Abstract

Abstract: Consumption of addictive substances during pregnancy has been linked with a range of adverse maternal and child health outcomes. The aim of this study was to assess the rates of prevalence of addictive substance use and determine associated risk factors among pregnant women in pastoral community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia. A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed to recruit a total of 484 pregnant women pastoral community in the Afar Region, Ethiopia. A simple random sampling technique was employed to enroll the eligible pregnant women using the health extension workers’ family logbook as a sampling frame. Bayesian multivariable logistic regression model was employed using adjusted odds ratio with a 95% Bayesian credible interval. The overall prevalence of substance use during pregnancy was 48.1% [95% CI 39%, 62%]. Of these, 37.6% (95% CI: 33.3–42.1%) were khat chewers, 12.2% (95% CI: 9.5–15.4%) were alcohol drinkers, and 12.6% (95% CI: 9.9–15.9%) were cigarette smokers. Maternal younger age tertiary education level, unplanned pregnancy, husband/partner substance use, and household led by a wife only were positively associated but having four or more ANC visits was negatively associated with maternal prenatal substance use. The prevalence of maternal substance use during pregnancy among the pastoral community in the current study setting was relatively higher. Our finding suggests the urgent need for educational campaigns, screening, and targeted interventions for women of childbearing age in the pastoral community of Ethiopia.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Substance (alcohol, tobacco, and khat) use during pregnancy remains a serious public health issue since it can have several negative effects on both the mother and the unborn child. In Ethiopia, different banning strategies for cigarette smoking and khat chewing were tried through the implementation varies from region to region. Beyond these efforts made by the government: substance use during pregnancy like alcohol drinking and khat chewing is culturally acceptable in the rural and some pastoral communities of the country.

Although few studies were conducted on maternal substance use in Ethiopia, these studies were not representative of women in the pastoral community, like Afar region. Therefore, this study aimed to determine maternal substance use and its determinants among pregnant women in the pastoral community, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia. The burden and determinants of substance use during pregnancy are highlighted by the study’s findings, which can assist physicians, policy planners, and decision-makers. The results will also serve as a starting point for future research.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified alcohol, tobacco, khat, and other illicit drugs as among the top 20 risk factors for health-related problems (Humeniuk & Ali, Citation2006). The term “substance use” refers to the use of any harmful stimulant substances such as alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, khat leaves, illicit drugs, and inhalants that could alter the physiology of the body functions; mentally, physically, or emotionally (Keane, Citation2006). Addictive substance use during pregnancy is one of the critical public health concerns that has been linked with a range of negative maternal and fetal health outcomes such as miscarriage, stillbirth, congenital anomalies, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, low birth weight, and preterm births (Addila et al., Citation2021a; Bayih et al., Citation2021; Behnke, Smith, et al., Citation2013; Forray, Citation2016; Shankaran et al., Citation2007).

The prevalence of maternal addictive substance uses during pregnancy varies across countries, regions, and ethnic groups (Bernstein et al., Citation2015; Crome & Kumar, Citation2007; Wong et al., Citation2011). A meta-analysis of 26 studies has reported prevalence of prenatal alcohol consumption ranging from 4.8% to 23.3% (Lange et al., Citation2017). The prevalence of any addictive substance use during pregnancy ranged from 2.2% to 36.5% in Sub-Saharan African countries (Addila et al., Citation2020; Petersen Williams et al., Citation2014; Popova et al., Citation2016), and 11.3% to 37.9% in East African countries, including Ethiopia (Addis et al., Citation2020; Alamneh et al., Citation2020; Dargie et al., Citation2019; Fetene et al., Citation2021; G. Tesfaye et al., Citation2020; Tesso et al., Citation2017). Maternal age, maternal and her partner/husband’s education level, monthly income, occupation, lack of antenatal care, partner substance use, pre-pregnancy substance use, and place of residence have been identified as risk factors that initiate women’s addictive substance use in pregnant (Fetene et al., Citation2021; Forray, Citation2016; Kotelchuck et al., Citation2017; Mekuriaw et al., Citation2020; Onwuka et al., Citation2016; Petersen Williams et al., Citation2014; Ruisch et al., Citation2018).

Globally, different strategies and guidelines, such as the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control for users, and the WHO guideline for the identification and management of substance use in pregnancy, have been implemented to reduce the burden of substance use during pregnancy (Day et al., Citation1985; Lester et al., Citation2004; Thomas et al., Citation2018; Whittaker, Citation2014). In Ethiopia, different banning strategies for cigarette smoking and khat chewing were tried through the implementation varies from region to region. Beyond these efforts made by the government: substance use during pregnancy like alcohol drinking is culturally acceptable in the rural community which may work for pastoral communities as well.

Although few studies were conducted on maternal prenatal substance use in Ethiopia, these studies were not representative of women in the pastoral community, including Afar region. Moreover, we intended to investigate factors associated with maternal prenatal addictive substance use using a new statistical model, Bayesian analysis approach. Therefore, this study aimed to determine maternal substance use and its determinants among pregnant women in the pastoral community of Northeast Ethiopia.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study setting and participants

This community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2021 to May 2021 in Afar Regional State, Northeast Ethiopia. Afar is one of the nine administrative regions of Ethiopia located in the northeast part of the country and shares national boundaries with the Amhara region on the west, Tigray region on Northwest and Oromia region on the south, and international boundaries with Eretria on the north and Djibouti on the southeast.

Administratively the region is divided into five zones, thirty-six woredas, and five city administrations. As it is one of the emerging regions of Ethiopia, almost all infrastructures are limited which heavily affects the health sector of the region. In the presence of these challenges, the regional government is striving hard to meet the health needs of its pastoralist community with 338 health posts, 6 hospitals, and 96 health centers.

This study involved all pregnant mothers who were living in four randomly selected kebeles during the data collection period. However, pregnant women who were seriously ill, and those who were not permanent residents (i.e., less than six months) of the randomly selected kebeles (lower administrative units in Ethiopia), were not included in this study.

2.2. Sample size determination and sampling techniques

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula with assumptions: 5% marginal error, 95% confidence intervals (CI), Design effect of 1.5, and 26.5% proportion for any substance use in pregnancy that was taken from a study conducted in eastern Ethiopia (Fetene et al., Citation2021) and 10% of the non-response rate, giving a final sample size of 494 pregnant women. Of the five-city administrative in Afar region, we randomly selected two. The randomly selected cities have eight kebeles and we randomly selected four kebeles and then the final sample size was proportionally allocated for each randomly selected kebeles. The lists of pregnant women during the study period were obtained from the shortlist of the health extension program database which was considered as a sampling frame. Finally, a systematic random sampling technique was employed to select pregnant women.

2.3. Study variables

The dependent variable of the study was maternal substance use during pregnancy (Yes/No). It is defined as a self-report of exposure to at least one of the three substances (alcohol or khat or tobacco) during the current pregnancy before the interview irrespective of its dose and frequency (yes/no) (Organization, Citation2010, Citation2014). Alcohol use during the current pregnancy was defined as any consumption of alcoholic beverages during the current pregnancy, regardless of the quantity or frequency, whether they include industrially produced alcohol (ethanol or ethyl content) or locally produced alcohol like Teji, Areki, or Tela (Anteab et al., Citation2014b; Behnke, VC, et al., Citation2013).

Tobacco use during the current pregnancy was defined as ever use of any cigarette, or other smoking tobacco (including shisha/hookah, bidi, and non-smoking tobacco like snuff or chewing tobacco), regardless of amount and frequency (yes/no) (Shanmugam, Citation2017).

Khat use during the current pregnancy was defined as ever chewing of khat during the current pregnancy irrespective of its dose and frequency (yes/no) (Bifftu, Citation2020; Nakajima et al., Citation2017).

Independent Variables: Socio-demographic and economic variables (age, educational status, religion, marital status, occupation, and income), maternal and pregnancy-related variables (gestational age, gravidity, parity, pregnancy plan, and antenatal care (ANC) follow-up), previous substance (cigarette, alcohol and khat use), husband substance use (cigarette, alcohol and khat use), and social and family support were the independent variables.

2.4. Data collection tools and procedures

The questionnaire used was adapted and modified from previous literature conducted in Ethiopia and other developing regions of Africa (Anteab et al., Citation2014a; Bitew et al., Citation2020; Fetene et al., Citation2021; Forray, Citation2016; Macleod et al., Citation2021). The questionnaire consisted of socio-demographic characteristics, and obstetric, medical, and behavioral questions relevant to the experiences of mothers during this pregnancy. The data were collected using face-to-face interviews guided by structured and pre-tested interviewer-administered questionnaires. An independent translator translated the English language into the local language (Amharic), then back to English for consistency. A pre-test of the questionnaire was conducted with 5% (24 participants) of the sample living other than the selected kebeles, Ayisaita 01 kebele. Three days of training were provided for data collectors and supervisors. Eight trained BSc nurses collected the data. Mothers were interviewed in private places to ensure their privacy and to encourage participation.

2.5. Statistical analysis

This Bayesian analysis approach is a strong statistical method in medical and public health research that considers data at hand and pre-existing data with the concept of the posterior distribution (Aychiluhm et al., Citation2020; Birara Aychiluhm et al., Citation2022; Contreras et al., Citation2018). Contrary to the standard logistic regression, which treats the unknown parameters as constant fixed values. In Bayesian logistic regression, the parameters are treated as random variables that might vary based on a probability distribution (known as a prior distribution). For a data-driven model, this change can be viewed as solely stochastic, but the Bayesian approach can also read it as a belief of uncertainty (Kynn, Citation2005).

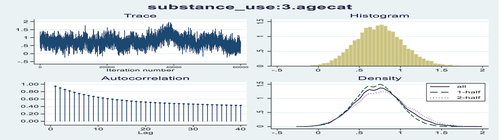

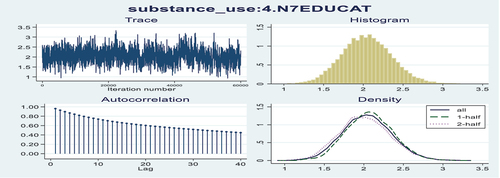

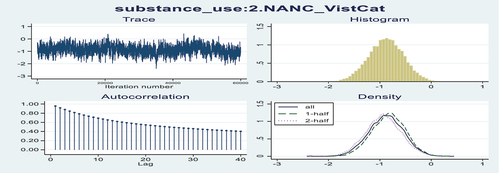

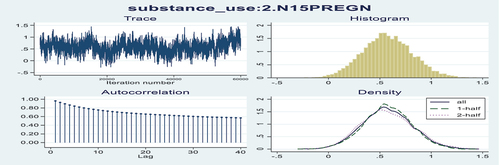

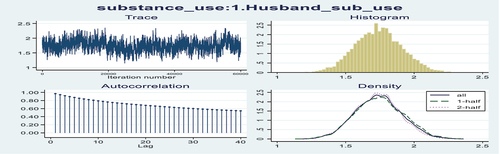

In a Bayesian formulation, the uncertainty about the value of each parameter can be represented by a probability distribution. The key components of Bayesian analysis are the likelihood function, which reflects information about the parameters contained in the data, and the prior distribution, which quantifies what is known about the parameters before observing data. The prior distribution and likelihood can be easily combined to form the posterior distribution, which represents total knowledge about the parameters after the data have been observed. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation with Metropolis-Hastings sampling algorithm was carried out. To assess the convergence algorithm in our study, time series (history) plots, density plots, Autocorrelation plots, and Gelman-Rubin statistics were used.

Data entry and coding were done using Epi-data version 3.1. Data cleaning and analysis were carried out using Stata version 16. Summary statistics were carried out from the posterior distribution. A bayesian multivariable logistic regression model was performed to identify the independent predictors of maternal substance use during pregnancy. Finally, an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% Bayesian credible interval was reported for statistically significant factors associated with substance use.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

In this study, a total of 484 study participants were involved, with a response rate of 97.9%. The mean (SD) age of study participants was 29.4 (±5.92) years. Of the study participants, 341 (70.5%) were Muslim religious followers, 462(95.5%) were married, 198 (40.9%) did not attend formal education, and 367 (75.8%) were housewives (Table ).

3.2. Obstetric and medical-related factors during pregnancy

In this study, 299 (61.8%) pregnant women were in the third trimester of pregnancy and the majority were multiparous 332 (68.6%) and their pregnancy was planned (91.3%). While three-fourths (75.6%) of pregnant women had at least one ANC visit, only 25 (6.8%) of them had four or more visits for the current pregnancy (WHO recommended ANC visits) (Table ).

3.3. Maternal substance use and other behavior-related characteristics

In this study, the overall prevalence of substance use during pregnancy is 233(48.1%: 95%CI 39% to 62%]. Of these participants, 182 (37.6%: 95% CI 33.3 to 42.1) pregnant women chewed khat, 59 (12.2%: 95% CI 9.5 to 15.4) drunk alcohol, and 61(12.6%: 95% CI 9.9 to 15.9) smoked cigarette during the current pregnancy. Furthermore, the prevalence of alcohol, smoking, and khat chewing among partners was 10.7%, 19.2%, and 39.5%, respectively (Table ).

3.4. Bayesian logistic regression analysis

To assess the convergence algorithm in our study, we used autocorrelation, time series plots, Gelman-Rubin statistic, and density plot (Annex Figures ). All the plots showed that the algorithm had reached its equilibrium (target) distribution for all parameters.

In this study, pregnant women aged 25–34 years had greater odds of substance use during pregnancy compared to their counterparts [AOR = 1.87: 95% CI 1.17–2.88]. The study revealed that women who had four or more ANC visits were 56% less likely to use any substances during pregnancy than their counterparts [AOR = 0.44: 95%CI 0.21–0.80]. The odds of substance use during pregnancy was three times higher among women who headed households compared to a husband-headed household [AOR = 2.91: 95%CI; 1.65, 4.81]. We also found that women with substance-user husbands had six times greater odds of substance use during pregnancy compared to women with non-user husbands [AOR = 5.78: 95% CI; 4.10, 8.00].

This study indicated that pregnant women who had attended tertiary education were eight times more likely to use substances during pregnancy than women who had no formal education [AOR = 8.15: 95% CI 4.24, 14.59]. Finally, pregnant women whose pregnancy was unplanned had twice higher odds of substance use than women whose pregnancy was planned [AOR = 1.87: 95% CI; 1.11, 2.89] (Table ).

4. Discussion

Prenatal substance abuse and/or dependent continues to be a significant problem in developing countries including Ethiopia and it may pose important health risks for the mother and the developing fetus (Behnke, Smith, et al., Citation2013; Louw, Citation2018). In this study, the prevalence of substance use among pregnant women is 48.1% [95%CI:39%, 62%], which is higher compared with the Ethiopian national survey (30.2%) (Addis et al., Citation2020), in Eastern Ethiopia (26.5%) (Fetene et al., Citation2021), in Butajira (35.8%) (Alamneh et al., Citation2020), in Addis Ababa (37.1%) (G. Tesfaye et al., Citation2020), in Gondar town(30.3%) (Addila et al., Citation2021b), and in Jimma (37.9%) (Tesso et al., Citation2017). This finding was also higher compared to studies conducted in Southeast Iran (15%) (Tabatabaei et al., Citation2018), South Africa (36.5%) (Petersen Williams et al., Citation2014), and Nigeria (22.6%) (Onwuka et al., Citation2016). This could be the cause of easy access to different substances, their availability, and the influence of social, cultural, and religious traditions that encourage the usage of the substance. However, this finding was similar to a study conducted in Southern Ethiopia (53.2%) (Wakgari et al., Citation2021).

This study reported that 37.6% (95% CI 33.3 to 42.1%) of pregnant women chewed khat which is higher than the systematic review of 22 studies conducted in Ethiopia (20%) (Bifftu, Citation2020) and other two studies conducted in Ethiopia 9.9% (Mekuriaw et al., Citation2020) and 31.2% (A. Y. Tesfaye et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, we found that 12.2% (95% CI 9.5 to 15.4) of pregnant women drank alcohol. Which is higher than studies conducted in Canada (6.7%) (Kar et al., Citation2021) and Mongolia (5.4%) (Erdenetuya et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, in this study, 12.6% (95% CI 9.9 to 15.9%) of pregnant women smoked a cigarette during the current pregnancy which is higher than studies conducted in African countries (2.9%) (Caleyachetty et al., Citation2014). The observed differences might be the variations in substance distribution, accessibility, manufacture, marketing, and other societal-cultural practices that may be responsible for disparities in substance use by geographical area.

This study revealed that pregnant women aged 25–34 years had greater odds of substance use during pregnancy compared to their counterparts. This finding is consistent with other studies conducted in Ethiopia (Haile et al., Citation2015; Wakgari et al., Citation2021) and elsewhere (Onwuka et al., Citation2016). Women at a younger age are prone to peer pressure and are highly sensitive to trying new things they have not tried in their lifetime. In addition, women at a younger age have also less experience in pregnancy-related physiological changes so they have a greater chance of substance use to control or avoid these pregnancy-related changes. Thus, pregnant women in the younger age group are highly likely to use substances during pregnancy compared to their counterparts.

This study indicated that pregnant women who had attended tertiary education were eight times more likely to use substances during pregnancy than women without formal education. This finding is similar to other studies conducted in Ethiopia (Addila et al., Citation2021b; G. Tesfaye et al., Citation2020; Tesso et al., Citation2017), and a study conducted in Nigeria (Onwuka et al., Citation2016). In Ethiopia, people who have attended tertiary education and above have a higher opportunity to work (Tessema & Zeleke, Citation2020). Besides, women who had attended tertiary education level are economically independent and have greater odds of being substance users than non-educated women.

In this study, pregnant women whose pregnancy was unplanned had twice higher odds of substance use compared to women whose pregnancy was planned. This finding is consistent with a review of 30 articles conducted in sub-Saharan countries (Addila et al., Citation2020), a study conducted in Iran (Tabatabaei et al., Citation2018), and other studies conducted in Ethiopia (Addila et al., Citation2021; Anteab et al., Citation2014a; Bitew et al., Citation2020). If the pregnancy is unplanned, pregnant women are less likely to seek care and counseling or any advice from health care providers or relatives regarding their pregnancy. In addition, they may also attempt different pregnancy termination methods, including traditional and unsafe methods that may include excessive substance use like alcohol consumption and other drugs. Thus, these women are more likely to use substances compared to those who have planned pregnancy status.

This study revealed that women who had four or more ANC visits were 56% less likely to use any substances during pregnancy than their counterparts. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Ethiopia (Tesso et al., Citation2017), and Southeast Iran (Tabatabaei et al., Citation2018). In general, pregnant women with four and above antenatal visits had a lower risk of substance use disorders because of the counseling and knowledge they received during their consecutive visits (Wong et al., Citation2011). Thus, women with the recommended number of ANC visits have a lower risk of substance use during their pregnancy period.

In this study, the odds of substance use during pregnancy was three times higher among women-headed households compared to the husband only headed. This finding is similar to a study conducted in health facilities of Oromia region in Ethiopia (Tesso et al., Citation2017). In Ethiopia, female-headed households are assumed to be the main source of income for the household. These women are also the potential decision maker for their personal and household issues as well. Therefore, these women have a greater chance of using substances for entertainment and medicinal purposes compared to households led by husbands only or both husband and wife equally.

This study indicated that women with substance-user husbands had six times greater odds of substance use during pregnancy than those women with non-user husbands. This finding is similar to a systematic review of 30 articles conducted in sub-Saharan countries (Addila et al., Citation2020), a study conducted in Iran (Tabatabaei et al., Citation2018), and other studies conducted in Ethiopia (Addila et al., Citation2021b; Anteab et al., Citation2014a; Fetene et al., Citation2021; Tesso et al., Citation2017). The person who is living with substance user household members is more likely to share the behavior of the family members. For example, if the husband is an alcohol drinker, his wife or other family member is more likely to be an alcohol drinker (Muluneh et al., Citation2021).

As a limitation, the study was based on self-reported information provided by mothers. Therefore, there is some potential for recall and reporting bias. Besides, social desirability bias is also likely as participants tend to answer the questions according to socially accepted manner. Finally, this study also shares the limitations of cross-sectional studies.

5. Conclusion

This study showed that nearly fifty percent of pregnant women were using substances (i.e., either alcohol, khat, or cigarette) during pregnancy, which is optimally high compared to the national figure. Maternal age, education level, unplanned pregnancy, number of ANC visits, husband substance use, and female head of the household were factors associated with substance use during pregnancy. The high prevalence of substance use (i.e., alcohol, cigarette, and khat) during pregnancy in the region calls for educational campaigns, screening, and targeted interventions for women of childbearing age.

Women were more likely to use substances during pregnancy if they were younger, had fewer ANC visits, had unplanned pregnancies, have a tertiary educational level, were Female-headed of the household, and had a partner who used substances. When designing primitive and preventive strategies, education and counseling of pregnant women at antenatal care-related services should be given due attention to combat the impact of substance use on the health of the mother and the development of the fetus. Furthermore, designing strategies that increase the communities’ awareness and participation in the risk reduction or prevention of the use of substances during pregnancy is required.

List of abbreviations

| ANC | = | Antenatal Care |

| AOR | = | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CI | = | Credible Interval |

| EDHS | = | Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey |

| LBW | = | Low Birth Weight |

| MCSE | = | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| PTB | = | Preterm birth |

| SGA | = | Small for Gestational Age |

| SD | = | Standard Deviation |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Authors’ contributions

All authors agreed to submit it to the current journal, gave final approval of the version that would be published, contributed significantly to its conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, participated in its writing or critically revised it for significant intellectual content, and agreed to be fully responsible for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

All materials and data related to this article are included in the main document of the manuscript. However, if anyone is interested to have raw data, he/she can contact the corresponding author.

Ethical issues and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS), Samara University (CMHS/0311/2021. The ethical approval letter was submitted to the concerned bodies. Oral informed consent was obtained from the patients before enrolment. Privacy and confidentiality were kept.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Samara University College of Medicine and Health Sciences for its ethical approval. Furthermore, our deepest gratitude goes to the community leaders, participants, data collectors, and supervisors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Setognal Birara Aychiluhm

Setognal Birara Aychiluhm graduated from University of Gondar with a Master of Public Health (MPH) in Biostatistics. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor of Biostatistics in the Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Samara University, Ethiopia. He is a coordinator of the Publication and Editorial Office of the University.

His areas of interest in study include infectious and non-infectious diseases, biostatistical models, maternal, neonatal, and child health.

References

- Addila, A. E., Azale, T., Gete, Y. K., & Yitayal, M. (2021a). The effects of maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy on adverse fetal outcomes among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 16(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00401-x

- Addila, A. E., Azale, T., Gete, Y. K., & Yitayal, M. (2021b). Individual and community-level predictors of maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A multilevel logistic regression analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 419. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03885-4

- Addila, A. E., Azale, T., Gete, Y. K., Yitayal, M., & Rota, M. (2021). Determinants of hazardous alcohol use among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A nested case-control study. PloS One, 16(7), e0253162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253162

- Addila, A. E., Bisetegn, T. A., Gete, Y. K., Mengistu, M. Y., & Beyene, G. M. (2020). Alcohol consumption and its associated factors among pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis’ as given in the submission system. Substance Abuse Treatment. Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00269-3

- Addis, N., Azage, M., Nigatu, D., & Kirksey, K. (2020). Alcohol use and its associated factors during pregnancy in Ethiopia: A population-based survey.

- Alamneh, A. A., Endris, B. S., Caffeine, G. S., Alcohol, K., & Abreu-Villaça, Y. (2020). and tobacco use during pregnancy in Butajira, South Central Ethiopia. PloS One, 15(5), e0232712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232712

- Anteab, K., Demtsu, B., & Megra, M. (2014a). Assessment of prevalence and associated factors of alcohol use during pregnancy among the dwellers of Bahir-Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014. Int J Pharma Sci Res, 5(12), 939–17.

- Anteab, K., Demtsu, B., & Megra, M. (2014b). Assessment of prevalence and associated factors of alcohol use during pregnancy among the dwellers of Bahir-Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014. Int J Pharma Sci Res Assess, 5(12), 939–946.

- Aychiluhm, S. B., Gelaye, K. A., Angaw, D. A., Dagne, G. A., Tadesse, A. W., Abera, A., & Dillu, D. (2020). Determinants of malaria among under-five children in Ethiopia: Bayesian multilevel analysis. BioMed Central Public Health, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09560-1

- Bayih, W. A., Belay, D. M., Ayalew, M. Y., Tassew, M. A., Chanie, E. S., Feleke, D. G., Asnakew, S., Legas, G., Belete, A., Mekie, M. & Yitbarek, G.Y. (2021). The effect of substance use during pregnancy on neonatal outcomes in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 7(4), e06740.

- Behnke, M., Smith, V. C., Levy, S., Ammerman, S. D., Gonzalez, P. K., Ryan, S. A., Gonzalez, P. K., Ryan, S. A., Smith, V. C., Wunsch, M. M. J., Papile, L. A., Baley, J. E., Carlo, W. A., Cummings, J. J., Kumar, P., Polin, R. A., Tan, R. C., & Watterberg, K. L. (2013). Prenatal substance abuse: Short-and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics, 131(3), e1009–24. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3931

- Behnke, M., VC, S., CoS, A., Co, F., Newborn, B. M., Ammerman, S. D., Gonzalez, P. K., Ryan, S. A., Smith, V. C., Wunsch, M. M. J., Papile, L. A., Baley, J. E., Carlo, W. A., Cummings, J. J., Kumar, P., Polin, R. A., Tan, R. C., & Watterberg, K. L. (2013). Prenatal substance abuse: Short-and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics, 131(3), e1009–24. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3931/

- Bernstein, J., Derrington, T. M., Belanoff, C., Cabral, H. J., Babakhanlou-Chase, H., Diop, H., Evans, S. R., Jacobs, H., & Kotelchuck, M. (2015). Treatment outcomes for substance use disorder among women of reproductive age in Massachusetts: A population-based approach. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 147, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.025

- Bifftu, B. B. (2020). Prevalence of khat chewing during pregnancy in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Birara Aychiluhm, S., Mohammed, E., Altaye, H., Urgessa, K., Mare, K. U., Tadesse, A. W., & Yilma, F. (2022). Tuberculosis Co-infection and Associated Factors among People Living with HIV/AIDS Who are on Antiretroviral Therapy in Pastoral Community, Northeast Ethiopia. A Bayesian Analysis Approach. Cogent Public Health, 9(1), 2145700. https://doi.org/10.1080/27707571.2022.2145700

- Bitew, M. S., Zewde, M. F., Wubetu, M., Alemu, A. A., & Washio, Y. (2020). Consumption of alcohol and binge drinking among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Prevalence and determinant factors. PloS One, 15(12), e0243784. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243784

- Caleyachetty, R., Tait, C. A., Kengne, A. P., Corvalan, C., Uauy, R., & Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B. (2014). Tobacco use in pregnant women: Analysis of data from Demographic and Health Surveys from 54 low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Global Health, 2(9), e513–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70283-9

- Contreras, L. F., Brown, E. T., & Ruest, M. (2018). Bayesian data analysis to quantify the uncertainty of intact rock strength. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 10(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2017.07.008

- Crome, I. B., & Kumar, M. T. (2007). Epidemiology of drug and alcohol use in young women. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 12(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2006.12.002

- Dargie, A., Eshetie, Y., Asmare, Y., Shibabaw, W., & Dagne, K. (2019). Prevalence of Alcohol use during pregnancy and its association with partner alcohol use in East Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. bioRxiv [Internet], 687467.

- Day, N. L., Wagener, D. K., & Taylor, P. M. (1985). Measurement of substance use during pregnancy: Methodologic issues. NIDA Research Monograph, 59, 36–47.

- Erdenetuya, B., Kwon, D., Choi, S., & Choe, S. A. (2022). Alcohol use during pregnancy: Findings from a gender-based violence survey in Mongolia. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(4), 789–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01242-8

- Fetene, M. T., Teji, K., Assefa, N., Bayih, W. A., Tsehaye, G., & Hailemeskel, H. S. (2021). Magnitude and associated factors of substance use among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public hospitals of eastern Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03078-5

- Forray, A. (2016). Substance use during pregnancy.

- Haile, D., Lakew, Y., & Fernandez-Reyes, D. (2015). Khat chewing practice and associated factors among adults in Ethiopia: Further analysis using the 2011 demographic and health survey. PloS One, 10(6), e0130460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130460

- Humeniuk, R., & Ali, R., (2006). World Health Organization APIISG: Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and Pilot Brief Intervention [Electronic Resource]: A Technical Report of Phase II Findings of the WHO ASSIST Project/Prepared by Rachel Humeniuk & Robert Ali, on Behalf of the WHO ASSIST Phase II Study Group, 24(3), 217–226.

- Kar, P., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., Giesbrecht, G., Bagshawe, M., & Lebel, C. (2021). Alcohol and substance use in pregnancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 225, 108760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108760

- Keane, R. Understanding substances and Substance use: A handbook for teachers. 2006.

- Kotelchuck, M., Cheng, E. R., Belanoff, C., Cabral, H. J., Babakhanlou-Chase, H., Derrington, T. M., Diop, H., Evans, S. R., & Bernstein, J. (2017). The Prevalence and Impact of Substance Use Disorder and Treatment on Maternal Obstetric Experiences and Birth Outcomes Among Singleton Deliveries in Massachusetts. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(4), 893–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2190-y

- Kynn, M. (2005). Eliciting expert knowledge for Bayesian logistic regression in species habitat modelling. Queensland University of Technology.

- Lange, S., Probst, C., Heer, N., Roerecke, M., Rehm, J., Monteiro, M. G., Shield, K., de Oliveira, C., & Popova, S. (2017). Actual and predicted prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 41, e89. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2017.89

- Lester, B. M., Andreozzi, L., & Appiah, L. (2004). Substance use during pregnancy: Time for policy to catch up with research. Harm Reduction Journal, 1(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-1-5

- Louw, K. -A. (2018). Substance use in pregnancy: The medical challenge. Obstetric Medicine, 11(2), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X17750299

- Macleod, C. I., Young, C., & Molokoe, K. (2021). Alcohol use during pregnancy: Prevalence and patterns in selected Buffalo City areas, South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 25(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i1.13

- Mekuriaw, B., Belayneh, Z., & Yitayih, Y. (2020). Magnitude of Khat use and associated factors among women attending antenatal care in Gedeo zone health centers, southern Ethiopia: A facility based cross sectional study. BioMed Central Public Health, 20(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8026-0

- Muluneh, M., Francis, L., Agho, K., & Stulz, V. (2021). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Associated Factors of Gender-Based Violence against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094407

- Nakajima, M., Jebena, M. G., Taha, M., Tesfaye, M., Gudina, E., Lemieux, A., Hoffman, R., & al’Absi, M. (2017). Correlates of khat use during pregnancy: A cross-sectional study. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.008

- Onwuka, C. I., Ugwu, E. O., Dim, C. C., Menuba, I. E., Iloghalu, E. I., & Onwuka, C. I. (2016). Prevalence and predictors of alcohol consumption during pregnancy in South-Eastern Nigeria. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 10(9), QC10. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/21036.8449

- Organization, W. H. (2010). Atlas on substance use (2010): Resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. World Health Organization.

- Organization, W. H. (2014). Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy.

- Petersen Williams, P., Jordaan, E., Mathews, C., Lombard, C., & Parry, C. D. (2014). Alcohol and other drug use during pregnancy among women attending midwife obstetric units in the Cape Metropole, South Africa. Advances in Preventive Medicine, 2014, 1–10. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/871427

- Popova, S., Lange, S., Probst, C., Shield, K., Kraicer‐melamed, H., Ferreira‐borges, C., & Rehm, J. (2016). Actual and predicted prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy in the WHO African Region. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 21(10), 1209–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12755

- Ruisch, I. H., Dietrich, A., Glennon, J. C., Buitelaar, J. K., & Hoekstra, P. J. (2018). Maternal substance use during pregnancy and offspring conduct problems: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.014

- Shankaran, S., Lester, B. M., Das, A., Bauer, C. R., Bada, H. S., Lagasse, L., & Higgins, R. (2007). Impact of maternal substance use during pregnancy on childhood outcome. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 12(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.002

- Shanmugam, P. (2017). The Influence of Social Factors in Drug Addiction–A Mini Review of Work by Miller & Carroll (2006). Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence, 5(04), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6488.1000272

- Tabatabaei, S. M., Behmanesh-Pour, F., Salimi-Khorashad, A., Zaboli, M., Sargazi-Moakhar, Z., & Shaare-Mollashahi, S. (2018). Substance abuse and its associated factors among pregnant women: A cross-sectional study in the southeast of Iran. Addiction & Health, 10(3), 162.

- Tesfaye, G., Demlew, D., Habte, F., Molla, G., Kifle, Y., Gebreegziabhier, G., & Gebreegziabhier, G. (2020). The prevalence and associated factors of alcohol use among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public hospitals Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02747-1

- Tesfaye, A. Y., Gudina, E., Berhanu, S., & Dadi, M. (2020). Khat chewing in pregnant women associated with prelabor rupture of membranes, evidence from eastern Ethiopia. PAMJ, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2020.36.1.22528

- Tessema, Z. T., & Zeleke, T. A. (2020). Spatial distribution and factors associated with Khat chewing among adult males 15-59 years in Ethiopia using a secondary analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. Psychiatry Journal, 2020, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8369693

- Tesso, F. Y., Woldesemayat, L., & Kebede, D. B. (2017). Magnitude of substance use and associated factors among pregnant women attending jimma town public health facilities, Jimma Zone, Oromia Regional State Southwest Ethiopia. Clinics Mother Child Health, 14(275), 2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2090-7214.1000275

- Thomas, S., Treffers, R., Berglas, N. F., Drabble, L., & Roberts, S. C. (2018). Drug use during pregnancy policies in the United States from 1970 to 2016. Contemporary Drug Problems, 45(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918790790

- Wakgari, N., Woyo, T., Kebede, E., Gemeda, H., Binu, W., Moti, G., & Roy, V. (2021). Substance Use among Homeless Reproductive Age People in Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 2021, 8272986. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8272986

- Whittaker, A. Guidelines for the Identification and Management of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders in Pregnancy by World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, (2014) ISBN: 9789241548731, 224 pp. Available free online http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/pregnancy_guidelines/en.WileyOnlineLibrary; 2015.

- Wong, S., Ordean, A., Kahan, M., Gagnon, R., Hudon, L., Basso, M., Bos, H., Crane, J., Davies, G., Delisle, M. F., Farine, D., Menticoglou, S., Mundle, W., Murphy-Kaulbeck, L., Ouellet, A., Pressey, T., Roggensack, A., Sanderson, F., Ehman, W. , and de la Ronde, S. (2011). Substance use in pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 33(4), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34855-1

List of Tables

: Graphical assessment for convergence algorism of significant independent variables

Table A1. Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women in pastoral community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia

Table A2. Medical and obstetric related factors among pregnant women in pastoral community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia

Table A3. Behavioral characteristics of substance use during pregnancy in pastoral community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia

Table A4. Bayesian logistic regression to identify predictors of maternal substance use during pregnancy in pastoral community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia