?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Late presentation in glaucoma has been associated with rapid deterioration of visual fields and blindness even with good and effective treatment options. Glaucoma prevalence and risk of blindness is higher among the Igbo tribe, who dominate the Eastern part of Nigeria, hence the focus of this study in this area to determine modifiable risks for late presentation in glaucoma. This was an observational, hospital-based, comparative study at three tertiary hospitals. All eligible, consenting participants were examined and researcher-recorded questionnaire administered. Data was entered, validated and imported into Stata version 15.0; appropriate descriptive measures of central tendencies were presented with tables and maps. Univariate, multiple logistic regression and pairwise correlation analysis identified statistically significant risks at p-value of <0.05. 303 participants were enrolled with a mean (SD) age of 56.58 (15.63) years. The adjusted odds of presenting late were found to be 57% lower among females (CI 0.27 to 0.69), 1.73 times higher with each year increase (CI 1.42 to 2.11) and 2.31 times among hypertensives (CI 1.39 to 3.85). There were reduced adjusted odds ratio; 0.55 for participants living in urban areas compared to rural (p 0.02) and 0.52 for those who have heard about glaucoma prior to diagnosis (p 0.01). Increasing age, male sex, rural and non-awareness of glaucoma are identified risk for late presentation. Community-based health promotion activities can be explored to bridge this gap through targeted and cost-effective approaches involving existing health-care delivery systems.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide; it occurs more, runs an aggressive course and difficult to treat among blacks. Glaucoma is undiagnosed in as high as 94% of cases in low-resource settings such as Africa. Unfortunately, screening activities are not recommended at a population level because of lack of a single screening or cost-effective treatment modality. Late presentation is a recurring feature in glaucoma as it presents little or no symptoms in the early stage and is referred to as “a silent thief of sight”. The impact of presenting late in glaucoma leads to poorer outcome even with the most effective treatment, therefore it seems profitable to present early. Improved technology in diagnosis and glaucoma surveillance favors early presentation in the west, whereas in developing countries, unfavourable factors include poor access to services, lack of awareness, low level of education and poor health seeking behaviour. Individuals above 50 years, male, rural dwellers as well as hypertensives will benefit from regular eye check for glaucoma.

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness and leads to 8% of all causes of blindness worldwide (Pascolini & Mariotti, Citation2012). By 2040, it is estimated that the number of people diagnosed with glaucoma will double to 120 million due to increasing world population growth and aging; Tham et al., Citation2014. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) constitutes over 90% of all glaucoma cases worldwide especially among Africans (Tham et al. (Citation2014), Kyari et al. (Citation2015), Budenz et al. (Citation2013)). In addition, POAG is more prevalent among blacks, runs a more aggressive course and is inadequately managed compared to Caucasians and the West. The risk of blindness from glaucoma is associated with the stage and severity of the disease at diagnosis, age at onset, family history of glaucoma, compliance with treatment-associated co-morbidities and higher IOP at presentation (Kyari et al. (Citation2013), Quigley and Broman (Citation2006)). High intraocular pressure (IOP) is a modifiable risk factor for glaucoma progression with reduced progression of the disease when adequately controlled Coleman and Miglior (Citation2008). Other risk factors such as central corneal thickness (CCT), structure of the optic nerve, age, genetic factors, race and refractive error status are non-modifiable ICO Guidelines for Glaucoma Eye Care (Citation2016). In developed countries, increased access to improved technology in case finding, treatment and monitoring has greatly reduced progression to blindness from glaucomaICO. ICO Guidelines for Glaucoma Eye Care (Citation2016). In Nigeria, poor access, poor quality of care and inadequate compliance to treatment and follow up as well as poor health seeking behaviour have been identified as positive risk factors for blindness in glaucoma (Isawumi et al. (Citation2014), Abdull et al. (Citation2016), Kyari et al. (Citation2018)). Over 90% of Igbos, one of the three major ethnic groups in Nigeria reside in the South Eastern part of the country. This tribe has been identified by the Nigerian national and visual impairment survey (NNVIBS) to have the highest prevalence of POAG as well as twice the likelihood of blindness from glaucoma when compared to other tribes in Nigeria (Kyari et al. (Citation2016), Kyari et al. (Citation2016)). There are no standard guidelines for glaucoma case detection and management in Nigeria, and clinicians depend on random recurrent opportunistic screening and treatment. In addition, patients pay out of pocket for health care services. The resultant effect is a poorly coordinated treatment, management and follow-up among glaucoma patients which can lead to poorer outcome. Several Nigerian studies have shown that the proportion of glaucoma patients who present late account for a third to half of the total patients attending the glaucoma clinic (Awoyesuku and Ejimadu (Citation2012), Enock et al. (Citation2010), Olawoye and Sarimiye (Citation2014), Omoti et al. (Citation2006)) with exponentially increase when visual field assessment values are included in its definition. Previously identified risk factors for late presentation in glaucoma range from occupational status, increasing IOP, being referred by a non-optometrist, reduced frequency of eye checks and type of glaucoma (Motlagh and Pirbazari (Citation2016), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Fraser et al. (Citation2001)) to tribe, male sex and single status among others (Kyari et al. (Citation2016)). Late presentation has been associated with rapid deterioration of visual fields even with good management (Susanna et al. (Citation2015), Heijl et al. (Citation2002)). The purpose of this study is to identify modifiable risk factors that lead to late presentation of glaucoma patients to appropriate treatment facilities in the southeast Nigeria, that may be amenable to cost-effective health service interventions. The results will generate recommendations for improved glaucoma care and possibly contribute evidence that can inform future National Glaucoma Guidelines.

2. Methods

An observational, cross-sectional, hospital-based, unmatched case–control study within 3 tertiary hospitals in South East Nigeria. The three sites had specialist glaucoma clinics and are referral centres for glaucoma management. There are 2 glaucoma clinics a week per centre with an average of 35 new glaucoma patients seen by each unit monthly. Recruitment was done over seven weeks in June and July 2019. The minimum calculated sample size was 146 cases and 146 controls to provide 80% power to detect a two-fold increase in the odds of late presentation in a factor present among 25% of the control group at the 5% level of significance.

Therefore, sample size required;

N = calculated sample size

r: ratio of control to case = 1 for equal number of control and case

p*: average proportion exposed = 0.3 derived from a previous study Awoyesuku and Ejimadu (Citation2012)

Zβ: standard normal variate for power = for 80% power is 0.84

Zα/2: standard normal variate at the 5% (type 1 error) level of significance = 1.96

p1—p2: Effect size = 0.4–0.25 = 0.15 (p1 is the expected proportion when a factor considered is present in 25% of controls given by =

)

Substituting;

= 146.4 in each arm

Ethical approval with adherence to the standard of the Helsinki declaration on the use of human subjects was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the three participating hospitals and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM MSc. Ethics ref—17,219). Written consent was obtained from all the patients recruited and/or witness after reading or having the study information sheet explained to them. Eligible patients were recruited consecutively until the sample size was reached.

The following Inclusion criteria were considered for each participant before enrollment into the study -

Age 18 years and above

A newly diagnosed patient with typical glaucoma as defined below in at least one eye Kyari et al. (Citation2016), Kyari et al. (Citation2015):

Level 1 (structural and functional)—97.5th percentile of the VCDR (≥0.7) or VCDR asymmetry (≥0.1) and visual field loss typical of glaucoma. OR

Level 2 (advanced structural damage only)—99.5th percentile VCDR (≥ 0.75) or VCDR asymmetry (≥0.2) in the absence of visual field evidence. OR

Level 3 (optic disc was not seen, visual field testing was not possible therefore use visual acuity and IOP)—VA <3/60 with the 99.5th percentile IOP (≥ 28 mm Hg) or being diagnosed or treated for glaucoma.

Visual field loss that was consistent with glaucomatous damage, compatible with the patient’s disc changes and in which there is no suggestion of other optic nerve disease example defects that crossed the horizontal midline. OR

A repeatable visual field defect consistent with glaucoma and not explained by other causes OR one visual field test with visual field defect consistent with glaucoma plus corresponding optic disc abnormality.

Primary open angle glaucoma

Participants with less than 20% fixation loss and/or <15% false positives/negatives on visual field testing.

Any patient who did not meet the above criteria was excluded from the study.

After enrollment, the study questionnaire was administered, participant was examined, and findings documented. Subsequently, the principal researcher categorized each participant using the following comparative study case definitions (Motlagh and Pirbazari (Citation2016), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Ntim-Amponsah et al. (Citation2004)) into;

Late presentation

A patient (case) attending the hospital for the first time, who met the inclusion criteria in addition to

Category 1: a definite and reliable glaucomatous visual field defect within the central 10 degrees of fixation or mean deviation ≥ −6.0 in the presence of either CDR 0.7 or a CDR asymmetry 0.2 between adjacent eyes

OR

(ii)Category 2: visual field testing not completed satisfactorily, but has CDR of 0.9, or CDR asymmetry of 0.3 with IOP >28 mmHg

Early presentation

A patient (control) attending the hospital for the first time who met the inclusion criteria in addition to

Category 1: a definite glaucomatous field defect sparing 20 degrees of fixation or mean deviation of ≤-6.0 in the presence of CDR of >0.5 to <0.7 or disc difference of >0.2.

OR

(ii)Category 2: no definite visual field defect with >0.5 to<0.7 CDR or disc difference of >0.3 and IOP <28 mmHg

Patient recruitment was done directly from the glaucoma clinics after diagnosis had been confirmed and the results of relevant investigations recorded in the preliminary section of the proforma. A researcher-administered semi-structured questionnaire was administered to each consenting participant by a senior ophthalmology resident from each centre after basic medical (blood pressure, height and weight) and visual acuity exam were carried out by a senior ophthalmic nurse. The questionnaire contained sub-sections on participant’s bio-data, socio-economic demographics, medical history, ocular history and ophthalmic/medical examination findings. To assess its content, flow and interpretation, the instrument was pre-tested under similar study settings on randomly selected patients (who were not included in the study) before the commencement of the study. Inter-observer agreement was ensured between examining ophthalmologists at the three centers and the principal investigator (PI) with a kappa coefficient of >0.7 during the study training sessions. Finally, each questionnaire was assessed by the PI to categorize each participant according to the study definitions as early or late. This was to reduce observer bias as the interviewers were blind to the study definitions. The pre-coded data was double entered into an excel spread sheet and compared for missing value errors. Any difference between the two files was resolved by referring to the paper forms. Comparative analysis of late versus early presentation was done using Stata/ic 15.0 (Stata corp. college station, Tx). Descriptive analysis of variables was done with appropriate measures of central tendency (mean with standard deviations for approximately normally distributed data and median with interquartile range for non-normally distributed continuous data, respectively). Similarly, percentage, frequencies and proportions were derived for categorical variables. Univariate logistic regression was used to assess the associations between putative risk factors and the odds of being a late presenter. Correlations between putative risk factors were studied to assess confounding using multiple variable regressions. The factors included in the model were determined using step wise regression. In all comparison statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

A total of 303 eligible participants were recruited successfully into the study with a mean (SD) age of 56.58 (15.63) years. One hundred and fifty-seven (51.82%) had the outcome of interest, that is, presented late, 61 (38.85%) of these had very poor visual acuity of less than 3/60 in the better eye and could not perform visual field tests; they were classified as late using the level 3 category described in the methods section. More than half of the participants were females (165, 54%), 294 (97%) were Igbos and 198 (65%) had no known family history of glaucoma; 126 (42%) had past medical history of hypertension, stroke, diabetes mellitus or a combination of these (Table ).

Table 1. Frequency and unadjusted odds of late presentation for socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

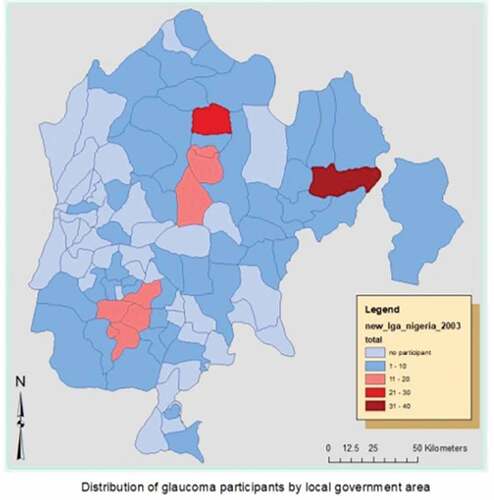

The five states (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Imo) in south eastern Nigeria are made up of 95 local government areas (LGA). Randomly, study participants came from 55 LGAs as shown in the map (Figure ); with majority from areas that are close to the study sites (pink and red areas). Tables describe the frequency as well as the odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals and significance level for demographic, ocular and medical history characteristics of the study participants. While Table outlines the multivariate regression of health service-related modifiable risks associated with late presentation among glaucoma patients.

Figure 1. Map of South-East Nigeria showing local government areas with distribution of study participants.

Table 2. Frequency and unadjusted odds of late presentation for ocular and medical demographic characteristics of the study participants

Table 3. Multiple variable logistic regression of health-service-delivery modifiable risk factors for late presentation

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that late presentation and advanced glaucoma are significant causes of blindness hence the aim of this study to identify modifiable risk factors to inform strategies and improve the outcome of glaucoma patients in South-East, Nigeria.

Three of the identified independent variables associated with late presentation at the univariate level as shown in Tables , namely location of participant, measured blood pressure (hypertension) and awareness about glaucoma before diagnosis, were considered modifiable and adjusted by age and sex for the purpose of this study. These were selected based on clinical and personal experiences of the researchers, considering that well-directed public health strategies (health system perspective) for these risk factors could decrease late presentation among glaucoma patients in the region (Table ).

This study further demonstrated that increasing age is an independent risk factor for late presentation and is compounded by the fact that glaucoma prevalence and incidence increases with age. This trend has been shown by several studies (Motlagh and Pirbazari (Citation2016), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999b), Ntim-Amponsah et al. (Citation2005)). However, two of them didn’t find statistical significance (Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999b)), one was a pilot study (Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999b)) and both studies were predominantly among Caucasians which may account for the difference in this finding. Similarly, rural dwellers were found to have higher odds of presenting late. This correlated with ageing because it is consistent with the culture of the Igbos, the predominant residents in the study region, to retire to the village at a certain age. Early presentation among urban dwellers may be due to an increased level of awareness from eye health campaigns or proximity to the tertiary treatment facilities located in the urban areas. Motlagh et al. (Motlagh and Pirbazari (Citation2016)) demonstrated similar results while other studies have associated living in socially deprived areas to late presentation and blindness (Kyari et al. (Citation2016), Fraser et al. (Citation2001)).

Male sex has consistently been identified as a risk factor for glaucoma Kyari et al. (Citation2016) and late presentation in glaucoma (Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999b), Ntim-Amponsah et al. (Citation2005)) and this study demonstrated a similar result for the latter. The reason for late presentation found more among men maybe due to their pivotal role as the bread winner in the African context. This role probably results in a lower tendency to present for screening or follow up as their personal eye care may be less prioritized than other family needs since the disease is largely asymptomatic in the early stages.

The presence of measured high blood pressure was another risk factor in this study and there seems to be no known hypothesis linking it directly to late presentation. However, raised intraocular pressure which is a direct risk factor for glaucoma progression has been shown to co-exist with hypertension, possibly due to both sharing the same patho-physiology of vascular dysfunction (He et al. (Citation2011)). Therefore, adding a routine eye exam for patients with high blood pressure during routine blood pressure checkup could be a strategy to explore in improving early presentation. No previous study has assessed measured high blood pressure as a risk for late presentation. Conversely, it has been demonstrated that previous medical history of hypertension and other systemic diseases are not a significant predictor for early presentation as shown in this study and similar ones (Motlagh and Pirbazari (Citation2016), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999a), Fraser, Bunce, Wormald et al., Citation1999b), Ntim-Amponsah et al. (Citation2005)). One hypothesis is that contact with the health system for other systemic diseases could influence earlier presentation. Unfortunately, this is not so in our study, probably due to distance between the physicians’ and ophthalmologists’ offices or the asymptomatic attributes of early glaucoma.

Prior awareness about glaucoma was shown to be an independent risk factor among patients in this study with 53% lower odds of late presentation among those who had previously heard about glaucoma compared with those who hadn’t. Generally, awareness about glaucoma has been demonstrated to be poor among glaucoma patients prior to diagnosis (Kyari et al. (Citation2018), Kizor-Akaraiwe et al. (Citation2017)). From the results of this study, there is a need to increase glaucoma awareness which will in turn probably increase self-referral for screening; as well as increase knowledge of where, whom and how often to consult an Ophthalmologist. With appropriate sensitizations to relevant stakeholders especially government buy-in, efforts to improve glaucoma awareness can be sustained over a long term. Government ownership and community participation are the major attributes proposed in the global action plan (GAP) to ensure the sustainability of eye care programmes (WHO (Citation2014)).

Limitation and strength—This study was limited by being hospital-based; therefore results cannot be extrapolated to the general population, however its strengths were based on the spread of participants recruitment involving 3 large glaucoma referral centres within the eastern region.

Conclusion—Increasing age, male gender, rural dwelling, high blood pressure and no prior awareness about glaucoma are risk factors for late presentation among Glaucoma patients attending eye care facilities in the South Eastern part of Nigeria. Health facility measures to address these predictors can be achieved through targeted and cost-effective approaches involving existing health care delivery systems. Opportunistic eye exams on patients with high blood pressure and sustained awareness campaigns are possible strategies to be explored to reach the groups with high risk of late presentation.

Notes on contributor

The project was carried out by research team made of ophthalmologists, research assistants, data scientist/statistician as part of an MSc in public health for eye care dissertation, led by the principal investigator Onyinye Onyia Dr. My research interest is in health prevention and promotion for glaucoma, microbial keratitis, school/child eye health and immunization preventive eye conditions. This research provides results that feeds a broader aim of identifying key areas and modalities that will improve the implementation of an effective and efficient primary eye service delivery by engaging locally sourced human resources within the communities in low-resource settings.

Criteria for inclusion in the authors list

All authors were involved in all stages of the research; proposal design, revision, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation as well as manuscript preparation.

g) I hereby affirm that this manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, the requirements for authorship according to the journal’s regulations have been met, and that each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Acknowledgements

My sponsors

Commonwealth Shared Scholarship Commission

Commonwealth Eye Health Consortium

Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust

International Students House

The School

The International Centre for Eye health staff

Romulo Fabunan, the Students and Alumni engagement staff

Proposal review panel led by Prof Allen Foster

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

For facilitating the process and providing the enabling platform for learning

Academic supportMy supervisor, statisticians, trainers and mentors who guided me through the principles that supported this work;

Local support

The study hospitals management, heads of department, consultants and members of the ophthalmic team in Nigeria

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Onyinye Onyia

Onyinye Onyia. BSc. Parasitology and Entomology (Nnamdi Azikiwe University 2000), MBBS (University of Nigeria 2008), Fellow Medical College of Nigeria Ophthalmology (FMCOph 2017), Fellow West African College of Surgeons (FWACS 2018), MSc. Public Health for Eye Care (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine 2019), Scholar, PhD Public Health (Health System Management), World bank African Centre of Excellence for Public Health and Toxicology Research (ACEPUTOR) University of Port-Harcourt, Rivers State 2020 till date.

References

- Abdull, M. M., Chandler, C., & Gilbert, C. G. (2016). “the silent thief of sight”: Patients’ perspectives and health seeking behaviour in Bauchi, northern Nigeria. BMC Ophthalmology, 16(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-016-0220-6

- Awoyesuku, E. A., & Ejimadu, C. S. (2012). Visual disability in newly diagnosed primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) patients in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine: Journal of the National Association of Resident Doctors of Nigeria, 21(1):78–80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23301454

- Budenz, D. L., Barton, K., Whiteside-de Vos, J., Schiffman, J., Bandi, J., Nolan, W., Herndon, L., Kim, H., Hay-Smith, G., Tielsch, J. M., & Tema Eye Survey Study Group, F. T. (2013). Prevalence of glaucoma in an Urban West African population: The tema eye survey. JAMA Ophthalmology, 131(5):651–658. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.1686

- Coleman, A., & Miglior, S. (2008). Risk factors for glaucoma onset and progression. Survey of Ophthalmology, 53(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.006

- Enock, M. E., Omoti, A. E., & Momoh, R. O. (2010). Glaucoma in a suburban tertiary care hospital in Nigeria. Journal of Ophthalmic & Vision Research, 5(2):87–91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22737336

- Fraser, S., Bunce, C., & Wormald, R. (1999a). Risk factors for late presentation in chronic glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 40(10):2251–2257. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10476790

- Fraser, S., Bunce, C., & Wormald, R. (1999b). Retrospective analysis of risk factors for late presentation of chronic glaucoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 83(1):24–28. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.83.1.24

- Fraser, S., Bunce, C., Wormald, R., & Brunner, E. (2001). Deprivation and late presentation of glaucoma: Case-control study. BMJ. 322(7287):639–643. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7287.639

- He, Z., Vingrys, A. J., Armitage, J. A., & Bui, B. V. (2011). The role of blood pressure in glaucoma. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 94(2):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1444-0938.2010.00564.x

- Heijl, A., Leske, M. C., Bengtsson, B., Hussein, M., Hyman, L., Bengtsson, B., & Hussein, M. (2002). Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: Results from the early manifest glaucoma trial. Archives of Ophthalmology, 120(10):1268–1279. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12365904

- ICO. (2016). ICO Guidelines for Glaucoma Eye Care. Retrived 2019 Jan 16: http://www.icoph.org/downloads/ICOGlaucomaGuidelines.pdf

- Isawumi, M. A., Hassan, M. B., Akinwusi, P. O., Adebimpe, O. W., Asekun-Olarinmoye, E. O., Christopher, A. C., & Hassan, M. (2014). Awareness of and attitude towards glaucoma among an adult rural population of Osun State, Southwest Nigeria. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology, 21(2):165–169. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.129769

- Kizor-Akaraiwe, N. N., Monye, H. I., & Okeke, S. (2017). Awareness and knowledge about glaucoma and proportion of people with glaucoma in an urban outreach programme in Southeast Nigeria. BMJ Open Ophthalmology, 1(1):e000018–27. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2016-000018

- Kyari, F., Abdull, M. M., Bastawrous, A., Gilbert, C. E., & Faal, H. (2013). Epidemiology of glaucoma in sub-saharan Africa: Prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology. 20(2):111–125. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.110605

- Kyari, F., Abdull, M. M., Sallo, F. B., Spry, P. G., Wormald, R., Peto, T., Faal, H. B., & Gilbert, C. E. (2015). Nigeria normative data for defining glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 22(2):98–108. https://doi.org/10.3109/09286586.2015.1012268

- Kyari, F., Abdull, M. M., Wormald, R., Evans, J. R., Nolan, W., Murthy, G. V. S., & Gilbert, C. E. (2016). Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma in Nigeria: Results from the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. BMC Ophthalmology, 16:78. (1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-016-0264-7

- Kyari, F., Adekoya, B., Abdull, M. M., Mohammed, A. S., & Garba, F. (2018). The current status of glaucoma and glaucoma care in Sub-Saharan Africa. Asia-Pacific Journal Ophthalmol. 7(6):375–386. http://www.apjo.org/Apjo/pdf/id/639.html

- Kyari, F., Entekume, G., Rabiu, M., Spry, P., Wormald, R., Nolan, W., Murthy, G. V. S., & Gilbert, C. E. (2015). A population-based survey of the prevalence and types of glaucoma in Nigeria: Results from the Nigeria national blindness and visual impairment survey. BMC Ophthalmology, 15:176. (1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-015-0160-6

- Kyari, F., Wormald, R., Murthy, G. V. S., Evans, J. R., & Gilbert, C. E., Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Study Group. (2016). Ethnicity and deprivation are associated with blindness among adults with primary glaucoma in Nigeria. Journal of Glaucoma. 25(10):e861–72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27479370%5Cnhttp://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00061198-201610000-00023

- Motlagh, B. F., & Pirbazari, T. J. (2016). Risk factors for late presentation of chronic glaucoma in an Iranian population. Oman Journal of Ophthalmology, 9(2):97. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-620X.184527

- Ntim-Amponsah, C. T., Amoaku, W. M. K., Ewusi, R. K., Idirisuriya-Khair, R., Nyatepe-Coo, E., & Ofosu-Amaah, S. (2005). Evaluation of risk factors for advanced glaucoma in Ghanaian patients. Eye, 19(5):528–534. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701533

- Ntim-Amponsah, C. T., Amoaku, W. M. K., Ofosu-Amaah, S., Ewusi, R. K., Idirisuriya-Khair, R., Nyatepe-Coo, E., & Adu-Darko, M. (2004). Prevalence of glaucoma in an African population. Eye, 18(5):491–497. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700674

- Olawoye, O. O., & Sarimiye, T. S. (2014). Is angle closure glaucoma a problem in Nigeria? Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 17(2):159–162. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.127425

- Omoti, A. E., Osahon, A. I., & Waziri-Erameh, M. J. M. (2006). Pattern of presentation of primary open-angle glaucoma in Benin City, Nigeria. Tropical Doctor, 36(2):97–100. https://doi.org/10.1258/004947506776593323

- Pascolini, D., & Mariotti, S. (2012). Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 96(5), 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539

- Quigley, H., & Broman, A. (2006). The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 90(3):262–267. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2005.081224

- Susanna, R., De Moraes, C. G., Cioffi, G. A., Ritch, R., & Ritch, R. (2015). Why do people (Still) go blind from glaucoma? Translational Vision Science & Technology, 4(2):1. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.4.2.1

- Tham, Y.-C., Li, X., Wong, T. Y., Quigley, H. A., Aung, T., & Cheng, C.-Y. (2014). Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 121(11):2081–2090. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24974815

- WHO. (2014). Universal eye health: A global action plan. http://www.who.int/blindness/AP2014_19_English.pdf?ua=1