ABSTRACT

Health professional education and post-graduate training programs, including residencies, fellowships, and other post-graduate training experiences, may encourage or require trainee participation in continuing education (CE) activity planning and development. Providers of CE should ensure appropriate mentorship and faculty guidance during development of the activity and provide direction on the expectations of adult learning principles (e.g. identification of an educational gap; development of measurable learning objectives; inclusion of independent, balanced, and evidenced-based content; use of active learning techniques; and incorporation of learning assessment methods). Nonetheless, there is no established best practice or approach for how CE providers should ensure trainees are prepared to serve as CE activity faculty. New practitioners provided with an opportunity to participate may be unsure of where to begin and may be hesitant to engage in this new activity. In this manuscript, authors delineate key principles to incorporate when introducing trainees to CE activity development and share outcomes associated with a comparison of trainee- vs. faculty-developed and delivered CE.

Introduction

Continuing education (CE), encompassing educational offerings for medical, nursing, dental, pharmacy, physician assistant, and other health professional specialities, represents a highly regulated education delivery format that is utilised as a mechanism for demonstrating continuing professional competency and for meeting licensure renewal requirements in the United States and Canada [Citation1]. Introducing health professions trainees to CE activity development can provide new practitioners with a variety of foundational teaching experiences that raise their educational skills and acumen and concurrently increase their professional confidence [Citation2].

From the pharmacy education literature, recommendations for post-graduate residency teaching experience include engaging trainees in formal lectures, as co-preceptors and/or preceptors for pharmacy practice experiences, as facilitators of small group discussions, in developing patient case discussions, and optionally, presentation at a local, regional or national meeting [Citation2]. Planning and development of a CE activity for a professional audience may help to achieve these expectations for trainee exposure to teaching experience as part of a post-graduate training curriculum. The benefits of incorporating trainees in CE activity development experiences are multi-fold ().

Figure 1. Benefits for incorporating trainees into CE planning and development [Citation2].

![Figure 1. Benefits for incorporating trainees into CE planning and development [Citation2].](/cms/asset/dddc8565-8b96-485e-8965-69c27f25a435/zjec_a_2270279_f0001_oc.jpg)

Recognizing value to CE providers and trainees alike, the Joint Accreditation: Interprofessional Continuing Education optional commendation criteria, Joint Accreditation Criteria 14 (JAC14), indicates that joint providers of CE may be eligible for accreditation with commendation if, among other factors, providers engage with students of the health professions as planners and teachers in interprofessional continuing education (IPCE) and/or CE activity development [Citation3]. Despite this recognition, there are no best practices or universal guidance recommendations for how CE providers should approach incorporating trainees in the health professions into CE activity development. It is our experience that the process and procedure for introducing trainees to and incorporating trainees in CE activity planning and speaking should be intentional and defined. For example, we recommend trainees receive CE orientation as part of their onboarding, continual support from a CE development office or staff, and ready access to CE committee leadership. At our institution, an introduction to CE activity development is offered at the time of training onboarding with a goal of introducing trainees to the CE planning process early and to encourage collaboration and team-based activity planning. Trainees additionally receive recommendations to start early and allow ample time for receipt of feedback and review of activity contents to ensure alignment with standards and requirements for CE activity development.

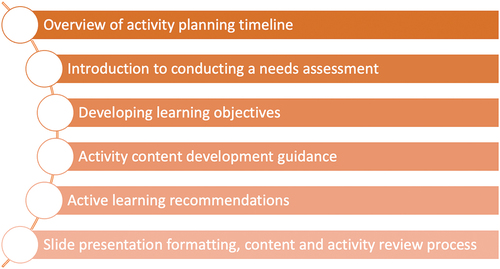

The CE orientation curriculum encompasses key aspects of CE planning and activity development (). Trainees are additionally introduced to the activity planning process, from identifying an unmet educational need (“gap analysis” or needs assessment), identification of planning team members, obtaining appropriate planning forms and working with the CE Office, completing the Activity Planning Form to document the gap analysis, drafting programmatic materials (e.g. activity brochure, announcement, agenda, slides, assessment questions), and conducting the activity itself. A critical element of incorporating trainees into CE planning and delivery as it relates to continuous professional development is that trainees should receive feedback and evaluation results to identify the learner reaction to the educational intervention and whether the activity achieved its stated educational goals. Since CE programs must incorporate post-program assessments, this can be a critical desired outcome of the engagement.

Planning and development of CE activity content is likely different from other presentations, manuscripts or work that trainees have been exposed to previously. Providers engaging in CE activity development with trainees should be mindful to provide appropriate mentorship and guidance during the development of the activity for trainees, as for all faculty. This training should include direction on the expectation of adult learning principles such as [Citation4,Citation5]:

Identification of an educational gap with thorough literature review

Development of measurable learning objectives

Inclusion of independent, balanced, and evidenced-based content

Use of active learning techniques

Incorporation of learning assessment methods

Incorporating CE activity development as an exercise for learners represents an excellent opportunity to expose them to project management principles, to introduce the peer review process if the CE provider is implementing a review procedure for activity content, to the need for identification and mitigation of potential conflicts of interest, and for learners to gain recognition at a local/institutional level, within an organisation, or on a national stage.

At our institution, post-doctoral pharmaceutical industry fellows are employed by the University and have one to two-year appointments to sponsoring pharmaceutical industry companies to gain valuable experience in both the industry and academic environments. Fellows have been encouraged to participate in the CE development process for years as an opportunity to fulfill professional development requirements and teaching opportunities for their postgraduate training, and, thus, their work represented an opportunity to evaluate the impact of learner involvement in CE activities.

Below, the authors conducted a retrospective review of all attended CE activities developed by the unit between 2016 and 2022, comparing activity demographics and evaluation survey results between fellow-led (e.g. developed by fellow planners and speakers) and faculty-led activities (e.g. developed by University faculty members). All activities were formally reviewed by the authors’ CE development office for content, bias, and fair balance. While topics, durations, and number of learners varied for these activities, all evaluation forms included a Likert rating scale for six common questions related to the important activity domains (). The authors recoded the data Likert responses to “Agree” (for “Strongly agree” or “Agree”) and to “Disagree” (remaining options) to facilitate statistical analysis of the two groups with further subgroup analysis of IPCE activities.

Table 1. Evaluation questions shared among all CE activity evaluation forms.

Results

A retrospective review of archived CE evaluations collected for 69 activities offered between 2016 and 2023 found 18 (26.1%) were developed primarily by fellows and the remainder by faculty. An overall response rate of 82.4% was noted among over 500 h of CE and for over 700 activity attendees (). Fellow-led activities were more likely to be shorter in duration (1.8 hr vs 9.0 hr, p < 0.0001) but featured a similar quantity of attendees and completed survey responses. Furthermore, fellow-led activities were more likely to have offered IPCE (50.0% vs 19.6%, p = 0.0131) and more likely to have been held virtually (34.9% vs 13.7%, p = 0.0381).

Table 2. Baseline demographics of included continuing education programs (N = 69).

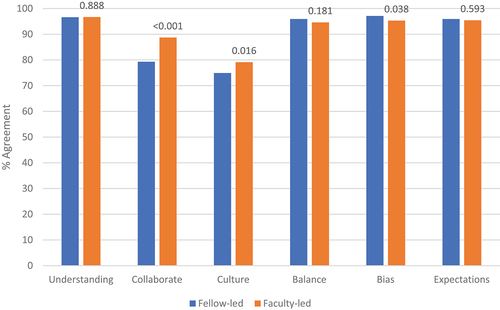

Among the evaluation domains, both groups shared similar agreement in audience understanding of the material, perception of balance, and in meeting expectations. However, divergence was seen in perception of collaboration with other healthcare professionals and cultural competency, with higher ratings for faculty in these domains, and with freedom from bias or influence, with higher ratings for fellows in this domain (). The trends were more robust for the perception of collaboration with other healthcare professionals for both IPCE and non-IPCE activities and freedom from bias or influence for non-IPCE activities. While there was a statistical difference in freedom from bias for fellow- vs. faculty-led CE activities in the unstratified analysis (, p = 0.038), both fellows and faculty received high ratings regarding freedom from bias among IPCE activities (96.6% vs 95.9%, p = 0.576) and non-IPCE activities (97.5% vs 95.0%, p = 0.028) (). Overall, the high response rate and large sample of evaluations demonstrated notable similarities between activities devised by fellows and faculty among survey respondents across multiple domains and characteristics.

Table 3. Comparison of survey respondent “agreement” on evaluation domains stratified by interprofessional activity involvementa.

Discussion

This is the first analysis of which the authors are aware that directly compares fellow-developed to faculty-developed CE activities. Given that many evaluation domains were shown to be similar between groups, fellow-developed activities appeared to provide similar perceived value to their respective audiences. However, the lack of a standardised process or framework in this area leaves room for future evaluation to identify inter-planner variations which may necessitate more structured guidance or oversight from CE providers. Interestingly, the authors noted differences in the perception of collaboration with other healthcare professionals, cultural competency, and freedom from bias. Differences in cultural competency appear to be due to confounding by IPCE focus given the statistical difference is abolished when stratified. Similarly, the statistical difference seen for freedom from bias was driven by non-IPCE activity feedback. The target audiences for fellow- and faculty-led programs may differ where clinicians are more likely to attend faculty-led programs compared to employees of pharmaceutical companies, each of which perceive interprofessional collaboration in a different perspective. All CE activities are reviewed for potential bias prior to presentation, but different target audiences may ultimately perceive bias differently regardless of IPCE focus or based on the speaker.

Furthermore, this analysis was limited by the possible impact of selection biases among non-responders and from the varied audience populations educated; often, fellow-produced activities were presented at their sponsoring pharmaceutical company and thus the perception of collaboration, cultural competency, and what entails bias in education may vary considerably compared to practitioners in patient-facing roles or within academic appointments.

While these results are not fully generalisable to other classes of trainees (e.g. pharmacy residents, students, research fellows), this experience establishes a framework for evaluation of CE conducted by other types of trainees or other professions to elucidate the value imparted by trainee engagement within CE development. Other limitations of this analysis include failure to capture or account for generational trends, significance of the nature of the topics of the developed CE experiences with some implication in timing differences found. Further evaluation across geographies and trainee type as well as control for activity demographics and programmatic qualities can provide clearer evidence to the impact of trainee-involvement in the provision of CE. Likewise, prospective multicentric analysis to a larger population may help elucidate the interesting findings observed in this observational study.

Conclusion

Engaging trainees of the health professions in CE or IPCE activity planning and teaching as a learning experience during their training represents one strategy for exposing learners to the nuances of this aspect of health professional education in a hands-on way. Introduction to all elements of CE activity planning process – from gap analysis and assessment of educational need, concept application (e.g. development of learning objectives, content development, learning assessment), presentation and communication skills – cumulatively represents an opportunity to develop trainees’ skills in educational content development and communication. With planning, guidance, and intention, CE or IPCE providers can readily offer this educational exercise to trainees they may interact with. Future evaluation of trainee-developed CE is necessary to identify predictors of successful CE outcomes and to measure the impact on professional development gained through this experience.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Debra Diller, Continuing Education Office Staff at the Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy, Rutgers University, for her support of the Continuing Education activity of the unit and Elizabeth Ward, MSJ, Executive Director, Rutgers Center for Continuing and Outreach Education, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, for her leadership and guidance.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no financial interests or disclosures related to the content of this manuscript.

References

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on planning a continuing health professional education institute. redesigning continuing education in the health professions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. Appendix C, International Comparison of Continuing Education and Continuing Professional Development. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219800/

- Havrda DE, Engle JP, Anderson KC, et al. Guidelines for resident teaching experiences. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(7):e147–5. doi: 10.1002/phar.1250

- Become a jointly accredited provider with commendation, joint accreditation: interprofessional continuing education. [cited 2013 July 6]; Available from: https://jointaccreditation.org/accreditation-process/requirements/commendation/

- Joint accreditation criteria, joint accreditation: interprofessional continuing education. [cited 2023 July 6]; Available from: https://jointaccreditation.org/accreditation-process/requirements/criteria/

- Accreditation standards for continuing pharmacy education, accreditation council for pharmacy education. [cited 2023 July 6]; Available from: https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/CPE_Standards_Finalv5_Updated_February2023.pdf