Abstract

Salvage excavations conducted in the Yenikapı quarter of the historic peninsula of Istanbul by the Istanbul Archaeological Museums 2004–2013 have brought to light the Theodosian Harbour on the Sea of Marmara. In addition to thousands of archaeological artefacts, a total of 37 shipwrecks dating from the 5th to the 11th centuries AD were uncovered, constituting the biggest collection of medieval ships uncovered at a single excavation site. The present article deals with 27 wrecks in the charge of the team from Istanbul University's Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects, consisting of 23 merchantmen and four galleys. The wrecks are presented with their general characteristics. The preliminary evidence from the Yenikapı wrecks regarding the development from shell‐based to skeleton‐based philosophy is discussed, and various building phases presented.

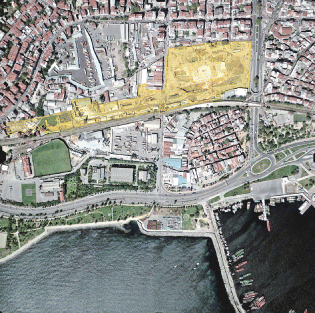

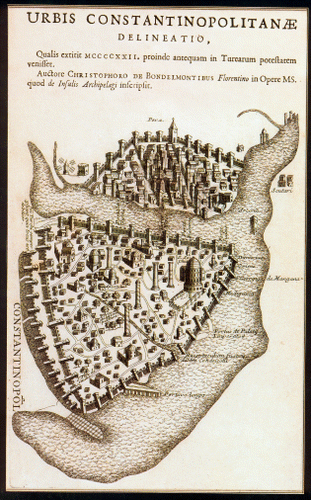

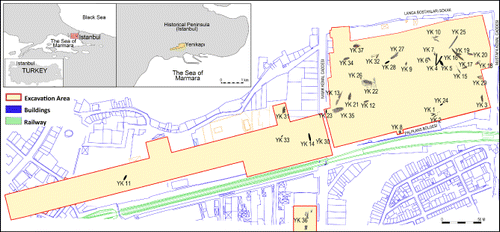

In 2004 Istanbul Archaeological Museums initiated salvage excavations at the Uskudar, Sirkeci and Yenikapı station sites of the Marmaray Project, which unites Asia and Europe at Istanbul by rail for the first time in history via a crossing under the Bosporus. The station sites are part of the historic fabric of the city (Karamut, Citation2007: 10–17; Kızıltan, Citation2007: 18–21). The excavations lasted for nine years without interruption and were completed in 2013. Construction of the main hub station at Yenikapı led to the biggest ever archaeological harbour excavation, drawing much media attention (Fig. 1). The presence of the Theodosian Harbour in this area was listed in the Notitia of Constantinople (c.425) and marked on ancient maps; however, its exact location, dimensions, and layout were not known (Fig. 2). The excavation area at Yenikapı lies within the modern Fatih district of the metropolitan area of Istanbul, and is bordered by Mustafa Kemal Street on the east, the railway on the south, and Namık Kemal Street on the west, with a projection westward into the Samatya neighbourhood. The excavations were conducted in an area of 58,000-sqm by a team of about 50 archaeologists and 600–1000 workmen. The Museum collaborated with numerous Turkish and foreign institutions including universities and institutes regarding ship and boat archaeology, conservation, osteo‐archaeology, geology, archaeobotany, philology, dendrochronology, forest botany, prehistory, and anthropology.

Figure 1. Aerial view showing the Yenikapı area and borders of the excavation site. (Courtesy of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality)

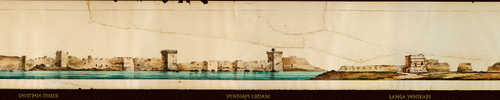

Figure 2. Urbis Constantinopolitanae Delineatio. The oldest view of Istanbul published in 1422 by Christophoro de Buondelmonte of Florence.

The excavations were carried out in a deposit 12-m deep, representing a time span ranging from the late Ottoman period back to the Neolithic period. At about −6.30-m below sea‐level, and beneath the harbour floor, were traces of a prehistoric settlement dating to 8,500 years BP, when the Sea of Marmara (Propontis) was still a lake. Structures found, including round houses built using wattle‐and‐daub, adjacent graves, various tools, organic remains, and pottery, belonged to a culture, hitherto unknown, of the earliest society settled in this area (Kızıltan, Citation2010: 1–16; Polat, Citation2013a: 75–93).

Excavations in the deep deposit brought to light hundreds of thousands of waterlogged organic and inorganic items and architectural remains (Karamani‐Pekin and Kangal, Citation2007; Kocabaş, Citation2010; Kızıltan, Citation2013). The remains of the 37 ships uncovered constitute the largest assemblage of ship‐finds dating to the Early and Middle Byzantine periods and are of great importance for studies of boat and ship archaeology, increased by their survival in very good condition. Furthermore, the Byzantine galeai recovered are particularly important, as the first archaeological evidence of galleys—the rowing ships used in the navy (Kocabaş, Citation2008). Moreover, they now provide the bulk of the archaeological evidence for galleys throughout the Mediterranean region for all periods.

Istanbul Archaeological Museums (IAM) delegated the scientific work on the wrecks to Istanbul University Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects (IU, 27 wrecks) and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA, 8 wrecks, Pulak et al., Citation75this volume), while maintaining charge of two wrecks itself. The present author undertook the direction of the project on behalf of IU, together with other IU academicians, full‐time experts, IU undergraduate and graduate students: a team which has been working on the documentation, lifting, and conservation of the wrecks since 2005. The IU team is currently studying the 27 wrecks in its charge with regards to shipbuilding techniques. Ten of these wrecks (YK 3, YK 6, YK 7, YK 8, YK 9, YK 12, YK 15, YK 17, and YK 18) were published in 2008, in which a general evaluation, photo‐mosaic images, and plan drawings were presented (Kocabaş, Citation2008). Thereafter, preliminary reports have been presented to the field (Kocabaş and Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2009a; Kocabaş and Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2009b; Kocabaş, Citation2012a; Kocabaş, Citation2012b; Kocabaş and Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2013). The present article deals with construction techniques of all the wrecks under the responsibility of IU, presenting them with in situ drawings and photo‐mosaics.

The Theodosian Harbour

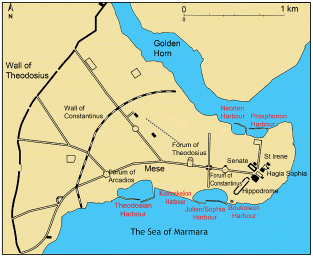

When the ancient city of Byzantium was renamed as Constantinople in AD 330, a long period of reconstruction began. The Golden Horn (Haliç), favourable for docking ships (Gyllius, Citation19De Bosporo Thracio: I, V), was supplemented by two harbours, called Prosphorion and Neorion, side by side at the entrance to this gulf (Magdalino, Citation2013: 11–15) (Fig. 3). With the imperial capital growing rapidly, two more harbours were built on the Marmara coast in the 4th century and were named after the ruling emperors at the time, Julian and Theodosius I respectively. The harbour built in the reign of Theodosius I (379–395) was located on a deep cove (Müller‐Wiener, Citation1998: 8–9), at the mouth of the Lycus (Bayrampaşa) Stream and it was enlarged and furnished with an east‐west mole on the south. There are various opinions regarding the name of this harbour in the Byzantine period. Some sources consider the Eleutherius harbour, which is known to have been built in the same region by Constantine I, to be the predecessor of the Theodosian Harbour. The harbour was also called the Kaisarios Harbour after the surrounding neighbourhood in sources from the 6th–9th centuries (Magdalino, Citation2013: 14–15).

Figure 3. Harbours of Constantinople (after Haldon, Citation2006: 72)

The east end of the Theodosian Harbour was located within the Region IX Byzantine municipal district and contained large storehouses known as the horrea Alexandrina (granaries of Alexandria) and horrea Theodosiana (Theodosian granaries); this suggests the presence of a major commercial harbour where cereals were brought from Alexandria, and other goods from elsewhere were unloaded. To begin with grain was brought directly into the city using seagoing ships of large capacity, but winds and currents at the Hellespont (Çanakkale Boğazı) hampered traffic and kept the ships waiting there. Therefore, the Emperor Justinian built granaries on the island of Tenedos (Bozcaada) from where ships of smaller capacities continued transportation up to the capital. This method of grain transport continued until AD 641 when the Arabs conquered Egypt. This lively harbour must have served also for trade in Proconnesian marble—from the island of the same name in the Sea of Marmara—bricks, tiles, lumber, and foodstuffs (Müller‐Wiener, Citation1998: 17).

Excavations in the western part of the harbour brought to light architectural remains from a wide time range, stretching from the 4th to the 13th centuries AD. Harbour structures, such as part of the sea‐walls, a quay built with large blocks, and the beginning of the mole have been identified in this area. The mole starts from the area known in the Ottoman period and to this day as ‘Davutpaşa pier’, though now inland, and curves to the east (Gyllius, Citation18De Topogra Phia Constantinopoleos, IV, VIII). The quay, running north to south, was built with large blocks of stone in two rows. It is thought that rectangular holes cut into these massive blocks were used for securing ships (Gökçay, Citation2007: 171). The harbour floor in front of this quay deepens to the east and about 30 stone anchors were found in this area. Along the line forming the north border of the excavation area, parts of the sea‐walls were identified, as well as an entrance where the sea‐walls turn south, to the east of Namık Kemal Street, which could be the harbour gate (Gökçay, Citation2007: 176).

The Theodosian Harbour declined in activity in the mid 7th century when the grain imports from Egypt halted, yet it continued to serve as a harbour, as evinced by the ships uncovered dated to the 7th–11th centuries (Asal, Citation2007; Asal, Citation2010; Asal, Citation2013). It is thought that the Lycus Stream flowing into the Marmara at Yenikapı silted the western part of the harbour first. When this part, known as the inner harbour, became unusable, activities shifted eastward; as silting progressed the remaining harbour filled up from the north southward. In its last years it served only coastal traders and fishing boats. The harbour was abandoned as a result of silting after the 12th century, when it became a dumping ground for rubble from the surrounding area, as is shown by the remains of a church from the 12th–13th centuries uncovered in the harbour basin (İncicyan, Citation1976: 4–5). After 1261, Jews were settled in this area, which came to be known as Vlanga, where they worked primarily in leather tanning (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Detail showing the Yenikapı area in a 28-m‐long drawing of the sea‐walls of Istanbul by engineer Dimitriadis Effendi in 1873. (Istanbul Archaeological Museums Library)

Travellers' accounts tell that the ‘Langa Bostanı’ was used for growing vegetables and fruits, reflected in the water tank and noria found in the upper strata dating to the Ottoman period. According to Eremya Çelebi Kömürciyan (Kömürciyan, Citation1988: 3), the majority of the locals in the area were non‐muslims in the Ottoman period, and the fourth gate built here called Yenikapı, literally ‘new gate’, was located by the Büyük Vlanga Bostanı (or Vlanga vegetable gardens).

Remains of more than 25 quays uncovered in the excavation area indicate that ships loaded and unloaded here. Studies of the animal skeletons uncovered around these quays have shown that horses were used in particular for the transportation of heavy loads. The bit‐type in use pierced the horse's palate, causing much pain to the animals, which suggests that the animals were used to their last to transport heavy loads (Onar et al., Citation2010). The harbour floor was covered with amphora fragments and cargo remains scattered when the ships sank; thus, not only can evidence of trade be seen in the remains, but also glimpses of many of the harbour's quayside activities.

Shipwreck research

It is not possible to state exactly what catastrophes these 37 sunken ships had faced within the harbour; however, it can be conjectured that some suffered storms, floods, or possibly a tsunami, while others reached the end of their working lives and were abandoned. The sudden kaçak storms of the summer months in the Sea of Marmara might have been instrumental in the sinking of ships of the 9th–10th centuries, which were uncovered closer to the eastern mouth of the harbour. The alluvium brought by the Lycus, and sand dragged in by the sea, finally rendered the Theodosian Harbour unusable but also preserved the ships.

The wrecks buried as the harbour silted up provide us with unparalleled information regarding Byzantine ship typology, shipbuilding technologies, and the development of technology. Timber elements of the Yenikapı shipwrecks were identified in situ and their original hull forms, floor timber and futtock curves traced. Most of the wrecks have surviving bottom planking, and in some cases planking reaching the bulwarks, providing data on shipbuilding technology hitherto unknown.

Recording in situ

Twenty‐seven of the wrecks uncovered by IAM were turned over to the IU team. The wrecks were roofed over with a tent incorporating a water‐spray system to keep them wet. Once the conditions were ready, detailed cleaning and recording started. In all of these stages, the utmost care was taken to avoid physical contact with the ship timbers, as their rate of deterioration was high; therefore, bridges and scaffolding were built over the remains. Timbers were labelled sequentially starting from the keel. In the early years drawings were rendered by hand using electronic measurement devices and Photo Modeler® software. As the number of wrecks increased, field documentation was made using geodesic equipment (a Total Station) within a reference system. Points were measured on each wreck and combined digitally to provide 3D images. Measurements obtained were adapted to the local coordinate system and transformed to drawing files in .dxf format; they were combined in AutoCAD with the help of sketches drawn while the wrecks were being measured in situ. The greatest advantage of the method is that the 3D measurements that will form the reference data for future reconstruction work were obtained simultaneously with the drawings made in situ. In addition, the interior surface of the planking was drawn in detail on clear acetate at full scale. Acetate sheets were spread on the planking and strake edges, scarfs, nails, caulking, pitch, and tool marks were marked in different colours and hatching patterns. Furthermore, finds‐codes, positions of the frames, port and starboard sides, scale, drawing date, and so on, were also recorded on the sheets. These drawings were then copied at the lab and archived.

Every timber of the wrecks was photographed both overall and in detail. Scarfs and other connections between timbers which cast light on the shipbuilding process were photographed and filmed before lifting. In addition, a rail system designed by our team was used to obtain photo‐mosaics of each wreck. For this, about 100 to 300 digital images of each wreck were taken and combined using Adobe Photoshop®, so that a single image of the ship with high resolution and accuracy was obtained to scale. Furthermore, each stage of the work was recorded with digital images and films.

Before lifting, all visual observations on each timber, including description, tag number, sketch, dimensions, number of fasteners and their descriptions, scarfs, tool marks, position with respect to other timbers, and so on, were written on standard forms prepared by our team (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2008: 27–72).

Lifting the wreck timbers

Following the completion of on‐site recording, the timbers were lifted using a procedure developed on site. It was decided to disassemble wreck timbers to reveal the joining details, to identify building techniques and construction details, and to facilitate absorption of the necessary chemicals during the conservation process. Dissassemblage started usually with the ceiling and stringers, as well as any other internal timbers, then progressed with frames, and concluded with planking. Iron nails and wooden fasteners holding each member in place were removed with methods chosen to cause the least damage to the surrounding timber; this often meant cutting the nails with chisels or otherwise breaking them. Planking was removed using convenient methods, such as L‐shaped timber carriers or negative timber moulds, while extremely frail timber elements were lifted using an epoxy mould method. Some planking of YK 6 was block lifted. All of these methods had one common goal: to preserve the original curvature and twist of the timbers. Bespoke timber cradles not only prevent deformation during the conservation process but also proved useful for transportation, and during documentation of the original shape. Disassembled and supported ship members were placed in wooden chests, custom‐built to their dimensions, taken into the IU Yenikapı Shipwrecks Research Centre and stored in tanks. The tanks, built of concrete with stainless‐steel liners, have an average size of 4 x 10 x 1.2-m and were roofed to prevent the unwanted effects of direct sunlight (Kocabaş and Yılmaz, Citation2008: 73–95; Kocabaş and Türkmenoğlu, Citation2009: 235–243; Kocabaş, et al., Citation2012: 303–312).

Post excavation documentation

Construction of the IU Yenikapı Shipwrecks Research Centre at Yenikapı was completed with the help of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality in 2008. The Centre, where drawing and evaluation work takes place, has 2000-m2 of outdoor area and 300-m2 indoors. The Centre is arranged in two sections: a wet area where timbers are washed and cleaned and temporarily stored in a working tank; and a dry area where manual drawings, visual evaluation, and digital documentation are conducted. Timbers, whose joining details were not visible during in situ recording, were documented in detail at the lab after disassembling. Each timber was photographed in detail with wide‐angle and macro lenses. Cataloguing the timbers continues at the lab. Characteristics such as deadrise of floor timbers, angles of arms, dimensions and types of fasteners are recorded on standard forms. The most important stage of lab work has been the digitization of each piece using a FaroArm coordinate‐measuring machine (CMM), which was used for the first time in archaeology in Turkey by our team (Hocker, Citation2003). Thus, tool marks, cross‐sections and plan views, wooden and metal fasteners, wood grain and damaged areas—all of which may cast light on the identification of shipbuilding techniques—were drawn in different colours and then rendered in 3D using Rhinoceros software. Scale research models are being developed from the documentation at the IU Faculty of Letters' Ship Conservation and Reconstruction Laboratory in order to understand the construction properties of the wrecks and to prepare for their reconstruction (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2010a: 35–51).

Conservation and restoration

Preventive conservation

As the timbers were waterlogged, conservation started, as a matter of course, before recording on site commenced. The wrecks were protected under temporary tents to shield them from sunlight and other external elements, within which recording and lifting were conducted. In order to prevent the timbers from shrinking and cracking the tent interiors were sprayed with atomized water to maintain 100% relative humidity.

Desalinization

In order to desalinate the timbers once they were placed in the storage tanks, the water in the tanks is circulated and renewed with fresh water. The incoming water line is at the bottom of the tank while the outlet is at the top; thus contamination from bacteria, fungi and algae caused by still water is prevented. The initial salinity of the timbers was found to be lower than expected, probably as a result of fresh water brought into the harbour by the Lycus. The salinity levels are dropped to 280 ppm using fresh water in the tanks, but then further lowered to 40 ppm using distilled water before the chemical impregnation procedure starts (Kocabaş, et al., Citation2012: 310). After desalinization, to prevent biological activity, bacterial and fungal growth, the biocide EXOCIDE 1012 solution is added into the pools at a concentration of 1:1000.

Cleaning of iron staining

The iron traces formed by the corrosion of the iron nails were cleaned with a 5% mixture of disodium EDTA and oxalic acid. The solution, applied to the timbers with swabs, was left on the surface for approximately four hours before being washed under flowing water for at least 15 minutes and up to two days. This process was repeated until the iron traces were totally removed.

Conservation treatment

The Yenikapı shipwrecks have survived in better condition than many underwater wrecks in the Mediterranean region because they were buried relatively quickly under a thick layer of muddy sediment. Biological activity over the centuries has still caused degradation at different levels in the cellular structure of the timber. For their conservation, PEG (polyethylene glycol) and Kauramin (melamine formaldehyde) are being employed, with Kauramin preferred for elements of highly deteriorated non‐durable materials such as plane wood (Kılıç, Citation2011: 86; Hoffmann and Witköpper, Citation1998). Wrecks in a relatively better condition, and those likely to be displayed in the future, were first soaked in a 45% solution of PEG 2000 and then freeze dried (Kocabaş, Citation2013: 404–5).

Istanbul University has established two laboratories for the conservation and restoration of the waterlogged timbers from the ships. The new Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects has enabled the launch of the first academically organized training in this field in Turkey.

Analyses

Timber identification

Identification of timbers used in the Yenikapı wrecks is of utmost importance for the identification of the regions where individual vessels were built, what kinds of timber were chosen for specific construction elements, and the repairs they underwent. These analyses are being conducted by Ünal Akkemik, chair of the IU Faculty of Forestry Department of Forest who has already identified 2800 samples from 27 wrecks (Akkemik, Citation2008: 201–211; Akkemik and Kocabaş, Citation2013: 32–41).

Chemical analyses

During periods when the wrecks were under water or covered with sediments, chemicals accumulated in their fabric. Sulphur, in particular, from the harbour floor that is stored in the timber has a direct effect on the future conservation process and long‐term stability of the wood (Sandström et al., Citation2005). Therefore, the sulphur content of timber samples taken from each wreck is being analysed within the framework of a doctoral dissertation by Gökçe Kılıç.

Dating

Out of 37 wrecks uncovered at Yenikapı only four still had their cargoes in them. Therefore, it was not possible to employ the comparative or typological dating methods widely used on archaeological wreck‐sites as, for most, only the timbers survived. Moreover, although stratigraphy within the harbour sediments was recognized during the excavation, and a group of experts consisting of archaeologists and geologists has provided a stratigraphic table for the site (Perinçek, Citation2010: 191–217), its use for dating the wrecks is problematic as a result of the unstable nature of the sea‐bed and the likelihood of dredging within the harbour in different periods of its use. Thus, relating a wreck to surrounding artefacts or stratigraphic context might be misleading and preliminary datings based purely on the site stratigraphy should be viewed with caution. It was, therefore, decided to take a minimum of three samples from each wreck for radiocarbon analysis. The average of three dates obtained from keel, frames, and planking is used to date each wreck. These analyses are being carried out by the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU) at Oxford University.

Determining the level of deterioration

Waterlogged timbers were recovered at various levels of deterioration, which is graded by the amount of water the timber has absorbed. The level of deterioration has to be determined individually for each object since it guides the quantity of chemicals used for conservation. The analyses of samples taken from hull timbers of Yenikapı wrecks indicate that the maximum moisture content (Umax) ratios of the wood samples fall in the range 280–900%. These analyses have been carried out by Namık Kılıç of IU Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects (Kılıç, Citation2013).

Characteristics of the Yenikapı wrecks

The 37 wrecks uncovered at Yenikapı exhibit the rich variety of maritime transportation vessels in use in the Byzantine Empire (Fig. 5). Byzantine authors use the terms naus, ploion, xylon, holcas, and carabion for vessels without giving any details to distinguish them. They describe how coastal seafaring, usually involving grain transportation, was conducted with small sailing ships known as sandalia, agraria, and condurai; trade with distant lands was conducted with ships known as strongyla and pamphyloi; while the navy used narrow and long vessels called dromones, chelandia, pamphyloi and ousiaka (Müller‐Wiener, Citation1998: 18; Pryor and Jeffreys, Citation2006: 372; Sakelliades, Citation1997: 47–54; Pulak, Citation2007a: 213–15; Casson, Citation1994). Ships uncovered at the Theodosian Harbour, which each reveal a moment frozen in time, have made great contributions to knowledge of shipbuilding technology and its development in antiquity and the middle ages. The terms neorion and exartysis designated dockyards for ship construction and fitting out in the Byzantine period. It is inferred from the laws of Emperor Leo VI that teaching shipbuilding to foreigners was banned, which reveals its perceived importance within the empire. The law was based on the principle that ‘no enemy should own anything that will make him superior to us’. Thus, the ban encompassed not only products but also services. In the last quarter of the 10th century, the Epanagoge states: ‘Whosoever teaches the barbarians to build ships will be liable to capital punishment’ (Balaska and Selenti, Citation1997: 58).

Figure 5. Distribution of wrecks across the excavation site at Yenikapı. (IU Yenikapı Shipwrecks Project Archive)

With the excavations at Yenikapı completed, IU's ship experts are just beginning the full‐scale drawing, examination, evaluation, and study of the building technology of the 27 wrecks in their care. Although not yet definitive, certain preliminary results have been attained regarding the mixed building technology of the transitional period involving both shell‐based and skeleton‐based methods. Our studies so far have shown that ships of relatively early dates feature pegged and unpegged mortise‐and‐tenons to join the planking. Most of the ships, on the other hand, have edge‐fasteners in the form of dowels (also termed coaks) to join the planking. Dowels appear to have been used primarily to align strakes but would have had a minor contribution to the structural integrity of the ship. The third group of ships do not have any edge‐fasteners to join the planking, with planks attached only to the frame timbers. Preliminary evaluation suggests the presence of two basic groups of ships uncovered at Yenikapı according to their purpose of use: the first encompasses merchantmen of various sizes from the 5th–11th centuries, while the second group is composed of galleys, or oared longships (Table ).

Table 1. Construction details of Yenikapı shipwrecks studied by Istanbul University

The following inventory provides preliminary information on each of the 27 vessels in the care of IU.

Merchantmen

Typical merchantmen of the Byzantine Empire were relatively small vessels with a pair of quarter rudders at the stern, lateen sails, shallow keels, and curving stems and sternposts, which gave a round look to the hull. This was a standard description for sailing ships across the Mediterranean until the end of the 13th century (Pryor, Citation2004: 43). The Yenikapı wrecks provide the archaeological evidence to support it. Merchantmen handled by IU include examples with a variety of sizes and construction methods dating from the 5th to the 10th century. Vessels YK 6, YK 7, YK 8, YK 9, YK 12, YK 18, YK 19, YK 20, YK 26 and YK 30 all have flat floor timbers with round bilges in the central parts; all but one (YK 30, which has unpegged mortise‐and‐tenons) have dowels as edge‐fasteners. Their lengths vary from 7 to 12-m and they were likely used for coastal seafaring over short distances. In addition, some might have been used for fishing. The group of medium‐sized vessels includes YK 3, YK 10, YK 15, YK 21, YK 29, YK 31, YK 32 and YK 34, while YK 17, YK 22, YK 27, YK 28 and YK 35 are examples of larger, seagoing vessels that have slack bilges with hollow garboards, or a wine‐glass‐shaped cross‐section. They are distinguished by having a high load capacity, thick and frequent frames, and longitudinal reinforcement such as stringers. There exists three types of edge joinery within the assemblage: mortise‐and‐tenon, dowels, and no edge‐fasteners. Four merchant ships, YK 1, YK 3, YK 12, and YK 35, were uncovered with their cargoes still in them (Pulak, et al., Citation2013, 31; Özsait‐Kocabaş Citation2011a). The cargoes are being studied by experts at the IAM (Kızıltan, Citation2013; Karamani‐Pekin and Kangal, Citation2007).

Small merchantmen

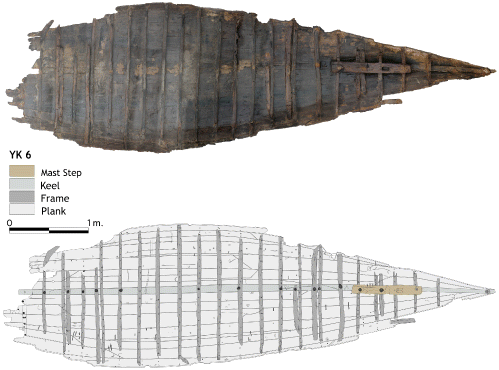

YK 6

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 103–12)

YK 6 (Fig. 6), was uncovered at a level of −0.67/−0.90-m, lying in a north‐south orientation, without any cargo. Its extant length is 6.2-m and width 1.90-m and it has flat floor timbers. It is provisionally dated to the 10th century based on stratigraphy; radiocarbon analyses are pending.

The remains include the keel, part of the stem, eight strakes of starboard and eight strakes of port planking, and 26 frames of various sizes. A bilge keel extended the entire length of the remains on each side. A mast‐step was fastened to the keel and floor timbers. It was noted that some frames and planking were added or replaced during repairs. All the extant planking was edge‐fastened with dowels, spaced at intervals of 300–350-mm on average. The planking strakes are made watertight with fibrous and resinous materials. Oakum remains found around the dowels indicate that luting was placed in the seams during fastening. The interior of the hull was entirely coated with a yellowish colophon resin. No evidence for ceiling was seen inside the boat; therefore, this boat might have had a portable ceiling system covering only the bottom.

YK 6 is thought to be a fishing boat or a small coaster as its structure is less robust than other vessels found on the site: the planks are thin and the internal framing light. Moreover, this vessel has similarities with traditional fishing vessels still seen in Istanbul. Unusually for the Yenikapi assemblage, the presence of a single mast toward the bow suggests the use of a spritsail, as seen in early iconographic sources, such as the relief on a tomb stele in Istanbul Archaeology Museum (Inv. Nr. 4251 T). The repairs, additions, and wear on floor timbers and planking together indicate long‐term use of the vessel.

The digital drawing and study of the vessel's building technique are being conducted by Can Ciner as part of his doctoral thesis at the IU Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects.

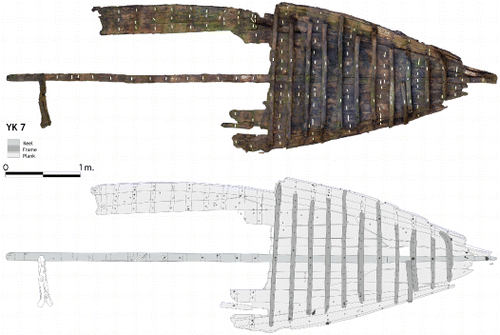

YK 7

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 132–9)

The small merchantman YK 7 (Fig. 7) was uncovered at a level of −0.91/−1.02-m, lying in a north–south orientation. Its extant length is 6.6-m and width 2.10-m; it is preliminarily dated to the 10th century based on the stratigraphic context.

Evidence of repair patches, asymmetry and irregularity in the planking pattern to port and starboard and a wide variety of timber species used, together suggest that the vessel had undergone numerous repairs during a long life. The stem and sternpost scarfs at the ends of the keel are discernible. The keel has survived in its entirety, along with 1.50-m of the stem, and with seven strakes to starboard, nine strakes to port, 11 frames, and a bilge keel on either side. Planks were edge‐joined with dowels, and planks within a strake are joined end‐to‐end with S‐ or arc‐shaped scarfs. The bilge keels are the most distinctive feature of YK 7, being rare in the assemblage. This vessel is thought to be a sailing coaster and had flat floors.

The vessel's full‐scale digital drawings have been completed and the chemical impregnation stage of conservation has been started at the IU Yenikapı Shipwrecks Research Centre.

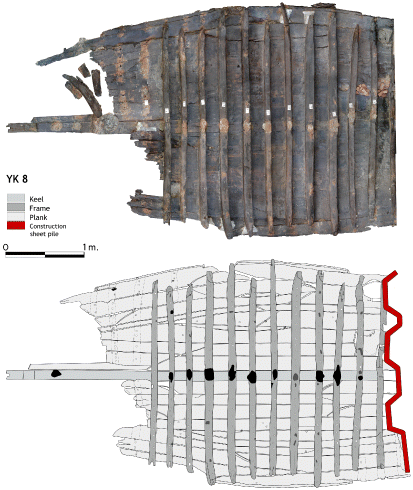

YK 8

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 148–51)

Unfortunately, about half of this merchantman lay outside the construction‐site borders (Fig. 8). It was uncovered at a level of −0.90/−1.26-m. The stern was damaged by sheet piling. The framing is very soft and fragile, but the planking is in relatively good condition, particularly near the keel. Its surviving length is 5-m with a bottom width of 2.9-m. YK 8, which was uncovered without cargo, is dated to the 10th century based on stratigraphy.

The remains consist of the partial keel, ten strakes to port and nine to starboard of 25-mm‐thick planking to the turn of the bilge, and 13 frames. The orientation of the vessel has been determined by the keel which tapers toward the bow, as seen on several of the preserved wrecks in the Yenikapi assemblage. The scarf at the forward end of the keel has survived but no information could be obtained for the sternpost as aft of floor timber E16 the vessel was damaged by sheet piling. Two holes of 50-mm diameter were bored athwartships through the keel. The hole closer to the stem shows signs of wear toward the bow. The second hole, placed c.1.14-m further along the keel, has no signs of wear. The surviving floor timbers, except at frames E4 and E15, are fastened to the keel with iron nails. Planks are joined end‐to‐end using diagonal, S‐shaped, or vertical flat scarfs. The planks are not edge‐joined, but dowels are used as fasteners at the ends of each scarf. The garboard planking strakes are flush with the top of the keel and full symmetry is attested to each side of the keel. Floor timbers are fastened to the planking with treenails or iron nails.

The conservation process of the highly degraded skeleton has been started; it was decided to render full‐scale digital drawings thereafter.

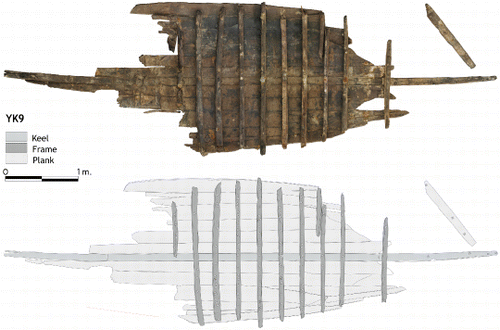

YK 9

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 125–31)

This small merchantman (Fig. 9) with flat floors was uncovered at a level of −1.40-m, lying in a north‐east–south‐west orientation. Its extant length is 6.54-m, its widest part is 1.98-m. It is dated to the 10th century based on stratigraphy.

Inside the vessel, between the floor timbers, were numerous oak branches cut using a tool. All the extant planking was edge‐joined with dowels. As on many Yenikapı wrecks, there is luting in the seams and pitch on the interior surface of the vessel. No ceiling or fastener marks for a ceiling were recorded. Keel, stem and sternpost have survived as a whole. The stem has a hole, 50-mm in diameter with wear toward the bow, which is assumed to have been for a line to draw the vessel up on shore. A total of seven planking strakes on the port side and eight on the starboard side have been identified. The surviving planks, which are joined end‐to‐end with S‐shaped scarfs, are symmetrical on both sides of the keel.

Conservation is in progress.

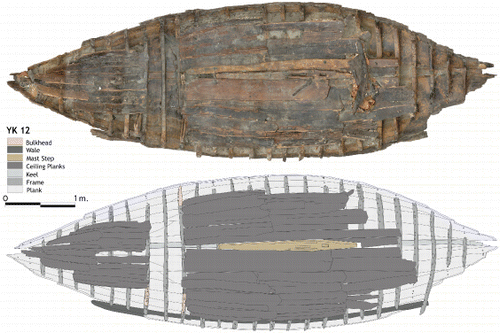

YK 12

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 112–24; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2010b; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2011b; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2013: 47–55)

YK 12 (Fig. 10) was excavated together with its cargo of amphoras. A separate compartment at the stern contained personal belongings, probably of the captain. The ship was uncovered at a level of −1.30-m, lying in an east–west orientation. Its preserved length is 7-m, while the bottom is 2.3-m at the widest point. It is dated to the 9th century based on a coin find, while the radiocarbon analyses on three samples give a date range of AD 672–876 (Table ).

Table 2. Radiocarbon analysis results. All samples analysed by Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, calibrated using OxCal V4 1.7

Surviving parts of the vessel include the keel, lower stem and sternposts, 17 strakes of planking, 25 frames, a mast‐step, 43 ceiling planks, two wales, and part of the bulwarks. All of the extant planking has dowel edge‐fasteners. The first wale to starboard was aligned with the bottom planking using dowels. The keel has survived in its entirety with keyed hook‐scarfs used to join it to the stem and sternpost. Planking samples were found to be chestnut (Castanea sativa). Planks within a strake were joined with S‐shaped scarfs. Ceiling planks were laid overlapping each other and fixed to the floor timbers using iron nails. The mast‐step of ash (Fraxinus sp.) is positioned very close to the centre of the vessel.

A lidded, portable cooking stove, a cooking pot, tankard and jugs, glass goblet fragments, and two amphoras placed in the bottom of the private compartment are of great importance for they may indicate the home port and identity of the captain and his mate (Denker et al., Citation2013: 197–209). Crimean amphoras of the 9th century constitute the cargo and point to a connection between YK 12 and the Black Sea. Cherries found in a basket, also in the stern, reveal the season when the vessel sank. Cherries ripen in June and July in the Marmara region and this find thus corroborates the suggestion that the vessel sank in a summer kaçak storm. It is possible to suggest a similar explanation for the sinking of other vessels uncovered in the same sediment deposit.

According to the results of reconstruction studies conducted by Işıl Özsait‐Kocabaş, YK 12 was a coaster about 9.60-m long and 2.60-m wide. It had a single mast and contemporary iconographic evidence suggests a lateen sail—although a square sail cannot be excluded. It was likely steered with a pair of quarter rudders, typical of the period, although no remains or direct indication of such was recovered. Its hull form with flat floors would have facilitated its sailing in shallow waters, while its wider bow would have improved steering against strong waves, as seen in the design of some Black Sea vessels today (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2011c: 60).

Digital drawings were completed and building technology was studied by Işıl Özsait‐Kocabaş for her doctoral dissertation at the IU Department of Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2010b; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2011b; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2012). The waterlogged timbers of the wreck have been impregnated with a 45% solution of PEG 2000; the conservation process will be completed by freeze‐drying in 2015 and the vessel will be prepared for exhibition. Furthermore, a replica of YK 12 will be built as part of the LIMEN project, of which IU is a partner, within the framework of the EU Black Sea Joint Operational Programme; it will be launched in 2015.

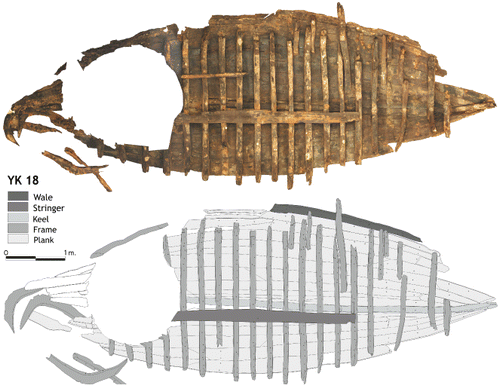

YK 18

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 140–7)

YK 18 (Fig. 11) was uncovered at a level of −1.42/−1.50-m, lying on its bottom, and orientated south‐west–north‐east. Its extant length is 8.25-m and width 3.20-m, and it is dated to the 10th century based on stratigraphy only. Concrete piles driven in for ground reinforcement during the metro construction at Yenikapı damaged a circular area of 1.5-m in diameter in the stern of this vessel. The sternpost, keel, the after part of the planking and ceiling, as well as frames in this area, were damaged and displaced.

The keel, an endpost fragment, 16 planking strakes, part of a wale, 19 floor timbers, six futtocks and one ceiling plank have survived. All of the surviving planks were edge‐fastened using dowels. Rectangular holes on floor timbers E8, E11 and E13 near the keel and close to the centre on the vessel, probably relate to a missing mast‐step.

This was a small sailing merchantman with a single mast, and soft bilges. It is worth noting that the planks are shorter than those of other vessels in the assemblage and planks within a strake were joined end‐to‐end with a variety of scarfs. Only one ceiling plank was uncovered, nailed to four floor timbers (E8, E10, E12 and E14). No evidence of other ceiling planks was observed. While some floor timbers were fixed to the keel with iron nails, some were not fastened to the keel at all. Futtocks are placed next to and at the end of the floor timbers without being joined. The garboard strakes are fixed to the rabbeted keel with iron nails. The stem was built of two pieces, while the sternpost has not survived as a result of the damage caused by the piling.

Studies and detailed documentation work by IU are in progress.

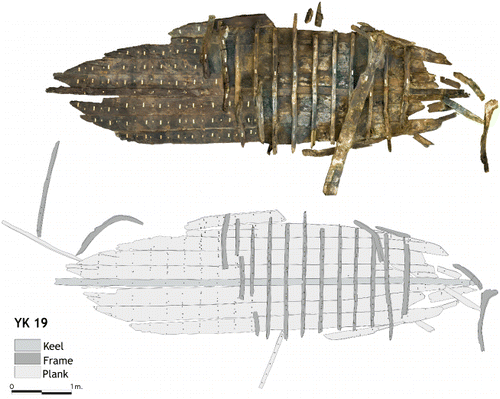

YK 19

A merchant vessel, YK 19 (Fig. 12) was discovered just beneath the bow of the galley YK 16 during its excavation (see below). YK 19 was uncovered at a level of −1.40-m. YK 16 is dated to the first half of the 8th century by radiocarbon analyses (Table ). The position of both vessels in the same stratigraphic layer implies that they sunk in the same incident, and suggests that YK 19 is of a similar date to YK 16.

Its extant length is 7.3-m, and width is 2.5-m. Surviving timbers include the keel, nine planking strakes, 12 frames still in situ, and several dislocated frames. It has flat floor timbers, like many other vessels uncovered at Yenikapı. Some frames have rectangular notches, likely for fitting a mast‐step. The vessel has survived without the cargo but with most of the extant members in situ. The planks were edge‐joined with dowels, and planks within a strake were joined end‐to‐end with S‐scarfs and diagonal scarfs.

Detailed study is in progress.

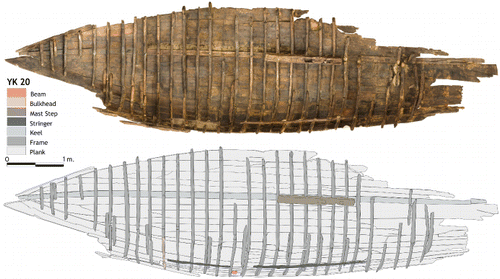

YK 20

(Güler, Citation2013: 423–7)

YK 20 (Fig. 13), one of the rare wrecks with an in situ mast‐step in the assemblage, was uncovered at a level of −0.70/−1.00-m. Its extant length is 8.76-m and the width is 2.25-m; it is dated to AD 687–975 by radiocarbon analyses (Table ).

The vessel has survived up to the turn of the bilge, including the keel, 21 strakes of planking, 29 frames, the mast‐step, and a stringer fragment. Planks were fastened to each other with dowels of 10–20-mm diameter placed at regular intervals, although no dowels are attested above the first wale. Planking was fastened to the frames with both treenails and iron nails.

Taner Güler is studying the vessel's building techniques for his doctoral dissertation.

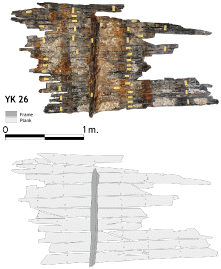

YK 26

This poorly preserved wreck (Fig. 14) was uncovered at a level of −3.50-m. Only ten planking strakes and a single frame survive. This vessel, which was uncovered without cargo and rigging, is thought to be a merchantman of the 5th–6th centuries, based on its stratigraphic context only. Both treenails and iron nails were used in its construction, and the extant planking was aligned and fastened with unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints, set at approximately 300-mm intervals.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

YK 30

This badly damaged vessel was uncovered scattered across 1-sqm at a level of −2.20-m. It is dated to the 8th–9th centuries based on stratigraphy. It was damaged by construction piles and not a single member could be recovered whole. Only four frame fragments and fragmentary planking strakes have been identified.

Medium merchantmen

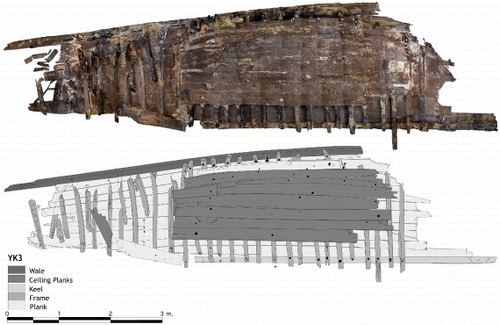

YK 3

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 152–63)

YK 3 (Fig. 15) is considered a medium‐sized merchantman when compared with other ships from the site. It was uncovered at a level of −0.69-m, lying in a north‐west–south‐east orientation. The wreck contained large amounts of baked‐clay brick fragments and mortar residue. Its extant length is 9.12-m and width is 2.28-m. The YK 3 wreck is dated by radiocarbon analyses to AD 668–987 (Table ). IAM experts were able to date stamps on some of the bricks recovered to the 5th–6th centuries AD (Demirkök, et al., Citation2013: 191–6). The obvious disparity in these dating methods will be explored with additional radiocarbon dates and the use of dendrochronological dating. Detailed work on the ship's construction techniques is currently being conducted by Ayşegül Çetiner (Çetiner, Citation2013: 56–63).

In contrast to most of the wrecks uncovered at Yenikapı, YK 3 was found lying on its starboard side, rather than its bottom; as a result, the starboard side has survived from the keel to the first wale, while the port side is absent. The keel, 11 starboard planking strakes, 1 wale, 26 floor timbers and 13 futtocks, and eight strakes of ceiling in the hold have survived. The timbers were extremely soft and disintegrating. Damage by Teredo navalis is especially prevalent on the wale, which suggests that it remained exposed under water for some time.

An important feature seen on this ship is the thick ceiling in the hold. Ceiling has often been poorly preserved and fragmentary on wrecks of this period found in the Mediterranean, but it is possible to study it in detail on some of the wrecks from Yenikapı. The keel is rabbeted to receive the garboard, which was fastened using iron nails. The bottom planking was edge‐fastened with dowels. The first wale on the starboard side was fastened to the bottom planking with dowels, but there is no trace of dowels on the upper edge of the wale. The floor timbers were fastened to the keel with iron nails hammered from the inside. Floor timbers and planking were fastened with treenails hammered from the inboard and iron nails hammered from the exterior of the planking, most commonly with two nails and one treenail at each plank‐frame junction. The wale was fastened to the floor timbers and futtocks with iron nails (Kocabaş and Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2010). A bulkhead is situated on frame no. 19, toward the stern, where the ceiling ends. This defines a stern compartment which may have been used by the captain or the crew for storage. Similar bulkheads are seen on YK 21 and YK 29.

Marble fragments uncovered in situ between the floor timbers of YK 3 cast light on the route of the vessel. YK 3 may be linked with Marmara (Proconnesos) Island, which was an important source for marble. That the vessel's ceiling planks are quite thick, 20–40-mm suggesting that its cargo was heavy, such as a cargo consisting of bricks, tiles, and marble needed for construction work in Constantinople.

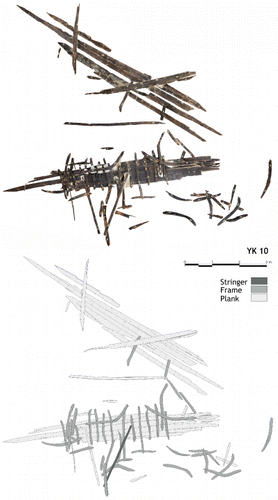

YK 10

This wreck (Fig. 16), which had no cargo, has survived in very few pieces, which were scattered across an area of 10 x10-m at a level of −2.29/−2.37-m. Its keel and many of its planks and frames are missing. Of the extant frames, 13 are fastened to planking. Planks were recovered in two groups of five and six pieces, as well as loose fragments. Two stringers have survived. The hull of the vessel is flat in the centre but has increasing deadrise toward the posts. Planks within a strake are joined with diagonal scarfs. No planking edge‐fasteners were attested. Frames are fastened to the planking mostly with iron nails. The vessel is dated to the 8th century based on stratigraphy.

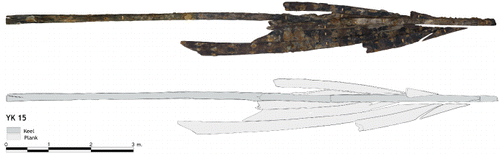

YK 15

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 164–67)

YK 15 (Fig. 17) has survived as a keel, partial stem and a few bottom planks only. It was uncovered at a level of −1.90-m, lying in a north‐west–south‐east orientation. Its extant length is 11.45-m, and width 1.30-m; it is dated to the 8th–9th centuries AD based on stratigraphy.

A 7.55-m section of the keel and stem has survived. All of the floor timbers and futtocks are missing. The presence of iron nails with an 8-mm‐square cross‐section on the keel indicate that some floor timbers were fixed in this manner. The pattern of nails on the planking suggests they were used to join frames and planking. Toward the stem, the keel comprises two timbers placed one on top of the other, fixed together with iron nails. The stem also consists of two pieces with a length of c.3.90-m. There is a hole in the lower piece, 50-mm in diameter, that is worn toward the bow, which was likely for a line used to draw the vessel on shore. A small fragment of the upper piece of the stem has survived with a scarf. The surviving two port strakes and four starboard strakes were edge‐fastened with dowels. Lines scribed on the planking clearly show where the frames were to be fitted. The thick planking (23-mm on average) is joined in strakes with S‐shaped scarfs.

The laboratory work on the wreck is in progress.

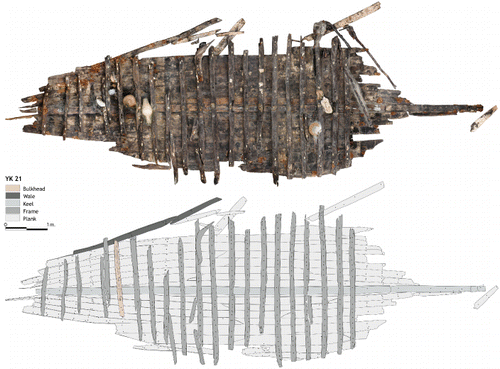

YK 21

YK 21 (Fig. 18) was uncovered at a level of −0.70/−0.60-m. Its remains are 11-m long and 4-m wide. The keel, 15 planking strakes and 23 frames have been identified among the surviving timbers. Two frames, situated toward the bow, have notches, which, through comparison with other vessels in the assemblage, are interpreted as for fitting the mast‐step. Three amphoras, which might have been part of YK 21's cargo, were uncovered in the course of excavations, but the rest of the cargo, anchors and rigging were absent. Preliminary evaluation of the amphoras and the stratigraphic context of the find suggests a date in the 9th–10th centuries. This flat‐floored vessel was propelled by the wind. Dowels were used as plank edge‐fasteners; planks within a strake were joined with S‐shaped scarfs.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed study is in progress.

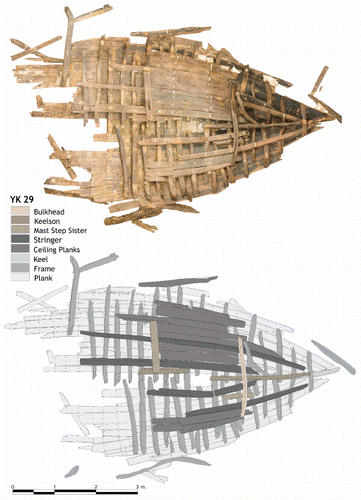

YK 29

YK 29 (Fig. 19), interpreted as a merchantman based on its rounded hull form and parallels with other vessels in the assemblage, was uncovered at a level of −2.40-m. Preliminarily dated to the 8–9th century by its stratigraphic context only, the vessel's extant length is 7.90-m and width 4.5-m. The remains include the keel, keelson, 25 planking strakes, 31 frames, several ceiling strakes and stringers, a mast‐step sister, parts of a bulkhead and several dislocated timbers. The framing system involves closely spaced alternating full and half‐floor timbers. Planks are nailed to the frames with iron nails. Stringers between ceiling planks strengthen the structure of the vessel. Preliminary observations did not note any edge‐fasteners in the planking. Planks within a strake are joined end‐to‐end with three‐planed scarfs. In the stern is a partition for a bulkhead with a groove on the upper surface of a timber.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

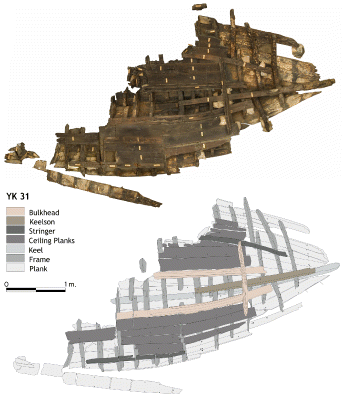

YK 31

This vessel (Fig. 20) was uncovered at a level of −1.50/−2.20-m. Its extant length is 5-m and width is 3-m. It is dated to the 9th century based on stratigraphy. Only the bow of the vessel has survived, consisting of keel and keelson, 17 planking strakes, 22 frames, ceiling planks, part of a bulkhead, as well as several dislocated and unidentified timbers. The frame system involves alternating floor timbers and futtocks. Floor timbers and futtocks are positioned side by side, but not joined, on the fore or after sides of floor timbers. The bulkhead is situated toward the bow, running athwartships, with the keel in the centre. No edge‐fasteners have been identified on the planks. Planking within a strake was joined end‐to‐end with S‐shaped scarfs.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

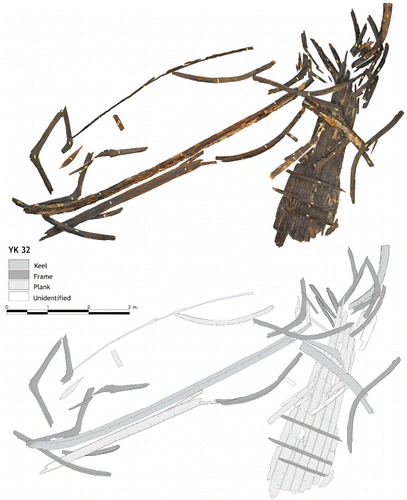

YK 32

The remains of YK 32 (Fig. 21) were uncovered scattered across an area of 50-sqm at a level of −1.55-m. Extant timbers include the keel, seven planking strakes, three frames, and several dislocated fragments. This vessel, thought to be a merchantman, was recovered without its cargo or rigging. Its exact date is not known but it is thought to be from the 8th–9th centuries, based on its stratigraphic context. Treenails and iron nails were used together in the construction of the vessel, and the planks were edge‐fastened with dowels.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed study is in progress.

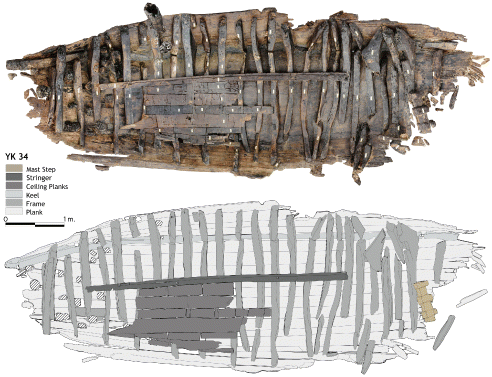

YK 34

YK 34 (Fig. 22) is the only example within the Yenikapı assemblage constructed both with pegged and unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon plank edge‐fasteners up to the waterline. It was uncovered at a level of −2.30-m. It is tentatively dated to the 5th century based on its stratigraphic context only. Its extant length is 7.60-m and width is 2.9-m. Extant elements are the keel, 16 planking strakes, 27 frames, six ceiling strakes, and several unidentified timbers. This merchantman was recovered without cargo. The starboard side is in good condition while the port side is missing to a great extent. Sturdy floor timbers are closely spaced and fixed to the keel with iron nails; the vessel originally had a very strong framing system. First observations indicate that the vessel was built with shell‐based construction technique. The frames are fastened to the planking with treenails. The hull has a wine‐glass‐shaped cross‐section.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

Large merchantmen

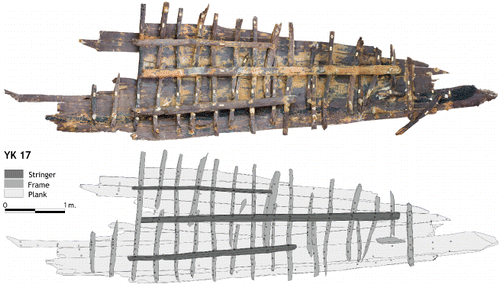

YK 17

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 168–75)

YK 17 (Fig. 23) is the only wreck excavated with the ballast still in place, made up of 56 stones weighing a total of 647-kg. It was uncovered at a level of −2.18/−2.40-m, lying in a south‐west–north‐east orientation. Its extant length is 8.20-m and width 2.25-m. It is dated to AD 652–870 through radiocarbon analyses (Table ). It is hoped that the wide date range supplied by radiocarbon analyses will be narrowed with dendrochronological dating in the future.

YK 17 is distinguished by the exclusive use of iron nails for its construction, two surviving wales—in particular, a massive wale as the 11th strake (wale 1)—and thick planking with no dowel edge‐fasteners. Its keel, stem and sternposts were not found, but 13 planking strakes, including the two wales, 24 frames, and three stringers have survived. The 11th strake has heavy charring on its inboard surface. Planks within a strake are butted end‐to‐end. The frames are 60-mm sided, and 80-mm moulded on average. All planks were fastened to the frames with iron nails. All the futtocks and floor timbers were fastened to the massive second wale with iron nails. The stringers have semi‐circular cross‐sections and measure between 2.35-m and 4.45-m in surviving length. Ongoing study of this wreck suggests the erection of at least some frames before the planks were attached (Türkmenoğlu, Citation2012).

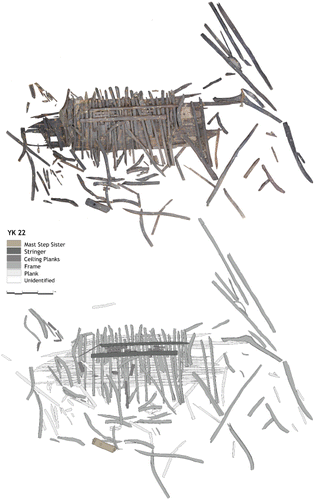

YK 22

YK 22 (Fig. 24) is the largest merchantman excavated at the site. It stands out with its thick planks joined with unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints. It was uncovered at a level of −3.60/−4.00-m, scattered across an area of about 20 x 40-m. Radiocarbon analyses indicate a date in the range of AD 430–606 (Table ). In addition to the scattered elements, 30 frames, 2 stringers and 18 planks were uncovered in situ. The framing system, of closely spaced frames, were fastened with treenails and iron nails. The planking was edge‐joined with mortise‐and‐tenons placed at irregular intervals varying from 0.60 to 1.60-m.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed study is in progress.

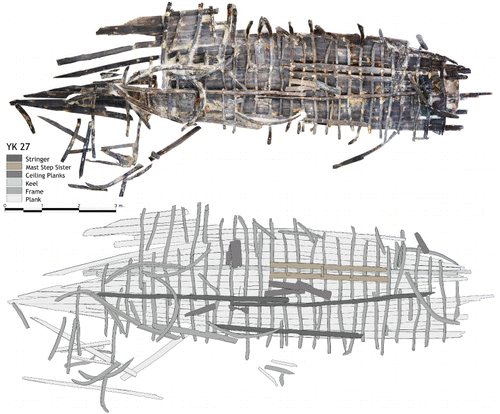

YK 27

(Türkmenoğlu, Citation2013: 414–22)

The merchantman, YK 27 (Fig. 25) is radiocarbon‐dated to AD 672–869 (Table ). The extant part of the hull is 12-m long and 4.30-m wide. It was uncovered at a level of −2.20/−3.15-m. Extant members include the keel, 21 planking strakes, 49 frames, 3 stringers, and numerous dislocated fragments belonging to unidentified timbers. Floor timbers and futtocks are not scarfed or nailed to each other. Three‐planed scarfs are used to join planks within the bottom strakes, while side planking is butted end‐to‐end. Preliminary observations did not reveal any planking edge‐fasteners. The planks were attached to the frames with iron nails.

YK 27 is currently being studied by Evren Türkmenoğlu for his doctoral dissertation.

YK 28

This wreck was uncovered as loose timbers scattered across an area of 7 x 4-m at a level of −2.00/−2.40-m. Surviving, but not in situ, components include 15 planking strakes and ten frame fragments and unidentified pieces. Planks were edge‐joined with dowels. Other timbers from this wreck were uncovered near YK 27, and both vessels have similar elements and fasteners; thus, it seems plausible that both the remains labelled YK 27 and YK 28 might be parts of the same vessel.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

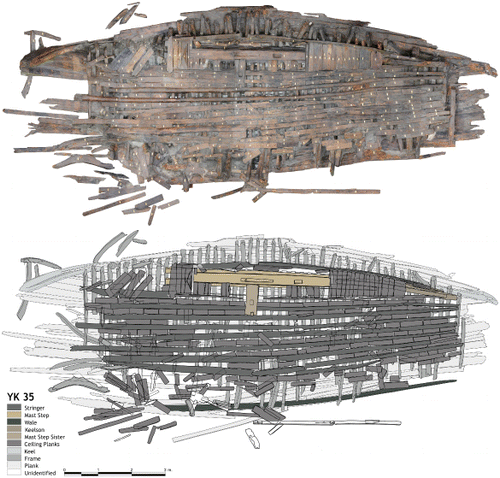

YK 35

YK 35 (Fig. 26) was uncovered at a level of −4.11/−5.23-m. This is one of the few vessels recovered together with its ceramic cargo, which dates it to the 5th century AD. Its extant length is 15-m, and width is 5.20-m. Extant components are the keel, keelson, at least 40 strakes of planking, 72 frames, dislocated and in situ ceiling strakes, wales, stringers, a mast‐step, mast‐step sister and some unidentified timbers. The amphoras forming the cargo are thought to have originated from the Black Sea. Sieving the contents of the amphoras brought to light numerous anchovy bones. Prof. Vedat Onar of the IU Veterinary Faculty, who is studying the osteo‐archaeological finds from the Yenikapı excavations, proposes that the vessel might have been carrying salted fish (Onar, Citation2013: 139–43).

The starboard side of the vessel has survived in good condition while most of the port side is absent. The step where the mast stood and a mast‐step sister on the starboard side constitute evidence for rigging. One of the most interesting features of the ship is the Greek letters engraved on some of the ceiling planks. YK 35 is the only example from Yenikapı with such marks. The purpose of these letters has not been identified yet.

YK 35 has a wine‐glass cross‐section, like that of YK 34, which distinguishes them both from other vessels in the assemblage that commonly have flat floors. In spite of the strong framing system with frames placed at regular intervals, the hull planking was fastened with unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints. Planking and frames were fastened with treenails and iron nails as well as copper‐alloy nails, commonly used on Roman ships, and uniquely attested at Yenikapı on this vessel. YK 35, with its unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints is among the earliest examples of the mixed method of the transitional period.

The amphoras and small finds from the vessel have been published by M. A. Polat of the IAM (Citation2013b: 154–90). The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed study is in progress.

Galleys

These first archaeological examples of Byzantine period galleys are easily distinguished from merchantmen by their long, slender hulls, thwarts for oarsmen, oar‐ports, and the types of timber used. Long, narrow hulls built of light timber would have provided galleys with the high speed and manoeuvrability required (Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008, 176–82). Lifting, documentation and conservation of four of the six galleys uncovered (YK 13, YK 16, YK 25, and YK 36) was undertaken by the IU team. These oared vessels may be connected with the galea mentioned in Byzantine texts; the single‐banked scout ships that lead the way for the principal Byzantine navy warships called dromons in the Byzantine navy (Sakelliades, Citation1997: 47–54; Pryor and Jeffreys, Citation2006: 190; Pulak, Citation2007b: 128–41). Although the study of the galleys is not yet complete, preliminary evidence shows that all four galleys have dowels joining the plank edges while planks within a strake are joined with long S‐shaped scarfs.

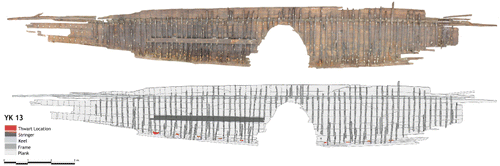

YK 13

YK 13 (Fig. 27) is one of the galleys uncovered at Yenikapı, at a level of −0.65/−1.20-m. Radiocarbon analyses indicate a date of AD 690–890 (Table ). Its extant length is 20.80-m and width 2.80-m. No items of daily use were found in the vessel.

One side of the vessel YK 13 has not survived. The frames were broken at the keel or at the second strake. Surviving are the keel, keelson, planking of one side, 95 frames, two wales, one stringer, a knee, and fragments of thwarts and their notches. These component timbers were found in situ. Planks were edge‐fastened with dowels. Planks within a strake were joined end‐to‐end with S‐shaped scarfs. Futtocks, fastened to the planking only, were positioned on the fore or after sides of the floor timbers. The frame system has alternating full and half‐floor timbers. Based on evidence and analyses the vessel is thought to have been single banked, having one file of oarsmen on each side.

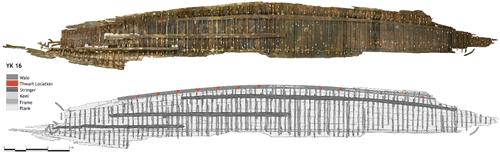

YK 16

(Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008: 176–183)

YK 16 (Fig. 28), which is thought to be a galea‐type vessel used in the Byzantine navy, was uncovered at a level of −1.30/−1.80-m. Its extant length is 22.50-m and width is 2.40-m. It is dated to AD 720–890 by radiocarbon analyses (Table ). Surviving pieces include the keel, keelson, a fragment of the stem, most of the frame system, two stringers, two wales, and planking. There are evenly spaced notches for the oarsmen's thwarts on the wale. Planking was joined in strakes with S‐shaped scarfs, and strakes are edge‐joined with widely spaced dowels with intervals ranging from 0.7-m to more than 2-m.

Scientific studies and conservation are in progress.

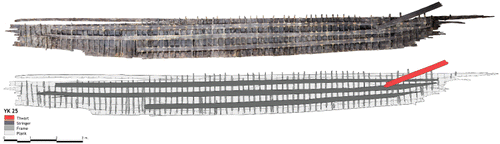

YK 25

YK 25 (Fig. 29) was uncovered at a layer of −1.40-m. Its extant length is 19-m, and width 1.50-m. Among the surviving members are ten planking strakes, 85 frames, three stringers, and one thwart. YK 25 is thought to be a galley. It was uncovered without any rigging and preliminarily dated to the 10th century by its stratigraphic context. It is similar to other galleys uncovered at Yenikapı. Planks were edge‐fastened with dowels of 10–20-mm diameter placed at regular intervals of c.300–350-mm.

The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

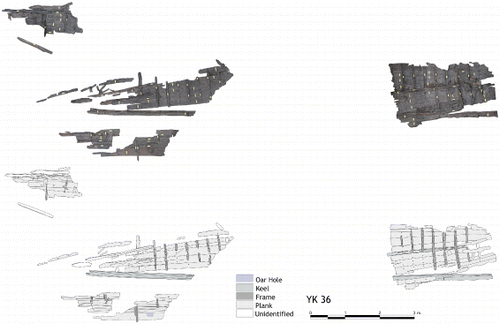

YK 36

This wreck (Fig. 30) is poorly preserved and its remains were uncovered scattered across an area of 30 x 10-m at a level of −1.10-m in the southern part of the construction site. Its poor condition has made it difficult to identify the timbers; however, oar‐ports identified on the planking have indicated that it was a galley. The scantlings of the frames and planking resemble those of other galleys uncovered at Yenikapı. Planks were edge‐fastened with dowels. The wreck was documented and lifted by IU; detailed studies continue.

Assessment and conclusion

The 37 shipwrecks uncovered in the course of salvage excavations at Yenikapı and dated from the 5th to the 11th centuries AD constitute the biggest medieval shipwreck assemblage uncovered at a single site to date. The wide date range of the wrecks provides us with a unique opportunity to comprehend the development of shipbuilding technologies in the Mediterranean region. Careful examination of the data obtained has brought to light many construction details hitherto unknown in the archaeological literature. One of the most widely debated issues in the field of boat and ship archaeology, the transition from shell‐based to skeleton‐based shipbuilding techniques and the possible reasons underlying this transition, can now revisited in light of the Yenikapı finds.

According to the preliminary results, four of the 27 wrecks studied by IU are galleys, while the remaining 23 are sailing merchantmen or fishing boats. The galleys, which have a particular importance in the archaeological record as the first vessels of this type and date to have been excavated, seem to be scout ships with a single file of oars on each side, up to 30-m long and 4-m wide, mentioned as galea in the Byzantine texts. Planking timber was obtained predominantly from black pine (Pinus nigra) while the frames were made from oriental plane (Platanus orientalis) or elm (Ulmus sp.) (Akkemik and Kocabaş, Citation2013). The planking of YK 36, which was uncovered in the south‐west part of the excavation area, at some distance from the other vessels, was made from chestnut (Castanea sativa) with frames also from oriental plane (Platanus orientalis). The use of oriental plane for framing timbers appears to be a specific characteristic of the Yenikapı galleys, and was not found in any other category of vessel in the assemblage. The plane timber frames are fastened to the planking with treenails and iron nails at close intervals. As plane timber is lighter and flexible, frames of plane timber contributed not only to the speed of the vessel but also to the strength of the hull.

According to preliminary studies, the merchant vessels studied by the IU team can be classified in three main groups, based on their construction characteristics. The first group comprises wrecks with dowels used as edge‐fasteners up to the waterline: namely YK 3, YK 6, YK 7, YK 8, YK 9, YK 12, YK 15, YK 18, YK 19, YK 20, YK 21, and YK 32. These vessels have midships sections characterized by flat floors and a round turn of the bilge, while planks within a strake are joined end‐to‐end with diagonal and S‐shaped scarfs. The frames are fastened to the planking with treenails and iron nails. Futtocks are joined to the floor timbers with L‐shaped scarfs. For larger vessels, this system is reinforced with futtocks fastened to the fore or after sides of floor timbers which are slightly curved rather than completely flat. Stringers are usually half log timbers located at the waterline. YK 8 differs somewhat from the group with its heavy and closely spaced frames and vertical flat scarfs. This group constitutes the majority of the finds and is dated to the 7th–10th centuries AD.

The second group does not have any edge‐fasteners between the planking strakes: namely YK 10, YK 17, YK 27/YK 28, YK 29, and YK 31. The planks are joined end‐to‐end using three‐planed scarfs or butt joints. The hulls have relatively flat midships sections, although the outboard surface of the floor timbers becomes more curved as the size of the vessel increases. The framing pattern has alternating floor timbers and long‐armed floor timbers to port and starboard, with futtocks positioned, but not fastened, to the fore or after sides of floor timbers. All but one has frames fixed to the planking with iron nails, the exception being YK 31. Thick stringers are fixed to the frames with iron nails. Among these vessels YK 31 stands out by its construction, using both treenails and iron nails to join frames to planking, and function, being closer to the examples with dowels described above. The remains of YK 28, which consists of only a few timbers, is thought to be a part of the nearby YK 27. Together with YK 17, these stand out within the group in having butt joints, three‐planed scarfs, and long‐armed floor timbers.

Following full‐scale drawings and detailed examination these subgroups will be refined. Studies so far indicate that the Yenikapı wrecks without edge‐fasteners have at least some frames placed before the planking. These vessels constitute a small group at Yenikapı and are currently dated to the mid 7th to the end of the 9th century AD. They provide us with new evidence about the mixed construction technique.

The third group of merchantmen includes the earliest examples from Yenikapı. One vessel of this group, YK 34, has pegged and unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon edge‐fasteners, while YK 22, YK 26 and YK 35—and also YK 37 studied by IAM—have unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon edge‐fasteners. All have a wine‐glass midships section. Thick planking and long S‐shaped scarfs are also characteristic of this group. Thick and closely spaced frames, with an alternating floor timber and half‐frame pattern, are prevalent. Sturdy stringers of half‐trunks are fastened to the interior. These vessels are dated from the 5th to the early 7th century AD.

Studies conducted so far indicate that Yenikapı wrecks were built with a mixed technique as is known from many Mediterranean ships dated from the 4th to the 11th centuries (Van Doorninck, Citation1972; Throckmorton and Throckmorton, Citation1973; Jezegou Citation1989; Harpster Citation2002; Medas, Citation2003; Kahanov, Royal and Hall, Citation2004; Van Doorninck, Citation2005; Harpster, Citation2005a; Pulak, Citation2007a; Kampbell, Citation2007; Kocabaş and Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2007; Özsait‐Kocabaş and Kocabaş, Citation2008; Pomey et al., Citation2012). The doctoral dissertation by our team member Işıl Özsait‐Kocabaş covered the building technique and reconstruction of YK 12 and examined phases of change in the building methods employed during the long period when the mixed technique was in use; the concepts of ‘shell‐based mixed construction’ and ‘skeleton‐based mixed construction’ were proposed at ISBSA 12 (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2010b; Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2012: 118–19). According to the theory arising from this research, the Yenikapı wrecks with mortise‐and‐tenon joints and most of the vessels with dowels are closer to ‘shell‐based mixed construction’ for they reflect the search for solutions at different times within the traditional shell‐based construction. It is thought that the edge‐dowels of small diameter, 10–20-mm, or of polygonal prisms placed at regular intervals found on these vessels served primarily to align the planking strakes. Many construction features, such as long planks, each shaped to fit their positions, reveal that planking contributed to the strength of the hull even in the last phase of the development.

Besides this group, wrecks with plank‐edge dowels and some frames fastened to the keel prior to planking—similarly to the Bozburun wreck (Harpster, Citation2009)—and others with no edge‐fasteners but displaying details of mixed technique, together form a distinct group in the Yenikapı assemblage. These wrecks, thought to have been built with some floor timbers placed before the planking, stand closer to the ‘skeleton‐based mixed construction’. In the long period when the mixed building technique was in use, the turning point at which shell‐based construction philosophy gave way to a skeleton‐based philosophy can be seen in vessels YK 17 and YK 27/YK 28, toward the end of the 7th century. On the other hand, YK 12 is evidence that a shell‐based philosophy resisted into the 9th century. These two watersheds are identified at Yenikapı, thus paving the way to new answers to questions about when the switch was made from shell‐based to skeleton‐based construction, and to finding a more suitable label for the long period during which these two concepts were in use together.

Presence of wrecks with pegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints (5th century), with unpegged mortise‐and‐tenon joints (5th–6th/early 7th centuries), with plank‐edge dowels (7th–10th centuries), and with no edge‐joints (7th–9th centuries) at Yenikapı constitute the primary evidence for the development of the construction techniques in the history of shipbuilding. Taking into consideration that the boats and ships uncovered at Yenikapı arrived at different times and from different origins, and considering the variation noted in previously excavated and studied wrecks (Van Doorninck, Citation1976; Bass and Van Doorninck Citation1982; Steffy, Citation1994; Harpster Citation2002; Bass et al., Citation2004; Kahanov, Royal and Hall Citation2004; Kampbell, Citation2007; Barkai, Citation2010; Pomey et al., Citation2012; Pulak et al., Citation2013), it is plausible that stages of development, which follow a linear course within themselves, started at different times in different regions within the vast geography of the Mediterranean, developing as a result of various cultural, economic etc. concerns. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the linearity of this technological development, not with respect to a group of wrecks uncovered at a certain harbour, but rather with respect to the regions where these vessels were originally built. Nevertheless, the different Yenikapı vessels, grouped by their hull construction characteristics, display some homogeneity. And yet, the variety of vessel sizes and functions—for example coasters versus open‐sea vessels—would also have influenced the rate of development in building techniques, following particular needs.

At this point, the IU team is of the opinion that the development in shipbuilding techniques should be considered from two angles: the regular order of development stages, and a non‐linear development of technology as a result of differing starting points in different regions. Although different stages of the development were probably taking place in different regions simultaneously, if local differences are excluded, it is likely that the stages of technological development followed the same order. However, a master shipwright in one region, observing a more advanced technique from another, might have skipped some lesser steps. Such a situation might allow new interpretations of the chronological differences, sometimes centuries, between the adoption of the techniques in different areas. Perhaps it is necessary to focus not on the non‐linearity of transition from shell‐based to skeleton‐based concept, but rather on the reasons why several vessels of the same date at Yenikapı display different stages of development (Özsait‐Kocabaş, Citation2011a).

Nevertheless, despite gaps in the available evidence and that of the many shipwrecks waiting to be discovered and excavated, the spatial and chronological differences noted—such as the vessels with dowels having only been found in certain regions, such as Pontelagoscuro in the Po delta (Bonino, Citation1978: 55), Bozburun in the Aegean (Harpster Citation2005b) and Yenikapı in the Marmara (Kocabaş, Citation2008)—support the idea that developments did not proceed in all areas simultaneously; and, moreover, that dowels used as edge‐fasteners could be a distinct regional technique.

The continuing study of the Yenikapı shipwrecks will certainly make great contributions to our understanding of this process, and reveal many technical details hitherto unknown.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank, above all, Istanbul Archaeological Museums for the permission to work on the wrecks and support from its directors Zeynep Kızıltan, İsmail Karamut (retired), vice director Rahmi Asal and Yenikapı field archaeologists Metin Gökçay (retired), Dr Emre Öncü, Sırrı Çömlekçi and Mehmet Ali Polat. Also all the team members, above all emeritus Prof. Dr Sait Başaran, Asst. Prof. Dr Işıl Özsait‐Kocabaş, research assistants Evren Türkmenoğlu, Taner Güler and Namık Kılıç. The IU Yenikapı Shipwrecks Project has been realized with financial support of Istanbul University Scientific Research Projects Unit (Project nos: 2294, 3907, 7381 and 12765), Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality European Side Rail Systems Directorate, and Railways Harbours and Airports Construction General Directorate Marmaray Regional Directorate. Furthermore, I would like to thank Yüksel Construction Inc., Yüksel Project Inc. and Gama Nurol Inc., which undertook engineering work, for their contributions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkemik, Ü., 2008, VII. Identification of Timbers from Yenikapı 12 shipwreck/VII. Yenikapı 12 Batığı Ahşaplarının Cins/Tür Teşhisleri”, in U. Kocabaş, The ‘Old Ships’ of ‘New Gate’ 1, Yenikapı Shipwrecks, Vol. I/Yenikapının Eski Gemileri 1, Yenikapı Batıkları, Cilt 1, 201–211. Istanbul.

- Akkemik, Ü. and Kocabaş, U., 2013, Woods of the Old Galleys of Yenikapı, Istanbul. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 13.2, 32–41.

- Asal, R., 2007, Commerce in Istanbul and the Port of Theodosius, in A. Karamani‐pekin and S. Kangal (eds), Istanbul: 8000 Years, Brought to Daylight. Marmaray, Metro and Sultanahmet Excavations, 180–189. Istanbul.

- Asal, R., 2010, Theodosius Limanı ve İstanbul'un Bizans Dönemi Deniz Ticareti/Theodosian Harbor and Sea Trade in Byzantine Istanbul, in U. Kocabaş (ed.), İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Marmaray‐Metro Kurtarma Kazıları Sempozyumu Bildiriler Kitabı, 5–6 Mayıs 2008/Istanbul Archaeological Museums, Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Marmaray‐Metro Salvage Excavations 5th–6th May 2008, 153–160. Istanbul.

- Asal, R., 2013, Yenikapı Excavations and and Trade in Istanbul in Antiquity, in Z. Kızıltan (ed.), Stories from the Hidden Harbor: The Shipwrecks of Yenikapı, 5–10. Istanbul.

- Balaska, N. and Selenti, N., 1997, On the Trade Routes, in D. Zafiropoulou (ed.), Journeys on the Seas of Byzantium, 54–69.

- Barkai, O., 2010, The Tantura F, in P. Pomey (ed.), Transferts Technologiques en Architecture Navale Méditerranéenne de l'Antiquité aux Temps Modernes: Identité Technique et Identité Culturelle. Actes de la Table Ronde Internationale d'Istanbul, 19–21 mai 2007, Varia Anatolica XXX, 97–105. Istanbul.

- Bass, G. F., Matthews, S. D., Steffy, J R. and Van doorninck, F. H., Jr., 2004, Serçe Limanı: An Eleventh‐Century Shipwreck Vol.1: The Ship and its Anchorage, Crew and Passengers. College Station, TX.

- Bass, G. F. and van Doorninck, F. H., Jr., 1982, Yassı Ada, Vol.I: A Seventh‐Century Byzantine Shipwreck. College Station, TX.

- Bonino, M., 1978, Lateen‐rigged Medieval Ships: New Evience from Wrecks in the Po Delta (Italy) and Notes on Pictorial and Other Documents. IJNA 7.1, 9–28.

- Casson, L., 1994, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times. London.

- Çetiner, A., 2013, Yenikapı 3: A Merchantman Carryıng the Past, in Z. Kızıltan (ed.), Stories from the Hidden Harbor: The Shipwrecks of Yenikapı, 56–63. Istanbul.

- Demirkök, F., Kongaz, G. and Korkmaz‐kömürcü, Ö., 2013, YK 3, in Z. Kızıltan (ed.), Stories from the Hidden Harbor: The Shipwrecks of Yenikapı, 191–196. Istanbul.

- Denker, A., Demirkök, F., Kiraz, M., and Akbaytogan, T., 2013, YK 12, in Z. Kızıltan (ed.), Stories from the Hidden Harbor: The Shipwrecks of Yenikapı, 197–209. Istanbul.

- Gökçay, M., 2007, Architectural Finds from the Yenikapı Excavation, in A. Karamani‐pekin and S. Kangal (eds), Istanbul: 8000 Years, Brought to Daylight. Marmaray, Metro and Sultanahmet Excavations, 167–179. Istanbul.

- Güler, T., 2013, Construction Technique of Yenikapı 20, in Medieval Ports in North Aegean and the Black Sea, Links to the Maritime Routes of the East, Thessalonike 4–6.12.2013, 423–427. Thessalonica.

- Gyllius, P., De Topogra Phia Constantinopoleos (İstanbul'un Tarihi Eserleri), trans. E. Özbayoğlu (trans.), 1997. Istanbul.

- Gyllius, P., De Bosporo Thracio (İstanbul Boğazı), E. Özbayoğlu (trans.), 2000. Istanbul.

- Haldon, J., 2006, Bizans Tarih Atlası, A. Özdamar (trans.). Istanbul.

- Harpster, M., 2002, A Preliminary Report on the 9th‐Century AD Hull Found Near Bozburun, Turkey, in H. Tzalas (ed.), International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Tropis VII, 409–418. Athens.

- Harpster, M., 2005a, A Re‐Assembly and Reconstruction of the 9th‐Century AD Vessel Wrecked off the Coast of Bozburun, Turkey. Unpublished PhD thesis, Texas A&M University. http://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/2695.

- Harpster, M., 2005b, Dowels as a Means of Edge‐to‐Edge Joinery in the 9th‐century AD Vessel from Bozburun, Turkey. IJNA 34, 88–94.

- Harpster, M., 2009, Designing the 9th‐Century‐AD Vessel from Bozburun, Turkey. IJNA 38.2, 297–313.

- Hocker, F. M., 2003, Documentation of the form and structure of the hull, in O. Crumlin–pedersen and A. Trakadas (eds), Hjortspring, A Pre–Roman Iron–Age Warship in Context, 84–92. Roskilde.