Abstract

The focus of the manuscript is on unique stressors and mental health challenges faced by professional ice hockey enforcers during their careers and how these stressors, when combined with a history of neurotrauma, may affect functioning post-career. It was hypothesised that participants would have several challenges with mental health caused by repetitive exposure to concussive and sub-concussive events consistent with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) symptomology. Ten retired professional ice hockey enforcers were interviewed to identify whether they experienced stressors or mental health challenges post-career. A mixed methods approach was utilised to develop descriptive and emergent themes and their frequencies. Participants reported a number of stressors unique to the enforcer role. Their response to these stressors was mediated by whether they embraced or tolerated/accepted the enforcer role. Two participants reported being diagnosed with depression with another stating that he had felt periods of sadness in the past. This pattern of results did not support the hypothesis. While there is some evidence to suggest that ex-professional hockey enforcers have challenges with mental health post-career, the prevalence is consistent with the estimates in the general population and with other elite athletes in other sports.

1. Introduction

Elite athletes are often presented by media and corporate sponsors as examples of fitness and health. As such, they may not be perceived as vulnerable to challenges to mental health. Consistent with this perspective, some research evidence suggests that athletes could be less prone to mental health disorders. For example, regular exercise has been associated with positive mental well-being (Stanton & Reaburn, Citation2014) and has been prescribed as a treatment for depression (Bornheimer & Gangwisch, Citation2009). In addition, it has been historically assumed that a person with mental health challenges would have difficulty being competitive at the highest level in sport (Brosse et al., Citation2002; Sarah et al., Citation2017).

However, there have been a number of high-profile case reports and deaths of elite athletes who had issues with mental health. In Canada, highly publicized deaths have occurred in the sport of ice hockey. In 2011, columnist Bruce Arthur wrote of the “wretched summer” (Arthur, Citation2011) when three National Hockey League (NHL) enforcers died by suicide or accidental death including overdose. What remains unclear is what caused three athletes with similar roles within the sport to lose their lives within months of each other? Some clinicians, scientists, and members of the media have speculated that given their roles as enforcers, fighting in hockey could be the common element. In other words, the elevated exposure to neurotrauma embedded within the role of enforcer led to concussions, depression, and accidental death or suicide (Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015; Larsen, Citation2017; Strong, Citation2019).

Therefore, are elite ice hockey enforcers at greater risk of developing challenges with mental health because of their unique role in ice hockey? To begin to address this issue, we must first understand the base rates for mental health challenges in the general population. The World Health Organization (World Health Organisation, Citation2017) estimates that globally, more than 322 million people suffer from some form of depression. The National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.) stated that in 2017, 17.3 million U.S. adults aged 18 or older had at least one major depressive episode (7.1%), that more females (8.7%) had depression compared to males (5.3%), and that the age range most affected was those 18–25 years (13.1%; National Institute of Mental Health, Citation2020a). The 12-month prevalence of depression for men born in the U.S. aged 25–74 years falls between 4.3–13.9% with a lifetime prevalence of between 21.9–28.1% (González et al., Citation2010). It has been reported that higher levels of depression may occur among male workers in male-dominated workforce groups compared to the general population (Roche et al., Citation2016).

Global estimates of suicide range between 9–14 per 100,000 persons and suicide occurs more frequently in males (Michael et al., Citation2016). Suicide risk has been shown to increase slightly following a mild traumatic brain injury with an adjusted risk of between 1.27 (Michael et al., Citation2016) and 1.81 (Trine et al., Citation2018) with more sensitive predictors being low income, a history of mental illness, being male, a history of substance abuse, prior hospital admissions, and a previous suicide attempt (Michael et al., Citation2016).

Regarding anxiety disorders, the World Health Organization estimated that 264 million people are living with anxiety disorders accounting for 3.6% of the world’s population. It was also stated that anxiety disorders are more common among females (4.6%) than males (2.6%; World Health Organisation, Citation2017). The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that 19.1% of U.S. adults had an anxiety disorder over the span of one year and that the prevalence of any anxiety disorder was higher for females (23.4%) than for males (14.3%), with an estimated 31.1% of adults experiencing an anxiety disorder at some time in their lives (National Institute of Mental Health, Citation2020b).

It has been shown recently that athletes are not immune to mental health challenges during their careers. In fact, it may be the case that they are at equal or even greater risk to mental health challenges compared to the general population based on risk factors specific to being an elite athlete (Reardon et al., Citation2019; Sarah et al., Citation2017; Wolanin et al., Citation2015). For example, Danish and Swedish male elite football players had a prevalence rate for depressive symptoms of 16.7% mediated by factors such as perfectionism, competitive anxiety, and social phobia (Nylandsted Jensen et al., Citation2018). A study on elite athletes in New Zealand found that 21% had moderate depressive symptoms and 8.6% had scores indicative of a possible major depressive episode (Sarah et al., Citation2017). In Swedish athletes, the point prevalence of mental health problems significant enough to affect work and quality of life occurred in 11.7% of participants with a lifetime prevalence of over 50% (Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020). Estimates in Australia (Gulliver et al., Citation2015) and the U.K. (Foskett & Longstaff, Citation2018), and for those involved in team sports (Reardon et al., Citation2019) have also shown nearly 50% prevalence rates for mental disorders. However, when taken in its entirety, most agree that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in elite athletes may be slightly elevated based on specific factors (including concussion—see, Gray et al., Citation2015) but that it mirrors rates in the general population (Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020; Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Reardon et al., Citation2019).

Some have questioned whether prevalence rates for mental disorders increase when athletes retire. A number of studies suggest that rates of mental health disorders are higher in retired athletes compared to the general population (Gouttebarge et al., Citation2016a, Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2016b). Similar to athletes during their career, a history of multiple concussions has been linked to the prevalence of mental health challenges during retirement (e.g., Guskiewicz et al., Citation2007; Kerr et al., Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2020) and has also been considered to increase the risk of suicide following retirement (e.g., Azad et al., Citation2016; Baum, Citation2005; Bennet et al., Citation2011; Omalu et al., Citation2010).

In Canada, much of the narrative regarding post-retirement challenges to mental health in ice hockey players has been centred on how concussions may cause Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) which can manifest as depression, anxiety, and in some cases result in suicide. The athletes targeted for discussion oftentimes are ex-professional ice hockey enforcers. The link drawn between neurotrauma and negative outcomes has been subtle in some cases (Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015) but has also been very direct (Larsen, Citation2017; Strong, Citation2019). Research evidence for a link between concussion and negative post-retirement outcomes in ex-professional ice hockey players is limited but does exist. For example, in a qualitative study of five National Hockey League (NHL) players forced to retire due to medically diagnosed concussions, participants described several challenges to mental health including altered mood, personality changes, feelings of isolation, stress, confusion, depression, anxiety and paranoia, and suicidal ideation (Caron et al., Citation2013). This has led some to describe the potential link between concussions and negative post-retirement outcomes as a “concussion crisis in the NHL” (Miller & Wendt, Citation2015).

The broader base of research that supports a link between concussion in retired ice hockey enforcers and negative post-retirement outcome can be found within the CTE literature. Most of the athletes in these studies participated in American Football with a small number of ice hockey athletes included (e.g., McKee et al., Citation2018). CTE scientists have stated that a single blunt force episode may be sufficient to cause pathophysiology (Bennet et al., Citation2011) with others stating that repetitive concussive or sub-concussive events are required (Armstrong et al., Citation2016; Huber et al., Citation2016; Omalu et al., Citation2010; Stern et al., Citation2016). Therefore, exposure to fighting in ice hockey can be considered a significant risk factor.

The conclusions drawn by CTE scientists have recently been challenged. One point of criticism has been the yet unverified link between CTE pathophysiology and symptomology (Castellani, Citation2015; G.L. Iverson et al., Citation2015). It has been noted that the source of CTE symptomology may be multifactorial and unrelated to neurotrauma specifically (Iverson et al., Citation2015; Gaetz, Citation2017). In addition, CTE pathophysiology has also been found in persons without a history of neurotrauma (Iverson et al., Citation2019). Further, the scientific merit of these studies has been criticised because most CTE studies are based on the review of individual cases obtained via donation or active solicitation by CTE researchers (e.g., Branch, Citation2014).

The Athlete Post-Career Adjustment (AP-CA) model (Gaetz, Citation2017) was developed to help to understand post-career functioning of athletes beyond the consequences of concussion. The AP-CA model states that four factors may be related to significant negative outcomes following retirement from contact sport: neurotrauma, chronic pain, substance use, and career transition stress. In addition, depression can be a chronic lifelong co-morbid condition that may be present prior to an athletic career or may be developed secondary to any of the model elements (Gaetz, Citation2017). The purpose of this study is to utilise the AP-CA framework to explore the lived experiences of ex-professional ice hockey enforcers regarding the problems they may experience post-retirement. A previous manuscript (Gaetz, Citation2021) described the concussion history, levels of chronic pain, and post-career functioning in this sample. The focus of the current manuscript will be on challenges to mental health that occurred during their careers as well as post-career. Based on the current perspective in the scientific literature and media, it was hypothesised that ex-professional ice hockey enforcers would have a number of challenges with mental health caused by repetitive exposure to concussive and sub-concussive events consistent with CTE symptomology.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Methodology and philosophical underpinnings

The study employed two forms of mixed methodologies and has been previously described by Gaetz (Citation2021). The first mixed methodology approach has been termed “two-eyed seeing”. Martin Debbie (Citation2012) proposed two-eyed seeing is a methodologic framework that approaches science through the lens of Indigenous knowledge as well as a Western science lens. Two-eyed seeing proposes that by acknowledging and respecting Indigenous and Western perspectives, a new way of understanding is produced that respects the strengths that each perspective can offer (Botha Citation2011; Chilisa and Tsheko Citation2014; Martin Debbie, Citation2012; Richardson Citation2015; Sanchez, Letiecq, and Ginsberg Citation2019). The current study also employed a quantitative and qualitative mixed methods approach (Bryman Citation2006; Bryman Citation2007; Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013; Hesse-Biber Citation2010; Hesse-Biber and Johnson Citation2015; Norwich Citation2020). The philosophical underpinning of this approach aligns with Deweyan pragmatism (Feilzer Citation2010; Hall Citation2013; Johnson et al. Citation2017; Norwich Citation2020). Therefore, in this study, the “Western” lens utilises both Deweyan pragmatism and descriptive quantitative methods. On the other hand, the “Indigenous” lens is based within an Indigenous qualitative approach, secondarily informed by feminist constructs, all based within a relational epistemology (Bird-David Citation1999; Brownlee and Berthelsen Citation2008; Causadias, Updegraff, and Overton Citation2018; Chilisa and Tsheko Citation2014; Elliot-Groves Citation2019; Held Citation2019; Kawagley Citation1993; Kovach et al. Citation2014; Marin, Medin, and Ojalehto Citation2017; Martin Debbie, Citation2012; Sanchez, Letiecq, and Ginsberg Citation2019; Sonn and Quayle Citation2012). Relational epistemology values a highly developed sense of social consciousness characterized by the responsibilities inherent in each relationship (Kawagley Citation1993) with knowledge distributed through collective human networks (Held Citation2019) by story and narrative (Richardson Citation2015).

Interestingly, Deweyan pragmatism (DP) shares several philosophical elements with Indigenous methodology (IM). For example, both IM and DP discuss intuition as central to the process of inquiry (Botha Citation2011; Johnson et al. Citation2017; Kawagley Citation1993; Richardson Citation2015). Both perspectives value the ethics of the research over the requirements of a specific methodologic perspective (Cochrane et al. Citation2008; Hall Citation2013; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Weber-Pillwax Citation2001). IM and DP value the shared history of people or “story” within their specific communities (d´ Ishtar Citation2005; Elliot-Groves Citation2019; Hall Citation2013; Johnson et al. Citation2017; Kawagley Citation1993; Kovach et al. Citation2014; Martin Debbie, Citation2012; Richardson Citation2015). Both perspectives value reflexive and reciprocal communication between the participant and researcher (Bird-David Citation1999; Chilisa and Tsheko Citation2014; d´ Ishtar Citation2005; Elliot-Groves Citation2019; Martin Debbie, Citation2012; Richardson Citation2015). Finally, both perspectives are action oriented (Elliot-Groves Citation2019; Hall Citation2013; Kovach et al. Citation2014; Martin Debbie, Citation2012).

Unlike qualitative approaches that consider knowledge generated by the researcher at an equal or even greater level of prominence as the participant (e.g., Bell, Kothiyal, and Willmott Citation2017; Larkin et al., Citation2006; Smith Citation1996; Smith Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation1999; Smith and Osbourne, Citation2009), this study takes a “participant as expert approach” (Hesse-Biber Citation2010; Chilisa and Tsheko, Citation2014; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Dey, Singh, and Gupta Citation2018; Ingram et al. Citation2011). In this type of research, the participants’ stories are the teachers (Kovach et al Citation2014). “Listening to hear” rather than “listening to respond” was an important principle during interviews (Chilisa and Tsheko Citation2014; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Kovach et al. Citation2014). In summary, the study employed a participant centred approach that attempted to maximise the opportunity for participants to accurately express their perspectives based on their lived experiences (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Kovach et al. Citation2014; Martin Debbie, Citation2012; McGloin Citation2015) and minimise the known issues associated with researcher bias and editorialisation (Svenson et al. Citation2018; Wilson, Shipley, and Davatzes Citation2020). The primary role of the researcher then was to listen and then integrate and contextualise the participant’s experiences within the existing research literature.

2.2. Participants and researcher

The participants in this study have been described previously (Gaetz, Citation2021). A total of 10 retired professional ice hockey enforcers agreed to participate in face-to-face interviews and represented a reasonably homogenous, purposive sample. Participant age ranged from 31–61 years (mean = 48.9). All participants were drafted by National Hockey League (NHL) teams. Seven participants were employed by the NHL with the remainder having careers in the American Hockey League (AHL). The length of career in professional hockey ranged from four to 15 years (mean = 10). The range in calendar years for careers in professional hockey was from 1978–2014. Two participants were Calder Cup champions (AHL Championship) and two were Stanley Cup champions (NHL Championship).

Hockey fights occurred in minor hockey, junior hockey, and professional hockey games and practices. Fights that occurred outside of hockey were not included in fight totals for this study. The first reported hockey fight occurred between the ages of 10–18 years (mean = 15). Two participants had estimated approximately 100 career fights with six reporting over 200 career fights (range 100–250; mean = 218.5).

All participants were employed at the time of interview in occupations that included being employed in professional hockey as coach, general manager, or scout, upper management in a resource-based industry, founder of a non-profit organization following several years of coaching in professional hockey, firefighter, sales, owner operator of a number of successful businesses as well as being an NHL scout, and a radio and television media broadcast personality for an NHL team.

The author is a white settler who has lived on the traditional lands of the Blackfoot, Tsuu T’ina and Stoney Nakoda, Cree, and Dakota Sioux people, and who currently lives and works on the traditional lands of the Stó:lō people. Each indigenous group has impacted the author’s value systems and ways of understanding the world. The author has been studying and publishing on concussion assessment and management in ice hockey for approximately 30 years. He has developed a theoretical model to explain the negative experiences that some athletes face post-retirement. He has extensive experience in amateur ice hockey as a player, coach, and as a member of a sport science team within junior hockey in Canada. He shares a common cultural and geographical history with the participants and as such, was able to develop a good rapport based on a common cultural history and knowledge of the sport.

2.3. Procedure

This study is a part of a broader ongoing research project and is based on semi-structured interviews from 10 former professional ice hockey enforcers. In this study, a “hockey fight” was operationally defined as participation in a fight between two players where a five-minute major penaltyFootnote1 was assed to the participant for “fighting” during games. A fight during practice resembled a fight that occurred during games but with no penalty assessed. Both were included as hockey fights in this study. An “ice hockey enforcer” was operationally defined as a professional ice hockey player whose role on the team included bareknuckle fighting in a hockey game or practice, was recognized by other enforcers as someone who had this role and had a minimum of 100 fights total in amateur and professional hockey. A “professional” was defined as a player who had signed a professional contract with a hockey organisation and had played professionally for at least one season. Participant recruitment was done initially by convenience sampling with snowball sampling utilised once the contact information of ice hockey enforcers who were willing to participate in the study was provided. The ethics of the research were reviewed and approved by the University Human Research Ethics Board.

The interview guide was developed to elicit conversation that encompassed the issues surrounding concussions in ice hockey as well as other factors that may affect post-career functioning (Gaetz, Citation2017). The semi-structured interview was composed of 15 questions as well as follow-up prompts. In an effort to hear the stories, a reflexive conversational approach was employed (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Kovach et al. Citation2014). The interview was premised with a general statement that the purpose of the study was to allow participants to provide their perspective about their role in ice hockey and the potential negative outcomes that they have heard about in the media and biographical accounts. This signalled to the participants that they were in a position of expertise and power regarding the eventual results. In other words, an ethical position was established that shifted focus to the participant (d´ Ishtar Citation2005; Kovach et al., Citation2014). Two questions were more specific to the lifetime prevalence of mental health challenges: 1) Do you have any bad memories or images related to your time as an enforcer? and 2) Have you ever had periods of your life where you felt sad or down? Follow-up: Have you ever been diagnosed with, or have been suspected to have, depression? Follow-up: If so, when did this start and how does it affect you currently?

One-on-one in person interviews were conducted at a location mutually agreed upon by the participant and researcher. The locations of the interviews included five Canadian provinces and two states within the United States. The duration of the interviews was between 25–99 minutes (mean = 60.9). The consent process occurred immediately prior to the interview and included a review of the consent letter, an opportunity for questions and clarification, followed by written consent. It was stressed that the information provided would be treated in a confidential manner and that any content that would link a response to a specific participant would be anonymised.

Each interview was audio-recorded using both a Panasonic RR-US551 recorder and a Samsung Galaxy 4 smartphone. Digital audio files were deleted from the primary devices once transferred to the password encrypted personal computer of the researcher. The digital audio files were transcribed verbatim by the researcher or a student research assistant. Once transcription for each file was complete, the transcripts were sent to the personal email of the participants for review and editing if necessary. This “member checking” has been criticised as an index of rigor (Smith and McGannon Citation2018). Nonetheless, it was utilised to ensure that the ethical responsibilities of the researcher were met (Parr 2015) and that participants were confident that their responses aligned with their beliefs and that they had time to reflect on and change their comments as required. When changes were requested, the transcript was edited and sent back to the participant for review and approval prior to analysis. Once the transcript was approved, the digital audio file was deleted. Non-descriptive labels were used for each participant (e.g., P1). Player, city, and team names were anonymised (e.g., NHL City).

2.4. Data analysis

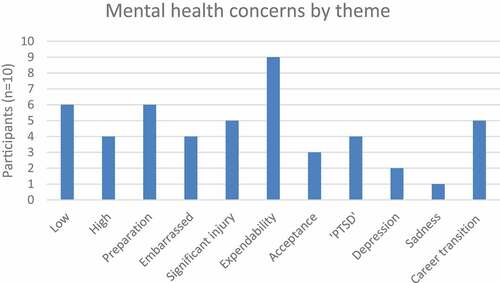

Mixed methods research has been recognized by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) as beneficial for the comprehensive understanding of health issues (NIH Citation2018). The strategy for the use of a mixed methods in this study was to initially quantify the nature and frequency of the mental health challenges (Table —Descriptive Themes) sustained by participants during their careers within the empirically derived primary categories “Anxiety”, “PTSD”, and “Depression” (Table ). This quantitative frequency analysis (Figure ) transformed qualitative responses from interview transcripts into variables describing injury characteristics (Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013). Therefore, the descriptive themes provided a contextual basis for the qualitative thematic development to follow (Bryman Citation2006).

Table 1. Thematic organisation based on comments associated with anxiety, “PTSD”, and depression as well as descriptive and interpretive themes

Figure 1. Frequency of mental health concerns by theme (Low = 3.1.1 Low—“liked it/good at it”; High = 3.1.2 High—Accepted/Tolerated the role; Preparation = 3.2.1 Preparation to fight; Embarrassed = 3.2.2 Being embarrassed; Significant injury = 3.2.3 Significant injury; Expendability = 3.2.4 Performance and expendability; Acceptance = 3.2.5 Parental acceptance; “PTSD” = 3.3 “PTSD”; Depression = 3.4.1 Diagnosed depression; Sadness = 3.4.2 Undiagnosed periods of sadness; Career transition = 3.4.3 Periods of depression/emotional distress related to career transition).

In some cases, qualitative analysis involved the development of interpretive themes based on the descriptive themes (Table ; Figure ). The thematic development was informed by Indigenous methodologies with a focus on recurring concepts within the conversations guided by relational epistemology (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2008; Kovach et al. Citation2014) as described in section 2.1. The method used for thematic analysis was that of Braun, Clarke, and Weate (Citation2016). This form of thematic analysis allows the researcher to identify and interpret patterns of responses independent from a specific ontological and epistemological framework. The process of thematic development adhered to the prescribed steps of Familiarization, Coding, Theme development, Refinement and Naming (Braun, Clarke, and Weate, Citation2016). The development of descriptive quantitative themes followed by more substantial interpretive themes is consistent with an explanatory sequential design where the qualitative component is employed to try to explain or contextualize the earlier quantitative results (Creswell Citation2015; Creswell and Piano Clark, Citation2007; Fetters, Curry, and Creswell Citation2013; Hesse-Biber Citation2010; Hesse-Biber and Johnson Citation2015).

2.5. Research quality and methodological rigor

The research was conducted as per NIH best practices for mixed methods research in health sciences (NIH Citation2018). Operational definitions are provided as well as a clear hypothesis. Consistent with IM, there was continuous reflection on how the results could impact lives of people via consequential validity (Hall Citation2013; Johnson et al. Citation2017; Kovach et al. Citation2014). Rigor as per Braun, Clarke, and Weate (Citation2016) was demonstrated in multiple ways. The number of participants exceeded the suggested minimum sample size of six and utilised the 15-point “checklist” for a good thematic analysis. The study incorporated Yardley’s (2000) suggestions for good quality qualitative research including in depth coverage of the relevant literature, having a theoretical basis (Gaetz, Citation2017), transparency in methods, and having an impact to theory and impact for those involved in contact sport. Finally, consistent with Smith and McGannon (Citation2018) member checking was utilised as a part of ethical practice, but not as an index of rigor. Issues with interrater reliability were avoided during the interview or coding process because all work was completed by the author.

3. Results

3.1. Anxiety state range

3.1.1. Low—“liked it/good at it”

Professional ice hockey enforcers are often stereotyped as “goons” that relish their role. As with most stereotypes, the generalization does not adequately capture the differences between participants regarding how they perceived their role and the ease or difficulty with which it was carried out. Although not specifically queried, a theme emerged regarding the degree to which having to fight on a regular basis caused an anxiety state in some participants and much less concern in others. Six of 10 participants indicated that they embraced the role and as a result, did not report being bothered by having to fight on a regular basis. At times, this was stated very simply: “for me … it wasn’t like I was scared of it … I was good at it” (P1). Another stated: “I think I was … fairly good at … I felt confident doing it. I did it out of emotion … ” (P3). P4 added:

‘I got in a couple of scraps and … I did pretty well and … I kind of enjoyed it. It was a lot of fun, and … you think, when you start doing that and, and things go well for you, you think you’re the toughest thing since sliced bread. And uh, that’s the way you looked upon it is that uh, you were invincible, no question.’

P5 explained it this way: “I can’t say it, it bothered me, I knew what my job is and I just like, you just got to go do it. Sometimes that’s not easy but um … I didn’t worry about it … ”

3.1.2. High—Accepted/Tolerated the role

It is important to note that all participants were considered skilled players during their developmental ice hockey years. However, at some point, they realised that if they wanted to continue to a professional career in ice hockey, they would have to add fighting to their repertoire. Participants who accepted or tolerated the role may have been very good at their job but would have preferred to have a non-fighting role rather than being an enforcer. Four of 10 participants provided comments consistent with tolerating the role of enforcer. For example, P2 commented “it was part of my game and I didn’t mind doing it … if I could have a different role … if I could be a goal scorer, I’d rather have that”. P9 added “You know my role, I had to, because of the style I played, I answered the bell out of respect to certain guys. Which, I didn’t like doing that either but I had to because that’s how I gained their respect too.” P10ʹs comments reveal that there were consequences for not “embracing” the enforcer role as much as a coach or general manager wished:

‘it wasn’t so much that I didn’t like fighting, I didn’t, it was, fighting was always a by-product of playing hockey and playing hard. … if it’s a game that was really chippy and you know maybe it’s an emotional thing OK but, just to do it to do it, I never did it. Um, you know, in a large part like early in my career I got traded and passed around for a bunch of teams early on partly for that reason.’

3.2. Anxiety provoking factors

3.2.1. Preparation to fight

There were several aspects of the role of enforcer that caused anxiety states in participants. This is not to say that it only bothered those who tolerated the role, but for those participants it seemed to cause concern more often and more substantially. For example, six of 10 participants made comments indicating that more preparation went into thinking about the next game. As P2 put it, “I was definitely … up late at night watching video on the other team I’m playing. Then before the game I’m watching video on their top three fighters in case I have to fight them … ” P10 illustrated this challenge vividly:

‘Well I think the hardest part of the role was … if we’re in Winnipeg right now, and we got a game tonight, in your mind, … I didn’t even have to try, like my mind already went through their line-up and I knew which guys maybe and which guys would … and then my, I would fight the guy probably a 1000 times before the game … in my mind and not even try, just on its own would do that. … I guess or I handled it better but some of the guys that really had issues with drugs and alcohol, I think that was a huge part of it. It was the stress. So you go and you play, even if you didn’t fight tonight … whether we played tomorrow night in Toronto or we don’t play at all until Saturday, now your mind’s already gone to that game. Now you’re already fighting that guy. And if there’s three days before the game you’re going to fight him every day, almost every waking moment, it’s going to roll in your mind. And back then, there’s two or three guys on the team. There’s two or three guys, you’re thinking of every guy … ’

P6 echoed some of these points and described it this way:

‘ … I was an under-sized guy I mean going up like, alright got the Montreal Canadians tomorrow got to fight NHL enforcer or it’s like oh ya I got you know NHL enforcer Wednesday. It’s like how do you, how do you explain to somebody … the chronic state of anxiety? … the mental part was probably the hardest part. It wasn’t the physical. … I mean, especially when you are going against guys who really wreck your face and your life up. Uh, so, ya I think it’s just the, the negative emotions, then the chronic state of anxiety just took its toll’.

3.2.2. Being embarrassed

Four of 10 participants described another feature related to fighting that caused concern or worry was the risk of being embarrassed by losing a fight in a dramatic way. For example, P2 recalled “Just knowing … any night I could be knocked down—knocked out on my back in front of 1000s of fans always worried me. So that was always in the back of my mind.” P5 added: You know you think about it a lot because you know … nobody wanted to be embarrassed.’ P8 described the reciprocity involved in this process: “the way that I thought was you never wanted to be embarrassed … um I think in all my fights I never tried embarrassing somebody after a fight” (P8).

3.2.3. Significant injury

It is understandable that the role of enforcer would generate concerns over physical safety and serious injury. This was noted by five of 10 participants. The concerns were expressed by those who embraced the role with general examples such as “Obviously, (clears throat) the prospect of injury. At the time, you don’t really think about it too too much” (P1). For those that tolerated the role, the examples were more vivid and personal. P2 described it this way: “And some of these guys are, you know, my neck’s the size of their arms. … and they’re really big, really strong. And, so that was a tough couple of years there” (P2). Losing a fight often meant consequences beyond injury: “if you lose your fight, obviously, that sucks, physically it hurts … it sucks more because if you thought you lost you had to go out and fight him again” (P10). The second fight would usually occur during the same game even though there could have been significant injury sustained during the first fight. P9 shared a detailed example of concerns regarding fighting when over-matched:

‘I remember being in a warm-up in NHL City and NHL Player who I played with on the NHL Team … we were in warm-up and NHL Player knew I’d fight everybody. … and he’s now with the NHL Team, he’s like P9, he’s like don’t fight this guy, he’ll, he doesn’t like you, he’s coming after you tonight, he goes, just stay away, don’t drop them (his gloves), he wants … he says guys fight to fight, he fights to kill, to hurt … so ya don’t fight him. Ya so I didn’t fight him (laughs)’.

3.2.4. Performance and expendability

Most participants expressed that their success as an enforcer was necessary for them to remain employed in professional ice hockey. In other words, it was very rare for an enforcer to transition into a non-enforcer role due to being labelled as an enforcer as well as the difficult task of improving skills while focused on fighting with limited playing time during games. Nine of 10 participants expressed concerns over how losing a fight could immediately impact their careers. The impact could mean losing a place on the team: “you are essentially a number. There’s always going to be somebody willing … to come and fight, take your job right?” (P1). P3 added:

‘You’re not afraid of getting beat … I’m in fear of losing because out of losing you lose your reputation, you lose your status on your team … but if you win almost all of them, a good 85% of them, you know, you’ve got that status behind you’ (P3).

This issue was discussed by P10: “if you kind of get into a dip where you’re losing fights, you might lose your job, and back then, you know … it was a one-year deal, once and a while you get a two-year deal … So you’re basically fighting for your job every night.” Maintaining a position on the team often meant playing and fighting when injured. Three participants described playing through concussions due to concerns about losing their job (previously described in Gaetz, Citation2021). For example, “not saying anything (about being concussed) because I was starting to play … and wanting to stay in the line-up” (P2) or “ … if I had a concussion and was going to miss whatever like … I might lose my job and I might end up getting sent to the minors’ (P4). Finally, P10 concisely described the concern: “‘You know what, you got a concussion? You can’t play? That’s fine. I got someone in the minors that can. And that’s basically what it was. You’re going to lose your job’” (P10).

3.2.5. Parental acceptance

High parental involvement is typically necessary for an aspiring athlete to reach the elite levels within the sport. Parents are often involved in coaching and managing teams and many hours and dollars are invested in equipment, travel, and training. As such, parents are typically very invested in the success of their child within the sport. This dynamic can often lead to conversations about achievement and expectations. For example, three participants recalled conversations they had with their fathers during their career regarding their role as enforcer. P3 recalled this conversation:

‘“Son why you doing that … you don’t have to fight, you’re a good enough player?” I’d just say Dad, you know, it is the way it is and it’s the way I need to get my opportunity … he, you know, was more of a guy that wanted to see you play the game … ’

The conversation between P7 and his father was described this way:

‘I know that used to bother my father. Like saying “Why are you doing that?” Because he could tell, he knew the game. You didn’t show up on the ice for twelve minutes and you do show up and your gloves are off two seconds after your shift starts. He goes “What’s that all about?” He despised that’.

One of the conversations revealed a clear depiction of what the future would hold. After telling his father about a successful fight, P10ʹs father said: ‘“Well do you think that’s a good thing?” And I said well why would it be a bad thing … ? He goes, “they’re going to expect you to do it again”’ (P10).

In a reversal of roles, P9 described how he felt when his son was ready to leave for his first junior hockey camp: ‘Seven years ago was the first time I had an anxiety attack. … my son was going to his first junior hockey camp. So my wife went, I said like “I don’t want him to get hurt … I don’t think you should go”. So I kept calling like every … hour on the hour to my wife when he was on the ice, like “Is he OK?” … because I know he’s never been in a fight’.

3.3 “PTSD”

Participants were asked about disturbing memories and images related to their role as enforcer. To be clear, no participant was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) however some described memories of events that continue to trouble them. Four of 10 participants described a fighting-related memory or trigger that disturbed them. One mentioned a “PTSD-like” state:

‘But like even during pre-game nap the day of (the game) it would never leave my mind, so I don’t miss that. I can assure you that. There’s some sort of PTSD from it honestly. … I mean the only thing that kind of triggers it is like sometimes I hear the national anthem and I kind of just have like flashbacks of standing there knowing I’m fighting, like that, that feeling? … I’ve been knocked, dropped and knocked out before. Those memories don’t bother me so much … ’ (P6).

Another remembers the difficulty of seeing a team mate badly injured in a fight and the consequences he faced afterwards.

P9: ‘I remember actually NHL team mate … we were in NHL City and he fought NHL enforcer … and NHL enforcer absolutely kicked the living crap out of him. … and NHL team mate was never the same after that. He was never ever the same.

Interviewer: Like as a player, or as a like …

P9: Both. Player, tough guy, enforcer, he, you know NHL enforcer basically shattered his orbital and he … never, never came back from that. … his kids didn’t recognize him … … they were scared of him.’ (P9).

One of the realities of being a professional ice hockey enforcer is that at some point, you may have to fight someone who was previously a team mate, or even someone you consider a friend. P10 described the difficult situation of being confronted with this dilemma. When asked about difficult images or memories related to fighting, he stated: “in terms of the fights, no like I never, they were what they were”. However, he then went on to describe a difficult event that brought up emotion:

‘NHL Coach sent him (his friend) out and I’m like are you fucking kidding? … we were fucking team mates for like two years, he took care of my kids-like, so it was easily the hardest fight I ever had.’

He continued: ‘The fight’s over, you know, we both get in our punches taken, whatever. After the game … I went out, (to) look for him, and I see him. As I’m going over to see him, he’s standing with his kid son’s name. Son’s name couldn’t have been more than five years old. And the closer I got, he’s fucking bawling. And I can feel myself just fucking getting smaller and smaller. He’s like, “you guys are supposed to be friends, you tried to hurt dad!” and like oh my god. That was, that was the hardest one … (sighs). I mean it was, like fuck does that suck.’

3.3. Depression

3.3.1. Diagnosed depression

Participants were asked to share whether they experienced any periods where they felt sad or down for prolonged periods of time, or whether they have been diagnosed with depression. Eight of 10 participants reported that they currently have no concerns with feeling sad or down, that they had few if any problems in the past, and that they are functioning well in the jobs and lives generally. Examples of responses included: “I would say, uh, definitely not” (P3) or ‘Maybe I guess everybody has a bad day so that kind of thing? But nothing that was prolonged” (P5). However, two of 10 participants reported having depression diagnosed by a physician. One participant reported that his depression had occurred in the past two years following retirement from hockey. In his opinion, his depression was related to his transition out of professional hockey. Another participant reported that he had depression and a family history of the disorder.

‘Oh ya, for sure. I’m dealing with depression now. I’m on medication for depression. Um, the sadness of, ya I’m, I’m dealing with it all of the time. So I wake up sad a lot of times. … my parents, you know what? My parents both have depression’ (P9).

Unfortunately, his depression led to at least one suicide attempt. He describes his depression now as:

“am I happy where I’m at today? Well I’m happy that I’m still alive. Um, do I still have suicidal thoughts? I don’t think I have those like I used to … but some days I do get fed up and I just sit there … I told my wife that, I said you know like, some days, if it wasn’t for my kids … (P9).

3.3.2. Undiagnosed periods of sadness

One participant described a disruption in his hockey career and periods following his career where he had difficulty functioning or had periods of sadness. During his career, he described “My heart just wasn’t there, to play hockey” (P8) at the beginning of training camp. At that point, he decided to take some time away from hockey and returned to the team one to two months later. When asked about depression, he stated “Do I have any depression, I don’t get into any deep depression, I don’t believe … deep depression or suicidal or anything like that no.” (P8). This participant did not feel that these challenges warranted a visit to a physician and feels that he is able to manage these moments on his own.

3.3.3. Periods of depression/emotional distress related to career transition

Five of the 8 participants not diagnosed with depression described periods of feeling down, sad, or anxious related to transition out of professional ice hockey. For some, this was relatively short-lived and did not cause significant disruptions in functioning. When asked about depression or periods of being down, P3 replied: “You know, I would say I probably questioned, um, what I’m doing (post-hockey). And, I didn’t like it, but I was in fear of failure so I just did it.” P4 described it this way: “I don’t think I have and uh, I mean, I’ve had you know a little bit of anxiety now and again … that had to do with sort of career change things and you know which brings it on a little bit. Thinking of doing something obviously, you know, something new.” The experience described by P6 was similar:

‘Never been diagnosed with depression, it was about my last year when I kind of seen the writing on the wall … the direction it was headed and, me hanging on, so I don’t know, I wouldn’t call it depression, it was more like um, I guess you could say there was emotions of that but it wasn’t like, uh, you know it wasn’t like sitting there all day like worrying about it but I was, you know, trying to figure out my game plan.’

Some experienced almost no issues with the transition because of other equally viable options. For example:

‘ … there was always something ahead of me. If I was unemployed after hockey and was sitting around, or uh you know feeling sorry for myself, I think there could have been a chance after? But I never had a chance to dwell on anything like that. I went right from playing hockey to wondering what am I going to do? Am I going back to university? What am I going to do here? I don’t want to waste my god given intelligence by just, you know, feeling sorry for myself or whatever.’

The experienced described by P10 clearly illustrates how the transition out of hockey affected emotional well-being. When asked about depression he stated:

‘Oh ya, without question. You see, so when I finished, you know part of the problem is that, you don’t know what to do next. … so you’re sitting, OK now what? … for a lot of guys I could, I really don’t know that it’s concussion related. I think a lot of it’s what you’re talking about the depression part it’s “OK now what?” All those guys had money, it wasn’t like it was a money thing, like they’re desperate, they need a job, whatever. It was like, I don’t know what to do? I don’t know where to go? (P10).

The two participants diagnosed with depression also described how the transition out of hockey impacted their mental well-being. For P1, career transition was a factor in the onset of his depression. He stated: “ … I was in that, kind of just trying to find myself and then … depressed really.” For P9, although his depression was longer standing and more severe, he described how the void he experienced post-retirement was at times difficult:

‘Like, I’m coaching my kid, I’m having fun doing that but … for me, I had no self-esteem, you know like there was no, I had no direction, I was just drinking coffee every day and, you know going to cut grass for a friend of mine, kind of just to keep myself busy, but I had no, you know I went to work with the WHL team a little bit, but I didn’t, I didn’t really latch onto anything because, I think I, I was so unhappy with myself, of where I had put myself … everybody thought I was happy P9 you know what I mean? Meanwhile inside I’m just, or when I’m alone, I’m just eating myself up.’

4. Discussion

It has been suggested that retired hockey enforcers are at greater risk of mental health problems and suicide (Fitz-Gerald, Citation2015; Larsen, Citation2017; Strong, Citation2019). Elevated levels of mental health problems have been found in retired athletes (Gouttebarge et al., Citation2016a, Citation2015, Citation2016b) and this has been linked to concussion history in some studies (e.g., Guskiewicz et al., Citation2007; Kerr et al., Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2020). Athletes with concussion histories have also been considered to have a higher risk of suicide following retirement (e.g., Azad et al., Citation2016; Baum, Citation2005; Bennet et al., Citation2011; Omalu et al., Citation2010). Based on these data, it was hypothesised that ex-professional ice hockey enforcers would have challenges with mental health caused by exposure to repetitive exposure to concussive and sub-concussive events consistent with CTE symptomology.

The results of this study do not support the hypothesis. In the current study, two of 10 participants stated that they had been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives and one participant described periods of sadness that may or may not be related to depression. Of those with diagnosed depression, one described a past suicide attempt. As such, those with diagnosed depression constituted 20% of the sample and the lifetime prevalence of depression can be estimated at between 20–30%. As a comparison, the estimated lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in elite athletes has been estimated to be at or above 50% (Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020; Foskett & Longstaff, Citation2018; Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Reardon et al., Citation2019). In former elite athletes, incidence rates for mental health disorders may range from 5–30% over a 12-month follow-up (Reardon et al., Citation2019). The lifetime prevalence of depression in U.S. males has been estimated at between 21.9–28.1% (González et al., Citation2010) and that estimate could be higher for those employed in male dominated male-dominated professions (Roche et al., Citation2016). Therefore, when all factors are considered, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in elite athletes including those in this study, may be slightly elevated but mirrors rates in the general population (Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020; Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Reardon et al., Citation2019). In addition, consistent with Åkesdotter et al. (Citation2020), the participants described in this study are working and have reasonably good post-career functioning (Gaetz, Citation2021) therefore it was unlikely that they were experiencing significant mental health problems at the time of interview.

Therefore, how can we begin to resolve the discrepancy between the reports of neurotrauma leading to depression and untimely death in ex-professional hockey enforcers with the lived experience of the participants in this sample? One element to consider is the link between concussion and depression. For example, Vargas et al (2015) have shown that as high as 20% of collegiate athletes may develop depression following sports-related concussion. However, what is rarely discussed is that any injury can cause the onset of depression in athletes (Appaneal et al., Citation2009; Brewer and Petrie Citation1995; Hutchison et al., Citation2009; Leddy et al., Citation1994). In their review and recommendations, Reardon et al. (Citation2019) discussed that injured athletes report more symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder and depression when compared with non-injured athletes. Further, that emotional responses to injury may include but are not limited to anxiety, sadness, depression, and suicidal ideation. Mainwaring et al. (Citation2010) addressed this issue specifically by comparing emotional responses in athletes with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury versus those who had a concussion. Their results indicated that athletes with ACL injuries had depression that was more severe and of longer duration compared to athletes with concussion. Lastly, a recent systematic review by Sabol et al. (Citation2021) found similar patterns of depression and anxiety symptoms following musculoskeletal injury and concussion. As such, a concussion may cause depression in some athletes for no other reason than that the fact that it is an injury that can limit or end a career (e.g., Caron et al., Citation2013) independent of any neural dysregulation that can occur.

Another element to consider is the speculative link between concussions, CTE and depression (Larsen, Citation2017; Strong, Citation2019). A recent study by Bieniek et al. (Citation2019) may be of benefit in this discussion. Of a sample of 300 cases who had a history of participation in contact sport, 4% of that sample was positive for CTE while an additional 5% had some of the features of CTE but did not meet all criteria. Of the 450 control participants that had no history of sport participation, 2% were positive for CTE with 1.3% of this sample showing some of the CTE features. To put these data into perspective: 1) a diagnosis of CTE occurred in relatively few participants who had a history of participation in contact sport (1 in 25 people), and 2) there were participants who were CTE positive but had no known history of contact sport participation. This finding was also reported by Iverson et al. (Citation2019) who provided detailed CTE positive cases with no history of repetitive neurotrauma. Another interesting result from the Bieniek et al. (Citation2019) study was that the entire sample of those with a history of contact sport had lower levels of depression, suicide, anxiety, and alcoholism compared to the sample with no history of sport activity. Finally, a recent study describing the criteria for Traumatic Encephalography Syndrome (TES) proposed by Montenigro et al. (Citation2014) found that the only significant predictor for TES in a sample of retired National Football League (NFL) athletes was depression, not the number of games played in the NFL, number of concussions, the number of concussions with loss of consciousness, or years playing professionally (Jeff et al., Citation2021). Therefore, more recent evidence indicates that CTE may not be as prevalent as once thought and may not be related to neurotrauma alone.

Importantly, it must be acknowledged that the participant in this study with the most severe depression did attempt suicide. We will never know what role his concussion history alone played in this decision. What we do know based on scientific evidence is that many other important factors could have independently led to the suicide attempt. The participant likely had a genetic predisposition to depression with both parents having problems with depression and substance abuse. This participant also had a history of alcohol use/abuse during his career with other substances being abused in the last year of his career and into retirement. In addition, the participant reported a difficult transition from hockey and had a history of multiple physical injuries and corrective surgeries (Gaetz, Citation2021) that has left him with chronic pain. In other words, he lives with all of the elements of the AP-CA model (Gaetz, Citation2017), any of which could account for negative affect and suicide alone.

This study is the first to describe the types of emotional stresses that are unique to professional ice hockey enforcers. The lived experiences of participants indicated that their role could result in elevated anxiety states mediated by differences in how the role was perceived. Those who embraced the role seemed to be less bothered by certain aspects of the role of enforcer while on the other hand, those that tolerated or accepted the role as necessary for their continued employment reported more substantial concerns that affected them more often. Concerns included preparation to fight, being embarrassed or sustaining a significant injury, how losing fights could impact their employment status, and how their family members may have not agreed with their role. A smaller number of participants described “PTSD-like” memories and triggers for events related to the role of enforcer. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the role of enforcer exposed the participants to situations and stressors that other players would not experience. This may lead to prolonged stress-states and may in part account for the negative outcomes that some ex-professional hockey enforcers experienced post-career.

Unfortunately, elevated stress loads and challenges to mental health may lead to issues with substance use and abuse (Pichler & Christian Claussen, Citation2020). Of note, the two participants in this study with diagnosed depression also had a positive history for drug and alcohol misuse/abuse (substance use/abuse will be the focus of a future manuscript). Further, autobiographies and biographies of ex-professional hockey enforcers such as Bob Probert (Probert & McLellan-Day, Citation2010), Chris Nilan (Nilan, Citation2013) and Derek Boogaard (Branch, Citation2014) are replete with examples of significant substance abuse that occurred during their careers and/or into retirement. It is also important to recognize the link between career transition stress and mental health (Barcza-Renner et al Citation2020). In the current study, participants explained how the transition out of hockey left them feeling emotional, sad, or down for varying lengths of time. It is well-known that athletes are vulnerable to challenges with mental health when transitioning out of their sport and this can also co-occur with substance abuse (e.g., Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020; Pichler & Christian Claussen, Citation2020; Reardon et al., Citation2019; Sarah et al., Citation2017; Wolanin et al., Citation2015). Issues with career transition stress and athletic identity in this sample will be fully discussed in a future manuscript.

This study had a number of limitations. The interview content was based on the retrospective recall of participants and therefore may have inaccuracies due to the passage of time. The subject material was focused on mental health status. Some participants may not have felt comfortable revealing personal experiences with depression or anxiety due to the stigma associated with mental illness. In addition, some participants may have limited the frankness of their responses because they continue to work in a hockey-related field and were concerned about how participation might affect employment. This was addressed by removing personally identifying information and allowing participants to edit their transcript for content.

In summary, there has been much speculation about the post-career functioning of ex-professional ice hockey enforcers. Providing a voice for those who had this role is important because their lived experiences are crucial for an understanding about why negative outcomes occurred in the past. Are we any closer to answering the question as to what caused three athletes who had the same role in the sport to die in similar ways at approximately the same time? When combined with the content of the study by Gaetz (Citation2021), the answer may be a qualified “yes”. It has been revealed that this sample of ex-professional ice hockey enforcers experienced a significant number of concussions, have some challenges with chronic pain (Gaetz, Citation2021), and were exposed to several unique stressors, the effects of which may vary dependent upon how the role was viewed. It may be the case that for some enforcers who tolerated the role, negative aspects of the role may cause a stress mediated challenge with mental health which may be exacerbated during transition out of the sport. However, it important to note that the sample described in this study is functioning relatively well with all employed in demanding professions at the time of interview. Therefore, it can be concluded that a negative outcome is not inevitable following a career as an ice hockey enforcer.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge the participants in this study for their time, willingness to be candid in their comments, and their motivation to improve the sport of hockey for future participants.

Declaration of interest: There was no financial interest or benefit associated with this research or the production of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author [MG]. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Misuse (intentional or unintentional) could compromise confidentiality and may negatively impact employment of the participants within their profession.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Gaetz

Michael Gaetz have been actively engaged in research on concussion in sport for over 20 years. More recently, I have published theoretical work to explain the experiences of athletes following retirement from contact sport. This work is ongoing and will add to the literature on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). My other current research interests are in how activity may affect quality of life in the elderly and the effects of weight cutting in combat sport. My clinical background is as a neurophysiologist working in the operating room using electrophysiologic procedures to monitor brain and spinal cord functioning during high-risk surgeries.

Notes

1. In hockey, a major penalty is given for more serious infractions. It differs from a minor penalty in that it is longer (five or 10 minutes instead of two) and that the player must remain in the penalty box for the entire duration of the penalty whereas minor penalties end after two minutes or when a goal is scored while the player is serving the penalty.

References

- Åkesdotter, C., Kenttä, G., Eloranta, S., & Franck, J. (2020). The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 329–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.022

- Anamika, D., Singh, G., & Gupta, A. K. (2018). Women and Climate Stress: Role Reversal from Beneficiaries to Expert. World Development, 103, 336–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.026

- Appaneal, R. N., Perna, F. M., & Larkin, K. T. (2009). Measuring post injury depression among male and female competitive athletes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(1), 60–76.13. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.1.60

- Armstrong, R. A., Ann, C. M., Stein, T. D., Alvarez, V. E., & Cairns, N. J. (2016, March 21). A quantitative study of tau pathology in 11 cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, 43(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12323

- Arthur, B. (2011, August 31). Belak death an end to a wretched summer. National Post.

- Azad, T. D., Amy, L., Pendharkar, A. V., Veeravagu, A., & Grant, G. A. (2016). Junior Seau: An illustrative case of Chronic traumatic encephalopathy and update on chronic sports-related head injury. World Neurosurgery Feb, 86, 515.e11–515.e16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.032

- Bailes, J. E., Turner, R. C., Lucke-Wold, B. P., Patel, V., & Lee, J. M. (2015). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Is it real? The relationship between neurotrauma and neurodegeneration. Neurosurgery, 62(Suppl 1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000811

- Barcza-Renner, K., Shipherd, A. M., & Basevitch, I. (2020). A Qualitative Examination of Sport Retirement in Former NCAA Division I Athletes. Journal of Athlete Development and Experience, Vol. 2(1), pp. 1–14. Bowling Green State University https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/jade/

- Baum, A. L. (2005). Suicide in athletes: A review and commentary. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 24(4), 853–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2005.06.006

- Bell, E., Kothiyal, N., & Willmott, H. (2017). Methodology‐as‐technique and the meaning of rigour in globalized management research. British Journal of Management, 28(3), 534–550.

- Bennet, O., Bailes, J., Ronald, L. H., Ilyas Kamboh, M., Hammers, J., Case, M., & Fitzsimmons, R. (2011). Emerging histomorphologic phenotypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American athletes. Neurosurgery, 69(1), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e318212bc7b

- Bieniek, K. F., Blessing, M. M., Heckman, M. G., Diehl, N. N., Serie I, A. M., Michael, A., Paolini, I. I., Bradley F, B. et al. (2019). Association between contact sports participation and chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A retrospective cohort study. Brain Pathology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12757

- Bird David, N. (1999). ‘Animism’ revisited: Personhood, Environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40(2), S67–S79. https://doi.org/10.1086/200061

- Bornheimer, L. A., & Gangwisch, J. E. (2009). Sports participation as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents as mediated by self-esteem and social support. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(5), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b33659

- Botha, L. (2011). Mixing methods as a process towards indigenous methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(4), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2010.516644

- Branch, J. (2014). Boy on ice: The life and death of derek boogaard. Harper Collins Publishers.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise 191-205. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762012

- Brewer, B.W., & Trent, A. Petrie. (1995). A comparison of injured and uninjured football players on selected psychosocial variables. Academic Athletic Journal. Spring 11-18.

- Brosse, A. L., Sheets, E. S., Lett, H. S., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2002). Exercise and the treatment of clinical depression in adults: Recent findings and future directions. Sports Medicine, 32(12), 741–760. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200232120-00001

- Brownlee, J., & Berthelsen, D. (2008). Developing Relational Epistemology Through Relational Pedagogy: New Ways of Thinking About Personal Epistemology in Teacher Education. In M. S. Khine (Ed.), Knowing, Knowledge and Beliefs Epistemological Studies across Diverse Cultures. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6596-5_19

- Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done?. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058877

- Bryman, A. (2007). Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906290531

- Caron, J. G., Bloom, G. A., Johnston, K. M., & Sabiston, C. M. (2013). Effects of multiple concussions on retired national hockey league players. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.35.2.168

- Castellani, R. J. (2015). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A paradigm in search of evidence? Laboratory Investigation, 95(6), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2015.54

- Causadias, J. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Overton, W. F. (2018). Moral Meta-Narratives, Marginalization, and Youth Development. The American Psychologist, 73(6), 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000252

- Chilisa, B., & Tsheko, G. N. (2014). Mixed Methods in Indigenous Research: Building Relationships for Sustainable Intervention Outcomes. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 8(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814527878

- Cochrane, P. A. L. C. A. M., Garcia-Downing, C., Kendall, E., Cook, D., McCubbin, L., & Gover, R. M. S. (2008). Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Implications for Participatory Research and Community. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 22–27.

- Creswell, J. W. 2015. Revisiting Mixed Methods and Advancing Scientific Practices. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry Oxford University Press Incorporated. ProQuest Ebook Central (pp. 57–71). http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ufvca/detail.action?docID=2044599

- Creswell, J. W., & Piano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Usage.

- d´Ishtar, Z. 2005. Striving for a common language: A white feminist parallel to Indigenous ways of knowing and researching. Women’s Studies International Forum 28(5): 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2005.05.006

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). Introduction: Critical methodologies andIndigenous inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and Indigenous methodologies (pp. 1–20). Sage: Thousand Oaks. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686.n1

- Elliot-Groves, E. (2019). A culturally grounded biopsychosocial assessment utilizing Indigenous ways of knowing with the Cowichan Tribes. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 28, 1 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2019.1570889

- Feilzer, M. Y. (2010). Doing Mixed Methods Research Pragmatically: Implications for the Rediscovery of Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809349691

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fitz-Gerald, S. (2015, September 22). List of enforcers who have passed away gets longer. The Star.

- Foskett, R. L., & Longstaff, F. (2018). The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science in Sport and Medicine, 21(8), 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.11.016

- Gaetz, M. (2017). The multi-factorial origins of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) symptomology in post-career athletes: The athlete post-career adjustment (AP-CA) model. Medical Hypothesis, 102C, 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2017.03.023

- Gaetz, M. (2021). Understanding post-career adjustment in ex-professional hockey enforcers: Concussion history and chronic pain. Cogent Medicine, 8(1), 1 1876321. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2021.1876321

- González, H. M., Tarraf, W., Whitfield, K. E., & Vega, W. A. (2010). The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 44(15), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017

- Gouttebarge, V., Aoki, H., & Kerkhoffs, G. (2016a). Prevalence and determinants of symptoms related to mental disorders in retired male professional footballers. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 56, 648–654.

- Gouttebarge, V., Frings-Dresen, M. H. W., & Sluiter, J. K. (2015). Mental and psychosocial health among current and former professional footballers. Occupational Medicine, 65(3), 190–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu202

- Gouttebarge, V., Jonkers, R., Moen, M., Verhagen, E., Wylleman, P., & Kerkhoffs, G. (2017). The prevalence and risk indicators of symptoms of common mental disorders among current and former dutch elite athletes. Journal of Sports Science, 35(21), 2148–2156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1258485

- Gouttebarge, V., Kerkhoffs, G., & Lambert, M. (2016b). Prevalence and determinants of symptoms of common mental disorders in retired professional rugby Union players. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(5), 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2015.1086819

- Gray, V., Rabinowitz, A., Meyer, J., & Arnett, P. A. (2015). Predictors and prevalence of postconcussion depression symptoms in collegiate athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-50.3.02

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., Mackinnon, A., Batterham, P. J., & Stanimirovic, R. (2015). The mental health of Australian elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 255–261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.006

- Guskiewicz, K. M., Marshall, S. W., Baile, J., McCrae, M., Harding, H. P., Matthews, A., Register Mikhalik, J. et al (2007). Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise, 39(6), 903–909. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180383da5

- Hall, J. N. (2013). Pragmatism, evidence, and mixed methods evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 138, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20054

- Held, M. B. (2019). Decolonizing Research Paradigms in the Context of Settler Colonialism: An Unsettling, Mutual, and Collaborative Effort. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918821574

- Hesse-Biber, S. (2010). Qualitative Approaches to Mixed Methods Practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364611

- Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Johnson, R. B. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford University Press.

- Huber, B. R., Alosco, M. L., Stein, T. D., & McKee, A. C. (2016). Potential long-term consequences of concussive and subconcussive injury. Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 27, 503–511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2015.12.007

- Hutchison, M., Mainwaring, L., Comper, P., Richards, D., & Bisschop, S. (2009). Differential emotional responses of varsity athletes to concussion and musculoskeletal injuries. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 19(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e318190ba06

- Ingram, D., Wilbur, J., McDevitt, J., & Buchholz, S. (2011). Women’s Walking Program for African American women: Expectations and recommendations from participants as experts. Women & Health, 51(6), 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.606357

- Iverson, G. L., Gardner, A. J., McCrory, P., Zafonte, R., & Castellani, R. J. (2015). A critical review of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Review, 56, 276–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.008

- Iverson, G. L., Luoto, T. M., Karhunen, P. J., & Castellani, R. J. (2019). Mild chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathology in people with no known participation in contact sports or history of repetitive neurotrauma. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 78(7), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlz045

- Jeff, S., Didehbani, N., LoBue, C., Hart, J., Rossetti, H., Lacritz, L., & Munro Cullum, C. (2021). Frequency and predictors of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome in a prospective cohort of retired professional athletes. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 1–13 (617526. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.617526

- Jensen, N., Stine, A. I., Fallby, J., Dankers, S., & Elbe, A.-M. (2018). Depression in Danish and Swedish elite football players and its relation to perfectionism and anxiety. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.02.008

- Johnson, R. B., de Waal, C., Stefurak, T., & David, L. H. (2017). Understanding the philosophical positions of classical and neopragmatists for mixed methods research. Köln Z Soziol, 69(2), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-017-0452-3

- Kawagley, A. O. 1993. A Yupiaq world view: Implications for cultural, educational, and technological adaptation in a contemporary world. University of British Columbia.

- Kerr, Z. Y., Thomas, L. C., Simon, J. E., McCrea, M., & Guskiewicz, K. M. (2018). Association between history of multiple concussions and health outcomes among former college football players: 15-year follow-up from the NCAA concussion study (1999-2001). American Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(7), 1733–1741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518765121

- Kovach, K. M., Capadona, J. R., Gupta, A. S., & Potkay, J. A. (2014). The effects of PEG‐based surface modification of PDMS microchannels on long‐term hemocompatibility. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part A, 102(12), 4195–4205.

- Larkin, M., Watts, S., & Clifton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in interpretive phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp062oa

- Larsen, K. (2017 Jan 12, 2017). Repeated concussions suffered by the star cowboy may have led to permanent brain changes, says expert. CBC News. Posted, 12. 42 PM PT.

- Leddy, M. H., Lambert, M. J., & Ogles, B. M. (1994). Psychological consequences of athletic injury among high-level competitors. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65(4), 347Y54. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1994.10607639

- Mainwaring, L. M., Hutchison, M., Bisschop, S. M., Comper, P., & Richards, D. W. (2010). Emotional response to sport concussion compared to ACL injury. Brain Injury, 24(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699051003610508

- Margaret, K., Carrier, J., Harpell Montgomery, M. J. B., & Gilles, C. 2014. Indigenous Presence: Experiencing and envisioning indigenous knowledges within selected post-secondary sites of education and social work. http://www.usask.ca/education/profiles/kovach/index.php

- Marin, A., Medin, D., & Ojalehto, B. (2017). Conceptual change, relationships, and cultural epistemologies. In T. G. Amin & O. Levrini (Eds.), Converging perspectives on perceptual change. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315467139-7

- Martin Debbie, H. (2012). Two-eyed seeing: A framework for understanding indigenous and non-indigenous approaches to indigenous health research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(2), 20–42.

- McGloin, S. (2015). The ins and outs of fluid balance in the acutely ill patient. The British Journal of Nursing, 24(1), 14–18.

- McKee, A. C., Abdolmohammadi, B., & Stein, T. D. (2018). The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 158, 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63954-7.00028-8

- Michael, F., Thiruchelvam, D., Tien, H. C., & Redelmeier, D. A. (2016). Risk of suicide after a concussion. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 18(7), 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150790

- Miller, J. J., & Wendt, J. T. (2015). The concussion crisis in the national hockey league. Journal of Contemporary Athletics, 9(1), 1–16. http://ir.stthomas.edu/ocbeblpub/52