Abstract

Abstract: Africa serves as a rich research mine due to its significant contribution to the global burden of diseases. This study sought to analyze the trends in African journals as a means to further characterize the research landscape on the continent. The African Journals Online (AJOL) database was searched from inception to 17 October 2021 and 173 journals were identified. Journal titles were then used to search nine databases via the Web of Science core collection on 16 December 2021. Journal metadata was analysed using summary descriptive statistics. 58,952 articles published by 40 journals between 1972 and 2021 were found. 62.4% (n = 36,806) were original articles with 66.4% (n = 39,118) focused on general internal medicine and 44.5% (n = 26,251) were published by the South African Medical Journal. Most authors were located in South Africa, Nigeria, China, Morocco and the United States. Top 5 author-assigned keywords were Nigeria, COVID-19, HIV, Children and Prevalence. Most popular database-assigned keywords were Prevalence, Management, Risk, Children and Disease. The African research community makes significant contributions to the literature. However, the continued ability of researchers to embark on critical scientific investigations can be further improved by increased investment and collaborations.

1. Introduction

Africa’s contribution to global medical research is very modest—an anomaly that contrasts with the continent’s contribution to the global disease burden (Perez-Iratxeta & Andrade, Citation2002; Uthman & Uthman, Citation2007). Although scholarly output is positively correlated with population and country size (Uthman & Uthman, Citation2007), there are disparities that cannot be explained by differences in the population of African countries, presumably because a country’s national researcher population should increase with an increasing total national population. Unfortunately, this assumption does not hold true in Africa where for example, four of the ten most populous African countries are low-income countries while the rest are lower-middle-income countries (Bank, Citation2021). Low- and middle-income countries face multiple competing challenges relating to public health, infrastructure, and education, as such investments into research are limited (Uthman & Uthman, Citation2007). As a result, Northern and Southern African countries that tend to have better national economic dispositions (Bank, Citation2021) equally have higher national researcher densities and mean publications per researcher than their counterparts in Western, Central, and Eastern Africa (Garg et al., Citation2022; K. J. Hofman et al., Citation2009; Kanmounye et al., Citation2020; Kebede et al., Citation2014).

The historical lack of research investment and disproportionately high burden of disease in Africa left a gap that was filled by foreign funding agencies such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, National Institute of Health-Fogarty, Wellcome Trust, development aid agencies, and other multilateral civil society organizations (Kebede et al., Citation2014). This external funding has helped build capacity, invest in infrastructure, and increase health research output in Africa especially in low-income countries (Kebede et al., Citation2014; Maher et al., Citation2020). However, we must note that the effects of external funding for health research in Africa have not all been positive. The earmarking and allocation of funds to certain diseases and interventions is thought to have skewed the research landscape away from local priorities (ADEYI, Citation2021). Additionally, the insistence that at least one of the grant applicants must be from a high-income country has stunted the development of local health research capacity in favor of Western researchers and institutions (Hedt-Gauthier et al., Citation2019).

Although the challenges mentioned in the previous paragraphs paint a grim picture of the state and future of African health research, we believe they represent an opportunity for improvement. For this to happen, we must first understand the African health research ecosystem. Bibliometric analyses can help quantify and describe the actors, output, and interactions in African health research. Stakeholders of African health research can use the information from bibliometric studies to foster collaborations aimed at building capacity in low scholarly output areas. For example, they can use quantitative bibliometrics to identify high- and low-performing institutions and countries and social networking analysis of published articles to identify collaboration networks and patterns (Donthu et al., Citation2021; Obajemu et al., Citation2014). In addition, thematic analysis of published articles can help identify neglected research topics and this information can help advocate for funding and investigation (Donthu et al., Citation2021).

African journals contribute critical literature with wide-ranging relevance, both on the continent and globally. However, most bibliometric analyses are topic, journal, or country-specific (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Akhaddar, Citation2019; Guleid et al., Citation2021; K. Hofman et al., Citation2006; Kanoute et al., Citation2012; Maina et al., Citation2021; Mbuagbaw et al., Citation2021). This bibliometric analysis aims to map out the landscape of African health research as a unit, identify popular topics, and describe their global trends. We used the African Journals Online Library (AJOL) database to identify relevant peer-reviewed publications as AJOL is the largest repository of African journals and contains journals that are not indexed in major databases such as PubMed.

The study findings may help verify if the African health research landscape is indeed skewed by external funding. For example, stakeholders may compare thematic popularity within African health research with the continental burden of disease to identify discrepancies between research output and disease burden. In addition, by mapping intra- and extra-continental research collaborative networks, we will inform the elaboration of novel research collaboratives particularly between less productive and more productive research institutions and nations.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy, data sources, and data extraction

Three authors (OO, ADT, and USK) searched the African Journals Online Library (AJOL) from database inception (i.e., 1900) to 17 October 2021. One hundred and seventy-three health journals were identified and recorded in Excel 2019 for Mac (Microsoft Corp. WA, USA). These journal titles were then used to search nine databases via the Web of Science Core Collection on 16 December 2021. The search strategy is available in Supplemental File 1, Search Strategy. Journal authors were de-duplicated. The journal metadata were downloaded as text files and uploaded to VOSViewer for Mac version 1.6.17, released on 22 July 2021 (Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University, The Netherlands). VOSViewer was chosen over other bibliometric software because it allows the analysis of bibliometric metadata from numerous databases and provides free and visually appealing social mapping. In addition, the software’s user interface is friendly and its learning curve is not steep.

2.2. Data analysis

Social networks are made up of circles (also called nodes) and lines (also called links). In bibliometrics, the circles can represent authors, institutions, countries, journals, articles, or keywords. The circle size is directly proportional to its connectivity with other circles within the network and is a proxy of the node’s influence. Circles are grouped into clusters, i.e., circles that share multiple links together. Circles within a cluster share a common color and are organized around a central node. Lines represent co-occurrences between network nodes and their lengths are inversely proportional to the link strength i.e., shorter links are stronger. The total link strength is an aggregate measure of the link strength within a network and describes connectivity.

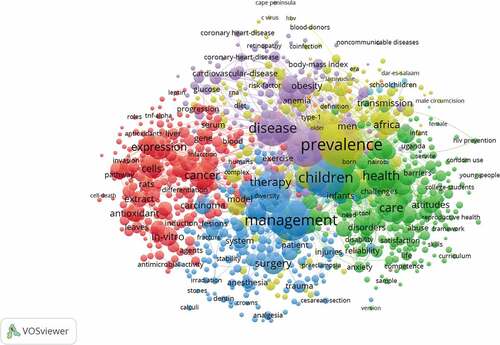

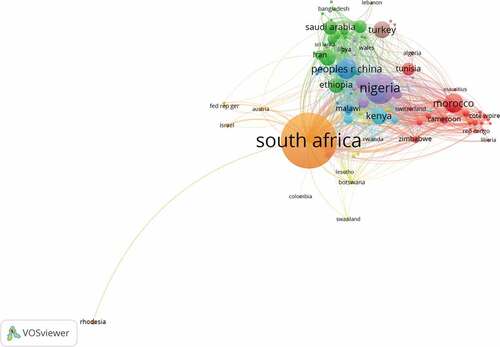

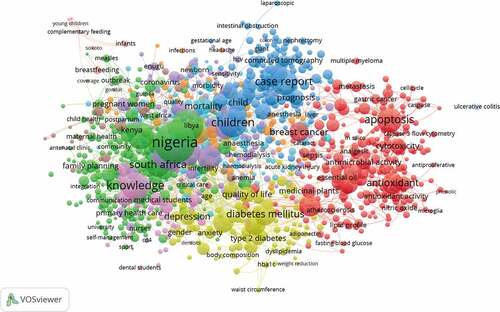

Quantitative and qualitative data were described using summary descriptive analyses. The country-level co-authorship social network was built for countries with ≥10 publications (i.e. 106 countries yielding 9 clusters, 1,351 links, and 7,217 total link strength). The total link strength is a measure of the strength of collaboration between researchers, institutions, or themes. The authors analyzed the articles’ contents using author-assigned keywords and KeyWords plus (i.e., keywords assigned by the Web of Science Core Collection database). The author-assigned keyword social network was built for keywords with ≥5 occurrences yielding 12 clusters, 16,204 links, and 25,336 total link strength. Additionally, the database-assigned keyword social network was built for keywords with ≥5 occurrences yielding 10 clusters, 43,134 links, and 84,438 total link strength.

3. Results

3.1. Summary descriptive data

The AJOL search returned 173 health journals while the Web of Science search returned 58,952 articles published by 40 journals between 1972 and 2021. Most articles were original articles (62.4%, n = 36,806), focused on general internal medicine (66.4%, n = 39,118), and published by the South African Medical Journal (44.5%, n = 26,251; Table ). The 98,532 authors of these articles were affiliated to 15,326 institutions; the majority of them located in South Africa (15,050 articles, 69,558 citations, 1,535 total link strength), Nigeria (4,469 articles, 21,413 citations, 830 total link strength), China (2,046 articles, 5,646 citations, 189 total link strength), Morocco (1,823 articles, 1,344 citations, 109 total link strength), the United States of America (1,429 articles, 7,826 citations, 1,447 total link strength), Turkey (1,373 articles, 4,944 citations, 87 total link strength), India (1,316 articles, 7,621 citations, 221 total link strength), Kenya (1,311 articles, 6,601 citations, 402 total link strength), Ethiopia (1,099 articles, 6,030 citations, 305 total link strength), and Saudi Arabia (946 articles, 2,722 citations, 536 total link strength; Figure ).

Figure 1. Social network illustrating collaborations at the national level between institutions to which the authors of African health articles are affiliated with.

Table 1. Summary descriptive characteristics of articles published by African health journals

3.2. Article content analysis

There were 41,095 unique author-assigned keywords and 22,721 KeyWords Plus. Only a fraction of author-assigned (6.3%, n = 2,599) and database-assigned (11.8%, n = 2,677) keywords had ≥5 occurrences. The most common author-assigned keywords were Nigeria (732 occurrences, 1,261 total link strength), COVID-19 (442 occurrences, 863 total link strength), HIV (358 occurrences, 754 total link strength), children (352 occurrences, 555 total link strength), prevalence (343 occurrences, 730 total link strength), knowledge (335 occurrences, 836 total link strength), case report (294 occurrences, 257 total link strength), Ethiopia (289 occurrences, 502 total link strength), and pregnancy (273 occurrences, 425 total link strength; Figure ).

Figure 2. Social network of author-assigned keywords in African health research and with five or more occurrences.

The most popular database-assigned keywords were prevalence (1,238 occurrences, 4,565 total link strength), management (1,006 occurrences, 2,486 total link strength), risk (948 occurrences, 3,464 total link strength), children (907 occurrences, 2,463 total link strength), disease (766 occurrences, 2,316 total link strength), diagnosis (628 occurrences, 1,558 total link strength), women (589 occurrences, 2,113 total link strength), mortality (586 occurrences, 2,057 total link strength), risk factors (582 occurrences, 2,201 total link strength), and infection (488 occurrences, 1,547 total link strength; Figure ).

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributors

We identified key contributors of health research and popular themes in African journals. South Africa, Nigeria, Morocco, Kenya, and Tunisia were the most prominent intra-continental contributors to African research (Figure ). These results are in agreement with other bibliometric analyses (Ajao et al., Citation2002; K. J. Hofman et al., Citation2009; Obajemu et al., Citation2014; Uthman & Uthman, Citation2007). The central role of South Africa may be the result of the high proportion of South African journals and articles published in them (Table ). While South Africa has more journals than most African countries, the proportion of South African journals and articles published in them increased once we used the Web of Science database to collect bibliometric data. Only 40 of the 173 health journals (23.1%) registered in AJOL were indexed on the Web of Science database and all South African journals were indexed. The high proportion of AJOL health journals that are not indexed in Web of Science is a sign of African research’s limited visibility and an opportunity for collaboration between Southern African journals or other journals.

Of note, the top non-African contributors in this study were the United States of America, China, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia (Figure ). This contrasts with previous studies that found researchers affiliated with Western countries contributed most to health research on or about Africa (Hedt-Gauthier et al., Citation2019; Kanmounye et al., Citation2020). The discrepancy between our findings and previous studies can be attributed to our decision to include AJOL indexed journals. As a result, we excluded articles on African health published in non-African journals. This finding suggests that African health research articles in non-African journals tend to have a higher number of Western authors. Numerous study findings support this hypothesis including the fact that non-African journals tend to be more reputable (i.e., greater readership, higher impact factor, and association with internationally-renowned professional societies) and are more likely to accept an article if it has a Western author (Harris et al., Citation2017).

4.2. Scope and thematic analysis

The majority of articles in this analysis were focused on internal medicine and public health, however, the articles were diverse covering multiple aspects of clinical and biomedical disciplines. The thematic analysis revealed the majority of articles were focused on child health, maternal health, infectious diseases, and epidemiology (Figures ). This finding is to be expected given that these themes have been prioritized by African governments and the global health community (Abdalla et al., Citation2020; Organization, Citation2020). The scope of published health research is influenced by the preferences of gatekeepers (ex: funding agencies, journal editors and reviewers, and professional associations) who facilitate the publication of what they consider relevant research while barring the way to less important research. This practice has led to the over-prioritization of certain diseases in lieu of other diseases. For example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, maternal health, child health, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis took the lion’s share of scholarly funding and productivity. While we recognize that these conditions have plagued the continent for decades, it does not justify the neglect of other areas such as non-communicable diseases, injuries, and surgical diseases. Advocates for the over-prioritization of these diseases had the tables turned on them when SARS COVID-19 commanded attention and resources away from them (Guleid et al., Citation2021).

The paucity of basic biomedical research and Phase 1 clinical trials is also a cause for concern. Bench and Phase 1 clinical trial studies are the bedrock of scientific innovation. The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the need for investment in foundational research for the development of diagnostic and therapeutic modalities (Fleming et al., Citation2021; Ondoa et al., Citation2020, Citation2021).

4.3. Next steps

There is an urgent need for an increased collaborative effort between African health researchers, publishers, academic institutions, governments, and the global scientific community. African health research needs to grow beyond the basic clinical research realm (which largely focuses on gathering epidemiological data), while implementing a biomedical approach, with foundational economic, political, and social input from relevant disciplines in medical research. Professional medical associations, academic institutions, health ministries, commercial publishers, and multilateral health agencies within and outside Africa also need to come together to develop policies and establish high-impact journals that will have regular output quotas following standard scientific publishing ethics. This will require increased allocation of funding for research and the development of collaborative networks that span the continent and beyond. With attendant focus on developing local research ecosystems, there will naturally be opportunities for pursuing and publishing studies with immediate relevance for local communities.

Existing journals should embrace the open access and open internet system which makes scientific data available for use by anyone with access to the internet. An incentive financial model of journal publishing may be employed where hybrid options of open access are given to authors where journals get enough revenue to keep in business while making scientific data freely available. Where possible, preference should be given to research from indigenous authors as a means to build their research portfolio and enhance their visibility.

4.4. Limitations

This article has a few limitations. First, only a fraction of AJOL indexed health journals were registered on Web of Science. As a result, a significant proportion of AJOL journals and their articles were not analyzed. We chose AJOL because it is the largest database of African health journals, however, AJOL does not have a structured search function or bibliometric metadata. As such, getting these vital data would have meant extracting them manually from all articles published in the 173 journals. The manual extraction of authorship affiliations, keywords, and citation metrics would have been physically impossible in a reasonable timeframe and prone to information bias. Web of Science has a structured boolean search and bibliometric metadata that can be exported automatically into a CSV or text file although only for a fraction of African health journals. Given this limitation, we recognize that the generalizability of our findings to all African health journals is limited. Nevertheless, we believe these findings give a valuable insight into the complex and understudied African health research landscape.

Our understanding of the African health research landscape would have been more complete had we included an assessment of the study quality and level of evidence. While this information would have been valuable, we lacked the resources needed to evaluate the quality and level of evidence for all 58,952 articles.

5. Conclusion

The African research community contributes substantial knowledge to the literature on various topics. Analyses such as these shed more light on the scope of research topics discussed in African journals as well as existing collaborative networks within the continent, thus providing a robust framework for understanding the African research landscape. With continued investments in research infrastructure, from the conception of ideas to the publishing of articles, the continent is poised to continue to provide essential literature with immediate relevance to their population.

Supplemental files

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/27707571.2022.2127230.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Association of Future African Neurosurgeons for its continued support

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdalla, S. M., Solomon, H., Trinquart, L., & Galea, S. (2020). What is considered as global health scholarship? A meta-knowledge analysis of global health journals and definitions. BMJ Global Health, 5(10), e002884. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002884

- ADEYI, O. (2021). Global health, narcissistic charity, and neo-dependency. Development Today. Retrieved February 12, 2022 https://www.development-today.com/archive/dt-2021/dt-9–2021/global-health-narcissistic-charity-and-neo-dependency

- Ahmed, M. O., van Velkinburgh, J. C., & Daw, M. A. (2018). Analysis of biomedical publications in Libya from 2003 to 2013. Education for Health (Abingdon, England), 31(3), 187–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.EfH_222_16

- Ajao, O. G., Ajayi, O. O., Soyannwo, O. A., & Iginla, M. I. (2002). A brief history of and an analysis of manuscripts submitted to West African Journal of Medicine. West African Journal of Medicine, 21(4), 332–334. https://doi.org/10.4314/wajm.v21i4.28015

- Akhaddar, A. (2019). African contribution to the world neurosurgical literature during the past two decades (1999–2018) using PubMed database. World Neurosurgery, 126, 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.095

- Bank, T. W. (2021). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Publisher World Bank. Retrieved February 12, 2022 https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

- Fleming, K. A., Horton, S., Wilson, M. L., Atun, R., DeStigter, K., Flanigan, J., Sayed, S., Adam, P., Aguilar, B., Andronikou, S., Boehme, C., Cherniak, W., Cheung, A. N., Dahn, B., Donoso-Bach, L., Douglas, T., Garcia, P., Hussain, S., Iyer, H. S., & Walia, K. (2021). The lancet commission on diagnostics: Transforming access to diagnostics. The Lancet, 398(10315), 1997–2050. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00673-5

- Garg, K., Chaurasia, B., Gienapp, A. J., Splavski, B., & Arnautovic, K. I. (2022). Bibliometric analysis of publications from 2011–2020 in 6 Major Neurosurgical Journals (Part 1): Geographic, demographic, and article type trends. World Neurosurgery, 157, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.091

- Guleid, F. H., Oyando, R., Kabia, E., Mumbi, A., Akech, S., & Barasa, E. (2021). A bibliometric analysis of COVID-19 research in Africa. BMJ Global Health, 6(5), e005690. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005690

- Harris, M., Marti, J., Watt, H., Bhatti, Y., Macinko, J., & Darzi, A. W. (2017). Explicit bias toward high-income-country research: A randomized, blinded, crossover experiment of English clinicians. Health Affairs, 36(11), 1997–2004. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0773

- Hedt-Gauthier, B. L., Jeufack, H. M., Neufeld, N. H., Alem, A., Sauer, S., Odhiambo, J., Boum, Y., Shuchman, M., & Volmink, J. (2019). Stuck in the middle: A systematic review of authorship in collaborative health research in Africa, 2014–2016. BMJ Global Health, 4(5), e001853. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001853

- Hofman, K. J., Kanyengo, C. W., Rapp, B. A., & Kotzin, S. (2009). Mapping the health research landscape in Sub-Saharan Africa: A study of trends in biomedical publications. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 97(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.007

- Hofman, K., Ryce, A., Prudhomme, W., & Kotzin, S. (2006). Reporting of non-communicable disease research in low- and middle-income countries: A pilot bibliometric analysis. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 94(4), 415–420. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17082833

- Kanmounye, U. S., Tochie, J. N., Mbonda, A., Wafo, C. K., Daya, L., Atem, T. H., Nyalundja, A. D., & Eyaman, D. C. (2020). Systematic review and bibliometric analysis of African anesthesia and critical care medicine research part I: Hierarchy of evidence and scholarly productivity. BMC Anesthesiology, 20(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-020-01167-8

- Kanoute, A., Faye, D., & Bourgeois, D. (2012). Current status of oral health research in Africa: An overview. International Dental Journal, 62(6), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00123x

- Kebede, D., Zielinski, C., Mbondji, P. E., Sanou, I., Kouvividila, W., & Lusamba-Dikassa, P.-S. (2014). Expenditures on health research in sub-Saharan African countries: Results of a questionnaire-based survey. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107(1_suppl), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814530601

- Maher, D., Aseffa, A., Kay, S., & Tufet Bayona, M. (2020). External funding to strengthen capacity for research in low-income and middle-income countries: Exigence, excellence and equity. BMJ Global Health, 5(3), e002212. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002212

- Maina, M. B., Ahmad, U., Ibrahim, H. A., Hamidu, S. K., Nasr, F. E., Salihu, A. T., Abushouk, A. I., Abdurrazak, M., Awadelkareem, M. A., Amin, A., Imam, A., Akinrinade, I. D., Yakubu, A. H., Azeez, I. A., Mohammed, Y. G., Adamu, A. A., Ibrahim, H. B., Bukar, A. M., Yaro, A. U., & Baden, T. (2021). Two decades of neuroscience publication trends in Africa. Nature Communications, 12(1), 3429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23784-8

- Mbuagbaw, L., Schoonees, A., Oliver, J., Arikpo, D., Durao, S., Effa, E., Hohlfeld, A., Kredo, T., Wiysonge, C. S., & Young, T. (2021). Publication practices of sub-Saharan African Cochrane authors: A bibliometric study. BMJ Open, 11(9), e051839. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051839

- Obajemu, A. S., Akinade, H. O., & Osagie, J. N. (2014). Bibliometric/scientometric investigation of African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences between 2001–2010. African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, 43(2), 115–125. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25474986

- Ondoa, P., Kebede, Y., Loembe, M. M., Bhiman, J. N., Tessema, S. K., Sow, A., Sall, A. A., & Nkengasong, J. (2020). COVID-19 testing in Africa: Lessons learnt. The Lancet Microbe, 1(3), e103–e104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30068-9

- Ondoa, P., Oskam, L., Loembe, M. M., & Okeke, I. N. (2021). Transforming access to diagnostics: How to turn good intentions into action? The Lancet, 398(10315), 1947–1949. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02182-6

- Organization, W. H. (2020). WHO reveals leading causes of death and disability worldwide: 2000–2019. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 12, 2022 https://www.who.int/news/item/09-12-2020-who-reveals-leading-causes-of-death-and-disability-worldwide-2000-2019

- Perez-Iratxeta, C., & Andrade, M. A. (2002). Worldwide scientific publishing activity. Science, 297(5581), 519. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.297.5581.519b

- Uthman, O. A., & Uthman, M. B. (2007). Geography of Africa biomedical publications: An analysis of 1996–2005 PubMed papers. International Journal of Health Geographics, 6(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-6-46