Abstract

Despite collaborative efforts by the government and the private sector in the provision of health facilities in Ghana, a substantial proportion of communities in rural Ghana still have poor access to primary health care. Employing a case study research design, this study presents an overview of the geographic distribution of healthcare facilities in Kpandai District and access to primary health care. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted with randomly selected households, opinion leaders, healthcare and in-charges of health facilities to ascertain their perception of accessibility to health services. Geographic Information System (GIS) (ArcMap) was used to model the spatial distribution of health facilities. Spatially, 139 communities representing 50.5% of the communities are not accessible health facilities per World Health Organization and Ghana Health Service Survive distance threshold to health centers and Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), and hospitals, respectively. Ideally, this implies that the majority of the population have to travel for more than 5 km to access health care services. This study found that the poor spatial distribution of health facilities has negative implications on access to primary health care in the district. Poor conditions of roads were a major barrier to the household’s accessibility to district hospitals. In addition to this, the availability, affordability, adequacy and acceptability which are major determinants of access to primary health care delivery were found to be fairly good. These findings have implications for the realization of the United Nations’ health-related Sustainable Development Goals.

1 Introduction

Health is a fundamental human right and a major social and political concern around the world. In the 1970s, it was recognized that poor health and poverty were interdependent (Peters et al., Citation2008). In this regard, the governments of developing countries have adopted the “Health for All” strategy enhanced by the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration (Hall & Taylor, Citation2003). Despite the enthusiastic efforts of the government and the enormous political support from the international community to improve health, many people in developing countries have poor access to medical services and tend to abandon medical care (Atuoye et al., Citation2015; O’Donnell, Citation2007; Peters et al., Citation2008). The problem of access to health care in developing countries arises in two ways. On the supply side, the provision of medical facilities, and where the facilities are provided, high quality and effective services from these facilities may be lacking due to lack of resources (Phommachanh et al., Citation2019). On the demand side, people may not have access to medical services that will benefit them (Kosny & MacEachen, Citation2010). In reality, these two aspects are clearly related.

The primary health care system, which is designed as the first contact for individuals within the community, is based on practical, scientifically proven and socially acceptable methods and techniques, and is available to everyone (Wallerstein & Duran, Citation2010). In 1978, a concerned group of local families and professionals founded the community family as they were worried about the absence of community-based options for nursing home care. In developing countries, the primary health system was seen as a way to achieve optimal health care for the population (Chatora & Tumusime, Citation2004).

Accessibility, in this context, includes the geographical distance between the origin and the destination, and the distance as the time required to reach the nearest medical facility (Agbenyo et al., Citation2017). Levesque et al. (Citation2013) also describe access to health care as the ability to identify health needs, use health services, achieve, receive, or use health services and actually meet service needs.

Improving accessibility of health care facilities is an important part of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, especially target 8: achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all: Health and development are so closely linked that governments and various development partners need to invest resources in the health sector. The United Nations SDG3, target 8 seeks to achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

Globally, rural populations make up almost 50% of the total population, with available data of 3.41 billion in rural areas and 3.42 billion in urban areas (Pillay & Maharaj, Citation2013). The situation in Ghana is similar, with 49.1% of the population living in rural areas (GSS, Citation2012). To achieve this by 2030, there is a need to focus on the countries and regions with the lowest healthcare accessibility rates. Developing countries and rural areas have been identified as such locations (Pillay & Maharaj, Citation2013).

In addition, poor access to medical services in underprivileged and rural areas causes the poor to suffer from the cost of horrific illness in two respects: the cost of access to services and the loss of production days (Mobaraki et al., Citation2013). Lu et al. (Citation2014) suggested that inadequate medical facilities, long travel time, lack of effective and efficient transportation systems, and inadequate health workers are major barriers to accessing medical services in rural communities. Further, Wagstaff et al. (Citation2004) identified similar factors that impede child health among poor people, especially rural residents, and as a result, they have affected the mortality gap between rural and urban areas. This is even worse for rural residents who have to cross rivers to access medical services. (Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. Citation2010)

In 2018, Ghana’s healthcare spending accounted for 3.54% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Ghana’s health care costs as a percentage of GDP have fluctuated significantly in recent years but have been on a downward trend from 2004 to 2018, reaching only 3.5% in 2018 (World Health Organization, Citation2019). In rural Ghana, the condition of the road between the housing unit and the medical facility is important for access to medical services. According to Atuoye et al. (Citation2015) and Peters et al. (Citation2008) good transportation systems, often rare in rural Ghana, which not only determine access to medical care for people but also provide medicines and other relief supplies to medical facilities. (Atuoye et al., Citation2015; Peters et al., Citation2008)

Accessibility of primary health care in a broader sense encapsulates five dimensions: availability, physical location, affordability, adequacy and acceptability (O’Donnell, Citation2007; Peters et al., Citation2008). It is imperative to note that ongoing discourse on access to primary health care largely focuses on either one or two of the four dimensions of accessibility. For instance, Dos Anjos Luis and Cabral (Citation2016) focused on the geographic accessibility to primary health care facilities in Mozambique, Mobley et al. (Citation2006) concentrated on spatial analysis of elderly access to primary care services in USA, Asaah and Ussiph (Citation2017) emphasised on optimizing access to primary health care services in rural communities in Atwima Mponua District of Ghana, Arcury et al. (Citation2005) also looked at the effects of geography and spatial behaviour on health care utilization among the residents of rural areas, and Comber et al. (Citation2011) focused on the spatial analysis of variations in health access: linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions in the UK. Studies that focus on all the five dimensions of access to primary health delivery are lacking in the sub-Saharan African context and Ghana in particular. To contribute to addressing this knowledge gap that has emerged, this study discusses access to primary health care delivery from all the five dimensions of access to primary health care delivery in rural communities. Such an understanding may have implications for the realization of the United Nations’ health-related Sustainable Development Goals. The study particularly analyses the spatial distribution of medical facilities in the Kpandai area and their impact on rural residence availability, affordability, and acceptance of basic medical care.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

Kpandai District is one of the 14 administrative districts in the Northern Region of Ghana after the delineation of new regions. The district shares boundaries with East Gonja to the west, Nanumba South to the north, Nkwanta North and Nkwanta South to the East and Krachi-Nchumbrum to the south with 8°28′ 7.86՛՛N and 0°00′ 40.57՛՛E absolutely. The district was created in 2008 by carving out an area of what was previously East Gonja District. The district is largely rural, with approximately 90% of the population engaged in local agriculture. As of the 2010 census, the district population was 108,816 with 54,997 males and 53,819 females and 137,249 as the estimated population for 2020. The total land area is 1,772 km2 (684 sq. mi), and the district is divided into three sections: the western part, the eastern part and the areas along the Kete-Krachi Yendi main road, and the districts host about 275 communities which are sparsely distributed due to the farming activities they do either in the western, eastern and those along the main road of Kete-Krachi Yendi route. The reason for choosing Kpandai district for the study is that on the October 2017, the District Chief Executive of the district indicated that access to primary health is one of the major problems confronting the district (Nankwe, Citation2017).

2.2 Research design

Due to the nature of the research and the purpose of the study, an exploratory research design was employed to explore accessibility of primary health care from the five dimensions: availability, acceptability, affordability, adequacy, and accessibility. The case study method under the exploratory design was employed to examine the spatial distribution of healthcare facilities and its effects on access to primary healthcare in rural communities in the Kpandai District, Ghana. This type of research design was used to gain an in-depth and better understanding of access to primary health care in rural-dominated communities. This research design is the most appropriate for this study because it helps gain a concrete, contextual, and in-depth understanding of accessibility to health care (Creswell, Citation2014).

2.3 Data collection procedure

The data were obtained from Google Earth, Google Maps, GPS device (fieldwork), key informants interviews and the resident’s focus group discussion. The GPS software is used to pick coordinates for the various facilities and communities. The GPS coordinates obtained from the various health facilities were entered on an Excel spreadsheet and save (Guagliardo, Citation2004, GSS, Citation2012) in CSV-comma delimited format. Then convert them into X and Y coordinates with the use of Geographic Information System (GIS) ArcMap 10.1 to overlay the data collected from the field to form maps of the study area. The features derived from the above processes are the boundaries of the area, the health care facilities, and road networks.

Data on characteristics of facilities and health personnel were also solicited from the district health directorate and residents of the study communities. The respondents for the key informants’ interview were the Head of the District Health Directorate, in-charges of health facilities, chiefs, and assembly members (see ).

Table 1. Sample units and the number of key informants interviewed

These people were purposively selected because they have in-depth knowledge as far as the subject matter is concerned. Focused group discussion with residents of the Kpandai District was conducted to solicit data from the respondents on the physical location, availability, affordability and acceptability of primary healthcare in the district. The district has been divided into five sub-districts: Kpandai, Ekumdi, Sabonjida/Jambui, Kitare and Bladjai. Three communities were randomly selected from each of the five sub-districts for the Focus Group Discussion (FGD). In total, 30 focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted in 15 selected communities. Out of the 30 FGDs, 15 were for the male group and 15 were for the female group. The number of participants who were selected for the focus group discussion was inspired by the work of Manoranjitham et al. (Citation2007). The authors maintained that the optimal number of participants for focus group discussion is between eight and ten. The study therefore considered nine members for each of the groups (men and women). Men and women who are natives of the communities and have lived there for not less than five (5) years were engaged in focus group discussions. Individuals who participated in the focus group discussions were selected randomly. An interview guide was developed for the focus group discussion and key informants’ interview. Table presents the number of respondents who were engaged in the men and women focus group discussion sessions. Consent (written and oral) was sought from the participants. Participants were further assured of strict confidentiality of the information they provided. Participation in the study was declared as voluntary. Rigor/trustworthiness was ensured by applying these strategies: 1) both the interviews and focus group discussions with the participants lasted for a longer period of time (approximately 90 mins). We did pilot testing of the interview and focus group discussion. The interviews and focus group discussions with the participants ended at a point of saturation (Forero et al., Citation2018). The discussion was done by someone who was more knowledgeable about the issue under investigation to ensure a better understanding of the issue by the study participants. The moderator’s function was to facilitate the group discussion rather than lead the discussion. The interviews and FDGs were conducted in “konbkomba, Nawuri and Nchumbru” (the local dialect of the study participants), while discussions with health providers were carried out in English. Interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent from the study participants, and handwritten field notes were made.

Table 2. Respondents and sample size for the focus group discussion

2.4 Data analysis

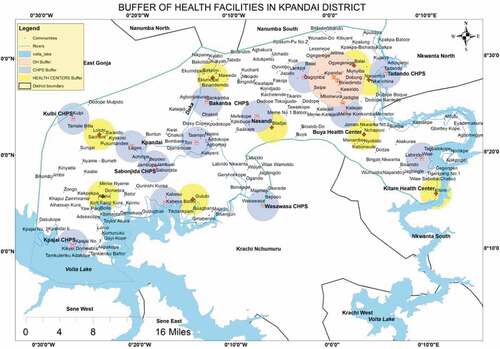

According to Ghana Health Service and World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended 5 km distance to the nearest hospital and 3 km to the nearest CHP or Health Center (Ashiagbor et al., Citation2020a). These distances were used as the reference distance for the buffer analysis. A buffer analysis was conducted on the various health care facilities within the district with separate analysis on the CHPS, Health Centers and the District Hospitals with a distance range of 3 km and 5 km for all the facilities on the maps of reference. The World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended 5 km distance to the nearest hospital (Ashiagbor et al., Citation2020a) and 3 km to the nearest CHP or Health Center was used as the reference distance for the buffer analysis. This analysis was conducted to ascertain the number of communities that fall outside the WHO recommended distance to access health facilities.

This study also used descriptive statistics to analyze some aspects of the data. The measures of central tendency like frequencies, ratio maximum and minimum all come under this category. The data were likewise presented in a table form to provide a better explanation of the phenomenon being studied.

The qualitative data acquired from the fieldwork was processed by coding, finding patterns and categorizing the data set into themes. This helped to explore the relationship between the variables in helping to make a logical and systematic series of evidence. The framework for the qualitative analysis employed in this study was in three stages. Thus, familiarisation with the data (the transcripts were read by all research team members; 2) Themes were identified in the framework (themes were compared and discussed among the research team for consensus building). Themes were identified based on the five dimensions (availability, geographical location, affordability and acceptability); 3 creation of index (Identification of the fundamental nature or the core meaning of each theme) using the QDA Miner software.

3 Result

3.1 Accessibility to primary health care

This study examines access to primary health care by measuring spatial distance, travel time, mode of transportation used to reach the facility, type of road network, etc are considered to assess physical accessibility.

3.1.1 Mapping of health care facilities within the district

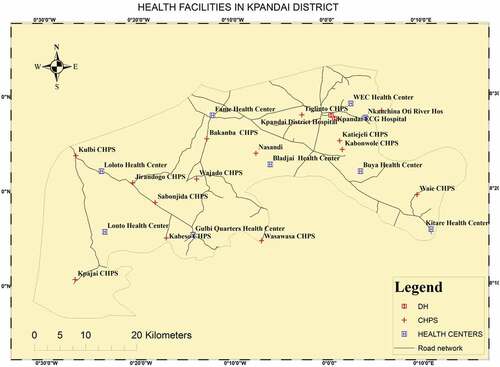

From Figure , there are 25 health facilities in the districts which include one district hospital (DH), and a private hospital (CHAG) that serve the total population of the district with about 275 sparsely distributed communities, there are 8 health centers and 15 service delivery points which may also be referred to as a health post, Community Health Planning and Services (CHPS) compounds with which one of them is malfunctioning, and the health personnel within the district is also not encouraging since the total workers are 201 serving the total population and the communities as a whole as of July 2021.

3.1.2 Spatial distribution of health facilities and its effects on access to primary

The aim of this section is to analyse the spatial distribution of health facilities and its effects on access to primary health care delivery. It is evident from the hospital buffer analysis map that about 90% of the communities fall outside the WHO and Ghana Health Services recommended distance to the nearest hospital which is 5 km. The distance from the farthest communities to the two hospitals which are situated in the District capital is about 197 km. This implies that about 90% of the communities travel between a little above 5 km to 197 km to access primary health care in the two hospitals in the district capital. It was further revealed that those in the extreme southwestern part of the district (see Figure ) cover more than 150–197 km to access the two major hospitals in the district capital. Those at the eastern part of the district cover more than 35 km to 45 km before getting to the district hospital.

It is also evident from Figure that 139 of the communities representing approximately 50.5% of the communities were outside the WHO and Ghana Health Service recommended distance for nearest health facilities (3 km for CHPS and 5 km hospital threshold). This implies that little over half of the communities in the district are affected by the spatial distribution of the health facilities, that is, the hospitals, CHPS, Health Centers and the Hospitals.

Below are the quotations from key informants and focus group discussions explaining the nexus between the spatial distribution of health facilities and access to primary health care in the study area:

“There are only two hospitals providing health services to the people in this district. They are however located in the heart of the district which isfar from a lot of communities in the district. This is having serious implications on access to primary health cares because patients sometimes have to cover anaverage distance of about 80 km to access the two hospitals. People have lost their lives traveling to the hospital. Those at extreme south western part even prefer to cross the river for about 30 km to access health care from neighboring districts. Most of the indigenes complain, they do not get better treatment (Representative of District Health Directorate, 2021).

“I lost one of my wives due to the far distance of the district hospital to his community; the nature of the road from our place to Kpandai is nothing to write home about we use tricycles (motor king) to carry sick people to the district on this our bad road, that had killed a lot of people in this community”, (Chief, 2021).

“The distance to cover from Kpajai to Kpandai scares us when posted to the district. Due to the nature of the road network, anytime we travel from here to the District capital we face a lot of challenges including armed robbery from criminals who hide in the bushes to harm us or take our valuables from us”, (In-charge, 2021).

“Women love children but, in this community, childbirth is a matter of life and death because the hospital is far and the roads are not good at all, last month I was referred to the district hospital during my labor because I was bleeding. There was no car, so my husband had to carry me on his motorbike for 2 hours’ journey. I gave birth in the middle of the road and was taken back home” (Female FGD, 2021).

“For us, in this community, we are closer to our graves than to any health facility, the problem is that there are no roads as you have witnessed yourselves we crossed rivers to get to Yeji. Kpajai CHPS compound is closer but the nurses there gives only paracetamol whatever your situation is. Some of us are forced to treat ourselves and that brings complications sometimes” (Male FGD, 2021).

4. Time and distance of health care centre from home

Concerning the time and distance patients cover to access health care at the nearest health facility and the hospital in the district capital, it was revealed that patients cover more distance and spend more time to access health care due to the poor nature of some of the roads as well as the need to cross the Oti River. It is evident from Supplementary Table S3 that the average distance from the homes of patients to the hospitals is higher than that of the WHO’s and Ghana Health Service recommended optimal distance (5 km) to secondary health facilities. Similarly, most of the populace has to cover more than 3 km to access primary health care in the nearest health facility. This, coupled with the bad nature of most of the roads linking health facilities, has prolonged travel time to a health care centre, all of which pose barriers to timely access to health care (See Table ).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics on health works and facilities characteristics

5. Mean and mode of transport

Some of the rural communities in this study district are accessible by walking or motorbike due to poor road conditions, particularly in the rainy season. The distance to the health facilities and the lack of accessible and affordable vehicles are major obstacles in accessing primary health care. A lot of the rural folks are unwilling to walk for so long, do not want to walk alone, and are afraid they will die in the bush road.

“I feel so reluctant to visit the health facility because sometimes I have to travel alone by foot for more than 6 kilometres in my sick conditions.” (Female FGD, 2021).

“Our road is not good at all, so drivers do like coming to our community. Drivers who ply on our road charge higher because the roads are not good, especially raining season. Most of my people travel to the CHP by walking or motorbike Even pregnant women.” (Assembly member, 2021)

“Hmm, our roads are so terrible during raining season. The use of motorbikes is even difficult during raining season. The time and how long we walk to the clinic make it difficult so seek for orthodox medical treatment when we are sick. We prefer putting some herbs together for treatment” (Assembly member, 2021)

“My brother, this area has transport issues. The cars mostly travel twice a week and they are mostly during market days. Our major means of transport are motorbikes and walking. Most of our roads are motorable during the rainy season” (Assembly member, 2021)

“We sometimes lose lives before the patients get to the health facilities. Some of these lives could have been saved if they had gotten to the health facilities a bit early. When you ask relatives why they delayed, they always attribute it to default in getting means of transport and bad nature of the roads. This is one of our major challenge” (In-charge, 2021).

“Truly speaking, the distance from most the villages to the health facilities is not too long, but because the roads are bad and sometimes they have to walk. It makes the time travel to access health care long than it is supposed to be” (Assembly Member, 2021).

5.1 Availability of primary health care facilities, personnel, drugs and equipment

The availability of health facilities and health personnel constitutes an integral aspect of access to primary health care. The health systems in the district are very poor with a total number of 25 health facilities which include one district hospital (polyclinic), and a private hospital (CHAG) that serves all the total population of the district with about 275 sparsely distributed communities, there are 8 health centers and 15 CHPS compounds with which 1 of them are malfunctioning, the health personnel within the district are also not encouraging since the total workers are 201 serving the total population and the communities as a whole as of July 2021. Analyses of the health facilities and composition of health personnel help to understand the effect of the accessibility of primary health care delivery. Table shows the various health facilities, the number of health workers available, the status of the health facilities and health practitioner’s patient ratio of the study area.

It is evident from Table that the district capital which hosts the two hospitals has only 2 medical doctors who serve the entire population of the district; it is clearly seen from the data that the doctor-patient ratio has exceeded the threshold which is 0.015:1,000 in the district as against the desirable doctor–population ratio of 1:1,000 by the WHO (Kumar & Pal, Citation2018). It was further revealed that the health personnel (doctors, nurses, Midwives)-patient ratio is 0.823:1,000 for the two hospitals in the district capital as against the estimate based on the SDG index (4.45 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1000 population). Moreover, not all the health facilities in the district meet the same standard. From the ratio, analyses show that the health workers work tirelessly all day and night, which mounts a lot of pressure on them. Below is a quotation from the District Health Director,

“We have only two medical doctors in the district who are not always available due to some factors, they are to serve the entire population of Kpandai district, but our neighboring districts also face same problems interns of health so they all run here when they are emergencies, doctor-patient ratio is too high in this district” (District Health Directorate, 2021).

In the same breath, the situation for the nurses and midwives in the district was the same. It can be observed from Table that the nurses and midwives-population ratio for almost all the CHPs facilities is lower than the WHO’s recommended 1-nurse-to-1,000 ratio. Moreover, it can also be said that health workers in communities with high population suffer more due to the huge number of population and less number of health workers.

Also, the information gathered from the study indicated that most of the facilities lack locomotive devices that can transport individuals when there are emergencies, the government ambulance that was brought into the district is stationed at the district capital which serves only a few of the population neglecting the other strata that are far apart from the district hospital, all the health centers and CHPS does not have transport facilities such as ambulances in them which result in deaths and more complications since there is no quick means of transport when there is an emergency.

“Hmmm, the district is heavily challenged with means of transport. Sometimes they have to carry pregnant women on motorcycles to the district hospital for health care. It is so pathetic but we don’t have any option” (District health official, 2021)

On waiting time, most of the participants indicated that they wait for a very long time before getting treatment, especially during market day.

“It didn’t take long at all to see a health personnel when we visit. We wait for a bit longer to see a doctor or a physician when you visit the Kpandai hospital, especially on market days” (Female FGD, 2021),

“I mostly wait for about 20 to 30 minutes to see a nurse. I don’t think that is too long comparing that with visiting the hospital at Kpandia. You can spend about half a day there, before seeing a doctor.” (Male FGD, 2021).

“In some case, you don’t even wait for five minutes before you are treated.” (Male FGD, July 2021)

“During raining season, the toad becomes muddy and slippy which makes its usage difficult. Mostly I spend 10 to 15 minutes to visit the clinic. But it usually takes me about 50 to 2 hours to get to the clinic in the rainy season depending on how bad the road becomes” (Assembly member, 2021).

For the language barrier, it was revealed in the study that most of the health facilities have at least one person that understands the local language. Beyond that, most of the participants indicated that some of the health personnel who do not understand their language speak English to them.

“We are fortunate to have some of our people as health personnel and so communicating with them is not difficult at all” (Male FGD, July 2021),

“There was a day I met nurses who could not speak our native language, so they had to call a man who understand our language and English to help interpret the conversation. It was a bit difficult but I was treated at the end of the day.” (Female FGD, 2021).

“For language, it has never been a barrier. The health worker. Can speak our language. Those that can speak seek the help of interpreters. The discussion are easier for some of us who can speak both English and our local language” (Male FGD, 2021).

On the availability of skilled health personnel, it was discovered that the health facilities have the necessary health personnel to mine the facilities.

“Yes, the nurses and midwives are very good. I have the knowledge and the skill to discharge their duties well. We are satisfied really satisfied” (Assembly member, 2021).

“Most of them are good. I have only encountered one nurse I think had limited skills and knowledge because she was struggling to just give me an injection. I nearly had upset after her injection” (Female FGD, 2021).

The participants were also asked about the availability of drugs and equipment in the health facilities.

“Oooh Yes, there are always drugs and basic equipment for treatment. If the facility does not have the equipment or drug to treat you, they refer you to a Pharmacy at Kpandai or Kpandai hospital” (Female FGD, 2021).

“They always give us only malaria drugs and paracetamol. That is why I mostly prefer to go to Kpandai or buy over -the-counter drugs ” (Male FGD, 2021).

“Overall, I am satisfied with the drugs they give to my people and the equipment at our clinic. Even though, they are not the best.” (Male FGD, 2021).

“About a month ago, I visited the clinic. I was so sick. Just because of common malaria testing, I was referred to Kpandai hospital all in the name of there is no equipment to do the testing. I was so surprised and annoyed” (Male FGD, 2021).

5.2 Affordability of primary healthcare

Affordability is the extent to which something is accessed as measured by its cost relative to the amount that the purchaser or the user is able to use or pay to ease health facilities. Affordability has a lot of meaning based on the subject in which it is used but in, this study affordability will be limited to the use of the health care facilities in our study area. The information gathered from the research indicated that so many people do not have the means to even travel to health facilities, moreover most people cover long distances before getting to a health facility. Most people cannot even buy medicines when they visit some of the facilities. Therefore, people who are able to acquire a health insurance card enjoy some level of affordability when they visit the health care facility as compared to people who do not have the card since the insurance covers some or most of the medicines. Below are statements made by respondents;

“Whenever we visit the health facility, the medicines given to us are always high prices even if we go to the facility with health insurance card too they don’t value it, common paracetamol with some few medicines given to me cost 95 Ghana cedis which is too high and because of that I find it difficult to visit the facility whenever am sick and rather seek for herbal medicines to cure my sickness” (Male FGD, 2021)

“Moreover, as a result of poverty, most people are not able to acquire the means of getting money to help pay for their hospital bills and dodon’tave NHIS as well, it's only women who struggle to come to us for treatment with their children, sometimes with empty hands, we have no option than to save their life’s and forfeit the money. One of the midwives in a community said”, (In-charge, 2021)

“Getting access to money in this our community is very difficult we sometimes go for health services for free without paying them because they don’t have money, sometimes most of our children die in our hands as they fall sick. Poverty is very high here, even as we speak now some of us don’t even have what to eat this evening”, (FGD, 2021).

“The last time I went to Nasandi CHPS, I was asked to go the government hospital for an eyes examination. They gave me a referral note, but I realised I cannot afford the cost. So I decided throw the paper away and stayed” (Male FGD, 2021)

“About two months ago, I had a motor accident, so was sent to the hospital. I was seriously bleeding. I was not attended to because they were demanding money to buy blood but I could not afford it. A philanthropist came to my aid, before they attended to me … . Hmmm I thought I was going to die” (Male FGD, 2021)

The above statement indicates that most of the indigenes are financially handicapped and for that matter the low level of affordability to health facilities.

5.3 Acceptability of primary healthcare

Acceptability is the characteristic of a thing being subjected to acceptance for some purpose. Putting acceptability into the context of health, it can be explained as a multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a health care intervention consider it to be appropriate based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention. The health workforce characteristics and ability (e.g., age, sex, language, culture, etc.), to treat all patients with dignity, create trust, and promote demand for services.

The information gathered from the research shows that there is one way or another rivalry between the citizens and the health workers in most of the facilities visited. Most of the people complained about the attitude of the health workers in the communities visited. It was only one community that recorded a good relationship between the people and the health workers, in the other communities; it is either the health workers having problems with citizens or the citizens having problems with the health workers in the community. The relationship between the health personnel and the patients is very poor which is not promoting rural health delivery, and almost all community members complained bitterly about the attitude of the health workers they have. Below are some of the complaints gathered from the focus group discussions;

“The midwife we have here always insult our wives and humiliate them anytime they visit the facility, the kind of words she uses on us is so appalling, she has no respect for mankind in this community, so we all has decided not to visit the facility anymore, we now have to go to Banda or Kpandai while there is a facility by us”. (Male FGD, 2021)

“As for the nurses in this hospital, I don’t how they see themselves, I lost my mother to death because of the attitude of the nurses we have here, my mother was brought in a tricycle here, these nurses who were on duty didn’t even care to see what was happening to her, I have to carry her with the tricycle rider on our shoulders into the ward and when we got to the ward they even didn’t care to asked what was the problem, when I confronted them, one of them told me she was old enough to die” (Male FGD,2021).

“Some of the nurses are really good, they pay a lot of attention to us when we visit the hospital. But the way most of the nurses sometimes behave and treat us as if they already have a problem with us or the person that brought them to the town.” (Female FGD, 2021).

“I have never had any complaints that health personnel has treated my people unfairly due to gender or belief. The only issue that keeps coming up is how health workers treat patients differently due to their social class. Sometimes, they treat teachers and other government workers better than us. I do really know why they do that but I think it is totally wrong” (Assembly member, 2021.

“I one day visited the health facilities, the Nurse at the OPD was on phone was I was sleeping a bench. I slept there for more than 30 minutes. I later decided to go home. When she saw me going, she started approaching but I didn’t mind her. I went home with my sickness” (Male FGD, 2021.

“We once had a community engagement and one striking issue that emanated from the discussion of poor reception of health workers. Even though we were surprised but we have been talking to the worker ever since. It is normal, patients always want to be attended to quickly whenever they visit health facilities but the are so many factors that sometimes affect our work but they don’t understand” (District Health, Directorate, 2021.

In response to the above claims against the health practitioners, key informant interview with the in-charge indicated that they have not been treating patients badly at all. Below is a quotation from an in-charge of a health facility;

“We are not like that and such an incident had never happened in this facility but the human character can’t be told or predicted, we are of individual differences, nurse who has such attitudes brought them from their home as the adage goes charity begins at home, we are sorry if this everhappened” (In-charge, 2021).

5.4 Adequacy of primary healthcare

The study examines adequacy in terms of the quality of service delivered and the kind of treatment administered by the service providers. Thus, it was also ascertained whether the patients trust the medical capabilities of the health facilities and are satisfied with the quality of service or personal behaviour of all facility personnel right from the point of entry to the facility.

“The health workers are good, just that some of them sometimes behave as if they are not ready to attend to us. The nurses at Nasandi facility are full of humour and very experienced.” (Female FGD, 2021).

“I am fairly satisfied with the number of health workers we have and the quality of service rendered to my people. They can do better than they are doing now. My only worry is that sometime they are few health workers attending to us.” (Male FGD, 2021)

“Yes, the district hospitals has a laboratory, where all laboratory test are done.” (Male FGD, 2021)

“The facilities at the district hospitals are good. There are doctors and a lot of nurses who attend to us whenever we visit the hospital” (Female FGD, 2021).

6 Discussion

Ensuring access to primary health care in rural communities is a crucial component in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3: good health and well-being. Universal health coverage has been identified as a vehicle for the attainment of this goal. This implies that healthcare facilities should be generally available, accessible, acceptable, appropriate, and of good quality (Campbell et al., Citation2013). To the best of our knowledge, the current academic discourse on this accessibility to primary health care appears to have focused on some key dimensions used to measure accessibility of health care facilities (Arcury et al., Citation2005; Asaah & Ussiph, Citation2017; Comber et al., Citation2011; Dos Anjos Luis & Cabral, Citation2016; Mobley et al., Citation2006), especially in rural communities in Ghana. This study, therefore, sought to analyse the spatial distribution of healthcare facilities and its effects on access to primary healthcare in rural communities in the Kpandai district of Ghana.

Distance to health facilities is an important impediment to facility delivery in rural Ghana (Nesbitt et al., Citation2016). Greater geographical distance to health facilities might lead to an increase in travel time and cost for patients (Buor, Citation2016). The findings reported indicate health care is not being sought for a substantial proportion of the communities in the district fell outside the WHO and Ghana Health Service estimated the optimal distance to access secondary. The total communities within the 5 km buffer of secondary health facilities in the Kpandai District were estimated as 136% representing 49.5% of the total population. This means that there is an uneven spatial distribution of health facilities. This finding is not surprising since a study conducted by Blanford et al. (Citation2012) on accessibility to hospitals, maternity and integrated health centers in Niger concluded that there is significant geographic variation in access to health facilities in Niger. Yin et al. (Citation2018) also affirm that there is poor spatial accessibility of healthcare facilities in China. The results of this study suggest that access to primary health care services appears low with an estimated 75.2% of the population were outside the 5 km distance threshold of all health care facilities. This implies that a little over 50% of the communities travel for more than 5 km to access health care at the district hospital. This finding disagrees with Ashiagbor et al.’s (2020) argument that access to health care in general appears to be high since 81.48% of the population in the Ashanti Region, Ghana, are within 5 km distance of all healthcare facilities. The study is inconsistent with Lechowski and Jasion (Citation2021) assertion that the average distance to access primary health care is about 5 km among rural folks in Poland. It was further revealed that most of the communities and population travel more than 3 km to access health at the Health centers and Community Health Planning and Services (CHPS). It is evident that the average travel time to the nearest primary health facilities is about 42 minutes to travel from home to access health care at the nearest health facility. This seems to corroborate Carrasco-Escobar et al. (Citation2020) assertion that the countrywide median travel time from each village to the nearest primary health care facility is about 39 minutes. However, this finding is inconsistent with the findings of a study conducted by Tanser et al. (Citation2006) on modeling and understanding primary healthcare accessibility and utilization in rural South Africa: an exploration using a geographical. The study concluded that the median travel time to the nearest clinic is 81 min and 65% of the homesteads travel 1 hour or more to attend the nearest clinic.

The study also found that the bad nature of the roads linking communities to health facilities was one of the major factors accounting for poor access to primary health care in the district. The impact of transportation challenges on healthcare utilization has been extensively explored in the literature (Oduro Appiah et al., Citation2020; Agyemang-Duah, Peprah et al., Citation2019). Bad roads (see Figure ) resulted in increased time spent and traveling expenses by patients traveling to access health facilities which is one of the major reasons behind the access to primary health care in the district hospitals by the residents. This partly confirms the study by Atuoye et al. (Citation2015) that “walking for more than 10 km to CHPS compounds is common in the rural areas because of the poor nature of roads.” Most of the rural communities in this study access primary health care by walking or motorbike. The use of cars is more expensive due to the bad nature of the roads. The lack of accessible and affordable means of transport is a major obstacle to access to primary health care (Syed et al., Citation2013).

In this study, we view availability from two dimensions: 1) availability of health facilities, 2) availability of health personnel. The study revealed that the availability of health facilities in the district was fairly good, with a total number of 25 health facilities with only 1 of them malfunctioning. It was also revealed that the health centers do not provide treatment for some sicknesses, meaning that patients are referred to the district hospital or to the private hospital (CHAG) when it is a major medical case. In this regard, communities that are in the far extreme south western part prefer to cross the river for about 30 km to access health care from neighboring districts. The implication is that the unequal distribution of healtcare facilities is impeding the realization of the sustainable development goal three (3). This is why Asaah and Ussiph (Citation2017) posited that equity is mostly measured as per the availability, utilization and outcomes of the services. It is evident that the district capital which hosts the two hospitals has only 2 medical doctors who serve the entire population of the district. It is clearly seen from the study that the doctor–patient ratio has exceeded the threshold which is 0.015:1,000 in the district as against the desirable doctor–population ratio of 1:1,000 by the WHO (Kumar & Pal, Citation2018). It was further revealed that the health personnel (doctors, nurses, midwives)-patients ratio is 0.823:1,000 for the two hospitals in the district capital as against the estimate based on the SDG index (4.45 doctors, nurses and midwives per 1000 population; Resources et al., Citation2016). The implication is that if proper policies and measures are not put in place, the government of Ghana may not be able to achieve its aim of doctor-patient ratio of 1:1000 by 2024 as recommended by the WHO. Our analysis further showed that participants see the health workers in the district as knowledgeable and skillful. Particularly within the African context, an exploratory study was conducted by Ameh et al. (Citation2016) on the knowledge and skills of healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia before and after Competency-Based Training in Emergency Obstetrics and Early Newborn Care. Ameh et al. (Citation2016) found that there are significant improvements in knowledge and skills for each cadre of healthcare providers and for each country. Concerning the availability of drugs and health equipment, most of the participants indicated they were satisfied with the drugs administered and equipment at the health facilities. These findings agree with Durgawale (Citation2014) assertion that community members are averagely satisfied with services provided by health workers in rural areas.

With respect to the affordability of primary health care, our study found that the respondents find it difficult to access primary health care partly due to their inability to afford travel expenses to health facilities as well as their inability to buy medicines when they visit some of the facilities. It was further found that people with health insurance card enjoy some level of affordability when they visit the health care facility as compared to people who do not have the card since the insurance covers some or most of the medicines. This finding is consistent with that of Fenny et al. (Citation2014) that a higher percentage of patients with insurance are satisfied with the overall quality of care compared to the uninsured.

The study also found that the acceptability of patients by health personnel in the district was very low. In line with a previously published work in Ghana (Agyemang-Duah et al., Citation2020), the relationship between the health personnel and the patients is very poor which is not promoting rural health delivery, and almost all community members complained about thee attitude of the health workers they have. This ultimately discouraged people who are sick from seeking medical care and hence impeding access to primary health care. On the contrary, the health personnel claimed that they are very receptive and professional to the patients who visit their facilities. However, enormous pressure on the few available personnel sometimes leads to unusual misconduct of some of the health workers. This is in line with the assertion made by Mooney (Citation1983) that the problem of access to health care in developing countries manifests in two folds. On the supply side, the provision of health care facilities, and in instances where the facilities are provided, quality and effective services from these facilities may be missing perhaps due to inadequate resources whilst on the demand side, people may not get access to health service from which they could benefit.

The findings suggest that the local people are fairly satisfied with the adequacy of the service administered by the health personnel and the kind of treatment offered by the service providers.

7. Conclusion and recommendations

This study found that health facilities are poorly distributed spatially which has had negative implications on access to primary health care. In addition, our study generally concludes that access to primary health is fairly poor in terms of availability, accessibility, acceptability, affordability, and adequacy. However, walking and/or motorcycles are especially important in improving accessibility of health care facilities, especially in developing countries where access to private and public transportation services is limited. Therefore, several types of spatial data should be collected and health planners need to take all types of transportation into account when planning for setting up a new public and/or private health facilities. They also need to consider the economic and social backgrounds of the health centre users. Based on the findings, we recommend a community model for integrating the community ambulance system into CHPS compounds and health centers. This can be done by identifying community influencers. These influencers could be prominent people from the community, chiefs and elders who can influence community’s actions. If these community influencers are sensitized on the need for an emergency transportation fund, they will develop a broad-based action plan to rally the entire community into the process. Hence, help in the contribution towards the developmental plan with strategic mode of payment that will be accepted equally by them. The entire community also decides the amount each household should contribute either monthly or after harvest seasonally.

In the western part of the district thus Sabonjida sub-district and the Ekumdi Sub-district which host more than 50% of the communities and in the Eastern part thus Kitare sub-district, Kanbonwuli sub-district and Biladjai sub-district of the district, the government in collaboration with the NGOs and the District Assembly should build a well-standard polyclinic or a higher grade hospital to serve the numerous communities that falls within the enclave since the distance to cover to the district capital is too far, that is more than 3 hours and one and half hours, respectively, before getting to the district hospital which is against the WHO standard of distance to be covered. Also, the government or the district assembly should provide a fast boat for the rural communities that are beyond or closer to the Oti River and Volta Lake to be able to access health care services and for emergencies since most of the communities are closer to the Pru District (Yeji) with regard to proximity and means of transport as compared to the traveling distance on the road to the district capital. In addition, more health personnel and equipment should be made available in the district to occupy the vacant positions in the sector and also reduce pressure on the available health facilities and workers since the doctor-nurse-patient ratio is 1:1000 as against 1:34,429 and 1:4324, respectively, in the district. The relationship between health care providers and patients can be improved by implementing attitudinal change programmes such as regular orientations, sensitisation, strict monitoring and supervision of the attitude of health care staff. Lastly, there is a need for an integrated and cross-sectoral approach to improve accessibility to healthcare services in rural communities.

The spatial analysis method employed in the study used Euclidean distances. The method is useful for this study because it is being used to ascertain whether or not the resident meets the recommended threshold distance proposed by the WHO and Ghana Health Service. However, it assumes that travel occurs in a straight line and ignores the influence of transport services on accessibility and barriers of travel such as land use, road network and elevation (Guagliardo Citation2004; Neutens Citation2015).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/27707571.2023.2183566.

References

- Agbenyo, F., Marshall Nunbogu, A., & Dongzagla, A. (2017). Accessibility mapping of health facilities in rural Ghana. Journal of Transport and Health, 6(November2016), 73–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.04.010

- Agyemang-Duah, W., Peprah, C., & Peprah, P. (2019). Barriers to formal healthcare utilisation among poor older people under the livelihood empowerment against poverty programme in the Atwima Nwabiagya District of Ghana. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7437-2

- Agyemang-Duah, W., Peprah, C., & Peprah, P. (2020). Factors influencing the use of public and private health care facilities among poor older people in rural Ghana. Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-018-01010-y

- Ameh, C. A., Kerr, R., Madaj, B., Mdegela, M., Kana, T., Jones, S., Lambert, J., Dickinson, F., White, S., & Van Den Broek, N. (2016). Knowledge and skills of healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia before and after competency-based training in emergency obstetric and early newborn care. PLoS ONE, 11(12), e0167270. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167270

- Arcury, T. A., Gesler, W. M., Preisser, J. S., Sherman, J., Spencer, J., & Perin, J. (2005). The effects of geography and spatial behavior on health care utilization among the residents of a rural region. Health Services Research, 40(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00346.x

- Asaah, K., & Ussiph, N. (2017). Optimizing access to primary health care services in rural communities using geographical information system (GIS): A case of Atwima Mponua district of Ghana. International Journal of Computer Applications, 163(10), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2017913728

- Ashiagbor, G., Ofori-Asenso, R., Forkuo, E. K., & Agyei-Frimpong, S. (2020a). Measures of geographic accessibility to health care in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. Scientific African, 9, e00453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00453

- Atuoye, K. N., Dixon, J., Rishworth, A., Galaa, S. Z., Boamah, S. A., & Luginaah, I. (2015). Can she make it? Transportation barriers to accessing maternal and child health care services in rural Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1005-y

- Blanford, J. I., Kumar, S., Luo, W., & MacEachren, A. M. (2012). It’s a long, long walk: Accessibility to hospitals, maternity and integrated health centers in Niger. International Journal of Health Geographics, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-11-24

- Brenner, H., & Mckiney, A. (1983). Unemployment and health in the context. Social Science & Medicine, 17(16), 1125–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(83)90419-6

- Buor, D. (2016). Distance as a predominant factor in the utilisation of health services in the Kumasi metropolis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 56(2), 145–157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41147677

- Buor, D. (2016). Distance as a predominant factor in the utilisation of health services in the Kumasi metropolis, Ghana. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 56(2), 145–157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41147677

- Campbell, J., Buchan, J., Cometto, G., David, B., Dussault, G., Fogstad, H., Fronteira, I., Lozano, R., Nyonator, F., Pablos-Méndez, A., Quain, E. E., Starrsj, A., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2013). Ressources humaines pour la santé et la couverture sanitaire universelle: Promouvoir l’équité et une couverture efficace. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91(11), 853–863. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.118729

- Carrasco-Escobar, G., Manrique, E., Tello-Lizarraga, K., & Miranda, J. J. (2020). Travel Time to Health Facilities as a Marker of Geographical Accessibility Across Heterogeneous Land Coverage in Peru. Frontiers in Public Health, 8(September), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00498

- Chatora, R. R., & Tumusime, P. (2004). Primary health care: A review of its implementation in sub-Saharan Africa. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 5(4), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1191/1463423604pc220oa

- Comber, A. J., Brunsdon, C., & Radburn, R. (2011). A spatial analysis of variations in health access: Linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions. International Journal of Health Geographics, 10(44), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-10-44

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE Publications https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384368.

- Dos Anjos Luis, A., & Cabral, P. (2016). Geographic accessibility to primary healthcare centers in Mozambique. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0455-0

- Durgawale, M. B. S. P. M. (2014). Nursing Audit of Health Workers Providing Health Services in Rural Area with Special Emphasis to Community Satisfaction in Satara District. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 3, 2. http://www.ijsr.net/archive/v3i2/MDIwMTM1MDg=.pdf

- Fenny, A., Okua, P., Enemark, U., Asante, F. A., & Hansen, K. S. (2014). Patient satisfaction with primary health care - a comparison between the insured and non-insured under the National Health Insurance Policy in Ghana. Global Journal of Health Science, 6(4), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p9

- Forero, R., Nahidi, S., De Costa, J., Mohsin, M., Fitzgerald, G., Gibson, N., McCarthy, S., & Aboagye-Sarfo, P. (2018). Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2012). Population and Housing Census, summary of Report of final results. Ghana Statistical Service. https://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/marqueeupdater/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf

- Guagliardo, M. F. (2004). Spatial accessibility of primary care: Concepts, methods and challenges. International Journal of Health Geographics, 3(1), 1–13 .https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-3-3

- Hall, J. J., & Taylor, R. (2003). Health for all beyond 2000: The demise of the Alma-Ata Declaration and primary health care in developing countries. Medical Journal of Australia, 178(1), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05033.x

- Kosny, A., & MacEachen, E. (2010). Gendered, invisible work in non-profit social service organizations: Implications for worker health and safety. Gender, Work and Organization, 17(4), 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00460.x

- Kumar, R., & Pal, R. (2018). India achieves WHO recommended doctor population ratio: A call for paradigm shift in public health discourse! Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 7(5), 841. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_218_18

- Lechowski, Ł., & Jasion, A. (2021). Spatial accessibility of primary health care in rural areas in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179282

- Levesque, J., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Access Review2012. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12:18, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Lu, X., Zhang, X., Li, L. Y., & Chen, H. (2014). Assessment of metals pollution and health risk in dust from nursery schools in Xi’an, China. Environmental Research, 128, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2013.11.007

- Manoranjitham, S., Charles, H., Saravanan, B., Jayakaran, R., Abraham, S., & Jacob, K. S. (2007). Perceptions about suicide: A qualitative study from southern India. Natl.Med.J India, 20(4), 176–179. http://nmji.in/archives/Volume_20_5_September_October_2007/Vol-20-5-Feature-Perceptions-about-Suicide.pdf

- Mobaraki, H., Hassani, A., Kashkalani, T., Khalilnejad, R., & Ehsani Chimeh, E. (2013). Equality in distribution of human resources: The case of Iran’s Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 42(1 SUPPL 1), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1874-6047(12)60792-4

- Mobley, L. R., Root, E., Anselin, L., Lozano-Gracia, N., & Koschinsky, J. (2006). Spatial analysis of elderly access to primary care services. International Journal of Health Geographics, 5(19), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-5-19

- Mooney, G. H. (1983). Equity in health care: Confronting the confusion. Effective Health Care, 1(4), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-5399(83)80032-3

- Nankwe, H. (2017). District chief of Kpandai Cries for development - Kofi Tatablata. Modern Ghana. https://www.modernghana.com/news/807979/district-chief-of-kpandai-cries-for-development.html

- Nesbitt, R. C., Lohela, T. J., Soremekun, S., Vesel, L., Manu, A., Okyere, E., Grundy, C., Amenga-Etego, S., Owusu-Agyei, S., Kirkwood, B. R., & Gabrysch, S. (2016). The influence of distance and quality of care on place of delivery in rural Ghana. Scientific Reports, 6(August), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30291

- Neutens, T. (2015). Accessibility, equity and health care: Review and research directions for transport geographers. Journal of Transport Geography, 43, 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.02.006

- O’Donnell, O. (2007). Access to health care in developing countries: Breaking down demand side barriers Acesso aos cuidados de saúde nos países em desenvolvimento: Rompendo barreiras contra a demanda. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 23(12), 2820–2834. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2007001200003

- Oduro Appiah, J., Agyemang-Duah, W., Peprah, C., Adei, D., Peprah, P., & Fordjour, A. A. (2020). Transportation barriers to formal healthcare utilisation and associated factors among poor older people under a social protection programme in Ghana. Journal of Transport & Health, 19, 100965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100965

- Peters, D. H., Garg, A., Bloom, G., Walker, D. G., Brieger, W. R., & Hafizur Rahman, M. (2008). Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries Related papers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.011

- Phommachanh, S., Essink, D. R., Jansen, M., Broerse, J. E. W., Wright, P., & Mayxay, M. (2019). Improvement of Quality of Antenatal Care (ANC) Service Provision at the Public Health Facilities in Lao PDR: Perspective and Experiences of Supply and Demand Sides. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2345-0

- Pillay, N. K., & Maharaj, P. (2013). Aging and health in Africa. Aging and Health in Africa, 3, 1–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8357-2

- Resources, H., Observer, H., & No, S. (2016). (Issue 17). WHO Library Cataloguing. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250330/9789241511407-eng.pdf

- Syed, S. T., Gerber, B. S., & Sharp, L. K. (2013). Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. Journal of Community Health, 38(5), 976–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1

- Tanser, F., Gijsbertsen, B., & Herbst, K. (2006). Modelling and understanding primary health care accessibility and utilization in rural South Africa: An exploration using a geographical information system. Social Science and Medicine, 63(3), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.015

- Wagstaff, A., Bustreo, F., Bryce, J., & Claeson, M. (2004). Child Health: Reaching the Poor. American Journal of Public Health, 94(5), 726–736. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.5.726

- Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(SUPPL. 1), 40–46.

- Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(SUPPL. 1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036

- World Health Organization. (2019). Current health expenditure (% of GDP) - Ghana. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=GH

- Yin, C., He, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, W., & Gao, Y. (2018). Inequality of public health and its role in spatial accessibility to medical facilities in China. Applied Geography, 92(January), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2018.01.011