Abstract

: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is a major public health hazard on a global scale. It is a kind of tuberculosis (TB) infection produced by bacteria resistant to at least two of the most effective first-line anti-tuberculosis (anti-TB) drugs: isoniazid and rifampicin. In numerous health care facilities around Uganda, MDR-TB patients have bad experiences. The purpose of this study was to investigate the lived experiences of female patients aged 15 to 49 years receiving treatment for MDR-TB at Lira Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. Using a method of purposive sampling, a phenomenological qualitative study was done among female patients aged 15 to 49 receiving treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at Lira Regional Hospital. Data was collected using an English-translated Lango guide for in-depth interviews. Data was entered manually and analyzed using version 13 of the qualitative program NVIVO. It was discovered that the spouses of female MDR-TB patients lacked social support. Female patients with a history of tuberculosis prior to MDR-TB had stronger family support systems. MDR-TB diagnosis was strongly related with shock, anxiety, and denial. The majority of patients indicated that proper information on probable side effects allowed them to successfully complete MDR-TB treatment. Compared to other health centres in the district, the MDR-TB services at Lira Regional Referral were easily accessible and staffed by friendly medical personnel. In conclusion, female patients receiving MDR-TB treatment represent a unique population, and family support and care had a significant impact on the success of MDR-TB treatment among them.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by bacteria and spread from person to person through air. It affects the lungs and other parts of the body (brain, kidneys or spine). Many times, TB is treatable and curable; however, persons with TB can die if they do not get proper treatment. The bacteria can become more resistant to treatment when not properly managed; hence Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) or even extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB). MDR-TB is caused by TB bacteria that are resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs whereas extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB) is a rare type of MDR-TB that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of the three injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin). In this study we looked at lived experiences of female patients undergoing treatment for MDR-TB.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background to the study

MDR-TB is defined as Tuberculosis (TB) that is resistant to at least the two most potent first-line anti-TB drugs (Rifampicin and Isoniazid) (WHO, Citation2016a Citation2016b; Omona & Opiyo, Citation2023). Remarkably, there were an estimated 480, 000 new cases of MDR-TB and roughly 190,000 deaths from MDR-TB worldwide in 2014, with more than half of these cases occurring in poor nations (World Health Organisation, Citation2015).

Globally, less than fifty percent of MDR-TB patients complete their treatment. This is primarily owing to the lengthy period of treatment, frequently 24 months or longer, and secondarily to medication toxicity (World Health Organisation, Citation2015), which leads to poor treatment adherence. Moreover, psychosocial concerns frequently aggravate MDR-TB, considering the treatment’s complexity and length (Shanmugam & Dobler, Citation2016; Walker et al., Citation2015). n many African countries, the treatment of MDR-TB consumes more than half of the national TB control program budget and threatens the effectiveness of national TB control programmes. However, several other factors, such as the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, low socioeconomic status, and limited diagnostic and treatment facilities, greatly exacerbate the impact of MDR-TB in the developing world (Shanmugam & Dobler, Citation2016). In addition, the programmatic management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is complicated by up to two-year treatment regimens and costly, toxic medications (Calver & Molapo, Citation2010).

Uganda remains a high-burden nation, with MDR-TB accounting for 1% of new cases and 12% of previously treated cases. With the high prevalence of MDR-TB and RR-TB, timely diagnosis, therapy initiation, and patient adherence are crucial. The treatment for MDR-TB is tough, complex, and lengthy (Ahmad et al., Citation2019; World Health Organisation, Citation2019).

The treatment for MDR-TB is protracted, sometimes accompanied by severe side effects, and fraught with adherence issues (Munro et al., Citation2017). Adherence to medical treatment is a complex behavioural issue that is influenced by numerous context-specific variables (Toczek et al., Citation2018). In the therapy of MDR-TB, poor adherence might have medical and public health consequences (Batte et al., Citation2021; Lönnroth et al., Citation2016).

The disease’s prevalence is great and it is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Individual characteristics (sex, age, level of education), behavioural issues (smoking, alcohol, substance abuse), clinical factors (HIV, diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, or other associated disease), a history of previous treatment, type resistance, access to quality and resolute health services, social protection, compensatory policies, income transfer, and improvements to the social context continue to be the most important determinants of MDR-TB.

According to a recent study by (Batte et al., Citation2021) and a similar study (Katende & Omona, Citation2021) conducted at the Mulago National Referral Hospital in Uganda, 12% of previously treated TB cases and 1.6% of new cases required specific therapy and care for MDR-TB. 39.4% of the 227 patients with MDR-TB who met the inclusion criteria were female (Batte et al., Citation2021).

Women who undergo MDR-TB treatment continue to be more susceptible to mental and social distress than men. Married women and women of reproductive age are especially susceptible to the social, economic, and mental health consequences of MDR-TB, such as social isolation, financial struggle, and depression (Mishra et al., Citation2017). Psychosocial difficulties frequently complicate MDR-TB, given the treatment’s intricacy and length (Walker et al., Citation2015).

Women and mothers with all linked MDR-TB treatment variables have reproductive and maternal functions that exacerbate their coping abilities, non-adherence, and treatment results. The likelihood that a female patient is a wife or mother who provides essential family support and care for their spouses and children, including any other family members with MDR-TB. Socially, it is regarded as a woman’s maternal duty to care for ailing family members, but in some cases, when a woman is ill, she is denied basic support from her husband and family (Mishra et al., Citation2017).

In order to generate research that can influence and guide the development of programmes and initiatives to enhance adherence patterns, MDR-TB treatment results, and ultimately end tuberculosis, it is crucial to assess the lived experiences of MDR-TB patients, particularly women of reproductive age. Treatment and adherence are determined by the social milieu that determines MDR-TB patients’ life experiences. Poverty is regarded as both the cause and effect of tuberculosis relapse and poor treatment outcomes. Against this backdrop, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the lived experiences of female patients’ aged 15–49 getting treatment for MDR-TB at Lira Regional Referral Hospital.

1.2. Conceptual framework

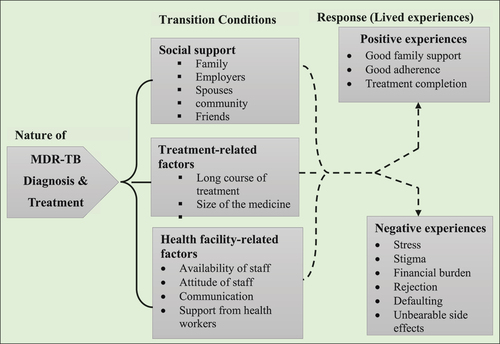

The diagnosis and treatment can transition into either positive lived experiences or negative lived experiences for patients. Positive experiences are associated with a strong family support system, treatment adherence, and treatment completion, whereas negative experiences are associated with stress, burden, stigma, and treatment noncompliance, among others. As indicated in Figure , the transition can be influenced by a number of factors, including social supports, treatment-related factors, and health facility-related factors.

1.3. Research questions

The study had four research questions;

What were the social lived experiences of female patients aged 15-49 years undergoing Treatment for Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in Lira Regional Referral Hospital?

What were the transitions conditions of female patients aged 15-49 years undergoing Treatment for Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in Lira Regional Referral Hospital?

What were treatment adherence lived experiences among female patients aged 15-49 years undergoing treatment for Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in Lira Regional Referral Hospital?

What were the health facility services lived experiences among female patients aged 15-49 years undergoing treatment for Multi-Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in Lira Regional Referral Hospital?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This was a qualitative phenomenological investigation. We chose this strategy within the qualitative paradigm to structure this research because it enables an understanding of the complex and subjective meanings that arise through time for different individuals and groups in certain social circumstances (Neubauer et al., Citation2019). According to this research objective, phenomenological qualitative research designs are particularly beneficial for determining the significance that individuals assign to the experiences they encounter.

2.2. Study area

The study was done at the Lira Regional Referral Hospital. The Lira Regional Referral Hospital is situated in the heart of the city of Lira. It serves as the referral hospital for Amolatar, Apac, Dokolo, Lira, Alebtong, Otuke, Kole, and Oyam districts. The hospital is situated along Police Road in the central business sector of Lira city, approximately 342 kilometres (213 miles) north of Kampala, the capital of Uganda, via road.

2.3. Study population

Study population refers to an aggregate of people or things that a researcher has in mind from which one can obtain information and draw conclusions. Such population shares several common features. In this study, the target population was female patients undergoing MDR-TB treatment in Lira Regional Referral Hospital.

2.4. Sample size determination

15 female patients with MDR-TB participated in this study. This sample size was established once the data being gathered had reached saturation.

2.5. Study variables

Figure depicts the link between the independent variables of social support, treatment-related factors, and facility-related factors and the dependent variable of female patients getting treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and their lived experiences.

2.6. Data collection tools and methods

The primary instrument used to collect qualitative data was the guide for in-depth interviews. Patients who came to the facility for therapy were permitted to engage in IDIs at times that were convenient for them. Consent was sought from participants who met the conditions and were willing to participate. Participants were selected using a technique of purposive sampling. The MDR-TB Unit at the Lira Regional Referral Hospital admits patients with MDR-TB, monitors them for at least two months while they stabilise, and then prepares them for community integration. At the time the data was collected, the clinic had an average of 56 outpatients and 20 inpatients. Wednesdays are designated clinic days for outpatients to refill and evaluate their medications.

The study utilised the Unit Register to identify female patients who were eligible to participate. On Wednesdays during clinic days, the sample was conducted for three consecutive weeks. The study recruited female patients with MDR-TB who have been receiving treatment for at least two months, are at least 18 years old, can communicate, and are willing to participate.

To ensure the capture of high-quality, error-free data, the principal investigator emphasized careful control throughout the whole data collection process. Following data collection and pre-coding of the interview guide with open-ended questions, all filled-out tools were reviewed daily for consistency. For the details of the in-depth interview guide used in this study, see appendix attached to this publication.

2.7. Data entry, analysis and presentation

The taped interviews have been transcribed word-for-word. Before the transcripts were uploaded into NVivo version 13 for analysis, they were read aloud multiple times and grammar errors were corrected. Combining deductive and inductive methodologies, a thematic analysis was conducted. Each interview was coded using an unique coding scheme to ensure the privacy of all participants.

The first step involved a quick assessment of each work in order to form an impression and generate ideas for a more in-depth analysis. The second phase consisted of structural analysis, which revealed the text’s arrangement and internal relationships and enabled the identification of meaningful sentences.

The third phase involved gaining knowledge of the interpreted whole by reflection on the superficial reading and structural analysis. From each transcript, significant statements directly connected to the experience of MDR-TB treatment were extracted. The significant assertions served as the foundation for constructing meanings. The produced meanings were sorted into themes, which allowed the production of motifs that appeared in the transcripts of all participants. The findings were incorporated in a comprehensive and comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon. This was achieved by opening each transcript in the NVivo application and line-by-line reading and coding each statement. After examining the coding, subthemes and themes were created by rearranging and merging codes. A codebook was developed, major and minor themes were identified, and a table of themes was compiled. In addition, each code was converted back to Word for easy reading, and the best quotes were selected for inclusion in the work’s content.

2.8. Ethical approval statement

The investigators conceived the idea and designed the study protocols. The protocols were initially approved by the Uganda Martyrs University research ethics committee and later approved by Mulago Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Ref. no: MHREC 2152). An official letter that explained the objectives, rationale and expected outcomes of the study was written to the Lira Regional Referral Hospital (LRRH) administration. Administrative clearance was then granted by the hospital director. We then recruited patients into the study at data collection stage and obtained primary data. We obtained written consent from the MDR-TB clinic as well as from individual patients who participated in the study. The respondents were assured that their information would be kept confidential and thus, confidentially was maintained at all levels.

2.9. Study limitations

Given that the study was qualitative, conclusions about the entire country (Uganda) cannot be drawn from it. Despite the fact that the investigators made great attempts to eliminate all possible sources of bias, if there were any shortcomings, information recall bias or bias related to interpreting the questions, could have still affected our results

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

Fifteen female MDR-TB patients participated in the in-depth interviews. Participants interviewed had undergone treatment over a range of 2 to 36 months, with a mean of 9 months. The participants’ ages ranged from 15 to 60, with a mean age of 34.9 years. Eight of the individuals were older than 30 years. The bulk of respondents, consisting of thirteen individuals, were unemployed peasant farmers, six of whom identified as Catholic and six of whom had completed only primary education. More than six months had passed since the initiation of MDR-TB treatment for nine patients. Twelve individuals were married and shared a residence with their spouses. For details, check Table .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the respondents

3.2. Codes/Themes that emerged from the interviews

A number of codes (themes and sub-themes) emerged from the interviews. Summary is shown in Table .

Table 2. Showing the codes/themes that emerged from the interviews

3.3. Social lived experiences of female patients undergoing treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

3.3.1. Theme 1: Social experience

The social lived experiences generated the following sub-themes; social support, discrimination, stigmatization, social functioning, and a person’s awareness of the patient’s TB status and family support.

3.3.1.1. Sub-theme I: Social support

According to the patients, there were numerous sources of emotional support, with family being the most frequent. During the course of their MDR-TB diagnosis and treatment, some patients reported enjoying acceptance and affection in their relationships. Some of the patients got support because they were not the first person to have suffered from TB in the family or their first time suffering from TB.

“My family’s encouragement helped me to get through this worst time in my life…” (P-9)

“… My first born all suffered TB – all the five family members suffered from TB …” (P-2)

“… My mum had TB, so it was not new at all, they were actually helping with buying soap, and other things I need, and talking to me gave hope. …” (P-3)

“… They started feeling bad but accepted me because I was their family member. … (P-2)”

“… Supported me throughout since I had TB before. …” (P-7)

“… No one was surprised because my father had TB before …” (P-10)

Most patients had strong family or social support in order to deal with or effectively manage the stress, worry, or despair that one is experiencing. The patients reported that having support from their families was essential to managing the symptoms of MDR-TB.

“… I think I can pass bad situation because I have many good things around me, my family encouraged me to fight with the disease …” (P-7)

“… . Encouragements from my family were the most powerful support for me. I had TB before and was then cured. Then, I developed MDR-TB. My family helped me to face the disease again. At first, I felt so much fear. Now, I am not afraid …” (P-2)

“… Providing with food and 20,000 from the facility only, no help from other sources … .” (P-2)

“… Children support me on food and transport to the facility even praying and talking to me, helping me with home chores … .” (P-7)

“… My family helps me work these days because If I work a little bit or carry 10–20 kg of weight then within few minutes I start feeling breathlessness. I cannot help with anything at home, even not in household chores. But am glad my mother and sisters help me with the home chores and I don’t have to do too much work … .” (P-5)

“….I don’t do garden work since I don’t have energy since I started the medication” …(P-3)

On the other side, others received inadequate social support from their spouses and families to effectively control their anxiety. They indicated that family members feared disease transmission and prevented MDR-TB patients from meeting them.

“My husband did not support me, he was alcoholic. He was not responsible for the family.” (P-2)

“… At first, my sister did not permit me to use her stuff after I was diagnosed with MDR-TB, so I had to get my utensil after the health workers had explain everything to my family-sister I stay with …” (P-1)

3.3.1.2. Sub-theme II: Discrimination.

Many of the patients reported such experiences of rejection towards MDR-TB patients. They reported that the rejection varied from separating Patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis must isolate their belongings from those of others until the completion of therapy, going so far as to live in separate dwellings. The patients also reported a lack of participation in social meetings due to their bad health; they avoided social events as a result of their poor health.

“… . Since I was known to have MDR-TB drugs, people whom I used to live with were not happy to be with me in the same area or same room. I was left to live alone and I did not have a good feeling at that time …” (P-4)

“… . But what I observed in my office was total discrimination against the sick. They tend to leave the whole office when I come in and that has given me a very bad feeling. I believe such practice may affect treatment-seeking of other people who may have as for me I had to leave my job because of being diagnosed with MDR-TB …” (P-1)

“… . People fear you and isolate you in fear of contracting MDR-TB …” (P-1)

3.3.1.3. Sub-theme III: Stigmatization

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is often stigmatized, which discourages MDR-TB patients. The stigma arose from the fear that MDR-TB patients would transmit the disease to family members and other members of the community. This was especially the case due to the association between tuberculosis and HIV, as the community believed that everyone with tuberculosis is HIV-positive, and drug-resistant TB was always connected with discontinuing antiretroviral therapy (ART). Some patients hid the fact that they had MDR-TB out of fear of stigmatization, causing them to isolate themselves.

“… Relate TB with HIV, most people think it’s not TB, its HIV …” (P-1)

“… People around me who knew that I had MDR-TB, they treated me as I am a disgusted person. When they gazed at me, I felt being stigmatized … .” (P-3)

“… . People in the community did not know that I have the disease. I did not tell them because they will reject me. I did not participate in any community events. I stayed only at home … … .” (P-3)

“… . They felt bad almost chase me from home, came to the hospital in 6 months and go back. The community said she had refused to take her ART; some people understand and others are not …” (P-1)

3.3.1.4. Sub-theme IV: Persons aware of your TB status

This sub-theme was about people and community members who are not informed about the patient’s status. Most of the patients mentioned that family member and few other people knew their status

“… My sister wanted to chase her away due to influence from the family members” (P-1)

“… Family members and a brother …” (P-1)

“… My family member only …” (P-11)

“… Aunt, family, all relatives, friends. Some of them cannot allow me to get close to them. People say I will die in one week …” (P-7)

“… Very few people know about my condition …” (P-14)

“… Family and a neighbor …” (P-6)

3.4. Transitions conditions of female patients undergoing treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

3.4.1. Theme 2: Transitions conditions

3.4.1.1. Sub-theme I: Awareness of the severity of the disease

A number of patients voiced their opinion that the staff at the clinic had provided them with sufficient information regarding their therapy and what they may anticipate during the course of their treatment. Patients mentioned that they did not know what to expect during therapy as a barrier to treatment completion, but they did not identify knowledge as a facilitator during treatment.

“… . I just felt like vomiting and since the nurse had told me before that it can happen, I was not surprised and then it passed with time. Since I was okay whenever I took them, I just continued taking them …” (P-4)

“… Yes, MDR-TB, depends on how you follow the medication guidelines, you can do for months, 18 months or even more. When I came, I was badly off, only 27kg, but now I am 45 kg … .” (P-1)

3.4.1.2. Sub-theme II: Condition burden

When a patient learns the details of his tuberculosis sickness, particularly if it is MDR-TB, all hope of a healthy recovery quickly dissipates since they believe it to be an incurable and fatal condition.

“… . a few months back, my physical condition worsened too much and I was not able to stand or walk for my daily necessity, I needed somebody’s help … …” (P-9)

3.4.1.3. Sub-theme III: Determination to be cured

Each patient stated that they were prepared to do whatever was necessary in order to get healed of their tuberculosis and get their health back on track so that they could return to a normal life.

“… Because I want to get well to be able to take care of my children, then I have to do what I am told to get well. Taking the treatment is the way to get well, so that is why I must do it … .” (P-1)

3.4.1.4. Sub-theme IV: Emotional and psychological challenges

The diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) may have implications for a person’s physical and mental health as well as their social and financial standing. Fear, pessimism, sadness, anxiety, and depression were just some of the negative attitudes that the patients reported having toward their MDR-TB condition. After understanding that the sickness could be easily passed from one person to another, people’s already poor sentiments toward it became much more negative.

“I thought I had only a 50% chance or even less to be cured. I feel hopeless and so difficult. The health workers told me that I needed at least 6 months or more of treatment, but 2 years have passed … nowadays, I am still not fully recovered. This made me worried that I will die soon.” (P-3)

“For me, the disease is disgusting. I annoy myself and I always think about taking overdose medication to kill myself. I did not want to put my sister into trouble.” (P-8)

3.4.1.5. Sub-theme V: Experience at the time of diagnosis

When asked about their reactions, the majority of patients expressed feeling bewildered, afraid, and astonished when they initially learned of the diagnosis.

“… . I was shocked at knowing about the diagnosis results, and I felt a lot of stress. I did not to go to school, wanted to drop my studies …” (P-6)

“… I was confused when the health workers told me that I had MDR-TB illness … I felt chaos in my head and felt like unable to breathe … .” (P-12)

“I am sure that I will get a successful treatment. I protected others by wearing a mask and separated all things from them … dishes, spoons … but I still sleep with my spouse … he does not want to separate from me.” (P-14)

Some patients had suicidal thoughts when they were in the intensive phase of treatment, but when they were interviewed, the patients felt that the most difficult parts of their lives were behind them.

“….Why do people feel disgusted when they see me? They do not show interest in me. I have had thoughts about ending myself; I did not want myself to burden anybody else.” (P-11)

“… . At first, I thought it was just an ordinary cough that will soon go away. So, I took some cough medication and I waited for it to stop. When it got to one month and I was still coughing, I knew it was something serious so I had to go to the health center where I was referred here (Lira Regional Referral Hospital) after the test … .” (P-7)

Some participants had previously been diagnosed with tuberculosis and were undergoing treatment for MDR-TB.

“… It was not the first time that I have had tuberculosis. I had it before and took the treatment … .” (P-13)

3.4.1.6. Sub-theme VI: Experiencing better health

All the patients reported that the commencement of treatment improved their health.

“… . I am much better now as I am gaining weight and eating well now. I have been getting better since I started taking the treatment … .” (P-3)

3.4.1.7. Sub-theme VII: Reason(s) for seeking treatment

When the symptoms of tuberculosis grew intolerable, the majority of the patients opted to seek therapy so that they may find a cure for the disease. Others only went to the hospital after failing to get better after other treatments like us of the over-the-counter medication or herbal remedies.

“… . I was weak and I couldn’t eat. I went to the health center and after the test, I was told that I have tuberculosis and to be specific MDR-TB which the doctor told me is not the normal TB I had before” (P-10)

“… I did not know but got to know from home when they tested and found MDR- and was retained in the ward for one month and went home and come back every day to take medication … .” (P-9)

“… I mean when I started having the signs of tuberculosis, I didn’t know what it was. I was having night sweat and no appetite. Then I was told that I have tuberculosis after I did the test …” (P-7)

“… . I decided to come because I had chest pain, weakness, heat and cough. I knew it was TB but did not know it was MDR … .” (P-11)

“… Cough frequently, tiredness, cough blood for 2 weeks, heat/fever, chest pain, difficulty in breathing, coughing, numb feet …” (P-4)

3.4.1.8. Sub-theme VIII: History leading to a diagnosis

History of diagnosis appeared as one of the sub-themes, and it was comprised of the reasons for seeking treatment, the experience of being diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the reaction to the diagnosis at the prior occasion as nearly half of the participants had suffered from TB in the past.

“… It started in 2020, cough, tried taking medication for 2 weeks but I was not getting better, I went to the Bala H/C when I was tested and diagnosed with TB. Started treatment for one year …” (P-1)

“… Had TB and treatment for 6 months and after 4 months – consistent, persistent cough, so I decided to go test and I was referred …” (P-2)

“… Coughing blood, I came to the facility, the sample was taken (sputum, blood, and x-ray) …” (P-6)

“… Testing since I have suffered from TB before …” (P-8)

“… . They took my sample at the facility, and then called my dad after some days to tell him I have MDR-TB then I was referred to the center and told it was MDR hence brought to the center …” (P-13)

“… I was retested and told it was MDR from the health center, because of serious cough, chest pain, and bloody eye …” (P-14)

“… . Coughing and I was not feeling improving despite being on medication …” (P-15)

“… I went to Aboke H/C IV then started TB treatment for six months with no improvement then I was transferred here …” (P-3)

3.4.1.9. Sub-theme IX: Hope and improvement in health

Within a few days of beginning the appropriate treatment, the patient begins to experience an improvement in his overall health, as well as an improvement in daily activities such as eating, sleeping, and symptom relief. Many of the interviewees reported their favorable experiences with medication and specifically mentioned.

“… They see improvement and get surprised …” (P-1)

“… After taking medication there is a lot of improvement. Now I do not have body aches and my appetite is improved. These days, I eat more and also no cough or breathlessness, as I used to have before … …” (P-7)

“… . Now when I go to bed in the night, I wake up directly in the morning, but earlier, I used to cough the whole night because of which I was not able to sleep at night … .” (P-5)

3.4.1.10. Sub-theme X: Knowledge about MDR-TB and treatment

The majority of patients claimed that they had never skipped treatment for MDR-TB because they were adequately informed about the disease. All of these individuals received health education at healthcare facilities, complied with health recommendations, and are aware of the risks of discontinuing treatment.

“… The doctor told me and then he explained to me all that I had to do to be cured. I started taking the treatment and I have never missed a day … .” (P-6)

3.4.1.11. Sub-theme XI: Worries

MDR-TB patients were concerned about their ability to financially support themselves after leaving the centre where they receive free accommodation and food. This is because the center provides meals and centers for the patients for one month or two months depending on how the patient is improving before being discharged to the outpatient clinic. Some patients were also worried about death from the disease.

“… . My father was the first one to suffer from TB, then my mother got this illness and now I got this disease. It is persisting in my family, my father died because of this disease …” (P-14)

3.4.1.12. Sub-theme XII: Reaction to diagnosis

More than half of the participants were astonished by the diagnosis but accepted it quietly, whereas a few participants were unhappy or upset about it. Some patients expressed sadness and even disputed having tuberculosis.

“… .Well I was not coughing, but I was losing weight and did not have an appetite. After the test, I was diagnosed with tuberculosis. I was surprised to hear that … …” (P-13)

“… When for the first time I got the result of the test and came to know that I am suffering from the TB disease, I felt as if the ground was slipping beneath my feet … .” (P-13)

3.5. Treatment adherence lived experiences among female patients undergoing treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

3.5.1. Theme 3: Treatment-related experiences

3.5.1.1. Sub-theme I: Financial burden

One significant sub-theme that emerged from the interviews is the financial struggles faced by MDR-TB patients, particularly those who are poor because the illness state substantially impairs their quality of life.

Patients found it challenging to receive the right care due to a lack of access, lengthy travel times, and distances to the healthcare facility. Patients must travel to an MDR-TB centre distant from the village or district hospital to begin MDR-TB therapy, which results in significant out-of-pocket costs. Numerous patients in the lower MDR-TB centre complained about both the cost burden and the inadequate facilities.

3.5.1.2. Sub-theme II: Indirect cost

In Uganda, MDR-TB treatment is free of direct costs, which means that anti-MDR-TB medications and lab tests are not charged. However, there are secondary costs, such as those associated with feeding and transportation. It is tough and expensive for DOTs to travel each morning from far-off villages to health facilities. To minimize the difficulty of daily travel to the medical facilities, some patients decided to relocate and reside with family close to the treatment facilities. Thus, this represents another another indirect expense for the patients. These challenges have a negative impact on other suspected MDR-TB patients’ health-seeking behaviour, which delays the discovery of new cases.

“…We spent around 3,000 Ugx per visit to the health facility for treatment and had to visit regularly for months. But at some point, I stopped treatment as I had no money to go there regularly, especially during COVID until my uncle accepted me to move to his place living my child in the village. I have been here of three months and things are taking shape with my health ….” (P-10)

3.5.1.3. Sub-theme III: Health referral system

“… . I went to the HC, I was tested and diagnosed with MDR – starting on medication but with no improvement hence the health workers wrote a referral form and the center went and picked me from home …” (P-3)

“… . I went to the HC after taking my sample for testing they sent people with ambulance to pick me from home to the center …” (P-4)

3.5.1.4. Sub-theme IV: Side effects.

Anti-TB drugs are known for their adverse side effects. Participants shared their experiences about their suffering and narrated how hard it was for them to overcome them. Side effects especially dizziness, nausea, vomiting, breathlessness, anxiety, and insomnia were commonly observed; whereas breathlessness, anxiety, and nausea were major side-effects observed is observed more in patients with DR-TB

“… . Yes, I did. I was always dizzy, but because the sister had told me when I was getting the medicine the first time that it can happen. I knew that it was the side effect, so I complained to the doctor, who prescribed something for it and then it got better …” (P-15)

“… . Still after taking my medication, I feel breathlessness, nausea, and feverish. This is too difficult for me to bear; I feel very anxious … .” (P-12)

“… . When I started treatment, I used to take my tablets. And I used to feel the heat inside and nausea, urine used to be red, but then also I completed all the dosages … .” (P-1)

Many patients reported that they have become very weak due to the disease and are unable to practice their livelihood and support their families. The majority of patients are daily wage laborers and used to work in the field requiring lots of physical strength and energy.

“… . There was a time when I used to work hard in the garden from morning till evening, and also used to go to the jungle to collect firewood for cooking. But this disease has made me so helpless, now I can’t think of doing my daily routine works … .” (P-7)

3.5.1.5. Sub-theme V: Personal motivation

Patients cited internal motivation as a supporter of continuing treatment. Patients’ efforts to adhere to their treatment regimens must take drug side effects into account. The best outcomes for MDR-TB treatment can be facilitated by patient-centered care, which is a crucial modality to achieve impactful results of treatment.

“… . No, I didn’t think about giving up. It was bad, it sucked. That malaise, that bad thing in your head, you know, a lot of itching when I took the medication, but then I said no, I need to be strong, I need to be strong … …” (P-5)

“… . For me, the most motivating factor is in my mind and my mind always tells me that this is your life. For you to get better you have to take the medicine. So, I don’t even need any extra incentive to be able to go and get the medicine. It is in my mind. It is my life. I wake up and I have to go take the medication … .” (P-3)

3.5.1.6. Sub-theme VI: Loss of employment

“… . Ah, during my first treatment, I lost my job, and I was losing a lot of weight. I work as a cleaner … As I was very weak, I was without work and I was unable to buy food for home. I was having help from my neighbors. I think that’s why the first treatment didn’t work … but now with help from my family am determined to finish the treatment … .” (P-14)

3.5.1.7. Sub-theme VII: Treatment observation

The patients reported that they either come to Lira Hospital or a health facility to take the medication or the medication is kept with the VHT at the village who will bring them to the patients at an agreed time;

“… . Come every day at the center to take it…, the health-workers to be at the facility at 8am every day so that I can take my medication in the presence of Health workers” (P-1)

“… . From health facility, adherence counseling …” (P-2)

“… . I know myself to take medication, no one reminds me because if I need to live, then …” (P-3)

“… . I don’t need to be reminded …” (P-8).

“… . No one, I wake up with that in mind so I just go to the facility. …” (P-9)

“… . VHT call my son to remind me to go for my medication every day …” (P-13)

“… I move my medication in the bag, I have a health worker who calls me every day at 7 pm, but also from VHT who come and remind me …” (P-4)

3.5.1.8. Sub-theme VIII: Understanding of MDR-TB

The majority of patients said they didn’t know enough about MDR-TB. They were unaware of the illness’s symptoms and possible severity. They just knew that long-term treatment was required for the disease.

“… I did not know about it before, (weeps …) I only knew that it needs long time treatment which can be for months or even years.” (P-4)

3.5.1.9. Sub-theme IX: Use of reminders

Each patient had put up a mechanism to alert them when it was time to take their prescription. The strategies included sending SMS reminders, setting reminders or alarms on their phones, and having VHTs visit the medical facility or store their medications in the medication box.

“… I put a reminder on my phone, so when it goes off, I know it is time to take my medication … .” (P-7)

3.5.1.10. Sub-theme X: Adherence

Most of the participants indicated having adhered to their treatment except for a few who did not because of unavoidable reason

“… Yes, I have missed my medication once, one day, I had gone for burial with the hope of coming back but we did not return, that’s why I missed. …” (P-9)

“… Yes, the VHT gave me the medication but I was in the bathroom by the time he came so he left and I eventually forgot to take it that day …” (P-6)

“… . If I go to the HC, the HW told me they are busy, till late so I go angry and walk off in the first months but now am okay …” (P-7)

3.6. Health facility services lived experiences among female patients undergoing treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

3.6.1. Theme 4: Health facility related experience

3.6.1.1. Sub-theme I: Relationship with health workers

The patients appreciated how they were treated at the TB center in Lira regional Referral hospital as compared to the treatment they get when they go to the lower health facilities that were why they preferred to get the treatment at the main hospital.

“… The facility here (referral hospital) is better than the TB center, my health center near my home, where everyone does not listen to us and provides everything we want, there we have to ask several times, then only they listen. There we cannot talk to doctors directly, only attendants with us can talk to a doctor. They keep patients at distance. In the health center, they (health staff) hate patients. But in the hospital, they never showed such kind of behavior to us…” (P-7)

3.6.1.2. Sub-theme II: Perceived quality of the health services

Users of health services must build ties with one another in order to adhere to treatment and subsequently achieve favourable outcomes. This is especially true for health services that are a reference for the treatment of MDR-TB.

“… Ah, here, I have no complaints, they treated me well there, all the times I had there, I didn’t have it like that … no complaints. I know … I know the case of people who stayed from hospital to hospital … …” (P-4)

“… . We are always very well treated, right, at the time of treatment, they are very careful with us, they treat us very well, right … … .” (P-5)

“… . The hospital gave me a lot of attention, all the support, they were very affectionate, both in the hospital and in the outpatient treatment, they were always attentive, careful, caring, you know, I don’t have to say, ready to solve my situation, always talking to the team … … .” (P-7)

3.6.1.3. Sub-theme III: Access to health facilities

Guidelines for the treatment of tuberculosis (the DOTs plan) recommended daily morning visits to health facilities. However, many tuberculosis (TB) patients are unable to visit health facilities every morning due to transportation issues, thus they are treated by VHTs in the village so they may see the process. As a remedy to this dilemma, providers of health care occasionally elect to offer anti-MDR-TB medications to VHTs under monitoring.

“… . Our village is far from this hospital and the health facility closer health facility has very bad health workers who do not attend to me. Every time I go there, I would sit and wait until 6 pm and I started defaulting because sometime I would cry. I pay 10,000 shillings per day for a motorcycle every morning to come here. I do not have the money to follow this for the whole six months or so months. For the few days I live with my aunt but am not here for very long so I might have to look for an alternative which I don’t know …” (P-15)

“… The problem of COVID-19 make moving to the facility very difficult, the boda-boda increased the price of transport from 10,000 to 30,000…” (P-14)

“… During COVID we could only depend on the VHTs for treatment because the movement was restricted …” (P-5, P-7, 8, 9)

Some patients noted that the health workers and medication were always available which eased the struggle that would have come with drug stock-outs.

“… The drugs were available, the health workers were always there for us, and they are actually not like other wards …” (P-15)

“… Providing counseling and convincing me to come to the facility …” (P-1)

“… Nurses and others are all good here, they see us immediately. …” (P-5)

3.6.1.4. Sub-theme IV: Health workers’ messages

The main messages talked about to the patients mainly were adherence, protecting the other family members, proper feedings, and avoiding alcohol use among others.

“… Adherence, take the medication for one month then test at 2 months, 6 months, 8 months … …” (P-3)

“… How to protect me and other people and also put a mask and not share cups and forks … …” (P-8)

“… Adherence, involving into many sexual relationships. Avoid alcohol/ smoking, interact freely / avoid stress … …” (P-1)

“… Adherence, avoid alcohol, eat recommended food, juice and greens … …” (P-7)

“… Side effects of the medication, protection, don’t share, wear a mask, following the medication … …” (P-9)

3.6.1.5. Sub-theme V: Experience of side effects

Less than half of the participants experienced side effects. A participant stated:

“… .The joint pain was unbearable for me, I was much better then and I could not continue to cope with the joint pain. So, I just decided to stop taking the treatment and did not come again for my clinic appointment …” (P-8)

In addition,

“… . Ah, at the beginning it was, you know, some red pills for tuberculosis, you know, I wanted to vomit the food, it looks like it wouldn’t go down or up, it wouldn’t come out … I couldn’t vomit afterwards … …” (P-4)

“… A lot of dizziness and severe pain in the chest, right … .” (P-2)

“… A little bit of myalgia. Arthralgia in the first treatment…” (P-6)

3.7. Summary of results

It was revealed that the lack of social support from their husbands was an issue for female MDRTB patients. Prior to developing MDR-TB, female patients with a history of tuberculosis had better familial support systems. The diagnosis was strongly related to shock, anxiety, and denial.

3.7.1. MDR-TB

The majority of patients reported that having access to appropriate patient information about potential side effects assisted them in completing MDR-TB treatment. The MDR-TB services at Lira Regional Referral were easily accessible, and the personnel were courteous, in comparison to the lower-quality health centres in the area.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that a variety of persons provided social and emotional support, most frequently family members and clinic staff. The ability of patients to manage stress, anxiety, or depression was bolstered by their family or peers. Patients with MDR-TB were consequently better able to manage their symptoms, particularly in the early stages of treatment. This conclusion is supported by Akeju, who emphasized that social support is essential for adherence and can only be acquired by informing family and friends about the diagnosis and treatment of MDR tuberculosis. In addition, Tadesse et al. (Citation2015) found that social support was crucial for patients’ recovery. The assistance patients received from their family appeared to have a substantial effect on their treatment adherence in this study. The study also indicated that MDR-TB drugs are notorious for having adverse side effects, especially dizziness, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, anxiety, and insomnia, which are notable side effects during the beginning of treatment. Patients reported that they were aware of the adverse effects and needed to continue medication. This was likely owing to the fact that the medical staff adequately disclosed probable side effects before to administering the therapy. Contrary to (Akeju et al., Citation2017) statement, some formerly non-adherent individuals attributed their previous non-adherence to the negative impacts they experienced. Moreover, according to (Xu et al., Citation2009), participants’ adherence to the medication was hindered by its adverse effects, with some skipping doses entirely to avoid them. According to the Global TB Report (2016), numerous clinic visits may be required during the course of therapy for medication refills and monitoring in a health institution setting, especially if DOTS organisational level is not well implemented or if adverse drug side effects occur.

Due to the stigmatisation of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, the majority of patients reported feeling hopeless. The primary cause of stigma was the fear that MDR-TB would spread to the rest of society. This is supported by the findings of (Gebremariam et al., Citation2010), who discovered that a patient’s adherence to therapy may also be influenced by the unfavourable judgments of the community and friends, in addition to the attitudes of medical professionals. In a similar vein, (Njozing et al., Citation2017) uncovered evidence indicating that patients’ noncompliance with therapy may be influenced by unfavourable perceptions of healthcare professionals and a lack of social support.

Moreover, stigma is a characteristic that badly harms a person’s reputation in the eyes of others (Aggleton & Parker, Citation2015). The definition of discrimination is when an individual is singled out and treated unjustly and unfairly because of their membership in or perceived membership in a particular group. (Chesney et al., Citation2006) observed that stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis have been identified as significant obstacles to tuberculosis control and the efficacy of community-based DOTS and TB treatment.

This study revealed that MDR-TB health services at regional referral hospitals were nicer and easier to obtain than those at inferior facilities, and that friendly medical professionals and supplies were always available. This is consistent with the findings of (Khan et al., Citation2015), who reported that patients’ faith in the medical system appeared to be connected with their belief in the efficacy of therapy. When the medical health system functions well, patients benefit. If the medical health system is not functioning well, patients may place their trust and care in the conventional health system. In addition, according to (Edginton et al., Citation2017), patients are more likely to adhere to therapy if the physician’s advised course of action aligns with their knowledge of the disease’s core cause. In addition to other patient-related challenges, healthcare-related factors, and community-related determinants, Zenebe et al. (Citation2016) explained that irregular pill-taking, medicine stock-outs, and drug side effects have a direct impact on treatment failure.

As taking medication was the only option, this study revealed that patients were willing to do whatever it took to get cured of MDR-TB and regain their health. This was likely due to the patients’ mistaken belief that the disease might be cured with the correct treatment. According to (Edginton et al., Citation2017), patients’ perceptions of the treatment’s efficacy may have an impact on their adherence to treatment. In a similar vein, (Sagbakken et al., Citation2008) argued that a patient’s decision to receive therapy is impacted by the disease’s physical and psychological symptoms as well as the individual’s social and cultural environment. The majority of respondents to this study indicated that their knowledge of MDR-TB was inadequate.

They were uninformed of the symptoms and severity of the sickness. They simply understood that long-term care was required for the disease. This is likely due to the demand that TB patients adhere to their treatment plan until the full six-month course has been finished, as well as the requirement to conduct sputum smear follow-up tests at 2, 5, and 6 months to determine the cure rate and demonstrate the efficacy of the treatment. (Horter et al., Citation2016), who discovered that perceptions of the body, oneself, the treatment, and the disease altered drug tolerance, supports this hypothesis. Optimism and superior knowledge also aided adherence. Autonomy and control enabled the most effective treatment possible. We are unaware of any previous accounts of the effect of patient autonomy and control on MDR-TB treatment adherence. According to the 2016 WHO Global TB Report, the treatment success rate is the proportion of patients who have completed a 6-month course of tuberculosis therapy and whose sputum test is negative (cured). This recommends that the focus of therapy should be on the patient, using a community-based directly observed treatment short-course (DOTS) with a number of enablers and enhancers, including extensive follow-up for DOTS patients.

According to this study, the majority of patients sought treatment when their tuberculosis symptoms became intolerable and they decided to seek a cure. The majority of patients reported to have tried over-the-counter drugs and herbal therapies, but these failed to alleviate their symptoms, pushing them to seek treatment in a hospital setting. This is a significant obstacle to early identification, which allows for early treatment. Testing and diagnosis include complex dynamics that vary between patients. This is akin to the findings of (Helman et al., Citation1998), who demonstrated that understanding of TB symptoms can influence testing and, consequently, early treatment. The social setting in which people are tested influences their decision to undergo testing, and macro-level variables influence responses to symptoms or signs. Family, friends, and others in social connections are instances of the in issue macro-level aspects. Similarly, (Mochache & Nyamongo, Citation2009) found that respondents attributed TB to a range of causes, such as AIDS, heredity, and risky behaviour (such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and unprotected sex). The weather (severe cold), supernatural elements, the air (poor ventilation, bad air), poor hygiene (dirty utensils, undercooked food), and starvation were also listed as contributing reasons. Self-medication with prescription pharmaceuticals, divine intervention, hospital visits for diagnostics and care, and access to local practitioners of traditional medicine were among the available therapeutic choices. This shows that the dynamics surrounding a patient’s MDR-TB diagnosis influence the patient’s overall experience with the disease. Moreover, understanding of MDR-TB symptoms influences the decision to seek testing or additional therapy. This is consistent with (Farmer & Kim, Citation2004) conclusion that access to health centres influences how people seek treatment and that structural violence is one of the barriers to access. This study revealed that having MDR-TB can affect a person’s physical, emotional, social, and economical health. Negative emotions, such as fear, hopelessness, melancholy, anxiety, and depression, accompanied the MDR-TB diseases of the patients. Consistent with this, Gyimah & Dako-Gyeke (Citation2019) found that barriers to caring for tuberculosis (TB) patients included prevailing cultural perspectives, physical and psychological stress, repercussions of patients’ interrupted labour, and health system challenges. People adopted mental, physical, and spiritual coping mechanisms to overcome adversities.

According to this study, the majority of patients hid their MDR-TB diagnosis from the community out of fear of discrimination and stigma, only disclosing it to a limited group of close relatives and friends.

This is supported by Carey (Citation2013) ‘s 2013 finding that 75% of community members fear and avoid tuberculosis patients. In their study, Zaher et al. (Citation2014) discovered that 44% of the individuals reported concealing their TB diagnosis from others because they were unprepared to confront stigma.

According to the findings of the study, the MDR-TB centre at Lira Regional Referral Hospital provided superior care compared to other medical institutions. According to (Jaiswal et al., Citation2003), problems with poor communication and a lack of care and support from the patient’s family and healthcare professional can occasionally lead to default. According to Munro (Toczek et al., Citation2018), successfully completing TB therapy requires a solid working connection between the patient and the healthcare staff, as well as cultural harmony, patient attitude, family support, and health literacy.

The patient’s overall satisfaction and trust in the provider, the patient’s assessment of the provider’s ability to deliver the necessary care, the provider’s readiness and willingness to involve the patient in the decision-making process, the nonemotional tone of the relationship, such as affection, honesty, sincerity, and support, and the appropriate referral or linking of patients with suitable community volunteers are all components of the relationship between the patient and the provider (Johnson et al., Citation2006). This suggests that healthcare practitioners should encourage patients to tell their family and friends about their MDR-TB diagnosis and therapy so that they can receive assistance and support while they are undergoing treatment. Specifically, this suggests that patients should tell their family and friends about their treatment for MDR-TB.

According to the results of the poll, some of the patients felt that the medical personnel had provided them with sufficient information regarding their therapy and what they may expect while they were experiencing it. Patients cited apprehension regarding the outcomes of their therapies as a barrier to complete those treatments; nevertheless, they did not cite information as a facilitator in their recovery process. This is in line with the findings of (Molapo, Citation2010), which demonstrate that increasing a patient’s knowledge of a certain illness, such tuberculosis, leads to a greater comprehension of that illness by the patient. Patients who are non-adherent to their tuberculosis therapy are often individuals who have a limited understanding of the disease and its treatment. In a study that was quite similar to this one, (Kaona et al., Citation2014) found that the level of disease knowledge that a patient had seemed to have a significant impact on both the patient’s health behaviours and their adherence to treatment (Katende & Omona, Citation2021). This indicates that there is a need for improved health education and communication in communities, as well as in hospitals and clinics.

5. Conclusion

The social lived experience that was gathered for this study demonstrates that having social support is still very important for successfully completing therapy. The diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) can put patients in a state of shock, anxiety, and denial, which, when combined with stigma and prejudice, can make coping difficult and lead to poor treatment outcomes. Positive reinforcements for improved coping mechanisms in MDR-TB treatment include receiving social support from the patient’s family and hospital, as well as from other individuals who are aware of the MDR-TB diagnosis.

The findings of the study showed that the transition process was accompanied by emotional storms at the time of diagnosis. This was the case despite the fact that the majority of patients were aware of the seriousness of the disease and had a proper understanding of MDR-TB, as well as known reasons for seeking treatment.

The process of maintaining adherence involves a number of aspects, including reminders, the assistance of VHTs’ families, and the availability of indirect financial associated costs. In addition, the patients noted that discrimination is a barrier to treatment adherence and positive outcomes, which is something that needs to be addressed. The level of friendliness and accessibility of services provided by the Lira Regional Referral Hospital to patients was significantly higher than that of the lesser quality health facilities.

6. Recommendations

From this study, we recommend as follows;

The management of healthcare facilities should address the challenges that patients and their support networks face. They should place an emphasis on the need for “patient-centered care,” which means that patients’ needs should be comprehended and prioritised at lower facilities that are located closer to the patients in order to reduce indirect costs related to the care they receive.

The significance of psychological stressors and the absence of social support should also be brought to the attention of healthcare providers as gateway determinant for successful treatment results.

We suggest that patients and their family members receive appropriate health information regarding the illnesses and care plan in order to establish an effective support system. This will enable patients to make more informed decisions regarding their care.

The Ministry of Health must work to expand patient access to counselling and mental healthcare services for those who are undergoing treatment for MDR-TB. In addition, the screening for and treatment of mental health disorders have to be incorporated in the national recommendations for the management of MDR-TB cases in order to deliver a higher level of medical care.

The Ministry of Health needs to develop and implement a comprehensive mechanism for contact tracing of new tuberculosis cases and defaulters, as well as the implementation of a comprehensive surveillance system and the conducting of operational research on the success rate of tuberculosis treatment among DOTS patients.

Contributorship

OG conceptualized the study, designed the methodology and did the preliminary analysis and approved the final version for publication. OK supervised the work, curated the analysis and design for all intellectual contents, approved the final version for publication and agreed to be pivotal in any correspondence to do with any intellectual content of the study. He is the corresponding author, for this matter.

Data sharing

Data related to the study is available with the corresponding author and on reasonable request, it can be availed.

APPENDIX_Indepth Interview Guide.docx

Download MS Word (18.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the support rendered to us by Mr Acaye James. We also appreciate the management of Lira Regional Referral Hospital and extend our sincere appreciation and thanks to our valued respondents, without whom this study wouldn’t be completed. They provided primary information about their lived experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/27707571.2023.2292892

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kizito Omona

Kizito Omona, is a Medical Doctor, researcher and lecturer attached to Faculty of Health Sciences of Uganda Martyrs University. He holds a PhD in Management (Healthcare Mgt), Master of Science in Health Services Management (MSc. HSM) and Master of Science in Monitoring and Evaluation (MSc. M & E) and Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB) from Gulu University, amidst other qualifications.

Christopher Ogwang

Christopher Ogwang, is a graduate Nurse with over 10 years of experience in health training and research. He worked with different reputable organizations and in service delivery, health training and mentorship interventions, advocacy, capacity building, Community Empowerment, Project management and research. He holds Bachelor of Science Nursing (BScN), Post graduate Diploma in Monitoring and Evaluation and Master of Public Health.

References

- Aggleton, P., & Parker, R. (2015, August). Moving beyond biomedicalization in the HIV response: Implications for community involvement and community leadership among men who have sex with men and transgender people. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 1552–27. Epub 2015 Jun 11. PMID: 26066963; PMCID: PMC4504295. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302614

- Ahmad, M., Sahile, Z., Yared, A., & Kaba, M. (2019). Patients’ experiences and perceptions on associates of TB treatment adherence: A qualitative study on DOTS service in public health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 462.

- Akeju, O., Wright, S., & Maja, T. (2017). Lived experience of patients on tuberculosis treatment in Tshwane, Gauteng province. Health SA Gesondheid, 22, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2017.03.001

- Batte, C., Namusobya, M. S., Kirabo, R., Mukisa, J., Adakun, S., & Katamba, A. (2021). Prevalence and factors associated with non-adherence to multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treatment at Mulago national Referral hospital, Kampala, Uganda. African Health Sciences, 21(1), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v21i1.31

- Calver, H., & Molapo, J. T. (2010). Tuberculosis specific behavior changes communication material for a low-literacy population in Mamelodi [ Ph.D. thesis]. Tshwane University of Technology.

- Carey, C. (2013). Tuberculosis of soft palate. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 22(12), 1557–1557. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591572902201225

- Chesney, M. A., Neilands, T. B., Chambers, D. B., Taylor, J. M., & Folkman, S. (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(Pt 3), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X53155

- Edginton, M. E., Sekatane, C. S., & Goldstein, S. J. (2017). Patient’s beliefs: Do they affect TB control? A study in a rural district in South Africa’. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 6(12), 1075e1082.

- Farmer, P., & Kim, J. Y. (2004). Community based approaches to the control of multidrug resistant tuberculosis: Introducing “DOTS-plus”. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 317(7159), 671–674. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7159.671

- Gebremariam, M. K., Bjune, G. A., & Frich, J. C. (2010). Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 651. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-651

- Gyimah, F. T., & Dako-Gyeke, P. (2019). Perspectives on TB patients’ care and support: A qualitative study conducted in Accra Metropolis, Ghana. Globalization and Health, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0459-9

- Helman, R. G., Russell, W. C., Jenny, A., Miller, J., & Payeur, J. (1998). Diagnosis of tuberculosis in two snow leopards using polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation: Official Publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc, 10(1), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/104063879801000118

- Horter, S., Stringer, B., Greig, J., Amangeldiev, A., Tillashaikhov, M. N., Parpieva, N., Tigay, Z., & du Cros, P. (2016). Where there is hope: A qualitative study examining patients’ adherence to multi-drug resistant tuberculosis treatment in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. BMC Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1723-8

- Jaiswal, A., Singh, V., Ogden, J. A., Poter, J. D. H., Sharma, P. P., Sarin, R., Arora, V. K., & Jain, R. C. (2003). Adherence to tuberculosis treatment: Lessons from the urban setting of Delhi, India. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 8(7), 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01061.x

- Johnson, R., Streicher, E. M., Louw, G. E., Warren, R. M., van Helden, P. D., & Victor, T. C. (2006). Drug resistance in mycobacterium tuberculosis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 8(2), 97–111.

- Kaona, F. A. D., Tuba, M., Siziya, S., & Sikaona, L. (2014). Assessment of the factors contributing to treatment adherence and knowledge of TB transmission among patients on TB treatment. BMC Public Health, 4(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-4-68

- Katende, J. N., & Omona, K. (2021). User - provider perspectives to overcome the challenges of TB/HIV service integration at Mulago national Referral hospital _ Kampala. African Health Sciences, 21(1), 248–53. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v21i1.32

- Khan, M. A., Walley, J. D., Witter, S. N., Shah, S. K., & Javeed, S. (2015). Tuberculosis patient adherence to direct observation: results of a social study in Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning, 20(6), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czi047

- Lönnroth, J., Gelaw, M., Dejene, A., Lemma, E., & Eyob, G. (2016). Attitude, and social consequences of tuberculosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East African Medical Journal, 78(7), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.4314/eamj.v78i7.9014

- Mishra, V., Khatri, R. B., & Khanal, S. R. (2017). Female community health volunteers in community-based health programs of Nepal: Future perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(July), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00181

- Mochache, L. N., & Nyamongo, I. K. (2009). Factors influencing tuberculosis management in rural south-west Kenya. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: The Official Journal of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 13(7), 895–899.

- Molapo, J. T. (2010). Tuberculosis specific behavior changes communication material for a low-literacy population in Mamelodi [ Ph.D. thesis]. Tshwane University of Technology.

- Munro, S. A., Lewin, S. A., Smith, H. J., Engel, M. E., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2017). Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Medicine, 4(7), e238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238

- Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L.(2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

- Njozing, B. N., Edin, K. E., Sebastian, M. S., & Hurtig, A. (2017). Voices from the frontline: Counsellors perspectives on TB/HIV collaborative activities in the Northwest Region, Cameroon. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-328

- Omona, K., & Opiyo, M. A.(2023). Assessment of risk factors associated with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Gulu regional referral hospital. African Health Sciences, 23(3), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v23i3.41

- Sagbakken, M., Frich, J. C., & Bjune, G. (2008). Barriers and enablers in the management of tuberculosis treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-11

- Shanmugam, H., & Dobler, C. C. (2016). Success of community-based directly observed anti-tuberculosis treatment in Mongolia. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 19(6), 657–662. Online. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.14.0927

- Tadesse, M., Akessa, G. M., & Abebe, G. (2015). Survival analysis of loss to follow-up treatment among tuberculosis patients at Jimma University specialized hospital. Hindawi. ID 923025.

- Toczek, U., Philadelphia, P. A., Williams, L., Wilkins Speziale, H. J. S., & Carpenter, D. R. (2018). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic perspective. Philadelphia: Lippincott Prevalence and Associated Factors African Health Sciences, 9(S1), 8e15.

- Walker, T. M., Kohl, T. A., Omar, S. V., Hedge, J., Del Ojo, E. C., Bradley, P., Iqbal, Z., Feuerriegel, S., Niehaus, K. E., Wilson, D. J., Clifton, D. A., Kapatai, G., Ip, C., Bowden, R., Drobniewski, F. A., Allix-Béguec, C., Gaudin, C., Parkhill, J. … Modernizing Medical Microbiology (MMM) Informatics Group. (2015). Whole-genome sequencing for prediction of mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility and resistance: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 15(10), 1193–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00062-6

- WHO. (2016a). Global tuberculosis report 2016. World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2016b). Global tuberculosis report, 2016. WHO/HTM/TB/2017.23. World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organisation. (2015). Global tuberculosis report. http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_en.pdf

- World Health Organisation. (2019). Global tuberculosis report 2019. World health organization. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- Xu, W., Lu, W., Zhou, Y., Zhu, L., Shen, H., & Wang, J. (2009). Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment among pulmonary tuberculosis patients: A qualitative and quantitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 9(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-169

- Zaher, H. H., Morsy, A. M., Hassan, M. H., & Shouman, A. (2014). Predictors of treatment failure among tuberculosis patients under DOTS strategy in Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue de Sante de la Mediterranee Orientale = Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit, 9(4), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.26719/2003.9.4.618

- Zenebe, Y., Adem, Y., Mekonnen, D., Derbie, A., Bereded, F., Bantie, M., Tulu, B., Hailu, D., & Biadglegne, F. (2016). Profile of tuberculosis and its response to anti-TB drugs among tuberculosis patients treated under the TB control programme at Felege-Hiwot Referral hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 688. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3362-9

Appendix

Demographic information

A)

Social related factors

1) What do you know about MDR-TB?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … … … …

2) How did you know that you have MDR-TB? (Probes: Did you experience certain symptoms and did you recognize them as MDR-TB symptoms? Did you go for normal treatment and the doctor recommended a test? Also, Probe for the causes, symptoms, consequences)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

3) What were the perceptions of your family about MDR-TB? What was the perception of the community where you live? (Probe for; support from spouse and close relatives morally, spiritually, and financially)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

4) What do people in your community say about it now? Why?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

5) Who knows that you are taking treatment? Who have you told or declined to tell? Why or why not? How did they react?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

6) How do you remember to take the drugs? (Probe for; There is someone who watches or reminds you. Do you have a schedule/reminder? If there is someone who observes you as you take the drugs, who is he/she where does he/she live? Is there a day you can remember that you did not take the drugs? What happened so that you forgot?)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

7) Have you defaulted treatment (missed taking TB drugs? Why or why not? If yes, for how long? Do you know someone who has ever defaulted? Why?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

B)

Transitions conditions experiences

1) Let us talk about testing/diagnosis.… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

2) What was your feeling about testing? (Probe for; What prompted you to go for testing? Did you tell anyone- the family, friends, neighbors that you are going for TB testing? What was the reaction of your family and what did they say? How did they support you? How were you feeling about their response/reaction and the entire testing procedure?)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

3) Who were you living or interacting with before diagnosis? Did they continue living or interacting with you after that diagnosis? Why or why not?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

4) Please, can you tell me from your perspective, what has been your lived experience since you started MDR-TB treatment? (Probe for; History leading to an MDR-TB diagnosis, Influence of personal social situation, Influence of good social support and disclosure)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

5) Let us talk about the problems you face in treatment? (Probe for; Do you forfeit other duties because of going for medication? What side effects do you experience if any, because of taking the MDR-TB drugs? Cost, schedule? How do you feel about them? How do you deal with them? Who helps you to deal with them?)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

6) Are you free to take drugs in public? Why or why not?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

C)

Treatment adherence experience

1) What was your experience taking MDR-TB drugs? (Probe for; experience in taking daily medication, experience of the previous non-adherence, experiencing self-efficacy to complete treatment regimen, Knowledge related to tuberculosis and treatment)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

2) Tell me your experiences about the role of the family in terms of adherence to treatment and controlling stress… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

3) Did you get the treatment after testing or did you wait? If you wait, why and for how long? (Probe for; What did the doctor tell you about the treatment? Defaulting, duration of intake? Other instructions? How did you feel about that information?)… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

4) Tell me about sharing information about treatment.… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

5) Who do you stay with now while taking the TB drugs? Why?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

6) What are some of the factors that affected your adherence to these drugs?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

D)

Health Facility related experiences

1) Tell me about your experiences of using the MDR-TB unit services in terms of managing your illness.… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

2) Tell me your experiences about the role of healthcare providers (doctor, nurse, health centers) about MDR-TB treatment and controlling stress… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

3) Tell me your experiences about social barriers for taking MDR-TB treatment.… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …

4) What problems have you experienced in the course of MDR-TB treatment in the facility?… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … …… … … … … … … … … … …