ABSTRACT

This study explored therapeutic foci’s structural change and its interaction with clinical severity in a young adult patient receiving psychodynamic therapy. We conducted a systematized single-case time-series analysis for a complete focused psychodynamic treatment (54 sessions). To assess clinical severity, the patient completed the Outcome Questionnaire 45.2 every session. Two external raters established a psychodynamic profile with five therapeutic foci for the case, using Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis. These foci included one relational focus, two conflict foci and two structure foci. Raters estimated patient’s structural change by means of Heidelberg Structural Change Scale, assessing the evolution of such foci. Raters used this measure to code every session. We conducted a vector autoregressive analysis to explore therapeutic foci’s structural change and its interaction with clinical severity. Time-series analysis showed predictive effects of foci’s structural change throughout the entire treatment. Greater structural change in the relational focus predicted greater clinical severity and less structural change in conflict foci. Also, greater structural change in conflict foci predicted greater structural change in structure foci. Results support the hypothesis of structural modifications as a mechanism of change for psychodynamic therapy. We discuss results to better understand how patients may benefit from psychodynamic therapy.

The study of change in psychotherapy

In the field of clinical psychology, more than 400 psychotherapeutic models have been described (see, for example: Feixas & Miró, Citation1993; Lambert, Citation2013). They propose various theories about mental functioning and its pathological forms, as well as different techniques to address these problems. At the same time, these widely heterogeneous models of psychotherapy share a common objective: to produce change or a modification of the patient’s initial condition. Consistently, over the last decades, psychotherapy research has increasingly focused on the assessment of change.

In this context, the notion of change is related to different aspects. On the one hand, as mentioned above, change of a patient’s initial situation is the ultimate outcome expected from a psychotherapy. In this sense, “change” is the result of the treatment. On the other hand, the concept of “mechanisms of change” refers to the intermediate steps that, throughout a treatment, end up resulting in the expected modifications for the patient’s situation. While different models of treatment are all interested in producing change, we still lack consensus about these intermediate steps and trajectories that lead to substantial modifications. In this sense, although several efforts have recently been developed (see, for example: Gallagher et al., Citation2020; Hofmann et al., Citation2020), more research is needed to better identify (a) which are the core mechanisms of change that take place during psychotherapy, and (b) which are the best ways to identify such mechanisms from a methodological point of view (Delgadillo & Lutz, Citation2020; Gómez Penedo & Roussos, Citation2012; Gómez Penedo et al., Citation2017).

Structural change in psychodynamic therapy

Barber et al. Citation(2013, Citation2015) reviewed the mechanisms of change underlying psychodynamic therapies which had been operationalized and undergone testing. They found five mechanisms, including gaining insight, increasing adaptive defenses, decreasing rigidity, improving the quality of object relations, and increasing reflective functioning. With regard to these mechanisms, research suggests that (a) a poorer quality of object relations is associated with greater symptomatology, (b) insight, defenses, and the quality of object relations change along with symptoms and that (c) defenses and the quality of object relations moderated therapy outcome (see, e.g., Crits-Christoph et al., Citation2013; Levy et al., Citation2006).

From Barber and Sharpless Citation(2015) review, we would like to highlight the interaction between symptom reduction and other dimensions of patient improvement (i.e., quality of object relations, defenses, and reflective functioning) that can be subsumed under the psychodynamic construct of “structural change”. Structural change can be defined as one of the core change dimensions of psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy (Freud, Citation1926). Historically, psychoanalysis has postulated the notion of structural change as a special type of modification that is assumed to account for particularly persistent effects (Rapaport, Citation1960). The term “‘structure’” refers to the stable organizations of personality and habitual patterns that patients employ when dealing with problem areas. Grande et al. Citation(2009) pointed out that it is assumed that changes at this deeper level of personality are essential in attaining persistent therapeutic effects at all levels (see also: OPD Task Force, Citation2007). In this sense, structural change can be understood as a core mechanism of change in psychodynamic therapy. If a patient improves in terms of structural change during psychodynamic therapy, this, in turn, would lead to a decrease in patient’s clinical severity at the end of the treatment. Previous research has partially endorsed such hypothesis (Grande et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Leuzinger-Bohleber et al., Citation2019). However, more empirical research is needed to gather evidence that supports this assumption, by means of strategies allowing to operationalize the concept of structural change.

Evaluating therapeutic foci in order to assess structural change

Research on psychodynamic therapy has shown that choosing and maintaining a focus is, by itself, helpful in facilitating positive outcome (Diamond et al., Citation2014; Diener et al., Citation2007; Summers et al., Citation2013). These previous works emphasized the importance of a focus in the therapeutic process, as it may help therapists gain a clearer and more coherent understanding of their patients’ psychopathology and thus result in better outcomes for patients. Silberschatz and colleagues’ work on Plan Formulation Method showed similar results. Therapists who follow this structured strategy to formulate their cases and establish therapeutic foci tend to achieve better results with their patients, in contrast to therapists who do not (for a review, see: Silberschatz, Citation2017).

Psychodynamic theory and technique understand therapeutic foci as the patient’s core psychodynamic problems (OPD Task Force, Citation2007; Summers & Barber, Citation2010). Foci carry the status of psychodynamic hypotheses. This implies that some level of change must take place in relation to these problem areas to achieve a reduction or elimination of the patient’s symptoms and complaints. The levels of change depend on the ways patients struggle with such problem areas, and the degree to which every focus is worked on during treatment.

Research has shown that the degree to which a patient deals with and integrates such problem areas gives a reliable measure of structural change (Dagnino et al., Citation2014; Grande et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Juan et al., Citation2017, Citation2021). Such studies observed that therapeutic foci’s evolution was connected to longstanding and multi-level changes in terms of relational patterns, intrapsychic conflicts, and personality functioning; three key aspects of structural change (OPD Task Force, Citation2007; Rudolf, Citation2006 [2017]). One possible research strategy to assess structural change is to systematically register the evolution of therapeutic foci that unfold along a focused psychodynamic treatment.

Time-series single-case research: an opportunity to assess mechanisms of change in focused psychodynamic therapies

The question of the best strategy for assessing the mechanism of change also concerns the type of methodological design that is appropriate. One valid option is the use of case studies that systematically assess change throughout treatment.

Kächele et al. Citation(2009) concluded in their review of psychoanalytic single-case studies that most of the available data lacked systematic criteria that would allow robust empirical research. This is due to the use of non-systematic single-case narratives and vignettes. Facing this evidence, Kächele et al. Citation(2009) suggested going beyond psychoanalytic narratives and towards systematic empirical single-case studies. Authors consider this methodological change a powerful way to identify core aspects of process and outcome in psychoanalysis and psychodynamic approaches. In the same line, more recently, some works have suggested the use of time-series single-case psychodynamic research that analyzes repeatedly measured process and change variables along treatments (Gottdiener & Suh, Citation2012; Tillman et al., Citation2011). However, research that employs these methodological approaches is scarce (see, e.g., Boswell et al., Citation2014; Roussos et al., Citation2016).

In this context, by considering changes over time within a patient, a time-series single-case study can be useful to identify how patient’s structural change interacts with other change dimensions (i.e., clinical severity) along a complete focused psychodynamic treatment. This, in turn, may contribute to the identification of mechanisms of change (Hayes et al., Citation2007; Luyten et al., Citation2017; Zilcha-Mano & Barber, Citation2014). Ultimately, this knowledge might help to enhance psychodynamic psychotherapy processes and outcome.

Study’s aims and hypotheses

The present study explored therapeutic foci’s structural change and its interaction with clinical severity, in a young adult patient receiving psychodynamic therapy. We conducted a systematized single-case time-series analysis of a complete focused psychodynamic treatment of 54 sessions. We formulated two main scientific research questions: (1) how does foci’s structural change predict subsequent clinical severity? and (2) how does structural change of certain foci predict subsequent structural change on others? Two hypotheses were tested: (1) greater foci’s structural change predicts less clinical severity along treatment, and (2) greater structural change of a certain focus (relation, conflict, or structure) predicts greater structural change of the same focus along treatment. We refer to “foci’s structural change” because we have studied structural change assessing the evolution of therapeutic foci during treatment (see measures & procedures).

Methods

Participants

Patient

At the time of the consultation, Gonzalo (pseudonym), a middle-class young man, was 30 years old and single. He lived alone and worked in an important software company in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He had undergone his first treatment 8 years earlier because he “needed a space for himself”. His current reason for consultation was related to feeling caught up in relationship problems, involving two partners he had in parallel (Susan & Laura). Specifically, Gonzalo came to therapy 3 months after Laura had broken up with him once she had discovered a parallel relationship with Susan. Losing this partner caused Gonzalo a lot of anxiety, discouragement, a feeling of emptiness and loneliness. Gonzalo said that he had “never felt so bad”, and that he believed he had “gotten depressed”. Gonzalo understood “getting depressed” as being sad at home and feeling lonely; but when questioned, no concrete symptoms of depression nor suicidal ideation or risk were present. He had no history of serious emotional crises, hospitalization, or risk to himself or others. Gonzalo did not consume drugs, except for alcohol which could become excessive when he went out.

Gonzalo’s appearance was well groomed, and he accompanied it with a gentle and kind, even seductive manner at times. He was cooperative and expressed himself broadly about his situation. The therapist responsible for the referral had presented the patient as a young man who consulted for relationship problems with women. The referrer described him as a “calm, healthy patient, but with conflicts to be with only one woman”.

During the first interviews, Gonzalo elaborated on his reason for consulting, explaining: “I come here because today what is happening to me is hurting a person I love. And I am also hurting myself. I have had a love relationship with Susan for 9 years. In those years I was with other people. A year and a half ago I met Laura. I am not living a normal situation. Besides, there were other sporadic relationships”. In exploring this situation, Gonzalo showed distress and worry. He also commented on a first engagement in his early adolescence that had marked him and, since then, he had never been able to be with one woman, only.

Towards the end of the diagnostic process, he stated: “More than anything else, I wonder whether or not I really want to be in a couple, uh… to be in a relationship with only one person and aim to be happy with… with only one person”. With respect to these situations, he commented that he liked to feel that women liked him as a man, adding that he had to do things in a perfect way so that no one would find out. He also clarified that he did not regret having always done what he felt.

When the therapist inquired him about possible reasons for this repetitive behavior, Gonzalo stated that he had never been sexually fulfilled by a woman, and that routine bored him. He also supported this reasoning by arguing that most of his friends and acquaintances cheated on their partners.

As a spontaneous reflection during the first interviews, Gonzalo reported that he was tired of living “a lie”, and that he would like to be able to feel fulfilled with one woman, and “to function in a different way”. He described good family relationships with both his parents (married) and two brothers. He further reported feeling good at work and presented good work performance.

By means of the OPD-2 (see measures & procedures) Gonzalo’s therapeutic foci were formulated in terms of (a) relational dysfunctional patterns, (b) intrapsychic conflicts and (c) structural vulnerabilities. To gather a more comprehensive clinical context of the case, we include the OPD-2 foci identified for Gonzalo by external judges in the results section, in .

Therapist

At the time of initiating treatment, the therapist was 38 years old and had 13 years of clinical experience. He specialized in psychodynamic psychotherapy and was also internationally certified in the use and training of the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnosis (OPD-2). He is the first author of the present work and fulfilled the dual role of therapist-researcher in the context of a Practice-Research Network.

Treatment: focused psychodynamic therapy following OPD-2 criteria

We worked with a focused psychodynamic therapy approach (Kächele, Citation2010; Luborsky, Citation1984; Sifneos, Citation1987). This approach implies that the therapeutic work can be consistently focused on a pathogenic process with unconscious roots, driven by intrapsychic conflicts or structural vulnerabilities (Summers & Barber, Citation2010; Thoma & Kachele, Citation1985 [1989]). Thus, the treatment aims at both the patient gaining awareness of unconscious conflicts and developing healthier functioning of his or her psychic structure (Rudolf, Citation2006 [2017]). In accordance with these general principles, OPD-2 (OPD Task Force, Citation2007) offers a systematic method for selecting therapeutic foci during treatment. The patient’s core problem areas (i.e., OPD-2 foci) were defined using information from the OPD-2 axes (see measures, procedures, and ). The OPD-2 foci carried the status of psychodynamic hypotheses. This implies that some level of change had to take place in relation to these areas to achieve a reduction or elimination of the patient’s symptoms and complaints.

In this sense, firstly, treatment aimed at establishing and agreeing with the patient his central problem areas to work on, based on the construction of a good therapeutic alliance. Once the OPD-2 profile of the case was established (see procedures & ), the therapist’s interventions aimed at Gonzalo gaining insight into his unconscious role offering (relational focus according to OPD) and his repetitive intrapsychic conflicts (conflict foci according to OPD). This formed the basis of the expressive line of treatment, based on the use of interventions that offered Gonzalo new ways of understanding his motivations and behaviors, such as confrontations and interpretations. In a complementary way, the work on his structural functions (structural foci according to OPD) was based on supportive strategies. This involved the use of affirmative interventions, validation of the experience, and the use of the therapeutic relationship as a corrective emotional experience, from which Gonzalo could restore and develop less integrated structural functions.

The process included three diagnostic interviews and 54 subsequent treatment sessions. The total length of the treatment was 21 months, beginning in May 2018 and ending in February 2020. The first 45 sessions were of weekly frequency, after which a gradual process of termination was agreed upon with the patient, where the sessions were spaced out, first bi-weekly and then monthly.

Treatment ended because Gonzalo referred a global sense of recovery from his initial symptoms, made relevant changes in his relational problems, and was more insightful regarding his conflicts and structural issues, shown in . Specifically, he could separate from Laura and try to commit to a stable couple relationship with Susan. This also implied that he could elaborate on his conflict with self-sufficiency, was more regulated and able to bond and detach. Although patient and therapist both considered that Gonzalo’s relational, conflict and structural issues might need further treatment, they agreed that this first psychotherapy could end and left the possibility of a future second treatment, whenever Gonzalo decided to recontact the therapist.

As we have stated, within the focused psychodynamic therapy delivered, the OPD-2 foci identified for Gonzalo (see ) formed the framework to understand the interventions, the overall context of the sessions and the termination process. It is important to remark that, for methodological reasons (see statistical analyses), the present paper did not involve the predictive effects of the interventions nor the therapeutic alliance. In other ongoing studies (Juan et al., Citation2022) our research team is analyzing these elements of the therapeutic process of Gonzalo that may complement the results observed here.

Measures

OPD-2 (OPD task force, 2007)

The OPD-2 was the main tool used in this study for case formulation and foci establishment. It is an instrument used to perform a systematic clinical evaluation of a patient based on five psychodynamic axes: 1) experience of illness and prerequisites for treatment, 2) relational patterns, 3) intrapsychic conflicts, 4) structural functioning and 5) mental disorders according to DSM-ICD systems. Based on the information provided by the axes, up to five therapeutic foci are chosen to conduct the treatment. The OPD-2 considers relational patterns, intrapsychic conflicts, and structural (personality) functioning as possible therapeutic foci for a given patient. In this study, two external raters developed a complete OPD-2 profile for the patient and established five therapeutic foci: one relational focus, two conflict foci and two structure foci. Each of these foci were then assessed in terms of their evolution during treatment, to estimate foci’s structural change (see below and procedures).

Heidelberg Structural Change Scale (HSCS; OPD task force, 2007, Rudolf et al., Citation2000)

The HSCS is a modified version of the Assimilation of Problematic Experiences Scale (APES, Stiles et al., Citation1990), more strongly oriented towards a psychoanalytic model of process and change by Rudolf et al Citation2000, Citation2001). The HSCS was later included as part of the OPD-2 manual previously described (OPD Task Force, Citation2007). It is structured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (defensive rejection of the focus) to 7 (dissolution of the focus/problem integration). Each point marks a therapeutically significant step, beginning with increasing awareness of a previously unperceived problem area, extending to the therapeutic working through of associated aspects and experiences, and then to subsequent basic changes in both the patient’s experience and specific external behavior. The dimensions that the HSCS offers to operationalize the described trajectory include (a) the change from the attribution of excessive demands by others towards one’s own participation in conflicts; (b) the change from defensive rigidity to the flexibilization and awareness of defenses; and (c) the inclusion of new possibilities of experiences and behaviors. The complete stages of the HSCS are as follows: (1) defensive rejection of the focus, (2) unwanted presence of the focus, (3) vague awareness of the focus, (4) acceptance and exploration of the focus, (5) dissolution of old structures in the area of the focus, (6) reorganization in the focal area, (7) dissolution of the focus, problem integration. For a better understanding of the HSCS, summarizes the seven stages included in the scale.

Table 1. Heidelberg structural change Scale (HSCS, OPD Task Force, Citation2007; Rudolf et al., Citation2000, Citation2001)

Previous studies (i.e., Grande et al., Citation2001, Citation2009, Citation2012) have shown good reliability and predictive validity of the HSCS. For this study, HSCS was applied to every session by two external raters to assess the way in which the patient dealt with the problem areas represented in each selected OPD-2 focus, in terms of (a) relational patterns, (b) intrapsychic conflicts and (c) structural functioning. Thus, when presenting results and discussion, we will refer to structural change of relation, conflict and structure foci, respectively.

Outcome questionnaire 45.2 (OQ-45; Lambert et al., Citation1996; adapted to Spanish by; von Bergen & de la Parra, Citation2002)

The OQ-45 is a 45-item, self-report questionnaire, on a 5-point Likert scale, to measure patient distress in symptoms, social role performance, and interpersonal relations. We used OQ.45.2 to measure patient’s clinical severity along treatment (see procedures). In Argentina, the Spanish version of the questionnaire has shown good internal consistency (α = .92), test—retest reliability (r = .864), concurrent validity, and sensitivity to change (Fernández-Álvarez et al., Citation2005).

Procedure

The patient was invited to participate, considering he met a suitable psychodynamic profile for the study, in terms of a clinical situation that comprised both relational problems, intrapsychic conflicts and structural functioning vulnerabilities (see OPD-2 foci identified for the case in the results section, ). That gave external judges enough OPD-2 foci’s delimitation so that we could later perform the time-series analysis. In addition, we wanted to capture a “treatment as usual” situation, of a young outpatient seeking therapy due to an emotional disorder combined with interpersonal problems.

Table 2. OPD-2 foci identified by raters to assess structural change during treatment

At the onset of treatment, we obtained patient’s oral and written informed consent for participation in the study. Treatment took place in the therapist’s private practice, in a face-to-face setting of weekly sessions. All interviews (3) and sessions (54) were audio-recorded. The three interviews were also transcribed. After each session, the patient completed the OQ-45.2.

Two trained external raters established a psychodynamic profile with five therapeutic foci for the case, using OPD-2 based on the transcripts of the first three interviews. Raters coded the material following a consensus criterion: each rater first coded separately and then both raters gathered to reach a consensus version of the coding. In this regard, we did not estimate the inter-rater agreement.

In line with the OPD Task Force’s Citation(2007) guidelines, raters selected one relational focus, two conflict foci and two structure foci. Each focus’ structural change was then assessed by the same external raters, using HSCS (see measures), coded each session. As sessions were not transcribed, raters coded HSCS scores listening to the audio-recordings only. Once again, here, raters coded the material following a consensus criterion: each rater first coded separately and then both raters gathered to reach a consensus version of the coding, for each of the 54 treatment sessions. In addition, raters developed through consensus a narrative vignette for each HSCS coding that included the rationale of the score rated in each session. We offer examples of such vignettes in the results section, in . To control for potential biases, the 54 sessions were randomly delivered to raters. We did not estimate the inter-rater reliability for the HSCS coding, either.

Consensus across raters was based upon Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR, Hill et al., Citation1997, Citation2005) guidelines. We followed CQR recommendations in that raters first coded separately and then gathered to reach consensus. Also, in that they repeated the process if consensus was not fully reached. In addition, we applied CQR’s guidelines for the wording process in the construction of the narrative vignettes. Raters did not inform about significant points of difference that needed working through during the process. This might be due to the previous training they received that was aimed, precisely, to generate a common criterion for both OPD-2 and HSCS’s ratings, as we detail below.

The first author imparted a previous 40 hr training for both raters in the use of the OPD-2 and the HSCS, following OPD Task Force Citation(2007) guidelines. Raters were two students of our research team, and one of them is the second author of this paper. They were part of the research project, under the coordination of the first author.

Training consisted of incorporating OPD-2’s and HSCS’s criteria and to practice coding clinical material transcripts and audio-recorded sessions, gaining feedback from the trainer and repeating the process. Raters’ coding was also compared to experts’ coding of the same clinical material. For HSCS coder training, we employed the Spanish translation of HSCS manual, developed by Röst and De la Parra Citation(2009). Once training was completed, the rating process of the case (Gonzalo) was not supervised by the trainer, given that he was also the treating therapist and remained blind to external raters’ coding. Likewise, raters remained blind to treating therapist´s OPD-2 profile of the case. This was decided to limit, at least in part, the therapist’s biases as he played the dual role of therapist-researcher. These procedures intended, also, to address possible raters’ biases considering their work relationship with the first author. For this study, we used only external raters’ OPD-2 profile in the analysis.

Since three interviews were conducted to establish the OPD-2 profile, we considered scores after interview three as baseline. We performed data analysis considering the HSCS scores of the relational focus, the average HSCS scores of the two conflict foci and the two structure foci, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Once the patient completed treatment, we analysed the variations among the variables of interest considering the entire psychotherapy of 54 sessions, performing a time-series analysis following previous applications in the field (Roussos et al., Citation2016). More specifically, we ran multivariate vector autoregressive models (VAR; Pfaff, Citation2008), analysing the autoregressive and cross-lagged (lag = 1) effects of (a) change in relation focus, conflict foci and structure foci (i.e., structural change) and (b) change in clinical severity. Analyses were conducted with the package vars (Pfaff, Citation2008), from R (R Core Team, Citation2021). A limited use of dependent variables is recommended when conducting time-series analysis. In this regard, we only employed OQ.45.2’s total scores and subscales were not included in the data analysis. This also explains why, although alliance measures were registered, we did not consider them in the present study.

We conducted four models, one for each dependent variable (i.e., relation focus, conflict foci, structure foci, and clinical severity). Our main statistical question was: which measures’ scores in a previous session (time-1) predicted measures’ scores in the next session (time), during the whole treatment? In this sense, the analyses performed do not refer only to the prediction of one session over another. Instead, they take into consideration all 54 sessions, estimating on average how each session predicts the subsequent one. In other words, we estimated differences for a specific subject along time, regarding the association among the change dimensions. Thus, we intended to find exploratory evidence for mechanisms of change within the single case analysed.

Results

Clinical severity trajectories for Gonzalo along treatment

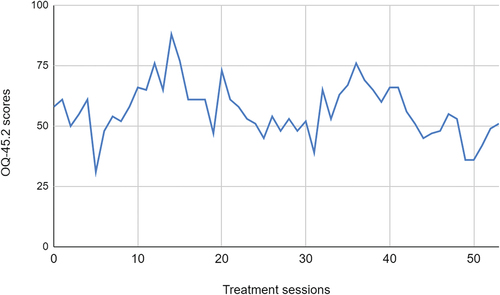

Previous psychometric studies in our context for the OQ.45.2 (Fernández-Álvarez et al., Citation2005) established a cutoff score of 50 between clinical and non-clinical samples, as well as a minimum decrease of 16 points to reach clinically significant improvement. Gonzalo started the treatment with an overall OQ.45.2 score of 58 and ended up with a total score of 51. This cannot be considered a true improvement. However, his scores were close to the cutoff of 50. He also showed several fluctuations of clinical severity during treatment, with the lowest score of 31 in session 5, and the highest score of 88 in session 14. To better illustrate the progress of the case and its general outcome, illustrates the trajectory of OQ-45-2 overall scores of Gonzalo during the whole treatment of 54 sessions. From a clinical point of view, this statistical information may also be complemented with the reasons for therapy termination stated when we described the treatment in the methods section.

OPD-2 foci identified in Gonzalo to assess structural change during treatment

Following OPD-2 guidelines, raters established one relational focus, two conflict foci and two structure foci for Gonzalo.

In terms of the relational focus, raters considered that the patient consciously perceived himself demanding spaces of freedom and autonomy and/or neglecting others in his relationships. Not entirely consciously, however, Gonzalo tended to reject all blame, lose himself and become confused when affection was shown, and not set limits and allow too much closeness. This configured a dysfunctional repetitive pattern that induced in his partners a combination of reproach, submissiveness, and withdrawal. Completing the relational circuit, this generated in Gonzalo a disappointing perception of his partners, in which they granted too much freedom or intruded, in attitudes felt by the patient as too emotionally close. It was considered that this dysfunctional relational pattern should be worked on in treatment to address the patient’s relational problems and generate the possibility of new forms of interpersonal relationships.

In terms of the conflict foci, the raters considered two active conflicts in the case, according to the typology offered by the OPD-2 manual. On the one hand, they considered a conflict between the desires for care and protection versus the tendency to emotional self-sufficiency. On the other hand, an oedipal conflict was considered for Gonzalo, understood by the OPD-2 as a conflict in the patient in terms of valuing himself as a man in relation to women. The combination of both conflicts resulted in the patient’s chronic difficulties to open himself up emotionally in a relationship, as well as in a tendency to infidelity as a pattern, since the patient needed to sustain his valuation as a man by means of permanent amorous conquest behaviors.

Finally, in terms of the structural functioning foci, the raters coded that Gonzalo needed to work on impulse regulation and the ability to bond and detach. summarizes the identified OPD-2 foci.

For each described focus in , structural change was then assessed during treatment by means of HSCS scores (see measures and procedures). As mentioned above, we performed data analyses considering the HSCS scores of the relational focus (HSCS Relation), the average scores of the two conflict foci (HSCS Conflict) and the average scores of the two structure foci (HSCS Structure), respectively.

Predictive effects found for clinical severity and foci’s structural change

Before going to the results of the statistical analysis, it is important to highlight that they show a systematic temporal precedence of certain variations in relation to others, throughout the complete treatment, both considering clinical severity (OQ.45.2’s scores) and therapeutic foci structural change (HSCS’s scores). In other words, we did not estimate changes from a specific session to the next, but sequences of change that took place, systematically, along the whole process of 54 sessions. In this regard, we will show which measures’ score variations were predictors of which dependent variables, within the time-series analysis performed that comprised the 54 sessions of treatment. This was in line with our exploratory interest in understanding mechanisms of change in focused psychodynamic therapy. The results of the complete statistical analyses are summarized in .

Table 3. Multivariate vector autoregressive models performed (VAR, CitationPfaff, Citation2008)

Considering the complete analysis shown in , we organized the results section following the two hypotheses of the study. After reporting statistical data, we also include narrative vignettes developed by raters that give a more detailed contextualization of the HSCS scores rated in each session, and a clearer understanding of the HSCS increases and decreases observed during treatment, both for relation, conflict and structure foci. By means of such vignettes, we intend to picture examples of how structural change occurred during Gonzalo’s therapy (see ).

Table 4. HSCS relation scores’ increase from one session to the next with narrative vignettes developed by raters

Table 5. HSCS conflict scores’ decrease from one session to the next with narrative vignettes developed by raters

Table 6. HSCS conflict scores’ increase from one session to the next with narrative vignettes developed by raters

Table 7. HSCS structure scores’ increase from one session to the next with narrative vignettes developed by raters

Structural change and clinical severity (hypothesis 1)

Our first hypothesis was that greater structural change (higher HSCS’s scores) would predict less clinical severity along treatment (lower OQ-45.2’s scores). In contrast to this hypothesis, we observed that greater structural change for the relational focus in the previous session (time-1) predicted greater clinical severity in the next session (time). This means that patient’s improvement in the elaboration of his dysfunctional relational patterns was associated with an increase in clinical severity in the following session. Statistically, as shown in , an increase of 1 unit on the HSCS scale for the Relation focus in the previous session, predicted an increase of 1.88 units on the OQ-45.2 questionnaire in the next session (β = 1.88, SE = 1.12, t(48) = 1.68, p = 0.10). This data implied a systematic temporal precedence of an increase in HSCS relation’s scores (see an example in ) over an increase in OQ-45-2’s scores, along the complete treatment of Gonzalo (54 sessions). Although the results only approached significance (p < .10), we decided to present them, given the exploratory nature of this study and their clinical implications.

Structural change for relation, conflict and structure foci (hypothesis 2)

The second hypothesis of this study was that greater structural change for a certain focus (relation, conflict or structure as operationalized by HSCS’s scores) in the previous session (time-1) would predict greater structural change for the same focus (relation, conflict or structure) in the next session (time).

No predictive effects for the same focus’ structural change, neither for relation, conflict nor structure foci, were detected. However, we verified the predictive effects of structural change in certain foci on others (see ).

Data analysis confirmed that greater structural change in the relational focus in the previous session (time-1) predicted less structural change in conflict foci in the next session (time). This result entailed that patient’s improvement in the elaboration of relational dysfunctional patterns (see an example in ) preceded less patient’s improvement in the elaboration of intrapsychic conflicts (see an example in ). Statistically, we can see in that an increase of 1 unit on the HSCS scale in the previous session for relation focus significantly predicted a decrease of 0.26 units on the HSCS scale in the next session for conflict foci (β=-0.26, SE = 0.11, t(48) = 2.36, p = 0.02). This data implied a systematic temporal precedence of an increase in HSCS Relation’s scores over a decrease in HSCS conflict’s scores, throughout the complete treatment of Gonzalo (54 sessions). In we include an example of an increase in HSCS relation’s scores. In addition, offers an example of a decrease in HSCS conflict’s scores from one session to the next.

On the other hand, we observed that greater structural change in conflict foci during the previous session (time-1) predicted greater structural change for structure foci in the next session (time). This implies that patient’s improvement regarding the elaboration of intrapsychic conflicts in the previous session was significantly related to greater improvement in the elaboration of structural functioning during the next session. In this regard, shows that, statistically, an increase of 1 unit on the HSCS scale in the previous session for conflict foci, significantly predicted an increase of 0.34 units on the HSCS scale in the next session for structure foci (β = 0.34, SE = 0.17, t(48) = 2.06, p = 0.05). These results showed a systematic temporal precedence of an increase in HSCS conflict’s scores (see an example in ) over an increase in HSCS structure’s scores (see an example in ), along the complete treatment of Gonzalo (54 sessions).

Discussion

By means of a time-series analysis, this study explored therapeutic foci’s structural change and its association with patient’s clinical severity, in a single-case receiving long-term focused psychodynamic therapy (54 therapy sessions). In this sense, we conducted a systematic single-case study to capture in-session therapy process that improves our knowledge about mechanisms of change in psychodynamic therapy.

Results showed three predictive effects of foci’s structural change along the complete treatment: (1) greater structural change in the relational focus predicted greater clinical severity, (2) greater structural change in the relational focus preceded less structural change in conflict foci, and (3) greater structural change in conflict foci was associated with greater structural change in structure foci. In what follows, we discuss each of these findings.

Structural change in relational focus and clinical severity

Time-series analysis indicated that greater structural change in relational focus predicted greater clinical severity, systematically, along the whole treatment. Although this result contrasted with our first hypothesis, we can argue, in line with previous research (Barber & Sharpless, Citation2015; Barber et al., Citation2013) that provides preliminary evidence for different change dimensions taking place during psychodynamic therapy, namely: clinical severity and elaboration of dysfunctional relational patterns.

In this regard, one possible explanation for this finding is the occurrence of a long-term improvement in the patients’ clinical severity preceded by a short-term deterioration after relational focus structural change. The trajectory of the OQ.45.2 scores shown in supports this assumption, in that Gonzalo had several fluctuations in his scores before ending treatment with less clinical severity. Likewise, the results of the time-series analysis allow us to understand such fluctuations as a function of relational focus’s structural change, during the whole treatment.

We can argue that dysfunctional relational patterns were especially relevant for the case analyzed. Gonzalo sought therapy mainly because of such difficulties, as we detail in patient’s clinical context (see methods section) and in . This would explain why the insight of Gonzalo about his relational dysfunctional patterns (greater structural change in relation focus) increased his clinical severity in the short run. He might have felt worse because he was clinically improving (gaining insight and working through his relational problems). In fact, the strategy by which we assessed structural change in the present study (HSCS), explicitly considers that patients may reach a state of confusion and deterioration before achieving greater levels of structural change, as described in . Also, as Hayes et al. Citation(2007) pointed out, there are no strictly linear changes along the psychotherapy process. Our results support this statement. Given the exploratory nature of our study, however, these trends need further replication efforts.

Lastly, we hope to contribute with our findings to the understanding of how common and specific factors that lead to change interact within psychodynamic approaches. Structural change is a dimension specifically related to psychodynamic theory and practice, while clinical severity could be understood as a transtheoretical aspect of change. Moreover, the sequences observed between structural change in relational focus and clinical severity are consistent with other therapeutic approaches’ rationale, such as the metacognitive interpersonal model developed by Dimaggio et al. Citation(2015). This kind of convergencies highlights the possibilities of research focused on integrative models of psychotherapy (Montesano & Scherb, Citation2023).

Different sequences of structural change

In contrast to our hypothesis 2, no predictive effects for the same focus’ structural change, neither for relation, conflict nor structure foci, were detected. However, the data verified different sequences of structural change along the entire treatment. First, greater structural change in the relational focus was associated with less structural change in conflict foci. Second, greater structural change in conflict foci preceded greater structural change in structure foci.

An interplay of relation and conflict foci during treatment?

If greater work in relational patterns was followed by less work in conflicts, then we can argue that Gonzalo elaborated on relation and conflict alternately. It is relevant to note that these trends were systematically present along the complete treatment. If we put results in the context of the time-series analysis performed, we can understand such trends as potential intermediate steps of change. In other words, this data does not imply that Gonzalo worsened or improved in terms of relation or conflict foci at the end of treatment. Instead, they show that less structural change for conflict foci was systematically preceded by greater structural change in relational patterns, indicating a possible sequence of change in psychodynamic approaches.

Considering the specific psychodynamic foci established for the case (see ), results could indicate that the more Gonzalo dealt with his dysfunctional relational patterns during a given session (as shown in ), the more difficult it was for him to analyze his conflicts with emotional distance and his role as a man during the next therapeutic encounter (as shown in ). This information might indicate that Gonzalo had to recover himself after working through relational patterns and probably was more defensive with respect to his intrapsychic conflicts. This line of discussion is also consistent with the increase observed in clinical severity after relational focus’ structural change during the whole process.

Insight in conflict’s improved structural functioning?

Greater change in conflict foci predicted greater change in patient’s structural functioning. We can speculate about Gonzalo working on his conflicts first to work better on his structural functioning, next. Once again, here, the results do not indicate an overall improvement or deterioration in structural change for Gonzalo, neither in terms of conflict nor structure foci. They suggest, however, that when the patient could elaborate on his conflicts, this prepared him better for dealing with his structural vulnerabilities.

In terms of conflict and structure foci proposed by the raters, as shown in , we can further elaborate on these results. A greater therapeutic work on Gonzalo’s conflict foci, related to his need for care versus self-sufficiency and his role as a man, would be consistent with a better regulation of impulses and a better ability to bond and detach, both structure foci selected for the case. Results, then, could be suggesting that the more Gonzalo elaborated on his conflicts (as the example shown in ), the more he could improve in his structure difficulties (as describes).

We believe this is the main contribution of time-series single-case research, given that the results can be understood in terms of temporal sequences of change along a complete treatment. Nevertheless, we are aware of the exploratory nature of our design, and the need to complement our results with evidence gathered in studies using a larger sample, as we propose for future directions.

Implications for psychodynamic practice-oriented research

One general conclusion regarding these data is the usefulness of OPD-2’s and HSCS’s criteria to operationalize the construct of structural change. This accuracy of such criteria is consistent with previous research (Dagnino et al., Citation2014; Grande et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Juan et al., Citation2020). In addition, the results of the present study indicate that relational patterns, intrapsychic conflicts and structural functioning are not only specific features of patient’s improvement or deterioration but also change dimensions with potential predictive effects on each other. We note this evidence particularly relevant to identify change mechanisms in psychodynamic approaches.

Given the practice-oriented research nature of the present study, we also state some possible recommendations for psychodynamic practice.

We gathered preliminary evidence of certain trajectories of change that occurred during a focused psychodynamic therapy. Such trajectories could suggest that (1) if we work on clients’ relational dysfunctional patterns, their clinical severity could temporarily deteriorate, (2) certain clients may need to work alternately on their relational dysfunctional patterns and their conflicts, and (3) to work on structural functioning, we should focus on conflicts first to enhance clients’ structural changes, at least in cases in which the work on conflicts is viable. Multiple replication efforts of this preliminary evidence are needed to confirm or refute these clinical hypotheses.

Limitations

Neither the control of intervening variables nor the absence of spurious relationships among studied variables can be ensured because of the methodological design of the study. Nevertheless, some authors have suggested that assessing process measures continuously from early stages of treatment, as was done in this study, reduces the possibility of intervening variables to impact both change and therapeutic process components (Roussos et al., Citation2016; Strunk et al., Citation2010). The therapist-researcher double role employed was in line with the practice-oriented research focus of the study, but it could also be a potential source of biases. We tried to control for such biases keeping therapist blind to raters’ coding and using raters’ psychodynamic profile to assess structural change, instead of therapist’s perspective on the patient. At the same time, we must accept that not including the clinical judgment of the treating therapist can also be a weakness of the design itself. In future studies, we should complement the results observed in the present work considering therapist’s case formulation and ratings. As a starting point to this research agenda, in previous works (Juan et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), the same raters and therapist participating in this study have coded the same clinical material and reached strong convergences among perspectives.

Finally, as in every single-case research, the observed data may be due to case’s and therapeutic dyad’s specificities. Future research is needed to replicate the findings with different designs. Moreover, the psychodynamic nature of the single case studied may imply that the results observed only apply within this theoretical model. As we state in future directions, new research is needed to replicate our findings analyzing cases conducted with other therapeutic orientations.

Future directions

With the present research, we studied sequences of structural change and clinical severity, trying to better understand the mechanisms at work in psychodynamic therapy. On the one hand, future efforts could replicate systematic single-case studies involving other treatments’ modalities apart from psychodynamic. This would be relevant to better understand the transtheoretical mechanisms of change at play. On the other hand, future research should improve the field of psychodynamic therapy as an empirically based method of treatment, strengthening psychodynamic theories and training with the support of research. We also highlight the future possibilities of systematic tools, such as OPD-2 for psychodynamic practice-oriented research. The present study exemplified how OPD-2’s criteria can describe key aspects of a psychodynamic treatment and operationalize core change dimensions postulated by psychodynamic theory. This may constitute a platform for future research lines (see Juan & Gómez Penedo, Citation2020). New studies are needed to deepen the use of OPD-2 as a measure of structural change and explore the interaction with reflective functioning, symptomatic improvement, and clinical severity. In this research agenda, future projects should complement single-case designs with cross-sectional assessments, combining ideographic and nomothetic strategies. This line of study will aim to match within and between subjects’ effects when analyzing change mechanisms in psychodynamic therapy.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was provided by Universidad de Buenos Aires, School of Psychology’s ethics research board.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the students of our research team Gastón Giunta, Nahuel Lavanga and Javier Salgado for their collaboration in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The research data associated with this study can eventually be requested to the Research Team in Clinical Psychology (EIPSI), Buenos Aires, Argentina (https://equipoeipsi.com/).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barber, J. P., Muran, J. C., McCarthy, K. S., & Keefe, R. J. (2013). Research on psychodynamic therapies. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 443–27). John Wiley & Sons.

- Barber, J., & Sharpless, B. (2015). On the future of psychodynamic therapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 25(3), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.996624

- Boswell, J. F., Anderson, L. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). An idiographic analysis of change processes in the unified transdiagnostic treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1060–1071. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037403

- Crits-Christoph, P., Connoly Gibblons, M. B., & Mukherjee, D. (2013). Psychotherapy process outcome research. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 298–340). John Wiley & Sons.

- Dagnino, P., de la Parra, G., Jaramillo, A., Crempien, C., Padilla, O., Gómez-Barris, E., & Rodríguez, S. (2014). El Devenir del cambio: Cómo es y hacia dónde se dirige [the evolution of change: What it looks like and where it is headed]. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 23(3), 23–40.

- Delgadillo, J., & Lutz, W. (2020). A development pathway towards precision mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1048

- Diamond, D., Clarkin, J. F., Levy, K. N., Meehan, K. B., Cain, N. M., Yeomans, F. E., & Kernberg, O. F. (2014). Change in attachment and reflective function in borderline patients with and without comorbid narcissistic personality disorder in transference focused psychotherapy. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 50(1–2), 175–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.2014.880316

- Diener, M., Hilsenroth, M., & Weinberger, J. (2007). Therapist affect focus and patient outcomes in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.936

- Dimaggio, G., Montano, A., Popolo, R., & Salvatore, G. (2015). Metacognitive interpersonal therapy for personality disorders: A treatment manual. Routledge.

- Feixas, G., & Miró, M. T. (1993). Aproximaciones a la psicoterapia. Una introducción a los tratamientos psicológicos [Approaches to psychotherapy. An introduction to psychological treatments]. Paidós.

- Fernández-Álvarez, H., Hirsh, H., Maristany, M., & Torrente, F. (2005). Propiedades psicométricas del OQ-45.2 en la Argentina: un estudio piloto [Psychometric properties of the OQ-45.2 in Argentina: a pilot study]. Paper presented at IV Congreso Mundial de Psicoterapia, Buenos Aires.

- Freud, S. (1926). Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. Standard Edition, 20(1), 77–174.

- Gallagher, M. W., Long, L. J., Richardson, A., D’Souza, J., Boswell, J. F., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2020). Examining hope as a transdiagnostic mechanism of change across anxiety disorders and CBT treatment protocols. Behavior Therapy, 51(1), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.001

- Gómez Penedo, J. M., Juan, S., Manubens, R. T., & Roussos, A. (2017). El estudio del cambio en psicoterapia: desafíos conceptuales y problemas de investigación empírica [The study of change in psychotherapy: conceptual challenges and empirical research problems]. Anuario de Investigaciones, XXIV(Tomo I), 15–24. ISSN 0329-5885, Ediciones de la Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires. In:. http://www.psi.uba.ar/investigaciones/revistas/anuario/trabajos_completos/24/gomez_penedo.pdf

- Gómez Penedo, J. M., & Roussos, A. (2012). ¿Cómo sabemos si nuestros pacientes mejoran? Criterios para la significancia clínica en psicoterapia: Un debate que se renueva [How do we know if our patients are improving? Criteria for clinical significance in psychotherapy: A renewed debate]. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 21(2), 173–189. http://repositorio.ub.edu.ar/handle/123456789/2756

- Gottdiener, W. H., & Suh, J. J. (2012). Expanding the single-case study: A proposed psychoanalytic research program. The Psychoanalytic Review, 99(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1521/prev.2012.99.1.81

- Grande, T., Dilg, R., Jakobsen, T., Keller, W., Krawietz, B., Langer, M., Oberbracht, C., Stehle, S., Stennes, M., & Rudolf, G. (2009). Structural change as a predictor of long-term follow-up outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 19(3), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300902914147

- Grande, T., Keller, W., & Rudolf, G. (2012). What happens after treatment: Can structural change be a predictor of long-term outcome? In R. A. Levy, J. S. Ablon, & H. Kächele (Eds.), Psychodynamic psychotherapy research. Evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence (pp. 169–188). Humana Press, Springer.

- Grande, T., Rudolf, G., Oberbracht, C., & Jakobsen, T. (2001). Therapeutische Veränderungen jenseits der Symptomatik: Wirkungen stationärer Psychotherapie im Licht der Heidelberger Umstrukturierungsskala [Therapeutic changes beyond the Symptoms-effects of inpatient treatment in the view of the Heidelberg Structural Change Scale. Zeitschrift Für Psychosomatische Medizin Und Psychotherapie, 47(3), 213–233.

- Hayes, A. M., Laurenceau, J. P., Feldman, G., Strauss, J. L., & Cardaciotto, L. (2007). Change is not always linear: The study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(6), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008

- Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000097254001

- Hofmann, S. G., Curtiss, J. E., & Hayes, S. C. (2020). Beyond linear mediation: Toward a dynamic network approach to study treatment processes. Clinical Psychology Review, 76, 101824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101824

- Juan, S., & Gómez Penedo, J. M. (2020). Introduction to special section. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 22(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5935/2318-0404.20200018

- Juan, S., Gómez Penedo, M., & Roussos, A. (2017). Proyecto de investigación: Foco terapéutico y mecanismos de cambio en un caso de único de psicoterapia psicoanalítica [Research project: Therapeutic focus and mechanisms of change in a single case of psychoanalytic psychotherapy]. Diagnosis, 14(1). https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/83365

- Juan, S., Manubens, R., Chávez, I., López Fediuk, L., Roussos, A., & Gómez-Penedo, J. M. (2019). Focos Terapéuticos en un Caso de Abandono Temprano: Perspectivas del Terapeuta y de Jueces Externos [Therapeutic Foci in an early dropout case: therapist’s and external judges’ perspectives]. Investigaciones en Psicología, 24(2), 33–42. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/170596

- Juan, S., Manubens, R., López Fediuk, L., & Gómez Penedo, J. M. (2020). Psychodynamic profile in an early dropout case: Comparing therapist’s and external judges’ perspectives. Revista Brasileira de Psicoterapia, 22(3), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.5935/2318-0404.20200019

- Juan, S., Manubens, R., Muiños, R., & Gómez Penedo, J. M. (2021, June 23-26). Mechanisms of change in focused psychodynamic therapy: A single case’s time-series analysis [paper in a panel]. 52th Annual Meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Heidelberg. https://www.sprconference.com/

- Juan, S., Muiños, R., Dzugala, Z., Lavanga, N., & Gómez Penedo, J. M. (2022). The impact of psychodynamic case formulation and therapist’s adherence on outcome: A single case’s time-series analysis. Paper in a panel presented at the 53th Annual Meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Denver.

- Kächele, H. (2010). Distinguishing psychoanalysis from psychotherapy. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 91(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2009.00232.x

- Kächele, H., Schachter, J., & Thöma, H. (2009). From psychoanalytic narrative to empirical single-case research: Implications for psychoanalytic practice. Routledge.

- Lambert, M. J. (2013). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 169–218). John Wiley & Sons.

- Lambert, M. J., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N., Vermeersch, D. A., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). The reliability and validity of the outcome questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199612)3:4<249:AID-CPP106>3.0.CO;2-S

- Leuzinger-Bohleber, M., Kaufhold, J., Kallenbach, L., Negele, A., Ernst, M., Keller, W., Fiedler, G., Hautzinger, M., Bahrke, U., & Beutel, M. (2019). How to measure sustained psychic transformations in long-term treatments of chronically depressed patients: Symptomatic and structural changes in the LAC depression study of the outcome of cognitive-behavioural and psychoanalytic long-term treatments. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 100(1), 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2018.1533377

- Levy, K. N., Clarkin, J. F., Yeomans, F. E., Scott, L. N., Wasserman, R. H., & Kernberg, O. F. (2006). The mechanisms of change in the treatment of borderline personality disorder with transference focused psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20239

- Luborsky, L. (1984). Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: A manual of supportive-expressive treatment. Basic Books.

- Luyten, P., Lowyck, B., & Blatt, S. J. (2017). Mechanisms of change through the lens of two-polarities models of personality development: State of the art and new directions. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 37(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2017.1285187

- Montesano, A., & Scherb, E. (2023). Teamwork for complex clinical situations in psychotherapy: Introduction to the issue. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(6), 1515–1520. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23518

- OPD Task Force (eds). (2007). Operationalized psychodynamic Diagnosis: OPD-2. Manual of Diagnosis and treatment planning. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

- Pfaff, B. (2008). VAR, SVAR and SVEC models: Implementation within R package vars. Journal of Statistical Software, 27(4). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v027.i04

- Rapaport, D. (1960). The structure of psychoanalytic theory: A systemizing attempt. International Universities Press.

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Röst, D., & De la, P. (2009). Manual traducido al español de la Escala de Cambio Estructural de Heidelberg (HSCS) [Manual translated into Spanish of the Heidelberg Structural Change Scale (HSCS)]. Unpublished manuscript, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

- Roussos, A. J., Gomez Penedo, J. M., & Muiños, R. (2016). A time-series analysis of therapeutic alliance, interventions, and client’s clinical status in an evidence-based single-case study: Evidence for establishing change mechanisms in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 28(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1174346

- Rudolf, G. (2006 [2017]). Strukturbezogene Psychotherapie. Leitfaden zur psychodynamischen Therapie struktureller Störungen. Aufl. Stuttgart: Schattauer; Versión en castellano: Psicoterapia orientada a la estructura psíquica. Edited by Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana, Chair of traslation: Dr. Álvaro Romero Pimienta. Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana.

- Rudolf, G., Grande, T., & Oberbracht, C. (2000). Die Heidelberger Umstrukturierungsskala. Ein Modell der Veränderung in psychoanalytischen Therapien und seine Operationalisierung in einer Schätzskala [The Heidelberg Structural Change Scale. A Model of Change in Psychoanalytic Therapies and its Operationalization in an Estimation Scale]. En Psychotherapeut, 45(4), 237–246. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/PL00006720

- Rudolf, G., Grande, T., & Oberbracht, C. (2001) Die Heidelberger Umstrukturierungsskala. Manual. Materialien der Praxisstudie Analytische Langzeittherapie [Heidelberg Structural Change Scale. Manual. Materials of the practice study Analytical Long-Term Therapy] [ Unpublished manuscript], Heidelberg University.

- Sifneos, P. E. (1987). Short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Evaluation and technique. Plenum Publishing Corporation.

- Silberschatz, G. (2017). Improving the yield of psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1076202

- Stiles, W. B., Elliott, R., Llewelyn, S. P., Firth-Cozens, J. A., Margison, F. R., Shapiro, D. A., & Hardy, G. (1990). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.27.3.411

- Strunk, D. R., Brotman, M. A., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2010). The process of change in cognitive therapy for depression: Predictors of early inter-session symptom gains. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(7), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.011

- Summers, R., & Barber, J. (2010). Psychodynamic therapy: A guide to evidence-based practice. Guilford.

- Summers, R., Xuan, Y., & Tavakoli, D. N. (2013). Teaching focus in psychotherapy: A training essential. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2013.41.1.91

- Thoma, H., & Kachele, H. (1985 [1989]). TeoríA y práctica del psicoanálisis. I fundamentos [psychoanalytic theory and practice. I foundations]. Editorial Herder S.A.

- Tillman, J. G., Clemence, A. J., & Stevens, J. L. (2011). Mixed methods research design for pragmatic psychoanalytic studies. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 59(5), 1023–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065111418650

- von Bergen, A., & de la Parra, G. (2002). OQ-45.2, Cuestionario para evaluación de resultados y evolución en psicoterapia: Adaptación, validación e indicaciones para su aplicación e interpretación. [The OQ-45.2, Questionnaire for Outcome and Assessment in Psychotherapy: Adaptation, validation and indications for its application and interpretation]. Terapia Psicológica, 20(2), 161–176.

- Zilcha-Mano, S., & Barber, J. P. (2014). Learning from well-trained and experienced dynamic psychotherapists: Research on the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy and its mechanisms of change. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 50(1–2), 58–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.2014.880309