Abstract

Consumer socialization theory provides a means of understanding how adults drew on the expert knowledge of socialization agents to develop the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to function in a COVID-19 world. In this paper, we report on a project conducted in partnership with two universities, a local health district and First Nations researchers to understand the role of socialization agents in supporting the community response to the threat of COVID-19. A quantitative survey was conducted of 701 individuals in rural, regional and remote New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The socialization agents they used could be categorized into four types (Government, Professional, Personal, and Mass Media). The community could be segmented based on the types of socialization agents they used, and there was a significant difference across the segments in terms of their behavioral intentions and their adoption of preventative health behaviors, such as wearing masks and social distancing. The results point to the need to leverage the role of socialization agents during social change and to use targeted health-based promotion.

Plain Language Summary

When a big change like COVID-19 happens, people go through a period of socialization, where they learn how they are expected to act in the new situation. People draw on the knowledge of influential and trusted sources: socialization agents. This research found that in COVID-19 the socialization agents people used could be classified into four types (Government, Professional, Personal and Mass Media). Four types of people could be identified based on the socialization agents they used and the groups differed in their demographics and behaviour. These findings help us to understand how to better communicate to those groups next time.

Introduction

Early in 2020, Anderson et al. (Citation2020) suggested that the response of individuals would be crucial to the success of country-based COVID-19 mitigation measures. In accord with this, one of the four strategic objectives identified by the Australian health sector in its emergency response plan for COVID-19 was to “inform, engage and empower the public” (Department of Health, Citation2020, p. 3). The success of such mitigation strategies relied on the entire population understanding what was expected of them and then complying with those expectations. Consumer socialization theory tells us that when a person has learned to think and feel according to society’s expectations, in this manner they have been socialized (Moschis, Citation1987). Thus, socialization theory provides a useful lens through which to examine how people understood and responded to the new societal expectations that emerged rapidly due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

When individuals encounter unfamiliar situations (e.g., Aleti et al., Citation2015), there is an intensification of learning as they adjust. Moschis (Citation2007, p. 297) stated that “changing life conditions in the form of life event experiences create physical, social and emotional demands and circumstances to which people must adapt”. One of the ways that people adapt is by seeking the support of a trusted source with expert knowledge, i.e., a socialization agent (Chan & McNeal, Citation2006; Watne & Brennan, Citation2011). Socialization agents can be organizations or individuals who teach people the knowledge, skills, and attitudes they need to function as a member of a social group (Brim & Wheeler, Citation1966; Chan & McNeal, Citation2006). As such, socialization agents can be central to facilitating a desired social change through the information they provide (Paek et al., Citation2011). Accordingly, they have been observed to be important facilitators in situations where health advice and health services are changing rapidly (Mshingo & Muhanga, Citation2021).

The ability to effect change is evidenced in studies showing a link between socialization agents and household and/or individual-level behavior. Examples of such behaviors include: increasing sustainability (Francis & Davis, Citation2014), reducing adolescent drinking (Harris et al., Citation2015), and assisting the adoption of new technologies (Perez et al., Citation2019). Further, and relevant to the COVID-19 context, Sengupta and Wang (Citation2014) found both personal sources of information and the media influenced behavioral intentions during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009. However, relatively little is known about how cohorts of adult consumers are socialized to the new societal expectations that emerge during periods of significant social change, such as COVID-19, or which information sources they use as socialization agents.

This investigation aimed to 1) identify which socialization agents people used during the first year of COVID-19 (2020), and 2) examine whether the use of socialization agents differed across segments of the survey population, and if so, 3) whether those segments differed in their adoption of preventative health behaviors.

Working in partnership with a local health district, we employed an online panel survey to identify which socialization agents people turned to for information and how their use may have differed across segments of the population. Further, we sought to explore whether there was any difference in behavioral intention and actual use of preventative health measures between different population segments, dependent on different socialization agents. This information could address the absence of knowledge about adult socialization and demonstrate the value of incorporating socialization agents in developing communication strategies during periods of significant change.

In the following sections of the paper, we draw on both the consumer and health socialization literature to describe what is known about the socialization agents that adults turn to during times of change. Next, we explore the relevance of understanding socialization agents in the context of COVID. We then outline the quantitative methods employed to reveal the four types of socialization agents people used and four distinct segments of the survey population that differed in terms of how they sought information and complied with preventative health measures.

Adult socialization

Much is known about how the young are socialized, referred to as primary socialization, as evidenced in several meta-analyses on the subject (e.g., John, Citation1999; Mikeska et al., Citation2017; Mishra & Maity, Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation1990). However, as commonly acknowledged in the literature, much less is known about how adults are socialized, (i.e., secondary socialization) (Bodkin et al., Citation2013; Ekström, Citation2006). The contexts of research into adult socialization are limited, with the adoption of new technology (e.g., Watne et al., Citation2011) and pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., Gentina & Muratore, Citation2012) being the most prominent in the research. What is consistent in these contexts is that there is a relatively quick period of social change based on innovation or shifts in cultural values. Periods of change such as these are helpful because, as Watne and Brennan (Citation2011, p. 369) point out in their discussion of environmental sustainability, “…the rapidly changing situation leads to the inability to effectively engage with the issue without personal expertise”. In such a context, people turn to others, socialization agents, with expert knowledge to support their learning and help them understand the most appropriate ways to respond to changing social expectations. This echoes the context of COVID-19.

Socialization agents

In their seminal work, Chan and McNeal (Citation2006, p. 37) defined socialization agents as “specific sources from which norms, attitudes, motivations, and behaviors are transmitted to consumers”. Commonly acknowledged socialization agents in the consumer socialization literature include parents, children, peers, and the media (e.g., Chaudhary & Gupta, Citation2012; Moschis & Churchill, Citation1978; Watne et al., Citation2014), and more recently the internet and social media (e.g., Aleti et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2012). The role of social media influencers has gained particular attention (Chu & Sung, Citation2015; Gangwar & Dewani, Citation2022). However, the same three agents (parents, peers, and mass media) have invariably been the focus of investigations in the consumer socialization literature since they were first identified by Moschis and Churchill in 1978. In their review, Mshingo and Muhanga (Citation2021) identified the importance of socialization agents in health literacyFootnote1 and in interventions designed to influence health knowledge. Socialization agents can persuade based on their attributes, such as knowledge, expertise, or social standing (Cialdini, Citation1993).

In health socialization processes, researchers have recognized the inherent difference between types of socialization agents based on the nature of their relationship with the learner; for example, interpersonal (parents, peers, school) or media (Push media: TV radio, newspaper, and Pull media: The internet) (Paek et al., Citation2011). The relationship between the different types of socialization agents and health-based outcomes, such as improvements in health literacy has also been investigated; for example, in identifying the importance of doctors and pharmacists in health decisions (e.g., Lee et al., Citation2007; Paek et al., Citation2011; Sengupta & Wang, Citation2014). However, like much of the consumer socialization literature, the focus of this and other health socialization studies (e.g., Downey & Gudmunson, Citation2017; Lees & Tinsley, Citation2000) is on children and adolescents. And so the need persists in a health context to understand how these findings pertain to adult socialization.

The impact of different socialization agents on people’s health-related attitudes, intentions and behaviors needs to be considered in developing public policy and social and health marketing strategies, particularly where the matter in question has life-threatening consequences (Sengupta & Wang, Citation2014). Moreover, health communications must be transmitted through appropriate channels (Sengupta & Wang, Citation2014, p. 358), so that socialization agents are used effectively to support efforts to improve health outcomes (Mshingo & Muhanga, Citation2021). Therefore, our first research question is: Which socialization agents are people using to support their learning in relation to COVID-19?

COVID-19

COVID-19 was the catalyst for rapid social change. At the start of the pandemic, most of the community, regardless of age, had little or no experience, knowledge, or expertise to guide them through the pandemic (except for medical and health professionals with expertise in the area of pandemics). This was a high-stakes situation where there was a strong motivation for individuals to quickly understand the attitudes, skills and behaviors required to function in the COVID world. Because there was a high need for individuals to quickly understand what was expected, many organizations responded. The result was an overabundance of information during the pandemic with many sources providing “expert knowledge” about COVID-19 risks and protective behaviors (Liu et al., Citation2021). This led to the emergence of terms like “infodemic” (Rathore & Farooq, Citation2020) and “COVIO” (COVID-19 overload) (Mohammed et al., Citation2021). Even though some groups, such as migrants with little English, were left behind, a difficulty for most individuals was determining which from the myriad of “expert information” to listen to. In fact, it was observed that people began seeking additional information to authenticate what they were reading (Mohammed et al., Citation2021). The challenge then was to understand, of the information sources available, which one’s people used as socialization agents.

Considering the volume of information available, our a priori expectations were that people may have used a combination of information sources as socialization agents. Individuals are often influenced by more than one socialization agent at a time; for example, advertisers and parents (North & Kotzé, Citation2001); peers and mass media (Paek et al., Citation2011). People use socialization agents to gather information and also to understand norms of behavior (Barber, Citation2013). Further, different cohorts (e.g., genders or generation X vs Y) focus on different types of socialization agents. For example, Lee et al. (Citation2007) found a difference in the use of socialization agents for minority groups, different genders, and those with poor health. Using a combination of descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis, we set out to see if we could identify different groups or segments in the community and understand how best to communicate to those groups in times of change. Hence, our second research question was: Can we segment the population based on which socialization agents individuals use?

Materials & methods

An online survey was conducted with adult respondents (over 18 years of age) living in rural, regional, and remote areas of NSW, Australia. The survey was one used during the H1N1 influenza pandemic (Bults et al., Citation2011) and adapted for COVID-19 by the research team with the support of a survey design specialist. Additionally, it was pilot tested by both a focus group and the Aboriginal Reference Group (ARG) overseeing the project to ensure the instrument and processes were culturally appropriate for First Nations Australians (see details in Allan et al., Citation2022; Lawrence et al., Citation2023). Data collection took place between July and October 2020 and focused on participant experiences of the first COVID-19 lockdown in Australia, which occurred between April and May 2020. The questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Ethics approval was provided by the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW (AH&MRC) (1668/20) to enable the analysis of First Nations responses and the Charles Sturt Univerity Ethics Committee (H20254). Participants were recruited using two online panel providers (Dynata and Qualtrics), as neither could provide sufficient respondents in the region. A second pilot phase was implemented by both providers, sending the survey to a small number of their panel members to check the questionnaire and identify any potential issues. Quota sampling was employed using age and gender quotas to ensure the representativeness of the data (Ochoa & Porcar, Citation2018).

Measures

Data were collected for a series of demographic measures (age, education, gender, and First Nations status). Respondents were asked about their intention to comply and actual compliance with preventative health measures. They were also asked about the types of information-seeking behaviors they engaged in (Did you actively seek information (yes/no) about a) the COVID virus, b) changing rules and c) preventative health measures?). The word “actively” was included to differentiate purposeful goal-oriented information-seeking behavior from passive exposure to information (Anker et al., Citation2011, p. 346). Thirteen information sources that could be characterized as socialization agents were compiled based on those identified in the literature (e.g., family, mass media, social media, doctors, and pharmacists) and those that were relevant during the lockdown (e.g., government press conferences, WHO). Medical centers and community leaders were added following suggestions made by the ARG. A full list is provided in . From this point on we will refer to these as socialization agents.Footnote2 In keeping with the literature (e.g., Barber, Citation2013; Paek et al., Citation2011), to determine whether the sources were being used as socialization agents, a self-reported frequency measure was used (responses on a five-item scale: Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, All of the time). In our analysis, the most frequently used sources were those that respondents indicated they were using “Often or All of the time”.

Further, because socialization agents are characterized as having influence (Aleti et al., Citation2018; Cialdini, Citation1993), respondents were also asked to indicate how much influence they felt each of the 13 sources had on their behavior (responses on a five-item scale of No Influence, A little influence, A moderate influence, A considerable influence, A great influence). In our analysis, the most influential sources were those where respondents indicated a source having “A considerable or great influence”).

Analysis

Online survey responses were assessed using a combination of descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis, conducted using SPSS statistical analysis software. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to identify underlying groupings in the list of 13 socialization agents used in the questionnaire (Coakes & Steed, Citation2007). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was used to determine if there was sufficient correlation in the data to run an EFA, with an KMO of > 0.5 considered suitable (Hair et al., Citation2006). A principal component analysis was used to identify a parsimonious number of factors in the data (Hair et al., Citation2006). The number of underlying variables was identified based on the scree plot, exclusion of eigenvalues less than one, percentage of variance explained > 50%, and communalities greater than 0.5 (Malhotra et al., Citation2006). An Oblimin or Oblique rotation was chosen as it provided a set of simple meaningful factors, which did not need to be uncorrelated (Hair et al., Citation2006).

A hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted using Ward’s method and the Squared Euclidean Distance. Several tools were used to determine the cluster solution, including a dendrogram, agglomeration schedule, and size of clusters. The responses across groups were then tested for significant differences using ANOVA and Chi-square tests to indicate validity (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, Citation1984). We used the raw data rather than the factor scores to avoid the acknowledged issues with using factor scores to run the cluster analysis (Sheppard, Citation1996).

Results

Seven hundred and one complete responses were received (), with the sample largely resembling the western NSW population.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

However, there were some significant differences. For instance, females were overrepresented in the sample (63.6%), as were those in the 18–29 age group (21.6%), while those in the 70+ category were underrepresented (13.6%). As shown in , First Nations respondents represented 8.6% of the sampleFootnote3 which was more than the state average (3.4%) and lower than the regional average (13%) (Aboriginal Affairs NSW, Citation2019).

Information search behavior

As shown in , people were actively seeking information to understand the virus (74.6% of respondents) and the new societal expectations, with 84.6% seeking information about changes to rules related to travel, work, and social distancing, etc., and 79.1% of respondents seeking information about recommended preventative measures (hand sanitizing, masks, and gloves, etc.). Next, we look at how often people used the various socialization agents.

Table 2. The type of information sought.

Most frequently used socialization agents

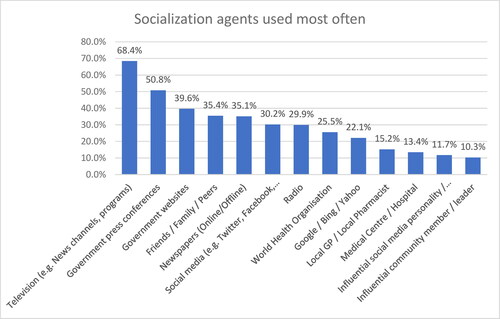

As shown in , television was the most frequently reported socialization agent (68.4% used it all the time or often), followed by government press conferences (50.8% used it all the time or often). The next most important agent reported was government websites. Interestingly, social media influencers were only used frequently by 11.7% of respondents, slightly above influential community members (10.3%).

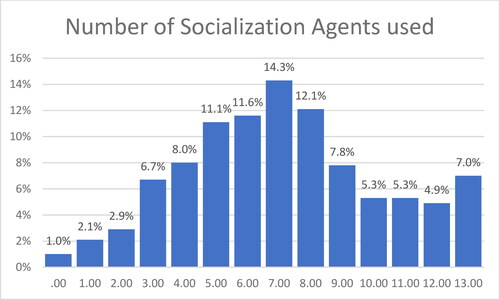

Of note here is that most respondents accessed a combination of agents for information. Further analysis revealed that respondents accessed seven different socialization agents on average (SD 3.1). As shown in , just under a quarter (22.5%) of respondents used 10 or more agents, reinforcing the strong motivation to seek information discussed in other research (e.g., Mohammed et al., Citation2021).

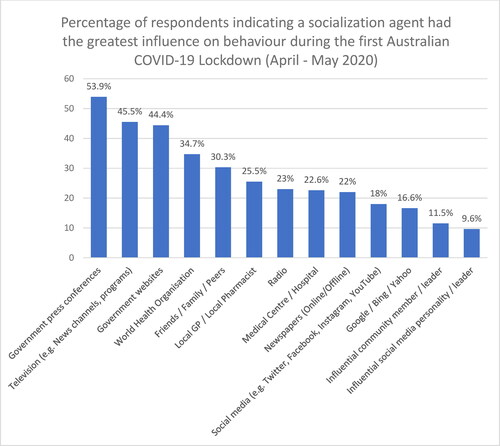

Socialization agents perceived to be most influential

The same three most used socialization agents were also considered the most influential (government press conferences, TV, and government websites), though the order changed with government press conferences (53.9%) being considered the most influential (). It is also interesting to note that while family and friends were the fourth most frequently used socialization agent (), the World Health Organization was perceived to be the fourth most influential (34.7%), with family coming in fifth (30.3%) (). In this case, social media influencers were perceived to have the greatest influence by only 9.6% of respondents. While these findings looked at the population in general, in the next section we begin to explore whether cohorts of the population relied on different socialization agents.

Categorization of socialization agents

The first aim of this investigation was to identify which socialization agents people were using during the first year of COVID-19 (2020) to see if they could be used for segmentation. To do this, we first examined if the 13 socialization agents identified could be classified into types. Accordingly, we ran an exploratory factor analysis using the “frequency of use” measure and found that the 13 types of socialization agents could be collapsed into four broad categories. Frequency was chosen as it was considered the most objective of the possible measures. An Oblimin rotation revealed a four-factor solution (factor scores lower than 0.45 were suppressed) with a KMO score of 0.829 (greater than the recommended benchmark of 0.5). The choice of a four-factor solution was made based on eigenvalues greater than 1, the fact that the four-factor solution explained 65.6% of the variance in the data, and 11 of 13 commonalities were greater than 0.5.

Four factors were identified that reflected four categories of socialization agents. Listed in order of the percentage of variance explained by the factor, they were:

Professional sources (medical center, GP/pharmacist, influential community member).

Mass media (TV, radio, newspapers).

Government sources (government press conferences, government websites, WHO).

Personal/informal sources (friends, family, social media, and Google).

Segmentation analysis

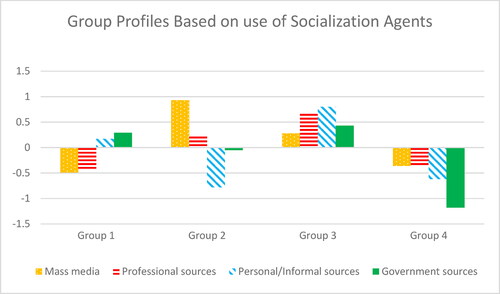

The second aim of this research was to identify whether the use of socialization agents differed across segments of the sample and, subsequently (aim three), whether the use of different socialization agents was reflected in the adoption of preventative health behaviors. A cluster analysis was used to investigate whether the use of socialization agents varied across different groups in the community. Reflecting the fact that many people use a combination of socialization agents, we ran a hierarchical cluster analysis (using the 13 socialization agents) and then profiled the groups identified using the four main factors identified in the EFA. The results are shown in .

Figure 4. Profile of groups based on how often they used different socialization agents.

NB: These groups are named following the discussion of their characteristics in

The first thing evident from is that each group used a different combination of socialization agents and each group is distinct in the extent to which they use the different types. Group 1 has a similarly low level of use of Professional sources and Mass media as Group 4, but a much higher use of Personal and Government sources. Group 2 uses Mass media far more than any other group and uses Personal sources the least often. Group 3 uses Personal sources, Professional sources (i.e., GPs, etc.) and Government sources more than any other group and has moderate use of Mass media. In contrast to the other groups, members of Group 3 tend to use all four sources. Finally, Group 4 searched least often on all types of sources (second lowest on Personal sources), but interestingly, is the lowest by far in their use of Government sources. The key characteristics of each group are shown in . The measures of significance were used to examine if the groups differed significantly across each of the variables used to profile them.

Table 3. Significant difference across segments.

Group 1: Younger, rule-driven, females. This is the largest group (34.7%). Respondents in this group are more likely to be females, and with an average age of 42 years, are one of the two youngest groups (Group 3 has a similar average age). This group also had the second highest intention to comply with the preventative measures. Most strikingly, 94.7% of this group sought information about the new rules associated with COVID.

Group 2: Older, mass media users with best intentions. This is the smallest group (18.4%), respondents in this group are significantly older than the other groups (p = 0.00) and less likely to include First Nations respondents.

Group 3: Younger, info-seeking adopters. Like Group 1, this group has the youngest members. Members of this group have the highest level of educational attainment across the groups. This group has a much higher proportion of First Nations participants (19%) than other groups. The percentage of First Nations respondents in this group is more than twice that of the sample (8.4%) and higher than the average of the region (13%). This group also has the highest level of actual compliance with preventative measures.

Group 4: Non-info-seeking, non-adopters. In addition to having the lowest use of all four information sources, this is the second oldest group. They have the lowest level of education, the lowest level of intention to comply, and the lowest level of actual compliance with preventative measures. Similarly, a significantly lower proportion of this group sought information about COVID, rules of behavior, and preventative measures.

Discussion

The aims of this investigation were to 1) identify which socialization agents people were using, 2) examine whether the use of socialization agents differed across segments of the sample, and 3) see whether those segments differed in their behaviors.

First, which socialization agents? Many survey respondents were actively seeking information about COVID-19, new rules of behavior, and preventative measures. Based on the literature and relevant emerging sources, 13 potential socialization agents were investigated. Of these, three were used most frequently and perceived as most influential – Government press conferences, Television (e.g., news channels and programs), and Government websites.

Those 13 sources could be categorized into four distinct types of socialization agent: 1) Professional sources, 2) Mass media sources, 3) Government sources, and 4) Personal sources. Types 1, 2, and 4 reflected those groups already used in the health socialization literature (e.g., Lee et al., Citation2007; Paek et al., Citation2011; Sengupta & Wang, Citation2014). The identification of government sources as a separate factor was new, as previously, the government had been included under mass media (Sengupta & Wang, Citation2014). This finding reflected other studies that occurred at the same time and also revealed the importance people placed in government information (e.g., Ali et al., Citation2020).

Second, we found that it was possible to create a meaningful segmentation based on which socialization agent was used. We identified four segments of the survey population that differed in terms of their information-seeking behavior, demographic characteristics, and intention and actual compliance with preventative measure. Some respondents (e.g., Group 3: Younger, info-seeking adopters) used many sources of information all the time, while others (e.g., Group 4: Non-info-seeking, non-adopters) were less inclined to access the types of socialization agents we measured, especially government sources. Group 4 were not informed, were older, less educated, and their intention and actual adoption of preventative measures were significantly lower than the other groups (p = 0.005), and as a result, they were potentially at risk of catching and or passing on the virus. Similarly, they were significantly less inclined than other groups to seek information about COVID, rules of behavior, or preventative measures. Third, this segmentation helped to identify those who are less inclined to comply and, therefore, pose the greatest risk to the rest of the population in the event of a COVID-19 outbreak or future pandemic, keeping in mind that this is not an indicator of causal relationships but rather differences across the groups.

In addition, this reveals the types of communication strategies that may work better for each group. For instance, Group 1: Young, rule-driven females may value communication that foregrounds the rules they must follow. They have high intention to comply, and communication to this group could include calls to action (Chen et al., Citation2020) to ensure their good intentions translate into actual compliance behaviors. Based on our findings, the best channels to communicate with this group would be Government sources and Personal sources. In contrast, Group 4: Non-information-seeking non-adopters are engaging much less frequently with any type of socialization agent and less frequently with government sources. They are not actively seeking information to the same extent as the other groups and may require different strategies, such as reframing the problem (Van Lange et al., Citation2013) nudging their behavior to motivate engagement or to build awareness (Higgins et al., Citation2012). However, some additional investigation may be required to understand why this group is not looking for information and to better understand what sorts of socialization agents this group perceives as influential.

This research contributes to our understanding of consumer and health socialization in several ways. First, we have shown that periods of large-scale social change, such as COVID-19, provide an opportunity to investigate secondary socialization, as there are large cohorts of the population being socialized at the same time. This helps to overcome one of the acknowledged difficulties in understanding secondary socialization (Ekström, Citation2006) – finding a group of adults that are going through a socialization process at the same time.

Second, we have identified the government as a new type of socialization agent. Historically, the idea that governments can play an important role as socializing agents in the health socialization process has received little attention.Footnote4 Our finding is consistent with research in other fields that has shown the important role of government communication during a public health crisis (see, for example, Lee & Hong, Citation2016; Teasdale & Yardley, Citation2011) and COVID-19 (e.g., Ali et al., Citation2020). Our cluster analysis revealed that the role of government as a socialization agent was more relevant for some groups than others (e.g., it was relevant for Group 1: Younger, rule-driven females and Group 3: Younger, info-seeking adopters). Likewise, Sengupta and Wang (Citation2014) included government sources in their investigation of the H1N1 (swine flu) global pandemic vaccination intentions and found that personal information sources played a more significant role than mass media (and hence the government, included in the same category).Footnote5 Both these findings suggest a need for a more nuanced understanding of the role of government as a socialization agent in future research.

Third, the fact that Government sources (websites, press conferences, and the WHO) were identified as most influential more often than family in our research suggests a difference between primary and secondary socialization. Most primary socialization research is focused on the young and often in the context of familial households. Accordingly, the role of family as a socialization agent is significant, as Mshingo and Muhanga (Citation2021, p. 120) state family “are the individuals who normally have the utmost influence in socialization processes”. This role of the family is also present in investigations of secondary socialization because they often focus on the role of children socializing their parents in the use of technology and (e.g., Bodkin et al., Citation2013; Perez et al., Citation2019) and the pro-environmental behavior (Gentina & Muratore, Citation2012). This suggested interesting opportunities for future research to disentangle the relative influence of family as socialization agents in primary versus secondary socialization and across contexts.

This research also contributes to our understanding of the COVID-19 experience by revealing people’s experiences in a rural, regional, and remote context. People in these areas can have limited access to healthcare, fewer facilities, as well as generally poorer health, so the impact of any health problem can be significant (Allan et al., Citation2022). Though infections can spread more quickly in more densely populated areas, once the virus arrives in rural areas the impacts on the population are more serious (Allan et al., Citation2022). Accordingly, for the health sector it is important to understand how to localize communication effectively and this analysis provides the means to achieve that.

We also demonstrated how understanding which socialization agents people are using can facilitate a targeted approach to communication. At a macro level, this approach showed the importance of clear messaging across information sources so that, no matter the socialization agent, the same key message is communicated. At the same time, it also identified a group that was not as informed or as compliant and that could pose a risk of spreading the virus; this group required more investigation and a different approach to increase engagement. The need for a targeted approach is not novel and was considered by others during this period. For instance, Kamenidou et al. (Citation2020) explored segmenting the market based on behaviors, whereas Tagliacozzo et al. (Citation2021) looked at how to enact a targeted approach on Twitter; for example, through the use of the content in posts (e.g., naming a vulnerable group such as pregnant women). The value in our approach is that the segmentation provides policymakers with actionable information that can directly inform their communication strategies and a means to diagnose why messages may not be reaching certain groups.

This study had several limitations. For instance, the emergence of the government as a distinct type of socialization agent from our analysis was a contribution of this research; however, there is still a need to disentangle the relationship of television and government press conferences as this was the medium used to broadcast press conferences. We asked about types of socialization agents but did not capture the content or quality of information sources. For this reason, we were unable to capture the role of mis- and dis-information during the pandemic. There may be some recall bias, however, it is likely to be minimal as the survey began shortly (two months) after the period of interest. Further, we relied on the self-reports about the level of influence a source had on behavior, hence we could not capture latent effects. Finally, while the sample resembles the population in the survey region there are statistically significant differences and therefore, care needs to be taken in the generalization of the findings.

Conclusion

This research contributed to both the current understanding of consumer socialization in a health context and the response of the rural population to shifting societal expectations related to COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

The emergence of government socialization agents as a type in this taxonomy was novel and highlighted the important role of government as a socialization agent during the initial COVID lockdown in Australia between April and May 2020, though further research is needed to disentangle the role of government and the media. Similarly, both the consumer and health socialization literature would benefit from further research about how to develop a more nuanced understanding of when an information source is or isn’t a socialization agent.

The study provided a useful segmentation strategy whereby, in the future, healthcare providers in rural, regional, and remote communities could both tailor their communications and identify vulnerable groups that are not engaging with key messaging or socialization agents.

Overall, the findings illustrate the important role of socialization agents in facilitating a population-wide response to change. In turn, this highlights the importance of both understanding the process of socialization and supporting socialization agents by providing them with the expert information they need to facilitate change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The “degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information” (Ratzan & Parker, Citation2006, p. 713) for decision making.

2 See additional discussion about future research in the Conclusion.

3 Because this region had a significantly higher proportion of First Nations peoples than the rest of the state various efforts were made to encourage the representation of First Nations respondents (for more details, see Allan et al., Citation2022; Lawrence et al., Citation2023).

4 See Khodayari et al. (Citation2020) for an exception.

5 This finding could be explained by the observation that not all pandemics are equally threatening (Rogers, Citation2020). H1N1 (swine flu) did not have the same mortality rate as the COVID-19 virus and accordingly did not warrant individuals placing more trust in government sources than personal sources of information. Indeed, research attesting to a predictive relationship between fear levels during a public health crisis and people’s willingness to engage with and follow government directives (see, for example, Chon & Park, Citation2021) would seem to lend support to this interpretation.

References

- Aboriginal Affairs NSW. (2019). Key data-NSW Aboriginal People. NSW Government. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from https://www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/media/website_pages/research-and-publications/facts-and-figures/KEY-DATA-ABORIGINAL-PEOPLE-SEP-2020.pdf

- Aldenderfer, M. S., & Blashfield, R. K. (1984). Cluster analysis. In J. L. Sullivan & R. G. Niemi (Eds.), Quantitative applications in the social sciences (pp. 1–13). Sage Publications.

- Aleti, T., Brennan, L., & Parker, L. (2015). Consumer socialization agency within three-generational Vietnamese families. Young Consumers, 16(2), 172–188.

- Aleti, T., Ilicic, J., & Harrigan, P. (2018). Consumer socialization agency in tourism decisions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(3), 234–246.

- Ali, S. H., Foreman, J., Tozan, Y., Capasso, A., Jones, A. M., & DiClemente, R. J. (2020). Trends and predictors of COVID-19 information sources and their relationship with knowledge and beliefs related to the pandemic: Nationwide cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(4), e21071.

- Allan, J., Kleinschafer, J., Saksena, T., Rahman, A., Lawrence, J., & Lock, M. (2022). A comparison of rural Australian First Nations and Non-First Nations survey responses to COVID-19 risks and impacts: implications for health communications. BMC Public Health, 22, 1276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13643-6

- Anderson, R. M., Heesterbeek, H., Klinkenberg, D., & Hollingsworth, T. D. (2020). How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet (London, England), 395(10228), 931–934.

- Anker, A. E., Reinhart, A. M., & Feeley, T. H. (2011). Health information seeking: A review of measures and methods. Patient Education and Counseling, 82(3), 346–354.

- Barber, N. (2013). Investigating the potential influence of the internet as a new socialization agent in context with other traditional socialization agents. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 21(2), 179–194.

- Bodkin, C. D., Peters, C., & Amato, C. (2013). An exploratory investigation of secondary socialization: How adult children teach their parents to use technology. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 3(8), 5–15.

- Brim, O. G., & Wheeler, S. (1966). Socialization after childhood: Two essays. J. Wiley.

- Bults, M., Beaujean, D. J., de Zwart, O., Kok, G., van Empelen, P., van Steenbergen, J. E., Richardus, J. H., & Voeten, H. A. (2011). Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 2.

- Chan, K., & McNeal, J. U. (2006). Chinese children’s understanding of commercial communications: A comparison of cognitive development and social learning models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(1), 36–56.

- Chaudhary, M., & Gupta, A. (2012). Exploring the influence strategies used by children: An empirical study in India. Management Research Review, 35(12), 1153–1169.

- Chen, T. Y., Yeh, T. L., & Chang, C. I. (2020). How different advertising formats and calls to action on videos affect advertising recognition and consequent behaviours. The Service Industries Journal, 40(5-6), 358–379.

- Chon, M.-G., & Park, H. (2021). Predicting public support for government actions in a public health crisis: Testing fear, organization-public relationship, and behavioral intention in the framework of the situational theory of problem solving. Health Communication, 36(4), 476–486.

- Chu, S. C., & Sung, Y. (2015). Using a consumer socialization framework to understand electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) group membership among brand followers on Twitter. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(4), 251–260.

- Cialdini, R. B. (1993). The psychology of persuasion.

- Coakes, S., & Steed, L. (2007). SPSS Version 14.0 for Windows: Analysis without anguish. JohnWiley & Sons Australia Ltd.

- Department of Health. (2020). Australian heath sector emergency response plans for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/02/australian-health-sector-emergency-response-plan-for-novel-coronavirus-covid-19_2.docx

- Downey, J. C., & Gudmunson, C. G. (2017). Navigating an obesigenic environment: A phenomenological study of mothers’ health socialization of children. Journal of Family Issues, 38(7), 972–991.

- Ekström, K. M. (2006). Consumer socialization revisited. In Research in consumer behavior (pp. 71–98). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Francis, J., & Davis, T. (2014). Exploring children’s socialization to three dimensions of sustainability. Young Consumers, 15(2), 125–137.

- Gangwar, A., & Dewani, P. P. (2022). Secondary consumer socialisation and adoption of e-commerce: A qualitative inquiry. J. for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 14(4), 465–486.

- Gentina, E., & Muratore, I. (2012). Environmentalism at home: The process of ecological resocialization by teenagers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(2), 162–169.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Harris, F., Gordon, R., MacKintosh, A. M., & Hastings, G. (2015). Consumer socialization and the role of branding in hazardous adolescent drinking. Psychology & Marketing, 32(12), 1175–1190.

- Health Intelligence Unit. (2020). Population statistics. Provided by Western NSW Local Health District, www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Research-and-Demography/Population-projections/Projections.

- Higgins, J. W., Cookson, S., Hastings-James, C., & Frazer, A. (2012). Redeeming behaviours: A push, not a shove. HealthcarePapers, 12(4), 42–47.

- John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183–213.

- Kamenidou, I., Stavrianea, A., & Liava, C. (2020). Achieving a Covid-19 free country: Citizens preventive measures and communication pathways. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4633.

- Khodayari, R., Jafari, H., Torkzadeh, L., & Azimzadeh, S. (2020). Investigation of health socialization status in Iran: A qualitative study in 2020. Journal of Community Health Research, 9(3), 172–183.

- Lawrence, J., Lock, M., Kleinschafer, J., Naden, P., Gibbs, C., Gordon, J., & Burmeister, O. K. (2023). Value Co-Creation: For respectful research with Aboriginal Australians. International Journal of Market Research, 65(2-3), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/14707853221139700

- Lee, M., & Hong, J. (2016). Semantic network analysis of government’s crisis communication messages during the MERS outbreak. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 16(5), 124–136.

- Lee, B., Salmon, C. T., & Paek, H.-J. (2007). The effects of information sources on consumer reactions to direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug advertising: A consumer socialization approach. Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 107–119.

- Lees, N. B., & Tinsley, B. J. (2000). Maternal socialization of children’s preventive health behavior: The role of maternal affect and teaching strategies. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, (1982), 46(4), 632–652.

- Liu, H., Liu, W., Yoganathan, V., & Osburg, V.-S. (2021). COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120600.

- Malhotra, N. K., Hall, H., Shaw, M., & Oppenheim, P. (2006). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Prentice Hall.

- Mikeska, J., Harrison, R. L., & Carlson, L. (2017). A meta-analysis of parental style and consumer socialization of children. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(2), 245–256.

- Mishra, A., & Maity, M. (2021). Influence of parents, peers, and media on adolescents’ consumer knowledge, attitudes, and purchase behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1675–1689.

- Mohammed, M., Sha’aban, A., Jatau, A. I., Yunusa, I., Isa, A. M., Wada, A. S., Obamiro, K., Zainal, H., & Ibrahim, B. (2021). Assessment of COVID-19 information overload among the general public. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(1), 184–192.

- Moschis, G. P. (1987). Consumer socialization: A life-cycle perspective. Lexington Books.

- Moschis, G. P. (2007). Life course perspectives on consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(2), 295–307.

- Moschis, G. P., & Churchill, G. A.Jr, (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599–609.

- Mshingo, D., & Muhanga, M. (2021). Socialization and health literacy: Theories, agents, and the influence. Journal of Co-Operative and Business Studies (JCBS), 6(1), 115–128.

- North, E. J., & Kotzé, T. (2001). Parents and television advertisements as consumer socialization agents for adolescents: An exploratory study. Journal of Consumer Sciences, 29(1), 91–99.

- Ochoa, C., & Porcar, J. M. (2018). Modeling the effect of quota sampling on online fieldwork efficiency: An analysis of the connection between uncertainty and sample usage. International Journal of Market Research, 60(5), 484–501.

- Paek, H.-J., Reber, B. H., & Lariscy, R. W. (2011). Roles of interpersonal and media socialization agents in adolescent self-reported health literacy: A health socialization perspective. Health Education Research, 26(1), 131–149.

- Perez, M. E., Quintanilla, C., Castaño, R., & Penaloza, L. (2019). Inverse socialization with technology: Understanding intergenerational family dynamics. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(6), 818–826.

- Rathore, F. A., & Farooq, F. (2020). Information overload and infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 70(0), 1.

- Ratzan, S. C., & Parker, R. M. (2006). Health literacy—Identification and response. Journal of Health Communication, 11(8), 713–715.

- Rogers, K. (2020). Why did the world shut down for COVID-19 But not Ebola, SARS or swine flu. FiveThirtyEight, April 14, 2020. fivethirtyeight.com.

- Sengupta, S., & Wang, H.-M D. (2014). Information sources and adoption of vaccine during pandemics. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 8(4), 357–370.

- Sheppard, A. G. (1996). The sequence of factor analysis and cluster analysis: Differences in segmentation and dimensionality through the use of raw and factor scores. Tourism Analysis, 1(1), 49–57.

- Tagliacozzo, S., Albrecht, F., & Ganapati, N. E. (2021). International perspectives on COVID-19 communication ecologies: Public health agencies’ online communication in Italy, Sweden, and the United States. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(7), 934–955.

- Teasdale, E., & Yardley, L. (2011). Understanding responses to government health recommendations: Public perceptions of government advice for managing the H1N1 (swine flu) influenza pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(3), 413–418.

- Van Lange, P. A., Joireman, J., Parks, C. D., & Van Dijk, E. (2013). The psychology of social dilemmas: A review. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(2), 125–141.

- Wang, X., Yu, C., & Wei, Y. (2012). Social media peer communication and impacts on purchase intentions: A consumer socialization framework. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(4), 198–208.

- Ward, S., Klees, D. M., & Wackman, D. B. (1990). Consumer socialization research: Content analysis of post-1980 studies, and some implications for future work. ACR North American Advances.

- Watne, T., Brennan, L. (2011). Reciprocal consumer socialization: Implications for social marketing and sustainable consumption. Australia New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference 2011 (Proceedings. MacCarthy, Martin, ed. School of Marketing, Edith Cowan University, Perth).

- Watne, T., Lobo, A., & Brennan, L. (2011). Children as agents of secondary socialization for their parents. Young Consumers, 12(4), 285–294.

- Watne, T. A., Brennan, L., & Winchester, T. M. (2014). Consumer socialization agency: Implications for family decision-making about holidays. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(6), 681–696.