Abstract

: Alcohol use disorders are a major contributor to morbidity and mortality across the globe. Binge drinking and suicide have a high prevalence in northern latitudes, including Canada, Alaska, Greenland, and northern Europe. Many factors are associated with alcohol misuse and suicide in these northern regions such as climate, geographic location, history of the population, which in Canada includes colonisation-related harms such as the introduction of alcohol and systematic suppression of native cultures, on-going psychosocial stressors, and governmental policies. Due to the high prevalence of alcohol misuse and suicide in the studied population, the authors introduced contextually relevant Brief Intervention (BI) into the ER and ambulatory care settings as a harm-reduction measure. The impact of BI on binge drinking and suicide is discussed. The co-ordination of BI with other harm-reduction strategies in the region include suicide awareness and intervention training, efforts by provincial and federal governmental agencies using special teams to limit the social and psychological impact of recent suicides in communities, the return of AA groups after a ten-year hiatus, and importantly the establishment of native healing programmes.

1. Introduction

The present work illustrates how a crisis in chronic and binge drinking in Indigenous communities of western Hudson Bay was managed effectively in spite of unique and significant challenges that working in the north can present. These challenges included having no AA in the region for over ten years, the general hospital having no dedicated detox beds, the nearest detox and rehabilitation facility (Smooth Rock Falls) being over 350 km away by train and bus, and native healing programmes being not yet operational. As is well documented, northern countries and regions such as Canada, Alaska, Russia, parts of Scandinavia, and Scotland all show a striking correlation between binge drinking and suicide in comparison to more southern latitudes, often within the same country (Razvodovsky, Citation2011; Staff, Citation2016; Ventura‐Cots et al., Citation2019). While geographic isolation and remarkably reduced annual sunlight hours contribute to the association between binge drinking and suicide, other factors also influence Canadian populations in these northern latitudes such as low education, poorly self-evaluated health and well-being, and employment status (Cuell, 2018; Razvodovsky, Citation2011; Staff, Citation2016). However, the Indigenous populations who inhabit these regions are particularly impacted by these psychosocial stressors, many of which are associated with the long-term impacts of colonisation, including the introduction of the residential school system, and systematic suppression of native languages and culture (Danto & Walsh, Citation2017; Cuell, 2018; Mehl-Madrona, Citation2016; Wenger-Nabigon, Citation2010).

The official status of the native populations in Western Hudson Bay (Mushkegowuk Territory) was outlined in Treaty 9 signed in 1905, through which government policies evolved that undermined the Indigenous population as a legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entity (Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Citation2021). One of the key influences in undermining native dignity was the residential school system introduced into the Treaty 9 Territory (and across most of Canada) in the last quarter of the 19th century. These schools separated very young children from their families for long periods of time, severing their links to their culture and their identity. Indeed, the extent of this legacy on the Indigenous populations in these regions continues to take a massive toll in the form of trans-generational trauma, lack of equal opportunity, and a loss of cultural identity and practices, further contributing to a vicious cycle of psychosocial distress (Danto & Walsh, Citation2017; Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Citation2021; Kahn, Citation2008; Mehl-Madrona, Citation2016; Wenger-Nabigon, Citation2010).

Towards alleviating injustices in healthcare, The Truth and Reconciliation Report has called for the collaboration of western medicine and native healing practices (Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Citation2021). It is in this collaborative spirit that we attacked the complex issue of binge drinking and suicide in the Indigenous population in the Mushkegowuk Territory from 2011 to 2016. What follows is a pilot study detailing a first attempt at decreasing binge drinking and its associated behaviours (including suicide) through collaborative efforts that drew on the methods of Brief Intervention (BI) and native healing programmes.

The introduction of Brief Intervention (BI) was our contribution to reducing binge drinking episodes that resulted in severe intoxication. As the association between alcohol and suicide in Indigenous populations is all-too common and alarming (Kahn, Citation2008; Mehl-Madrona, Citation2016), we implemented BI with the hope of effecting a significant reduction in future suicide attempts by treating a proximal cause of these attempts, namely acute and severe alcohol intoxication. Our own Emergency Room (ER) statistics reflect the severity of the situation, showing that alcohol or alcohol-related diagnoses accounted for 40% of the Emergency Room (ER) census on weekends, with many patients having attempted suicide in association with drinking (WAHA, 2011–2013). Government agencies were proposing reductions in funding for ambulatory care unless the hospital initiated remedial measures. Under the threat of these proposed reductions, the first measure we introduced into ambulatory care centres was BI.

BI has been shown to be an effective initial treatment for alcohol use disorders (McQueen et al., Citation2011). Indeed, an exemplary study was the work of Cobain and colleagues in the UK (Cobain et al., Citation2011), which demonstrated that BI can be effective for combating the deleterious effects of chronic alcohol consumption. Their study enrolled ER-patients who were non-treatment seeking and had multiple co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, GI issues, and chronic kidney failure. They concluded that BI had a statistically significant impact on drinking behaviours in the test ER-group compared to the controls. They did not comment on binge drinking, however. Thus, we hypothesized that BI might be an effective treatment for binge drinking in western Hudson Bay. Therefore, we introduced it into the region in 2012. We extended the work of Cobain et al. but with cultural adaptations made for climate, geography, language, and population movement (see limitations section).

Yet the introduction of BI into the region was only a first step. Important to the sustained reduction in alcohol-related suicide was the role of native healing programmes, which contributed to the decrease in violent behaviours associated with binge drinking, including suicide attempts. The efficacy of these native healing methods has been demonstrated in the first nations communities of northern Saskatchewan, where interventional counternarratives to suicide and other violent behaviours—led by community elders—have proven invaluable towards restoring personal and cultural integrity, which, in turn, has been associated with a remarkable decrease in the incidence of these behaviours. (Mehl-Madrona, Citation2016)Footnote1 These culturally specific counternarratives of the native communities of the Mushkegowuk Territory played an important role in reducing and sustaining the incidence of attempted suicides and deaths by suicide associated with acute alcohol intoxication and became operational in our region in September 2013. Located directly across the hall from the hospital-ER, the centre for native healing was easily accessible to those who wanted more support for their alcohol use disorder (AUD). If the ER-physician or AUD-nurse needed to follow up with the patient(s), they could easily do so (with the patient’s consent) by simply walking across the hall and talking to the patient or the conductor. In this way, a close-knit collaboration between western medicine and native healing was implemented in the region.

2. Materials and methods

Constructs and Design of the Brief Intervention Study

Starting in 2011, the PI worked closely with the director of mental health and the chief of staff at Weeneebayko General Hospital (WGH) on the design of the BI project for the ER. At that time, the chief of staff was trying to establish native healing programmes at the hospital, which would require another two years. After review and approval of the BI proposal by the WGH IRB—which included band input—final approval was given by a division of the Queens University IRB that deals with northern and native affairs.

Like the Cobain study, our BI study was a prospective cohort-controlled pilot study that recruited 100 patients at the WGH ER (the test site) to receive BI. Another 100 patients were recruited at the mainland free-standing ER (the control site, 3 km away by water or ice road), all of whom agreed to participate in the study but who did not receive BI. Patients for our study were recruited at both sites between September 2012 and September 2013. Site differences were minimal as the same professional staff rotated regularly between both sites. The ER physical plants were similar and the policies and procedures under Weeneebayko Health Authority were identical. Patients were identified by a triage nurse trained in AUD and referred to the medical personnel on duty if alcohol appeared to have contributed directly or indirectly to the ER visit. Exclusionary criteria were IV drug use, inability to give informed consent, or under the age of 18. Patients received no financial compensation for study participation. Patients (matched for demographics and comorbidities) were identified at both sites as abusing alcohol or binge drinkers using the Modified Screening Questionnaire (M-SASQ) (Table ). After screening, participants were then interviewed by professionals trained in alcohol use disorders. At the test site, patients then received BI and were discharged thereafter. For the test group, BI was delivered by a physician, a nurse trained in AUD, or social worker using motivational interviewing and a CAMH pamphlet on alcohol ((https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/guides-and-publications/research-reports-and-books), which the patients took home. Importantly, the interviewers always attempted to explore the links between the patient’s alcohol consumption and their ER-attendance near the end of each 20-minute session. Items of particular importance in the north were discussed and highlighted, e.g., not drinking outside alone at—40 C, not driving a snow mobile whilst intoxicated, and avoiding all alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Patients consented to follow-up at six-month intervals after having received BI. At the mainland control, ER patients received medical care but did not receive BI. Participants at this site were also followed up at six-month intervals. No breathalyzer or blood alcohol levels (BAC) were drawn as part of the BI-study. Due to cost constraints at the time of this study, BAC was drawn only on WGH ER patients when the results were likely to impact immediate medical management.

Table 1. Effects of BI after six months

Table 2. MSASQ-Questionnaire

When the follow-up telephone interviews were attempted with all 200 recruited patients six- months after their original evaluations, 54 of the 100 patients who had received BI could not be contacted, and in the control group 56 of the 100 patients could not be contacted. Thus, these patients were considered lost to follow-up. Patients who remained in the study were followed up by the professional staff at six-month intervals for an additional three years using the M-SASQ and clinical assessment of drinking behaviours in order to assess how long the effects of BI persisted and whether relapse to binge drinking had occurred. None of these patients died by suicide.

2.1. Deaths by suicide and suicide attempts in Hudson Bay

When an individual dies by suicide in western Hudson Bay, the deceased must be evaluated by the coroner, the police, and the ER physician at the Weeneebayko General Hospital. This is followed by an autopsy which includes a single post-mortem BAC. The information from all sources, including relatives and bystanders, is all summarized as part of the final hospital record.Footnote2

Data for the number of attempted suicides between 2010 and 2016 were collected from ER-visit records listing the attempt as the reason for the visit or the principal diagnosis. For all deaths by suicide occurring in the coastal communities for the period 2010–2016, autopsy reports, methods of suicide, toxicology, blood alcohol levels, police and bystander reports, and administrative records were reviewed. None of the individuals who died by suicide had received BI. The DSM IV/V does not specifically address binge drinking and the NIAAA definition of binge drinking is very similar to the more intensive levels of drinking as screened for in the M-SASQ.

3. Results

The goal of this BI pilot study was to determine whether BI would be an effective tool in our studied Indigenous population in order to reduce harms associated with alcohol misuse and to expedite referral to treatment. The results in our studied population are similar to the Cobain study in the U.K. Our BI group showed a reduction in alcohol consumption overall (see, Table ). Table describes the 46 test patients who completed the study. At six- months, 21 patients reported total abstinence, 12 a decrease in number of drinking days, 13 a decrease in drinks per day. Within the total of 46 patients, there were 14 who were binge drinkers as determined by both the M-SASQ and interview, of which 4 reported total abstinence. This resulted in a 30.4% reduction in binge drinking, which is more than half the natural recovery rate of 14% in our groups. However, the chi-square test of independence performed to examine the relation between the BI group (N = 46) and the control group (N = 42) on three of the variables (total abstinence, decrease in number of drinks per day, and decrease in number of drinking days) showed no statistically significant difference between the groups χ2 (2, N = 88) = 1.41, p = .49 at p < .10. The corresponding Cohen’s W = .13, which indicates a small effect size.

The control group showed no decrease in drinking behaviours or consumption beyond the natural recovery rate of 14%. One patient died of alcohol poisoning. In the test group, BI was well received over all with many patients commenting at follow-up how it had enabled them to gain insight into their drinking problems and to better control their consumption. For some, BI helped them to actively consider additional support services for long-term recovery such as AA or native healing programmes that became operational in the region in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

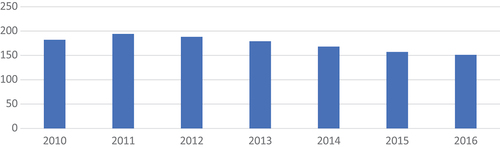

Figure shows the attempted alcohol-related suicides for the entire coastal population for 2010 (the year before the study began) through 2016. After the peak in 2011, a downward trend continued until the end of the BI follow-up period in 2016. AA and native healing programmes became available in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Figure 1. At empted suicides from 2010 to 2016.

3.1. Effect on suicide

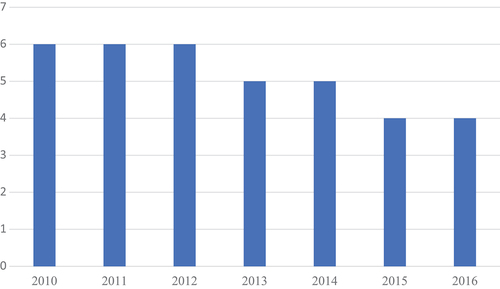

Following the introduction of BI and native healing programmes, a reduction in attempted suicides and deaths by suicide associated with alcohol abuse was observed. Moreover, this downward trend was sustained over significant periods of time and was independent of both medical comorbidities and baseline levels of dependence (A. J. Hill & Banayan, Citation2016). Figure shows deaths by suicide in the same period (2010–2016). There was a gradual, sustained decline in adult suicides associated with alcohol misuse. This effect was initially observed in 2012–2013 and was sustained through 2016; this effort continued with AA and native healing programmes being introduced into the region.

Figure 2. Death by suicide from 2010 to 2016.

Programmes based on social interactions are known to be over 30% effective in preventing relapse to alcohol (AA, 2020). Nonetheless, a resolute claim for the efficacy of BI on binge drinking and suicide would be hasty. Thus, we conclude that while the observed reduction in binge drinking after patient had received BI and/or a support programme was associated with a decline in attempted suicide and death by suicide, further studies are needed to demonstrate the direct effect of these methods on suicide reduction.

4. Discussion

4.1. Alcohol abuse and geographic latitude

Geography and climate are positively correlated with heavy or binge drinking in more northern latitudes. In Canada, the Northwest Territories (NWT) leads the way with 32.7% of the population reporting heavy drinking, followed by the Yukon (YT) at 28.7%, and Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) at 25%. This picture becomes all the more striking when compared with the suicide rates of more southern latitudes. For instance, the Yukon’s suicide rate is at 13/100k, NWT at 12.4/100k, and NL at 10.5/100k, whereas the rate for southern Ontario is 8.5/100k while 11.5/100k is for Canada as a whole (www.150.statcan.gc.ca/). The normalised rate of adult suicide for the coastal communities of western Hudson Bay (total population approximately 10,000) is 60 per hundred-thousand or seven times the rate reported for southern Ontario, and over five times the rate for Canada. However, data from Statistics Canada may not accurately reflect the demographics of people living on reserves and Crown lands.Footnote3 Reporting our data is therefore a small but important step towards solving the suicide crisis in the Indigenous population of western Hudson Bay.

4.2. Reducing binge drinking through BI and native healing programmes

In 2012, no beds dedicated to alcohol detoxification or rehabilitation were available throughout the area served by the Weeneebayko Health Authority. The nearest detoxification and treatment facility (Smooth Rock Falls) was over 350 km away by train and bus ride. AA had been absent for over ten years until it was reinstated in 2013. Starting in 2012, our introduction of BI into the acute-care settings was the only harm reduction strategy targeting alcohol consumption and dependence, which we deployed as a first-line treatment for binge drinking rather than in-patient detoxification or rehabilitation. We are therefore inclined to suggest this method (BI) unless there are indications of comorbid active medical issues or active psychiatric diagnoses.

Our brief intervention pilot study (2012–2013) showed results in our Indigenous population similar to the Cobain UK-study but with the additional positive effect on binge drinking reduction. Thus, BI appeared to be efficacious in the studied population, so the study was stopped at the end of 2013, and BI was added to the list of treatment modalities for alcohol available to coastal communities served by the Weeneebayko Health Authority.

4.3. Follow-Up

The studied BI patients were followed for an additional three years with most chronic drinkers reporting a sustained effect of reduced alcohol consumption. However, binge drinkers at the end of follow-up reported a relapse rate of 30%. During the year of the BI study, we began to analyse the available data for attempted suicide and death by suicide both before and after the period of the study relative to the interventions now in place (2012–2013).

In November of 2013, our efforts were augmented by the introduction of native healing programmes. By 2015, native healing programmes had evolved in scope, availability, and appeal. Oriented around the Medicine Wheel (Danto & Walsh, Citation2017; Wenger-Nabigon, Citation2010), programmes had become more easily accessible that addressed alcohol issues and dependency for individuals as well as families. For example, several native healing alcohol outreach groups were made available at the Weeneebayko Hospital and the coastal communities several times a week. During these sessions, participants of these native healing groups at WGH are seated in a circle and led by a conductor who introduces warm rocks followed by revered items such as sage, cedar, and tobacco. This is usually followed by chanting, after which the conductor goes around the circle sequentially to ask each participant to speak about their concerns or issues. As the sessions progress, the conductor helps to maintain group focus and to encourage a healing atmosphere. The sessions usually last about two hours. The conductors are fully trained and certified in native healing practices and are also trained to identify medical and psychiatric issues that could have a negative impact on individual and/or group progress. Participants who appear to have such issues are referred to the appropriate hospital services by the conductors, which are located less than 20 metres from the native healing room.

Starting in 2013–14, we suggested to all ER recipients of BI that follow-up with a native healing programme or AA-group would be desirable. In the same period, the Reaching Out Suicide Education programme (R.O.S.E) (staffed with trained health workers reachable via telephone), as well as additional contagion containment strategies were introduced through community and school programmes supported by the federal and the provincial governments. The spring of 2014 saw the introduction of Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), which is a two-day workshop teaching effective intervention skills towards building suicide prevention networks in the community. Following the lead of the success of the ASIST model in Nunavut communities in Repulse Bay in reducing suicide (Eggertson, Citation2013), the ASIST personnel in the Mushkegowuk Territory worked closely with band leaders, native healing conductors, and local law enforcement to adapt the ASIST methodology to the needs of the local communities. Furthermore, a shorter training—safeTALK—taught intervention skills aimed at building suicide prevention networks throughout the communities. SafeTALK trainers also worked closely with band leaders and native healing conductors in order to ensure culturally appropriate context and content. Several of the trainers were native and had been trained in these techniques through an initiative of the Nishnawabe Aski Nation.

As our results indicate, our united efforts against binge drinking in the region suggest yet do not unequivocally demonstrate a direct effect on adult suicide. Thus, while only a first step, this was an important beginning towards ameliorating a major problem afflicting an Indigenous population in a northern latitude historically beleaguered with demeaning governmental policies (Cuell, 2018; Danto & Walsh, Citation2017; Razvodovsky, Citation2011; Staff, Citation2016; Statistics Canada, 2014; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2016; Ventura‐Cots et al., Citation2019; Wenger-Nabigon, Citation2010).

4.4. Limitations

The number of patients lost to follow-up and the low follow-up rate was a concern. However, this had been anticipated as patients often relied on a neighbour’s phone and there was limited or no mobile phone service in the area. In addition, patients often moved between communities, visiting friends and relatives, or temporarily re-located to another community for work. Some are out of western Hudson Bay for further education, specialized medical care, new employment, or vacation. The low follow-up rate meant that we could not include them in the final statistical analyses of either the study or the control group. However, the patients who answered their first follow-up call continued to respond to follow-up calls for the duration of the study, affording us at least a first look at the effectiveness of BI on the variables measured in both groups. Lastly, this study was conducted entirely in the Mushkegowuk Territory and may therefore not be applicable to other Canadian Indigenous populations.

4.5. Recommendations for future research and conclusions

This research should be followed up by a randomized controlled study of BI in patients with AUD. This would require 70–80% follow-up in order to allow more comparison to other studies. In addition, an important concern of the authors is that future researchers should build on our suicide data and continue to develop treatment programmes that are compatible with native healing practices as well as other support services that will help to lower alcohol consumption, suicidal behaviours, and deaths by suicide in western Hudson Bay.

We emphasize that northern latitudes and climates are associated with increased alcohol consumption which, in turn, contributes to suicide and the burden of disease (AAF) in these regions. In addition, Canada’s Indigenous northern populations have unique psychosocial stressors that contribute to drinking behaviours and suicide. Thus, active collaboration between Western medicine and native healing programmes can result in approaches and treatments that are culturally relevant and therefore likely to be more effective in reducing alcohol consumption and suicide while supporting personal and communal well-being.

Finally, when governments and institutions assist in the design and development of alcohol programmes and policies for northern regions, it is imperative to understand and to appreciate the unique and complex challenges these regions present to health-care providers as well as patients. This imperative becomes all the more pressing when working with the Indigenous peoples in these regions.

Lastly, the authors wish to thank all the patients who consented to participate and ultimately inspired us to continue the study for an additional two years.

Ethics approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients before being included in the study.

Data availability

Due to ethical restrictions, supporting data are not available.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

The authors acknowledge the support of the Institutional Review Boards of Weeneebayko General Hospital and Queens University as well as the local band councils. All of these entities remained in an oversight capacity throughout the period of our study. The WGH IRB and band councils requested that in any subsequent reports, the specific communities NOT be identified, and patient privacy be scrupulously maintained.

Positionality of the authors

The PI for this study and had experience working with Indigenous populations in northern Canada prior to this study. He is board certified in Addiction Medicine and a specialist in alcohol use disorders at the University of Massachusetts Medical School Worcester. He was recruited by Weeneebayko General Hospital (WGH) and Health Authority to work at the hospital as a senior staff physician and to develop programmes to mitigate chronic and binge drinking, which accounted for nearly 40% of ER visits on weekends. The PI was born and raised in southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada and was educated at eastern Canadian universities in the 1960ʹs and 70ʹs. The corresponding author was born in southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada and was raised in Boston, Massachusetts. His higher education was completed in Canada, Wales, and Germany. Both the PI and the corresponding author are listed in the US Census as Caucasian and American Indian. The third author is a native of England and completed her higher education there in the 1970ʹs.

While all three authors were outsiders with respect to positionality, they were well received and respected by the island and mainland communities.

This study involved all six of the coastal communities of Western Hudson Bay by virtue of people from those communities visiting the WGH ER for medical care while they were on the island. The vast majority of the patients studied belonged to the Moose Cree Nation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Arnold Hill, Patricia Benson, and Richard Hill. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Arnold Hill and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. In addition, Cheryl Fry contributed to the design of the brief intervention, trained the ER nurses, social workers, and addiction counsellors to effectively deliver the BI to patients. Charlene Banyan was the physician champion in the ER assisted by other staff physicians. The authors wish to thank the more than 30 Family Medicine residents who participated at the ambulatory care sites during the period of the study. The authors would also like to thank Elizabeth Bojarski O’Conner for critically assessing the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See also Wenger-Nabigon (Citation2010) for the indispensability of native approaches to personal and community wellness across a variety of communities. Danto & Walsh (Citation2017) show the effectiveness of these approaches for the communities of the Mushkegowuk Territory.

2. These records were accessible to the PI as the senior staff physician with prior approval of the chief of staff and the hospital IRB which included band membership. These data are replicable if there were cause to do so.

3. Their data are reported directly to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Release of these data to other agencies almost always requires band approval The data in this report are unaltered by any agency.

References

- Cobain, K., Owens, L., Kolamunnage-Dona, R., Fitzgerald, R., Gilmore, I., & Pirmohamed, M. (2011). Brief interventions in dependent drinkers: A comparative prospective analysis in two hospitals. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 46(4), 434–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agr044

- Danto, D., & Walsh, R. (2017). Mental health perceptions and practices of a Cree community in Northern Ontario: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(4), 725–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9791-6

- Eggertson, L. (2013). Suicide prevention training saves lives in Nunavut. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(15), 1306–1307. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4595

- Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. (2021, June 11). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Retrieved August 31, 2022, from https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525

- Hill, A. J., & Banayan, C. (2016). Suicide & harm reduction in aboriginal communities, Hudson Bay, Northern Canada. The Canadian Journal of Addiction Medicine, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1097/02024458-201602000-00026

- Kahn, S. (2008). Aboriginal Mental Health: The Statistical Reality. Aboriginal People | Here to Help. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/visions/aboriginal-people-vol5

- McQueen, J., Howe, T. E., Allan, L., Mains, D., & Hardy, V. (2011). Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to General Hospital wards. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd005191.pub3

- Mehl-Madrona, L. (2016). Indigenous knowledge approach to successful psychotherapies with aboriginal suicide attempters. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(11), 696–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716659247

- Ng, R. (2018, September 21). The end: A study of suicide in Canada. CSFJ. Retrieved August 31, 2022, from https://csfjournal.com/volume-1-issue-1/theend

- Razvodovsky, Y. E. (2011). The effects of alcohol on suicide rate in Russia. Suicidology Online, 2(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0358.1000112

- Staff, H. S. (2016, June 16). Scotland ‘worst in World’ for binge drink damage. HeraldScotland. Retrieved August 31, 2022, from https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/14560937.scotland-worst-world-binge-drink-damage/

- Ventura‐Cots, M., Watts, A. E., Cruz‐Lemini, M., Shah, N. D., Ndugga, N., McCann, P., Barritt, A. S., Jain, A., Ravi, S., Fernandez‐Carrillo, C., Abraldes, J. G., Altamirano, J., & Bataller, R. (2019). Colder weather and fewer sunlight hours increase alcohol consumption and alcoholic cirrhosis worldwide. Hepatology, 69(5), 1916–1930. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30315

- Wenger-Nabigon, A. (2010, November 1). The Cree Medicine Wheel as an organizing paradigm of theories of human development. LU. Retrieved August 31, 2022, from https://zone.biblio.laurentian.ca/handle/10219/387