Abstract

Physical contact such as tackling is a part of youth sport, but associated with concussion risk. Coach communication with athletes about how to approach contact could be a strategy to reduce concussion risk. We interviewed n = 50 adult stakeholders (coaches, referees and administrators) in youth football and soccer to identify barriers and facilitators to coach communication about contact. We framed interviews using the Theory of Planned Behavior, discussing: knowledge/experience, attitudes/beliefs, norms/values and perceived behavioral control. Stakeholders could easily describe ‘good’ contact (knowledge/experience) like keeping your head up (football) and tackling shoulder-to-shoulder (soccer), and ‘bad’ contact like spearing (football) and retaliating against an opponent (soccer). They also talked about the importance of sportsmanship and playing by the rules. Most coaches believed ‘bad’ contact was associated with greater injury (attitudes/beliefs). Coaches felt responsible for managing contact (norms/values), but also described not receiving any information indicating that this was part of their role. Coaches worried about creating a fear of injury, and felt it was important for discussions to be framed positively (perceived behavioral control). In summary, youth football and soccer coaches believe ‘bad’ contact is associated with greater injury risk and feel it is their role to provide youth guidance about contact, but describe a lack of institutional guidance regarding this role. They also are concerned about barriers, including creating fear, and describe ways to address this barrier with language. Developing programs to support coach communication about contact with youth athletes presents a potential strategy for concussion prevention.

KEY MESSAGES

Youth football and soccer coaches know that some contact (like head-to-head tackling) is associated with greater risk of injury, particularly concussion.

Coaches feel responsible for teaching youth approaches to tackling and other sport contact that have a lower risk for injury, but most are not provided guidelines for how to do this.

Coaches feel it is important to frame messaging positively, e.g. ‘lead with your shoulders’ rather than ‘keep your head down’.

Instructing coaches regarding how to teach ‘good’ contact in sport is a potential strategy for injury prevention.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

More than 44 million U.S. youth 6 to 17 years old participate in organized sports (Langhorst, Citation2016). While sports provide opportunities for social connection, physical activity and skill development (Eime et al., Citation2013), participation in sports is also associated with risk of injury, particularly concussion (Howell et al., Citation2020). Sports that involve routine contact and collision pose the greatest risk for concussion, with soccer being one of the most popular contact sports worldwide and football (i.e. American football) yielding some of the highest rates of injury (Marshall et al., Citation2015). Sustaining a concussion in sport can in turn have significant impacts on all aspects of youth development, impacting academics, social interaction and emotional state (Voormolen et al., Citation2019). It is thus vital that we work to mitigate concussion risk in youth sport.

Previous work to decrease concussion risk in sport has focused on increasing identification of concussion in youth through both legislation (Yang et al., Citation2021) and educational interventions designed to increase reporting (Kroshus et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; Register-Mihalik et al., Citation2013). However, these approaches at best result in secondary prevention–-mitigating the potential risk of an injury after it has occurred, or decreasing concussion morbidity. From a public health standpoint, we believe in the importance of primary prevention of concussion, or decreasing concussion incidence (Emery & Pasanen, Citation2019). Prior work regarding on-field measurement of biomechanics suggests that for a concussion to occur, an athlete must sustain a collision of sufficient magnitude with either another player, the ground or an object (Guskiewicz & Mihalik, Citation2011). There are thus two pathways towards decreasing concussion incidence in sports: (1) decreasing collisions and (2) mitigating the force of those collisions. The majority of sports-related concussions occur due to collisions between players (Maher et al., Citation2014; Willigenburg et al., Citation2016), and certain types of collisions have been found to be associated with greater risk for concussive injury, such as head to head contact in football (i.e. spearing) and body checking in ice hockey. Rules limiting those types of activities in youth sports have resulted in fewer injuries (Black et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Emery et al., Citation2010; Obana et al., Citation2021; Warsh et al., Citation2009). USA Football (an organization that oversees U.S. football leagues) developed an injury prevention program based on limiting inappropriate or potentially injurious contact in youth called Heads Up Football®, with evidence suggesting benefit for this approach (Kerr et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Shanley et al., Citation2021; Tokish et al., Citation2017). Heads Up Football® teaches youth to tackle in football by leading with the shoulder rather than the head, and also incorporates monitoring and feedback with a goal of decreasing injury. However, Heads Up Football® is not widely available and is associated with a cost, and thus many football leagues or schools do not currently utilize this approach.

Recognizing the need for accessible approaches to primary prevention of concussion in youth sports, we decided to explore how coaches think about and discuss physical contact and injury risk with youth athletes. Providing guidance to youth athletes about the relationship between types of contact and injury risk has the potential to reduce dangerous collisions, thereby decreasing injuries in youth sports. Coaches are in an ideal position to communicate this type of information to youth athletes, as a trusted adult supporting safe youth participation in the sport. However, little is known about whether and how coaches engage in these types of dialogues, and factors that influence these discussions. We undertook this study to fill this gap in the extant literature, interviewing coaches and other key stakeholders in youth football and soccer to understand the coach role in managing youth athlete contact, and barriers and facilitators to having discussions about contact with youth athletes. We then analyzed these interviews to develop a conceptual model regarding factors influencing coach discussions about contact, adapting the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991).

Materials and methods

Study design and research personnel

The sample for this study is a subset of that used for a previous study (Chrisman et al., Citation2022). In order to obtain a more diverse sample that would increase generalizability, we undertook these discussions with participants from two geographic regions: 1) Western Washington and 2) Southern Georgia. In brief, we completed qualitative interviews from 2019–20 with coaches, referees and field administrators from youth football and soccer leagues (Kroshus & Chrisman, Citation2019). We conducted rigorous data collection and analysis and this report conforms to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brien et al., Citation2014). The research team included a pediatrician and health services researcher (SC), a public health researcher (EK), a medical anthropologist (KS), a health communications researcher (BB), a professor of athletic training (TH), a research coordinator (RH) and five clinical research associates with backgrounds in exercise science, sport psychology and athletic training (EK, NW, SW, KH, MM). Data were collected and analyzed by RH, TH and the research associates who were trained in qualitative interviewing, codebook development, coding and synthesis by KS who supervised the activities. Interviewers and interviewees were culturally and ethnically congruent as much as possible. Team members had experience with sport culture as athletes, coaches or athletic trainers, and conducted interviews in their own region given the cultural differences between Southern Georgia and Western Washington.

Data tools

We designed an interview guide as a team and adjusted as necessary per standard qualitative methodology (Patton, Citation2015). Interviewees first answered a few demographic questions, and then more extensive qualitative questions (see Appendix for full interview guide). Topic areas for the qualitative interviews were developed using the frame of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991), a theory of behavior which highlights factors thought to influence the likelihood of a certain behavior (in this case, stakeholder communication about contact and injury risk in sport), particularly: Knowledge/experience, Attitudes/beliefs, Norms/values and Perceived Behavioral Control. We utilized open-ended questions to discuss physical contact and injury risk in sport, focusing on these key constructs from TPB.

Sampling frame and data collection

We recruited a purposive sample of youth soccer and football coaches, referees and administrative staff from Southern Georgia and Western Washington (n = 27 from Western Washington and n = 23 from Southern Georgia). Recruitment occurred via phone call, email and/or text, and interviews took place over the phone or in person (at a convenient location such as a coffee shop or community center). Interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, and spot checked to ensure data integrity. Every effort was made to maintain participants’ confidentiality during data collection and manuscript preparation. All audio files were destroyed immediately following transcription. Participants provided written consent and were provided an incentive for their time (US$40). The Seattle Children’s Research Institute Institutional Review Board and Georgia Southern University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using Dedoose version 7.0.23 (Dedoose, Citation2018) for coding and thematic content analysis (Bazeley, Citation2013) following procedures outlined by Braun and Clark (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We developed a hierarchical codebook based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) and data review. Initial codes were derived from study goals and the interview guide, but codes were adapted and augmented based on review of five transcripts. New codes were tested on two additional transcripts by all coders and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The codebook continued to be edited in this fashion until an exhaustive but manageable code list was reached. Transcripts were then open-coded using the final version of the codebook, by at least two coders, preferably including the individual who conducted the interview. Coders utilized a process of memoing to document decision points and assure transparency in interpretation and analysis. Coders were blind to each other’s coding and all differences were resolved by discussion until 100% agreement was reached. When necessary, the codebook was modified to accommodate new codes or definitions. Each code report was synthesized by one analyst using a system of annotating and summarizing into theme domains and subdomains with associated quotes. All steps of the analysis were overseen and guided by KS. Demographic data were compiled and tabled using Stata version 14 (Statacorp, Citation2015).

Table 2. Qualitative themes and representative quotes from an interview study about physical contact in sport with youth coaches, referees and administrators, 2019–2020.

Results

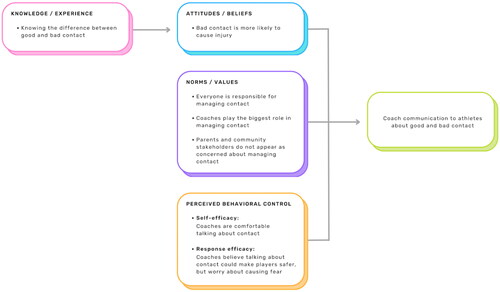

Demographic data for the sample are presented in . We organized our coding framework by adapting the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) to identify factors influencing coach communication about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ contact during sport (). Of note, we chose the terms ‘good’ and ‘bad’ as we used these in the interviews about contact and they were understood by all stakeholders. Using the framing of TPB, we theorized that:

Figure 1. Conceptual model of factors impacting coach communication about good and bad contact with youth athletes, framed using the Theory of Planned Behavior.

Table 1. Demographics of coaches, referees and administrators participating in qualitative interview study regarding coach communication about physical contact in youth sports 2019–2020.

Knowledge/experience about contact influences Attitudes/beliefs about contact

Attitudes/beliefs about contact, Norms/values about contact and Perceived behavioral control about contact all influence whether and how coaches communicate about good and bad contact with youth athletes.

We report our findings by domain/subdomain/quote (), stratified by sport (football and soccer). For some domains, there were more similarities across the whole sample than differences between sports, and we noted where that occurred. Additionally, where there was a difference by geography, we highlighted the difference; generally there were more similarities than differences between states. Where differences seemed significant, we denoted that in the table with initials representing geography (G or W for Georgia or Washington) and sport (F or S for football or soccer). Our focus was on coaches as the primary conduit to players, but we included findings related to referees where relevant as they were components in the larger context of game-time contact.

Themes

Knowledge/experience

Knowing the difference between good and bad contact

Coaches easily described both good and bad contact for their individual sports, but particularly for football. Good contact in football was both the actions (proper tackling and blocking including keeping the head out of the play) and also the underlying ethic of playing in a ‘safe sportsmanlike way’. (GF1) Football coaches had an image of ‘perfect’ tackling: ‘Leading with your shoulder and not your head and having a target zone between the hip and the shoulder…a good square contact, wrap and drive’. (WF1) Soccer coaches talked about the importance of ‘trying to win the ball not…hurt the player’ (WS1) and ‘playing by the rules’, while acknowledging, ‘it’s a physical game…you have to be willing to be physical’. (WS2) Football stakeholders described bad contact as blindsiding, helmet-to-helmet plays and hitting after the play, noting: ‘There’s more involved with penalties than just you’re trying to get an advantage over the other team. It’s also the safety of the player’. (WF2) In soccer they discussed kicking, tripping, and using arms rather than shoulders. In both sports, interviewees pinpointed fighting as bad contact and talked about how intention divided good contact from bad. Intent to injure or hurt the opponent resulted in ‘bad’ contact, which could be driven by anger or recklessness: ‘There’s that line where some kids are out there, and they got mad or really want to hurt somebody, so that could be part of the bad contact’. (GF2)

Attitudes/beliefs

Bad contact is more likely to cause injury

Across the sample, interviewees talked about bad contact causing injuries to both initiating and receiving players. In football these events included ‘bad’ tackling and blocking, ‘…especially using the crown of their helmet’. (WF3) In soccer, players had been injured when they slide tackled, played recklessly and used headers without proper form. Interviewees talked about ‘cheap shots’ performed to cause injuries; in football this included hitting defenseless players and hitting after the whistle, and in soccer aggressive fouls and retaliatory moves. Soccer respondents talked about the importance of referees setting expectations and managing games to control contact and minimize risk of injuries. This was noted as especially important when aggression was escalating: ‘when anger comes into play, then I think that increases that testosterone and the power behind the physical contact, and that’s when I personally see injury occur’. (GS1)

Bad contact is often not intentional

Bad contact happened even with the best of intentions and was often attributable to the same issues across football and soccer: lack of body control/technique/coordination and poor execution within the rules such as playing after the whistle, playing the player rather than ball and poor timing during tackles. Stakeholders from both sports cited size differential as a possible cause of bad contact, especially for young players, and declared that players needed to learn to anticipate contact so they could physically prepare for the interaction: ‘The thing is how to keep your head, how to swivel’. (WF2). Football coaches described football as ‘a violent contact sport’ and soccer coaches said players ‘use aggression’ so there would always be a risk, but danger could be tempered by training, technique and good intentions. In both sports, stakeholders felt younger players lacked coordination, spatial awareness and self-control, all of which could contribute to bad contact and result in injuries even with no intent to harm: ‘Someone’s trying to win the ball and they just misjudge an angle, or they go down earlier than they expect, or whatever, and it’s going to result in a dangerous play, but wasn’t intended’. (WS3)

Norms/values

Everyone is responsible for managing player contact

Management of contact was seen as a shared responsibility between coaches, opposing coaches, administrators, referees, parents and players: ‘Obviously, we’re gonna talk in practice about it, but if something’s going on in the game, there’s a limit to what we can do–that one is on the officials. And it’s also on the other coach’. (WF4) Respondents saw themselves and other coaches as responsible for teaching good technique and following up with corrections for bad contact which could include removal of players who were too emotional to manage themselves. They talked about the challenge of focusing on good contact (in keeping with larger sports philosophies of focusing on the positive) balanced against correcting bad contact. When probed to reflect on their experience with opposing coaches, they described a spectrum of concern from some who were focused on safety and good conduct to others who encouraged illegal play and fouling: ‘Absolutely, that coach had a dirty team and he had a dirty team because he taught them to be dirty’. (GS2) Referees were seen as having a unique and critical role for managing contact in games through pre-game reminders and controlling game physicality via calling penalties/fouls, stopping play quickly and limiting reckless contact: ‘The ref controls the flow of the game, so if you let them continue to play dirty, the whole game will be like that’. (GS3) Soccer respondents explained how referees, in turn, rely on team captains to manage their teammates. Parents, too, were mentioned as part of this collaborative cluster, but the few comments about parents indicated they sometimes contradicted the coach by either overprotecting players (football) or encouraging inappropriate play (soccer): ‘They tell their kids, ‘That was a good play’. And I tell the kid, ‘No, it wasn’t a good play. I’m calling the whistle. That’s a foul. Don’t do it again’.’ (GS4) Players, on the other hand, were seen as critical to intentionally controlling their own bodies, practicing what coaches teach regarding contact, and focusing on their own actions in games rather than on the opposition.

Coaches play the biggest role in managing player contact

Coaches identified themselves as ultimately responsible for managing contact across both football and soccer. While many agreed that talking with players about contact was important, coaches identified practices, post-game debriefs and brief game-time reminders as preferable to pre-game talks that might conflict with pre-game hype sessions: ‘We show him on film what he did, how it’s not okay, how it impacts his teammates, how that’s gonna hurt the other player and himself’. (WF5) At game time, football coaches talked about encouraging good tackling technique and playing in a sportsmanlike manner, while soccer coaches talked about playing to the referee, aggressive play within the rules, and respecting the game and opponent. Coaches felt responsible for modeling good behavior and teaching life skills. Soccer coaches focused more on how to support good contact, while football coaches talked more about managing bad contact. Coaches had the power to address bad contact when it happened and they used this power via talking with players, evaluating intent and at times removing them from play.

The larger community does not appear concerned about bad contact

Respondents spoke mostly about parents when reporting on community concerns. They described a complex set of opinions expressed by the community that varied by sport. The football community was seen as supportive of football teams and engaged by the physicality of the sport: ‘This community embraces football…it’s just like ‘Hey, we’ve got a great football program’.’ (WF2) However, football enrollment had been declining in some locations due to injury risk, and coaches were openly concerned about the difficulty fielding teams: ‘We can’t even practice against our own team over here, we have that few kids’. (WF4) For soccer, discussions about contact seemed directly connected to games and specific plays. Interviewees from both sports commented on a general community perception that football has more bad contact and corresponding injuries than soccer, with one participant commenting that soccer is seen as being for ‘wimpy kids who can’t take tackles’. (WS4)

Perceived efficacy and behavioral control

Coaches are comfortable talking with players about contact and believe talking about contact could make athletes safer, but they also worry about causing fear

Coaches in both sports reported feeling confident and comfortable talking about contact with their players, but also noted there were time limits (especially right before games) and players at this age can be inhibited by lack of attention. Some coaches were concerned about finding the best way to talk with their players about the reality of sport injuries and game penalties without causing them to ‘play scared’, which could also result in injury: ‘I don’t think anyone can perform at their highest level when they’re worried about some external factor’. (GS1) The default approach seemed to be to encourage positive aggressive and physical play, and only a few talked with players about consequences of bad contact (both pre-game and in the moment): ‘I’m all about the positive things, the positive side of things…I’m a firm believer if you tell someone not to do it, what are they going to do? They’re probably going to do it’. (WF2) Practices were seen as the preferred opportunity to talk about contact as this provided more time and space for discussion: ‘I don’t think it can be a last minute reminder. I think you can encourage them to play clean, play safe and play aggressive, but that baseline, that foundation is set in training’. (GS5) Respondents reported that talking about contact is an important part of being a good coach and had the potential to make athletes safer: ‘Some kids come in with the mentality that this kid’s better than me and I’m gonna have to hurt him. If you talk about it and say ‘Hey, this is not okay, don’t do this’, I think it would change that kid’. (GF3) However, not all coaches could see a direct correlation between talking about contact and safe, injury-free play: ‘Some players are gonna play whatever way they wanna play no matter what you tell them’. (GS4) Youth football and soccer athletes play very physical games, and coaches felt the need to strike a balance between instruction about good/bad contact with encouraging, positive, enthusiastic coaching to produce confident, aggressive players: ‘I’m trying to help them get their head right so that when they get popped by a kid who really actually does wanna hurt them, then they give it back instead of folding up like a lawn chair’. (GF4)

Discussion

We conducted a qualitative interview study (framed using the TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) to elucidate factors influencing coach communication with youth athletes about contact and injury risk in sport, with a goal of informing interventions utilizing coach communication about good and bad contact as a means to injury prevention. We assessed how coaches perceived and talked about contact with their athletes to determine: 1) coach perception of appropriate and acceptable content for messaging regarding contact and 2) barriers and facilitators to coaches talking about good and bad contact with their athletes. Football and soccer coaches could clearly describe good and bad contact (Knowledge/experience) and they recognized the connection between bad contact and injury (Attitudes/beliefs). They also believed it was their role to teach youth athletes about contact and injury risk (Norms/values), while emphasizing that all adult stakeholders (referees, parents, administrators) had a role to play. They felt comfortable having these discussions (Self-efficacy) and most believed that discussions with athletes about contact could decrease injury (Response efficacy), but they also raised concerns that talking about contact would take time, might not be effective and might cause a fear of injury. Stakeholders from both football and soccer felt it was essential to correct bad contact when it occurred. However, when talking before a game, they preferred to focus on the positive (i.e. ‘Keep your head up’ rather than ‘Don’t put your head down’). Coaches rarely discussed institutional guidance about addressing contact in the coach role.

Asking football coaches to talk to athletes about contact would be relatively straightforward given stakeholder recognition about the need to prevent concussive injury in football, and an acceptance that certain types of contact (such as tackling with head down) are associated with greater likelihood of concussion (Obana et al., Citation2021). In addition, the effective implementation of programs such as Heads Up Football® (Matsuo et al., Citation2018; Shanley et al., Citation2021; Tokish et al., Citation2017) and the frequent use of terms like ‘hawk tackling’ and ‘rugby style tackling’ suggest the cultural acceptance of teaching good and bad contact as a means for reducing injury risk in football. Efforts to reduce concussive injury in football have been more urgent in recent years with reports of declining enrollment (McGlynn et al., Citation2020). Some organizations have even chosen to institute injury prevention programs such as Heads Up Football® with a goal of improving the image of youth football for concerned parents.

Soccer, on the other hand, has a more challenging culture in which to promote discussions about contact and injury as key stakeholders are conflicted about whether concussion is a significant issue in the sport (Kim & Connaughton, Citation2021), even with studies showing a relatively high incidence of concussion in soccer (Bretzin et al., Citation2021). In addition, research on the mechanism of soccer concussions is still in its infancy, and other than heading, which is known to be associated with greater likelihood of colliding with another player and thus sustaining an injury (Comstock et al., Citation2015), it is not clear which types of soccer contact place an athlete at greater risk for concussion. Interestingly, heading was not a frequent theme in these interviews, perhaps because avoiding a collision during a heading attempt is more complex and would require greater training (Quintero et al., Citation2020). The soccer stakeholders in the sample mentioned concerns about ‘aggressive play’ and ‘not tackling from behind’ which are thought to be potentially more injurious, but evidence linking these behaviors to injury is scant. Even soccer rules are vague on this concept, suggesting that ‘playing in a dangerous manner’ could be grounds for a foul, but not defining what is meant by ‘a dangerous manner’. Injury prevention programs in soccer have primarily focused on strength and conditioning and have not addressed aggressivity or ‘bad’ contact. Recent surveys of parents suggest growing concern about concussion in youth soccer which the sport will need to address in some fashion (Kim & Connaughton, Citation2021). While it is possible that discussing good and bad contact in soccer could be an effective means towards injury prevention, more work will need to be done to understand how to implement such an approach.

It is notable that coaches were hesitant to have discussions about contact that ‘went negative’, expressing concern that this might spark fear of injury in their players and cause them to back off in terms of aggressivity, often a necessary part of success in sport. Interestingly, a focus on positive instruction is recommended for other types of behavior change, as instruction that focuses on the negative (e.g. ‘Don’t bend your elbow’) tends to increase a behavior compared to the same command framed positively (e.g. ‘Keep your arm straight’) (Evans & Tuttle, Citation2015). In other words, in the context of football one could talk about ‘keeping your head up’ and for soccer ‘using your shoulder or hips to box them out’. Framing communication positively and focusing on the desired behavior rather than the undesired behavior is a more effective approach, and should be considered for future interventions utilizing communication about contact.

Perhaps one of the deeper questions this research raises is the issue of balancing aggression and injury risk in sport, an underlying issue for all sports. Athletes at the highest levels of competition always risk the possibility of causing injury to themselves or others. They do not enter into competitions with a goal of hurting their opponent; their goal is to win. As public health researchers, our job is to provide coaches, athletes and sporting organizations/national governing bodies (NGBs) information about strategies to mitigate injury risk that allow them to continue to grow the sport they love. Football has changed many times over the years in an effort to make the game safer, including outlawing the flying wedge (McQuilkin & Smith, Citation1993), developing the forward pass (Watterson, Citation1981) and prohibiting spearing (Heck, Citation1992). Utilizing approaches with preventive messaging about contact (such as having the shoulder be the first point of contact rather than the head) has the potential to make football safer, particularly for youth. However, in order for this type of approach to be successful, the messaging needs to be 1) mandated by the league and 2) implemented in a way that fits with the culture of the sport.

Limitations

The goal of this study was to identify factors influencing coach communication with youth football and soccer players about contact and injury risk, and we interviewed 50 individuals from two states (Washington and Georgia) as a strategy towards developing a more generalizable sample. However, despite our careful sampling, the individuals we interviewed were predominately male (86%) and white (86%), which unfortunately represented the individuals who worked in these spaces, even in Georgia which had greater racial diversity. We acknowledge that females and people of color might have different approaches to thinking about good and bad contact and further work will need to be carried out to ensure their voices are included. We also acknowledge that the inferences we make in this paper are still only theoretic, and quantitative work is needed to explore the strength of these factors and the pathways whereby they might influence stakeholder communication in greater detail.

Conclusions

Most coaches in youth football (i.e. American football) and soccer know that certain types of contact like targeting another player can be dangerous, and they teach their athletes to engage in ‘good’ contact to minimize risk of injury. Youth coaches appear to employ purposeful communication strategies regarding contact, focusing on positive instructions like: ‘keep your head up’ and ‘play the ball not the player’. However, while referees have a clear mandate regarding player safety, coaches are not usually told by their organizations that managing contact is part of their role. Future sport injury prevention programs developed by academicians, sporting organizations or NGBs (National Governing Bodies) might consider a greater role for coach communication about approaches to engaging in contact that minimize injury risk.

Author contributions

Sara Chrisman applied for and received grant funding to carry out the study (MPI), developed and refined the structured interview, oversaw data collection and analysis including interpretation of results, and generated the final manuscript.

Emily Kroshus worked alongside Dr. Chrisman to apply for and received grant funding (MPI) to carry out the study, participated in the generation of the structured interview and data analysis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Rachel Hays supported development of the structured interview, coordinated all data collection and participated in analysis and interpretation, supporting several research coordinators to carry out data coding and synthesis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Erin Kinney helped refine the structured interview, conducted interviews of participants in Washington, engaged in data coding and synthesis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Kiana Hafferty helped refine the structured interview, conducted interviews of participants in Washington, engaged in data coding and synthesis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Beth Bollinger supported data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Tamerah Hunt oversaw data collection in Georgia including completing some of the interviews, participated in data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Nicole Walden conducted interviews of participants in Georgia, engaged in data coding and synthesis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Stephanie Fletcher conducted interviews of participants in Georgia, engaged in data coding and synthesis, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

George Chiampas assisted with development of the grant for funding, provided support and engagement for data collection, helped develop the structured interview, participated in data interpretation, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Dane Ramshaw assisted with development of the grant for funding, provided educational resources for the study to assist with data collection, developed conceptual model materials, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Kirsten Senturia oversaw all qualitative data collection including development of the structured interview, training and supervision of research coordinators to complete data coding and synthesis, and engagement with final data interpretation, including reviewing and editing the final manuscript.

Ann Glang supported development of the grant for funding, worked with MPIs Kroshus and Chrisman to engage coaches and other key stakeholders, participated in data analysis and interpretation and reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the youth coaches, referees and administrators in Washington and Georgia without whom this study would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Chiampas is chief medical officer for U.S. Soccer. The authors otherwise have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The authors have agreed to make data and materials supporting the results or analyses presented in this paper available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sara P. D. Chrisman

Drs. Chrisman and Kroshus are researchers at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and have worked together for several years to develop a novel injury prevention program (Huddles), in partnership with US Soccer. Dr. Chrisman is a pediatrician, epidemiologist and physician scientist and Dr. Kroshus is a social scientist and implementation specialist.

Emily Kroshus

Drs. Chrisman and Kroshus are researchers at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and have worked together for several years to develop a novel injury prevention program (Huddles), in partnership with US Soccer. Dr. Chrisman is a pediatrician, epidemiologist and physician scientist and Dr. Kroshus is a social scientist and implementation specialist.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Bazeley, P. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: Practical strategies. Sage.

- Black, A. M., Hagel, B. E., Palacios-Derflingher, L., Schneider, K. J., & Emery, C. A. (2017). The risk of injury associated with body checking among Pee Wee ice hockey players: An evaluation of Hockey Canada?s national body checking policy change. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51bjsports-097392. (24), 1767–1772. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097392

- Black, A. M., Macpherson, A. K., Hagel, B. E., Romiti, M. A., Palacios-Derflingher, L., Kang, J., Meeuwisse, W. H., & Emery, C. A. (2016). Policy change eliminating body checking in non-elite ice hockey leads to a threefold reduction in injury and concussion risk in 11- and 12-year-old players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095103

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bretzin, A. C., Covassin, T., Wiebe, D. J., & Stewart, W. (2021). Association of sex with adolescent soccer concussion incidence and characteristics. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e218191. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8191

- Chrisman, S. P. D., Kroshus, E., Hays, R., Kinney, E., Hafferty, K., Bollinger, B. J., Hunt, T., Walden, N., Walsh, S., Chiampas, G., Ramshaw, D., Senturia, K. D., & Glang, A. (2022). A qualitative study of factors influencing adult stakeholder concussion communication with youth athletes. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(7), 1138–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2083664

- Comstock, R. D., Currie, D. W., Pierpoint, L. A., Grubenhoff, J. A., & Fields, S. K. (2015). An Evidence-Based Discussion of Heading the Ball and Concussions in High School Soccer. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(9), 830–837. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1062

- Dedoose (2018). Dedoose version 8.0.35, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed methods research data. SocioCultural Reearch Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

- Emery, C. A., Kang, J., Shrier, I., Goulet, C., Hagel, B. E., Benson, B. W., Nettel-Aguirre, A., McAllister, J. R., Hamilton, G. M., & Meeuwisse, W. H. (2010). Risk of Injury Associated With Body Checking Among Youth Ice Hockey Players. JAMA, 303(22), 2265–2272. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.755

- Emery, C. A., & Pasanen, K. (2019). Current trends in sport injury prevention. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 33(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2019.02.009

- Evans, K., & Tuttle, N. (2015). Improving performance in golf: Current research and implications from a clinical perspective. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 19(5), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0122

- Guskiewicz, K. M., & Mihalik, J. P. (2011). Biomechanics of sport concussion: Quest for the elusive injury threshold. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 39(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e318201f53e

- Heck, J. F. (1992). The incidence of spearing by high school football ball carriers and their tacklers. Journal of Athletic Training, 27(2), 120–124.

- Howell, D. R., Kirkwood, M. W., Laker, S., & Wilson, J. C. (2020). Collision and Contact Sport Participation and Quality of Life Among Adolescent Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(11), 1174–1180. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-0536.19

- Kerr, Z. Y., Dalton, S. L., Roos, K. G., Djoko, A., Phelps, J., & Dompier, T. P. (2016). Comparison of Indiana high school football injury rates by inclusion of the USA Football “Heads Up Football” player safety coach. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 4(5), 2325967116648441. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967116648441

- Kerr, Z. Y., Kroshus, E., Lee, J. G. L., Yeargin, S. W., & Dompier, T. P. (2017). Coaches implementation of the USA Football Heads Up Football educational program. Health Promotion Practice, 19(2), 184–193. 152483991770039–152483991770039. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839917700398

- Kim, S., & Connaughton, D. P. (2021). Soccer, concussions, and safety: Perceptions of parents of youth soccer participants. Journal of Safety Research, 77, 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2021.03.008

- Kroshus, E., Babkes Stellino, M., Chrisman, S. P. D., & Rivara, F. P. (2018). Threat, Pressure, and Communication About Concussion Safety: Implications for Parent Concussion Education. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 45(2), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198117715669

- Kroshus, E., & Chrisman, S. P. D. (2019). A New Game Plan for Concussion Education. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 46(6), 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119859414

- Kroshus, E., Garnett, B., Hawrilenko, M., Baugh, C. M., & Calzo, J. P. (2015). Concussion under-reporting and pressure from coaches, teammates, fans, and parents. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 134, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.011

- Langhorst, P. (2016). Youth sports participation statistics and trends. Engage Sports. http://www.engagesports.com/blog/post/1488/youth-sports-participation-statistics-and-trends

- Maher, M. E., Hutchison, M., Cusimano, M., Comper, P., & Schweizer, T. A. (2014). Concussions and heading in soccer: A review of the evidence of incidence, mechanisms, biomarkers and neurocognitive outcomes. Brain Injury, 28(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2013.865269

- Marshall, S. W., Guskiewicz, K. M., Shankar, V., McCrea, M., & Cantu, R. C. (2015). Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in seven US high school and collegiate sports. Injury Epidemiology, 2(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-015-0045-4

- Matsuo, H., Yamada, Y., Masuchi, K., & Matsumoto, T. (2018). Effectiveness of the Heads Up Tackling (HUT) program on tackling safety and performance in American football. International Journal of Sport and Health Science, 16(0), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.5432/ijshs.201804

- McGlynn, J., Boneau, R. D., & Richardson, B. K. (2020). “It Might Also Be Good for Your Brain”: Cognitive and Social Benefits That Motivate Parents to Permit Youth Tackle Football. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 44(3), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520903226

- McQuilkin, S. A., & Smith, R. A. (1993). The Rise and Fall of the Flying Wedge: Football’s Most Controversial Play. Journal of Sport History, 20(1), 57–64.

- Obana, K. K., Mueller, J. D., Zhong, J. R., Saltzman, B. M., Lynch, T. S., Parisien, R. L., Ahmad, C. S., & Trofa, D. P. (2021). Targeting rule implementation decreases neck injuries in high school football: A national injury surveillance study. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 50(4), 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2021.1932630

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Patton, M. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Quintero, L. M., Moore, J. W., Yeager, M. G., Rowsey, K., Olmi, D. J., Britton-Slater, J., Harper, M. L., & Zezenski, L. E. (2020). Reducing risk of head injury in youth soccer: An extension of behavioral skills training for heading. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(1), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.557

- Register-Mihalik, J. K., Guskiewicz, K. M., McLeod, T. C. V., Linnan, L. A., Mueller, F. O., & Marshall, S. W. (2013). Knowledge, Attitude, and Concussion-Reporting Behaviors Among High School Athletes: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Athletic Training, 48(5), 645–653. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-48.3.20

- Shanley, E., Thigpen, C., Kissenberth, M., Gilliland, R. G., Thorpe, J., Nance, D., Register-Mihalik, J. K., & Tokish, J. (2021). Heads Up Football Training Decreases Concussion Rates in High School Football Players. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 31(2), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000711

- Statacorp. (2015). Stata Statistical SoftwareL Release 14. Statacorp LP.

- Tokish, J. M., Shanley, E., Kissenberth, M. J., Brooks, J., Nance, D., Gilliland, R. G., & Thorpe, J. (2017). Heads Up Football Training Decreases Concussion Rates in High School Football Players. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 5(3_suppl3), 2325967117S0013. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967117S00131

- Voormolen, D. C., Polinder, S., von Steinbuechel, N., Vos, P. E., Cnossen, M. C., & Haagsma, J. A. (2019). The association between post-concussion symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Injury, 50(5), 1068–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.12.002

- Warsh, J. M., Constantin, Ş. A., Howard, A., & Macpherson, A. (2009). A Systematic Review of the Association Between Body Checking and Injury in Youth Ice Hockey. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 19(2), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181987783

- Watterson, J. S. (1981). The football crisis of 1909-1910: The response of the Eastern “Big Three. Journal of Sport History, 8(1), 33–49.

- Willigenburg, N. W., Borchers, J. R., Quincy, R., Kaeding, C. C., & Hewett, T. E. (2016). Comparison of injuries in american collegiate football and club rugby. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(3), 753–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515622389

- Yang, J., Harvey, H. H., Sullivan, L., Huang, L., & Dawn Comstock, R. (2021). Association between design elements of concussion laws and reporting of sports-related concussions among US high school athletes, 2009-2017. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974), 13633354920988611. (6), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920988611