Abstract

: Insulin treatment is seriously influenced by the choice of injection site and storage practices. The study looked at the storage mechanisms and injection site preferences of type 2 diabetes patients at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, in Dessie City Administration, North-East Ethiopia. We conducted a qualitative study from July 2019 to January 2020 on twenty-four (11 males and 13 females) participants who were recruited purposefully. Until theoretical saturation was reached, we collected the data through face-to-face, in-depth interviews that lasted about 23 to 71 minutes and organized it using QDA Miner Lite v2.0.9. We then thematically analyzed the transcripts and discussed the themes that arose in detail using narrative strategies. A jar filled with wet sand was the most common handling device for insulin, for both insulin in use and reserves, both at home and on the road. The most popular injection site was the abdomen, followed by the thighs and upper arms. With the container they indicated, it is unclear how the patients store insulin. The dangers of storing insulin at home are often disregarded, and better education is required. Practical advice on how to properly keep insulin at home is also essential.

Public interest statement

Without proper handling, medicines, especially hormonal ones like insulin, could not maintain their ability to heal. This is so because insulin’s strength greatly depends on how well it is protected from unfavorable temperatures, humidity, and light. The manner in which it is administered to the body also has a significant impact on its effectiveness. Hence, this study investigated the storage methods of insulin and the preferred injection sites of patients with type 2 diabetes.

1. Introduction

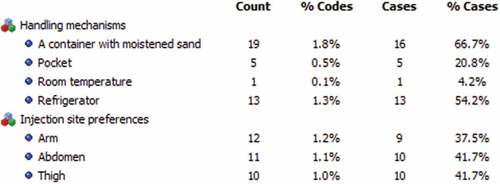

Irrational drug storage at home is a global issue (Jafarzadeh et al., Citation2021). The storage conditions of pharmaceutical items after dispensing are poorly understood (Alqurshi, Citation2020). On the other hand, the medicine shortage crisis causes increased financial losses and puts people’s health in jeopardy (Bayked et al., Citation2021; Lucca et al., Citation2019). Storage of diabetic supplies properly can ensure potency and blood glucose control (Petrie, Citation2015). Proper storage of diabetic drugs is necessary to maintain strength and allow precise dosing (Heinemann et al., Citation2021). So, diabetic medicines, whether insulin or non-insulin, require proper storage to maintain their stability, potency, and effectiveness (Altebainawi et al., Citation2020; Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017). However, insulin is still an important option, and many patients with Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) require it (Oosthuizen, Citation2019). It is extremely sensitive to a variety of environmental influences (Netere et al., Citation2020). Its stability may be jeopardized if it is exposed to external forces (Heinemann et al., Citation2021). It loses its efficacy when exposed to extreme temperatures (United States’ Food and Drug Administration, Citation2018). It must be transferred from the health center to the patient’s house in a specially built box (improvised box; Figure ; Bahendeka et al., Citation2019). It must also be meticulously maintained at home (Toschi, Citation2018) and kept away from direct heat and sunlight (United States’ Food and Drug Administration, Citation2018). It should be kept unopened in the refrigerator (2° to 8°; Tucker, Citation2021; United States’ Food and Drug Administration, Citation2018), and at room temperature for the next 28 days after the seal has been broken (Toschi, Citation2018; Tucker, Citation2021). But little is known how patients with diabetes store insulin (Braune et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. Improvised box for the transportation of insulin from the health facility or pharmacy to home (Bahendeka et al., Citation2019).

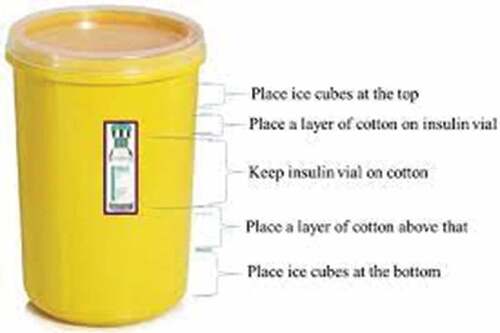

Effective diabetes control requires not only safe handling but also the selection of an injection site. The injection site, needle length, usage of a lifted skinfold, and injection angle must all be considered while administering insulin (Australian Diabetes Educators Association, Citation2015). Since subcutaneous (SC) injections have substantially more consistent pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics than intramuscular (IM) injections (Hirsch & Strauss, Citation2019), insulin is most commonly administered through SC tissue (Shah et al., Citation2016). SC injections are safe and effective in the upper arm, belly, thighs, and upper ventral gluteal area (Figure ; Anderson et al., Citation2018; Drugs.com, Citation2022). Variability in insulin absorption and action in the SC tissue is a cause of glucose variability, making insulin therapy a serious difficulty (Gradel et al., Citation2018). The variability of absorption between them should be considered while choosing a site (American Diabetes Association, Citation2004; Frid et al., Citation2010; Hansen & Matytsina, Citation2011). The abdomen has the fastest rate of absorption, followed by the arms, thighs, and buttocks (American Diabetes Association, Citation2004). So insulin is most effective when injected into the abdomen (Drugs.com, Citation2022),and is most commonly given in the belly (American Diabetes Association, Citation2004; Frid et al., Citation2010). It is critical to rotate the injection site to avoid injection site problems. It is preferable to rotate within one location rather than moving to a different place with each injection. This strategy may help to reduce day-to-day variations in absorption (American Diabetes Association, Citation2004; Hirsch & Strauss, Citation2019).

Figure 2. Insulin injection sites (Drugs.com, Citation2022).

Insulin is a high-risk drug that necessitates extra caution and safety measures. It can be administered through a variety of devices (Figure ; Anderson et al., Citation2018). Pens are the most extensively used insulin delivery devices worldwide, followed by syringes and pumps (Baruah et al., Citation2017; Calliari et al., Citation2018). Insulin is the cornerstone of treatment for a large majority of T2DM patients (Baruah et al., Citation2017). As stated above, insulin storage and administration techniques have an impact on blood sugar control (Kituzi et al., Citation2016). However, insulin delivery, handling, and storage have received little research (Kedogo, Citation2015). As a result, we investigated the storage mechanisms and injection site preferences of T2DM patients.

Figure 3. Insulin delivery devices (Anderson et al., Citation2018).

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics approval statement

The “Research, Community Service, and Graduate Coordinating Office” of Wollo University’s Medicine and Health Science College approved the study (Ref. No. CMHS 443/13/11). Before the interviews began, all participants gave their informed consent. We did not mention the participants’ names. We also kept the collected information confidential.

2.2. Design and setting

We conducted a qualitative investigation from July 2019 to January 2020 at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH) in Dessie City Administration (DCA), North-East Ethiopia. In Ethiopia’s North-East region, DCSH is the region’s largest tertiary hospital (Mekashaw et al., Citation2022a). The DCA was founded in 1882. It is one of the oldest cities in Ethiopia (Mekashaw et al., Citation2022b). It is a multi-ethnic city in northeastern Ethiopia and one of the country’s largest cities.

2.3. Data collection tool and procedures

We used a semi-structured interview guide written in Amharic to collect data (Table ) and conducted face-to-face, in-depth interviews with the help of an audio recorder. Initially, the lead investigator (EMB) identified the participants at the diabetic clinic using the diabetes patients’ registration cards. Then, twenty-four participants who were receiving insulin treatment at DCSH were interviewed. We chose them purposefully on the basis of having no known or overt psychological disorders, being ready to participate, and being able to talk (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). The interviews were conducted during patients’ scheduled appointments, which ranged from 23 to 71 minutes, in spaces free from distractions such as distinct areas of the hospital, isolated cafe spots, guarded work areas, and participants’ houses. Saturation theory was used to determine the number of participants (Daniela, Citation2020).

Table 1. Semi-structured interview guide

2.4. Data processing and analysis

The researchers transcribed the interviews verbatim into MS Word and double-checked them. To verify that the transcripts were understood, we reviewed them several times before they were translated into English. The coding and analysis procedures were started immediately following the first interview and were completed concurrently with data collection. Moving back and forth repeatedly during the coding task revealed more emergent themes and provided a full description of the themes. Line by line, each transcript was coded, and the codes were then arranged into higher-order conceptual themes. Original transcript sections and important quotes were regarded as representative of the evolving topics. The three researchers reviewed the individual codes and topics in group sessions until basic themes and subthemes were agreed upon throughout all of the interviews (Kiger & Varpio, Citation2020). We included memos and notes in the analysis to provide a more conceptual explanation and organized the data analysis using QDA Miner Lite v2.0.9.

2.5. Rigor

To ensure data trustworthiness (Nowell et al., Citation2017), we pretested the interview guide with two T2DM patients, adjusted as needed, and gave back the transcripts to three participants before they were translated into English, who assured that the interpretations were their perceptions and experiences. We also complied with the “Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist” (O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

2.6. Reflexivity

The lead author (EMB) has been part of the community since birth and is familiar with the local slang. He has been a BSc nurse practitioner and lecturer and researcher in social and administrative pharmacy for more than eight years, which made him a suitable researcher for this study. However, his prior knowledge of slang and diabetes could lead to bias if he were unaware of the research process (Dodgson, Citation2019).

3. Result

3.1. Socio-demographic description

We interviewed a total of twenty-four participants (11 men and 13 women). Their minimum and maximum ages were 35 and 75 years, respectively, with an approximate mean age of 55 years. Their ages were 57 and 58 years, respectively, in the median and interquartile range (IQR). The majority of them (n = 17) were married, with six widowed. With respect to occupation, they were farmers, public civil servants, and unemployed (five each), as well as retired, housewives, and merchants (three for each). Most of them (n = 17) were living in rural areas. Orthodox Christians (n = 11) and Muslims (n = 12) made up the majority of the participants. Most (n = 11) of them were illiterate. The approximate average life spans with diabetes and insulin use of the participants were twelve and five years, respectively. They have lived with diabetes for one to thirty-five years, and have taken insulin for one to twenty-five years. The majority of them (n = 13) have been using insulin for one to five years.

3.2. Storage mechanisms

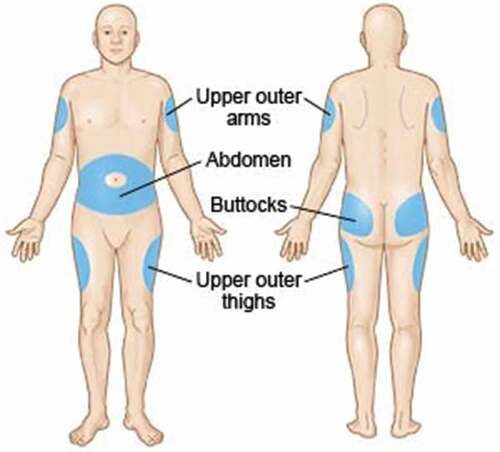

The most popular way of storing (handling) insulin was in a container filled with moistened sand, followed by refrigeration, in pocket and at room temperature (Figure ).

I put it (insulin) in a jar filled with sand and water. I don’t have a fridge. (Female, 60 Years, Basic Literacy)

If you have refrigerator, you should use it. Unless you must use a cup filled with sand and water. Since I have no fridge, I keep it (insulin) as such. It should not be subjected to heat as well. (Female, 38 Years, Illiterate)

I have been storing it (insulin) in a container filled with sand and water. (Female, 36 Years,illiterate)

I crack the mouth of a clay pot or a large clay kettle. After I break it, I fill the container with sand and pour water over it. Then I put the medicine’s vial (insulin) in there. And I keep it (the container) in a windy, cool location. That is how I use it (insulin). (Male, 63 Years, Illiterate)

I put it (insulin) at home. There is a piece of carton. I put moistened sand in that (the carton). There is also a piece of tin, with a size equivalent to tea cup. And I put it in that tin; I put the tin into the carton. And it is there that I have held it. (Male, 46 Years, Illiterate)

I have a container. I bought a single rubber container. And I put tit (insulin) and the needle together in it by covering and sealing. I use it from that when I need it. (Male, 65 Years, Illiterate)

Economic disadvantage in terms of family welfare has been identified as a barrier to purchasing a refrigerator. This was thought to be a stumbling block to effective insulin storage.

I did not have a refrigerator at first. I put it (insulin) in sand moistened with water at a plate. Since my kids are students, I was not able to buy fridge. But now I’m almost two years that I have fridge. Since the kids started working, they bought me a fridge. I put it in a fridge and use it. (Female, 55 Years, Illiterate)

Once the vial was opened, it did not matter if the insulin has been kept at room temperature. If the vial is intact, however, numerous strategies for extending the shelf life of insulin have been used, the most frequent of which is a container filled with moistened sand.

Prior to buying (as the vial was intact), it should be kept in the refrigerator. I only buy one vial and store it in a jar filled with sand and water or in the refrigerator’s bottom shelf. However, I use it with shack because it is usually settled. I used to crawl it around 21 times on my palm. This is how I mix it. NPH is what I’m on at the moment. (Male, 59 Years, Master’s Degree Holder)

I keep the unopened inside fridge. And I set the open with sand and water. When I move, I put it in sand and water with a container, as you can see. (Female, 45 Years, Bachelor’s Degree Holder)

It doesn’t matter if it is stored outside if the vial is open, unless it should be stored in refrigerator. If left unopened, it should be kept in the refrigerator. If there is no refrigerator, sand can be placed with water and put it in other containers. I am using a container with sand and water. I won’t use a fridge if it is opened. (Female, 42 Years, Secondary school completed)

When the patients needed to travel a long distance, they used a container filled with sand and water to handle insulin in the same way they did before.

I’ll take my medicine when I’m on the road. I put sand in a container and filled it with water. I then placed the jar (the container) in my bag, intending to use it there. (Male, 73 Years, Diploma Holder)

I’ll place it in a piece of container with sand and water when I’m on the road. Then I’ll hold it with that to keep it from getting too hot. (Female, 50 Years, Basic Literacy)

3.3. Injection site preferences

The abdomen and thighs were the most popular injection sites, followed by the upper arms (Figure ). The preference of the locations has been influenced by a variety of issues, including the availability of a helper, and the likelihood of injection site complications.

I use the arm, buttock and abdomen to inject, but I usually use abdominal area and arm muscle. I am especially convenient to inject at abdominal area. (Female, 70 Years, Illiterate)

It’s on my arm. The first was on my abdomen. That is what caused me to be wounded. I’ve turned on my arm and am injecting it every morning and evening. (Male, 46 Years, Illiterate)

It’s on my abdomen. It lingers in my abdomen. But when I am stabbed in the arm and leg, fatigue catches me. It’s especially hard on my feet. It fits in my abdomen, switching between sides. (Female, 35 Years, Diploma Holder)

Since I cannot inject on my arm unless someone holds it, it is the area around my abdomen that makes me comfortable. (Female, 42 Years, Secondary School Completed)

4. Discussion

Diabetes affects 10% of adults in the world (International Diabetes Federation, Citation2021). Its management necessitates more than just taking medication (World Health Organization, Citation2003). The following circumstances should be considered when using insulin: It should be carried safely, with no excessive shaking or exposure to high temperatures. It should not be transported at temperatures below 0 °C. If it will be kept at home for more than two months, it should be stored at the recommended temperature of 2 to 8 °C. Patients should be given clear instructions. Insulin in use should be maintained at room temperature and should never be immersed in water. It is best to use the shortest needles available. Intramuscular injections should not be used in routine care. Excessive slanting of the needle should be avoided. It should be started with pen devices for wasting patients. Needles and syringes should not be reused (Bahendeka et al., Citation2019).

According to our findings, a container filled with moistened sand was the most common technique for handling insulin. Immersing insulin in water after the vial has been opened, on the other hand, poses a significant risk of contamination (Bahendeka et al., Citation2019). It should be kept in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommendations (Siminerio et al., Citation2011). Some patients have also used a refrigerator or their pockets. If it is opened, it can be kept at room temperature. When the patients needed to travel a long distance, a container filled with sand and water has been used to handle it as usual. Also, in reality, reserve insulin should always be kept in the refrigerator (between 2°C and 8°C; Canadian Diabetes Association, Citation2018; Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017; International Diabetic Federation, Citation2006), but never, ever put it in a freezer (International Diabetic Federation, Citation2006). Insulin in use, on the other hand, can be stored at room temperature for up to one month (Canadian Diabetes Association, Citation2018; Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017), in a dark, clean, and secure location. Handle it gently and do not shake it too hard while using it (International Diabetic Federation, Citation2006). It is sensitive to temperature and should be stored “away from sunshine” and “do not freeze” (Heinemann et al., Citation2021; International Diabetic Federation, Citation2006). Insulin that has been frozen, exposed to temperatures above 30 °C, or expired should be discarded (Canadian Diabetes Association, Citation2018). It should be maintained in a proper container while traveling on land; it should never be kept in a car’s glove compartment or left unattended in a locked vehicle. If traveling by air, it should be kept in a secure container in a personal bag or carry-on luggage. Due to the risk of exposure to severe temperatures, it should not be stored in the plane’s baggage hold. It is also a good idea to keep an additional insulin pen or vial on hand in case of any unanticipated circumstances (Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017).

Insulin has been discovered to be more heat-stable in recent investigations because it is still effective in many resource-poor areas with ambient temperatures above the prescribed temperature (Tucker, Citation2021). Surprisingly, insulin has frequently been kept outside of the recommended temperature range (Krämer et al., Citation2020). The stability of an in-use insulin pen was unaffected by temperatures as high as 37 °C or cycling temperatures (Kongmalai et al., Citation2021). Moreover, injecting refrigerated insulin is painful (Toschi, Citation2018). So, it is not recommended to use frozen insulin (United States’ Food and Drug Administration, Citation2018). Frozen insulin does not also have full potency, which results in suboptimal glycemic control (Krämer et al., Citation2020).

The abdomen area, thighs, and upper arms were the most popular injection sites. A multitude of factors, including the availability of a helper and the possibility of injection site problems, have affected the locations chosen. The backs of upper arms, abdomen (around the navel), front and side portions of the thighs, and rear ends (buttocks) are all good places to inject insulin (Learning About Diabetes, Citation2014). The abdominal cavity is easy to access and gives the most rapid and constant absorption (Canadian Diabetes Association, Citation2018; Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017). The upper arm and lateral thigh have a moderate absorption rate. The absorption rate in the buttock area is the slowest. The abdomen and thighs are the two most commonly advised injection sites for adults due to their ease of self-administration. When provided by caregivers, however, the arms and buttocks are favored. Insulin absorption varies depending on the kind of insulin, injection site, skin temperature, and exercise (Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society, Citation2017).

4.1. Practice and policy implications

It is well recognized that proper storage improves medication safety while also reducing the stress and burden of living with diabetes. As more evidence emerges concerning the difficulties of keeping insulin at home, it is imperative to raise awareness about these often-overlooked issues and improve education. Practical advice on how to safely keep insulin at home should also be sought (Krämer et al., Citation2020).

4.2. Implications for future research

There is a need for action research on practical recommendations on how to appropriately store insulin at the household level.

4.3. Limitations

Only those who were receiving treatment at DCSH participated. Those who are receiving treatment at other public and private hospitals were not included. Hence, the finding cannot be generalized.

5. Conclusion

The storage processes as well as injection site preferences were studied in depth. While the abdomen was the most popular injection site, the most common storage method was a jar filled with damp sand.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Author contribution statement

Ewunetie Mekashaw Bayked conceived and designed the study, conducted the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, contributed materials, analysis tools, or data, and wrote the paper.

Mesfin Haile Kahissay and Birhanu Demeke Workneh conceived and designed the data, conducted the study, and analyzed and interpreted the data.

Acknowledgements

All of the study participants deserve our gratitude for their time, voluntary participation, and information sharing. We would also like to express our gratitude to all of the nurses, general practitioners, and physicians that work at DCSH’s diabetes clinic.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ewunetie Mekashaw Bayked

Mesfin Haile Kahissay (PhD) is an assistant professor in social and administrative pharmacy and chair of the Department of Pharmaceutics and Social Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University. Throughout his childhood and schooling, and through his working life, he has lived in a social world where indigenous practices are being used by the people in his immediate community. His academic and research interests grow out of his own real-life experiences, and not simply as the result of his role as a biomedical practitioner. His research interests are issues related to the behavioral, social, anthropological, and economical aspects of pharmaceutical care. Courses in which he has been engaged are under the domain of social and administrative pharmacy, such as behavioral and social aspects of pharmacy, pharmaceutical and medical anthropology, pharmaceutical marketing, pharmacoepidemiology, pharmaceutical supply management, pharmaceutical marketing and policy, and pharmaceutical law and ethics.

References

- Alqurshi, A. (2020). Household storage of pharmaceutical products in Saudi Arabia; A call for utilising smart packaging solutions. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 28(11), 1411–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.09.006

- Altebainawi, A. F., Alrashidi, M. N., Aljbreen, M. K., Aziz, M. M., Alhifany, A. A., Aljofan, M., & Alshammari, T. M. (2020). Association of medication storage with diabetes control: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal: SPJ: the Official Publication of the Saudi Pharmaceutical Society, 28(4), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.02.006

- American Diabetes Association. (2004). Insulin administration. Diabetes Care, 27(1), s106–107. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.2007.S106

- Anderson, R., Doyle, G. R., & McCutcheon, J. A. (2018). 7.4 subcutaneous injections. Thompson Rivers University. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/facultyancillaryresourceforclinicalproceduresforsaferpatient/chapter/7-4/

- Australian Diabetes Educators Association. (2015). Clinical guiding principles for subcutaneous injection technique. Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA). https://www.adea.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/InjectionTechniqueGuidelines_FINAL_Approved_Jan-2020-8.pdf

- Bahendeka, S., Kaushik, R., Swai, A. B., Otieno, F., Bajaj, S., Kalra, S., Bavuma, C. M., & Karigire, C. (2019). EADSG guidelines: insulin storage and optimisation of injection technique in diabetes management. Diabetes Therapy: Research, Treatment and Education of Diabetes and Related Disorders, 10(2), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0574-x

- Baruah, M. P., Kalra, S., Bose, S., & Deka, J. (2017). An audit of insulin usage and insulin injection practices in a large Indian cohort. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 21(3), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijem.IJEM_548_16

- Bayked, E. M., Kahissay, M. H., & Demeke Workneh, B. (2021). Inventory management practices of pharmaceuticals in public health institutions of Dessie city administration, Ethiopia: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Innovare Journal of Health Sciences, 9(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.22159/ijhs.2021.v9i3.42133

- Braune, K., Kraemer, L. A., Weinstein, J., Zayani, A., & Heinemann, L. (2019). Storage conditions of insulin in domestic refrigerators and when carried by patients: often outside recommended temperature range. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 21(5), 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2019.0046

- Calliari, L. E., Cudizio, L., Tschiedel, B., Pedrosa, H. C., Rea, R., Pimazoni-Netto, A., Hirsch, L., & Strauss, K. (2018). Insulin injection technique questionnaire: Results of an international study comparing Brazil, Latin America and World data. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome, 10(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-018-0389-3

- Canadian Diabetes Association. (2018). Getting started with insulin. Diabetes Canada, 4. https://www.diabetes.ca/about-diabetes/diabetes-management/getting-started-with-insulin

- Daniela, R. M. (2020) Determining the sample size in qualitative research. International multidisciplinary scientific conference on the dialogue between sciences & arts, religion & education 4: 181–187.

- Dodgson, J. E. (2019). Reflexivity in qualitative research. Journal of Human Lactation, 35(2), 220–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334419830990

- Drugs.com. (2022) How to Give an Insulin Injection: https://www.drugs.com/cg/how-to-give-an-insulin-injection-ambulatory-care.html

- Frid, A., Hirsch, L., Gaspar, R., Hicks, D., Kreugel, G., Liersch, J., Letondeur, C., Sauvanet, J. P., Tubiana-Rufi, N., & Strauss, K. (2010). New injection recommendations for patients with diabetes. Diabetes & Metabolism, 36(2), S3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1262-3636(10)70002-1

- Gradel, A. K. J., Porsgaard, T., Lykkesfeldt, J., Seested, T., Gram-Nielsen, S., Kristensen, N. R., & Refsgaard, H. H. F. (2018). Factors affecting the absorption of subcutaneously administered insulin: effect on variability. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2018, 120512. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1205121

- Hansen, B., & Matytsina, I. (2011). Insulin administration: Selecting the appropriate needle and individualizing the injection technique. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, 8(10), 1395–1406. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2011.614229

- Heinemann, L., Braune, K., Carter, A., Zayani, A., & Krämer, L. A. (2021). Insulin storage: A critical reappraisal. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 15(1), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296819900258

- Hirsch, L. J., & Strauss, K. W. (2019). The injection technique factor: What you don’t know or teach can make a difference. Clinical Diabetes: a Publication of the American Diabetes Association, 37(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd18-0076

- International Diabetes Federation. (2021) World diabetes day | access to diabetes care: if not now, When? In: International Diabetes Federation: https://worlddiabetesday.org/

- International Diabetic Federation. (2006). Diabetes education training manual for International Diabetes Federation: Africa region Sub-Saharan Africa. International Diabetic Federation (IDF).

- Jafarzadeh, A., Mahboub-Ahari, A., Najafi, M., Yousefi, M., & Dalal, K. (2021). Medicine storage, wastage, and associated determinants among urban households: A systematic review and meta-analysis of household surveys. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11100-4

- Kedogo, E. K. (2015). Impact of insulin storage and administration technique on glycated heamoglobin among adult diabetic patients at Kenyatta national hospital. University of Nairobi.

- Kiger, M. E., & Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher, 42(8), 846–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

- Kituzi, E. E., Karimi, P. N., Nyamu, D. G., & Tirop, L. J. (2016). Effect of insulin storage and administration methods on long term glycaemic control among adult diabetic patients in a Kenyan Referral Hospital. East and Central African Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 19(1–3), 3–9. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ecajps/article/view/177860/167236

- Kongmalai, T., Preechasuk, L., Junnu, S., Manocheewa, S., Srisawat, C., & Sriwijitkamol, A. (2021). The effect of temperature on the stability of In-Use Insulin Pens. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes: Official Journal, German Society of Endocrinology [And] German Diabetes Association, 129(9), 683–688. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1010-5466

- Krämer, L., Vlasenko, I., & Zayani, A. (2020) Storage of Insulin: IDF Europe awareness paper. In, Brussels, Belgium, pp.12. International Diabetes Federation European Region.

- Learning About Diabetes. (2014). How to inject insulin pen. Learning About Diabetes, Inc. https://learningaboutdiabetes.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs-medicine/HowToUseAnInsulinPenEN.pdf

- Lucca, J., Alshayban, D., & Alsulaiman, D. (2019). Storage and disposal practice of unused medication among the Saudi families: An endorsement for best practice. Imam Journal of Applied Sciences, 4(1), 1–6. https://www.e-ijas.org/text.asp?2019/4/1/1/252594

- Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society. (2017). Forum for injection technique Malaysia: recommendations for best practice in injection technique. Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society (MEMS). https://mems.my/forum-for-injection-technique-malasyia-fit-my/

- Mekashaw, E., Demeke, B., & Haile, M. (2022a). Recognition of symptoms, mitigating mechanisms and self-care experiences of type 2 diabetes patients receiving insulin treatment in North-East Ethiopia [version 3; peer review: 2 approved]. Emerald Open Research, 3, 14. https://doi.org/10.35241/emeraldopenres.14312.3

- Mekashaw, E., Kahissay, M. H., & Workneh, B. D. (2022b). Patients’ perceptions, associations, and justifications for the causes of diabetes in North-East Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 16(5), 102502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102502

- Netere, A. K., Ashete, E., Gebreyohannes, E. A., & Belachew, S. A. (2020). Evaluations of knowledge, skills and practices of insulin storage and injection handling techniques of diabetic patients in Ethiopian primary hospitals. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1537. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09622-4

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Oosthuizen, J. (2019) Tips for injecting insulin. In: Diabetes South Africa: https://www.diabetessa.org.za/tips-for-injecting-insulin/

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Petrie, P. (2015). Storing Your Diabetes Supplies. Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital.

- Shah, R. B., Patel, M., Maahs, D. M., & Shah, V. (2016). Insulin delivery methods: Past, present and future. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-973X.176456

- Siminerio, L., Kulkarni, K., Meece, J., Williams, A., Cypress, M., Haas, L., Pearson, T., Rodbard, H., & Lavernia, F. (2011). Strategies for insulin injection therapy in diabetes self-management. American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE), 37(6), 1–10. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/legacy-docs/_resources/pdf/research/aade_meded.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

- Toschi, E. (2018). Safe and effective use of insulin requires proper storage. Harvard Medical College. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/safe-and-effective-use-of-insulin-requires-proper-storage-2018120415486

- Tucker, M. E. (2021). Contrary to Popular Belief, Insulin Can Be Stored Outside Fridge. WebMD LLC. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/946551

- United States’ Food and Drug Administration. (2018) Information Regarding Insulin Storage and Switching Between Products in an Emergency: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/emergency-preparedness-drugs/information-regarding-insulin-storage-and-switching-between-products-emergency

- World Health Organization. (2003). Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action.