ABSTRACT

This study examined the association between shyness and problematic internet use among adolescents and young adults. A systematic search of relevant publications in English published before September 2022 yielded 35 studies in total (n = 26,708 individuals), which were systematically reviewed. Among them, 27 studies were included in the meta-analyses. Results from random-effects models indicated that shyness was positively associated with problematic internet use (μ̂ = 0.2753; 95% CI: 0.2409 to 0.3096). Moreover, results from the moderation analyses indicated that the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use was moderated by age group. Specifically, the effect size of shyness on problematic internet use seemed to be larger for young adults than for adolescents (Z = -2.25, p < .001). Our findings indicated that shy people, particularly shy young adults, are more likely to have problematic internet use, which provided useful information for future intervention.

With the rapid advancement of technology, the internet has become an essential part of our daily lives (Gibson & Trnka, Citation2020). Indeed, the internet’s usefulness in education, leisure, and information transmission has posed significant advances for society. For example, it has revolutionized how we learn and made education more accessible. It has also fostered worldwide connections through instant communication, and has democratized knowledge access by providing a wealth of information at users’ fingertips (Gibson & Trnka, Citation2020). However, this widespread adoption of the internet has also facilitated the emergence of problematic internet use in children and adults, with an estimated 2% prevalence in the global adult population (J Kuss et al., Citation2014; Kuss & Lopez-Fernandez, Citation2016; Poli, Citation2017).

Problematic internet use, often referred to as internet addiction, is a compulsive and harmful pattern of internet use with negative consequences that disrupt daily life (Musetti & Corsano, Citation2018). Problematic internet use is a multifaceted phenomenon that can manifest in various forms, including the use of smartphones, laptops, and other internet-enabled devices. It encompasses a range of problematic online behaviors, such as excessive social media use, gaming, gambling, binge-watching television, and impulsive online shopping, among others, as identified by research studies (Fineberg et al., Citation2018). While some researchers advocate that problematic internet use merits classification as a new or emerging psychiatric disorder in its own right (i.e., a true behavioural addiction to the internet or internet related activities), others propose that certain individuals merely have a problematic use of the internet in relation to specific online activities, such as gambling, email, or pornography (Yellowlees & Marks, Citation2007). That said, despite the differences between these schools of thought, both refer to patterns of internet use that are excessive and disruptive to daily life. Thus, to ensure a comprehensive review of the work in this area, this paper uses the terms interchangeably.

Despite the numerous positive benefits of using the internet (e.g., connecting with others; Nagata et al., Citation2020, access to information; Selkie et al., Citation2020, navigation; Macedo‐Rouet et al., Citation2019, entertainment; Nhamo et al., Citation2020), problematic internet use represents a disruptive and maladaptive pattern of internet use which results in negative consequences (Moretta & Buodo, Citation2020). Indeed, problematic internet use has been linked to adjustment issues, such as academic failures, physical problems, and internalizing problems (Geng et al., Citation2018; Hughes & Burke, Citation2018). For example, Morita et al. Citation(2022) found that problematic internet use was associated with depression and hyperactivity symptoms among adolescents. Additionally, in a recent review, Gioia et al. Citation(2021) found that problematic internet use had a strong association with emotion dysregulation. With the rising adoption of technology, over the last two decades, problematic internet use has been increasing worldwide (Tsitsika et al., Citation2014). The prevalence of problematic internet use worldwide is around 6% to 9.7% (Burkauskas et al., Citation2022), and varies across regions (e.g., 8.4 % in Chen et al., Citation2021; 21.1% in Turkey; Cam & Top, Citation2020). In general, the prevalence of problematic internet use in Asian countries is higher than that in European countries (J Kuss et al., Citation2014).

Given concerns around increasing rates of internet use, recent work has focused on identifying personality traits associated with problematic internet use (e.g., Seong et al., Citation2019). Notably, shyness has been identified as an important risk factor for internet addiction in many of these studies (Huan et al., Citation2014; Ozturk & Ozmen, Citation2011). Shyness is a personality trait that refers to social anxiety and nervousness accompanied by an increased sensitivity to social evaluation (Coplan et al., Citation2004). Unlike introverts, shy people want to participate in social interactions and make impressions on others (i.e., social approach motivation). However, shyness is theorized to cause nervousness, worry, and anxiety during such direct interactions, along with doubts about impression management, which can lead to a tendency to avoid social situations (i.e., social avoidance motivation) (Asendorpf, Citation1990; Coplan et al., Citation2004). As a result, shyness has been linked with a variety of maladaptive adjustment outcomes across the lifespan, including internalizing problems (Coplan et al., Citation2014; Katz et al., Citation2011), social difficulties (e.g., Sette et al., Citation2019), and behavioural problems (Xu et al., Citation2021). Indeed, individuals higher in shyness are more likely to face peer difficulties since they are often uncomfortable when interacting with others—which can lead them to avoid difficult or awkward conversations (Barry et al., Citation2013). For example, researchers have found that shy individuals tend to be less satisfied with, and have more difficulties maintaining, their romantic relationships (Baker & McNulty, Citation2010). Furthermore, it’s worth noting that shy individuals may be at a higher risk of developing addiction, including internet addiction (Ang et al., Citation2018; Tian et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, it is perhaps not surprising that many interventions (e.g., social skills training, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness therapy) are designed to assist such shy individuals (Schneider & Byrne, Citation1985; Tarkhan, Citation2016). For example, Coplan et al. Citation(2010) used social skills training to help extremely shy children decrease socially wary behaviours and increase social and socially competent behaviours.

Problematic internet use and shyness

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated a positive and significant link between shyness and problematic internet use across various cultural contexts (Ang et al., Citation2018; Ebeling-Witte et al., Citation2007; Tian et al., Citation2017). Since individuals higher in shyness tend to feel more anxious, nervous, and uncomfortable during social interactions, they may be drawn to online interactions and end up spending more time on social media (Ang et al., Citation2018; Ebeling-Witte et al., Citation2007; Tian et al., Citation2017), which places them at increased risk for problematic internet use. Researchers have proposed several reasons for why shy individuals may be more prone to problematic internet use. First, given that feeling nervous and anxious during peer interactions is a key characteristic of shyness—making face-to-face interactions uncomfortable—many shy individuals may choose to avoid in-person social interactions (McCabe, Citation2015). However, even shy individuals need social interactions to satisfy their fundamental and intrinsic need for social connection and support seeking (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Thus, many shy individuals may seek alternative ways to interact with others (e.g., interacting online; Porter & Chambless, Citation2017). Indeed, based on the Social Compensation Model, individuals experiencing shyness may satisfy their need for social resources and support with internet activities like social media use or online gaming (Sioni et al., Citation2017). However, this pattern of going online to satisfy social needs can be difficult to stop (Tian et al., Citation2017), and may contribute to problematic internet use. For example, Tian et al. Citation(2021) found that in China, shy students experienced more loneliness and this, in turn, led to an increase in their problematic internet use.

There are two additional factors which may lead shy individuals to prefer online interaction, and thereby increase their risk of developing problematic internet use (chimmenti & Caretti, CitationS2010; Settanni et al., Citation2018). First, shy individuals tend to be apprehensive about being evaluated in real-life social activities, and especially fear disapproval about their inner thoughts and emotions (Katz et al., Citation2011). According to the Anonymity, Convenience, and Escape from reality theory (ACE theory), the Internet’s traits of anonymity and escape from reality likely decreases the possibility of identification by others and make shy people feel safe to share things they would not share offline (Schimmenti & Caretti, Citation2010). As such, the sense of anonymity experienced online may increase the possibility of online interactions for shy individuals (Jin et al., Citation2017), which could in turn, increase their risk of problematic internet use. Second, shy individuals may prefer interacting on the internet for physiological reasons. More specifically, online communication allows shy people to connect with others while reducing potentially overwhelming auditory and visual cues from others (Settanni et al., Citation2018; Stritzke et al., Citation2004) and to avoid the physiological symptoms (e.g., sweating, blushing, racing heart) shy people tend to experience during face-to-face interactions (Nikolić et al., Citation2016).

Overall, most studies have found that shy people spend more time using social media, have positive attitudes toward it, and are drawn to it as a way to communicate (Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Baker & Oswald, Citation2010; Hong et al., Citation2019). For example, Hong et al. Citation(2019) found that shyness was strongly associated with problematic mobile phone use among Chinese adolescents. However, some studies have found no significant link between shyness and problematic internet use. For example, Spensieri et al. Citation(2019), found that shyness did not predict problematic internet use among Italian children. Given these conflicting findings, there is a dire need for a systematic review and meta-analysis in this area to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use, as well as the factors that moderate or mediate this relationship.

The present study

As the internet becomes an increasingly important part of daily life, there is growing concern around the emergence of problematic internet use in children and adults. Given that shy people may be especially vulnerable to problematic internet use it is essential that the association between shyness and problematic internet use be empirically understood. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has yet to be a comprehensive review on this topic. Therefore, in the present study we employ a systematic review and meta-analysis of shyness and problematic internet use. The findings from this study can serve as a foundation for knowledge dissemination, and guide professionals in identifying the unique needs of shy individuals and understanding the underlying mechanism in the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use.

Meta-analytic procedures provided a test of the overall effect of shyness on problematic internet use and a homogeneity test was used to test the similarity of the effect sizes across studies. When the overall effect is not from a homogeneous body of research, potential moderators should be tested, to help explain the variability across studies (Sagie & Koslowsky, Citation1993). Thus, two categories of moderators were tested in the present study. The first set of moderators included study-level factors, such as the publication year and study design. The second category of moderators were the sample characteristics, such as the age and country.

Based on findings from the existing literature, we hypothesized that shyness would generally be positively associated with people’s problematic internet use. Moreover, we expected that several factors, such as research design (i.e., cross-sectional design vs. longitudinal design), age (adolescents vs. young adults), publication year (recent studies vs. older studies) and country (Western countries vs. non-Western countries) may moderate the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use.

Methods

Design

In the present study we employ a systematic review and meta-analysis of shyness and problematic internet use. A systematic review is a comprehensive and structured approach to reviewing and synthesizing existing research on a specific topic or research question (Perestelo-Pérez, Citation2013). We chose to conduct a systematic review to ensure an unbiased and thorough evaluation of the association between shyness and problematic internet use by systematically analyzing a wide range of studies. This method’s transparency, standardized approach, and potential for meta-analysis enhances the reliability and generalizability of the study’s findings compared to other review methods (Hanley & Cutts, 2103). We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as a guideline for conducting both the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Operational definitions

In this study, shyness was operationally defined as a motivational aspect that includes both approach and avoidance tendencies towards social situations, or a withdrawal and anxiety in social environments (Coplan et al., Citation2004). Problematic internet use was operationally defined as a pattern of excessive or compulsive internet use (including smartphone, game, and social media use) that has negative consequences in various areas of an individual’s life, such as interpersonal relationships, work or school performance, physical and mental health, and overall well-being (Fineberg et al., Citation2018). We considered all definitions that met the above criteria to be equivalent for the purposes of this study. Moreover, given the heterogeneity in terms used to describe problematic patterns of technology use, in this paper, we use several related terms interchangeably, including problematic internet use, internet addiction, social media addiction, gaming addiction, and smartphone addiction.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) empirical studies, (2) peer-reviewed journal articles, (3) publications before September 2022, (4) publications in English, and (5) reporting the relation between shyness and Internet addiction by using either Pearson’s product-moment coefficients r, or T and F values that could be converted to r values.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: case reports, intervention studies, review articles and meta-analyses, dissertations, and conference papers. Studies with no specific definition for shyness or problematic internet use were also excluded.

Information sources

A comprehensive search was performed in several electronic databases including PubMed, Electronic PsycINFO, PsycARTICLEs, and Web of Science to identify all potentially relevant publications in the English language up until September 2022 (date of first search: NaN Invalid Date , and date of last search: NaN Invalid Date).

Search strategy

The detailed search strategy electronic databases were as follows: (“Internet addiction”[Title/Abstract] OR “problematic Internet use”[Title/Abstract] OR “Internet addiction disorder”[Title/Abstract] OR “pathological Internet use”[Title/Abstract] OR “Internet game addiction”[Title/Abstract] OR “smartphone addiction”[Title/Abstract] OR “problematic smartphone use”[Title/Abstract] OR “smartphone dependency”[Title/Abstract] AND (“shyness”[Title/Abstract] OR “shy”[Title/Abstract] OR “social withdrawal”[Title/Abstract]). Furthermore, a search was also conducted on Google Scholar using the identical strategies outlined above, including the same keywords, and focusing on relevant publications published until September 2022. All searches were conducted for both the first author and the third author.

Study selection procedure

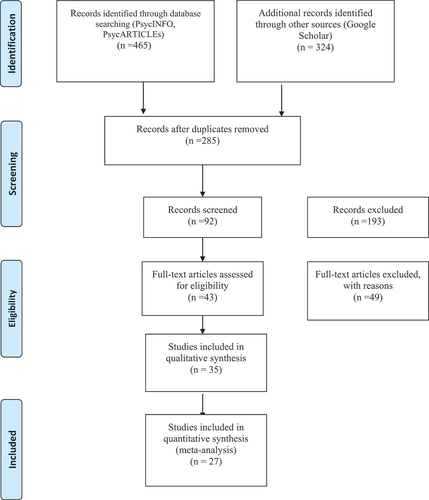

The initial keyword search generated 789 studies (465 from the database: PubMed (243 articles), Electronic PsycINFO (316 articles), PsycARTICLEs (124 articles), Web of Science (123 articles) and Google Scholar (324 articles). After deleting the duplicates and screening the titles, abstracts, and full-text based on the inclusion criteria, 35 studies were selected. Studies were generally excluded for the following reasons: (a) not data-based (77 articles), (b) the measurement of shyness (or other substitute words of shyness) was not in line with the operational definition specified in this review (24 articles), (c) the measurement of problematic internet use was not in accordance with the operational definition as specified in this review (34 articles), (d) did not examine the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use (63 articles), (f) publication was not in English (52 articles). Furthermore, we looked at reference lists to identify additional eligible studies, which resulted in another three studies being located. In total, 35 articles were included in this review (see ). The selection of relevant studies was conducted by the first author and the third author.

Coding variables

We coded all relevant studies using a standardized data extraction tool into which the following study characteristics were entered: author information, publication years, participants characteristics, sample size, gender, study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal design), shyness and Internet addiction measures, and moderators in the relationship between shyness and problematic smartphone use (see ). The coding process was conducted independently by the first author and the third author. The inter-rater reliability yielded a kappa of .90, indicating almost perfect agreement between two researchers (Viera & Garrett, Citation2005). Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion.

Table 1. Summary of 35 studies including in systematic review

Summary measures for the meta-analysis

Of the 35 studies that were selected, 27 were included in the meta-analysis. The remaining eight studies were excluded for the following reasons because only structural coefficients or partial correlations were reported, which were not applicable in computing correlational effect sizes.

The correlation coefficient (r) was used as effect size to compare the 27 different studies. For those studies that only reported standardized beta coefficients (β), β was converted to r using the formula r = 0.98β +0.05λ (Peterson & Brown, Citation2005). To ensure the independence of the effect sizes, if more than one effect size was reported on the same parameter for the same sample group at different time points in longitudinal studies, we only kept one effect size of either the longitudinal correlation or the correlation of data collected at time 1 (whichever had the largest sample size).

Statistical analysis

The R statistical software (R Core Team, Citation2022) and meta package (Balduzzi et al., Citation2019) was used for statistical analysis. The Q statistic and p-value were first calculated to test the assumption of homogeneity in effect sizes (Zintzaras & Ioannidis, Citation2005). That is, the similarity of the effects found in the individual studies was tested to determine whether the variation between studies was greater than would be expected by chance alone. The random effect model was selected to test Q, whereby a significant Q value would imply heterogeneity, and a non-significant Q value would imply homogeneity such that the combined estimates would represent a meaningful description of the set of studies. Additionally, I-squared (I2) was also calculated to test the degree of inconsistency between studies (Migliavaca et al., Citation2022). To assess publication bias, funnel plots were used to display the relationship between the standard error and the effect size. Egger and Begg’s test was used to assess the symmetry of the funnel plots (van Enst et al., Citation2014). Trim and Fill method was employed for estimating the unbiased effect size and the impact of the bias (van Enst et al., Citation2014).

Effects of moderator variables such as the gender of participants, publication year, and different types of intervention were tested by subgroup analysis (Van Houwelingen et al., Citation2002). For moderator analysis, at least three studies at each level were required. Therefore, we categorized each variable into groups to maximize the inclusion of the potential moderators that could satisfy the group size requirement while preserving a meaningful comparison. Consequently, for the age variable, the samples were divided into two age periods: adolescents and youth/adults. For the country variable, the samples were divided into Western countries and non-Western countries. For methodological factors, the research design was categorized as longitudinal design and cross-sectional design. At last, publication years were divided into recent studies (published between 2020–2022) and previous studies (before 2020). The decision to categorize the publication years into two groups, recent studies (2020–2022) and earlier studies (before 2020), was aimed to capture a temporal distinction that reflects the evolving landscape of research in the field of interest. Recent studies tend to incorporate the latest advancements in methodologies, technologies, and conceptual frameworks. By focusing on studies published between 2020 and 2022, the analysis can provide insights into the most current trends and developments in the relationship between internet addiction and shyness. We used random effects models to conduct the moderator analyses.

Results

Systematic review

Description of studies

Among the 35 studies, all of the reviewed studies were conducted after 2004 and 85.7% of them were conducted in the last 10 years. Regarding the research purpose, the majority of the studies focused on investigating the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use and exploring mediating factors (e.g., loneliness, social anxiety, and depression) (n = 15; 42.8%). Most of the studies were cross-sectional (n = 30; 85.7%) and five of them employed a longitudinal design (n = 5; 14.3%) (see ).

Sample

Among the 35 studies, the sample sizes ranged from 88 to 5,215 children (M = 763). The studies were conducted in Western countries (n = 6) and non-Western countries (n = 29). Some studies focused on adolescents (n = 12; 34.3%) and some (n = 17; 65.7%) sampled young adults. Most reviewed studies reported a fairly equal distribution of boys and girls or men and women, with each gender accounting for 42–60% of the participants (n = 33; 94.3%). Only two studies have women representing over 70% (n = 2; 5.7%) of the sample. However, only three studies investigated the role of gender in the relationship between shyness and internet addiction (Tian et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2022), and two studies reported significant results. For example, Tian et al. Citation(2018) found that the relationship between shyness and internet addiction was stronger for men than for women. Similar results were reported by Tian et al. Citation(2019). However, Wang et al. Citation(2022) found that the strength of the association between shyness and Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) symptoms was the same.

Measures of shyness and internet addiction

Among the 35 studies, the Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (Cheek, Citation1983), a self-report measure, was the most popular tool used to assess individuals’ shyness (n = 28; 80%). Three studies used Henderson and Zimbardo Shyness Scale (Henderson & Zimbardo, Citation2002). Two studies used Social Reticence Scale (SRS) which was developed by CitationJones et al. (Citation1986). One study used the Children’s Shyness Questionnaire, which was developed by Crozier Citation(2005), and one study used five items developed by Li (Citation2012).

For measuring problematic internet use, the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) developed by Young (1998) (n = 13; 37.1%), the Internet Addiction Scale by Andreassen et al. Citation(2012) (n = 4; 11.4%), the Problematic Internet Use Scale by Ceyhan et al. Citation(2007) (n = 5; 14.3%), the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS) by Caplan Citation(2010) (n = 4; 11.4%), and the Mobile Phone Addiction Index by Leung Citation(2008) (n = 3; 8.5%) were the most popular tools used. Other measures used included the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS) by Kwon et al. Citation(2013) (n = 2; 5.7%), the MPPUS developed by Bianchi and Phillips Citation(2005) (n = 1; 2.8%), the internet gaming disorder test (IGDT-10) (n = 1; 2.8%), and Online Cognition Scale (n = 1; 2.8%).

Mediating factors

Among the 35 studies included in this review, 14 studies investigated potential mediators of the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Notably, 7 studies found that loneliness played a mediating role in the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use (e.g., Ang et al., Citation2018; Tian et al., Citation2018). For example, Huang et al. (Citation2014) found that shyness was associated with loneliness, and loneliness was then associated with problematic internet use. Tian et al. Citation(2018) further found that loneliness played a bidirectional mediating role in the association between shyness and problematic internet use. Specifically, shyness at time 1 and problematic internet use at time 3 were mediated through increased loneliness at time 2, and problematic internet use at time 1 and shyness at time 3 were mediated through increased loneliness at time 2. Interestingly, Ang et al. Citation(2018) found that the desire to avoid loneliness was partially mediated by the relationship between shyness and internet addiction. Specifically, shy individuals expressed a higher desire to avoid loneliness. This desire was further associated with problematic internet use. Moreover, four studies found mediation roles of psychological disorders (e.g., social anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms) (Huang et al., Citation2014; Gao et al., Citation2018; Hong et al., Citation2019; Spensieri et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, two studies investigating the mediating roles of self-control and self-regulation on the relationship between shyness and internet addiction found that self-control played a partial mediating role and self-regulation played a fully mediating role (Han et al., Citation2017; Yu et al., Citation2019). At last, Chen et al. Citation(2021) found that the association between shyness and internet addiction was partially mediated by basic psychological needs. Furthermore, family cohesion moderated the relationship between shyness and basic psychological needs, as well as the relationship between basic psychological needs and mobile phone dependency. The moderating effects were stronger on high family cohesion individuals than on low family cohesion individuals.

Meta-analysis

Overall effect

Among the 27 studies, an examination of the standardized residuals revealed that one study (study 1) had a value larger than ± 3.1130 and may be a potential outlier in the context of this model. Moreover, Cook’s distances in meta-analysis quantify the influence of individual studies on the overall results by assessing how much the results change when a specific study is excluded (Viechtbauer & Cheung, Citation2010). Therefore, according to Cook’s distances, two studies (study 1 and study 10) could be considered as overly influential. Removing these outliers resulted in a reduction in Q from 311.97 to 189.65, and I2 r from 0.94 to 0.82, suggesting that these studies were affecting the homogeneity of the study set. Therefore, these two studies were removed from further analysis.

A total of k = 25 studies were included in the analysis. The observed Fisher r-to-z transformed correlation coefficients ranged from 0.0792 to 0.4722, with the majority of estimates being positive (100%). The estimated average Fisher r-to-z transformed correlation coefficient based on the random-effects model was μ̂ = 0.2753 (95% CI (stands for 95% confidence interval): 0.2409 to 0.3096). Therefore, the average outcome differed significantly from zero (z = 15.6952, p < 0.0001). A forest plot showing the observed outcomes and the estimate based on the random-effects model is shown in .

Figure 2. Forest plot of shyness and problematic internet use.

According to the Q-test, the true outcomes appeared to be heterogeneous (Q(24) = 189.6759, p < 0.0001, τ̂ 2 = 0.0055, I2 = 82.6379%), with a 95% prediction interval for the true outcomes of 0.1258 to 0.4247. Hence, even though there may be some heterogeneity, the true outcomes of the studies were generally in the same direction as the estimated average outcome.

Moderating factors

Participant characteristics

We tested whether age group (adolescents vs young adults) was a moderator. The summary of this analysis is shown in . Out of the 25 studies included in the analysis, 11 studies researched adolescents only, and 14 studies looked at young adults. From the subgroup analysis results, the effect size of shyness on problematic internet use seemed to be larger for young adults than for adolescents (Z = −2.25, p < .001). However, homogeneity was not achieved in these two groups.

Table 2. Moderation analysis in the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use

Moreover, we tested whether the country groups (western vs non-western countries) was a moderator. Among 25 studies, 7 studies were conducted in western countries, and 18 studies were conducted in non-western countries. From the subgroup analysis results, there were no significant differences between the two groups, but were each significantly different from zero. Again, the homogeneity was not achieved in these two country groups.

Study characteristics

We tested whether research design (cross-sectional or longitudinal design) was a moderator. Among 25 studies, 20 studies used a cross-sectional design, and 5 studies used a longitudinal design. From the subgroup analysis results, the effect size of shyness and internet addiction seemed to be larger for studies that used a longitudinal design than studies that used a cross-sectional design, but the variance was not statistically significant. Again, homogeneity was not achieved in these two country groups.

At last, the year of publication was tested for subgroup analysis. The studies were divided into two categories: recent studies (published between 2020–2022) and older studies (published before 2020). There were 7 studies that were published between 2020 and 2022 and 18 studies that were published before 2020. Recent studies reported, on average, smaller effects than older studies did. Again, there was no significant difference between the two groups, but were each was significantly different from zero. The homogeneity was achieved only within the most recent studies.

Publication bias

Publication bias was carefully examined in our study through the assessment of the funnel plot of the estimated data, as illustrated in . We employed both the rank correlation test and the Egger’s test, employing a linear regression that considers intervention effect estimates in relation to their standard errors, weighted by their inverse variance, was employed to assess potential indications of asymmetry within the funnel plot (as described by van Enst et al., Citation2014). Notably, the results of these tests demonstrated no significant funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.4730 for the rank correlation test and p = 0.7565 for the regression test). Based on these findings, we can reasonably conclude that there is little evidence to suggest the presence of publication bias in our study.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis examined the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Our findings from this large sample of studies conducted in different countries showed a significant positive association between shyness and problematic internet use in adolescents and young adults. Moreover, our findings indicated that shy young adults presented more severe symptoms of problematic internet use than shy adolescents. In the following section, we provide a summary of the key findings of this work. Limitations and implications for future research are also discussed.

The relationship between shyness and problematic internet use

The findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that shyness was positively associated with problematic internet use among adolescents and young adults. As others have hypothesized, this is likely explained by the fact that shy people may prefer online interactions which in turn, may place them at an increased risk for problematic internet use (Ang et al., Citation2018; Huang et al., Citation2014). Indeed, shy people tend to feel nervous, anxious and experience some physiological symptoms during social interactions, and may lack social resources and support, prompting them to seek alternative ways to interact with others (Ang et al., Citation2018; Ebeling-Witte et al., Citation2007). As they begin to meet their social needs online, it’s possible these communication behaviours become reinforced through a process akin to operant conditioning (e.g., rewarded behaviours are more likely to re-occur) (Sioni et al., Citation2017).

Similarly, going online to avoid negative feelings can act as a different type of reward and also contribute to problematic internet use. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that internalizing problems (e.g., loneliness, social anxiety, and depression) played a mediating role in the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use (Ang et al., Citation2018, Huang et al., Citation2014; Tian et al., Citation2018). This suggests that shy people tend to be more prone to feelings of loneliness and depression and engage in internet use to avoid these feelings. In this way, internet use, whether to gain social interactions or avoid negative feelings, acts as a reward reinforcing problematic patterns of internet use. Furthermore, other studies have demonstrated that shy people have low levels of self-control and self-regulation skills, which are also known risk factors for problematic internet use (e.g., Han et al., Citation2017; Yu et al., Citation2019). Thus, given their difficulties with self-control and self-regulation, the experience of positive reinforcement when engaging with the internet may be particularly hard to resist for shy individuals.

Taken together, the findings of the present systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that shy individuals may be more likely to develop problematic internet use. Thus, future interventions targeting problematic internet use should identify shy individuals and support of individuals with shy tendencies. Furthermore, it may be beneficial for these initiatives to consider ways to enhance the social skills of individuals who lean towards shyness and to encourage their participation in various social activities and interpersonal interactions. This could potentially help mitigate feelings of loneliness and reduce the likelihood of them developing problematic internet use (Lehenbauer et al., Citation2013). At last, professionals might also consider assisting shy adolescents and young adults in developing self-control and self-regulation skills that may be beneficial in reducing their risk of problematic internet use.

It is important to note, however, that two studies included in this review reported no significant relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Specifically, Spensieri et al. Citation(2019) found that shyness alone could not predict problematic internet use. That is, only when controlling for somatic symptoms, was there a significant link between shyness and problematic internet use among Italian adolescents. Their results highlighted the important role of somatic symptoms in understanding the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Similarly, Casale and Fioravanti Citation(2011) discovered that, while shy young adults in Italy find online social interactions less distressing, this does not appear to contribute to their development of problematic internet use. The authors explained that this may be due to the fact that in Italian culture, shyness may not indicate a lack of social skills in real life, but rather being “reserved” and “sophisticated” – both of which hold positive connotations that may not be related to problematic internet use. Nevertheless, future studies should keep investigating the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use in Italian culture.

Moderators in the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use

Apart from the general positive correlation between shyness and problematic internet use, our meta-analyses and systematic synthesis also identifies potential moderators of this relationship. Our results indicated that as compared to shy adolescents, shy young adults are more likely to develop problematic internet use. Young adults may be more vulnerable to problematic internet use than adolescents because their parents’ supervision of their Internet use reduces as they get older. Moreover, as young people, especially shy people, transition from adolescence to young adulthood (e.g., entering university or college), their face-to-face interactions with peers decreases and their time alone increases—which may place them at risk of using the internet to compensate for missing relationships with peers. As such, a shy university student who is not supervised may become overly engaged in online activity (Douglas et al., Citation2008). Therefore, placing them at risk for developing problematic internet use. These findings, however, should be interpreted with caution because both subgroups were found to be heterogeneous within the studies, indicating that participants could be from different populations (i.e., given that there was more variation than would be expected by chance alone). For example, the subgroups (adolescents or young adults) in these various studies may have been comprised of individuals from diverse geographical regions, who had differing levels of exposure to technology and cultural norms regarding internet use, which may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity in the results.

Moreover, country, study design, publication year, and gender did not moderate the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use, indicating that this relationship was consistent across countries, study design, publication year, and gender. However, it is also possible that fewer studies have been conducted in Western countries, in recent years (after 2020) and with longitudinal designs, limiting viability to investigate moderation effects. Similarly, our understanding of how gender interacts with the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use remains unclear, as only three studies have investigated this aspect, and we were unable to draw a conclusive finding. Therefore, future studies should keep exploring these moderation effects.

Limitation and future direction

Evidence from this systematic review and meta-analysis provides insights into the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use while identifying potential mediators and moderators. However, several limitations should be acknowledged as well, with an eye towards directions for future research. To begin with, for the meta-analysis, we only searched for published journal articles, and there may be a publication bias because journals tend to publish only the significant results (e.g., Fanelli, Citation2012). Although we tested for potential publication bias, the unpublished research is still very important as it may help us better understand the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Thus, in future studies, it is necessary to do a meta-analysis including both published and unpublished research (e.g., reached out to researchers, experts, and relevant organizations in the field to inquire about any ongoing or completed studies that may have remained unpublished).

In addition, the present meta-analysis is based on correlational studies and the findings cannot be used to interpret a causal relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. Future empirical studies should further explore a potential causal relationship by using longitudinal design. Lastly, the present study only focused on shy individuals, however, the relationship between other types of social withdrawal, such as social disinterest remains unclear. Specifically, from a motivational perspective, shyness is thought to reflect a social approach-avoidance conflict. That is, shy individuals desire social contact (high social approach motivation) but at the same time are wary and anxious about participating in social exchanges (high social avoidance motivation) (Coplan et al., Citation2004). This distinguishes shyness from social disinterest which is characterized by a non-fearful preference for solitary activities. Social disinterest has also been found to be associated with problematic internet use (e.g., Peever et al., Citation2012). Thus, future studies should keep investigating the relationship between other types of social withdrawal and problematic use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study reveals a moderate association between shyness and problematic internet use among adolescents and young adults. Notably, we observed that shy young adults exhibited more severe symptoms of problematic internet use than their adolescent counterparts. These findings mark a significant contribution, as our study pioneers a systematic investigation into the relationship between shyness and problematic internet use. The implications of this research extend to the realms of understanding and addressing problematic internet use in individuals with shyness, offering valuable insights that can inform future treatment and intervention strategies.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, S., Nasreen, L., & Aiman, M. (2020). *shyness and psychological well-being as predictors of problematic internet use among students in Pakistan. Psicología, conocimiento y sociedad, 10(3), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.26864/pcs.v10.n3.1

- Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517

- Ang, C. S., Chan, N. N., & Lee, C. S. (2018). *shyness, loneliness avoidance, and internet addiction: What are the relationships? The Journal of Psychology, 152(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1399854

- Asendorpf, J. B. (1990). Beyond social withdrawal: Shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Human Development, 33(4–5), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276522

- Baker, L., & McNulty, J. K. (2010). Shyness and marriage: Does shyness shape even established relationships? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(5), 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210367489

- Baker, L. R., & Oswald, D. L. (2010). Shyness and online social networking services. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(7), 873–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407510375261

- Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(4), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

- Barry, C. M., Nelson, L. J., & Christofferson, J. L. (2013). Asocial and afraid: An examination of shyness and anxiety in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Studies, 19(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2012.1979

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bianchi, A., & Phillips, J. G. (2005). Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.39

- Burkauskas, J., Gecaite-Stonciene, J., Demetrovics, Z., Griffiths, M. D., & Király, O. (2022). Prevalence of problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46(1), 101179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101179

- Cam, H. H., & Top, F. U. (2020). Prevalence and risk factors of problematic internet use and its relationships to the self-esteem and health-related quality of life: Data from a high-school survey in Giresun Province, Turkey. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 31(4), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000365

- Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012

- Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2011). *psychosocial correlates of internet use among Italian students. International Journal of Psychology, 46(4), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2010.541256

- Ceyhan, E.,Ceyhan, A. A., & Gürcan, A. (2007). The validity and reliability of the problematic internet usage scale. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 7(1), 411–416. https://scholar.google.ca/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Ceyhan%2C+E.%2C+Ceyhan%2C+A.+A.%2C+%26+G%C3%BCrcan%2C+A.+%282007%29.+The+validity+and+reliability+of+the+problematic+Internet+usage+scale.+Educational+Sciences%3A+Theory+%26+Practice%2C+7%281%29.+411-416&btnG

- Cheek, J. M. (1983). The revised Cheek and Buss shyness scale. Unpublished manuscript, Wellesley College, 2181. Retrieved from: http://academics.wellesley.edu/Psychology/Cheek/research.html

- Chen, Y., Gao, Y., Li, H., Deng, Q., Sun, C., & Gao, F. (2021). *shyness and mobile phone dependency among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of basic psychological needs and family cohesion. Children and Youth Services Review, 130, 106239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106239

- Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., Rose‐Krasnor, L., & Nocita, G. (2014). ‘I want to play alone’: Assessment and correlates of self‐reported preference for solitary play in young children. Infant and Child Development, 23(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1854

- Coplan, R. J., Prakash, K., O’Neil, K., & Armer, M. (2004). Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244

- Coplan, R. J., Schneider, B. H., Matheson, A., & Graham, A. (2010). ‘Play skills’ for shy children: Development of a social skills facilitated play early intervention program for extremely inhibited preschoolers. Infant and Child Development: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 19(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.668

- Crozier, W. R. (2005). Measuring shyness: Analysis of the revised cheek and buss shyness scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(8), 1947–1956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.002

- Douglas, A. C., Mills, J. E., Niang, M., Stepchenkova, S., Byun, S., Ruffini, C., Lee, S. K., Loutfi, J., Lee, J.-K., Atallah, M., & Blanton, M. (2008). Internet addiction: Meta-synthesis of qualitative research for the decade 1996–2006. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 3027–3044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.05.009

- Ebeling-Witte, S., Frank, M. L., & Lester, D. (2007). Shyness, internet use, and personality. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(5), 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9964

- Fanelli, D. (2012). Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics, 90(3), 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0494-7

- Fineberg, N. A., Demetrovics, Z., Stein, D. J., Ioannidis, K., Potenza, M. N., Grünblatt, E., Brand, M., Billieux, J., Carmi, L., King, D. L., Grant, J. E., Yücel, M., Dell’Osso, B., Rumpf, H. J., Hall, N., Hollander, E., Goudriaan, A., Menchon, J., Zohar, J., & Pallanti, S.… Chamberlain, S. R. (2018). Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the internet. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(11), 1232–1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004

- Gao, F., Guo, Z., Tian, Y., Si, Y., & Wang, P. (2018). *relationship between shyness and generalized pathological internet use among Chinese school students: The serial mediating roles of loneliness, depression, and self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01822

- Geng, J., Han, L., Gao, F., Jou, M., & Huang, C. C. (2018). Internet addiction and procrastination among Chinese young adults: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.013

- Gibson, K., & Trnka, S. (2020). Young people’s priorities for support on social media: “It takes trust to talk about these issues”. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.030

- Gioia, F., Fioravanti, G., Casale, S., & Boursier, V. (2021). The effects of the fear of missing out on people’s social networking sites use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of online relational closeness and individuals’ online communication attitude. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 620442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620442

- Han, L., Geng, J., Jou, M., Gao, F., & Yang, H. (2017). *relationship between shyness and mobile phone addiction in Chinese young adults: Mediating roles of self-control and attachment anxiety. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.036

- Henderson, L., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2002). Dimensions of shyness: The ShyQ. Western Psychological Association, 4, 1–19. Retrieved from. http://shyness.com/wp-content/uploads/2002/shyq.pdf

- Hong, W., Liu, R. D., Oei, T. P., Zhen, R., Jiang, S., & Sheng, X. (2019). *the mediating and moderating roles of social anxiety and relatedness need satisfaction on the relationship between shyness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.020

- Huan, V. S., Ang, R. P., & Chye, S. (2014). *loneliness and shyness in adolescent problematic internet users: The role of social anxiety. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(5), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9252-3

- Hughes, N., & Burke, J. (2018). Sleeping with the frenemy: How restricting ‘bedroom use’of smartphones impacts happiness and wellbeing. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.047

- Jin, H., Khodaei, M., & Papadimitratos, P. (2017). Security and privacy in vehicular social networks. In A. M., Vegni, V., Loscr`ı, & A. V., Vasilakos (Eds.), Vehicular social networks (pp. 155–169). CRC Press.

- J Kuss, D., D Griffiths, M., Karila, L., & Billieux, J. (2014). Internet addiction: A systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4026–4052. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990617

- Jones, W. H., Briggs, S. R., & Smith, T. G. (1986). Shyness: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–639. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.3.629

- Katz, S. J., Conway, C. C., Hammen, C. L., Brennan, P. A., & Najman, J. M. (2011). Childhood social withdrawal, interpersonal impairment, and young adult depression: A mediational model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 1227–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9537-z

- Kuss, D. J., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet addiction and problematic internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 143–176. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143

- Kwon, M., Lee, J. Y., Won, W. Y., Park, J. W., Min, J. A., Hahn, C., Choi, J.-H., Kim, D.-J., & Gu, X. (2013). Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PloS One, 8(2), e56936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056936

- Lehenbauer, M., Kothgassner, O. D., Kryspin-Exner, I., & Stetina, B. U. (2013). An online self-administered social skills training for young adults: Results from a pilot study. Computers & Education, 61, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.09.007

- Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children and Media, 2(2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565

- Li, D. (2012). Multiple ecological risk factors and adolescents’ social adaptation: how risks should be modeled and what are their mechanisms[ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. South China Normal University,

- Macedo‐Rouet, M., Potocki, A., Scharrer, L., Ros, C., Stadtler, M., Salmerón, L., & Rouet, J. F. (2019). How good is this page? Benefits and limits of prompting on adolescents’ evaluation of web information quality. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.241

- McCabe, R. E. (2015). Review of the mindfulness and acceptance workbook for social anxiety and shyness: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to free yourself from fear and reclaim your life [review of the book the mindfulness and acceptance workbook for social anxiety and shyness: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to free yourself from fear and reclaim your life, by J. E. Fleming & N. L. Kocovski]. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 56(1), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038090

- Migliavaca, C. B., Stein, C., Colpani, V., Barker, T. H., Ziegelmann, P. K., Munn, Z., Falavigna, M., & Prevalence Estimates Reviews—Systematic Review Methodology Group (PERSyst). (2022). Meta‐analysis of prevalence: I 2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(3), 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1547

- Moretta, T., & Buodo, G. (2020). Problematic internet use and loneliness: How complex is the relationship? A short literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00305-z

- Morita, M., Ando, S., Kiyono, T., Morishima, R., Yagi, T., Kanata, S., Fujikawa, S., Yamasaki, S., Nishida, A., & Kasai, K. (2022). Bidirectional relationship of problematic internet use with hyperactivity/inattention and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A population-based cohort study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(10), 1601–1609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01808-4

- Musetti, A., & Corsano, P. (2018). The internet is not a tool: Reappraising the model for internet-addiction disorder based on the constraints and opportunities of the digital environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1), 558–621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00558

- Nagata, J. M., Magid, H. S. A., & Gabriel, K. P. (2020). Screen time for children and adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md), 28(9), 1582–1621. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22917

- Nhamo, G., Dube, K., Chikodzi, D., Nhamo, G., Dube, K., & Chikodzi, D. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 on gaming, leisure and entertainment industry. Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Industry, 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56231-1_12

- Nikolić, M., Colonnesi, C., de Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2016). Blushing in early childhood: Feeling coy or socially anxious? Emotion, 16(4), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000131

- Ozturk, E.,& Kaymak Ozmen, S. (2011). *an investigation of the problematic internet use of Teacher Candidates based on Personality types, shyness and demographic factors. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 11(4), 1799–1808. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ962675

- Peever, N., Johnson, D., & Gardner, J. (2012, July). Personality & video game genre preferences. In Proceedings of the 8th australasian conference on interactive entertainment: Playing the system (pp. 1–3). https://doi.org/10.1145/2336727.2336747

- Perestelo-Pérez, L. (2013). Standards on how to develop and report systematic reviews in Psychology and Health. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 13(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70007-3

- Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175

- Poli, R. (2017). Internet addiction update: Diagnostic criteria, assessment and prevalence. Neuropsychiatry [ Retrieved from], 7(1), 04–08. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1360294646626601856

- Porter, E., & Chambless, D. L. (2017). Social anxiety and social support in romantic relationships. Behavior Therapy, 48(3), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.12.002

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ## URL.

- Sagie, A., & Koslowsky, M. (1993). Detecting moderators with meta‐analysis: An evaluation and comparison of techniques. Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00888.x

- Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2010). Psychic retreats or psychic pits? Unbearable states of mind and technological addiction. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019414

- Schneider, B. H., & Byrne, B. M. (1985). Children’s social skills training: A meta-analysis. Children’s Peer Relations: Issues in Assessment and Intervention, 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-6325-5_11

- Selkie, E., Adkins, V., Masters, E., Bajpai, A., & Shumer, D. (2020). Transgender adolescents’ uses of social media for social support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(3), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.011

- Seong, W., Hong, J. S., Kim, S., Kim, S. M., & Han, D. H. (2019). Personality and psychological factors of problematic internet gamers seeking hospital treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(1), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00583

- Settanni, M., Azucar, D., & Marengo, D. (2018). Predicting individual characteristics from digital traces on social media: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 21(4), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0384

- Sette, S., Baldwin, D., Zava, F., Baumgartner, E., & Coplan, R. J. (2019). Shame on me? Shyness, social experiences at preschool, and young children’s self-conscious emotions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47(1), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.012

- Sioni, S. R., Burleson, M. H., & Bekerian, D. A. (2017). Internet gaming disorder: Social phobia and identifying with your virtual self. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.044

- Spensieri, V., Cerutti, R., Presaghi, F., Amendola, S., Crozier, W. R., & Mazza, M. (2019). *Italian validation of the children’s shyness questionnaire: Exploring associations between shyness and psychosocial functioning. PloS One, 14(6), e0217722. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217722

- Stritzke, W. G., Nguyen, A., & Durkin, K. (2004). Shyness and computer-mediated communication: A self-presentational theory perspective. Media Psychology, 6(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0601_1

- Tarkhan, M. (2016). The influence of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on loneliness feeling and shyness of students. Social Cognition, 5(2), 94–106. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5319288/

- Tian, Y., Bian, Y., Han, P., Gao, F., & Wang, P. (2017). Associations between psychosocial factors and generalized pathological internet use in Chinese university students: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.048

- Tian, Y., Guo, Z. X., Shi, J. R., Bian, Y. L., Han, P. G., Wang, P., & Gao, F. Q. (2018). *bidirectional mediating role of loneliness in the association between shyness and generalized pathological internet use in Chinese university students: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. The Journal of Psychology, 152(8), 529–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1468309

- Tian, Y., Qin, N., Cao, S., & Gao, F. (2021). *reciprocal associations between shyness, self-esteem, loneliness, depression and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory, 29(2), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2020.1755657

- Tian, Y., Si, Y., Meng, W., Bian, Y., Han, P., Hu, J., Wang, P., & Gao, F. (2019). *mediating factors of the association between shyness and generalized pathological internet use in Chinese university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(3), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9979-4

- Tsitsika, A., Janikian, M., Schoenmakers, T. M., Tzavela, E. C., Olafsson, K., Wójcik, S., Macarie, G. F., Tzavara, C., & Richardson, C. (2014). Internet addictive behavior in adolescence: a cross-sectional study in seven European countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(8), 528–535. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0382

- van Enst, W. A., Ochodo, E., Scholten, R. J., Hooft, L., & Leeflang, M. M. (2014). Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: A meta-epidemiological study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-70

- Van Houwelingen, H. C., Arends, L. R., & Stijnen, T. (2002). Advanced methods in meta‐analysis: Multivariate approach and meta‐regression. Statistics in Medicine, 21(4), 589–624. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1040

- Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta‐analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

- Viera, A. J., & Garrett, J. M., et al (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37(5), 360–363.

- Wang, P., Pan, R., Wu, X., Zhu, G., Wang, Y., Tian, M., Wang, P., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., & Wang, J. (2022). *reciprocal associations between shyness, depression, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A cross-lagged panel study. Addictive Behaviors, 129, 107256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107256

- Xu, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhao, J., Xuan, Z., Li, W., Han, L., & Liu, H. (2021). The relationship between shyness and aggression in late childhood: The multiple mediation effects of parent-child conflict and self-control. Personality and Individual Differences, 182(1), 111058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111058

- Yellowlees, P. M., & Marks, S. (2007). Problematic Internet use or Internet addiction?. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1447–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.05.004

- Yu, Y., Sun, H., & Gao, F. (2019). *susceptibility of shy students to internet addiction: A multiple mediation model involving Chinese middle-school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01275

- Zintzaras, E., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). HEGESMA: genome search meta-analysis and heterogeneity testing. Bioinformatics, 21(18), 3672–3673. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti536 .