalence of anemia was 15.2% (Tesfaye et al., Citation2015). This low prevalence of anemia might be adolescent girls were from schools and some were from city administration who have relatively high economic status. Similarly, another study conducted in Dembia, Northwest Ethiopia indicated that prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls was 25.5%. Similarly, this low anemia prevalence might be adolescent girls are from only schools and these adolescent girls might be from high-income family (Gonete et al., Citation2018). Another study conducted among adolescent girls in secondary schools in Siaya district of Kenya indicated that 26.5% of adolescent girls are anemic (Nelima, Citation2015). High prevalence of anemia was reported from study conducted at Nepal in 2018 among school adolescent girls (42.5%) and this difference might be due to the study participants are from different socioeconomic and cultural environment (Hamal et al., Citation2018).

4.2. Factors associated with the blood hemoglobin level of the study participants in southern Ethiopia

In this study, blood hemoglobin level of the adolescent girls is significantly associated with family monthly income (p < 0.05). Adolescent girls from family having monthly income less than 1000 ETBirr are 1.7 times more likely to be anemic than families having monthly income more than 2000 EBirr. The monthly income may affect purchasing power of the family and this leads to less access to nutrient-dense food for adolescents to consume. This finding is in line with different studies conducted at south India (Koushik et al., Citation2014), Korea (Kim et al., Citation2014), refugee camp of Somale regional state (Engidaw et al., Citation2018), Bahr dar city administration (Mengistu et al., Citation2019) and Berahle district of Afar region (Adem et al., 2015) which indicated that income was positively associated with anemia status. Similarly, review on anemia indicated that anemia was positively associated with economic status of the family (Balarajan et al., Citation2011; Kim et al., Citation2014). This might be due to low family income to obtain variety of foods rich in iron can be affected.

In this study not taking deworming tablet every six months of the study participants is statistically significantly associated with blood hemoglobin level of adolescent girls. Adolescent girls who were not taking deworming tablet every six months were more likely to be anemic than those who were taking deworming tablet every six months. This might be due to parasites/worm in the small intestine of the adolescents girls may share the nutrient that adolescent girls are using (WHO, Citation2017). This study is in line with the study conducted in 2018 among school adolescent girls at Nepal which indicated that the blood hemoglobin level was significantly associated with taking of deworming tablets (Hamal et al., Citation2018). Similarly, systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that deworming tablet supplementation decrease prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthic infections (Ghogomu et al., Citation2018). In many studies deworming tablet, supplementation decreases anemia prevalence and improves blood iron status (Casey et al., Citation2009; Vir et al., Citation2008; Watthanakulpanich et al., Citation2011).

Educational status of participant’s father is significantly associated with hemoglobin status of adolescent girls. Adolescent girls who are from family whose fathers have not completed college and university education are 1.67 times more likely anemic than adolescent girls whose fathers have completed college and university. Study conducted among school adolescent girls at Nepal in 2018 indicated that the prevalence of anemia was found to be significantly associated with education status of father (Hamal et al., Citation2018). Similar study conducted at Kenya among adolescent girls indicated that educational status of adolescent girl’s fathers was statistically associated with anemia status (Nelima, Citation2015). Another study conducted among school adolescents in southwest Ethiopia indicated that educational status of participants’ fathers is associated with anemia status of the study participants (Tesfaye et al., Citation2015). Possible reason for this association might be educated fathers have good knowledge about nutrition and have awareness to implement nutrition practice. Better educated people may get better information for healthy and nutritious diets (Choi et al., Citation2011; McKay et al., Citation2006). In addition to this, most of educated fathers have good monthly income to have purchasing power for healthy food (Sullivan & Wolla, Citation2017).

Illness with a cough in the past 2 weeks is statistically associated with hemoglobin level of study participants. Study participants who had ill with a cough or breathing problems in the past two weeks are 1.65 times more likely anemic than adolescent girls who have no ill with a cough or breathing problems in the past two weeks. This might be breathing problems was associated with low blood iron status (Cb et al., Citation2012).

Malaria illness can affect hemoglobin level of the study participants. Illness with malaria in the past 2 weeks is significantly associated with blood hemoglobin level of adolescent girls. Adolescent girls who have ill with malaria in the past 2 weeks are 1.85 times more likely anemic than those who have no malaria illness in the past two weeks. Malaria infection was significantly associated with anemia (Asobayire et al., Citation2001; Haidar, Citation2010; Nelima, Citation2015; Sowunmi et al., Citation2017).

Skipping regular meal is significantly associated with hemoglobin level of adolescent girls. Adolescent girls who have skipping their regular meal are 2.25 times more likely anemic than those who are not skipping their regular meals. Skipping regular meal was significantly associated with hemoglobin level (Djokic et al., Citation2010).

In our study body mass index for age is associated with anemia status of adolescent girls. Adolescent girls who have low body mass index for age (thin) are 2.1 times more likely anemic than those who have normal body mass index for age (not thin). This study is in line with the study conducted among adolescent girls at Serbia (Djokic et al., Citation2010) and Bahr dar city administration (Mengistu et al., Citation2019) which indicated that low body mass index for age (thinness) was significantly associated with anemia status of adolescent girls. This might be anemia impairs the physical development (Xiaoliang et al., Citation2009).

4.3. Conclusions

Anemia is found to be moderately a public health problem in the study area. Family monthly income, illness with cough and malaria in the past two weeks, skipping regular meals and BMI for age are the main predictors of anemia among adolescent girls in Wolaita and Hadiya Zone, southern Ethiopia.

4.4. Recommendation

• Thus, community-based deworming tablet supplementation program should be implemented for adolescent girls.

• The inter-sectoral collaboration should be there to implement community-based health and nutrition programs, i.e. schools and agricultural experts should work together with health experts to improve meal pattern of adolescent girls.

• Rural nutrition-sensitive agriculture programs should be promoted through rural agricultural extension programs to improve dietary diversity status.

• At all levels, the girls nutrition education should be given due emphasis as they are tomorrow's mothers which is very important reduction of malnutrition.

• Support from different stockholders should be provided to improve monthly income of the family.

• Malaria prevention mechanism should be implemented in the study area to improve anemia status.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supportinginformation file. English version questionnar.docx

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Addis Ababa University,College of Natural Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee and written consent was obtained from each participants before study begin.

Acknowledgements

Above all, I want to express my heartfelt thanks to the Almighty God, who helped me to accomplish this work and provides His blessing for me throughout my life. I acknowledge the Wolaita and Hadiya zones health office leaders and experts for their valuable cooperation during data collection and I would like to extend my gratitude to all the data collectors who participated in this research and adolescent girls who were willing to participate in this study. I am also grateful to Addis Ababa and Tufts University for facilitation and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yoseph Halala Handiso

Yoseph Halala Handiso (PhD in community nutrition) Assistant professor in School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. Research interest areas are nutrition and food security.

References

- Asobayire, F. S., Adou, P., Davidsson, L., Cook, J. D., & Hurrell, R. F. (2001). Prevalence of iron deficiency with and without concurrent anemia in population groups with high prevalence of malaria and other infections: A study in Cote d’Ivoire. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(6), 776–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/74.6.776

- Balarajan, Y., Ramakrishnan, U., Özaltin, E., Shankar, A. H., & Subramanian, S. (2011). Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 378(9809), 2123–2135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62304-5

- Baral, K., & Onta, S. (2009). Prevalence of anemia amongst adolescents in Nepal: A community based study in rural and urban areas of Morang District. Nepal Medical College Journal: NMCJ, 11(3), 179–182 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20334065/.

- Bekele, A., Kefale, M., & Tadesse, M. (2008). Preliminary assessment of the implementation of the health services extension program: The case of southern Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 22(3), 302–305 https://ejhd.org/index.php/ejhd/article/view/514/376.

- Casey, G. J., Phuc, T. Q., MacGregor, L., Montresor, A., Mihrshahi, S., Thach, T. D., Tien, N. T., & Biggs, B.-A. (2009). A free weekly iron-folic acid supplementation and regular deworming program is associated with improved hemoglobin and iron status indicators in Vietnamese women. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-261

- Cb, B. C., Brussino, L., Ricciardolo, F. L., Cicolin, A., Heffler, E., Bugiani, M., & Rolla, G. (2012). Effect of iron supplementation in women with chronic cough and iron deficiency. International Journal Clinical Practice. 66(11), 1095–1100 https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12001.

- Central Statistical Agency C. (2011). Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr255/fr255.pdf.

- Choi, H.-J., Lee, H.-J., Jang, H. B., Park, J. Y., Kang, J.-H., Park, K.-H., & Song, J. (2011). Effects of maternal education on diet, anemia, and iron deficiency in Korean school-aged children. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 870. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-870

- Deshpande, N. S., Karva, D., Agarkhedkar, S., & Deshpande, S. (2013). Prevalence of anemia in adolescent girls and its co-relation with demographic factors. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 3(4), 235. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8598.123426

- Djokic, D., Drakulovic, M., Radojicic, Z., Radovic, L. C., Rakic, L., Kocic, S., & Davidovic, G. (2010). Risk factors associated with anemia among Serbian school-age children 7-14 years old: Results of the first national health survey. Hippokratia, 14(4), 252 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3031319/pdf/hippokratia-14-252.

- Engidaw, M. T., Wassie, M. M., Teferra, A. S., & Subramanian, S. K. (2018). Anemia and associated factors among adolescent girls living in Aw-Barre refugee camp, Somali regional state, Southeast Ethiopia. PloS one, 13(10), e0205381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205381

- Farid, Z., Patwardhan, V., & Darby, W. (1969). Parasitism and anemia. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 22(4), 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/22.4.498

- Gebreyesus, S. H., Endris, B. S., Beyene, G. T., Farah, A. M., Elias, F., & Bekele, H. N. (2019). Anaemia among adolescent girls in three districts in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6422-0

- Ghogomu, E. T., Suresh, S., Rayco-Solon, P., Hossain, A., McGowan, J., Peña-Rosas, J. P., & Welch, V. (2018). Deworming in non-pregnant adolescent girls and adult women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0859-6

- Gonete, K. A., Tariku, A., Wami, S. D., & Derso, T. (2018). Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among adolescent girls attending high schools in Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Archives of Public Health, 76(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0324-y

- Haidar, J. (2010). Prevalence of anaemia, deficiencies of iron and folic acid and their determinants in Ethiopian women. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 28(4), 359. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v28i4.6042

- Hamal, S., Dhungana, G. P., Shrestha, P., & Kc, N. (2018). Prevalence of anaemia and its associated factors among school adolescent girls in Baglung municipality, Nepal. Global Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 7(5), 1–8. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Govinda-

- Kim, J., Shin, S., Han, K., Lee, K. C., Kim, J., Choi, Y. S. et al. (2014). Relationship between socioeconomic status and anemia prevalence in adolescent girls based on the fourth and fifth. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(2), 253 https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.241.

- Koushik, N., Bollu, M., Ramarao, N., Nirojini, P., & Nadendla, R. (2014). Prevalence of anaemia among the adolescent girls: A three months cross-sectional study. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3(12), 827–836 https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1097547.

- Leenstra, T., Kariuki, S., Kurtis, J., Oloo, A., Kager, P., & Ter Kuile, F. (2009). The effect of weekly iron and vitamin A supplementation on hemoglobin levels and iron status in adolescent schoolgirls in western Kenya. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602919

- McKay, D. L., Houser, R. F., Blumberg, J. B., & Goldberg, J. P. (2006). Nutrition information sources vary with education level in a population of older adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 106(7), 1108–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2006.04.021

- Mengistu, G., Azage, M., & Gutema, H. (2019). Iron deficiency anemia among in-school adolescent girls in rural area of Bahir Dar City administration, North West Ethiopia. Anemia, 2019(1097547), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1097547

- Nelima, D. (2015). Prevalence and determinants of Anaemia among adolescent girls in secondary schools in Yala division Siaya District, Kenya. Universal Journal of Food and Nutrition Science, 3(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujfns.2015.030101

- Organization WH. (2011). Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. World Health Organization.

- Sinha, A., Karki, G. S., & Karna, K. (2012). Prevalence of anemia amongst adolescents in Biratnagar, Morang Dist. International Journal of Pharmaceutical & Biological Archives, 3(5), 1077–1081 https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13013.

- Sowunmi, A., Fatunmbi, B., Akano, K., Wewe, O. A., Agomo, C., Finomo, F., Ebenebe, J., Jiya, N., Ambe, J., Wammanda, R., Ntadom, G., Mokuolu, O., Emechebe, G., Ezeigwe, N., Ayede, A. I., Adewoye, E. O., Gbotosho, G. O., Folarin, O. A., Happi, C. T., … Useh, F. (2017). Factors contributing to anaemia after uncomplicated falciparum malaria in under five year-old Nigerian children ten years following adoption of artemisinin-based combination therapies as first-line antimalarials. BMC Infectious Diseases, 17(1), 781. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2876-9

- Sullivan, J., & Wolla, S. A. (2017). Education, income, and wealth. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Accessed August 2(8), 18. http//:www.ajhtl.com

- Teji, K., Dessie, Y., Assebe, T., & Abdo, M. (2016). Anaemia and nutritional status of adolescent girls in Babile District, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal, 24(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.24.62.6949

- Tesfaye, M., Yemane, T., Adisu, W., Asres, Y., & Gedefaw, L. (2015). Anemia and iron deficiency among school adolescents: Burden, severity, and determinant factors in southwest Ethiopia. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 6, 189. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S94865

- Vashist, B., & Goel, M. (2009). Nutritional status of adolescents in rural and urban Rohtak, Haryana. Health and Population-Perspectives and Issues, 32(4), 190–197 http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20160915.

- Vir, S. C., Singh, N., Nigam, A. K., Jain, R., Tanjong Ghogomu, E., Suresh, S., Rayco-Solon, P., Hossain, A., McGowan, J., Peña-Rosas, J. P., & Welch, V. (2008). Weekly iron and folic acid supplementation with counseling reduces anemia in adolescent girls: A large-scale effectiveness study in Uttar Pradesh, India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 29(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482650802900304

- Watthanakulpanich, D., Maipanich, W., Pubampen, S., Sa-Nguankiat, S., Pooudoung, S., Chantaranipapong, Y., Nirundorn Homsuwan, Yukifumi Nawa and Jitra Waikagul . (2011). Impact of hookworm deworming on anemia and nutritional status among children in Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 42(4), 782 https://www.tm.mahidol.ac.th/seameo/2011-42-4/04-5120.

- WHO. (6-8 April 2004). Assessing the iron status of populations: Report of a joint World Health Organization/centers for disease control and prevention technical consultation on the assessment of iron status at the population level, Geneva, Switzerland, 6-8 April 2004. Assessing the iron status of populations: Report of a joint World Health Organization/centers for disease control and prevention technical consultation on the assessment of iron status at the population level. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2006). Adolescent nutrition: A review of the situation in selected South-East Asian countries. SEA-NUT-163.

- WHO. (2008). Integrating mental health into primary care.

- WHO. (2017). Guideline: Preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. World Health Organization.

- Xiaoliang, Y., Rongwei, Y., Junchi, Z., Lei, J., Jianmeng, L., & Ren, A. (2009). The relationship between anemia and physical development among children at the ages of 3-6 years in 21 counties of China. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu = Journal of Hygiene Research, 38(6), 688–691 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20047223/.

- Zhuang, T., Han, H., & Yang, Z. (2014). Iron, oxidative stress and gestational diabetes nutrients. Nutrients, 6(9), 3968–3980. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093968