?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study estimated the trend and growth rate of teenage pregnancy (TP) among adolescent women aged 15–19 years and further assessed significant change over time as well as associated factors. Five rounds of the Ghana Demographic Health Survey (GDHS) were used involving 5598 (from 1993 to 2014) adolescents. Relative percentage change was estimated, and Modified Poisson multivariate decomposition analysis was employed to assess the risk of TP between two GDHS study points. Decomposition and Poisson regression analysis were used to quantify change and associated significant factors. All analyses adjusted for GDHS design structure (clustering, weighting, and stratification) using Stata 16.1. The prevalence of TP ranged from 13.8% in 2008 to 21.5% in 1993, showing a downward linear trend. The overall growth rate of TP showed a reduction of 8%, however, the percentage change over the period envisage an increasing linear trend. The combined effect due to endowment significantly decreased the log rate of TP prevalence by approximately 219, and 64 over GDHS study points 1993–2014 and 2008–2014, respectively. Throughout GDHS study periods, increasing age of the household head (HH), and the number of women in HH significantly decreased the risk of TP whereas individual age, marital status, and current use of contraceptives significantly increased the risk. TP declined from 1993 to 2014, however, the percentage change depicts an increasing trend. To ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, reducing the high rate of TP is key to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 3.7.

1. Introduction

Teenage pregnancy (TP) is a global public health issue both in highly developed and developing countries with the latter being the most affected (Blum et al., Citation2015; UNICEF, Citation2014; World Health Organisation, Citation2020; Yakubu & Salisu, Citation2018). Annually, an estimated 21 million girls aged 15–19 years in developing countries become pregnant with approximately 12 million of them giving birth (Darroch et al., Citation2016; World Health Organisation, Citation2020).

In Africa, the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy has been reported as 18.8%; the sub-Saharan African region accounts for 19.3% (G. M. Kassa et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, among five countries in Africa, 25.4% of TP prevalence among adolescent women aged 15–19 years exists (Tetteh et al., Citation2020). The current situation of teenage pregnancy in Ghana is not different from other developing countries. The Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) 2014 report indicates that about 14% of pregnancies were amongst adolescents aged 15–19 years. (GSS, GHS & ICF International, Citation2015).

Globally, adolescent pregnancies are more likely to occur in marginalized communities, commonly driven by poverty, lack of education and employment opportunities (UNICEF, Citation2014; World Health Organisation, Citation2020). Several factors contribute to adolescent pregnancies and births. Key amongst them include rural residence, child marriage, not attending school, no maternal or paternal education, and lack of parent to adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues (Bain et al., Citation2020; G. M. Kassa et al., Citation2018; Odimegwu & Mkwananzi, Citation2017; Yakubu & Salisu, Citation2018). Additionally, the experience of physical violence has been established to be associated with TP among adolescents aged 15–19 years (Tetteh et al., Citation2020).

The risks of pregnancy outcomes and related complications are higher among adolescents (Ganchimeg et al., Citation2014). These include; undesirable maternal weight increase, giving birth preterm, pregnancy-induced hypertension, anemia, urinary tract infection, postpartum hemorrhage (Corcoran, Citation2016; Spence, Citation2008), and low birth weight compared to other age groups (Liabsuetrakul, Citation2012). Psychosocially, the effects can be grave. Teenage mothers are likely to fall into demographic categories that predispose them to increased mental health concerns. They become school dropouts (with subsequent lower educational accomplishment and reduced social prospects including abject poverty), have restricted vocational opportunities, experience divorce or separation, and in some cases possible discrimination and denial by family or community members. They also encounter violence, including suicide (as well as suicide ideations) and homicide (O’Brien Cherry et al., Citation2015; Wilson-Mitchell et al., Citation2014).

Due to the aforementioned challenges associated with TP, several initiatives have been undertaken by agencies (UNICEF, UNFPA) and non-governmental organizations in a bid to address the issues. Initiatives such as sexual and reproductive health rights education, sensitization on the use of contraceptives, and the move to prevent child marriages have been implemented (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013; UNFPA, Citation2016). Though some achievements have been made, there is a lot more to be done as various studies indicate TP is endemic in Ghana, especially in the rural areas (Ahinkorah, Hagan, Seidu, Budu et al., Citation2019; Ahinkorah, Hagan, Seidu, Mintah et al., Citation2019; Bain et al., Citation2020). Although some studies have been published regarding the prevalence and determinants of TP in Ghana there is a paucity of data regarding the trends and patterns over the period. This study estimated the growth rate and trend of TP among adolescents women aged 15–19 years using GDHS data from 1993 to 2014. It further assessed the pattern of significant factors associated with TP change over time in a bid to provide direction in future interventional programmes.

Methods

2.1. Study description

The Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data conducted across the then 10 regions were used for this study. DHS are nationally representative household surveys that provide data for a wide range of monitoring and impact evaluation indicators in the areas of population, health, and nutrition. The secondary data was extracted from the second round to the sixth series (1993–2014). The main purpose of the GDHS was to provide information on fertility, family planning, infant and child mortality, maternal and child health, and nutrition. Essentially, the purpose of GDHS is to inform policy decisions and planning, monitoring, and evaluating programmes related to health in general, and reproductive health in particular in Ghana (GSS, GHS & ICF International, Citation2015).

2.2. Study design

The sample obtained in each survey year was obtained using a two-stage stratified (rural-urban differential) cluster sampling design across the then 10 administrative regions in Ghana. The first stage involved selecting clusters consisting of enumeration areas (EAs) independently. The second stage involved systematic sampling from a list of households in all the selected EAs. The number of households enlisted in each EA makes up the EA size. A household was selected and all women aged 15–49 who were either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors who stayed in the household the night before the survey were eligible and those who consented to partake were interviewed in each survey year. Details of the GDHS sampling design can be obtained from the DHS or the GDHS report. The total number of women aged 15–49 years interviewed in 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014 were 4565, 4843, 5691, 4916, and 9396, respectively.

2.3. Study participants

The study involved adolescent women aged 15–19 years to answer the hypothetical idea of the study. The present study considered the individual GDHS women survey and those aged 20 years or more were excluded. In all, the pooled dataset was 5598 adolescents from 1993 to 2014. The individual year’s sample sizes involved were; 803, 889, 1113, 1037, and 1756, respectively, for 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, and 2014, respectively.

2.4. Outcome measures

The main outcome variable was TP among participants. In Ghana, TP is a major public health concern associated with biopsychosocial and economic woes for both mother and child. DHS defined TP as a percentage of reproductive teenage girls who are mothers, pregnant with their first child, and have begun childbearing as cited by Tetteh and colleagues (Tetteh et al., Citation2020). Thus, the case definition concerning TP for this study involved; adolescents who are mothers or pregnant with their first child or have begun childbearing (GSS, GHS & ICF International, Citation2015; Tetteh et al., Citation2020).

2.5. Covariate

Characteristics involved; age of HH; sex of HH (male or female); wealth index of the household (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest); HH size; HH utilities (electricity, radio, television, refrigerator; coded as yes or no); main floor material (cement, any form of carpet, sand/wood); the number of women in HH; region (the then 10 administrative regions in Ghana); place of residence (urban or rural); source of drinking water; and sanitation (coded as unimproved or improved). Other characteristics were, age of adolescent (15–17 or 18–19); educational level (no education, primary, or Secondary/higher); marital status (never married, married, divorced/separated/widowed); religion (Christian, Islam, Traditional/none), currently working, staying with a partner (both coded as no or yes); knowledge on contraceptive (no or yes); awareness of family planning (not aware or aware); attitude toward wife beating (not justified or justified); pattern of contraceptive use (never use or currently/ever use); intention to use contraceptive (intended to use or non-intended to use).

2.6. Data analysis

To estimate the prevalence of TP, the study authors adjusted for the design effect of GDHS (thus, adjusting for the participant’s primary sampling units, stratification, and the sampling weights). The sampling weights were also normalized by adopting the process employed by Tetteh et al. (Citation2020).

After point prevalence estimate of TP for the study periods, we estimated the overall growth rate of TP from 1993 to 2014 by adopting the formula ; where r = growth rate, P1 the current teenage pregnancy (GDHS 2014), and P0 = the past teenage pregnancy (GDHS 1993). Therefore,

; thus

−0.08. In addition, the rate of percentage change within the periods was calculated by adopting the formula

; where c represents the relative change x2 and x1 denote current and initial values, respectively. Point of change was assessed by grouping data into five periods; 1993–1998, 1993/1998-2003, 1993/2003-2008, 1993–2014, and 2008–2014. In all, TP and percentage change estimate linear equation were estimated to identify the pattern of the linear line. This was calculated by adopting the formula;

where y and x are the y-axis and x-axis coordinates, respectively, b is the y-intercept perpendicular to the x-axis and m is the slope of the line (i.e., the ratio of change in y-coordinates and change in x-coordinates). The slop was estimated using the formula

. The risk of TP was assessed in two decomposition sections; endowment (quantifies the amount of TP change due to differences in characteristics between two points in time) and coefficient (the amount of change due to differences in characteristics effect between two points in time).

In addition, bivariate descriptive statistics were performed by adopting the Rao-Scott chi-square to determine a statistically significant difference among adolescent women and how they were involved in GDHS over the years studied. Factors influencing TP for individual GDHS years were determined by using the modified Poisson regression model. Stata 16.1 was used to perform all analyses and a p ≤0.05 was deemed significant. Excel version 2016 was used for plotting graphs.

2.7. Ethical requirements

DHS procedures and questionnaires for standard DHS surveys were reviewed and approved by ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB). ICF IRB ensures that the survey complies with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR 46). The GDHS protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Committee and the Institutional Review Board of ICF International. Individual women’s written consent was obtained during the data collection process for all participants. Privacy and confidentiality were strictly adhered to. Data underlying the results in this study was requested and granted by the Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results Demographic and Health Surveys (MEASURE DHS) department. Request can be obtained from DHS https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/login_main.cfm

3. Results

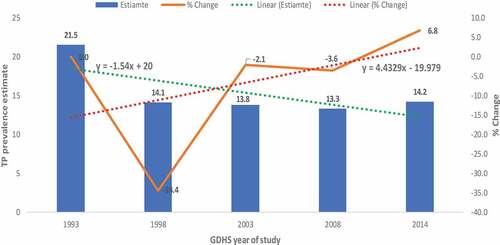

The study involved 5598 adolescent women aged 15–19 over five rounds of GDHS. The prevalence of TP ranged from 13.8% in 2008 to 21.5% in 1993 showing a downward linear pattern. The overall growth rate of TP showed a reduction of 8% from 1993 to 2014; however, the percentage change over the period depicts an increasing pattern (). The independence test of association showed a significant association between participants’ characteristics and involvement in GDHS over the years studied (p ≤0.05) except sex of HH and currently working status (p >0.05) (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence and percentage change of teenage pregnancy among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana from 1993–2014, evidence from GDHS.

Proportional change in TP prevalence showed that the significant decrease in the proportion of TP from 1993 to 1998 was significantly associated with all characteristics studied (p ≤0.05). However, for Upper East residents, primary and secondary or higher educational levels showed an increased change though statistically insignificant (p >0.05). In estimating the change in proportion between the composite prevalence of TP for 1993/1998 and 2003, analysis depicted a significantly decreased prevalence of approximately 4% (%change = −3.8%; 95%CI = −6.9- −0.7). Assessing the difference by factors showed a significant increase in change of TP among poorest wealth index by 8.5% (%change = 8.5%; 95%CI = 0.5–16.5%). In addition, the poorer and middle wealth index showed increased change, however statistically not significant (p >0.05).

Furthermore, the difference in proportion of TP between 1993/2003–2008 and 1993–2014 showed a significant reduction rate [%change (95%CI = −2.8 (−5.5 to −0.6) and −7.4 (−11.2 to −3.5), respectively]; however, the differences between TP prevalence in 2008 and 2014 showed a positive increased rate but insignificant (%change = 9.0%; 95%CI = −2.5–4.3). Meanwhile, the differences by secondary or higher educational level, never married adolescents, not currently working, and intended to use contraceptives showed a significant positive increased rate of TP between 2008 and 2014 ().

Table 1. Percentage change in the prevalence of teenage pregnancy among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana from 1993 to 2014, evidence from GDHS

Results from decomposition analysis showed that the combined effect due to endowment significantly decreased the log rate of TP prevalence by approximately 66, 78, 63, 219, and 64 over GDHS two study points; 1993–1998, 1993/1998–2003, 1993/2003–2008, 1993–2014, and 2008–2014, respectively. Meanwhile, the combined effect due to coefficient has led to an increase in the log rate of TP prevalence by approximately 40, 29, 133, and 63 over GDHS two study points; 1993/1998–2003, 1993/2003–2008, 1993–2014 and 2008–2014, respectively ().

Table 2. Teenage pregnancy decomposition analysis showing endowment and coefficient effect, evidence from GDHS

From the pooled dataset, analysis from the Poisson estimate showed that factors involving the age of HH, wealth index, number of women in HH, region, place of residence, source of drinking water, educational level, marital status, currently working, awareness of FP, contraceptive use and intention to use contraceptive significantly influence TP among participants. The analysis revealed that increasing age of HH significantly decreased the risk of TP by 3% [aPR (95%CI = 0.97 (0.96–0.97)] whiles the higher the wealth-income, the lesser the risk of TP among participants. Meanwhile, an increasing number of HH showed a significant 54% odds of TP [aPR (95%CI = 0.54 (0.44–0.66)] where residing in all regions except Upper West residents showed higher odds of TP. The prevalence of TP among the rural place of residence was approximately 51% more compared with urban residents [aPR (95%CI = 1.51 (1.24–1.83)] and 31% more among the unimproved source of drinking water compared with improved [aPR (95%CI = 1.31 (1.12–1.52)]. Adolescent women aged 18–19 years were over 2-folds likely to experience TP compared with younger counterparts aged 15–17 years [aPR (95%CI = 2.09 (1.70–2.44)].

Intuitively, never married and DSW showed a significant approximately 8-fold risk of TP compared with never married adolescents [aPR (95%CI = 8.15 (6.71–9.82) and 7.89 (6.32–9.84, respectively]. Currently, working adolescents were 1.29 times more likely to have TP compared with those not working(unemployed) [aPR (95%CI = 1.29 (1.15–1.46)], while adolescents who were not aware of FP were 1.35 times more likely to have FP compared with those aware [aPR (95%CI = 1.35 (1.09–1.56)]. Interestingly, who intend to use were more likely to experience TP compared with never used and non-intend to use contraceptive users, respectively [aPR (95%CI = 2.96 (2.39–3.67) and 1.66 (1.31–2.09), respectively] ().

Table 3. Factors influencing teenage pregnancy among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana from 1993 to 2014, evidence from GDHS

4. Discussion

The trend of TP among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana and its pattern of associated factors were examined. Even though the study showed a discreet decline rate of TP from 1993 to 2014, the change in proportions indicated otherwise despite Ghana’s effort at reducing TP. This current study showed similar findings as established by other scholars regarding the declining rate (Buratto et al., Citation2019; G. M. Kassa et al., Citation2019; Lopes et al., Citation2020; Mermelstein & Plax, Citation2016; Vaz et al., Citation2016). However, the hidden finding compared with the aforementioned scholars is the change in TP proportions within the years which showed an increased linear trend. This finding is crucial as it has implications for the global commitment regarding reproductive health as enshrined in the sustainable development goals (SDG 3.7).

Percentage change in the proportion of TP prevalence from 1993 to 1998 showed approximately 7% significant decrease which was associated with all characteristics studied, meanwhile, participants residing in Upper East region, primary and secondary/higher educational level showed an increased change, however insignificant. The change in proportion between the composite prevalence of TP for all the change periods showed a decrease in prevalence, however, the differences between 2008 and 2014 showed a positive increase rate but was insignificant. This finding contradicts a study of trends and determinants of teenage pregnancy in Africa which reported a significant reduction in the African teenage pregnancy rate between 2000 and 2010. This study found an inverse significant relationship with life expectancy, literacy rate, and contraceptive prevalence (Odejimi & Bellingham-Young, Citation2016). From the current analysis, there was a difference of 9% prevalence rate with a percentage increase rate of approximately 7%. The difference in TP prevalence between 2008 and 2014 in relation to secondary or higher educational level, never married adolescents, not currently working, and intended to use contraceptives showed a significant positive increased rate of TP.

One of the key domains listed by WHO in their evidence-based guidelines addressing and preventing TP in low-middle-income-countries (LMICs) is increasing educational opportunities for adolescents (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013). This can be interpreted as TP being a consequence of little or no education. In this current study, the difference in TP between 1993–2014 and 2008–2014 showed a significantly increased change in TP prevalence rate among adolescents with senior or higher educational levels. This finding contradicts other studies. In a systematic review of the association between education and teenage pregnancy in low- and lower-middle-income countries, Mohr et al. (Citation2019) reported that reaching higher levels of education prevents teenage pregnancy in low- and lower-middle-income countries. This current finding undermines what WHO recommends and could be explained by the fact that as adolescent enrollment to senior or higher educational levels increases, the proportion of TP also increases as presented in Supplementary Table 1. For increasing the educational level to prevent TP, comprehensive sexuality education is recommended by WHO (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013).

The trend of TP among never married participants depicts a positive difference between 1993–2014 and 2008–2014. Ending child marriage is key for national development (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013), analysis from this current study showed a significant decline in adolescent marriage in Ghana from 1993–2014 (Supplementary Table 1), with a corresponding linear reduction in TP prevalence. However, what is fascinating is that attention on never married adolescents about TP is lacking in sexuality education, which, in turn, showed a positive difference in TP from 1993 to 2014. The findings corroborate another study that reported a strong relationship between unmarried adolescent pregnancy and lack of knowledge on sexual and reproductive health and non-engagement of adolescents in any productive activity (Moni et al., Citation2013).

Contraceptive use has been recommended as a key intervention to assist reproductive age individuals to achieve their reproductive goals (As-Sanie et al., Citation2004; Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013; GSS, GHS & ICF International, Citation2015). From this current study, the change in TP prevalence between 1993–2014 and 2008–2014 among adolescents who were currently or ever used contraceptives showed an increased change, however, was statistically insignificant. Surprisingly, adolescents who intend to use contraceptives in the future showed a significant positive increase in TP from 2008–2014. This interaction could mean that most adolescents experienced contraceptive failure (Trussell, Citation2009) as non-intend to use showed a significant reduction in TP between all the change periods. Consistent with this, a study of contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy among young women and men in Accra Ghana found that while more than 70% of respondents recognized most modern contraceptive methods, awareness of some methods was lacking. Nearly 91% felt at least one method was unsafe with about 45% reporting their last pregnancy was unintended (Grindlay et al., Citation2018). This could also be attributed to the fact that adolescents may have used less effective contraceptive methods or adolescents may have incorrectly used the methods. Contrary to this argument, the findings of the study contradict other studies which show a reduction in TP as a result of improved use of contraceptives (Lindberg et al., Citation2016; Manlove et al., Citation2016; Santelli et al., Citation2007).

4.1. Teenage pregnancy-associated factors among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana

TP and its associated factors have been established by many authors around the globe (Aguía-Rojas et al., Citation2020; Kaphagawani & Kalipeni, Citation2017; Mathewos & Mekuria, Citation2018; Mchunu et al., Citation2012; Morhe et al., Citation2012; Tetteh et al., Citation2020; Yohannes et al., Citation2018). This current study identified significant factors associated with TP involving HH characteristics (age of HH, wealth index, number of women in HH, region, place of residence, source of drinking water, and individual characteristics (educational level, marital status, currently working, awareness of FP, contraceptive use and intention to use contraceptive).

The analysis revealed that increasing age of HH significantly decreased the risk of TP among adolescents aged 15–19 years in Ghana. This finding was similarly established (Tetteh et al., Citation2020) among five countries in Africa, however, their finding was statistically insignificant compared with the current significant finding. This could be explained by the jurisdiction and the socio-contextual factors of the participants involved.

Income status was established as a significant factor associated with TP in Ghana and, the risk of experiencing TP among adolescents increases as their household wealth income decreases. This finding is not different compared with what other scholars established (Ayele et al., Citation2018; Kaphagawani & Kalipeni, Citation2017; Mchunu et al., Citation2012; Tetteh et al., Citation2020). TP is strongly linked to poverty and lower income is associated with higher teen birth rates (WHO, Citation2020). An increasing number of house hold members showed significantly lower odds of TP and the risk among the rural place of residence was higher compared with urban residents which other researchers collaborate (G. M. Kassa et al., Citation2019; Poudel et al., Citation2018; Tetteh et al., Citation2020; Yohannes et al., Citation2018).

Within the period under consideration, this study identified increasing age of HH, HH size, number of women in HH, age of adolescent, marital status, and current use of contraceptives as significant TP associated factors. This finding confirms that reported by other studies (Asare et al., Citation2019; Mezmur et al., Citation2021; Worku et al., Citation2021). Whereas increasing age of HH and the number of women in HH decrease the risk of experiencing TP among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana; increasing HH size, adolescent women aged 18–19 years, married adolescent women, current/ever use of contraceptive significantly increased the risk of TP from 1993 to 2014. These findings align with the study by Worku and colleagues which also reported that being age 18–19 years, being married, and being from a community with higher contraceptive use were associated with higher odds of TP in a multilevel analysis in East Africa (Worku et al., Citation2021). Similarly, age of adolescents and its association with TP has been immensely studied with findings conforming to this current study (Ayele et al., Citation2018; Buratto et al., Citation2019; G. M. Kassa et al., Citation2019; Tetteh et al., Citation2020; Vaz et al., Citation2016; Yohannes et al., Citation2018). On the contrary, other studies have reported contradicting findings which indicate not using contraceptive is significantly associated with TP (B. G. B. G. Kassa et al., Citation2021) Contraceptive use help individuals achieve their reproductive goals, however, the risk of experiencing pregnancy is very high when not used consistently and correctly, more especially among adolescent (CDC, Citation2015). This current finding underscores that current or past contraceptive use among adolescent women aged 15–19 years in Ghana from 1993 to 2014 highly and significantly predispose them to TP compared with their counterparts who never use a contraceptive. This could be a result of incorrect and inconsistent use of contraceptives among these adolescent women which calls for enhanced sexual and reproductive health education within the community setting.

5. Limitation

As stated under methods, TP was defined as adolescents aged 15–19 years who were mothers or pregnant with their first child or have begun childbearing. Using GDHS data, it was impossible to provide information on other characteristics of the participants likely to influence TP. Marriage was strictly observed to be a highly influential factor associated with TP among participants, however, the limitation was the temporality, that is, marriage before TP or marriage after the TP. These limitations should be dealt with in future studies.

6. Conclusion

TP declined from 1993 to 2014, however, the percentage change in TP between the years depicts an increased linear trend that needs urgent attention. The peak of TP occurred in 1993 with an over 34% sharp decline in 1998. The peak of TP percentage change occurred in 2014 with an approximately 7% sharply increased rate from 2008–2014. Even though TP linear trend depicts a declining rate, the percentage change showed an increased rate. Constant factors associated with increased risk of TP from 1993 to 2014 GDHS involved; adolescent women aged 18–19 years, married adolescents, and currently/ever use contraceptives. To ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, reducing the high rate of TP is key to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), target 3.7.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to DHS and the Ghana DHS team for providing the data for this research work. We thank Miss Augustina Dede Tetteh for her reading expertise and assistance throughout our study and for her help in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The GDHS dataset used for this study is available upon request from https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/login_main.cfm

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguía-Rojas, K., Gallego-Ardila, A. D., Estrada Bonilla, M. V., & Rodríguez-Niño, J. N. (2020). Individual and contextual factors associated with teenage pregnancy in Colombia: A multilevel analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(11), 1376–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02997-1

- Ahinkorah, B. O., Hagan, J. E. J., Seidu, -A.-A., Budu, E., Hormenu, T., Mintah, J. K., Sambah, F., & Schack, T. (2019). Access to adolescent pregnancy prevention information and services in Ghana: A community-based case-control study. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00382

- Ahinkorah, B. O., Hagan, J. E., Jr., Seidu, -A.-A., Mintah, J. K., Sambah, F., Schack, T., & Hormenu, T. (2019). Examining pregnancy related socio-cultural factors among adolescent girls in the komenda-edina-eguafo-abrem municipality in the central region of Ghana: A case-control study. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00093

- As-Sanie, S., Gantt, A., & Rosenthal, M. S. (2004). Pregnancy prevention in adolescents. American Family Physician, 70(8), 1517–1524. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15526738/

- Asare, B. Y.-A., Baafi, D., Dwumfour-Asare, B., & Adam, A.-R. (2019). Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy in the Sunyani municipality of Ghana. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 10, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2019.02.001

- Ayele, B. G., Gebregzabher, T. G., Hailu, T. T., & Assefa, B. A. (2018). Determinants of teenage pregnancy in Degua Tembien District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A community-based case-control study. PLOS ONE, 13(7), e0200898. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200898

- Bain, L. E., Muftugil-Yalcin, S., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., Becquet, R., & de Cock Buning, T. (2020). Decision-making preferences and risk factors regarding early adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: Stakeholders’ and adolescents’ perspectives from a vignette-based qualitative study. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00992-x

- Blum, R. W., & Gates, W. H., & United Nations Population Fund. (2015). Girlhood, not motherhood preventing adolescent pregnancy. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Girlhood_not_motherhood_final_web.pdf

- Buratto, J., Kretzer, M. R., Freias, P. F., Traebert, J., & Nunes, R. D. (2019). Temporal trend of adolescent pregnancy in Brazil. Revista Da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992), 65(6), 880–885. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.65.6.880

- CDC. (2015, April 7). Preventing Teen Pregnancy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/larc/index.html

- Chandra-Mouli, V., Camacho, A. V., & Michaud, P.-A. (2013). WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(5), 517–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.002

- Corcoran, J. (2016). Teenage Pregnancy and mental health. Societies, 6(3), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6030021

- Darroch, J. E., Woog, V., Bankole, A., & Ashford, L. S. (2016). Adding it up: Costs and benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/adding-it-meeting-contraceptive-needs-of-adolescents

- Ganchimeg, T., Ota, E., Morisaki, N., Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., Zhang, J., Yamdamsuren, B., Temmerman, M., Say, L., Tunçalp, Ö., Vogel, J. P., Souza, J. P., & Mori, R., & WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network. (2014). Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A world health organization multicountry study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 121 Suppl 1, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12630

- Grindlay, K., Dako-Gyeke, P., Ngo, T. D., Eva, G., Gobah, L., Reiger, S. T., Chandrasekaran, S., & Blanchard, K. (2018). Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy among young women and men in Accra, Ghana. PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0201663. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201663

- GSS, GHS & ICF International. (2015) . Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. GSS, GHS, and ICF International.

- Kaphagawani, N. C., & Kalipeni, E. (2017). Sociocultural factors contributing to teenage pregnancy in Zomba district, Malawi. Global Public Health, 12(6), 694–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1229354

- Kassa, G. M., Arowojolu, A. O., Odukogbe, A. A., & Yalew, A. W. (2018). Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0640-2

- Kassa, G. M., Arowojolu, A. O., Odukogbe, A.-T. A., & Yalew, A. W. (2019). Trends and determinants of teenage childbearing in Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2000 to 2016 demographic and health surveys. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 45(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0745-4

- Kassa, B. G., Belay, H. G., & Ayele, A. D. (2021). Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenage females in Farta Woreda. 2020: A community-based cross-sectional study. Population Medicine, Vol. 3(July), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.18332/popmed/139190

- Liabsuetrakul, T. (2012). Trends of teenage pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. Thai Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 20(4), 162–165. https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tjog/article/view/4681

- Lindberg, L., Santelli, J., & Desai, S. (2016). Understanding the decline in adolescent fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.024

- Lopes, M. C. D. L., Oliveira, R. R. D., Silva, M. D. A. P. D., Padovani, C., Oliveira, N. L. B. D., & Higarashi, I. H. (2020). Temporal trend and factors associated to teenage pregnancy. Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da U S P, 54, e03639. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2019020403639

- Manlove, J., Karpilow, Q., Welti, K., & Thomas, A. (2016). Linking changes in contraceptive use to declines in teen pregnancy rates. Societies, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6010001

- Mathewos, S., & Mekuria, A. (2018). Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among school adolescents of Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 28(3), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v28i3.6

- Mchunu, G., Peltzer, K., Tutshana, B., & Seutlwadi, L. (2012). Adolescent pregnancy and associated factors in South African youth. African Health Sciences, 12(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v12i4.5

- Mermelstein, S., & Plax, K. (2016). Contraception for adolescents. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics, 2(3), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-016-0053-9

- Mezmur, H., Assefa, N., & Alemayehu, T. (2021). Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in Eastern Ethiopia: A community-based study. International Journal of Women’s Health, 13, 267–278. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S287715

- Mohr, R., Carbajal, J., & Sharma, B. B. (2019). The influence of educational attainment on teenage pregnancy in low-income countries: A systematic literature review. Journal of Social Work in the Global Community, 4(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.5590/JSWGC.2019.04.1.02

- Moni, S. A., Nair, M. K. C., & Devi, R. S. (2013). Pregnancy among unmarried adolescents and young adults. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India, 63(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0244-7

- Morhe, E. S. K., Tagbor, H. K., Ankobea, F. K., & Danso, K. A. (2012). Reproductive experiences of teenagers in the Ejisu-Juabeng district of Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 118(2), 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.035

- O’Brien Cherry, C., Chumbler, N., Bute, J., & Huff, A. (2015). Building a “better life”: The transformative effects of adolescent pregnancy and parenting. SAGE Open, 5(1), 2158244015571638. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015571638

- Odejimi, O., & Bellingham-Young, D. (2016). Teenage pregnancy in Africa: Trend and determinants in the 21 st century, 1(1), 12–20. http://hdl.handle.net/2436/619916

- Odimegwu, C., & Mkwananzi, S. (2017). Factors associated with teen pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country cross-sectional study. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 20(3), 94–107. Article 3 https://ajrh.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/174

- Poudel, S., Upadhaya, N., Khatri, R. B., & Ghimire, P. R. (2018). Trends and factors associated with pregnancies among adolescent women in Nepal: Pooled analysis of Nepal demographic and health surveys (2006, 2011 and 2016). PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0202107. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202107

- Santelli, J. S., Lindberg, L. D., Finer, L. B., & Singh, S. (2007). Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: The contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169

- Spence, N. J. (2008). The long-term consequences of childbearing: Physical and psychological well-being of mothers in later life. Research on Aging, 30(6), 722–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027508322575

- Tetteh, J., Nuertey, B. D., Dwomoh, D., Udofia, E. A., Mohammed, S., Adjei-Mensah, E., & Yawson, A. E. (2020). Teenage pregnancy and experience of physical violence among women aged 15-19 years in five African countries: Analysis of complex survey data. PLOS ONE, 15(10), e0241348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241348

- Trussell, J. (2009). Understanding contraceptive failure. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 23(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.11.008

- UNFPA. (2016) . Situational analysis of adolescent girls and young women in Ghana-synthesising data to identify and work with the most vulnerable young women. United Nations Population Fund.

- UNICEF. (2014, July 22). Ending child marriage: Progress and prospects. https://data.unicef.org/resources/ending-child-marriage-progress-and-prospects/

- Vaz, R. F., Monteiro, D. L. M., & Rodrigues, N. C. P. (2016). Trends of teenage pregnancy in Brazil, 2000-2011. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira, 62(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.62.04.330

- WHO. (2020, January 31). Adolescent pregnancy. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy

- Wilson-Mitchell, K., Bennett, J., & Stennett, R. (2014). Psychological health and life experiences of pregnant adolescent mothers in Jamaica. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(5), 4729–4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110504729

- Worku, M. G., Tessema, Z. T., Teshale, A. B., Tesema, G. A., & Yeshaw, Y. (2021). Prevalence and associated factors of adolescent pregnancy (15–19 years) in East Africa: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03713-9

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Adolescent pregnancy. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy

- Yakubu, I., & Salisu, W. J. (2018). Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4

- Yohannes, A. H., Yalew, A., & Telake, A. B. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with teenage pregnancy, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Pregnancy, 2018, 1714527. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1714527