ABSTRACT

Siblings of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions (NDCs) are exposed to unique family environments and experience a range of psychosocial risk and resilience factors. Networks of self-reported risk, resilience, and neuropsychiatric variables were estimated for siblings of individuals with (n = 235) and without (n = 480) NDCs (N = 715, mean age 22.40 years, 76% female, 74% White Caucasian). The NDC group reported more depressive (g = 0.39) and anxious (g = 0.43) symptoms than controls, and 71.5% of the NDC group reported at least one neuropsychiatric diagnosis compared to 36.9% of controls. Self-reported sleep and post-traumatic stress disorders were high amongst NDC siblings. Everyday executive functioning difficulties (cognitive inflexibility, hyperactivity/impulsivity) and emotion dysregulation were the most influential transdiagnostic risk factors for poorer functioning within the NDC group network.

Siblings of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions (NDCs)Footnote1 are at higher genetic and environmental risk for poorer psychological and social adjustment (Rossiter & Sharpe, Citation2001), delayed neurocognitive development (Sharpe & Rossiter, Citation2002), more internalizing (i.e., depression and anxiety) and externalizing (i.e., hyperactivity, aggression) difficulties (Shivers et al., Citation2018;Vermaes et al., Citation2012), and more co-occurring neuropsychiatric conditions (Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al., Citation2016; Wolff, et al., Citation2022a) compared siblings of individuals without NDCs. Negative effects are reported for sibling cognitive, psychosocial, emotional, and behavioral outcomes (Kovshoff et al., Citation2017; Marquis et al., Citation2019), of small (g = 0.34 for anxiety and depression; Shivers et al., Citation2018) to medium (g = 0.56 for externalizing problems; Shivers et al., Citation2018) effect sizes between groups of siblings of persons with and without NDCs, and with large individual variability (Sharpe & Rossiter, Citation2002; Vermaes et al., Citation2012).Footnote2

Conversely, NDC siblings can and do exhibit resilience, even in the presence of genetic and environmental vulnerabilities (Kovshoff et al., Citation2017). A minority of reviews report positive outcomes, including increased empathy, prosociality, maturity, and personal growth (Leedham et al., Citation2020; Orm & Fjermestad, Citation2021; Watson et al., Citation2021; Wolff, et al., Citation2022a). Green (Citation2013) suggested siblings may be well adjusted under optimal environmental conditions (i.e., fewer risk factors), and negative outcomes are driven by interrelations between individual-level and environmental factors, rather than NDC sibling status in and of itself. Despite some promising findings, however, there remains robust evidence for higher incidence of psychiatric diagnoses in siblings of persons with NDCs compared to the general population (Lin et al., Citation2021; Marquis et al., Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2020). To support siblings, it is critical to understand the interrelations between risk and resilience factors predisposing them to, or protecting them from, mental health challenges.

Risk and resilience factors associated with sibling mental health

Risk factors are characteristics of an individual, family or the environment which increase the likelihood of a negative outcome (Kraemer et al., Citation1997; Walton & Ingersoll, Citation2015). Resilience factors are assets, resources and skills that enable one’s ability to withstand or recover from challenges in the presence of risk factors negatively impacting adjustment (Fritz et al., Citation2018; Kalisch et al., Citation2019). Examining resiliency is not to assume that siblings face adversity, but acknowledges that they are exposed to genetic, social and psychological risks for poorer wellbeing (Fisman et al., Citation2000).

Our mixed methods systematic review of self-report sibling data identified 41 risk and 24 resilience factors associated with NDC sibling mental health and functional outcomes in the literature to date (Wolff, et al., Citation2022a). Common risk factors included more difficulties of the NDC sibling (k = 13), increased worry and responsibility (k = 14), and emotion dysregulation (k = 9); the most common resilience factors were adaptive/active coping (k = 19), knowledge of NDCs (k = 13) and perceived social support (k = 12; Wolff, et al., Citation2022a). Although our systematic review identified several structural risk (peer problems, perceived stigma, lower SES; see also Marquis et al., Citation2019, Citation2020) and resilience factors (social support, sibling support group attendance; Koukouriki & Soulis, Citation2020; Pollard et al., Citation2013) which may impact mental health, the majority of studies (62 of 81) found that individual-level variables (e.g., emotion regulation, trait resilience, self-esteem) had the strongest associations with sibling wellbeing.

In the present study, we aimed to further examine the self-reported risk and resilience factors most implicated in sibling functioning theoretically and empirically derived from our reviews (Wolff, et al., Citation2022a; Citation2022b), in addition to transdiagnostic individual-level factors associated with poorer functioning in the general population which have rarely been studied in siblings to date (e.g., intolerance of uncertainty, alexithymia, everyday EF; Abramovitch et al., Citation2021).

Psychological wellbeing, self-regulation and executive functioning (EF) are inter-correlated processes contributing to multiple functional outcomes in siblings (Wade et al., Citation2015; Wolff, et al., Citation2022b). EF refers to higher order cognitive processes enabling planning, problem-solving and goal-directed regulation (Diamond, Citation2013), including cognitive flexibility, inhibition, and working memory (Friedman & Miyake, Citation2017; Miyake, Citation2000). Everyday EF difficulties are associated with poorer mental health, family functioning, and academic achievement in sibling samples from early childhood (5–7 years) to emerging adulthood (18–24 years; Seng et al., Citation2021; Wade et al., Citation2015) using parent report (Chien et al., Citation2017; Rosa et al., Citation2017) and objective neuropsychological testing (Bidwell et al., Citation2007); however, self-reported everyday EF and its relation to other risk and resilience factors and mental health has not been studied in siblings.

Self-regulation, the ability to control and inhibit behaviors and emotions, has crucial overlapping features with EF (Diamond, Citation2013). Difficulties in either domain are risk factors for childhood psychopathology and NDCs (Faustino, Citation2021). NDC siblings have genetic and environmental vulnerability to EF difficulties and emotion dysregulation from early childhood through to adolescence and adulthood (Taylor et al., Citation2019; Otterman et al., Citation2019; Wade et al., Citation2015), but few studies have examined these factors together with other factors to explore their relative proximity and influence in siblings’ mental health

Our systematic review also identified two affective theory of mind factors which may influence sibling outcomes. First, we found empathy may be protective against siblings’ self-reported anxiety and depression (Wolff, et al., Citation2022b), although the literature is inconclusive (Rum et al., Citation2022). As cognitive empathy is the affective foundation for prosociality and emotion regulation (N. M. Thompson et al., Citation2022), it is important to examine. Second, psychosocial interventions for siblings identify parent-child communication as a modifiable protective factor (Wolff et al., Citation2022a). Given findings indicating siblings of children with NDCs suppress emotions and may not communicate mental health struggles (Green, Citation2013; Lobato & Kao, Citation2002), this may be a critical factor assisting families in identifying and supporting sibling mental health difficulties (Haukeland et al., Citation2020).

The above risk and protective factors may be influenced by individual-level sibling traits (Lynch et al., Citation2021). In terms of dispositional, transdiagnostic risk factors for psychopathology, intolerance of uncertainty is associated with anxiety, emotion dysregulation, phenotypic presentations of autism (Jenkinson et al., Citation2020), and psychiatric disorders (McEvoy et al., Citation2019). For siblings of children with NDCs, uncertainty is common (Wolff et al., Citation2022a), hence this may contribute to poorer wellbeing and self-regulation. Alexithymia, the ability of an individual to accurately process emotional states, is also a transdiagnostic risk factor (D. A. Preece et al., Citation2022; G. J. Taylor & Bagby, Citation2020), yet has not been studied in NDC siblings despite evidence that higher alexithymia may inhibit efficacy of psychosocial interventions (Leweke et al., Citation2009).

Finally, findings on demographic variables impacting sibling mental health are inconsistent, with some suggestion that structural factors (such as family socioeconomic disadvantage or minority status ethnicity) may negatively influence sibling wellbeing (Green, Citation2013; Hayden et al., Citation2019; Marquis et al., Citation2019; Wolff et al., Citation2022b), while other meta-analyses find little or no effect of gender, age, birth order, or type of NDC on psychopathology (Shivers et al., Citation2018; Vermaes et al., Citation2012).

Gaps in the literature

Findings to date remain inconclusive regarding the interactions between self-reported psychological and cognitive risk or resilience factors and sibling wellbeing, and the role of demographic variables, if any, in influencing these outcomes (Petalas et al., Citation2009; Walton & Ingersoll, Citation2015). Several limitations remain. First, no study has yet examined a range of self-reported transdiagnostic psychological, executive functioning, and self-regulation variables together and their interrelations. Second, most studies to date have relied on caregivers as informants. Third, no studies identified in our systematic review examined both dimensional mental health (i.e., scale-based, often sub-clinical, symptoms) and categorical diagnoses (e.g., self-reported DSM-5-TR specific diagnoses). Understanding the types of mental health conditions experienced by siblings provides insight into possible interventions and support services. Finally, the literature on siblings has been dominated by a focus on risk; including resilience-promoting factors may open new avenues for understanding sibling adaptive processes (Stallworthy & Masten, Citation2022).

Objectives of the present study

The present study sought to examine the interrelations between individual-level risk and resilience factors, and their associations with categorical and dimensional mental health indicators as self-reported by NDC siblings, compared to siblings of individuals without NDCs. We position variables within an adapted dynamic bioecological framework (Borsboom, Citation2017; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1995), and posit that sibling psychological development is a complex system of interrelations of direct and indirect risk and protective factors across contexts.

To examine these interrelations, we used a probabilistic graphical model approach known as network psychometrics (Epskamp & Fried, Citation2018). This approach explores interrelations in the same model (Epskamp & Fried, Citation2018) and presupposes that a clinical condition is composed of co-occurring characteristics and presentations which causally reinforce one another within a system consisting of components (nodes) and unique relations between variables (edges; Borsboom et al., Citation2021). This analysis can be used to identify central symptoms of a psychological construct to be targeted in prevention and intervention efforts (McNally, Citation2021). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first network estimation of self-reported transdiagnostic individual-level risk and resilience factors and mental health indicators for NDC siblings.

The current study had three aims and corresponding hypotheses.

To compare mean levels of individual risk and resilience factors and mental health indicators in siblings of individuals with and without NDCs (the control group).

To estimate and compare networks of these risk and resilience factors and scale-based mental health indicators for groups of siblings of individuals with and without NDCs.

To explore which demographic variables impacted the structure (i.e., direction and density of associations) of the overall networks.

Hypotheses

Aim 1 (H1)

Siblings of persons with NDCs would have higher levels of risk factors, lower levels of resilience, and poorer mental health than siblings of persons without NDCs.

Aim 2 (H2)

Resilience factors would be interrelated within networks, and positively associated with better mental health. Risk factors would be strongly related within networks, and positively associated with poorer mental health. Although resilience factors will be related to each other in both groups, the NDC and control group networks will be dissimilar in structure, and the NDC group will have stronger edge weights (stronger associations) between risk factors. Specifically, based on the existing literature, we hypothesize siblings of children with NDCs will have poorer EF, self-regulation, and wellbeing than control siblings, and therefore their networks will be characterized by stronger connections between risk factors, and fewer resilience factors compared to the group of siblings without NDCs. This is turn will be associated with higher levels of poor mental health indicators.

As our third aim was exploratory, no specific hypotheses were made given the conflicting findings in existing literature.

Methods

This research was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant (1184770) and ethical approval was granted by the Human Ethics Office at The University of Western Australia (2020/ET000049).

Survey design

We adopted a participatory approach in which members of a Sibling Advisory Panel were involved in the design and piloting of our survey. The Sibling Advisory Panel, who were compensated for their time, were recruited via the authors’ study webpage on the Institute host website and attended four Zoom meetings. Siblings under age 13 were required to attend with a parent/caregiver. Their feedback led to minor language changes and a modified survey for children under age 13.

Participants & procedure

Participants were required to be at least eight years of age and have at least one sibling. We chose this age range as many mental health conditions have their onset during adolescence. The participants could not themselves have a diagnosed NDC. Participants were recruited through the authors’ Institute and University e-mail and social media pages, the University community and student recruitment pool, and through a professional recruitment service which aimed to maximize diversity in the sample (Qualtrics Panels). Participants were directed to an online survey via Qualtrics, and entered into a monthly prize draw for AUD$100 across three months.

Measures

Our risk and resilience variables were informed by our systematic review (Wolff et al., Citation2022a). Measures were organized into: a) mental health indicators, b) risk variables, or c) resilience variables.

Mental health indicators

Anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Citation2006). The 7-item GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., Citation2006) measures worry and anxiety symptoms over the past two weeks. Scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), greater scores indicate more anxiety. The CR) in our sample was 0.92 in both groups.

Depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Citation2001). The 9-item PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) measures depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Scored on a 4-point Likert response, with each item scored 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), higher scores indicate greater depression severity. The CR was 0.90 (NDC) and .92 (control).

Other self-reported diagnoses. Dichotomous sibling self-reported current mental health diagnoses were coded as present ( = 1) or not present ( = 0)

Overall wellbeing (Satisfaction with Life Scale, SWLS; Diener et al., Citation1985). The 5-item SWLS assesses an individual’s global judgment of their life satisfaction using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores representing stronger life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation1985). The CR was 0.81 (NDC) and 0.87 (control)l.

Risk variables (high levels of the following)

Everyday executive functioning

Cognitive inflexibility (Detail and Flexibility Questionnaire, DFlex; Roberts et al., Citation2011). The DFlex is a 24-item scale consisting of two subscales measuring cognitive rigidity and attention to detail. Each item is score on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more inflexibility. An abbreviated unidimensional scale of 15 items was used. The CR was 0.82 (NDC) and 0.86 (control).

ADHD traits (Youth Externalizing Behavior Screener, YEBS; Arslan, Citation2019). The YEBS 12-item self-report measure composed of three subscales: conduct problems (CP), hyperactivity (HA), and attention problems (AP). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always), with higher scores representing more difficulties. We used the AP and HA sub-scales. The CRs for HA were 0.82 (NDC) and 0.83 (control), and for AP, 0.91 (NDC) and 0.94 (control).

Autistic traits (Autism Quotient, AQ-10; Allison et al., Citation2012). The AQ-10 is a 10-item measure designed to screen for autistic traits, with scores ranging 1–10 and higher scores indicating more autistic traits (Allison et al., Citation2012). The CR was 0.70 (NDC) and 0.81 (control).

Self-Regulation

Emotional reactivity (Perth Emotional Reactivity Scale Short Form, PERS-S; D. Preece et al., Citation2019). The PERS-S is an 18-item scale measuring emotional reactivity. Items are scored on a 5 point Likert scale from 1 (very unlike me) to 5 (very like me). Higher scores represent greater emotional reactivity (Preece, Becerra & Campitelli, Citation2019). We used the Positivity (PERS-P; resilience factor) and Negativity (PERS-N; risk factor) subscales. The CRs for PERS-P were 0.92 (NDC) and 0.94 (control); for PERS-N, 0.91 (NDC) and 0.92 (control).

Alexithymia (Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire, PAQ; D. Preece et al., Citation2019). The PAQ is a 24-item self-report measure of alexithymia. Scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), higher scores represent more problems with alexithymia. We used a 10-item short-form of the scale. The CR was 0.91 (NDC) and 0.94 (control).

Psychological

Intolerance of uncertainty (Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale Short Form, IUS-12; Carleton et al., Citation2007). The IUS-12 was designed to assess evaluate emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to uncertain situations (Carleton et al., Citation2007). The 12 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (entirely characteristic of the participant), with higher scores indicating greater intolerance of uncertainty. The CR was 0.93 (NDC) and 0.95 (control).

Resilience variables (high levels of the following)

Self-Regulation

Emotion regulation (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, ERQ; Gross & John, Citation2003). The ERQ is a 10-item measure of two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal (ERQ-C) and expressive suppression (ERQ-E). We hypothesized that high ERQ-C would be a resilience factor while high ERQ-E would be a risk factor. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater use of the strategy. High scores on expressive suppression and/or lower scores on cognitive reappraisal indicate emotion regulation problems. The CRs for ERQ-C were 0.89 (NDC) and 0.92 (control); for ERQ-E, 0.80 (NDC) and 0.84 (control).

Psychological

Trait Resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10; CDRS; Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). The CDRS is a 10-item scale measuring trait resilience, with items scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time). Higher scores indicate greater resilience. The CR was 0.91 (NDC) and 0.93 (control).

Self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, RSES; Rosenberg, Citation1965). The RSES is a 10-item scale, with items scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with five items reverse coded. The CR was 0.90 (NDC) and 0.92 (control).

Empathy (Adolescent Measure of Empathy and Sympathy, AMES; Vossen et al., Citation2015). The AMES is a 12-item scale consisting of two subscales: empathy and sympathy. The items are scored on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher scores indicating greater empathy and/or sympathy. We used the composite full-scale score. The CR was 0.83 (NDC) and 0.92 (control).

Parent-Sibling Communication (Parent – Adolescent Communication Scale, PACS; Barnes & Olson, Citation1985). The PACS measures the quality of parent-child interactions and communication with reference to at least one parent/caregiver in the participants’ life. It consists of ten items scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scored indicating better parent-child communication quality. The CR was 0.96 for both groups.

Analysis plan

Code for the analyses is available on the first author’s OSF page: https://osf.io/u4gaj. All analyses used R software, version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, Citation2022).

Power analysis

Sample size simulations for the networks were implemented in R following the approach proposed by Constantin (Citation2021), indicating the total sample size should be at least 659 respondents.

Data preparation

The data extracted from Qualtrics initially consisted of 1486 respondents. Pairwise deletion was conducted for any participant completing 50% or less of the survey (n = 325) and for those with<5 minute completion times (n = 323), resulting in n = 838. Participants with>20% missing total data were removed (n = 123). We did not use multiple imputation for these 123 participants, as missing data included demographics, which prevented us from categorizing these siblings into NDC or control groups, in addition to scale-based missing data, which is not recommended to impute for>20% missing (Dong & Peng, Citation2013). The final sample was 715 participants (235 siblings of persons with NDC and 480 controls).

Correlations between percentage missing data per item were evaluated, and the assumptions of missing at random were met (Rubin, Citation1976). Multiple imputation was used to reduce missing data bias; k nearest neighbor was applied with three nearest neighbors (Beretta & Santaniello, Citation2016).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and mean group differences

Key descriptive statistics were calculated for the control and NDC group. Mean group differences were also evaluated with Welch’s t tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for Hedge’s g effect size were calculated.

Structural validity, reliability and sum Scores

All scales and subscales were tested for their structural validity using confirmatory factor analysis (B. Thompson, Citation2004), using the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares method (WLSMV; DiStefano & Morgan, Citation2014). Composite reliability (CR; Peterson & Kim, Citation2013) assessed the measures’ internal consistency.

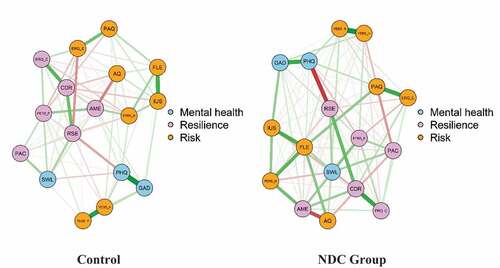

Network analyses

To examine Aim 1, Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) were estimated using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regularization (Epskamp & Fried, Citation2018). Network accuracy (i.e., confidence intervals for regularized partial correlations) and stability (i.e., post-hoc power analyses) were estimated using bootstrap methods (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). Psychometric network models consist of nodes (circles) representing variables or symptoms, and edges (lines) representing associations between the nodes (i.e., partial correlations given all other nodes in the network) (Borsboom, Citation2017). Partial correlations reflect conditional dependence (i.e., after adjusting for all other nodes, the relation between two nodes is not due to another node in the network) (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). Interactions between factors were visualized using qgraph (Epskamp et al., Citation2012), with stronger associations located at the center (Fruchterman & Reingold, Citation1991). A positive edge (green) indicates that an increase in activation of one node is associated with an increase in activation of the connected node; a negative edge (red) indicates that an increase in the first node is associated with a decrease in the second node.

Measures of centrality and bridge centralities

Centrality statistics assessed the relative importance of each variable in the model (Hevey, Citation2018) including: (i) strength (the direct influence a variable has on the network as the sum of the absolute partial correlations connected to a given variable); (ii) closeness (the average length of the shortest path between a given variable and all other variables in the model); (iii) betweenness (the number of times a variable mediates the shortest path between two other variables); (iv) expected influence (the direct influence a variable has on the network); and (v) network predictability (the variance explained by the other variables in the model). We calculated indices of “bridge” centrality (Jones et al., Citation2021) to evaluate how strongly a specific node connected subgroups of variables, including: (i) bridge strength; (ii) bridge betweenness; (iii) bridge closeness; and (iv) bridge expected influence.

To examine Aim 2, we used the Network Comparison Test (NCT; Van Borkulo et al., Citation2017) to compare GGMs for individuals with or without a sibling with an NDC. We calculated: (i) edge invariance (i.e., if partial correlations are different based on group); (ii) closeness, betweenness, strength, and expected influence invariance (i.e., if these centrality statistics are different based on group); (iii) maximal edge weight difference (i.e., comparing partial correlations based on grouping variable); (iv) global network strength (i.e., if the absolute sum of the differences of the absolute partial correlations depends on group); and (v) Jensen – Shannon divergence.

For exploratory analyses of Aim 3, we included eight categorical demographic variables (participant age and gender, sibling gender and age, ethnicity, parental divorce, income, and parental NDC status) as predictors in a conditional inference tree network approach (CTree; Jones et al., Citation2020). The CTree approach has four steps: (i) fit a GGM to the subsample (using the full sample in the first iteration); (ii) compute fit statistics based on the log-likelihood of a multivariate normal distribution; (iii) test (using p-values) whether the fit statistic is affected by any predictor; and (iv) find the split that yields the highest improvement of the fit statistic. This was tested using the full sample due to limited power. As a further exploratory analysis, we conducted four classical multiple regression models to examine if the demographic variables predicted mental health outcomes.

Results

Participant characteristics

Demographic characteristics of participants are presented in (see Table S1 for characteristics of their siblings). For NDC diagnoses, the most common diagnosis was autism either alone or co-occurring with ADHD, cerebral palsy, or intellectual disability.

Table 1. Demographics of participants.

Comparison of individual risk and resilience factors and mental health indicators in siblings of individuals with and without NDCs

For self-reported mental health diagnoses (dichotomous yes/no variable), 71.5% (168 of 235) of the NDC group siblings and 36.9% (177 of 480) control participants reported at least one mental health diagnosis (see Table S2), the most common for both groups being anxiety (58.3% NDC; 29.58% control group). Sleep disorders co-occurred with other mental health conditions in 34 NDC siblings (20.24% of mental health cases), compared to 10 in the control group (5.65% of mental health cases).

Group comparisons of risk and resilience variables are presented in Table S3. All comparisons, other than expressive suppression (ERQ-E), were significant. The NDC group had higher mean levels of dimensional (scale-based) mental ill health indicators (depression and anxiety; g = 0.39 and 0.43 respectively). The NDC group had significantly higher mean levels of risk factors and lower levels of resilience factors. Effect sizes for group differences ranged from small (g = −0.09 for ERQ-E) to moderate (g = −0.43 for anxiety).

Estimation of networks of risk and resilience factors and mental health indicators for siblings of individuals with and without NDCs

The GGMs estimated for both groups are presented in (A: control group; B: NDC group). These results were robust to stability and accuracy tests. (Appendix G). Overall, when examining the strongest relations between specific risk and resilience factors and the three mental health indicators in the NDC group, anxiety was positively associated with intolerance of uncertainty, positive emotion reactivity, autistic traits, and hyperactivity; depression was negatively associated with self-esteem, positive emotion reactivity, and autistic traits, and positively associated with negative emotion reactivity and alexithymia. In the control group, anxiety was positively associated with hyperactivity and attention problems, and depression was negatively associated with self-esteem. The NDC group had the densest network, indicating stronger conditional correlations between risk factors and mental ill health. In the NDC group, one EF variable central to the NDC network (cognitive inflexibility) was strongly associated with poorer self-regulation (negative reactivity, alexithymia) and with poorer mental health. See Tables S4 and S5 for conditional partial correlations for both groups. Age as a dimensional variable was tested in the GGM but had no significant partial correlations and did not alter the structure or density of the GGM of either group.

Figure 1. The GGM estimated for the subsamples, on the left (A) is the control group and on the right (B) is the NDC sibling group.

Group centralities are presented in ; centrality statistics are in Tables S6 and S7). For the NDC group, cognitive inflexibility had the highest strength, betweenness, and expected influence; hyperactivity/impulsivity the highest closeness. Life satisfaction had the highest bridge strength, cognitive inflexibility the highest bridge betweenness and closeness, and the autistic traits the highest bridge (negative) expected influence. For the control group, self-esteem consistently had the highest indices. For both groups, self-esteem had the highest predictability, with 80.6% and 70.3% variance explained by all other nodes in the network in the NDC and control groups respectively.

Figure 2. Measures of centrality for the GGMs estimated for the subsamples, on the left (A) is the control group and on the right (B) is the NDC sibling group.

Key: GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; PHQ: depression; SWL: life satisfaction; YEBS-H: hyperactivity/externalizing behavior; YEBS-A: attention difficulties; AQ: autistic traits; FLE: cognitive inflexibility; PAQ: alexithymia; PERS-P: positive emotion reactivity; PERS-N: negative emotion reactivity; ERQ-C: cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation; ERQ-E: expressive suppression emotion regulation; IUS: intolerance of uncertainty; CDR: trait resilience; RSE: self-esteem; AME cognitive empathy; PAC: parent-child communication quality.

The network comparison test found significant differences in conditional correlations for several associations (Table S8). Note that many conditional correlations were set to zero in the control group due to the LASSO method. The NDC group had significantly stronger negative conditional correlations than the control group for self-esteem and depression, and stronger positive association for anxiety and positive emotion reactivity. The NDC group had significantly higher cognitive inflexibility closeness, betweenness, and strength, and expressive suppression closeness, strength and expected influence.

Exploration of demographic variables impacting the structure of the overall network

The CTree identified predictive effects for participants’ gender and parental divorce (; Table S9). The densest network (i.e., the network in the right side of ) is the network estimated for trans and non-binary respondents (n = 23), indicating highly inter-related risk and mental ill health indicators. The other two networks were estimated for respondents that identified as male or females, for which the networks conditional upon whether their parents were divorced (branch = 0 for not divorced or 1 for divorce), where the network was denser with highly related risk factors for siblings of divorced parents. Age as a categorical variable did not have any impact (Table S10).

In the regression analyses, non-conforming gender, NDC group, parental NDC, and parental divorce, significantly predicted greater likelihood of categorical mental health diagnoses (see Appendix B for regression results). NDC group membership and lower income predicted both greater anxiety and depressive symptoms. NDC group membership, nonwhite ethnicity, participant older age, lower income, and non-conforming participant gender predicted poorer life satisfaction. These variables contributed minimal variance (i.e., 8.1–10.4%) to the models.

Discussion

This study aimed to characterize networks of individual-level and demographic risk and resilience factors and their interrelations with self-reported mental health in siblings of individuals with and without NDCs. There were four key findings. First, the NDC group had significantly poorer mental health, greater levels of risk factors, and lower levels of resilience factors than the control group. Second, the NDC group significantly differed from the controls in network structure and density, with stronger connections between risk variables and mental ill health. Third, EF and emotion dysregulation were the transdiagnostic factors differentiating the two groups, with cognitive flexibility and expressive suppression being central to the NDC siblings’ network. Fourth, the network structure was minimally impacted by categorical demographic variables, although weak effects were noted for siblings with divorced or separated parents, and participants identifying as gender diverse, and we did not find any developmental effects of age on network structure or mental health.

Comparison of risk and resilience factors and mental health indicators for siblings of individuals with and without NDCs

Our study is the first to examine both dimensional and categorical self-reported mental health difficulties in siblings of persons with NDCs across developmental stages, compared to a large and representative control group. The most robust finding was the inequality of neuropsychiatric problems in the NDC group. Our study found similar effect sizes for group differences in anxiety as a previous meta-analysis of siblings of autistic children (g = 0.34; Shivers et al., Citation2018) and of children with intellectual disability (d = 0.20 for anxiety, 0.55 for depression; Rossiter & Sharpe, Citation2001) compared to controls. The control group had higher levels of resilience factors, with the largest effect size for adaptive emotion regulation. NDC siblings self-reported poorer scores on all domains of executive functioning (attention, inhibition, cognitive flexibility), theory of mind (empathy, which contradicted recent evidence from Orm & Fjermestad, Citation2021; and interpersonal relationships) and self-regulation. A further finding of the current study was higher levels of co-occurring conditions in the NDC group (particularly sleep disorders) than controls, suggesting siblings’ mental ill health may be related to transdiagnostic risk factors examined which are common to many psychiatric disorders (Sloan et al., Citation2017). Siblings’ psychological dispositions, cognitive flexibility, and adaptive emotion regulation strategies may therefore be predictors of resilience (Schleider & Schroder, Citation2018). Chronic stress over time experienced by the NDC sibling group may contribute to vulnerability to psychopathology during important developmental periods, moderated by difficulties in emotion regulation, and executive functioning (Compas et al., Citation2017). As expected, siblings in the NDC group had significantly more self-reported autistic traits and ADHD symptoms than the controls.

Estimation of networks of risk and resilience factors in the NC and control sibling groups

In the NDC group, cognitive inflexibility had the highest of most centrality indices, hyperactivity/inhibition problems had the highest closeness index, and autistic traits had the highest negative influence, suggesting difficulties with everyday EF is a central feature of the network. Contrary to our hypothesis and prior literature (Frank & Davidson, Citation2014), our other EF risk variables, attention problems and intolerance of uncertainty, were relatively unimportant when all factors were considered together in the network. In the control group, self-esteem had the overall highest centrality indices, suggesting a lesser role of EF and self-regulation, and a more central role of individual psychological characteristics. The NCT indicated stronger negative associations in the NDC group, particularly for higher depression associated with lower self-esteem. The pattern of significant network group differences suggests a varying role of risk factors on mental health between the two sibling groups; specifically, the activation of a risk factor node in the NDC network results in a stronger activation (increase or decrease) of the connecting node than in the control group.

Relations between risk and resilience factors and mental health variables

The mental health indicators (anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction) were all associated with positive emotion reactivity and self-esteem, and anxiety and depression were positively associated with autistic traits and hyperactivity/impulsivity in the NDC group, with a similar but weaker pattern observed in the control group. Importantly, the most central and bridge variable in the GGM (i.e., cognitive inflexibility) had weak partial correlations with the mental health indicators, although other central variables (e.g., autistic traits, hyperactivity/inhibition) had marginally stronger partial correlations; this suggests that it is likely the interaction of multiple risk factors mutually reinforcing each other which contributes to lower wellbeing (Kalisch et al., Citation2019), and siblings’ likelihood of poorer mental health increases as risk factors accumulate and interact (Evans et al., Citation2013).

Interrelations between risk and resilience factors

Empathy and alexithymia had low centrality in both networks. This may to some extent be due to the measures used, and reflect response bias more than other variables; alternatively, participants may have reduced insight into these traits (Brett & Maybery, 2022; McKenzie Smith et al., Citation2018). A strong negative association emerged between participant autistic traits and parent-sibling relationship in the NDC group, which was significantly stronger than in the control group; this suggests an association between subclinical autistic traits in siblings and poorer interpersonal relationships, and perhaps reflects the effect of maternal autistic traits (H. -W.J. Tsai et al., Citation2016; H. J. Tsai et al., Citation2017). Cognitive inflexibility was positively associated with self-esteem in the control group, while this association was negative and weaker in the NDC group; this suggests cognitive inflexibility may have acted as a resilience factor in the control group perhaps due to its lower mean level. The higher mean levels of ADHD symptoms and autistic traits in the NDC group compared to controls may have contributed to the centrality of EF and self-regulation difficulties observed in the NDC sibling network given these are known risk factors for poorer functional and mental health (Stallworthy & Masten, Citation2022).

The role of demographic variables in impacting the structure of the networks

Contrary to our hypothesis, many of our selected demographics did not predict network variation. Only non-conforming gender of the participants or having divorced parents predicted network variation. These results suggest that the individual-level risk and resilience factors comprising our estimated networks are generally stable, irrespective of demographic variation across a wide age range; that the effects are smaller than our sample size can detect; or our self-reported demographics are unreliable. We also conducted multiple regression analyses to examine if demographic variables may predict individual mental health outcomes. Similar to the CTree, demographic variables had minimal impact on mental health. However, it was consistently found that greater income predicted better mental health, when adjusting for all other demographic variables. Non-confirming gender tended to predict poorer mental health, as did parental divorce. Previous reviews and population-based studies (Marquis et al., Citation2019; Wolff et al., Citation2022b) found multiple demographic factors impacting sibling mental health. However, other meta-analyses report no such effects (Sharpe & Rossiter, Citation2002; Vermaes et al., Citation2012). It may be that worse outcomes are driven by interactions and accumulation of multiple individual and demographic risk factors (Evans, Citation2013).

Clinical implications

Four clinical implications may be derived from these findings. First, siblings of individuals with NDCs should be considered an at-risk population for clinical or subclinical mental health problems. Second, as a group, siblings of individuals with NDCs had significantly poorer EF, self-regulation and fewer psychological protective factors as compared to the siblings of individuals without NDCs. Hence, it is possible that these key transdiagnostic variables are modifiable factors with potentially strong impact on overall mental health. Importantly, these risk factors mutually reinforced one another, leading to a cumulative effect of poorer mental health. Therapeutic interventions targeting these factors may benefit siblings, given evidence from network analyses that changes in central symptoms of depression and anxiety predict changes in other symptoms (Kaiser et al., Citation2021; Rodebaugh et al., Citation2018) and that such bridge symptoms may maintain co-occurring health conditions (Fried et al., Citation2017).

Our systematic review on interventions for siblings of persons with NDCs found overwhelmingly that interventions tend to focus on improving knowledge of NDCs, parent-sibling relationship, and self-esteem (Wolff et al., Citation2022a), with little focus on individual-level internal processes. Multi-modal EF interventions can improve children and adolescents’ (ages 4–18) academic achievement, and emotional and social development (Day et al., Citation2022; Diamond & Ling, Citation2016; Diamond, Citation2012; Gill et al., Citation2018). Further, EF can be improved across development with sustained benefits (Diamond & Ling, Citation2016). Emotion-regulation individualized therapy has similarly been found to improve motivational mechanisms and behavioral responses in both adolescents and adults (Iovino et al., Citation2021; Renna et al., Citation2017). Importantly, however, psychiatric disorders such as depression are known to impair EF performance, specifically being theorized to cause deficits in shifting abilities (Shepard et al., Citation2022; Warren et al., Citation2021). Given the high rate of psychiatric diagnoses in this sample, it is also possible that the EF problems exhibited by the NDC sibling group are, at least in part, attributable to mental health difficulties. We also suggest that interventions consider contextual and psychosocial factors such as providing a more enabling and supportive environment for siblings and holistic family support, in addition to addressing individual-level emotional, social and physical factors which can impair EF (Diamond & Lee, 2016). Further, there was a high self-reported co-occurrence of sleep disorders and PTSD in our sibling sample; these two conditions are widely known to maintain and exacerbate other mental health and EF problems in children through to adults (Brady et al., Citation2000; Fairholme et al., Citation2013; Hestetun et al., Citation2018), hence we encourage the screening of siblings for such co-occurring difficulties.

Third, siblings of individuals with NDCs experience high levels of subclinical but elevated NDC symptoms, which interact with and may reinforce other risk factors, impacting mental health through both genetic vulnerability and cross-aggregation of NDCs (Miller et al., Citation2019) as well as environmental factors (Green, Citation2013). Early identification and holistic support for these difficulties may benefit siblings’ social and cognitive development, as is evidenced in preemptive support for parents and siblings of autistic children, and early naturalistic developmental interventions which improve developmental outcomes in younger siblings (<4 years) of autistic children (Douglas, Citation2019; Franz et al., Citation2022). Holistically, identifying siblings’ self-reported EF difficulties which may place them at risk of needing mental health support may enable provision of educational, psychological and family supports for their wellbeing (Haukeland et al., Citation2020). We acknowledge that although we did not find any impact of age in our sample, some targeted interventions may be more helpful for younger siblings (McKenzie Smith et al., Citation2018) and more research is needed into supporting older siblings’ wellbeing (Orsmond & Fulford, Citation2018).

Finally, there are certain demographics (i.e., income, parental divorce) which appear to have an amplified negative impact on siblings of persons with NDCs (Marquis et al., Citation2019). Targeted support programs and access to services and financial support for families exposed to structural risk variables may reduce or prevent the accumulation of other individual-level risk factors in siblings (Green, Citation2013; Haukeland et al., Citation2020). It is important to consider family factors in the design of any individual-level intervention due to possible ripple effects, such as parental stress and family cohesion (Giallo & Gavidia-Payne, Citation2012).

We acknowledge that the incidence of mental health diagnoses has increased globally since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020 (Santomauro et al., Citation2021); up to 30.5% of adolescents (ages 4–17 years) have newly emerged emotional or behavioral problems (Sicouri et al., Citation2023). Rates of self-reported psychiatric condition diagnoses amongst our participants are greater than current estimates of mental health disorders in the general population globally during COVID-19 (i.e., 50% for psychological distress, Nochaiwong et al., Citation2021). Hence, our mental health indicators are reflecting psychological states during the pandemic. However, the pandemic disproportionately impacts individuals with existing mental health diagnoses and families impacted by NDCs (Asbury et al., Citation2021; Montirosso et al., Citation2021). Future longitudinal research may provide more comprehensive insight into the developmental, cognitive, psychological, and social impact of the pandemic on siblings of persons with NDCs.

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of self-report measures as proxies for EF rather than experimental tasks (Howlett et al., Citation2022), as self-report measures can, in general, be prone to social desirability bias, shared method effects, misunderstanding of items, and limited self-awareness (Rosenman et al., Citation2011). Conversely, some evidence suggests self-report measures of EF may be more sensitive to everyday EF difficulties (Uddin, Citation2021) and as such, using self-report may contribute to improved ecological validity (Albein-Urios et al., Citation2018). We also note our choice of scale may not have captured cognitive empathy, and inconsistencies across studies may be due to the varying operationalizations and measures used (Rum et al., Citation2022).

We could not validate the self-reported mental health diagnoses and NDCs reported by our participants, although some evidence suggests siblings tend to under-report mental health difficulties (Rankin et al., Citation2017). Many NDC siblings self-reported multiple mental health diagnoses, and as such, the combined rates of any self-reported psychiatric diagnoses were higher than current global estimates of individual psychiatric conditions (Kessler et al., Citation2012). Future studies may consider telephone interviews to screen for or assess psychiatric status, or reviews of medical records to confirm NDCs. The self-selecting nature of the online survey may also have biased estimates. However, given that mental ill health and co-occurring conditions are the norm rather than the exception amongst NDC siblings (Shivers et al., Citation2018), including all participants may have in fact improved the ecological validity of our study. We also acknowledge that this high prevalence of mental health conditions may not reflect the experiences of all NDC siblings, consistent with our findings that some siblings do demonstrate positive outcomes and resiliency (Wolff et al., Citation2022a).

Most participants were from Australia (83.50%), were White (73.85%), female (76.22%) and from middle-upper income backgrounds (51.48%), which limits generalizability. Representativeness was also influenced by our recruitment methods and those with access to our advertising campaign. There is also the potential for bias where parents assisted younger siblings with the survey, and reduced reliability of younger aged siblings reporting on demographics such as income. We further had large amounts of missing demographic data; lacking this contextual and situational information may have introduced unmeasured confounders associated with sibling wellbeing (Shivers et al., Citation2018).

Methodologically, centrality statistics should be interpreted with caution, given they are derived only from the variables included in the network and assume that latent confounding is not present (Hallquist et al., Citation2021). In addition, as with any network analysis, we were limited by our item and construct selection. We cannot make inferences about causality; future follow-up studies are needed to explore directionality and developmental stages in siblings. In particular, the temporal association between mental health difficulties and executive dysfunction is unclear; however, both EF training and mental health support may beneficially impact this bidirectional relation (Shepard et al., Citation2022). We acknowledge significant differences on several baseline variables between groups; however, this does not preclude examination of covariance matrices and network comparison tests (Borsboom, Citation2017). It is not methodologically feasible to obtain matched samples given the known greater prevalence of mental health difficulties and environmental risk factors impacting siblings of persons with NDCs compared to the general population (Jokiranta-Olkoniemi et al., Citation2016).

This study included siblings of children with any NDC, assuming some commonalities across NDCs. Sibling mental health may be NDC-specific (Kirchhofer et al., Citation2022) or indeed severity specific (Wolff et al., Citation2022a); categorization may be required to better understand sibling risk factors and supports (Tudor & Lerner, Citation2015). Finally, we cannot make conclusions regarding the resiliency of the control or NDC group. It would be inaccurate to assume the control group were more resilient than the NDC group unless risk factors were level (Kalisch et al., Citation2019). More longitudinal research into the nature of resiliency and how this can be measured given imbalanced internal and external stressors experienced by siblings is needed (Green, Citation2013).

Conclusion

Siblings of individuals with NDCs had dense networks of self-reported cognitive and psychological risk factors, namely poorer everyday EF and self-regulation, when compared to control siblings. This study is the first to examine a range of empirically supported and theoretically relevant transdiagnostic cognitive and psychological risk and resilience factors associated with mental health in siblings of individuals with NDCs and has provided key avenues for further longitudinal research and early identification and support in at-risk sibling groups.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (411.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The analytic code and participant data necessary to reproduce the analyses presented are available on the first author’s OSF page: https://osf.io/6w7ar/

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2023.2190119

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Text-Revision (DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2022) individuals with “neurodevelopmental disorders” include those with intellectual disabilities, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), specific learning disorders, communication disorders and motor disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Hereafter referred to as neurodevelopmental conditions (NDCs), NDCs are a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period, characterized by developmental delays or difficulties that contribute to impairments of personal, social, academic, or occupational functioning (APA, 2022).

2. Although different groups and individuals have different language choice preferences, this study will generally adopt person-first language to refer to siblings with neurodevelopmental conditions; for autism-related discussions, we chose to use identity-first language (i.e., autistic sibling), which reflects a increasingly common preference amongst the majority, although not all of, the autistic community (Amaral, 2023; Keating et al., 2022). This language choice in relation to siblings of autistic individuals was the preference of our Sibling Advisory Group. The term NDC sibling refers to a sibling of an individual with an NDC; individual with an NDC or autistic sibling refers to the individual in the sibling dyad diagnosed with an NDC.

References

- Abramovitch, A., Short, T., & Schweiger, A. (2021). The C factor: Cognitive dysfunction as a transdiagnostic dimension in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 86, 102007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102007

- Albein-Urios, N., Youssef, G. J., Kirkovski, M., & Enticott, P. G. (2018). Autism spectrum traits linked with reduced performance on self-report behavioural measures of cognitive flexibility. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2506–2515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3503-3

- Allison, C., Auyeung, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2012). Toward brief “Red Flags” for autism screening: The short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(2), 202–212.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.11.003

- Amaral, D. G. (2023). Language in autism research: Accurate and respectful. Autism Research, 16(1), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2886

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Arslan, G. (2019). Development and validation of the youth externalizing behavior screener: A brief and effective measure of behavioral problems. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 7(Suppl 1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2018.1466747

- Asbury, K., Fox, L., Deniz, E., Code, A., & Toseeb, U. (2021). How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(5), 1772–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2

- Barnes, H. L., & Olson, D. H. (1985). Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development, 56(2), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129732

- Beretta, L., & Santaniello, A. (2016). Nearest neighbor imputation algorithms: A critical evaluation. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16(Suppl 3), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0318-z

- Bidwell, L. C., Willcutt, E. G., Defries, J. C., & Pennington, B. F. (2007). Testing for neuropsychological endophenotypes in siblings discordant for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 62(9), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.003

- Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375

- Borsboom, D., Deserno, M. K., Rhemtulla, M., Epskamp, S., Fried, E. I., McNally, R. J., Robinaugh, D. J., Perugini, M., Dalege, J., Costantini, G., Isvoranu, A. -M., Wysocki, A. C., van Borkulo, C. D., van Bork, R., & Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 1(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-021-00055-w

- Brady, K. T., Killeen, T. K., Brewerton, T., & Lucerini, S. (2000). Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(7), 22–32.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Lüscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619–647). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10176-018

- Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. A., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014

- Chien, Y. L., Chou, M. C., Chiu, Y. N., Chou, W. J., Wu, Y. Y., Tsai, W. C., & Gau, S. S. (2017). ADHD-related symptoms and attention profiles in the unaffected siblings of probands with autism spectrum disorder: Focus on the subtypes of autism and Asperger’s disorder. Molecular Autism, 8(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0153-9

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939–991. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

- Constantin, M. A., Schuurman, N. K., & Vermunt, J. (2021). A General Monte Carlo Method for Sample Size Analysis in the Context of Network Models. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/j5v7u

- Day, N., Paas, F., Kervin, L., & Howard, S. J. (2022). A systematic scoping review of pre-school self-Regulation interventions from a self-Determination theory perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042454

- Diamond, A. (2012). Activities and programs that improve children’s executive functions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412453722

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

- Diamond, A., & Ling, D. S. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2015.11.005

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- DiStefano, C., & Morgan, G. B. (2014). A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915373

- Dong, Y., & Peng, C. Y. (2013). Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 222. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-222

- Douglas, P. S. (2019). Pre-emptive intervention for autism spectrum disorder: Theoretical foundations and clinical translation. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2019.00066

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-08621

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18.

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

- Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031808

- Fairholme, C. P., Nosen, E. L., Nillni, Y. I., Schumacher, J. A., Tull, M. T., & Coffey, S. F. (2013). Sleep disturbance and emotion dysregulation as transdiagnostic processes in a comorbid sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.014

- Faustino, B. (2021). Transdiagnostic perspective on psychological inflexibility and emotional dysregulation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 49(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000600

- Fisman, S., Wolf, L., Ellison, D., & Freeman, T. (2000). A longitudinal study of siblings of children with chronic disabilities. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 45(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370004500406

- Frank, R. I., & Davidson, J. (2014). The transdiagnostic road map to case formulation and treatment planning: Practical guidance for clinical decision making. New Harbinger Publications.

- Franz, L., Goodwin, C. D., Rieder, A., Matheis, M., & Damiano, D. L. Early intervention for very young children with or at high likelihood for autism spectrum disorder: An overview of reviews. (2022). Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 64(9), 1063–1076. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15258

- Friedman, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2017). Unity and diversity of executive functions: Individual differences as a window on cognitive structure. Cortex, 86, 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.04.023

- Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: A review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

- Fritz, J., Fried, E. I., Goodyer, I. M., Wilkinson, P. O., & van Harmelen, A. -L. (2018). A network model of resilience factors for adolescents with and without exposure to childhood adversity. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 15774. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34130-2

- Fruchterman, T. M. J., & Reingold, E. M. (1991). Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Practice & Experience, 21(11), 1129–1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/spe.4380211102

- Giallo, R., Gavidia-Payne, S., Minett, B., & Kapoor, A. (2012). Sibling voices: The self-reported mental health of siblings of children with a disability. The Clinical Psychologist, 16(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9552.2011.00035.x

- Gill, K., Thompson-Hodgetts, S., & Rasmussen, C. (2018). A critical review of research on the alert program®. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1432445

- Green, L. (2013). The well-Being of siblings of individuals with autism. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2013, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/417194, Article ID 417194

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Hallquist, M. N., Wright, A., & Molenaar, P. (2021). Problems with centrality measures in psychopathology symptom networks: Why network psychometrics cannot escape psychometric theory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1640103

- Haukeland, Y. B., Czajkowski, N. O., Fjermestad, K. W., Silverman, W. K., Mossige, S., & Vatne, T. M. (2020). Evaluation of “SIBS”, an intervention for siblings and parents of children with chronic disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(8), 2201–2217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01737-x

- Hayden, N. K., Hastings, R. P., Totsika, V., & Langley, E. (2019, Aug). A population-Based study of the behavioral and emotional adjustment of older siblings of children with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(8), 1409–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-00510-5

- Hestetun, I., Svendsen, M. V., & Oellingrath, I. M. (2018). Sleep problems and mental health among young Norwegian adolescents. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72(8), 578–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2018.1499043

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2018.1521283

- Howlett, C. A., Wewege, M. A., Berryman, C., Oldach, A., Jennings, E., Moore, E., Karran, E. L., Szeto, K., Pronk, L., Miles, S., & Moseley, G. L. Back to the drawing board—the relationship between self-report and neuropsychological tests of cognitive flexibility in clinical cohorts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. (2022). Neuropsychology, 36(5), 347–372. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000796

- Iovino, E. A., Koslouski, J. B., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2021). Teaching simple strategies to foster emotional well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 772260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.772260

- Jenkinson, R., Milne, E., & Thompson, A. (2020). The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety in autism: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Autism, 24(8), 1362361320932437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320932437

- Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, E., Cheslack-Postava, K., Sucksdorff, D., Suominen, A., Gyllenberg, D., Chudal, R., Leivonen, S., Gissler, M., Brown, A. S., & Sourander, A. (2016). Risk of Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Among Siblings of Probands with Autism Spectrum Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 622–629. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0495

- Jones, P. J., Mair, P., Simon, T., & Zeileis, A. (2020). Network trees: A method for recursively partitioning covariance structures. Psychometrika, 85(4), 926–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-020-09731-4

- Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898

- Kaiser, T., Herzog, P., Voderholzer, U., & Brakemeier, E. (2021). Unraveling the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in a large inpatient sample: Network analysis to examine bridge symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 38(3), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23136

- Kalisch, R., Cramer, A. O. J., Binder, H., Fritz, J., Leertouwer, I., Lunansky, G., Meyer, B., Timmer, J., Veer, I. M., & VanHarmelen, A. -L. (2019). Deconstructing and reconstructing resilience: A dynamic network approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(5), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619855637

- Keating, C. T., Hickman, L., Leung, J., Monk, R., Montgomery, A., Heath, H., & Sowden, S. (2022). Autism-related language preferences of english-speaking individuals across the globe: A mixed methods investigation. Autism Research. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2864

- Kessler, R. C., Avenevoli, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Green, J. G., Lakoma, M. D., Petukhova, M., Pine, D. S., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Merikangas, K. R. (2012). Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1997–2010. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000025

- Kirchhofer, S. M., Orm, S., Haukeland, Y. B., Fredriksen, T., Wakefield, C. E., & Fjermestad, K. W. (2022). A systematic review of social support for siblings of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 126, 104234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104234

- Koukouriki, E., & Soulis, S. -G. (2020). Self-reported Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) and Anxiety Among Greek School-Age Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Relation to Parental Mental Health and Social Support. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04395-6

- Kovshoff, H., Cebula, K., Tsai, H. J., & Hastings, R. P. (2017). Siblings of children with autism: The siblings embedded systems framework. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 4(2), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-017-0110-5

- Kraemer, H. C., Kazdin, A. E., Offord, D. R., Kessler, R. C., Jensen, P. S., & Kupfer, D. J. (1997). Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Leedham, A. T., Thompson, A. R., & Freeth, M. (2020). A thematic synthesis of siblings’ lived experiences of autism: Distress, responsibilities, compassion and connection. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97, 103547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103547

- Leweke, F., Bausch, S., Leichsenring, F., Walter, B., & Stingl, M. (2009). Alexithymia as a predictor of outcome of psychodynamically oriented inpatient treatment. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 19(3), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300902870554

- Lin, X., Zhang, X., Liu, Q., Zhao, P., Zhong, J., Pan, P., Wang, G., & Yi, Z. (2021). Empathy and theory of mind in multiple sclerosis: A meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 628110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628110

- Lobato, D. J., & Kao, B. T. (2002). Integrated sibling-Parent group intervention to improve sibling knowledge and adjustment to chronic illness and disability. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(8), 711–716. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.711

- Lynch, S. J., Sunderland, M., Newton, N. C., & Chapman, C. (2021). A systematic review of transdiagnostic risk and protective factors for general and specific psychopathology in young people. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102036

- Marquis, S., Hayes, M. V., & McGrail, K. (2019). Factors that may affect the health of siblings of children who have an intellectual/Developmental disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(4), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12309

- McEvoy, P. M., Hyett, M. P., Shihata, S., Price, J. E., & Strachan, L. (2019). The impact of methodological and measurement factors on transdiagnostic associations with intolerance of uncertainty: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101778

- McKenzie Smith, M., Pereira, S. P., Chan, L., Rose, C., & Shafran, R. (2018). Impact of well-being interventions for siblings of children and young people with a chronic physical or mental health condition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(2), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0253-x

- McNally, R. J. (2021). Network analysis of psychopathology: Controversies and challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-092850

- Miller, M., Musser, E. D., Young, G. S., Olson, B., Steiner, R. D., & Nigg, J. T. (2019). Sibling recurrence risk and cross-aggregation of attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4076

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex ”Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0734

- Montirosso, R., Mascheroni, E., Guida, E., Piazza, C., Sali, M. E., Molteni, M., & Reni, G. (2021). Stress symptoms and resilience factors in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 40(7), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000966

- Nochaiwong, S., Ruengorn, C., Thavorn, K., Hutton, B., Awiphan, R., Phosuya, C., Ruanta, Y., Wongpakaran, N., & Wongpakaran, T. (2021). Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8

- Orm, S., & Fjermestad, K. (2021). A scoping review of psychosocial adjustment in siblings of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 5(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00222-w

- Orsmond, G. I., & Fulford, D. (2018). Adult siblings who have a brother or sister with autism: Between-Family and within-family variations in sibling relationships. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(12), 4090–4102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3669-8

- Otterman, D. L., Koopman-Verhoeff, M. E., White, T. J., Tiemeier, H., Bolhuis, K., & Jansen, P. W. (2019). Executive functioning and neurodevelopmental disorders in early childhood: A prospective population-based study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0299-7

- Petalas, M. A., Hastings, R. P., Nash, S., Dowey, A., & Reilly, D. (2009). “I like that he always shows who he is”: The perceptions and experiences of siblings with a brother with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 56(4), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120903306715

- Peterson, R. A., & Kim, Y. (2013). On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030767

- Pollard, C. A., Barry, C. M., Freedman, B. H., & Kotchick, B. A. (2013). Relationship Quality as a Moderator of Anxiety in Siblings of Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders or Down Syndrome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 647–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9618-9

- Preece, D., Becerra, R., & Campitelli, G. (2019). Assessing emotional reactivity: Psychometric properties of the perth emotional reactivity scale and the development of a short form. Journal of Personality Assessment, 101(6), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1465430

- Preece, D., Becerra, R., Robinson, K., Dandy, J., & Allan, A. (2019). The psychometric assessment of alexithymia: Development and validation of the perth alexithymia questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 132, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.011

- Preece, D. A., Mehta, A., Petrova, K., Sikka, P., Bjureberg, J., Becerra, R., & Gross, J. J. (2022). Alexithymia and emotion regulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, S0165-0327(22). 01426-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.065.

- Rankin, J. A., Tomeny, T. S., & Barry, T. D. (2017). Multi-informant assessment of siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorder: Parent-child discrepancies in at-risk classification. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 68, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.07.012

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/

- Renna, M. E., Quintero, J. M., Fresco, D. M., & Mennin, D. S. (2017). Emotion regulation therapy: A mechanism-targeted treatment for disorders of distress. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 98. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00098

- Roberts, M. E., Barthel, F. M., Lopez, C., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. L. (2011). Development and validation of the detail and flexibility questionnaire (DFlex) in eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 12(3), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.04.001