ABSTRACT

Exploring the challenges faced by both female and male individuals amid the social upheaval of the Sixties, British writer Penelope Gilliatt presents in the Sunday Bloody Sunday screenplay a counterimage to the romanticized mainstream portrayal of social change that is guided by the market for commercial benefits. The association of the social change of the Sixties and Seventies with romanticized words and images in popular culture, including feature films, documentaries, and advertisements, made the process of social change seem dreamy and flawless. Therefore, revisiting Sunday Bloody Sunday as a counter-mainstream image of the Sixties is a revisit of the social change. The film ruptures the positive meanings of “love” associated with sexual liberation and introduces a subverted set of meanings. Through a semiotic analysis of Sunday Bloody Sunday and an analysis of the context in which it was written and directed, this study uncovers some of the challenges stemming from the concept of free/open relationships, which is one of the outcomes of the sexual revolution. The focus of this study is on Alex and Bob’s heterosexual relationship. The sign “love” in Sunday Bloody Sunday carries negative connotations that represent it as problematic, lacking, and agonizing through a series of signifiers discussed in the study. Sunday Bloody Sunday thus subverts meanings of liberation, emancipation, and sexual fulfillment that used to be associated with the sign “love” during the sexual revolution of the Sixties.

Introduction

A passionate kiss between the homosexual doctor Daniel Hirsh (Peter Finch) and the bisexual artist Bob Elkin (Murray Head) made the British film Sunday Bloody Sunday a “queer pioneer,” as some film critics described it.Footnote1 Produced in 1971, the film is set amid a period of social change marked by the rise of the sexual revolution that came to define sexual relationships in the Western world as we now know it. Sunday Bloody Sunday, written by novelist and critic Penelope Gilliatt and directed by acclaimed filmmaker John Schlesinger, tells the story of a mid-thirties divorcée, Alex Greville (Glenda Jackson), who enters an open relationship with Bob, an artist in his mid-twenties, while knowing that he’s also in an intimate relationship with Daniel, a middle-aged doctor. Despite the film’s popularity, which could be attributed to several factors, including the passionate kiss between Daniel and Bob, little attention is given to the role of this cinematic work in subverting the meaning of the sign “love.”

The sign “love” during the social change of the Sixties and Seventies was associated with meanings related to widespread calls for peace, freedom, and emancipation. For instance, “love” was used in the slogan “Make Love Not War” during the protests against the Vietnam War. With the advent of the sexual revolution, “love” became associated with the meanings of pleasure and sexual fulfillment. Films portrayed the Sixties as a psychedelic, dreamlike time when women celebrated empowerment through sexual fulfillment.Footnote2 Sunday Bloody Sunday presents a subversion of such positive connotations of “love” to counter mainstreamed representations. In attempting to decode the challenges of social change, the film ruptures the colorful, romanticized market myths of “love” in swinging London.

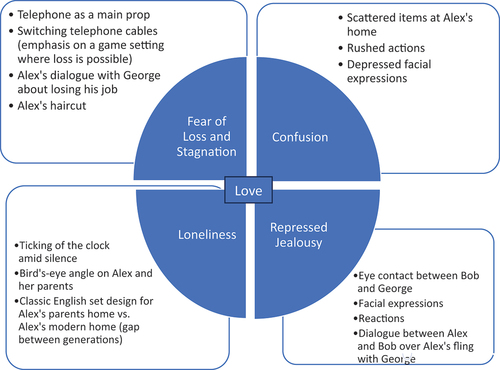

Focusing on the heterosexual relationship between Alex and her boyfriend Bob, this study highlights Alex’s situation as a woman caught between the failed ideal of her parents’ traditional marriage and the free/open relationship she has with the polyamorous hippie artist Bob at the advent of the sexual liberation movement. Showcasing how Sunday Bloody Sunday attributes negative connotations to the sign “love,” I will read the film textually – determining the signifiers (facial expressions, props, sounds, and dialogue) that lead to a series of signifieds (emotions) which contribute to a subversion of meanings associated with the sign “love.”Footnote3

However, before analyzing the film textually, it is necessary to set the film in its historical context, discuss the salient romanticized representations of “love” that the film subverts (contextual analysis), and then introduce a semiotic analysis of it. Analyzing the film contextually acknowledges what Barber suggests in explaining the use of film as a reference for a particular time in history: “Films never emerge in a vacuum; a range of competing factors will have informed their production at a particular historical moment.”Footnote4

Film analysis and film as a source

Analyzing film has always been a debatable matter that became even more debatable after the publication of Christian Metz’s Language and Cinema in 1974. The relative novelty and importance of Metz’s approach, widely known as “textual analysis,” stems from its breaking with the old tradition of film analysis that dedicated thorough examination to the plot and character rather than the filmic signifiers and the formal cinematic elements.Footnote5 However, Metz’s textual analysis was criticized for dissecting a film into very small parts to analyze it textually. It is said to have mummified each shot to declare how it works in terms of shot sequence, montage, and other signifiers, neglecting the message or the subject matter of the film.Footnote6

Metz responded to the criticism of his method by arguing that such criticism is a consequence of misunderstanding terms like “form” (the signifier) and “content” (the signified) or “form” and “substance” as oppositions.Footnote7 Metz clarifies that those who deal with the signifier (words spoken, images, sounds, the organization of images, facial expressions, characters’ clothing) and the signified (the social content of the film, the psychology of the character, the ideological message of the film, etc.) as two separate things ignore the fact that the signifying elements have both a form and a substance. Any study of the form is in fact the study of the film as a whole (content and form), because any structural analysis aimed at the structure of the sounds and images (signifier) signifies ideas and emotions (signified).

The form and content of films have usually been studied in separate yet intertwining fields such as the field of cultural studies and the field of semiotics. Although some have tried to draw boundaries between the cultural specificity of a film as an approach for study, and codes and filmic language as another approach, cultural studies end up using textual analysis (or, preferably, “textual reading”).

Sian Barber clarifies that cultural studies usually refrain from getting too invested in rigid semiotic analysis.Footnote8 In her Using Film as a Source, she explains that, to use a film as a source in research or reference to a particular time in history, it has to be rooted in a cultural analysis and historical practice. Similarly, in his 1947 article “Tout film est un documentaire social,” André Bazin asserts that every film is an “irreplaceable social documentary.”Footnote9 As Bazin suggests, the film is a social documentation in the sense that, in one way or another, it is a reflection of the social psyche or a manifestation of a “social psychoanalysis,” as he calls it.Footnote10 The film in such a manner becomes a recognition of the public’s illusions, dreams, and worst thoughts, and thus a key to understanding the public or, in other words, society at its core.

Some screenwriters and directors adapt their work to the expectations, illusions, and social norms of their audience; others try to rupture them in favor of assigning a new meaning to signs.Footnote11 As this study discusses, Sunday Bloody Sunday subverts the sign “love,” commonly associated with meanings of liberation, peace, and freedom during the Sixties, and presents an unsettling set of negative meanings like loneliness, confusion, fear, and repressed jealousy.

The kind of textual analysis used here is not as rigid as what Kuntzel tries to do when he analyzes The Most Dangerous Game, ending up writing more than 60 pages on some minute details of the film.Footnote12 On the contrary, textual analysis in this study is informed by context and set to determine a series of signifiers (facial expressions, props, set design, tone of voice, dialogue) that lead to a series of signifieds (emotions) affecting the overall creation of the meanings of “love” in the film. By paying specific attention to the context, including the social development that was taking place during the authorship of Sunday Bloody Sunday and the popular culture which the film subverts, this study suggests that film can be used to illuminate agonies associated with social changes at a particular time in history.

Putting Sunday Bloody Sunday in context

The Sunday Bloody Sunday screenplay was written in the late Sixties amid an era of radical social change in Britain. Gilliatt’s sensitivity to the women’s liberation movement and the agonies associated with love, marriage, and relationships at the time allowed her to provide vivid verbal and physical expressions of those struggles.

As Gilliatt began writing the screenplay, the British feminist movement, or what was known originally as the women’s liberation movement, was witnessing its second wave.Footnote13 The second wave feminist movement was shaped around the body, sexuality, and relationships.Footnote14 Gaining control over the body meant not only freedom from the way women were judged, monitored, and exerted authority over, but also freeing the female body from its biological burden, in particular the burden of pregnancy. A medical breakthrough highly compatible with the idea of freeing the body was the introduction of contraceptive pills. By the end of 1969, many women who were taking the pill enjoyed more sexual freedom without worrying. Before the pill, it was conventionally understood that only men could get away with having consequence-free premarital sexual intercourse, while women might well find themselves forced to give birth to an unwanted child.Footnote15 As Brown notes in her remarks on the film, the development of the pill and the social change that followed resonate with Alex’s sense of freedom in Sunday Bloody Sunday; however, this essay suggests that such freedom neither eliminated nor compensated for Alex’s need for companionship and security.

Western feminists have put the notion of sexual liberation forward as a priority for the women’s liberation movement agenda as a means of emancipating the female body. In 1982, journalist and feminist activist Ellen Willis wrote:

[T]he first step, I believe, is simply to affirm the validity, in principle, of sexual liberation as a feminist goal … that it is important for feminists to defend people’s freedom to engage in consensual sexual activity, including acts we might find distasteful.Footnote16

Willis saw that sex was an enjoyable function with no intrinsic moral connotations, and thus that diminishing social condemnation of female unchastity should ease both female and male lives and reconcile society to casual sex. She also perceived that repressing sexual desire and parents’ dealing with sex as a taboo in talking with children as sources of aggression between the sexes; she argued, therefore, that parents should refrain from associating sex with guilt and, rather, normalize sex and the acknowledgment of sexual desire.Footnote17 At the time Sunday Bloody Sunday was produced, the idea of normalizing sex and being at ease with naked bodies as part of the upbringing of children was just starting to be put into general practice. In a scene where Alex and Bob lie in bed together at the home of their friends the Hodsons, the Hodsons’ children rush into the room, asking Alex and Bob to wake up. The oldest child mentions that they usually go to their parents’ room first thing in the morning and then “watch mummy and papa have a bath together.” Alex and Bob look confused at what they’ve just heard. Sunday Bloody Sunday is a film born amid those ideas and a worldwide civil rights movement, representing on a micro-level the lives of people during that period of change.

The embracing of sexuality and experimentation with same-sex relations, which mark the Sixties ethos, is represented through Bob, who is fully immersed in the sexual liberation movement and eager to discover his sexuality. Younger than Alex, Bob is always ready to explore new possibilities and chooses to explore his sexuality by sleeping with both men and women. Director John Schlesinger, gay himself, introduces a sensational kiss between the two men (Bob and his boyfriend Daniel) on screen. This kiss was the focus of numerous articles and studies depicting it as a triumph for homosexuality and the sexual freedom era, with little or no attention paid to the heterosexual relation between Alex and Bob, let alone the agonies prompted by the new mode of open relationships through looking at the negative connotation of the sign “love” in this film.

The Sixties also mark the rise of the neoliberal economy, as a result of the failure of the welfare state.Footnote18 Aesthetic production became fused with commodity production, which Jameson describes as “the frantic economic urgency of producing fresh waves of ever more novel-seeming goods (from clothing to airplanes).”Footnote19 The Sixties were a remarkable age of corporate enterprise characterized by heightened interpersonal competition, reflected in British films like Room at the Top.Footnote20 Entrepreneurialism, evident in the establishment of new projects such as theaters, experimental arts venues, art galleries, and even ventures involving pornographic material, not only encouraged competition but also cultivated a culture of individualism and effectively linked creative arts with production.Footnote21 Bob in Sunday Bloody Sunday is introduced as a symbol of such commercialization of creative arts. Through his wide interest in visiting the US, symbol of consumerism and modern art at the time, he communicates a belief that the future of art is bound by capitalism. It is another subversion that the hippie-like Bob is introduced as a symbol of capitalism, with its loaded meanings of individualism, competition, and commercialism.

Radical social change is not comforting; it is usually marked with heightened distrust in all institutions, including the family institution in which one is supposed to find solace.Footnote22 During the mid-Sixties, the family institution was declining as a result of the increasing divorce rate in England and Wales, which spiked during the mid-Eighties.Footnote23 Sunday Bloody Sunday is thus not only a bold and authentic cinematic work that introduces us to the lives of people who lived amid the social change of the late Sixties and early Seventies but also a confrontational work that subjects the audience to a feeling of unease transmitted by the frustration of the characters with their romantic relationships.

Subverting the myth of the happy, empowering sixties

During the Sixties, mass media, including magazines, newspapers, TV, and radio, portrayed swinging London as vibrant, cool, colorful, free, original, and bold. This section pinpoints two salient signifiers of the Sixties in mass media. The first is the psychedelic dreamlike images and the second is the figure of the “sexually liberated woman” that appeared in films of the period.

A psychedelic, dreamlike world: drugs, discotheques, and outstanding costumes

As Christopher Booker notes, Sixties Britain was usually represented in a “highly romanticized” manner. To create a colorful myth of happy London, Booker explains that representations of icons such as the Beatles, Carnaby Street, and Twiggy appeared everywhere in magazines, billboards, radio programs, films, and TV shows. Footnote24 Specific words, which Booker calls “hip phraseology,” were, and still are, used to describe the Sixties period such as “cool,” “groovy,” and “swinging,” reflecting new values and attitudes.Footnote25 Film directors contributed to portraying cool and swinging London onscreen through the use of “aesthetics of psychedelia.” Aesthetics of psychedelia included colorful, psychedelic, dreamlike set design, hippie costumes, and discotheques as spaces for mass hysteria.Footnote26

The use of psychedelic drugs in particular was portrayed in films as pervasive and normal. Patrick Glen recovered recordings of interviews and questionnaires with people who were asked to discuss the memory of their lives compared to popular films of the Sixties.Footnote27 Some of them described the emphasis on psychedelic experiences as “alienating,” as it made them feel like outsiders, strangers to that celebrated world. One pointed out that, for many working-class youth, daily employment commitments took precedence over trying substances such as the consciousness-altering LSD known for its “tripping” effects, highlighting a stark contrast between cinematic portrayals and the realities of everyday life. One participant said, “My life was much less sexy, daring, adventurous, dangerous, changing. The films made me expect more of life.”Footnote28

Robert Murphy recounts a similar alienating experience during the Summer of Love in 1967. At the time, Murphy was working as a filleter’s laborer in a fish factory in Grimsby.Footnote29 He recalls that his grim, hard life didn’t have anything resembling the colorful images of swinging London he used to see in magazines, posters, and films. However, as he looked back at the Sixties films in the 1990s while writing his book, he concluded that it would be unfair to say that all British movies of that period were mindlessly optimistic about the changes that were going on. On the contrary, Murphy thinks that many of the films produced during that period were some of the best to discuss social anxieties and social problems.

Similar to what Murphy thinks about the existence of some of the best British films critical or at least skeptical of social change, Sunday Bloody Sunday is a work of art that did not mindlessly adopt the mainstreamed romanticized images of the Sixties and Seventies. By comparing the film to Schlesinger’s earlier Darling, the salience of the mainstream signifiers of “love” in the later becomes clear. “love” in Darling was represented in a mood of mass hysteria and breaking of social taboos concerning sex and sexuality. Although Darling can be seen as critical of some of the consequences of the social change of the Sixties, it still depended on the aesthetics of psychedelia and mass hysteria, with a focus on youth and pop culture. Pamela Church Gibson shows how Darling contributed to the Sixties mythology through the fashion trend it created.Footnote30 Gibson attributes the popularity of certain attire like miniskirts and flat boots among young girls to Darling. On the contrary, Sunday Bloody Sunday refrained from the emphasis on psychedelia, drug use, and eye-catching female costumes, and worked on interweaving young and old characters’ stories so that the intersections and diversions between past and present become vivid to the audience.

Although films like Sunday Bloody Sunday subvert the colorful myth of the Sixties, latter-day films still adopt the myth of the happy Sixties, including documentaries. In 2017, I watched a BBC-produced documentary titled Summer of Love, 1967 (Fitzgerald Citation2006). Through interviews with artists and fashion designers who regarded the Sixties as the best time of their lives, the documentary framed that period as a utopia of creative fashion, music, and art, with young people calling for the end of various forms of oppression to achieve complete liberation, almost akin to anarchy. When you hear the Beatles singing “All You Need Is Love” in the background of the documentary, it is easy to assume that the process of social change was dreamy, bold, and flawless.

Sexually liberated women: free, empowered, and erotic

Whenever sexual liberation is mentioned, the female body comes to mind. Baudrillard notes that the myth of emancipation associates sexual liberation with the female body, which becomes in the capitalist world an object to be marketed and consumed.Footnote31 The way sexual liberation emerged as a result of the Sixties’ social dynamics, power structures, and economic context thus further objectified women’s bodies. Objectification occurred as female bodies were represented as elements of spectacle and eroticism in mass media.

In films, the female body contributed to the myth of the Sixties through costumes, colors, the rise of certain female figures (e.g. Twiggy, Julie Christie), and nudity linked to eroticism. This is evident in films like Blow Up, where women appear as dolls, or as Thomas, the photographer protagonist calls them, “birds.” The women, mainly models in the film (another myth of the Sixties – “women as models”), did as the male photographer told them to do. Women in Blow Up dressed and undressed as the photographer ordered; two young ladies even committed themselves to please him all day by engaging in wild sex play to get jobs as models. Throughout the film, the female body is presented as an element of spectacle and permissiveness. Permissiveness is seen by Marwick as one of the characteristics associated with the sexual liberation movement that contributed to the myth of the Sixties.Footnote32

Bell explains that the way a sexually liberated woman was represented in films of the era satisfies the male gaze and men’s fantasies, contributing to the mythology of the Sixties.Footnote33 She states, “The sexually liberated young woman was central to the myth of ‘Swinging Britain,’ but she was frequently reduced to nothing more than a sex object.”Footnote34 Bell suggests that the imagined lives of the sexually liberated women in films, who seemed free and empowered by embracing sexual liberation, greatly differed from the reality of women who lived at the time.

In many films, we encounter the male gaze when the camera shows men looking at women marveling at their bodies in desire. On the contrary, in Sunday Bloody Sunday, the female gaze is introduced as yet another subversion of the mainstream. In a scene where Bob takes a shower, Alex marvels at the shadow of Bob’s body from behind the curtain; indeed, we see her eyes desiring him throughout the film. What adds more to the subversion of the mainstream is Bob’s male body, which was marveled at and desired by both female Alex and male Daniel. Another important element is that Sunday Bloody Sunday does not show Alex as a woman empowered by her adopting sexual liberation, but rather represents her as lost in a world that is changing around her. Alex’s portrayal in the film subverts the positive connotations of the sign “love,” as in sexual fulfillment/sexual liberation, and introduces the complex feelings of a woman living in Sixties London.

The agonies of love in Sunday Bloody Sunday

Sunday Bloody Sunday subverts the mainstream images discussed in the previous section by introducing a set of signifiers that assign negative meanings to the “love” that is offered by free/open relationships. Feelings of sadness and uneasiness associated with the sign “love” in the film are conveyed through cues both verbal (dialogue) and nonverbal (props, set design, body language, facial expressions, gestures, and sounds). By classifying the signified (emotions) in the film into four categories (confusion, loneliness, fear, and repressed jealousy), as shown in , the deployment of the signifiers to create meaning of frustrations in association with “love” is highlighted.

Love= confusion

In the introductory scene of the film, the camera shows a wide shot of Alex’s home. Scattered clothes, bags, pills, books, liquor, paintings, pillows, and blankets are seen all over her place. A close-up of Alex follows, showing her relentless efforts to reach her boyfriend on the phone. Alex then rushes to grab a pill, which she washes down with liquor. Daylight is visible outside as the camera moves toward the window. Alex looks at her watch several times. She then tries to hold the phone while also holding the glass of liquor.

A state of messiness, represented through scattered items, rushed actions, and facial gestures of worry and stress, signifies Alex’s state of confusion throughout the film. Her relentless search for her boyfriend is shown through the continuous dialing of a phone number, along with anxious eye and body movements. Signifiers used to convey Alex’s messy home and rushed actions illustrate love as a state of confusion.

Confusion is conveyed not only through signifiers of messiness but also signifiers of hesitation when making decisions. In a series of shots later in the film, we see Alex holding her pen and paper to write a resignation letter. Alex crumples the paper, tosses it, then writes another resignation. Alex is especially hesitant when she gets distressed about her relationship with Bob – she resorts to resigning as a form of change but never puts her plan into action. Alex’s love for Bob is portrayed through her anxious reactions and messiness, reflecting a state of confusion. Throughout the film, Alex tries to catch Bob, who is represented as a very elusive character, through the important prop of the phone, discussed in the following point.

Love= fear

The sign “love” connotates a state of fear throughout the film. The first fear is that of loss. Fear of loss stems from the complications of the nature of the romantic relationship that Alex agreed to be in. In her open/free relationship with Bob, Alex agrees to his intimate relationship with a homosexual middle-aged doctor, Daniel Hirsh, who likewise knows of Alex’s existence. Agreeing to such a relationship is a representation of an adoption of the new rules set for sexual liberation.

The triangular relationship between Alex, Bob, and Daniel is presented as if it is a game, a game through which both Alex and Daniel are trying to catch the liberated, elusive creative spirit represented in the youthfulness of the 25-year-old Bob. The telephone is used as a main prop to represent such a game setting. The telephone, either those in the characters’ homes or the answering service both Alex and Daniel happen to use, is the tool through which each of the two lovers tries to catch Bob. It is here that “love” is introduced as a game, where participants are vulnerable to loss. The switching of cables in the answering service office reaffirms a sense of play in which something like hide-and-seek takes place between the characters of the love triangle.

“Love” in Sunday Bloody Sunday also conveys a sense of fear of stagnation. Alex, in her mid-thirties, finds herself in a sort of limbo with neither a fulfilling love/relationship nor a fulfilling career. She’s not in her mid-twenties anymore like Bob, who is open to experimenting with life with less fear. Yet, she’s not old enough to simply surrender to a conventional lifestyle. Fear of stagnation is conveyed through two different sequences of shots through which the dialogue acts as the main signifier of fear. First, the confrontation Alex has with Bob about her dissatisfaction with their relationship reveals both fear of loss and stagnation. In the dialogue, Alex asks Bob about when he will be leaving for the US, and he replies, “In a day or two.” Alex responds furiously that she’s always the one who has to ask to know Bob’s next move. Bob then calmly replies, “I’ll be back, you’ll be here, we can ring each other up.” With a sad gesture, Alex says, “I’m bound to be here.” Alex has a continuous fear of being the person who has to wait, who has to remain stagnant. On the contrary, Bob’s young age, talent, vitality, and self-centeredness fuel his pursuit of new opportunities. Alex sees herself as stuck or “bound to be here,” as in her own words to Bob.

Alex’s subconscious fear of aging, fueled by the age gap between herself and Bob, is reflected in her empathy with George (Tony Britton), a 55-year-old man who comes to her office seeking help in finding a new job. Alex fails to help him and ends up sleeping with him instead. George serves as a representation of the challenges associated with aging in a rapidly changing society marked by growing competition and a demand for highly skilled, energetic, and educated young employees by large corporations. The fear created by the rapid social changes and the individualistic, competitive nature of the neoliberal world where love adds to the confusion is evident in George’s conversation with Alex. Through dialogue, we are introduced to phrases like “put me out to grass” as signifiers of fear of loss and stagnation. George says, “It’s firms like you that are putting me out to grass, me and the other fifty-year-olds,” to which Alex corrects him with a smile, “Fifty-five.”

Another signifier of the fear of stagnation is Alex’s change in haircut by the end of the film. The new haircut signifies an attempt to defy stagnation by making a small, low-risk change, which gives Alex only temporary satisfaction. Even when she decides in a confrontational scene to end her state of continuous fear by telling Bob not to contact her anymore, the decision is not an action but rather a reaction to Bob’s decision to leave for the US. Alex knew that Bob’s trip abroad would likely absorb him and bring their relationship to an end. Therefore, in one way or another, Bob is the one who left her, not the other way around. It is by showing Bob’s reluctance to give in to either Alex or Daniel that a hide-and-seek game is further emphasized.

Amid Alex’s realization that she can’t retain her love for Bob because of its elusive nature or go back to her ex-husband, where she suffered the coldness and stagnation of marital life, Alex ends up feeling ill at ease, lonely, frustrated, and repressing her vulnerability so as not to seem like a needy woman or like a “possessive wife,” as Bob calls her in one scene.

Signifiers of fear and confusion represent Alex in Sunday Bloody Sunday not as an empowered, liberated woman but rather a sad and lonely one. Unlike other Sixties movies, which represented female characters as empowered through their sexuality and openness to the sexual revolution,Footnote35 Sunday Bloody Sunday highlights the agonies and challenges associated with the new social changes.

Love= loneliness

Alex feels lonely most of the time even though she is in a romantic relationship with Bob and even when she is around her own parents. This state of loneliness is reflected in a set of signifiers shown during Alex’s visit to her parents’ place. As they have dinner, we see Alex, her father, and her mother sitting around the table at a remarkable distance from each other. That distance is further signified by the director’s choice of taking a bird’s-eye shot of the three, in which they appear distant and tiny. A gap between the older generation and the younger one is amplified through the set design of the parents’ house in contrast with that of Alex’s house. The house of Alex’s parents has a classic English style that includes luxurious pieces of furniture set neatly in the vast domestic space, completely different from Alex’s modern-styled apartment, which she leaves messy most of the time. Alex’s parents’ choice to keep their home as it was more than thirty years ago when Alex was still a child (as we know from a flashback) signifies their reluctance to change.

The use of sound is also significant here. The silence that allows the ticking of a clock to echo as Alex eats dinner with her parents reflects her feelings of loneliness and emptiness. Then, as a fierce dialogue takes place between mother and daughter after dinner, the still-audible ticking of the clock amplifies the feeling of a heightened struggle, as if the ticking is their heartbeat.

Loneliness stems not only from the crack that grew bigger between the two generations due to social change but also from Alex’s relationship with Bob, which was supposed to liberate and comfort her but ended up increasing the void. Alex saw coldness, loneliness, and lack of romance in her parents’ marriage but failed to make her open romantic relationship with Bob a remedy for the failure of the system of marriage. Dialogue is introduced as an important signifier here as a fierce conversation takes place between Alex and her mum when the father goes to finish some business-related calls. The mother criticizes Alex’s “on and off” relationship with Bob. Alex fights back by hinting at her parents’ imperfect marriage, saying, “I can’t see that having an affair with someone on and off is any worse than being married for a course or two at mealtimes.” Alex is convinced, as the dialogue shows, that loneliness exists within marriage; however, she can’t find a real feeling of intimacy and companionship through the mode of free relationship she has adopted.

Feelings of loneliness are also signified in Alex’s reaction to Bob’s decision to go and spend the night with David during his vacation with her. Alex has to wait for Bob at their friends’ place where she is taking care of her friends’ children. To fill the void and overcome her feelings of loneliness, she picks up one of the children and tries to play with her, but the child refuses and goes back to her toys. The series of shots as the child returns to her toys while Alex stares at the window crying reflects the feeling of being left behind. Alex’s fixed position amid the changing world is represented in the movement of the child away from her to signify loneliness and stagnation. In her study of Sunday Bloody Sunday’s authorship, Barber describes the characters’ unease with their relationships as a reflection of how “sex and love have become commodities and that although free love and free sexual experience have offered pleasure, they did not promise any lasting feeling of fulfilment, thus what is usually left is emotional unease and bitterness.”Footnote36

Love= repressed jealousy

Confined by the rules of the open relationship, Alex and Bob repress their feelings of jealousy. Bob in particular is reluctant to acknowledge his jealousy when he sees a man at Alex’s place one night. It seemed to him that Alex was engaging in some sexual behavior with the man before Bob arrived and disrupted it; however, he couldn’t object. Glances and presentation of shots, as Browne suggests, represent depictions of a “state of mind.”Footnote37 If we apply this to Sunday Bloody Sunday, then Bob’s state of mind may be determined throughout a series of shots in which his glances imply feelings of jealousy.

In the sequence of shots where Bob shakes hands with the man (George) at Alex’s place, we see him looking at George up and down as if trying to figure out what Alex likes about him. It seems as if, in looking at George, Bob is evaluating his own self. In the next series of shots, Bob tries not to look when Alex and George kiss goodbye, and as soon as Alex turns her back to lead George to the door, Bob grabs his jacket petulantly and throws it to the side. Bob stares at the liquor in front of him for a while before George yells goodbye, and Bob replies with an exaggerated smile, “Goodbye.” When George leaves, Bob says, “It looked as if I was interrupting something,” but Alex pretends not to pay much attention and changes the topic. Alex and Bob then sleep together, and when the morning comes, Bob asks Alex while she’s lying in his arms, “Who was that man last night?” Alex explains that he is a man from the office and asks Bob, “Do you mind about him?” wishing he could express his jealousy. Instead, Bob replies in a very calm and steady manner, “No.” She then repeats, “You really don’t mind about that, do you?” Bob answers in a cheerful tone, “No, not a bit. We’re free to do what we want.” A close-up of Alex’s gestures and facial expressions shows utter frustration with Bob’s answer and his reluctance to admit being jealous even a bit.

Alex also represses her feelings of jealousy. When she finally manages in one of the scenes to express her dissatisfaction with Bob’s decision to leave amid a vacation they were having together and spend the day with his boyfriend, Daniel, he sternly responds, “Don’t go on at me like some possessive wife.” Bob uses that phrase to push back Alex’s argument by reminding her that they are not part of a martial institution where partners are bound by each other. Furthermore, it conveys a perception of marriage as an institution in which the partners possess each other.

Bob tries to surmount his feelings of jealousy by putting himself first, which leads him to become more self-centered. Bob willingly puts off his feelings of jealousy for the sake of maintaining his freedom. Alex, on the contrary, consumes herself thinking of how her life went wrong. A divorcee who left the old orthodoxy of marriage in search of a new life, she finds her new life not necessarily better than what she lost. Torn between her feelings of love for Bob and her frustration with the relationship, she is always consumed by negative thoughts about how much she hates her work, her parents’ cold relationship within a traditional marriage, and her feeling of continuous emptiness even with the sexual liberation she is enjoying.

Conclusion

While social change has its merits, it is naive to think that it comes without hurdles. Social change usually invokes uncertainty and fear in those who witness and live amidst it. Through a semiotic analysis of Sunday Bloody Sunday, the study has discussed the agonies of social change as it appeared in the film. By deploying a series of signifiers, the film signifies challenges associated with the free/open relationships developed during the sexual revolution.

In the film, Alex perceives marriage as a restrictive institution that pushes partners to become the property of one another. However, the love offered as a solution, represented in casual sex and free/open relationships, cannot fulfill her need for peace, comfort, companionship, and the true freedom she yearned for. Considering the film contextually, Sunday Bloody Sunday subverted mainstream representations of the popular culture of the time by refraining from portraying Alex as an empowered and fulfilled woman as a result of the sexual revolution. It also refrained from using mainstream signifiers like psychedelic aesthetics, normalized drug use, extraordinary costumes, and eroticism that were usually used to represent the Sixties in popular films.

To create such subversion, Gilliatt and Schlesinger assigned negative meanings to “love” associated with the advent of the sexual revolution by using signifiers of fear of loss, loneliness, and stagnation. The recurring use of the telephone and switching of cables as the means through which Alex and Daniel try to catch their lover Bob emphasizes a game setting where loss is possible. They also contribute to a process of signification that portrays “love” as problematic and suffocating. In one scene, we hear Alex talking to herself while looking at Bob, saying, “I love you a lot, I don’t want you to go.” But she can’t utter these words, because if she did, she would become the image of a “possessive wife,” a burden, and “asking for too much,” as Bob once told her. Brown hints at the dark side of this form of open/free relationship between Alex, Bob, and Daniel, stating, “The three characters have an open arrangement; there is no deception among them, except the refusal to acknowledge the pain caused by the arrangement.”Footnote38 The repression of what is known in social psychology as “reactive jealousy”Footnote39 in Sunday Bloody Sunday reflects how “love” that transcends sexual pleasure can make one feel ill at ease.

“Love” in Sunday Bloody Sunday is the desire for what is absent, for what cannot be fulfilled through sexual pleasure; it is the desire to replace fears of the modern world with feelings of security and companionship. Therefore, “Love” in Sunday Bloody Sunday becomes a continuous yearning and a continuous pain, not continuous freedom, emancipation, and happiness. The sign “Love” in the film also carries meanings of loneliness. Loneliness occurs as a consequence of having to detach oneself from one’s beloved in order to maintain a sense of freedom and individualism, which are encouraged and enhanced through the neoliberal ideology that swept the world after the failure of the 1950s welfare state. Repressed feelings of vulnerability and the need for others are the agonies of the social change of the Sixties, which continue to exist to this day.

Schlesinger, through the use of a series of signifiers, was able to show how “love” – which was tied to liberation during the Sixties and Seventies – can be quite suffocating. By delving into the personal lives of the film’s characters amid social change, Gilliatt and Schlesinger were able to challenge the mainstream positive connotations of the sign “love.” Barber contends that Sunday Bloody Sunday shows that a meaning of love that transcends sexual pleasure cannot exist where the sign “love” has been appropriated and permeated with the market ideology that commodified it.Footnote40 The neoliberal ideology which was put forward as a replacement for the welfare state prioritized market ideals that encouraged individualism and the sexualization of women, and linked sexual liberation (especially concerned with the female body, as Baudrillard suggests) to commodity production.Footnote41

So, if love is really “all we need,” as the Beatles’1967 song says, what kind of love is that? And how can it be achieved? If love means more sex as a result of sexual liberation, or an increased consumption of pornographic material as encouraged by a neoliberal ideology, will it really be all that we need? Romantic relationships depicted in the film, as Brown puts it, “portend that political and social advances do not necessarily solve the problem of love.”Footnote42

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Oleszczyk and Ramon, “A Queer Pioneer: Sunday Bloody Sunday on Its Fiftieth Anniversary – A Conversation between Michał Oleszczyk and Alex Ramon.”

2. Bell, “Young, Single, Disillusioned”

3. The signifier-signified refers to the form in relation to content. The signifier in film analysis, as proposed by Metz, comprises words spoken, images, sounds, the organization of images, facial expression, and the dress of the characters, while the signified is the social content of the film, the psychology of the characters, the ideological message of the film, etc. See Metz, “Methodological Propositions for the Analysis of Film,” 89–101.

4. Barber, Using Film as a Source, 62.

5. Stam, Film Theory: An Introduction.

6. Ibid., 142.

7. Metz, “Methodological Propositions”

8. Ibid.

9. Bazin, “Every Film Is a Social Documentary”

10. Ibid., 41.

11. Tom, “Social Constructs in Film Culture”

12. Kuntzel, “The Film-Work 2.”

13. Weir and Wilson, “The British Women’s Movement,” 74–103.

14. Van der Tuin, “Feminisms, First, Second, and Third Wave,” 1–5.

15. Cook, “The English Sexual Revolution,” 109–28.

16. Willis, “Toward a Feminist Sexual Revolution,” 21.

17. Ibid., 3–21.

18. Mirowski and Plehwe, The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective.

19. Jameson, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 4.

20. Rickards, “The Rise and Fall of the Colorful Corporate Fantasy in 1960s British Cinema.”

21. Jameson, Postmodernism, 4.

22. Weichold and Barber, “Introduction to Social Change,” 1–2.

23. Office for National Statistics (ONS), Divorces in England and Wales: 2012, 2014.

24. Booker, The Neophiliacs.

25. Ibid., xiv.

26. Satchell-Baeza uses the term “mass hysteria” to describe youth fascination with the discotheque as a dreamlike world. Booker originally used the term to describe the powerful mass fascination with products, film stars, models, singers, and unconventional forms of art made possible through advancements in technology and mass media. See Satchell-Baeza, “Panic at the Disco,” 251, and Booker “The Neophiliacs,” 9.

27. Glen, “Freak Scene,” 45–68.

28. Ibid., 52.

29. Murphy, Sixties British Cinema.

30. Gibson, “The Fashioning of Julie Christie and the Mythologizing of ‘Swinging London’.”

31. Baudrillard, Consumer Society.

32. Marwick, The Sixties, 18.

33. Bell, “Young, Single, Disillusioned”

34. Ibid., 81.

35. Rickards, “Rise and Fall”

36. Barber, “Sunday Bloody Sunday: Authorship, Collaboration and Improvisation,” 88.

37. Browne, The Rhetoric of Filmic Narration, 11.

38. Brown, The Films of John Schlesinger, 128.

39. Barelds and Barelds-Dijkstra, “Relations between Different Types of Jealousy and Self and Partner Perceptions of Relationship Quality.”

40. Barber, “Sunday Bloody Sunday;” Frank, The Conquest of Cool.

41. Baudrillard, Consumer Society.

42. Brown, The Films of John Schlesinger, 137.

Bibliography

- Barber, Sian. “Sunday Bloody Sunday: Authorship, Collaboration and Improvisation.” In The British Film Industry in the 1970s, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Barber, Sian. Using Film As a Source. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

- Barelds, Dick P. H., and Pieternel Barelds-Dijkstra “Relations Between Different Types of Jealousy and Self and Partner Perceptions of Relationship Quality.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 14, no. 3 (2007): 176–188.

- Baudrillard, Jean. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. London: SAGE Publications, 1998.

- Bazin, André. “Every Film Is a Social Documentary.” Film Comment 44, no. 6 (2008): 40–41.

- Becker, Julia, Lea Hartwich, and Alexander S. Haslam “Neoliberalism Can Reduce Well-Being by Promoting a Sense of Social Disconnection, Competition, and Loneliness.” British Journal of Social Psychology 60, no. 3 (2021): 947–965. doi:10.1111/bjso.12438.

- Bell, Melanie. “Young, Single, Disillusioned: The Screen Heroine in 1960s British Cinema.” The Yearbook of English Studies 42, no. 1 (2012): 79–96. doi:10.1353/yes.2012.0010.

- Bellour, Raymond. “The Obvious and the Code.” Screen 15, no. 7 (1974-75): 7–17.

- Booker, Christopher. The Neophiliacs: A Study of the Revolution in English Life in the Fifties and Sixties. London: Collins, 1969.

- Bousalis, Rina R. “The Counterculture Generation: Idolized, Appropriated, and Misunderstood.” The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies 82, no. 2 (2021). https://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol82/iss2/3.

- Brown, Julia Prewitt. The Films of John Schlesinger. London: Anthem Press, 2019.

- Browne, Nick. The Rhetoric of Filmic Narration. Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1982.

- Cook, Hera. “The English Sexual Revolution: Technology and Social Change.” History Workshop Journal no. 59 (2005): 109–128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472788.

- Fitzgerald, Melissa, director. Summer of Love, 1967. TV Documentary, United Kingdom. London: BBC, 2006.

- Frank, Thomas. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Gibson, Pamela Church. “The Fashioning of Julie Christie and the Mythologizing of ‘Swinging London’: Changing Images in Sixties Britain.” In Film, Fashion, and the 1960s, 135–148. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017.

- Glen, Patrick. “Freak Scene: Cinema-Going Memories and the British Counterculture of the 1960s.” The Sixties 12, no. 1 (2019): 45–68. doi:10.1080/17541328.2019.1603935.

- Guerrero, Laura, and Peter A. Andersen. “Emotion in Close Relationships.” In Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, edited by A. Hendrick Clyde and S. Susan, 171–183. California: Hendrick. Sage Publications, 2013.

- Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, N.C: Duke University Press, 1991.

- Kuntzel, Thierry. “The Film-Work, 2.” Camera Obscura 2, no. 5 (1980): 6–70.

- Marwick, Arthur. The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, C. 1958–C.1974. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Metz, Christian. “Methodological Propositions for the Analysis of Film.” Screen (London) 14, no. 1–2 (1973): 89–101. doi:10.1093/screen/14.1-2.89.

- Mirowski, Philip, and Dieter Plehwe The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Murphy, Robert. Sixties British Cinema. London: BFI, 1992.

- Oleszczyk, Michał, and Alex Ramon “A Queer Pioneer: Sunday Bloody Sunday on Its Fiftieth Anniversary a Conversation Between Michał Oleszczyk and Alex Ramon.” Cineaste 46, no. 3 (2021).

- Rickards, Carolyn. “The Rise and Fall of the Colorful Corporate Fantasy in 1960s British Cinema.” In Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered, 179–192. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022. 10.1515/9781474443906-014.

- Satchell-Baeza, Sophia. “Panic at the Disco: Brainwashing, Alienation and the Discotheque in Swinging London Films.” In Sixties British Cinema Reconsidered, 239–254. Edinburgh University Press, 2020. 10.3366/j.ctv10kmdzz.20.

- Stam, Robert. Film Theory: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2000.

- Tom, Eileen W. “Social Constructs in Film Culture: The Effect of it on the Performing Arts, and the Destroyed Association of Signs to Enhance Meaning.” Honors thesis., Portland State University, US, 2014.

- Van der Tuin, Iris “Feminisms, First, Second, and Third Wave.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender And Sexuality Studies, edited by M. Wong, R. Wickramasinghe, R. Hoogland, and N.A. Naples, 1–5. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedias in Social Science, 2016.

- Weichold, Karina, and Bonnie Barber “Introduction to Social Change and Human Development.” International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development Bulletin 1, no. 55 (2009): 1–2.

- Weir, Angela, and Elizabeth Wilson “The British Women’s Movement.” New Left Review 1, no. 148 (1984): 74–103.

- Willis, Ellen. “Toward a Feminist Sexual Revolution.” Social Text, no. 6 (1982): 3–21. doi:10.2307/466614.