Abstract

This systematic review explores Long-Term Services and Support (LTSS) for older individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) in Africa. Guided by the research question, what is the current state of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in Africa? The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses approach and a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach were adopted to analyze various aspects of LTSS, including types, accessibility, affordability, impact on families and caregivers, social inclusion and cultural influences. A systematic search of relevant literature sources was conducted, and data were synthesized to provide a holistic view of the challenges and opportunities in this field. The review reveals a significant gap in indigenous research and emphasizes the need to recognize the unique needs of older adults with IDD in Africa. Challenges related to accessibility, affordability and social inclusion persist, while cultural factors play vital roles in shaping the provision of LTSS. Family caregivers face increasing demands, leading to stress and psychological burden. These findings call for urgent attention to the provision of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in Africa. By addressing the identified challenges and promoting culturally sensitive and inclusive services, policymakers can enhance the well-being and social inclusion of this vulnerable population.

Impact Statement

This manuscript presents findings of investigating into the long-term care support and services for older adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) in Africa. Using a rigorous research investigation procedure, this study shed more light on the challenges and the need for interventions for the care of older adults with intellectual disabilities in Africa.

The findings of this study contribute to filling the research gap in the area of long-term care for older adults with intellectual disabilities in Africa. Also, by projecting the challenges, the findings prompt the need for policy amendment. Thus, the findings call for policymakers to work towards improving the quality of care for older people with intellectual and developmental disabilities especially in Africa. Finally, the findings of this study encourage the need for a more inclusive society.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Health disparities affect people with disabilities, particularly those living with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) (Alonso-Sardón et al., Citation2019; Krahn et al., Citation2015; Marks et al., Citation2019). IDD encompasses various neuro-developmental conditions, including intellectual disabilities like Down Syndrome and developmental disabilities such as cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorder (Stirling et al., Citation2021). It may also be as a result of trauma, illness, or neurological conditions relating to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, fragile X syndrome, birth deformities, infections, or complications during childbirth (Karam et al., Citation2015). More commonly in Africa, IDD is attributed to supernatural consequences as a form of divine retribution (Kisanji, Citation1998; Mckenzie et al., Citation2013; Mung’omba, Citation2008). As such, mostly during religious discourse in Africa, people with intellectual or developmental impairments are seen as ‘gifts from God,’ symbolizing a challenge to the faith and resilience of their family members (Rohleder & Swartz, Citation2009). But unknowingly, these beliefs usually have detrimental consequences for the individual with the impairment. Commonly, older adults with IDD experience heightened social rejection, stigma, abuse, bullying which leads to them experiencing loneliness culminating to a reduced quality of life (Emerson et al., Citation2021; Harpazi, Regev & Snir, Citation2022; Power, Citation2008; Roll & Koehly, Citation2020; Stenfert Kroese et al., Citation2016; van Asselt-Goverts et al., Citation2015).

Likewise, aging with intellectual disabilities is a complex process, characterized by a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions (such as respiratory diseases) and psychiatric disorders (like psychotic disorders) compared to the general population of the same age (Alftberg et al., Citation2021; Evenhuis et al., Citation2012; McCausland et al., Citation2016; Shooshtari et al., Citation2012). But, notable in developing countries, whilst health disparities persist, the unfortunate issue relates to inadequate access (Krahn et al., Citation2015). Among older adults living with IDD, a systematic review conducted earlier revealed that they frequently experience physical health issues often, related to their primary impairment or unrecognized secondary diseases (Haveman et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, Eady et al. (Citation2015) acknowledged that adults with IDD have a higher likelihood of experiencing health issues and are more vulnerable to the side effects of untreated psychopharmacology and polypharmacy.

In the past, individuals with severe IDD primarily resided in large institutions referred to as ‘congregate care environments’. Most common among such institutions were operated by states (Braddock & Heller, Citation1985). These facilities housed about 30 to 200 people and were believed to provide better care, protect individuals from adverse living conditions and offer opportunities to acquire life skills for future reintegration into society (Anderson et al., Citation2021; Kelly et al., Citation2021; Matheis, Citation2019). As the baby boomer generation approaches their retirement age, there has been an increased demand for care services, including those for individuals with IDD. As such, society’s perception of disability is shifting from the medical model to the social model (Lawson & Beckett, Citation2021), emphasizing that individuals with disabilities including those with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD) can lead a healthier life through home-based care services for individuals with IDD, with the intent of promoting community living and social inclusion (Krahn et al., Citation2015). Through this approach, additional efforts have been developed including, regular health checks (Robertson et al., Citation2014), comprehensive geriatric assessments with in-home preventive measures (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2015; Janicki & Keller, Citation2014), health education programs (Marks et al., Citation2010) and health advocacy (Robertson et al., Citation2014). In the US, the adoption of Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) and the Medicaid waiver option have encouraged community housing and supported social inclusion (Larson et al., Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2011).

Earlier, even though, social inclusion remained a crucial aspect of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRD) and a vital component for enhancing the well-being of individuals with IDD (Buntinx & Schalock, Citation2010), the challenge of achieving social inclusion for individuals with IDD stemmed also from the poor understanding of the concept (Amado et al., Citation2013; Cobigo et al., Citation2012; Overmars-Marx et al., Citation2014). Social inclusion had differing descriptions which included terms like social networks, community participation and social capital. Due to these variations with different meanings, disparities that hindered effective implementation and service delivery (Duggan & Linehan, Citation2013; Martin & Cobigo, Citation2011). Also, hindered communication among key stakeholders, including individuals with disabilities, their families, service providers, academics and policymakers, who may have differing views on the definition and objectives of social inclusion (Clement & Bigby, Citation2009). Subsequently, social inclusion for individuals with disabilities has evolved and now considers developmental factors and emphasizes individuals’ rights to specialized health, education, support and services needed to improve their welfare (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Patel et al., Citation2018; Salvador-Carulla et al., Citation2013).

Consequently, among older adults living with IDD, their needs for assistance are expected to grow and become more diverse as they navigate these intricate aging processes. But, regardless of IDD being one of the most prevalent disabilities in Africa (Bornstein & Hendricks, Citation2013; Glasson & Bittles, Citation2008), there is a notable scarcity of research on the subject (McKenzie et al., Citation2013). Not forgetting that to encourage healthy aging, improve quality of life (QOL) and lengthen the lifespan of people with IDD requires targeted research (Hahn et al., Citation2015). As such, informs the easier approach to plan and create the required supports and services for older people as they age as well as to discover potential preventative measures in earlier years with the use of data on the health and aging of persons with IDD. There is therefore the need to have a comprehensive understanding of the diverse care needs of older individuals with intellectual disabilities and how to provide appropriate support at this stage of life. In pursuit of this objective, this paper conducts a systematic review focused on long-term services and support (LTSS) for older individuals with IDD in Africa. A systematic review is chosen to methodically analyze existing research on LTSS for older individuals with IDD in Africa. This approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the subject, identifies gaps in knowledge and provides evidence-based insights to inform future policies and practices, ultimately advancing discourse and improving the well-being of this population.

2. Methods

2.1. Design, question and objectives

This study employed a systematic review design to comprehensively synthesize existing evidence and provide a rigorous overview on the landscape of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in African countries. This approach was selected for its methodological rigor, transparency and capacity to comprehensively assess the topic area and generate findings that is robust, reliable and valuable for both academic research and practical applications in the field of healthcare and disability services (Bennett et al., Citation2005). Also, guided by the question: What is the current state of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in African countries? This systematic review sought to summarize key findings related to availability, accessibility, quality of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in African countries, gaps in the existing literature, highlighting areas requiring further research.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Through the systematic review, studies published in peer-reviewed journals, reports and qualitative research conducted within African countries were considered. Participants of interest were older adults aged 50 years and above and more specifically those living with IDD. Time frame considered for the systematic review included literatures published between 2000 and 2023 (which provides a robust foundation for the systematic review, offering a holistic view of the historical context and recent developments in the field of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in African countries). Additionally, the review focused on studies published in English or those accompanied by English translations. Also, the exclusion criteria led to ignoring studies that centered on populations aged 49 years and below. This criterion is essential to maintain the study’s specific focus on older people and above with IDD. This procedure allowed for a more in-depth analysis of the unique challenges and needs of this demographic. Geographic scope was limited to Africa. That is, literatures originating from regions outside Africa was not considered. Relevance to IDD and LTSS: Studies that do not focus on IDD or those that addressed IDD but not within the context of LTSS were excluded. This ensured that the review aligned with its core research objectives, specifically concerning older individuals with IDD and the LTSS in African countries.

2.3. Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant literatures. Databases including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and African Journals Online (AJOL) were systematically searched using keywords and controlled vocabulary terms related to LTSS, IDD, aging and Africa. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to combine search terms. Filters for publication date and study type were applied when appropriate. The search terms encompassed key concepts essential to the research, including ‘long-term services and support’ AND ‘intellectual and developmental disabilities’ OR ‘aging’ AND ‘Africa ‘OR’ Sub-Saharan Africa ‘OR’ Southern Africa’. Using AND required that both ‘long-term services and support’ and ‘intellectual and developmental disabilities’ be present in the retrieved documents, narrowing down results to those directly relevant to the intersection of these concepts. Conversely, employing OR expanded the search to include documents containing either ‘aging’ or ‘Africa’, ensuring all relevant studies were not missed. The comprehensive literature search was conducted from July 2023 to August 2023 to identify relevant studies on LTSS for older individuals with IDD in African countries.

This meticulous approach allowed for the construction of complex search queries that harnessed the logical relationships between the keywords, enabling easy identification of studies exploring the multifaceted landscape of LTSS for older individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the context of aging in African countries. During the quality assessment phase, each selected study underwent meticulous appraisal to identify potential sources of bias and assess methodological rigor.

2.4. Data collection and study selection

A rigorous process was established for collecting relevant studies. Duplicate records were removed using reference management software. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two researchers, followed by a full-text review of potentially relevant articles. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Researchers independently assessed each study for eligibility and, in cases of disagreement, a third researcher was consulted for resolution. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart was followed to document the study selection process (Moher et al., Citation2009).

2.5. Data extraction

Data were systematically extracted from selected studies, including study characteristics (eg author and publication year), participant demographics, interventions or LTSS models and key findings. A standardized data extraction form was used to measure consistency. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) data extraction form was used to ensure transparent reporting of data extraction methods (Moher et al., Citation2009, Citation2015, Citation2016).

2.6. Quality assessment

Quality assessment of the included studies was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal tool, which is specifically designed to evaluate various study types, including observational studies (Munn et al., Citation2019). This rigorous process involved two researchers independently assessing each study for quality. Any discrepancies or differences in the quality ratings were resolved through discussion and consensus. The JBI appraisal tool allowed for a systematic and objective evaluation of study quality, ensuring that only high-quality and relevant studies were included in the systematic review.

2.7. Data synthesis

The data synthesis process employed a narrative approach, which enabled us to effectively summarize the key findings and themes emerging from the selected studies. These findings encompassed critical aspects of LTSS in African countries, specifically focusing on their availability, accessibility and quality. While the consideration of a meta-analysis was initially contemplated, it was ultimately deemed inappropriate due to the considerable heterogeneity observed among the selected studies. This heterogeneity stemmed from variations in study design, methodologies and outcome measures across the diverse range of research included in the systematic review. As a result, the narrative synthesis approach was chosen as the most suitable method for presenting and analyzing the findings. This enabled comprehensive and coherent overview of the research landscape in this complex area (Popay et al., Citation2006).

3. Results

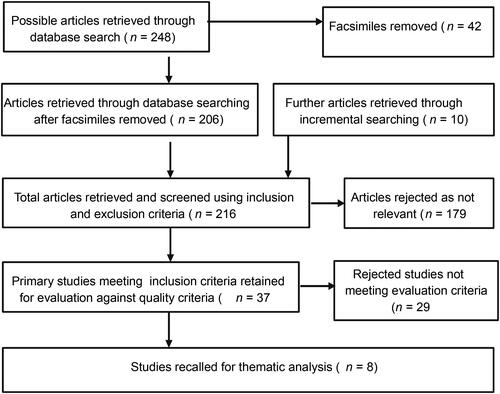

The initial database searches yielded a total of 248 articles. After removing 42 duplicate articles, we employed the snowballing or ancestor search method to identify relevant articles from the reference lists of the downloaded papers, resulting in the acquisition of 10 additional supplementary articles. This brought the total number of articles to 216 (subtracting the 42 duplicates). Further examination of the abstracts and introductions of the remaining articles led to the exclusion of 179 irrelevant articles. Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the review ultimately included 8 articles (see in the PRISMA diagram for study details).

Figure 1. Flow chart of studies included in the review based on PRISMA: adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2009).

Through a comprehensive review of the papers that matched the inclusion criteria, four key themes emerged regarding LTSS for older adults with IDD in Africa. These themes included disability-appropriate services, emphasizing accessibility and affordability; the impact on families and caregivers; information and knowledge gaps, including awareness and policy deficits; and the critical role of employment in fostering independence and inclusion. These themes collectively shed light on the challenges and opportunities in enhancing the lives of individuals with IDD in Africa, highlighting the need for comprehensive support and inclusive policies.

3.1. Disability-appropriate services

This theme explored the types, accessibility and affordability of services catering to individuals with disabilities. It encompasses healthcare, community-based initiatives, educational institutions and traditional healing practices. Accessibility refers to the ease of access, considering physical and geographical factors, inclusivity and accommodation of diverse disabilities. Affordability assesses financial aspects, including public funding, private fees, subsidies and NGO or international support, to ensure equitable access without financial hardship or barriers. Overall, this theme delved into disability-appropriate services, addressing various aspects to ensure their effectiveness and inclusivity.

3.1.1. Types of disability-appropriate services

The literature on disability-appropriate services in Africa reveals a range of essential provisions aimed at addressing the unique needs of individuals with disabilities. These services encompass community-based psychiatric inpatient units, which provide short-term inpatient care within general hospitals for individuals with intellectual developmental issues. Community residential facilities offer long-term residential care and support away from traditional psychiatric settings. Psychiatric hospitals, typically located in urban centers, serve as crucial institutions for mental health care delivery (Aldersey et al., Citation2017; Naami et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2014). Additionally, informal primary health care is provided by faith-based practitioners and traditional healers, contributing to holistic care for those seeking alternative therapies. The Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) program emphasizes community involvement and resource mobilization, empowering people with disabilities to participate fully in their communities. Furthermore, educational and training institutions offer specialized services, fostering the integration and inclusion of individuals with intellectual disabilities into mainstream society (Naami et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2014). These diverse services collectively contribute to enhancing the quality of life and social inclusion of persons with disabilities across Africa. However, confirmation of the absence of designated care or training programs for adults with severe and profound intellectual disabilities in South Africa highlights a critical gap in the existing support infrastructure (Terreblanche, Citation2015). This gap not only isolates individuals with severe and profound intellectual disabilities but also places an immense burden of care on their caregivers and families. Additionally, insufficient resources and logistical challenges present significant obstacles to the effective performance of duties by service providers not only hindering the provision of quality services but also posing challenges to ensuring the delivery of comprehensive and appropriate support to individuals with disabilities.

3.1.2. Accessibility of services

Despite the diverse services, they are notably skewed toward urban areas, which disadvantages individuals in rural settings (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). This spatial variance poses significant challenges in terms of accessibility and adequacy, particularly for older adults with intellectual disabilities in Africa. Rural populations, including older adults with intellectual disabilities, often face difficulties in accessing these services due to geographical limitations and limited infrastructure (Naami et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2014). This disparity highlights the need for targeted efforts to bridge the accessibility gap and ensure that disability-appropriate services reach all individuals, regardless of their geographic location, thus promoting greater inclusivity and equity in service delivery across the continent.

3.1.3. Affordability of services

The literature on disability-appropriate services in Africa highlights a diverse array of provisions aimed at catering to individuals with disabilities, including older adults with intellectual disabilities. While these services vary in their types and objectives, they collectively contribute to enhancing the quality of life and social inclusion of individuals with disabilities across the continent. However, when it comes to affordability, challenges emerge. Many individuals and families, including older adults with intellectual disabilities, face financial constraints that limit their access to these services (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). Affordability issues often lead to underutilization or non-utilization of critical disability services, as individuals struggle to cover the associated costs (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). This financial barrier highlights the importance of implementing policies and initiatives aimed at improving the affordability of disability-appropriate services, ensuring that they are accessible to all individuals, irrespective of their economic circumstances. Such efforts can significantly enhance the overall well-being and inclusion of the population of interest in Africa.

3.2. Long-term services, families and caregivers

This theme sheds light on the significant impact these services have on families and caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities. It highlights the challenges faced by families in balancing long-term care responsibilities and underscores the concerns related to providing lifelong support to their loved ones with disabilities. This theme delves into the complexities and demands faced by caregivers and families as they navigate the journey of caring for individuals with intellectual disabilities throughout their lives.

3.2.1. Impact on families and caregivers

The availability of long-term services for older adults with intellectual disabilities has a profound impact on their caregivers. These services provide much-needed respite and support to caregivers who often bear the responsibility of caring for their loved ones with disabilities throughout their lives. When such services were readily available, caregivers experienced relief from the physical, emotional and financial burdens associated with providing continuous care. It allows them to have breaks, focus on their well-being, pursue employment opportunities and maintain a better quality of life (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). Additionally, accessible long-term services contribute to reducing the stress and burnout that caregivers face, enhancing their overall ability to provide care effectively and ensuring a higher quality of life for both caregivers and individuals with intellectual disabilities (Naami et al., Citation2022; Terreblanche, Citation2015). However, challenges arise due to the adequacy of these services and the costs involved, placing additional strain on caregivers and limiting their capacity to provide optimal care.

3.2.2. Concerns for lifelong support

Concerns for lifelong support reveal the profound worries surrounding the inadequacy of services for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa. Caregivers and families express deep concerns about how these individuals can achieve independence and lead fulfilling lives (Wanjagua, Citation2018). The limited availability of appropriate services often results in the infantilization of adults with intellectual disabilities, as services are not tailored to support their independence (Capri & Swartz, Citation2018). This lack of comprehensive, lifespan-oriented services raises critical questions about the quality of life, social inclusion and autonomy of individuals with intellectual disabilities as they age. Families and caregivers are burdened by the responsibility of providing ongoing care and support, and they face challenges in balancing these responsibilities with work and other commitments. In essence, the literature highlights the pressing need for more holistic and empowering services to address the lifelong needs of individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa and ensure they can lead self-reliant and meaningful lives.

3.3. Information and knowledge gaps

The literature reveals significant gaps in both public awareness and professional knowledge regarding intellectual disabilities, contributing to stigma and misconceptions. Additionally, the lack of professional psychological support exacerbates the challenges faced by individuals and families dealing with intellectual disabilities. Moreover, the absence of comprehensive government policies and guidelines hinders the development and implementation of effective services and support systems for this population. These issues collectively highlight the urgent need for increased awareness, education and policy development to address the information and knowledge gaps surrounding intellectual disabilities in Africa and to improve the quality of life and inclusion of individuals with these disabilities.

3.3.1. Limited understanding of intellectual disabilities

The limited understanding of intellectual disabilities in Africa is a significant challenge revealed in the literature (Wanjagua, Citation2018). This lack of understanding contributes to widespread stigma and misconceptions surrounding intellectual disabilities. It hinders the social inclusion and acceptance of individuals with intellectual disabilities and their families. Additionally, this limited understanding often leads to discrimination and a lack of appropriate support services for this population (Wanjagua, Citation2018). The prevailing misconceptions and stigma not only isolate individuals with intellectual disabilities but also hinder their access to vital support services (Meer & Combrinck, Citation2017). Due to this lack of comprehension, there is often a failure to tailor services to their specific needs, resulting in inadequate support structures. Furthermore, the underestimation of the capabilities and potential contributions of individuals with intellectual disabilities can lead to missed opportunities for their active participation in various aspects of life, including education, employment and community engagement.

3.3.2. Lack of professional psychological support

The lack of professional psychological support for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa is closely linked to the limited understanding of intellectual disabilities in the region. Due to this limited comprehension, there is a shortage of health professionals who are adequately trained and equipped to provide specialized care for individuals with intellectual disabilities (Aldersey et al., Citation2017; Wanjagua, Citation2018). This shortage has significant consequences for the mental well-being of individuals with intellectual disabilities, as they often struggle with co-occurring mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression. Moreover, the absence of professional psychological support places a substantial burden on families and caregivers, who are left without the necessary guidance and resources to address the emotional and psychological needs of their loved ones with intellectual disabilities.

3.3.3. Insufficient government policies and guidelines

The limited availability of professional psychological support for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa is exacerbated by the absence of sufficient government policies and guidelines. The lack of clear and comprehensive governmental frameworks for addressing the mental health and well-being of individuals with intellectual disabilities leaves a regulatory vacuum (Naami et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2014). This results in an inadequate allocation of resources and a failure to prioritize the development of specialized psychological support services for this population (Wanjagua, Citation2018). Consequently, individuals with intellectual disabilities and their families continue to face significant barriers in accessing the mental health services they require, perpetuating the existing disparities in care and support.

3.4. Employment and independence

The theme of employment and independence underscores the vital role of employment in fostering independence and social inclusion for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa. Employment opportunities are highly valued, as they provide a sense of purpose, financial autonomy and social interaction, allowing individuals to make choices in their lives. However, the limited availability of employment options, coupled with educational gaps and societal attitudes, often hinders the attainment of independence for this population, emphasizing the need for comprehensive support and inclusive policies.

3.4.1. Importance of employment for independence

The importance of employment for independence is underscored by the findings in the study. Individuals with intellectual disabilities, their families and caregivers expressed a strong desire for employment as it fosters a sense of independence, social interaction and the ability to make choices in life (Van Niekerk et al, Citation2015). Employment provides these individuals with a purpose and a means to contribute to society, which enhances their self-esteem and self-worth. Additionally, employment empowers individuals with intellectual disabilities by giving them the ability to make choices about their lives, including how they want to spend their income and plan for their future. This sense of control and autonomy is essential for their overall well-being and quality of life. However, they often encounter significant challenges in securing employment opportunities.

3.4.2. Limited employment opportunities and education gaps

The lack of specialized training programs and educational opportunities for adults with severe and profound intellectual disabilities results in a dearth of skills and qualifications that would make them competitive in the job market (Terreblanche, Citation2015; Wanjagua, Citation2018). Without access to appropriate education and vocational training, these individuals are often relegated to entry-level jobs or menial tasks, which limits their employment prospects. Furthermore, the absence of accredited qualifications and training facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities in many African countries means that they face stiff competition with the general population for low-skilled jobs (Terreblanche, Citation2015; Wanjagua, Citation2018). This competition, coupled with negative societal attitudes and prejudices, creates significant barriers to employment. As a result, many individuals with intellectual disabilities struggle to find suitable employment opportunities that could enhance their independence and quality of life.

3.4.3. Social isolation and disenfranchisement

The findings reveal that social isolation and disenfranchisement are prevalent challenges faced by individuals with IDD in Africa. These individuals often experience limited social interaction and exclusion from various aspects of community life. This isolation is attributed to several factors, including the lack of appropriate support services, the stigma associated with intellectual disabilities and the absence of community-based programs that promote inclusion (Terreblanche, Citation2015; Wanjagua, Citation2018). Moreover, the results suggest that negative attitudes and prejudices in society contribute to the social isolation of individuals with intellectual disabilities, as they are often perceived as burdensome or incapable of meaningful social participation (Meer & Combrinck, Citation2017). Consequently, this isolation further exacerbates their disenfranchisement and hinders their ability to lead fulfilling and independent lives.

4. Discussion

The systematic review of LTSS for older individuals with IDD in Africa reveals diverse service provisions, including psychiatric units, community initiatives, education institutions and traditional healing practices, targeting unique disability needs. Nevertheless, challenges emerge concerning accessibility, affordability and adequacy, especially in rural areas, impacting older adults with intellectual disabilities. Caregivers face substantial burdens, necessitating accessible long-term services. Lifelong support concerns, limited understanding of intellectual disabilities, insufficient professional psychological support and inadequate government policies compound these challenges. Employment’s vital role in fostering independence is emphasized, but limited opportunities and education gaps hinder realization. Social isolation and disenfranchisement persist due to societal attitudes and insufficient support structures. These findings underscore the multifaceted challenges faced by individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa, emphasizing the need for comprehensive, inclusive support.

4.1. Services, availability and affordability

There is diversity in long-term services catering for older adults with IDD; encompassing a wide spectrum, ranging from institutionalized care centers situated within healthcare facilities to community-based home care services. Within this continuum, various options are available to address the unique needs and preferences of individuals with IDD as they age. Formalized institutions, commonly known as ‘congregate care environments’, accommodate a varying number of individuals, typically ranging from 30 to as many as 200 residents, as indicated by studies conducted by Anderson et al. (Citation2021) and Kelly et al. (Citation2021). These settings serve as structured facilities designed to provide care and support for individuals with disabilities, offering a range of services and resources to meet their unique needs. Institutionalized care centers often provide comprehensive, round-the-clock support within a structured and supervised environment, ensuring that individuals receive the necessary care, medical attention and assistance with daily activities. Within this set up, issues of overcrowding sometimes hinder personalized care and autonomy, while fostering social isolation and limiting community engagement (Burrell & Trip, Citation2011; Šiška & Beadle-Brown, Citation2023).

This care model raises concerns about abuse, neglect and stigma perpetuation, along with financial burdens and challenges transitioning to community-based settings, questioning the overall quality of support and residents’ quality of life. The shift in the philosophy of care toward a communal approach for individuals with IDD, enabling them to live and engage within their communities, became prominent as public awareness of institutional life grew. This transition was facilitated by the widespread adoption of the Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Medicaid waiver option, encouraging community housing and support for those who would otherwise be in institutional settings. Significant policy and program reforms have led to numerous individuals with IDD leaving institutions, resulting in many states closing their facilities (Smith et al., Citation2011).

The study’s findings lend credence to this as community-based home care services prioritize enabling older adults to remain in their familiar environments, offering support tailored to their specific requirements while promoting independence and community integration were prevalent in the continent. The availability of such diverse options underscores the importance of person-centered care, where the choice of long-term service aligns with an individual’s preferences, functional abilities and goals. This diversity not only caters to the varied needs of older adults with IDD but also reflects the broader recognition of the importance of promoting autonomy, dignity and high quality of life as individuals age within these communities.

However, these services were not available everywhere. It is evident that despite the presence of policies and services for the population, there is a low priority in recognizing and addressing their needs. Specialized services are limited in number, primarily concentrated in urban areas and predominantly delivered by the state and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Naami et al., Citation2022; Roberts et al., Citation2014). Rural areas, on the other hand, lack adequate services and often resort to traditional beliefs and cultural practices to address intellectual disability and related issues (Meer & Combrinck, Citation2015). This spatial imbalance raised concerns regarding accessibility and equity in service delivery. Urban-centric service provision often posed challenges for individuals with intellectual disabilities residing in rural communities, as they encountered substantial barriers in accessing essential support.

The limited presence of these services in rural areas resulted in individuals having to travel considerable distances to access care, which was not only inconvenient but also financially burdensome. This spatial disparity underscored the need for targeted efforts to extend disability-appropriate services to rural regions, ensuring that individuals with intellectual disabilities, regardless of their geographic location, could access the support they require for improved quality of life and social inclusion. Further hindering the accessibility issue is the associated cost which burdens families and their caregivers, particularly those from poorer backgrounds (Knapp et al., Citation2005; Lunsky et al., Citation2019). To improve the accessibility and affordability of disability-appropriate services for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa, it is crucial to prioritize the development of specialized services in underserved areas, implement financial support mechanisms and raise awareness about intellectual disabilities.

4.2. Service availability: family and caregiver relief

The availability of services alleviates the physical, emotional and financial burdens faced by caregivers, allowing them respite, better well-being and employment opportunities. However, concerns persist about the adequacy of services and their cost, hindering caregivers’ ability to provide optimal care and raising questions about the independence and quality of life of individuals with intellectual disabilities as they age. The lives of individuals with IDD are profoundly influenced by their families, who often serve as their primary support system (Alonso-Sardón et al., Citation2019). These individuals typically reside with their caregivers, who are predominantly their parents (Friedman, Citation2019). While family remains the cornerstone of support, excessive dependence on them can impose a significant care burden and disrupt the lives of both individuals with IDD and their caregivers (Grey et al., Citation2018).

Therefore, the availability of appropriate services plays a pivotal role in alleviating this burden, contributing to a more balanced and less complicated life for both caregivers and families. In contrast, it is crucial to acknowledge that these support services are often insufficient, difficult to access and financially out of reach for some individuals with IDD (Naami et al., Citation2022; Smith et al., Citation2011). This glaring inadequacy, coupled with limited accessibility and affordability, can have profound implications for the aging population of individuals with IDD. Without adequate support, the quality of life for these individuals may diminish as they face barriers to essential services and care. The inaccessibility of services can lead to social isolation, limiting their opportunities for community engagement and meaningful interactions (Wanjagua, Citation2018).

Furthermore, the financial constraints associated with unaffordable services may result in underutilization or non-utilization of critical disability services, leaving them without the necessary care and support they require (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). Ultimately, these challenges could significantly impact the long-term aging experience of this population, potentially leading to a lower quality of life and reduced independence in their later years.

4.3. Knowledge gaps

The study underscores substantial knowledge and information gaps related to intellectual disabilities in Africa, contributing to widespread stigma and misconceptions. This limited understanding not only hinders social inclusion and acceptance but also leads to discrimination and a lack of appropriate support services for individuals with intellectual disabilities and their families. Furthermore, the dearth of professional psychological support, exacerbated by inadequate government policies and guidelines, poses significant challenges, leaving individuals and their caregivers without the necessary resources and guidance to address their emotional and psychological needs.

In several African countries, the perception of IDD is deeply influenced by cultural and spiritual beliefs (McNally & Mannan, Citation2013). Many people view IDD as a spiritual affliction, often attributing it to divine punishment (Naami et al., Citation2022). This spiritual perspective has persisted despite the introduction of Christianity and Islam (Jegatheesan et al., Citation2010). Consequently, families of individuals with IDD may feel compelled to explain their situation in spiritual terms, reinforcing the stigma associated with these conditions and the lack of requisite support and services for better welfare. These cultural and spiritual beliefs contribute to discrimination, stigmatization and social isolation of individuals with disabilities and their families, further exacerbating the challenges they face (Aldersey et al., Citation2017). Families may be subjected to abandonment and societal exclusion due to these unfavorable views about disability, with some people with IDD being abandoned (Kassah et al., Citation2012).

This deep-rooted cultural and spiritual perspective on IDD underscores the significant knowledge gap in understanding intellectual disabilities on the continent. The limited awareness and misconceptions stemming from these beliefs can deter families from seeking assistance and support services, compounding the challenges faced by individuals with IDD and their caregivers. Despite these obstacles, governmental and voluntary organizations continue their efforts to serve Ghana’s disabled population (Avoke, Citation2002). Policymakers and practitioners need to prioritize awareness and education campaigns that challenge these misconceptions and promote a more accurate understanding of IDD. Additionally, efforts should be directed toward developing culturally sensitive and inclusive support services that consider the local beliefs and practices while providing essential care and interventions for individuals with IDD and their families. Addressing the stigma and discrimination associated with IDD through policy initiatives can lead to more equitable access to services, improved social inclusion and enhanced overall well-being for this population.

4.4. Employment as a support service

The results highlight the paramount importance of employment for fostering independence and social inclusion among individuals with intellectual disabilities in Africa. Employment not only provides them with a sense of purpose and financial autonomy but also empowers them to make choices and contribute to society, enhancing self-esteem and overall well-being. However, significant barriers, including limited employment opportunities, education gaps, societal prejudices and social isolation, pose formidable challenges to realizing this goal, emphasizing the urgent need for comprehensive support systems and inclusive policies. They grapple with various employment-related risk factors daily, such as recurrent job failures, limited support in securing and maintaining employment and challenges in building and sustaining professional relationships within the workplace. These difficulties in finding and holding down jobs often lead to feelings of powerlessness and emotional distress (Trzaska, Citation2012).

Several studies, including those conducted by Dempsey and Ford (Citation2009), Hall (Citation2010), Jahoda et al. (Citation2009) and Moore et al. (Citation2018), collectively provide a wealth of evidence highlighting the constrained employment opportunities for individuals with intellectual disabilities. This underscores the potential ramifications for their long-term well-being, particularly concerning their independence and financial security, particularly among those who are poor (Almalky, Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2018); illuminating the persistent challenges faced by individuals with intellectual disabilities in accessing meaningful employment, which can significantly impact their overall quality of life and prospects for financial stability. These challenges not only affect their financial independence but also impact their overall quality of life, including their sense of purpose, social interaction and self-esteem.

Addressing the limited employment prospects of individuals with intellectual disabilities holds profound implications for their long-term well-being, particularly concerning their independence and financial stability, especially for those facing economic challenges. To address this critical issue, proactive measures are needed, including tailored education and training programs, employer engagement initiatives, supportive policies, community networks, advocacy efforts, financial assistance and ongoing evaluation. People with intellectual disabilities often face mistreatment, limited social participation and a lack of representation in social and political roles (Hervie, Citation2013; Sackey, Citation2015). Individuals with intellectual disabilities frequently encounter significant obstacles in their social participation, leading to their disenfranchisement within society (Aldersey, Citation2012; Hervie, Citation2013; Sackey, Citation2015).

These barriers manifest as mistreatment, exclusion from various social activities and a dearth of representation in both social and political spheres (Hervie, Citation2013; Sackey, Citation2015). The marginalization of this population further isolates them from mainstream society, preventing them from enjoying the full benefits of social inclusion and civic engagement. Additionally, studies have highlighted how unfavorable societal attitudes, discrimination and limited accessibility to community resources contribute to the profound disenfranchisement experienced by individuals with intellectual disabilities (Aldersey, Citation2012). These challenges necessitate comprehensive efforts to promote inclusivity, dismantle societal prejudices and create opportunities for meaningful social and political participation, thus fostering a more equitable and just society for all.

5. Strengths and weaknesses

The review offers a comprehensive examination of LTSS for older adults with IDD in Africa. It covers various aspects, including service types, accessibility, affordability and their impact on families and caregivers, providing a holistic view. It adopts a multidisciplinary approach, drawing from diverse academic studies and reports, enriching the analysis. The review’s critical assessment identifies challenges like limited IDD understanding, lack of psychological support and accessibility issues, adding depth. It concludes with a compelling call for immediate action to improve the lives of older adults with IDD in Africa, urging policymakers, researchers and stakeholders to address these challenges urgently.

One major limitation of this study is the restricted number of included papers, preventing the possibility of conducting a meta synthesis. This limitation stems from the overall scarcity of research on long-term services for older adults with IDD in the region. The predominant focus of existing studies on children and caregivers of children and their families has left the domain of aging, intellectual disability and services relatively unexplored. Social gerontologists and researchers in related disciplines should take a keen interest in this area to actively generate knowledge that can guide policy and enhance the well-being of older adults with IDD.

6. Conclusion

This systematic review aimed to uncover the challenges faced by older adults with IDD in Africa regarding LTSS. The review revealed several significant challenges. First, there’s a lack of understanding and knowledge about IDD in Africa, leading to stigma and limited access to services. This lack of understanding stems from our inherent association with culture and belief system. This can be seen in our adoption of special school system and the segregation faced by IDD. This stigmatizing agenda has strip off individuals from studying about disability related courses and the lack of professional psychological support exacerbates the challenges faced by individuals and families dealing with intellectual disabilities. It also emphases why there is not appropriate support services from the government for this population. The lack of clear and comprehensive governmental frameworks for addressing the mental health and well-being of individuals with intellectual disabilities leaves a regulatory vacuum. IDD adults situated at rural areas are the most disadvantage in relation to service types, accessibility, affordability and the impact on families and caregivers. They are only noticed during governmental election years and used as campaign propagandas. Many people struggle to access healthcare, especially in rural areas. There’s also a gap in specialized services for adults with severe IDD. Employment and education opportunities are scarce, contributing to financial insecurity. Discrimination is a prevalent issue, further marginalizing this group. To address these challenges, awareness campaigns should be conducted to reduce stigma and government policies should prioritize IDD support. Expansion of healthcare services, especially in rural areas, is necessary. Specialized services for severe IDD need development. The creation of education and employment opportunities is essential, and the promotion of efforts to foster inclusive communities is important. Immediate action is imperative to enhance the quality of life for older adults with IDD in Africa, guaranteeing them dignified and fulfilling lives. The collaboration between not-for-profit organizations specializing in disability issues and the relevant ministry is paramount for realizing the overarching theme of the UNSDG goals, ie leaving no one behind. It is imperative that the needs of vulnerable groups in our society, particularly those with disabilities, are prioritized. By working together, these organizations and the concerned ministry can make significant strides toward achieving these goals. The ultimate aim is to build a more inclusive society that is mindful of the needs of all, and ensures that no one is left behind.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Akwasi Adjei Gyimah

Akwasi Adjei Gyimah is a scholar-practitioner who believes in the intersectionality between aging and disability, Adjei Gyimah has field and academic experiences in advocating for the differently abled and older people in Africa. His research interests include dis-ability studies, sexual reproductive health, social policy, aging, sustainable development, and inclusive education.

Katherine M. Abbott

Katherine M. Abbott is the Executive Director of the Scripps Gerontology Center and a Professor of Gerontology in the Department of Sociology and Gerontology at Miami University. Her research focuses on the preference-based, person-centered care of older adults receiving long-term services and support. She is the co-founder of Preference Based Living, whose mission is to conduct and translate scholarly research into practice to honor the needs and preferences of individuals receiving care in varied settings worldwide.

Eric Frimpong

Eric Frimpong is a researcher at the Gerontology Department, University of Massachusetts, Boston. His research interest encompasses issues relating to Health of Older Adults with Disabilities and Care-giving of older adults with disabilities.

Mathias Adjei

Mathias Adjei is a Public Health researcher at the Miami University whose research interest includes public health, aging and entrepreneurship.

References

- Aldersey, H. M. (2012). Family perceptions of intellectual disability: Understanding and support in Dar es Salaam. African Journal of Disability, 1(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v1i1.32

- Aldersey, H. M., Francis, G. L., Haines, S. J., & Chiu, C. Y. (2017). Family quality of life in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 14(1), 78–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12189

- Alftberg, Å., Johansson, M., & Ahlström, G. (2021). Ambivalence among staff regarding aging with intellectual disabilities: Experiences and reflections. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: JOID, 25(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629519874997

- Almalky, H. A. (2020). Employment outcomes for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104656

- Alonso-Sardón, M., Iglesias-de-Sena, H., Fernández-Martín, L. C., & Mirón-Canelo, J. A. (2019). Do health and social support and personal autonomy have an influence on the health-related quality of life of individuals with intellectual disability? BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3856-5

- Amado, A. N., Stancliffe, R. J., McCarron, M., & McCallion, P. (2013). Social inclusion and community participation of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(5), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.5.360

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Anderson, S., Parmar, J., Dobbs, B., & Tian, P. G. J. (2021). A tale of two solitudes: Loneliness and anxiety of family caregivers caring in community homes and congregate care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910010

- Avoke, M. (2002). Models of disability in the labelling and attitudinal discourse in Ghana. Disability & Society, 17(7), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759022000039064

- Bennett, J., Lubben, F., Hogarth, S., & Campbell, B. (2005). Systematic reviews of research in science education: Rigour or rigidity? International Journal of Science Education, 27(4), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069042000323719

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., Mazefsky, C. A., Minshew, N. J., & Eack, S. M. (2015). The relationship between stress and social functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder and without intellectual disability. Autism Research, 8(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1433

- Bornstein, M. H., & Hendricks, C. (2013). Screening for developmental disabilities in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 97, 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.049

- Braddock, D., & Heller, T. (1985). The closure of mental retardation institutions I: Trends in the United States. Mental Retardation, 23(4), 168–176.

- Buntinx, W. H., & Schalock, R. L. (2010). Models of disability, quality of life, and individualized supports: Implications for professional practice in intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(4), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00278.x

- Burrell, B., & Trip, H. (2011). Reform and community care: Has de-institutionalisation delivered for people with intellectual disability? Nursing Inquiry, 18(2), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00522.x

- Capri, C., & Swartz, L. (2018). ‘We are actually, after all, just children’: Caring societies and South African infantilisation of adults with intellectual disability. Disability & Society, 33(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1409102

- Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2009). Breaking out of a distinct social space: Reflections on supporting community participation for people with severe and profound intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(3), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00458.x

- Cobigo, V., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Lysaght, R., & Martin, L. (2012). Shifting our conceptualization of social inclusion. Stigma Research and Action, 2(2), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.5463/sra.v1i3.45

- Dempsey, I., & Ford, J. (2009). Employment for people with intellectual disability in Australia and the United Kingdom. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 19(4), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207308314946

- Duggan, C., & Linehan, C. (2013). The role of ‘natural supports’ in promoting independent living for people with disabilities; a review of existing literature. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12040

- Eady, N., Courtenay, K., & Strydom, A. (2015). Pharmacological management of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in older adults with intellectual disability. Drugs & Aging, 32(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0236-7

- Emerson, E., Fortune, N., Llewellyn, G., & Stancliffe, R. (2021). Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 100965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100965

- Evenhuis, H. M., Hermans, H., Hilgenkamp, T. I., Bastiaanse, L. P., & Echteld, M. A. (2012). Frailty and disability in older adults with intellectual disabilities: Results from the healthy aging and intellectual disability study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(5), 934–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03925.x

- Friedman, C. (2019). Family members of people with disabilities’ explicit and implicit disability attitudes. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000265

- Glasson, E., & Bittles, A. H. (2008). The impact of ageing in people with intellectual and developmental disability. In E.B. Bodzsar (Ed.), Ageing related problems in past and present populations (pp. 27–43). Plantin Publications & Press Ltd.

- Grey, J. M., Totsika, V., & Hastings, R. P. (2018). Physical and psychological health of family carers co-residing with an adult relative with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 31(S2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12353

- Hahn, J. E., Fox, S., & Janicki, M. P. (2015). Aging among older adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Setting national goals to address transitions in health, retirement, and late-life. Inclusion, 3(4), 250–259.

- Hall, E. (2010). Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 54(s1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01237.x

- Harpazi, S., Regev, D., & Snir, S. (2022). What does the literature teach us about research, theory, and the practice of art therapy for individuals with intellectual developmental disabilities? A scoping review. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 82, 101988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2022.101988

- Haveman, M., Heller, T., Lee, L., Maaskant, M., Shooshtari, S., & Strydom, A. (2010). Major health risks in aging persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview of recent studies. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00248.x

- Hervie, V. M. (2013). [Shut up!: Social inclusion of children with intellectual disabilities in Ghana: An empirical study of how parents and teachers experience socialinclusion [ie social inclusion] of children with intellectual disabilities] [Master’s thesis]. UniversitetetNordland.

- Jahoda, A., Banks, P., Dagnan, D., Kemp, J., Kerr, W., & Williams, V. (2009). Starting a new job: The social and emotional experience of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(5), 421–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00497.x

- Janicki, M. P., & Keller, S. M. (2014). Viability of a dementia advocacy effort for adults with intellectual disability: Using a national task group approach. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(3), 176–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12085

- Jegatheesan, B., Fowler, S., & Miller, P. J. (2010). From symptom recognition to services: How South Asian Muslim immigrant families navigate autism. Disability & Society, 25(7), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2010.520894

- Karam, S. M., Riegel, M., Segal, S. L., Félix, T. M., Barros, A. J. D., Santos, I. S., Matijasevich, A., Giugliani, R., & Black, M. (2015). Genetic causes of intellectual disability in a birth cohort: A population-based study. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A, 167(6), 1204–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37011

- Kassah, A. K., Kassah, B. L. L., & Agbota, T. K. (2012). Abuse of disabled children in Ghana. Disability & Society, 27(5), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.673079

- Kelly, C., Thornton, A., Anthony, E. K., & Krysik, J. (2021). —Love. Stability. Boundaries.” Kinship perspectives of social-emotional well-being of youth residing in out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 127, 106097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106097

- Kisanji, J. (1998). Culture and disability: An analysis of inclusive education based on African folklore. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 1–18.

- Knapp, M., Comas-Herrera, A., Astin, J., Beecham, J., & Pendaries, C. (2005). Intellectual disability, challenging behaviour and cost in care accommodation: What are the links? Health & Social Care in the Community, 13(4), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00539.x

- Krahn, G. L., Walker, D. K., & Correa-De-Araujo, R. (2015). Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health, 105(Suppl 2), S198–S206. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182

- Larson, S. A., Lakin, K. C., Salmi, P., Smith, D., Scott, N., & Webster, A. (2011). Children and youth with intellectual or developmental disabilities living in congregate care settings (1977 to 2009): Healthy people 2010 objective 6.7 b outcomes (revised). Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.3.209

- Lawson, A., & Beckett, A. E. (2021). The social and human rights models of disability: Towards a complementarity thesis. The International Journal of Human Rights, 25(2), 348–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1783533

- Lunsky, Y., De Oliveira, C., Wilton, A., & Wodchis, W. (2019). High health care costs among adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A population-based study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 63(2), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12554

- Marks, B., Sisirak, J., Chang, Y. C., & Murphy, R. (2019). Impact of the HealthMatters Train-the-Trainer Program on the health and health behaviors of staff supporting adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Workplace Health & Safety, 67(8), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079919828739

- Marks, B., Sisirak, J., & Heller, T. (2010). Health matters: The exercise and nutrition health education curriculum for people with developmental disabilities. Brookes Publishing Company.

- Martin, L., & Cobigo, V. (2011). Definitions matter in understanding social inclusion. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(4), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00316.x

- Matheis, M. (2019). Philosophy of care. In Johnny L Matson (Ed.), Handbook of intellectual disabilities: Integrating theory, research, and practice (pp. 75–89).

- McCausland, D., McCallion, P., Cleary, E., & McCarron, M. (2016). Social connections for older people with intellectual disability in Ireland: Results from wave one of IDS-TILDA. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 29(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12159

- Mckenzie, J. A., McConkey, R., & Adnams, C. (2013). Intellectual disability in Africa: Implications for research and service development. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(20), 1750–1755. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.751461

- McNally, A., & Mannan, H. (2013). Perceptions of caring for children with disabilities: Experiences from Moshi, Tanzania. African Journal of Disability, 2(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v2i1.21

- Meer, T., & Combrinck, H. (2015). Invisible intersections: Understanding the complex stigmatisation of women with intellectual disabilities in their vulnerability to gender-based violence. Agenda, 29(2), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1039307

- Meer, T., & Combrinck, H. (2017). Help, harm or hinder? Non-governmental service providers’ perspectives on families and gender-based violence against women with intellectual disabilities in South Africa. Disability & Society, 32(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1269639

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., Atkins, D., Barbour, V., Barrowman, N., Berlin, J. A., & Clark, J. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine, 7(9), 889–896. https://doi.org/10.3736/jcim20090918

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Moher, D., Stewart, L., & Shekelle, P. (2016). Implementing PRISMA-P: Recommendations for prospective authors. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0191-y

- Moore, K., McDonald, P., & Bartlett, J. (2018). Emerging trends affecting future employment opportunities for people with intellectual disability: The case of a large retail organisation. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(3), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1379250

- Mung’omba, J. (2008). Comparative policy brief: Status of intellectual disabilities in the Republic of Zambia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(2), 142–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2008.00163.x

- Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Tufanaru, C., Stern, C., Porritt, K., Farrow, J., Lockwood, C., Stephenson, M., Moola, S., Lizarondo, L., McArthur, A., Peters, M., Pearson, A., & Jordan, Z. (2019). The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). JBI International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 17(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000152

- Naami, A., Parry, R. A., & Ofori, A. (2022). Perspective chapter: Disability-inclusive sustainable services–The role of social workers. In Wolmesjö, Maria (Ed.), Social work-perspectives on leadership and organisation (Vol. 185, pp. 1349–1356). IntechOpen. http://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96846

- Overmars-Marx, T., Thomése, F., Verdonschot, M., & Meininger, H. (2014). Advancing social inclusion in the neighbourhood for people with an intellectual disability: An exploration of the literature. Disability & Society, 29(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.800469

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M. J. D., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., … UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

- Power, A. (2008). Caring for independent lives: Geographies of caring for young adults with intellectual disabilities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 67(5), 834–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.023

- Roberts, M., Mogan, C., & Asare, J. B. (2014). An overview of Ghana’s mental health system: Results from an assessment using the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-16

- Robertson, J., Hatton, C., Emerson, E., & Baines, S. (2014). The impact of health checks for people with intellectual disabilities: An updated systematic review of evidence. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(10), 2450–2462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.007

- Rohleder, P., & Swartz, L. (2009). Providing sex education to persons with learning disabilities in the era of HIV/AIDS: Tensions between discourses of human rights and restriction. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(4), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309103579

- Roll, A. E., & Koehly, L. M. (2020). One social network, two perspectives: Social networks of people with Down syndrome based on self-reports and proxy reports. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 33(6), 1188–1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12736

- Sackey, E. (2015). Disability and political participation in Ghana: An alternative perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 17(4), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2014.941925

- Salvador-Carulla, L., García-Gutiérrez, J. C., Gutiérrez-Colosía, M. R., Artigas-Pallarès, J., Ibánez, J. G., Pérez, J. G., Pla, M. N., Inés, F. A., Isus, S., Cereza, J. M., Poole, M., Lazcano, G. P., Monzon, P., Leiva, M., Parellada, M., Nonell, K. G., Martínez i Hernández, A., Rigau, E., & Martínez-Leal, R. (2013). Borderline intellectual functioning: Consensus guide and good practices. Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(3), 109–120.

- Shooshtari, S., Naghipur, S., & Zhang, J. (2012). Unmet healthcare and social services needs of older Canadian adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2012.00346.x

- Šiška, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2023). Progress on deinstitutionalisation and the development of community living for persons with disabilities in Europe: Are we nearly there? Disability & Society, 38(8), 1476–1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2022.2071676

- Smith, D., Lakin, K. C., Larson, S., & Salmi, P. (2011). Changes in residential arrangements of persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the decade following the Olmstead decision of 1999. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(1), 53–54. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.1.53

- Stenfert Kroese, B., Willott, S., Taylor, F., Smith, P., Graham, R., Rutter, T., Stott, A., & Willner, P. (2016). Trauma-focussed cognitive-behaviour therapy for people with mild intellectual disabilities: Outcomes of a pilot study. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 10(5), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-05-2016-0008

- Stirling, M., Anderson, A., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Hallet, J., Shooshtari, S., Kelly, C., Dawe, D. E., Kristjanson, M., Decker, K., & Mahar, A. L. (2021). A scoping review documenting cancer outcomes and inequities for adults living with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 54, 102011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102011

- Terreblanche, S. E. (2015). [A transformation strategy for protective workshops: Towards comprehensive services for adults with intellectual disability] [Doctoral dissertation]. Stellenbosch University.

- Trzaska, J. D. (2012). The use of a group mural project to increase self-esteem in high-functioning, cognitively disabled adults. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(5), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.06.003

- van Asselt-Goverts, A. E., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C., Wegman, K. M., & Teunisse, J. P. (2015). Do social networks differ? Comparison of the social networks of people with intellectual disabilities, people with autism spectrum disorders and other people living in the community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(5), 1191–1203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2279-3

- Van Niekerk, L., Coetzee, Z., Engelbrecht, M., Hajwani, Z., & Terreblanche, S. (2015). Time utilisation trends of supported employment services by persons with mental disability in South Africa. Work, 52(4), 825–833. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152149

- Wanjagua, R. W. (2018). Identifying support needs for people with intellectual disability and their families through a family quality of life survey in Kenya.